Abstract

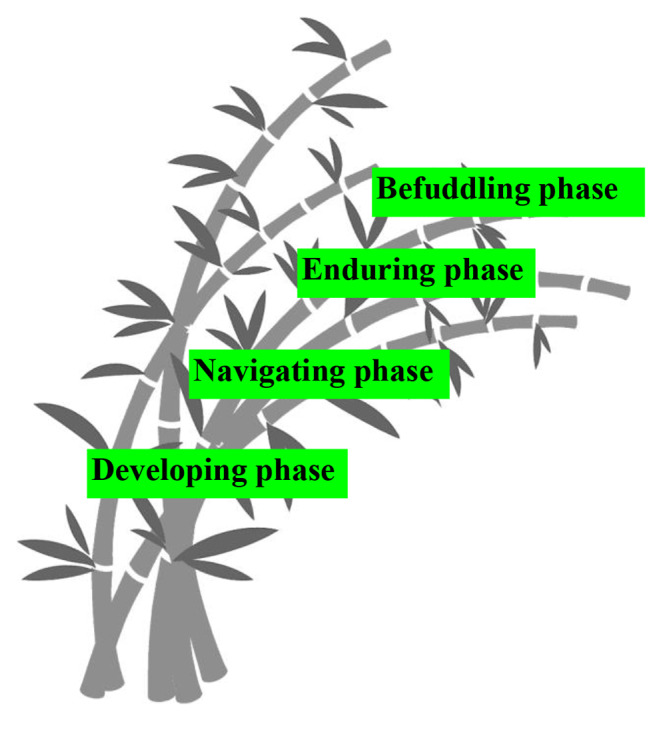

The impact of the global health crisis on students’ mental health has been well documented. While most of the studies looked into the psychological impact of the coronavirus disease, the process of coping with psychological distress as experienced by university students in the Philippines remains unexamined. Cognizant of the dearth in literature, this grounded theory study purports to investigate and understand the coping processes among 20 Filipino university students. A comprehensive model highlights Filipino university students’ coping techniques with psychological distress through vertical and horizontal analysis of the field text, open, axial, and selective coding. To ensure the trustworthiness and truthfulness of the theory and for refinement and consistency, triangulation, peer debriefing, and member checking validation strategies were likewise employed. The novel and distinct B.E.N.D. Model of Coping with Psychological Distress illustrates a substantive four-phased process symbolic of the challenges that a bamboo tree underwent, namely: (1) Befuddling Phase, (2) Enduring Phase, (3) Navigating Phase, and (4) Developing Phase. The phases that emerged had the advanced appreciable understanding of the university students’ coping processes that may provide evidence-based information in crafting programs and specific interventions to support and safeguard students’ mental health.

Keywords: Filipino university students, Psychological distress, Coping strategy, Theory of coping, Global health crisis

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) brought about a pandemic that negatively impacted individuals’ mental health (Sameer et al., 2020). It led to the experience of psychological stress, fear (Arvidsdotter et al., 2016), accumulated anxiety, and worries about health. The pandemic has led to significant psychological distress for everyone. Psychological distress (PD) is a state of poor psychological well-being, characterized by undifferentiated mixtures of symptoms extending from depression and anxiety symptoms (Drapeau et al., 2012). Its occurrence is detrimental to mental health and well-being (Deasy et al., 2014) and needs prevention and early intervention measures.

Young people, particularly university students, are at greater risk for psychological distress in health emergencies (Bert et al., 2020) and traumatic events (Villani et al., 2021). Previous studies have reported that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, university students experienced mental health challenges (Mudenda, 2021; Cao et al., 2020) and high levels of psychological distress (Hughes et al., 2022; Akbar & Aisyawati, 2021). Psychological distress was identified as the most prevalent mental health problem for university students (Gibbons et al., 2019). Anxiety, depression, and stress are among the psychological issues university students experience (Waseem et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2020; Aruta et al., 2022). Restrictions could have caused these psychological problems during pandemic-related lockdown (Alzueta et al., 2021).

Psychological distress poses a threat to the safety and well-being of university students. It is linked with risk behaviors and physical illness (Deasy et al., 2014), reduced students’ academic performance (Mudenda, 2021), and was strongly associated with suicide ideation and attempts (Eskin et al., 2016). Moreover, they are at risk for suicidal behavior and often search for information and news on the internet regarding self-harm and suicidal behavior (Solano et al., 2016). Additionally, measures of affective temperament types were more independently and strongly associated with negative clinical outcomes than a diagnosis of major affective disorder suggesting affective temperaments as possible contributors to university students’ psychological distress and suicidality (Baldessarini et al., 2017). What is alarming is that if it is experienced with high intensity on a long-term basis, the distress may jeopardize one’s mental health condition or lead to mental health disorders (Mubasyiroh et al., 2017).

As university students widely experience psychological distress, their way of coping is also of interest. In stressful situations, such as during a pandemic, coping behavior is an internal protective factor to overcome distress (Akbar & Aisyawati, 2021). Coping is a critical variable in reducing, minimizing, or tolerating stress (Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, 2013) and preventing psychological distress. There are adaptive or protective factors for psychological distress (e.g., social support) and maladaptive strategies to manage stress (e.g., escape/avoidance) employed by students (Chao, 2012).

