Abstract

Knowing how people prepare for disasters is essential to developing resiliency strategies. This study examined recalled concerns, evacuation experiences, and the future preparedness plans of a vulnerable population in New Jersey, United States, following Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Understanding the responses of minority communities is key to protecting them during forthcoming disasters. Overall, 35 per cent of respondents were not going to prepare for an event. Intended future preparedness actions were unrelated to respondents’ ratings of personal impact. More Blacks and Hispanics planned on preparing than Whites (68 versus 55 per cent), and more Hispanics planned on evacuating than did others who were interviewed. A higher percentage of respondents who had trouble getting to health centres were going to prepare than others. Respondents’ concerns were connected to safety and survival, protecting family and friends, and having enough food and medicine, whereas future actions included evacuating earlier and buying sufficient supplies to shelter in place.

Keywords: disaster preparedness, environmental justice, evacuation, Hurricane Sandy, personal disaster impact

Introduction

Being prepared for major storms and extensive flooding is increasingly important in coastal communities owing to predictions of greater frequency and the severity of such events, leading to more flooding, evacuations, and home losses (Lane et al., 2013; NPCC2, 2013). In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, public officials realised that a large proportion of United States citizens live without the economic and social resources to protect themselves and their families during disasters (Eisenman et al., 2007). More than one-half of the US population lives along the coasts (Crosset et al., 2013), and hence is geographically vulnerable. The Atlantic coast from Boston to Washington, DC, is particularly urbanised, and most of the natural salt marsh, beach, and sand dune habitat that would buffer coastal communities from storm surge is no longer intact (Nordstrom and Mitteager, 2001; Psuty and O’Fiara, 2002; Pries, Miller, and Branch, 2008; Plant et al., 2010; Burger, 2015). The extent of erosion of beaches and dunes, and damage to structures and infrastructure, is dependent on the height of storm surges, the direction of landfall attack, and the volume, length, and width of the dunes (Barone, McKenna, and Farrell, 2014; Bukvic and Owen, 2017).

The damage caused by hurricanes and superstorms can be acute because of the severity of the storm (hazard) and the increase in the number of community members exposed to coastal flooding (USGS, 2010; Genovese and Przyluski, 2013). Social vulnerability is also important. Serious health conditions, emotional distress, and grief follow such disasters; consequently, post-disaster needs assessments are essential for recovery and understanding post-event mental health (Kessler et al., 2008; North, Oliver, and Pandya, 2012; Swerdel et al., 2016). It is important to understand the concerns, factors, and perceptions that lead people to prepare, plan, or evacuate their homes (Abramson et al., 2015), or even to retreat from their homes once they have been destroyed by disasters (Alexander, Ryan, and Measham, 2012). Preparedness is especially critical for those with health problems or who are otherwise disabled (Murakaml et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015). Preparedness includes planning for future events, including the intent to engage in concrete actions, such as obtaining food, generators, medicines, water, and other supplies, as well as evacuation plans and knowing where to shelter. Many minorities, particularly Latinos, feel that they are unprepared for any disaster, such as a hurricane (Burke, Bethel, and Britt, 2012). One of the variables that may affect future preparedness is experience of hurricanes, and the potential concerns and worries that manifested themselves during the previous event (Trumbo et al., 2011).

This survey-based study examined the recalled concerns and evacuation experiences of a vulnerable population, along with the respondents’ current views on, and their plans for, future preparedness. It was particularly interested in whether their future preparedness plans were related to their evacuation behaviour during Hurricane Sandy (also called Superstorm Sandy) in 2012, or to their personal rating of its impacts. The investigation also examined age, ethnic, and gender differences. An additional objective was to determine whether individual preparedness declined with time after Sandy. During 2015, 599 patients were interviewed using federally qualified health centres (hereafter health centres) in New Jersey. The health centres offer a wide range of services, from paediatric and dental care to geriatrics, and serve mainly the uninsured and underinsured. Patients/clients thus represent an economically challenged, minority community (NJPCA, 2017). New Jersey had 20 centres operating more than 80 clinical facilities in 2015, which are distributed around the state, usually in urban areas.

Hurricane Sandy hit the eastern US in late October 2012, affecting an estimated 60 million people in 24 states (Neria and Shultz, 2012). Sandy had a diameter twice that of Katrina (Abramson et al., 2015), and 162 people lost their lives in the storm (Freedman, 2013a; Schwartz et al., 2015). This study avoids using the term ‘superstorm’ as it connotes uniqueness, while its findings should be generally applicable to major storms and disasters. Coastal communities in New Jersey and New York were hit especially hard by Sandy because it arrived nearly perpendicular to the coastline (Hall and Sobel, 2013), and then stalled over the region, producing record storm surges from the Atlantic, as well as flooding along bays and rivers. More than 345,000 housing units were destroyed in New Jersey, resulting in excess of USD 70 billion of damage. In addition, there was USD 3 billion of damage to transit roads and bridges in New Jersey, and many people were displaced from their homes owing to storm surge (Borough of Mantoloking, 2012), as well as flooding and loss of power (Barnegat Bay Partnership, 2012; Freedman, 2013a).

The week following Sandy was unseasonably cold, with below-freezing temperatures across much of the impacted area. Coupled with prolonged power outages, this caused many people to evacuate belatedly. Three years later, many people were still displaced, and others had abandoned their homes and moved elsewhere.

Methods

The overall study protocol was to interview patients at health centres in New Jersey about their experiences of Hurricane Sandy. The centres chosen for interviews were (from north to south): Horizon Health Center in Jersey City, Hudson County; Neighborhood Health Center in Elizabeth, Union County; Neighborhood Health Center in Plainfield, Union County; Eric B. Chandler Health Center in New Brunswick, Middlesex County; Monmouth Family Health Center in Long Branch, Monmouth County; CHEMED (Center for Health Education, Medicine, and Dentistry) in Lakewood, Ocean County; and Ocean Health Initiatives in Toms River, Ocean County (see Figure 1). Six of the seven sites where patients were interviewed were in the five most storm-damaged counties in New Jersey (Halpin, 2013).

Figure 1.

Map showing the locations of the seven health centres where interviews were conducted

Source: authors.

The interview survey included questions about the overall personal impact assessment of the respondents, as well as their specific concerns, whether and when they evacuated, and their future preparedness plans. No personal identifiers were recorded. The protocol and questionnaires were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Rutgers University (IRB, Protocol E14–319, Notice of Exemption), by the IRB at the New Jersey Department of Health, and by the Board of Directors of the New Jersey Primary Care Association, which represents the federally qualified health centres in the state. With the permission of the medical directors, as well as the patients, 599 people at seven facilities were interviewed. Many respondents lived in communities with mandatory evacuation; many were flooded out during the storm or evacuated after the hurricane passed.

Interviews were conducted by the authors and other trained interviewers, half of whom spoke Spanish as a first language, in 2015, between 27 and 36 months after Sandy. The questionnaire used for the interviews was based in part on previous questionnaires (Burger and Gochfeld, 2014a, 2014b). It was further developed for this target population, tested in a pilot study, modified accordingly prior to implementation, and translated into Spanish. The questionnaire included information on the respondents’ demographic circumstances, concerns during and immediately following Sandy, personal impacts of the hurricane on their home and family (scale: ‘0’ (none) to ‘5’ (very severe), access to the centre and centre use, disruption of their medical services during Sandy (all within two to three weeks of the event), whether they evacuated, and what they planned to do in the event of a future severe storm (open-ended). Ethnicity/racial status was by self-identification, using the following United States Census Bureau categories: ‘White’ (White non-Hispanic); ‘Black’ (Black or African-American, non-Hispanic); ‘Hispanic’ (Hispanic or Latino); or Asian (Burger et al., 2017). The focus of this paper is on future preparedness plans in relation to the experiences (evacuation, impacts) and concerns of the interviewees during and immediately after Sandy.

