Abstract

In Australia, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the exponential growth in the delivery of telehealth services. Medicare data indicates that the majority of telehealth consultations have used the telephone, despite the known benefits of using video. The aim of this study was to understand the perceived quality and effectiveness of in-person, telephone and videoconsultations for cancer care. Data was collected via online surveys with consumers (n = 1162) and health professionals (n = 59), followed by semi-structured interviews with telehealth experienced health professionals (n = 22) and consumers (n = 18). Data were analysed using descriptive statistics and significance was tested using the chi-square test. A framework analysis and thematic analysis were used for qualitative data. Results indicate telehealth is suitable for use across the cancer care pathway. However, consumers and health professionals perceived videoconsultations facilitated visual communication and improved patients’ quality of care. The telephone was appropriate for short transactional consultations such as repeat prescriptions. Consumers were rarely given the choice of consultation modality. The choice of modality depended on a range of factors such as the type of consultation and stage of cancer care. Hybrid models of care utilising in-person, video and telephone should be developed and requires further guidance to promote the adoption of telehealth in cancer care.

Keywords: COVID-19, cancer care, telehealth, pandemic, consumer experience, consultation mode, videoconsultation

Introduction

In Australia, telehealth has been used extensively as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response to deliver core health services.1 Australia's public health insurer, Medicare, reimburses telehealth consultations provided by either telephone or video. Currently, around 90% of Medicare subsidised telehealth involves telephone consultations only.2

Video, when compared to telephone consultations, resulted in greater clinician prescription, diagnostic and decision-making accuracy, and confidence in managing patients during critical consultations.3,4 However, access to technology and internet connectivity remain key barriers for videoconsultations, particularly for remote populations.5,6 For this reason, telephone consultations have been considered more accessible and quick to set up.7

Like other health care services, Australian cancer care services adopted telehealth to reduce the risk of infection for immunocompromised patients and ensure continuity of care. Cancer care often involves complex management. Questions are raised whether complex care can be delivered effectively by telehealth,8,9 and whether telephone consultations are appropriate for this type of care. The aim of this study was to compare perceived quality, effectiveness and preferences for in-person, telephone and videoconsultations for cancer care management.

Methods

Using online surveys and semi-structured interviews, telehealth experiences during the COVID-19 were collected from clinicians and consumers of Australian cancer care services. Data were analysed using a multi-method approach.

Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Queensland's Human Research Ethics committee (2021/HE000544) and health service approval under the National Mutual Acceptance scheme (HREC/QTHS/76461). Governance approval was obtained for each cancer care service.

Participants and recruitment

Six cancer service sites across Australia were recruited to participate in the study based on their service characteristics. Sites were purposively chosen for maximum variation in terms of characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Site characteristics.

| State | Organisation and telehealth service characteristics | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | NSW | Predominately metro, some rural, public, newer service |

| 2 | VIC | Predominately metro, public, established service |

| 3 | TAS | Predominately rural/remote, private, newer service |

| 4 | WA | Rural/remote, public, established service |

| 5 | NSW | Rural/remote, public, established service |

| 6 | QLD | Rural/remote, public, established service |

A primary contact at each site promoted and distributed the online survey to health service staff (senior managers, clinicians and telehealth administrators) and their consumers. For staff, the online survey link was distributed by email. For consumers, a link to the online survey was also distributed via Cancer Australia, Cancer Councils and Australian Facebook cancer support groups. Participant information and consent forms were contained within both survey links, and consent required before commencing the survey.

Participants were invited to provide contact details as part of the survey if they were interested in participating in an interview. Respondents who expressed interest were contacted by phone or email. Participant information was sent and was consent was obtained. Primary contacts at each site also approached the staff with extensive telehealth experience to participate in an interview.

Data collection

Between July and November 2021, participants completed the online survey, which evaluated their use and experience of telehealth for cancer care and management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Survey questions were developed by the research team, tested with health staff and consumers and accessed via the Qualtrics survey platform.