Despite the needed attention devoted to young adults’ mental health needs (Eskin et al., 2016), they are at risk of experiencing frequent mental health issues and psychological concerns. Literature is scarce on the context of coping with psychological distress, particularly among Filipino university students. Although there are studies in the Philippines that dealt with university students; still, the focus of their investigations was the cause, effects of stress and coping mechanisms (Mazo, 2015), academic performance and coping mechanisms (Yazon et al., 2018), mental health literacy and mental health (Argao et al., 2021), psychological impact (Tee et al., 2020), distinct associations of fear of COVID-19 and financial difficulties, mediating role of psychological distress (Aruta et al., 2022) and the different factors linked with psychological distress (Marzo et al., 2020).

This present grounded theory design study is conceptualized to explore and develop a theory on coping with psychological distress culturally unique to Filipino university students during a global health crisis. Our grounded theory study will address the central question: “What theory explains the coping processes for psychological distress among a select group of Filipino university students? We believe that our current study will contribute to existing literature and deeply understand the phenomenon of coping with psychological distress, particularly in the Philippine context during the pandemic. The findings of this qualitative inquiry are expected to provide evidence-based information to students, parents, university officials, and mental health professionals that will aid them in understanding, developing, and strengthening programs and interventions that support and safeguard students’ mental health.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study was conducted using grounded theory as its research design, driven by the purpose to move beyond description and discover a theory, a “unified theoretical explanation“(Corbin & Strauss, 2007) for a process, particularly coping with psychological distress. Grounded theory, particularly the analytic procedure, was used to investigate the coping techniques of Filipino university students with psychological distress during the pandemic.

Participants

Eligible participants for this study were 20 university students who fulfilled the set inclusion criteria: (a) Filipino undergraduate students at selected universities in the National Capital Region (NCR), (b) enrolled during the Academic Year 2020–2021, (c) with ages 18 to 21 years old, and (d) had high levels of psychological distress. Those who did not give their consent, who were having prior mental health diagnoses, and with incomplete/missing responses in the measure were excluded from the study. Further, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-6 (K6) was used to screen the participants and those who were a high level of psychological distress were chosen to be part of the study. Our participant’s age ranges from 18 to 21 years old (M = 19.6; SD = 0.99), majority were female (n = 12; 60%), in a relationship (n = 15; 75%) and enrolled in BS Psychology program (n = 9; 45%).

Purposive sampling was used to intentionally select the participants representing the university students and give meaning to their lived experiences (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). McCrae and Purssell (2016) emphasized that to develop a theory, one must base it on theoretical concerns such as data saturation and not on the number of participants. Participation was voluntary and without remuneration. Each university student gave informed consent before completing the measures and participating in the interviews. Their willingness to answer the screening tool and their openness to sharing their experiences is essential in capturing the phenomenon’s essence under investigation.

Measures

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale-6 (K6). The K6 which is a short version of the K10 developed by Kessler and colleagues (2002) was used as a screening tool in selecting the participants. The K6 is a well-validated clinical measure, with good psychometric properties and is practical to use in assessing psychological symptoms (Krynen et al., 2013). It is a 6-item questionnaire that measures whether a person feels nervous, hopeless, restless, jumpy, sad, and worthless (e.g., “During the last 30 days, how often did you feel hopeless? “). Each item of the K6 self-report format is answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1-None of the time to 5-All of the time. The total score ranges from 1-to 30. Those whose sum scored from 1-to 15 were students experiencing a low level of psychological distress, while those who scored 16-to 30 were students experiencing high levels of psychological distress (Serrano et al., 2022). Participants experiencing a high level of psychological distress were used as a reference in selecting participants for the current study.

Robotfoto. The robotfoto was used in obtaining the basic demographic profile of each participant and was used to ensure that the participants met the predetermined inclusion criteria. It specifically sought the participant’s age, gender, course, relationship status, and course.

Aide-Memoire. The aide-memoire was an interview guide developed for the present study to direct the semi-structured interview to capture Filipino university students’ lived experiences. The interview guide is process-oriented, revolving around the participant’s experience (Villamor et al., 2016). The aide-memoire was guided by the central question: “What theory explains the coping processes for psychological distress among a select group of Filipino university students?

Procedure

The data gathering started after obtaining approval from the Ethics Board of the University of Santo Tomas Graduate School. Permission from the presidents of the universities was secured before participants’ recruitment and selection. Twenty participants were purposely selected who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Informed consent was sought from each participant before scheduling the virtual interview. The virtual interviews took place online via Zoom or Google Meet video or voice conferencing calls in a mutually agreed schedule by both parties. With the participants’ prior consent, video and audio recording was done to document the interview.

The initial minutes of the interview focused on building rapport as well as presentation of the nature and objectives of the study. Such practice was observed to ensure a more natural, honest and open atmosphere between the participants and the researchers. The interview progressed, using the aide-memoire as a guide, and additional questions were also raised other than the key questions further to explore the participants’ responses during the interview. Each interview lasted for one and a half hours, depending on the participant’s experience. Follow-up interviews were also conducted that lasted 40 min with most participants to understand the phenomenon under investigation in-depth. The entire data gathering process for the second phase lasted three to six weeks. Moreover, the information shared by the participants was assured with utmost confidentiality, objectivity, and anonymity by using pseudo initials in place of their actual names and other identifying details.

Data analysis followed immediately after data collection. Recorded narratives were individually transcribed verbatim in English and were subjected to open, axial, and selective coding following Corbin and Strauss (2007) analytical framework. Preliminarily, each verbalization was assigned condensed codes, and through open coding, both anchors and phenomenal referents from the field text were identified, forming categories. Second, relationships between and among categories were correlated from the open codes and categories identified themes . The data after open coding was assembled in new ways in axial coding. Finally, the identification of conceptual ideas that integrated the existing categories was made in selective coding. We were able to develop a comprehensive model that highlights the coping processes of Filipino university students with psychological distress. Moreover, the themes that emerged in this study were further subjected to triangulation, peer debriefing, and member checking validation strategies to employ refinement and consistency and ensure the trustworthiness and truthfulness of the theory. Reflexivity was likewise observed to ensure that no bias and subjective judgment influenced the qualitative interpretations.

