Abstract

Faced with multiple pressures from family, study, employment and interpersonal relationship management, college students are more likely to suffer from mental health problems. At present, psychological intervention in China mainly focuses on drugs and interviews, ignoring the important role played by the family as a bio-psycho-social unit, and there are certain cultural compatibility differences. As an important activity in family life, family rituals have been widely used in the treatment of diseases or mental health in western countries. In contrast, in China, the public’s attention and application of family rituals are obviously insufficient, and the relevant academic research results are relatively rare. In view of this, this paper adopts mathematical statistics method to clarify the internal relationship between family rituals and subjective well-being of college students, and verify the mediating role of family system in it, so as to provide effective suggestions for psychological health intervention of college students. The results showed that: Family rituals, family system and subjective well-being are correlated in pairs, showing a significant positive correlation; Family rituals and family system have significant predictive effects on subjective well-being of college students; The cohesion and adaptability play part of mediating roles between college students’ family rituals and subjective well-being.

Keywords: Family rituals, Family system, Subjective well-being, Chinese college students

Introduction

According to 2019 Blue Book on Depression in China, more than 350 million people around the world suffer from depression, with an increase rate of 18% and a potential risk of a younger age (Depression Research Institute, 2020). On July 24, 2019, China Youth Daily launched a survey on college students’ depression on Sina Weibo, and found that more than 20% of the more than 300,000 respondents believed they had a serious tendency toward depression (Bai & Ma, 2019). A cross-sectional study on depression among Chinese college students was conducted through meta-analysis, and the results showed that the prevalence of depression among college students in recent ten years was as high as 31.38% (Wang et al., 2020). College students are in the important transition stage of life, facing pressure from school, family, society and other aspects, and are more prone to suffer from psychological problems (Li, 2009), therefore, how to improve the subjective well-being of college students and reduce the occurrence of depression has always been a hot topic of social concern (Diener & Chan., 2011) and also an indispensable positive indicator to measure individual mental health (Greenspon & Saklofske, 2001). Therefore, Cultivating positive cognitive behavior can effectively relieve depression of college students (Seligman et al., 2006).

As an important special event in family life, family rituals convey emotional energy through interaction and have a profound influence on personal subjective well-being (Fiese et al., 2006), so it has been widely used in disease and psychological treatment. In contrast, the Chinese approach to psychological treatment is still dominated by drugs and interviews, ignoring the important role of the family as a bio-psycho-social unit (Rivett & Street, 2009). The reason is that the traditional Chinese idea of “wash your dirty linen at home” has caused great obstacles to family interview (Yao, 2018). Therefore, introducing family rituals into college students’ mental health treatment may be an effective intervention path. Some scholars have explored the relationship between family rituals and subjective well-being based on the context of western countries (Crespo et al., 2011), but the specific mechanism of action has yet to be clarified. At present, research on family rituals focuses on the following three aspects: membership relationship (Kiser et al., 2005), adolescents’ physical and mental health (Homer et al., 2007) and the application of family rituals in family therapy (Buchbinder et al., 2009). However, family rituals are based on the context of family, which itself is a complex and complete system, and the problems of any member cannot be understood independently of the family system (Minuchin, 1985), nor can the interaction between levels be explained by a simple linear causal relationship (Cox & Paley, 1997). Therefore, it is necessary to introduce the family system into the study of family rituals and the psychology and behavior of family members, thus helping us better understand the operation mechanism of family rituals (Miller et al., 2000).

According to the interaction ritual chains theory, members will generate emotional energy in the process of participating in the interaction rituals, which will have an impact on personal perception (Collins, 2004, pp.47). Family rituals, as interaction rituals, can define individuals’ self and family roles, and convey family members’ feelings towards each other and the family through participation in an orderly and predictable event, which in turn generates strong emotional energy and conveys the sense of belonging and trust associated with well-being in the form of emotional commitment. On the other hand, based on family system theory, family is an interactive system in which members rely on and interact to influence each other’s behavior (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). This theory states that patterns of interaction between family members call forth, maintain, and perpetuate both problem and non-problematic behavior (Johnson & Ray, 2016). When confronted with external pressure, not only individuals or subsystems in the family respond, but also the whole family system plays a role. Family system theory conceptualizes the interactions within the family that can have a profound impact on individuals over time (Minuchin, 1985).

In view of this, by introducing the family system as the mediating variable of the influence of family rituals on subjective well-being, this paper aims to clarify the mechanism of family rituals from the perspectives of both symbolic qualities and routine aspects (Fiese, 1992), so as to attract more scholars to pay attention to the influence of family rituals on adolescent mental health under the Chinese scenario, and provide effective suggestions for the effective prevention of college students’ mental illness. In order to achieve the research objectives, this paper will review the literature and scales related to family rituals in western academia, and design a more complete questionnaire on family rituals. In addition, most of the previous studies on family rituals were based on Caucasians and adolescents, and this study will focus on Chinese college students to make up for the lack of a sample.

Specifically, four questions will be addressed in the study: (1) What are the effects of family rituals on college students’ subjective well-being?; (2) How do family rituals affect family system?;(3)What is the influence of family system on college students’ subjective well-being?;(4)What role does the family system play in the influence of family rituals on college students’ subjective well-being? Based on this, practical implications suitable for the Chinese context are discussed, so as to encourage more Chinese families to pay attention to the mental health of their children, and provide effective suggestions for the effective prevention of mental illness among college students in China.

Literature review

Family rituals

As early as the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, ritual has been proposed as a means to distinguish sacred and secular, and used to analyze the relationship between myth, ritual and religion. Among them, the classical evolutionary school takes ritual as the source of religion and culture(Li et al., 2018). As an important research object of ritual research, family rituals refer to the special activities that occur repeatedly in family life, which are both symbolic and procedural, and help to stabilize family relations and members’ sense of belonging (Fiese et al., 2002). Although “ritual” and “routine” are often used interchangeably in family ritual studies, there are significant differences in communication, commitment and continuity between them. Routine focus on the task itself and are stable and instrumental, while rituals are emotional, symbolic and flexible to adjust as circumstances change. Therefore, this article deals with rituals rather than routines or conventions.

There are a lot of classic research on family rituals. For example, Bossard and Boll (1949) were the first to investigate family rituals and listed 20 common rituals in family life. Reiss (1982) carried out research on family rituals for different family types. Wolin and Bennet began to systematically sort out family rituals in 1984, and proposed four kinds of rituals generally applicable to families based on the occurrence situation of rituals, including family celebration, family tradition, life-cycle related rituals and daily rituals of families (Wolin & Bennet, 1984).

Western academic circles have long recognized the important impact of family rituals on individuals and families (Wolin et al., 1980) and carried out empirical studies on different populations. The results show that meaningful family rituals can improve marital satisfaction and relieve early parenting stress (Fiese & Kline, 1993). At the same time, family rituals are closely related to adolescents’ mental health, and will affect adolescents’ sense of identity, belonging, self-esteem (Fiese, 1992) and happiness (Crespo et al., 2011). Through the development of family rituals, various negative outcomes can be reduced, such as drug overuse, depression and suicide ideation (Malaquias et al., 2015). In addition, family rituals can be used as an intervention strategy for family therapy, It is used to relieve chronic pain of patients (Crespo et al., 2013), reduce alcoholism in the next generation (Wolin & Bennet, 1984), and help patients catharsis (Buchbinder et al., 2009).

