Abstract

A stage-specific surface antigen of Theileria parva, p67, is the basis for the development of an anti-sporozoite vaccine for the control of East Coast fever (ECF) in cattle. By Pepscan analysis with a series of overlapping synthetic p67 peptides, the antigen was shown to contain five distinct linear peptide sequences recognized by sporozoite-neutralizing murine monoclonal antibodies. Three epitopes were located between amino acid positions 105 to 229 and two were located between positions 617 to 639 on p67. Bovine antibodies to a synthetic peptide containing one of these epitopes neutralized sporozoites, validating this approach for defining immune responses that are likely to contribute to immunity. Comparison of the peptide specificity of antibodies from cattle inoculated with recombinant p67 that were immune or susceptible to ECF did not reveal statistically significant differences between the two groups. In general, antipeptide antibody levels in the susceptible animals were lower than in the immune group and neither group developed high responses to all sporozoite-neutralizing epitopes. The bovine antibody response to recombinant p67 was restricted to the N- and C-terminal regions of p67, and there was no activity against the central portion between positions 313 and 583. So far, p67 sequence polymorphisms have been identified only in buffalo-derived T. parva parasites, but the consequence of these for vaccine development remains to be defined. The data indicate that optimizations of the current vaccination protocol against ECF should include boosting of relevant antibody responses to neutralizing epitopes on p67.

In the early part of this century, East Coast fever (ECF) was identified as a tick-transmitted disease of cattle in South Africa and was associated with cattle imported from East Africa in an effort to repopulate livestock that had been devastated by rinderpest (reviewed by Norval et al. [20]). The disease, endemic in much of eastern, central, and southern Africa, is caused by an intracellular protozoan parasite called Theileria parva and is transmitted primarily by the ixodid tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. The epidemiology of theileriosis is complicated by the presence of polymorphic traits between T. parva isolates and stocks associated primarily with different clinical symptoms and the presence of a wildlife reservoir in the Cape buffalo. In the past, subspecies status was given to T. parva (20, 25), but parasite isolates are now referred to as either cattle or buffalo derived (1) to describe the mammalian host origin.

Immune responses to the infective sporozoite and pathogenic schizont stages of T. parva play a role in mediating immunity to ECF. Cattle immunized by infection with cryopreserved sporozoites and given a simultaneous treatment regimen with tetracycline (22) acquire immunity that appears to be dependent on cell-mediated immune responses, in particular CD8+ schizont-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (reviewed by Morrison et al. [11]). Vaccinated cattle are, however, often susceptible to heterologous sporozoite challenges, and antigenic diversity between parasite isolates is likely to contribute to vaccine failure (11). There is no evidence for a role of antibodies against schizonts in mediating immunity (12). On the other hand, multiple sporozoite exposure results in the development of antibodies that neutralize sporozoites in an in vitro assay (14, 15). While the contribution of this response to immunity in the field is unknown, the observation has been exploited to develop an experimental antisporozoite vaccine based on a recombinant form of p67 (16), a stage-specific surface antigen that is the target of neutralizing antibodies.

We previously reported that recombinant p67 of a cattle-derived parasite induces sporozoite-neutralizing antibodies and immunity to ECF in about 60 to 70% of vaccinated cattle (13). Analysis of the gene encoding p67 from four cattle-derived parasites of different cross-immunity groups indicated that p67 is invariant in sequence, and in support of the prediction, p67-inoculated cattle showed similar levels of immunity against a homologous or heterologous challenge (18). In contrast to cattle-derived parasites, the gene encoding p67 in a buffalo-derived parasite exhibited polymorphic sequences (18). In an attempt to determine in vitro correlates with immunity in p67-vaccinated cattle, a number of immunological parameters were measured, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and neutralizing-antibody titers, antibody isotype, and avidity, but none were predictive of immune status. Attempts to measure proliferative T-cell responses to both recombinant and sporozoite-derived p67 were unsuccessful (13).

