Abstract

Heterocyclic molecules are well-known drugs against various diseases including cancer. Many tyrosine kinase inhibitors including erlotinib, osimertinib, and sunitinib were developed and approved but caused adverse effects among treated patients. Which prevents them from being used as cancer therapeutics. In this study, we strategically developed heterocyclic thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivatives by an organic synthesis approach. These synthesized molecules were assessed against the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase domain (EGFR-TKD) by in silico methods. Molecular docking simulations unravel derivative 17 showed better binding energy scores and followed Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. The binding affinity displayed by synthetic congener and reference molecule erlotinib was found to be −8.26 ± 0.0033 kcal/mol and −7.54 ± 0.1411 kcal/mol with the kinase domain. Further, molecular dynamic simulations were conducted thrice to validate the molecular docking study and achieved significant results. Both synthetic derivative and reference molecule attained stability in the active site of the TKD. The synthetic congener and erlotinib showed free energy binding (ΔGbind) −102.975 ± 3.714 kJ/mol and −130.378 ± 0.355 kJ/mol computed by Molecular Mechanics Poison Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) method. In addition, the motions of each sampled system including the Apo complex were determined by the principal component analysis and Gibbs energy landscape analysis. The in-vitro apoptosis study was performed using MCF-7 and H-1299 cancer cell lines. However, thiazolo-[2,3-]-quinazoline derivative 17 showed fair anti-proliferative activity against MCF-7 and H-1299. Further, the in-vivo study is necessary to determine the effectivity of the potent anti-proliferative, non-toxic molecule against TKD.

Keywords: EGFR-TKD; Thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone; MD Simulations; Free energy Landscapes; Apoptosis

1. Introduction

The EGFR-TKD is extensively expressed in various types of cancers (Chang et al., 2016). The binding of tumor growth factor alpha (TGFα) to the ectodomain of EGFR-TKD activates downstream signaling such as STAT, Ras, Raf MAPK, AKT, and JNK pathways, promoting DNA synthesis, differentiation, and cell proliferation (Luwor et al., 2004, Oda et al., 2005, Troiani, et al., 2012). The altered tyrosine kinase and its associates are known as oncogenic drivers. TKD is the most chosen therapeutic target in human malignancies. Targeting EGFR-TKD and its associates with small molecules is useful in cancer management (Oda et al., 2005, Chevallier et al., 2021, Gonda and Ramsay, 2015. Phytochemicals, semi-synthetic, and synthetic compounds, as well as antibodies, are used to treat cancer (Sequist, 2008, Brewer, et al., 2013, Barnes, 2017). Rationally designed small molecules are effective against EGFR-TKD and inhibit downstream signaling cascades (Allen et al., 2015, Metibemu et al., 2019, Seshacharyulu et al., 2012).

The heterocyclic molecules play a pivotal role in medicinal chemistry and are distinguished by the presence of substituents such as carbon, sulphur, and nitrogen (Kerru et al., 2020). Heterocyclic compounds exhibited anti-viral, anti-fungal, and anti-cancer properties (Amewu et al., 2021, Pathania et al., 2019). Following the literature, the first generation fused heterocyclic compound erlotinib, a competitive ATP binding inhibitor against EGFR-TKD, was discovered (Engelman & Janne, 2008) and was approved by the FDA (U.S.A) for the treatment of cancer (Cohen et al., 2003, Elkamhawy., A. et al., 2015). Biologically active heterocyclic therapeutic agents containing nitrogen, such as quinoline, pyridine, azole, pyridine, pyrimidine, pyrrole, oxadiazole, and their adjuvants exhibit anticancer properties (Alanazi, et al., 2014, Rashad et al., 2008). The heterocyclic compounds inhibit the cell proliferation studied on (MCF-7, HepG2, and Caco-2) and attained IC50 values ranging from 23 to 70 µM (Noser et al., 2020). Furthermore, the quinazolinone-based rhodanine was synthesized via Knoevenagel condensation processes and tested against HL-60 and K-562, which exhibits IC50 ranging between 1.2 and 1.5 µM (El-Sayed et al., 2017).

In drug repurposing, computational tools were found useful for the virtual screening of small and macromolecules in order to determine the mechanism underlying the target (Meng et al., 2011). Currently, machine learning techniques were used to investigate the interactions of biomolecular systems, atoms, and proteins, thus becoming an efficient tool in both commercial and academic sectors. Furthermore, new approaches based on machine learning, such as meta-dynamics, Quasi-Newton, and Newtonian dynamics were employed to determine surface energy by solving the motion of molecular systems. AMBER, CHARM, dl-POLY, ESPRESSO, GROMACS, GROMOS, MOE, NAMD, LAMMPS, QUANTUM, VMD, YASARA, and a variety of additional web servers are used to investigate system motion, conformational space, and identification of drug molecules (Durrant and McCammon, 2011, Aminpour et al., 2019). The biological activity of heterocyclic thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivatives synthesized by microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAO’s) and multi-domino reaction (MDR) method (Rahmati and Pashmforoush, 2015, Masoumi et al., 2020, Mohanta et al., 2020) are unexplored.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are attributed for 71 % of all deaths worldwide. Cancer was one of the leading causes of NCDs in India, accounting for 63 % of all deaths (Mathur, et al., 2020). Previous attempt has been made to estimate the cancer incidence in various part of the country (Sarkar, Datta, Debbarma, Majumdar, & Mandal, 2020), that required urgent medical attention to cripple it. However, the approved drugs against EGFR-TKD showed adverse toxicities effects such as skin rashes, vomiting, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity. So, non-toxic drugs are required to eliminate or minimize the adverse effects among patients. In this study, an insight into the binding interplay of the thiazolo-[2,3-b] quinazolinone derivatives with the therapeutic target (EGFR-TKD) via molecular dockings and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations would be studied and analyse. Multiple search engines would be used to identify the lead molecule with non-toxic behaviour from the database. Further, the free binding energy was computed by the MM-PBSA method. The pairwise residue motion/displacement of amino acids was monitored from initial to final conformations by dynamic cross-correlation matrix plots. The residual motion of the complexes during simulations is determined by the principal component analysis, and the meta-stable conformational energy states of ligand-bound protein complexes were determined by the Gibbs energy landscape analysis. Furthermore, the apoptosis assay was done by treating MCF-7 & H-1299 cell lines with thiazolo-[2,3-b] quinazolinone derivative. In milieu, the biological properties of newly synthesized quinazolinone heterocycles and their validations as anti-cancer agents are on the rage and might be the next-generation anti-cancer drugs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Synthesis of Thiazolo-[2,3-b] quinazolinones characterization and identifications.

The synthesis was done by Microwave-assisted organic synthesis and multi-dominos reaction approaches (Rahmati and Pashmforoush, 2015, Masoumi et al., 2020, Mohanta et al., 2020). The identifications were done by TLC, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and LC-MS (Figures S1, S2, & S3).

2.2. Preparation of EGFR-TKD target protein

The wild-type EGFR-TKD X-ray crystallographic structure 1 M17(Stamos et al., 2002) was obtained from the online databasewww.rcbs.com.

The structural analysis of the tyrosine kinase domain of EGFR was done by using the https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/icn3d web server (Wang et al., 2019).

The occupancy of the amino acids in the binding site was found in both domains of EGFR-TKD. The co-crystal ligand Erlotinib (AQ44) bound EGFR-TKD was removed from the PDB 1 M17 3D structure. The protein was prepared, water molecules were removed, and hydrogen was incorporated by using 3D protonate module of MOE09 software (Halgren, 1996). Before the simulation, the structure was initially minimized in a vacuum for 1 ns using the GROMOS96 force field to remove the clashes in the structure, and then protein was dumped for further molecular investigations such as molecular docking simulations and molecular dynamics simulations.

