Abstract

The vrl locus is preferentially associated with virulent isolates of the ovine footrot pathogen, Dichelobacter nodosus. The complete nucleotide sequence of this 27.1-kb region has now been determined. The data reveal that the locus has a G+C content much higher than the rest of the D. nodosus chromosome and contains 22 open reading frames (ORFs) encoding products including a putative adenine-specific methylase, two potential DEAH ATP-dependent helicases, and two products with sequence similarity to a bacteriophage resistance system. These ORFs are all in the same orientation, and most are either overlapping or separated by only a few nucleotides, suggesting that they comprise an operon and are translationally coupled. Expression vector studies have led to the identification of proteins that correspond to many of these ORFs. These data, in combination with evidence of insertion of vrl into the 3′ end of an ssrA gene, are consistent with the hypothesis that the vrl locus was derived from the insertion of a bacteriophage or plasmid into the D. nodosus genome.

The acquisition of large segments of DNA by pathogenic bacteria has now become a paradigm of molecular pathogenesis. In some cases, these segments of DNA play a direct role in the virulence of the organism and have become known as pathogenicity islands (18). Comparison of virulent and benign strains of the ovine footrot pathogen, Dichelobacter nodosus, has led to the identification of two genomic regions, vap and vrl, that appear to be preferentially associated with more virulent isolates of D. nodosus (22, 37). In the absence of genetic tools for the analysis and manipulation of D. nodosus, these regions have been cloned and characterized in Escherichia coli.

The vap region is present in multiple copies in the chromosome of the reference virulent strain of D. nodosus, strain A198 (22). vap regions 1 and 3 comprise an 11.8-kb locus that appears to be derived from the integration of a bacteriophage or a plasmid carrying an integrase gene (5, 7, 11). This locus is present at one or more copies in 98% of virulent strains, but is also present in a significant number (28%) of benign strains (37).

By contrast, the vrl region appears to be more specifically associated with D. nodosus isolates of greater virulence. In all, 87% of virulent isolates carry vrl while only 6% of benign strains hybridize with probes derived from this locus (37). The vrl region is present in only one copy on the strain A198 chromosome (22). Delineation of the locus (19) has demonstrated that it consists of a contiguous 27-kb region of virulence-associated DNA. A bacteriophage-like attachment site was identified at the left end of the vrl region, within the 3′ end of an ssrA gene encoding a potential regulatory 10Sa RNA molecule. This result suggested that vrl may have been acquired by the site-specific integration of a mobile genetic element (19).

Use of DNA probes from within the vrl and vap loci has allowed the classification of D. nodosus isolates into three major categories; category 1 isolates possess both vrl and vap sequences, category 2 isolates have vap but not vrl, while category 3 isolates do not contain either vap or vrl sequences (22). A fourth category has recently been described (37). In addition to carrying vap sequences, these category 4 isolates hybridize to a probe derived from the right end of vrl (pJIR314B) but do not hybridize to a probe derived from the central vrl region (pJIR313) (22, 37).

In this paper, we present the complete nucleotide sequence and protein profile analysis of the vrl locus from D. nodosus strain A198. Analysis of these data suggests that the vrl genes are in an operon-like arrangement and were acquired from an exogenous source. In addition, we define the deletions in the vrl locus that are present in category 4 isolates of D. nodosus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The E. coli strains used were derivatives of DH5α (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.), K38 (38), or DH12S (Life Technologies) and were grown as previously described (19). The complete vrl region was originally isolated on four overlapping λGEM12 derivatives, and most of the region was subcloned with pUC18 (48). Expression vector constructs were made with the T7 vectors pGEM-7Zf (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.), pTZ18R (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), pBluescript II-KS (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), or pWSK29 (45). Category 4 D. nodosus isolates were obtained from Wagga Wagga, New South Wales [WW904018(4B)], Hamilton, Victoria (HA274, HA276 and HA320), Sydney, New South Wales (A1015), Ballan, New South Wales (CS94), Albany, Western Australia (AC293), and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Orgonisation, Parkville, Victoria (J690), and were grown as previously described (19).

Molecular methods.

Unless otherwise stated, all molecular techniques were carried out as previously described (39). Plasmid DNA was purified with the Magic Minipreps DNA purification system (Promega). DNA amplification was performed by PCR with Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Castle Hill, Australia) in the supplied reaction buffer for 35 cycles consisting of 1 min at 94°C (DNA denaturation), 1 min at 55°C (primer annealing), and 1 min/kb at 72°C (DNA synthesis). PCR products were purified for nucleotide sequencing with the Magic PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega) followed by two 70% ethanol washes.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

Previous studies had led to the detailed sequence analysis of only the ends of the vrl locus (19). To determine the nucleotide sequence of the entire vrl region, the primary λ clones used to delineate the vrl locus (19) were subcloned into plasmid vectors. Nucleotide sequence determinations were carried out with these subclones and exonuclease III-generated deletion derivatives. Oligonucleotide primers were designed to generate nucleotide sequence data from regions not covered by these plasmids. The vrl region was completely sequenced on both strands across all restriction sites. Oligonucleotides for sequencing were synthesized with a 392 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Double-stranded plasmid DNA or PCR products from category 4 isolates were sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method either with the T7Sequencing kit (Pharmacia) and [α-35S]dATP (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) or with PRISM Ready Reaction cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems) and an Applied Biosystems 373A DNA sequencer. Sequences were edited and compiled with the ESEE (9) and Sequencher (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, Mich.) programs. Nucleotide and protein sequences were analyzed with various programs in the Australian National Genomic Information System (University of Sydney) and were compared to sequences in the databases by using the BLAST (2), FASTA (32), and SBASE (34) programs. Searches for E. coli ς70-like promoter sequences were performed with the algorithm of Mulligan et al. (31).

Expression of vrl proteins.

Overlapping fragments from the vrl region were subcloned into vectors containing the T7 promoter. The resultant plasmids were used to transform an E. coli strain (K38 or DH12S) containing plasmid pGP1-2 (42). Selective [α-35S]methionine labelling of plasmid-encoded proteins was carried out with the T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system (42). Labelled cell extracts were resuspended in sample buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% [wt/vol] glycerol, 5% [wt/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, 65 μg of bromophenol blue per ml) and boiled for 5 min before being subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (24). The sizes of proteins were determined by comparison to proteins of known size in the LMW electrophoresis calibration kit (14.4 to 94 kDa) (Pharmacia) or in the SeeBlue prestained standards (4 to 250 kDa) (Novex, San Diego, Calif.). After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and subjected to autoradiography. Tricine-SDS-PAGE was performed as previously described (40).

