Abstract

The peptidomimetic approach has emerged as a powerful tool for overcoming the inherent limitations of natural antimicrobial peptides, where the therapeutic potential can be improved by increasing the selectivity and bioavailability. Restraining the conformational flexibility of a molecule may reduce the entropy loss upon its binding to the membrane. Experimental findings demonstrate that the cyclization of linear antimicrobial peptoids increases their bactericidal activity against Staphylococcus aureus while maintaining high hemolytic concentrations. Surface X-ray scattering shows that macrocyclic peptoids intercalate into Langmuir monolayers of anionic lipids with greater efficacy than for their linear analogues. It is suggested that cyclization may increase peptoid activity by allowing the macrocycle to better penetrate the bacterial cell membrane.

1. INTRODUCTION

The development of new antimicrobial therapeutics is of paramount clinical importance.1 Host defense peptides (HDPs) of the innate immune system have been shown to exhibit broad spectrum antimicrobial activity.2,3 However, HDPs are highly susceptible to proteolytic degradation and are potentially toxic against mammalian cells.4,5 Emerging research avenues are focusing on de novo designed molecules that can mimic the structure and function of HDPs and may serve as a viable alternative to conventional antibiotics.6,7 Among multiple synthesis approaches,8,9 peptoids (oligo-N-substituted glycines) are among the most prominent compounds with improved antimicrobial activity and minimal cytotoxicity,10−12 which have been shown to maintain their effectiveness in vivo.13,14 To rationally design and then optimize these new candidates for future pharmaceutical applications, a better understanding of their structure−function relationships is required.15

The antibacterial activity of peptides displayed in vivo and in vitro is often governed by their interaction with bacterial membranes.16,17 The cellular membrane of a pathogen acts as a primary barrier to antimicrobial molecules, which must be either disrupted or traversed.18,19 Unlike mammalian cells, bacterial membranes contain a large quantity of negatively charged components such as lipopolysaccharides (Gram-negative) and teichoic acids (Gram-positive). The cationic charge of antimicrobial agents facilitates their selective initial binding to the bacterial cell surface, whereas the amphipathicity enables their incorporation into the membrane.20−22 The insertion of antimicrobials requires overcoming entropic and enthalpic energy barriers associated with the loss of molecular conformational freedom and the creation of space within the lipid bilayer required to accommodate the molecules.23 The membrane activity of molecules can therefore be modulated via tweaking their conformational rigidity, thereby altering the depth of the entropic barrier well.24,25 A straightforward and simple way to restrict the flexibility of a linear molecule is to constrain the termini via the formation of a cyclic backbone.26 Importantly, the cyclization strategy allows modifying the flexibility of a molecule in an orthogonal manner such that the charge, amphipathicity, and molecular volume remain unchanged.

Recently, cyclic antimicrobial compounds mimicking natural HDPs such as γ-AApeptides,27 D,L-α-peptides,28 and peptoids29,30 have been designed and synthesized. Cyclization has been shown to enhance the activity of Arg- and Trp-rich hexapeptides by improving their ability to permeate the outer and inner membranes of E. coli.31 Oren et al. reported that the cyclization of amphipathic α-helical peptides increases their capability to insert into negatively charged phospholipid bilayers.32 Molecular dynamics simulations have also suggested that cyclic peptides may embed more deeply into the membrane bilayer and form toroidal pores whereas their linear counterparts remain at the surface, demonstrating reduced antimicrobial activity.33,34

