Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular bacterium that elicits complex cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses in infected mice. The responses of CTL populations that differ in antigen specificity range in magnitude from large, dominant responses to small, subdominant responses. To test the hypothesis that dominant T-cell responses inhibit subdominant responses, we eliminated the two dominant epitopes of L. monocytogenes by anchor residue mutagenesis and measured the T-cell responses to the remaining subdominant epitopes. Surprisingly, the loss of dominant T-cell responses did not enhance subdominant responses. While mice immunized with bacteria lacking dominant epitopes developed L. monocytogenes-specific immunity, their ability to respond to dominant epitopes upon rechallenge with wild-type bacteria was markedly diminished. Recall responses in mice immunized with wild-type or epitope-deficient L. monocytogenes showed that antigen presentation during recall infection is sufficient for activating memory cells yet insufficient for optimal priming of naive T lymphocytes. Our findings suggest that T-cell priming to different epitopes during L. monocytogenes infection is not competitive. Rather, T-cell populations specific for different antigens but the same pathogen expand independently.

Antigen-processing pathways present pathogen-derived peptides at the infected cell surface to T lymphocytes (12, 21, 25). For complex pathogens, numerous antigens are degraded into peptides that are bound and presented to T cells by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules (24, 35). T cells specific for these peptides become activated and give rise to T-cell populations with effector functions (21). The number of T cells responding to different peptides is distinct, with some dominant peptides eliciting very large T-cell populations and other, subdominant peptides eliciting only small T-cell populations (37, 40). Various factors have been implicated as determinants of immunodominance. For example, the antigen-processing efficiency (31), the affinity of the peptide for the MHC molecule (11, 41), the rate of dissociation of the peptide from the MHC groove (4, 26, 43), the transport of the peptide into the endoplasmic reticulum (38), and finally the T-cell repertoire (10, 13, 53) have been suggested to determine the magnitude of the T-cell responses. A recent study of the T-cell responses to influenza virus peptides suggested that proteolytic generation of antigenic peptides plays a greater role in determining immunodominance than either the responding T-cell repertoire or the TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) transport of peptides (14). These investigators also found that T-cell responses to dominant peptides can suppress responses to subdominant peptides.

A preponderance of data suggests that dominant T-cell responses can suppress subdominant responses. For CD4 T-cell-mediated responses to a bacterial protein (32) and CD8 T-cell-mediated responses to viral antigens (14, 30, 33), elimination of dominant epitopes can promote T-cell responses to subdominant epitopes. Similarly, mice lacking an MHC class I allele that presents a dominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitope manifest T-cell responses to otherwise silent antigens (18). All of these studies, however, preceded the advent of accurate measurements of T-cell responses to infection (8, 28, 29, 49). The issue, however, of whether T-cell responses to one epitope can adversely affect T-cell responses to another epitope is of critical importance to vaccine design. It is clear that polyvalent vaccines targeting multiple antigens, perhaps even different pathogens, are desirable. If increasing the complexity of a vaccine diminishes T-cell responses to individual components, however, serial immunization with oligovalent vaccines may be superior.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive intracellular bacterium that causes severe disease in immunocompromised and pregnant individuals (19). L. monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular pathogen that multiplies within the cytoplasm of macrophages and hepatocytes and, upon infection of mice, induces a rapid and robust MHC class I-restricted CTL response (35). The antigens detected by murine CTLs include the virulence factors listeriolysin O (LLO) and metalloprotease (mpl) and the constitutively secreted murein hydrolase p60 (5, 37). The magnitude of the CTL response is distinct for each of the epitopes derived from these antigens: LLO 91-99 elicits a very large, dominant response, p60 217-225 elicits an intermediate response, and p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 elicit small, subdominant responses (6, 49). Remarkably, the magnitude of the T-cell response does not correlate with the prevalence of the antigen or the cognate epitopes (37).

In this study, we determined the influence in vivo of dominant T-cell responses to LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 on subdominant responses. To address this issue, we deleted the two dominant epitopes from L. monocytogenes by site-directed mutagenesis. We used ELISPOT assays of peptide-induced gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production to precisely quantify T-cell frequencies following infection with mutant strains. Our studies demonstrated that these two dominant T-cell responses do not detectably suppress subdominant T-cell responses. Interestingly, L. monocytogenes-immune mice have markedly diminished primary T-cell responses to dominant epitopes following reinfection. These findings have important implications for vaccine development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and cell lines.

BALB/c (H-2d) or CB6 [(BALB/c × C57BL/6)F1, H-2d × H-2b] mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) or Charles River Breeding Laboratories. J774 macrophage-like cells and P815 mastocytoma cells (both H-2d) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. CTL clones L12.3, L9.6, and WP11.12 were derived from L. monocytogenes-primed CB6 mice and maintained by weekly in vitro restimulation with infected J774 cells as previously described (44). Cells were cultured in RPMI medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, l-glutamine, HEPES (pH 7.5), β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml).

Bacterial strains and immunization of mice.

