Abstract

Video Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Children growing up in poverty experience worse developmental outcomes than their more economically advantaged peers. Whether Mobility Mentoring, a program focused on building parent executive function to promote economic mobility, results in improved child developmental outcomes is not known.

METHODS

This study population was drawn from children enrolled in Washington State’s public, income-qualified prekindergarten program and their families. We used a quasi-experimental, preintervention-postintervention design with 2 contemporaneous comparison groups: children in the same settings whose families did not receive the intervention and children in settings in which the intervention was not offered. Primary outcomes are improvement in each of the 6 dimensions of the Teaching Strategies GOLD (TSG) measure (social-emotional, physical, cognitive, language, literacy, and mathematics) and meeting or exceeding “widely held expectations” in all of these 6 dimensions.

RESULTS

Within sites that offered the coaching program, children whose parents received the program (n = 2609) showed gains in 2 of 6 TSG dimensions compared with children (n = 440) whose parents did not, and also met or exceeded widely held expectations. TSG outcomes of all children in sites offering the intervention (n = 3049) did not differ from those of children in sites that did not (n = 7216).

CONCLUSIONS

Findings provide sufficient evidence of a positive impact of Mobility Mentoring on child development to merit further study. If substantiated, building parental executive function may improve child outcomes as well as enhance progress toward economic self-sufficiency, and potentially be more engaging than traditional family support programs.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Although, in many studies, researchers have examined parenting training as a strategy to improve child development, there are few studies in which researchers have explored whether coaching that targets parent executive function oriented to improving the family’s economic conditions can also improve children’s developmental outcomes.

What This Study Adds:

Coaching low-income parents to achieve the goals necessary for economic self-sufficiency improved child outcomes in 1 of 2 comparisons. Such programs may be an effective strategy to better engage parents in family support programs and promote child development.

The experience of poverty during early childhood harms a child’s outcomes.1 Educators and policy makers have focused on providing high-quality early care and education as one strategy to disrupt this trajectory.2 Others have created parent training programs to educate parents in techniques that lead to improved child development.3 Still others use home-visiting models, many of which emphasize parenting skills as well as facilitate access to material resources.

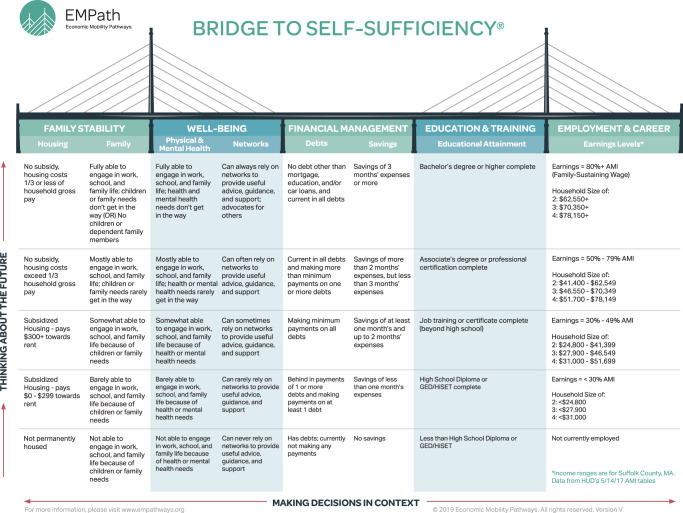

Economic Mobility Pathways (EMPath) developed a coaching method, Mobility Mentoring (MM), to assist people living in poverty move toward economic self-sufficiency.4 This approach is intended to strengthen executive function that may be impeded by early life experiences, by the impact of concurrent scarcity, or both.5 MM entails sharing with the participant a visual metaphor that also serves as a self-assessment tool, the Bridge to Self-Sufficiency. This tool illustrates the dimensions necessary for achieving self-sufficiency and markers of progress for each dimension (Fig 1). Mentors coach program participants across all of these dimensions: family stability, well-being, financial management, education and training, and employment and career. Participants identify and set their own goals, coupled with action plans often linked to specific forms of recognition. Throughout the process, mentors use asset-based strategies, such as the use of unconditional positive regard for participants. Participants in EMPath’s original MM program achieved substantial gains in income, employment, and education over the 3 to 5 years of their participation.6 The developers of MM posited that by strengthening parental executive function, and in particular the mental flexibility to adjust and problem solve in response to different contexts and the self-control to be able to plan and set priorities, the same approach could strengthen family functioning and lead to enhanced child outcomes.7,8

FIGURE 1.

