Abstract

Purpose of research

The potential for cartilage repair using articular cartilage derived chondroprogenitors has recently gained popularity due to promising results from in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Translation of results from in-vitro to a clinical setting requires a sufficient number of animal studies displaying significant positive outcomes. Thus, this systematic review comprehensively discusses the available literature (January 2000–March 2022) on animal models employing chondroprogenitors for cartilage regeneration, highlighting the results and limitations associated with their use.

As per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, a web-based search of PubMed and SCOPUS databases was performed for the following terminologies: “chondroprogenitors”, “cartilage-progenitors”, and “chondrogenic-progenitors”, which yielded 528 studies. A total of 12 studies met the standardized inclusion criteria, which included chondroprogenitors derived from hyaline cartilage isolated using fibronectin adhesion assay (FAA) or migratory assay from explant cultures, further analyzing the role of chondroprogenitors using in-vivo animal models.

Principal results

Analysis revealed that FAA chondroprogenitors demonstrated the ability to attenuate osteoarthritis, repair chondral defects and form stable cartilage in animal models. They displayed better outcomes than bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells but were comparable to chondrocytes. Migratory chondroprogenitors also demonstrated superiority to BM-MSCs in terms of higher chondrogenesis and lower hypertrophy, although a direct comparison to FAA-CPs and other cell types is warranted.

Major conclusions

Chondroprogenitors exhibit superior properties for chondrogenic repair; however, limited data on animal studies necessitates further studies to optimize their use before clinical translation for neo-cartilage formation.

Keywords: Chondroprogenitors, Fibronectin, Migratory, Animal models, Chondrogenesis

Highlights

-

•

FAA Chondroprogenitors attenuated osteoarthritis progression.

-

•

FAA Chondroprogenitors repaired chondral defects.

-

•

FAA and Migratory chondroprogenitors superior to BM-MSCs.

-

•

Limited data on animal studies using chondroprogenitors.

1. Introduction

Hyaline articular cartilage has insufficient capacity for intrinsic repair and regeneration.1 It lacks blood vessels and nerve supply necessary for repair responses. When hyaline cartilage is damaged, it is replaced by scar tissue of fibrocartilage with inferior mechanical and functional properties.2 Currently, no surgical technique has successfully stimulated the formation of normal hyaline cartilage during articular cartilage repair. The success of cartilage repair is mainly dependent on the stage of the disease, size and extent of the lesion. The discovery of mouse embryonic stem cells in the early 1980s began the revolution in stem cell biology, which led to the tantalizing possibility of widespread clinical interventions.3 In the field of cartilage repair, the two most common cells used for cell-based therapy are chondrocytes and mesenchymal stem cells.4

Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) has been in clinical use in human patients since 1987 and has improved outcomes by producing durable cartilage-like tissue.5 Despite all the advances in ACI over the last few decades, the dedifferentiation of chondrocytes during monolayer expansion remains one of the main obstacles to successful cartilage transplantation.6,7 Similarly, using Bone Marrow derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (BM-MSCs) in cartilage repair, though reporting positive outcomes, display a higher propensity to form hypertrophic chondrocytes in both preclinical and clinical settings.8,9 In place of cartilage-specific proteoglycans and collagen type II, these cells produce matrix components that lack the biomechanical properties and the resilience of hyaline articular cartilage.

The search for an alternative cell source led to the discovery of chondroprogenitors (CPCs) within the articular cartilage as a potential candidate for cartilage repair. They have been characterized to possess an increased tendency towards chondrogenesis and minimal features of hypertrophy when compared to chondrocytes and BM-MSCs.10 Moreover, they have been likened to MSCs, as they conform to the minimal criteria for MSCs presented by the International Society for Cellular Therapy 2006.11 The nomenclature for CPCs has also been applied to cells isolated from non-hyaline sources such as synovium, meniscus, and infrapatellar fat pad, which also display potential chondrogenic ability. However, in this review, CPCs isolated from hyaline sources, namely articular cartilage, nasal septum and tracheal cartilage, were only considered as the end goal remains to be the regeneration of hyaline-like cartilage.

Historically, circumstantial evidence for appositional growth led Dowthwaite et al., 2004 first isolate CPCs using differential fibronectin adhesion assay (FAA).12 Later in 2008, Hayes et al. showed the presence of these bromodeoxyuridine label-retaining cells within the superficial zone of fetal cartilage.13 In addition to these early studies, further characterizing of FAA CPCs by Khan et al. and Williams et al. demonstrated that when compared to mature chondrocytes, these cells showed higher levels of the primary transcription factor: SRY box transcription factor 9 (SOX9), Notch homolog 1 (NOTCH1), and increased affinity for the fibronectin receptor along with enhanced telomerase activity.14,15 Furthermore, Koelling et al., in 2009 studied the potential role of CPCs in cartilage repair in response to cartilage injury by using explant cultures, investigating their homing and migratory ability in response to injury.16,17 Based on this method, progenitors with high migratory abilities also displayed high chondrogenic potential and similarities to MSCs. Another technique for selecting CPCs was based on the isolation of certain segregated subsets from a pool of chondrocytes using potential chondrogenic surface markers. The first study by Su et al., in 2015 showed that the final isolates (CD146+ cells subsets) using flow-assisted cell sorting technology (FACS) also demonstrated higher migratory and chondrogenic capacities.18

For the clinical application of CPCs, an assessment of their safety and efficacy is needed using preclinical models, such as osteoarthritis, chondral defects, osteochondral defects (OCD) and plain subcutaneous transplants. As per current literature, no human studies using CPCs have been registered yet. However, in the field of regenerative medicine for cartilage repair, approaches using CPCs have gained attention as novel sources for therapeutic application. This review article intends to comprehensively discuss the available literature on CPCs for cartilage regeneration in animal models, highlighting the achievements and limitations associated with their use. The collative information will help identify the current status, lacunae and provide information that could further accelerate the translation of CPCs into clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

The literature review was performed based on the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statements. This study searched Scopus and PubMed databases from January 2000 to September 2022. In light of the diverse nomenclature of CPCs, the search was performed separately for the following terminologies: “chondroprogenitors”, “cartilage-progenitors”, and “chondrogenic-progenitors".