When patients arrived at the health centres for appointments, they went either to a general waiting room or to a department-dedicated waiting room. Interviewers approached subjects in the order in which they entered a waiting room. Then they identified themselves as being from Rutgers University, sought permission to interview them, and informed them that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, that no individual identifiers would be recorded, and that the interview could be stopped at any time. Information on contacting the IRB at Rutgers University was provided.

Once subjects consented, interviewers asked the questions in a secluded place. Refusals were typically owing to a lack of time, or the need to care for children or elderly charges. Approximately 10 per cent of interviews were interrupted when patients were called for their appointments. The future preparedness question was near the end of the interview. Hence, the sample size for different questions varied. The interview normally required about 15–20 minutes, although many were longer when patients wanted to talk about their experience. Once an interview was completed, the next patient to enter was approached for an interview.

Respondents could report more than one concern that they had during and immediately after Sandy, and they could report more than one preparedness action (such as buy batteries and food, evacuate, plan for family members or to check on neighbours, or protect possessions). Analyses included calculating frequencies and percentages, means and standard deviations, and Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi square contingency tests (SAS, 2005).

Results

The respondents in this study were Hispanic (56 per cent), non-Hispanic White (25 per cent), non-Hispanic Black (18 per cent), and other (1 per cent). Fewer Hispanics were born in the US (10 per cent) as compared to Blacks (83 per cent) or Whites (80 per cent). Only 15 per cent of Hispanics identified English as their primary language, as compared to more than 90 per cent for all others. Overall, 17 per cent evacuated, some in the wake of the storm, and there were no ethnic differences in evacuation rates. Respondents said that they went to shelters, or to the homes of family members or friends, and were without power for an average of 8–11 days. On a scale of ‘1’ to ‘5’ (most severe), people rated their own personal impact as an average of ‘3’. Only 4 per cent of Whites said that they needed healthcare during Sandy, whereas it was 12 per cent for Hispanics and 14 per cent for Blacks (for more details, see Burger and Gochfeld, 2017; Burger, Gochfeld, and Lacy, 2019).

Respondents’ concerns about Sandy

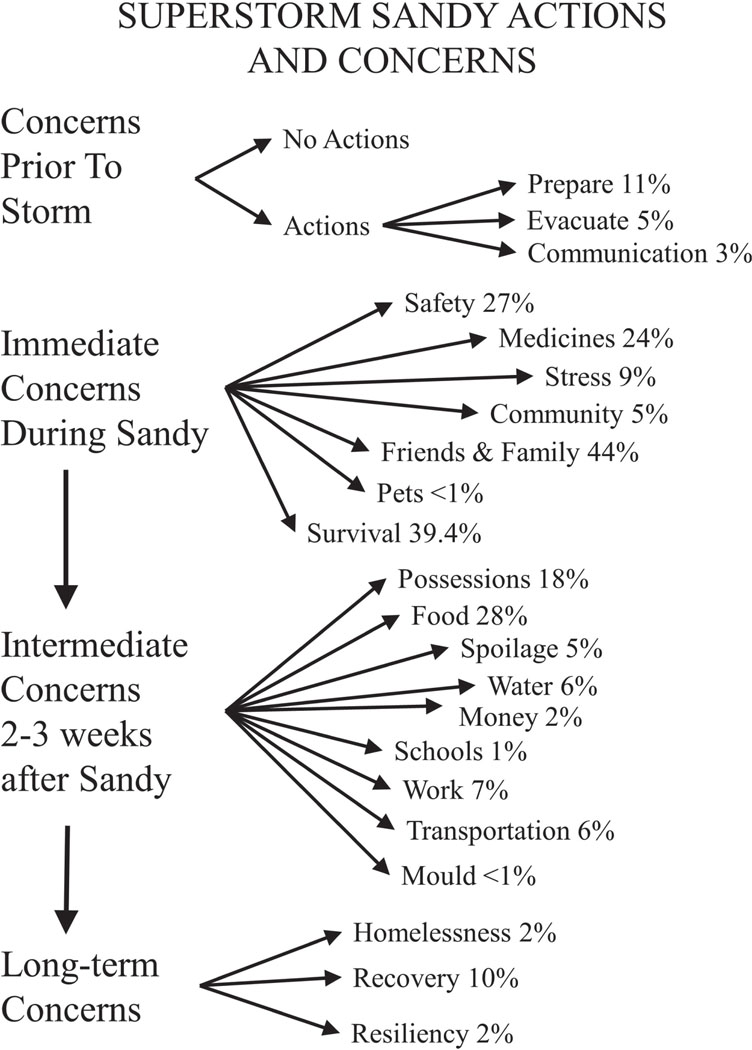

Respondents were asked about their concerns during Sandy, which had occurred some three years earlier. Their concerns fell into four categories: worries during Sandy about health and safety; immediate actions; intermediate concerns about possessions, supplies, school, or work, and transportation; and long-term worries pertaining to homelessness, recovery, and resilience (see Figure 2). Immediate actions related to preparing their homes, buying supplies, communicating with family and friends, and evacuating to family, friends, or shelters before the storm. During the hurricane, respondents worried about health and safety, including (in this order) friends and family, survival, medicines, possessions, stress, community, and pets (see Figure 2). Many had to evacuate during Sandy owing to flooding or afterwards because of a lack of electricity, heat, and food. Following the hurricane, respondents worried about survival and possessions, supplies (water, food and spoilage, money), school and work, and transportation. Few respondents reported worrying about being homeless (2 per cent), recovery (fixing homes; 10 per cent), and resiliency (raising homes; 2 per cent) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concerns voiced by respondents before, during, and immediately after Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey

Notes: respondents were interviewed about three years after the hurricane, but were asked what their concerns were during and following Sandy. ‘Immediate’ refers to the days during and up to a week after Sandy, whereas ‘intermediate’ refers to weeks and ‘long term’ refers to months or even years.

Source: authors.

The concerns expressed by the respondents varied by their personal impact rating (Table 1, overall P<0.001). Personal impacts were grouped into ‘low’ (rating: ‘0’ or ‘1’), ‘medium’ (rating: ‘2’ or ‘3’), and ‘high’ (rating: ‘4’ or ‘5’). Overall, the biggest concerns were for family, survival, safety, food, and medicines. Those who rated their personal impact as ‘low’ were significantly more likely to report their concerns as ‘none’ for both family and medical matters, as compared to respondents’ who rated their impact as ‘high’. Food shortage or safety was mentioned less often by ‘low’ impact respondents. There was no similar relationship between personal impact and the number of respondents citing a lack of preparation for Sandy as a concern.

Table 1.

Main concerns during Hurricane Sandy of subject population by personal impact rating (low=0–1, medium=2–3, high=4–5)

| Concern mentioneda | All (%) n=559b | Low (%) n=66 | Medium (%) n=252 | High (%) n=241 | Chi-square (individual P<) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10.5 | 22.7 | 8.7 | 7.1 | 15.0 (0.0005)* |

| Family | 44.0 | 31.8 | 51.6 | 40.2 | 11.1 (0.004)* |

| Survival | 39.4 | 36.4 | 42.9 | 39.4 | NS |

| Foodc | 26.6 | 18.2 | 28.6 | 31.5 | NS |

| Safety | 28.8 | 24.2 | 32.1 | 22.0 | 6.7 (0.03) |

| Medical/medications | 23.5 | 7.6 | 19.8 | 32.8 | 19.6 (<0.0001)* |

| Possessions | 18.1 | 13.6 | 16.3 | 21.2 | NS |

| Prepare | 11.1 | 12.1 | 11.5 | 10.0 | NS |

| Recovery | 9.7 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 11.6 | NS |

| Stress | 8.5 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 5.0 (0.08) |

| Work | 7.4 | 3.0 | 8.3 | 7.5 | NS |

| Evacuate | 4.7 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 8.8 (0.01) |

| Transportation | 6.0 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 6.6 | nt |

| Water | 5.7 | 6.1 | 5.2 | 6.6 | nt |

| Community | 4.5 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 4.6 | nt |

| Communication | 2.8 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.1 | nt |

| Homeless | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 4.6 | nt |

| Security | 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 2.1 | nt |

| Ecologicald | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | nt |

| Money | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.5 | nt |

| Schools | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.8 | nt |

| Mould | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | nt |

| Pets | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | nt |

Notes:

Overall Chi square is 86 (P<0.001); Bonferroni corrected level of significance is P=0.004.

