Abstract

Experimental bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) infection can enhance Histophilus somni (Hs) disease in calves; we thus hypothesized that modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines containing BRSV may alter Hs carriage. Our objective was to determine the effects of an intranasal (IN) trivalent (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus [IBRV], parainfluenza-3 virus [PI3V], and BRSV) respiratory vaccine with parenteral (PT) bivalent bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) type I + II vaccine, or a PT pentavalent (BVDV type I and II, IBRV, BRSV, and PI3V) respiratory vaccine, on health, growth, immunity, and nasal pathogen colonization in high-risk beef calves. Calves (n = 525) were received in five truckload blocks and stratified by body weight (213 ± 18.4 kg), sex, and presence of a pre-existing ear-tag. Pens were spatially arranged in sets of three within a block and randomly assigned to treatment with an empty pen between treatment groups consisting of: 1) no MLV respiratory vaccination (CON), 2) IN trivalent MLV respiratory vaccine with PT BVDV type I + II vaccine (INT), or 3) PT pentavalent, MLV respiratory vaccine (INJ). The pen was the experimental unit, with 15 pens/treatment and 11 to 12 calves/pen in this 70-d receiving study. Health, performance, and BRSV, Hs, Mycoplasma bovis (Mb), Mannheimia haemolytica (Mh), and Pasteurella multocida (Pm) level in nasal swabs via rtPCR was determined on days 0, 7, 14, and 28, and BRSV-specific serum neutralizing antibody titer, and serum IFN-γ concentration via ELISA, were evaluated on days 0, 14, 28, 42, 56, and 70. Morbidity (P = 0.83), mortality (P = 0.68) and average daily gain (P ≥ 0.82) did not differ. Serum antibodies against BRSV increased with time (P < 0.01). There was a treatment × time interaction (P < 0.01) for Hs detection; on days 14 and 28, INT (21.1% and 57.1%) were more frequently (P < 0.01) Hs positive than CON (3.6% and 25.3%) or INJ (3.4 % and 8.4%). Also, INT had reduced (P = 0.03) cycle time of Hs positive samples on day 28. No difference (P ≥ 0.17) was found for IFN-γ concentration and Mb, Mh, or Pm detection. The proportion of Mh positive culture from lung specimens differed (P < 0.01); INT had fewer (0.0%; 0 of 9) Mh positive lungs than INJ (45.5%; 6 of 13) or CON (74.0%; 14 of 19). Vaccination of high-risk calves with MLV did not clearly impact health or growth during the receiving period. However, INT was associated with an altered upper respiratory microbial community in cattle resulting in increased detection and level of Hs.

Keywords: bovine respiratory disease, respiratory syncytial virus, respiratory vaccination

Intranasal MLV vaccination was associated with increased carriage of Histophilus somni in the naris, providing evidence that intranasal but not parenteral MLV vaccination can be associated with alterations in the carriage of this bacterial pathogen in the upper respiratory tract of cattle. Further research is needed to better understand how intranasal MLV vaccination impacts the respiratory microbiota and the clinical significance of such impact.

Introduction

Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is the disease most often reported by producers to affect feedlot cattle (Woolums et al., 2005). Despite significant research investment in antimicrobial and vaccine technologies, BRD has remained the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the feedlot for several decades. Veterinary feedlot consultants unanimously recommend vaccination against respiratory viruses in high-risk cattle upon arrival at the feedlot (Terrell et al., 2011). However, the percentage of feeder cattle that died of BRD was the same in 2007 as it was in 1991 (Miles, 2009) and anecdotal evidence suggests that BRD morbidity and mortality in the feedlot are increasing rather than improving. According to Rutten-Ramos et al. (2021), from 2010 to 2019, the death rate in the feedlot increased concurrently with days on feed. It seems most of the existing literature evaluates vaccine efficacy compared to unvaccinated controls. However, vaccine efficiency should be determined in the production environment using randomized, well-replicated field trials with a negative control treatment. Unfortunately, the USDA approval process for biologicals is not designed to examine field vaccine efficiency (Richeson et al., 2019). Veterinary and producer interest in intranasal (IN) respiratory vaccines to prevent BRD has increased concomitant with commercial availability, but a clear understanding of IN vaccine safety and efficiency is lacking.

Within the BRD complex, bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) has been associated with a predisposition to secondary bacterial infections. These bacteria include Histophilus somni (Hs), Mycoplasma bovis (Mb), Mannheimia heamolytica (Mh), and Pasteurella multocida (Pm). However, BRSV’s immunomodulatory effects can foster an environment for increased Hs colonization. Infection with Mh, Pm, or Hs requires bacteria-specific IgG2 (Th1 response) for disease resolution and subsequent protection (Gershwin et al., 2005), while Hs-specific IgE class antibodies are associated with enhanced pathogenesis of Hs (Corbeil et al., 2007). Likewise, calves infected with BRSV develop an IgE response to viral proteins in addition to other antigens encountered during infection (Stewart and Gershwin, 1989). The bovine respiratory syncytial virus has the ability to modulate the immune response towards a Th2 response that could impact vaccine safety, secondary bacterial infections, and natural infection. Adaptive immune memory enhances response to subsequent exposure to the same antigen. Ruby (1999) observed that the combination of Hs and BRSV parenteral (PT) MLV vaccination of sensitized cattle resulted in enhanced IgE production, increased bronchoconstriction, edema formation, chemotaxis, and introduction of exogenous histamine to contribute to IgE production. Gershwin et al. (2005) further evaluated this hypothesis in a dual BRSV and Hs challenge model. At necropsy, the dually-infected calves possessed significant gross lesions and large areas of pulmonary consolidation, yet calves that were challenged with BRSV alone had no gross lesions, and calves challenged with Hs alone had minimal focal atelectasis. In addition, the presence of IgE antibodies for Hs in co-infected calves was significantly greater than in those infected with Hs only. These results support the hypothesis that BRSV can shift the immune system towards a Th2 response that results in increased Hs colonization, immunopathogenic responses mediated by IgE, or both.

Our primary objective was to explore whether BRSV-containing MLV vaccines could influence Hs, Mh, Pm, and Mb detection in nasal swabs and serum IFN-γ concentration in high-risk beef calves housed in a research feedlot setting. A secondary objective was to evaluate the clinical efficiency of an IN, trivalent (IBRV, BRSV, PI3V) respiratory vaccine with PT, bivalent BVDV and a PT, pentavalent (BVDV type I and II, IBRV, BRSV, PI3V) respiratory vaccine compared to a negative control.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures were approved by the West Texas A&M University (WTAMU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee before study initiation (IACUC #2020.10.002). This trial was conducted from November 2020 to May 2021 at the WTAMU Research Feedlot, near Canyon, TX.