2.3. Ligand properties and molecular docking assessment

The synthetic heterocyclic molecules (17 derivatives and reference erlotinib) were prepared by using MOE09 software using the MMFF94x force field (Figure S7). The SWISSadme, pkCSM, and MolSoft L.L.C online servers (Daina et al., 2017, Pires et al., 2015) were used to calculate the pharmacokinetic behaviour of the molecules. The 2D structures were converted to a Simplified Line Entry System (SMILES) by using open babel (O’Boyle et al., 2011). The SMILES were used as inputs to obtain the ADMET properties and drug-likeness score. The online servers are pre-loaded by two binary sets of libraries containing molecules that have weighed and non-weighed drug indexes, and molecules with toxic and non-toxic fragments. The toxicity and drug-likeness score were generated from the discrete set of libraries. Once inputs are uploaded to the web server, the binary libraries split by the correlation regression method and generate the respective value of the molecule based on the skeleton of the structure. The suitable drug candidate identified by ADMET was optimized by the density functional theory (DFT) method using the B3YLP/ 6–311 + G* level of theory. The lower unoccupied molecular orbitals and higher occupied molecular orbitals were evaluated using ORCA 4.0.1 Linux 64-bit. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap, hardness, softness, ionization energy, electrophilic energy, electron affinity, and electronegativity was calculated to determine the stability and reactivity of the ligand (Parr et al., 1999). The virtual screening was carried out by Autodock 4.2 software using ADT tools https://autodock.scripps.edu/(Trott & Olson, 2010) in the grid box of the protein. The grid box was selected by setting up grid dimensions at the center 62 × 46 × 58 (x, y, z) and box center X = 25.517, Y = 0.052, Z = 54.719 with grid spacing of 0.358, Å. The total of 10 poses were set for each ligand and all poses generated were minimized in the binding site using default Lamarckian genetic algorithm. The binding score was calculated based on the sum of the distances between atom pairs.

| (i) |

where, epair(d) = w1*Gauss1(d) + w2*Gauss2(d) + w3*Repulsion(d) + w4*Hydrophobic(d) + w5*HBond(d).

2.4. Assessment of molecular dynamic simulations

The molecular dynamic simulations were carried out by using gromacs 5.1.1 setup (Jo et al., 2008, Pereira et al., 2019). The starting structure of the MD was obtained from molecular docking simulation results. The topology was generated using AMBER99SB-ILDN.ff (Wang et al., 2006, Lindorff-Larsen et al., 2010) with recommended TIP 3-point model. The ligand forcefield parameters were assigned by t-leap using a General amber force field (GAFF) (Sousa da Silva and Vranken, 2012, Kashefolgheta and Verde, 2017). The complex was placed in the grid box which is 1 nm apart from the periodic boundaries (Mark & Nilsson, 2001). One counter Cl ion was added to the system to neutralized it and to avert infinite charges due to periodic condition, which were implemented in conjunction with Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) (Darden et al., 1993). The steepest descent method was then used to perform energy minimizations and the system was equilibrated with 100 ps in an NPT and NVT ensemble with a velocity rescaling thermostat and a Berendsen barostat (Berendsen et al., 1984). The temperature and pressure were adjusted to 300 K and 1 bar respectively. The Coulomb’s cut-off scheme was kept at 1.2 nm and long-range electrostatic interactions were handled by the PME algorithm. To constrain the bond length LINICS algorithm was selected (Borkotoky and Murali, 2018, Hess et al., 1997). The simulations for each complex were performed by applying a time step of 2 fs for 100 ns simulations at 300 K and 1 atm, under an NPT ensemble with a velocity-rescaling thermostat and Parrinello-Rahman barostat (Brooks et al., 2009), to sustain temperature and pressure close to reference values. The simulations of each system were performed in triplicates (3 × 3 = 9).

2.5. Molecular mechanics poisson Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) calculations.

The average free energy binding of synthetic congener derivative 17 and erlotinib bound EGFR-TKD complexes was performed by using g_mmpbsa (Kumari & Kumar, 2014). The input files needed for free energy binding calculations were obtained after the completion of molecular dynamic simulations. The free energy was calculated by linearized traditional PBE methods. Multiple debye-huckle sphere boundary conditions and ionic strength 0.150 M concentrations were used and default grid dimensions are × = 129, y = 129 and z = 97 Å.

The average free energy binding was calculated by the bootstrap method using MmPbSaStat.py. The decomposition energy of each amino acid contributes for free energy bindings was calculated by the MnPbDecomp.pyMmPbSaDecomp.py module of g_mmpbsa. The ΔGbind was calculated according to the following equation.

| (ii) |

Gcomplex denotes the total free energy of the protein–ligand complex, whereas the isolated total free energy of protein and ligand are represented as Gprotein and Gligand in the above-given equation.

The free energy of an individual entity is summed up by the equation given below:

| (iii) |

The protein–ligand complex is denoted by X, and EMM denotes an average molecular mechanic’s potential energy in a vacuum, as calculated by equation (iii).

Gsolvation denotes the free energy of solvation, TS denotes the entropic free energy contribution in a vacuum, and T denotes temperature and S entropy.

| (iv) |

Ebonded represents the collective interactions of the dihedral, angle, and bond. whereas the nonbonded interactions consist of van der Waals (EvdW) and electrostatic (Eelec) interactions.

Furthermore, Free Energy of Solvation, Polar Solvation Energy, Non-polar Solvation Energy, SASA-Only, and polar models were calculated. The decomposed contributions of the free energy binding of each amino acid are calculated from ΔEMM, ΔGpolar, and ΔGnonpolar.

2.6. Principal component analysis

The movement of amino acids to a set of linearly uncorrelated variables is commonly studied using the principal component (PCA) analysis of statistics (Aier et al., 2016). To begin with, the covariance matrix and eigenvalues were built using the Gromacs package gmx anaeig. By diagonalizing the covariance matrix, the eigenvectors were calculated. The associated motions in a sampled system were found using the gmx covar module. The graphs were created using the Xmgrace program (https://plasma-gate.weizmann.ac.il/Grace/).

2.7. Assessment of free energy landscape (FEL)

The Gibbs energy landscape of Apo complex, EGFT-TKD bound erlotinib, and synthetic compound 17 were used to determine the structure close to the native structure of sampled complexes (protein–ligand complexes and without ligand (Apo) complexes). Gibb's free energy is a function of enthalpy and entropy that examines the conformational states that are critical for the structure–function relationship of proteins. The Gibbs free energy landscape pictograms were evaluated from the Cα trajectory of three sampled systems using the g_sham module GROMACS (Aier et al., 2016, Bekker et al., 1993, Berendsen et al., 1995, Lindahl et al., 2001, Singh et al., 2015).

2.8. Cell culture and in-vitro cell proliferation assay.

The Indian Institute of Chemical Biology (I.C.G.B.) Kolkata, India provided human breast cancer and human non-small cell lung cancer (MCF-7 and H-1299). All chemicals and reagents were bought from Sigma Aldrich (U.S.A) and utilized. In addition to 10 % FBS, 1 % streptomycin/penicillin, and 2 mM l-glutamine, complete Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) was used to resuscitate the cultures. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humid environment with CO2. Cells were confluent to between 80 and 90 % before experiments were performed. Furthermore, 5000 cells were seeded in 94-well plates, with one well left empty. The MTT assay was conducted to evaluate the IC50 value of derivatives 17 by applying dose-dependent concentrations such as 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 µM against the MCF-7 and H-1299 cell lines (Mir et al., 2022, Saluja et al., 2020).