Here, we report on the sequence of p67 peptides recognized by murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that neutralize sporozoite infectivity and we compare this data with the linear peptide specificity of antibodies from cattle inoculated with recombinant p67 that were immune or susceptible to ECF. We also report on an analysis of p67 gene sequences from three more buffalo-derived parasite isolates. This study is an early step in the attempt to define protein and antibody epitope polymorphism in a candidate antisporozoite vaccine antigen for the control of ECF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Derivation and characterization of MAbs to recombinant p67 and production of bovine antisera.

The bacterial recombinant p67 NS1-p67 (13) was used to inoculate BALB/c mice. Spleen cells were fused with X63-Ag8.653 myeloma cells, and supernatants from the fusions were screened against the immunogen as previously described (14). Sporozoite neutralization assays were performed as described previously (13), and the isotypes of MAbs were determined by immunodiffusion against isotype-specific reagents (Bionetics Laboratory Products, Charleston, S.C.).

Cattle antibodies were raised to a synthetic peptide with the sequence LKKTLQPGKTSTGET, containing the epitope bound by MAb AR22.7 (Table 1). Briefly, 100 nmol of peptide (corresponding to about 163 μg) conjugated to tetanus toxoid, formulated in complete Freund’s adjuvant, was inoculated intramuscularly into two animals, BL280 and BL281. Each animal received three intramuscular boosts with the same amount of peptide in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant at 1-month intervals. Immunoblot analysis was carried out as described previously (13), and the blot was developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate.

TABLE 1.

p67 peptides bound by MAbsa

| MAb | Isotypeb | % SNAb | Pin no. | Peptide sequence | p67 residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR12.6 | IgG2a | 75 | 15 | SYTVTNLVQTQSQVQ | 105–119 |

| TpM12 | IgM | 70 | 23 | TKEEVPPADLSDQVP | 169–183 |

| AR22.7 | IgG1 | 94 | 27 | DEKELKKTLQPGKTS | 201–215 |

| 28 | LQPGKTSTGETTSGQ | 215–229 | |||

| 38.9 | IgG3 | 0 | 75 | EEEVKKILDEIVKDP | 585–599 |

| AR19.6 | IgG1 | 67 | 78 | LSDPSGRSSERQPSL | 609–623 |

| 79 | SERQPSLGPSLVITD | 617–631 | |||

| AR21.4 | IgG2a | 85 | 78 | LSDPSGRSSERQPSL | 609–623 |

| 79 | SERQPSLGPSLVITD | 617–631 | |||

| 23Fc | IgG3 | 98 | |||

| 1A7 | IgM | 100 | 79 | SERQPSLGPSLVITD | 617–631 |

| 80 | PSLVITDGQAGPTIV | 625–639 |

The sequences of synthetic p67 peptides encoded by positive pins as defined by Pepscan analysis are shown along with the positions of the sequence in cattle-type p67; sequences in bold are those shared between neighboring pins.

The MAb isotype and percent neutralization in the sporozoite neutralization assay (SNA) are indicated.

23F did not react with any pin.

Bovine anti-p67 sera were from cattle inoculated with recombinant NS1-p67 in previous experiments (13, 18). Samples were from animals that were clinically nonreactors to sporozoite challenge and thus solidly immune or from animals that experienced severe ECF and were indistinguishable from control cattle.

Pepscan analysis.

Synthetic peptides predicted from the Muguga stock of cattle-derived T. parva p67 gene sequence (19) were purchased from Chiron Mimotopes, Clayton, Australia. The peptide series started at position 9 (pin 3) of p67 and ended at the C-terminal residue at position 709 (pin 89). Pins 1 and 2 encode control peptides, and pins 90 to 95 encode peptides of a different parasite protein; they are therefore not relevant to this study. Each peptide was 15 amino acid residues long and overlapped neighboring ones by 7 residues; a total of 87 peptides were made. The reactivity of the block of peptides with murine MAbs or cattle antisera was measured as specified by the manufacturer. Briefly, the pins were incubated in the first antibody overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation, washed, placed in antibody conjugate, washed again, and then developed with the diammonium salt of 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as the substrate. Optical density (OD) readings were taken at 414 nm, and the results were represented graphically, minus the OD reading for control pins, against the pin number. The pins were recycled by treatment at 60°C for 10 min in a sonication bath with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) followed by rinsing in distilled water at 60°C. When not in use, the pins were air dried and stored desiccated at 4°C.