The team developed interview questions, tested them during four interviews with health staff and consumers and made minor amendments. All interviews were conducted using video or audio conferencing. Participants were asked about their telehealth experiences and telephone and video conferencing preferences. For staff interviews, senior managers were also asked to comment on organisational factors of transitioning or upscaling telehealth use.

Interviews were conducted by authors AB and MT, recorded and automated transcripts were generated. All transcripts were de-identified. Interviews concluded once data saturation was reached.

Data analysis

Survey responses were analysed using descriptive statistics and significance was tested using the chi-square test. Qualitative analysis of the interview data was undertaken using NVivo™ software and coded deductively using Model of Assessment in Telemedicine (MAST)10 framework domains. Thematic analysis was then conducted to identify key themes within each MAST domain. Peer debriefing11 among the research team occurred throughout the analysis process, wherein coding discussion informed the analysis for the final results. This paper reports findings related to consultation methods (in-person, telephone and video consultations).

Results

Characteristics of survey participants

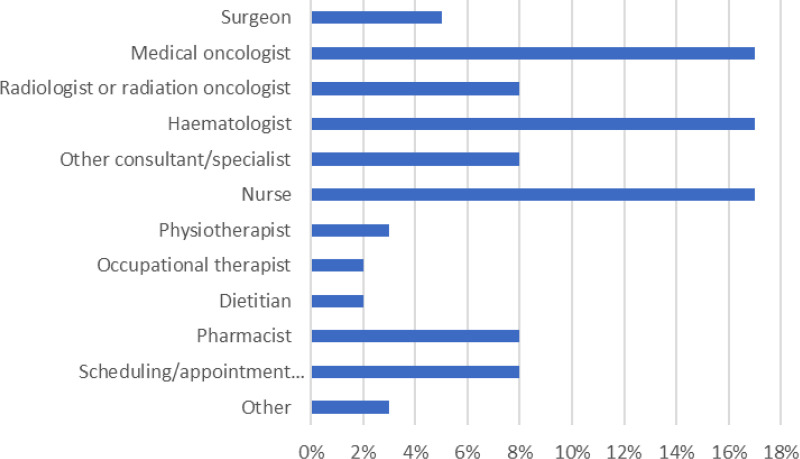

Clinicians (N = 59) worked in 14 different professional roles (Figure 1) and provided care for 22 types of cancer. Most worked with adults and 50% (n = 29) worked with young adults, and children. Consumers (N = 1162) were mainly female (79%, n = 924), over half (57%, n = 665) were aged between 51 and 70 years and 3% (n = 30) identified as being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent.

Figure 1.

Professional roles of clinician and administrator survey respondents (N = 59).

Characteristics of interview participants

Interviews were conducted with 22 clinicians and service administrators who were on average 48 years old, predominately female (73%, n = 16) with clinicians working on average 15 years in cancer care. Consumers (N = 18) were predominantly male (67%, n = 12) with an average age of 51 years and represented all Australian states but not the territories.

Quantitative findings

Device use and internet connectivity

In total, clinicians (88%, n = 52) and consumers (31%, n = 358) reported using both the telephone and video for consultation. Of these, 7% (n = 4) of clinicians and 49% (n = 575) of consumers only used telephone and 3% (n = 2) of clinicians and 20% (n = 229) of consumers only used video. For video consultations, consumers used desktops or laptops (57%, n = 409), mobile phones (22%, n = 162), tablets (20%, n = 145) and most (85%, n = 977) had sufficient internet connectivity to attend a video call.