Family system

Family is an organization form of social life formed by marriage, blood relationship and adoptive relationship. With the development of general systems theory, psychologists and ecologists began to apply systems theory to family studies (Cox & Paley, 2003).

The study of family system originated in the middle of the 20th century and formed two main theoretical perspectives in the process of development. One is the result orientation, which emphasizes the interpretation of system characteristics. Representative theories include Beavers’ family system model, Olson’s circumpolar model theory and Heidelberg School’s family dynamics theory (Li et al., 2012). The other is process-centered research on the tasks that the family system needs to perform properly, represented by McMaster’s family function model, Barnhill’s system theory model of healthy family cycle and Skinner’s family process model (Minuchin, 1985; Xu & Zhao, 2017, 2018). Among them, Olson’s circumpolar model and the corresponding Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES) are widely used to evaluate and conceptualize family system. The theory proposes three core dimensions of family systems: adaptability, cohesion and communication. Among the three dimensions, adaptability is used to evaluate the changes of family leadership, role relationships and relationship rules in the face of external pressure. Cohesion is used to measure the emotional connection between family members. Communication is the third dimension of circular model theory and is the key to promote the development of the other two dimensions (Olson, 1986).

The research on family system is mainly carried out from three aspects: cognition, behavior and romantic relationship. From the perspective of cognition, family system can affect children’s emotion regulation, emotion perception, self-esteem level (Xu & Zhao, 2017) and mental health (Ma et al., 2011). From the perspective of behavior, children with poor family system performance are often lower than normal families in problem solving, communication and behavior control (Wang et al., 2009). Furthermore, children imperceptively mimic the romantic relationships of their family of origin, thus influencing their own role perceptions and relationship patterns (Rollins et al., 2018). As for the factors that influence family systems, existing studies have found that, factors such as parents’ occupation (Xu & Zhao, 2018), parenting style (Li, 2019), number of family members (White et al., 2010), socioeconomic status (Zeng et al., 2017) and living environment (Yang et al., 2007) are important factors affecting the normal operation of family system. However, it is not hard to see that it is not easy to change these factors in real life. Therefore, both theoretically and practically, more realistic factors should be put forward to ensure the normal operation of the family system.

Subjective well-being

For thousands of years, “happiness” has been a widely discussed topic in philosophy and religion in both east and West (Diener et al., 2018). After the Second World War, the fields of sociology and psychology also began to pay attention to happiness, and carried out relevant studies from multidimensional dimensions such as population, emotion, mental health and cognition (Xing, 2002).

In the 1980s, Diener first proposed “subjective well-being”, which is defined as the judgment and evaluation of one’s own life and emphasizes self-perception, which can be understood from both cognitive and emotional levels (Diener et al., 2018). Among them, cognition mainly refers to the comprehensive judgment of life conditions, while emotional responses are divided into positive emotions and negative emotions. Positive emotions are short-term enjoyment or long-term optimism, while negative emotions are short-term anger, sadness or long-term depression (Diener et al., 2018). Common happiness theory models include temperament theory, goal theory, event theory, judgment theory and dynamic balance theory.

The influencing factors of subjective well-being can be interpreted from both subjective and objective aspects. Subjective influencing factors emphasize the influence of people’s internal traits on happiness, mainly including genes (Tellegen et al., 1988), personality (Mccrae & Costa, 1991; Tang & Meng 2002), self-esteem (Zhang, 2015), attachment style (Deng et al., 2015), etc. Objective influencing factors focus on the influence of external events and situations on individual happiness, mainly including economic income (Diener et al., 2010), culture (Qiu & Zheng, 2006), social environment (Jebb et al., 2018; Tay et al., 2014), social relations (Lampropoulou, 2018; Chi et al., 2019) and external events (Diener et al., 2018).

Research hypothesis

The relationship between family rituals and subjective well-being

Being regarded as an important personal activity, family ritual refers to the special activities that occur repeatedly in family life, which includes two factors, meaning (the symbolic qualities) and enactment (the routine aspects), and are conducive to stabilizing family relations and members’ sense of belonging (Fiese et al., 2002). A family ritual can be evaluated from seven dimensions, such as affect, symbolic significance, occurrence and deliberateness (Fiese, 1992). Relevant studies have shown that family meals (Ho et al., 2018), holidays (Bao et al., 2019), birthdays (Remisiewicz & Rancew-Sikora, 2020), religious holidays (Kellermann, 2013) and other family rituals in different situations can influence the perception and behavior of family members to a certain extent. A cross-cultural ethnographic study based on Japan and Germany found that repeatable and identifiable processes and scripts in family rituals can help families reduce uncertainty and sense of alienation, thus bringing happiness (Kellermann, 2013). Another study of 713 adolescent families in New Zealand found that meaningful family rituals were associated with adolescents’ subjective well-being (Crespo et al., 2011).

Compared with western countries, China has always emphasized that “family harmony is the key to prosperity”, and families may have a more significant and far-reaching impact on personal growth than other social relationships. At the same time, college students are in the transition stage from school to society, and compared with teenagers, they need to establish emotional connections with others, and family rituals provide a favorable environment for the establishment of emotional connections. Therefore, taking college students as the research object, exploring the impact of family rituals on subjective well-being may be more representative and of social significance than other stages. Therefore, this paper proposes:

H1: Family rituals have positive impacts on college students’ subjective well-being

H1a: The meaning of family rituals has positive impact on college students’ subjective well-being

H1b: The enactment of family rituals has positive impact on college students’ subjective well-being

The relationship between family rituals and family system

Family is a complex dynamic system, and the normal operation of the family system will affect the smooth development of individuals and families, while family cohesion and adaptability are the key factors affecting the normal operation of the family system (Olson, 2000).

Family cohesion is mainly used to measure the emotional bond between family members. As a powerful organizational path in the family system, family rituals promote family members to become close and have a sense of belonging by conveying emotional energy, thus forming strong family bonds and family identities, which have an important impact on the normal operation of the family system (Wolin & Bennet, 1984). Studies have found that regularly organizing family meals (Lawrence & Pliscon, 2017; Smith et al., 2020), leisure activities (Izenstark & Ebata, 2016), and celebrations (Baxter & Braithwaite, 2002) can provide an opportunity for family members to enhance communication and interaction, thus helps resolve conflicts and strengthen family ties.