Arrival processing

A total of 525 crossbred beef calves (213 ± 18.4 kg), were acquired from an order buyer in central Texas. Upon arrival (d-1), individual body weight (BW), sex (bull [n = 129] or steer [n = 396]), and presence or absence of a pre-existing ranch tag were recorded. In addition, an ear tissue sample was collected to test for BVDV persistent infection (PI; Cattle Stats, Oklahoma City, OK), and each animal was affixed with a unique visual and electronic identification ear tag (Allflex Livestock Intelligence, Madison, WI). Cattle were also administered a growth promoting implant containing 200 mg progesterone, 20 mg estradiol benzoate, and 29 mg tylosin tartrate (Component E-S with Tylan, Elanco Animal Health, Greenfield, IN), an injectable clostridial vaccine with tetanus toxoid (Calvary 9, Merck Animal Health, Madison, NJ), and an injectable (Ivermax Plus, Aspen, Greeley, CO) and oral (Valbazen, Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ) antiparasitic. Calves were held overnight in a receiving pen with access to hay (0.5% BW), water, and 0.5% BW of a common starter ration. Cattle were blocked by the truckload (n = 5), stratified by arrival body weight, sex, and presence of ranch tag, and randomly assigned to experimental treatments. In addition, a random subset (n = 6) per pen was chosen for whole blood and nasal swab sampling. The following day (day 0), cattle were individually weighed, administered an M. haemolytica bacterin-toxoid (One Shot Cattle Vaccine, Zoetis), metaphylaxis with tildipirosin (Zuprevo, Merck Animal Health, Madison, NJ; 7-day post-metaphylactic interval), bulls were band castrated (Callicrate, No-Bull Enterprises, St. Francis, KS) and provided 1 mg/kg BW oral meloxicam (Unichem Pharmaceuticals, Hasbrouck Heights, NJ), and administered the appropriate MLV vaccine treatment. Administration and handling of vaccines and other products followed beef quality assurance guidelines.

Experimental design

This experiment consisted of three treatment groups evaluated over a 70-day receiving period: 1) negative control, no MLV respiratory vaccination (CON), 2) cattle intranasally administered (1 mL/nostril) a trivalent, MLV respiratory vaccine (Inforce 3, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) using a single-use canula and PT BVDV type I and II vaccine (Bovi-Shield BVD, Zoetis) given subcutaneously on day 0 (INT), and 3) cattle administered a pentavalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Bovi-Shield GOLD 5, Zoetis) subcutaneously on day 0 (INJ). Treatments were spatially arranged with an empty pen between vaccine treatment groups to minimize unwanted virus transmission between vaccine treatments and negative controls, due to the shedding of vaccine strain virus by vaccinated cattle. In addition, treatments were processed and sampled starting with CON, INJ, and then INT to mitigate the possibility of vaccine virus transmission during handling procedures. In this generalized complete block design, the pen served as the experimental unit. Treatment pens were replicated for a total of 15 pens per experimental treatment.

Cattle management

Cattle were housed in 20.8 m2 soil-surfaced pens with 50.6 cm of linear bunk space per animal and were fed the same starter ration throughout the entire 70-d trial. Cattle were fed once daily at approximately 0730 and feed bunks were visually evaluated at 0630 and 1,730 to determine the quantity of feed to offer each pen the subsequent day. Feed bunks were managed according to the standard procedure at the WTAMU Research Feedlot, with the goal of little or no residual feed remaining immediately before feeding at 0730. Feed samples were collected twice a week for dry matter (DM) determination and a diet composite was collected every two weeks for nutrient analysis at a commercial laboratory (Servi-tech Labs, Amarillo, TX). The DM analysis was conducted at the WTAMU Research Feedlot and was used to adjust diet formulation during the course of the study. Orts were also collected, weighed, and analyzed for DM to adjust DM intake at the end of each 14-d period.

Two steers tested positive for BVDV-PI and were removed from their study pen on day 1 and isolated to mitigate within and between pen effects of BVDV transmission. A clinical illness score (CIS, 1-4 scale) was assigned daily by trained investigators blinded to treatment pen assignment. A CIS of 1 described a “normal” steer with no signs of clinical illness. A CIS of 2 indicated a “moderately ill” steer. The appearance of a CIS 2 included gaunt, nasal/ocular discharge, lags behind others, and cough. Steers with a CIS of 3 were deemed “severely ill,” with purulent nasal/ocular discharge, labored breathing, and severe depression. Finally, CIS 4 corresponded to a “moribund” steer that was unresponsive to human approach and near death. Steers with a CIS 2 were removed from their home pen, brought into the processing barn, and restrained to record rectal temperature using a digital thermometer (GLA Agricultural Electronics, San Luis Obispo, CA). If the rectal temperature was ≥39.7 °C, that animal was considered a BRD case, treated with an antimicrobial, and immediately returned to its home pen. Steers assigned a CIS 3 were removed from their home pen and were classified as a BRD case and treated with an antimicrobial regardless of rectal temperature. If an animal was observed to be a CIS of 4, it was euthanized. Steers first diagnosed with BRD (BRD1) received 40 mg/kg BW of florfenicol (Nuflor, Merck Animal Health) and were assigned a 3-day post-treatment interval (PTI). Following the expiration of the PTI, steers were evaluated and treated using the same BRD case definition. Steers that qualified for a second BRD treatment (BRD2) received 11 mg/kg BW enrofloxacin (Baytril, Bayer Animal Health, Shawnee Mission, KS) and were assigned a 3-d PTI. Upon expiration of the PTI, steers were eligible for a third and final treatment (BRD3) with 6.6 mg/kg BW ceftiofur crystalline free acid (Excede, Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ). Steers deemed chronically ill (three antimicrobial treatments combined with <0.45 kg ADG since day 0 and/or BCS <3 out of 9) were removed from the study and placed into a critical care pen. In addition, days to BRD1, BRD2, and BRD3 and antimicrobial treatment costs were determined for each experimental treatment group.

Data collection and analysis

Initial (average of days −1 and 0), interim (days 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56), and final (average of days 69 and 70) individual BW were recorded. Dry matter intake was recorded and feed efficiency (G:F) was calculated for each interim period. Gain performance was calculated and displayed on a dead out basis.

Blood and serum analyses

Whole blood samples were collected from the designated subset of animals on days 0, 14, 28, 42, 56, and 70. Blood samples were collected via jugular venipuncture into two evacuated serum separator tubes (BD Vacutainer, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ; REF:367861) and centrifuged in the WTAMU Animal Health Laboratory at 1,250 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. On days 0, 14, 28, and 42, serum was divided into four aliquots, and three aliquots were divided for days 56 and 70. One serum aliquot from each time point was submitted to the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL; Canyon, TX) and Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University (Starkville, MS) for analysis of BRSV-specific antibody titer and serum interferon-γ (IFN-γ) concentration, respectively. The serum aliquot for BRSV titer was stored at −20° C and the serum aliquot for IFN-γ ELISA was stored at −80° C until all samples were collected prior to laboratory analysis. Detection of antibodies against BRSV was conducted using the virus neutralization assay described by Rosenbaum et al. (1970).