Parasite stocks and nucleic acids.

DNA was prepared from schizont-infected lymphoblastoid cell lines as previously described (3). Three buffalo-derived parasite isolates, each from a naturally infected animal, were analyzed: 7013 was from the Nanyuki area, Kenya (9); Hluhluwe 3 (Hlu3) was from Natal, South Africa (21); and KNP2 was from the Kruger National Park, South Africa (4). DNA from Hlu3 and KNP2 was provided by B. Allsopp, Onderstepoort Veterinary Institute, Onderstepoort, South Africa. Buffalo parasite 7014 (18) and the Muguga cattle parasite (19) have been described previously.

Sequence analysis of PCR-amplified DNA encoding p67.

DNA encoding p67 was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR as previously described (18). Briefly, DNA was subjected to 30 cycles of amplification with primers which overlap the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene and the PCR product was subjected to direct sequence analysis with a series of internal primers by using the fmol cycle-sequencing kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The complete gene sequence from each sample was determined. The Hitachi DNASIS/PROSIS programs and PC/GENE (IntelliGenetics, Inc.) were used to analyze the p67 gene sequences.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The accession numbers of the gene sequences described above are AF079175, AF079176, and AF079177.

RESULTS

Isolation of murine MAbs to recombinant cattle-derived p67.

Murine MAbs raised to sporozoite antigens have been described previously (6, 14). Three MAbs, TpM12, 23F, and 38.9, that immunoprecipitate sporozoite p67 have been well characterized. Only the first two of these neutralize sporozoite infectivity in vitro (15).

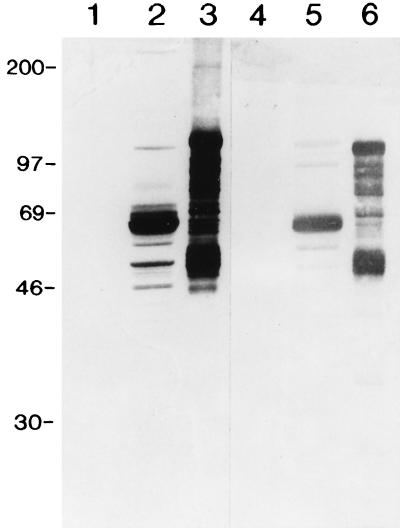

To generate additional anti-p67 MAbs, we raised antibodies to recombinant p67 and identified those that neutralized sporozoite infectivity in vitro. Four MAbs, two of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) subclass (AR12.6 and AR21.4) and two of the IgG2a subclass (AR19.6 and AR22.7), with significant sporozoite-neutralizing activity were isolated (Table 1). An example of the immunoblot reactivity of these MAbs with sporozoite p67 and recombinant p67 is shown for AR22.7 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot analysis of recombinant and sporozoite p67. Control tick salivary glands (lanes 1 and 4), purified sporozoites (lanes 2 and 5), and recombinant p67 (lanes 3 and 6) were probed with MAb AR22.7 (lanes 1 to 3) and bovine antiserum BL281 (lanes 4 to 6). Recombinant p67 migrates as a high-molecular-weight protein compared to the native molecule. Molecular weights are indicated in thousands.

Epitope mapping with murine MAbs.

Three MAbs raised to sporozoite p67 (TpM12, 23F, and 38.9) and four MAbs to recombinant p67 (AR series) were tested for reactivity with synthetic p67 peptides by the Pepscan method with an ELISA format. Ascitic fluid was initially used at a dilution of 1:1,000, but this gave low OD values, and we were advised by the manufacturer of the assay to use a dilution of 1:100. At this dilution, all MAbs except 23F, which did not bind any pin, bound to either a single pin or two neighboring pins (Table 1; some of the peptide sequence data has been reported previously [17]). MAbs AR19.6 and AR21.4 identified the same peptides but are of different isotypes and exhibit different levels of reactivity with the pins in ELISA (data not shown). Data for MAb 1A7 is from a previous publication (10).