EMPath’s Bridge to Self-Sufficiency. AMI, Area Median Income; GED, general education development; HiSET, High School Equivalency Test; HUD, Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Washington State’s income-qualified prekindergarten program, the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP), seeks to prepare 3- and 4-year-old children from low-income and at-risk families for success. ECEAP pairs strong early childhood development direct services with family support activities designed to help families achieve self-reliance and strong parenting practices that promote children’s early development and school readiness.9 In 2015, ECEAP redesigned its family support program, and from 2015 to 2017 the Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) began small-scale implementation of MM.9 Participating ECEAP contractors provided a minimum of 3 hours of family support contact per year with each child’s parent (or 1 formal visit).

In 2017–2018, DCYF implemented an expansion of MM and identified a comparison population to enable an evaluation.10 We undertook this study to assess the incremental impact of implementing MM on child development. We hypothesized that a program designed to strengthen parental executive function capacity would enhance child development across all domains except physical development.

Methods

Population

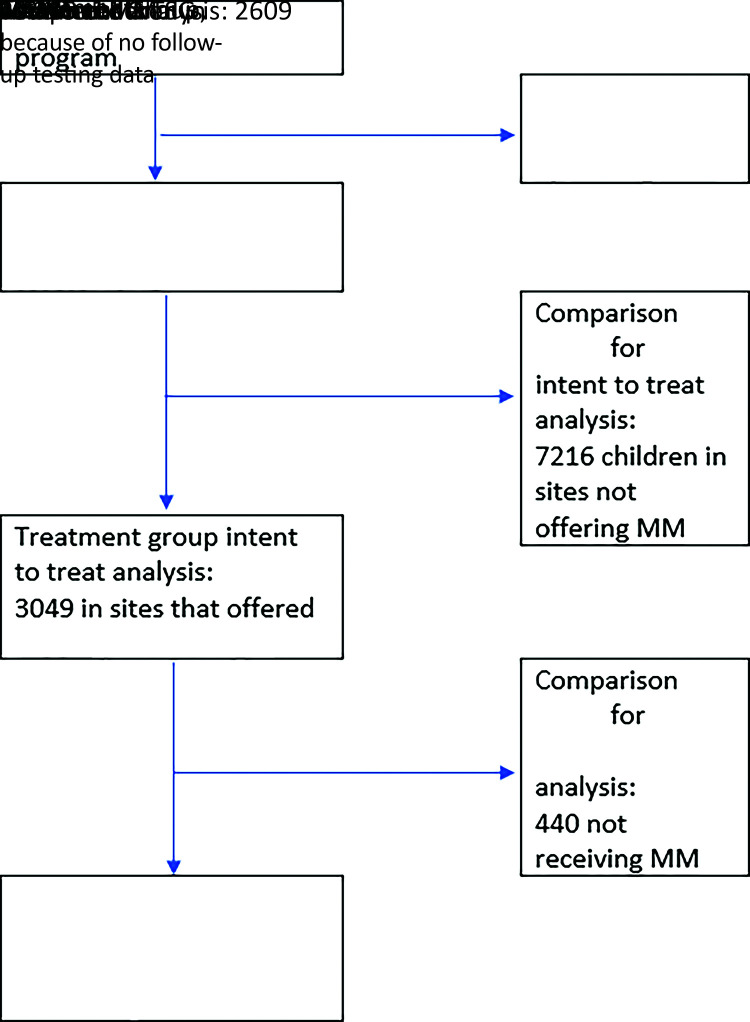

The study population is all children aged 3 to 4 years enrolled in the Washington State ECEAP program during the 2017–2018 academic year (n = 14 399) (Fig 2). Only children who were assessed on all 6 domains of the Teaching Strategies GOLD (TSG) assessment in both fall and spring are included in the analysis (n = 10 265). DCYF offered the opportunity to provide MM to its ECEAP contractors, each of whom provides care in multiple sites, and contractors offered their sites the option of participating. Nineteen of 52 contractors chose to offer MM, and 88 of the 210 sites operated by these contractors chose to participate. Within these 88 sites, families were offered the opportunity to participate in the program. Parents of 2609 children chose to receive MM, whereas parents of 440 children chose not to participate.

FIGURE 2.

Population diagram.

Intervention

The core elements of the MM model are described above.4,11 Washington made modest revisions to EMPath’s Bridge to Self-Sufficiency as well as its Goal Action Plan. In the 2017–2018 year, ECEAP trained family support staff at participating sites to provide MM to parents. The average number of mentoring visits per family during that time was 3.4.

Study Design

The study design is a quasi-experimental, preintervention-postintervention design with 2 comparisons. One comparison is between those children at the intervention sites whose families chose to participate and those children whose parents elected not to participate (within-site analysis). The other comparison is between all children who attended the sites where MM was offered and all children attending sites where MM was not offered, regardless of the site’s contractor (intent-to-treat analysis).

Measures