2.9. Detection of apoptosis by EtBr/AO staining

The apoptotic cell death was identified using the AO/EtBr staining. The IC50 concentration of synthetic derivative and noscapine was applied to H-1299 & MCF-7 cells seeded in 6-well plates containing coverslips for 72 h. After incubation, coverslips were fixed in cold methanol, stained with EtBr and AO (10 µg/ml), cleaned with PBS, and mounted on a slide, and images were captured using the fluorescent microscope. (Nikon Eclipse Ts2R-FL) (Mir et al., 2022, Behera et al., 2022).

3. Results

3.1. The target EGFR-TKD protein

The X-ray crystallographic structure 1 M17 with a resolution of 2.60 Å was obtained from the online database https://www.rcbs.org(Stamos et al., 2002).

The https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/icn3d was used for protein sequence annotation (Wang et al., 2019). Domain 1 of EGFR-TKD represented the β-helix sheet of 104 amino acids, and Domain 2 composed of the αC-helix set was annotated in pink color with a horizontal line of 229 amino acid residues (Fig. 1a). The active site/ATP binding site occupies, some of the amino acids from the β-helix sheet and some from the αC-helix set in EGFR-TKD. Another binding site is known as a substrate/polypeptide binding site composed of 7 amino acid residues. The activation loop (A-Loop) acted as a linker between β-helix and αC-helix. The dimer interface is projected outwards for continuing the dimerization domains of EGFR-TKD. The black annotations represent the presence of amino acid residue and their position in the sequence. The 3D structure is suitable for molecular docking as no amino acids are missing from the binding sites hence are valid for further in silico investigation.

Fig. 1.

(a) Annotation of the protein sequence of EGFR-TKD and (b) Global electrophilicity and associated terms related to quantum calculations by DFT method of synthesized thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivative 17and erlotinib drug molecule.

3.2. Ligand properties

The heterocyclic compounds have diverse biological activity in the field of cancer therapeutics. 60.33 % of the heterocyclic drugs were approved by the FDA which is almost two-thirds of the total structures designed from the year 2010 to 2015 (Pearce, 2017) and so on. The set of 17 derivatives including references (erlotinib & noscapine) were loaded in 3 different web servers such as Swissadme, pkCSM, and Molsoft L.L.C respectively. The solubility in water over octanol was predicted as the partition of coefficient (QPlog Po/w). It was higher and the water solubility coefficient (QPlogS) was found to be low. All molecules accept the (RO5) Lipinkisi rule of five. These chemicals exhibit high intestinal absorption (QPPcaco) due to a favorable balance of solubility and permeability via passive diffusion, among the whole series. These molecules can be removed through the kidney because of their polarity index. The LogP value indicated molecules had permeability through biological membranes. The toxicity parameters were calculated thoroughly in the synthesized series, and a drug-like molecule was achieved which could be used further as a therapeutic agent. The understudy drug-like candidate (derivative 17) did not show any toxicity and is not the inhibitor of the HerG-I & HerG-II (ether-go-go-related gene) compared to the reference molecule erlotinib (Table S1, S2, & S3). Furthermore, the drug-like molecule followed ADMET properties and was introduced for quantum calculations. The DFT calculations were done by an ab-initio semiempirical method using the B3YLP/6–311 + G* level of theory.

The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lower unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), and energy gap calculations were done to determine the global electrophilicity of drug-like thiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolinone. The electrophilicity and electronegativity of the thiazolo-[2,3-b] quinazolinone are comparable to the reference molecule (erlotinib) (Table 1). The nucleophilic center (N, S, NH2) fused with pyrimidine holds HOMO energy distribution whereas, LUMO energy distributions were found onto nitro-phenyl ring-substituted over the pyrimidine (Fig. 1b). The fused fluorescence base acted as a reaction center in synthesized derivatives. The ΔE value was determined from HOMO and LUMO shifts. Erlotinib showed ΔE = 2.22 eV and the ΔE of synthesized thiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolinonewas found to be 2.497 eV. The similarities in global electrophilicity insights thiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolinone may also be a reliable therapeutic agent. The global parameters of the thiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolinone molecule were found similar to that of the erlotinib (Table 1).

Table 1.

Global electrophilicity and associated terms calculated by DFT method (1) erlotinib drug molecule and (2) synthesized thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivative 17.

| S.No. | EHOMO (eV) | ELUMO (eV) | E gap (eV) | I = -EHOMO (eV) | µ=-I + A/2 | A = -ELUMO (eV) | χ = I + A/2 | η = I-A/2 | σ = 1/η | ω = μ2/2η |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | −5.068 | −2.845 | 2.222 | 5.068 | −3.957 | 2.845 | 3.957 | 1.111 | 0.900 | 7.041 |

| 2. | −5.550 | −3.053 | 2.497 | 5.550 | −4.302 | 3.052 | 4.302 | 1.249 | 0.801 | 7.410 |

3.3. Molecular docking analysis

The bioinformatics tools are very easy to access small molecules and proteins to investigate the nature of biomolecular systems in aqueous and any other solvents. Machine learning methods are used to analyze the ligand–protein, protein–protein interactions, and binding free energy. The virtual screening of the synthesized library was done by molecular docking simulation methods and the Lamarckian genetic algorithm was employed to obtain the binding score.