Wild-type L. monocytogenes 10403S was obtained from Daniel Portnoy (University of California, Berkeley). Mice were injected intravenously with various doses of wild-type or mutant L. monocytogenes resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline. For primary infection, the dose ranged from 1,000 to 5,000 bacteria per mouse. Recall responses were induced by intravenous inoculation with 105 bacteria.

Generation of L. monocytogenes strains lacking dominant H-2Kd-restricted CTL epitopes.

Amino acid 92 of LLO was mutated from tyrosine (an MHC class I H-2Kd anchor residue) to serine (a nonanchor residue) by the PCR overlap extension method. Two PCR products that covered bp −186 to 335 and bp 318 to 877 of the hly gene (27) were generated by use of Vent polymerase (New England BioLabs). One PCR product, of 521 bp, was generated with the sequences 5′-CCGGATCCGGCCCCCTCCTTTGATT-3′ and 5′-TCCATCTTTCGAACCTTTT-3′ as the primers; the other PCR fragment, of 559 bp, was generated with the sequences 5′-GAAAAGGTTCGAAAGATGGA-3′ and 5′-GGCTGCAGTAGTAACAGCTTTGCCG-3′ as primers. The external primers incorporated BamHI and PstI sites (indicated in bold) for cloning into the respective sites of thermosensitive plasmid pKSV7, and the underlined nucleotides represent the mutation. The mutation was then incorporated into the chromosome of L. monocytogenes 10403S by homologous recombination as described previously (9, 47, 50) to generate L. monocytogenes Ser92. The generation of L. monocytogenes Ser218 was described previously (50). A similar strategy was used to generate L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 from L. monocytogenes Ser92. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Extraction of LLO 91-99, p60 217-225, and p60 449-457 from L. monocytogenes-infected J774 cells and CTL assays.

CTL epitopes were isolated from L. monocytogenes-infected J774 cell pellets as described previously (34). Briefly, J774 cells were infected with the different strains of L. monocytogenes for 6 h, pelleted, extracted with 10 ml of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), Dounce homogenized, sonicated, and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 35 min. Supernatants were concentrated by lyophilization, resuspended in 2 ml of 0.1% TFA, and passed through a Centricon-10 membrane (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). The filtrate was fractionated by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), and fractions were lyophilized, resuspended in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline, and tested for LLO 91-99, p60 217-225, and p60 449-457 in a 4-h chromium release assay with P815 target cells and CTL clones L12.3, L9.6, and WP11.12, respectively, as previously described (44).

Western blot analysis of p60 and LLO production by wild-type and mutant L. monocytogenes strains.

The four L. monocytogenes strains were inoculated into brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and grown to the stationary phase. Culture supernatants were resuspended in equal volumes of 2× sample buffer (45) and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose, and p60 and LLO were detected with polyclonal antisera as described previously (52).

Quantitation of bacteria in spleens and livers of infected mice.

Groups of three BALB/c mice were infected with 2,000 bacteria (L. monocytogenes wild type, Ser92, Ser218, or Ser92/218). Livers and spleens were aseptically removed from mice 48 h later and homogenized by passage through a wire mesh, and dilutions were plated onto BHI plates. The number of bacteria per organ was calculated by accounting for dilution factors.

Quantification of IFN-γ-secreting T cells by the ELISPOT assay.

The number of IFN-γ-secreting T cells directed against H-2Kd-restricted Listeria epitopes was quantified by the ELISPOT assay as described previously (49). Briefly, 96-well nitrocellulose plates were coated with a rat anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody. Listeria-immune splenocytes from immunized mice were harvested either 7 days after primary infection or 6 days after reinfection. Splenocytes were incubated with peptide-coated or non-peptide-coated P815 cells in the presence of interleukin 2. After 24 to 28 h, cells were washed away and the specific production of IFN-γ was detected by development of the plates as described previously (28). The magnitude of the T-cell response was reported as the number of IFN-γ-secreting T cells per 100,000 splenocytes.

RESULTS

Generation of L. monocytogenes strains lacking immunodominant CTL epitopes.