NS=not significant as an individual test.

nt=not tested due to sparse responses.

=people could report more than one concern.

=not all persons answered this question.

=food availability or spoilage.

=including mention of dunes, marshes.

=significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Source: authors.

Halpin (2013) produced a rating of low to very high impact by county and municipality, based on business, home, infrastructure, and other damage caused by Sandy. Two centres were designated as ‘very high’ impact, three as ‘high’ impact, and two as ‘medium’ impact. There were overall differences as a function of the study’s impact rating (Table 2, P<0.0001), but they were not as clear. Respondents attending health centres in ‘very high’ impact counties all voiced some concerns, emphasising evacuation, stress, recovery, pets, homelessness, money, and jobs. Fewer among the group, though, expressed concern about family or possessions than among those attending health centres in ‘medium’ impact counties. That is, there were significant differences, but respondents at centres in the medium impact counties (the lowest rating for any of the counties where the federally qualified health centres were located) did not necessarily have the lowest number of concerns.

Table 2.

Main concerns during Hurricane Sandy of subject population by health centre’s county impact rating, based on Halpin (2013)

| Concern mentioneda | All (%) n=586b | Medium (%) n=257 | High (%) n=158 | Very high (%) n=171 | Chi-square (individual P<) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10.5 | 6.2 | 17.1 | 10.5 | 12.4 (0.002)* |

| Family | 44.0 | 46.3 | 44.3 | 38.6 | NS |

| Survival | 40.4 | 44.7 | 41.8 | 31.0 | 8.4 (0.02) |

| Foodc | 29.0 | 28.0 | 27.2 | 31.0 | NS |

| Safety | 26.6 | 28.0 | 16.5 | 32.7 | 12.0 (0.003)* |

| Medical/medications | 23.5 | 27.2 | 22.2 | 18.1 | NS |

| Possessions | 18.1 | 16.0 | 24.7 | 14.6 | 6.9 (0.03) |

| Prepare | 11.6 | 16.7 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 12.6 (0.002)* |

| Recovery | 9.8 | 14.0 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 10.9(0.004)* |

| Stress | 8.5 | 8.6 | 6.3 | 9.9 | NS |

| Work | 7.4 | 7.8 | 5.7 | 8.2 | NS |

| Evacuate | 3.5 | 3.5 | 8.2 | 2.3 | 7.7 (0.02) |

| Transportation | 6.0 | 8.2 | 3.2 | 5.3 | nt |

| Water | 5.7 | 7.4 | 2.5 | 5.8 | nt |

| Community | 4.7 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 4.1 | nt |

| Communication | 2.8 | 3.1 | 1.3 | 3.5 | nt |

| Homeless | 2.4 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 1.2 | nt |

| Security | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 2.3 | nt |

| Ecologicald | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 5.8 | 20.9 (<0.0001) |

| Money | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 4.1 | nt |

| Schools | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | nt |

| Mould | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | nt |

| Pets | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | nt |

Notes:

Bonferroni corrected level of significance is P=0.004.

NS=not significant as an individual test.

nt=not tested due to sparse responses.

=people could report more than one concern.

=not all persons answered this question.

=food availability or spoilage.

=including mention of dunes, marshes.

=significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Source: authors.

Preparedness actions

The survey also examined preparedness plans by personal impact rating (see Table 3). There were no differences in the percentage of people planning to do ‘nothing’ or any of the specific preparations mentioned. Overall, very few respondents said that they would evacuate earlier, particularly among those with a low personal impact rating. Approximately 25–30 per cent stated that they would make preparations, among which buying supplies was commonly noted, regardless of impact rating.

Table 3.

Preparation plans respondents mentioned for next hurricane by their personal impact rating (low=0–1, medium=2–3, high=4–5)

| Preparation mentioned | All (%) n=559c | Low (%) n=66 | Medium (%) n=252 | High (%) n=241 | Chi-square (individual P<) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do nothing | 34.2 | 42.0 | 35.4 | 31.3 | NS |

| Be prepared (general) | 26.9 | 30.0 | 29.3 | 24.1 | NS |

| Buy supplies | 26.7 | 22.0 | 29.3 | 25.6 | NS |

| Evacuate | 12.0 | 4.0 | 12.8 | 13.3 | NS |

| Seek information | 7.1 | 4.0 | 7.3 | 7.7 | NS |

| Buy generator | 5.6 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.6 | NS |

| Prepare emergency kit | 2.7 | 6.0 | 1.2 | 3.1 | NS |

| Encourage government actions | 5.4 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 6.7 | nt |

| Future plansa | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 5.1 | nt |

| Protect family | 3.9 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 5.1 | nt |

| Protect community | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 3.6 | nt |

| Protect possessions | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.6 | nt |

| Faith/pray | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 3.1 | nt |

| Protect environmentb | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | nt |

Notes:

These are separate possible responses; Bonferroni not applied. However, none of the comparison are significant different even at the 0.10 level.

NS=not statistically significant at P=0.05.

nt=not tested due to sparse responses.

=future plans not specified.

=mentioned some environmental feature (such as dunes).

=not all respondents reached this question in the interview.

Source: authors.

Our understanding of preparedness of individuals is that they have limited choices. Respondents could advocate for government actions (7 per cent) before a disastrous event, or they could emphasise personal actions. They could do nothing or pray, they could evacuate (before, during, or after), or they could prepare in some other ways (see Figure 3). Respondents mentioned doing ‘nothing’ (35 per cent), praying (2 per cent), evacuating (12 per cent), and other preparations (54 per cent). An additional 26 per cent said that they would prepare, but did not elaborate or seem to have specific plans. Preparation (see Figure 3) included seeking more information, buying supplies, hardening their homes (such as installing shutters or raising their homes), and protecting family, community, and possessions. Individuals were planning to buy batteries, blankets, candles, emergency kits, food, gas, generators, lanterns, and water.

Figure 3.

Preparedness plans of respondents interviewed two to three years after Sandy

Note: respondents were asked ‘what they would do next time they learned that a hurricane landfall was imminent?’.

Source: authors.

Few people mentioned designating a safe place to meet family, evacuation kits, securing medical documents or medications, or having an escape plan. Even fewer reported checking on seniors or neighbours (including neighbours who were undocumented). Only seven per cent of the respondents noted actions that clearly were the responsibility of government (see Figure 3). These fell into four types: offer more information and training; take care of people; provide more shelters and transportation; and protect the environment. Some of these are actions that can be taken in the days or weeks immediately before a hurricane (activate information centres, designate shelters), whereas some are to be taken during and immediately after (check on seniors, other people), or in the longer term (education in school, conserve the planet).

Evacuation

Respondents could evacuate, and return when it becomes safe to reoccupy or rebuild their homes. Some did not return because their houses were completely destroyed or because of the mental stress caused by storm damage. Many renters were able to return relatively quickly, once the light and heat were on. More than 60 per cent of Hispanics rented apartments as compared to less than 48 per cent of both Blacks and Whites (X2=14.8, P<0.0006). The respondents interviewed in this study mainly expected or hoped to return to their homes, even the few who were still displaced three years later. Only four respondents said that they would move if there was another severe storm. Of those who evacuated, 8 per cent of Blacks, 10 per cent of Hispanics, and 25 per cent of Whites were still out of their homes at the time of the survey—2.5 per cent of the 599 respondents were still not able to return home by the end of 2015. Since they were still using the health centres, they had remained in the area. People who had moved away obviously could not be interviewed.