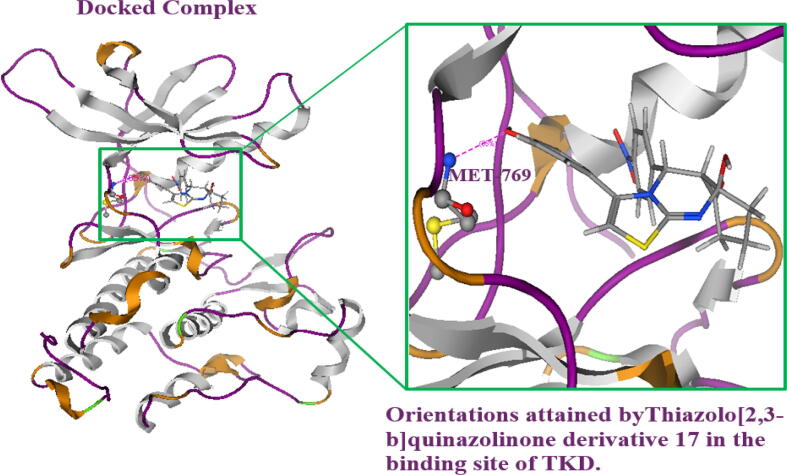

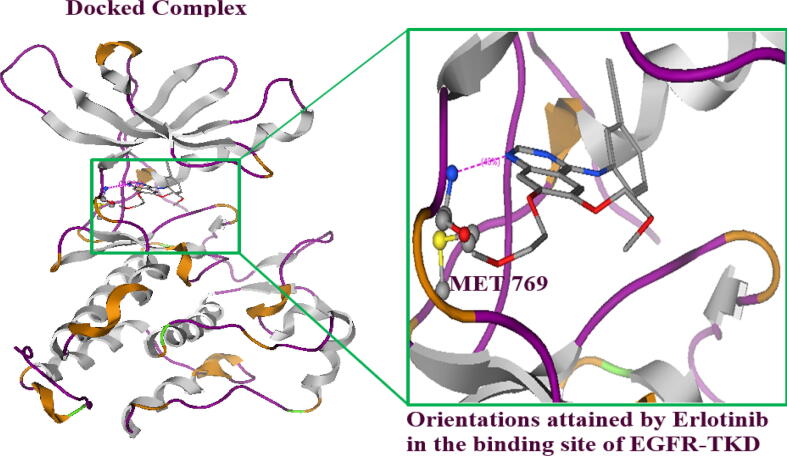

The synthesized drug-like compound “IUPAC name” 9a-hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-nitrophenyl)-5,5a,7,8,9,9a-hexahydrothiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolin-6-one (derivative 17) and reference known as erlotinib (AQ44) were docked in the binding site of the EGFR-TKD. All docked poses were minimized in the binding site of TKD and the interactions exhibited by each possess were found with key amino acids present in the binding site (Fig. 2a). The interactions exhibited with residues of the receptor TKD protein provided insights into bindings with the specific amino acids in the catalytical site (Fig. 2b, Fig. 2c). The binding energy of the newly designed heterocyclic ligand with EGFR-TKD was found to be −8.26 ± 0.0033 kcal/mol which was higher than the reference drug molecule erlotinib −7.54 ± 0.1411 kcal/mol against EGFR-TKD (Table 2) and binding affinity of each pose were given in (Table S4). The heterocyclic synthesized ligand exhibited interactions with amino acids Lys:721, Met:769, Leu:768, Cys:773 Asp:830, and Asp:831 showing identical binding interactions as exploited by the reference compound with the target protein. The interactions exhibited by erlotinib with Met:769 in the binding site at the hinge region of EGFR-TKD supported previous studies (Stamos et al., 2002). The hydrogen bonding and dominant hydrophobic interactions were found with the catalytic site of EGFR-TKD.

Fig. 2a.

The docked poses of thiazolo-[2,3-b] quinazolinone derivative 17 were minimized in the binding site of EGFR-TKD. It was found that pose no 4th attained similar docking orientations as achieved by the reference molecule in the binding site.

Fig. 2b.

The sythesized derivative 17 showed interactions with amino acid MET769 with the EGFR-TKD in the binding site in the hinge region. The top docking hit was exhibited by heterocyclic synthesized molecules with EGFR-TKD in the binding pocket.

Fig. 2c.

The docking orientations of co-crystallized ligand (erlotinib), retain the previous docking orientations and showed interactions with MET 769 in the hinge region after redocking in the catalytic site of EGFR-TKD.

Table 2.

Docking score of the thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivative 17 and reference with wild-type EGFR-TKD.

| SI No. | Ligand | Free Energy Binding (Kcal/mol) | Ligand efficiency (L.E) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type EGFR-TKD | |||

| 1 | Thiazolo-2,3-b quinazolinone (Derivative 17) | −8.26 ± 0.0033 | −0.27 ± 0.00 |

| 2 | Erlotinib | −7.54 ± 0.1411 | −0.26 ± 0.005 |

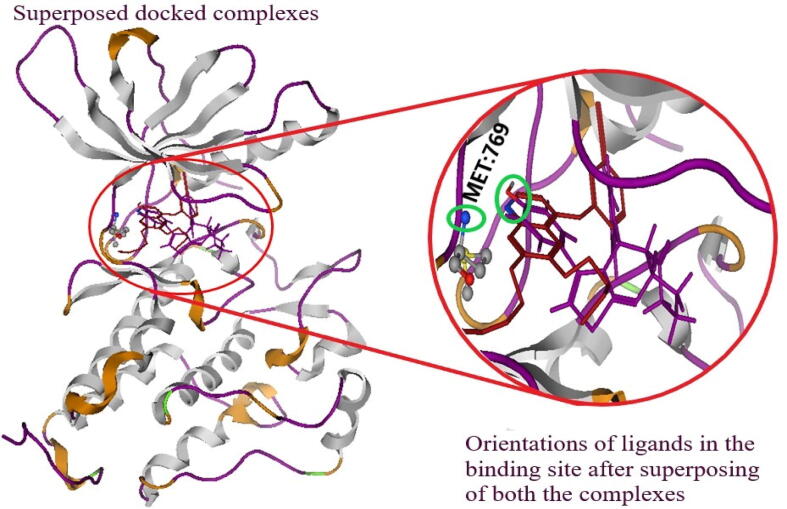

The MOE09 was used to build the sequence alignment of docked complexes. The EGFR-TKD bound synthesized ligand complex was superposed with target template reference bound EGFR-TKD. The spatial orientations of the ligand in the docked complexes were determined by superposing the (i) reference bound EGFR-TKD with (ii) synthetic congener bound EGFR-TKD with each other and it was found that synthesized heterocyclic ligand-bound EGFR-TKD exhibited similar docking orientations as like reference molecule (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2d.

The docked complexes were superposed after dockings. The erlotinib are represented as red and derivative 17 in pink. The interacted moieties of both the ligands were colored as elemental. The receptor MET 769, showed interactions with OH and N of derivative 17, and erlotinib was represented within a green circle. Both EGFR-TKD bound reference (erlotinib) and synthesized ligand showed similar orientations in the binding site of the EGFR-TKD.

3.4. Molecular dynamics simulations

MD simulations allow the atoms and molecules to interact and determine the motions of the molecular system and compute the trajectories in a sampled system during simulation (Patodia et al., 2014). Molecular dynamic simulations of reference and synthetic ligand with EGFR-TKD were carried out. The Apo complex was simulated to determine the behaviour of the protein in an aqueous medium. The RMSD of ligand movement, backbone Cα, the radius of gyrations, solvent accessible surface area, and the number of hydrogen bonds formed were evaluated. The energy of the reference-bound TKD complex was found to be −12104.1496 kJ/mol and the synthetic ligand-bound EGFR-TKD complex was −12694.8869 kJ/mol are average energy of the whole complex calculated by mmpbsa module of gromacs. The higher negative energy was found in the synthetic derivative bound TKD complex. The root mean square deviations were assessed to determine the difference in values from the initial to the final simulation period. The ligand movement was determined by the rms module of gromacs 5.1.1. The average RMSD was found to be 0.05 – 0.3 nm throughout the simulation period it was 0.08–0.28 nm when simulated with the reference compound. Both ligands showed linear RMSD trajectories with TKD for 100 ns of simulation course (Fig. 3). When the ligand was superposed onto the respective ligand, the RMSD was found 0.05–0.18 nm till 100 ns in both complexes (Fig. 3). It was found that both ligands reference (erlotinib), as well as a synthetic compound, stabilized from the very initial phase of simulation within the binding site of the EGFR-TKD till the simulation course is over. These insights into the binding stability of the newly designed molecule will be prudentially a good therapeutic agent. The RMSF of three complexes simulated with and without ligand showed higher fluctuations at C-terminus and N-terminus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The MD Simulations of 17 derivative and reference molecule erlotinib with EGFR-TKD and RMSD plots were generated. The upper plot represents the ligand–protein RMSD, the middle plot represents ligand RMSD, and the below plot represents RMSD Cα simulations. The RMSF plot of three complexes is represented in a separate plot. The RMSD plots of three simulated replicas of synthetic congener represented are black, red, and green, and for reference molecule, it is represented by marrow, yellow and blue, and Apo complex is represented as pink, cyan, and turquoise.

The RMSD of backbone Cα (synthesized ligand-bound EGFR-TKD complex) was computed and the values were found to be 0.1 – 0.4 nm but at 35 – 40 ns, higher RMSD was observed in the first two replicas of the simulations whereas the third simulation showed the linear RMSD Cα throughout the simulation course. The RMSD Cα of the reference complex was found to be 0.15–0.38 nm. The computed values were compared with the RMSD Cα of the Apo complex. It was found that the Cα of Apo showed an RMSD value of 0.1–0.5 nm which was always higher than the other two simulated complexes.