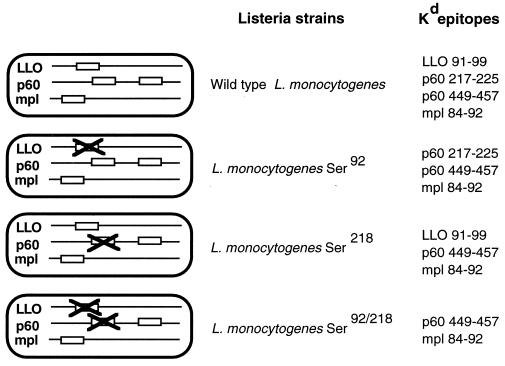

Previous studies of H-2Kd-restricted CTLs following L. monocytogenes infection demonstrated a response hierarchy: LLO 91-99 elicits large dominant responses, p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 elicit small subdominant T-cell populations, and p60 217-225 elicits intermediate responses (6, 49). To investigate the effect of dominant T-cell responses on subdominant responses, we eliminated the two dominant epitopes, LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225, from L. monocytogenes. Our strategy was to mutagenize the essential tyrosine in the P2 position of both epitopes into serine, thereby eliminating an essential anchor residue for binding to H-2Kd (15). Our approach was similar to that used by Bouwer and colleagues (2) to eliminate one L. monocytogenes epitope (LLO 91-99), except that they replaced the tyrosine residues with phenylalanine, which can function as an H-2Kd anchor residue (2). The tyrosine-to-serine mutations were incorporated into the chromosome of L. monocytogenes by homologous recombination, generating three new strains: L. monocytogenes Ser92, which lacks LLO 91-99; L. monocytogenes Ser218, which lacks p60 217-225; and, L. monocytogenes Ser92/218, which lacks both of the dominant CTL epitopes (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of wild-type and mutant L. monocytogenes strains. Three mutant strains of L. monocytogenes lacking either LLO 91-99 (Ser92), p60 217-225 (Ser218), or both dominant epitopes (Ser92/218) were generated by mutations in the codon for the P2 tyrosine residue, an essential anchor for binding by H-2Kd class I molecules. The L. monocytogenes-derived H-2Kd-restricted peptides that can be presented by infected cells are listed to the right of each strain.

Antigen secretion and epitope generation from L. monocytogenes epitope mutants.

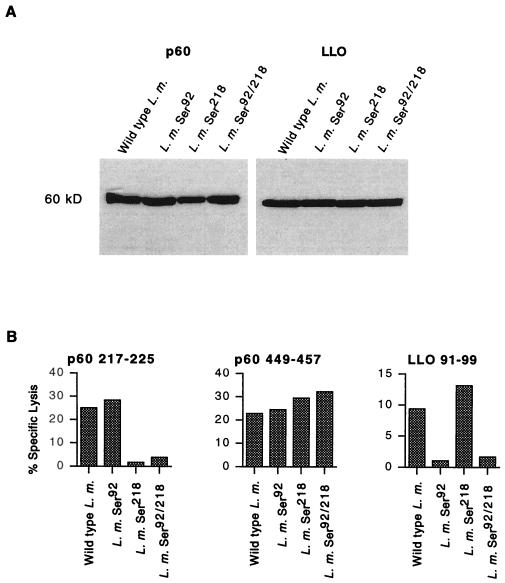

LLO and p60 are both essential for L. monocytogenes virulence (3, 17). Therefore, our first objective was to determine if the mutagenized strains of L. monocytogenes secreted normal amounts of LLO and p60 and if in vivo virulence was maintained. The wild-type strain and the three mutant strains of L. monocytogenes were grown in broth cultures, and supernatants were probed for the expression of LLO and p60 by Western blotting (Fig. 2A). The amounts of p60 and LLO produced by all three mutant strains were identical to that produced by the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A). To confirm that LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 were no longer generated in infected cells as a result of the mutations in the MHC class I H-2Kd anchor position, we infected J774 cells with wild-type and mutant L. monocytogenes strains and acid eluted and HPLC fractionated MHC class I-associated peptides. We used this method previously to identify and quantify L. monocytogenes-derived, H-2Kd-associated peptides (34, 36, 43–46, 51, 52). Infected cells were lysed in 0.1% TFA, and low-molecular-weight peptides were HPLC fractionated and tested for recognition by CTL clones specific for LLO 91-99, p60 217-225, and p60 449-457 (Fig. 2B). TFA extracts of cells infected with L. monocytogenes Ser92 contained p60 217-225 and p60 449-457 but not LLO 91-99, while cells infected with L. monocytogenes Ser218 contained LLO 91-99 and p60 449-457 but not p60 217-225. Cells infected with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 did not contain either LLO 91-99 or p60 217-225 but contained the same amounts of p60 449-457 as wild-type and single-epitope mutant L. monocytogenes strains, indicating that these strains infected J774 cells to similar extents. These results indicated that while antigen secretion, cellular infectivity, and antigen processing remain unchanged, the presentation of dominant epitopes is abolished in the mutant L. monocytogenes strains.

FIG. 2.

Anchor mutations do not alter LLO or p60 secretion but prevent LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 generation. (A) Wild-type and mutant L. monocytogenes (L. m.) strains were grown to the stationary phase in BHI broth, and culture supernatants were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, probed with p60 (left panel)- and LLO (right panel)-specific antisera, and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence as described in Materials and Methods. (B) J774 cells were infected with each of the L. monocytogenes strains, and epitopes were TFA extracted and HPLC fractionated. The relevant HPLC fractions were tested in a 4-h 51Cr release assay with P815 target cells and CTL clones specific for p60 217-225, p60 449-457, and LLO 91-99. The percent specific lysis and the strains that were used to infect J774 cells are indicated.