All ECEAP children were assessed quarterly to track literacy and math skills and cognitive, language, physical, and social-emotional development by using the TSG Birth to Third Grade assessment.12–14 The TSG is a system for assessing children on the basis of teacher observations conducted in the context of everyday classroom experiences. In this study, we use 2 primary outcome measures: a continuous measure of fall to spring scale-score growth for each of the 6 domains of the TSG assessment and a dichotomous measure derived from an age-specific, scale-score readiness cutoff for each domain, known as the “widely held expectation” (WHE). This allows us to construct a single “readiness indicator,” defined as meeting or exceeding WHEs on all 6 domains.

Analyses

In the analysis, we use 2 distinct models. In the within-site analysis, we compare children who received MM with children who did not receive MM within sites offering MM. In this analysis, we use propensity-score matching (PSM) to create balanced comparison groups (see Supplemental Information, Supplemental Figs 3 and 4, and Supplemental Table 10 for further detail on the specific matching procedure used for this analysis).14–16 After establishing balanced comparison groups, the approach uses linear regression to control for child, family, site, classroom, and neighborhood characteristics. We adjust SEs using a variance-covariance estimator (cluster) to account for clustering in classrooms because teacher ratings on the TSG assessment have been shown to exhibit clustering effects within classrooms.17,18

The intent-to-treat analysis contrasts all children in MM sites with all children in non-MM sites. The differences in pretreatment characteristics between groups were too large to use PSM, resulting in an inability to find sufficient balance during the matching procedure. Instead, the analysis employs linear regression analysis, again adjusting SEs to account for clustering within classrooms and controlling for a vector of child, family, site, classroom, and neighborhood characteristics.

The universe of >50 potential confounding variables collected by ECEAP derives from the department’s review of the child development literature. ECEAP collects risk factor information from families to determine program eligibility. We include them in our models if they are related both to likelihood of treatment as well as our outcome measure (TSG spring scores). The variables in both models include child and family demographics (family income, child age, sex, and race and ethnicity) and family and child risk factors reported by families before fall enrollment. These include, but are not limited to, parent education, previous and/or current homelessness, child protective service involvement, parent substance abuse, and child low birth weight. Additional control variables include an indicator of whether the child was enrolled in ECEAP during the previous year, the number of days that elapsed between each child’s fall and spring assessment, as well as baseline assessment results obtained in the fall of the academic year. Program- and/or classroom-level fixed effects include years in operation, years implementing the MM intervention, and classroom model (ie, part, full, or extended day). Neighborhood control variables (relative to the ECEAP site location) include surrounding population density. A full list of variables used is provided in Supplemental Tables 8 and 9.