Family adaptability refers to the ability of the family system to respond and adjust to changes in the external environment. Studies have found that introducing rituals into families can help families resist external pressures and maintain normal family life (Buchbinder et al., 2009). Studies on patients with cancer and chronic diseases have found that maintaining the original family rituals or developing new ones are conducive to relieving heavy mental stress and helping families maintain normal family life (Crespo et al., 2013). Studies on family members have found that the death of any family member or the arrival of a new member will have an impact on the original family life. Introducing family rituals can help members face up to the real life and guide the family through the transition smoothly (Fiese & Kline, 1993; Softing et al., 2015). Accordingly, this paper proposes:

H2: Family rituals positively affect the family system

H2a: The meaning of family rituals positively affects the cohesion of family systems

H2b: The meaning of family rituals positively influences the adaptability of family systems

H2c: The enactment of family rituals has positive impact on the cohesion of family systems

H2d: The enactment of family rituals has positive impact on the adaptability of family systems

The relationship between family system and subjective well-being

Family plays a central role in the healthy growth of individuals. All the binary relationships and subsystems formed within the family system are linked together in important ways at each stage of life, and have a profound impact on individuals’ access to happiness and tangible resources (Umberson et al., 2010). A large number of studies have found that the operation of the family system can predict the happiness level to a certain extent, that is, the closer the family is, the more harmonious the relationship between members is, the more the individual can feel the support from family members, and thus can obtain more positive emotional experience in life. Families with higher adaptability tend to adopt more positive coping styles when facing external pressure, and have enough psychological capital to adapt to environmental changes. Individuals are less affected by external pressure events, so they can obtain higher happiness. This conclusion has been verified in relevant studies of adolescents (Stuart & Jose, 2017), women (Wu & Zheng, 2020) and the elderly (Ryan & Willits, 2016). Based on this, this paper proposes:

H3: Family system has positive impact on college students’ subjective well-being

H3a: The cohesion of family system has positive impact on college students’ subjective well-being

H3b: The adaptability of family system has positive impact on college students’ subjective well-being

The mediating role of family system between family ritual and subjective well-being of college students

Family is a dynamic system built by blood relationship and emotional relationship. As an important interaction ritual, family ritual influences the steady operation of the family system by conveying emotional commitment in the family context, thus influencing family health, personal subjective well-being and quality of life (Ho et al., 2018). In the process of development, both individuals and families will inevitably experience some unexpected situations. The introduction of family rituals can help families adjust the pace of life and change the way family members view things, thus improving the adaptability of the family system. At the same time, family members can be encouraged to face the changes in the external environment with a more positive attitude, thus reducing the impact and emotional pressure brought to individuals by accidents. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: Family system plays a mediating role in the relationship between family rituals and subjective well-being of college students

H4a: The cohesion of family system plays a mediating role in the relationship between the meaning of family rituals and college students’ subjective well-being

H4b: The adaptability of family system plays a mediating role in the relationship between the meaning of family rituals and college students’ subjective well-being

H4c: The cohesion of family system plays a mediating role in the enactment of family rituals and college students’ subjective well-being

H4d: The adaptability of family system plays a mediating role between the enactment of family rituals and college students’ subjective well-being

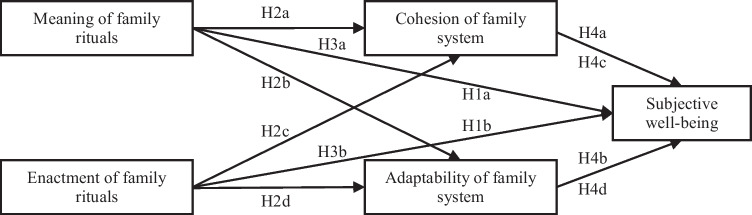

In order to answer the four specific questions raised in the background section, based on the above hypotheses, we propose the following model for the relationship between family rituals, family systems and subjective well-being:

Methodology

Research design

As can be seen from Fig. 1, this paper establishes an intermediary model in which family ritual is the independent variable, subjective well-being of college students is the dependent variable, and family system is the intermediary and four basic hypotheses are proposed. Specifically, the widely recognized scales of Family Ritual Questionnaire (FRQ), the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES III) revised by Xu et al. (2008) and the Well-being Index Scale (WBIS) revised by Chinese scholars Yao et al. (1995) are used to measure the variables in the model, but some certain questions are modified after the pre-test to get the final questionnaire which will be distributed to college students. Then, based on the data obtained from the questionnaire survey, statistical analysis will be conducted to verify whether the hypothesis is valid.

Fig. 1.

The research hypotheses of this paper

College students are selected as research samples, mainly for the following three reasons: First, suicides among college students due to mental health problems are common in China, so it is necessary and urgent to pay attention to their original families and personal happiness; Second, most of the previous studies on family rituals are based on children, adolescents, special groups or families with sick people, and Chinese college students are taken as the research object to expand the research sample, which is conducive to subsequent comparative studies. Third, compared with middle and high school students or social people, college students have a higher degree of cooperation and accuracy in issuing and filling questionnaires.

Questionnaire design and variable measurement

The questionnaire mainly includes four parts: family ritual, family system, subjective well-being and demographic information. Relatively mature scales or questionnaires were selected for this study. Among them, the FACES III and the WBIS have been translated into Chinese and verified by Chinese scholars for many times. The family ritual questionnaire was introduced for the first time and translated into English by back translation. In order to ensure the accuracy of the data, the author designed the questionnaire in terms of structure and layout, and deleted the items with CITC value lower than 0.3 in the pre-test, and finally determined the formal questionnaire.

Measurement of family rituals: The Family Ritual Questionnaire(FRQ) developed by Fiese (1992) evaluated the four settings of dinner time, weekends, vacations and annual celebrations from seven dimensions of occurrence, roles, routine, attendance, affect, symbolic significance and deliberateness, with a total of 28 questions. After the pre-test deleted 3 questions that failed the test, the formal questionnaire had a total of 25 questions.

Measurement of family system: Olson developed Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale (FACES) based on the circumpolar model theory, which can better adapt to Chinese culture and national conditions and can be directly applied to compare Chinese and Western populations (Li et al., 2012). This paper uses FACES III revised by Xu et al. (2008). The scale contains 20 items, 10 items for cohesion and adaptability respectively, and is scored by 5 points. The higher the score is, the higher the family cohesion and adaptability are.

Measurement of subjective well-being: It refers to an individual’s cognitive and emotional evaluation of self and lifestyle. In this paper, the Well-being Index Scale (WBIS) developed by Campbell (1976) was used to test the degree of happiness experienced by the subjects, including the overall emotional index and life satisfaction. It was scored with 7 points and had 9 questions in total. Chinese scholars Yao et al. (1995) revised the scale and verified that it had good reliability and validity.

Questionnaire pre-test

In the pre-survey stage, the questionnaire was distributed to college students by Sojump, a popular online questionnaire collecting platform in China. A total of 160 questionnaires were distributed, and 90 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective rate of 56.25%, excluding the answers that did not pass the polygraph test and whose answer time was less than 180 s. The reliability and validity of the pre-survey data were tested by SPSS25.0 and the results showed that the questionnaire passed the reliability and validity tests and was suitable for exploratory factor analysis. Based on the analysis of the pre-test questionnaire data, it was found that except for three items about family rituals failed the test and were deleted, the three mature scales all passed the reliability and validity tests, and the pre-test results were satisfactory.

Data collection and analysis results

Sampling and data collection

Due to the epidemic, many colleges and universities in China especially in Shanghai implemented closed management during the study period, and researchers could not enter the campus to issue paper questionnaires. Therefore, Sojump was used to collect the samples by means of snowballing. For Snowball sampling, the specific operation is as follows: firstly, some college students are randomly selected as the respondents, and then they are asked to forward the link of the questionnaire to their classmates or friends in other universities. Finally, a total of 700 questionnaires were sent and 700 were collected, with a return rate of 100%. Among them, 424 effective questionnaires were collected with an effective rate of 60.6%. There were 258 females, accounting for 60.8%, and 166 males, accounting for 39.2%. There are 188 rural residents, accounting for 44.3%, and 236 urban residents, accounting for 55.7%; The number of only children was 239, or 56.4%, while the number of non-only children was 185, accounting for 43.6%.

