Abstract

Background:

Acne vulgaris (AV) is among the common skin diseases for which patients refer to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Aims and Objectives:

To investigate the approaches to CAM methods and factors believed to increase the disease in 1,571 AV patients.

Materials and Methods:

The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients and disease severity according to the Food and Drug Administration criteria were recorded. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) was used to assess the impact of acne on the patient's life and the history of CAM use was noted. The patients also listed the factors that they thought worsened their disease and reported their gluten-free diet experiences.

Results:

Of all the patients, 74.41% had a history of using CAM methods. CAM use was significantly higher in women, patients with severe AV, those with a higher CADI score and non-smokers. As a CAM method, 66.37% of the patients reported having used lemon juice. The respondents most frequently applied CAM methods before consulting a physician (43.94%), for a duration of 0–2 weeks (38.97%). They learned about CAM methods on the internet (56.24%) and considered CAM methods to be natural (41.86%). The patients thought that food (78.55%) and stress (17.06%) worsened their disease. They considered that the most common type of food that exacerbated their symptoms was junk food (63.84%) and a gluten-free diet did not provide any benefit in relieving AV (50%).

Conclusion:

Physicians need to ask patients about their CAM use in order to be able to guide them appropriately concerning treatments and applications with a high level of evidence.

KEY WORDS: Acne vulgaris, complementary and alternative medicine, dermatology, gluten, junk food

Background

Acne vulgaris (AV) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit. The frequent incidence of the disease, recurrence despite the treatment, young age-onset and persistence for many years, effect on visible areas such as the face, chest, and shoulders and scar formation and pigmentation can lead patients to explore and apply techniques outside the scope of modern medicine. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has been increasing in popularity in recent years, with the increasing number of patients that do not want to undergo chemical and pharmacological treatments seeking different methods.

CAM is defined as various healthcare systems, applications and products other than standard medical treatments.[1] CAM is categorized into five main categories, namely alternative medical systems (e.g., acupuncture), mind-body treatments (e.g., meditation), biological treatments (e.g., herbal treatment), manipulative and body-based practices (e.g., massage) and energy-focused therapies (e.g., Reiki).[2,3]

CAM use in dermatological diseases has been reported at a rate of 28.9%–69%.[4,5] AV is among the leading dermatological diseases in which CAM is used, like psoriasis vulgaris, contact dermatitis, fungal diseases and verruca.[6,7,8]

Objectives

This multi-centre study was conducted with the largest series in the literature to investigate CAM use in AV. The specific aims of the study were to determine whether the patients that presented to dermatology outpatient clinics with AV in Turkey used CAM techniques to relieve their symptoms, the methods they preferred, their reasons for referring to CAM methods, whether they found them beneficial, their recommendations concerning the use of CAM to other patients and views related to the factors that they thought negatively affected AV. In addition, we compared the responses of the participants from seven different regions of Turkey to investigate the effects of different cultural structures on CAM use.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged 12–50 years who were diagnosed with AV and followed up in dermatology outpatient clinics located in different regions of Turkey between March 1, 2020 and September 1, 2020 were included in the study.

Procedure

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the university for the study (19.02.2020/0124). The study protocol was registered at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov with the number NCT04538729. The survey questions were prepared by the researchers but not validated. The patients completed the survey on their own without any time limitations and directed any questions they had to their physician during the process. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) questionnaire was also administered to the patients, and the physicians recorded information concerning the clinical manifestation of the disease and disease severity according to the Food and Drug Administration criteria.[9,10]

Statistical analysis

The data of the study were analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) IBM v. 25.0 software package. The tests were conducted at a 95% confidence level. Demographic data and other variables were expressed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies, mean ± standard deviation, and percentage calculations. For non-normally– distributed continuous variables, such as age, CADI score, disease duration, smoking amount, and the number of days menstruating were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test, a non-parametric method, whereas the CAM group comparisons of the remaining variables were performed using the Chi-square test. For categorical variables, descriptive statistics were given as the frequency and percentage. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered to be of statistical significance.