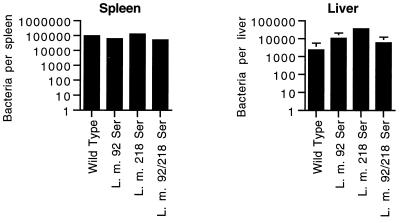

To determine the in vivo virulence of the mutant L. monocytogenes strains, mice were infected intravenously with 2,000 bacteria, and the numbers of live bacteria in the spleens and livers were determined 48 h later (Fig. 3). The numbers of bacteria in both sites of infection were equivalent for all four strains of L. monocytogenes. Thus, tyrosine-to-serine mutations of amino acid 92 of LLO or amino acid 218 of p60 do not affect the ability of the bacteria to establish early infection in mice.

FIG. 3.

Similarity of in vivo virulence of wild-type and mutant L. monocytogenes strains. BALB/c mice were infected in groups of two with 2 × 103 L. monocytogenes (L. m.) wild-type, Ser92, Ser218, or Ser92/218 bacteria. After 48 h, infected spleens and livers were homogenized and the number of viable bacteria was determined. The mean ± standard deviation number of bacteria per spleen or liver is indicated.

Loss of dominant T-cell responses does not alter primary T-cell responses to subdominant epitopes.

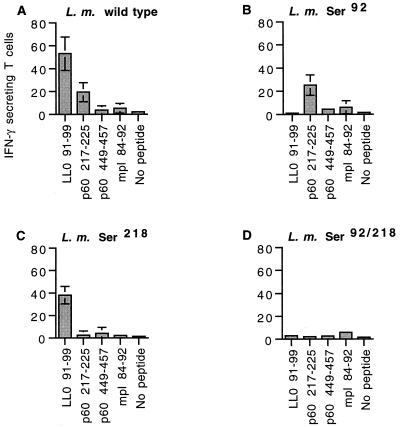

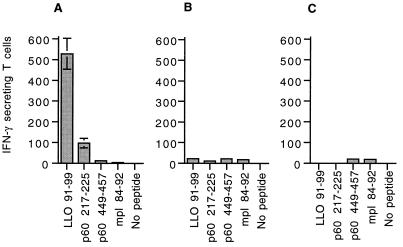

To determine the impact of individual epitope-specific T-cell responses on parallel T-cell responses to other epitopes, we infected CB6 mice with a sublethal dose of each of the L. monocytogenes strains and measured the T-cell responses to LLO 91-99, p60 217-225, p60 449-457, and mpl 84-92 by the ELISPOT assay (28, 49). The T-cell response in mice infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes demonstrated the typical hierarchy: LLO 91-99 > p60 217-225 > p60 449-457 = mpl 84-92 (Fig. 4A), confirming our previous findings (49). As expected, mice infected with L. monocytogenes Ser92 did not have T-cell responses to LLO 91-99 (Fig. 4B) and mice infected with L. monocytogenes Ser218 did not respond to p60 217-225 (Fig. 4C). Remarkably, T-cell responses to the remaining epitopes were unaltered. Loss of T-cell responses to both LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 also did not result in increased responses to mpl 84-92 or p60 449-457 (Fig. 4D). Thus, the large primary responses to the two dominant CTL epitopes do not suppress responses to subdominant epitopes. Additionally, removing a dominant epitope (p60 217-225) from a protein antigen containing a subdominant epitope (p60 449-457) did not change the response to the subdominant epitope (Fig. 4). Thus, with this system we did not see evidence for intermolecular or intramolecular competition between epitopes at the level of the T-cell response.

FIG. 4.

Elimination of dominant CTL epitopes does not increase responses to subdominant epitopes during the primary response to L. monocytogenes infection. Groups of three age-matched CB6 (H-2b × H-2d) mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 103 L. monocytogenes (L. m.) bacteria of each strain. Immune splenocytes were assayed 7 days following infection by an ELISPOT assay with P815 cells pulsed with each of the epitopes. The number of IFN-γ-secreting T cells per 100,000 splenocytes responding to wild-type (A), L. monocytogenes Ser92 (B), L. monocytogenes Ser218 (C), and L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 (D) infection is shown. The values represent the means ± standard deviations for three mice.

Absence of dominant responses does not enhance recall responses to subdominant epitopes.

The preceding experiment demonstrated that dominant T-cell responses do not diminish subdominant responses during a primary T-cell response. To determine if T cells responding to recall infection behaved similarly, we reinfected BALB/c mice that had been immunized with a sublethal dose of wild-type bacteria or L. monocytogenes Ser92/218. Reinfection of wild-type-immune mice with wild-type L. monocytogenes resulted in a dramatic expansion of LLO 91-99- and p60 217-225-specific T cell populations (Fig. 5A), consistent with previous findings (7). T-cell populations specific for p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 remained relatively small and subdominant. When wild-type-immune or L. monocytogenes Ser92/218-immune mice (Fig. 5B and C) were reinfected with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218, T cells specific for p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 underwent a small expansion. The small numbers of LLO 91-99- and p60 217-225-specific T cells detected in mice immunized with wild-type L. monocytogenes (Fig. 5B) represented memory T cells induced during primary infection. Interestingly, recall infection of these mice with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 boosted the number of T cells specific for the subdominant epitopes to approximately the same level as the memory response to the dominant epitopes. The finding that the recall responses to p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 were identical in mice primed with the wild type (Fig. 5B) and L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 (Fig. 5C) supported the notion that dominant T-cell responses do not suppress subdominant responses during T-cell priming.