Descriptive statistical analysis

The demographic analysis included gender, place of residence and only child status. In terms of gender, there were 258 females, accounting for 60.8%, and 166 males, accounting for 39.2%; In terms of place of residence, 188 people were registered in rural areas, accounting for 44.3%, and there are 236 urban residents, accounting for 55.7%; In terms of whether they are only children or not, the number of only children is 239, accounting for 56.4%, and the number of non-only children was 185, accounting for 43.6%. Furthermore, the researchers used mean value, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis to test whether the variable data were in line with normal distribution.

The results showed that the skewness and kurtosis of each item meet the condition of normal distribution, which indicates that the data collected in this study can be directly used for statistical analysis.

Reliability test

FRQ evidences good psychometric properties. In the research of Fiese (1992), test-retest reliability is reported to be 0.88. For a discussion of the development and psychometric properties of the FRQ, we can refer to the study of Fiese and Kline (1993). In this paper, SPSS was used as an analysis tool to test the reliability of the data, and Cronbach’α coefficient was used as an indicator to test the consistency and stability of the measurement items.

The results showed that the Cronbach’α coefficients of 7 dimensions of family rituals were 0.803, 0.879, 0.839, 0.809, 0.848, 0.836, 0.854, respectively. The Cronbach’α coefficients of family system cohesion and adaptability were 0.919 and 0.916, respectively. The Cronbach’α coefficient of SWB was 0.922, indicating high reliability of data and high internal consistency of the scale (Table 1). But it should be noted that since the life satisfaction questionnaire has only one item, it is not suitable for validity analysis. Therefore, the reliability and validity measurement of subjective well-being is carried out only for the overall emotional index.

Table 1.

The results of reliability test

| Measured variable | Dimension | Item | Cronbach’α coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family rituals | Occurrence | WK1-AC1 | 0.803 |

| Roles | DT2-AC2 | 0.879 | |

| Routine | WK3-AC3 | 0.839 | |

| Attendance | WK4-AC4 | 0.809 | |

| Affect | DT5-AC5 | 0.848 | |

| Symbolic significance | DT6-AC6 | 0.836 | |

| Deliberateness | DT7-AC7 | 0.854 | |

| Family system | Cohesion | CL1-CL10 | 0.919 |

| Adaptability | AD1-AD10 | 0.916 | |

| Subjective well-being | Overall affect index | LF1-LF8 | 0.922 |

Validity test

As this paper adopts a mature scale in related fields and sets a lie detection test in the questionnaire, the content validity of the scale basically meets the requirements. Factor analysis is mainly used to test the construct validity and the larger the factor load value is, the better the convergence validity is. Factor analysis includes confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory factor analysis (EFA), among which the latter is often used for classical scales.

AMOS 24.0 was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis on family rituals. As mentioned above, family rituals can be summarized as two factors, meaning (the symbolic qualities) and enactment (the routine aspects), including 7 dimensions, which are affect, symbolic significance, occurrence, attendance, and deliberateness, roles and routine (Fiese, 1992). Therefore, this paper adopts second-order verification analysis to verify the scale validity. The results in Table 2 showed that each index presents a significance level of 0.001, and the load coefficients of standardized factors are all greater than 0.5, indicating that there is a good correspondence between factors and measurement items. Meanwhile, the AVE values of symbolic meaning and enactment were both higher than 0.5 and CR values were both higher than 0.7, indicating that the scale had good aggregation validity.

Table 2.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis of family rituals

| Measured variable | Dimension | Nonstandardized factor loading | Standard error | Z value | P value | Standardized factor loading | SMC | Convergent validity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | ||||||||

| Meaning | Occurrence | 1 | 0.755 | 0.570 | 0.823 | 0.539 | |||

| Affect | 0.795 | 0.09 | 8.826 | *** | 0.741 | 0.549 | |||

| Symbolic meaning | 0.751 | 0.094 | 8.006 | *** | 0.682 | 0.465 | |||

| Deliberateness | 0.932 | 0.102 | 9.106 | *** | 0.755 | 0.570 | |||

| Enactment | Roles | 1 | 0.637 | 0.406 | 0.779 | 0.543 | |||

| Routine | 1.306 | 0.173 | 7.542 | *** | 0.844 | 0.712 | |||

| Attendance | 1.286 | 0.165 | 7.817 | *** | 0.715 | 0.511 | |||

The results of confirmatory factor analysis of family system and subjective well-being are shown in Table 3. All the measurement items present a significance level of 0.001, and the load coefficients of standardized factors are all higher than 0.5. Therefore, there is a good correspondence between the factors and the measurement items. At the same time, AVE values of family cohesion and adaptability scale and CR values of overall affect index scale were both higher than 0.5 and 0.7, indicating that each scale had good aggregation validity.

Table 3.

The results of confirmatory factor analysis of family system

| Dimension | Item | Nonstandardized factor loading | Standard error | Z value | P value | Standardized factor loading | SMC | Convergent validity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | AVE | ||||||||