Western blots.

Rabbit antisera (RAS350 and RAS351) were raised against whole cells of D. nodosus A198. Sheep antisera (SAS328 and SAS650) were obtained from sheep, experimentally infected with strain A198, with severe lesions in three or four feet for a number of weeks prior to sampling. These antisera were kindly provided by John Egerton and Craig Kristo (Department of Animal Health, University of Sydney). Antisera were adsorbed with E. coli K38 cell extracts prior to use at 1/50 (sheep antisera) or 1/100 (rabbit) dilutions in Western blots. Immunoblot experiments were carried out essentially as previously described (39).

Dot blot hybridizations.

Dot blot hybridizations of genomic DNA samples were carried out as described previously (22). Preparation of digoxigenin-labelled DNA probes, DNA hybridization, and probe detection were performed with the DIG DNA labelling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) as specified by the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete nucleotide sequence of the vrl region from D. nodosus A198 has been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession no. U20247.

RESULTS

Complete nucleotide sequence analysis of the vrl region.

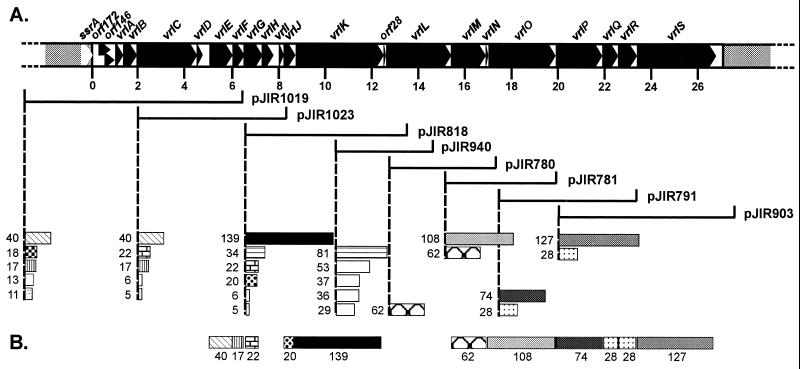

Previous studies involved the detailed sequence analysis of only the ends of the vrl locus (19). We now report the 21,835 bp of nucleotide sequence which bridges the sequences previously published from the left and right ends of vrl (19). A pictorial representation of the nucleotide sequence data is presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of nucleotide sequence and protein expression data. (A) The location of each sequenced ORF within the 27-kb vrl locus is indicated by the arrows. Overlapping constructs within this region which, with respect to the T7 promoter, were in the correct orientation for the expression of the known vrl genes are shown. Protein bands identified as vrl encoded from the expression vector studies are represented as bars below the plasmid on which they are encoded. Proteins which appear to be breakdown products or the result of internal initiation within an ORF are shown as unfilled bars. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons. Where the size of the protein band cannot be determined but the band corresponds to a sequenced ORF, the size predicted from the sequence is used. (B) The vrl-encoded protein bands that correlate with the sequence data are aligned with the respective vrl genes shown in panel A.

The complete vrl locus consists of 27,101 bp with a G+C content of 59.7%, considerably higher than the value of 45% estimated for the remainder of the D. nodosus chromosome (20). The differential G+C content of the region at least in part explains the disproportionately large number of restriction sites for the restriction enzymes EagI (CGGCCG) and StuI (AGGCCT). There are 15 EagI sites and 7 StuI sites within vrl, whereas there are only an additional 6 EagI and 5 StuI sites in the remaining 1.5 Mb of the strain A198 genome, most of which reside in the three rRNA gene regions (25).

Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequence of vrl revealed the presence of 19 open reading frames (ORFs), designated vrlA through vrlS, and 3 additional ORFs that lack identifiable ribosome binding sites (RBS), ORF172, ORF146 (19), and ORF28 (Fig. 1). The deduced properties of each ORF are indicated in Table 1. All 22 ORFs are present on the same strand and are arranged in an operon-like manner. In general, the start codon or putative RBS of one ORF either overlaps or is located very close to the stop codon of the preceding ORF. With the exception of noncoding regions at the left and right ends of vrl, only two significant regions of apparently noncoding sequence were found, a 245-bp sequence between vrlD and vrlE and a 126-bp sequence between vrlH and vrlI. Searches for potential promoter sequences identified only a putative ς70-like promoter sequence within the vrlH-vrlI intergenic region. We previously identified a large region of dyad symmetry at the left end of vrl and a putative transcription terminator within the right end of vrl (19). In addition to these structures, a region of imperfect dyad symmetry, which could form a stem-loop structure with a ΔG of −15.6 kcal/mol, was identified at the 3′ end of vrlM. This repeat was not followed by a run of T residues and so did not appear to be a classical rho-independent transcription terminator. However, its position at the extreme 3′ end of vrlM and the fact that it sequestered part of the putative RBS of the next ORF, vrlN, suggested that it may play a role in the regulation of translation.

TABLE 1.

Properties of vrl ORFs

| ORF | Nucleotide length (bp) | G+C content (%) | Mr of putative protein product | Predicted pI | Sequence similarity and motifs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf172 | 516 | 62.0 | 18,895 | 7.1 | None |

| orf146 | 438 | 61.2 | 16,163 | 5.2 | None |

| vrlA | 354 | 60.2 | 13,403 | 5.1 | None |

| vrlB | 584 | 63.6 | 21,625 | 11.9 | None |

| vrlC | 2,625 | 63.9 | 96,268 | 4.8 | Extracellular protein motif Asp box motifs |

| vrlD | 255 | 65.5 | 9,415 | 6.8 | Synechocystis sp. hypothetical protein |

| vrlE | 954 | 63.7 | 36,217 | 9.4 | None |

| vrlF | 519 | 66.1 | 19,030 | 4.7 | None |

| vrlG | 795 | 64.2 | 30,430 | 8.6 | Glutaminase domain of glutamine amidotransferases |

| vrlH | 555 | 61.5 | 21,003 | 7.8 | Synechocystis sp. hypothetical protein |

| vrlI | 201 | 54.4 | 8,003 | 5.0 | Helix-turn-helix domain, B. subtilis phage SPP1 hypothetical protein |

| vrlJ | 513 | 56.8 | 18,583 | 5.1 | ATP binding motif |

| vrlK | 3,729 | 60.7 | 139,544 | 5.6 | PglY from S. coelicolor |

| orf28 | 84 | 52.9 | 3,083 | 4.5 | None |

| vrlL | 2,790 | 50.1 | 106,474 | 6.7 | Adenine-specific methyltransferases |

| vrlM | 1,488 | 50.5 | 55,482 | 5.2 | None |

| vrlN | 99 | 45.5 | 3,789 | 11.2 | None |

| vrlO | 2,898 | 61.7 | 108,179 | 5.5 | ATP binding motif, DEAH ATP-dependent helicases |

| vrlP | 2,001 | 58.1 | 74,406 | 5.3 | PglZ from S. coelicolor |

| vrlQ | 753 | 57.8 | 28,271 | 9.0 | None |

| vrlR | 846 | 49.9 | 32,411 | 6.2 | Chloroplast proteins |

| vrlS | 3,390 | 53.9 | 126,795 | 5.4 | ATP binding motif DEAH ATP-dependent helicases |

Comparative analysis of the vrl ORFs.