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria included all studies published in the English language that analyzed the role of CPCs using an in-vivo model; isolated from hyaline cartilaginous tissue by one or more of the following approaches: a) FAA, b) migration of cartilage explants or c) cell sorting. Studies were excluded using cells derived from non-cartilaginous tissues (such as chondrogenically differentiated BM-MSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), etc.) or cell lines.

2.3. Selection and data collection

The titles and abstracts of the collated articles were screened using the selection criteria outlined above, and eligibility was confirmed after reviewing the full text. Listed articles were subjected to a final screening to eliminate duplicate publications. Additionally, the references of the selected list were screened to include studies as per the search criteria. Two independent observers (E.V. and K.P) conducted the screening process and analysis, following which two authors re-analyzed the collated data (B.R and S.S).

2.4. Data items: PICO framework

A standardized format was used to tabulate data obtained from the reports analyzed chronologically. In the in-vivo studies, the following outcomes were analyzed: type of animal species, total number, age, sex of the animals, distribution of control and tests, clinical disease model analyzed, type of surgery, route of intervention, the concentration of cells used, study outcomes and limitations.

3. Results

3.1. PRISMA analysis

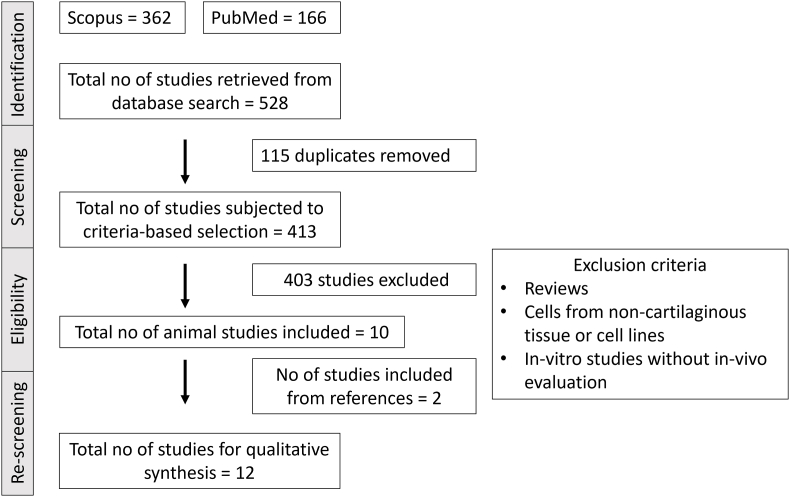

The search database identified 362 articles in Scopus and 166 articles in PubMed. The search was conducted using the following strategy: (chondroprogenitors"[MeSH Terms]) AND (cartilage-progenitors"[MeSH Terms]) AND (chondrogenic progenitors"[MeSH Terms]), from January 2000 to September 2022, including only original articles and studies published in English language only. After eliminating 115 paper duplicates, 413 articles were analyzed against the inclusion criteria. After a thorough screening, 403 articles were excluded, and only ten were eligible for inclusion. Further screening of the references led to the addition of two more studies. Thus a total of twelve studies were selected for further qualitative analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow literature search diagram.

3.2. Source of CPCs, study animal and donor type

Among the twelve studies, the CPCs were sourced from caprine (n = 1), bovine (n = 1), equine (n = 2), rabbit (n = 2), swine (n = 1), human (n = 4) and CBA MRL/Mpj mice (n = 1). Of these, one study used autologous CPCs, three used allogeneic CPCs, one study used autologous and allogeneic CPCs and seven studies were xenogeneic, with only four of them using immunodeficient models. Regarding the isolation method used to obtain the CPCs, most studies used differential adhesion to fibronectin (n = 9) compared to migratory assay (n = 3). In contrast, none of the studies evaluated the potential of sorted progenitors using in-vivo models (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of in-vivo studies using cartilage derived chondroprogenitors derived by fibronectin adhesion assay or migratory assay from articular hyaline cartilage.

| Study reference | Clinical disease model | CPC a) Source b) Method of isolation c) Type of transplant |

In-vivo Study Species |

Study Objectives | Cell/Cell derivatives characterization prior to intervention | Characterization results | a) Total no of animal used b) Sex c) Age d) Test and control distribution |

a) Route b) Concentration c) Intervention |

a) Time period of study after intervention | Evaluation parameters | Outcome | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williams et al., 201015 | Chondral defect: 6 mm lateral femoral condyle preserving the calcified layer |

a) Goat articular cartilage: knee joint b) FAA c) Autologous |

Caprine | Assess the ability of goat CPCs to form cartilage like repair tissue: chondral defect model in comparison to chondrocytes | FAA CPCs:

d) RT-PCR: SOX9, COL2 |

CPCs: CFE: 0.2 PD: 21.4 IHC and RT-PCR: positive labelling and expression Chondrocytes: PD: 3.5 CPCs displayed 6 times higher PD than chondrocytes |

a) 6 b) Female c) Mature d)Test: CPC n = 3 Control: chondrocytes n = 3 |

a) Open procedure b) 2 x 105 of CPC or chondrocytes c) 2 x 105 on 5 mm collagen type I/III membrane: inserted into defects secured with 8 individual sutures |

2 weeks immobilization with sling Euthanasia: following 20 months |

Routine histology: Safranin O IHC: Collagen type II ICRS scoring: 3 blinded observers |

Cartilage formation seen with excellent integration Comparable ICRS scores |

|

| Marcus et al., 201429 | In-vivo plasticity | a) Surface zone and full-depth CPCs from 7-day bovine MCP joints b) FAA c) Xenogeneic |

Bovine CPCS implanted into SCID mice | Determine the in-vivo plasticity of labelled clonal and enriched CPCs versus chondrocytes | NA | NA | a) NA b) NA c) 8 weeks d) Test:

|

a) i.m thigh injections b)25 μl containing 5 × 105 cells/injection c) 2 x 105 cells of either labelled bovine clonal CPCs or enriched CPCs or chondrocytes injected directly into the SCID thigh muscles |