FIG. 5.

The absence of dominant T-cell populations does not enhance recall responses to subdominant epitopes. Two groups of three BALB/c mice were infected with 2,000 wild-type L. monocytogenes bacteria, and then one group each was reinfected 4 weeks later with 100,000 wild-type bacteria (A) or L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria (B). A third group of BALB/c mice was infected with 2,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria and reinfected 4 weeks later with the same strain (C). The magnitude of the T-cell response per 100,000 splenocytes was quantified 6 days following reinfection by an ELISPOT assay. The values represent the means ± standard deviations for three mice.

Impaired T-cell responses to dominant epitopes during recall infection following immunization with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218.

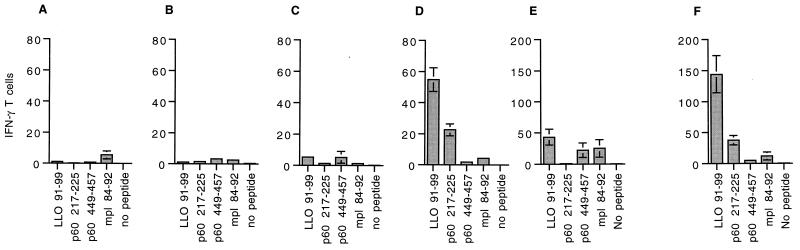

Mice infected with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218, despite lacking the two dominant epitopes, cleared bacteria from their livers and spleens and developed specific, protective immunity (49a). It is likely that CD8+ T cells specific for subdominant epitopes and CD4+ T cells specific for MHC class II-restricted antigens conferred protective immunity in the absence of LLO 91-99- and p60 217-225-specific T cells (22). We next wanted to determine if primary T-cell responses to LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 would occur in the context of a recall response to L. monocytogenes infection. We therefore immunized CB6 mice with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 and then reinfected the mice with L. monocytogenes Ser92. Immunization with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 primed only subdominant responses to p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 (Fig. 6A), and reinfection with L. monocytogenes Ser92 did not result in detectable expansion of p60 217-225-specific T cells (Fig. 6B). Similarly, when mice that had been primed with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 and boosted with L. monocytogenes Ser92 were reinfected with wild-type L. monocytogenes, only very small responses to LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 were detectable (Fig. 6C). Both of these responses were dramatically smaller than the primary responses to infection with wild-type L. monocytogenes (Fig. 6D). As shown in the previous experiment (Fig. 5), T cells specific for p60 449-457 and mpl 84-92 did not expand significantly, even after the third L. monocytogenes infection (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Priming to dominant epitopes is markedly diminished in mice previously immunized with L. monocytogenes. (A) Three CB6 mice were immunized with 5,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria and assayed by an ELISPOT assay 4 weeks later. (B) Three CB6 mice were immunized with 5,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria and reinfected 3 weeks later with 100,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92 bacteria. ELISPOT analysis of splenocytes was performed 7 days following reinfection. (C) Three CB6 mice were immunized with 5,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria, reinfected 3 weeks later with 100,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92 bacteria, and then reinfected a second time with 100,000 wild-type bacteria. Splenocytes were assayed by the ELISPOT assay 7 days following the third infection. (D) To demonstrate the normal T-cell response, a group of naive CB6 mice was infected with 5,000 wild-type L. monocytogenes bacteria, and ELISPOT analysis was performed 7 days later. (E) Three BALB/c mice were immunized with 2,000 L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 bacteria and reinfected 3 weeks later with 100,000 wild-type bacteria. Immune splenocytes were assayed by the ELISPOT assay 6 days following reinfection. (F) Three naive BALB/c mice were infected with 2,000 wild-type L. monocytogenes bacteria, and immune splenocytes were assayed by the ELISPOT assay 7 days later. The plotted values are the means for three mice and represent the number of epitope-specific T cells per 100,000 splenocytes; error bars indicate standard deviations.

During the course of these experiments, we discovered that the magnitude of the T-cell response to H-2Kd-restricted epitopes was greater in BALB/c mice (H-2d) than in CB6 mice (H-2b × H-2d). One likely explanation for this finding is that positive selection is more effective in mice homozygous as opposed to heterozygous for the selecting MHC allele (1). Since infected BALB/c mice may be a more sensitive model for detecting marginal T-cell responses, we primed BALB/c mice with L. monocytogenes Ser92/218 and then reinfected them with wild-type bacteria (Fig. 6E). A small response to LLO 91-99 was detected in mice reinfected with wild-type bacteria (Fig. 6E), while the response to p60 217-225 remained undetectable. The response to LLO 91-99, however, was markedly diminished in comparison to the primary response to LLO 91-99 in naive BALB/c mice (Fig. 6F). These findings demonstrate that the priming of T cells specific for dominant epitopes is markedly impaired if a preexisting immune response to L. monocytogenes is present.