Findings

Through analyzing the data of participants’ significant statements and verbalizations, the findings of this grounded theory study yielded the B.E.N.D. Model of Coping with Psychological Distress (See Fig. 1) consists of four distinct phases: (1) befuddling, (2) enduring, (3) navigating, and (4) developing phases. The model is likened to the processes that a bamboo tree goes through to survive during a storm, as it bends harmoniously in the angry blasts of the blustering wind, remaining standing tall and still. Verily, the university students were like bamboo. Even with the widespread havoc that the global health crisis has created, they use a bending, not breaking process to continuously adjust, adapt and cope with everyday vagaries of life.

Fig. 1.

B.E.N.D. Model of coping with psychological distress

(1) Befuddling Phase

In this study, the participants had a high level of psychological distress. Unsurprisingly, the drastic changes brought about by the global health crisis triggered the distressed experiences of students. They were emotionally and mentally disturbed as they faced an unusual situation. As participants shared,

“I have anxieties and fears; then the pandemic has brought me problems that I didn’t know existed. It feels like I’m inside a room and can’t do anything to get out. There are many ideas running through my head, but I can’t think clearly, which makes me upset.“ (P6)

”There’s an emptiness inside of me. It is very difficult, and it drives me crazy. I thought of stopping school because I lost focus on everything.“ (P13)

This experience is the onset of the process of the befuddling phase wherein Filipino university students collectively described themselves as facing a crisis, confused about whether to continue or discontinue their schooling as they were experiencing psychological distress. As participants articulated,

“I don’t know if I should go on or let go of my dreams. I’m at a point where I’m not sure what will I do or where am I going. It’s very hard on my part, and as if there’s no one that I can turn to.“ (P2).

“I feel very down, and it’s like I’m all by myself. I feel I’m at a crossroads. I want to continue, but I don’t know how.“ (P7).

Additionally, due to the abrupt change, participants were confronted with the feeling of self-doubt. They perceive themselves as weak in facing their distress, underestimating what they can do, as shared:

“I have the feeling that I am not doing much of anything. If I do something, I feel I am doing it wrong… It’s very hard for me to keep trying and trying.“ (P10).

“Life is difficult, and most of the time, I think I can’t make it. There are others who can do it, but who am I anyway? I am nowhere beyond perfection.“ (P9).

Besides self-doubt, participants also shared that they felt they were stuck, experiencing emptiness and losing direction in life. As verbalized:

“It’s really hard to get myself to focus. I feel I’m not doing anything to move forward. It’s very hard for me.“ (P16).

“There are days I’m emotionally flat, and I just want to be alone. I don’t want to engage in conversations or see anybody. I don’t even know where I am headed for.“ (P20).

Further, they engage in self-blame and even humiliate themselves. They even turn to vices to boost their self-esteem, as stated:

“I guess blaming myself to the point where it was unhealthy about different things. I feel weak and sometimes I calm myself by drinking some wine. At times it helps. It makes me feel more confident.“ (P3).

“When I think about many things, smoking calms me. I smoke without the knowledge of my parents. I know it’s bad for my health, but it ables me to become more confident in the choices I make.“ (P12).

However, it is interesting to note the participants make sense of their initial feelings. Their acknowledgment that they are torn between stopping schooling or furthering their education during the health crisis led them to reflect on how to adapt to the new normal and identify their sources of strengths as a factor for their distress experience. As participants shared,

“I know I just have to go with the flow, it’s never easy, but if I stop, my whole life will be worst. I need to continue. It’s difficult, but I must continue; I know my parents are there for me.“ (P8).

“My family keeps me going. The crisis I am into is indescribable, yet I have many reasons not to give up…others were also experiencing the same. Maybe I just need to change some things in my life…definitely, not giving up on my dreams in life.“ (P15).

The participants’ statements reveal that this phase is typified by their experiences of confusion, self-doubt, self-blame, and self-humiliation. Their distress was triggered by their struggles and difficulties as they find it hard to open themselves to what is new and what is different. They were trying their best to adapt and go with the flow by understanding the dynamics of the new normal situation.

(2) Enduring Phase

As the participants’ struggles and difficulties continued, they expressed their lives were full of twists and turns. It becomes complicated and unpredictable. They admitted that it was excruciating and fearful as shared:

“I thought it was easy at first, but it was difficult, very far from my imagination. I feel lonely and isolated. At night, all I can do is cry. It’s tearing me up inside.“ (P1).

“This part was tough, there were setbacks, and I was afraid. I’m disappointed in myself. What’s hard is I’m not thinking only about myself but also about the people around me. What will happen if I give up.“ (P4).

Aside from that, they also experience tensions all over; physiologically, emotionally, and mentally which affects their overall health, causing them to have infections and be hospitalized, as verbalized:

“My health is suffering; I have palpitations and signs of a panic attack. I hardly can’t breathe. My parents were alarmed, so I had to be brought to the hospital. Knowing the current scenario of the pandemic, my exposure to the virus, especially in the hospital, added to my fears. I have to take medicine to calm down my emotions.“ (P5).

