Abstract

Fusarium head blight (FHB) is a destructive disease in wheat worldwide. Fusarium graminearum species complex (FGSC) is the main causal pathogen causing severe damage to wheat with reduction in both grain yield and quality. Additionally, mycotoxins produced by the FHB pathogens are hazardous to the health of human and livestock. Large numbers of genes conferring FHB resistance to date have been characterized from wheat and its relatives, and some of them have been widely used in breeding and significantly improved the resistance to FHB in wheat. However, the disease spreads rapidly and has been severe due to the climate and cropping system changes in the last decade. It is an urgent necessity to explore and apply more genes related to FHB resistant for wheat breeding. In this review, we summarized the genes with FHB resistance and mycotoxin detoxication identified from common wheat and its relatives by using forward- and reverse-genetic approaches, and introduced the effects of such genes and the genes with FHB resistant from other plant species, and host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) in enhancing the resistance to FHB in wheat. We also outlined the molecular rationale of the resistance and the application of the cloned genes for FHB control. Finally, we discussed the future challenges and opportunities in this field.

Keywords: wheat disease, Fusarium graminearum, Fusarium head blight, genetics, breeding

Introduction

Fusarium head blight (FHB), which is also known as head scab and ear blight, caused by Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph Gibberella zeae) species complex is a fungal disease responsible for severe yield losses and poor grain quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (Bai and Shaner, 2004; Xu and Nicholson, 2009). The pathogen also produces mycotoxins such as trichothecenes and zearalenone contaminating infected wheat grains, which are harmful to humans and animals (Chen et al., 2019). Due to the warm temperature, abundant rainfall, and maize/wheat and rice/wheat rotations, the disease has been frequent and severe for the last decade worldwide, especially in China (Bai et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2019).

The most effective and economical solution for reducing FHB damage is to identify genes related to FHB resistance and apply them to breed disease-resistant varieties. The resistance to FHB is quantitative in wheat and no immune genes have been found so far (Bai et al., 2018). To date, a substantial number of quantitative trait loci (QTL) or genes conferring FHB resistance have been reported (Liu et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2021). Previously, strategies and progress of wheat breeding for FHB resistance have been reviewed (Ma et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). Here, we summarize advances in wheat resistance to FHB with the main focus on the characterized genes related to FHB resistance and their function in genetic improvement for the FHB resistance in wheat.

Cloning resistance genes from common wheat using forward genetic approaches

Cloning and utilization of Fhb1

Of the hundreds of QTL identified for FHB resistance by molecular mapping in common wheat, Fhb1, a QTL located on the short arm of chromosome 3B with the largest explanation of phenotype variation, provides durable and stable resistance to FHB. Fhb1 candidate genes have been cloned recently using the map-based cloning approach. In 2016, a pore-forming toxin-like (PFT) gene was firstly cloned as the candidate of Fhb1 (Rawat et al., 2016). However, this gene was also found in some susceptible accessions without Fhb1 (Yang et al., 2005; He et al., 2018a; Jia et al., 2018). Before long, another gene named HRC or His was cloned as an Fhb1 candidate by two independent studies (Li et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019). HRC/His encoded histidine-rich calcium-binding protein located in the nucleus. In comparison to that in the susceptible lines (HRC/His-S), the gene in the resistant lines carrying Fhb1 (HRC/His-R) had a deletion in its genome, which is responsible for FHB resistance (Li et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019). The function of TaHRC was validated by using a BSMV-mediated gene editing system in Bobwhite and Everest (Chen et al., 2022a; Chen et al., 2022b).

It was recently found that HRC/His-S from Leymus chinensis (named LcHRC in the original article), which showed identical amino acid sequence to wheat HRC/His-S, bound calcium and zinc ion in vitro (Yang et al., 2020). Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings overexpressing LcHRC showed sensitivity to abscisic acid (ABA) (Yang et al., 2020). A protein that participates in heterochromatin silencing was identified as an LcHRC interactor through the screening of Arabidopsis yeast cDNA library (Yang et al., 2020). These results suggest a potential role of LcHRC in the regulation of genes involved in abiotic stress response. In wheat, HRC-S interacting proteins were identified through the screening of wheat yeast cDNA library (Chen et al., 2022b). One of the interactors, TaCAXIP4 [a cation exchanger (CAX)-interacting protein 4], was further validated to physically interact with HRC-S in planta (Chen et al., 2022b). The interaction with HRC-S suppressed TaCAXIP4-mediated calcium cation (Ca2+) transporting in yeast cells and resulted in reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) triggered by chitin (Chen et al., 2022b), leading to the hypothesis that Ca2+ signaling-mediated ROS burst is essential for wheat FHB resistance. However, the details on how HRC/His affects FHB resistance remain equivocal, and more efforts are needed to elucidate their biological function and the regulatory network they mediated in defense response.

In fact, Fhb1 locus has been widely used for FHB resistance breeding prior to the gene cloning. A large number of wheat varieties worldwide carried Fhb1 locus, which confers moderate FHB resistance with the reduction of at most 50% in FHB severity (Bai et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019), which further confirmed the solid role of this locus in FHB resistance.

Other resistance genes from common wheat

Besides Fhb1, many other QTL conferring FHB resistance of wheat have been reported, but the majority of their candidate genes remain unidentified. QFhb.mgb-2A, a major QTL located on chromosome 2A, was found in a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population, obtained by crossing an hexaploid line derived from a resistant cultivar Sumai3 and a susceptible durum cv. Saragolla (Giancaspro et al., 2016). Several genes, including Fatty Acyl-CoA Reductase 1, Wall-associated receptor kinase 2 (WAK2), Arginine decarboxylase, SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A member 3, and Ubiquitin thioesterase otubain genes, were detected in the QTL region (Gadaleta et al., 2019). The homeolog of WAK2 in common wheat, which was named TaWAK2A-800, was identified later as a positive regulator of wheat resistance to FHB (Guo et al., 2021). Knocking down TaWAK2A-800 in wheat using the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) method compromised FHB resistance, which may be attributed to the impaired defense pathway induced by chitin (Guo et al., 2021).

Cloning genes with FHB resistance or mycotoxin detoxication from wheat using reverse genetic approaches

Decades of efforts in plant immunity have led to the development of plant resistance gene pool and the understanding of the mechanisms of plant disease resistance. The completion of wheat genome sequencing provides great convenience for the identification of the homologs of resistance genes in wheat through genome-wide homologous sequence analysis. Moreover, a variety of omics methods including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics will aid in identifying wheat resistance genes. A number of reverse genetics techniques are applied subsequently to overexpress and/or knock out/knock down the identified genes with the aim to verify their function. The widely used approaches in wheat include clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-based genome editing, VIGS, and RNA interference (RNAi). They have been invaluable in analyzing gene function in wheat FHB resistance.