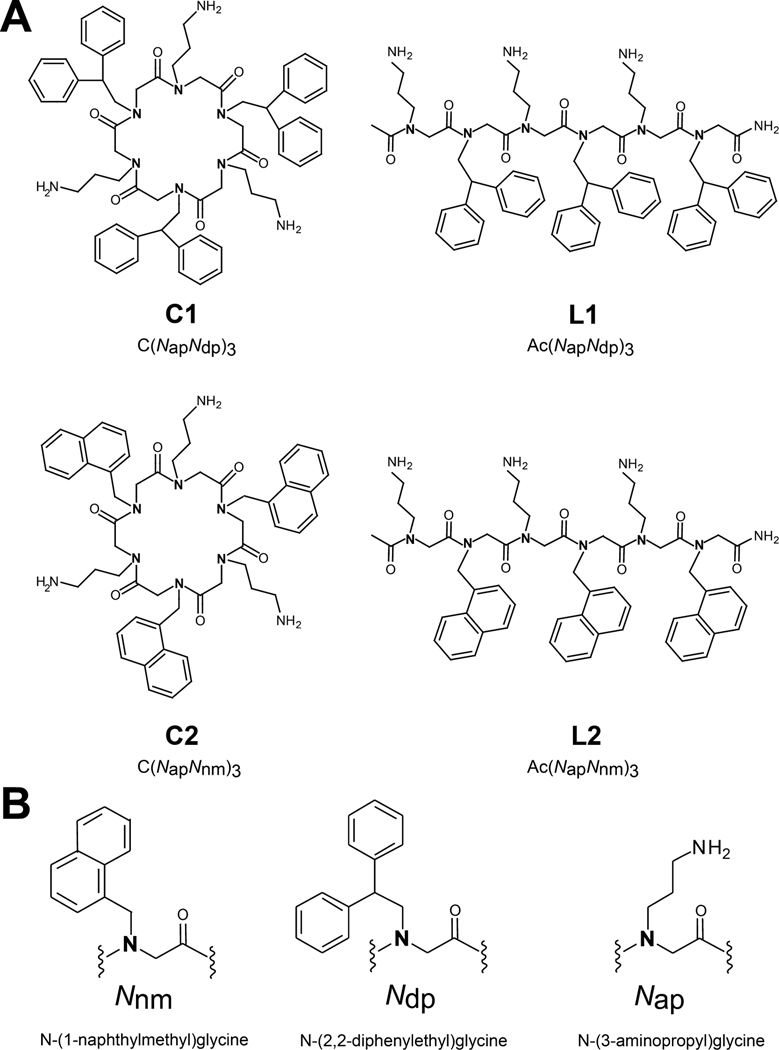

Similarly, peptoids have been shown to benefit from cyclization, displaying superior in vitro bacterial growth inhibition with respect to their linear analogues.35 However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of this phenomenon remain poorly understood. Here, to enable the rational use of cyclization in the design of peptoid-based antimicrobials, we explore how this parameter impacts the membrane activity of peptoids by comparing two pairs of linear and cyclic peptoid molecules (Figure 1), hereafter referred to as L1/C1 and L2/C2. Membrane interactions are investigated using scanning electron microscopy on bacterial cells and high-resolution X-ray scattering alongside epifluorescence microscopy on Langmuir monolayers.

Figure 1.

(A) Molecular structures of cyclic (left) and linear (right) peptoids used in this study. (B) Peptoid monomer subunits.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Peptoid Synthesis and Purification.

Peptoid sequences were chosen to have an uncharged C-terminal amide both to give the best comparison to the peptoid macrocycles, which do not bear a charged carboxylate, and to form the most likely molecules to display potent antimicrobial activity. This was done such that sequence-specific peptoids were synthesized via the submonomer chemistry method, applying iterative sequential steps of bromoacylation and nucleophilic displacement to construct each monomer unit.35 Briefly, the amine on the initial submonomer is bromoacetylated, and the resin-bound acyl bromide is displaced by a primary amine that affords the formation of the side chain of interest. In the case of linear peptoid synthesis, the final step is the acetylation of oligomer with acetic anhydride followed by cleavage from the resin with trifluoroacetic acid, forming a C-terminal amide. For cyclization, linear precursors are synthesized on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin to generate free N-terminal amino and C-terminal carboxylic acid groups, cleaved with 20% hexafluoroisopropanol and dichloromethane30 and cyclized using (benzotriazol-1-yl-oxytripyrrolidinophosphonium hexafluorophosphate) (PyBOP).29

All compounds were purified to >95% homogeneity by reversephase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), characterized by mass spectrometry to confirm the molecular weight of the purified product, and stored as dry lyophilized powders at −20 °C.

2.2. Antibacterial Activity in Vitro.

Peptoid-susceptibility assays for all bacterial strains were conducted in 96-well plates using the broth-macrodilution procedure outlined in document M07-A7 of the CLSI.36 Screening against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 (strain LAC) was performed in LB (Luria-Bertani) medium. After incubation at 37 °C for 18 to 24 h, the turbidity of each sample was analyzed by visual inspection, and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of peptoid resulting in an optically clear bacterial culture. Experiments were conducted in three independent replicates of three parallel trials to ensure statistical significance.

2.3. Constant-Pressure Insertion Assays.

Using the Langmuir technique to evaluate the insertion of membrane-active molecules into lipid monolayers may be done in two ways: by keeping either area or surface pressure invariant. Although the constant-area approach has been widely used for Langmuir insertion assays, the latter one appears to be more relevant as confirmed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) on unilamellar liposomes of the same lipid composition. After peptoids were added to solution, the average surface area of the liposome sphere expanded in the same way as for a planar monolayer (Figure S1). Because X-ray reflectivity gives the overall average density, experiments conducted at constant pressure may be used to monitor the total amount of excess material intercalated into the monolayer once equilibrated, and these densities may be normalized to the change in area available per lipid molecule. The instrumental setup consisted of a custom-made Teflon Langmuir trough equipped with two Teflon barriers whose motions were precisely controlled by motors for symmetric compression or expansion of monolayers at the air−liquid interface. The monolayer surface pressure was measured by a stationary Wilhelmy plate and kept at a constant pressure of 30 mN m−1 by a pressure−area feedback loop throughout the duration of the experiment. Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) without calcium and magnesium ions was used as the subphase, with the temperature being maintained to within 0.5 °C from a preassigned temperature of 23 °C. To reduce fluctuations and maintain stability, all of the equipment was mounted on a vibrationisolation stage.

DPPG and kdo2-lipid A were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and used without further purification. Lipids were dissolved in chloroform and chloroform/methanol/water 75:15:10 v/ v/v% solutions correspondingly, prior to depositing onto the aqueous surface. Deposited lipids self-assemble such that their hydrophobic acyl chains, or tails, align perpendicular to the interface into the air and their hydrophilic polar regions, or heads, are oriented toward the liquid subphase.

The peptoid solutions were introduced into the subphase underneath the monolayer at 20% of their MICs against S. aureus. The incorporation of membrane-active compounds into the lipid monolayer generally caused an increase in surface pressure. To counterbalance the rising surface pressure, the barriers expanded and the effective relative change in area per lipid molecule (ΔA/A) was monitored. The maximum value of ΔA/A was taken to characterize the membrane insertion capability of the studied compounds.