“I know I’m experiencing stress because I develop rashes on my skin. I also had unnatural shedding of hair, as evident on lots of hair strands on my pillows in the morning. This makes me irritable at home. It was very shameful to admit, but others-especially my family were affected because of how I felt.“ (P19).

Consequently, their self-esteem becomes very low as their mind is bombarded with negative thoughts.

“I complain about everything and as if I don’t appreciate anything. I feel I’m not effective in doing anything, and if I do something, it is done poorly.“ (P2).

“There were embarrassments and discouragements. I feel blue about myself and my future. I have consistent worries and am depressed… I lack control over my situation, so everything that goes wrong is my fault.“ (P14).

This experience also affected the participants’ motivation to study and to lose courage, but they were also alarmed by the possible outcome as articulated:

“I feel I fail in achieving my goals. I’m not doing anything, so I fear that an undesirable outcome will be the results…” (P7).

“I am experiencing a great deal of sadness and stress…I have a lackluster attitude towards my studies. Anyway, it feels so hopeless and helpless.“ (P16).

They felt they had slowed progress in all aspects, and at times, they were stuck, as shared:

“I am disheartened because there’s no progress in anything that I want. If ever there is, it’s hard for me to pinpoint it.“ (P4).

“I feel disappointed because as if there’s no improvement in myself. I feel I’m not moving forward. It seems to take forever for progress to come around.“ (P18).

Notably, with all the participants’ experience of facing and overcoming difficult situations, it creates the confidence and resilience in them to deal with the things that go their way, as articulated in the following statements:

“It’s very hard, but I’m able to move on from the very painful circumstance. I take it as a challenge, and I go on believing in what I can do.“ (P8).

“When I discovered that the struggles of my friends were very similar to my struggles, it normalized my thoughts that students should go through this. What’s important is you’re doing something to move forward.“ (P17).

This enduring phase refers to the process by which the participants face personal and social circumstance which makes them suffer and prevent them from achieving their dreams. Still, they never quit, and an attitude is developed to keep going and decide not to give up on realizing their hidden strength and potential.

(3) Navigating phase

As the participants decided not to give up, they reflected on how they will continue to be in motion moving forward. They chose to be open to what is new and what is different, as verbalized:

“I reflect most of the time. Where am I now? What should I do? These are the questions I ask myself, and I ended up reminding myself to plan, strategize and learn.

I ask my friends often. If I do this and that, what will happen. I also asked them what they were doing. I’m trying it, and thanks to God, it works.“ (P11).

They established social connections to ease feelings of loneliness and increase their motivation and happiness. They started with their roots, their family, and relatives. They tried their best to get along with people. They realized that the challenge for them is to remain mobile and flexible and, at the same time, exert effort to become involved and deeply rooted in their own family and in the local community where they belong, as shared:

“What helps me the most is having a strong social support system-my family. What I am grateful for is that they are always there for me, especially at times wherein I feel very low. I am telling them everything that is happening to me, and I’m glad that they are very understanding.“ (P17).

“Connecting with someone and talking about school and life is really helpful. We have that group chat in our barangay wherein; as students, we share ideas and experiences. Honestly, It makes me feel better. It gives me the feeling that I belong. Sometimes just talking makes me feel better. I don’t have my parents, so I share my thoughts and experiences with my relatives.“ (P3).

They observe how they can do their best to be ready for any situation. As verbalized, university students engage in training and practice developing a state of being ever ready.

“I silently observe how others do it, then I try. I make myself ready. It was never easy, but I just went with the flow, and I don’t regret it…I feel I’m used to it. Whatever happens, I know I can adapt.“ (P16).

They empty their minds with their preconceived notions of anxiety and fear. They become open to possibilities and accommodate interests and preferences. They also accept that they do not need to be perfect, but only to be resilient. They become more creative and resilient through persistence and practice. They shared,

“I choose to be open to possibilities. It’s a rational choice. Maybe at times, I felt very weak, afraid, but I’m sure I’ll keep going.“ (P5).

“At first, I felt like I am alone in this situation. Hearing the sharing of my friends and classmates, it’s just really validating to hear from others that we all seem to be struggling with the same things.“ (P1).

“I expected too much from myself, but I learned to lower these expectations because it might kill me. What I expect now for myself is to survive from all of these as others were also doing.“ (P10).

They are motivated by feeling appreciated, and their progress is externally validated. They also adjust to adapt. Adaptation allowed them to broaden their perspective, as verbalized:

“It’s great to have solidarity in many things. Others were simply reminding me that I am doing great. They don’t know, but it means so much to me.“ (P15).

“Every day I try something new. I try to reinvent myself. This lets me feel I’m in motion and I’m deciding whether I move forward or backward in every circumstance that I have.“ (P11).

In this study, the navigating phase is the process where students establish connections, make observations and adaptations to overcome their psychological distress, and understand the dynamics of the new normal situation.

(4) Developing phase

Finally, the participants in this study arrived at the final stage of the coping process, the developing phase, wherein achieving a more “developed self” in various aspects of life becomes more evident. The participants were one to claim that they first recognized the need to identify areas where they wanted to improve within themselves. They shared:

I’m using a journal, listing down my personal qualities. I reflect from within. Admitting my weaknesses was the hardest thing to do…It always makes me cry. But then, I have in mind, clearly, what should I do or change.“ " (P14).

“I lacked the knowledge of the technological aspect before, but I did I tried to master the use of gadgets and the internet, which helped me in my tasks and increased my performance at school. " (P13).

Consequently, once the participants were already aware of the areas that need betterment, they also have a more precise grasp of the contributory factors to their distress experience, which they need to overcome.

