Abstract

Background

Rebleeding is an important cause of death and disability in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Rebleeding is probably related to the dissolution of the blood clot at the site of the aneurysm rupture by natural fibrinolytic activity. This review is an update of previously published Cochrane Reviews.

Objectives

To assess the effects of antifibrinolytic treatment in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (May 2022), CENTRAL (in the Cochrane Library 2021, Issue 1), MEDLINE (December 2012 to May 2022), and Embase (December 2012 to May 2022). In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing studies, we searched reference lists and trial registers, performed forward tracking of relevant references, and contacted drug companies (the latter in previous versions of this review).

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing oral or intravenous antifibrinolytic drugs (tranexamic acid, epsilon amino‐caproic acid, or an equivalent) with control in people with subarachnoid haemorrhage of suspected or proven aneurysmal cause.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (MRG & WJD) independently selected trials for inclusion, and extracted the data for the current update. In total, three review authors (MIB & MRG in the previous update; MRG & WJD in the current update) assessed risk of bias. For the primary outcome, we dichotomised the outcome scales into good and poor outcome, with poor outcome defined as death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability, assessed with either the Glasgow Outcome Scale or the Modified Rankin Scale. We assessed death from any cause, rates of rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus per treatment group. We expressed effects as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used random‐effects models for all analyses. We assessed the quality of the evidence with GRADE.

Main results

We included one new trial in this update, for a total of 11 included trials involving 2717 participants. The risk of bias was low in six studies. Five studies were open label, and we rated them at high risk of performance bias. We also rated one of these studies at high risk for attrition and reporting bias.

Five trials reported on poor outcome (death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability), with a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.03 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94 to 1.13; P = 0.53; 5 trials, 2359 participants; high‐quality evidence), which showed no difference between groups. All trials reported on death from all causes, which showed no difference between groups, with a pooled RR of 1.02 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.16; P = 0.77; 11 trials, 2717 participants; high‐quality evidence). In trials that combined short‐term antifibrinolytic treatment (< 72 hours) with preventative measures for delayed cerebral ischaemia, the RR for poor outcome was 0.98 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.18; P = 0.83; 2 trials, 1318 participants; high‐quality evidence).

Antifibrinolytic treatment reduced the risk of rebleeding, reported at the end of follow‐up (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.91; P = 0.01; 11 trials, 2717 participants; absolute risk reduction 7%, 95% CI 3 to 12%; moderate‐quality evidence), but there was heterogeneity (I² = 59%) between the trials. The pooled RR for delayed cerebral ischaemia was 1.27 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.62; P = 0.05; 7 trials, 2484 participants; moderate‐quality evidence). However, this effect was less extreme after the implementation of ischaemia preventative measures and < 72 hours of treatment (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.46; P = 0.49; 2 trials, 1318 participants; high‐quality evidence). Antifibrinolytic treatment showed no effect on the reported rate of hydrocephalus (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.20; P = 0.09; 6 trials, 1992 participants; high‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

The current evidence does not support the routine use of antifibrinolytic drugs in the treatment of people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. More specifically, early administration with concomitant treatment strategies to prevent delayed cerebral ischaemia does not improve clinical outcome. There is sufficient evidence from multiple randomised controlled trials to incorporate this conclusion in treatment guidelines.

Keywords: Humans, Antifibrinolytic Agents, Antifibrinolytic Agents/therapeutic use, Brain Ischemia, Hydrocephalus, Persistent Vegetative State, Persistent Vegetative State/drug therapy, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Drugs for preventing blood clot dissolution (antifibrinolytic therapy) to improve recovery after subarachnoid haemorrhage from a ruptured aneurysm (aneurysmal)

Research question

What are the effects of antifibrinolytic treatment in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage?

Background

A subarachnoid haemorrhage is bleeding into the small space between the brain and the skull that contains blood vessels that supply the brain (the subarachnoid space). The cause of this type of bleeding is most often a rupture of a weak spot (aneurysm) in one of the brain vessels. A subarachnoid haemorrhage is a relatively uncommon type of stroke, but often occurs at a young age (half the people are younger than 50 years), and therefore, has a significant socioeconomic impact. The outcome following a subarachnoid haemorrhage is often poor; one‐third of people die after the haemorrhage, and of those who survive, one‐fifth will require help for everyday activities. An important cause of poor recovery after a subarachnoid haemorrhage is repeated (recurrent) bleeding from the aneurysm (rebleeding). This is thought to be caused from natural blood clot dissolving (fibrinolytic) activity. Drugs that reduce the speed of the blood clot dissolving, called antifibrinolytic drugs, were introduced as a treatment to reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding and improve recovery after a subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to May 2022. This review included 11 trials, with a total of 2717 participants, which investigated the effect of antifibrinolytic drugs in people with a subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm.

Key results

Antifibrinolytic treatment reduces the risk of rebleeding, but does not improve overall survival, or the chance of being independent in everyday activities. We conclude that there is no evidence to support routinely giving antifibrinolytic treatment to people with a subarachnoid haemorrhage caused by a ruptured aneurysm.

Quality of evidence

We assessed the evidence for the outcomes as moderate‐ to high‐quality, which means we are very, or moderately confident in the results.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Antifibrinolytic therapy for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

| Antifibrinolytic therapy compared with standard care for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage | ||||

| Patient or population | adults with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) | |||

| Setting | hospital | |||

| Intervention | antifibrinolytic (AF) therapy | |||

| Comparison | standard care | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Poor outcome | RR 1.03 (0.94 to 1.13) | 2359 (5) | ++++ (high) | At a range of three to six months; low heterogeneity (I² = 0%) between studies and and subgroups |

| All cause mortality | RR 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) | 2717 (11) | ++++ (high) | At a range of three weeks to six months; low heterogeneity (I² = 4%) between studies and and subgroups |

| Rebleeding | RR 0.65 (0.47 to 0.91) | 2717 (11) | +++ (moderate)a | Heterogeneity (I² = 59%) between studies and and subgroups |

| Delayed cerebral ischemia | RR 1.27 (1.00 to 1.62) | 2484 (7) | +++ (moderate)b | Heterogeneity (I² = 52%) between studies is largely based on early studies that did not implement ischemia preventive therapy. This resulted in a relatively high OR. Recent studies have implemented ischemia prevention as standard SAH care. It is likely that future research will result in a lower OR for DCI |

| Hydrocephalus | RR 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 1992 (6) | ++++ (high) | Low heterogeneity (I² = 0%) between studies and and subgroups |

CI: confidence interval; DCI: delayed cerebral ischemia; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio

aQuality reduced due to inconsistencies in results bQuality reduced due to inconsistency and indirectness

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: we are uncertain about the estimate.

Background

Description of the condition

In people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), rebleeding is a leading cause of death and disability (Roos 2000b; Stienen 2018). Without aneurysm treatment, approximately 30% of people with SAH experienced a rebleed within one month of the initial haemorrhage (Locksley 1966). The rebleeding rate has now been reduced to about 15%, because in most people, the aneurysm is occluded early after admission (Germans 2014; Roos 2000b). The risk of rebleeding is highest in the first 24 hours after aneurysmal SAH, with more than half of those rebleeds occurring in the first four hours (Germans 2014; Guo 2011). The prognosis after rebleeding is poor; approximately 60% of people who rebleed die, and another 30% remain dependent for activities of daily living (Naidech 2005; Stienen 2018).

Description of the intervention

Antifibrinolytic drugs have been used to reduce the occurrence of rebleeding for decades, and were first mentioned in 1967 (Gibbs 1967; Mullan 1967). These drugs are administered orally or intravenously, and block endogenous fibrinolytic activity in the hope of preventing rebleeding.