Human Studies

This research was conducted in an established educational setting (the ECEAP program) and included normal educational practices not likely to adversely impact a student’s opportunity to learn required educational content. It was undertaken by a state agency to evaluate the impact of a public benefits program. These conditions make this program exempt from human studies review, consistent with the Common Rule in place at the time this research was conducted.19

Results

Children receiving MM in the intervention sites differed from children not receiving the intervention in those sites across several characteristics, with most differences consistent with intervention children having a lower risk of experiencing adverse developmental outcomes (Table 1, Supplemental Tables 8 and 9). Children who received the intervention were less likely to speak English at home but also less likely to have had low birth weight, to have previous or current child protective service involvement, or to live in a household with domestic violence or substance use disorder.

TABLE 1.

Selected Characteristics of Children and Families Within Sites Who Did or Did Not Receive MM

| Variable | MM Children (n = 2609) | Non-MM Children (n = 440) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average federal poverty level, % | 74.20 | 80.05 | .06 |

| Average age at fall entry, mo | 49.80 | 49.09 | .03 |

| Proportion White | 0.34 | 0.40 | .01 |

| Proportion multiracial | 0.10 | 0.15 | .003 |

| Proportion Hispanic | 0.48 | 0.39 | .001 |

| Proportion with English as first language | 0.67 | 0.80 | <.001 |

| Proportion with low birth wt | 0.07 | 0.13 | <.001 |

| Proportion with single parent | 0.44 | 0.43 | .90 |

| Proportion with teenaged parent | 0.03 | 0.03 | .60 |

| Proportion with parent sixth grade or less education | 0.11 | 0.11 | .95 |

| Proportion with incarcerated parent | 0.06 | 0.08 | .09 |

| Proportion with domestic violence | 0.13 | 0.19 | .001 |

| Proportion with substance abuse | 0.10 | 0.18 | <.001 |

| Proportion with parent mental illness | 0.18 | 0.26 | <.001 |

| Proportion child protective services (previous or current) | 0.12 | 0.19 | <.001 |

| Proportion with migrant parent | 0.09 | 0.07 | .29 |

| Proportion with isolated residence | 0.15 | 0.12 | .05 |

| Proportion kinship guardian | 0.03 | 0.04 | .56 |

In analyses not accounting for differences in baseline characteristics, children who received the intervention compared with children in treatment sites who did not receive the intervention showed more score growth from fall to spring on each of the 6 domains of the continuous TSG assessment (Tables 2 and 3). Similarly, there was a greater increase among children who received the intervention compared with children in treatment sites who did not receive the intervention in the proportion who met or exceeded the categorical WHEs on all 6 of the domains (ie, the readiness indicator), with a lower proportion meeting all 6 WHEs in the fall and a similar proportion meeting them in the spring (Table 4).

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted TSG Scores for Within-Site Comparison: Children Receiving and Not Receiving MM Within Sites

| Child Non-MM in MM Site (n = 440), Mean (SD) | Child MM in MM Site (n = 2609), Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fall cognitive | 408.17 (77.32) | 393.46 (80.09) |

| Spring cognitive | 496.13 (88.77) | 500.85 (89.45) |

| Fall-spring difference | 87.97 (62.05) | 107.47 (66.38) |

| Fall language | 353.71 (75.07) | 346.80 (80.83) |

| Spring language | 444.91 (91.18) | 446.65 (94.85) |

| Fall-spring difference | 91.20 (60.81) | 99.85 (64.95) |

| Fall literacy | 484.99 (78.32) | 475.89 (87.76) |

| Spring literacy | 576.47 (82.33) | 585.20 (86.66) |

| Fall-spring difference | 91.48 (56.72) | 109.32 (63.57) |

| Fall mathematics | 315.20 (68.81) | 310.22 (70.00) |

| Spring mathematics | 391.26 (70.42) | 400.80 (73.12) |

| Fall-spring difference | 76.05 (46.72) | 90.58 (49.42) |

| Fall social-emotional | 349.66 (53.84) | 342.72 (56.87) |

| Spring social-emotional | 414.20 (62.00) | 421.88 (65.17) |

| Fall-spring difference | 64.53 (44.32) | 79.16 (51.10) |

| Fall physical | 474.77 (85.92) | 467.79 (90.32) |

| Spring physical | 582.28 (95.86) | 595.05 (96.50) |

| Fall-spring difference | 107.51 (76.98) | 127.26 (81.77) |

Only children with 6 domains of the TSG assessment completed in both fall and spring included. SDs are reported in parentheses.