2.4. Epifluorescence Microscopy.

Fluorescence image contrast arises from different phase densities and partitioning characteristics of the dye molecules in coexisting phases. Therefore, it is possible to gain insight into the structure of the lipid layer by imaging its lateral fluorescence distribution. Experiments were performed as previously described.37 The Langmuir trough used for insertion experiments was equipped with an epifluorescence microscope mounted to observe the phase morphology of the lipid monolayers. Lipid-linked Texas red dye (DHPE Texas red; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; 1 mol %) was incorporated into the stock phospholipid solutions prior to spreading. Data for excitation of between 530 and 590 nm and emission of between 610 and 690 nm were gathered through the use of an HYQ Texas red filter cube. Because of steric hindrance, the dye is localized in the disordered areas, rendering it bright, whereas the ordered loci remain dark.38 Images from fluorescence microscope were collected sequentially at intervals of 30 s during the initial 20 min after peptoid administration using a silicon-intensified target camera and recorded on HD by MetaMorph Microscopy Automation & Image Analysis software 7.0 (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA). This technique permits the monolayer morphology to be observed over a large lateral area (0.16 mm2) at certain time points while isotherm data are obtained concurrently and provide information about its evolution over time. A resistively heated indium tin oxide-coated glass plate (Delta Technologies, Ltd., Loveland, CO) was placed over the trough to minimize dust contamination, air convection, and evaporative losses as well as to prevent the condensation of water on the microscope objective. The condensed domains on the surface of the kdo2-lipid A monolayer were not observable at the resolution of the microscope (∼1 μm).

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy in Vitro.

SEM experiments were performed following a previously published procedure.39 Samples of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 (Los Angeles Country clone, LAC) were prepared by inoculating an overnight cell culture in fresh LB medium until >OD600 ≈ 0.4 (approximately 3 h at 37 °C). Then, bacteria were treated with the antimicrobial compound at the minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) as well as 2-fold higher (supra-MIC) and lower (sub-MIC) concentrations (previously determined for cell density at OD600-0.4) for 1 or 24 h at 37 °C. Untreated controls were kept in standard LB medium. After centrifugation (6000g, 20 min at RT), washing, and resuspension in PBS, cells were deposited onto a 1 cm2 piece of a 0.45μm-pore-size membrane filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA) fixed with 8% (v/v) glutaraldehyde/PBS (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) and postfixed with 0.5% (w/v) OsO4 in PBS (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) at 4 °C overnight. The samples were sequentially dehydrated with a graded ethanol series, including en bloc staining with 3% uranyl acetate in 30% ethanol. Finally, membrane pieces were air-dried at room temperature and attached to an aluminum pin stub with a carbon conductive adhesive (PELCO , Tedd Pella Inc., Redding, CA). A 5 nm layer of gold was sputtered on the samples to avoid charging in the microscope. Microscopy was performed using a Zeiss MERLIN field emission scanning electron microscope (Oberkochen, Germany). Secondary electron images were taken at low electron energies between 2 and 4.0 keV.

2.6. X-ray Reflectivity.

Specular X-ray reflectivity (XR) measurements were performed using a liquid surface diffractometer at the 9-ID and 15-ID beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL). The temperature-controlled Langmuir trough for the insertion experiments was mounted in a hermetic helium-filled canister where the oxygen level was constantly monitored to be at <1% in order to minimize the scattering background. The synchrotron X-ray beam was monochromated to a wavelength of λ = 0.9202 Å (1.24 Å at 15-ID) and struck the horizontal liquid surface of the sample at low angle, close to the critical one for this wavelength. The reflected beam intensity was measured with a moveable detector as a function of incident angle. All Measurements have been made in triplicate to ensurestatistical significance.

The ratio between the intensity of X-rays specularly reflected from a surface and the intensity of the incoming beam, called reflectivity,40 was measured as a function of wave-vector transfer qz over a range of angles (corresponding to qz values from 0.01 to 0.7 Å−1). Measured data divided by the Fresnel reflectivity RF and plotted against qz were analyzed by both model-dependent (MD) (employing RFIT2000 by Oleg Konovalov, ESRF) and model-independent (MI)41 fitting, yielding very similar models.

2.7. XR Model Analysis.

The interface has been modeled as a stack of slabs with variable electron densities (ρ) and thicknesses (l). The final fit was achieved by minimizing the χ2 value while ensuring that the parameters obtained were physically relevant. XR results agree well with our earlier studies of DPPG and kdo2-lipid A.42 The extra electrons per lipid molecule contributed by the peptoid to each slab were calculated using the following formula:

Here l slab and ρ slab are the thickness and electron density of the slab, respectively, A lipid + ΔA lipid is the area per lipid molecule upon insertion, and N initial e−slab is the number of electrons in the slab in the original untreated monolayer. The statistical error was counted as the square root of the total number of electrons divided by the square root of the number of experimental attempts. Another numerical characteristic of insertion is the lipid-to-drug ratio in the film, estimated as

where Ndruge− is the number of electrons per drug molecule. (For polar slabs, a 50% hydration of polar moieties is assumed.) The lower lipid-to-drug ratio denotes higher concentration of inserted compound molecules in the monolayer, signifying a higher surface activity.