Telephone and video use across the cancer pathway

Clinicians

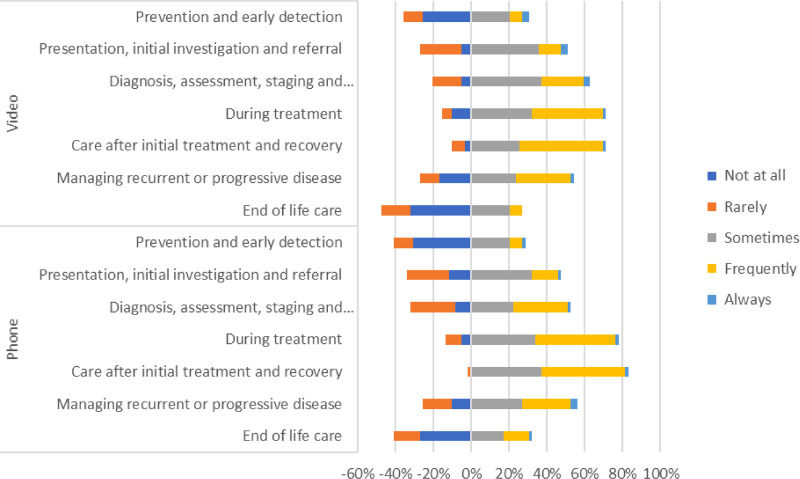

Clinicians used telephone and video consultations across the cancer care pathway, although telephone use was more frequent than video. Telehealth (both telephone and video) were less likely to be used than in-person consultations at the initial and end stages of cancer care. Telehealth was most frequently used during the treatment stage, care after initial treatment and follow-up stage (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinician use of video and telephone across the cancer care pathway (N = 59).

Consumers

Consumers confirmed telephone and video were used along all parts of the cancer pathway but most commonly for follow-up and managing ongoing disease (Figure 2). The most reported phase for using telehealth was during post-treatment for follow-up, communicating test results and staying connected with clinicians to ask questions. Video was used as frequently as telephone across the cancer care pathway, except for follow-up and recovery where telephone was used more frequently.

Effectiveness and quality of care

Clinicians’ perspectives

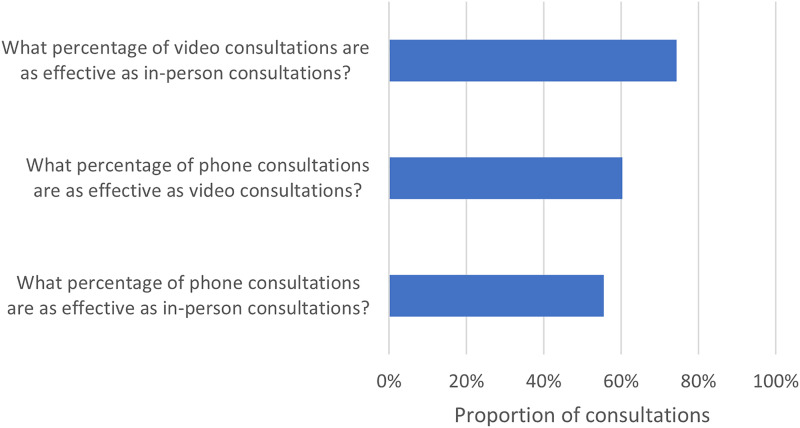

When asked about the relative effectiveness of consultation modalities (in-person, telephone, video), clinicians perceived that in-person consultations were the “gold standard” and most effective. Consultations conducted via video were perceived to be 15% more effective than those conducted over the telephone (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of clinician and service administrator perceived effectiveness of telehealth consultations (N = 56).

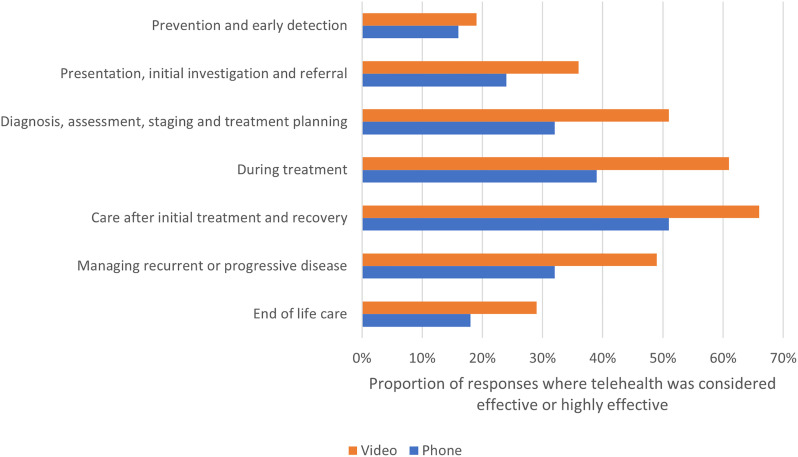

Overall, telephone and video were effective across the cancer care pathway. However, they were considered less effective for prevention and early detection and end-of-life care. Figure 4 compares the responses where clinicians perceived telehealth to be useful or highly useful. At all pathway steps, clinicians perceived video to be more effective than telephone.