“Fear is what I have; this causes me to panic, experience anxiety, and overthink. I believe that fear prevents me from growing and progressing. It hinders me to do whatever I have in my mind and learning to overcome it is really a big deal for me. " (P12).

“At some point, I was afraid to change. What if it goes wrong? But I pulled myself together and started to do something about my situation. " (P9).

They are one in believing advocacy for work-life balance as this reduces their distress and increases their motivation to perform their responsibilities as students. As shared:

“I give myself time, a space. Sometimes, after long periods of time studying and working on my school projects, I feel unmotivated. I make sure to take a break and recharge. I’m reminding myself to take a deep breath, take it easy. " (P13).

The participants expressed that self-guided improvement is a must in developing themselves and enhancing their skills and characteristics. They were committed to continuous learning and improvement. It may not be giant leaps and bounds, but quite remarkable as a sign of growth and improvement. They started to see their capabilities and embrace their weaknesses. They shared:

“I give myself random rewards for even my simplest achievement and accomplishments. This way, I make myself motivated to get my task completed. It really feels good inside. " (P1).

“I include in my habit or as part of my daily life reading books, watching videos on the internet, and collecting relevant pieces of information that I can use. " (P18).

They set realistic goals and gradually achieve their aspirations in life. They claim they struggle a lot, but they succeed by broadening their perspective and signifying a commitment to change. They shared:

“When doing my schoolwork, the single best thing that I do is to ensure that I am not falling behind schedule. what I’m doing is breaking down my tasks into small and easily achievable tasks with a set deadline. " (P3).

“When I begin to set goals, I know myself…so I don’t overwhelm myself. I consider my strengths and weaknesses, limitations, and capacity. I’m also telling it to others. For me, telling someone we know about our goals also seems to increase the likelihood that we will stick to them. " (P12).

The participants were very hopeful about achieving their goals. They also track their progress each day. Understand what motivates them, what distracts them, and how they best perform and become more productive at school. They were not discouraged by what they perceived as their lacking potential. Instead, their main concern is implementing proactive actions and moving forward. They also reflect if they seem to get going or if there is a need for additional support.

“I write my goals and constantly check on how far I have accomplished. At times, I realized my movement is not always forward. So, I reflect and try to recall what went wrong. Identifying what’s wrong, I seek advice from my friends. There I will realize what I need to do. " (P7).

The participants shared that it was never easy and very challenging. However, they are determined to do it as they recognize it is for their future. They also developed the skills of mindset reappraisal, which they believe would help them persevere in their education and later in life. They shared,

“It’s always a struggle, but nobody will do it for me. I try to listen to myself most of the time. I also talk about my feelings. You know, talking about my feelings keeps me sane and helps me deal with times I feel troubled.“ (P18).

“There were a few hurdles where I would get upset, yet giving up is not an option. If I feel I must do it, I will be doing it. No regrets. It’s like every day; I reinvent myself. I have the feeling of happiness and excitement in everything that I do. I am in motion, and I know it’s for my future.“ (P11).

They also enhanced their relationships with others and seeking social support. Participants felt that they were being cared for as a whole person, as verbalized:

“I ensure that I maintain close communication with people important to me. Whether my experiences or feelings are good or bad, I share them with them. They always support me, and this helps me ease my burden.“ (P5).

Also, enhancing their spirituality and devotion to God helped them deal successfully with their problems and difficulties. With this, they could find meaning even during the most challenging times, go with the flow without resistance, and feel at peace.

“I always involved myself in praying activities. There were prayer chains in my chat groups and even novena with my family in messenger. It calms me and lightens my burdens in life.“ (P1).

“If I find myself bored in a task that I’m doing, I pray. I also attend online-based masses. This enlightens me and motivates me to avoid piled up works left unfinished…” (P14).

Summarily, the developing phase is indicative of the coping process in dealing with psychological distress and the participants’ empowerment to thrive and survive. This last phase is recreating themselves and beginning to develop new attitudes while freeing themselves from preconceived notions causing them to be distressed, such as fear and uncertainties. They were also exploring and opening rooms for greater possibilities and adapting to what is new and what is different.

Discussion

This grounded theory inquiry successfully afforded the emergence of the substantive B.E.N.D. Model of Coping with Psychological Distress. A model that involves four distinct yet interrelated phases: befuddling, enduring, navigating, and developing. This four-phased theoretical model provides a valuable aid in understanding the manner Filipino university students underwent in coping with psychological distress during a global health crisis. The B.E.N.D. Model of Coping with Psychological Distress could be used to design proactive interventions, specifically for university students.

The first phase, the befuddling phase, describes how university students acknowledge the crisis they are into, between continuing or discontinuing their education despite the psychological and mental disturbances they were experiencing. At the onset, the participants in this study admitted that their distress was triggered by their academic concerns, such as increased workload (Realyvásquez-Vargas et al., 2020), the volume of assignments given (Al-Salman & Haider, 2021), and lack of guidance in every aspect of their lives. The drastic changes brought about by the global health crisis made university students struggle and encounter difficulties. However, the potential impact of the health crisis is still unknown as it is described as an exceptional and novel situation (Baltà-Salvador et al., 2021). In their study, Barrot and colleagues (2021) posited that the global health crisis impacted the quality of the learning experience and students’ mental health. It has also brought university students various mental health challenges and psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, and stress (Khan et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020).

