Abstract

Background:

There is a paucity of research involving older autistic people, as highlighted in a number of systematic reviews. However, it is less clear whether this is changing, and what the trends might be in research on autism in later life.

Methods:

We conducted a broad review of the literature by examining the number of results from a search in three databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO) across four age groups: childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and older age. We also examined the abstracts of all the included articles for the older age group and categorized them under broad themes.

Results:

Our database search identified 145 unique articles on autism in older age, with an additional 67 found by the authors (hence, the total number of articles in this review is 212). Since 2012, we found a 392% increase in research with older autistic people, versus 196% increase for childhood/early life, 253% for adolescence, and 264% for adult research. We identify 2012 as a point at which, year-on-year, older age autism research started increasing, with the most commonly researched areas being cognition, the brain, and genetics. However, older adult research only accounted for 0.4% of published autism studies over the past decade.

Conclusions:

This increase reflects a positive change in the research landscape, although research with children continues to dominate. We also note the difficulty of identifying papers relevant to older age autism research, and propose that a new keyword could be created to increase the visibility and accessibility of research in this steadily growing area.

Keywords: older age, aging, autism, autistic people

Community brief

Why is this topic important?

Autistic children grow into autistic adults, and autistic adults grow old. However, there is very little research about older autistic people. This is important so we know how to support older autistic people.

What is the purpose of this article?

We wanted to examine how autism research activity has changed over time with respect to four life stages: infancy, childhood and adolescence, adulthood, and older age. We then more closely looked at older age autism research to point out important gaps where more research is needed.

What did the authors do?

We conducted a broad review of the literature on autism and described what life stages are studied in published research. We looked at how the amount of research on different life stages has changed over time. We further examined studies focused on older age and summarized the topics covered.

What did you find about this topic?

Our review estimates that only 0.4% of autism-related publications over the past decade are about older autistic people. We identify 2012 as a turning point since when the number of studies has markedly increased year-on-year. Encouragingly, the percentage increase in autism research over the past decade is greater for older age research (392% rise) than childhood/early life (196%), adolescence (253%), or adulthood research (264%).

What do the authors recommend?

We suggest that there are many research areas that need addressing. Specifically, more research is needed on social isolation and the practicalities of living arrangements for older autistic people, as well as more studies including older autistic adults with intellectual disability.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

We do not think that our findings will immediately benefit the lives of autistic people. However, we do hope to draw attention to topics where research is needed to improve the lives of autistic older people. We also suggest that a new keyword could be created that researchers could then include in their articles to help autistic people and those interested in autism and aging find relevant writings.

Introduction

“Although much [research] is carried out with respect to young individuals with ASD, there is an urgent need to address the needs of the current population of older individuals with ASD.”1 Mukaetova-Ladinska et al.'s study drew attention to the scarcity of aging research with older autistic people after examining the literature between 1946 and 2011. In the intervening years what has changed in this respect? We decided to mark another decade in autism research by re-examining this question.

Several reviews have pointed out the dearth of research with older autistic participants.2–5 In America, as of 2019, ∼35.5% of the population (c.117.0 million people6) were aged 50 years or older,† and the proportion is similar in the United Kingdom (37.7%, c.25.2 million people7). A U.K. population survey reported an autism prevalence of around 1% in adults,8 suggesting that there could be many millions of people aged older than 50 years who would meet diagnostic criteria, although most are not diagnosed (the “lost generation”9). Clearly, it is a pressing concern to identify the state of autism research with older samples of autistic adults.

Research attention is slowly encompassing older autistic people, but as yet, there is no evidence to show how quickly interest in this area is growing. Thus, the aim of this perspective was to track the rates of autism publications, indexed in three databases. We update the search strategy of Mukaetova-Ladinska and colleagues (described in figure 1 of that article) to assess, in 2021, how autism research is distributed across the age categories of childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and older age.