DISCUSSION

T-cell expansion in response to infection is a complex process, ultimately resulting in T-cell subpopulations that differ in size and specificity. The mechanisms that determine T-cell responses remain unknown. Our experiments with L. monocytogenes strains that lack immunodominant T-cell epitopes indicated that (i) T-cell responses to immunodominant CTL epitopes do not inhibit responses to subdominant epitopes and (ii) priming of T cells to new dominant epitopes is inefficient in mice that have preexisting immunity to L. monocytogenes. Our findings shed light on the mechanisms that underlie in vivo T-cell activation and expansion and may have practical consequences for vaccine design and development.

Studies of T-cell responses to antigens containing multiple epitopes or to viral pathogens have suggested that T lymphocytes of different specificities compete against one another (14, 18, 30, 33). In this type of scenario, dominant T-cell populations can be considered “winners,” while subdominant T-cell populations are “losers.” At what level could such competition occur among dominant and subdominant T-cell populations? It is possible that dominant populations occupy disproportionate amounts of space in lymphatic tissues, crowding out subdominant T cells. A variant of this hypothesis is that the antigen-presenting cell surface may become covered with dominant T cells, precluding adequate stimulation of subdominant T cells. A third possibility is that dominant T-cell populations deplete the local environment of growth-promoting cytokines, thereby starving subdominant populations. In such a competitive environment, elimination of winners should allow losers to flourish. However, our experiments with mice infected with L. monocytogenes suggested that there is negligible competition between T cells specific for dominant and subdominant peptides. Thus, the robust T-cell expansion in response to LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225 during primary infection does not inhibit T-cell expansion to subdominant epitopes. One difference between our system and viral systems is that L. monocytogenes infections are rapidly cleared, and T-lymphocyte expansion is transient, ceasing within 7 days of immunization (7). Thus, unlike responses to more chronic viral infections, T-cell responses following primary L. monocytogenes infection may more closely reflect T-cell priming than in vivo T-cell expansion. Therefore, our findings suggested that T-cell priming following L. monocytogenes infection is not competitive.

The lack of competition between T-cell responses to different epitopes has important implications for vaccine design. We previously showed that the size of memory T-cell populations in immune mice directly reflects the magnitude of primary T-cell responses to a particular epitope (7, 49). Thus, maximizing primary T-cell responses to specific epitopes is an appropriate goal for engineered vaccines. Our finding that T-cell responses to two dominant epitopes did not compete with each other and did not suppress T-cell responses to two subdominant epitopes suggested that vaccine vehicles can contain multiple antigens without endangering the magnitude of the response to any one component. Indeed, studies with recombinant adenoviruses expressing tumor epitopes have suggested that CTLs specific for multiple antigens can be primed simultaneously (48). Further quantitative studies are required to determine the level of complexity that the immune system can tolerate before individual T-cell responses to subcomponents of an antigen diminish.

Mice immunized with an L. monocytogenes strain lacking the two dominant T-cell epitopes recovered from infection and developed specific immunity, consistent with the findings of Bouwer and colleagues (2) using an L. monocytogenes strain lacking LLO 91-99. This finding was not surprising, since L. monocytogenes is a complex pathogen and protective immunity is mediated by both CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes (35). Additionally, although LLO 91-99- and p60 217-225-specific CTLs constitute the majority of responding CD8+ T lymphocytes in H-2d mice (7), the remaining, aggregated subdominant T-cell populations are likely capable of mediating protective immunity. A remarkable finding of our experiments was the poor priming of dominant T-cell populations in mice previously immunized with L. monocytogenes lacking LLO 91-99 and p60 217-225. This result can be most easily explained by the rapid clearance of L. monocytogenes in immune mice and the inadequate presentation of the new epitope to naive T lymphocytes. Surprisingly, however, the amount of the epitope presented during a second L. monocytogenes infection was sufficient to restimulate memory cells specific for dominant epitopes and to promote their in vivo expansion (Fig. 5A). Thus, although dominant epitopes were presented during the recall infection, their level probably fell below the threshold required for T-cell priming but was above the threshold required for restimulating memory T cells. Although the precise threshold for T-cell priming is unknown, previous work from our laboratory has shown that a fivefold increase in epitope quantity can change undetectable T-cell responses into dominant, optimal responses (50).

Our finding that a repeat infection with L. monocytogenes failed to prime T cells specific for new epitopes raises concern about the utility of this bacterium as a carrier for immunization with heterologous antigens. Numerous studies with naive mice have demonstrated that immunization with recombinant L. monocytogenes expressing heterologous antigens primes T-cell responses and can induce protective antiviral immunity (16, 23, 39, 42). L. monocytogenes is a ubiquitious organism, and serologic studies have demonstrated that most people have been exposed to this bacterium (20). Thus, underlying immunity to L. monocytogenes may preclude adequate priming to recombinantly expressed heterologous antigens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants AI-33143 and AI-39031 from the U.S. Public Health Service. E.G.P. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences, and S.V. was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant AI07019-20, NIH National Research Service Award F32 AI09629-02, and a Brown-Coxe fellowship from Yale University School of Medicine.