Results

CAM use for AV according to demographic characteristics and disease involvement of the patients

A total of 1,571 patients, 1,141 women (72.60%) and 430 men (27.40%), were included in the study. Of the patients, 1,169 (74.41%) reported that they had used CAM for AV. The use of CAM in different groups are summarized in Table 1. The CAM use was statistically significantly higher in patients with the cheek (present 75.70%, absent 24.30%, P = 0.033) and chest involvement (present 79.80%, absent 20.20%, P = 0.015).

Table 1.

CAM use according to demographic characteristics and disease involvement

| History of CAM use | Overall | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Present | Absent | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Mean | 21.42±7.56 | 21.50±5.6 | 21.44±7.12 | 0.771 | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 898 | 78.70 | 243 | 21.30 | 1141 | 72.60 | 0.000 |

| Male | 271 | 63.00 | 159 | 37.00 | 430 | 27.40 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married | 85 | 67.50 | 41 | 32.50 | 126 | 8.00 | 0.064 |

| Single | 1082 | 75.00 | 361 | 25.00 | 1443 | 92.00 | |

| Education level | |||||||

| None, literate, primary school, middle school | 89 | 70.10 | 38 | 29.90 | 127 | 8.10 | 0.475 |

| High school, college | 470 | 74.50 | 161 | 25.50 | 631 | 40.40 | |

| Undergraduate, postgraduate | 605 | 75.20 | 200 | 24.80 | 805 | 51.50 | |

| Income level* | |||||||

| 300$ and below | 174 | 74.00 | 61 | 26.00 | 235 | 15.30 | 0.102 |

| 300-650$ | 533 | 76.70 | 162 | 23.30 | 695 | 45.20 | |

| 650-1,300$ | 332 | 72.80 | 124 | 27.20 | 456 | 29.70 | |

| above 1,300$ | 102 | 67.50 | 49 | 32.50 | 151 | 9.80 | |

| Acne severity classification according to FDA | |||||||

| Group 1 | 140 | 64.80 | 76 | 35.20 | 216 | 13.90 | 0.003 |

| Group 2 | 422 | 73.80 | 150 | 26.20 | 572 | 36.70 | |

| Group 3 | 404 | 77.50 | 117 | 22.50 | 521 | 33.40 | |

| Group 4 | 193 | 77.20 | 57 | 22.80 | 250 | 16.00 | |

| CADI score | |||||||

| Mean | 7.65±3.8 | 6.66±4.12 | 7.39±4.05 | 0.000 | |||

| Disease duration (months) | |||||||

| Mean | 53.7±39.7 | 53.91±48.45 | 53.75±42.07 | 0.058 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Non-smoker | 903 | 76.00 | 285 | 24.00 | 1188 | 83.60 | 0.035 |

| Smoker | 172 | 73.80 | 61 | 26.20 | 233 | 16.40 | |

| Smoking pack years | 1.64±11.17 | 1.2±2.98 | 1.51±9.95 | 0.035 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | |||||||

| None | 954 | 75.20 | 315 | 24.80 | 1269 | 80.90 | 0.013 |

| Regular | 10 | 47.60 | 11 | 52.40 | 21 | 1.30 | |

| Social | 203 | 72.80 | 76 | 27.20 | 279 | 17.80 | |

| Family history of AV | |||||||

| Absent | 593 | 75.50 | 192 | 24.50 | 785 | 50.00 | 0.305 |

| Present | 576 | 73.30 | 210 | 26.70 | 786 | 50.00 | |

| Present | 47 | 71.20 | 19 | 28.80 | 66 | 4.20 | |

CADI, Cardiff Acne Disability Index. FDA, Food and Drug Administration CAM, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. *Income level was calculated based on the exchange rate at the time of the study

As medical therapy options, 65.12% of the patients had previously used topical treatments, 35.33% oral antibiotics, 18.27% systemic isotretinoin, and 37.62% cosmetics, whereas 6.11% had not received any medical therapy. Of the female participants, 7.01% used birth control pills. The use of CAM was statistically significantly higher among patients using topical treatments (77.03% vs. 22.97%, P = 0.001) and those using cosmetics to conceal their acne (82.23% vs. 17.77%; P = 0.000).