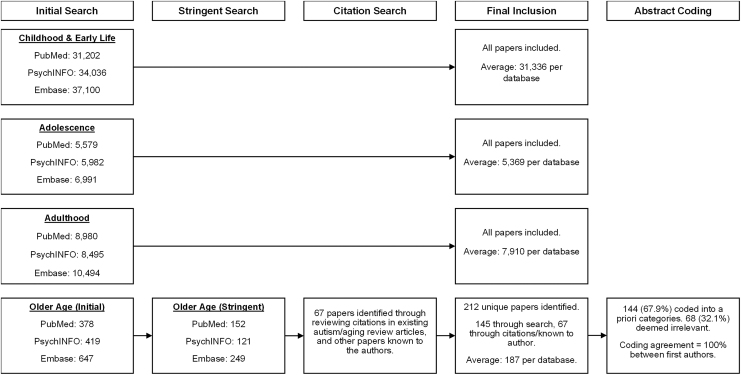

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the process of data collection for the four age bands used in the search.

Moreover, we identify the rate of publication of autism research with older autistic participants. Finally, we draw attention to broad categories of the search records according to the topic of each study (e.g., cognitive, genetic). While previous aging reviews have tended to be systematic, we opted for a broad review of the literature to gain an overview of the state of autism aging research and trends over time.10 This enabled us to chart how publication trends have changed over time and provide a qualitative schema for organizing older autism research.

Positionality

One of the first authors, D.M., is a late-diagnosed autistic adult, with a Bachelor's degree in Health and a Master's degree in Psychology. Currently, D.M. is completing a PhD to examine issues of outcome and quality of life (QOL) for older autistic people. D.M.'s research interests are the QOL of autistic people and aging as an autistic person. G.R.S. has a Bachelor's degree in Psychology, a Master's degree in Genes, Environment and Development in Psychology and Psychiatry (GEDPP), and a PhD on aging and autism. His research interests focus on the health, well-being, and cognition of middle-aged and older autistic (and high autistic trait) adults.

S.J.C. has a Bachelor's degree in Applied Psychology, a Master's degree in GEDPP, and is currently undertaking a PhD. Her PhD and research interests focus on mental health and QOL in autistic adults with a particular emphasis on how these outcomes might be different for other neurodivergent adults (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]) or those who are neurodivergent in multiple ways (e.g., autistic with ADHD). F.H. has worked in autism research for more than 30 years, following an undergraduate degree in Experimental Psychology and a PhD on autism. She is the primary PhD supervisor for D.M., G.R.S., and S.J.C. All the authors share a neurodiversity perspective that recognizes that the different way in which autistic people process the world can be disabling in a society designed by and for non-autistic people.

Methods

Search strategy

First, we designed a search based on Mukaetova-Ladinska et al.'s search strategy. We opted to search not only PubMed, as Mukaetova-Ladinska and colleagues did, but also Embase and PsycINFO to capture as broad a range of research topics as possible. All searches (childhood and early life, adolescence, adulthood, and older age) for each of the three databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase) were exported to Endnote,‡ and results were deduplicated.

Both the first authors created an a priori set of themes to use to code each study based on common research topics in the autism and aging literatures. These themes were then refined and finalized through group discussions with the third and fourth authors. Each first author then independently coded the abstracts according to the themes. Once initial coding was completed, these authors discussed the coded abstracts to reach 100% agreement.

Our first strategy replicated Mukaetova-Ladinska and colleagues' initial search terms, plus some additional terms. The autism terms were autism*, autism spectrum disorder, autistic*, autistic disorder, autistic symptoms, Asperger*, and PDD-NOS. The aging terms varied by age group. We used terms for: (1) infancy (toddler, infant, infancy) and childhood (child*, children); (2) adolescence (adolescence, adolescent*, teen*); (3) adulthood (adult*, young adult*); and (4) older age (old age*, older age, older adult, elder*, senior, late* adulthood). See Supplementary Material S1 for a comparison between the present search terms, and the search terms used by Mukaetova-Ladinska et al. See Supplementary Material S2 for an example search strategy using AND/OR terms. Searches were restricted to the title and abstract only.