Since university students are preoccupied with their problems, this study also revealed the widespread belief that students turn to vices and engage in stress eating to feel better and boost their self-esteem. Moreover, the crisis has significantly influenced the behavior of university students, which reduced their motivation and even lost direction in life, as they feel helpless, uncertain, and have self-doubts (Yilmaz et al., 2020). This study supports the findings of empirical research that highlighted students’ difficulties which affected their academic performance, making them less motivated and intensifying their negative feelings such as anger, fear, worry, boredom, stress, anxiety, and frustration (Gillis & Krull, 2020; Aristovnik et al., 2020).

In light of the findings from this study, the university students who experienced psychological distress felt that they were stuck; they experienced confusion, emptiness, and losing direction in life. They are prone to drop out of school which made them at higher risk for academic failure (Ishii et al., 2018) as their education and career plans have been affected negatively. University students find it hard to open themselves to what is new and different. Still, they were trying their best to adapt and go with the flow by understanding the dynamics of the new normal situation. They embraced their emotions, whatever they are, and they shared it is comparable to welcoming oneself.

Interestingly, university students suffering from this global health crisis leads them to be aware of the need to seek any source of support from others. In the navigating phase, the coping process is generally characterized by university students actively dealing with the distressful situation by seeking help from others, seeking external validations, and making some observations. They observed that it is necessary to have social connections to ease feelings of loneliness and increase their motivation and happiness. This finding runs parallel with the results of previous literature that students’ coping mechanism was fulfilled by seeking support from others, especially informal social support, such as material or emotional support, which has a significant impact on their ability to overcome distress (Bøen et al., 2012; Son et al., 2020). Moreover, Taylor (2015) found out that social support reduced cortisol response to stress and improved immunity. Receiving support, getting along with others, and feeling appreciated both in person or virtually can foster bonding and bridging social connections (Robin & Tiechty , 2020; Jones et al., 2020). These experiences have a powerful effect on helping the participants cope with distress as this gives them external validation and a sense of comfort and stability. On the contrary, passive coping and not having somebody as a source of social support during a health crisis result in high psychological distress (Yu et al., 2020).

Finally, the university student participants eventually realize that they will attain total adjustment and adaptation to their psychological distress experienced in the developing phase. They shifted their thoughts from catastrophizing to a more helpful mindset, increasing their well-being, decreasing negative health symptoms, and boosting physiological functioning (Crum et al., 2017). They were challenged but still determined, as they paid attention to their feelings, thoughts, and behaviors to identify their goal-related obstacles (Kreibich et al., 2020). University students accepted themselves with imperfections and uniqueness and were prone to stresses and challenges. The findings in this study fit well with previous literature reporting that thought-provoking circumstances, such as the global health crisis lead the way for positive impacts such as increased motivation and enhanced performance (Rheinberg & Engeser, 2018, Gonzalez et al., 2020), as students set and achieve their goals.

On the one hand, this investigation infers that a small amount of stress can also be significant. The right sort of stress encourages university students to make some changes in their lives and progress, preventing them from experiencing more severe psychological distress. On the other hand, if university students cannot adapt to stress successfully, they can feel burdensome (Ganesan et al., 2018). Their learning experience is disrupted (Kapasia et al., 2020), and they are prone to experiencing mental health problems and societal dysfunction associated with suicide (Tang et al., 2018).

Consequently, the university students also built positive relationships with others, which served as their social support avenue. Building positive relationships lowered the level of loneliness (Bernardon et al., 2011) and fostered a sense of hope, purpose, and meaning. Specifically, support from peers protects the mental health of university students’ (Alsubaie et al., 2019). Surprisingly, family support which has great importance on life satisfaction of the participants, becomes less influential and critical than peer support (Alsubaie et al., 2019; Kim, 2020), because they have more frequent interactions and similar experiences with their peers than their families (Bernardon et al., 2011).

Further, as university students continuously adapt and improve, they also ensure the balance between studying and relaxing, hence they engage in recreational activities (Fawaz et al., 2021). Moreover, they undertake self-diverting actions and engage in spiritual activities through prayers and meditation . All of these then lead to the university students’ continuous use of coping strategies, which, in turn, improved their efficiency for adjustment and adaptation to achieve a more developed self in various aspects of their lives.

Conclusion, theoretical contributions, and practical implications

This grounded theory study was purported to explore and develop a theoretical model on the coping processes culturally unique to Filipino university students during a global health crisis. Interestingly, the substantive B.E.N.D. Model of Coping with Psychological Distress that emerged from this present study vividly describes the phases of coping processes symbolic of the challenges that a bamboo tree underwent, namely, befuddling, enduring, navigating, and developing phases.

The findings of this current study extend some relevant implications, most especially to university students’ behavior, theory, research, and practice. The data was collected during times of uncertainty and crisis. An alarming rate of psychological distress among students was reported, thereby questioning the preparedness and implementation of mitigation measures and proactive strategies in universities to lessen or prevent the distress experiences of students. The phases that emerged had an advanced appreciable understanding of the university students coping experiences that helped them improve during the health crisis. Universities must ensure preventive programs so that students suffering from psychological distress will be identified and given proper intervention to prevent other problems.

Furthermore, our research is novel, and to the best of our knowledge, no prior studies on Filipino university students during the global health crisis have considered the process of coping with psychological distress. Finally, this investigation offers evidence-based information that can be used by future researchers, practitioners, and mental health advocates. Our study can help them design and craft intervention programs, policies, and guidelines that will address the psychological distress of university students and enhance their ability to cope.