CAM methods used for AV, the duration of use, from whom they learned and their recommendations to other patients

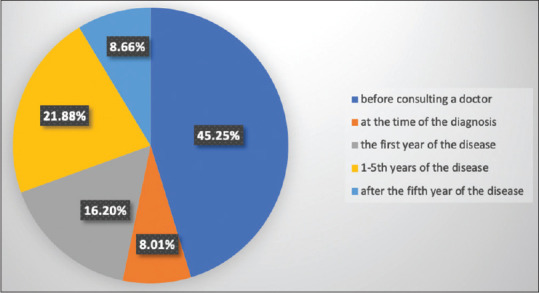

The CAM methods preferred by the patients are summarized in Table 2. The patients most frequently used lemon juice (66.37%). They mostly applied these methods before consulting a doctor (43.94%) [Figure 1]. The duration of CAM use was 0–2 weeks (38.97%), 2–4 weeks (28.66%), 1–6 months (19.17%), and longer than 6 months (10.13%). The patients often heard about CAM methods on the internet via search engines such as Google (56.24%), from friends (34.36%) and on social media such as Instagram, Facebook or Twitter (32.55%). The respondents often applied CAM when their AV lesions were mild (41.59%), worsened (35.62%) or recurred (28.93%), and 18.90% when the treatments they used no longer relieved their symptoms. Of all the patients with a CAM history, 95.21% had applied it to the facial area. Almost a quarter of patients with a CAM use history (22.06%) stated that CAM practitioners to whom they had referred had no healthcare training, and 17.63% were not aware of the profession of the practitioner. When asked whether they would recommend CAM to other patients, 41.95% of the patients stated that they would not, whereas 8.77% would, and the remaining patients were indecisive.

Table 2.

CAM methods preferred by the patients

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Lemon juice | 734 | 66.37 |

| Vinegar | 408 | 36.89 |

| Homemade creams | 330 | 29.84 |

| Food supplements | 157 | 14.20 |

| Herbal supplements | 130 | 11.75 |

| Herbal creams | 383 | 34.63 |

| Thermal springs | 105 | 9.49 |

| Wet cupping | 27 | 2.44 |

| Leech therapy | 12 | 1.08 |

| Special diet | 74 | 6.69 |

| Massage | 25 | 2.26 |

| Acupuncture | 10 | 0.90 |

| Homeopathy | 6 | 0.54 |

| Bioresonance | 2 | 0.18 |

| Cupping | 7 | 0.63 |

| Ozone therapy | 12 | 1.08 |

| Hypnosis | 2 | 0.18 |

| Meditation | 25 | 2.26 |

| Other | 78 | 7.05 |

CAM, Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Total percentage exceeds 100% as more than one response was allowed

Figure 1.

When did the patients use complementary and alternative medicine methods?

Satisfaction with CAM, the reasons for referring to CAM, and informing the physician about use

Of the patients, 79.84% stated that their lesions did not resolve with CAM, whereas 6.33% reported that they had worsened the lesions. Of those considering CAM to be beneficial, 25.77% reported such benefits for acne lesions, 14.56% for oily skin, 7.05% for scars and 6.96% for pigmentation. The responses of the patients concerning their reasons for referring to CAM are summarized in Table 3. Of the patients with a history of CAM, 44.76% mentioned that at the time they started to use CAM, they either had not yet started medical therapy or stopped their ongoing therapy without consulting their physician. In addition, 35.44% used the treatment prescribed by the physician regularly, whereas 12.66% only used it occasionally. The patients mostly reported that their physicians did not ask about their CAM use (62.93%), and nearly half the patients did not spontaneously inform their physicians about their use (51.54%). Among the patients sharing this information with their physicians, there were those stating that their physicians recommended stopping CAM (21.55%), did not interfere with their CAM use (13.31%), told them they could continue using CAM (17.75%) and did not care or were unresponsive (47.39%).

Table 3.