2 weeks | Pellets/pooled muscle fibers: cryo- sectioning

|

|

|

| Frisbie et al., 201523 | Chondral defects: 15 mm medial aspect of the of femur | a) Equine articular cartilage b) FAA c) Autologous and Allogeneic |

Equine | Determine superiority of autologous vs allogeneic CPCs in fibrin for the treatment of chondral defects | - Post thaw viability assay via trypan blue | - Viability was greater than 88% | a) 12 b) NA c) Skeletally mature horses: 2–6 years d) Control: Plain defect n = 4 Defect with fibrin alone n = 12 Defect with autologous cell n = 4 Defect with allogeneic cells n = 4 |

a) Implant: femoro-patellar arthrotomy b) 36 x 106 cells/defect c) cells of either autologous or allogeneic CPCs in 600 μl of fibrinogen +600 μl of thrombin |

- 12 months | - Musculo-skeletal examination (Lameness grade) and radiographs: 2 months interval

|

Autologous CPCs with fibrin superior to allogeneic group and controls in terms of histology, radiography, and arthroscopic examination. |

|

| Vinod et al., 201821 | Osteoarthritis | a) NZW adult rabbits b) FAA C) Allogeneic |

NZW adult rabbits | Assess the efficacy of intra-articular injection of CPCs in the treatment of chemical induced osteoarthritis |

|

- Passage 2 CPCs showed a PD of 13.99 in 9 days, positive differentiation staining, high expression of positive markers with maintained in-situ viability in scaffold | a) 12 b) Male c) Mature rabbits d) Hindlimbs -left: control: plain HA, n = 12 - right: test: HA with CPCs, n = 12 |

a) Intraarticular injections. b) Creation of OA: 4 mg MIA in 250 μl for 4 weeks Controls: 250 μl single HA (Left knee) Test: 250 μl HA with 1 x 106 CPCs (Right knee) c) Following 4 weeks of creation, control joint received plain HA and test HA with CPCs. Euthanasia n = 6 at 12 weeks n = 6 at 24 weeks |

−12 and 24 weeks |

|

Test arms showed lower S100A12 expression at both time points and lower OARSI scores when compared to controls at 12 weeks, though not significant. |

|

| Xue et al., 201930 | Nude mice implants | a) Swine b) FAA c) Xenogenic |

Swine chondro-cytes, CPCs and BM-MSCs implanted into nude mice | Assess superiority of chondrocytes, CPCs and BM-MSCs with PHBV scaffold for cartilage repair | - Cell proliferation CCK-8 assay | - BM-MSCs higher proliferation than CPCs than chondrocytes | a) NA b) NA c) NA d)Test - Chondrocytes + PHBV -CPCs + PHBV - BM-MSCs + PHBV |

a) Subcutaneous implant b) Passage 2 Chondrocytes or CPCs or BM-MSCs 2.5 × 106 in 40 μL in 5 mm × 2 mm PHBV c) Following 1 week of in-vitro culture cells-PHBV were implanted into the nude mice |

- 6 weeks | - Harvested explants: Biomechanical analysis Alcian blue, GAG, Total collagen, Histology: H&E, Safranin O IHC: Collagen type 2 RT-PCR: ACAN, SOX9, COL2, VEGF ELISA: VEGF |

BM-MSc + PHBV implants showed vascularization. Chondrocyte group outperformed CPCs group, which were better than BM-MSC group. | - Biological replicate data NA - Data on characterization prior to intervention NA |

| Carluccio et al., 202031 | SCID mice implant CD-1 nu/nu mice implants |

a) Human b) migratory assay c) Xenogeneic |

Human CPCs implanted in SCID mice and CD-1 nu mice | Assess if platelet lysate could activate CPCs responsive to injury | Human CPCs and chondrocytes (n = 20)

|

CPCs grown with 5% PL showed a higher proliferation, migration ability, nestin expression, clonogenicity, CD166 levels when compared to chondrocytes grown in 5% PL and 10% FBS. The CPC+ 10% FBS group failed to show migration of CPCs from cartilage explants |

In vivo tumorigenesis SCID mice a) n = 12 b) male and female c) 6–8 weeks old d) control: MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cell line |

a) s/c injection b) 1x 106 CPC +5% PL c) s/c injection of passage 2 CPCs |

2–3 months post injection | Tumour development | No illness, tumour development or nodules observed | Not compared with chondrocytes to assess superiority |

|

In vivo ectopic chondrogenic and osteogenesis assay CD-1 nu/nu a) 16 b) Female c) 6–8 weeks old d) NA |

a) s/c - pellet implantation three days following chondrogenic induction - CPC + PL + PGA-HA: cartilage formation - CPC + PL + HA/β-TCP: bone formation b) 2x 106 CPCs −5% PL c) s/c implantation of passage 1 CPCs |

4–8 weeks post injection | In- vivo cartilage and bone formation: Histology: Toluidine Blue, IHC: Type II, X collagen |

Formed hyaline like cartilage tissue without hypertrophic fate | Not compared with chondrocytes to assess superiority | |||||||

| Wang et al., 202028 | Surgically induce osteoarthritis | a) CBA and MRL/MpJ mice b) FAA c) Allogeneic |

C57B/L10 mice | Assess if intraarticular injection of EVs derived from CPCs of super healer (MRL/MpJ) mice repair osteoarthritis. |

CPCs: FACS: CD29, CD34, CD44, CD45, CD90 EVs: Nanoparticle tracking analysis RNA sequencing Western blot Proliferation assay Migration assay |

CPCs showed high expression of positive CD markers EVs:

|

a) 40 b) 8-week-old C57B/L10 mice c) Female d) Test: -CBA-EV (n = 10)

|

Creation of OA: a) open surgery b)-c) surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus: 4 weeks: IA injection of CPC EVs a) IA b) 8 μl CBA-EVs (1010 particles/mL) or 8 μl MRL-EVs (1010 particles/mL) in PBS OA and normal group: 8 μl PBS c) Weekly doses 4th – 7th week |

Creation of OA: 4 weeks (First day of 4th – 7th week after injection) IA injection of CPC EVs 8th week |

Knee joints: Histology: Toluidine blue staining and safranin O/fast green IHC: -Collagen type I, II, Aggrecan |