| Cohesion | CL1 | 1.000 | 0.807 | 0.651 | 0.924 | 0.548 | |||

| CL2 | 0.734 | 0.047 | 15.485 | *** | 0.694 | 0.482 | |||

| CL3 | 1.230 | 0.075 | 16.454 | *** | 0.728 | 0.530 | |||

| CL4 | 1.105 | 0.068 | 16.158 | *** | 0.718 | 0.516 | |||

| CL5 | 1.178 | 0.070 | 16.810 | *** | 0.740 | 0.548 | |||

| CL6 | 0.853 | 0.057 | 14.921 | *** | 0.674 | 0.454 | |||

| CL7 | 1.024 | 0.064 | 16.092 | *** | 0.715 | 0.511 | |||

| CL8 | 0.894 | 0.056 | 15.867 | *** | 0.708 | 0.501 | |||

| CL9 | 1.119 | 0.063 | 17.708 | *** | 0.770 | 0.593 | |||

| CL10 | 0.916 | 0.046 | 19.792 | *** | 0.835 | 0.697 | |||

| Adaptability | AD1 | 1.000 | 0.792 | 0.627 | 0.919 | 0.534 | |||

| AD2 | 0.990 | 0.070 | 14.209 | *** | 0.658 | 0.433 | |||

| AD3 | 1.309 | 0.077 | 17.075 | *** | 0.764 | 0.584 | |||

| AD4 | 0.881 | 0.060 | 14.605 | *** | 0.673 | 0.453 | |||

| AD5 | 1.311 | 0.081 | 16.254 | *** | 0.735 | 0.540 | |||

| AD6 | 0.927 | 0.057 | 16.125 | *** | 0.730 | 0.533 | |||

| AD7 | 0.933 | 0.063 | 14.824 | *** | 0.682 | 0.465 | |||

| AD8 | 1.178 | 0.074 | 15.926 | *** | 0.723 | 0.523 | |||

| AD9 | 1.534 | 0.085 | 17.950 | *** | 0.795 | 0.632 | |||

| AD10 | 1.247 | 0.076 | 16.331 | *** | 0.738 | 0.545 | |||

| Overall Affect Index | LF1 | 1.000 | 0.794 | 0.630 | 0.924 | 0.604 | |||

| LF2 | 1.041 | 0.063 | 16.551 | *** | 0.738 | 0.545 | |||

| LF3 | 1.056 | 0.065 | 16.264 | *** | 0.732 | 0.536 | |||

| LF4 | 1.046 | 0.071 | 14.692 | *** | 0.673 | 0.453 | |||

| LF5 | 1.298 | 0.064 | 20.264 | *** | 0.867 | 0.752 | |||

| LF6 | 1.301 | 0.066 | 19.84 | *** | 0.852 | 0.726 | |||

| LF7 | 1.187 | 0.067 | 17.608 | *** | 0.776 | 0.602 | |||

| LF8 | 1.06 | 0.061 | 17.388 | *** | 0.769 | 0.591 | |||

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is mainly used to prove that indicators that do not have correlation do not have correlation with this construct. The commonly used measurement method is to compare the correlation coefficient between the AVE square root and the factor. If the AVE square root is higher than the correlation coefficient between the factor and other factors, it indicates that the questionnaire has good discriminative validity.

This paper analyzes family rituals, family system and subjective well-being in pairs, with a total of 5 variables. The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the five variables of meaning of family rituals, enactment of family rituals, cohesion of family system, adaptability of family system and subjective well-being at the level of 0.01. For example, the AVE square root value of the symbolic meaning of family rituals is 0.734, which is higher than the correlation coefficient with the other four factors. Therefore, the discriminant validity of questionnaire data in this study is good (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pearson correlation and AVE root value

| Meaning of family rituals | Enactment of family rituals | Cohesion | Adaptability | Subjective well-being | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning of family rituals | 0.734 | ||||

| Enactment of family rituals | 0.286** | 0.737 | |||

| Cohesion | 0.375** | 0.197** | 0.741 | ||

| Adaptability | 0.220** | 0.428** | 0.307** | 0.730 | |

| Subjective well-being | 0.359** | 0.305** | 0.565** | 0.337** | 0.777 |

The figures on the diagonal of the table are √AVE, and the figures on the non-diagonal lines are the correlation coefficients between dimensions. **. at the level of 0.01 indicates significant correlation

Regression analysis

A phenomenon is often associated with multiple factors, when it is necessary to predict the dependent variable by the optimal combination of multiple independent variables, it is suitable to use multiple linear regression analysis. In order to further understand the prediction and influence mechanism of family ritual and family system on subjective well-being, it is necessary to take the symbolic meaning and enactment of family rituals, and the intimacy and adaptability of family system as independent variables, and subjective well-being as dependent variable to carry out linear regression on the above variables. Linear regression can also be used to analyze the influence of family rituals on family system.

As shown in Table 5, Model 1 took subjective well-being as the dependent variable, and meaning and enactment of family rituals as the independent variables, and conducted linear regression among the three. It was found that the symbolic meaning and enactment of family rituals had significant predictive effects on subjective well-being, which could explain 17.4% variation of subjective well-being and verified hypothesis 1. Model 2 took subjective well-being as the dependent variable and family system cohesion and adaptability as the independent variables, and carried out linear regression among the three. It was found that cohesion and adaptability of family system had significant predictive effects on subjective well-being, which could explain 34.8% of the variation of subjective well-being and verified hypothesis 3.

Table 5.

Regression analysis result of family rituals and subjective well-being

| Model | Dependent variable | Variables | R² | F | β | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Subjective well-being | Meaning | 0.174 | 44.200 | 1.431 | 0.000 |

| Enactment | 0.897 | 0.000 | ||||

| Model 2 | Subjective well-being | Cohesion | 0.348 | 112.569 | 1.757 | 0.000 |

| Adaptability | 0.644 | 0.000 | ||||

| Model 3 | Cohesion | Meaning | 0.149 | 36.392 | 0.486 | 0.000 |

| Enactment | 0.115 | 0.038 | ||||

| Model 4 | Adaptability | Meaning | 0.194 | 50.506 | 0.144 | 0.020 |

| Enactment | 0.454 | 0.000 | ||||

| Model 5 | Subjective well-being | Meaning | 0.381 | 64.528 | 0.606 | 0.003 |

| Enactment | 0.532 | 0.003 | ||||

| Cohesion | 1.578 | 0.000 | ||||

| Adaptability | 0.404 | 0.010 |

In Model 3, the cohesion of family system was taken as the dependent variable, and meaning and enactment of family rituals were taken as independent variables. The results of linear regression showed that the symbolic meaning and enactment of family rituals had significant predictive effects on the cohesion of family system, which could explain 14.9% of the variation of cohesion. In Model 4, the adaptability was taken as the dependent variable, and the meaning and enactment of family rituals were taken as the independent variables. The results of the linear regression showed that the meaning and enactment of family rituals also had significant predictive effects on the adaptability of family system, which could explain 19.4% of the variation of adaptability and verified hypothesis 2.

Mediating effects of family system

In Table 5, Model 1 verifies the validity of hypothesis 1, indicating that the overall effect of family rituals on subjective well-being is significant. Model 2 verifies hypothesis 3, and Model 3 and Model 4 verify hypothesis 2, indicating that family system plays a mediating role in the relationship between family rituals and subjective well-being, and hypothesis 4 is verified. From the regression results of Model 5, it can be seen that family rituals have significant direct effects on subjective well-being, and family system plays a partial intermediary role between family rituals and subjective well-being.

In order to further test the mediating effect of family system, this paper adopts the Bootstrap method recommended by Fang et al. (2012) and Model 4 in The SPSS PROCESS compiled by Hayes (2013) is used. The symbolic meaning and the enactment of family rituals were taken as independent variables, subjective well-being as dependent variable, and cohesion and adaptability of family system as mediating variables to test the mediating effect. Bootstrap samples with a sample size of 5000 were set with an interval confidence of 95%, and the following conclusions were obtained:

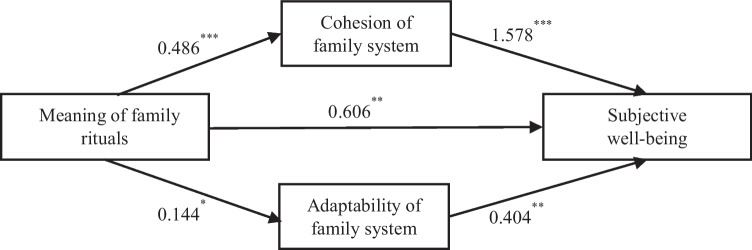

The effect of symbolic meaning of family rituals on subjective well-being: the mediating effects of cohesion and adaptability

Through the analysis of the mediating effect of the cohesion and adaptability of family system in the process of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being, the results show that the indirect effect of cohesion on the symbolic meaning of family rituals and subjective well-being is 0.159, and its Bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that the cohesion has a significant mediating effect between the symbolic meaning of family rituals and subjective well-being. The indirect effect of adaptability between the symbolic meaning of family rituals and subjective well-being is 0.012, and the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that the adaptability also has a significant mediating effect in the process of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being. In addition, the difference between the mediating effect of cohesion and adaptability is 0.147, and its Bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that in the process of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being, the effect of cohesion is significantly greater than that of adaptability (Table 6; Fig. 2).

