The B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) became the dominant strain in the United States by early July 2021.1 More highly infectious than its ancestral predecessor, the Delta variant rapidly spread in August 2021, causing a surge of infections and deaths in the setting of an under-vaccinated US population and raising particular concern for the vaccine ineligible pediatric population. In the setting of mitigation measures (primarily masking), kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) schools have previously been demonstrably safe, having limited within-school transmission, which is the fundamental metric of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19)–related school safety. However, these data originate from ancestral variants with lower levels of infectiousness than the Delta variant. We examined within-school transmission during emergence of the Delta variant in 20 North Carolina school districts during summer 2021 instruction.

Methods

The study occurred from June 14, 2021, to August 13, 2021, in K–12 districts in North Carolina that offered in-person summer school instruction and year-round schools. Districts followed the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services StrongSchoolsNC Toolkit.2 Briefly, distancing of at least 3 ft was recommended, but not required, and the state mask mandate for K–12 settings was in effect during this study period. Although reduced distancing was allowed, quarantine was required for close contacts of cases, defined by North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services as any person within 6 ft of a case for 15 minutes or longer, cumulatively, within a 24-hour period.2 Districts reported on schools and numbers of students and staff attending in-person summer school instruction. Districts also reported aggregate, deidentified data, including weekly numbers of student and staff infections, numbers of student and staff quarantines due to within-school exposure, and sources of infection (primary [community-acquired] versus secondary [within-school acquired]) adjudicated by local health departments in partnership with school staff. We obtained publicly available data on percent of eligible residents (12 years of age and older) who were fully vaccinated (have received second dose of a 2-dose series or single dose of a single-dose series) from each county with a participating district, as of August 1, 2021, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).3 We analyzed these data using descriptive statistics and graphically displayed primary and secondary cases per week with an overlay of estimated percentage of B1.167.2 variant per CDC Health and Human Services Region 4 data,1 which includes North Carolina. We then calculated 2 measures to estimate the amount of spread within-schools. First, we calculated the community-acquired to within-school-acquired infection ratio by dividing the number of primary infections by the number of secondary infections to estimate the number of community-acquired infections that result in a within-school transmission event; second, the estimated secondary attack was calculated by dividing the total number of within-school infections by the estimated number of exposed, approximated by those quarantined for within-school exposure. Data collection and analysis were performed under the ABC Science Collaborative of North Carolina Plan A protocol (Pro00108073), deemed exempt by Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Results

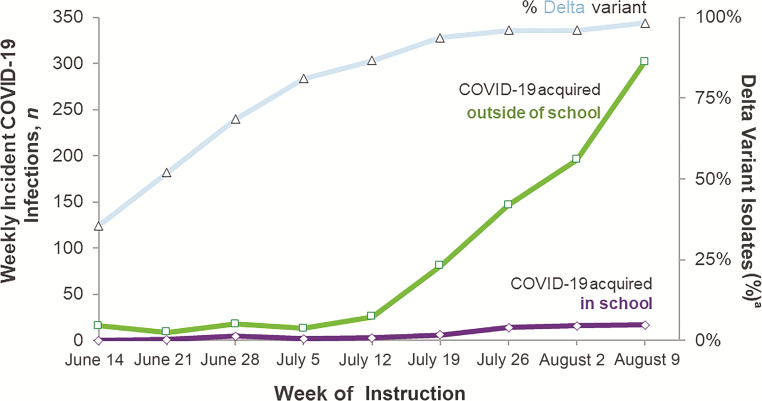

Twenty school districts participated and submitted data from 783 schools, 59 561 students, and 11 854 staff who attended in-person instruction. All participating districts implemented universal masking of students and staff during the study period, regardless of vaccination status. No schools had to close because of COVID-19 cases during the study period. Percentage of fully vaccinated residents in the 19 counties containing the 20 participating districts ranged from 32% to 64.7%, with an average of 47% (SD of 7.8%) of eligible residents vaccinated as of August 1, 2021. Primary infections, secondary infections, and quarantine occurrences in students and staff are reported in Table 1 as total and by district size (small: <5000 students; medium: 5000–15 000 students; large: >15 000 students). Total primary and secondary infections by week are in Fig 1. The community-acquired-to-within-school-acquired infection ratio was ∼12.4 (808:64). The estimated secondary attack rate was 2.6% (64 secondary infections per 2431 quarantined close contacts).

TABLE 1.