The compactness was computed from the (ROG) radius of gyrations throughout the simulation period in an aqueous medium. The higher the value of the radius of gyrations less will be the compactness and vice-versa. The ROG value of Apo was found to be 1.95 to 2.25 nm, the reference bound complex exhibited a radius of gyration of 1.95 to 2.02 nm, and synthesized ligand-bound EGFR-TKD showed gyrations value 1.95 to 2.05 nm till 50 ns then the values reduced more and reached below 1.95 nm for next 50 ns of simulations (Figure S4).

The SASA module of the gromacs was used to determine the protein foldings. The lower SASA values reflect lower protein folding whereas a higher value indicates higher folding during simulation. The SASA value of the Apo complex was in the range of 155–175 nm2, EGFR-TKD bound erlotinib was150-165 nm2 and for EGFR-TKD bound synthetic compound complex the value stabilized between 155 and 167 nm2 (Figure S4). The hydrogen bond analysis was carried out using the g_hbond module of grimaces. Two hydrogen bonds were formed by the erlotinib, and the synthetic derivative formed four hydrogen bonds during simulations with EGFR-TKD (Figure S5).

After MD simulations the complexes were dumped and the interactions were observed within the binding site of both the molecules (reference and synthetic derivative 17 with TKD) (Fig. 4a, Fig. 4b) it was found that interactions exhibited by both molecules were the same as observed during molecular docking study.

Fig. 4a.

The interactions exhibited by the derivative 17 in the binding site of the TKD and the amino acids involved in the interactions were found LYS721 & ASP831 followed VDW interactions whereas the MET769 exhibits hydrophobic interactions after MD simulations.

Fig. 4b.

The interactions exhibited by erlotinib in the binding site of the TKD and the interactions were exhibited with MET769 after MD simulations.

3.5. Dynamic cross-correlation analysis during simulations

The motion of the Cα was represented by a cross-correlation matrix which indicated the correlation and anti-correlation motions of the simulated protein. The gmx mdmat module was used to obtain the DCCM correlation matrix. The displacement of amino acids was analyzed after obtaining pair-wise residue motion plots of the first and the last frame (0 & 10000 ps) of the Apo complex. The residual motion of the Apo complex was co-related with the amino acid motion of reference and synthesized molecule-bound EGFR-TKD during simulations was monitored. It was seen that the motion was approximately similar by both ligand-bound complexes. The positive and negative correlations were found at the N lobe and C lobe regions of EGFR-TKD. The reference-bound ligand erlotinib showed anti-correlations at the C lobe region whereas, synthetic compound-bound tyrosine kinase showed anti-correlation at the N lobe region. These motions were identified from the plot of the 100000 ps frame of the simulations. Both reference (erlotinib) and synthetic compound bound tyrosine kinase domain showed anti-correlation with Apo complex of the last frame (100000 ps). The RMSD pairwise distance achieved by the structure at 100000 ps is not too anti-correlated with a reference frame. The pairwise distance of residues was represented in plots (Figure S6).

3.6. PCA analysis of trajectories

The mobility of a protein is frequently determined using fundamental dynamics. (Berendsen and Hayward, 2000, Spezia et al., 2003). The PCA was used to analyze the protein movements and variations of the simulated EGFR-TKD with and without ligand complexes using molecular dynamics trajectory data. Using gmx analysis and the gmx covar module, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors were determined, and the principal components were then calculated (PC1 & PC2). The differential between the three-system, one Apo complex, one reference bound EGFR-TKD, and the synthetic congener bound EGFR-TKD was shown by the PCA scatter plot created from Cα backbone.

On the basis of the PCA plot, a comparison analysis was conducted. At the C-helix, C-lobe, and N-lobe of the reference-bound EGFR-TKD Apo complex, compactness was discovered. (Fig. 5). The dynamic cross-correlation matrix plots and the crucial dynamics data converged to support the structural conformations of the reference, synthetic compound bound, and Apo EGFR-TKD.

Fig. 5.

The PCA scatter plot was determined by gmx covar and gmx anaeig to generate the eigenvalues and eigenvector, then the principal components were generated from the first two components PC1 and PC2 of EGFR-TKD (left) representing EGFR-TKD bound synthetic congener (middle) represents EGFR-TKD bound erlotinib (right) represents Apo complex.

3.7. The Gibbs energy landscape (FEL) analysis

The Gibbs energy landscape was done to determine the meta energy stable states of the complexes. The Gibbs energy was computed for three systems Apo complex, reference complex, and synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD. The red color indicated the maximum stable conformations state and the blue color denoted the minimum conformational stable energy. The average Gibbs energy landscape of reference bound EGFR-TKD and Apo complex was found to be 13.5 kJ/mol, and synthetic compound bound with EGFR-TKD showed 14.233 kJ/mol (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Gibbs energy landscape analysis was calculated from PCA using the g_sham module. The lowest energy was denoted by deep red color and the highest free energy landscape in deep blue color.

The highest stable conformational state was found in the reference bound EGFR-TKD. The graphical meta-state stable conformations were obtained by using the gmx sham module and gmx xpm2ps was used to generate the high-quality images. This study demonstrates the reference bound TKD achieved maximum stability than the other two complexes.

3.8. MM-PBSA calculations

The final 2000 frames were taken to calculate the average free energy binding of synthetic compound and reference. The MmPbSaStat.py was used to calculate the binding affinities of ligand-bound receptors. The free binding energy is a sum of changes in electrostatic energy, van der Waals energy, SASA energy, and polar solvation energy. The bootstrap analysis using g_mmpbsa with the APBS module was used to determine the average free binding energy. The average binding free energy of the synthetic compound was found to be −102.975 ± 3.714 kJ/mol and erlotinib exhibited −130.595 ± 0.908 kJ/mol (Table 3). The potency of the molecule was calculated in terms of the stronger binding energy the low binding energy showed by synthesized molecule should have alternative binding targets and are unexplored.

Table 3.

Calculated (ΔG) free binding energy with thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone derivative and reference molecule erlotinib along with associated parameters.

| No. | Ligand | ΔEVdW (kJ/mol) | ΔEElec (kJ/mol) | ΔGpolar (kJ/mol) | SASA (kJ/mol) | ΔGbinding (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Proposed Ligand | −158.445 ± 2.140 | −72.950 ± 5.710 | 147.270 ± 3.602 | −18.874 ± 0.127 | −102.975 ± 3.174 |

| 2. | Erlotinib | –222.066 ± 0.532 | −53.449 ± 0.623 | 165.597 ± 0.752 | −20.680 ± 0.042 | −130.595 ± 0.908 |

The exhibited ΔEVdW affinity in both cases (derivative 17and erlotinib) is stronger than ΔEElec, H-bond interactions this means that hydrophobic interactions are more in the present case and play a pivotal role in ligands bindings and accommodate ligand in the binding site. The erlotinib showed single interactions with MET:769 and the rest of the interactions are hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2e.

The 2D visualisations were carried out using Ligplot +. The hydrophobic interactions were found dominant over the hydrogen bonding. The red dashed line represents hydrophobic interactions whereas the hydrogen bonding was represented in green dashed lines.

The contributions in the decomposition of energy during simulations by reference erlotinib bound EGFR-TKD and synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD complexes were calculated by using the MmPbSaDecomp.py code. The free energy contributions by each residue of the EGFR-TKD bound ligand complex was determined in Fig. 7a. The binding amino acids that contribute to net free energy binding are Arg 719 = -2.0239, Ile −2.4436, Lys 721 = -6.3263, Leu 764 = -2.4576, Thr 766 = − 2.5339, Met 769 = -0.1698, Cys 773 = -2.7755, Leu 820 = -4.6578 and Thr 830 = -1.1188 results weak hydrogen bonding this may be due to the dominant Vander walls interactions with the amino acids in the bindings.