OARSI scores: significantly lower normal, CBA-EV, MRL-EV groups compared to OA group Both EV groups showed lower Col 1 and higher Col2 and ACAN stain EVs from MRL displayed superior therapeutic effect than CBA for the treatment of OA |

- No data on cell labelling |

| Vinod et al., 202122 | Osteoarthritis and osteochondral defects | a) NZW adult rabbits b) FAA C) Allogeneic |

NZW adult rabbits | Assess the efficacy of intra-articular injection of CPCs resuspended in PRP in the treatment of early grade chemical induced OA and OCD | - Trilineage differentiation studies:

|

CPCs displayed multilineage potential with high expression of positive MSC markers | a) 23 b) Male c) Mature rabbits: 1 year d) Hindlimbs OA study arm

OCD study arm

|

a) Intraarticular injections: OA, Open surgery: OCD: 3.5 mm b) -Creation of OA: Single dose of 2 mg MIA in 250 μl of normal saline. (OA resulted after 35 days) - OA study arm Controls: 250 μl single PRP Test: 250 μl PRP with 5 x 106 CPCs -OCD study arm Controls: 25 μl PRP Test: 25 μl PRP with 1 x 106 CPCs labelled with SPIO c) Following 4 weeks of creation of OA, control joint received plain PRP and test PRP with CPCs. Euthanasia n = 10 at 6 weeks n = 10 at 12 weeks |

−6 and 12 weeks |

3 blinded observers |

Comparable S100A12 expression between all groups, Tests arms showed lower OARSI scores than controls but for OCD, the controls were better than the test groups. |

|

| Wang et al., 201924 | Chondral defects | a) Human lateral femoral condyle b) Migratory assay c) Xenogeneic |

Human BM-MSCS, CPCs and chondrocytes implanted in NZW rabbit chondral defects | To compare the effect of PRP on BM-MSCs, CPCs and chondrocytes and when used a s a bio scaffold for cartilage repair | -Cells: FACS: CD29, CD31, CD45, CD90, CD105, STRO-1 RT-PCR: ABCG2, Notch-1, SOX9, COL2, ACAN, RUNX2 -Platelets: CD41a, CD42b -PRP + cells: Proliferation: CCK-8 and growth kinetics: Tryphan blue Cytochemical staining Toluidine blue |

FACS: CPCs and BM-MSCs showed higher expression of stemness markers when compared to chondrocytes. RT-PCR: CPCs less pluripotent than BM-MSCS, with high expression of chondrogenic genes and RUNX2 CPCs and chondrocytes showed superior chondrogenesis with PRP stimulation than BM-MSCs |

a) 30 b) Male c) 5 months d) - Control: Plain chondral defects, n = 5 Plain PRP n = 5 Sham positive control n = 5 -Test (chondral defect) a. PRP + BM-MSC, n = 5 b. PRP + CPC, n = 5 c. PRP + chondrocytes, n = 5 |

a) open surgery 5 mm × 2 mm critical chondral defect: femur trochlea b-c) 2x106 chondrocytes, BMSCs, and CPCs were mixed with 1 mL of PRPs (2000x109 platelets per liter |

a) 12 weeks | Histology: H&E, Alcian Blue, Safranin O, Toluidine blue IHC: Collagen type II -ICRS scoring 5 observers RT-PCR: regenerated tissue Biomechanical testing: Compression and shear testing |

PRP + CPCs group exhibited superiority when compared to BM-MSC, chondrocyte, plain PRP and negative control groups. They displayed better ICRS scores, biomechanical properties, and expression of chondrogenic genes. |

Immunogenicity was not assessed being a xenogeneic study. Only one time point was evaluated. |

| Mancini et al., 202025 | Osteochondral defect | a) Equine b) FAA c) Xenogeneic |

Shetland ponies | To study cartilage and bone repair using zonal and non-zonal composite 3D hydrogel printed thermoplast osteochondral anchor | CPCs and MSCs: NA Cells with embedded hydrogels: Biochemical analysis - DNA, GAG, hydroxyproline and collagen content -Histology: Safranin O -IHC: ACAN, Collagen type I and II |

MSCs in zonal constructs better than CPCs with better GAG and Collagen content. Zonal layering of MSCs followed by CPCs did not improve ECM production |

a) 8 b) NA c) 4–10 years free of lameness and injuries d) Control: NA Test: 8 Random joints received zonal/non-zonal constructs |

a) Open surgery: arthrotomy b) 7x105 cells of MSCs/CPCs c) 6 mm wide x 7.5 mm deep osteochondral defect (Femoropatellar joint) followed either zonal or nonzonal osteochondral anchor implants. |

|

|

MSCs outperformed CPCs in repair, in both zonal and non-zonal construct. CPCs failed to provide a good repair tissue. | Controls not included: plain osteochondral anchor Immunogenicity and response: NA |

| Janssen et al., 202132 | Nude mice implant | a) Human b) migratory assay c) Lentiviral transfected: Xenogeneic |

Foxn1nu mice (Homozygous) | Knocking out RAB5C in CPCs would enhance the chondrogenic potential | Transfected CPCs: -CPCs and RAB5-CPCs Chondrogenic differentiation Mass spectrometry RT-PCR RNA Seq |

Loss of RAB5C increased the expression of SOX5, 6 and 9 and Collagen type 2 | a) 14 b) Female c) 9-week-old d)

|

a) Subcutaneous implant b) NA (4 beads/mice) c) CPC + alginate RAB5C knock out CPC + alginate placed s/c nude mice |

a) 28 days | a) IHC: ACAN, COL1, COL2, KI-67 | CPCs with deleted RAB5C were still able to proliferate, showing good staining for COL2 and ACAN | Different time period evaluation missing. Quantification scores of the implants NA |

| Wang et al., 202126 | Osteochondral defect | a) Human b) FAA c) Xenogeneic |

NZW rabbits | To examine the potential for inducing osteochondral regeneration with human CPCs and PLGA scaffolds in rabbit knees. | -CFU -multilineage differentiation -FACS: CD90, CD44, CD34, CD45, RUNX2, Collagen type II, CD146 -SEM |