How the intervention might work

Dissolution of the blood clot at the site of the ruptured aneurysm is thought to be an important factor in the development of rebleeding. This dissolution probably results from endogenous fibrinolytic activity after SAH. Since antifibrinolytic agents reduce fibrinolytic activity, they may reduce the occurrence of rebleeding, and thereby, improve clinical outcome after SAH. However, concerns have been raised that antifibrinolytic therapy may cause an increase of other complications, such as delayed cerebral ischaemia or early brain injury, impeding the recovery from the initial haemorrhage. Delayed cerebral ischaemia is a complication of SAH that occurs in about 30% to 35% of people between 4 and 10 days after SAH. In older trials, the beneficial effect of antifibrinolytic treatment (reducing rebleeding) was offset by an increase in delayed cerebral ischaemia, resulting in a neutral effect on outcome (Baharoglu 2013). To reduce this complication, recent literature has been directed more towards short‐term antifibrinolytic therapy with concomitant preventative measures for the development of delayed cerebral ischaemia, which may prevent the negative effects, but still provide a protective effect for rebleeding.

Why it is important to do this review

In 1967, Gibbs and O'Gorman published the first report on antifibrinolytic treatment in people with SAH (Gibbs 1967). Since then, over 100 studies of antifibrinolytic therapy in aneurysmal SAH have been published. Unfortunately, most of these studies are uncontrolled, and only a minority of the controlled studies are randomised. Moreover, the results of some of the individual randomised studies contradict each other. Furthermore, as mentioned above, concerns have been raised that antifibrinolytic therapy might increase the occurrence of delayed cerebral ischaemia or early brain injury. In a previous version of this review, we found that short‐term antifibrinolytic treatment in people concomitantly treated with measures to prevent or reverse cerebral ischaemia, may be more effective than the administration regimen in older studies (Baharoglu 2013). This led to the hypothesis that when people with aneurysmal SAH are treated according to current guidelines, and with short‐term antifibrinolytic agents, the beneficial effect of reducing rebleeds is not impeded by complications from the treatment itself. In this update of the 2013 Cochrane Review, we searched for new trials, and gave particular attention to evaluate the effectiveness of short‐term antifibrinolytic treatment in people concomitantly treated with measures to prevent or reverse delayed cerebral ischaemia (Baharoglu 2013).

Objectives

To assess the effects of antifibrinolytic treatment in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised trials in which, after concealed allocation, antifibrinolytic drugs were compared with control treatment (open studies) or placebo (blind studies) in an intention‐to‐treat analysis.

We excluded all trials in which allocation to treatment or control group was not concealed (e.g. trials in which people were allocated by means of an open random number list, alternation, or based on date of birth, days of the week, or hospital number), since foreknowledge of treatment allocation might lead to biased treatment allocation (i.e. selective enrolment). We also excluded trials in which an intention‐to‐treat analysis was not performed, and could not be reconstructed on the basis of published data without a loss of 20% or more of all randomised participants.

Types of participants

Trials in which participants were included with clinical symptoms and signs of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), presumably caused by a ruptured aneurysm, and with confirmation of the diagnosis by the presence of subarachnoid blood on computed tomography (CT) scan, or on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination.

Types of interventions

Antifibrinolytic drugs (e.g. tranexamic acid, epsilon amino‐caproic acid, or equivalent drugs), oral or intravenous, versus control treatment (open studies) or placebo treatment (blind studies). Since the risk of rebleeding is highest during the first two weeks after the initial bleeding, treatment had to start within two weeks after onset of the SAH. Distinction was made between a combination of early start and short‐term duration(< 72 hours of onset of symptoms, i.e. before usual timing of onset of cerebral ischaemia) versus long‐term (> 72 hours) treatment duration and concomitant measures to prevent delayed cerebral ischaemia or not.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was poor outcome (death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability), assessed with either the Glasgow Outcome Scale or the Modified Rankin Scale, at the end of at least three months of follow‐up after SAH.

Death from all causes, at a minimum follow‐up of at least three weeks, was our second primary outcome, since most studies only reported on case fatality.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome measures were the effects of antifibrinolytic treatment on both the rates of reported and CT scan, or autopsy confirmed (sensitivity analyses) episodes of rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for trials in all languages, and arranged translations of relevant reports when required.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched 31 May 2022), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, issue 3) in the Cochrane Library (searched 31 May 2022; Appendix 1), MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 31 May 2022; Appendix 2), and EMBASE Ovid (1980 to 31 May 2022; Appendix 3).

We developed comprehensive search strategies with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Information Specialist, and adapted the MEDLINE strategy for CENTRAL and Embase. Where appropriate, we combined them with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategies, designed by Cochrane to identify RCTs and controlled clinical trials (described in the Technical Supplement to Chapter 4 in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2021)).

All search strategies were revised and updated to account for newly identified, relevant index headings, and keywords. Both versions of the search strategies are included in Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

We also searched the following trial registers for ongoing clinical trials.

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 31 May 2022; Appendix 6)

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.trialsearch.who.int; searched 31 May 2022; Appendix 7)

The following resources were searched for the previous iteration of this review. The EU Clinical Trials Register and ISRCTN data sets are now accessible in the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform; the Stroke Trials Registry site is no longer operational.

EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu; last searched 1 December 2012)

Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials/; last searched 1 December 2012)

ISRCTN registry (formerly known as Current Controlled Trials; www.isrctn.com; last searched 1 December 2012)

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished, and ongoing studies:

we searched the list of references quoted in all included studies and reviews on antifibrinolytic therapy (Adams 1982; Adams 1987; Biller 1988; Carley 2005; Chawjol 2008; Connolly 2012; Fodstad 1982; Lindsay 1987; Maira 2006; Mayberg 1994; Post 2021; Ramirez 1981; Ren 2021; Rinkel 2008; Van Gijn 2001; Van Gijn 2007; Vermeulen 1980; Vermeulen 1996; Weaver 1994; Weir 1987);

we used Science Citation Index Cited Reference Search for forward tracking of important articles; and

for the first version of this review (Roos 1998), we contacted the pharmaceutical company Pharmacia and Upjohn, formerly Kabi, manufacturer and license holder of the antifibrinolytic drug tranexamic acid. We identified no additional (unpublished) studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MRG and WJD) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the records obtained from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant records. We obtained the full‐text articles for the remaining studies, and the same two review authors independently selected the trials that met the predefined inclusion criteria. The review authors resolved disagreements by discussion, and when necessary, in consultation with a third review author (YBWEMR).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MRG and WJD) independently reviewed the additional eligible studies, and extracted details on the number of participants in the treated and the placebo or control groups, the randomisation method, blinding method, the definitions for diagnosis and complications, and also ascertained whether an intention‐to‐treat analyses was done or could be reconstructed from the published data. When consensus could not be reached, the review authors consulted a third review author (YBWEMR).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MRG and WD) independently assessed the risk of bias of each additional study using RoB 1, which comprises the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 8 (Higgins 2011). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias): all outcomes

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): all outcomes

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): all outcomes

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)

Other bias

We graded each potential source of bias as high risk, low risk, or unclear risk of bias, and provided information from each study in the risk of bias tables.

Measures of treatment effect

We processed data in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 6 (Higgins 2022). For the primary outcome, we dichotomised the outcome scales between good and poor outcome for the analysis. Poor outcome was defined as death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability, as assessed with either the Glasgow Outcome Scale or the modified Rankin Scale. We scored death from any cause, rates of rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus per treatment group. We expressed effects as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant, since we only included individually randomised trials with a parallel design.

Dealing with missing data

In trials without intention‐to‐treat analysis, we tried to reconstruct one, based only on the published data. When the proportion of missing values for outcome was less than 20%, we included the study in our analysis. For two trials, we tried to contact the principal investigator to retrieve data on the number of participants in whom rebleeding or cerebral ischaemia were proven on CT scan or at autopsy (Hillman 2002; Tsementzis 1990). We received a reply from one of the study authors. We made no effort to obtain additional information for studies published 15 or more years ago.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For each outcome, we assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I²statistic, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 10 (Higgins 2022). We considered an I² statistic less than 50% as low heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

To investigate possible publication bias, we planned to create funnel plots for poor outcome, death from all causes, and the rebleeding rate, if they were measured by at least 10 studies, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 13 (Higgins 2022).