Patients’ responses concerning their reasons for using CAM

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Seen no benefit from modern drugs | 169 | 15.28 |

| Thought it would prevent disease recurrence | 254 | 22.97 |

| Became tired of recurrence and decided to seek an alternative method | 310 | 28.03 |

| Natural and safe without side effects | 463 | 41.86 |

| Cheap | 86 | 7.78 |

| More reliable than modern medicine | 38 | 3.44 |

| Easier to reach | 283 | 25.59 |

| Don’t know | 136 | 12.30 |

| Other | 31 | 2.80 |

Total percentage exceeds 100% as more than one response was allowed

The point of view of the patients who did not use CAM

The patients without a history of CAM use were also asked to present their views on CAM, and 63.16% stated that they did not find it reliable or safe, 41.60% considered it nonsensical and useless, 39.85% thought it had no medical basis, and 29.57% said that they were concerned about the side effects. When asked whether they would use CAM in future, 49.37% stated that they would not, 28.32% stated that they would if not harmful, 20.80% thought they might use it, and 6.52% were planning to try it.

Factors believed to trigger the disease

The patients considered that various foods (78.55%), stress (17.06%), and habits such as smoking (8.91%) and alcohol (6.14%) worsened their illness [Table 4], wheereas 11.45% did not think any food or habit exacerbated their disease.

Table 4.

Patients’ thoughts on food and habits exacerbating acne vulgaris

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sunflower seeds | 958 | 60.98 |

| Nuts | 474 | 30.17 |

| Hot-tasting food | 251 | 15.98 |

| Spicy food | 330 | 21.01 |

| Milk/dairy products | 253 | 16.10 |

| Junk food, such as crisps | 1003 | 63.84 |

| Fried food | 671 | 42.71 |

| Offal | 56 | 3.56 |

| Beverages with coloring, such as coke | 469 | 29.85 |

| Refined sugar, chocolate | 747 | 47.55 |

| Fatty food | 741 | 47.17 |

| Chicken | 99 | 6.30 |

| Red meat | 59 | 3.76 |

| Fish/fish oil | 38 | 2.42 |

| Hormone-injected vegetables/fruit | 114 | 7.26 |

| Alcohol | 97 | 6.17 |

| Wheat and wheat products | 33 | 2.10 |

| Eggplant | 36 | 2.29 |

| Tomato | 117 | 7.45 |

| Ketchup/mayonnaise | 356 | 22.66 |

| Paste/sauces | 147 | 9.36 |

| Gluten | 108 | 6.87 |

| Smoking | 140 | 8.91 |

| Stress | 268 | 17.06 |

| Lack of sleep | 125 | 7.96 |

| Various food products | 1234 | 78.55 |

| Nothing | 180 | 11.45 |

| Other | 36 | 2.29 |

Total percentage exceeds 100% as more than one response was allowed

Of the patients, 7.38% had previously tried a gluten-free diet, and 50% of these patients considered that this diet did not help relieve their AV, 41.6% thought that it reduced the lesions and 25.83% reported reduced seborrhea symptoms.

Discussion

Studies commenting on the relationship between CAM use and AV are generally those investigating CAM use in dermatological diseases as a general category. When the frequency of CAM use among general dermatological diseases is examined, AV is observed to be among the top three diseases.[6,7,11,12] Compared to other dermatological diseases, the frequency of CAM use in patients with AV is 2.5–3 times greater.[11] In these studies, the rate of CAM use in patients with AV is reported in a very wide range from 14.8% to 71.3%.[8,13] To our knowledge, there is only one study in the literature investigating CAM use specifically in patients with AV.[14] In that study, of the 657 patients with AV, 77% were reported to have a history of CAM use, which is similar to our finding [74.41%].

In our study, the rate of CAM use was statistically significantly higher in women and those with higher AV severity and CADI scores. In the literature, some publications reported a high rate of CAM use in women, whereas others did not find a relationship between CAM use and gender.[6,13,14,15] In a study conducted in Korea, 90% of the AV patients referred to CAM when their lesions increased and their disease worsened.[16] This is similar to our results concerning the higher use of CAM among the patients with more severe acne and those with higher CADI scores. In addition, consistent with our findings, many previous researchers did not determine a relationship between CAM use and the duration of the disease involvement, patient age, and education level.[6,13,14]