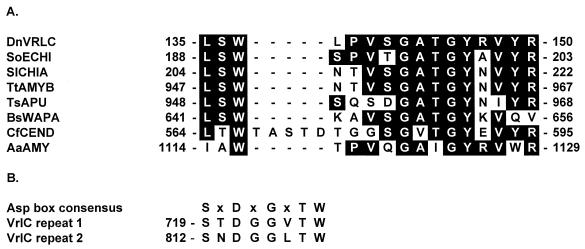

The predicted amino acid sequences of the protein products of each of the 22 ORFs identified within the vrl sequence were used to search known protein databases and were examined for various structural motifs. None of the putative vrl-encoded proteins have significant regions of hydrophobicity or potential signal sequences, suggesting that all of these proteins are cytoplasmic. The VrlC protein, while showing no significant similarity to known proteins, does contain two motif sequences present in other proteins. The first motif was identified by database searches and consists of 16 amino acids which exhibit significant similarity to amino acid sequences located within a number of extracellular proteins, primarily depolymerases with insoluble substrates, including chitinases, endocellulases, amylases, and pullulanases (Fig. 2A). This motif is found in the fibronectin type III motifs of many of these proteins, but neither VrlC nor the Bacillus subtilis wall-associated protein, WapA, has the rest of that motif. VrlC also has two Asp box motifs (Fig. 2B) which are found in a range of viral and bacterial sialidases, although usually in four or more copies (36). The lack of a signal sequence for VrlC, irrespective of which of several putative vrlC start codons is used, suggests that it is unlikely that VrlC has an extracellular or periplasmic location.

FIG. 2.

Conserved amino acid motifs associated with VrlC. (A) An aligned motif present in a number of extracellular proteins, many of which are associated with the depolymerization of insoluble substrates. Conserved amino acids are boxed. DnVRLC, D. nodosus VrlC; SoECHI, Streptomyces olivaceoviridis exochitinase (6); SICHA, S. lividans chitinase (30); TtAMYB, Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes pullulanase (28); TsAPU, T. saccharolyticum amylopullulanase (35); BsWAPA, Bacillus subtilis WapA (15); CfCEND, Cellulomonas fimi endoglucanase D (29); AaAMY, Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius amylase (23). (B) Asp box motif present in sialidases from a number of sources (36). The numbers refer to the position of the first residue with respect to the N-terminal amino acids.

The 265-amino-acid VrlG protein shows significant similarity (24% identity, 40% similarity) to the N-terminal region of glutamine-fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferases from a variety of organisms (13, 41, 43). The majority of these enzymes are approximately 600 amino acids long but are separated into two distinct domains: an N-terminal glutaminase domain, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of glutamine to glutamate and an ammonium ion, and a C-terminal synthetase domain, which catalyzes the amination of the substrate (21). The VrlG protein aligns precisely along its entire length with the glutaminase domain of these proteins; both the catalytic N-terminal cysteine residue and Arg26, which is important in coupling (21), are conserved.

VrlI is a 67-amino-acid protein which has 25.4% identity to hypothetical protein 37.3 encoded within the replication region of the B. subtilis bacteriophage SPP1 (1, 33). Although protein 37.3 has 33% identity to the Xis protein encoded by pSAM2 from Streptomyces ambofaciens (1), VrlI has only 16.4% identity to this recombination protein. VrlI contains a putative helix-turn-helix domain (6-LTVDDICKYLNVSNETVYKWIE-27), which aligns with a similar sequence in the SPP1 protein and the helix-turn-helix domains of a number of known DNA binding proteins, including several activators of transcription. A putative ς70 promoter exists immediately upstream of vrlI, and it is possible that if the VrlI protein is a regulatory protein, its production is required for transcription of the rest of the vrl operon. The stop codon of vrlI overlaps the RBS of vrlJ, which encodes a protein with an ATP- and GTP-binding motif.

The 1,243-amino-acid putative product of vrlK has 15.5% amino acid sequence identity to the 1,294-amino-acid Streptomyces coelicolor PglY protein, which is involved in bacteriophage φC31 resistance (3). Like PglY, VrlK has a putative amino-terminal ATP- and GTP-binding motif (GNYGTGKS) (44). The phase-variable Pgl resistance system involves two proteins, PglY and PglZ, and it has been postulated that this system mediates resistance via a novel restriction-modification mechanism (3). While the level of similarity between VrlK and PglY is not high, it may be significant, since VrlP has 22% amino acid sequence identity to the product of the pglZ gene (3). However, VrlP is only two-thirds the size of PglZ. Although pglY and pglZ are juxtaposed in S. coelicolor, their putative vrl homologues, vrlK and vrlP, are separated by over 7 kb (Fig. 1). Interestingly, many of the intervening ORFs, such as ORF28, vrlL, vrlM, and vrlN, have a much lower G+C content than do the surrounding genes (Table 1), suggesting that these genes may have been inserted into the vrl region and that vrlK and vrlP were once much closer.