TABLE 3.

Unadjusted TSG Scores for Between-Site Comparison: All Children in MM Sites and All in Children in Nontreatment (Non-MM) Sites

| All Children in Non-MM Sites (n = 7216), Mean (SD) | All Children in MM Sites (n = 3049), Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fall cognitive | 395.57 (80.26) | 395.58 (79.85) |

| Spring cognitive | 496.67 (96.11) | 500.17 (94.17) |

| Fall-spring difference | 101.10 (71.72) | 104.58 (66.12) |

| Fall language | 349.42 (80.74) | 347.80 (80.05) |

| Spring language | 442.42 (99.54) | 446.40 (94.31) |

| Fall-spring difference | 93.00 (71.50) | 98.60 (64.43) |

| Fall literacy | 486.24 (86.07) | 477.20 (86.51) |

| Spring literacy | 588.39 (85.83) | 583.94 (86.09) |

| Fall-spring difference | 102.15 (62.51) | 106.74 (62.94) |

| Fall mathematics | 316.55 (70.03) | 310.94 (69.84) |

| Spring mathematics | 403.48 (74.94) | 399.42 (72.81) |

| Fall-spring difference | 86.93 (54.76) | 88.48 (49.30) |

| Fall social-emotional | 346.41 (59.01) | 343.72 (56.48) |

| Spring social-emotional | 419.55 (71.72) | 420.77 (64.77) |

| Fall-spring difference | 73.15 (57.59) | 77.05 (50.43) |

| Fall physical | 465.11 (95.45) | 468.80 (89.72) |

| Spring physical | 585.77 (108.43) | 593.21 (96.49) |

| Fall-spring difference | 120.66 (88.97) | 124.41 (81.38) |

Only children with 6 domains of the TSG assessment completed in both fall and spring included. SDs are reported in parentheses.

TABLE 4.

Unadjusted WHE TSG Proportion of Children Who Meet or Exceed 6 of 6 Domains for Both Comparisons

| Within Sites | Between Sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children Not Receiving MM (n = 440) | Children Receiving MM (n = 2609) | Children in Non-MM Sites (n = 7216) | Children in MM Sites (n = 3049) | |

| Fall checkpoint | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.18 |

| Spring checkpoint | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

Only children with all 6 domains of the TSG assessment completed in both fall and spring included.

When accounting for the influence of baseline characteristics on treatment assignment through PSM and controlling for additional characteristics, MM was associated with significantly greater fall to spring scale-score growth on the continuous TSG assessment in 2 learning domains (literacy and math) (Table 5). MM was also associated with a >60% significantly greater likelihood of a child meeting or exceeding the categorical WHEs on 6 of 6 domains (odds ratio [OR] 1.62, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05 to 2.51; P = .03). Sensitivity testing supports the robustness of these findings (Supplemental Tables 11 and 12).

TABLE 5.

Effects of Treatment on Spring TSG Assessment Scale Scores, Children Within Treatment Sites Only

| Domain | Coefficient | 95% CIs | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | 11.82 | −0.89 to 24.54 | .07 |

| Language | 4.65 | −6.57 to 15.86 | .42 |

| Literacy | 13.58 | 4.16 to 22.99 | .005 |

| Math | 10.98 | 3.41 to 18.55 | .005 |

| Physical | 4.62 | −8.04 to 17.28 | .47 |

| Social-emotional | 6.06 | −1.75 to 13.87 | .13 |

In contrast to the findings within sites, when comparing all children in the intervention sites with all children in sites that did not offer the intervention, children in the intervention sites evidenced higher levels of characteristics associated with increased risk of adverse developmental outcomes (Table 6, Supplemental Tables 8 and 9). Intervention site children were more likely to have had low birth weight or to have had a parent who was incarcerated, had mental illness, or was a migrant worker.