The majority of our patients (66.37%) stated that they used lemon juice as a CAM method. This was followed by other methods such as vinegar, herbal cream, and creams and masks prepared by the patients themselves. Bioresonance and hypnosis methods, which are rarely used in Turkey, were applied for AV treatment only at a rate of –0.18%. These responses show that AV patients usually try products that are easily found in their homes. In previous studies conducted with general dermatology patients in Turkey, lemon juice was found to be the most common CAM method used by patients with AV (rate reported as –% in one study and not specified in another).[6,8] In a study conducted in Iran, honey was most frequently used as the CAM method at a rate of 53.4%, whereas lemon juice ranked fourth at 29.7%. As in our study, the frequent use of lemon juice in studies conducted in Turkey can be due to the effect of geographical differences on CAM method choices. Whereas the use of vinegar was the second most common method in our study, it was reported in previous studies at a rate of 5.9% among the commonly used non-herbal treatments or as apple cider vinegar.[13,14] In other studies, it was found that herbal topical treatments were frequently used in AV patients at a rate of 62%–100%.[13,15] In the current study, although this rate was not as high as in previous studies, it was still very high at 34.63%. This shows that patients mostly rely on treatments derived from plants.

In a study in which patients with AV and psoriasis were evaluated together, it was reported that CAM was most frequently used before starting medical therapy (69.9%).[13] Our patients also used CAM methods most frequently before consulting a physician (43.94%) and for a short duration; i.e., 0–2 weeks (38.97%). This shows that patients think that they can resolve their problem on their own without consulting a physician, or that they do not take the disease as serious enough to visit a hospital and consider it a disease that can be cured by simple methods. However, the short-term use of CAM can be interpreted as that patients often get bored with CAM quickly and quit these methods because they do not see any benefit.

Our patients mostly heard about CAM methods on the internet (56.24%), (34. through social media (32.55%) and from friends (34.36%). In previous studies, unlike our sample, patients mostly stated that they heard about this method from their friends.[13,14,15] AV is a common disease in the young population. As internet literacy is better in this age group, it is expected that they would learn about CAM methods on the internet. Similarly, asinformation acquired from friends is valuable for this age group, it is also not surprising to determine friends as the second source in the current study.

In this study, the patients mostly used CAM methods because they considered them to be natural with no side effects (41.86%). Similarly, in another study, 58.9% of the patients used CAM because they thought it was natural.[13] This suggests that these patients do not think that CAM can harm their bodies, and therefore they should be informed about the possible negative effects of such treatments. During CAM use, 41.95% of the patients did not continue their medical therapy, but 35.44% used the medications prescribed by their physicians along with CAM. Previous research reported a similar rate of patients (28.4%) that used physician-prescribed treatment together with CAM.[13] In the current study, 41.95% of the patients with a history of CAM use stated that they would not recommend it to other patients, which indicates that they did not trust these methods sufficiently to recommend them to others.

Of our patients with a history of CAM use, 62.93% stated that their physicians did not inquire about their CAM use, and 51.54% of these patients did not spontaneously inform their physicians about their use. Among the patients that shared this information with their physicians, 47.39% noted that their physicians either did not care or were unresponsive. In a previous study, only 1.3% of the physicians were reported to have asked their patients about the use of CAM methods.[13] Although this rate was higher in our study, we observed that physicians mostly ignored this situation or did not show any interest.

There are various theories about the relationship between acne and diet. Our patients considered that mostly junk foods such as crisps rich in trans-fats and less frequently sugary and fatty foods exacerbated their AV. This situation can be interpreted as the increasing awareness of the public concerning the harmful consequences of diets rich in refined sugar and trans and saturated fat, which are part of the Western diet, in AV lesions. However, only 16.10% of our patients considered that milk and dairy products, which are another component of the Western diet, worsened their AV lesions.

Whether AV lesions cause stress in the patient or stress itself causes AV, it is certain that there is a relationship between the two; exposure to stress decreases anti-inflammatory response through corticotropin-releasing hormone and accelerates lipogenesis in sebaceous glands by increasing growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).[17,18] In previous studies, 50%–82% of patients stated that their acne lesions increased with exposure to stress.[19,20,21] In the current study, stress affected our patients' AV lesions at a much lower rate (17.6%) than in previous studies.