Data synthesis

Because we expected heterogeneity between studies, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects model for pooled analyses, in Review Manager software (Review Manager Web 2020).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

To assess whether masked studies showed different results from unmasked studies, we divided all analyses into two groups: trials with control treatment (open studies) and trials with placebo treatment (blind studies). We added an additional subgroup analysis to evaluate the effect of antifibrinolytic therapy on all outcomes in trials with and without additional measures to prevent or reverse delayed cerebral ischaemia, and to evaluate the effect of antifibrinolytic therapy according to treatment duration. We divided the included trials into one of three groups: (1) trials without ischaemia prevention and treatment duration > 72 hours, (2) trials with ischaemia prevention and treatment duration > 72 hours, and (3) trials with ischaemia prevention and treatment duration < 72 hours. Because we defined that a minimum of one study should be included in a subgroup, we did not include a fourth group (trials without ischaemia prevention and treatment duration < 72 hours), as there were no trials that met these criteria.

In addition, we checked whether data were available on aneurysm treatment (i.e. clipping or coiling) according to antifibrinolytic treatment, to evaluate whether a subgroup analysis on clipping versus coiling was possible.

Sensitivity analysis

Because our secondary outcome measures were more prone to bias, we carried out sensitivity analyses on confirmed (rather than reported) rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus rates.

Summary of findings and assessment of the quality of the evidence

We reported the summary of findings according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 14 (Higgins 2022). We assessed the quality of the evidence by investigating imprecision by 95% confidence intervals, inconsistency by heterogeneity, indirectness, and study and publication bias by reporting them in risk of bias tables, according to GRADE. Outcomes included poor outcome (death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability), all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We reported the summary of findings according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chapter 14 (Higgins 2022). We assessed the quality of the evidence by investigating imprecision by 95% confidence intervals, inconsistency by heterogeneity, indirectness, and study and publication bias by reporting them in risk of bias tables according to GRADE. Outcomes included poor outcome (death, vegetative state, or (moderate) severe disability), all‐cause mortality, rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischemia, and hydrocephalus.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

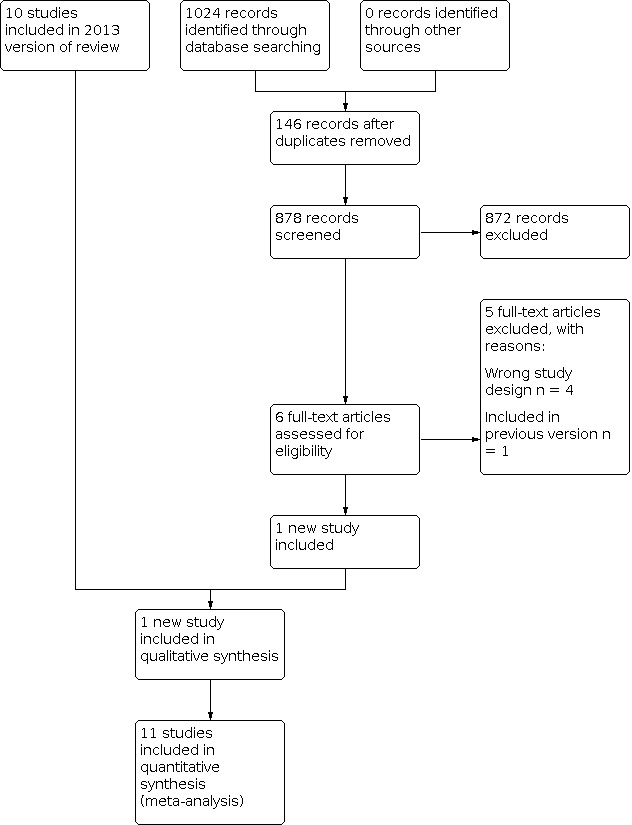

The updated 2022 search of the bibliographic databases yielded a total of 1024 records, from which we removed 146 duplicates, leaving a total of 878 records. After screening titles and abstracts, we excluded 872 records, leaving six records for which we obtained the full‐text articles. Three studies were included in the list of excluded studies in the previous version. Further assessment resulted in one potentially relevant trial (Post 2021). Eleven trials met the inclusion criteria for the review; we excluded eight trials. For an overview of the search results, see Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA overview of updated search (December 2012 to May 2022)

Included studies

Since the previously published review of Baharoglu 2013, one new trial met the inclusion criteria (Post 2021). Therefore, we included 11 studies, which are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table (Chandra 1978; Fodstad 1981; Girvin 1973; Hillman 2002; Kaste 1979; Maurice 1978; Post 2021; Roos 2000a; Tsementzis 1990; Van Rossum 1977; Vermeulen 1984). These 11 studies included 2717 participants, 1368 of whom were randomised to receive antifibrinolytic drugs, 597 to receive placebo treatment, and 752 to receive control treatment. The Girvin 1973 study used epsilon‐amino‐caproic acid (39 participants); tranexamic acid was used in all other studies. The Post 2021 study is the largest trial, including 955 participants; however, the study also included participants with non‐aneurysmal SAH (14%). The data for the current review were extracted from Tsementzis 1990, which only presented the results of the aneurysmal SAH (Post 2021). In three studies, participants were concomitantly treated with measures to prevent or reverse cerebral ischaemia (Hillman 2002; Post 2021; Roos 2000a). The duration of antifibrinolytic treatment differed considerably between studies, and ranged from less than 72 hours to six weeks. Short‐term treatment was used in two studies (Hillman 2002; Post 2021). In these studies, participants were treated up to 72 hours after SAH (Hillman 2002), or up to 24 hours after the start of tranexamic acid treatment (Post 2021). All other studies treated participants for at least 10 days (or until occlusion of the aneurysm) after SAH.

Five studies reported clinical outcome, and we were able to reconstruct the number of participants with poor outcomes (Hillman 2002; Post 2021; Roos 2000a; Tsementzis 1990; Vermeulen 1984). Death from all causes and rebleeding rates were reported in all 11 studies. In six studies, episodes of rebleeding were defined primarily by clinical symptoms.

Three trials reported computed tomography (CT) scan‐ or autopsy‐confirmed episodes of rebleeding (Fodstad 1981; Hillman 2002; Post 2021). Three trials defined and reported rebleeding in two ways: as 'probable' if the diagnosis was suspected solely on clinical grounds, and as 'definite' when proven by CT (after comparison with an earlier CT), or at autopsy; the Dutch‐British trial (Vermeulen 1984), STAR study (Roos 2000a), and the ULTRA trial (Post 2021).

Delayed cerebral ischaemia was reported in seven studies, but defined in only four: in two studies, cerebral ischaemia was defined and reported in the same manner as episodes of rebleeding; as 'probable' and as 'definite' (CT scan‐ or autopsy‐confirmed) cerebral ischaemia (Roos 2000a; Vermeulen 1984). Again, as for rebleeding, Fodstad 1981 reported on CT scan‐ or autopsy‐confirmed cerebral ischaemia. Post 2021 defined delayed cerebral ischaemia according to the definition used by a multidisciplinary research group (Vergouwen 2010). Hillman 2002 reported the percentage of transient and permanent delayed ischaemic neurological deficits. No clear definition was given, and CT scans were not routinely used to confirm delayed cerebral ischaemia. Because other studies did not make a distinction between permanent or transient delayed cerebral ischaemia, we decided to combine these outcomes. Hillman 2002 reported visible infarction on CT scan; however, after contact with the study author, we decided not to use this as a measure for delayed cerebral ischaemia, since this was not always correlated to clinical signs of delayed cerebral ischaemia. The other two studies made no distinction between participants with episodes clinically suggestive of delayed cerebral ischaemia, or participants with confirmed delayed cerebral ischaemia, and reported only an all‐inclusive number of participants (Girvin 1973; Tsementzis 1990). One study reported on 'delayed cerebral ischaemia' and 'postoperative ischaemia' (Roos 2000a). Since the other studies did not make this distinction, and reported an overall number of participants with delayed cerebral ischaemia, we grouped these subgroups of ischaemia for the analysis on cerebral ischaemia.