Figure 4.

Comparison of clinician and administrator perceptions of telephone and video consultation effectiveness where telehealth was considered effective or highly effective (N = 59).

Consumers’ perspectives

Consumers considered telephone and video consultations acceptable for cancer care and management. However, video users (88%, n = 517) were significantly (χ2 = 13.1439; p = 0.0003) more likely to be happy with the quality of their treatment in comparison to telephone users (81%, n = 756). Furthermore, those who took part in video consultations (68%, n = 400) were significantly (χ2 = 21.385; p < 0.0001) more likely to feel that the video consultations achieved just as much as an in-person appointment in comparison to telephone users (56%, n = 526). Telephone respondents (51%, n = 478) thought their issues and concerns would have been better understood by their health professional if they had seen them in-person compared to video users (33%, n = 191). Most respondents thought a mix of in-person and telephone (83%, n = 772) or video (86%, n = 504) consultations would be helpful to patients.

Qualitative findings

Clinicians’ experiences, perceptions of effectiveness and safety of telephone and video consultations

Qualitative analysis indicated that clinicians considered video more appropriate than telephone across the cancer care pathway. They reported routine in-person follow-up consultations may be substituted by video consultations to formulate hybrid models of care. Telephone and video consultations were scarce when patients required physical examinations or procedures, although some participants highlighted general practitioners could support telehealth consultations when examinations were required. Although video was considered more effective than telephone, there were some circumstances when telephone consultations were useful, such as for short reviews.

I think you can use a video link for every appointment that is required. The limiting factor is examination. [You] cannot put your hand on the belly, stethoscope on the chest But I often use the GP and I think it's really great to bring them into the space. However, when you need a full examination, obviously face-to-face is a priority… I think phone should be very restricted. I think phone conversations can be appropriate when you’ve got a set of results that are outside of the context of a clinic visit that you want to follow up. I know radiation oncologists use it a lot for follow up in the long term - when they’re past their primary therapy, to make sure there's been no emerging toxicity. Phone check in can be really, really useful but I think it's fairly restricted to short follow-up consultative reviews: checking a blood test, checking that their mucositis is getting better and they’re eating and drinking. I don't think it should be used for routine comprehensive review and it shouldn't be used for delicate conversations. With a lot of my patients that are in a more routine, even a post-acute routine follow-up, what I often do is two telehealth to one face to face or one telehealth to one face to face. – Staff participant 12

Clinicians commonly reported that the sole use of telephone maybe unsafe due to the heavy reliance on patient reporting, rather than seeing patients on video and gaining visual information.

I think the risk of the telephone consultation is that you’re not able to see the patient's face when they answer a question and pick up on any cues that the patient may be displaying despite what they’re saying, whereas with video conference you can detect that someone is uncomfortable. – Staff participant 1

Suggestions were given to improve the safety and effectiveness of telehealth, such as having a nurse or other health professional accompany the patient to conduct physical examinations when necessary. It was also emphasised, should difficult or emotional conversations arise, patients need a supportive environment on their end of a consultation, either from a health professional or family member.

Sometimes people question when you are at a crossroads in someone's treatment journey, or there is a delicate conversation, whether you should be doing that face-to-face [or by telehealth]. I’ve done it both situations. I think the most important thing is the patient needs to feel comfortable, safe in their space, and have the appropriate supports around them and feel that you are still engaging with them…. clinicians just need to be cognisant of actually setting up a surround appropriately before delivering a videoconference. – Staff participant 12

Suggestions for improving effectiveness and safety included more reliable technology and clear audio and video connections. If there was a “glitch” in the video conferencing platform or poor reception on either end, staff who perceived video as more effective and safer, often reverted to telephone.