Association between demographics and future preparedness

Age, gender, and racial/ethnic identity are often associated with perceptions, concerns, environmental attitudes, and health effects, and this was apparent among the health centre respondents as well (Burger and Gochfeld, 2017; Burger, Gochfeld, and Lacy, 2019). Among people who did not plan to prepare, more were born in the US than elsewhere (47 versus 36 per cent), or had been in the country for longer (18 versus 15 years; see Table 4). Comparing groups who will versus who will not prepare, there were no significant differences in personal impact rating, health centre use, mode of transportation, and most medical issues. However, significantly more people who intended to prepare in the future experienced trouble getting to the health centres before or immediately after Sandy. In the days prior to the hurricane, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie had issued multiple public service orders to evacuate. Surprisingly, there was no statistical relationship between preparedness intentions and prior evacuation experience (memory of being told to evacuate, actual evacuation, duration of evacuation).

Table 4.

Demographics and other characteristics for subject population interviewed three years after Sandy at health centres in New Jersey by plans to take action for a future storm

| Characteristic | Prepare n=274 | Do nothing n=142 | Chi-square (individual P<) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Percentage female | 70.8% | 69.7% | NS |

| Mean age | 40.8 ± 0.7 | 41.6 ± 1.3 | NS |

| Mean years of education | 12.3 ± 0.3 | 13.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 (0.07) |

| US born | 36.6% | 47.1% | 4.3 (0.04) |

| Years in the USa | 15.3 ± 0.8 | 18.1 ± 1.4 | 5.2 (0.02) |

| Sandy effects | |||

| Percentage told to evacuate | 17.2% | 18.4% | NS |

| Percentage evacuated | 21.2% | 19.9% | NS |

| Days evacuatedb | 37.1 ± 11.5 | 31.4 ± 10.8 | NS |

| Percentage still out of the housec | 11.8% | 19.4% | NS |

| Days with no powerd | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 12.2 ± 2.1 | NS |

| Personal impact ratinge | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | NS |

| Centre use | |||

| How long going to centre (years)? | 6.4 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Percentage used this centre before Sandy? | 51.1% | 56.0% | NS |

| Centre visits/year (95th percentile) | 6.6 ± 0.5 (22) | 6.5 ± 0.6 (20) | NS |

| How do you get to the centre? | |||

| Car | 53.4% | 63.7% | NS |

| Walk | 25.0% | 19.3% | |

| Taxi | 9.7% | 9.6 | |

| Bus | 11.9% | 12.6% | |

| Medical transport/other | 1.5% | 1.5% | |

| Medical issues | |||

| Percentage who had trouble getting to the centref | 9.2% | 4.4% | 3.0 (0.08) |

| Percentage who needed the centre during Sandy?f | 12.8% | 7.9% | NS |

| Percentage who experienced any interruption in medical services or medication owing to Sandyf | 8.5% | 9.2% | NS |

| Percentage with any ‘medical need’ during or immediately after Sandyg | 21.5% | 19.0% | NS |

Notes:

Comparisons made using Kruskal-Wallis Chi-square or Chi-square contingency tests.

=if not born in the US;

=if you evacuated, when were you able to go home?;

=if the person had to evacuate and had not returned home at the time of the survey in 2015;

=includes zero days for people without power outages;

=on a scale of ‘0’ (no impact) to ‘5’ (severely);

=self-identified;

=‘medical need’ is a composite score by the investigators.

Source: authors.

There were ethnic differences in whether people were going to do nothing, or take other actions. Significantly more Whites were going to do nothing (45 per cent) than Blacks (33 per cent) and Hispanics (31 per cent) (X2=6.2, P>0.05). When all of the preparedness categories are considered, there are also ethnic differences: more Hispanics were going to evacuate and more Blacks and Hispanics were going to obtain supplies than were Whites (see Table 5). There were no gender differences in whether respondents intended to do nothing, or prepare in some way (X2=0.05, P=0.81), and there were no differences as a function of personal impact rating or Halpin’s (2013) community rating (X2 tests).

Table 5.

Ethnic/racial differences in preparations for a future event—respondents answered the question: ‘What will you do differently next time you hear a hurricane is coming?’*

| Total (%) | Hispanic (%) | Black (%) | White (%) | Chi-square (individual P<) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 416 | 240 | 73 | 97 | |

| Percentage female | 70.3 | 72.1 | 78.1 | 60.2 | |

| Do nothing | 34.4 | 30.8 | 32.9 | 45.4 | 6.2 (0.05) |

| Be prepared (general) | 26.7 | 30.0 | 27.4 | 19.6 | NS |

| Buy supplies | 26.9 | 26.3 | 30.1 | 25.8 | NS |

| Evacuate | 12.0 | 14.2 | 9.6 | 9.3 | NS |

| Seek information | 7.0 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 1.0 | 7.2 (0.03) |

| Buy generator | 5.5 | 2.1 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 13.5 (0.001) |

| Prepare emergency kit | 2.6 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 10.3 | 6.2 (0.04) |

| Encourage government actions | 5.3 | 6.7 | 2.7 | 3.1 | nt |

| Future plansa | 4.1 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 4.1 | nt |

| Protect family | 3.8 | 5.0 | 1.4 | 2.1 | nt |

| Protect community | 2.4 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | nt |

| Protect possessions | 2.2 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 3.1 | nt |

| Faith/pray | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 | nt |

| Protect environmentb | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.0 | nt |

Notes:

People gave more than one response to this open-ended question. These are separate possible responses, Bonferroni correction not applied.

NS=not statistically significant at P=0.05.

nt=not tested owing to sparse responses.

=future plans not specified.

=mentioned some environmental feature (such as dunes).

Source: authors.

Association between concerns at the time of Sandy and future preparedness intentions

Although the topics mentioned by respondents for their concerns during and in the two to three weeks following Sandy were the same as for their intended future preparedness, the responses differed (see Figure 4). During Sandy, people were primarily concerned about protecting family and friends, and safety, whereas when asked about how they intended to prepare for future events, respondents mainly reported doing nothing, evacuating, and general and specific preparation actions, such as buying supplies and ‘being prepared’. Only about 10 per cent had no concerns during Sandy, yet three years later, nearly 35 per cent had decided that they would make no preparations for another event. Of those interviewees who were going to prepare, however, a higher percentage were going to evacuate, seek information, and could list specific preparation actions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of respondents recalling certain concerns during Sandy as compared with the percentage mentioning each item in preparation plans if another severe hurricane were approaching

Source: authors.

Discussion

Effective preparation for future disasters requires coordinated efforts by all parts of society: governmental agencies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), communities, families, and individuals (State of New Jersey, Office of Emergency Management, 2017a, 2017b). Federal actions frequently occur after a disaster, such as through Are You Ready? An In-depth Guide to Citizen Preparedness (FEMA, 2004), and take the form of financial aid, whereas communities have a number of mechanisms with which to address coastal risks, such as the US Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, which includes hazard mitigation, resource protection, community cohesiveness, and land use planning (Collini, 2008). Other tools available at the government and community level include buy-out programmes, building and tax codes, and floodplain map revisions (Grannis, 2011). But these are actions for governments and agencies, and not for NGOs, businesses, or individuals.

In addition, a number of organisations contribute to preparedness, and respond during and immediately following hurricanes or other disasters, including NGOs (such as the Red Cross Movement and the Salvation Army), churches, and local businesses. During Sandy, many such entities helped local communities and families to rebuild their homes and livelihoods. Local businesses, such as grocery stores, department stores, and building supply companies opened their doors and provided food, clothing, cleaning supplies, and other supplies to affected families, and aided the clean-up and helped to rebuild houses. Furthermore, many of these organisations provided information on future preparedness for people to consider (see, for example, American National Red Cross, 2019). This paper concentrates on the preparedness intentions of families and individuals.