The relationship between a gluten-free diet and AV remains unclear. However, as the number of people following a gluten-free diet has increased in recent years, this diet modification is also seen in AV patients. Of all our patients, 6.87% thought that gluten worsened their AV, and 7.38% had previously tried a gluten-free diet to reduce their symptoms. Half of the respondents stated that they did not benefit from this diet in terms of AV, whereas 41.6% of those that considered it beneficial noted that it decreased their AV lesions. A previous study reported that a gluten-free diet was a habit change seen in AV patients. The authors attributed this to the similar age groups of gluten-free dieters and AV patients (19–44 years) and patients' belief that removing gluten from their diet would reduce their lesions.[22]

Herbal treatments are the most investigated CAM methods in AV due to their anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects. Local factors play an important role in the use of herbal treatments, especially in Far Eastern and Chinese medicine, and some studies have obtained a high level of evidence concerning the benefits of such treatments. Herbal treatments that have been previously investigated in terms of antioxidant and antibacterial properties include Matricaria recutita, Calendula officinalis, tannin, 50% aloe vera gel, 2% green tea lotion, 5% tea tree oil, traditional Nigerian products, Vitex agnus, and citrus essential oil.[23,24,25,26,27]

Other CAM methods used by patients with acne can be listed as mindfulness-based cognitive hypnotherapy, acupuncture, wet cupping, application of food products such as honey, yoghurt and vinegar, dietary restrictions on milk, sugar and chocolate, food supplements such as zinc, nicotinamide, and fish oil, and application of urea to the face due to its content.[14,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] There are significant differences between countries concerning the rate of patients' use of these methods. In our study, lemon juice, a plant that widely grows in Turkey, was found to be the most common. In addition, the use of clay masks, rose water, yoghurt, sulfur soaps, honey, and topical herbal creams is reported in Turkey.[13,15]

The limitation of the study is that data were obtained from a survey and thus based on the statements of the patients.

Conclusion

Due to its chronic and recurrent nature, AV is one of the diseases for which patients frequently refer to CAM methods. The use of CAM is more common in women and patients with severe AV. In this study, the patients mostly resorted to CAM as they thought it was natural and safe with no side effects and they were tired of the recurrent nature of the disease. The patients mostly did not share their CAM use with their physicians, and they also did not care whether the practitioner of these methods had any healthcare training or had a health-related profession. The high rate of CAM use among the respondents in the study shows the necessity of dermatologists to ask their patients about CAM use and guide them appropriately. In light of these data, physicians need to question the use of CAM in AV patients, inform them about possible side effects such as irritation that may occur due to the frequent use of CAM, and know pharmacological treatments with a high level of evidence to be able to guide their patients appropriately in this field.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 07]. Available from: http://nccam.nih.gov/