Consumers’ satisfaction and perception of the quality of telephone and video consultations

Overall, there was strong agreement that both the telephone and video consultations were acceptable for cancer care and management. However, consumers frequently reported they did not feel as engaged with their clinician using telephone.

I never felt like I was being focused on in those phone conversations… but at least being able to see the [clinician's] face and see the visual cues of their facial expressions, I think has helped – Consumer participant 6

Consumers ranked different modalities of consultations from most valuable to least: in-person, video, and then telephone. However, given this ranking, consumer participants did not want all their consultations in-person. Their consultation mode preference depended on various factors, including consultation type, physical and mental health condition, risk of infection, mobility, existing relationship with a clinician, and location. Their preference changed throughout their cancer journey. The consultation mode, telephone or video, was determined by the clinician. Rarely were patients given a choice.

When I had to telehealth, certainly with the gynaecologist and my medical oncologist, they haven't even given me the choice of Zooming. They just ring you. And the GP. So, for all three, didn't get a choice. – Consumer participant 9

In general, in-person appointments were preferred for initial diagnosis, physical treatment and examination, and critical points of care requiring decisions for treatment and care. For other consultations, such as follow-up consultations, patients wanted to have the option to have either in-person or video consultations. Telephone was considered acceptable for short informational consultations.

Videoconsultations were considered to provide higher quality communication compared to telephone as consumers were able to see the facial expressions and body language of the clinician, which aided and improved communication.

I definitely prefer the video to the phone. And I think they probably prefer it, too. I definitely am keeping a real eye on the doctor's face, you know, like body language. – Consumer participant 11

Discussion

Telehealth use expanded rapidly at the onset of COVID-19 as a method of reducing viral exposure and providing continuity of care for cancer patients.1 This study found that telehealth (both telephone and video) can be used to deliver cancer care services. Telehealth was most frequently used during the treatment, care after initial treatment and follow-up stages of cancer care management.12 It was least frequently used at the initial and end stages of management. Clinicians perceived in-person care to be the most effective, followed by video and then telephone. Consumers perceived video consultations to significantly improve the quality of care compared to telephone. Consumers also felt that video consultations were significantly more likely than a telephone consultation to achieve as much as an in-person appointment. Telephone respondents perceived their issues and concerns would have been better understood by their health professionals if they had seen them in-person. Most consumers thought a mix of in-person, telephone, and video consultations would be ideal.

Video provides non-verbal communication and visual examination

In our study, clinicians perceived video to be more effective than telephone with the latter resulting in a loss of non-verbal communication and visual examination.13 Oncologists and other health professionals have previously established that visual information is necessary for reading body language, visual cues and expressions during a consultation.14–17 Whether it be collected indirectly during conversation, or directly as a tool for assessment, visualisation allows doctors to accurately understand the condition of their patient.

Similar to clinicians, we found that consumers have a preference to use video during consultations because video enables them to see and interact with their doctors, allowing rapport building and stronger doctor–patient communication.13

Telephone is suitable for low-complexity consultations

Although telephone was the least favourable method of telehealth amongst consumers and clinicians, telephone consultations were considered suitable for low-complexity consultations such as repeat prescriptions or providing test results that require no further discussion. Telephone calls regarding blood test results have previously been associated with positive telehealth experiences amongst patients.18 This is likely due to the ease and convenience of delivering simple test results, such as blood tests, for doctors and patients.9,19

Clinicians make the decision about whether to use telephone or video

We found that clinicians decided whether to use telephone or video, without consulting the patient. Clinicians have previously expressed concern in assessing patient eligibility for telehealth, calling for clearer guidelines.13,20 With changes in policy and increased availability of telehealth consultations, this study highlights the importance of developing guidelines that support patients being provided with a choice for their consultation mode.

Strengths of this study included data collected from both clinicians and consumers of services, use of surveys and interviews to elicit stakeholder's perceptions and maximum variation sampling in choice of cancer care service. Cancer care may involve complex medical intervention, high acuity, and frequent associated allied health and psycho-social interactions. A limitation of this study is that the findings are specific to cancer care services. We encourage similar research to be carried out for non-cancer related clinical telehealth services.