This initial search strategy brought numerous false-positive results in the older age search; for example, including the search term “senior” returned abstracts about “high school seniors” or “senior management.” As we wanted to maximize true-positive hits but minimize these false positives, we refined our search strategy. To do so, we used the same approach as above, but added the following terms (using the NOT function); child*, infan*, youth, school, senior manag*. The NOT function aims to exclude irrelevant hits (and when combined with the “*” wildcard, to exclude permutations of irrelevant hits); the aim of this was to exclude false positives such as “older children.” This is referred to as our “stringent search” below.

To ensure the completeness of our search, we identified review articles that our search strategy retrieved and checked the reference list for any relevant articles. In this way, and based on our own knowledge of the literature, we added in any articles that were relevant but not returned by the search strategy.

Finally, abstracts from the stringent older adult search were categorized into an a priori set of research topics. D.M. and G.R.S. coded the abstracts individually and then agreed on the final categorization. These research topics were derived from common autism research areas and the authors' knowledge of the literature. Abstracts were deemed relevant and given a category if they included a clear reference to autism in older age or included autistic people aged 50 years and older. An irrelevant category was created to account for abstracts that included no reference to autism in older age. Abstracts with multiple themes were coded into their primary topic area. See Supplementary Material S3 for the abstract screening flow diagram.

Results

A final total of 212 unique articles were identified by our stringent older adult search criteria. The database search yielded a total of 145 unique articles across the 3 search engines used, with an additional 67 articles being added by the authors after checking reference lists of relevant review articles and/or based on their knowledge of the literature (see Fig. 1 for a full breakdown of the search strategy for each age group). Table 1 shows the number of results by database and age group. Figure 2 shows the average database N of results, by age group, published before and after 2012 for the stringent search strategy. See Supplementary Material S3 for full database N breakdown.

Table 1.

Number of Records Identified in the Search, Sorted by Age Group and Database

| PubMed | PsycINFO | Embase | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood and early life | 31,919 | 35,138 | 37,561 | 34,873 |

| Adolescence | 5607 | 6046 | 7018 | 6224 |

| Adulthood | 9011 | 8612 | 10,540 | 9388 |

| Older age (initial) | 291 | 419 | 647 | 452 |

| Older age (stringent) | 137 | 124 | 250 | 187 |

Note: A subtotal of 145 unique older age articles were identified across the 3 stringent searches. An additional 67 articles were identified through reference searching and articles known to the authors, making the final total of unique older age articles n = 212.

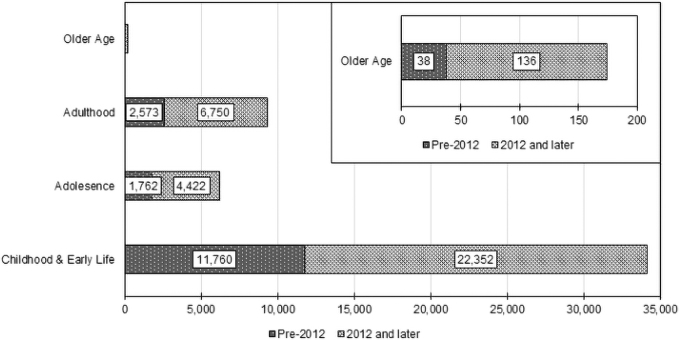

FIG. 2.

The main graph illustrates the average number of search results from each database using each age group search criteria (1) pre-2012 and (2) 2012 and later (i.e., after Mukaetova-Ladinska et al.'s study). The inset graph illustrates the number of older age search results with a reduced axis scale.

Is there a trend over time?

We identified a sharp increase in the number of autism-related publications since 2010. Specifically, for autism older age articles, we found that the number of publications rose from an average of 1 article per year in the years before 2012 (i.e., before Mukaetova-Ladinska et al.'s review) to an average of 14 articles per year over the 9 years since. When comparing the average number of articles on older adults identified in our stringent search of the 3 databases (N = 187) articles, a total of 136 were published in, or after, 2012. See Figure 2 for a visualization of this trend.

When considering the percentage increase in the number of publications since 2012 (averaged across the three databases in the search), childhood and early life research has increased by 196%, with a 253% increase for adolescence research, 264% for adult research, and finally 392% older age research (identified through the stringent search). Yet, despite an almost fourfold increase, the older age research (identified through the stringent search) only accounts for 0.4% of the new publications since 2012, with childhood and early life research accounting for 67%, 13% by adolescence research, and 20% by adulthood research.