Epitope mapping with bovine antibodies to recombinant p67.

A Pepscan analysis was also carried out with sera from animals inoculated with recombinant NS1-p67, except that each serum sample was diluted 1:500. Cattle anti-p67 sera were from 31 animals inoculated with recombinant p67 in previous experiments and obtained prior to sporozoite challenge (13, 18).

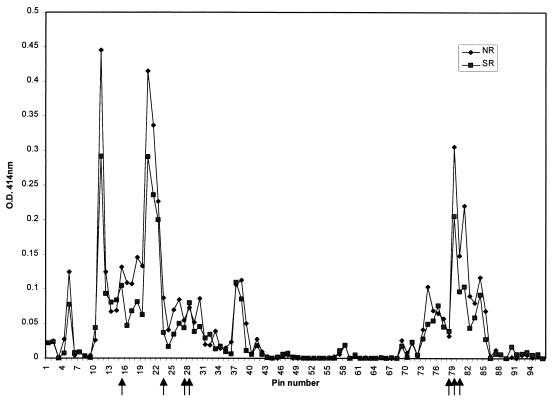

The specificity of serum samples from 16 cattle that were immune to sporozoite challenge was tested individually and compared with that of samples from 15 cattle that were susceptible to challenge. Figure 2 shows the results of the analysis for the two groups; the mean serum reactivity with each pin for animals immune to ECF and those susceptible to challenge is given. To ensure the integrity of the pins, the reactivity of the peptide block was tested at periodic intervals against a cocktail of MAbs.

FIG. 2.

Linear peptide sequence specificity of MAbs and bovine anti-p67 sera determined by Pepscan analysis. The average Pepscan results of data from antisera of 16 cattle that were nonreactors (NR) and immune and antisera of 15 cattle that were severe reactors (SR) and susceptible to ECF are shown. Peptides defined by sporozoite-neutralizing MAbs map to pins 15, 23, 27/28, 78/79, and 79/80 and are marked by arrows.

Antibody reactivity with pins was higher in sera from cattle that were immune to ECF than in sera from those that were susceptible, but there was a high degree of individual variation in responses (data not shown). There were only five areas of reactivity (OD of >0.1) of bovine anti-p67 antibodies with synthetic p67 peptides. These mapped to residues 25 to 39 (pin 5), 73 to 175 (pins 11 to 22), 281 to 296 (pins 37 and 38), 577 to 591 (pin 74), and 617 to 671 (pins 79 to 84). Analysis of variance of this data set indicated that there was no clear correlation between peptide specificity and immunity or susceptibility to ECF.

The bovine antibody responses to the p67 peptides identified by sporozoite-neutralizing MAbs were higher in the immune group than in the susceptible group (Fig. 2). There was measurable antibody to all five neutralizing epitopes, but a mean serum response of >0.1 OD unit was found to only three, namely, pin 15 bound by AR12.6, pin 79 bound by AR19.6 and AR21.4, and pin 79/80 bound by 1A7. It is interesting that AR19.6 and AR21.4 also bind to pin 78, but there is a very poor response to this peptide.

Bovine antibody responses to synthetic p67 peptide.

To determine the potential relevance of epitopes identified by sporozoite-neutralizing MAbs and the Pepscan analysis of bovine sera, we inoculated cattle with a synthetic peptide defined by one of the MAbs. Bovine antibodies to a peptide overlapping the epitope bound by MAb AR22.7 (pin 27/28) bound to both recombinant and sporozoite-derived p67 in immunoblots (Fig. 1) and also neutralized sporozoite infectivity in vitro to greater than 90% (data not shown). This epitope was chosen over others since MAb AR22.7 is the best in terms of its properties, including efficiency of sporozoite neutralization, binding to whole sporozoites, and immunoprecipitation of native antigen (data not shown).

DNA sequence characterization of the gene encoding p67 of three buffalo-derived T. parva isolates.