The serum concentration of IFN-γ was determined via ELISA with an intra-assay CV of ≤14.91%. Commercially available antibodies and standards were used (Kingfisher Biotech, Saint Paul, MN). Each well was coated with 100 µL of capture antibody working solution (0.6 µL of capture antibody per mL of Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline [DPBS]), covered with a plate sealer, and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The following morning, plates were aspirated, and 200 µL of blocking buffer (4% BSA [Sigma A7906] in DPBS) was added to each well. Plates were sealed and left to incubate at room temperature for 2 h. After the plate was aspirated, a 2-fold standard curve (15 ng/mL to 0.23 ng/mL) was plated in duplicates. Vortexed serum was then plated, 100 µL, in duplicate, in each well and dilutions were performed as needed in blocking buffer. Plates were then covered and left to incubate at room temperature for 1 h. Following incubation, plates were washed 4 times with washing buffer (0.05% TWEEN-20 in DPBS). Plates were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 100 µL of the detection antibody (0.5 µg/mL of blocking buffer, PBB0267B-050). Plates were washed an additional 4 times with washing buffer and then incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 100 µL of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (0.6 µL/mL of blocking buffer; EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA). Plates were washed 4 times with wash buffer, and 100 µL of TMB substrate (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA) was added to each well. Plates were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min and the enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 100 µL of stop solution (0.5 M H2SO4) to each well. Absorbance was measured on a plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) at 450 nm.

Whole blood samples were collected via jugular venipuncture into a single evacuated tube containing EDTA (BD Vacutainer K2EDTA; Becton Dickinson). Samples were chilled, transported, and analyzed in <4 h following collection. Complete blood count was determined on days 0, 14, 28, 42, 56, and 70 using an automated hematology analyzer (Idexx, ProCyte Dx Hematology Analyzer, Westbrook, ME) in the WTAMU Animal Health Laboratory.

Nasal swab analysis

Nasal swabs were collected on days 0, 7, 14, and 28 using a single nylon-flocked swab (PurFlock Ultra; Puritan Medical Products, Guilford, ME; 15 cm) and stored in additive-free 14 mL polystyrene tubes (Falcon; Corning, Inc., Corning, NY) at −80° C until submission to TVMDL for rtPCR testing to determine the presence and level of BRSV (Boxus et al., 2005), Hs (Moustacas et al., 2015), Mh, Pm, and Mb (Sachse et al., 2010). Mh and Pm analysis was adapted from Sachse et al. (2010) using primer probes that were developed in house with the following gene targets: Mh (Superoxidase dismutase [sod]) and Pm (transcriptional regulator genes, PM076). Cycle times were reported up to 40, with 36 considered the positive cutoff.

Lung pathology

Lung pathology, bacterial culture (Naikare et al., 2015), and antimicrobial sensitivity (MIC test) were conducted at the TVMDL on lung specimens from all mortalities that occurred in the study. Samples were collected using a disinfected knife following the line of demarcation in the left lung, placed in a Whirl-Pak® (Nasco Sampling/Whirl-Pak®, Madison, WI) sampling bag and immediately transported to TVMDL for culture and antimicrobial sensitivity determination.

Statistical analysis

This study was a generalized complete block design with an experimental unit replication pen within the block. Blocks consisted of five different truckload arrival groups. Performance outcomes (BW, ADG, DMI, F:G) were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS Inst., Cary, NC). The fixed effect of treatment was included in the model statement and pen*block was included as the random error term. Binomial health outcomes (morbidity, mortality) were analyzed using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS with the same model inputs. Repeated measures (blood and serum variables, rtPCR) were analyzed using PROC MIXED with repeated measures that evaluated the main effects of treatment, time, and their interaction. Compound symmetry was the covariance structure used for repeated measures analysis. Results from rtPCR were adjusted by removing each animal that had an rtPCR positive sample on day 0. Antibody titers and rtPCR cycle threshold values were log2- and log10-transformed, respectively, prior to statistical analysis, and other dependent variables were log10-transformed if it resulted in normal distribution as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test (PROC UNIVARIATE in SAS). Back-transformed means are reported for cycle times and the log2 transformed data were reported for antibody titers. Pen served as the experimental unit for all statistical analyses. Lung tissue cultures were analyzed using PROC GLIMMIX. Statistical significance was considered using an alpha-level of 0.05. If an F-test was statistically significant, mean separation was performed using the least significant differences test (pdiff in SAS) and treatment means were separated statistically using an alpha-level of 0.05 with a tendency considered for a P-value of 0.06 ≥0.10.

Results and Discussion

Feedlot performance

Body weight did not differ (P ≥ 0.74) at any time point during the study (Table 1). Likewise, there were no differences (P ≥ 0.82) observed in ADG. These data indicate that MLV respiratory vaccination of high-risk calves upon arrival did not clearly affect performance during the first 70-d in the feedlot. Overall (d 0 to 70) or interim DMI did not differ (P ≥ 0.22); however, feed efficiency (G:F) from days 0 to 56 was improved (P = 0.05) for CON because CON consumed slightly less feed but gained similarly during this time (Table 2). The inflammatory response following vaccination with a MLV typically elicits cytokines that promote tissue catabolism (Hughes et al., 2013) and the vaccines administered on day 0 may have contributed to the observation of reduced G:F because energy and protein are preferentially utilized by the inflammatory response in favor of growth. Arlington et al., (2013) observed similar results in heifers following vaccination; vaccinates had reduced ADG and G:F compared to non-vaccinated controls.

Table 1.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on performance of high-risk, newly received beef calves

| Item | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | INT | INJ | |||

| BW, kg | |||||

| Initial2 | 212.8 | 213.0 | 213.0 | 2.07 | 0.99 |

| d 14 | 223.9 | 224.4 | 221.6 | 3.89 | 0.74 |

| d 28 | 239.3 | 240.1 | 241.0 | 2.74 | 0.91 |

| d 42 | 264.8 | 265.1 | 263.4 | 3.24 | 0.92 |

| d 56 | 291.4 | 292.1 | 288.5 | 4.02 | 0.79 |

| Final3 | 311.4 | 312.9 | 310.4 | 4.52 | 0.93 |

| ADG, kg/d | |||||

| Initial to day 14 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.75 |

| Initial to day 28 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

| Initial to day 42 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.19 | 0.06 | 0.82 |

| Initial to day 56 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 0.05 | 0.58 |

| Initial to final | 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.39 | 0.05 | 0.86 |

CON=negative control, no respiratory virus vaccination; INT=cattle intranasally administered (1 mL/nostril) a trivalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Inforce 3, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) with parenteral BVDV types I and II vaccine (Bovi-Shield BVD, Zoetis) on day 0; INJ = cattle administered a pentavalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Bovi-Shield GOLD 5, Zoetis) on day 0.