-showed similar profile as MSCs with high expression of the chondrogenic marker CD146. | a) 40 b) Male c) 4–5 months d)

-PLGA scaffold, n = 12, -PLGA + CPCs, n = 12 |

a) Open surgery b) 5 xx 106/scaffold c) Osteochondral defect 3mmx3mm: medial femoral condyle |

a) 4 weeks and 12 weeks, |

|

CSPC + PLGA scaffold produced cartilaginous tissue that was well integrated with the host tissue and subchondral bone at both 4th and 12th week. Highest GAG deposition was seen in the CPCs + PLGA group. CM-Dil staining was also seen in the deeper zone (non-defect sites) displaying its migratory potential in response to injury. |

Immunogenicity and response: NA |

Abbreviations: CPCs: chondroprogenitors, FAA: fibronectin adhesion assay; IHC: immunohistochemistry; Collagen type II; RT-PCR: reverse-transcriptase chain reaction; Sox9; CFE: colony forming efficiency; PD: population doubling; Col: Collagen, ICRS: International cartilage repair society; MCP: metacarpal-phalangeal; SCID: severely combined immunodeficiency; NA: not available; PKH26; ICC: immunocytochemistry; H&E: Hematoxylin and Eosin; NZW: New Zealand White; FACS: Fluorescence assisted cell sorting; CD: Cluster of differentiation; HA: Hyaluronic acid; OA: Osteoarthritis; MIA; ELISA; OARSI; BM-MSC: bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell; PHBV: poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate); CCK: Cell counting kit; GAG; ACAN; VEGF; CD1 nu/nu; ; FBS: fetal bovine erum; TCP; PL: platelet lysate; s/c: sub cutaneous; CBA: cross of a Bagg albino; MRL/MpJ: Murphy Roths large; EVs: extracellular vesicles; TSG101:Tumour susceptibility gene 101; IA: intra-articular; PRP: platelet rich plasma; OCD: osteochondral defects; ECM: extracellular matrix; IHP: intermittent hydrostatic pressure; PCNA: proliferating cell nuclear antigen; RAB5C: endosomal trafficking protein; KI-67:; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; PLGA: poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid).

3.3. Clinical disease model

Osteoarthritis (OA) and chondral/osteochondral defects are the two most common pathologies affecting the articular cartilage. Among the twelve studies assessed, three of them evaluated the potential of CPCs for the treatment of OA, three for chondral defects, two for osteochondral defects and four for in-vivo plasticity (Table 1).

Osteoarthritis is a complex disease that involves cartilage degradation potentiated following trauma or a pro-inflammatory microenvironment and, if left untreated, progresses to affect the underlying subchondral bone.19 Of the various models used to mimic osteoarthritis, standard methods include destabilization of the meniscus and intraarticular injection of chemical agents such as collagenase or monosodium iodoacetate (MIA).20 Vinod et al. used varying concentrations of MIA to create OA; the treatment of high-grade OA21 and another early grade OA22 using FAA CPCs incorporated either in sodium hyaluronate or platelet-rich plasma.

Treatment of focal defects involving the cartilage and the underlying bone depends on the depth of the lesion. Chondral defects require only hyaline-like cartilage regeneration, whereas osteochondral defects require additional fibrocartilage formation below the calcified tidemark. The critical size for the five in-vivo chondral/osteochondral defect studies varied depending on the species used to create chondral defects. Chondral lesions ranged between 5 mm for rabbits, 6 mm for caprine and 15 mm for equine, whereas osteochondral lesions 6 mm × 7.5 mm for equine and 3–3.5 mm for rabbit studies (Table 1). All but one study used FAA-derived CPCs as the cell source.

In order to evaluate biocompatibility, including host recellularization and immunogenicity, subcutaneous implantation in small animal models is currently used in preclinical studies. Four of the twelve studies included implantation of CPCs derived either by using FAA (n = 2) or migratory assay (n = 2) to assess their chondrogenic potential when compared to MSCs and chondrocytes (Table 1).

3.4. Characterization of CPCs before intervention

Since the isolation method of CPCs involves the harvest of cartilage samples and derivation of a subset of the cell population from the general pool of chondrocytes, the need to run phenotypic characterization before use is vital. Of the twelve studies, one study did not conduct any analysis, two studies evaluated only their proliferative potential using either trypan blue exclusion and CCK-8 assay, whereas, for the remaining studies, the standard evaluation parameters included FACS for positive and negative markers, RT-PCR assessing the gene expression of chondrogenic markers and migratory assay (Table 1).

3.5. Intervention and outcomes

3.5.1. Chondral defects

The first in-vivo study to assess the potential of CPCs for hyaline cartilage regeneration was by William et al., in 2010 using a caprine 6 mm-chondral defect model.15 FAA-CPCs displayed a six-fold higher population doubling when compared to chondrocytes. However, assessment of repair tissue after 20 months of implantation showed that both cell-laden-collagen membranes (chondrocytes and CPCs) exhibited good regeneration and integration with the created defect. The subsequent equine study to evaluate and compare autologous and allogeneic CPCs embedded in a fibrin scaffold employing a 15 mm chondral defect model reported autologous CPCs (36 x 106/defect) to display superior repair than allogeneic CPCs and the bio-scaffold itself.23 In this 2015 study, Frisbie et al. evaluated the repair at two-time points (6- and 12 months) using radiological and histological staining. However, data on its phenotypic characterization and comparison to other cell types, such as chondrocytes, were unavailable. The first study to compare CPCs with other commonly employed cells for cartilage repair, namely BM-MSCs and chondrocytes, was done by Wang K et al., in 2019.24 In this xenogeneic study, the CPCs suspended in the PRP group exhibited superiority over BM-MSCs, chondrocytes, plain PRP, and the negative control groups. The in-vivo results were in line with the phenotypic results, where CPCs showed high expression of SOX9, COL2A1 and Aggrecan (ACAN) compared to BM-MSCs. However, a single time point evaluation and no data on their immunogenic profile were the limiting factors.