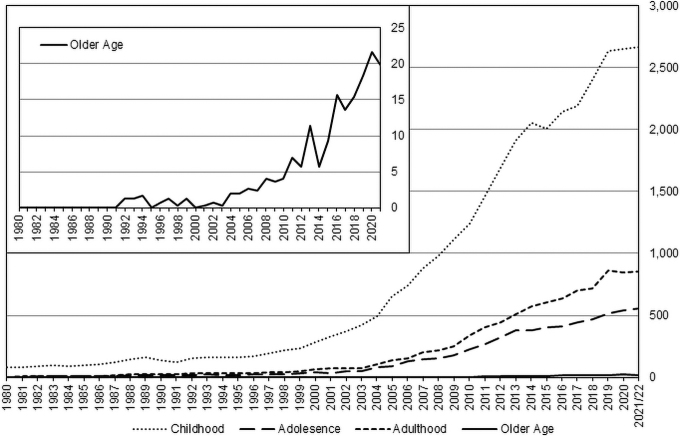

Finally, we examined the changes in number of publications per year, for each age band (childhood adolescence, adulthood, and stringent older age search). The trend is depicted in Figure 3. We can observe a steady increase in abstracts for each age band across time (the increase in older age is obscured by the scale of the graph—see inset panel of Fig. 3). Encouragingly, 2010 seems to mark an increase in older age autism research, with around four times as many publications in 2020 as in 2010.

FIG. 3.

The main graph illustrates the publication trends for the childhood, adolescent, adult, and older adult searches. The inset graph illustrates the number of older age search results over time with a reduced axis scale. The y-axes denote number of studies published.

What research is being conducted with older autistic adults?

Table 2 shows the number of articles found that fell into our different topic categories. Studies that examine general health (N = 17, 8.0% of all articles in the stringent search), genetics/molecular aspects (N = 16, 7.5%), and cognition (N = 15, 7.1%) were most common. A large number of review articles were also found (N = 16, 7.5%). Several studies examined autistic traits (N = 11, 5.2%), with slightly fewer focusing on support needs (N = 9, 4.2%) or QOL (N = 8, 3.8%). Few studies examined sensory processing (N = 5, 2.4%). We also have a miscellaneous category of studies that could not readily be assimilated into the a priori themes (N = 9, 4.2%), including an article exploring age-related differences in restrictive repetitive behaviors, as well as case study accounts.

Table 2.

A Priori Research Themes, With the Number of Older Age Autism Articles Coded Into Each Theme

| Theme | Frequency | % of total | % Exclude irrelevant |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Healtha | 17 | 8.0 | 11.8 |

| Genetics/Molecular | 16 | 7.5 | 11.1 |

| Reviewsb | 16 | 7.5 | 11.1 |

| Cognition | 15 | 7.1 | 10.4 |

| Autism characteristics/Traits | 11 | 5.2 | 7.6 |

| Mental Health | 10 | 4.7 | 6.9 |

| The Brain | 10 | 4.7 | 6.9 |

| Diagnosis/Prevalence | 9 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

| Miscellaneous | 9 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

| Support Needs | 9 | 4.2 | 6.3 |

| Quality of Life | 8 | 3.8 | 5.6 |

| Letter to the Editor | 6 | 2.8 | 4.2 |

| Sensory Processing | 5 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| Physical Health | 3 | 1.4 | 2.1 |

| Irrelevant | 68 | 32.1 | — |

Note: Total unique articles n = 212 (of which 145 identified by stringent search and 67 added by searching reference lists and other articles known to the authors). Total unique articles excluding Irrelevant n = 144. “The Brain” covers imaging and anatomical studies. “Genetics/Molecular” covers genetics, animal models, and fundamental science studies. “Autism Characteristics/Traits” covers trait-based studies, for example, outcomes/experiences in the broad autism phenotype.

Articles that include both mental and physical health.

We included all reviews here, which may overlap with other categories (i.e., a review of sensory processing would go here, rather than in the sensory processing category).