Initial = average of BW on day −1 and 0.

Final = average of BW on days 69 and 70.

Table 2.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on dry-matter intake and feed efficiency of high-risk, newly received beef calves

| Item | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | INT | INJ | TRT | ||

| DMI, kg/d | |||||

| Initial2 to day 14 | 3.38 | 3.62 | 3.37 | 0.13 | 0.33 |

| Initial to day 28 | 4.32 | 4.62 | 4.42 | 0.12 | 0.22 |

| Initial to day 42 | 4.98 | 5.26 | 5.11 | 0.13 | 0.34 |

| Initial to day 56 | 5.56 | 5.84 | 5.67 | 0.15 | 0.48 |

| Initial to final3 | 6.06 | 6.29 | 6.13 | 0.16 | 0.59 |

| G:F, kg | |||||

| Initial to day 14 | 0.133 | 0.159 | 0.097 | 0.055 | 0.72 |

| Initial to day 28 | 0.217 | 0.211 | 0.221 | 0.011 | 0.83 |

| Initial to day 42 | 0.246 | 0.235 | 0.230 | 0.007 | 0.29 |

| Initial to day 56 | 0.253a | 0.241a,b | 0.235b | 0.005 | 0.05 |

| Initial to Final | 0.231 | 0.226 | 0.225 | 0.003 | 0.37 |

CON = negative control, no respiratory virus vaccination; INT = cattle intranasally administered (1 mL/nostril) a trivalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Inforce 3, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) with parenteral BVDV type I and II vaccine (Bovi-Shield BVD, Zoetis) on day 0; INJ = cattle administered a pentavalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Bovi-Shield GOLD 5, Zoetis) on day 0.

Initial= average of BW on days −1 and 0.

Final= average of BW on days 69 and 70.

Within a row, means without a common superscript differ, P ≤ 0.05.

Clinical health outcomes

There were no differences (P ≥ 0.83) in the overall morbidity percentage (BRD1; Table 3). No statistical differences (P = 0.17) were observed for the percentage of steers deemed chronically ill; however, CON had 7.43% chronically ill, followed by INJ (5.14%) and INT (2.86%). Mortality was not statistically different (P = 0.37); however, mortality percentage followed a similar numerical pattern to chronically ill; CON had 10.87% mortality, followed by INJ (7.55%) and INT (5.16%). Days to mortality was not statistically different (P = 0.61); INT treatment averaged 26.5 days to mortality, followed by INJ (22.0 d) and CON (21.9 d). There were no differences (P = 0.99) in total antimicrobial cost between treatments, which averaged $19.05/animal. These results indicate that respiratory vaccination of high-risk calves upon feedlot arrival did not significantly affect health outcomes during the receiving period, but additional research with larger sample size is needed to determine if the numerical trends observed in our study are repeatable and meaningful, or random. Our results agree with those of Marin et al. (1983), Duff et al. (2000), and Van Donkersgoed et al. (1990), where respiratory vaccination had no effect on morbidity or mortality in the feedlot setting. A housing limitation of the current study is that the spatial arrangement of treatment pens to control vaccine virus transmission between treatment groups led to the potential for pseudoreplication. That is, it could be debated that the three separate pens for each treatment group within a block, which all received the same vaccine treatment, were not actually three independent units. The authors considered this in their design but concluded that a more serious design flaw would have occurred if all nine individual treatment pens within truckload blocks were randomly distributed because it was not possible to have an empty pen between all pens and fenceline contact between INT and INJ or CON groups would have great potential to confound responses due to shedding of vaccine-origin virus from INT cattle.

Table 3.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on health outcomes of high-risk, newly received beef calves

| Item | Treatments1 | SEM | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | INT | INJ | |||

| BRD12, % | 54.60 | 58.86 | 58.41 | 0.83 | |

| BRD23, % | 30.96 | 32.27 | 30.85 | 0.98 | |

| BRD34, % | 24.69 | 17.01 | 21.89 | 0.47 | |

| Chronic5, % | 7.43 | 2.86 | 5.14 | 0.17 | |

| Respiratory mortality, % | 10.87 | 5.16 | 7.55 | 0.37 | |

| Days to | |||||

| BRD1 | 14.83 | 14.46 | 13.80 | 1.54 | 0.89 |

| BRD2 | 18.39 | 17.79 | 17.21 | 1.40 | 0.83 |

| BRD3 | 22.57 | 21.79 | 20.93 | 1.72 | 0.77 |

| Mortality | 21.88 | 26.47 | 22.00 | 4.46 | 0.61 |

| Antimicrobial costs5, $/hd | |||||

| Nuflor | 10.61 | 11.24 | 11.14 | 1.45 | 0.90 |

| Baytril | 4.50 | 4.53 | 4.40 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Excede | 3.79 | 2.70 | 3.45 | 0.69 | 0.53 |

| Total antimicrobial treatment costs5, $/hd | 18.96 | 19.08 | 19.12 | 2.28 | 1.00 |

CON = negative control, no respiratory virus vaccination; INT = cattle intranasally administered (1 mL/nostril) a trivalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Inforce 3, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI) with parenteral BVDV type I and II vaccine (Bovi-Shield BVD, Zoetis) on day 0; INJ = cattle administered a pentavalent, modified-live virus respiratory vaccine (Bovi-Shield GOLD 5, Zoetis) on day 0.

Percentage of cattle treated for bovine respiratory disease (BRD) at least once.

Percentage of cattle treated for BRD at least twice.

Percentage of cattle treated for BRD 3 times.

Percentage of cattle removed from study due to chronic respiratory illness.

Antimicrobial cost assumes the following: $0.68/mL for florfenicol (Nuflor, Merck Animal Health, Madison, NJ; first treatment), $0.58/mL for enrofloxacin (Baytril, Bayer Animal Health, Shawnee Mission, KS; second treatment), $2.27/mL for ceftiofur crystalline free acid (Excede, Zoetis; third treatment).