Genomic DNA from schizont-infected cell lines of parasite isolates 7013, KNP2, and Hlu3 was subjected to PCR, and in each case a single DNA fragment, about 2.2 kb in length, was amplified. This DNA was characterized by direct cycle sequence analysis, thereby overcoming problems associated with Taq DNA polymerase errors. In each of the three genes, the p67 open reading frame was disrupted by a 29-nucleotide sequence, which has been previously shown to be an intron (18, 19).

Comparative analysis of predicted p67 protein sequences.

The predicted number of amino acid residues encoded by the p67 open reading frame of KNP2, Hlu3, and 7013 is 709, 751, and 750, respectively. The previously reported cattle-type p67 and 7014 p67 proteins contain 709 (19) and 752 (18) residues, respectively. The calculated molecular mass of p67 varies from 75,367 to 79,374 Da. Each protein contains a predicted signal sequence at the N terminus and a hydrophobic C-terminal end. There are six, seven, and eight predicted N-linked glycosylation sites in p67 from Hlu3, KNP2, and 7013, respectively, and four of these are conserved in their location within the molecule; however, as in cattle-derived p67, each molecule contains a single cysteine residue. Allelic p67 sequence identities vary between 76 and 95%. Table 2 shows the peptide sequences of buffalo-derived parasite p67 corresponding to the sporozoite-neutralizing epitopes identified on cattle-type p67.

TABLE 2.

Sequence polymorphism of p67-neutralizing epitopes

| Parasite | Sequence corresponding to sporozoite-neutralizing MAba:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR12.6 (pin 15) | TpM12 (pin 23) | AR22.7 (pins 27/28) | AR19.6/22.4 (pins 78/79) | 1A7 (pins 79/80) | |

| Cattle | SYTVTNLVQTQSQVQ | TKEEVPPADLSDQVP | LQPGKTS | SERQPSL | PLSVITD |

| 7014 | -S------------- | --------------- | ------- | -G----- | ---G--- |

| KNP2 | -SRA----------- | --------------- | -P----- | -G----- | ---G--- |

| Hlu3 | -S------------- | --------------- | ------- | ------- | ------- |

| 7013 | -S------------- | --------------S | -P----- | -G----- | ------- |

The amino acid sequence of buffalo-derived parasite p67 peptides corresponding to sporozoite-neutralizing epitopes is shown; a dash indicates identity to the cattle-type residue.

DISCUSSION

Peptide epitopes bound by anti-p67 MAbs that neutralize T. parva sporozoite infectivity in vitro have been defined by Pepscan analysis. Together, five MAbs identify four epitopes, three located between residues 105 and 229 of p67 and one located between 617 and 623 (Table 1), suggesting that these sequences are exposed on the sporozoite surface. Systematic replacement of residues within a linear peptide epitope has shown that the identity of a minimum of 3 amino acid residues has to be maintained for MAb binding (8). Three MAbs, AR22.7, AR19.6, and AR21.4, reacted with two overlapping peptides; thus, the 7 amino acid residues in common are presumed to constitute part of the major recognition site for binding of the MAbs. AR12.6 and TpM12 bind to a single 15-mer peptide, and the relevant recognition site for MAb binding remains to be defined. The negative Pepscan data for MAb 23F suggests that this MAb binds to a discontinuous epitope. MAb 38.9 does not inhibit sporozoite infectivity, but it defines a p67 peptide sequence at residues 585 to 599.

Theileria annulata, the cause of bovine tropical theileriosis, contains a surface antigen called SPAG1 on sporozoites (26). This protein exhibits 47% sequence identity (64% similarity) to p67 and is antigenically related to p67 (10). One MAb, 1A7, raised to SPAG1, neutralizes both T. annulata and T. parva sporozoites and, by Pepscan analysis of p67, was found to bind to pins 79 and 80 (10). Thus, this MAb defines a fifth neutralizing epitope on p67, with the sequence PSLVITD at positions 625 to 631. SPAG1 contains the sequence PSLVI, suggesting that this is the core sequence to which 1A7 binds (10). MAbs AR22.7 and AR21.4 do not react with SPAG1 or inhibit T. annulata sporozoites (10); confirming this data, none of the peptide sequences defined by the neutralizing MAbs to p67 are found on SPAG1. However, a similar sequence (EEEVLKVLDELVKD) to that defined by MAb 38.9 (Table 1) is found in SPAG1 at positions 775 to 788. It will be of interest to determine the neutralization capacity of MAb 38.9 on T. annulata sporozoites and its immunoreactivity with SPAG1.