Our study identified a number of first-person accounts and community-member advocacy writings (e.g., Michael, 2016; see Supplementary Material for citation details), which we coded into the Letter to the Editor section (N = 6, 2.8%). We also identified a number of qualitative articles; however, rather than list these as a discrete category (with diverse coverage), we listed them in the relevant category by topic (e.g., Hickey et al., 2018 is listed under support services; see Supplementary Material for citation details). Finally, we did have a large irrelevant category, which included articles with no clear reference to autism in older age, such as articles related to advanced parental age and autism, criminal justice and mental health, and non-autistic older adult health and cognition (N = 68, 32.1%). Please see Supplementary Material S4 for a full list of the articles within each category of Table 2.

A note on keywords

Our search demonstrated how hard it is to specifically locate research articles on autism and aging. As indicated above, our initial search strategy included a large number of false positives that were clearly irrelevant. We refined the search strategy to try and remove some of those false positives, yet still a large number of irrelevant articles were retrieved. We examined the use of keywords in the 145 unique article abstracts returned by the stringent search that were categorized as relevant. A total of 60 abstracts did not have keywords indexed by the search engine. The remaining 85 used a wide range of keywords.

There were nine unique references to autism: “Autism Spectrum Disorder(s),” “Autistic Spectrum Disorder,” and “ASD” (n = 48); “Autism” (n = 25); “Broad Autism Phenotype” or “BAP” (n = 12); “Autism traits” (n = 3); “neurodevelopmental disorder” (n = 3); and “autistic identity” (n = 1). Eighteen unique age-related terms were used. The most common were “aging” or “ageing” (n = 43); “older adult(s)” and “old(er) age” (n = 19); “adult(s)” and “adulthood” (n = 29); and “elderly” (n = 10). The remaining eight terms were keywords used in only one article, for example, “geriatric psychiatry,” “late diagnosis,” “aged,” and “age trends.” The final three terms were not older-age specific, for example, “adolescence” and “early life.”

Discussion

The present study sought to identify the trends in research with older autistic participants. First, we found that almost four times as many articles were published in the nine years since 2012, compared with all the years preceding 2012. Second, and consistent with this, the rate of publications on older autistic people has sharply increased since 2012. Despite this encouraging increase, autistic children are still the focus of the majority of research articles, with older age research accounting for less than 1% of all publications over the past decade.

Our categorization of the autism aging abstracts returned by our review suggests that the focus of research thus far has been on factors about the autistic person, and less about their context or wider needs. For example, the majority of studies focused on socio-cognitive factors,11 physical12 or mental health13,14 conditions, brain imaging,15 and genetics.16 QOL has been identified as an important outcome for autistic people17; and we identified a number of studies that focused on QOL in older adults.18,19 For reasons of space, we are unable to explore more thoroughly the content of the included studies, and we direct interested readers to a recent review, which comprehensively examined the characteristics of samples used in older autism research and explored the areas of research covered (which are consistent with what we present here; Tse et al., 2021).20

A final interesting finding was the scant number of articles taking a dimensional or trait-wise approach with samples of older people.21–29 Given the accumulating evidence that autistic traits are continuously distributed in the population30–32 and share genetic influences with diagnosed autism,33 extending dimensional research approaches into older age could offer promising insights. Those who endorse higher autistic traits show similar difficulties to diagnosed autistic adults in understanding social situations28 and mental health.34 Indeed, in the general population, elevated autistic traits at age 45 are associated with poorer health and faster aging (even controlling for sex, childhood IQ, and childhood socio-economic status [SES]).35

Given the difficulties of diagnosing autism in the elderly36 and likely underdiagnosis in older adults, research with high-trait individuals may help with testing supports or interventions for older, diagnosed autistic people. Of course, any such interventions would need to be co-designed through participatory autism research methods.37

Research agenda

From our survey of the literature, there was little consideration, if any, of the practicalities that older autistic people face. For example, what should accommodation (e.g., residential care) look like for older autistic people?38 Given the often-precarious living arrangements of autistic people,39 this is a pressing concern. Moreover, studies with younger samples have identified difficulties in forming social networks40; this is also a vital question for older autistic people, given the risk of isolation in old age generally. Finally, very few (N = 8) of the identified articles focused on older autistic people with co-occurring intellectual disability.41–46