Hematology and serology

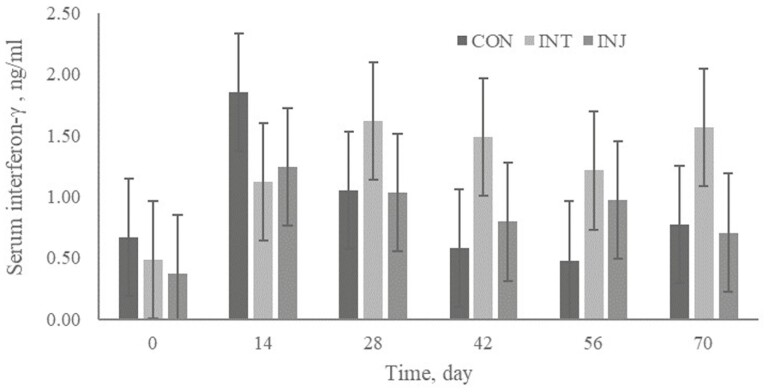

No treatment × day interactions or treatment effects (P ≥ 0.18) were observed for CBC variables (data not shown). The lack of difference in CBC variables were not surprising because there were no differences in morbidity; however, MLV vaccination can alter CBC variables (Hudson et al., 2020). Hughes et al. (2017) reported an increase in white blood cells from 24 to 48 h post-vaccination followed by a decrease 72 h post-vaccination. There was no treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.55) for serum IFN-γ concentration (Figure 1). Most viral infections are known to stimulate a more pronounced Th1 immune response for the most effective antiviral effect. The cytokine IFN-γ stimulates natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells that are both critical for resolving viral infection (Aberle et al., 1999). It is known that BRSV induces immunomodulation within the host to favor a Th2 response (Gershwin et al, 1994) that may result in less IFN- γ production. However, the lack of difference in IFN- γ in the current study could have been confounded by the IBRV, BVDV, and PI3V antigens administered to INT and INJ groups. However, CON did not receive any MLV antigen and it did not differ from INT or INJ regarding serum IFN- γ.

Figure 1.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on serum interferon- γ (ng/mL) of high-risk, newly received beef calves.

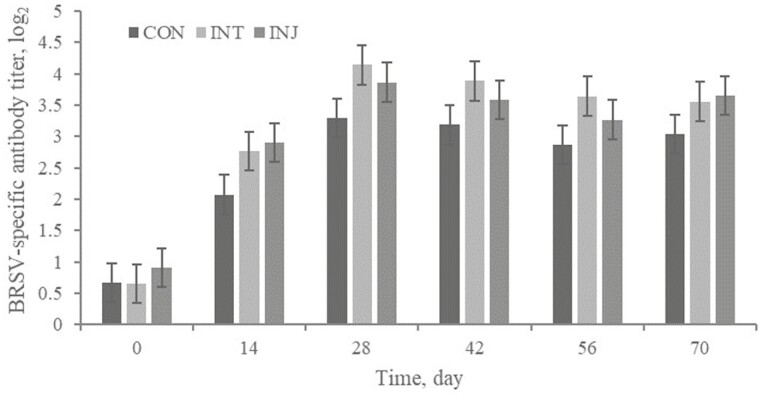

No treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.18) was observed for BRSV-specific antibody titer (Figure 2). As expected, serum antibody against BRSV increased with time (P < 0.01). However, this increase with time also existed for CON (d 0 relative to days 14, 28, 42, 56, and 70). The increase in BRSV-specific antibody titers from days 0 to 14 for CON indicates the presence of wild-type BRSV within this population of cattle prior to day 14. It has been previously reported that IN vaccines elicit both mucosal and systemic immune responses, but primarily mucosal; whereas, PT vaccines elicit a more robust systemic immune response as measured by serum antibody titer (Medina and Guzman, 2001). However, the BRSV-specific serum antibody response was numerically greatest for the INT (3.11 log2) cattle than INJ (3.03 log2) and CON (2.52 log2) in the current study. Kaufman et al. (2017) also reported an increased BRSV-specific serum antibody response in cattle administered an IN vaccine compared to PT.

Figure 2.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on bovine respiratory syncytial virus-specific antibody titer of high-risk, newly received beef calves.

Pathogen detection in nasal swabs

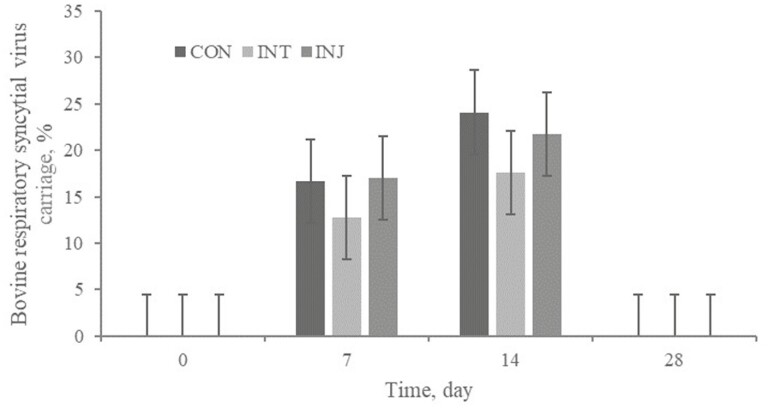

No treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.70) was observed for BRSV frequency of carriage (Figure 3). With BRSV-positive nasal swabs represented in the unvaccinated CON treatment on days 7 and 14, it is evident that wild-type or feral vaccine BRSV was circulating in this study population. Spatially arranged treatments reduced, but did not eliminate the possibility of vaccine-origin transfer of BRSV. However, these results coupled with increased BRSV-specific antibody titers for CON further support evidence of natural BRSV transmission. There was a tendency for a treatment × day interaction (P ≥ 0.06) for cycle threshold of BRSV positive swabs. Shedding of BRSV typically begins 3 to 4 d following infection and rarely endures beyond day 10 (Gershwin, 2007).

Figure 3.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on adjusted bovine respiratory syncytial virus frequency of carriage via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