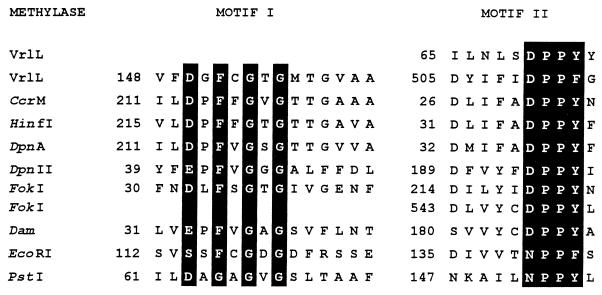

VrlL has amino acid sequence similarity to several adenine-specific methyltransferases, particularly in the regions which encompass the conserved motifs I and II (Fig. 3) (26, 47). Motif I appears to be the cofactor binding site and is shared by all methyltransferases that use S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor (47). Motif II appears to be the catalytic domain and is common to N6-adenine and N4-cytosine methyltransferases. The order in which the motifs occur can vary and forms the basis of the classification of methyltransferases into subclasses. In VrlL, the distance between motifs I and II is 343 amino acids, which is much greater than that identified in the methyltransferases, consistent with the observation that VrlL is larger than the known methyltransferases. An alternative motif II (Fig. 3) was also identified at positions 65 to 74 in VrlL, but this motif is less closely related to the consensus sequence.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of methyltransferases motifs. Putative N6-adenine methyltransferase motifs I and II from VrlL and the methyltransferases indicated (26, 47) are aligned. More conserved amino acids are boxed. The numbers refer to the position of the first residue with respect to the N-terminal amino acids.

Although the target sequence specificity of a methyltransferase cannot be determined from its amino acid sequence, the methyltransferases which were identified by the database searches as having the highest degree of similarity to VrlL were all N6-adenine methyltransferases. These enzymes included M.CerM from Caulobacter crescentus (target Gm6ANTC) (49), M.DpnII from Streptococcus pneumoniae (Gm6ATC) (12), and M.HinfI from Haemophilus influenzae (Gm6ANTC) (10). Based on the presence of the conserved motifs and the similarity to these methyltransferases, it is postulated that VrlL encodes an N6-adenine methyltransferase.

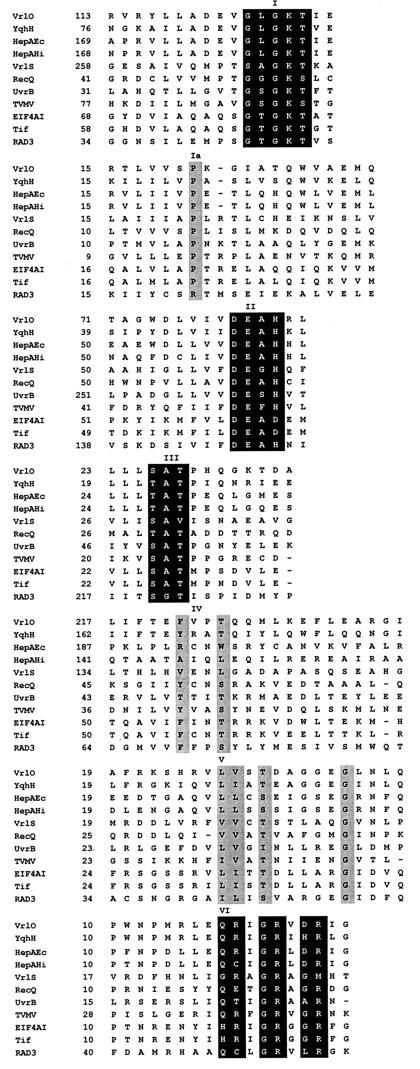

Searches with the VrlO amino acid sequence revealed that it contained the conserved regions (Fig. 4) that are typical of members of the helicase superfamily II (16, 17). Both DNA and RNA helicases are included in this family. VrlO was most closely related to the hypothetical helicases YqhH from B. subtilis (GenBank accession no. D84432), HepA from H. influenzae (14), and the HepA protein from E. coli (8). Similarity between helicase proteins is restricted to seven regions, which have been designated I, Ia, II, III, IV, V, and VI (17). Each of these short segments was found in VrlO and was arranged spatially within the sequence in a manner that was consistent with the other members of the DEAH ATP-dependent helicase family (Fig. 4). Residues in regions I, II, and III are very highly conserved within the diverse members of the group, which includes proteins encoded by bacterial, viral, and eukaryotic genomes (27). These residues were more highly conserved within VrlO than within the final vrl-encoded gene product, VrlS (previously designated ORF1130) (Fig. 1 and 4), which we previously reported as having similarity to the same helicase family (19). Significant similarity (34% identity over 481 amino acids) was found between VrlS and the antiviral SKI2 protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (46), a helicase that appears to block the translation of viral mRNA molecules.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of VrlO with conserved regions of the DEAH ATP-dependent helicase family. The conserved helicase regions I, Ia, and II to VI are as defined previously (17). More highly conserved amino acids are shown in the black boxes, and less highly conserved regions are shown in the grey boxes. The numbers refer to the positions of the first residue with respect to the N-terminal amino acid. YqhH, hypothetical helicase gene from Bacillus subtilis; HepAEc, hypothetical helicase gene from E. coli; HepAHi, hypothetical helicase gene from Haemophilus influenzae; VrlS, from the right end of the vrl locus; RecQ and UvrB, E. coli recombination proteins; TVMV, CIP protein of tobacco vein mottling virus; EIF4AI, human translation initiation factor 4A; Tif and RAD3, translation initiation factor Tif2 and helicase RAD3, respectively, from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Identification of proteins encoded by the vrl region.

Concomitant with the nucleotide sequencing of the vrl locus, T7 expression vector studies were carried out to identify the proteins encoded by the vrl region. The entire 27-kb vrl locus was divided into eight overlapping segments, which were subsequently cloned in both orientations with respect to the T7 promoter. Initial plasmids were constructed in either pGEM7Zf, pBluescript KS II, or pTZ18U. However, recombinants which encompassed the first 8.35 kb of the vrl region could not be constructed by using any of these high-copy-number vectors. These fragments were cloned by using the low-copy-number vector pWSK29, suggesting that they encoded gene products which were lethal when overexpressed. For T7 expression studies, all plasmids were maintained in E. coli K38 (pGP1-2), except the pWSK29 derivatives, which were not stably maintained in this background. However, E. coli DH12S strains which contained the pWSK29-derived plasmids were able to be stably transformed with pGP1-2. Following induction of the T7 promoter at 42°C, proteins expressed from the various recombinant plasmids were specifically radiolabelled and analyzed by SDS-PAGE or Tricine-SDS-PAGE. Proteins encoded by the vrl locus were identified as bands which were present in the induced lanes of test strains but were absent from the host and vector control lanes.

Analysis of the results revealed that with one exception, no proteins were detected in strains derived from plasmids in which the T7 promoter was oriented in the opposite orientation to the known vrl genes (data not shown). The one exception was a plasmid which flanked the left junction of the vrl region and expressed a 24-kDa protein corresponding to an ORF within the non-virulence-associated DNA upstream of the ssrA gene (3a). These results correlated with the nucleotide sequence data, which indicated that none of the identified vrl structural genes were transcribed in the anti-vrl orientation.