Of the reported studies evaluating the comparable potential of CPCs Vs chondrocytes for chondral defect repair, the concentration of cells used seemed to play a vital role. The report by Wang K et al. utilizing a concentration of 2 x 106 cells for a 5 mm defect displayed superior ICRS repair scores with CPCs compared to William et al.'s concentration of 0.2 x 106 cells for a 6 mm defect.

3.5.2. Osteochondral defects (OCD)

The treatment of OCDs poses to be more complex than chondral defects, as the depth of the lesion facilitates the migration of underlying MSCs, which further contribute to healing. MSCs have been reported to generate a repair tissue that is more fibrocartilaginous in nature when compared to chondrocytes and CPCs. Another complexity involves the generation of hyaline-like repair tissue at the level of the cartilage, and fibrocartilage containing hypertrophic chondrocytes (Collagen type I) and Collagen type X below the calcified tidemark region. Of the twelve studies, three studies evaluated the potential of CPCs for the treatment of OCD (Table 1). The first study was reported by Vinod et al., in 2018, where allogeneic 1 x 106 CPCs labelled with superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) were reconstituted with PRP and placed into a 3.5 mm defect and compared with PRP alone.22 PRP study arm showed significantly superior healing to the test arm in terms of matrix staining and filling of the defect as per the Modified Wakitani scores. However, the non-inclusion of a control arm for SPIO limited the interpretation as Prussian, blue-stained cells were seen even at the deeper zones and could have also contributed to the varied and probable immunogenic response. According to another study conducted on the Shetland ponies' model by Mancini et al., implanting a 3D multi-composite construct containing equine CPCs and MSCs (7 x 105 cells each) into osteochondral defects, there was limited cartilage-like growth in the defect.25 MSCs outperformed the CPCs in both zonal and non-zonal constructs for OCD repair. A recent xenogeneic study by Wang H et 2021; showed that CPCs in poly D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) scaffold produced cartilaginous tissue that integrated well with the host tissue and subchondral bone at the 4th and 12th week.26 The highest GAG deposition was seen in the CPCs + PLGA group, where the concentration of cells used was 5 x 106 cells per scaffold. CPCs known for their enhanced migratory potential were reported to be present in the deeper zones with the ability to migrate to areas outside the defect.

3.5.3. Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA, commonly known as a degenerative joint disease, involves cartilage breakdown with synovium and subchondral bone inflammation. OA has complex pathogenesis, and it is unclear precisely what pathogenic mechanisms cause cartilage destruction and degradation. Standard models of osteoarthritis in animals involve transection of the cruciate ligament in the knee joint resulting in mechanical instability and cartilage damage.20 Although cell-based therapies can be used to treat mechanical OA, they do not address mechanical instability. So another accepted model entails induction of OA using monosodium iodoacetate, which results in chondrocyte death and progression to OA.27 Of the three reported allogeneic studies, two involved the creation of OA using MIA and one via medial meniscus destabilization (Table 1). Vinod et al. group evaluated the ability of CPCs to attenuate the progression of OA in both early and late-grade OA. When CPCs were combined with HA (Hyaluronic acid) for late-grade OA21 and PRP for early-stage OA,22 the OARSI scores were better with the test arms than with the controls that used the bioscaffolds alone in the contralateral hind limbs. Additionally, the evaluation of the synovial fluid OA biomarker S100A12 corroborated with the histological scores, showing lower levels with the test arms than the controls. A study by Wang et al. demonstrated that intraarticular injections of CPCs-derived extracellular vesicles attenuated the OARSI scores of treated joints, providing a new understanding of their role as exosome injections.28 Unlike chondral/OCDs, which would require an open procedure to create the defect, the treatment of OA included single/interval intra-articular injection of the intervention, thereby further reducing the morbidity related to the procedures.

3.5.4. In-vivo plasticity

Four studies evaluated the chondrogenic activity of CPCs following subcutaneous/intramuscular implants in immunodeficient mice (Table 1). Marcus et al. showed that 5 x 105 FAA-CPs when injected into the thigh muscle of SCID mice, failed to form robust cartilage despite favourable expression of SOX-9 and collagen type II.29 Later, Xue et al. showed that implantation of FAA-CPCs (2.5 x 106) encapsulated in poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxy valerate) scaffold showed better chondrogenesis than BM-MSCs, though outperformed by chondrocytes.30 The first assessment of in-vivo tumorigenesis and ectopic chondrogenesis assay of migratory CPCs was performed by Carluccio et al.31 They reported favourable outcomes with migratory CPCs when grown in 5% platelet lysate displaying hyaline repair without a hypertrophic fate. Another study using migratory CPCs showed that knocking out RAB5C, an endosomal trafficking protein resulted in better staining for Collagen type II and ACAN, thus reporting it as a target for enhancing chondrogenesis for future therapeutic approaches.32

3.6. Delivery vehicle, cell concentration, scoring systems and evaluation time following intervention

Regarding the vehicle used for delivering CPCs, Vinod et al. report using sodium hyaluronate and PRP. Both have been commonly used to treat cartilage-related pathologies due to their chondro-inductive and biocompatible nature. Thus, they show effective repair performance even when used as controls. The other vehicles included fibrin and poly (D, L-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PGLA), which enabled CPCs to exhibit chondrogenesis while ensuring cell containment during the process of homing.23,26 In general, better outcomes were reported with a higher concentration of cells/defect or joint volume ratio. The commonly employed scoring system for OA was the OARSI grading (n = 3), ICRS score for chondral defects (n = 2) and modified Wakitani score (n = 1) for OCD (Table 1).