Table 6.

The mediating effect of family system in the process of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being

| Effect type | Effect value | Boot SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | Relative mediating effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | Lower limit | ||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.171 | 0.030 | 0.117 | 0.233 | 57.655% |

| Cohesion | 0.159 | 0.028 | 0.109 | 0.219 | 53.565% |

| Adaptability | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 4.089% |

| Cohesion-Adaptability | 0.147 | 0.029 | 0.095 | 0.207 | 49.510% |

Fig. 2.

The path diagram of the mediating effect of family system in the process of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being

-

(2)

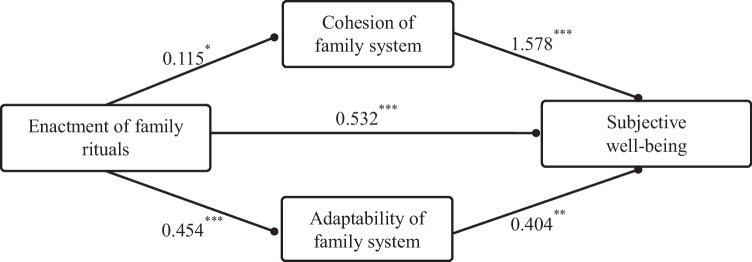

The effect of enactment of family rituals on subjective well-being: the mediating effects of cohesion and adaptability

Accordingly, through the analysis of the mediating effect of the cohesion and adaptability of family system in the process of the enactment of family rituals influencing subjective well-being, the results show that the indirect effect of cohesion on the enactment of family rituals and subjective well-being is 0.045, and its Bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that the cohesion has a significant mediating effect between the enactment of family rituals and subjective well-being. The indirect effect of adaptability between the enactment of family rituals and subjective well-being is 0.045, and the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval does not include 0, indicating that the adaptability also has a significant mediating effect in the process of the enactment of family rituals influencing subjective well-being. In addition, the difference between the mediating effect of cohesion and adaptability is 0.033, and the Bootstrap 95% confidence interval includes 0, indicating that in the process of the enactment of family rituals influencing subjective well-being, there is no significant difference between the partial mediating effects of cohesion and adaptability (Table 7; Fig. 3).

Table 7.

The mediating effect of family system in the enactment of the symbolic meaning of family rituals influencing subjective well-being

| Effect type | Effect value | Boot SE | Bootstrap 95%CI | Relative mediating effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | Lower limit | ||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.090 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.146 | 40.707% |

| Cohesion | 0.045 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.089 | 20.263% |

| Adaptability | 0.045 | 0.021 | 0.005 | 0.089 | 20.399% |

| Cohesion-Adaptability | 0.000 | 0.033 | -0.063 | 0.065 | -0.453% |

Fig. 3.

The path diagram of the mediating effect of family system in the process of the enactment of family rituals influencing subjective well-being

Discussions and implications

Discussions

By reviewing Chinese and western literature, this paper combined systematic theories in the field of family therapy with ritual events, focused on the social topic of college students’ mental health, and tried to explain the mechanism of family rituals on college students’ subjective well-being, and put forward effective suggestions for improving college students’ subjective well-being.

Theoretically, existing studies on family rituals mainly focus on the impact of family rituals on patients’ families. Although many studies have focused on the impact on individual subjective well-being, the mechanism still needs to be further clarified. By introducing family system theory and interaction ritual chains theory, this paper proved that family rituals have an impact on subjective well-being through affecting the intimacy and adaptability of family system, which enriches the theoretical research on family rituals from the perspective of family nursing and psychology. The verification results of hypothesis 2 are consistent with the viewpoints proposed by some scholars such as Crespo et al. (2011), Santos (2017), Hecker and Schindler (1994), that family rituals can stabilize family relations, enhance the intimacy between members, and improve the overall resilience of the family in the face of changes in the external environment. To some extent, this empirical conclusion is also a proof of Collins’ interaction ritual chains theory. According to the theory, rituals can lead participants to form a common concern. Through shared actions and consciousness, emotional energy of individuals will be stimulated, collective excitement and sense of membership will be generated, thus forming closer group unity (Collins, 2004, pp.49).

From the perspective of practice, in recent years, the emergence of depression among Chinese college students has raised the demand for psychological treatment, but the existing intervention methods in China still focus on interview and drug therapy. This paper introduces the research results of foreign family therapy, demonstrates the influence of family rituals on subjective well-being, and broadens a new intervention path for college students’ mental health treatment. At the same time, this study also provides effective suggestions for family parenting, encouraging families to develop meaningful family rituals with emotion as the core, to build intimate and flexible parent-child relationship, so that children can feel the love of the world, and thus have healthy and positive psychological capital to face the challenges in the growth process.

In addition, according to the theory of psycho-social development, family has an important influence on the formation of sound personality. Individuals with closer family relationships tend to be more willing to trust others, have stronger resistance to frustration, and feel more satisfied with their lives. The verification results of hypothesis 2 supports the opinion of Hu et al. (2011), Xu and Zhao (2018) and others, that the more harmonious the relationship between family members is, the more emotional connection and belonging they feel in life, and the more subjective well-being individuals can achieve. At the same time, in the face of external environment changes, individuals with better family system operation tend to have more positive psychological capital to face the adjustment of family system and external challenges.

Therefore, we need to develop meaningful family rituals to enhance the intimacy of the family system. This study takes family as the core and introduces family system theory to explain the mechanism of family rituals, which provides a new thinking for “what is family”. The family is a system, and any problems should not be blamed on individuals, but reflect on the role of each family member in it. A good family system is never the result of one person’s efforts. It needs the hard work of every family member. Accordingly, it is necessary to propose that a good family system can be constructed by changing the way family members view the family, so as to prevent the generation of psychological problems.

Theoretical implications

This paper tentatively applies the theories of psychology and family nursing to the study of family rituals, and explores the relationship between family ritual, family system and subjective well-being. The theoretical enlightenment is as follows:

Supplementing mediating factors from the perspective of system theory is helpful to clarify the influence mechanism of family ritual on subjective well-being. Most of the existing researches on family rituals is based on individual or binary relationship to discuss its influence. Based on the system theory, this paper discusses the influence mechanism of family rituals from the perspective of family system, and finds that family rituals can not only directly affect subjective well-being, but also affect individual subjective well-being through family system, which improves the original function system of family rituals;

It is of practical significance to expand the research on influencing factors of family system and subjective well-being. According to the findings of existing studies, the influencing factors of family system mainly include social and economic status, family upbringing style, living environment, etc., while the influencing factors of subjective well-being mainly focus on personal characteristics and external accidents. On this basis, this paper broadens the research perspective, taking family as the context, proposes and verifies the influence of family rituals on family system and subjective well-being, demonstrates the important role of special events in family life and personal growth, and enriches the theoretical research on family system and subjective well-being;

It is necessary to further enrich the research samples and cultural context of family rituals. Cultural differences and age differences will have an impact on the research results, while most of the existing studies on family rituals focus on caucasians and teenagers. This paper takes Chinese college students as the research object, which enriches the research sample and provides strong support for comparative research.