TABLE 6.

Selected Characteristics of Children and Families Between Sites That Did and Did Not Offer MM

| Variable | Children in MM Sites (n = 3049) | Children in Non-MM Sites (n = 7216) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average federal poverty level, % | 75.04 | 73.84 | .36 |

| Average age at fall entry, mo | 49.70 | 49.75 | .72 |

| Proportion White | 0.35 | 0.32 | .02 |

| Proportion multiracial | 0.11 | 0.11 | .94 |

| Proportion Hispanic | 0.47 | 0.39 | <.001 |

| Proportion with English as first language | 0.69 | 0.67 | .11 |

| Proportion with low birth wt | 0.08 | 0.06 | .003 |

| Proportion with single parent | 0.44 | 0.40 | .002 |

| Proportion with teenaged parent | 0.03 | 0.02 | .007 |

| Proportion with parent sixth grade or less education | 0.11 | 0.09 | <.001 |

| Proportion with incarcerated parent | 0.06 | 0.04 | <.001 |

| Proportion with domestic violence | 0.14 | 0.10 | <.001 |

| Proportion with substance abuse | 0.11 | 0.08 | <.001 |

| Proportion with parent mental illness | 0.20 | 0.15 | <.001 |

| Proportion child protective services (previous or current) | 0.13 | 0.09 | <.001 |

| Proportion with migrant parent | 0.09 | 0.07 | .004 |

| Proportion with isolated residence | 0.15 | 0.08 | <.001 |

| Proportion kinship guardian | 0.03 | 0.03 | .004 |

When comparing all children in the intervention sites with all children in the nonintervention sites, without accounting for differences in baseline characteristics, children demonstrated more growth on the continuous TSG scale scores from fall to spring on 6 of 6 domains for those in the intervention sites (Tables 2 and 3). There was also a greater increase in the proportion of children in the intervention sites who met or exceeded the categorical WHEs on all 6 of the domains, with a lower proportion meeting all 6 WHEs in the fall and a similar proportion meeting them in the spring (Table 4). Yet, when controlling for the baseline differences through linear regression, we found that MM site membership was not associated with greater fall to spring growth in any of the continuous TSG scale scores (Table 7). Intervention status was also not associated with a greater likelihood of a child meeting or exceeding the categorical WHEs on 6 of 6 domains (OR −0.04, 95% CI −0.32 to 0.24; P = .78).

TABLE 7.

Effects of Treatment on Spring TSG Assessment Scale Scores, Between Children in Treatment Sites and Children in Sites Not Offered Treatment

| Domain | Coefficient | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | 2.43 | −8.28 to 13.14 | .66 |

| Language | 2.77 | −6.89 to 12.42 | .57 |

| Literacy | −1.49 | −9.77 to 6.80 | .73 |

| Math | −1.55 | −8.34 to 5.25 | .66 |

| Physical | 2.68 | −9.39 to 14.75 | .66 |

| Social-emotional | 2.13 | −6.15 to 10.41 | .61 |

Discussion

The key question addressed by the evaluation is whether MM results in improved developmental outcomes for children when added to a high-quality preschool program. When comparing children whose parents participated in MM to children whose parents opted not to participate, involvement in MM was associated with significantly greater spring TSG scale scores on the literacy and math domains, controlling for baseline TSG scores and demographic, risk, and programmatic variables. Children in these sites whose parents received MM were also 60% more likely to meet or exceed WHEs in all 6 learning domains. However, when we compared developmental outcomes for all children in sites that offered MM to children in sites that did not offer it, the model revealed no significant effects across TSG learning domains or meeting or exceeding the WHE.