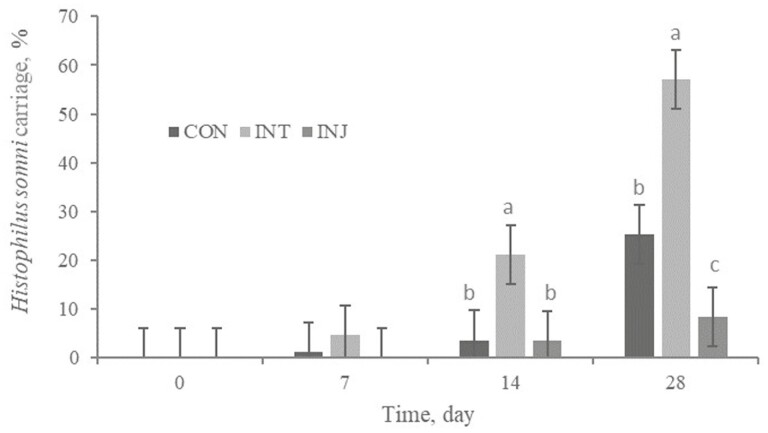

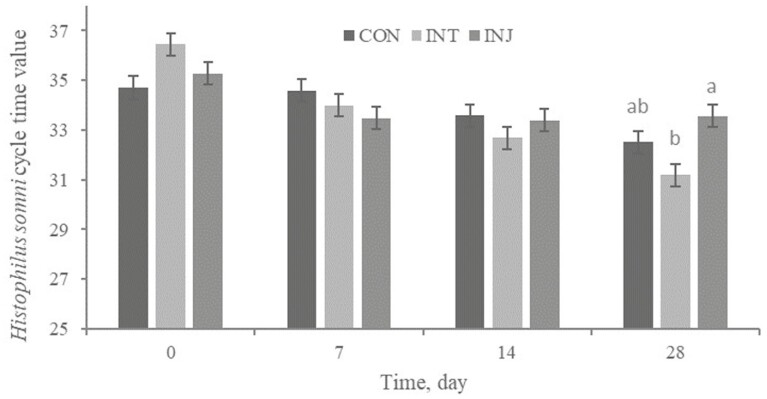

There was a treatment × time interaction (P < 0.01) for Hs presence in nasal swabs; on days 14 and 28, INT (21.1 and 57.1%) had more (P < 0.01) nasal swab specimens become Hs positive than CON (3.6 and 25.3%) or INJ (3.4 and 8.4%; Figure 4). Also, INT had reduced (P = 0.03) cycle threshold of Hs positive samples on days 28 (Figure 5). Therefore, intranasally vaccinated cattle had increased frequency of carriage and colonization of Hs. It is postulated that a BRSV infection can elicit a Th2 immune response and BRSV-specific IgE production (Gershwin et al., 2005). In addition, BRSV primes the immune system for increased Hs-specific IgE production following infection. A strong Th1 immune response is needed to resolve Hs infection (Corbeil, 2007). The immune response followed by IN vaccination may have created an environment that allowed for greater Hs colonization. H. somni typically endures 6 to 10 weeks in chronic infections. In addition, severe clinical signs are only visible for 48 h, and then infection can become subclinical for weeks (Gogolewski et al., 1987). The increase in Hs carriage for INT did not appear to impact clinical health outcomes in our study population and some health variables were numerically improved for INT.

Figure 4.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on H. somni frequency of carriage via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

Figure 5.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on H. somni cycle time values via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

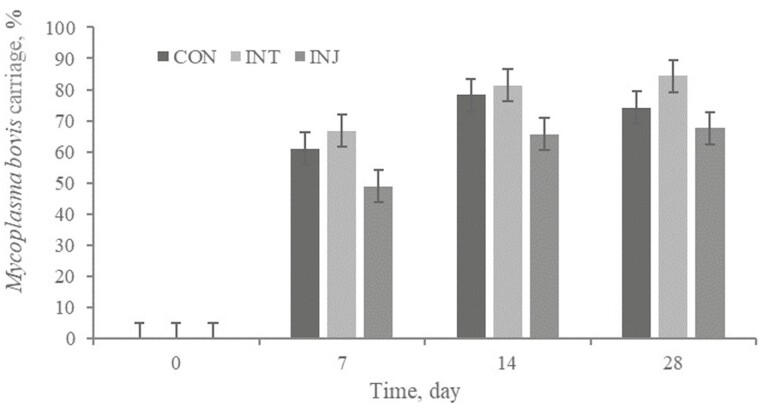

No treatment × day interaction (P = 0.24) for Mb frequency of carriage existed (Figure 6). However, there was a tendency (P = 0.06) observed for a treatment effect; parenterally vaccinated cattle had numerically less (45.6%) Mb present in the naris than CON (53.4%) or INT (58.1%). In addition, no treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.27) was observed for Mb cycle threshold value.

Figure 6.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on M. bovis frequency of carriage via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

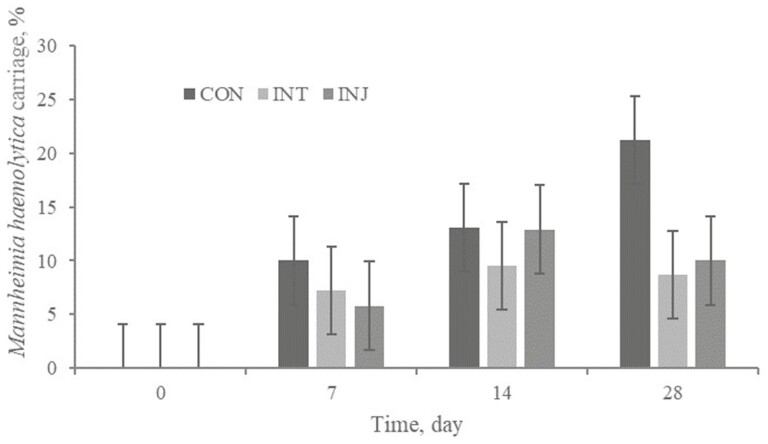

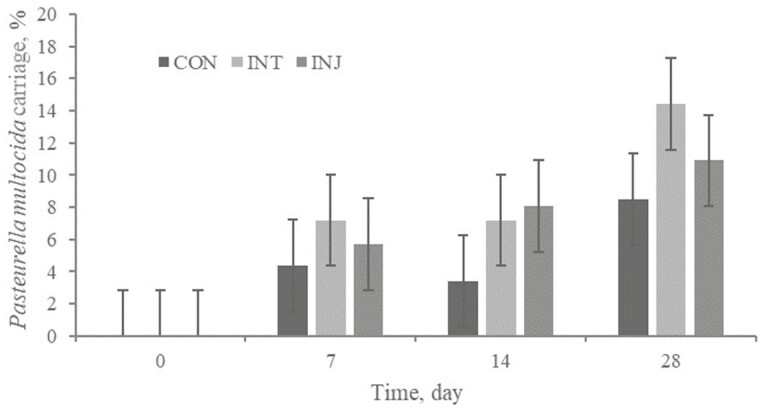

There was no treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.17) for Mh carriage (Figure 7). Numerically, CON were more likely to become Mh positive (11.1%) than INJ (7.2%) or INT (6.4%). Furthermore, Mh cycle threshold value had no treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.77). No treatment × day interaction or treatment effect (P ≥ 0.50) existed for Pm frequency of carriage (Figure 8). The cycle threshold values for Pm positive swabs were not impacted (P ≥ 0.30) by treatment, time, or their interaction.

Figure 7.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on M. hemolytica frequency of carriage via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

Figure 8.

Effect of respiratory vaccination and route of administration on P. multocida frequency of carriage via rtPCR in high-risk, newly received beef calves.