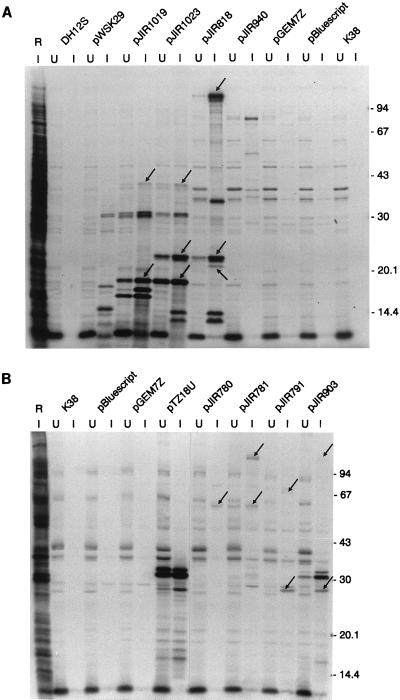

By contrast, many induced protein bands were observed (Fig. 5) in strains carrying the overlapping plasmids in which the T7 promoter was oriented in the same direction as the known vrl genes. By comparison of the protein profiles and the sequence data, it was possible to correlate the genes encoding the various proteins, assuming that several of the smaller protein bands were degradation products or were derived from internal initiation. These data are summarized in Fig. 1. Analysis of the 8.35-kb region at the left end of the vrl locus, which was present in the overlapping pWSK29-derived plasmids, pJIR1019 and pJIR1023, indicated that several genes within this region were not expressed in this system. However, the results suggest that the 40- and 17-kDa bands produced from pJIR1019 and pJIR1023 may represent the products of vrlE and vrlF, although it is possible that either or both bands are the result of internal initiation within the large vrlC coding region. The 22-kDa protein expressed by pJIR1023 and the overlapping plasmid pJIR818 corresponded to the expected size of VrlH, while either the 5- or 6-kDa proteins observed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (data not shown) could be the product of VrlI.

FIG. 5.

Identification of vrl-encoded proteins. Whole-cell extracts of host (K38 and DH12S) and vector (pWSK29, pBluescript, pGEM7Zf, and pTZ18U) control strains, as well as host strains carrying the vrl plasmids indicated, were induced and labelled. All strains carried pGP1-2, which encodes the T7 RNA polymerase. Autoradiographs of the relevant SDS-PAGE profiles are shown. For each strain, samples of extracts from cultures where the expression of the T7 polymerase was uninduced (U) and induced (I) are included. The vrl-encoded protein bands that correlate with the sequence data are indicated by the arrows. Standards are indicated in kilodaltons. A host cell extract to which rifampin was not added is included (lane R). All of the vrl plasmids were in the same orientation with respect to the T7 promoter located on the vector. These overlapping plasmids consisted of pJIR1019, a pWSK29 derivative carrying a 9.4-kb insert from outside the vrl locus to vrl position 6.5; pJIR1023, a pWSK29 derivative carrying the kb 2.0 to 8.4 region of vrl; pJIR818, a pTZ18U derivative carrying the kb 6.6 to 13.6 region of vrl; pJIR940, a pTZ18U derivative carrying the kb 10.5 to 14.7 region of vrl; pJIR780, a pTZ18U derivative carrying the kb 12.8 to 17.4 region of vrl; pJIR781, a pTZ18U derivative carrying the kb 15.2 to 20 region of vrl; pJIR791, a pGEM7Zf derivative carrying the kb 17.5 to 23.4 region of vrl; and pJIR903, a pTZ18U derivative carrying a 7.6-kb fragment from vrl position 20.1 to outside the vrl locus (Fig. 1).

The remaining approximately 19 kb of vrl was contained within overlapping fragments in high-copy-number vectors (Fig. 1). pJIR818 expressed a 20-kDa protein that corresponded to the size of VrlJ (18.6 kDa), a large protein band (>94 kDa) that corresponded to the expected 140-kDa VrlK product, and a 34-kDa band that was probably a truncated derivative of VrlL (Fig. 5). In accordance with the sequence data, another truncated derivative (81 kDa) of VrlL appeared to be encoded by the next plasmid, pJIR940. Unfortunately, it was not possible to construct a plasmid in which a complete vrlL gene was expressed from a T7 promoter. The next two sequential vrl plasmids, pJIR780 and pJIR781 (Fig. 1), encoded a 62-kDa band that appeared to correspond to VrlM (55 kDa). In addition, pJIR781 encoded a larger band (>94 kDa) that corresponded to the expected 108-kDa VrlO protein. A 74-kDa band which was the same size as the predicted VrlP product was detected in extracts derived from pJIR791, along with a 28-kDa band. This band appeared to represent both VrlQ (28 kDa) and VrlR (32 kDa). Finally, as previously reported (19), a large pJIR903-encoded protein band corresponding to VrlS (ORF1130) also was observed.

Therefore, we have detected protein bands with molecular masses which correspond to the predicted sizes encoded by at least 11 of the 22 ORFs identified by sequence analysis. Products could not be definitively assigned to orf172, orf146, vrlA, vrlB, vrlC, vrlD, vrlG, orf28, vrlL, or vrlN, although putative truncated products originating from vrlL were observed. Four of these ORFs are contained within segments of DNA that could not be maintained in high-copy-number plasmids; perhaps the use of pWSK29 has reduced the expression of some proteins to undetectable levels. In addition, both ORF28 and vrlN putatively encode very small proteins which may not have been detectable under these conditions.

Western blots with antisera raised against whole D. nodosus cells do not detect vrl-encoded proteins.

If the vrl region encoded novel proteins that were exposed on the D. nodosus cell surface or secreted from the cell, these proteins may play a potential role in the development of a vaccine against footrot. To detect any such antigens, Western blotting was performed with rabbit or sheep antisera raised against whole cells of D. nodosus A198. Cell extracts of separate induced E. coli strains carrying the T7 expression plasmids in the vrl orientation were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. The pWSK29 derivative pJIR1311 was used as a positive control, since it contained the fimbrial subunit gene fimA under the control of the T7 promoter. Although bands corresponding to the FimA subunit could be detected in blots with each of the four antisera used, no vrl-encoded immunoreactive protein bands were observed (data not shown). Although not conclusive, these results suggest that the vrl region does not encode major antigens that are recognized during experimental infections or vaccination experiments.