3. RESULTS

The antibacterial properties of peptoids are investigated using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays against representative bacterial species, and their hemolytic concentrations are measured to assess the toxicity against mammalian cells (Table 1). The MIC corresponds to the lowest concentration of a drug that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation. Among the tested bacteria, MIC values for cyclic peptoids are 2−4 times lower as compared to their linear analogues. Although low MIC indicates the efficacy of a compound against specific pathogens, evaluating the selectivity between targeted bacteria and mammalian cells is a more relevant metric of the therapeutic potential. Hemolytic concentrations (HC50, causing 50% hemolysis) of all studied peptoids are higher than 250 μg mL−1. Defining a selectivity ratio (SR) as the HC50 divided by the MIC against S. aureus, cyclic peptoids display a 4-fold increase in cell specificity, which indicates their suitability for further evaluation as therapeutics.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial and Hemolytic Activities of Peptoids

| MIC [μg mL−1]a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peptoid/sequence | chemical formula | S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | A. baumannii | HC50 [μg mL−1]b | SRc |

| L1/Ac(NapNdp)3 | C65H86N10O7 | 15.6 | 15.6 | 15.6 | >250 | >16 |

| C1/C(NapNdp)3 | C63H81N9O6 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 7.8 | >250 | >64 |

| L2/Ac(NapNnm)3 | C56H68N10O7 | 125 | 125 | 125 | >250 | >2 |

| C2/C(NapNnm)3 | C54H63N9O6 | 31.3 | 31.3 | 31.3 | >250 | >8 |

Minimum inhibitory concentrations against Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Hemolytic concentrations at which 50% hemolysis is observed.

Selectivity ratio: HC50/MIC against S. aureus.

The damaging effects of peptoids on S. aureus cells are imaged via scanning electron microscopy (SEM).43 SEM micrographs of bacteria after treatment with L1 or C1 at their MICs show large pores and deep craters in their cellular envelope (Figure 2B,C). In the control samples of untreated S. aureus, the surfaces of cells are smooth and undamaged (Figure 2A). This observation suggests that peptoid treatment leads to cell death by compromising membrane integrity. This suggests that the bacteriostatic properties measured by MIC assays are bactericidal. However, no specific differences between L1 and C1 modes of action are deciphered by SEM, which itself cannot elucidate the improved bactericidal properties of the cyclic peptoid in vitro.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of untreated CA-MRSA cells on membrane filters at 60 k× magnification (A) and cells after 1 h of treatment with C-1 (B) and L-1 (C) at their MICs. The samples incubated with peptoids overnight (18 h) are represented in the upper boxes of the corresponding micrographs.

The basic physicochemical properties of bacterial membranes, determined primarily by their lipid constituents, are likely to be the critical determinants of antimicrobial efficacy.37,44 To better understand the mechanism of interactions between the antimicrobial peptoids and bacterial cell membranes, we study model Langmuir monolayers45,46 that consist of either 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DPPG) or a truncated lipopolysaccharide, di[3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonyl]-lipid A, (kdo2-lipid A).42 The rationale behind this choice is as follows: kdo2-lipid A constitutes the core region of the outer membrane in most Gram-negative bacteria, while phosphatidylglycerol is the most abundant anionic phospholipid of bacterial cytoplasmic membranes. The peptoids are injected into the aqueous subphase to enable interaction with the artificial membrane at the air−water interface, thus simulating interactions with the bacterial surface in the aqueous cell environment.47,48 The surface pressure of 30 mN m−1, which approximates the average packing density of lipids in bilayers,49 is held constant via proportional-integral-derivative feedback control, while the interactions between lipid monolayers and antimicrobials are observed as a change in area over time. Area changes are recorded continually until equilibrium is reached (approximately 15 min, Figure 3) and the relative increase in the area per lipid molecule is calculated. Morphological changes in the lateral surface are simultaneously captured by epifluorescence microscopy (EFM).

Figure 3.

Changes in area per lipid molecule after the incorporation of peptoids into DPPG as a function of time (top left) and DPPG and kdo2-lipid A monolayers after equilibration (top right). Epifluorescence images of a DPPG monolayer after C1 and L1 injection at concentrations corresponding to 20% of their MIC against S. aureus (bottom). A lipid-linked Texas red-DHPE fluorescence probe (1 mol %) is added to the phospholipid solutions. Because of steric hindrance, the dye is located in the liquid-disordered phase, rendering it bright, whereas the liquid-ordered phase remains dark.

The immediate increase in area upon introduction of peptoids shows that they readily incorporate into DPPG monolayers (Figure 3, top left). The insertion isotherm of C1 comes to a plateau in 5 min after peptoid injection, whereas for L1 it takes a slightly longer time (about 8 min) to reach equilibrium. The overall increase in area per lipid molecule does not show significant excellence in cyclic compounds over their linear analogues. However, for kdo2-lipid A this difference is more pronounced and is about 15−20% (Figure 3, top right). Interestingly, the timing of morphological changes of the DPPG imaged by EFM agrees well with the insertion kinetics. Domains of the liquid-ordered phase are completely obliterated by C1 and L1 after reaching the maximum area increase (Figure 3, bottom). Nearly identical behavior is observed for L2 and C2. Cyclic peptoids destroy the lateral order of the DPPG monolayer faster than their linear counterparts. However, the mechanisms of their action are indistinguishable at the micrometer scale, although both potentially fluidize the membrane. This assertion agrees with previous Langmuir studies on the arenicin-derived peptides.50

High-resolution surface X-ray scattering offers further insight into the impact of antimicrobials on the molecular integrity of lipid membranes.44,51,52 X-ray reflectivity (XR) specifically yields the electron density profile along the surface normal (Z) of a film.53,54 Figure 4 shows the derived density profiles of DPPG and kdo2-lipid A monolayers before and after their interactions with C1 and L1 normalized to the area available per lipid molecule. The data for C2/L2 show a similar trend and are presented in Figure S2 (Supporting Information). All X-ray reflectivity experiments were conducted after the films had reached an equilibrium state where no further changes in film area were detected.