While some topics salient to the autism community (physical and mental health) are well represented, based on our search results, the following areas are in need of more study:

Autism and intellectual disability

QOL

Support needs and support preferences

Sensory processing

Studies that utilize longitudinal methods to examine age-related change

Therefore, it is imperative that autism researchers engage with older autistic people (i.e., consultation and co-production) to identity topics for research that could improve their lives.

Recommendations to the field

Clearly, there are many pressing and open research questions remaining for this underresearched group. We suggest that, in addition to ongoing research in the areas we identified, autism researchers consult with older autistic people to identify the research areas important to them.

Our search highlighted the relative difficulty of identifying articles on autism and old age, from keywords, titles, and abstracts. Search terms such as “older” and “senior” bring up a large number of false positives (e.g., “older children,” “senior manager”); trying to remove these was difficult and time-consuming. Even with our stringent search strategy, there were still abstracts that did not focus on autism or aging. This is potentially problematic for researchers interested wanting to gather research literature on autism in old age.

The use of a bespoke keyword for autism research articles addressing older adult issues could help identify this literature more clearly. Drawing on findings in market research, utilizing unique keywords with low online search indexing can increase the ease of identifying relevant materials and reduces the number of false search results.47 We therefore propose that the autistic community, stakeholders, and researchers could be consulted on the creation of a new indexing keyword that could be used in future research publications. The creation of this keyword could be a very useful way to clearly mark articles that focus specifically on samples of older (age 50+ years) autistic people.

We are not suggesting that the creation and use of this keyword would replace other strategies to identify relevant literature, as this would be inappropriate. Rather, we suggest that authors who use this keyword would necessarily have their work identified by a search strategy that uses this keyword. At present, it is not inconceivable that relevant material slips through the net when combining broader keywords that have high online search indexing (e.g., aging/older age, autism/ASD) in more complex search terms. Indeed, this can be seen from the diversity of search terms used in the abstracts we reviewed. Thus, the implementation of a unique keyword would be a useful aid to identifying older age autism research for members of the autistic community, relevant stakeholders, and researchers.

Strengths and limitations

Ours is the first study, as far as we are aware, to examine how the publication rate of autism research with older autistic people has changed over time. We developed our second search iteratively and applied a more stringent search strategy, to maximize the number of relevant articles and minimize the number of false positives. Moreover, the a priori set of research themes was reasonably robust—all the themes captured at least one study and enabled us to provide an overview of the current topics of research attention.

There are several caveats to our approach. First, we set out to ascertain the trends in aging research according to our criteria, and we did not intend to conduct a systematic review. Thus, we only examined the abstracts for information about each study with older autistic adults. As not every study reported the participant age, it is uncertain how relevant every abstract was to autism in old age. Second, a large number of studies could not be accommodated within our coding framework.

Many of these addressed very “niche” research questions, and we wanted to avoid a long list of categories with single articles. Future studies taking the present approach could attempt to refine the coding framework used here. Our search strategy did not explicitly include terms related to intellectual and/or learning disability (ID/LD). Thus, our count may underestimate the research literature on older autistic people with co-occurring ID or LD (see Tse et al.'s 202120 report on the characteristics of samples of older autistic people, which includes 16 studies with participants with ID; and Maguire et al., 202148 for a systematic review of autism and ID studies).

Additionally, despite a comprehensive search strategy, a large number of articles were manually added to the final older age total by the authors as they were not captured by the three databases. Finally, our methodology was based on the review conducted by Mukaetova-Ladinska et al. and was intended to be a broad overview of the literature, rather than systematic. We sought to identify if any changes could be detected since that often-cited article, using a similar search strategy. While not deeply exploring every article (as a systematic review would), we sought to identify trends by examining abstracts only.