The p67 peptide sequences identified by the MAbs were used to search the nonredundant protein database. The sequence defined by TpM12 (TKEEVPPADLSDQVP) is intriguing, since part of the peptide sequence (underlined) showed a match to the N-terminal amino acid sequence of a 38-kDa protein from bovine serum (VPAADLSDQVPDTESETKILLQG), which associates with the membrane of in vitro-cultured Bordetella pertussis (2) and also to an internal portion of human complement C3 (QKEDIPPADLSDQVP) (5). The 38-kDa protein is likely to be a processed product of bovine complement C3, probably C3dg, and we have recently found the N-terminal sequence of the 38-kDa protein within cDNA encoding bovine complement C3 (19a). This sequence is just downstream from a potential factor I cleavage site identified for human C3 (5) and raises the question of the role of the similar sequence in p67. It is presumed that p67 interacts with molecules on host cells during the process of sporozoite entry. Protease inhibitors reduce the efficiency of sporozoite entry into host cells, suggesting a role for protein processing during entry (23). Hence, the C3 like-sequence in p67 may be important in associating with components on the host cell and/or as a site of proteolytic cleavage during sporozoite entry.

To confirm that at least one of the epitopes recognized by the neutralizing murine MAbs is of relevance to the bovine antibody response to p67, two cattle were inoculated with a synthetic 15-mer peptide containing the common 7-amino-acid sequence identified by AR22.7. Antibodies from both animals were found to be positive in immunoblots of p67 as well as in sporozoite neutralization assays. Based on the epitope-mapping data, we expressed an 80-amino-acid portion of p67 (from residues 572 to 651) which incorporates the peptides defined by MAb AR19.6/21.4 and 1A7, and preliminary experiments indicate that bovine antisera to this p67 region neutralize sporozoite infectivity (data not shown). The combined data supports the validity of the Pepscan approach to defining peptide epitopes.

We were interested in assessing the peptide specificity of cattle antibodies to recombinant p67 to identify antigenic regions of p67 and to establish if there was a correlation between the peptide specificity of an antibody response and immunity to sporozoite challenge, since this would aid vaccine development and optimization. Previous analysis of anti-p67 ELISA and sporozoite neutralization antibody titers had failed to reveal significant differences between immune and susceptible animals (13). As seen in Fig. 2, the central region of p67, residues 313 to 583, appears to be nonantigenic as far as the presence of linear peptide epitopes is concerned. This correlates well with a previous calculation of antigenicity by the PlotStructure program in the Genetics Computer Group package, which predicted antigenic sites to be located in the N- and C-terminal region of p67 (10). A remarkable observation in the Pepscan data is that in some cases bovine antisera do not exhibit specificity for overlapping peptide sequences (e.g., pin 11), thus behaving like some of the MAbs. Attempts to measure the anti-p67 peptide specificity by using serum from cattle hyperimmunized with sporozoite lysates or from cattle from the field with high ELISA titers to p67 were not successful due to the presence of a high background (data not shown). Thus, the specificity of cattle antibodies to sporozoite p67 remains to be defined.

Peptide-specific antibody responses in cattle inoculated with recombinant p67 that were susceptible to ECF were generally lower than in cattle that were immune to ECF (Fig. 2). Bovine antibody responses to peptides bound by MAbs AR12.6 (pin 15), TpM12 (pin 23), and AR22.7 (pins 27/28) were observed, but the mean responses were not high for either group. MAbs AR19.6/21.4 bind to pins 78/79, while the bovine antibodies reacted with pins 79/80. It could be argued that the bovine antibodies do not react with the core epitope SERQPSL bound by the MAbs but react mainly with the peptide sequence PSLVITD, shared between pins 79 and 80. This core sequence is bound by the neutralizing MAb 1A7 (10). Thus, the bovine anti-p67 response to pin 79 is likely to inhibit sporozoite infectivity, although it does not contain AR19.6 or AR21.4 specificity.