Six trials reported on hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus was defined in two studies by means other than clinical grounds, and therefore, could be included in the sensitivity analysis for confirmed hydrocephalus (Post 2021; Roos 2000a). No trials reported on aneurysm treatment modality (i.e. coiling versus clipping) according to antifibrinolytic or control treatment, and thus, we were unable to undertake a subgroup analysis based on aneurysmal occlusion modality.

Excluded studies

We excluded eight studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table): some were comparative trials between two or more antifibrinolytic agents, others used unconcealed allocation, and some were not randomised but used historical controls. We excluded Fodstad 1978, as 23% of the participants in the trial were later excluded, and we were unable to reconstruct an intention‐to‐treat analysis on the basis of the published data.

Risk of bias in included studies

For a summary of the risk of bias see Figure 2 and Figure 3. Six of the 11 included trials used an intention‐to‐treat analysis; in one of the remaining trials, we were unable to reconstruct this analysis using the available follow‐up data (Maurice 1978).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

Girvin 1973 used 'flip‐of‐a‐coin' randomisation as the method of allocation, which is more susceptible to bias compared with, for instance, the sealed envelope method. Nevertheless, we decided to include this study, since this is an accepted form of randomisation with allocation sequence generation and concealment according to Cochrane guidelines. All other studies used a method of concealed allocation that was considered appropriate at the time the trial was conducted, although it was not always mentioned whether or not the sealed envelopes that were used were opaque, resulting in an unclear risk of bias assessment (Fodstad 1981; Hillman 2002).

Blinding

Six studies used a double‐blind method (placebo controlled), and five used a control group with standard treatment without placebo. The control group studies were open label, and we rated them at high risk of performance bias (all five studies), and detection bias (one study: Hillman 2002).

Incomplete outcome data

In five trials, there was no follow‐up information available for participants who were excluded after randomisation (Fodstad 1981; Hillman 2002; Post 2021; Tsementzis 1990; Van Rossum 1977). In four studies, a very small number of participants were excluded from the final analysis (Fodstad 1981 (n = 1); Post 2021 (n = 10); Tsementzis 1990 (n = 4); Van Rossum 1977 (n = 3); therefore, we still included these studies.

In one study, 91 (15%) of the 596 participants were excluded after randomisation (Hillman 2002). Because this was less than the prespecified proportion of 20%, we included this study in our analysis. We rated this study at high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting

In one study, no previously published protocol was mentioned, and clinical outcome was reported, although not described, in the introduction or methods (Hillman 2002). For the Post 2021 study, a protocol was published (Germans 2013). The primary outcome and most secondary outcomes were reported, including all secondary outcomes relevant to this review. In two other studies, the selective reporting could not be assessed, and we reported them as unclear risk of bias (Chandra 1978; Tsementzis 1990).

Other potential sources of bias

No studies showed a high risk of other source of bias, however, in four studies, we could not assess this, and therefore, we reported them as unclear risk of bias (Chandra 1978; Kaste 1979; Maurice 1978; Tsementzis 1990). The funnel plots for death and rebleeding are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The plot on 'poor outcome' (Figure 5), shows no asymmetry and heterogeneity was low between studies, indicating no publication bias.

4.

Funnel plot of included trials assessing case fatality

5.

Funnel plot of included trials assessing rebleeding

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo

Poor outcome

The results were inconclusive for poor outcome (risk ratio (RR) 1.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.94 to 1.13; P = 0.53; 5 trials, 2359 participants; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.1). The results remained inconclusive when analysed by duration of treatment (P = 0.83; Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 1: Poor outcome (death, vegetative, or (moderate) severe disability) at end of follow‐up: open versus blind studies

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 2: Poor outcome (death, vegetative, or (moderate) severe disability) at end of follow‐up: trials with and without ischaemia prevention, according to treatment duration

All‐cause mortality

The pooled RR for our second primary outcome measure, all‐cause mortality, was 1.02 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.16; P = 0.77; 11 trials, 2717 participants; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.3). Duration of treatment showed no effect on all‐cause mortality (P = 0.77; Analysis 1.4).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 3: Death from all causes at end of follow‐up: open versus blind studies

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 4: Death from all causes at end of follow‐up: trials with and without ischaemia prevention, according to treatment duration

Confirmed rebleeding

In the analysis on rebleeding rates, antifibrinolytic therapy reduced the risk of rebleeding (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.91; P = 0.01; 11 trials, 2717 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; absolute risk reduction 7%, 95% CI 3 to 12%; Analysis 1.5). Heterogeneity was detected for this comparison (I² = 59%; P = 0.007; Analysis 1.5). Similar estimates were found in the subgroup analysis of the six double‐blind and placebo‐controlled studies (RR 0.64; P = 0.03; Analysis 1.5); the sensitivity analysis including five studies with CT scan‐ or autopsy‐confirmed rebleeding (RR 0.50; P < 0.001; Analysis 1.6); and in the subgroup analysis of two studies with ischaemia prevention and < 72 hours of treatment (RR 0.42; P = 0.14; Analysis 1.7).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 5: Rebleeding reported at end of follow‐up: open versus blind studies

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 6: Confirmed rebleeding at end of follow‐up (sensitivity analysis): open versus blind studies

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 7: Rebleeding reported at end of follow‐up: trials with and without ischaemia prevention, according to treatment duration

Delayed cerebral ischaemia

Seven trials that reported delayed cerebral ischaemia rates showed moderate‐quality evidence that antifibrinolytic treatment increased the risk of delayed cerebral ischaemia (RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.62; P = 0.05; 7 trials, 2484 participants; moderate‐quality evidence; absolute increase of 36 per 1000 people; Analysis 1.8). Similar effects were seen in the subgroup analysis of the three placebo‐controlled trials (RR 1.38; P = 0.17; Analysis 1.8). This effect was reduced, and showed no association after the implementation of ischaemia preventative measures and < 72 hours of treatment (RR 1.10; P = 0.49; Analysis 1.10). Heterogeneity of intervention effect was detected in all seven studies combined (I² = 52%; P = 0.05; Analysis 1.10). This effect was reduced in the two trials with ischaemia prevention and treatment < 72 hours, with low heterogeneity (I² = 35%; P = 0.49; Analysis 1.10).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 8: Delayed cerebral ischaemia reported at end of follow‐up: open versus blind studies

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 10: Delayed cerebral ischaemia reported at end of follow‐up: trials with and without ischaemia prevention, according to treatment duration

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus was reported in six trials. Overall, antifibrinolytic treatment had no effect on the reported rates of hydrocephalus (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.20; P = 0.09; 6 trials, 1992 participants; high‐quality evidence; Analysis 1.11). In the subgroup analysis on placebo versus open studies, antifibrinolytic treatment in the placebo controlled studies showed a more pronounced effect for hydrocephalus (RR 1.19; P = 0.13; Analysis 1.11), whereas in the open label trials, it was more protective for hydrocephalus (RR 0.94; P = 0.73; Analysis 1.11). The sensitivity analysis on two trials with CT scan‐ or autopsy‐confirmed hydrocephalus, including 93% of all hydrocephalus patients, showed no association between antifibrinolytic treatment and hydrocephalus (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.21; P = 0.09; 2 trials, 1275 participants; Analysis 1.12). Ischaemia prevention did not seem to have any effect on hydrocephalus in the subgroup analyses (P = 0.85; Analysis 1.13).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 11: Hydrocephalus reported at end of follow‐up: open versus blind studies

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 12: Confirmed hydrocephalus at end of follow‐up (sensitivity analysis): open versus blind studies

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo, Outcome 13: Hydrocephalus reported at end of follow‐up: trials with and without ischaemia prevention, according to treatment duration