Figure 4.

Electron density profiles of DPPG (A) and kdo2-lipid A (B) before and after linear (L1) and cyclic (C1) peptoids (left). Corresponding Fresnel-divided reflectivity curves at 30 mN m−1 (right). For XR curves, the scatter plots are experimental values, and solid lines are the best fits of the models to the experimental data. Molecular cartoons show the general correlation between lipid structure and electron density maps.

To facilitate the interpretation of electron density profiles, a lipid monolayer can be approximated with a number of slabs with a fixed electron density and thickness. Each slab corresponds to a distinct region within the lipid molecule, e.g., hydrocarbon chains or headgroups. Changes in the number of electrons in each slab and in the monolayer as a whole, upon introduction of an antimicrobial, are directly related to the equilibrium lipid-to-drug ratio and localization of the drug within the membrane. Complete details for parameters derived from XR are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

X-ray Reflectivity Modeling Resultsa

| experiment | Ndrug e− | lT (Å) | ρT (e−/Å3) | extra e− | lH (Å) | ρH (e−/Å3) | extra e−H | lOL (Å) | ρOL (e−/Å3) | extra e−OL |

A

lipid + ΔA lipid (Å2)b |

lipid- to-drug ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPG | N/A | 16.5 | 0.312 | 8.3 | 0.477 | N/A | 47 | |||||

| DPPG/L1 | 622 | 12.9 | 0.292 | 72 ± 5 | 6.2 | 0.454 | 86 ± 5 | 8.9 | 0.375 | 32 ± 3 | 87 | 3.3 |

| DPPG/C1 | 585 | 12.1 | 0.381 | 167 ± 8 | 6.0 | 0.438 | 82 ± 5 | N/A | 92 | 2.4 | ||

| DPPG/L2 | 550 | 11.2 | 0.270 | ∼0 | 9.2 | 0.471 | 208 ± 8 | N/A | 85 | 2.6 | ||

| DPPG/C2 | 513 | 11.8 | 0.324 | 72 ± 5 | 7.3 | 0.475 | 140 ± 7 | N/A | 86 | 2.4 | ||

| Kdo2-lipid A | N/A | 13.1 | 0.332 | 3.4 | 0.539 | 7.6 | 0.469 | 125 | ||||

| Kdo2-lipid A/L1 | 622 | 9.8 | 0.299 | ∼0 | 7.4 | 0.483 | 396 ± 12 | 6.1 | 0.406 | 77 ± 5 | 175 | 1.4 |

| Kdo2-lipid A/C1 | 585 | 9.0 | 0.362 | 76 ± 5 | 7.4 | 0.445 | 397 ± 12 | 6.3 | 0.376 | 50 ± 4 | 190 | 1.4 |

| Kdo2-lipid A/L2 | 550 | 10.2 | 0.241 | ∼0 | 5.3 | 0.537 | 372 ± 11 | 8.5 | 0.407 | 131 ± 7 | 211 | 1.1 |

| Kdo2-lipid A/C2 | 513 | 9.8 | 0.267 | 74 ± 5 | 5.7 | 0.518 | 467 ± 13 | 8.1 | 0.412 | 149 ± 7 | 236 | 0.7 |

Subscripts: T – tails, H – heads, OL – outer layer.

Area per lipid molecule (A) = Nlipid molecules/Atotal.

After the injection of C1 and C2 into DPPG, the modeled electron density of the hydrocarbon chains is considerably higher as compared to that of pure lipid (0.381/0.324 e−/Å3), whereas the insertion of L1 and L2 reduces the electron density in this region (0.292 and 0.270 e−/Å3). This observation suggests that linear peptoids are less apt to permeate far into the hydrophobic core of the DPPG monolayer. The thinning of the upper slab (from 16.5 to 11−13 Å) upon their insertion is likely caused by the molecular tilt of lipid tails with the headgroups shifted closer to the interface. The lipid-to-drug ratio with DPPG is also lower for cyclic peptoid (2.4 against 3.3), although for the C2/L2 pair this difference is less pronounced (2.4/2.6).

Extra electrons contributed by C1 and C2 are present in both slabs, demonstrating their ability to span the entirety of the monolayer. Considering that 2/3 of the electrons in a C1 molecule belongs to the diphenylethyl groups and the backbone ring, we suggest that the hydrophobic moieties of the peptoid macrocycle might be located within the upper part of the DPPG monolayer (167 electrons out of 249 per lipid molecule). The distribution of extra electrons corresponding to the L1 molecules is within the bottom slab, with an additional region of excess electron density underneath the lipid monolayer, indicating that some L1 molecules accumulate on the outer surface of the lipid film. L2, in turn, does not contribute any electron density to the modeled internal membrane region.