Deciding the time for harvest and evaluation is essential in assessing cell-based repair. Following placement, homing to the injury site occurs within 24–48 h. Thus, the ability of the delivery vehicle to ensure ease of migration and prevention of cell loss is also vital. Following homing, the paracrine factors produced by the implanted cells are reported to influence the microenvironment, enabling both native and transplanted cells to contribute to regeneration. In a few circumstances, though good healing is noted during the short-term treatment, sustenance of the same or the need for repeated interventions requires the inclusion of a long-term evaluation arm. Of the twelve studies, only four involved comparing short-term to long-term results. The period for evaluation of the intervention varied between a minimum of 2 weeks to a maximum of 12 months (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Cell-based therapy in cartilage repair primarily uses MSCs and chondrocytes to facilitate regeneration and repair.4 Despite their efficiency, suboptimal healing observed with their use led researchers to investigate CPCs as a potential substitute for cartilage repair. The various in-vitro reports show that compared to BM-MSCs and chondrocytes, they exhibit superiority for the generation of hyaline-like cartilage due to the superior ability to accumulate glycosaminoglycans and lower expression of hypertrophy markers such as Collagen type X and RUNX2.33, 34, 35 Recently, much work has been invested in characterizing these cells and assessing their potential using in-vitro and preclinical in-vivo models. Performing in vivo studies is crucial to developing novel therapies as they are more reliable and relevant than in-vitro studies. As per current literature, there were no reviews available compiling the available information on in-vivo studies using CPCs. Since the terminology for this cell type varies widely, this review focused on collating the results of animal studies investigating hyaline cartilage-derived progenitors and their potential for cartilage repair. Based on a summary of data, all analyses were divided into two groups based on the technique of progenitor isolation, namely, using FAA and migratory assay.

Of the twelve studies, nine used CPCs isolated using FAA and the remaining used the migratory assay (Table 1). The studies using FAA-CPCs evaluated their ability to attenuate OA, heal defects and form stable cartilage when implanted subcutaneously. FAA-CPCs demonstrated results superior to BM-MSCs24 but similar or inferior to articular chondrocytes.15,30 FAA-CPCs embedded in scaffolds such as PRP did not exhibit improved healing over plain bio-scaffold22; however, autologous FAA-CPs showed better outcome than allogenic FAA CPs.23 A recent in-vitro report comparing FAA-CPCs to migratory CPCs shows that the latter retains and displays superior cartilage repair under normoxia culture conditions; however, there was no literature available on in-vivo studies comparing these two subsets.36 Thus, no clear inference can be drawn on the potential of FAA CPCs due to varied results and a smaller number of studies.

However, it was notable that available studies using migratory CPCs displayed positive outcomes in terms of higher staining for Collagen type II and ACAN, superior healing to BM-MSCs and no tumour formation following in-vivo implantation.32 The current evidence suggests improved outcomes when migratory chondroprogenitors are used, but a direct comparison between FAA CPCs and migratory CPCs under similar microenvironments is warranted.

Small animals such as mice have been commonly used to study cell biology among mammals. Despite their relative affordability, rapid reproduction, and ability to be genetically manipulated, their inability to reproduce particular human disease phenotypes has compelled researchers to investigate larger animal species. It is also relevant to note that significant cell numbers can be efficiently obtained from a single large animal and manipulated in sufficient quantity for further analysis and re-applications. Of the twelve studies, five involved using varied species of immunodeficient mice, with one of the studies reporting positive outcomes with intra-articular injections of CPC derived extracellular vesicles. To develop effective CPC-based therapeutic approaches, disease models that mimic human phenotypes must be improved, including using animals with dimensions and weight-bearing physiology similar to human beings. The invention of osteochondral units (OCU) to study cartilage repair serve to be advantageous as it could provide a platform that could employ human cartilage itself and thus be more representative than in-vitro study models.37 Future research comparing the various cell types for cartilage repair using the OCU model could provide valuable information for clinical translation.

It was also noted that no literature was available that evaluated the immunogenic and immunomodulatory properties of CPCs before their transplantation. One study used human CPCs to treat osteochondral defects in rabbits without information on their immunogenicity profile. However, this is essential for predicting the in-vivo behaviour of CPCs following transplantation. Another limitation noted was the limited data on the labelling of implanted cells, which is also necessary to assess the inherent potential of transplanted cells and the contribution of native resident cells.

In conclusion, this review reiterates that articular cartilage-derived CPCs can be a valuable tool in cell-based therapy for cartilage repair. The limited number of animal studies and comparisons with commonly used cells warrants further studies and experiments involving CPCs, to bridge the gap in knowledge before effective utilization in the clinical setting. The collative data indicates that CPCs, with their higher chondrogenic ability and lower terminal differentiation tendency, could serve as the alternative cell source for treating cartilage pathologies such as osteoarthritis and chondral defects in generating hyaline-like repair rather than fibrocartilage, thus conforming biomechanical outcomes.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest(s).

Funding

No funding was received for the publication of this article.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Internal ethics committee approval

Not applicable.

Author contribution

Two independent observers (E.V. and K.P) conducted the screening process, data curation and analysis, following which two authors re-analyzed the collated data (B.R and S.S). All authors were involved in the conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, writing and approval of the draft and final manuscript.