Our results are consistent with other reviews, namely that there is a marked underrepresentation of older autistic people in autism research publications; however, we provide the novel finding that there is a small but consistently increasing trend for research with this group. Related to this, we did not examine whether the focus of the study was on aging, or whether it simply included older autistic people among the participants. Thus, although we have examined the trends in articles based on our searches for autism and older age, we have not specifically tracked trends in research which has as its primary focus the aging autistic population.

Conclusions

We found that there is still a dearth of autism research focused on older autistic people. What does exist focuses mainly on cross-sectional intraindividual factors (such as cognition, brain structure/function, and genetics). We make the case that autism researchers exploring older age ought to focus on areas such as QOL and support needs (among others) and that active engagement with stakeholders (i.e., older autistic people) is essential. Additionally, studies that utilize longitudinal designs to examine age-related change are vital.

Given the difficulty in identifying research on autism in later life, we propose that a new unique keyword could be created and then included in their articles when reporting on research with older autistic people. This would help demarcate and raise the profile of the small but steadily growing literature on autism in old age.

Supplementary Material

Authorship Confirmation Statement

All authors designed the search strategy. D.M. and G.R.S. performed all searches and tabulated the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the article. All co-authors have reviewed and approved the article before submission. The article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Ethical Statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study because there were no animal or human participants.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Information

The author(s) did not receive any funding for this study.

Supplementary Material

A previous version of this article was titled “The Rising Tide of ‘Gerontautism’” and proposed a keyword term “gerontautism”. In response to community feedback after initial publication, the authors updated the title and removed the keyword suggestion. Revised wording throughout the article is indicated in italic text.

We selected 50 years here because it has been reported that cognitive aging can be observed at this age in several domains.49

We did this for each of the age band searches. However, we only thematically coded the results for the older age group, as this was an aim of the article.

References

- 1. Mukaetova-Ladinska EB, Perry E, Baron M, Povey C, Group AAW. Ageing in people with autistic spectrum disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(2):109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wright SD, Wright CA, D'Astous V, Wadsworth AM. Autism aging. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;40(3):322–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Happé F, Charlton RA. Aging in autism spectrum disorders: A mini-review. Gerontology. 2012;58(1):70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robison JE. Autism prevalence and outcomes in older adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(3):370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sonido M, Arnold S, Higgins J, Hwang YIJ. Autism in later life: What is known and what is needed? Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2020;7:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 6. U.S. Census Bureau. No Title. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Selected Age Groups by Sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to Jul 1 2019. Published 2020. www.census.gov (last accessed February 11, 2021).

- 7. Office for National Statistics. No Title. Overview of the UK population: January 2021. Published 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk (last accessed February 11, 2021).