Cyclic peptoids also show an increased affinity for monolayers of truncated lipopolysaccharide mimicking the Gram-negative bacteria outer membrane. XR modeling implies that cyclic compounds are present within the upper slab of the kdo2-lipid A monolayer by contributing 76 and 74 additional electrons per lipid molecule, whereas both linear peptoids stay in the lower region only. Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram suggesting the potentially different modes of action for linear and cyclic peptoids with a focus on the outer portion of the bilayer system modeled by our Langmuir study.

Figure 5.

Suggested structural changes in the outer leaflet of the bacterial lipid membrane modeled by DPPG monolayers (A) after the insertion of linear (B) and cyclic (C) peptoids. Cyclization allows antimicrobial molecules to intercalate better with the lipid film characterized by the molecular tilt of alkyl chains and membrane thinning.

As monolayers used in this study are composed of saturated lipids exclusively, it is notable to mention that the disruptive activity of peptoids in a Langmuir model system reflects their interaction with the gel phase of natural membranes. The penetration depth and/or the partitioning of inserted molecules within the fluid phase of the lipid bilayer could vary on the basis of membrane fluidity.

4. DISCUSSION

Charge, hydrophobicity, amphipathicity, and size define the design space for small membrane-active antimicrobial molecules. It has been recently suggested that the conformational rigidity could be an additional critical parameter.24,55,56 Cyclization increases the molecular rigidity without large changes in other physiochemical properties.

Cyclic molecules should endure lower entropy loss upon incorporating into a lipid membrane as compared to their more flexible linear analogues. Inserting a molecule into a lipid membrane is associated with the packing perturbations in the lipid matrix. Energy gains in the system come from maximizing electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between lipids and antimicrobial molecules. The cumulative change in energy defines the membrane activity of a molecule.

The previously defined free energy associated with the transfer of a peptide from an aqueous solution to a lipid membrane (ΔG°) is contributed by a solvation free energy ΔG°solv, a lipid perturbation free energy ΔG°lip, and immobilization of the peptide ΔG°imm. According to the model employed by Jahnig, the immobilization term in̈ ΔG° can be defined by

| (1) |

The first term on the right-hand side of eq 1 is due to the loss of translational entropy, whereas the second term results from the loss of rotational entropy of the peptide in the membrane, as compared to in the solution.57

For the insertion of a 25-mer polyalanine α-helix with a length of dL = 30 Å into a lipid membrane, ΔG°imm was calculated as ΔG°imm,trans + ΔG°imm,rot ≈ 0.9 + 2.8 ≈ 3.7 kcal/ mol. This equals one-third of the negative contribution to ΔG° by ΔG°solv (∼−11 kcal/mol), which is the driving force for peptide insertion into the membrane.58

Considering this value to be similar or slightly lower for the less rigid peptoid hexamers, we estimate the entropy balance for their linear and cyclic configurations. The increase in conformational rigidity upon cyclization can be transferred to the molecular level as the loss of rotational degrees of freedom within the peptoid backbone. Cyclization halves the rotational degrees of freedom, and the entropy change accompanying the restriction of a single one is approximately 3 cal K−1 mol−1.59 Multiplied by 6, we define the entropy penalties associated with membrane insertion of a cyclic peptoid to be reduced by 18 cal K−1 mol−1 (∼4 kcal/mol). This roughly equals ΔG°imm of linear α-helical molecules and is sufficient to positively shift the cumulative energy balance for peptoid macrocycles. It is noteworthy that peptoid hexamers behave experimentally similar to hexapeptides as studied by MD simulations that further emphasizes the similarity in their structure−function relationships.33,34

5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Cyclic peptoids are found to inhibit bacterial growth better than their linear analogues. Electron microscopy on S. aureus cells demonstrates that both cyclic and linear peptoids disrupt the integrity of the bacterial cellular envelopes. X-ray scattering on Langmuir monolayers shows that cyclic peptoids demonstrate a higher affinity for anionic lipids than do their linear analogues. Our data provide evidence that cyclization increases the membrane activity of antimicrobial peptoid oligomers and shed light on their underlying mechanism of action. We suggest that the reduced conformational flexibility of cyclic antimicrobial molecules may bolster membrane-penetrating activity, potentially leading to superior membrane-disruptive behavior. We anticipate that these findings, combined with the simplicity of the cyclization approach, will facilitate the rational design of new families of oligomeric antimicrobial agents.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the NIH (R01 AI073892, D.G.), NSF (CHE-1507946, K.K.), and DARPA (W911NF-091-378, D.G.). ChemMatCARS Sector 15 is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number NSF/CHE-1346572. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. M.W.M. was partially supported by the NSF via a fellowship through the Adler Planetary & Astronomy Museum.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03477.