We thank Marlena Moors and Daniel Portnoy for helpful advice on the generation of L. monocytogenes mutant strains. Dirk H. Busch is acknowledged for helpful discussions and reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg L J, Frank G D, Davis M M. The effects of MHC gene dosage and allelic variation on T cell receptor selection. Cell. 1990;60:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90352-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouwer H G, Moors M, Hinrichs D J. Elimination of the listeriolysin O-directed immune response by conservative alteration of the immunodominant listeriolysin O amino acid 91 to 99 epitope. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3728–3735. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3728-3735.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bubert A, Kuhn M, Goebel W, Kohler S. Structural and functional properties of the p60 proteins from different Listeria species. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8166–8171. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8166-8171.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burg S H V D, Visseren M J W, Brandt R M P, Kast W M, Melief C J M. Immunogenicity of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules depends on the MHC-peptide complex stability. J Immunol. 1996;156:3308–3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch D H, Bouwer A G A, Hinrichs D, Pamer E G. A nonamer peptide derived from Listeria monocytogenes metalloprotease is presented to cytolytic T lymphocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5326–5329. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5326-5329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busch D H, Pamer E G. MHC class I/peptide stability: implications for immunodominance, in vitro proliferation and diversity of responding CTL. J Immunol. 1998;160:4441–4448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch D H, Pilip I M, Vijh S, Pamer E G. Coordinate regulation of complex T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. Immunity. 1998;8:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butz E A, Bevan M J. Massive expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during an acute virus infection. Immunity. 1998;8:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80469-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilli A, Goldfine H, Portnoy D A. Listeria monocytogenes mutants lacking phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C are avirulent. J Exp Med. 1991;173:751–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao W, Meyers-Powell B A, Braciale T J. The weak CD8+ CTL response to an influenza hemagglutinin epitope reflects limited T cell availability. J Immunol. 1996;157:505–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W S, Khilko S, Fecondo J, Margulies D H, McCluskey J. Determinant selection of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigenic peptides is explained by class I-peptide affinity and is strongly influenced by nondominant anchor residues. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1471–1480. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cresswell P. Assembly, transport and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly K, Nguyen P, Woodland D L, Blackman M A. Immunodominance of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted influenza virus epitopes can be influenced by the T-cell receptor repertoire. J Virol. 1995;69:7416–7422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7416-7422.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng Y, Yewdell J W, Eisenlohr L C, Bennink J R. MHC affinity, peptide liberation, T cell repertoire, and immunodominance all contribute to the paucity of MHC class I-restricted peptides recognized by antiviral CTL. J Immunol. 1997;158:1507–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falk K, Roetzschke O, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Rammensee H-G. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature. 1991;351:290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frankel F R, Hedge S, Lieberman J, Paterson Y. Induction of cell-mediated immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein by using Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vector. J Immunol. 1995;155:4775–4782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Sansonetti P. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986;52:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gegin C, Lehmann-Grube F. Control of acute infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in mice that cannot present an immunodominant viral cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope. J Immunol. 1992;149:3331–3338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gellin B G, Broome C V. Listeriosis. JAMA. 1989;261:1313–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gentschev I, Sokolovic Z, Kohler S, Krohne G F, Hof H, Wagner J, Goebel W. Identification of p60 antibodies in human sera and presentation of this listerial antigen on the surface of attenuated salmonellae by the HlyB-HlyD secretion system. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5091–5098. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5091-5098.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Germain R N. MHC-dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for T lymphocyte activation. Cell. 1994;76:287–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harty J T, Schreiber R D, Bevan M J. CD8 T cells can protect against an intracellular bacterium in an interferon gamma-independent fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11612–11616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikonomidis G, Paterson Y, Kos F J, Portnoy D A. Delivery of a viral antigen to the class I processing and presentation pathway by Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2209–2218. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufmann S H E. Immunity to intracellular microbial pathogens. Immunol Today. 1995;16:338–342. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehner P J, Cresswell P. Processing and delivery of peptides presented by MHC class I molecules. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitsky V, Zhang Q-J, Levitskaya J, Masucci M G. The life span of major histocompatibility complex-peptide complexes influences the efficiency of presentation and immunogenicity of two class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes in the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 4. J Exp Med. 1996;183:915–926. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengaud J, Vicente M F, Chenevert J, Pereira J M, Geoffroy C, Gicquel-Sanzey B, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz J C, Cossart P. Expression in Escherichia coli and sequence analysis of the listeriolysin O determinant of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1988;56:766–772. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.766-772.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyahira Y, Murata K, Rodriguez D, Rodriguez J R, Esteban M, Rodriguez M M, Zavala F. Quantification of antigen specific CD8+ T cells using an ELISPOT assay. J Immunol Methods. 1995;181:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00327-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murali-Krishna M, Altman J D, Suresh M, Sourdive D J D, Zajac A J, Miller J D, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mylin L M, Bonneau R H, Lippolis J D, Tevethia S S. Hierarchy among multiple H-2b-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes within simian virus 40 T antigen. J Virol. 1995;69:6665–6677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6665-6677.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niedermann G, Butz S, Ihlenfeldt H G, Grimm R, Lucchiari M, Hoschutzky H, Jung G, Maier B, Eichmann K. Contribution of proteasome-mediated proteolysis to the hierarchy of epitopes presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Immunity. 1995;2:289–299. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikcevich K M, Kopielski D, Finnegan A. Interference with the binding of a naturally processed peptide to class II alters the immunodominance of T cell epitopes in vivo. J Immunol. 1994;153:1015–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oldstone M B, Lewicki H, Borrow P, Hudrisier D, Gairin J E. Discriminated selection among viral peptides with the appropriate anchor residues: implications for the size of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte repertoire and control of viral infection. J Virol. 1995;69:7423–7429. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7423-7429.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pamer E G. Direct sequence identification and kinetic analysis of an MHC class I-restricted Listeria monocytogenes CTL epitope. J Immunol. 1994;152:686–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pamer E G. Immune response to Listeria monocytogenes. In: Kaufmann S H E, editor. Immune response to Listeria monocytogenes. R. G. Austin, Tex: Landes; 1997. pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pamer E G, Harty J T, Bevan M J. Precise prediction of a dominant class I MHC-restricted epitope of Listeria monocytogenes. Nature. 1991;353:852–855. doi: 10.1038/353852a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pamer E G, Sijts A J A M, Villanueva M S, Busch D H, Vijh S. MHC class I antigen processing of Listeria monocytogenes proteins: implications for dominant and subdominant CTL responses. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Restifo N P, Bacik I, Irvine K R, Yewdell J W, McCabe B J, Anderson R W, Eisenlohr L C, Rosenberg S A, Bennink J R. Antigen processing in vivo and the elicitation of primary CTL responses. J Immunol. 1995;154:4414–4422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schafer R, Portnoy D A, Brassell S A, Paterson Y. Induction of a cellular immune response to a foreign antigen by a recombinant Listeria monocytogenes vaccine. J Immunol. 1992;149:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sercarz E E, Lehmann P V, Ametani A, Benichou G, Miller A, Moudgil K. Dominance and crypticity of T cell antigenic determinants. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:729–766. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast W M, Melief C J, Oseroff C, Yuan L, Ruppert J, Sidney J, Guerico M-F D, Southwood S, Kubo R T, Chestnut R W, Grey H M, Chisari F V. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1994;153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen H, Slifka M K, Matloubian M, Jensen E R, Ahmed R, Miller J F. Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes as a live vaccine vehicle for the induction of protective anti-viral cell-mediated immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3987–3991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sijts A J A, Pamer E G. Enhanced intracellular dissociation of major histocompatibility complex class I-associated peptides: a mechanism for optimizing the spectrum of cell surface-presented cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1403–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sijts A J A M, Neisig A, Neefjes J, Pamer E G. Two Listeria monocytogenes CTL epitopes are processed from the same antigen with different efficiencies. J Immunol. 1996;156:685–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sijts A J A M, Pilip I, Pamer E G. The Listeria monocytogenes p60 protein is an N-end rule substrate in the cytosol of infected cells: implications for MHC class I antigen processing of bacterial proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19261–19268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sijts A J A M, Villanueva M S, Pamer E G. CTL epitope generation is tightly linked to cellular proteolysis of a Listeria monocytogenes antigen. J Immunol. 1996;156:1497–1503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith G A, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston N C, Portnoy D A, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogenes have overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toes R E M, Hoeben R C, Voort E I H V D, Ressing M E, Eb A J V D, Melief C J M, Offringa R. Protective anti-tumor immunity induced by vaccination with recombinant adenoviruses encoding multiple tumor associated cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes in a string-of-beads fashion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14660–14665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vijh S, Pamer E G. Immunodominant and subdominant CTL responses to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:3366–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Vijh, S., and E. G. Pamer. Unpublished data.

- 50.Vijh S, Pilip I M, Pamer E G. Effect of antigen processing efficiency on in vivo T cell response magnitudes. J Immunol. 1998;160:3971–3977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villanueva M S, Fischer P, Feen K, Pamer E G. Efficiency of antigen processing: a quantitative analysis. Immunity. 1994;1:479–489. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villanueva M S, Sijts A J A M, Pamer E G. Listeriolysin is processed efficiently into an MHC class I-associated epitope in Listeria monocytogenes-infected cells. J Immunol. 1995;155:5227–5233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viner N J, Nelson C A, Unanue E R. Identification of a major I-Ek-restricted determinant of hen egg lysozyme: limitations of lymph node proliferation studies in defining immunodominance and crypticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2214–2218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]