- 8. Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lai M-C, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lever AG, Geurts HM. Age-related differences in cognition across the adult lifespan in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2016;9(6):666–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hand BN, Angell AM, Harris L, Carpenter LA. Prevalence of physical and mental health conditions in Medicare-enrolled, autistic older adults. Autism. 2020;24(3):755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uljarević M, Hedley D, Rose-Foley K, et al. Anxiety and depression from adolescence to old age in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;50(9):3155–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lever AG, Geurts HM. Psychiatric co-occurring symptoms and disorders in young, middle-aged, and older adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(6):1916–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bathelt J, Koolschijn PC, Geurts HM. Age-variant and age-invariant features of functional brain organization in middle-aged and older autistic adults. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verhoeven WMA, Tuerlings J, van Ravenswaay-Arts CMA, Boermans JAJ, Tuinier S. Chromosomal abnormalities in clinical psychiatry: A report of two older patients. Eur J Psychiatry. 2007;21(3):207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burgess AF, Gutstein SE. Quality of life for people with autism: Raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2007;12(2):80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Heijst BFC, Geurts HM. Quality of life in autism across the lifespan: A meta-analysis. Autism. 2015;19(2):158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mason D, Mackintosh J, McConachie H, Rodgers J, Finch T, Parr JR. Quality of life for older autistic people: The impact of mental health difficulties. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;63:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tse WS, Lei J, Crabtree J, Mandy W, Stott J. Characteristics of older autistic adults: a systematic review of literature. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stewart GR, Corbett A, Ballard C, et al. Sleep problems and mental health difficulties in older adults who endorse high autistic traits. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020;77:101633. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caselli RJ, Langlais BT, Dueck AC, Locke DEC, Woodruff BK. Subjective cognitive impairment and the broad autism phenotype. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32(4):284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lever AG, Geurts HM. Is older age associated with higher self-and other-rated ASD characteristics? J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(6):2038–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stewart GR, Corbett A, Ballard C, et al. The mental and physical health of older adults with a genetic predisposition for autism. Autism Res. 2020;13(4):641–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Geurts HM, Stek M, Comijs H. Autism characteristics in older adults with depressive disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(2):161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stewart GR, Charlton RA, Wallace GL. Aging with elevated autistic traits: Cognitive functioning among older adults with the broad autism phenotype. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2018;54:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stewart GR, Corbett A, Ballard C, et al. The mental and physical health profiles of older adults who endorse elevated autistic traits. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76(9):1726–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart GR, Wallace GL, Cottam M, Charlton RA. Theory of mind performance in younger and older adults with elevated autistic traits. Autism Res. 2020;13(5):751–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wallace GL, Budgett J, Charlton RA. Aging and autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from the broad autism phenotype. Autism Res. 2016;9(12):1294–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoekstra RA, Bartels M, Verweij CJH, Boomsma DI. Heritability of autistic traits in the general population. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colvert E, Tick B, McEwen F, et al. Heritability of autism spectrum disorder in a UK population-based twin sample. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):415–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tick B, Bolton P, Happé F, Rutter M, Rijsdijk F. Heritability of autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of twin studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(5):585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bralten J, Van Hulzen KJ, Martens MB, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and autistic traits share genetics and biology. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(5):1205–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stewart GR, Corbett A, Ballard C, et al. The mental and physical health profiles of older adults who endorse elevated autistic traits. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;76(9):1726–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mason D, Ronald A, Ambler A, et al. Autistic traits are associated with faster pace of aging: Evidence from the Dunedin study at age 45. Autism Res. 2021;14(8):1684–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Niekerk MEH, Groen W, Vissers CTWM, van Driel-de Jong D, Kan CC, Oude Voshaar RC. Diagnosing autism spectrum disorders in elderly people. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(5):700–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nicolaidis C, Raymaker D, Kapp SK, et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism. 2019;23(8):2007–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crompton CJ, Michael C, Dawson M, Fletcher-Watson S. Residential care for older autistic adults: Insights from three multiexpert summits. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(2):121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mason D, Capp SJ, Stewart GR, et al. A meta-analysis of outcome studies of autistic adults: Quantifying effect size, quality, and meta-regression. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;51(9):3165–3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mazurek M. Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2014;18(3):223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kats D, Payne L, Parlier M, Piven J. Prevalence of selected clinical problems in older adults with autism and intellectual disability. J Neurodev Disord. 2013;5(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Rubenstein E. The physical and mental health of middle aged and older adults on the autism spectrum and the impact of intellectual disability. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;63:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gilmore D, Harris L, Longo A, Hand BN. Health status of Medicare-enrolled autistic older adults with and without co-occurring intellectual disability: An analysis of inpatient and institutional outpatient medical claims. Autism. 2021;25(1):266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Totsika V, Felce D, Kerr M, Hastings RP. Behavior problems, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life for older adults with intellectual disability with and without autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(10):1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheehan R, Hassiotis A, Walters K, Osborn D, Strydom A, Horsfall L. Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tromans S, Kinney M, Chester V, et al. Priority concerns for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(6):e128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang S, Pancras J, Song YA. Broad or exact? Search Ad matching decisions with keyword specificity and position. Decis Support Syst. 2021;143:113491. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maguire E, Mulryan N, Sheerin F, McCallion P, McCarron M. Autism spectrum disorder in older adults with intellectual disability: a scoping review. Ir J Psychol Med. 2021;1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roestorf A, Bowler DM, Deserno MK, et al. “Older Adults with ASD: The Consequences of Aging.” Insights from a series of special interest group meetings held at the International Society for Autism Research 2016–2017. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;63:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.