Expansion of the lipid surface area upon peptoid insertion and X-ray reflectivity of C2 vs L2 (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Walsh C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 1 (1), 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415 (6870), 389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Diamond G; Beckloff N; Weinberg A; Kisich KO. The roles of antimicrobial peptides in innate host defense. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15 (21), 2377–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Peters BM; Shirtliff ME; Jabra-Rizk MA. Antimicrobial peptides: primeval molecules or future drugs? PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6 (10), e1001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hancock RE; Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24 (12), 1551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Tew GN; Liu D; Chen B; Doerksen RJ; Kaplan J; Carroll PJ; Klein ML; DeGrado WF. De novo design of biomimetic antimicrobial polymers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (8), 5110–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Tew GN; Clements D; Tang H; Arnt L; Scott RW. Antimicrobial activity of an abiotic host defense peptide mimic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2006, 1758 (9), 1387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Porter EA; Weisblum B; Gellman SH. Mimicry of host-defense peptides by unnatural oligomers: antimicrobial beta-peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124 (25), 7324–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Radzishevsky IS; Rotem S; Bourdetsky D; Navon-Venezia S; Carmeli Y; Mor A. Improved antimicrobial peptides based on acyl-lysine oligomers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25 (6), 657–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Simon RJ; Kania RS; Zuckermann RN; Huebner VD; Jewell DA; Banville S; Ng S; Wang L; Rosenberg S; Marlowe CK; et al. Peptoids: a modular approach to drug discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89 (20), 9367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kirshenbaum K; Barron AE; Goldsmith RA; Armand P; Bradley EK; Truong KT; Dill KA; Cohen FE; Zuckermann RN. Sequence-specific polypeptoids: a diverse family of heteropolymers with stable secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95 (8), 4303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Dohm MT; Kapoor R; Barron AE. Peptoids: bio-inspired polymers as potential pharmaceuticals. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17 (25), 2732–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Goodson B; Ehrhardt A; Ng S; Nuss J; Johnson K; Giedlin M; Yamamoto R; Moos WH; Krebber A; Ladner M; Giacona MB; Vitt C; Winter J. Characterization of novel antimicrobial peptoids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43 (6), 1429–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Seo J; Ren G; Liu H; Miao Z; Park M; Wang Y; Miller TM; Barron AE; Cheng Z. In vivo biodistribution and small animal PET of (64)Cu-labeled antimicrobial peptoids. Bioconjugate Chem. 2012, 23 (5), 1069–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Fowler SA; Blackwell HE. Structure-function relationships in peptoids: Recent advances toward deciphering the structural requirements for biological function. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7 (8), 1508–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Katsu T; Kuroko M; Morikawa T; Sanchika K; Fujita Y; Yamamura H; Uda M. Mechanism of membrane damage induced by the amphipathic peptides gramicidin S and melittin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1989, 983 (2), 135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rathinakumar R; Walkenhorst WF; Wimley WC. Broadspectrum antimicrobial peptides by rational combinatorial design and high-throughput screening: the importance of interfacial activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (22), 7609–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: Pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3 (3), 238–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Sato H; Feix JB. Peptide-membrane interactions and mechanisms of membrane destruction by amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2006, 1758 (9), 1245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jiang Z; Vasil AI; Hale JD; Hancock RE; Vasil ML; Hodges RS. Effects of net charge and the number of positively charged residues on the biological activity of amphipathic alpha-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 2008, 90 (3), 369–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Giangaspero A; Sandri L; Tossi A. Amphipathic alpha helical antimicrobial peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268 (21), 5589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yin LM; Edwards MA; Li J; Yip CM; Deber CM. Roles of hydrophobicity and charge distribution of cationic antimicrobial peptides in peptide-membrane interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287 (10), 7738–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Irudayam SJ; Pobandt T; Berkowitz ML. Free energy barrier for melittin reorientation from a membrane-bound state to a transmembrane state. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117 (43), 13457−13463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ivankin A; Livne L; Mor A; Caputo GA; DeGrado WF; Meron M; Lin B; Gidalevitz D. Role of the conformational rigidity in the design of biomimetic antimicrobial compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49 (45), 8462–8465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Liu L; Fang Y; Huang QS; Wu JH. A rigidity-enhanced antimicrobial activity: a case for linear cationic alpha-helical peptide HP(2−20) and its four analogues. PloS One 2011, 6 (1). 10.1371/journal.pone.0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Craik DJ. Chemistry. Seamless proteins tie up their loose ends. Science 2006, 311 (5767), 1563–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Wu HF; Niu YH; Padhee S; Wang RSE; Li YQ; Qiao Q; Bai G; Cao CH; Cai JF. Design and synthesis of unprecedented cyclic gamma-AApeptides for antimicrobial development. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3 (8), 2570–2575. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Fernandez-Lopez S; Kim HS; Choi EC; Delgado M; Granja JR; Khasanov A; Kraehenbuehl K; Long G; Weinberger DA; Wilcoxen KM; Ghadiri MR. Antibacterial agents based on the cyclic D,L-alpha-peptide architecture. Nature 2001, 412 (6845), 452–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Shin SB; Yoo B; Todaro LJ; Kirshenbaum K. Cyclic peptoids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (11), 3218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yoo B; Shin SBY; Huang ML; Kirshenbaum K. Peptoid macrocycles: making the rounds with peptidomimetic oligomers. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16 (19), 5528–5537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Junkes C; Wessolowski A; Farnaud S; Evans RW; Good L; Bienert M; Dathe M. The interaction of arginine- and tryptophanrich cyclic hexapeptides with Escherichia coli membranes. J. Pept. Sci. 2008, 14 (4), 535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Oren Z; Shai Y. Cyclization of a cytolytic amphipathic alphahelical peptide and its diastereomer: effect on structure, interaction with model membranes, and biological function. Biochemistry 2000, 39 (20), 6103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Mika JT; Moiset G; Cirac AD; Feliu L; Bardaji E; Planas M; Sengupta D; Marrink SJ; Poolman B. Structural basis for the enhanced activity of cyclic antimicrobial peptides: the case of BPC194. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2011, 1808 (9), 2197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cirac AD; Moiset G; Mika JT; Kocer A; Salvador P; Poolman B; Marrink SJ; Sengupta D. The molecular basis for antimicrobial activity of pore-forming cyclic peptides. Biophys. J. 2011, 100 (10), 2422–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Huang ML; Shin SBY; Benson MA; Torres VJ; Kirshenbaum K. A comparison of linear and cyclic peptoid oligomers as potent antimicrobial agents. ChemMedChem 2012, 7 (1), 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 7th ed. Approved Standard CLSI document M07- A7, CLSI, Wayne, IN, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Neville F; Cahuzac M; Konovalov O; Ishitsuka Y; Lee KY; Kuzmenko I; Kale GM; Gidalevitz D. Lipid headgroup discrimination by antimicrobial peptide LL-37: insight into mechanism of action. Biophys. J. 2006, 90 (4), 1275–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Ege C; Lee KY. Insertion of Alzheimer’s A beta 40 peptide into lipid monolayers. Biophys. J. 2004, 87 (3), 1732–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hartmann M; Berditsch M; Hawecker J; Ardakani MF; Gerthsen D; Ulrich AS. Damage of the bacterial cell envelope by antimicrobial peptides gramicidin S and PGLa as revealed by transmission and scanning electron microscopy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (8), 3132–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kjaer K. Some simple ideas on X-Ray reflection and grazingincidence diffraction from thin surfactant films. Phys. B 1994, 198 (1−3), 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Danauskas SM; Li DX; Meron M; Lin BH; Lee KYC. Stochastic fitting of specular X-ray reflectivity data using StochFit. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Andreev K; Bianchi C; Laursen JS; Citterio L; Hein-Kristensen L; Gram L; Kuzmenko I; Olsen CA; Gidalevitz D. Guanidino groups greatly enhance the action of antimicrobial peptidomimetics against bacterial cytoplasmic membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2014, 1838 (10), 2492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Huang ML; Benson MA; Shin SBY; Torres VJ; Kirshenbaum K. Amphiphilic cyclic peptoids that exhibit antimicrobial activity by disrupting Staphylococcus aureus membranes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2013 (17), 3560–3566. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Konovalov O; Myagkov I; Struth B; Lohner K. Lipid discrimination in phospholipid monolayers by the antimicrobial frog skin peptide PGLa. A synchrotron X-ray grazing incidence and reflectivity study. Eur. Biophys. J. 2002, 31 (6), 428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Brockman H. Lipid monolayers: why use half a membrane to characterize protein-membrane interactions? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999, 9 (4), 438–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Brown RE; Brockman HL. Using monomolecular films to characterize lipid lateral interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 398, 41–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Gidalevitz D; Ishitsuka Y; Muresan AS; Konovalov O; Waring AJ; Lehrer RI; Lee KY. Interaction of antimicrobial peptide protegrin with biomembranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100 (11), 6302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Neville F; Ivankin A; Konovalov O; Gidalevitz D. A comparative study on the interactions of SMAP-29 with lipid monolayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2010, 1798 (5), 851–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Marsh D. Lateral pressure in membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Rev. Biomembr. 1996, 1286 (3), 183–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Travkova OG; Andra J; Mohwald H; Brezesinski G. Influence of arenicin on phase transitions and ordering of lipids in 2D model membranes. Langmuir 2013, 29 (39), 12203−12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Neville F; Ishitsuka Y; Hodges CS; Konovalov O; Waring AJ; Lehrer R; Lee KY; Gidalevitz D. Protegrin interaction with lipid monolayers: Grazing incidence X-ray diffraction and X-ray reflectivity study. Soft Matter 2008, 4 (8), 1665–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Nobre TM; Martynowycz MW; Andreev K; Kuzmenko I; Nikaido H; Gidalevitz D. Modification of Salmonella lipoplysaccharides prevents the outer membrane penetration of novobiocin. Biophys. J. 2015, 109 (12), 2537–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Helm CA; Mohwald H; Kjaer K; Alsnielsen J. Phospholipid monolayer density distribution perpendicular to the water-surface - a synchrotron X-Ray reflectivity study. Europhys. Lett. 1987, 4 (6), 697–703. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Alsnielsen J; Jacquemain D; Kjaer K; Leveiller F; Lahav M; Leiserowitz L. Principles and applications of grazing-incidence X-Ray and neutron-scattering from ordered molecular monolayers at the air-water-interface. Phys. Rep. 1994, 246 (5), 252–313. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Martin SF. Preorganization in biological systems: Are conformational constraints worth the energy? Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79 (2), 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Fernandez-Vidal M; White SH; Ladokhin AS. Membrane partitioning: ″classical″ and ″nonclassical″ hydrophobic effects. J. Membr. Biol. 2011, 239 (1−2), 5−14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Jahnig F. Thermodynamics and kinetics of protein incorporation into membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1983, 80 (12), 3691–5.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Ben-Shaul A; Ben-Tal N; Honig B. Statistical thermodynamic analysis of peptide and protein insertion into lipid membranes. Biophys. J. 1996, 71 (1), 130–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Enck S; Kopp F; Marahiel MA; Geyer A. The entropy balance of nostocyclopeptide macrocyclization analysed by NMR spectroscopy. ChemBioChem 2008, 9 (16), 2597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.