Discussion

Summary of main results

Although this systematic review and meta‐analysis show that antifibrinolytic treatment reduces the rate of rebleeding by approximately 35%, there is no evidence of benefit from antifibrinolytic treatment on poor outcome or death from all causes. We added the recent and largest ULTRA trial, which administered antifibrinolytic treatment ultra‐early and short‐term, to the review, but there was no change in the overall conclusion compared to previous versions (Post 2021). A sensitivity analysis on trials with ischaemia prevention and short‐term (< 72 hours) antifibrinolytic treatment did not show a difference in the effect on either poor outcome, or death from all causes. Furthermore, the risk for delayed cerebral ischaemia was not increased by antifibrinolytic treatment when ischaemia preventative measures were applied. The current, high‐quality evidence does not support the routine use of antifibrinolytic treatment in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Trials in which people were included with symptoms and signs of subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) of suspected or proven aneurysmal cause, with confirmation of the diagnosis by the presence of subarachnoid blood on computed tomography (CT) or on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination were eligible for this review. We chose this pragmatic approach, and did not restrict our review to people with angiographically‐proven aneurysms, because antifibrinolytic treatment may also be started after CT angiography (CTA)‐confirmed presence of an intracranial aneurysm. However, we chose not to limit our analysis to radiologically‐proven aneurysmal SAH, because CTA was not regularly applied when most of the trials were conducted. In the past decades, the outcome of aneurysmal SAH has constantly improved, which is attributable to improved intensive care management, aneurysm treatment techniques, and reduced interval to aneurysm treatment. Especially, earlier aneurysm treatment may have had influence on a reduced incidence of rebleeds, diminishing the potential effect of reducing rebleeds by antifibrinolytic treatment. Nevertheless, the evidence undisputedly shows that despite a significant reduction in rebleeds, the overall outcome is not improved with antifibrinolytic therapy. However, the current evidence is unclear about the effect of antifibrinolytic treatment in a subgroup of people at a very high risk for rebleeding, such as those who are diagnosed very early, or in those for whom there is anticipated delay in aneurysm treatment.

The included trials were performed in a timespan of 48 years, during which overall clinical outcome has improved. Treating people with aneurysmal SAH with preventative measures for delayed cerebral ischaemia has eliminated the increased risk of this complication of antifibrinolytic treatment. Even then, antifibrinolytic treatment does not improve poor outcome or death from all causes. The consistency of results in several studies with low risks of bias, and persistency over years even with optimisation of the treatment of complications, makes this conclusion generalisable. It is very unlikely that future trials will change the conclusion that routine antifibrinolytic treatment has no evidence of benefit in people with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Quality of the evidence

We only included true randomised controlled trials, and performed a subgroup analysis on placebo‐controlled versus open studies in an attempt to minimise allocation and performance bias. Many of the included studies were older (published between 1973 and 1990), and most did not report on many sources of potential bias, such as how the randomisation sequence was generated, and whether participant outcome was assessed by individuals who were blinded to the given intervention. Therefore, we scored many potential sources as unclear risk of bias, as can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Luckily, the studies assessed with several sources of unclear risk were small, and in total, comprised about 10% of all included participants. The majority of the included participants originated from four studies (Hillman 2002; Post 2021; Roos 2000a; Vermeulen 1984). Three of these studies, comprising 65% of all data, were rated as low risk of bias for all sources, except for performance bias in Post 2021 (Post 2021; Roos 2000a; Vermeulen 1984). In Hillman 2002, many potential sources of bias could not be scored and were unclear, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinded outcome assessment. Moreover, 15% of included participants were later excluded from the analysis, and the baseline characteristics and outcomes of these participants were not reported. We included this study in the subgroup analysis with ischaemia prevention and treatment duration < 72 hours, in which the much larger and methodologically sound study of Post 2021 was also included. Because the latter study showed no large changes in effect on primary outcomes compared to Hillman 2002, and because heterogeneity between studies was probably not important for poor outcome (I² 33%; Analysis 1.1); and death from all causes (I² 0%; Analysis 1.3), we assume that the results of this subgroup are trustworthy.

Visual inspection of the funnel plots for death from all causes at end of follow‐up (Figure 4), and rebleeding reported at end of follow‐up (Figure 5), revealed a potential publication bias, with a lack of small studies showing a harmful effect (RR > 1) of antifibrinolytic treatment. We did not do a statistical analysis on these plots, due to the relatively small number of studies. Because several large randomised studies have been performed, the influence of small studies with negative results that were not published would not have changed the overall estimate of death or rebleeding after treatment with antifibrinolytic therapy.

Potential biases in the review process

We searched all major medical electronic databases and other sources, using sensitive and validated search strategies. However, it is possible that we did not find all relevant publications. Furthermore, we only included studies that were published in medical literature and did not search the grey literature, such as government reports and unpublished information. Although all included trials met the predefined inclusion criteria, the studies differed considerably in participant selection, disease severity at baseline, start and duration of treatment, dosage and type of trial medication, classification of events, outcome assessment, and duration of follow‐up. This clinical heterogeneity may, in part, account for the statistical heterogeneity found in the analyses on rebleeding and delayed cerebral ischaemia. The process of selecting eligible studies and assessing sources of bias in the latest version of this review were not performed by the same assessors as in previous versions. However, one of the assessors in the current version was also an assessor in the previous version (MRG), which should have reduced interobserver variability, and therefore, reduced observer bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our results are similar to the results from the most recent meta‐analysis (Ren 2021). Ren 2021 included all randomised controlled trials included in the present update, except Girvin 1973. Our results are also comparable with Gaberel 2012, in which all studies compared antifibrinolytic treatment with control treatment, including retrospective analyses, and studies with historical control groups. Retrospective analyses are known to be much more susceptible to selection and reporting bias, since the decision to treat a person is made subjectively. Gaberel 2012 did not compare placebo‐controlled versus open studies, which is another potential source of bias, since all outcomes, except for death, are made on subjective clinical grounds, and can be easily biased when the outcome assessor is not blinded to the treatment given.

We only included randomised clinical trials in our review, and performed several sensitivity analyses, which should yield less biased results. Since most studies did not describe whether outcomes were assessed by a blinded outcome assessor, sensitivity analyses were essential. Despite the fact that all study authors reported that confirmation of rebleeding was investigated, in many cases, the diagnosis of rebleed was confirmed by examination of the CSF. Because CSF examination is an unreliable test to confirm rebleeding, we were not always able to prove the diagnosis of rebleeding (Vermeulen 1983). Therefore, we decided to perform sensitivity analyses on reported versus confirmed (with confirmatory evidence on CT scan or at autopsy) rebleeding, cerebral ischaemia, and hydrocephalus. These different analyses showed similar results, so lack of confirmatory evidence of these complications appears to be of minor importance in our analyses. The analyses we performed on trials with a control treatment compared with those given placebo treatment showed similar reducing effects of antifibrinolytic treatment on rebleeding, and similar increasing effects on delayed cerebral ischaemia, whereas, hydrocephalus trials with a control treatment showed a tendency towards a beneficial effect compared with trials with placebo treatment, demonstrating a tendency towards increased hydrocephalus rates.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Antifibrinolytic treatment does not improve clinical outcome in people after aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, although it does reduce the risk of rebleeding. Based on the currently available data, there is no evidence to support routine treatment with antifibrinolytic drugs for people with subarachnoid haemorrhage from a presumed or proven aneurysmal origin.

Implications for research.