Practical implications

According to the test results of hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2, the symbolic meaning and the enactment of family rituals have important impact on the normal operation of family system and subjective well-being of college students. Today, with the increasing tendency of depression among college students in China, we need to introduce family rituals with emotional energy as the “strong glue” to solidify family relationship and the “important tool” to transfer family concept, so as to maintain good family relationship and cultivate positive psychological capital of college students. In addition, family rituals can take various forms, such as intimate nicknames between members, chatting at dinner, weekend parties, birthday celebrations and so on.

According to the test results of hypothesis 3, the cohesion and adaptability of the family system have an important impact on college students’ subjective well-being. Therefore, people must change their traditional cognition of family and treat family as a complete system. In China, the traditional belief that “men should take care of the outside and women should take care of the inside” tends to place more responsibilities on women, meaning that more problems children encounter in growing up will be attributed to the mother. However, when problems occur in family relations or individuals, each family member should reflect on his or her own behavior and attitude, communicate on an equal footing, so as to understand each other’s behavioral intentions and emotional feelings, and promote the circular interaction between various parts of the family system and levels.

The test results of hypothesis 4 proves that meaningful family rituals can indirectly affect the subjective well-being of college students through the family system. Therefore, there is a need to recognize the influence of cohesion and adaptability of family system on individual perceptions and the important role that family rituals can play in them. First, both parents and children should devote as much time as possible to their family members. Secondly, family members should consciously convey family concepts through daily interactions, birthday surprises, festival celebrations and other family rituals, so as to cultivate a sense of belonging and role. In addition, adaptive role relationships and family leadership should be developed in the family. When the external environment changes, the original family rituals or new rituals can be used to stabilize the pace of family life, thus relieving the pressure and anxiety brought by role changes.

Conclusion and future study

Conclusion

Taking the family system as an meditating variable, this paper explores the influence of family rituals on college students’ subjective well-being, and the research results are as follows:

The symbolic meaning and enactment of family rituals can significantly predict the cohesion and adaptability of family system, that is, the more symbolic and procedural the family ritual is, the more intimate and adaptable the family system will be, which is consistent with hypothesis 2.

The symbolic meaning and enactment of family rituals can significantly predict the subjective well-being of college students, which is consistent with hypothesis 1. Meaningful family rituals are closely related to happiness of family members, and across different stages of individual and family development, the factors such as roles identity, emotional commitment and symbolic meaning conveyed by family rituals will affect individuals’ perceived happiness.

This paper finds that the cohesion and adaptability of family system can significantly predict the subjective well-being of college students, that is, the subjective well-being of college students will fluctuate up and down due to the operation of family system, which is consistent with hypothesis 3.

This study found that family system plays a mediating role between family rituals and college students’ subjective well-being, which is consistent with the result of hypothesis 4. Family rituals can have an impact on subjective well-being by enhancing the cohesion of the family system.

To sum up, family rituals can enhance individual subjective well-being by improving the resilience of the family system to the external environment, which echoes the research conclusions of Santos et al. (2012) and Ferranti (2016). Family members gathering together to hold meaningful family rituals can provide themselves with a sense of security and intimacy. When family life is disrupted, one way to maintain normal life is to stick to the old family rituals or create new family rituals, since family rituals can enhance the adaptability of the family system and the individual’s sense of competence, which enables family members to have more positive psychological capital to face external challenges, thus improving the individual’s evaluation of life (Hanke et al., 2016) . These findings also echo those of Collins (2004) in the theory of interaction ritual chains.

Limitations and future study

There are still some shortcomings in this paper: (1) due to the impact of COVID-19, online survey has affected the overall quantity and reliability of data to a certain extent; (2) As it is the first time for the family ritual questionnaire to be introduced and translated into Chinese, the connotation expression and diction need to be further optimized; (3) This article only focuses on the influence of family ritual characteristics on family system and subjective well-being, and there is no special discussion on whether the type of family ritual has an impact.

In the future, it is necessary to broaden the scope of research groups and try to carry out comparative studies on different groups. At the same time, the influence of specific dimensions on subjective well-being in different ritual activities can be discussed in combination with the types of family rituals. In addition, this paper takes family system as the mediating variable to carry out relevant research, but whether there are other factors playing a role in the influencing process is also worth paying attention to in the future research.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest in this research and all participants knew that the information they provided was for the overall analysis only and may be used for publication in a journal.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuchen Yang, Email: yangyuchen@suibe.edu.cn.

Chunlei Wang, Email: wangcl@suibe.edu.cn.

References

- Bai, H., & Ma, X. (2019). The incidence of depression among college students in China is increasing year by year: Higher in freshmen and juniors. China Youth Daily.

- Bao J, Gudmunson CG, Greder K. The impact of family rituals and maternal depressive symptoms on child externalizing behaviors: An urban-rural comparison. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2019;48(6):935–953. doi: 10.1007/s10566-019-09512-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LA, Braithwaite DO. Performing marriage: Marriage renewal rituals as cultural performance. Southern Communication Journal: Communication and Committed Couples. 2002;67(2):94–109. doi: 10.1080/10417940209373223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bossard JHS, Boll ES. Ritual in family living. American Sociological Review. 1949;14(4):463–469. doi: 10.2307/2087208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder M, Longhofer J, Mccue K. Family routines and rituals when a parent has cancer families. Systems & Health. 2009;27(3):213–227. doi: 10.1037/a0017005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. Subjective measures of well-being. American Psychologist. 1976;31(2):117–124. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.31.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi P, et al. Well-being contagion in the family: Transmission of happiness and distress between parents and children[J] Child Indicators Research. 2019;12(6):2189–2202. doi: 10.1007/s12187-019-09636-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. Interaction ritual chains. Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Families as systems. Psychology. 1997;1(48):243–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. Understanding families as systems. Current Directions In Psychological Science. 2003;12(5):193–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo C, Kielpikoski M, Pryor J, Jose PE. Family rituals in New Zealand families: Links to family cohesion and adolescents’ well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(2):184–193. doi: 10.1037/a0023113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo C, Santons S, Canavarro MC. Family routines and rituals in the context of chronic conditions: a review. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International De Psychologie. 2013;48(5):729–746. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2013.806811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Ma B, Wu Y. Attachment and subjective well-being of middle school students: The mediating role of self-esteem. Psychological Development and Education. 2015;2:230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Depression Research Institute (2019). Blue Book on Depression in China. http://www.medsci.cn/article/show_article.do?id=1db71861e8f6, 2020-1-1

- Diener E, Chan MY. Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3(1):1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Kahneman D, Tov W. International differences in well-being. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(4):253–260. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Zhang M, Qiu H. The mediating effect and its measurement: Review and prospect. Psychological Development and Education. 2012;1:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ferranti, D. (2016). Family functioning, parenting strategies, and disordered eating among Hispanic youth. Doctoral dissertation, University of Miami, Miami.