Fig. 7.

(a) Energy Contribution by each residue during MM-PBSA simulations. The green color denotes energy contributions by erlotinib bound EGFR-TKD and red represents synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD complex (b) the apoptotic cell death at IC50 concentration of the synthetic compound and Noscapine for 72 h compared with untreated and changes are visualized by fluorescence microscopy (c) ANOVA test showed a significant difference in IC50 concentrations between untreated, positive control (Noscapine) and synthetic compound.

4. Cell proliferation and apoptosis detection by EtBr/AO staining

The cell viability of synthetic congener was evaluated by MTT assay. The half-minimal inhibitions in cell proliferation achieved by the ligand were calculated in terms of IC50 value. The IC50 value achieved by the 5bq molecule was found to be 6.4 μM against MCF-7 and 14 μM against H-1299. The 5bq molecules emerge as a potent anti-cancer agent against both cancer cell lines. The IC50 concentration of synthesized congener was treated on MCF-7 cell line and left one untreated, then incubated both (treated and untreated) with ethidium bromide (EtBr) and acridine orange (AO). After 72 h cytology study was done and monographs were captured. These monographs indicate the treated set flourished more than the untreated set because of a higher number of dead cells in the treated set. This indicates apoptotic cell deaths occur due to plasma membrane disintegrity, nuclear condensations, formation of apoptotic blubs, and DNA fragmentation was visualized by fluorescence microscope. The free binding energy exhibited by the synthesized ligand was found lower than erlotinib this probably is because cell inhibitions are regulated through the TKD-mediated pathway and other oncogenic pathways that remain unexplored in the present study.

The statistical analysis was performed using the Tukey test (ANOVA). The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was determined by using GraphPad prism8. Significant differences were identified between treated and untreated sets. The asterisk *** indicates the P value < 0.05 of 5bq molecule treated on H1299 and MCF-7 are more significant than positive control noscapine determines the significant cell death over positive control and analysis was done by using Tukey’s test Fig. 7c.

5. Discussions

Cancer is a deadly disease that accounts for 10 million deaths in 2020 (Ferlay et al., 2021). Researchers study a wide array of databases composed of organic molecules, phytochemicals, azoles, purines, and pyrimidines, and screen them virtually by insilico methods to identify the most probable drug candidate against the EGFR-TKD and address the inhibition pathway of kinases and downstream signaling cascades (Zhao et al., 2019, Padmini et al., 2020). We study a series of compounds that were synthesized by multi-component domino reaction synthesis and are cost-effective. The equimolar mixture of 2-amino-4-phenyl substituted aryl aldehyde, and 1,3-cyclohexanedione was taken in one pot under microwave irradiation for the synthesis of thiazoloquinazolinone derivatives following our previous protocols (Mohanta et al., 2020). The mass spectra of the synthesized compounds play a vital role to establish the structurally diverse thiazoloquinazolinone derivatives. Seventeen derivatives were successfully developed and the pharmacokinetic behavior of the synthesized molecules was studied in detail. The binding mechanism demonstrates that synthesized heterocyclic scaffolds exhibit identical bindings as erlotinib against EGFR-TKD. Simultaneously the ADMET analysis was carried out to identify the safe molecules from the series. Also, in this study, we predict the ADMET properties of some of the previously reported drugs that are inhibitors of EGFR-TKD (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Comparison of reported molecules and their toxicity with newly synthesized derivative. Reported molecules showed toxicity at the prediction level but the derivative 17 of thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone is safe determined by ADMET predictions.

The ADMET prediction showed some EGFR-TKD inhibitors are hepatotoxicity and inhibit the functionality of the herG-I &herG-II gene. In case of toxicity, our study finds support from several studies which corroborate that inhibitors of EGFR-TKD and mABs show dual toxicity, tubular disorders, and glomerulopathies (Izzedine & Perazella, 2017) erlotinib itself is a hepatotoxic molecule (Kim et al., 2018). Besides non-covalent inhibitors, the covalent inhibitors against EGFR-TKD showed mutations and are more toxic than non-covalent molecules. The cardio-toxicity showed by osimertinib, a third-generation drug molecule was compared with standard TKIs that showed a higher rate of toxicity (Zhong et al., 2021). The toxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors states that there is an urgency for small molecules which have multi-faceted biological properties and are safe. Our research addresses the toxicity of newly synthesized derivatives and observed the molecular interplay with EGFR-TKD through computational modes. We found a safe drug molecule (derivative 17) from the present series whose 1H NMR spectra were assigned multiplets peaks to three non-equivalent methylene groups. Three different methine protons are assigned as one singlet and two doublets. The eight aromatic protons resonate as four doubles. The angular –OH protons are assigned as broad singlets. The synthesized derivative showed one singlet for methoxy protons and a broad singlet for phenolic –OH proton respectively (Figure S1). The molecular ion peaks m/z (relative intensity) [M + H]+ of the compound appear at 438.1. The LC-MS spectrum showed peaks are in conformity with their proposed structures (Figure S3).