- 2.Tükenmez Demirci G, Altunay İ, Küçükünal A, Mertoğlu E, Sarıkaya Solak S, Atış G. Complementary and alternative medicine usage in skin diseases and the positive and negative impacts on patients. Turk J Dermatol. 2012;6:150–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doğan B, Karabudak Auaf Ö, Karabacak E. Complementary and alternative medicine and dermatology. Turk Derm. 2012;46:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst E. The usage of complementary therapies by dermatological patients: A systemic review. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:857–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni H, Simile C, Hardy AM. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine by United States adults: Results from the 1999 national health interview survey. Med Care. 2002;40:353–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonul M, Gul U, Kulcu Cakmak S, Kılıc S. Unconventional medicine in dermatology outpatients in Turkey. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:639–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutlu S, Ekmekçi TR, Köşlü A, Purisa S. Complementary and alternative medicine among patients attending to dermatology outpatient clinic. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2009;29:1496–502. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bilgili SG, Ozkol HU, Karadag AS, Calka O. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among dermatology outpatients in Eastern Turkey. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014;33:214–21. doi: 10.1177/0960327113494904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motley RJ, Finlay AY. Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb02521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atsü N, Seçkin D, Özaydın N, Çalı S, Demirçay Z, Ergun T. Validity and reliability of Cardiff Acne Disability Index in Turkish acne patients. Turkderm. 2010:44:25–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dastgheib L, Farahangiz S, Adelpour Z, Salehi A. The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among dermatology outpatients in Shiraz, Iran. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22:731–5. doi: 10.1177/2156587217705054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivamani RK, Morley JE, Rehal B, Armstrong AW. Comparative prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among outpatients in dermatology and primary care clinics. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1363–5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullaaziz M, Baysal Akkaya V, Erturan İ. Evaluation of the use of complementary and alternative therapy in patients with psoriasis and acne vulgaris. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;53:60–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad A, Alghanemi L, Alrefaie S, Alorabi S, Ahmad G, Zimmo S. The use of complementary medicine among acne vulgaris patients: Cross sectional study. J Dermatol Dermatol Surg. 2017;21:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durusoy Ç, Tülin Güleç A, Durukan E, Bakar C. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with acne vulgaris or melasma in dermatology clinic: A questionnaire survey. Turk J Dermatol. 2010;4:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suh DH, Shin JW, Min SU, Lee DH, Yoon MY, Kim NI, et al. Treatment-seeking behaviors and related epidemiological features in Korean acne patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;6:969–74. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.6.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aslan Kayiran M, Karadag AS, Jafferany M. Psychodermatology of acne: Dermatologist's guide to inner side of acne and management approach. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14150. doi: 10.1111/dth.14150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griesemer RD. Emotionally triggered disease in a dermatologic practice. Psychiatr Ann. 1978;8:407–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh DH, Kim BY, Min SU, Lee DH, Yoon MY, Kim NI, et al. A multicenter epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Korea. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:673–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho YJ, Lee DH, Hwang EJ, Youn JI, Suh DH. Analytic study of the patients registered at Seoul National University Hospital Acne Clinic. Korean J Dermatol. 2006;44:798–804. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poli F, Dreno B, Verschoore M. An epidemiological study of acne in female adults: Results of a survey conducted in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:541–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arslain K, Gustafson CR, Baishya P, Rose DJ. Determinants of gluten-free diet adoption among individuals without celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Appetite. 2021;156:104958. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraft K. Erkrankungen der Haut (2)-Weitere Ekzemformen, Akne und Pruritus. Zeitschrift fü Phytotherapie. 2007;28:129–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orafidiya LO, Agbani E, Oyedele A, Babalola OO, Onayemi O. Preliminary clinical tests on topical preparations of Ocimum gratissimum Linn Leaf essential oil for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Drugs Under Invest. 2002;2:313–9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magin PJ, Adams J, Pond CD, Smith W. Topical and oral CAM in acne: A review of the empirical evidence and a consideration of its context. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14:62–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasri H, Bahmani M, Shahinfard N, Moradi Nafchi A, Saberianpour S, Rafieian Kopaei M. Medicinal plants for the treatment of acne vulgaris: A review of recent evidences. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2015;8:e25580. doi: 10.5812/jjm.25580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou HS, Bonku EM, Zhai R, Zeng R, Hou YL, Yang ZH, et al. Extraction of essential oil from Citrus reticulate Blanco peel and its antibacterial activity against Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) Heliyon. 2019;5 12:e02947. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shenefelt PD. Mindfulness-based cognitive hypnotherapy and skin disorders. Am J Clin Hypn. 2018;61:34–44. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2017.1419457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong T, Wu L. Clinical observation on pricking bloodletting therapy at Back-Shu acupoints plus Chinese herbal mask in treating patients with acne. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2013;11:286–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao H, Yang G, Wang Y, Liu JP, Smith CA, Luo H, et al. Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD009436. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juhl C, Bergholdt H, Miller I, Jemec G, Kanters J, Ellervik C. Dairy intake and acne vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 78,529 children, adolescents, and young adults. Nutrients. 2018;10:1049. doi: 10.3390/nu10081049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suppiah T, Sundram T, Tan E, Lee CK, Bustami NA, Tan CK. Acne vulgaris and its association with dietary intake: A Malaysian perspective. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2018;27:1141–5. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.072018.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delost GR, Delost ME, Lloyd J. The impact of chocolate consumption on acne vulgaris in college students: A randomized crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:220–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurnee EA, Kamath S, Kruse L. Complementary and alternative therapy for pediatric acne: A review of botanical extracts, dietary interventions, and oral supplements. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:596–601. doi: 10.1111/pde.13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Totri CR, Matiz C, Krakowski AC. Kids these days: Urine as a home remedy for acne vulgaris? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:47–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]