Each comparison has the potential to answer different questions. A direct comparison between those who receive an intervention and those who do not is more likely to detect an effect because the intervention group is not diluted by those not receiving the intervention. Although this is a real-world implementation with numerous potential biases, this comparison nonetheless informs the question of the potential of an intervention to have an impact. The comparison between sites offering the intervention and sites not offering the intervention is closer to an assessment of what would typically happen when a program was implemented through broad public policy. Thus, it has the potential to inform policy decisions about whether to launch a program or not and what additional steps might need to be taken to strengthen implementation.

Because of the quasi-experimental, real-world nature of this evaluation, each of these comparisons contains threats to validity. For the comparison within the same site, teachers may have encouraged families to participate whom they thought would benefit. More motivated parents may have chosen to participate; refusal may be an indicator of unmeasured characteristics associated with adverse child outcomes. For the between-site comparison, the impact on the children whose families received the services may have been diluted by the lack of impact on those families not receiving the intervention in those sites. Sites and contractors may have been excluded or chose not to participate because they were already doing well. Implementation challenges may have also diminished impact. Formal measures of fidelity to the model were not used. With a longer time with the model with ongoing support, coaches might achieve greater impact. EMPath’s experience is that at least 6 months experience with close supervision is necessary to become highly skilled. In both comparisons, teachers who performed the TSG assessments were aware of the treatment status of the child.

Another potential source of bias is that 4134 children were excluded from analysis because they did not have the fall or spring TSG assessment checkpoint completed for one or more domains. Missing the fall assessment was the most common reason, usually because of late program enrollment. The proportion with missing data was equally distributed in the between-site comparison (38% and 39% missing in intervention and comparison sites, respectively). However, in the within-site comparison, only 16% of the children whose family received the intervention had missing data, whereas 62% of children in these sites who did not receive the intervention had missing TSG data. Children with missing data enrolled later in ECEAP and had higher levels of risks (eg, health concerns and housing instability). By not capturing the outcomes of the missing children, the impact of the intervention is likely underestimated in the analysis.

Despite the contrasting findings of the 2 analyses, the positive findings within the sites that offered MM suggest that a program focused on developing specific executive function capabilities among parents may improve child development. This explanation is supported by data from a customer satisfaction survey administered by ECEAP over the same time period.10 Among the 3719 respondents to the survey, 84% of the 1910 respondents participating in MM strongly agreed or agreed with the statement, “After ECEAP support this year, it is easier for me to slow down and think my problems through to a solution,” whereas only 57% of non-MM respondents agreed or strongly agreed.

Research on interventions to improve adult executive function also supports the possibility that MM improves child development through this pathway. The Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University noted that individual-level interventions can promote “intentional self-regulation” through a variety of strategies, many of which are incorporated in MM.20 Given previous research revealing an association between parental executive function and child executive function, particularly in low-income families, it is plausible that MM’s effect on child developmental outcomes occurs through its effect on parental executive function.21 This study does not exclude the possibility of other mechanisms, such as enabling parents to better connect to community resources or developing greater self-confidence or more specific goal-setting capacity.

With their newfound increase capacity to plan and set goals, parents in the intervention group may have focused on those child skills that are most widely known and discussed: reading and math. In qualitative research in subsequent studies, researchers should examine parent and parenting behaviors to elucidate such mechanisms.

Although the contrasting results from the 2 comparisons limit the strength of the conclusions, the possibility of achieving positive child outcomes while also supporting a family’s progress toward self-sufficiency justifies further evaluation. A first step might be continuing to evaluate the developmental outcomes of these children. Studies in which researchers use outcome evaluations blinded to intervention status and incorporate multiple measures of development would address some limitations, as would the use of a design such as regression discontinuity, if all families just below an income threshold participated and those just above did not. A more definitive assessment would be an individual randomized controlled trial. If such a trial produced promising results, a cluster-level trial in which matched sites are randomly assigned to MM or a control condition would inform policy decisions about whether to implement this approach more broadly. All such studies should have a broad enough sample to assess the performance of MM across different levels of risk of adverse developmental outcomes. Although >200 human service organizations and several state and local governments have implemented MM-informed programs, widespread adoption of such approaches by government increasingly requires such rigorous evidence.22