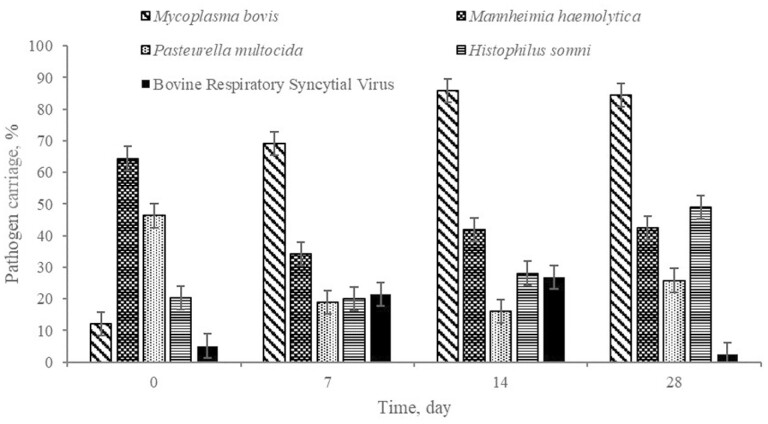

Overall pathogen prevalence is represented in Figure 9. On day 0, Mh was present in 64.4% of the sampled calves across all treatment groups. For decades, Mh has been considered the most predominant bacterial pathogen in relation to BRD (Griffin et al., 2010). However, Mh was the most frequently detected pathogen only on day 0. The remainder of sample days demonstrated Mb to be the most often detected; it was found in 69.1%, 85.8%, and 84.3% of the sampled calves on days 7, 14, and 28, respectively. It is perceived that Mb is an emerging cause of mortality in the feedlot (Gagea et al., 2006). By day 28, Hs was the second most detected of the 4 bacteria quantified from nasal swab samples. Both Mb and Hs carriage markedly increased over time (P < 0.01). Carriage of Mh and Pm decreased (P < 0.01) following administration of metaphylaxis with tildipirosin (Zuprevo, Merck Animal Health) on day 0.

Figure 9.

Overall pathogen frequency of carriage in the naris of high-risk, newly received beef calves.

Lung pathology

The most frequent bacterial pathogens isolated from the lungs of respiratory mortalities were Mh, Pm, and Hs, respectively. There was a treatment effect (P < 0.01) for the percentage of Mh positive culture from lung tissue specimens; INT had less (0.0%; 0 of 9) Mh positive lung tissue cultures than INJ (45.5%; 6 of 13) or CON (74.0%; 14 of 19). There was no difference (P > 0.37) between treatments for the frequency of Pm or Hs isolation. Furthermore, Mh had more (P < 0.01) isolates resistant to the antimicrobials used for metaphylaxis and treatment of BRD during this trial (tildipirosin, florfenicol, and enrofloxacin) than Hs (Table 4). However, the breakpoints used for ceftiofur resistance have long been under consideration by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (Luthje and Schwarz, 2006). For many decades, Mh has been considered the most predominant bacterial pathogen in relation to BRD (Griffin et al., 2010) and Mh is also commonly reported to be the most antimicrobial resistant respiratory bacteria (DeDonder and Apley, 2015). This could explain the numerical improvement in mortality observed for INT because increased Hs colonization in lieu of Mh may have resulted in predominance of a more antimicrobial susceptible causative agent. For high-risk populations of cattle, INT vaccination might alter the respiratory microbiome such that it impacts clinical health outcomes independent of, or in concert with the classical antigenic properties of a vaccine. It is important to note that the findings of this research may not be applicable to other vaccines, or other classes of cattle.

Table 4.

Antimicrobial resistance of bacteria cultured from lung specimens in calves dying of bovine respiratory disease1

| Item | Isolate | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mannheimia haemolytica | Histophilus somni | Pasteurella multocida | ||

| Resistant outcome, % | ||||

| Tildipirosin2 | 94.7a | 45.0b | 80.0ab | 0.03 |

| Florfenicol3 | 78.1a | 0.0b | 77.0a | 0.01 |

| Enrofloxacin4 | 78.1a | 0.0c | 48.7b | <0.01 |

| Ceftiofur crystalline free acid5 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.83 |

Percent resistant was determined using a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) test conducted at TVMDL, Canyon, TX.

(Zuprevo, Merck Animal Health, Madison, NJ; metaphylaxis).

(Nuflor, Merck Animal Health; first BRD treatment).

(Baytril, Bayer Animal Health, Shawnee Mission, KS; second BRD treatment).

(Excede, Zoetis, Kalamazoo, MI; third BRD treatment)..

a,b Within a row, means without a common superscript differ, P <0.05.

Conclusions

These data indicate MLV vaccination of high-risk calves at arrival, either parenterally or intranasally, did not clearly impact health or growth during the feedlot receiving period. However, INT was associated with increased prevalence of Hs in the naris, providing evidence that IN but not PT MLV vaccination alters the microbial community in the upper respiratory tract of cattle. Further research is needed to better understand how IN MLV vaccination might impact the respiratory microbiota and the clinical significance of such impact.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ADG

Average daily gain

- BW

Body weight

- BRD

bovine respiratory disease

- BRSV

bovine respiratory syncytial virus

- BVDV

bovine viral diarrhea virus

- CIS

clinical illness score

- CBC

complete blood count

- DMI

dry matter intake

- DM

dry matter

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- G:F

feed efficiency

- Hs

Histophilus somni

- IBRV

infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- IN

intranasal

- Mh

Mannheimia haemolytica

- MLV

modified-live virus

- Mb

Mycoplasma bovis

- PI3V

Parainfluenza-3 virus

- Pm

Pasteurella multocida

- PI

persistent infection

- PTI

post-treatment interval

- BRD1

primary BRD treatment

- BRD2

secondary BRD treatment

- BRD3

tertiary BRD treatment

- TVMDL

Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory

- WTAMU

West Texas A&M University

Contributor Information

Sherri A Powledge, Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, 79016 TX, USA.

Taylor B McAtee, Department of Agricultural Sciences, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, 79016 TX, USA.

Amelia R Woolums, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Starkville, 39759, MS, USA.

T Robin Falkner, Cattle Flow Consulting, Christiana, 37037 TN, USA.

John T Groves, Livestock Veterinary Service, Eldon, 65026, MO, USA.

Merilee Thoresen, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Starkville, 39759, MS, USA.

Robert Valeris-Chacin, VERO, Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, Canyon, 79015 TX, USA.

Funding

A.W. and J.R. have received research funding and honoraria for consulting and seminar presentations from companies that manufacture and market vaccines for administration in cattle. T.R.F. is currently employed by Elanco Animal Health.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No other known conflicts exist for authors.