A literature survey reveals the dimerization of EGFR-TKD via ligand-driven activation does not provide a complete understanding of tumorgenicity (Luwor et al., 2004) and remains unclear from the previous studies (Guo et al., 2015). The ligand bindings with EGFR-TKD have effective EGFR-TKD inhibition potency. Mutational events that occurred in EGFR-TKD and toxicities caused by first to third-generation drugs (Anand et al., 2019) could be revisited and forecast the essential ligand-driven bindings. The number of complications that had been shown by 1st – 3rd generations drugs are skin rashes, vomiting, diarrhea, and hepatotoxicity and cardiotoxicty among treated patients (Zhong et al., 2021) and stumbling the expectancy of life. The small molecules are in great progress and still face challenges, low response, and drug resistance (Niederst et al., 2015). The unsuitability of ligand cause mutations and further major drawbacks in chemotherapy. Organic synthesis and newly designed molecular scaffolds were implemented to determine their suitability as an inhibitor against EGFR-TKD. The bindings of the lead molecule with EGFR-TKD showed good agreement with previous studies reported by (Stamos et al., 2002, Sangande et al., 2020). The synthetic compound showed suitable bindings and the best docking orientations in the binding site of EGFR-TKD. The binding score of synthesized ligands was found to be more negative than the erlotinib which determines the potency of the ligand towards the target and interactions were observed with MET:769 in the catalytical site of EGFR-TKD similar to erlotinib (Fig. 2c, Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the theoretical study provides a deep understanding of the quantitative nature of chemical species (Parr et al., 1999). The global electrophilicity was determined and calculate the electronegativity (χ) and the value was found to be 4.302 eV for erlotinib and for synthetic congener it was found to be 3.957 eV and the electrophilicity index (ω) was found to be 7.410 eV and 7.041 eV demonstrating the newly synthesized compound could be a future therapeutic agent (Fig. 1b, Table 2). The docking study was validated by molecular dynamics simulation (MDS) to understand the mechanistic insights into ligand-driven stability and conformational changes in a sampled simulated system (Salo-Ahen et al., 2021). The MDS was carried out for 100 ns. The trajectories were computed and the RMSD plots of both the synthetic congener and erlotinib showed comparable stability with EGFR-TKD for100ns of a simulation (Fig. 3). The Cα of the protein was taken to determine the structural conformations. The reference complex attains stability from the very initial step till the simulation course is over. The RMSD of Cα of synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD complex showed minor fluctuations observed at 40 – 45 ns in the first two replicas, whereas the third simulation replica attains conformational stability till 100 ns. Trajectories of both the ligand-bound complexes were compared with the Apo complex and minor changes in protein conformity were determined from MD simulation. The Cα RMSD data points indicate an alteration in trajectories of the Apo complex predicts that the binding of ligands achieved more stable conformations. The RMSF fluctuations of simulated proteins in an aqueous system were determined at the N and C terminus of each complex. The ROG determines the compactness of the EGFR-TKD and SASA identifies the folding of the protein in an aqueous system. The SASA and ROG of the Apo complex were compared with the values obtained from ligand-bound EGFR-TKD (Figure S4). This demonstrates the higher compactness found in each ligand-bound EGFR-TKD complex with suitable protein folding during simulations. The hydrogen bonds formed during simulations provide major insights into the stability of the ligand in the binding site of the receptor. The higher binding stability is by the higher number of hydrogen bonds formed with the receptor. The higher number of hydrogen bonds was formed by a synthetic compound with EGFR-TKD. (Figure S5). The pairwise residue motion was determined from distance in root mean square deviations in nm scale during simulations. The DCCM plot of the Apo complex of EGFR-TKD determines the pairwise residue motions during simulations from the initial to the final frame of simulation (0 & 100 ns frame). It was found that synthetic compound and erlotinib bound EGFR-TKD showed minor anti-correlations at the C-lobe, whereas the N-lobe of the Apo complex shows anti-correlation motions with complexes bound with ligands indicating the structural changes by ligand bindings (Figure S6). If the pairwise RMSD from the center of the diagonal is highly anti-correlated then the structure becomes unstable and hindrances may occur in ligand bindings (Qureshi et al., 2020). The principal component analysis was done to identify the motion of the EGFR-TKD with and without ligands (erlotinib and synthetic compound). The motions of the Apo complex were obtained after computing the eigenvectors and eigenvalue. The PCA modes determine the large-scale atomic motions of the sampled system (Amadei et al., 1993; Berendsen & Hayward, 2000). The N-lobe showed motions towards the hinge region of the EGFR-TKD in both Apo complex and synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD complex but the erlotinib bound EGFR-TKD showed compactness during simulations. The observed conformational changes may or may not be induced by the ligand bindings concluded from this study (Fig. 5). The synthetic compound bound EGFR-TKD showed conformational landscape values observed to be 13.5 kJ/mol of erlotinib bound TKD complex and Apo complex, and synthetic compound derivative 17 bound with EGFR-TKD showed 14 kJ/mol (Fig. 6). This enables to provide information on the conformational energy landscapes to a protein (Tamirat et al., 2019). The binding strength was identified by the MM-PBSA method. Frames of the last 20 ns of simulations were vigorously implemented to generate the free energy binding of synthetic compound and erlotinib. Erlotinib showed a higher ΔG bind than synthetic compound with EGFR-TKD (Table 3) and net energy decomposition analysis demonstrates most of the amino acid participates in energy decomposition (Fig. 7a). The cell death was detected by apoptosis using EtBr and AO staining techniques and morphological changes were visualized by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 7b). Further, this study could be helpful to design novel leads against EGFR-TKD.

6. Conclusion

Toxicity is a matter of concern among marketed drugs. Many tyrosine kinase inhibitors showed toxicity in clinical trials and therefore are unsuitable for cancer management. We developed thiazolo-[2,3-b]quinazolinone series via MDS & MAOs and were studied with EGFR-TKD by in silico methods. The structural conformations and residual motions over the simulation course were computed thrice to achieve the significance of MDS results. The derivative 17 attains stability in the binding site of EGFR-TKD till the end of the simulation period. The MMPBSA calculations demonstrated synthesized congener achieved parallel average free binding energy as exhibited by the reference molecule with TK. Further, this study was exaggerated to in vitro models to determine cell death by apoptosis assay using two cell models (MCF-7 & H-1299). Experimental results showed the newly synthesized molecule is a potent anti-cancer agent and achieved IC50 values of 6.4 and 14 μM against MCF-7 & H-1299 cell lines. Present findings concluded that synthetic compound are anticancer agents. This study needs more attention to evaluate synthetic compound against in vivo xenograft for its further efficacy to use as an anti-cancer agent.

7. Material and correspondence

The data set will be available upon the corresponding author’s request.

Authors contributions

SAM carried out Molecular docking, MD simulations, and Essential dynamics. SAM, RKM & IB carried out in-vitro study. PPM, AKB, & SAM study the properties of synthetic ligands. SAM prepared the initial draft; SAM, IB, MK, & BN edited the manuscript. All authors read and recommend the manuscript for publication & editorial processes. This work was done under the supervision of Dr. Binata Nayak.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103478.

Contributor Information

Showkat Ahmad Mir, Email: showkat@suniv.ac.in.

Prajna Paramita Mohanta, Email: prajnachem@suniv.ac.in.

Rajesh Kumar Meher, Email: rajeshmeher99@suniv.ac.in.

Iswar baitharu, Email: iswarbaitharu@suniv.ac.in.

Mukesh Kumar Raval, Email: mkraval@gmuniversity.ac.in.

Ajaya Kumar Behera, Email: ajaykumar.behera@suniv.ac.in.

Binata Nayak, Email: binatanayak@suniv.ac.in.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aier I., et al. Structural insights into conformational stability of both wild-type and mutant EZH2 receptor. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep34984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, AM. et al. 2014. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of some novel substituted quinazolines as antitumor agents.Eur. J. Med. Chem. 79, 446-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Allen B.K., et al. Large-scale computational screening identifies first-in-class multitarget inhibitor of EGFR kinase and BRD4. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep16924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amewu R.K., et al. Synthetic and naturally occurring heterocyclic anticancer compounds with multiple biological targets. Molecules. 2021;26:7134. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminpour M., et al. An overview of molecular modeling for drug discovery with specific illustrative examples of applications. Molecules. 2019;24:1693. doi: 10.3390/molecules24091693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand K., et al. Osimertinib-induced cardiotoxicity: a retrospective review of the FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS) Cardio. Oncol. 2019;1:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.10.006. https://www.jacc.org/doi/abs/10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes T.A. Third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2017;31:113. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S., et al. Phytochemical fidelity and therapeutic activity of micropropagated Curcuma amada Roxb.: A valuable medicinal herb. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022;176 doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker H., et al. In: PHYSICS COMPUTING '92. DeGroot R.A., Nadrchal J., editors. World Scientific Publishing; 1993. Gromacs - A Parallel Computer For Molecular-Dynamics Simulations; pp. 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J., et al. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1995;91:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J., Hayward S. Collective protein dynamics in relation to function. Current. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10(2):165–169. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., van Gunsteren W.F., DiNola A., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- Borkotoky S., Murali A. A computational assessment of pH-dependent differential interaction of T7 lysozyme with T7 RNA polymerase. BMC Struct. Biol. 2018;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12900-017-0077-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, MR., et al. 2013. Mechanism for activation of mutated epidermal growth factor receptors in lung cancer. PANS. Sep 17; 110, E3595-604. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1220050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brooks B.R., et al. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comp. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.S., et al. Mechanisms of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and strategies to overcome resistance in lung adenocarcinoma. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2016;79:248–256. doi: 10.4046/trd.2016.79.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier, M., et al. 2021. Oncogenic driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Past, present, and future. World J. Clin. Oncol. 12, 217. https://doi.org/10.5306%2Fwjco.v12.i4.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cohen M.H., et al. FDA drug approval summary: gefitinib (ZD1839) (Iressa®) tablets. The Oncologist. 2003;8(4):303–306. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅ log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J.D., McCammon J.A. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011;9(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed, S., Metwally, K., El-Shanawani, A.A., Abdel-Aziz, L.M., Pratsinis, H. and Kletsas, D., 2017. Synthesis and anticancer activity of novel quinazolinone-based rhodanines. Chemistry central journal, 11(1), pp.1-10. 10.1186/s13065-017-0333-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elkamhawy., A. et al. 2015. Targeting EGFR/HER2 tyrosine kinases with a new potent series of 6-substituted 4-anilinoquinazoline hybrids: Design, synthesis, kinase assay, cell-based assay, and molecular docking. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 5147-5154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Engelman J.A., Janne P.A. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non–small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14(10):2895–2899. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay, J. et al. 2021. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020 (https://gco.iarc.fr/today, accessed February.