Individuals can also prepare for future disasters, and their preparations may be the result of past experience of hurricanes, concerns or fears that they had during a severe storm (Hamama-Raz et al., 2014), personal traits pertaining to optimistic bias (Wienstein, 1989; Trumbo et al., 2016), and distortion of the actual risk (Bukvic and Owen, 2017). Few authors have addressed victims’ concerns during and immediately following a hurricane, or their individual preparedness, although Greenberg, Dyen, and Elliott (2013) noted that most people are simply not prepared. About one-third of this study’s respondents did not plan to prepare, which could reflect, inter alia, an optimistic bias, a fatalistic approach, competing priorities, illness or inability to prepare, or a lack of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

Concerns of respondents during and immediately after Sandy

The questionnaire included open-ended questions about the concerns of respondents during and immediately after Sandy (expressed three years later, requiring them to recall the concerns they had at the time). Considering ‘concerns’ as a part of risk perception, and therefore of disaster preparedness, is a matter only just coming to the fore (Hamama-Raz et al., 2014; Trumbo et al., 2016). Concerns, often manifested as ‘feelings’, mainly related to health and safety during Sandy, and survival, possessions, and buying supplies immediately following Sandy to allow people to live for weeks afterwards when the power was off, infrastructure was destroyed, and transportation was a problem. Few respondents reported concerns about being homeless, recovering from the damage, or making their homes more resilient to future storms, such as by inserting shutters or raising the property.

While concerns about health and safety are real, they result from being in harm’s way (such as owing to not evacuating), being unsafe in homes (such as due to the structure of their home, or from living in a flood-prone region), not having adequate supplies (such as a lack of food, water, and medicines to survive), or worries about friends and family (such as are they safe and do they have sufficient supplies). Once the storm passed, respondents’ concerns shifted to examining their actions before and during the hurricane: Should I have evacuated before or after? Where could I have obtained enough food, water, and medicine? How could I have helped family, friends, and neighbours? How much longer could power be off after another storm? The trajectory of their concerns is a critical factor for managers, educators, and planners who wish to help individuals to improve preparedness. The data suggest that people shift from immediate fears of safety and survival, to what they need for safety and survival, and then to worries about friends, other family members, and neighbours.

From an environmental justice perspective, the concerns of undocumented people may be more important within this vulnerable population, as compared to the rest of New Jersey, because so many interviewees were foreign-born, and English was not the primary language of most Hispanic respondents. The group examined in this study was a vulnerable, coastal population that used the health centres, and did not represent the general population of New Jersey. The evacuation orders issued by the Office of the Governor were targeted principally at the whole state of New Jersey, and were in English. Ideally, event-, site-, and community-specific messages need to be broadcast in appropriate languages, using a medium to which they listen, such as social media. Many others, including governmental agencies, have underscored the importance of education and communication (FEMA, 2004; Basher, 2006; State of New Jersey, Office of Emergency Management, 2017a, 2017b). The ethnic composition of New Jersey is changing, and messages may need to be in several languages, including on mainstream media. Furthermore, the power outages that occurred throughout the state after the hurricane struck meant that there was no television and no charging of mobile telephones, and families obtained information only from battery-operated radios and neighbours. Some respondents reported that they did want to use their car radios because they did not want to run out of fuel—petrol stations were closed, and/or only cash was accepted.

When respondents were asked about preparedness three years later, during the present study, only seven per cent listed actions for local, regional, or federal government. Their suggestions were to activate information centres, build more shelters, provide better transportation, offer more training and education in schools, take better care of seniors, and protect the environment, planet, and trees. In contrast, immediately after Sandy, Burger and Gochfeld (2014b) found that more than 30 per cent of those interviewed thought that government should provide better warning, ensure faster evacuations, supply gas and generators, and no longer permit beach-front homes. A high percentage of people interviewed within 100 days of the storm believed that government should assume a greater role in a strategy for recovery and resilience (Burger and Gochfeld, 2014b).

Both surveys illustrate that respondents who lived through Sandy felt that preparedness included individual and governmental actions, some of which were industrial, such as improving transportation. Although respondents did not mention either businesses or NGOs in their comments about future preparedness, many did note in passing that local businesses and other bodies, such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, provided clothing, food, and other supplies.

Two additional concerns were raised by respondents in the present study: education (information centres and in schools); and better care for others (neighbours and seniors), including having government personnel check on people. The latter also could be performed by churches, police, social organisations, and others. A few respondents said that they should check on undocumented people in their neighbourhood who might be afraid to seek help. Undocumented people are particularly vulnerable because they are scared to ask for help, and do not have identification to enter some shelters or to go to government meetings to request clean-up supplies.

Factors affecting individual preparedness

Much of the literature has highlighted that the public is not ready to respond to the next disaster. Greenberg, Dyen, and Elliott (2013) found that those who were most prepared had experienced a hazardous incident, had distressing memories of a major event, and had expressed a need for greater self-reliance. People incorporate experience into their decision-making process, especially with regard to evacuation orders (Dow and Cutter, 2000). Gender, for instance, can play a part in responses to disasters and in fears of negative events in the future (Hamama-Raz et al., 2014). Following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in August and September 2005, respectively, older males with higher household incomes were associated with lower risk perceptions, such as optimistic bias (Wienstein, 1989; Trumbo et al., 2011). Population density had no effect on outlook, but past experience and the personal impacts of Katrina and Rita heightened risk perceptions. Latinos interviewed in North Carolina felt that they were unprepared for a hurricane, and lacked emergency kits, evacuation plans, and adequate transportation (Burke, Bethel, and Britt, 2012).

There are obvious governmental and community preparedness actions, such as providing emergency shelters, upgrading transportation, and contingency planning for electric power, which must be planned carefully well before a disaster. Preparing for a crisis, such as a severe hurricane, requires several approaches, including crisis management (Flynn, 2012) and an emergency risk communication strategy (Reynolds and Seeger, 2005). These approaches can be modified for site- and storm-specific conditions. In the case of Sandy and other hurricanes, it is often the governor who issues evacuation orders (and is thus functioning as the ‘leader’). Yet, simply issuing an order does not necessarily ensure compliance, particularly if people do not hear the message, do not listen to it, or underestimate the risk. Some of the respondents who were in areas with evacuation orders did not heed them, although some left after the storm because of extreme flooding of their homes, a lack of food and water, and the absence of electricity (and hence heat).

In the present study of a vulnerable population in New Jersey, 35 per cent said that they would not prepare in the future, 12 per cent said that they might prepare (almost one-half of whom stated that they might evacuate), and 54 per cent said that they were going to prepare. Their personal actions, however, varied greatly, from seeking information, to buying supplies and an emergency kit, to protecting family, community, and possessions. Only slightly more than one-half, therefore, were intending to prepare themselves for a future event, and most only when a storm was approaching. There were no gender differences in whether they were going to do nothing or intended to prepare.

Many respondents mentioned that they stayed with family and friends after evacuating. The resilience of vulnerable populations that are low income, minority, or elderly may be highly dependent on extended families and social networks (Eisenman et al., 2007). The unique social networks of some minority communities may lend themselves to additional advice from a respected organisation, such as the local church or community centre. Indeed, many of the respondents in the present study reported that they were not going to prepare in the future because ‘it was God’s will’, or because ‘God will take care of me’. This confirms that there is a role for the church or other community leaders in encouraging appropriate responses to local or state evacuation orders, or even in offering advice to prepare adequately (Keller, 2017). A few people pointed out that ‘God helps those who help themselves’. The church and other entities also function as the organisational structure of the community, and they aided the local community in many ways during Sandy. Providing information directly to churches and other community organisations before the next crisis can help with the establishment of focus groups to consider how to prepare for it. For instance, in a community where few people have cars, transportation contingency plans could be addressed well before the advent of a disaster. Without a car, people are unable to evacuate easily beforehand. In the present study, though, people who relied on cars were at a disadvantage after the hurricane hit because roads were closed owing to flooding, downed wires, trees, or other debris. Gasoline quickly became unavailable. In addition, many people lived too far away to walk to their health centre, whereas those who normally walked could still do so.