Credit author statement

Elizabeth Vinod: data curation and analysis. Validation of data. Writing. Final approval of the manuscript, Kawin Padmaja: data curation and analysis. Validation of data. Writing. Final approval of the manuscript, Boopalan Ramasamy: data curation and analysis. Validation of data. Writing. Final approval of the manuscript, Solomon Sathishkumar: data curation and analysis. Validation of data. Writing. Final approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2022.10.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Fosang A.J., Beier F. Emerging Frontiers in cartilage and chondrocyte biology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(6):751–766. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armiento A.R., Alini M., Stoddart M.J. Articular fibrocartilage - why does hyaline cartilage fail to repair? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;146:289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakrzewski W., Dobrzyński M., Szymonowicz M., Rybak Z. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:68. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittberg M. Clinical articular cartilage repair—an up to date review. Annals of Joint. 2018;3(0) doi: 10.21037/aoj.2018.11.09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittberg M., Lindahl A., Nilsson A., Ohlsson C., Isaksson O., Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marlovits S., Hombauer M., Truppe M., Vècsei V., Schlegel W. Changes in the ratio of type-I and type-II collagen expression during monolayer culture of human chondrocytes. J Bone Jt Surg Br Vol. 2004;86(2):286–295. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b2.14918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris J.D., Siston R.A., Brophy R.H., Lattermann C., Carey J.L., Flanigan D.C. Failures, re-operations, and complications after autologous chondrocyte implantation – a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(7):779–791. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X., Kumagai G., Wada K., et al. High osteogenic potential of adipose- and muscle-derived mesenchymal stem cells in spinal-ossification model mice. Spine. 2017;42(23):E1342–E1349. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez-Moure J.S., Corradetti B., Chan P., et al. Enhanced osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from cortical bone: a comparative analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:203. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinod E, Parameswaran R, Ramasamy B, Kachroo U. Pondering the potential of hyaline cartilage–derived chondroprogenitors for tissue regeneration: a systematic review. Cartilage. Published online August 25, 2020:1947603520951631. doi:10.1177/1947603520951631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Dominici M., Le Blanc K., Mueller I., et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowthwaite G.P., Bishop J.C., Redman S.N., et al. The surface of articular cartilage contains a progenitor cell population. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 6):889–897. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes A.J., Tudor D., Nowell M.A., Caterson B., Hughes C.E. Chondroitin sulfate sulfation motifs as putative biomarkers for isolation of articular cartilage progenitor cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56(2):125–138. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7320.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan I.M., Bishop J.C., Gilbert S., Archer C.W. Clonal chondroprogenitors maintain telomerase activity and Sox9 expression during extended monolayer culture and retain chondrogenic potential. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(4):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams R., Khan I.M., Richardson K., et al. Identification and clonal characterisation of a progenitor cell sub-population in normal human articular cartilage. PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koelling S., Kruegel J., Irmer M., et al. Migratory chondrogenic progenitor cells from repair tissue during the later stages of human osteoarthritis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(4):324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seol D., McCabe D.J., Choe H., et al. Chondrogenic progenitor cells respond to cartilage injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(11):3626–3637. doi: 10.1002/art.34613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su X., Zuo W., Wu Z., et al. CD146 as a new marker for an increased chondroprogenitor cell sub-population in the later stages of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(1):84–91. doi: 10.1002/jor.22731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grässel S., Aszodi A. Osteoarthritis and cartilage regeneration: focus on pathophysiology and molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6156. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendele A.M. Animal models of osteoarthritis. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2001;1(4):363–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinod E., James J.V., Sabareeswaran A., et al. Intraarticular injection of allogenic chondroprogenitors for treatment of osteoarthritis in rabbit knee model. J Clin Orthop. Trauma. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.07.003. 0(0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinod E., Amirtham S.M., Kachroo U., et al. Articular chondroprogenitors in platelet rich plasma for treatment of osteoarthritis and osteochondral defects in a rabbit knee model. Knee. 2021;30:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2021.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisbie D.D., McCarthy H.E., Archer C.W., Barrett M.F., McIlwraith C.W. Evaluation of articular cartilage progenitor cells for the repair of articular defects in an equine model. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2015;97(6):484–493. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Li J, Li Z, et al. Chondrogenic progenitor cells exhibit superiority over mesenchymal stem cells and chondrocytes in platelet-rich plasma scaffold-based cartilage regeneration. Am J Sports Med. Published online June 13, 2019:036354651985421. doi:10.1177/0363546519854219. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Mancini I.A.D., Schmidt S., Brommer H., et al. A composite hydrogel-3D printed thermoplast osteochondral anchor as an example for a zonal approach to cartilage repair: in vivo performance in a long-term equine model. Biofabrication. 2020;20 doi: 10.1088/1758-5090/ab94ce. Published online May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H.C., Lin T.H., Hsu C.C., Yeh M.L. Restoring osteochondral defects through the differentiation potential of cartilage stem/progenitor cells cultivated on porous scaffolds. Cells. 2021;10(12):3536. doi: 10.3390/cells10123536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinod E., Boopalan P.R.J.V.C., Arumugam S., Sathishkumar S. Creation of monosodium iodoacetate-induced model of osteoarthritis in rabbit knee joint. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147(3):312–314. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2004_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang R., Jiang W., Zhang L., et al. Intra-articular delivery of extracellular vesicles secreted by chondrogenic progenitor cells from MRL/MpJ superhealer mice enhances articular cartilage repair in a mouse injury model. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s13287-020-01594-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus P., De Bari C., Dell'Accio F., Archer C.W. Articular chondroprogenitor cells maintain chondrogenic potential but fail to form a functional matrix when implanted into muscles of SCID mice. Cartilage. 2014;5(4):231–240. doi: 10.1177/1947603514541274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue K., Zhang X., Gao Z., Xia W., Qi L., Liu K. Cartilage progenitor cells combined with PHBV in cartilage tissue engineering. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-1855-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carluccio S., Martinelli D., Palamà M.E.F., et al. Progenitor cells activated by platelet lysate in human articular cartilage as a tool for future cartilage engineering and reparative strategies. Cells. 2020;9(4) doi: 10.3390/cells9041052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janssen J.N., Izzi V., Henze E., et al. Enhancing the chondrogenic potential of chondrogenic progenitor cells by deleting RAB5C. iScience. 2021;24(5) doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy H.E., Bara J.J., Brakspear K., Singhrao S.K., Archer C.W. The comparison of equine articular cartilage progenitor cells and bone marrow-derived stromal cells as potential cell sources for cartilage repair in the horse. Vet J. 2012;192(3):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vinod E., Kachroo U., Rebekah G., Yadav B.K., Ramasamy B. Characterization of human articular chondrocytes and chondroprogenitors derived from non-diseased and osteoarthritic knee joints to assess superiority for cell-based therapy. Acta Histochem. 2020;122(6) doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2020.151588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vinod E., Parameswaran R., Amirtham S.M., Rebekah G., Kachroo U. Comparative analysis of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, articular cartilage derived chondroprogenitors and chondrocytes to determine cell superiority for cartilage regeneration. Acta Histochem. 2021;123(4) doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2021.151713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinod E., Johnson N.N., Kumar S., et al. Migratory chondroprogenitors retain superior intrinsic chondrogenic potential for regenerative cartilage repair as compared to human fibronectin derived chondroprogenitors. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Vries-van Melle M.L., Mandl E.W., Kops N., Koevoet W.J.L.M., Verhaar J.A.N., van Osch G.J.V.M. An osteochondral culture model to study mechanisms involved in articular cartilage repair. Tissue Eng C Methods. 2012;18(1):45–53. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2011.0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.