- Fiese BH. Dimensions of family rituals across two generations: Relation to adolescent identity. Family Process. 1992;31(2):151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1992.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Kline CA. Development of the family ritual questionnaire: Initial reliability and validation studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;6(3):290–299. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.6.3.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese, B. H., Foley, K. P., & Spagnola, M. (2006). Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: contexts for child well-being and family identity. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2006(111), 67–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fiese BH, Kline CA. Development of the family ritual questionnaire: Initial reliability and validation studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;6(3):290–299. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.6.3.290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(4):381–390. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspon P, Saklofske H. Toward an integration of subjective well-being and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research. 2001;51(1):81–108. doi: 10.1023/A:1007219227883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke K, Van Egmond MC, Crespo C. Blessing or burden? The role of appraisal for family rituals and flourishing among LGBT adults. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016;30(5):562–568. doi: 10.1037/fam0000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker LL, Schindler M. The use of rituals in family therapy. Journal of family psychotherapy. 1994;5(3):1–24. doi: 10.1300/j085V05N03_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HCY, Mui M, Wan A. Family meal practices and well-being in Hong Kong: The mediating effect of family communication. Journal of Family Issues. 2018;39(16):3835–3856. doi: 10.1177/0192513X18800787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Homer MM, Freeman PA, Zabriskie RB, Eggett DL. Rituals and relationships: Examining the relationship between family of origin rituals and young adult attachment. Marriage & Family Review. 2007;42(1):5–28. doi: 10.1300/J002v42n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Ma Y, Gong S. The relationship between subjective well-being and family function of left-behind Middle school students. Public Health in China. 2011;6:686–688. [Google Scholar]

- Izenstark D, Ebata AT. Theorizing family-based nature activities and family functioning: The integration of attention restoration theory with a family routines and rituals perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2016;8(2):137–153. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jebb AT, Tay L, Diener E. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(1):33–38. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B. E., & Ray, W. A. (2016) Family systems theory. Wiley Online Library. 10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs130

- Kellermann I. Can happiness be created in rituals? An ethnographic perspective on the staging of happiness in the family in Germany and in Japan. Paragrana. 2013;22(1):28–48. doi: 10.1524/para.2013.0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr ME, Bowen M. Family evaluation: an approach based on Bowen Theory. W.W. Norton & Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kiser LJ, Bennent L, Heston J, Paavola M. Family ritual and routine: Comparison of clinical and non-clinical families. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14(3):357–372. doi: 10.1007/s10826-005-6848-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulou A. Personality, school, and family: What is their role in adolescents’ subjective well-being. Journal of Adolescence. 2018;67:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SD, Pliscon MK. Family mealtimes and family functioning. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2017;45(4):195–205. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2017.1328991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. Suggestions on psychological intervention for college students’ depression. Educational Exploration. 2009;3:113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Li Y, Li T. Review and prospect of consumer ritual behavior research. Foreign Economics and Management. 2018;5:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. (2019). A comparative study on family dynamics and positive mental health of middle school students in urban and rural areas. Tianjin Normal University.

- Li S, Chen Y, Zhan M. Theory, evaluation and application of family dynamics. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2012;4:262–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X., Zheng, Z., & Yao, Y. (2011) Family dynamics of adolescents with anxiety disorder. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 2011(5), 356–360.

- Malaquias S, Crespo C, Francisco R. How do adolescents benefit from family rituals? Links to social connectedness, depression and anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(10):3009–3017. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0104-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mccrae RR, Costa PT. Adding liebe und arbeit: The full five-factor model and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1991;17(2):227–232. doi: 10.1177/014616729101700217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Ryan CE, Keither GI. The McMaster approach to families: Theory, assessment, treatment and research. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22(2):168–189. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development. 1985;56(2):289–302. doi: 10.2307/1129720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH. Circumplex model VII: Validation studies and FACES III. Family Process. 1986;25(3):337–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: An update. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22:144–167. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.00144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L, Zheng X. Cross-cultural research on the relationship between individual cultural orientation and subjective well-being. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;3:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Remisiewicz L, Rancew-Sikora D. A candle to blow out: An analysis of first birthday family celebrations. Journal of Pragmatics. 2020;158:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2019.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D. The working family: A researcher’s view of health in the household. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1982;139(11):1412–1420. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.11.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivett M, Street E. Family therapy: 100 key points and techniques. Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins P, Williams A, Sims P. Family dynamics: Family-of-origin cohesion during adolescence and adult romantic relationships. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2018;40(2):128–137. doi: 10.1007/s10591-017-9430-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AK, Willits FK. Family ties, physical health, and psychological well-being. Journal of Aging and Health. 2016;19(6):907–920. doi: 10.1177/0898264307308340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S, Crespo C, Canavarro MC. Parents’ romantic attachment predicts family ritual meaning and family cohesion among parents and their children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2017;42(1):114–124. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S, Crespo C, Silva N. Quality of life and adjustment in youths with Asthma: The contributions of family rituals and the family environment. Family Process. 2012;51(4):557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 2006;61(8):774–788. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Ramey E, Sisson SB, et al. The family meal model: Influences on family mealtime participation. OTJR: Occupation Participation and Health. 2020;40(2):138–146. doi: 10.1177/1539449219876878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Softing GH, Dyregrov A, Dyregrov K. Because I’m also part of the family. Children’s participation in rituals after the loss of a parent or sibling. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying. 2015;73(2):141–158. doi: 10.1177/0030222815575898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J, Jose PE. The influence of discrepancies between adolescent and parent ratings of family dynamics on the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2017;26(6):858–868. doi: 10.1037/a0030056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Meng X. A comparative study of subjective well-being between middle and high school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;4:316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Tay L, Herian MN, Diener E. Detrimental effects of corruption and subjective well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2014;5(7):751–759. doi: 10.1177/1948550614528544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Lykken DT, Bouchard TJ, et al. Personality similarity in twins reared apart and together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1031–1039. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology. 2010;36(1):139–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Liu J, Wu X. Prevalence of depression in Chinese college students in recent ten years: a meta-analysis. Journal of Hainan Medical College. 2020;256(9):52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen Q, Zou H. Relationship between family function and mental health among teenager mental outpatients. Sichuan Mental Health. 2009;2:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- White MA, Elder JH, Paavilainen E. Family dynamics in the United States, Finland and Iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2010;24(1):84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SJ, Bennet LA. Family rituals. Family Process. 1984;23(3):401–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SJ, Bennet LA, Noonan DL. Disrupted family rituals: A factor in the inter-generational transmission of alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1980;41(3):199–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1980.41.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Zheng X. The effect of family adaptation and cohesion on the well-being of married women: A multiple dediation effect. The Journal of General Psychology. 2020;147(1):90–107. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2019.1635075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Z. A review of the studies on subjective well-being measurement. Psychological Science. 2002;3:336–338. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Fang X, Zhang J. The effect of family function on adolescent emotional problems. Psychological Development and Education. 2008;2:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhao X. Self-esteem and systemic family dynamics of junior middle school students. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2017;12:948–952. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhao X. Relation of well-being and systemic family dynamics of junior middle school students. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2018;12:1012–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Yao J, Huang C. Investigation of children and family dynamics character in Kunming City. China Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;3:222–223. [Google Scholar]

- Yao C, He N, Shen Q. Subjective well-being and related factors of elderly college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 1995;6:256–257. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, F. (2018). Study on the cultural compatibility of family psychotherapy in China. Chongqing Social Sciences, 2018(7), 57–64.

- Zeng W, Zhao X, Wan C. The role of family dynamics in the relationship between family socioeconomic status and children’s mental health. Health Service Management in China. 2017;10:784–787. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Analysis of influencing factors of adolescent happiness[J] Xinjiang Social Sciences. 2015;3:139–144. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.