Analysis of variance of the bovine Pepscan data set indicated that the differences in antibody responses between immune and susceptible cattle were not statistically significant. It should be noted that the analysis we carried out was a single-time-point assessment at one antibody dilution, making it difficult to quantitatively compare data. A rigorous analysis, including affinity measurements, of the peptide specificity against a subset of the current peptides or peptides of different overlap and design may be more informative. It may also be instructive to examine serum samples after sporozoite challenge to determine if particular responses are enhanced by exposure to native p67. The Pepscan analysis does not measure responses to topographically folded epitopes, and, as shown by MAb 23F, these could contribute to immunity. Study of such parameters may yet reveal in vitro correlates between antibody responses and immunity to ECF.

We have previously reported that p67 sequence polymorphisms were detected only in a buffalo-derived parasite; cattle-derived parasites appear to contain identical p67 genes (18). Since buffalo are an important wildlife reservoir of the parasite, a knowledge of the extent of p67 amino acid sequence polymorphism is important for vaccine development because a variation in the epitopes involved in induction of the protective immune response or those that are targets of the protective immune response could contribute to vaccine failure. Data obtained with three buffalo parasites in this study and one analyzed previously reveal the presence of one or more amino acid substitutions in some of the epitopes identified by sporozoite-neutralizing MAbs (Table 2). Whether these substitutions abrogate MAb recognition remains to be determined, but at least one epitope is absolutely conserved in sequence. The contribution of conformation-sensitive epitopes to sporozoite inhibition is unknown, but, given the degree of p67 sequence identity, it is likely that at least some will be maintained. A case in point is the epitope defined by MAb 23F, since it also inhibits T. annulata sporozoites (10), arguing for conservation of this conformation on the p67/SPAG1 family of molecules.

Our current immunization protocol with recombinant p67 is not optimized, and an average 70% of the animals exhibit immunity to challenge. The Pepscan data has indicated that the bovine antibody response to linear epitopes identified by sporozoite-inhibitory MAbs is generally poor. Thus, it may be possible to improve the efficacy of the experimental vaccine by focusing the antibody response to these epitopes by incorporating a boost with synthetic peptides rather than with whole recombinant p67. Alternatively, the protective capacity of a peptide-based vaccine could be tested. Antibody responses to epitopes such as the one bound by MAb 23F could be induced by use of peptide mimotopes (7, 24). Currently, we are unable to comment on the role of cellular responses in immunity, but definition of T-cell epitopes is likely to gain importance when the protective capacity of peptide-based vaccines is investigated. In this context, it is interesting that the central region of p67, which does not appear to have linear B-cell epitopes, contains several Th-cell epitopes as judged by analysis of proliferative T-cell responses in cattle inoculated with sporozoite-derived p67 (17). In summary, our data suggest that antibody to any one of several epitopes of p67 inhibits sporozoite entry into host cells. Collective enhancement of the bovine immune response to these epitopes may be critical for vaccine success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Lessard and L. Duchateau for help with analysis of the Pepscan data and P. Spooner and B. Allsopp for provision of parasite material. We thank Jan Naessens for a critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