Category 4 isolates have large deletions within the vrl locus.

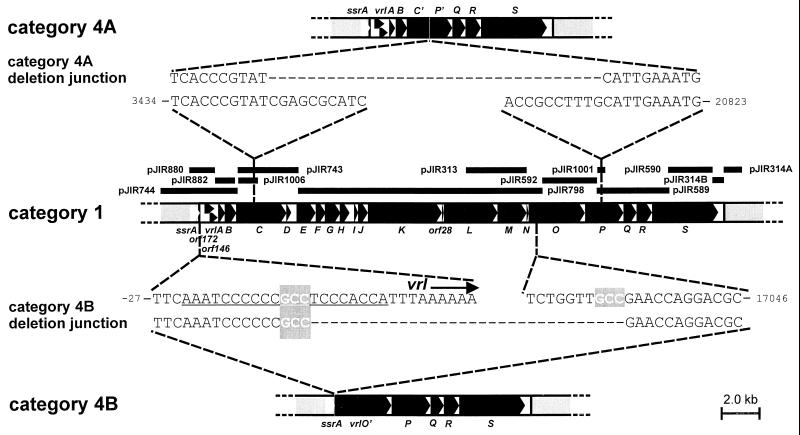

Category 4 D. nodosus isolates were originally defined in gene probe studies as isolates which hybridized with the vrl-derived plasmid pJIR314B but not with the vrl-derived plasmid pJIR313 (22, 37). Because pJIR314B was from the right end of vrl and pJIR313 was from a central portion of vrl, it was assumed that these isolates contained internal vrl deletions. The availability of the complete sequence of vrl from strain A198 now allows us to more precisely define the rearrangements that have occurred in these strains. Genomic DNA from each of eight category 4 isolates was subjected to dot blot analysis with digoxigenin-labelled probes covering the entire vrl region (Fig. 6). These analyses indicated that the isolates could be classified into two subcategories, 4A and 4B, based on the type of deletion present.

FIG. 6.

Category 4 deletion endpoints. The genetic maps of the vrl regions from category 1 (strain A198), category 4A, and category 4B strains are shown. vrl genes are indicated by the black arrows. Gene probes used in the delineation of each deletion are represented by the black bars and are labelled with plasmid names. The sequence of the deletion junction is shown for both category 4A and category 4B isolates in comparison with the corresponding sequence from strain A198.

The category 4A isolates [HA274, A1015, HA276, and WW904018(4B)] contained a deletion encompassing probes pJIR798, pJIR592, and pJIR313, with deletion endpoints within the 1.8-kb insert of pJIR1006 and the 0.8-kb insert of pJIR1001. To determine the precise ends of these deletions, genomic DNA from the category 4A isolates was subjected to PCR analysis with primer 1294 (5′-CGAGCTGGGCAATCTCAATGTG-3′) within vrlC and primer 1293 (5′-GTAGTGGTCGGTCAGTCAAGTG-3′) within vrlP. These PCRs amplified a 1.0-kb fragment. Sequencing across the junction point of the deletion revealed that a precise deletion of 17,370 bp had occurred within all four isolates, extending from vrl coordinate 3443 within vrlC to coordinate 20813 within vrlP (Fig. 6).

The category 4B isolates (HA320, CS94, AC293, and J640) contained a deletion of vrl sequences encompassing probes pJIR882, pJIR743, and pJIR313, with deletion endpoints within the 1.5-kb insert of pJIR880 and the 0.4-kb region between the pJIR313 probe and the right end of pJIR798. PCR was again used to determine the precise deletion present in category 4B isolates. By using primer 1129 (5′-ACCGTAAGCGACATTAACACAG-3′) located within the ssrA gene and a second primer, 1087 (5′-GGGTTTGACCGAATCCAGGG-3′), within vrlO, a PCR product of 0.7 kb was amplified from each of these isolates. Sequencing of the PCR products revealed that an identical deletion had occurred in each of the four category 4B isolates. This deletion was different from that which had occurred in the category 4A isolates and encompassed the 17,044 bp between vrl coordinates −10 and +17034 (Fig. 6). One end of this deletion resides within attL, at the left end of vrl, and the other end of the deletion extends some 100 bp into the putative helicase gene, vrlO. While no extensive sequence similarity was found between the deletion ends of either category 4A or 4B isolates, we note that the deletion ends of the category 4B isolates were surrounded by the trinucleotide GCC whereas only a single copy of this trinucleotide was found at the junction point of the deletion in category 4B isolates (Fig. 6). Isolate AC293 had an additional 8-bp deletion within the 5′-end-truncated vrlO sequence. The deleted region was also flanked by the trinucleotide GCC, with only one GCC repeat remaining in the deleted version (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The vrl locus is preferentially associated with more virulent isolates of D. nodosus. The lack of tools for the genetic manipulation of this organism has inhibited any analysis of the relationship between this locus and virulence, preventing its definitive designation as a pathogenicity island. However, the determination of the complete sequence of the vrl locus provides many insights into its origin and its potential effect on the virulence of D. nodosus isolates.

Most of the 27.1-kb vrl region contains putative ORFs, with only 1,043 bp of the 27.1-kb being apparently noncoding, over half of which is either 5′ of ORF172 or 3′ of vrlS (Fig. 1). All 22 ORFs that were identified are oriented in the same direction and are closely spaced. Together with the apparent lack of rho-independent terminators within the vrl sequence, these data suggest the existence of a large vrl-encoded operon. This hypothesis is supported by the detection of putative products from 15 vrl-encoded ORFs in T7 expression studies. The start codon or RBS of many of the vrl genes overlaps the stop codon of the preceding gene, suggesting not only that there is an operon structure but also that the expression of these genes may be translationally coupled.

The evidence suggests that the vrl region does not encode antigens which are recognized in experimental infections or vaccination experiments. None of the vrl genes encode potential proteins with characteristic signal sequences, suggesting that these products are not secreted; the lack of extensive hydrophobic domains argues against a transmembrane location. In addition, no proteins expressed in the T7 expression system were recognized by either rabbit or sheep sera raised against D. nodosus. While not all of the putative products of the vrl genes were identified in T7 expression studies, it appears unlikely that vrl-encoded proteins will be exposed to the immune system.