Literature Cited

- Aberle, J. H., Aberle S. W., Dworzak M. N., Mandl C. W., Rebhandl W., Vollnhofer G., Kundi M., and Popow-Kraupp T... 1999. Reduced interferon-gamma expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 160:1263–1268. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9812025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlington, J. D., Cooke R. F., Maddock T. D., Araujo D. B., Moriel P., DiLorenzo N., and Lamb G. C... 2013. Effects of vaccination on the acute-phase protein response and measures of performance in growing beef calves. J. Anim. Sci. 91:1831–1837. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxus, M., Letellier C., and Kerkhofs P... 2005. Real Time RT-PCR for the detection and quantitation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus. J. Viro. Met. 125:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbeil, L. B. 2007. Histophilus somni host–parasite relationships. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 8:151–160. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeDonder, K. D., and Apley M. D... 2015. A literature review of antimicrobial resistance in pathogens associated with bovine respiratory disease. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 16:125–134. doi: 10.1017/S146625231500016X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff, G. C., Malcolm-Callis K. J., Walker D. A., Wiseman M. W., Galyean M. L., and Perino L. J... 2000. Effects of intranasal versus intramuscular modified live vaccines and vaccine timing on health and cattle performance by newly received beef cattle. Bov. Pract. 3:66–71. doi: 10.21423/bovine-vol34no1p66-71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagea, M. I., Bateman K. G., Shanahan R. A., van Dreumel T., McEwen B. J., Carman S., Archambault M., and Caswell J. L... 2006. Naturally occurring Mycoplasma bovis–associated pneumonia and polyarthritis in feedlot beef calves. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 18:29–40. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin, L. 2007. Bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection: immunopathogenic mechanisms. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 8:207–213. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin, L. J., Himes S. R., Dungworth D. L., Giri S. N., Friebertshauser K. E., and Camacho M... 1994. Effect of bovine respiratory syncytial virus infection on hypersensitivity to inhaled. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 104:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000236712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershwin, L. J., Berghaus L. J., Arnold K., Anderson M. L., and Corbeil L. B... 2005. Immune mechanisms of pathogenetic synergy in concurrent bovine pulmonary infection with Haemophilus somnus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 107:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolewski, R. P., Leathers C. W., Liggit H. D., and Corbeil L. B... 1987. Experimental Haemophilus somnus pneumonia in calves and immunoperoxidase localization of bacteria. Vet. Pathol. 24:250–256. doi: 10.1177/030098588702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, D., Chengappa, M. M., Kuszak, J., and McVey, D. S.. 2010. Bacterial pathogens of the bovine respiratory disease complex. Vet. Clin. Food Animal. 26: 381–-3948.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. E., Tomczak, D. J., Kaufman, E. L., Adams, A. M., Carroll, J. A., Broadway, P. R., Ballou, M. A., and Richeson, J. T.. 2020. Immune responses and performance are influenced by respiratory vaccine antigen type and stress in beef calves. Animals. 10: 1119-1135. Doi: 10.3390/ani10071119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, H. D., Carroll J. A., Burdick Sanchez N. C., Roberts S. L., Broadway P. R., May N. D., Ballou M. A., and Richeson J. T... 2017. Effects of dexamethasone treatment and respiratory vaccination on rectal temperature, complete blood count, and functional capacities of neutrophils in beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 95:1502–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, H. D., Carroll J. A., Sanchez N. C., and Richeson J. T... 2013. Natural variations in the stress and acute phase responses of cattle. Innate Immun. 20:888–896. doi: 10.1177/1753425913508993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, E. L., Davidson J. M., Beck P. A., Roberts S. L., Hughes H. D., and Richeson J. T... 2017. Effect of water restriction on performance, hematology and antibody responses in PT or intranasal modified-live viral vaccinated beef calves. Bov. Pract. 51:174–183. doi: 10.21423/bovine-vol51no2p174-183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luthje, P., and Schwarz S... 2006. Antimicrobial resistance of coagulase-negative staphylococci from bovine subclinical mastitis with particular reference to macrolide–lincosamide resistance phenotypes and genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:966–969. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin, W., Wilson P., Curtis R., Allen B., and Acres S... 1983. A field trial, of preshipment vaccination, with intranasal infectious bovine rhinotracheitis-parainfluenza-3 vaccines. Can. J. Comp. Med. 47:245–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina, E., and Guzman, C. A.. 2001. Use of live bacterial vaccine vectors for antigen delivery: potential and limitations. Vaccine. 19(13–14):1573–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles, D. G. 2009. Overview of the North American beef cattle industry and the incidence of bovine respiratory disease (BRD). Anim. Health Res. Rev. 10:101–103. doi: 10.1017/S1466252309990090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustacas, V. S., Silva T. M. A., Costa E. A., Costa L. F., Paixao T. A., and Santos R. L... 2015. Real-time PCR for detection of Brucella ovis and Histophilus somni in ovine urine and semen. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 67:1751–1755. doi: 10.1590/1678-4162-8038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naikare, H., Bruno D., Mahapatra D., Reinish A., Raleigh R., and Sprowls R... 2015. Development and evaluation of a novel Taqman real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of Mycoplasma bovis: comparison of assay performance with a conventional PCR assay and another Taqman real-time PCR assay. Vet. Sci. 2:32–42. doi: 10.3390/vetsci2010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richeson, J. T., Hughes H. D., Broadway P. R., and Carroll J. A... 2019. Vaccination management of beef cattle: delayed vaccination and endotoxin stacking. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 35:575–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, M. J., Edwards E. A., and Sullivan E. J... 1970. Micromethods for respiratory virus sero-epidemiology. Health Lab. Sci. 7:42–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby, K. W. 1999. Immediate (type-1) hypersensitivity and Haemophilus somnus. [Ph.D. thesis]. Ames (IA):Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten-Ramos, S. C., Simjee S., Calvo-Lorenzo M. S., and Bargen J. L... 2021. Population-level analysis of antibiotic use and death rates in beef feedlots over ten years in three cattle-feeding regions of the United States. JAVMA. 259:1–7. doi: 10.2460/javma.20.10.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse, K., Sala H. S. H., Diller R., Schubert E., Hoffmann B., and Hotzel H... 2010. Use of a novel real-time PCR technique to monitor and quantitate Mycoplasma bovis infection in cattle herds with mastitis and respiratory disease. Vet. J. 186:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, R. S., and Gershwin L. J... 1989. Detection of IgE antibodies to bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 20:313–323. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell, S. P., Thomson D. U., Wileman B. W., and Apley M. D... 2011. A survey to describe current feeder cattle health and well-being program recommendations made by feedlot veterinary consultants in the United States and Canada. Bov. Pract. 45:140–148. doi: 10.21423/bovine-vol45no2p140-148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Donkersgoed, J., Janzen E. D., and Harland R. J... 1990. Epidemiological features of calf mortality due to hemophilosis in a large feedlot. Can. Vet. J. 31:821–825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolums, A. R., Lonergan G. H., Hawkins L. L., and Williams S. M... 2005. Baseline management practices and animal health data reported by US feedlots responding to a survey regarding acute interstitial pneumonia. Bov. Pract. 39:116–124. doi: 10.21423/bovine-vol39no2p116-124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]