Primary Infections, Secondary Infections, and Quarantine Occurrences in Students and Staff

| Total Districts, n | Total Children, n | Total Staff, n | COVID-19 Transmission | Quarantine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student Primary, n | Student Secondary, n | Staff Primary, n | Staff Secondary, n | Student | Staff | ||||

| Total districts | 20 | 59 561 | 11 854 | 619 | 60 | 189 | 4 | 2032 | 399 |

| District size | |||||||||

| Small | 6 | 4071 | 484 | 26 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 84 | 7 |

| Medium | 7 | 9915 | 1599 | 47 | 14 | 21 | 1 | 248 | 31 |

| Large | 7 | 45 575 | 9771 | 546 | 45 | 159 | 3 | 1700 | 361 |

FIGURE 1.

COVID-19 Infections among summer school staff and students. COVID-19 infections among >70 000 North Carolina summer school staff and students, displayed according to weekly cases acquired in school versus cases acquired outside of school, with an overlay of weekly proportion of SARS-CoV-2 isolates in the region consistent with the B.167.2 (Delta) variant. a Percentage of Delta variant in Department of Health and Human Services region 4, which includes Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

Discussion

This report demonstrates that even with exponentially rising community cases at the start of the Delta variant surge, schools that implemented universal masking retained low within-school transmission. When considering the safety of in-person schooling, we (and others)4–8 have shown the rates of within-school transmission to be comparable across school district and have advocated for within-school transmission rates to be the primary metric of interest. The findings of this study are notable because the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 is more highly infectious than ancestral strains, with an estimated reproductive number for Delta of ∼8 (range estimated to be between 5 and 9), in contrast to ∼2–3 for ancestral strain.9,10 This means that in the community, on average, 1 person infected with the Delta variant secondarily infects 8 other people. In contrast, in schools implementing universal masking, it would take 13 attendees who acquired COVID-19 outside of school to infect 1 person inside schools.

Although extremely encouraging that secondary transmission in schools with universal masking remains lower in schools than in the community, the secondary attack rate observed in the setting of the Delta variant (2.6%) is slightly higher than what we observed when ancestral and Alpha strains were predominant in North Carolina (∼1%),7,8,11 likely reflecting the more infectious nature of Delta. Consequently, these data, coupled with previous reports of widespread school-based infection from a single unmasked index case in places like California,12 also reinforce the importance of vaccine uptake among those eligible, strict adherence to masking, and avoidance of pandemic fatigue. Although our study does not allow a comparison from the masked to unmasked setting, recent studies from schools without an early mask mandate during July through August 2021 had 3.5 times the odds of school-associated COVID-19 outbreaks compared with those with mask requirements at the start of instruction.13 These data and our experience over the last year highlight the need for and creation of alternative protocols during times of vulnerability, such as lunch, extracurricular activities, and recess, when adherence to masking is more difficult.

Notably, these data were collected at a time of decreased overall school density. Most districts reported that ∼10% to 35% of the total students in-person during the spring of 2021 attended summer instruction. However, total number of schools open for instruction was also substantially reduced; therefore, although school building density was often lower than during the traditional school year, the density within the school buildings was typically >50% of usual capacity seen in full-time instruction prepandemic. Furthermore, districts often had an increased adult-to-child ratio during summer school for academic purposes, but the number of people within each classroom (and classroom density) was consistent with a typical school year. These factors lead to several important ways that transmission was likely to be reduced in the summer compared with the fall: (1) recess was less crowded; (2) extracurricular activities that have had substantial amounts of associated spread in earlier work were nearly nonexistent; (3) adherence to masking was likely increased because of increased adult-to-child ratio, allowing for close monitoring; and (4) lunch was usually eaten outdoors (because of weather) and with greater distancing indoors while unmasked (because of reduced school building density). These 4 factors (Recess, Extracurricular activities, Adherence, and Lunch; or “REAL”) are critical to consider because in the higher density fall instruction, they become less feasible. We anticipate that we will see greater transmission of the Delta variant in the upcoming school year compared with last school year and compared with summer school, even in districts with universal masking. Areas of future research this fall will include assessing the impact of vaccination with the details of mask policies and mask adherence.