Genes with FHB resistance in wheat

Many classes of genes have been implicated in the resistance to FHB in wheat. One group of them is referred to as pathogenesis-related (PR) genes. Increased expression of PR genes is a hallmark of plant defense response to pathogen attack. Based on gene sequence homology, two wheat PR genes, encoding chitinase (PR3) and β‐1,3‐glucanase (PR2), respectively, have been separately overexpressed in wheat and enhanced FHB resistance was observed in greenhouse but not in the field when using inoculated corn kernels (Anand et al., 2003). In another study, transgenic wheat lines with overexpression of wheat α-1-purothionin gene (a PR gene) exhibited increased FHB resistance in the field condition when using the spaying inoculation method (Mackintosh et al., 2007).

The essential role of plant hormones in the disease resistance is also a global consensus. Several genes involved in wheat phytohormone biosynthesis or signaling have been identified for FHB resistance. EIN2 is a central regulator of ethylene (ET) signaling (Alonso et al., 1999). RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated EIN2 silencing in wheat (Travella et al., 2006) reduced FHB symptoms (Chen et al., 2009), implying that ET signaling may promote wheat susceptibility to F. graminearum. Likewise, auxin was also implicated in FHB susceptibility of wheat. The expression of an auxin receptor gene TaTIR1 was found to be downregulated during F. graminearum infection (Su et al., 2021). Knockdown of TaTIR1 in wheat using RNAi technology increased FHB resistance (Su et al., 2021).

In addition to phytohormones, wheat metabolites are also essential for FHB resistance. Using a metabolomics approach, a research group identified several genes conferring resistance to FHB, including TaACT encoding agmatine coumaroyl transferase (Kage et al., 2017a), TaLAC4 encoding laccase (Soni et al., 2020), and TaWRKY70 and TaNAC032 both encoding transcription factors (Kage et al., 2017b; Soni et al., 2021). These genes are all involved in the biosynthesis of hydroxycinnamic acid amides and phosphotidic acid, the major metabolites accumulated in wheat rachis after F. graminearum invasion. Suppressing the expression of these genes respectively using VIGS reduced FHB resistance.

Transcriptomics are powerful in identifying genes related to FHB resistance. Lots of genes whose expression are induced by F. graminearum have been identified by different methods, such as Genechips and RNA sequencing, and some of them have been validated to be effective in FHB control. A wheat orphan gene named T. aestivum Fusarium Resistance Orphan Gene (TaFROG), which is a taxonomically restricted gene specific to the grass subfamily Pooideae, was identified as an F. graminearum-responsive gene and promoted wheat resistance to FHB (Perochon et al., 2015). TaFROG encodes a protein with unknown function but binds to TaSnRK1α, which is a wheat α subunit of the Sucrose Non-Fermenting1 (SNF1)-Related Kinase1 and plays central roles in plant energy and stress signaling (Perochon et al., 2015). Another TaFROG interactor, T. aestivum NAC-like D1 (TaNACL-D1), which is a NAC [No apical meristem (NAM), Arabidopsis transcription activation factor (ATAF), Cup-shaped cotyledon (CUC)] transcription factor, was identified by using yeast two-hybrid screening (Perochon et al., 2019). TaNACL-D1 was also responsive to F. graminearum and enhanced wheat resistance to FHB with unclarified mechanisms (Perochon et al., 2019).

Plant lectins, a class of proteins binding reversibly to mono- or oligosaccharides, are often associated with biotic and abiotic responses. Wheat genes encoding lectins have been shown to improve FHB resistance. TaJRLL1 and Ta-JA1/TaJRL53 are two genes in wheat encoding jacalin-related lectins. Suppressing their expression in wheat separately using VIGS compromised the disease resistance to FHB, while overexpressing TaJRL53 in wheat enhanced FHB resistance (Ma et al., 2010a; Xiang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2021).

Other genes, including TaLRRK-6D encoding a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (Thapa et al., 2018), TaMPT encoding a mitochondrial phosphate transporter responsible for transporting inorganic phosphate (Pi) into the mitochondrial matrix (Malla et al., 2021), TaSAM encoding an S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase that catalyzes the transfer of methyl groups from SAM to a large variety of acceptor substrates (Malla et al., 2021), TaPIEP1 encoding transcription factor (Liu et al., 2011), and TaSHMT3A-1 encoding serine hydroxymethyltransferase (Hu et al., 2022), are also identified to contribute to FHB resistance.

The abovementioned genes with FHB resistance are listed in Table 1 . They varied enormously in gene products and biochemical functions. It seems that wheat utilizes extensive biological processes to defend against F. graminearum attack. As no immune genes were found in FHB resistance, a deep understanding of the signaling pathway mediated by these resistance genes will help to optimize wheat FHB resistance in breeding.

Table 1.

Genes identified with FHB resistance in various common wheat variety.

| Gene name | Wheat variety | Accession number | Gene products | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFT | Sumai3 | included in KX907434.1 a | pore-forming toxin-like protein | Rawat et al., 2016 |

| HRC | Sumai3 | MK450312 a | histidine-rich calcium-binding-protein | Su et al., 2019 |

| His | Wangshuibai | KX022629 a | histidine-rich calcium-binding-protein | Li et al., 2019 |

| TaWAK2A-800 | Chinese Spring | TraesCS2A02G071800 b | wall-associated kinase | Guo et al., 2021 |

| PR2 | Sumai3 | undisclosed | β‐1,3‐glucanase | Anand et al., 2003 |

| PR3 | Sumai3 | undisclosed | chitinase | Anand et al., 2003 |

| PR | Undisclosed | X70665.1 a | α-1-purothionin | Mackintosh et al., 2007 |

| TaEIN2 | Mercia | AL816731 a | endoplasmic reticulum membrane-localized Nramp homolog |

Travella et al., 2006

Chen et al., 2009 |

| TaTIR1 | Sumai 3 | TraesCS1A02G091300 b | putative auxin receptor | Su et al., 2021 |

| TaACT | Wuhan-1 | KT962210 a | agmatine coumaroyl transferase | Kage et al., 2017a |

| TaLAC4 | Sumai 3 | MT587562 a | laccase | Soni et al., 2020 |

| TaFROG | CM82036 | KR611570 a | orphan protein with unknown function | Perochon et al., 2015 |

| TaSnRK1α | CM82036, Xiaoyan 22 | KR611568 a , TraesCS1A02G350500 b | SNF1-related kinase 1 |

Perochon et al., 2015

Jiang et al., 2020 |

| TaJRLL1 | CM82036 | HQ317136 a | jacalin-related lectin | Xiang et al., 2011 |

| Ta-JA1/TaJRL53 | H4564, Chinese Spring |

AY372111 a | jacalin-related lectin |

Ma et al., 2010a

Chen et al., 2021 |

| TaLRRK-6D | Chinese Spring | TraesCS6D02G206100 b | receptor-like kinase | Thapa et al., 2018 |

| TaMPT | Chinese Spring | TraesCS5A02G236700 b | mitochondrial phosphate transporter | Malla et al., 2021 |

| TaSAM | Chinese Spring | TraesCS2A02G048600 b | methyltransferase | Malla et al., 2021 |

| TaSHMT3A-1 | Chinese Spring | TraesCS3A02G385600 b | serine hydroxymethyltransferase | Hu et al., 2022 |

| TaWRKY70 | Wuhan-1 | KU562861 a | WRKY transcription factor | Kage et al., 2017b |

| TaWRKY45 | Chinese spring | AB603888 a | WRKY transcription factor | Bahrini et al., 2011 |

| TaNAC032 | Sumai 3 | MT512636 a | NAC transcription factor | Soni et al., 2021 |

| TaPIEP1 | Shannong0431 | EF583940 a | ERF transcription factor |

Dong et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011 |

| TaNACL-D1 | CM82036 | MG701911 a | NAC transcription factor | Perochon et al., 2019 |

| TaUGT3 | Wangshuibai | FJ236328 a | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase |

Ma et al., 2010b; Pei, 2011

Chen, 2013 |

| TaUGT5 | Sumai 3 | TraesCS2B02G184000 b | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | Zhao et al., 2018 |

| TaUGT6 | Sumai 3 | TraesCS5B02G436300 b | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | He et al., 2020 |

|

Traes_2BS_

14CA35D5D |

Apogee | MK166044 a | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | Gatti et al., 2018 |

| TaABCC3 | CM82036 | KM458975 a , KM458976 a | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters | Walter et al., 2015 |

| TaPDR1 | Wangshuibai | FJ185035 a , FJ858380 a | pleiotropic drug resistance (PDR) type ABC transporter | Shang et al., 2009 |

| TaPDR7 | Ning 7840 | undisclosed | PDR type ABC transporter | Wang et al., 2016 |

| TaCYP72A | CM82036 | TraesCS3A01G532600 b | cytochrome P450 | Gunupuru et al., 2018 |

| TaLTP5 | Shannong 0431 | JQ652457 a | lipid transfer protein | Zhu et al., 2012 |

GenBank accession number (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/).

Ensembl Plants accession number (http://plants.ensembl.org/Triticum_aestivum/Info/Index).

Wheat genes whose products are targets of F. graminearum effectors

Plant pathogenic microbes always secrete proteins that act as effectors into host cells to evade or inhibit host immunity, leading to enhanced pathogen virulence and facilitated pathogen growth (Dou and Zhou, 2012). The secreted effectors bind host proteins to modify their native biological functions. Some of the host targets are key regulators of plant immunity and therefore could be deployed for disease control.

Secreted proteome of F. graminearum has been obtained, with the protein numbers varied in different studies (Yang et al., 2012; Rampitsch et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; Lowe et al., 2015). However, their host targets are largely unknown.

It has been found that F. graminearum produces orphan secretory proteins (OSPs), and one of them, Osp24, functions as an effector (Jiang et al., 2020). After being secreted into wheat cells, Osp24 binds wheat protein TaSnRK1α (Jiang et al., 2020). The binding by Osp24 accelerates TaSnRK1α degradation, which may suppress host defense responses including cell death and is thus beneficial for pathogen infection; however, physical interaction with TaFROG, a wheat orphan protein, prevents TaSnRK1α from degradation and helps in wheat defense (Jiang et al., 2020). The interplay between the two orphan genes, OSP24 and TaFROG, may be indicative of co-evolution of F. graminearum and the host wheat, and the distinctive defense response of wheat to F. graminearum.

Detoxication genes in wheat

The mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol (DON, a type B trichothecene) produced by the pathogen are toxic to humans and animals. They cause emesis, feed refusal, and even death (Eriksen and Pettersson, 2004). In addition, DON is considered as a virulence factor capable to facilitate disease spread on wheat (Proctor et al., 1995; Bai et al., 2002). F. graminearum deficient in DON biosynthesis was able to infect wheat spikelets but failed to spread in spikelets, thus causing diminished disease symptoms (Bai et al., 2002). Therefore, decreasing the amount of DON of wheat grain during pathogen infection is not only necessary for food security, but also one goal of breeding for FHB resistance.

Proteins encoded by various genes have been identified with the ability to detoxify DON ( Table 1 ). Among them, uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) have been widely reported to be able to detoxify DON through glucosylation. These enzymes transfer a glycosyl group from UDP-glucose to DON to conjugate DON into deoxynivalenol-3-O-glucose (D3G), which is nontoxic for animals. As DON can promote disease spreading, glucosylation of DON to D3G is an important plant defense mechanism. He et al. (2018b) systematically analyzed family-1 UGTs and identified 179 putative UGT genes in a reference genome of wheat, Chinese Spring. Among them, TaUGT3 (Ma et al., 2010b; Pei, 2011; Chen, 2013), TaUGT5 (Zhao et al., 2018), and TaUGT6 (He et al., 2020) were validated to be effective in reducing DON content in wheat. Wheat lines overexpressing the three genes respectively showed resistance to DON treatment and the resultant disease resistance to FHB, implying the potential of TaUGT as useful disease resistance genes in breeding for FHB resistance.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporters have been implicated in DON detoxication. They may export DON from the cytoplasm to reduce the damage caused by mycotoxin. TaABCC3, encoding an ABC transporter responsible for substance transport across cell membrane, was cloned from DON-treated wheat transcripts (Walter et al., 2015). Inhibition of TaABCC3 expression by VIGS increased wheat sensitivity to DON (Walter et al., 2015). However, the effect of TaABCC3 on FHB resistance was not analyzed. TaPDR1 and TaPDR7, two wheat genes encoding the pleiotropic drug resistance (PDR) subfamily of ABC transporters, were upregulated by DON treatment and F. graminearum infection; knockdown of TaPDR7 in wheat by VIGS compromised FHB resistance (Shang et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2016).

Cytochrome P450, membrane-bound enzymes that can perform several types of oxidation–reduction reactions, was also reported to possess the ability to catabolize DON (Ito et al., 2013). A wheat P450 gene, TaCYP72A, was found to be activated by DON treatment and F. graminearum infection (Gunupuru et al., 2018). Suppressing TaCYP72A through VIGS reduced wheat resistance to DON (Gunupuru et al., 2018). However, whether this gene confers FHB resistance is not identified.

Exploration and utilization of alien genes in Triticeae with FHB resistance

There are over 300 species classified under more than 20 genera in Triticeae (Dewey, 1984), which represent an invaluable gene pool for wheat improvement. The wild relatives of wheat are an important source for wheat improvement with FHB resistance. Many genes with FHB resistance have been identified and verified in vivo ( Table 2 ). They show unique features as well as shared characteristics with those identified in hexaploidy wheat.

Table 2.

Genes identified with FHB resistance in wheat relatives.

| Species | Gene name | Accession number | Gene products | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thinopyrum elongatum | Fhb7 | Tel7E01T1020600.1 a | glutathione S-transferase | Wang et al., 2020a |

| Hordeum vulgare | tlp-1 | AM403331 b | thaumatin-like protein | Mackintosh et al., 2007 |

| PR2 | M62907.1 b | β‐1,3‐glucanase | Mackintosh et al., 2007 | |

| HvWIN1 | KT946819 b | ethylene-responsive transcription factor | Kumar et al., 2016 | |

| HvLRRK-6H | MLOC_12033.1 c | receptor like kinase | Thapa et al., 2018 | |

| chitinase gene | M62904 b | chitinase | Shin et al., 2008 | |

| HvUGT13248 | GU170355 b | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | Schweiger et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Mandalà et al., 2019 | |

| HvUGT-10W1 | undisclosed | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | Xing et al., 2017 | |

| Brachypodium distachyon | Bradi5g03300 | Bradi5g03300 | uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase | Schweiger et al., 2013; Pasquet et al., 2016; Gatti et al., 2019 |

| BdCYP711A29 | Bradi1g75310 | cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | Changenet et al., 2021 | |

| Haynaldia villosa | CERK1-V | Dv07G125800 | chitin-recognition receptor | Fan et al., 2022 |

WheatOmics accession (http://wheatomics.sdau.edu.cn).