- Gonda T.J., Ramsay R.G. Directly targeting transcriptional dysregulation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:686–694. doi: 10.1038/nrc4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G., et al. Ligand-independent EGFR signaling. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3436–13344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren., T. A. 1996. Merck molecular force field. 1. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comp. Chem.17, 490–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199604)17:5/6<490::AID-JCC1>3.0.CO;2-P.

- Hess B., et al. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comp. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199709)18:12%3C1463::AID-JCC4%3E3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzedine H., Perazella M.A. Adverse kidney effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017;32:1089–1097. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo., S. et al. 2008. CHARMM‐ GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 29, 1859-1865. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kashefolgheta S., Verde A.V. Developing force fields when experimental data is sparse: AMBER/GAFF-compatible parameters for inorganic and alkyl oxoanions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:20593–20607. doi: 10.1039/C7CP02557B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerru N., et al. A review on recent advances in nitrogen-containing molecules and their biological applications. Molecules. 2020;25:1909. doi: 10.3390/molecules25081909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. K., et al. (2018) Risk factors for erlotinib-induced hepatotoxicity: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Cancer, 18, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R., Kumar, R., Open Source Drug Discovery Consortium, & Lynn, A. 2014. g_mmpbsa A GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model. 54(7), 1951-1962. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindahl E., et al. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. Mol. Model. 2001;8:306–317. doi: 10.3390/molecules26237134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindorff‐Larsen, K., et al. 2010. Improved side‐chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 78, 1950-1958 https://doi.org/10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Luwor R.B., et al. The tumor-specific de2–7 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes cells survival and heterodimerizes with the wild-type EGFR. Oncogene. 2004;23:6095–6104. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark P., Nilsson L. Structure and dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E water models at 298K. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:9954–9960. doi: 10.1021/jp003020w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi M., et al. One-pot multi-component synthesis of new bis-pyridopyrimidine and bis-pyrimidoquinolone derivatives. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05047. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X.Y., et al. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. -Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metibemu D.S., et al. Exploring receptor tyrosine kinases-inhibitors in cancer treatments. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. 2019;20:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s43042-019-0035-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mir S.A., et al. In silico and in vitro evaluations of fluorophoric thiazolo-[2, 3-b] quinazolinones as anti-cancer agents targeting EGFR-TKD. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022;1–27 doi: 10.1007/s12010-022-03893-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir S.A., et al. Molecular dynamic simulation, free binding energy calculation of Thiazolo-[2, 3-b] quinazolinone derivatives against EGFR-TKD and their anticancer activity. Res. Chem. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2022.100418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanta P.P., et al. The construction of fluorophoric thiazolo-[2, 3-b] quinazolinone derivatives: a multicomponent domino synthetic approach. RSC Adv. 2020;10:15354–15359. doi: 10.1039/D0RA01066A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederst M.J., et al. The allelic context of the C797S mutation acquired upon treatment with third-generation EGFR inhibitors impacts sensitivity to subsequent treatment strategies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:3924–3933. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noser A.A., et al. Synthesis, in silico and in vitro assessment of new quinazolinones as anticancer agents via potential AKT inhibition. Molecules. 2020;25:4780. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Boyle N.M., et al. Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011;3:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda K., et al. A comprehensive pathway map of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2005;1:2005–10010. doi: 10.1038/msb4100014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmini R., et al. Identification of novel bioactive molecules from garlic bulbs: A special effort to determine the anticancer potential against lung cancer with targeted drugs. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020;27:3274–3289. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr R.G., et al. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1922–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Pathania S., et al. Role of sulfur-heterocycles in medicinal chemistry: an update. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;180:486–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patodia S., et al. Molecular dynamics simulation of proteins: a brief overview. J. Phys. Chem. & Biophys. 2014;4:1. doi: 10.4172/2161-0398.1000166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S. The importance of heterocyclic compounds in anti-cancer drug design. Drug Discovery. 2017;67 https://www.ddw-online.com/media/32/(8)-the-importance-of-heterocyclic.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G.R., et al. In silico analysis and molecular dynamics simulation of human superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3) genetic variants. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019;120:3583–3598. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires D.E., et al. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;9:4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi R., et al. (Correlated motions and dynamics in different domains of egfr with l858r and t790m mutations. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinformatics. 2020 doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2020.2995569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati A., Pashmforoush N. Synthesis of various heterocyclic compounds via multicomponent reactions in water. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2015;12:993–1036. doi: 10.1007/s13738-014-0562-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashad A.E., et al. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of some new pyrazole and fused pyrazolopyrimidine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:7102–7106. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo-Ahen O.M., et al. Molecular dynamics simulations in drug discovery and pharmaceutical development. Processes. 2021;9:71. doi: 10.3390/pr9010071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saluja, T. S., et al. 2020. Mitochondrial Stress–Mediated Targeting of Quiescent Cancer Stem Cells in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 4519. https://doi.org/10.2147%2FCMAR.S252292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sangande F., et al. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamic studies of dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR and VEGFR2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7779. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S., Datta D., Debbarma S., Majumdar G., Mandal S.S. Pattern of cancer incidence and mortality in North - Eastern India: the first report from the population based cancer registry of Tripura. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prevent. 2020:2493–2499. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.9.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist L.V. First-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in EGFR mutation; positive non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2008;3:S143–S145. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-3-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshacharyulu P., et al. Targeting the EGFR signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2012;16:15–31. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.648617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B., et al. Understanding the thermostability and activity of Bacillus subtilis lipase mutants: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys Chem. B. 2015;119:392–409. doi: 10.1021/jp5079554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa da Silva A.W., Vranken W.F. ACPYPE-Antechamber python parser interface. BMC Res. Notes. 2012;5:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spezia R., et al. The effect of protein conformational flexibility on the electronic properties of a chromophore. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2805–2813. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamos J., Sliwkowski M.X., Eigenbrot C. Structure of the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase domain alone and in complex with a 4-anilinoquinazoline inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;48:46265–46272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m207135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamirat, MZ., et al. 2019. Structural characterization of EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation using molecular dynamics simulation. PloS one,1 4(9), e0222814. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Troiani, T., et al. 2012. Targeting EGFR in pancreatic cancer treatment. Curr. Drug Targets. Jun 1; 13 802-10. https://doi.org/10.2174/138945012800564158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Trott, O., & Olson., 2010. AutoDockVina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455-461 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang J., et al. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2006;25:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., et al. iCn3D a web-based 3D viewer for sharing 1D/2D/3D representations of biomolecular structures. J. Bioinform. 2019;36:131–135. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., et al. A review on flavones targeting serine/threonine protein kinases for potential anticancer drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;27:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L., Li Y., Xiong L., et al. Small molecules in targeted cancer therapy: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 2021;6:201. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00572-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.