Over decades, the interval between initial haemorrhage and aneurysm treatment has reduced. This is not only attributable to the improved in‐hospital logistics and resources, but also to the earlier diagnosis and shorter transfer time of people to a centre that specialises in aneurysm treatment. The earlier assessment of people with an aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage inherently increases the rebleed rate, because the majority of rebleeds occur in the first hours after the initial haemorrhage. More detailed analysis of the time intervals between initial haemorrhage, start of antifibrinolytic treatment, and aneurysm treatment in relation to rebleeds may reveal a subgroup who could benefit from a reduction in rebleed rate by antifibrinolytic treatment.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 May 2022 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions not changed |

| 31 May 2022 | New search has been performed | We included one more major study with 813 participants (Post 2021), resulting in a total of 11 included studies involving 2717 participants. We updated the searches, and included a summary of findings table. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1998 Review first published: Issue 3, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 September 2013 | Feedback has been incorporated | Minor layout changes |

| 4 February 2013 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | A new subgroup analysis was added and the conclusions changed. |

| 4 February 2013 | New search has been performed | Updated searches completed and a new study added. We included one new study with 505 participants (Hillman 2002).This study is different in treatment timing and duration of therapy, and contributes 26.5% of all participants. The review now includes 10 trials and 1904 participants in total. |

| 21 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 7 February 2003 | New search has been performed | We added the results of the recently published STAR‐study, the second largest placebo‐controlled randomised trial of antifibrinolytic treatment in subarachnoid haemorrhage to the review. This study contributes 33% of all included participants in this review, and 39% of the participants included in the comparison of antifibrinolytic treatment versus placebo. We also added a plain language summary. |

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this review were supported by research grants from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (Nederlandse Hart Stichting). We thank Brenda Thomas and Joshua Cheyne for their help in developing and performing the new electronic database searches. We thank Hazel Fraser for her editorial advice.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy, 2022 update

ID Search Hits #1 MeSH descriptor: [Subarachnoid Hemorrhage] this term only 592 #2 MeSH descriptor: [Intracranial Hemorrhages] this term only 280 #3 MeSH descriptor: [Cerebral Hemorrhage] this term only 975 #4 MeSH descriptor: [Intracranial Aneurysm] this term only 443 #5 MeSH descriptor: [Rupture, Spontaneous] this term only 110 #6 #4 and #5 28 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Aneurysm, Ruptured] this term only 130 #8 MeSH descriptor: [Brain] explode all trees 11710 #9 MeSH descriptor: [Meninges] explode all trees 295 #10 #8 or #9 11983 #11 #7 and #10 10 #12 ((subarachnoid or arachnoid) near/6 (haemorrhage* or hemorrhage* or bleed* or blood*)):ti,ab,kw 2058 #13 MeSH descriptor: [Vasospasm, Intracranial] this term only 151 #14 ((cerebral or intracranial or cerebrovascular) near/6 (vasospasm or spasm)):ti,ab,kw 530 #15 (sah):ti,ab,kw 903 #16 #1 or #2 or #3 or #6 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 3535 #17 MeSH descriptor: [Antifibrinolytic Agents] explode all trees 781 #18 (anti‐fibrinolytic* or antifibrinolytic* or antifibrinolysin* or anti‐fibrinolysin* or antiplasmin* or anti‐plasmin* or (plasmin near/3 inhibitor*)):ti,ab,kw 1675 #19 (fibrinolysis near/3 (prevent* or inhib* or antag*)):ti,ab,kw 292 #20 MeSH descriptor: [Tranexamic Acid] this term only 1107 #21 ("4 amino methylcyclohexane carboxylate" or "4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid" or "4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or amca or AMCHA):ti,ab,kw 33 #22 (amchafibrin or amikapron or "aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid" or "aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or "aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid" or "aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid"):ti,ab,kw 17 #23 ("aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid" or "aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or "aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid" or "aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid" or amstat or anexan or antivoff or anvitoff orcaprilon or "cis 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or "cis aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid"):ti,ab,kw 4 #24 ("cl 65336" or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or cyklokapron or exacyl or fibrinon or frenolyse or hemostan or hexacapron or hexakapron or "kabi 2161" or kalnex or micranex or para "aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid"):ti,ab,kw 70 #25 (rikaparin or ronex or spotof or theranex or tramic or tranex or tranexam or "tranexamic acid" or "tranexanic acid" or tranexic or "trans 1 aminomethylcyclohexane 4 carboxylic acid" or "trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane 1 carboxylic acid" or "trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid"):ti,ab,kw 2963 #26 ("trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or "trans achma" or "trans amcha" or "trans aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid" or "trans aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid"):ti,ab,kw 3 #27 ("trans aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid" or transamin or "transaminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid" or "transexamic acid" or traxamic or trenaxin or ugurol):ti,ab,kw 31 #28 MeSH descriptor: [Aminocaproates] explode all trees 205 #29 (acikaprin or afibrin or amicar or "amino caproic acid" or "aminocaproic acid" or "aminohexanoic acid" or capracid or capramol or caproamin or caprocid or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisin or caprolisine or "caprolysin orcapromol"):ti,ab,kw 282 #30 ("cl 10304" or cl10304 or "cy 116" or cy116 or "e aminocaproic acid" or EACA or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicaprom or epsicapron or epsikapron or epsilcapramin or "epsilon amino caproate" or "epsilon amino caproic acid"):ti,ab,kw 114 #31 ("depsilon aminocaproate" or "epsilon aminocaproic acid" or "epsilonaminocaproic acid" or epsilonaminocapronsav or "etha aminocaproic acid" or "ethaaminocaproic acid" or "gamma aminocaproic acid" or "gamma aminohexanoic acid"):ti,ab,kw 165 #32 (hemocaprol or hepin or hexalense or ipsilon or "jd 177" or jd177 or neocaprol or "nsc 26154" or nsc26154 or resplamin or tachostyptan):ti,ab,kw 2 #33 MeSH descriptor: [Aprotinin] this term only 522 #34 ("9921 rp" or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin or apronitine or apronitrine or aprotimbin or "aprotinin bovine" or aprotinine or aprotonin or "bayer a 128" or "bayer a128" or "bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor" or contrical or contrycal or contrykal or "frey inhibitor" or gordox or haemoprot):ti,ab,kw 44 #35 (iniprol or "kallikrein trypsin inhibitor" or "kazal type trypsin inhibitor" or kontrikal or kontrycal or "Kunitz inhibitor" or "Kunitz trypsin inhibitor" or midran or "pancreas antitrypsin" or "pancreas secretory trypsin inhibitor" or "pancreas trypsin inhibitor"):ti,ab,kw 3 #36 ("pancreatic antitrypsin" or "pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor" or "pancreatic trypsin inhibitor" or "protinin orriker 52g" or rivilina or "rp 9921" or rp9921 or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trasylol or trazylol or "tumor associated trypsin inhibitor" or zymofren):ti,ab,kw 107 #37 ("4 aminomethylbenzoic acid" or "4 amino methylbenzoic acid" or "alpha amino para toluic acid" or "amino methylbenzoic acid" or "aminomethyl benzoic acid" or "aminomethylbenzoic acid" or PAMBA or "para aminomethylbenzoic acid" or "para amino methylbenzoic acid" or styptopur or styptosolut):ti,ab,kw 19 #38 MeSH descriptor: [Fibrinolysis] this term only and with qualifier(s): [antagonists & inhibitors ‐ AI, drug effects ‐ DE] 626 #39 #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 4899 #40 #16 and #39 123