This study was limited to students of the National Capital Region of the Philippines only and the researchers recommend a broader coverage of participants, such as but not limited to public and private universities nationwide, and compared the findings in different cultural contexts. Moreover, a follow-up study may also be conducted with the same participants to determine the sustainability of the emerging process.

Finally, the findings of this study gave a proposed model that may serve as a basis in crafting specific interventions for university students’ distress which was not provided in this study. Likewise, psychologists and other mental health practitioners handling cases of university students’ psychological distress have given an idea of their coping processes.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Statements and declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in the present study that involved human participants were per the ethical standards of the Ethics Board of the University of Santo Tomas Graduate School.

Consent to participate

Each participant in the current study gave informed consent before voluntary participation. In addition, participants were briefed on the nature of the study, were assured that all data collected would be kept confidential, and that participation was purely voluntary without remuneration.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akbar Z, Aisyawati MS. Coping strategy, social support, and psychological distress among university students in Jakarta, Indonesia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:694122. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.694122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salman S, Haider AS. Jordanian University Students’ Views on Emergency Online Learning during COVID-19. Online Learning. 2021;25(1):286–302. doi: 10.24059/olj.v25i1.2470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaie M, Stain H, Webster L, Wadman R. The role of sources of social support on depression and quality of life for university students. International Journal of Adolescent and Youth. 2019;24:484–496. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1568887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos-Usuga D, Yuksel D, Arango-Lasprilla JC. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2021;77(3):556–570. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8438. doi: 10.3390/su12208438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruta J, Callueng C, Antazo B, Ballada C. The mediating role of psychological distress on the link between socio-ecological factors and quality of life of Filipino adults during COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Community Psychology. 2022;50(2):712–726. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsdotter T, Marklund B, Kylen S, Taft C, Ekman I. Understanding persons with psychological distress in primary health care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2016;30:687–694. doi: 10.1111/scs.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ, Innamorati M, Erbuto D, Serafini G, Fiorillo A, Amore M, Girardi P, Pompili M. Differential associations of affective temperaments and diagnosis of major affective disorders with suicidal behavior. Journal of affective disorders. 2017;210:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltà-Salvador Rosó, Olmedo-Torre Noelia, Peña Marta, Renta-Davids Ana-Inés. Academic and emotional effects of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic on engineering students. Education and Information Technologies. 2021;26(6):7407–7434. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10593-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrot J, Llenares I, Del Rosario L. Students’ online learning challenges during the pandemic and how they cope with them: The case of the Philippines. Education and information technologies. 2021;26(6):7321–7338. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10589-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardon S, Babb K, Hakim-Larson J, Gragg M. Loneliness, attachment, and the perception and use of social support in university students. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2011;43:40–51. doi: 10.1037/a0021199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bert F, Lo Moro G, Corradi A, Acampora A, Agodi A, Brunelli L. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Italian medical students: The multicentre cross-sectional “PRIMES” study. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bøen H, Dalgard OS, Bjertness E. The importance of social support in the associations between psychological distress and somatic health problems and socio-economic factors among older adults living at home: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;33:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RCL. Managing perceived stress among college students: The roles of social support and dysfunctional coping. Journal of College Counselling. 2012;15:5–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2012.00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Akinola M, Martin A, Fath S. The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety Stress & Coping. 2017;30(4):379–395. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2016.127558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deasy C, Coughlan B, Pironom J, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: A mixed-method Inquiry. Plos One. 2014;9(12):e115193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau, A., Marchand, A., & Beaulieu-Prévost, D. (2012). Epidemiology of psychological distress. In Mental Illnesses - understanding, prediction, and control. IntechOpen, 105–134. 10.5772/30872