Conclusion

This study assessed the perspectives of multidisciplinary oncology clinicians, administrators and consumers and revealed several findings. Videoconsultations were more favourable as they facilitated visual communication and improved patients’ quality of care. Telephone use is appropriate for simple consultations and is required as a precautionary method for those without access to technology and clinicians tend to decide which telehealth modality is suitable for a patient. Such findings have numerous implications for practice. Firstly, a hybrid approach should be implemented for the delivery of cancer care services, where in-person, video and telephone are employed to deliver services. Choice of modality will depend on various factors, including stages of cancer care management, access to technology and whether online viewing will aid communication as part of consultations. Additionally, clinicians should be aware and considerate of consumer preference for video consultations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants and Roshni Mendis for their support in developing this paper.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Cancer Australia.

ORCID iDs: Annie Banbury https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8841-1215

Anthony C Smith https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7756-5136

Monica L Taylor https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5333-2955

Helen M Haydon https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9880-9358

Liam J Caffery https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1899-7534

References

- 1.Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare 26: 309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snoswell CL, Caffery LJ, Haydon HM, et al. Telehealth uptake in general practice as a result of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Aust Health Rev 2020; 44: 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rush KL, Howlett L, Munro A, et al. Videoconference compared to telephone in healthcare delivery: A systematic review. Int J Med Inf 2018; 118: 44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhajri N, Simsekler MCE, Alfalasi B, et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward telemedicine consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Med Inform 2021; 9: e29251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas EE, Haydon HM, Mehrotra A, et al. Building on the momentum: Sustaining telehealth beyond COVID-19. J Telemed Telecare 2022; 28: 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGuzman PB, Bernacchi V, Cupp CA, et al. Beyond broadband: Digital inclusion as a driver of inequities in access to rural cancer care. J Cancer Surviv 2020; 14: 643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Guzman KR, Snoswell CL, Giles CM, et al. GP perceptions of telehealth services in Australia: A qualitative study. BJGP open 2022; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaverdian N, Gillespie EF, Cha E, et al. Impact of telemedicine on patient satisfaction and perceptions of care quality in radiation oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021; 19: 1174–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson L, Qi S, Delure A, et al. Virtual cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Alberta: Evidence from a mixed methods evaluation and key learnings. JCO Oncology Practice 2021; 17: e1354–e1e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidholm K, Clemensen J, Caffery LJ, et al. The model for assessment of telemedicine (MAST): A scoping review of empirical studies. J Telemed Telecare 2017; 23: 803–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln YS, Guga EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsonson A O, Grimison P, Boyer M, et al. Patient satisfaction with telehealth consultations in medical oncology clinics: A cross-sectional study at a metropolitan centre during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Telemed Telecare 2021: 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith SJ, Smith AB, Kennett W, et al. Exploring cancer patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ utilisation and experiences of telehealth services during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White V, Bastable A, Solo I, et al. Telehealth cancer care consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study of the experiences of Australians affected by cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022; 30: 6659–6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neeman E, Kumar D, Lyon L, et al. Attitudes and perceptions of multidisciplinary cancer care clinicians toward telehealth and secure messages. JAMA Network Open 2021; 4: e2133877-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tevaarwerk AJ, Chandereng T, Osterman T, et al. Oncologist perspectives on telemedicine for patients with cancer: A national comprehensive cancer network survey. JCO Oncology Practice 2021; 17: e1318–e1e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen N P, Skou KE, Boe Danbjørg D. Health care professionals’ experiences with the use of video consultation: Qualitative study. JMIR Form Res 2021; 5: e27094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kjeldsted E, Lindblad KV, Bødtcher H, et al. A population-based survey of patients’ experiences with teleconsultations in cancer care in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Oncol 2021; 60: 1352–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christiansen MG, Pappot H, Pedersen C, et al. Patient perspectives and experiences of the rapid implementation of digital consultations during COVID-19 — a qualitative study among women with gynecological cancer. Support Care Cancer 2022; 30: 2545–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aung E, Pasanen L, LeGautier R, et al. The role of telehealth in oncology care: A qualitative exploration of patient and clinician perspectives. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022; 31: e13563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]