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy, 2022 update

1. intracranial hemorrhages/ or cerebral hemorrhage/ or subarachnoid hemorrhage/ or hemorrhagic stroke/ 2. Intracranial Aneurysm/ 3. Rupture, Spontaneous/ 4. 2 and 3 5. Aneurysm, Ruptured/ 6. exp brain/ or exp meninges/ 7. 5 and 6 8. ((subarachnoid or arachnoid) adj6 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or bleed$ or blood$)).tw. 9. Vasospasm, Intracranial/ 10. ((cerebral or intracranial or cerebrovascular) adj6 (vasospasm or spasm)).tw. 11. SAH.tw. 12. 1 or 4 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 13. exp Antifibrinolytic Agents/ 14. (anti‐fibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolysin$ or anti‐fibrinolysin$ or antiplasmin$ or anti‐plasmin$ or (plasmin adj3 inhibitor$)).tw. 15. (fibrinolysis adj3 (prevent$ or inhib$ or antag$)).tw. 16. Tranexamic Acid/ 17. (4 amino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or amca or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anexan or antivoff or anvitoff orcaprilon or cis 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cis aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cl 65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or cyklokapron or exacyl or fibrinon or frenolyse or hemostan or hexacapron or hexakapron or kabi 2161 or kalnex or micranex or para aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or rikaparin or ronex or spotof or theranex or tramic or tranex or tranexam or tranexamic acid or tranexanic acid or tranexic or trans 1 aminomethylcyclohexane 4 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane 1 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or trans achma or trans amcha or trans aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or transamin or transaminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or transexamic acid or traxamic or trenaxin or ugurol).tw,nm. 18. exp Aminocaproic Acids/ 19. (acikaprin or afibrin or amicar or amino caproic acid or aminocaproic or aminohexanoic acid or beta aminocaproic acid or capracid or capramol or caproamin or caprocid or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisin or caprolisine or caprolysin orcapromol or cl 10304 or cl10304 or cy 116 or cy116 or e aminocaproic acid or EACA or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicaprom or epsicapron or epsikapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon amino caproic aci or depsilon aminocaproate or epsilon aminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocapronsav or etha aminocaproic acid or ethaaminocaproic acid or gamma aminocaproic acidor gamma aminohexanoic acidor hemocaprol or hepin or hexalense or ipsilon or jd 177 or jd177 or neocaprol or nsc 26154 or nsc26154 or resplamin or tachostyptan).tw,nm. 20. Aprotinin/ 21. (9921 rp or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin or apronitine or apronitrine or aprotimbin or aprotinin bovine or aprotinine or aprotonin or bayer a 128 or bayer a128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or contrical or contrycal or contrykal or frey inhibitor or gordox or haemoprot or iniprol or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor or kazal type trypsin inhibitor or kontrikal or kontrycal or Kunitz inhibitor or Kunitz trypsin inhibitor or midran or pancreas antitrypsin or pancreas secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreas trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic antitrypsin or pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic trypsin inhibitor or protinin orriker 52g or rivilina or rp 9921 or rp9921 or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trasylol or trazylol or tumor associated trypsin inhibitor or zymofren).tw,nm. 22. (4 aminomethylbenzoic acid or 4 amino methylbenzoic acid or alpha amino para toluic acid or amino methylbenzoic acid or aminomethyl benzoic acid or aminomethylbenzoic acid or PAMBA or para aminomethylbenzoic acid or para amino methylbenzoic acid or styptopur or styptosolut).tw,nm. 23. Fibrinolysis/ai, de [Antagonists & Inhibitors, Drug Effects] 24. or/13‐23 25. randomized controlled trial.pt. 26. controlled clinical trial.pt. 27. randomized.ab. 28. placebo.ab. 29. drug therapy.fs. 30. randomly.ab. 31. trial.ti. 32. groups.ab. 33. or/25‐32 34. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 35. 33 not 34 36. 12 and 24 and 35

Appendix 3. Embase search strategy, 2022 update

1. subarachnoid hemorrhage/ 2. brain hemorrhage/ or brain artery aneurysm rupture/ 3. brain vasospasm/ 4. exp Intracranial Aneurysm/ 5. exp rupture/ 6. 4 and 5 7. Aneurysm Rupture/ 8. exp brain/ or exp meninx/ 9. 7 and 8 10. ((subarachnoid or arachnoid) adj6 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or bleed$ or blood$)).tw. 11. ((cerebral or intracranial or cerebrovascular) adj6 (vasospasm or spasm)).tw. 12. SAH.tw. 13. 1 or 2 or 3 or 6 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. exp antifibrinolytic agent/ 15. (anti‐fibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolysin$ or anti‐fibrinolysin$ or antiplasmin$ or anti‐plasmin$ or (plasmin adj3 inhibitor$)).tw. 16. (fibrinolysis adj3 (prevent$ or inhib$ or antag$)).tw. 17. tranexamic acid/ 18. (4 amino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or amca or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anexan or antivoff or anvitoff orcaprilon or cis 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cis aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cl 65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or cyklokapron or exacyl or fibrinon or frenolyse or hemostan or hexacapron or hexakapron or kabi 2161 or kalnex or micranex or para aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or rikaparin or ronex or spotof or theranex or tramic or tranex or tranexam or tranexamic acid or tranexanic acid or tranexic or trans 1 aminomethylcyclohexane 4 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane 1 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or trans achma or trans amcha or trans aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or transamin or transaminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or transexamic acid or traxamic or trenaxin or ugurol).tw. 19. aminocaproic acid/ 20. (acikaprin or afibrin or amicar or amino caproic acid or aminocaproic acid or aminohexanoic acid or capracid or capramol or caproamin or caprocid or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisin or caprolisine or caprolysin orcapromol or cl 10304 or cl10304 or cy 116 or cy116 or e aminocaproic acid or EACA or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicaprom or epsicapron or epsikapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon amino caproic aci or depsilon aminocaproate or epsilon aminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocapronsav or etha aminocaproic acid or ethaaminocaproic acid or gamma aminocaproic acidor gamma aminohexanoic acidor hemocaprol or hepin or hexalense or ipsilon or jd 177 or jd177 or neocaprol or nsc 26154 or nsc26154 or resplamin or tachostyptan).tw. 21. aprotinin/ 22. (9921 rp or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin or apronitine or apronitrine or aprotimbin or aprotinin bovine or aprotinine or aprotonin or bayer a 128 or bayer a128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or contrical or contrycal or contrykal or frey inhibitor or gordox or haemoprot or iniprol or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor or kazal type trypsin inhibitor or kontrikal or kontrycal or Kunitz inhibitor or Kunitz trypsin inhibitor or midran or pancreas antitrypsin or pancreas secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreas trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic antitrypsin or pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic trypsin inhibitor or protinin orriker 52g or rivilina or rp 9921 or rp9921 or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trasylol or trazylol or tumor associated trypsin inhibitor or zymofren).tw. 23. 4 aminomethylbenzoic acid/ 24. (4 aminomethylbenzoic acid or 4 amino methylbenzoic acid or alpha amino para toluic acid or amino methylbenzoic acid or aminomethyl benzoic acid or aminomethylbenzoic acid or PAMBA or para aminomethylbenzoic acid or para amino methylbenzoic acid or styptopur or styptosolut).tw. 25. or/14‐24 26. Randomized Controlled Trial/ or "randomized controlled trial (topic)"/ 27. Randomization/ 28. Controlled clinical trial/ or "controlled clinical trial (topic)"/ 29. control group/ or controlled study/ 30. clinical trial/ or "clinical trial (topic)"/ or phase 1 clinical trial/ or phase 2 clinical trial/ or phase 3 clinical trial/ or phase 4 clinical trial/ 31. crossover procedure/ 32. single blind procedure/ or double blind procedure/ or triple blind procedure/ 33. placebo/ or placebo effect/ 34. (random$ or RCT or RCTs).tw. 35. (controlled adj5 (trial$ or stud$)).tw. 36. (clinical$ adj5 trial$).tw. 37. clinical trial registration.ab. 38. ((control or treatment or experiment$ or intervention) adj5 (group$ or subject$ or patient$)).tw. 39. (quasi‐random$ or quasi random$ or pseudo‐random$ or pseudo random$).tw. 40. ((control or experiment$ or conservative) adj5 (treatment or therapy or procedure or manage$)).tw. 41. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj5 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 42. (cross‐over or cross over or crossover).tw. 43. (placebo$ or sham).tw. 44. trial.ti. 45. (assign$ or allocat$).tw. 46. controls.tw. 47. or/26‐46 48. 13 and 25 and 47