Several lines of evidence point to the conclusion that the vrl locus has arisen from the horizontal transfer of exogenous DNA. First, as previously reported (19), at the very left end of vrl is a putative bacteriophage-like attachment site, attL, which is located within the 3′ end of an ssrA gene that encodes a 10Sa or tmRNA molecule. This finding suggests that the introduction of the vrl region into D. nodosus occurred as the result of a site-specific recombination event. Second, the G+C content of the vrl region is significantly higher than that of the D. nodosus chromosome or, indeed, that of cloned D. nodosus genes. In addition, the arrangement of sequences within the locus, as reflected by the large number of EagI and StuI sites, is significantly different from the rest of the D. nodosus genome. The third piece of evidence for the exogenous origin of this region is the nature of the genes within the region. Many of these genes appear to encode functions often associated with extrachromosomal elements. For example, DNA methylases and helicases are often carried on plasmids or bacteriophages, and while the S. coelicolor Pgl system is not known to be carried on a phage or plasmid, it is possible that a bacteriophage resistance mechanism provides protection from superinfection by a vrl-encoding phage. While a bacteriophage origin of the vrl region is one possibility, the lack of genes encoding potential packaging and phage coat structural proteins argues against the direct integration of a solely vrl-encoding phage. However, as previously noted (19), there is no att site at the right end of vrl to correspond to the proposed attL at the left end, nor is there a vast difference in the G+C content between vrl and non-vrl sequence at the right end. These observations suggest that the right end of the virulence-related sequence does not correlate with the end of the integrated element and that the vrl region may have been introduced as part of a larger genetic element. Many of the characteristics of the vrl locus noted here are common among known pathogenicity islands, including the association with virulent isolates, the differential G+C content of the region, and its association with tRNA or ssrA genes as well as the putative attL site (18).

Both of the D. nodosus virulence-associated regions, vap (5, 7, 11) and vrl, appear to have arisen from similar site-specific insertion events, resulting in the integration of a sequence of probable phage or plasmid origin. Examination of over 800 D. nodosus isolates has failed to detect a single strain which carries the vrl locus but not the vap region (37). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the vap-encoded integrase is required for the integration of the vrl locus into the D. nodosus chromosome.

Category 4 isolates comprise approximately 1.3% of all isolates screened with vrl- and vap-specific gene probes and 3.7% of D. nodosus isolates which hybridize to pJIR314B (37). The results reported here indicate that these isolates carry large deletions within the vrl locus and can be subdivided into two further categories, 4A and 4B, based on the type of deletion which has occurred. Category 4A isolates contain a precise deletion removing 17.4 kb from within vrlC to within vrlP, while category 4B isolates carry a precise deletion of 17.0 kb from within the putative attL site located immediately upstream of the vrl region to within vrlO. The category 4B deletion extends into the non-virulence-associated ssrA gene located upstream of vrl, altering the 3′ extension of the precursor form of the regulatory 10Sa RNA and potentially linking the expression of the remaining vrl genes with that of ssrA by removing the large hairpin loop structure at the left end of vrl. The isolates within each of these categories were obtained from geographically diverse origins within Australia, and while this does not necessarily rule out the possibility of a clonal relationship, it suggests that these precise deletions have occurred independently within a number of D. nodosus isolates. These data, in combination with the presence of a GCC trinucleotide at the junction of the category 4B deletions, provide circumstantial evidence that a site-specific recombination event has led to the deletions present in the category 4 isolates. The virulence of the four category 4A isolates examined here ranges from benign to high intermediate (37), whereas three of the four category 4B isolates are classified as virulent and strain HA320 is classified as having low-level intermediate virulence. It is possible that there are some differences in virulence between category 4A and 4B isolates, although these isolates represent only a small sample size. These results may also indicate that at least the region deleted in the category 4B isolates is not essential for virulence.

Since vrl is preferentially, although not exclusively, associated with strains of D. nodosus with greater virulence, it is reasonable to assume that the vrl sequence is able to affect virulence either directly, by encoding a virulence factor, or indirectly, by regulating the expression of genes involved in D. nodosus pathogenesis. We have previously suggested that vrl could affect virulence because its integration site is located within the 3′ end of the upstream ssrA gene and directly affects the sequence of the 3′ extension encoded by the regulatory 10Sa RNA molecule (4, 19). The potential of the vrl region to encode a virulence factor or a factor which may enhance the virulence of a D. nodosus isolate remains unknown, since none of the vrl-encoded proteins have sequence similarity to known virulence factors. Obviously, any of the putative vrl-encoded products which do not have similarity to known proteins may potentially be directly involved in virulence. In addition, the VrlC motif that is present in a number of extracellular or wall-associated enzymes from other bacteria is suggestive of a functional domain, and while the function of sialidase Asp boxes is unknown, the presence of this motif in multiple copies in VrlC suggests that this motif has significance. The putative glutaminase activity of VrlG appears at odds with other proteins encoded in the vrl region, since it is suggestive of a nutritional role. The putative DNA binding function of VrlI may be related to regulation of other virulence genes. It is also possible to predict a potential virulence-enhancing property for a vrl-encoded phage resistance system, which may provide protection in vivo from D. nodosus-specific phages, which may or may not carry vrl genes. Unfortunately, classical reverse-genetics experiments to provide direct evidence for any of these possibilities must await the development of mechanisms for genetically manipulating this fastidious anaerobe.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pauline Howarth, Khim Hoe, and Vivien Vasic for expert technical assistance and John Egerton and Craig Kristo for generously providing the antisera. We also thank W. K. Yong, J. R. Egerton, I. Links, L. J. Depiazzi, and D. Stewart for providing the category 4 D. nodosus isolates.

This research was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council and the Australian Wool Research and Promotion Organisation (AWRAPO). A.S.H. was supported by Australian Woolgrowers and the Australian Government by a postgraduate scholarship from AWRAPO.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso J C, Lüder G, Stiege A C, Chai S, Weise F, Trautner T A. The complete nucleotide sequence and functional organization of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPP1. Gene. 1997;204:201–212. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedford D J, Laity C, Buttner M J. Two genes involved in the phase-variable φC31 resistance mechanism of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4681–4689. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4681-4689.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Billington, S. J., and J. I. Rood. Unpublished data.