Limitations to our study include that data were voluntarily reported, which may introduce selection bias toward districts that are more transparent and adherent to mitigation measures, and that we relied on CDC estimates of Delta variant prevalence rather than genetic sequencing of our cohort. Additionally, vaccination status was not being routinely tracked by school districts at the time of the study; consequently, the proportion of summer school students and vaccinated students is not known. We found that elementary schools had the highest total number of infections, followed by high schools, then middle schools, but these data are difficult to interpret since numbers of students were reported on a district level, as opposed to a school level; as a result, comparing transmission between various school levels is not possible. Finally, consistent with previous real-world data reports, we did not test every exposed person. Despite these limitations, the risk of within-school transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the classroom environment remains small in the wake of Delta, provided that universal masking is practiced with high fidelity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Erin Campbell, who provided manuscript revision and submission. We acknowledge Ibukunoluwa C. Kalu, Kathleen A. McGann, Michael Smith, Ganga Moorthy, and Alan Brookhart, as well Moira Inkelas and Sabrina Butteris, for their continued collaboration. We also acknowledge Jesse Hickerson, Vroselyn Benjamin, Brenda Franklin-Goode, and Wayne Pennachi for their efforts in ABC program and data management. Finally, we acknowledge and express our gratitude to the school districts, administrators, and school nurses who worked diligently to collect and report these data in an effort to keep the children in their districts safe.

Glossary

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- COVID-19

coronavirus 2019

- K–12

kindergarten through 12th grade

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Footnotes

Dr Boutzoukas conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Zimmerman and Dr Benjamin, Jr conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Funded in part by the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics Underserved Populations (U24 MD016258) Return to School Program (National Institutes of Health [NIH] Agreement No’s. 1 OT2 HD107559-01, OT2 HD107558-01, and 1OT2HD108103-01); the Trial Innovation Network (5U24TR001608-06 Title: Center for Innovative Trials in Children and Adults [TRIDENT]), which is an innovative collaboration addressing critical roadblocks in clinical research and accelerating the translation of novel interventions into life-saving therapies; and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) contract (HHSN275201000003I) for the Pediatric Trials Network (principal investigator, Daniel Benjamin). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the NIH. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker: variant proportions. Available at: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#circulatingVariants. Accessed September 3, 2021

- 2. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services . StrongSchoolsNC Public Health Toolkit (K-12): interim guidance. 2021. Available at: https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/media/164/open. Accessed September 3, 2021

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States, county. Available at: https://data.cdc.gov/Vaccinations/COVID-19-Vaccinations-in-the- United-States-County/8xkx-amqh. Accessed September 27, 2021

- 4. Dawson P, Worrell MC, Malone S, et al. ; CDC COVID-19 Surge Laboratory Group . Pilot investigation of SARS-CoV-2 secondary transmission in kindergarten through grade 12 schools implementing mitigation strategies — St. Louis County and City of Springfield, Missouri, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(12):449–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hershow RB, Wu K, Lewis NM, et al. Low SARS-CoV-2 transmission in elementary schools - Salt Lake County, Utah, December 3, 2020-January 31, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(12): 442–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falk A, Benda A, Falk P, Steffen S, Wallace Z, Høeg TB. COVID-19 cases and transmission in 17 K–12 schools — Wood County, Wisconsin, August 31–November 29, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4): 136–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zimmerman KO, Akinboyo IC, Brookhart MA, et al. ; ABC Science Collaborative . Incidence and secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infections in schools. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4):e2020048090l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zimmerman KO, Brookhart MA, Kalu IC, et al. ; ABC Science Collaborative . Community SARS-CoV-2 surge and within-school transmission. Pediatrics. 2021;148(4): e2021052686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mandavilli A. C.D.C. internal report calls Delta variant as contagious as chickenpox. The New York Times. July 30, 2021. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/30/health/covid-cdc-delta-masks.html. Accessed September 3, 2021

- 10. Billah MA, Miah MM, Khan MN. Reproductive number of coronavirus: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on global level evidence. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benjamin DKJr, Zimmerman KO. Final report for NC school districts and charters in Plan A. 2021. Available at: https://abcsciencecollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ABCs- Final-Report-June-2021.06-esig-DB-KZ-6- 29-21.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2021

- 12. Lam-Hine T, McCurdy SA, Santora L, et al. Outbreak associated with SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant in an elementary school — Marin County, California, May–June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(35):1214–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jehn M, McCullough JM, Dale AP, et al. Association between K–12 school mask policies and school-associated COVID-19 outbreaks — Maricopa and Pima Counties, Arizona, July–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70: 1372–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]