ILRI publication 98028.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. Classification of Theileria parva reactions in cattle. In: Dolan T T, editor. Theileriosis in eastern, central and southern Africa. Nairobi, Kenya: English Press Ltd.; 1989. pp. 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anwar H. Association of a 38kDa bovine serum protein with the outer membrane of Bordetella pertusis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:305–310. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90238-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad P A, Iams K, Brown W C, Sohanpal B, ole-MoiYoi O K. DNA probes detect genomic diversity in Theileria parva stocks. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;25:213–226. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins N E. The relationship between Theileria parva parva and Theileria parva lawrencei as shown by sporozoite antigen and ribosomal RNA gene sequence. Ph.D. thesis. Johannesburg, South Africa: University of Witswaterrand; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bruijn M H L, Fey G H. Human complement component C3: cDNA coding sequence and derived primary structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:708–712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbelaere D A E, Spooner P R, Barry W C, Irvin A D. Monoclonal antibodies neutralises the sporozoite stage of different Theileria parva stocks. Parasite Immunol. 1984;6:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1984.tb00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folgori A, Tafi R, Meola A, Felici F, Galfre G, Cortese R, Moncai P, Nicosia A. A general strategy to identify mimotopes of pathological antigens using only random peptide libraries and human sera. EMBO J. 1994;9:2236–2243. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geysen H M, Rodda S J, Mason T J. A prior delineation of a peptide which mimics a discontinuous antigenic determinant. Mol Immunol. 1986;23:709–715. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kariuki T M, Grootenhuis J G, Dolan T T, Bishop R B, Baldwin C. Immunization of cattle with Theileria parva parasites from buffaloes results in generation of cytotoxic T cells which recognise antigens common among cells infected with T. parva parva, T. parva bovis, and T. parva lawrencei. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3574–3581. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3574-3581.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knight P, Musoke A J, Gachanja J N, Nene V, Katzer F, Boulter N, Hall R, Brown C G D, Williamson S, Kirvar E, Bell-Sakyi L, Hussain K, Tait A. Conservation of neutralizing determinants between the sporozoite surface antigens of Theileria annulata and Theileria parva. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82:229–241. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison W I, Taracha E L, McKeever D J. Theileriosis: progress towards vaccine development through understanding immune responses to the parasite. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:177–187. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03119-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muhammed S L, Lauerman L H, Johnson L W. Effects of humoral antibodies on the course of Theileria parva (East Coast fever) of cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musoke A, Morzaria S, Nkonge C, Jones E, Nene V. A recombinant sporozoite surface antigen of Theileria parva induces protection in cattle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:514–518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musoke A J, Nantulya V M, Rurangirwa F R, Buscher G. Evidence for a common protective antigenic determinant on sporozoites of several Theileria parva strains. Immunology. 1984;52:231–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musoke A J, Nene V. Development of recombinant antigen vaccines for the control of theileriosis. Parassitologia. 1990;32:73–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musoke A J, Nene V, Morzaria S P. A sporozoite-based vaccine for Theileria parva. Parasitol Today. 1993;9:385–388. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musoke A J, Nene V, McKeever D. Epitope specificity of bovine immune responses to the major surface antigen of Theileria parva sporozoites. In: Chanock R M, Brown F, Ginsberg H S, Norrby E, editors. Vaccines 95. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nene V, Musoke A, Gobright E, Morzaria S. Conservation of the sporozoite p67 vaccine antigen in cattle-derived Theileria parva stocks with different cross-immunity profiles. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2056–2061. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2056-2061.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nene V, Iams K P, Gobright E, Musoke A J. Characterisation of the gene encoding a candidate vaccine antigen of Theileria parva sporozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;51:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90196-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Nene, V. Unpublished data.

- 20.Norval R A I, Perry B D, Young A S. The epidemiology of theileriosis in Africa. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potgieter F T, Stoltsz W H, Blouin E F, Roos J A. Corridor disease in South Africa: a review of current status. J South Afr Vet Assoc. 1988;59:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radley D E. Infection and treatment method of immunization. In: Irvin A D, Cunningham M P, Young A S, editors. Advances in the control of theileriosis. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1981. pp. 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw M K, Tilney L G, Musoke A J. The entry of Theileria parva sporozoites into bovine lymphocytes, evidence for MHC class I involvement. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:87–101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoute J A, Ballou W R, Kolodny N, Deal C D, Wirtz R A, Linder L E. Induction of humoral immune response against Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites by immunization with a synthetic peptide mimotope whose sequence was derived from screening a filamentous phage epitope library. Infect Immun. 1995;63:934–939. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.934-939.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uilenberg G, Perie N M, Lawrence J A, de Vos A J, Paling R W, Spanjer A A M. Causal agents of bovine theileriosis in South Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1982;14:127–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02242143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williamson S, Tait A, Brown C G D, Walker A, Beck P, Shiels B, Fletcher J, Hall R. Theileria annulata sporozoite surface antigen expressed in Escherichia coli elicits neutralizing antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4639–4643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]