GenBank accession number (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/).

IPK Barley Blast Server (http://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/barley).

Genes from Thinopyrum

Of the QTL that showed a stable major effect on FHB resistance, Fhb7 was transferred from wheatgrass Thinopyrum (Fu et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2015), and was cloned recently using the map-based cloning approach (Wang et al., 2020a). Fhb7 was mapped to chromosome 7E of Th. elongatum (Fu et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2015). The underpinning gene of the locus was identified that encodes a glutathione S-transferase (GST) with the prominent ability to detoxify trichothecene toxins produced by the pathogens (Wang et al., 2020a). The expression of the gene was increased at the late stage of infection and was also induced by trichothecene treatment (Wang et al., 2020a), implying an active role of Fhb7 in the response to mycotoxins. How Fhb7 is regulated at the molecular level remains obscure and needs to be determined. This may help to increase the expression of Fhb7 in wheat cultivars for further enhanced FHB resistance. Notably, wheat lines with Fhb7 locus showed increased resistance to FHB without growth defect and yield penalty (Wang et al., 2020a), making Fhb7 a promising potential for wheat resistance breeding.

Genes from Hordeum vulgare

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) PR genes also contributed to FHB resistance. Transgenic wheat lines separately overexpressing barley tlp-1 and PR2 gene showed increased resistance to FHB (Mackintosh et al., 2007). Two other genes, HvWIN1 encoding a transcriptional regulator of cuticle biosynthetic genes and HvLRRK-6H encoding a leucine-rich receptor-like kinase, were identified as positive regulators of FHB resistance (Kumar et al., 2016; Thapa et al., 2018). Knockdown of the two genes individually by VIGS increased the disease severity of barley (Kumar et al., 2016; Thapa et al., 2018). Wheat lines overexpressing a barley chitinase gene improved wheat resistance to FHB (Shin et al., 2008).

UGT genes responsible for DON detoxication have also been identified in barley. HvUGT13248 played an effective role in DON detoxication when expressed in yeast (Schweiger et al., 2010), Arabidopsis (Shin et al., 2012), durum (Mandalà et al., 2019), and wheat (Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Mandalà et al., 2019). Wheat lines constitutively expressing HvUGT13248 showed improved FHB resistance (Li et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017; Mandalà et al., 2019).

Recombinant HvUGT-10W1 purified from bacterium cells inhibited hypha growth of F. graminearum in the PDA (potato/dextrose/agar) media. Furthermore, suppressing HvUGT-10W1 expression in a barley variety 10W1, which showed resistance to FHB, using the VIGS approach reduced the resistance to FHB (Xing et al., 2017), implying the positive role of HvUGT-10W1 in barley resistance to FHB.

Genes from Haynaldia villosa

CERK1-V (Dv07G125800), the chitin-recognition receptor of Haynaldia villosa, was recently cloned and introduced into wheat under the drive of maize ubiquitin promoter (Fan et al., 2022). The overexpression lines showed enhanced FHB resistance, implying that the perception of chitin is an important step to initiate FHB resistance. Therefore, it has potential to identify the genes involved in chitin signaling and develop them for FHB resistance.

Genes from Brachypodium distachyon

Brachypodium distachyon has been developed for FHB resistance analysis (Peraldi et al., 2011). Several genes from B. distachyon have been characterized by FHB resistance. Bradi5g03300 UGT gene has been introduced into B. distachyon Bd21-3 and the wheat variety Apogee, both of which are susceptible to FHB (Schweiger et al., 2013; Pasquet et al., 2016; Gatti et al., 2019). Enhanced resistance to FHB and strong reduction of DON content in infected spikes were observed in the transgenic lines. Promisingly, some of the transgenic lines with high Bradi5g03300 transcripts showed normal growth or phenotype compared with the wild type.

BdCYP711A29 (Bradi1g75310) encoding cytochrome P450 monooxygenase involved in orobanchol (one form of strigolactones) biosynthesis was identified to negatively regulate FHB resistance. Overexpression of BdCYP711A29 in B. distachyon increases susceptibility to FHB, while the TILLING mutants showed disease symptoms similar to those of the wild type (Changenet et al., 2021).

FHB resistance genes from plant species beyond Triticeae species

Genes from Arabidopsis thaliana

Arabidopsis has been exploited for the analysis of the scientific rationale of plant resistance to F. graminearum because the fungi can infect Arabidopsis flowers (Urban et al., 2002; Brewer and Hammond-Kosack, 2015). Many genes that have been identified from A. thaliana showed potential for resistance against these pathogenic fungi.

NPR1 is an ankyrin repeat-containing protein involved in the regulation of systemic acquired resistance. Wheat lines overexpressing NPR1 showed enhanced resistance to FHB (Makandar et al., 2006).

AtALA1 and AtALA7, two members of Arabidopsis P-type ATPases, contributes to plant resistance to DON through cellular detoxification of mycotoxins (Wang et al., 2021). They mediated the vesicle transport of toxins from the plasma membrane to vacuoles. Transgenic Arabidopsis or maize plants overexpressing AtALA1 enhanced resistance to DON and disease caused by F. graminearum. It remains unknown whether AtALA1 homologous genes exist in wheat genome and have the same detoxification function.

Genes from rice and maize

F. graminearum also infects other crops, such as rice (Oryza sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.). In rice plants, a UGT OsUGT79 expressed and purified from bacterium cells was reported to be effective in conjugating DON into D3G in vitro (Michlmayr et al., 2015; Wetterhorn et al., 2017) and could be used as a promising candidate for FHB resistance breeding. Additionally, overexpression of rice PR5 gene encoding thaumatin‐like protein in wheat reduced FHB symptoms (Chen et al., 1999).

In maize, RIP gene b-32 encoding ribosome inactive protein promotes FHB resistance when overexpressed in wheat (Balconi et al., 2007).

Host-induced and spray-induced gene silencing of genes in Fusarium graminearum

Host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) was recently developed to control fungal diseases, in which transgenic host plants produce small interference RNAs (siRNAs) that match important genes of the invading pathogen to silence fungal genes during infection (Machado et al., 2018). Koch et al. (2013) reported that detached leaves of both transgenic Arabidopsis and barley plants expressing double-stranded RNA from cytochrome P450 lanosterol C-14a-demethylase genes exhibited resistance to F. graminearum. HIGS transgenic wheat targeting the chitin synthase 3b also confers resistance to FHB (Cheng et al., 2015). HIGS targeting multiple genes involving FgSGE1, FgSTE12, and FgPP1 of the fungus is effective and can be used as an alternative approach for developing FHB- and mycotoxin-resistant crops (Wang et al., 2020b).

Spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS), mechanistically similar to HIGS, is also effective to fungal disease control. In this approach, sprayed siRNAs or noncoding double-stranded (ds)RNAs onto plant surfaces targeting key genes of pathogens are taken up by the pathogens and in turn inhibit pathogen gene expression, leading to inhibited pathogen growth in plants (Koch et al., 2016; Song et al., 2018). SIGS targeting F. graminearum genes has been reported to effectively inhibit the pathogen growth in barley, providing the potential for FHB control (Koch et al., 2019; Werner et al., 2020; Rank and Koch, 2021).

Challenges and perspectives

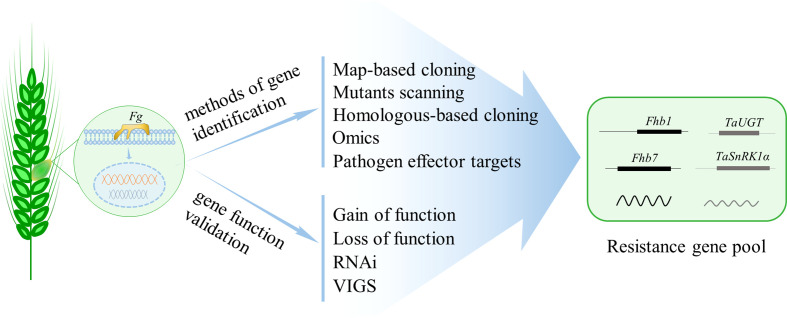

Compared with agronomic practices, chemical control, and biological control, genetic resistance is the best and most cost-effective strategy that could provide meaningful, consistent, and durable FHB control (Shude et al., 2020). There are variations in the susceptibility of different host plant species to FHB; however, no wheat varieties possess immunity against FHB (Dweba et al., 2017). Though hundreds of QTL have been reported in wheat, only two, Fhb1 and Fhb7, have been cloned through years of hard work (Rawat et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Su et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020a); thus, the FHB resistance genes that can be used for breeding is obviously limited. How to improve FHB resistance to a high level in wheat using the limited genes is a fundamental ongoing challenge. Pyramiding resistance genes to increase FHB resistance is feasible and popularized. However, the strategy is highly dependent on the adequate resistance genes. The majority of the QTL identified usually show a minor effect on FHB resistance and have no diagnostic markers. Therefore, sustained and continuous efforts are still needed in cloning and validating resistance genes from hundreds of QTL associated with FHB resistance in wheat. The integration of various forward- and reverse-genetic approaches will be an important means to explore the genes of FHB resistance in wheat, with the development of plant–pathogen interaction mechanism in model plants ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Methods to identify and validate genes that show resistance to Fusarium graminearum (Fg) and compose the resistance gene pool for wheat FHB resistance breeding. Map-based cloning and mutants scanning are two widely used approaches in gene identifying, while the latter is rarely applied in the analysis of wheat FHB resistance partially due to the functional redundancy among homeologs in polyploid wheat. With the completion of wheat genome sequencing, the popularized reverse-genetic approaches such as homologous-based cloning and omics technology are capable of identifying FHB resistance genes. Additionally, identifying the targets of pathogen effectors is also effective in wheat resistance gene identification. Finally, various gene gain- or loss-of-function technologies, or gene knockdown approaches such as RNAi and VIGS, are applicable to validate gene function in wheat FHB resistance.

In contrast to FHB resistance genes, modification of the susceptibility (S) genes will be an alternative option for controlling FHB. S factors or resistance suppressors have already been located on different chromosomes in wheat, yet, to date, they have not received much attention (Ma et al., 2006). In plants, some host factors encoded by S genes are always hijacked by pathogens through the secreted effectors to promote disease development. Mutations of these S genes evade the manipulation by pathogens and have been successfully utilized in crop disease control including wheat resistance to fungal pathogen (Garcia-Ruiz et al., 2021; Koseoglou et al., 2022). As secreted proteome of F. graminearum has been obtained, in depth analysis of the interaction between host and F. graminearum would facilitate the understanding of the function of S genes in wheat. Genes encoding resistance suppressors that always inhibit plant immune responses fall into another category of S genes (Garcia-Ruiz et al., 2021; Koseoglou et al., 2022). Mutations of these genes with abolished or reduced gene expression generally result in enhanced and durable disease resistance. These genes are significant components of crop disease resistance gene pool, while in FHB resistance, no such genes have been isolated so far. With the development of wheat mutant libraries, identification of such S genes will be facilitated.

Though some genes with FHB resistance have been identified, the signaling pathway that wheat perceives and responds to F. graminearum attack remains obscure. Plant immunity involves large-scale changes in gene expression. Intensive investigation of the role of those genes responsive to F. graminearum in wheat FHB resistance will contribute to the cloning of practical resistance genes. With the completion of wheat genome sequencing, the initiation of pan-genomic research for tribe Triticeae, and the rapid development in biotechniques, breakthrough will be made in the field in the future.