- 4.Billington S J, Johnston J L, Rood J I. Virulence regions and virulence factors of the ovine footrot pathogen, Dichelobacter nodosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:147–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billington S J, Sinistaj M, Cheetham B F, Ayres A, Moses E K, Katz M E, Rood J I. Identification of a native Dichelobacter nodosus plasmid and implications for the evolution of the vap regions. Gene. 1996;172:111–116. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaak H, Schnellmann J, Walter S, Henrissat B, Schrempf H. Characteristics of an exochitinase from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis, its corresponding gene, putative protein domains and relationship to other chitinases. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:659–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloomfield G A, Whittle G, McDonaugh M B, Katz M E, Cheetham B F. Analysis of sequences flanking the vap regions of Dichelobacter nodosus: evidence for multiple integration events and a new genetic element. Microbiology. 1997;143:553–562. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bork P, Koonin E V. An expanding family of helicases within the “DEAD/H” superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:751–752. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabot E L, Beckenbeck A T. Simultaneous editing of multiple nucleic acid and protein sequences with ESEE. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:233–234. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandrasegaran S, Lunnen K D, Smith H O, Wilson G G. Cloning and sequencing the HinfI restriction and modification genes. Gene. 1988;70:387–392. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheetham B F, Tattersall D R, Bloomfield G A, Rood J I, Katz M E. Identification of a bacteriophage-related integrase gene in a vap region of the genome of D. nodosus. Gene. 1995;162:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00315-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Campa A G, Kale P, Sprinhorn S S, Lacks S A. Proteins encoded by the DpnII restriction gene cassette. Two methylases and an endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 1987;196:457–469. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutka-Malen S, Mazodier P, Badet B. Molecular cloning and overexpression of the glucosamine synthetase gene from Escherichia coli. Biochimie. 1988;70:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleishmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J C, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-L, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback T R, Hanna M C, Hguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae RD. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster S J. Molecular analysis of three major wall-associated proteins of Bacillus subtilis 168: evidence for processing of the product of a gene encoding a 258 kDa precursor two-domain ligand-binding protein. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:299–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicases: amino acid sequence comparisons and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V, Donchenko A P, Blinov V M. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4713–4730. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Mühldorfer I, Tschäpe H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haring V, Billington S J, Wright C L, Huggins A S, Katz M E, Rood J I. Delineation of the virulence related locus vrl of Dicheiobacter nodosus. Microbiology. 1995;141:2081–2091. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holdeman L V, Kelley R W, Moore W E C. Genus I. Bacteroides Castellani and Chalmers 1919, 959AL. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 604–631. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isupov M N, Obmolova G, Butterworth S, Badet-Denisot M-A, Badet B, Polikarpov I, Littlechild J A, Teplyakov A. Substrate binding is required for assembly of the active conformation of the catalytic site of Ntn amidotransferases: evidence from the 1.8 Å crystal structure of the glutaminase domain of glucosamine 6-phosphate synthase. Structure. 1996;4:801–810. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz M E, Howarth P M, Yong W K, Riffkin G G, Depiazzi L J, Rood J I. Identification of three gene regions associated with virulence in Dichelobacter nodosus, the causative agent of ovine footrot. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2117–2124. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-9-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koivula T T, Hemila H, Pakkanen R, Sibakov M, Palva I. Cloning and sequencing of a gene encoding acidophilic amylase from Bacillus acidocaldarius. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2399–2407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-10-2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Fontaine S, Rood J I. Physical and genetic map of the chromosome of Dichelobacter nodosus strain A198. Gene. 1997;184:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauster R, Kriebardis A, Guschlbauer W. The GATATC-modification enzyme EcoRV is closely related to the GATC-recognizing methyltransferases DpnII and dam from E. coli and phage T4. FEBS Lett. 1987;220:167–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis L K, Jenkins M E, Mount D W. Isolation of DNA damage-inducible promoters in Escherichia coli: regulation of polB (dinA), dinG, and dinH by LexA repressor. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3377–3385. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3377-3385.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matuschek M, Burchhardt G, Sahm K, Bahl H. Pullulanase of Thermoanaerobacterium thermosulfurigenes EM1 (Clostridium thermosulfurigenes): molecular analysis of the gene, composite structure of the enzyme, and a common model for its attachment to the cell surface. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3295–3302. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3295-3302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meinke A, Gilkes N R, Kilburn D G, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A. Cellulose-binding polypeptides from Cellulomonas fimi: endoglucanase D (CenD), a family A beta-1,4-glucanase. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1910–1918. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.1910-1918.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyashita K, Fujii T. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of a gene (chiA) for a chitinase from Streptomyces lividans 66. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1691–1698. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulligan M E, Hawley D K, Entriken R, McClure W R. Escherichia coli promoter sequences predict in vitro RNA polymerase selectivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:789–800. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part2.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedre X, Weise F, Chai S, Luder G, Alonso J C. Analysis of cis and trans acting elements required for the initiation of DNA replication in the Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SPP1. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:1324–1340. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pongor S, Hatsagi Z, Degtyarenko K, Fabian P, Skerl V, Hegyi H, Murvai J, Bevilacqua V. The SBASE protein domain library, release 3.0: a collection of annotated protein sequence segments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3610–3615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramesh M V, Podkovyrov S M, Lowe S E, Zeikus J G. Cloning and sequencing of the Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum B6A-RI apu gene and purification and characterization of the amylopullulase from Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:94–101. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.94-101.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roggentin P, Rothe B, Kaper J B, Galen J, Lawrisuk I, Vimr E R, Schauer R. Conserved sequences in bacterial and viral sialidases. Glycoconjugate J. 1989;6:349–353. doi: 10.1007/BF01047853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rood J I, Howarth P A, Haring V, Billington S J, Yong W K, Liu D, Palmer M A, Pitman D A, Links L, Stewart D A, Vaughan J A. Comparison of gene probe and conventional methods for the differentiation of ovine footrot isolates of Dichelobacter nodosus. Vet Microbiol. 1996;52:127–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russel M, Model P. Replacement of the ftp gene of Escherichia coli by an inactive gene cloned on a plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:1034–1039. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.3.1034-1039.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Surin B P, Downie J A. Characterization of the Rhizobium leguminosarum genes nodLMN involved in efficient host-specific nodulation. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:173–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker J E, Gay N J, Saraste M, Eberle A N. DNA sequence around the Escherichia coli unc operon. Completion of the sequence of a 17 kilobase segment containing asnA, oriC, unc, glmS and phoS. Biochem J. 1984;224:799–815. doi: 10.1042/bj2240799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of the ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Widner W R, Wickner R B. Evidence that the SKI antiviral system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae acts by blocking expression of viral mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4331–4341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willcock D F, Dryden D T F, Murray N E. A mutational analysis of the two motifs common to adenine methyltransferases. EMBO J. 1994;13:3902–3908. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zweiger G, Marczynski G, Shapiro L. A Caulobacter DNA methyltransferase that functions only in the predivisional cell. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:472–485. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]