Deep engagement of families in early care and education programs has historically been difficult. Families may feel they already have sufficient knowledge about parenting or that the center should provide such support directly to the child while the parents pursue their own education or employment. MM, by focusing on helping the parents themselves better address their challenges and needs across many dimensions of their lives (education, employment, finances, family function, and housing, as well as child health and development) may promote greater engagement in family support programs. Moreover, in supporting the fundamental capacity of planning, problem solving in context, prioritizing, and setting and achieving goals, MM may enable parents to better execute the positive parenting behaviors they desire and provide the structure that children need to thrive.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- DCYF

Department of Children, Youth, and Families

- ECEAP

Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program

- EMPath

Economic Mobility Pathways

- MM

Mobility Mentoring

- OR

odds ratio

- PSM

propensity-score matching

- TSG

Teaching Strategies GOLD

- WHE

widely held expectation

Footnotes

Drs Homer and Winning conceptualized the analytic approach, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Cummings assembled the data, conceptualized and conducted the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: No external funding.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2021-053479.

References

- 1. Le Menestrel S, Duncan G, eds; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty in Half in 10 Years . A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heckman JJ, Karapakula G. Intergenerational and intragenerational externalities of the Perry Preschool Project. 2019. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w25889. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 3. Perrin EC, Leslie LK, Boat T. Parenting as primary prevention. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):637–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Babcock E. Using brain science to design new pathways out of poverty. 2014. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/empath-website/pdf/Research- UsingBrainScienceDesignPathways Poverty-0114.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 5. Mullainathan S, Shafir E. Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much. New York, NY: Picador; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prottas J, Gaiser MD. Evaluation of EMPath’s Career Family Opportunities Program. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Babcock E, de Luzuriaga NR. Families disrupting the cycle of poverty: coaching with an intergenerational lens. 2019. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/empath-website/pdf/Intergen_Publication_July_19_2019.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 8. Harvard University Center on Developing Child . Executive function and self- regulation. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/executive-function/ Accessed May 19, 2021

- 9. Washington State Department of Early Learning . Year one report: ECEAP family support pilot: June 2015–June 2016. 2016. Available at: https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/eceap/ ECEAP_Family_Support_Pilot_ Report_Final.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 10. Washington State Department of Children, Youth, and Families . Mobility mentoring outcomes report 2017–2018. 2018. Available at: https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/Mobility_ Mentoring_Outcomes_2017-2018.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 11. Babcock E. Harnessing the power of high expectations: using brain science to coach for breakthrough outcomes. 2018. Available at: https://www.empathways.org/research-policy/publications/2018-high-expectations. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 12. Teaching Strategies, LLC . Teaching Strategies GOLD Assessment System: concurrent validity. 2013. Available at: https://teachingstrategies.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/GOLD-Concurrent-Validity-2013.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 13. Teaching Strategies, LLC . GOLD. Available at: https://teachingstrategies.com/solutions/assess/gold/. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 14. Abadie A, Spiess J. Robust post-matching inference [published online ahead of print January 14, 2021]. Journal of American Statistical Association. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459. 2020.1840383 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33(6):1057–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lambert RG, Kim D, Burts DC. The measurement properties of the Teaching Strategies GOLD assessment system. Early Child Res Q. 2015;33:49–63 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogers WH. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1993;13:19–23 [Google Scholar]

- 19. 45 CFR §46.101 (b) (1991)

- 20. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University . Building core capabilities for life: The science behind the skills adults need to succeed in parenting and in the workplace. 2016. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/building-core-capabilities-for-life/. Accessed June 8, 2020

- 21. Kao K, Nayak S, Doan SN, Tarullo AR. Relations between parent EF and child EF: the role of socioeconomic status and parenting on executive functioning in early childhood. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 2018;42(2):122–137 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haskins R, Margolis G. Show Me the Evidence. Washington, DC: Brookings; 2015 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.