Appendix 4. MEDLINE search strategy, 2013 publication

1. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage/ 2. intracranial hemorrhages/ or cerebral hemorrhage/ 3. Intracranial Aneurysm/ 4. Rupture, Spontaneous/ 5. 3 and 4 6. Aneurysm, Ruptured/ 7. exp brain/ or exp meninges/ 8. 6 and 7 9. ((subarachnoid or arachnoid) adj6 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or bleed$ or blood$)).tw. 10. Vasospasm, Intracranial/ 11. ((cerebral or intracranial or cerebrovascular) adj6 (vasospasm or spasm)).tw. 12. sah.tw. 13. 1 or 2 or 5 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. exp Antifibrinolytic Agents/ 15. (anti‐fibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolysin$ or anti‐fibrinolysin$ or antiplasmin$ or anti‐plasmin$ or (plasmin adj3 inhibitor$)).tw. 16. (fibrinolysis adj3 (prevent$ or inhib$ or antag$)).tw. 17. tranexamic acid/ 18. (4 amino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or amca or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anexan or antivoff or anvitoff orcaprilon or cis 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cis aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cl 65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or cyklokapron or exacyl or fibrinon or frenolyse or hemostan or hexacapron or hexakapron or kabi 2161 or kalnex or micranex or para aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or rikaparin or ronex or spotof or theranex or tramic or tranex or tranexam or tranexamic acid or tranexanic acid or tranexic or trans 1 aminomethylcyclohexane 4 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane 1 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or trans achma or trans amcha or trans aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or transamin or transaminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or transexamic acid or traxamic or trenaxin or ugurol).tw,nm. 19. exp Aminocaproic Acids/ 20. (acikaprin or afibrin or amicar or amino caproic acid or aminocaproic acid or aminohexanoic acid or capracid or capramol or caproamin or caprocid or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisin or caprolisine or caprolysin orcapromol or cl 10304 or cl10304 or cy 116 or cy116 or e aminocaproic acid or EACA or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicaprom or epsicapron or epsikapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon amino caproic aci or depsilon aminocaproate or epsilon aminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocapronsav or etha aminocaproic acid or ethaaminocaproic acid or gamma aminocaproic acidor gamma aminohexanoic acidor hemocaprol or hepin or hexalense or ipsilon or jd 177 or jd177 or neocaprol or nsc 26154 or nsc26154 or resplamin or tachostyptan).tw,nm. 21. Aprotinin/ 22. (9921 rp or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin or apronitine or apronitrine or aprotimbin or aprotinin bovine or aprotinine or aprotonin or bayer a 128 or bayer a128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or contrical or contrycal or contrykal or frey inhibitor or gordox or haemoprot or iniprol or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor or kazal type trypsin inhibitor or kontrikal or kontrycal or Kunitz inhibitor or Kunitz trypsin inhibitor or midran or pancreas antitrypsin or pancreas secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreas trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic antitrypsin or pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic trypsin inhibitor or protinin orriker 52g or rivilina or rp 9921 or rp9921 or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trasylol or trazylol or tumor associated trypsin inhibitor or zymofren).tw,nm. 23.( 4 aminomethylbenzoic acid or 4 amino methylbenzoic acid or alpha amino para toluic acid or amino methylbenzoic acid or aminomethyl benzoic acidor aminomethylbenzoic acid or PAMBA or para aminomethylbenzoic acid or para amino methylbenzoic acid or styptopur or styptosolut).tw,nm 24. Fibrinolysis/ai, de [Antagonists & Inhibitors, Drug Effects] 25. or/14‐24 26. 13 and 25 27. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 28. 26 not 27

Appendix 5. Embase search stragety, 2013 publication

1. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage/ 2. brain hemorrhage/ or brain artery aneurysm rupture/ 3. Brain Vasospasm/ 4. exp Intracranial Aneurysm/ 5. exp rupture/ 6. 4 and 5 7. Aneurysm Rupture/ 8. exp brain/ or exp meninx/ 9. 7 and 8 10. ((subarachnoid or arachnoid) adj6 (haemorrhage$ or hemorrhage$ or bleed$ or blood$)).tw. 11. ((cerebral or intracranial or cerebrovascular) adj6 (vasospasm or spasm)).tw. 12. sah.tw. 13. 1 or 2 or 3 or 6 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 14. exp antifibrinolytic agent/ 15. (anti‐fibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolytic$ or antifibrinolysin$ or anti‐fibrinolysin$ or antiplasmin$ or anti‐plasmin$ or (plasmin adj3 inhibitor$)).tw. 16. (fibrinolysis adj3 (prevent$ or inhib$ or antag$)).tw. 17. tranexamic acid/ 18. (4 amino methylcyclohexane carboxylate or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or amca or AMCHA or amchafibrin or amikapron or aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarbonic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanocarboxylic acid or aminomethylcyclohexanoic acid or amstat or anexan or antivoff or anvitoff orcaprilon or cis 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cis aminomethyl cyclohexanecarboxylic acid or cl 65336 or cl65336 or cyclocapron or cyclokapron or cyklocapron or cyklokapron or exacyl or fibrinon or frenolyse or hemostan or hexacapron or hexakapron or kabi 2161 or kalnex or micranex or para aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or rikaparin or ronex or spotof or theranex or tramic or tranex or tranexam or tranexamic acid or tranexanic acid or tranexic or trans 1 aminomethylcyclohexane 4 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane 1 carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans 4 aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or trans achma or trans amcha or trans aminomethyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or trans aminomethylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid or transamin or transaminomethylcyclohexane carboxylic acid or transexamic acid or traxamic or trenaxin or ugurol).tw. 19. aminocaproic acid/ 20. (acikaprin or afibrin or amicar or amino caproic acid or aminocaproic acid or aminohexanoic acid or capracid or capramol or caproamin or caprocid or caprogel or caprolest or caprolisin or caprolisine or caprolysin orcapromol or cl 10304 or cl10304 or cy 116 or cy116 or e aminocaproic acid or EACA or ecapron or ekaprol or epsamon or epsicaprom or epsicapron or epsikapron or epsilcapramin or epsilon amino caproate or epsilon amino caproic aci or depsilon aminocaproate or epsilon aminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocaproic acid or epsilonaminocapronsav or etha aminocaproic acid or ethaaminocaproic acid or gamma aminocaproic acidor gamma aminohexanoic acidor hemocaprol or hepin or hexalense or ipsilon or jd 177 or jd177 or neocaprol or nsc 26154 or nsc26154 or resplamin or tachostyptan).tw. 21. aprotinin/ 22. (9921 rp or antagosan or antilysin or antilysine or apronitin or apronitine or apronitrine or aprotimbin or aprotinin bovine or aprotinine or aprotonin or bayer a 128 or bayer a128 or bovine pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or contrical or contrycal or contrykal or frey inhibitor or gordox or haemoprot or iniprol or kallikrein trypsin inhibitor or kazal type trypsin inhibitor or kontrikal or kontrycal or Kunitz inhibitor or Kunitz trypsin inhibitor or midran or pancreas antitrypsin or pancreas secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreas trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic antitrypsin or pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor or pancreatic trypsin inhibitor or protinin orriker 52g or rivilina or rp 9921 or rp9921 or tracylol or trascolan or trasilol or traskolan or trasylol or trazylol or tumor associated trypsin inhibitor or zymofren).tw. 23. 4 aminomethylbenzoic acid/ 24. (4 aminomethylbenzoic acid or 4 amino methylbenzoic acid or alpha amino para toluic acid or amino methylbenzoic acid or aminomethyl benzoic acid or aminomethylbenzoic acid or PAMBA or para aminomethylbenzoic acid or para amino methylbenzoic acid or styptopur or styptosolut).tw. 25. fibrinolysis/pc [Prevention] 26. or/14‐25 27. 13 and 26 28. limit 27 to human

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials search strategy, 2022 update

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov)

( antifibrinolytics OR fibrinolysis OR antiplasmin OR tranexamic acid OR aminocaproic acids OR aprotinin ) AND AREA[StudyType] EXPAND[Term] COVER[FullMatch] "Interventional" AND AREA[ConditionSearch] ( subarachnoid hemorrhage OR intracranial hemorrhages OR cerebral hemorrhage OR brain aneurysm OR intracranial vasospasm ) AND AREA[StdAge] EXPAND[Term] COVER[FullMatch] ( "Adult" OR "Older Adult" ) AND AREA[StudyFirstPostDate] EXPAND[Term] RANGE[12/01/2012, 04/19/2021]

Appendix 7. WHO ICTRP search strategy, 2022 update

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch)

subarachnoid hemorrhage OR subarachnoid haemorrhage

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antifibrinolytic treatment versus control treatment with or without placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|