Many of the respondents mentioned buying food, canned goods, and water, indicating not only the importance of these items, but also of having sufficient nutritional support for babies, young children, the elderly, and those with special dietary requirements (Trento and Allen, 2016). However, some respondents said that their local small grocery stores had run out of canned goods and water even before the arrival of Sandy, making their community even more vulnerable. Some respondents noted that they went to shelters where they could not get appropriate food as often as needed for diabetics, and that children with asthma were forced to remain in apartments or houses where the first floor was flooded for days, and mould levels increased. Information on dealing with disasters in relation to people with special needs could greatly improve individual preparedness, and reduce parental anxiety and stress.

Temporal pattern of responses

Individual decisions on preparedness and evacuation are also influenced by the time since the last event, and the rarity of the incident. A comparison of the responses of people living along the Jersey Shore 100 days after Sandy (Burger and Gochfeld, 2014a, 2014b) with the present study showed that:

the percentage of people planning on doing nothing for the next storm increased between the first and second study;

the percentage of people seeking information decreased between the first and the second study;

individual preparedness was less in the second (later) study, although it was still higher than it was pre Sandy;

personal resiliency (‘hardening’ with shutters, raising the house on pilings) was low in both cases; and

there should be more government actions (resiliency), and they should occur sooner.

In New Jersey, where devastating storms or hurricanes have been rare, the willingness to prepare and seek information has decreased with time since the event. In other places where flooding is not common, risk perceptions and preparedness have also diminished with time since the event (Siebeneck and Cova, 2012). In contrast, in locations where hurricanes or other severe storms are common and expected, perceptions of risk do not weaken over time (Williams et al., 1999; Trumbo et al., 2011).

Individual health, as well as healthcare facilities, are affected long after a disaster (Sharp et al., 2016), and perceptions and preparedness decrease as well. Since perceptions of risk wane, people become complacent about preparing for the future, even though the probability of a severe hurricane in New Jersey, for example, is low. Consequently, they will be unable to act quickly and adequately if there is little warning in advance.

Evacuation and relocation decisions

The amount of technical and popular information on hurricanes and preparedness has increased substantially since Katrina, in particular. There is better information on storm tracks and intensities, on evacuation routes, and on the availability of shelters. However, there are also persistent scientific uncertainties (Dow and Cutter, 2000). Predictions of the severity of the approaching Sandy differed over a five-day period, and conflicting ‘models’ were presented on television, causing confusion and abetting non-preparedness among optimists. Predicting the severity and geography of the landfall of a storm is an inherently uncertain task because of the complexities of weather processes. Predictions vary as the storm approaches, and one job of the National Weather Service and the media is to communicate these uncertainties (Freedman, 2013b). Thus, governmental evacuation decisions (mandatory or recommended) need a clear and consistent approach, while still retaining the flexibility to adjust evacuation recommendations (Powell, Hanfling, and Gostin, 2012). The almost universal loss of power in New Jersey following Sandy impaired communication because radios and televisions did not work, and both landline and mobile telephone services were interrupted. Once a storm hits, evacuation is hampered by infrastructure failures, as well as the absence of clear consistent criteria to guide evacuation decisions, which clearly was the case with Sandy (Powell et al., 2012). Understanding how people make decisions about whether to evacuate or shelter in place is critical to preparing for future hurricanes (Trumbo et al., 2016). The reasons why some people opt not to evacuate include individual characteristics, risk perceptions, social influences, and access to resources (Riad, Norris, and Ruback, 1999). Other factors have to do with a lack of transportation or a suitable place to go. In the present study, transportation was an issue, as many people did not have a car, particularly Hispanics/Latinos. Hence, public transportation companies have to improve their (resiliency) responses to disasters such as Sandy (Dreary, Walker and Woods, 2013). Furthermore, not everyone was willing to go to an emergency shelter; in some cases, people avoided doing so because they could not bring pets, or they were worried about the safety of their possessions at home, or while in the shelter.

Experience had an important influence on people’s evacuation behaviour at the time of Sandy. The arrival of Hurricane Irene in 2011 was portrayed in the media as a severe event and there was widespread coastal zone evacuation. But the coastal damage did not materialise, leading people to assume that the risks posed by Sandy were also exaggerated. This represents optimistic bias (Wienstein, 1989; Trumbo et al., 2011), whereby individuals do not think they are going to be affected (despite warnings to the contrary), especially when they have little experience of the hazard.

Other reasons for avoiding evacuation included knowledge of previous storm-related deaths and damage, and perceived racism and inequities (Elder et al., 2007). Others evacuated because they had experienced injury or destruction in a previous storm, and thought the impending storm would be worse than predicted (Lindell and Perry, 2004). Risk perceptions about the potential of a storm are also an important predictor of storm preparedness and evacuation (Peacock, Brody, and Highfield, 2004). Homeowners who live in areas of high hurricane wind risk usually have a higher perception of the danger (Peacock, Brody, and Highfield, 2004). However, New Jersey is not at high risk of hurricanes, and Sandy was the most severe storm to strike the state.

Another option for people living along coastlines is relocation. The relocation of whole vulnerable communities has been suggested for some places that were devastated by Sandy, and are especially vulnerable because of their low elevation, the lack of protective dunes, and openness to high winds (Bukvic and Owen, 2017). The term ‘retreat’ is employed when it involves relocating blocks or communities (Karl, Melillo, and Peterson, 2009).

There are many examples of community relocation, particularly in the area of Chesapeake Bay, an estuary in the states of Maryland and Virginia (Carlisle, Conn, and Fabijanski, 2006; Gibbons and Nicholls, 2006). One difficulty with community retreating, of course, is that decisions and financing have to occur between disasters, yet immediately following such events, people begin to raise houses and repair damage before relocation can be considered. Relocation often requires that an agency take responsibility in a regional planning context (Leighton, Shen, and Warner, 2011). Currently there is no single governmental agency responsible for a relocation programme (Bukvic and Owen, 2017). No one in the present study mentioned relocation, either for themselves or relatives, even though three per cent of the respondents were still absent from their Sandy-era homes three years later. Moreover, people who own their home are reluctant to move if they still have a mortgage (Elliott and Rais, 2006).

In a survey of 46 households living in highly-affected communities in New Jersey and New York following Sandy, residents preferred structural solutions, although they were not fully opposed to the possibility of relocation (Bukvic and Owen, 2017). The matter of relocation, or formal retreat, thus needs to be an open and ongoing discussion in low-lying coastal communities in New Jersey and elsewhere. Such a discussion needs to occur well before there is the threat of a new hurricane, and in a context of appropriate local and regional planning, and sufficient funding (Laczko and Aghazarm, 2009; Bukvic and Owen, 2017).

Implications for public policymakers

The public is increasingly involved in planning and policy decisions (Peacock, Brody, and Highfield, 2004), making it essential that advice and mandates targeted at the public during a disaster are consistent. Since risk perception is an important contributor to individual decisions about planning and evacuation, it is advantageous to have officials at all levels providing consistent information. The form (print, radio, social media, or television), method, presentation, and language of communications are also significant. Language is a particular barrier to disaster preparedness before, during, and after a hurricane (Burger et al., 2017). Language was one of the problems mentioned by members of a Latino migrant population in North Carolina in relation to their lack of preparedness (Burke, Bethel, and Britt, 2012); they suggested having messages and emergency broadcasts in Spanish. Most of the Hispanic respondents (83 per cent) in the current study said that Spanish was their primary language, underlining the need to use a range of media and approaches to transmit the necessary public health messages about impending hurricanes and severe storms. Even with excellent communication before an event, if the power goes off, most of the communication channels do so as well. Emergency plans must be developed for this eventuality. No one predicted that power would be off for two weeks in many parts of New Jersey.

Few respondents (seven per cent) in the present survey felt that there were government actions that would aid recovery and resiliency, and that the government had not attended to these issues. One issue cited was the lack of help for seniors and for undocumented people, who were reluctant to ask for assistance because they believed that they would be in some jeopardy. Another was the absence of suitable shelters, with adequate medicine and food for people with specific needs.