Author contributions

HGM and HXM wrote the manuscript. YL, XZ and SZ collected some data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangsu Key Project for the Research and Development (BE2022337) and the Seed Industry Revitalization Project of Jiangsu Province (JBGS2021047).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alonso J., Hirayama T., Roman G., Nourizadeh S., Ecker J. (1999). EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in arabidopsis. Science 284, 2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A., Zhou T., Trick H., Gill B., Bockus W., Muthukrishnan S. (2003). Greenhouse and field testing of transgenic wheat plants stably expressing genes for thaumatin-like protein, chitinase and glucanase against fusarium graminearum. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 1101–1111. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahrini I., Sugisawa M., Kikuchi R., Ogawa T., Kawahigashi H., Ban T., et al. (2011). Characterization of a wheat transcription factor, TaWRKY45, and its effect on fusarium head blight resistance in transgenic wheat plants. Breed. Sci. 61, 121–129. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs.61.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Desjardins A., Plattner R. (2002). Deoxynivalenol-nonproducing fusarium graminearum causes initial infection, but does not cause disease spread in wheat spikes. Mycopathologia 153, 91–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1014419323550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Shaner G. (2004). Management and resistance in wheat and barley to fusarium head blight. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42, 135–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Su Z., Cai J. (2018). Wheat resistance to fusarium head blight. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 40, 336–346. doi: 10.1080/07060661.2018.1476411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balconi C., Lanzanova C., Conti E., Triulzi T., Forlani F., Cattaneo M., et al. (2007). Fusarium head blight evaluation in wheat transgenic plants expressing the maize b-32 antifungal gene. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 117, 129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10658-006-9079-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer H. C., Hammond-Kosack K. E. (2015). Host to a stranger: Arabidopsis and fusarium ear blight. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changenet V., Macadré C., Boutet-Mercey S., Magne K., Januario M., Dalmais M., et al. (2021). Overexpression of a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase involved in orobanchol biosynthesis increases susceptibility to fusarium head blight. Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.662025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. (2013). Research on transformation of wheat resistance-related genes TaUGT3 and TaPRP to fusarium head blight into common wheat (Nanjing, China, Nanjing Agricultural University; ). [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Chen P., Liu D., Kynast R., Friebe B., Velazhahan R., et al. (1999). Development of wheat scab symptoms is delayed in transgenic wheat plants that constitutively express a rice thaumatin-like protein gene. Theor. Appl. Genet. 99, 755–760. doi: 10.1007/s001220051294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W., Song X. S., Li H. P., Cao L. H., Sun K., Qiu X. L., et al. (2015). Host-induced gene silencing of an essential chitin synthase gene confers durable resistance to fusarium head blight and seedling blight in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 1335–1345. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Kistler H. C., Ma Z. (2019). Fusarium graminearum trichothecene mycotoxins: Biosynthesis, regulation, and management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 57, 15–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082718-100318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Luo Y., Zhao P., Jia H., Ma Z. (2021). Overexpression of TaJRL53 enhances the fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Acta Agron. Sin. 47, 19–29. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2021.01050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Steed A., Travella S., Keller B., Nicholson P. (2009). Fusarium graminearum exploits ethylene signalling to colonize dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants. New Phytol. 182, 975–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Su Z., Tian B., Hao G., Trick H. N., Bai G. (2022. a). TaHRC suppresses the calcium-mediated immune response and triggers wheat head blight susceptibility. Plant Physiol. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiac352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Su Z., Tian B., Liu Y., Pang Y., Kavetskyi V., et al. (2022. b). Development and optimization of a barley stripe mosaic virus-mediated gene editing system to improve fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 20, 1018–1020. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey D. R. (1984). “The genomic system of classification as a guide to intergeneric hybridization with the perennial triticeae,” in Gene manipulation in plant improvement, vol. 209–279 . Ed. Guastafson J. P. (New York: Lenum Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Dong N., Liu X., Lu Y., Du L., Xu H., Liu H., et al. (2010). Overexpression of TaPIEP1, a pathogen-induced ERF gene of wheat, confers host-enhanced resistance to fungal pathogen bipolaris sorokiniana. Funct. Integr. Genomics 10, 215–226. doi: 10.1007/s10142-009-0157-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou D., Zhou J. M. (2012). Phytopathogen effectors subverting host immunity: different foes, similar battleground. Cell Host Microbe 12, 484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweba C. C., Figlan S., Shimelis H. A., Motaung T. E., Sydenham S., Mwadzingeni L., et al. (2017). Fusarium head blight of wheat: Pathogenesis and control strategies. Crop Prot. 91, 114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2016.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen G. S., Pettersson H. (2004). Toxicological evaluation of trichothecenes in animal feed. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 114, 205–239. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2003.08.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan A., Wei L., Zhang X., Liu J., Sun L., Xiao J., et al. (2022). Heterologous expression of the haynaldia villosa pattern-recognition receptor CERK1-V in wheat increases resistance to three fungal diseases. Crop J. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2022.02.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Lv Z., Qi B., Guo X., Li J., Liu B., et al. (2012). Molecular cytogenetic characterization of wheat–thinopyrum elongatum addition, substitution and translocation lines with a novel source of resistance to wheat fusarium head blight. J. Genet. Genomics 39, 103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadaleta A., Colasuonno P., Giove S. L., Blanco A., Giancaspro A. (2019). Map-based cloning of QFhb.mgb-2A identifies a WAK2 gene responsible for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Sci. Rep. 9, 6929. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43334-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ruiz H., Szurek B., Van den Ackerveken G. (2021). Stop helping pathogens: engineering plant susceptibility genes for durable resistance. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 70, 187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2021.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti M., Cambon F., Tassy C., Macadre C., Guerard F., Langin T., et al. (2019). The brachypodium distachyon UGT Bradi5gUGT03300 confers type II fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Plant Pathol. 68, 334–343. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti M., Choulet F., Macadré C., Guérard F., Seng J. M., Langin T., et al. (2018). Identification, molecular cloning, and functional characterization of a wheat UDP-glucosyltransferase involved in resistance to fusarium head blight and to mycotoxin accumulation. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancaspro A., Giove S. L., Zito D., Blanco A., Gadaleta A. (2016). Mapping QTL for fusarium head blight resistance in an interspecific wheat population. Front. Plant Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunupuru L. R., Arunachalam C., Malla K. B., Kahla A., Perochon A., Jia J., et al. (2018). A wheat cytochrome P450 enhances both resistance to deoxynivalenol and grain yield. PLoS One 13, e0204992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Wu T., Xu G., Qi H., Zhu X., Zhang Z. (2021). TaWAK2A-800, a wall-associated kinase, participates positively in resistance to fusarium head blight and sharp eyespot in wheat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11493. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Zhang X., Hou Y., Cai J., Shen X., Zhou T., et al. (2015). High-density mapping of the major FHB resistance gene Fhb7 derived from thinopyrum ponticum and its pyramiding with Fhb1 by marker-assisted selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 2301–2316. doi: 10.1007/s00122-015-2586-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Ahmad D., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Wu L., Jiang P., et al. (2018. b). Genome-wide analysis of family-1 UDP glycosyltransferases (UGT) and identification of UGT genes for FHB resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum l.). BMC Plant Biol. 18, 67. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1286-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Wu L., Liu X., Jiang P., Yu L., Qiu J., et al. (2020). TaUGT6, a novel UDP-glycosyltransferase gene enhances the resistance to FHB and DON accumulation in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.574775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Ahmad D., Wu L., Jiang P., et al. (2018. a). Molecular characterization and expression of PFT, an FHB resistance gene at the Fhb1 QTL in wheat. Phytopathology 108, 730–736. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-17-0383-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P., Song P., Xu J., Wei Q., Tao Y., Ren Y., et al. (2022). Genome-wide analysis of serine hydroxymethyltransferase genes in triticeae species reveals that TaSHMT3A-1 regulates fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.847087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Sato I., Ishizaka M., Yoshida S., Koitabashi M., Yoshida S., et al. (2013). Bacterial cytochrome P450 system catabolizing the fusarium toxin deoxynivalenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 1619–1628. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03227-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Hei R., Yang Y., Zhang S., Wang Q., Wang W., et al. (2020). An orphan protein of fusarium graminearum modulates host immunity by mediating proteasomal degradation of TaSnRK1α. Nat. Commun. 11, 4382. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18240-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Zhou J., Xue S., Li G., Yan H., Ran C., et al. (2018). A journey to understand wheat fusarium head blight resistance in the Chinese wheat landrace wangshuibai. Crop J. 6, 48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2017.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kage U., Karre S., Kushalappa A. C., McCartney C. (2017. a). Identification and characterization of a fusarium head blight resistance gene TaACT in wheat QTL-2DL. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 447–457. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kage U., Yogendra K. N., Kushalappa A. C. (2017. b). TaWRKY70 transcription factor in wheat QTL-2DL regulates downstream metabolite biosynthetic genes to resist fusarium graminearum infection spread within spike. Sci. Rep. 7, 42596. doi: 10.1038/srep42596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Biedenkopf D., Furch A., Weber L., Rossbach O., Abdellatef E., et al. (2016). An RNAi-based control of fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005901. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Höfle L., Werner B. T., Imani J., Schmidt A., Jelonek L., et al. (2019). SIGS vs HIGS: a study on the efficacy of two dsRNA delivery strategies to silence fusarium FgCYP51 genes in infected host and non-host plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 20, 1636–1644. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Kumar N., Weber L., Keller H., Imani J., Kogel K. H. (2013). Host-induced gene silencing of cytochrome P450 lanosterol C14 alphademethylase-encoding genes confers strong resistance to fusarium species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 19324–19329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306373110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koseoglou E., van der Wolf J. M., Visser R. G. F., Bai Y. (2022). Susceptibility reversed: modified plant susceptibility genes for resistance to bacteria. Trends Plant Sci. 27, 69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Yogendra K. N., Karre S., Kushalappa A. C., Dion Y., Choo T. M. (2016). WAX INDUCER1 (HvWIN1) transcription factor regulates free fatty acid biosynthetic genes to reinforce cuticle to resist fusarium head blight in barley spikelets. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 4127–4139. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Michlmayr H., Schweiger W., Malachova A., Shin S., Huang Y., et al. (2017). A barley UDP-glucosyltransferase inactivates nivalenol and provides fusarium head blight resistance in transgenic wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 2187–2197. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Shin S., Heinen S., Dill-Macky R., Berthiller F., Nersesian N., et al. (2015). Transgenic wheat expressing a barley UDP-glucosyltransferase detoxifies deoxynivalenol and provides high levels of resistance to fusarium graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28, 1237–1246. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-15-0062-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Cai S., Zhang B., Zhou M., Zhang Z. (2011). Molecular detection and identification of TaPIEP1 transgenic wheat with enhanced resistance to sharp eyespot and fusarium head blight. Acta Agron. Sin. 37, 1144–1150. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2011.01144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Hall M. D., Griffey C. A., McKendry A. L. (2009). Meta-analysis of QTL associated with fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Crop Sci. 49, 1955–1968. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.03.0115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Zhou J., Jia H., Gao Z., Fan M., Luo Y., et al. (2019). Mutation of a histidine-rich calcium-binding-protein gene in wheat confers resistance to fusarium head blight. Nat. Genet. 51, 1106–1112. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0426-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe R. G., McCorkelle O., Bleackley M., Collins C., Faou P., Mathivanan S., et al. (2015). Extracellular peptidases of the cereal pathogen fusarium graminearum. Front. Plant Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Bai G., Gill B., Patrick H. (2006). Deletion of a chromosome arm altered wheat resistance to fusarium head blight and deoxynivalenol accumulation in Chinese spring. Plant Dis. 90, 1545–1549. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado A. K., Brown N. A., Urban M., Kanyuka K., Hammond-Kosack K. E. (2018). RNAi as an emerging approach to control fusarium head blight disease and mycotoxin contamination in cereals. Pest Manage. Sci. 74, 790–799. doi: 10.1002/ps.4748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh C. A., Lewis J., Radmer L. E., Shin S., Heinen S. J., Smith L. A., et al. (2007). Overexpression of defense response genes in transgenic wheat enhances resistance to fusarium head blight. Plant Cell Rep. 26, 479–488. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0265-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makandar R., Essig J. S., Schapaugh M. A., Trick H. N., Shah J. (2006). Genetically engineered resistance to fusarium head blight in wheat by expression of arabidopsis NPR1. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19, 123–129. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla K. B., Thapa G., Doohan F. M. (2021). Mitochondrial phosphate transporter and methyltransferase genes contribute to fusarium head blight type II disease resistance and grain development in wheat. PLoS One 16, e0258726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandalà G., Tundo S., Francesconi S., Gevi F., Zolla L., Ceoloni C., et al. (2019). Deoxynivalenol detoxification in transgenic wheat confers resistance to fusarium head blight and crown rot diseases. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 32, 583–592. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-18-0155-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Shang Y., Cao A., Qi Z., Xing L., Chen P., et al. (2010. b). Molecular cloning and characterization of an up-regulated UDP-glucosyltransferase gene induced by DON from triticum aestivum l. cv. wangshuibai. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 785–795. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9606-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q., Tian B., Li Y. (2010. a). Overexpression of a wheat jasmonate-regulated lectin increases pathogen resistance. Biochimie 92, 187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Zhang X., Yao J., Cheng S. (2019). Breeding for the resistance to fusarium head blight of wheat in China. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 6, 251–264. doi: 10.15302/J-FASE-2019262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michlmayr H., Malachová A., Varga E., Kleinová J., Lemmens M., Newmister S., et al. (2015). Biochemical characterization of a recombinant UDP-glucosyltransferase from rice and enzymatic production of deoxynivalenol-3-O-β-D-glucoside. Toxins 7, 2685–2700. doi: 10.3390/toxins7072685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquet J. C., Changenet V., Macadré C., Boex-Fontvieille E., Soulhat C., Bouchabké-Coussa O., et al. (2016). A brachypodium UDP-glycosyltransferase confers root tolerance to deoxynivalenol and resistance to fusarium infection. Plant Physiol. 172, 559–574. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei H. (2011). Construction of the expression vector and transformation of TaUGT3 gene into common wheat (Nanjing, China, Nanjing Agricultural University; ). [Google Scholar]