- Eskin M, Voracek M, Tran T, Sun J, Janghorbani M, Giovanni Carta M, Harlak H. Suicidal Behavior and Psychological Distress in University Students: A 12-Nation Study. Archives of Suicide Research. 2016;20(3):369–388. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1054055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz, M., Al Nakhal, M., & Itani, M. (2021). COVID-19 quarantine stressors and management among Lebanese students: A qualitative study. Current Psychology,1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ganesan Y, Talwar P, Norsiah F, Oon YB. A study on stress level and coping strategies among undergraduate students. Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development. 2018;3(2):37–47. doi: 10.33736/jcshd.787.2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons S, Trette-McLean T, Crandall A, Bingham JL, Garn CL, Cox JC. Undergraduate students survey their peers on mental health: Perspectives and strategies for improving college counseling center outreach. Journal of American College Health. 2019;67:580–591. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1499652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis A, Krull LM. COVID-19 Remote Learning Transition in Spring 2020: Class Structures, Student Perceptions, and Inequality in College Courses. Teaching Sociology. 2020;48(4):283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez T, De La Rubia MA, Hincz KP, Comas-Lopez M, Subirats L, Fort S, Sacha GM. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. Plos One. 2020;15(10):e0239490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustems–Carnicer J, Calderón C. Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2013;28(4):1127–1140. doi: 10.1007/s10212-012-0158-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. W., Vander Horst, A., Gibson, G. C., Cleveland, K. A., Wawrosch, C., Hunt, C., Granot, M., & Woolverton, C. J. (2022). Psychological distress of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health, 2022 Feb23, 1–3. Advance online publication. 10.1080/07448481.2021.1920953 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ishii T, Tachikawa H, Shiratori Y, Hori T, Aiba M, Kuga K, Arai T. What kinds of factors affect the academic outcomes of university students with mental disorders? A retrospective study based on medical records. Asian J Psychiatry. 2018;32:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Beardmore A, Biddle M, Gibson A, Ismail S, McClean S, White J. Apart but not Alone? A cross-sectional study of neighbour support in a major UK urban area during the COVID-19 lockdown. Emerald Open Research. 2020;2:37. doi: 10.35241/emeraldopenres.13731.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapasia N, Paul P, Roy A, Saha J, Zaveri A, Mallick R, Chouhan P. Impact of lockdown on learning status of undergraduate and postgraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in West Bengal. India Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;116:105194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Andrews G, Colpe L, Hiripi E, Mroczek D, Normand S, Walters E, Zaslavsky A. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Sultana M, Hossain S, Hasan M, Ahmed H, Sikder M. The impact ofCOVID-19 pandemic on mental health & well-being among home-quarantined Bangladesh students: A cross-sectional pilot study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC. Friends support as a mediator in the association between depressive symptoms and self-stigma among university students in South Korea. International Journal of Mental Health. 2020;49:247–253. doi: 10.1080/00207411.2020.1781425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich A, Hennecke M, Brandstätter V. The Effect of Self-awareness on the Identification of Goal‐related Obstacles. European Journal of Personality. 2020 doi: 10.1002/per.2234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krynen A, Osborne D, Duck I, Carla A, Houkamau C, Sibley A. Measuring psychological distress in New Zealand: Item response properties and demographic differences in the Kessler-6 screening measure. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2013;42:95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Marzo R, Quilatan Villanueva III, Martinez Faller E, Moralidad Baldonado A. Factors Associated with Psychological Distress among Filipinos during Coronavirus Disease-19 Pandemic Crisis. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020;8(T1):309–313. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2020.5146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- N. Mazo Generoso. Causes, Effects of Stress and the Coping Mechanism of the Bachelor of Science in Information Technology Students in a Philippine University. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn) 2015;9(1):71–78. doi: 10.11591/edulearn.v9i1.1295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae N, Purssell E. Is it really theoretical? A review of sampling in grounded theory studies in nursing journals. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016;72(10):2284–2293. doi: 10.1111/jan.12986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubasyiroh R, Suryaputri I, Tjandrarini D. Determinan Gejala Mental Emosional Pelajar SMP-SMA di Indonesia Tahun 2015. Buletin Penelitian Kesehatan. 2017;45(2):103–112. doi: 10.22435/bpk.v45i2.5820.103-112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mudenda, S. (2021). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its psychological impact on the Bachelor of Pharmacy Students at the University of Zambia. Academia Letters, 837. 10.20935/AL837

- Realyvásquez-Vargas A, Maldonado-Macías AA, Arredondo-Soto KC, Baez-Lopez Y, Carrillo-Gutiérrez T, Hernández-Escobedo G. The impact of environmental factors on academic performance of university students taking online classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):9194. doi: 10.3390/su12219194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rheinberg F, Engeser S. Intrinsic motivation and flow. In: Heckhausen J, Heckhausen H, editors. Motivation and action. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. pp. 579–622. [Google Scholar]

- Robin L, Tiechty L. The Hogwarts Running Club and sense of community: A netnography of a virtual community. Leisure Sciences Routledge. 2020;0:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sameer AS, Khan MA, Nissar S, Banday MZ. Assessment of Mental Health and Various Coping Strategies among general population living Under Imposed COVID-Lockdown Across world: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ethics Medicine And Public Health. 2020;15:100571. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, J., Reyes, M., & De Guzman, A. (2022). Psychological distress and coping of Filipino university students amidst a global pandemic: A Mixed-method study.Journal of Positive School Psychology. ISSN2717–7564.

- Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano, P., Ustulin, M., Pizzorno, E., Vichi, M., Pompili, M., Serafini, G., & Amore, M. (2016). A Google-based approach for monitoring suicide risk. Psychiatry Research,246:581–586. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.030. PMID: 27837725. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tang F, Byrne M, Qin P. Psychological distress and risk for suicidal behavior among university students in contemporary China. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;228:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S. E. (2015). Health Psychology. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Retrieved on December 22, 2021, from https://books.google.com/books/about/Health_Psychology.html?id=

- Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JP, Aligam K, Reyes P, Kuruchittham V, Ho RC. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. Journal of affective disorders. 2020;277:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villamor NJ, de Guzman AB, Matienzo ET. The ebb and flow of Filipino first-time fatherhood transition space: A grounded theory study. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2016;10:51–62. doi: 10.1177/1557988315604019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villani, L., Pastorino, R., Molinari, E., & Boccia, S. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being of students in an Italian university: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Global Health, 17(39). 10.1186/s12992-021-00680-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waseem M, Aziz N, Arif M, Noor A, Mustafa M, Khalid Z. Impact of post-traumatic stress of COVID-19 on the mental well-being of undergraduate medical students in Pakistan. Pakistan Armed Forces Medical Journal. 2020;70(1):S220–S224. [Google Scholar]

- Yazon A, Ang-Manaig K, Tesoro J. Coping mechanism and academic performance among Filipino undergraduate students. KnE Social Sciences. 2018;3(6):30–42. doi: 10.18502/kss.v3i6.2372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, R., Yilmaz, F. G. K., & Keser, H. (2020). Vertical versus shared e-leadership approach in online project-based learning: a comparison of self-regulated learning skills, motivation, and group collaboration processes. Journal of Computing in Higher Education,1–27.

- Yu H, Li M, Li Z, Xiang W, Yuan Y, Liu Y, Li Z, Xiong Z. Coping style, social support, and psychological distress in the general Chinese population in the early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. Bmc Psychiatry. 2020;20:426. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02826-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.