Finally, the matter of government funding for research following disasters needs to be addressed. Despite widespread recognition of urgent research needs pertaining to the impact of Sandy, it took the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) months to develop its request for proposals, more months for review and approval, and still more months to make funding available—hence why the interviews for this study were conducted between two and three years after Sandy.

Limitations

One should keep in mind the fact that interviews occurred between two and three years after Sandy when reading the results of this study. The preparedness questions were near the end of the interview schedule, and were left unanswered by respondents who were called in to their doctor’s appointment before completion. The preparedness question was ‘How will you prepare in the future?’, not ‘What hurricane preparations have you made since Sandy?’. Finally, the interviews took place at federally qualified health centres, and so people who may have moved away from the Shore or even to other states were not interviewed.

Conclusion

The people interviewed for this study provided many comments on their future preparedness intentions for when a severe storm is approaching. Slightly more than one-half intended to prepare for the next storm, ranging from individual to community and governmental actions. While some people said that they would do nothing, others planned to buy supplies or generators, seek more information, make plans for family and possessions, and encourage government initiatives. Having experienced delayed access to a health centre, medical facility, or pharmacy predicted increased intention to prepare better for the next storm.

Many of the respondents’ suggestions yield insights for governmental agencies, as well as NGOs, to consider now—that is, before the next hurricane. They could be implemented easily, including providing more information and more information centres, more shelters (better supplied), better emergency transportation, backup electrical sources (such as generators), and a method of checking on seniors. Moreover, 65 per cent of respondents planned on taking personal action to reduce their risk, including evacuating, seeking information, buying necessary supplies, and protecting their family. Their responses were enlightening in that they revealed that survivors of Sandy are prepared to listen to governmental advice, purchase the necessary supplies, and protect their homes and families if another severe storm is approaching.

It may seem obvious, but the data here indicate that in areas with a low occurrence of hurricanes, people forget the severity of the effects of such events over time. What is more, the percentage opting to do nothing increased, the percentage seeking information decreased, the willingness to prepare diminished, and the belief that government should do something weakened. Even three years later, people remembered that they were most concerned about the health and safety of friends and family members, and their future actions mainly concerned ‘being prepared’ and engaging in specific endeavours such as buying food, water, and other supplies. Agencies and organisations dealing with preparedness would do well to stress and re-emphasise the ways in which people can make their friends and families safe during and immediately after a hurricane (such as the location of designated meeting places), in addition to the more obvious advice to buy batteries, food, and water. Attention should also be paid to offering advice to individuals about health and safety in the weeks after a long-lasting disaster.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to Kathy Grant-Davis, the then Chief Executive Officer of the New Jersey Primary Care Association, as well as to her Executive Board, and the directors and medical directors of the federally qualified health centres, Sandra Adams, Marillyn Cintron, David Friedman, Mitchell Rubin, Marta Silverberg, and Rudine Smith, for permission to interview patients in their facilities. Thanks are extended too to the interviewers, Clarimel Cepeda, Marta Hernandez, Ahmend Nezar, Alan Perez, and Ana Quintero, and to Christian Jeitner and Taryn Pittfield for logistical and graphic support. The authors are also grateful to all of the respondents who graciously agreed to be interviewed.

This study was supported by a CDC grant (CDC-RFA-13-001) to the New Jersey Department of Health, which included collaboration with the New Jersey Department of Human Services, the New Jersey Medical School, and Rutgers University (including its Division of Life Sciences), as well as a centre of excellence grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES005022). Support was also received from the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch project 1004696).

The project and protocol were approved by the New Jersey Primary Care Association, the directors of the participating health centres, and Rutgers University’s IRB (Protocol E14–319, Notice of Exemption).

The views and opinions presented in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Joanna Burger, Distinguished Professor of Biology, Division of Life Sciences, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute and School of Public Health, Rutgers University, United States.

Michael Gochfeld, Professor Emeritus, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Rutgers University, United States.

Clifton Lacy, Distinguished Professor of Professional Practice, School of Communication and Information, Clinical Professor of Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, and Director, Center for Emergency Preparedness, Infrastructure and Communication, Rutgers University, United States.

References

- Abramson DM et al. (2015) The Hurricane Sandy Place Report: Evacuation Decisions, Housing Issues and Sense of Community. Briefing Report 2015_1. 1 July. National Center for Disaster Preparedness, Columbia University, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KS, Ryan A, and Measham TG (2012) ‘Managed retreat of coastal communities: understanding responses to projected sea level rise’. Journal of Environmental and Planning Management. 55(4). pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar]