- Peraldi A., Beccari G., Steed A., Nicholson P. (2011). Brachypodium distachyon: a new pathosystem to study fusarium head blight and other fusarium diseases of wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perochon A., Jianguang J., Kahla A., Arunachalam C., Scofield S. R., Bowden S., et al. (2015). TaFROG encodes a pooideae orphan protein that interacts with SnRK1 and enhances resistance to the mycotoxigenic fungus fusarium graminearum. Plant Physiol. 169, 2895–2906. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perochon A., Kahla A., Vranić M., Jia J., Malla K. B., Craze M., et al. (2019). A wheat NAC interacts with an orphan protein and enhances resistance to fusarium head blight disease. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1892–1904. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor R. H., Hohn T. M., McCormick S. P. (1995). Reduced virulence of gibberella zeae caused by disruption of a trichothecene toxin biosynthetic gene. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 8, 593–601. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampitsch C., Day J., Subramaniam R., Walkowiak S. (2013). Comparative secretome analysis of fusarium graminearum and two of its non-pathogenic mutants upon deoxynivalenol induction in vitro . Proteomics 13, 1913–1921. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rank A. P., Koch A. (2021). Lab-To-field transition of RNA spray applications–how far are we? Front. Plant Sci. 12. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.755203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat N., Pumphrey M. O., Liu S., Zhang X., Tiwari V. K., Ando K., et al. (2016). Wheat Fhb1 encodes a chimeric lectin with agglutinin domains and a pore-forming toxin-like domain conferring resistance to fusarium head blight. Nat. Genet. 48, 1576–1580. doi: 10.1038/ng.3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger W., Boddu J., Shin S., Poppenberger B., Berthiller F., Lemmens M., et al. (2010). Validation of a candidate deoxynivalenol-inactivating UDP-glucosyltransferase from barley by heterologous expression in yeast. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 977–986. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-7-0977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweiger W., Pasquet J. C., Nussbaumer T., Paris M. P., Wiesenberger G., Macadré C., et al. (2013). Functional characterization of two clusters of brachypodium distachyon UDP-glycosyltransferases encoding putative deoxynivalenol detoxification genes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26, 781–792. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-12-0205-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Xiao J., Ma L., Wang H., Qi Z., Chen P., et al. (2009). Characterization of a PDR type ABC transporter gene from wheat (Triticum aestivum l.). Chin. Sci. Bull. 54, 3249–3257. doi: 10.1007/s11434-009-0553-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S., Mackintosh C. A., Lewis J., Heinen S. J., Radmer L., Dill-Macky R., et al. (2008). Transgenic wheat expressing a barley class II chitinase gene has enhanced resistance against fusarium graminearum. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2371–2378. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S., Torres-Acosta J. A., Heinen S. J., McCormick S., Lemmens M., Paris M. P., et al. (2012). Transgenic arabidopsis thaliana expressing a barley UDP-glucosyltransferase exhibit resistance to the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 4731–4740. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shude S. P. N., Yobo K. S., Mbili N. C. (2020). Progress in the management of fusarium head blight of wheat: An overview. S. Afr. J. Sci. 116, 7854. doi: 10.17159/sajs.2020/7854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song X. S., Gu K. X., Duan X. X., Xiao X. M., Hou Y. P., Duan Y. B., et al. (2018). Secondary amplification of siRNA machinery limits the application of spray-induced gene silencing. Mol. Plant Pathol. 19, 2543–2560. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni N., Altartouri B., Hegde N., Duggavathi R., Nazarian-Firouzabadi F., Kushalappa A. C. (2021). TaNAC032 transcription factor regulates lignin-biosynthetic genes to combat fusarium head blight in wheat. Plant Sci. 304, 110820. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni N., Hegde N., Dhariwal A., Kushalappa A. C. (2020). Role of laccase gene in wheat NILs differing at QTL-Fhb1 for resistance against fusarium head blight. Plant Sci. 298, 110574. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Bernardo A., Tian B., Chen H., Wang S., Ma H., et al. (2019). A deletion mutation in TaHRC confers Fhb1 resistance to fusarium head blight in wheat. Nat. Genet. 51, 1099–1105. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0425-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su P., Zhao L., Li W., Zhao J., Yan J., Ma X., et al. (2021). Integrated metabolo-transcriptomics and functional characterization reveals that the wheat auxin receptor TIR1 negatively regulates defense against fusarium graminearum. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 340–352. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa G., Gunupuru L. R., Hehir J. G., Kahla A., Mullins E., Doohan F. M. (2018). A pathogen-responsive leucine rich receptor like kinase contributes to fusarium resistance in cereals. Front. Plant Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travella S., Klimm T. E., Keller B. (2006). RNA Interference-based gene silencing as an efficient tool for functional genomics in hexaploid bread wheat. Plant Physiol. 142, 6–20. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban M., Daniels S., Mott E., Hammond-Kosack K. (2002). Arabidopsis is susceptible to the cereal ear blight fungal pathogens fusarium graminearum and fusarium culmorum. Plant J. 32, 961–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter S., Kahla A., Arunachalam C., Perochon A., Khan M. R., Scofield S. R., et al. (2015). A wheat ABC transporter contributes to both grain formation and mycotoxin tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2583–2593. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Hou W., Zhang L., Wu H., Zhao L., Du X., et al. (2016). Functional analysis of a wheat pleiotropic drug resistance gene involved in fusarium head blight resistance. J. Integr. Agric. 15, 2215–2227. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61362-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Li X., Li Y., Han J., Chen Y., Zeng J., et al. (2021). Arabidopsis P4 ATPase-mediated cell detoxification confers resistance to fusarium graminearum and verticillium dahliae. Nat. Commun. 12, 6426. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26727-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Sun S., Ge W., Zhao L., Hou B., Wang K., et al. (2020. a). Horizontal gene transfer of Fhb7 from fungus underlies fusarium head blight resistance in wheat. Science 368, eaba5435. doi: 10.1126/science.aba5435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wu L., Mei Y., Zhao Y., Ma Z., Zhang X., et al. (2020. b). Host-induced gene silencing of multiple genes of fusarium graminearum enhances resistance to fusarium head blight in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 2373–2375. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner B. T., Gaffar F. Y., Schuemann J., Biedenkopf D., Koch A. M. (2020). RNA-Spray-mediated silencing of fusarium graminearum AGO and DCL genes improve barley disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetterhorn K. M., Gabardi K., Michlmayr H., Malachova A., Busman M., McCormick S. P., et al. (2017). Determinants and expansion of specificity in a trichothecene UDP-glucosyltransferase from oryza sativa. Biochemistry 56, 6585–6596. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Song M., Wei Z., Tong J., Zhang L., Xiao L., et al. (2011). A jacalin-related lectin-like gene in wheat is a component of the plant defence system. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 5471–5483. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L., He L., Xiao J., Chen Q., Li M., Shang Y., et al. (2017). An UDP-glucosyltransferase gene from barley confers disease resistance to fusarium head blight. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 35, 224–236. doi: 10.1007/s11105-016-1014-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Nicholson P. (2009). Community ecology of fungal pathogens causing wheat head blight. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 83–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Bai G., Shaner G. E. (2005). Novel quantitative trait loci (QTL) for fusarium head blight resistance in wheat cultivar chokwang. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111, 1571–1579. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0087-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Jacobsen S., Jørgensen H. J., Collinge D. B., Svensson B., Finnie C. (2013). Fusarium graminearum and its interactions with cereal heads: Studies in the proteomics era. Front. Plant Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Jensen J. D., Svensson B., Jørgensen H. J., Collinge D. B., Finnie C. (2012). Secretomics identifies fusarium graminearum proteins involved in the interaction with barley and wheat. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 445–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00759.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Zhang T., Mao H., Jin H., Sun Y., Qi Z. (2020). A leymus chinensis histidine-rich Ca2+-binding protein binds Ca2+/Zn2+ and suppresses abscisic acid signaling in arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 252, 153209. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Ma X., Su P., Ge W., Wu H., Guo X., et al. (2018). Cloning and characterization of a specific UDP-glycosyltransferase gene induced by DON and fusarium graminearum. Plant Cell Rep. 37, 641–652. doi: 10.1007/s00299-018-2257-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng T., Hua C., Li L., Sun Z., Yuan M., Bai G., et al. (2021). Integration of meta-QTL discovery with omics: towards a molecular breeding platform for improving wheat resistance to fusarium head blight. Crop J. 9, 739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2020.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Hao Y., Mergoum M., Bai G., Humphreys G., Cloutier S., et al. (2019). Breeding wheat for resistance to fusarium head blight in the global north: China, USA and Canada. Crop J. 7, 730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2019.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Li Z., Xu H., Zhou M., Du L., Zhang Z. (2012). Overexpression of wheat lipid transfer protein gene TaLTP5 increases resistances to cochliobolus sativus and fusarium graminearum in transgenic wheat. Funct. Integr. Genomics 12, 481–488. doi: 10.1007/s10142-012-0286-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]