- American National Red Cross (2019) ‘How to prepare for emergencies’. https://www.redcross.org/get-help/how-to-prepare-for-emergencies.html (last accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Bandura A. (1997) Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Barnegat Bay Partnership (2012) ‘Special report: Sandy—a record-setting storm’. Barnegat Bay Beat. 20–27. Barnegat Bay Partnership, Tom’s River, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Barone DA, McKenna KK, and Farrell SC (2014) ‘Hurricane Sandy: beach–dune performance at New Jersey Beach Profile Network sites’. Shore Beach. 82(4). pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Basher R. (2006) ‘Global early warning systems for natural hazards: systematic and people-centred’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 364(1845). pp. 2167–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borough of Mantoloking (2012) Mantoloking and Superstorm Sandy. http://www.mantoloking.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/cm111912.pdf (last accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Bukvic A. and Owen G. (2017) ‘Attitudes towards relocation following Hurricane Sandy: should we stay or should we go?’. Disasters. 41(1). pp. 101–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. (2015) ‘Ecological concerns following Superstorm Sandy: stressor level and recreational activity levels affect perceptions of ecosystems’. Urban Ecosystems. 18(2). pp. 553–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. and Gochfeld M (2014a) ‘Health concerns and perceptions of central and coastal New Jersey residents in the 100 days following Superstorm Sandy’. Science of the Total Environment. 481(15). pp. 611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. and Gochfeld M. (2014b) ‘Perceptions of personal and governmental actions to improve responses to disasters such as Superstorm Sandy’. Environmental Hazards. 13(3). pp. 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. and Gochfeld M. (2017) ‘Perceptions of severe storms, climate change, ecological structures and resiliency three years post-hurricane Sandy in New Jersey’. Urban Ecosystems. 20(6). pp. 1261–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gochfeld M, and Lacy C. (2019) ‘Ethnic differences in risk: experiences, medical needs and access to care after Hurricane Sandy New Jersey’. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 82(2). pp. 128–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J, Gochfeld M, Pittfield T, and Jeitner C. (2017) ‘Responses of a vulnerable Hispanic population in New Jersey to Hurricane Sandy: access to care, medical needs, concerns, and ecological ratings’. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 80(6). pp. 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke S, Bethel JW, and Britt AF (2012) ‘Assessing disaster preparedness among Latino migrant and seasonal farmworkers in eastern North Carolina’. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 9(9). pp. 3115–3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle A, Conn C, and Fabijanski S. (2006) Dorchester County Inundation Study: Identifying Natural Resources Vulnerable to Sea Level Rise over the Next 50 Years? Center for Geographic Information Sciences, Townson University, Townson, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Collini K. (2008) Coastal Community Resilience: An Evaluation of Resilience as a Potential Performance Measure of the Coastal Zone Management Act. Final Report of the Coastal Resilience Steering Committee, Coastal States Organization, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Crosset KM, Culliton TJ, Wiley PC, and Goodspeed TR (2013) Population Trends along the Coastal United States: 1980–2008. Coastal Trends Report Series. September. https://aamboceanservice.blob.core.windows.net/oceanservice-prod/programs/mb/pdfs/coastal_pop_trends_complete.pdf (last accessed on 22 February 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Dow K. and Cutter SL, (2000) ‘Public orders and personal opinions: household strategies for hurricane risk assessment’. Environmental Hazards. 2(4). pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dreary DS, Walker KE, and Woods DD (2013) Resilience in the face of a superstorm: a transportation firm confronts Hurricane Sandy. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 57(1). pp. 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman DP, Cordasco KM, Asch S, Golden JE, and Glik D. (2007) ‘Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: lessons from Hurricane Katrina’. American Journal of Public Health. 97(S1). pp. S109–S115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder K. et al. (2007) ‘African Americans’ decision not to evacuate New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina: a qualitative study’. American Journal of Public Health. 97(S1). pp. S124–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JR and Rais J. (2006) ‘Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: social differences in human responses to disasters’. Social Science Research. 35(2). pp. 295–321. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) (2004) Are You Ready? An In-depth Guide to Citizen Preparedness. FEMA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn T. (2012) ‘Into the crisis vortex: managing and communicating issues, risks, and crises’. Journal of Professional Communications. 2(1). pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A. (2013a) ‘Heeding Sandy’s lessons, before the next big storm’. Climate Central. 30 April. http://www.climatecentral.org/news/four-key-lessons-learned-from-hurricane-Sandy-15928 (last accessed on 22 February 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A. (2013b) ‘Experts say Sandy showed limits of an accurate forecast’. Climate Central. 13 October. http://www.climatecentral.org/news/1-year-later-expersts-say-hurricane-sand-showed-limits-of-an-accurate-forecast-16648 (last accessed on 7 March 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Genovesa E. and Przyluski V. (2013) ‘Storm surge disaster risk management: the Xynthia case study in France’. Journal of Risk Research. 16(7). pp. 825–841. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons SJA. and Nicholls RJ (2006) ‘Island abandonment and sea-level rise: an historical analog from the Chesapeake Bay, USA’. Global Environmental Change. 16(1). pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Grannis J. (2011) Adaptation Tool Kit: Sea-level Rise and Coastal Land Use. October. Georgetown Climate Center, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MR, Dyen S, and Elliott S. (2013) ‘The public’s preparedness: self-reliance, flashbulb memories, and conservative values’. American Journal of Public Health. 103(6). pp. e85–e91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TM and Sobel AH (2013) ‘On the impact angle of Hurricane Sandy’s New Jersey landfall’. Geophysical Research Letters. 40(10). pp. 1312–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin SH (2013) The Impact of Superstorm Sandy on New Jersey Towns and Households. School of Public Affairs and Administration, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Hamama-Raz Y. et al. (2014) ‘Gender differences in psychological reactions to Hurricane Sandy among New York metropolitan area residents’. Psychiatric Quarterly. 86(2). pp. 285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl TR, Melillo JM, and Peterson TC (eds.) (2009) Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Keller J. (2017) ‘The complicated role churches play in disaster relief’. Pacific Standard. 1 September. https://psmag.com/news/the-complicated-role-churches-play-in-disaster-relief (last accessed on 22 February 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Keane TM, Ursano RJ, Mokdad A, and Zaslavsky AM (2008) ‘Sample and design considerations in post-disaster mental health needs assessment tracking surveys’. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 17(S2). pp. S6–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laczko F. and Aghazarm C. (eds.) (2009) Migration, Environment and Climate Change: Assessing the Evidence. International Organization for Migration, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Lane LK et al. (2013) ‘Health effects of coastal storms and flooding in urban areas: a review and vulnerability assessment’. Journal of Environment and Public Health. Article ID 913064. 10.1155/2013/913064 (last accessed on 22 February 2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leighton M, Shen X, and Warner K. (eds.) (2011) Climate Change and Migration: Rethinking Policies for Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction. 15/2011. Institute for Environment and Human Security, United Nations University, Bonn. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell MK and Perry RW (2004) Communicating Environmental Risk in Multiethnic Communities. Sage Publishing, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Murakaml N, Siktel HR, Lucido D, Winchester JF, and Harbord NB (2015) ‘Disaster preparedness and awareness of patients on hemodialysis after Hurricane Sandy’. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10(8). pp. 1389–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neria Y. and Shultz JM (2012) ‘Mental health effects of Hurricane Sandy: characteristics, potential aftermath, and responses’. Journal of the American Medical Association. 308(24). pp. 2571–2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NJPCA (New Jersey Primary Care Association) (2017) ‘About us: the New Jersey Primary Care Association’. https://www.njpca.org/about-us/ (last accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Nordstrom KF and Mitteager WA (2001) ‘Perceptions of the value of natural and restored beach and dune characteristics by high school students in New Jersey, USA’. Ocean Coastal Management. 44(7). pp. 545–559. [Google Scholar]

- North C, Oliver J, and Pandya J. (2012) ‘Examining a comprehensive model of disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder in systematically studied survivors of 10 disasters’. American Journal of Public Health. 102(10). pp. e40–e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NPCC2 (New York City Panel on Climate Change) (2013) Climate change information 2013. Office of the Mayor, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock WG, Brody SD, and Highfield W. (2004) ‘Hurricane risk perceptions among Florida’s single family homeowners’. Landscape and Urban Planning. 73(2). pp. 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Plant NG et al. (2010) ‘Forecasting hurricane impact on coastal topography’. EOS. 91(7). pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Powell T., Hanfling D, and Gostin LO (2012) ‘Emergency preparedness and public health: the lessons of Hurricane Sandy’. Journal of the American Medical Association. 308(24). pp. 2569–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries AJ, Miller DL, and Branch LC (2008) ‘Identification of structural features that influence storm-related dune erosion along a barrier island ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico’. Journal of Coastal Research. 24(4A). pp. 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Psuty NP and O’Fiara DD (2002) Coastal Hazard Management. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. and Seeger MW (2005) ‘Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model’. Journal of Health Communication. 10(1). pp. 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riad JD, Norris FH, and Ruback RB (1999) ‘Predicting evacuation in two major disasters: risk perception, social influence, and access to resources’. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 29(5). pp. 918–934. [Google Scholar]

- SAS (Statistical Analysis System) (2005) Statistical Analysis. SAS, Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. et al. (2015) ‘Study design and results of a population-based study on perceived stress following Hurricane Sandy’. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 10(3). pp. 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp MJ, Ledneva T, Lauper U, Pantea C, and Lin S. (2016) ‘Effect of Hurricane Sandy on health care services utilization under Medicaid’. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 10(3). pp. 472–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebeneck LK and Cova TJ (2012) ‘Spatial and temporal variation in evacuee risk perception throughout the evacuation and return-entry process’. Risk Analysis. 32(9). pp. 1468–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of New Jersey, Office of Emergency Management (2017a) ‘Your kit/your plan: be ready’. http://ready.nj.gov/plan-prepare/your-kit-plan.shtml (last accessed on 22 February 2019).

- State of New Jersey, Office of Emergency Management (2017b) ‘Hurricanes and tropical storms’. https://www.nj.gov/njoem/plan-prepare/hurricanes.shtml (last accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Swerdel JN, Rhoads GG, Cosgrove NM, and Kostis JB (2016) ‘Rates of hospitalization for dehydration following Hurricane Sandy in New Jersey’. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 10(2). pp. 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trento L. and Allen S. (2016) ‘Hurricane Sandy: nutrition support during disasters’. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 29(5). pp. 576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo C, Lueck M, Marlatt H, and Peck L. (2011) ‘The effect of proximity to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on subsequent hurricane outlook and optimistic bias’. Risk Analysis. 31(12). pp. 1907–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo CW. et al. (2016) ‘A cognitive-affective scale for hurricane risk perception’. Risk Analysis. 36(12). pp. 2233–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USGS (United States Geological Survey) (2010) Impacts and Predictions of Coastal Change during Hurricanes. Fact Sheet 2010–3012. US Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Wienstein N. (1989) ‘Optimistic biases about personal risks’. Science. 246(4935). pp. 1232–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Brown W, Greenberg M, and Kahn M. (1999) ‘Risk perception in context: the Savannah River site stakeholders study’. Risk Analysis. 19(6). pp. 1019–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]