Abstract

Graphene quantum dots (GQDs) are carbonaceous nanodots that are natural crystalline semiconductors and range from 1 to 20 nm. The broad range of applications for GQDs is based on their unique physical and chemical properties. Compared to inorganic quantum dots, GQDs possess numerous advantages, including formidable biocompatibility, low intrinsic toxicity, excellent dispensability, hydrophilicity, and surface grating, thus making them promising materials for nanophotonic applications. Owing to their unique photonic compliant properties, such as superb solubility, robust chemical inertness, large specific surface area, superabundant surface conjugation sites, superior photostability, resistance to photobleaching, and nonblinking, GQDs have emerged as a novel class of probes for the detection of biomolecules and study of their molecular interactions. Here, we present a brief overview of GQDs, their advantages over quantum dots (QDs), various synthesis procedures, and different surface conjugation chemistries for detecting cell-free circulating nucleic acids (CNAs). With the prominent rise of liquid biopsy-based approaches for real-time detection of CNAs, GQDs-based strategies might be a step toward early diagnosis, prognosis, treatment monitoring, and outcome prediction of various non-communicable diseases, including cancers.

2. Introduction

The ultrasmall QD nanocrystals (1–10 nm), which are based on semiconductors, were revealed in 1983 and have since had great success in the domains of optics, electronics, and catalysis, bringing in a new era of nanotechnology.1 A heavy metal core surrounded by a bandgap semiconductor shell, such as CdTe, characterizes the vast majority of QDs. SiO2 surrounds PbSe, ZnSe, or CdS core materials, overcoming the surface deficit and boosting the quantum yield. Small particle size, customizable composition and properties, high quantum yield, great brightness, and intermittent light emission are just a few of the intriguing characteristics of QDs that have drawn them into a variety of applications.2−4 Metallic QDs like CdS, CdSe, and CdTe were previously the most researched QDs because of their superior optical and electrochemical properties. These QDs have been used for many studies; CdTe/CdSe QD-labeled oligonucleotides and hemin/G-quadruplex DNzyme-conjugated DNA assembly was used for the detection of lysozyme based on the analyte-induced rolling cycling amplification system.5 In another research study, following the structural and photonic transition of CdTe-QDs immobilized on paper, evoked by the silver ion (Ag+) separated from silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with a cation exchange reaction, a concise, low-cost visual fluorescence immunosensor was created for disease-related biomarkers in biofluids.6 For the quantitative or qualitative measurement of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a titanium carbide (Ti3C2) MXene QDs-encapsulated liposome with excellent photothermal activity was created using a near-infrared (NIR) photothermal immunoassay method.7 On the other hand, their biological applications are constrained by their cytotoxicity, high energy requirements, and nonrenewable chemical synthesis. To reduce these factors associated with heavy metals, cadmium-free QDs such as carbon, graphene, and silicon have been developed. These QDs exhibit equivalent optical properties.8

Carbon-based materials play an essential role in developing nanomaterials and fabricating biosensors for various biomedical applications, such as immunoassay of protein,9 fluorometric immunoassay for carcinogens (aflatoxin B 1),10,11 and other cancer biomarkers.12 One such study describes the development of a photoelectrochemical (PEC) biosensing device for the responsive and precise detection of thrombin utilizing glucose oxidase-encapsulated DNA nanoflowers (GOx-DFs) and graphene oxide-coated copper-doped zinc oxide quantum dots (Cu0.3Zn0.7O-GO QDs) as photoactive substances.13 In one report, the one-step process was used in the manufacture of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) for quick and accurate metal ion identification. An affordable and ecologically favorable precursor was ascorbic acid. Reactors with high temperatures and pressures were employed for this.

In addition to fluorometric assay, these QDs are also employed in electrochemical detection of several analytes, including environmental pollutants.14,15 The exceptional and remarkable characteristics of these carbon-based materials have propelled current research and development. Researchers have expended significant effort in exploring carbon nanomaterials for diverse biomedical applications due to their unique physical properties, including optical, structural, and thermal properties.16,17 Due to its structure and the delocalization of electrons, graphene, a zero-bandgap semiconductor, cannot emit light (Figure 1).18

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of graphene quantum dot showing different groups of atoms.

The high mechanical and thermal conductivity of the carbon allotrope graphene has led to the use of graphene-based materials in several biomedical applications, including sensors and bioimaging (Figure 2). Cutting graphene into nanometer-scale pieces and creating a gap therein is a viable strategy to get around this restriction because of the quantum confinement in graphene of any finite size due to its infinite exciton Bohr radius, known as the GQDs.19 GQDs, the latest zero-dimensional member of the carbon family, are composed of single or several layers of 10-nm-thick graphene sheets. GQDs have demonstrated novel charge transport and light absorption/emission phenomena and their bandgap energy can vary by up to 3 eV depending on their size. GQDs have several distinct advantages over their 2D counterparts, graphene sheets, including bandgap opening brought on by quantum confinement, excellent dispensability, more abundant active sites (edges, functional groups, dopants), better tunability in physicochemical properties, and a size comparable to biomolecules. These advantages enable new application possibilities.20,21 The excellent electrical capabilities of sp2 carbon nanoparticles, which have an enormous specific surface area and a lot of functional groups on the edges, are combined with the unique optical and structural advantages of GQDs to create a cutting-edge nanomaterial.22,23

Figure 2.

GQDs and their surface biofunctionalization for different sensing platforms.

However, there has always been a need to find low-cost, nontoxic, eco-friendly, safe, sustainable, and biocompatible materials to synthesize/fabricate. GQDs provide all these features and outshine other classes of QDs owing to their unique properties.24 Thus, GQDs, a new class of fluorescent materials derived from the carbon nanomaterial family, have perfect chemical and physical properties for usage in biological sensors.25,26 An outline of GQD synthesis techniques, including top-down and bottom-up methods, surface conjugation techniques, and their use in identifying circulating nucleic acids is provided here.

3. Synthetic Strategies for GQDs

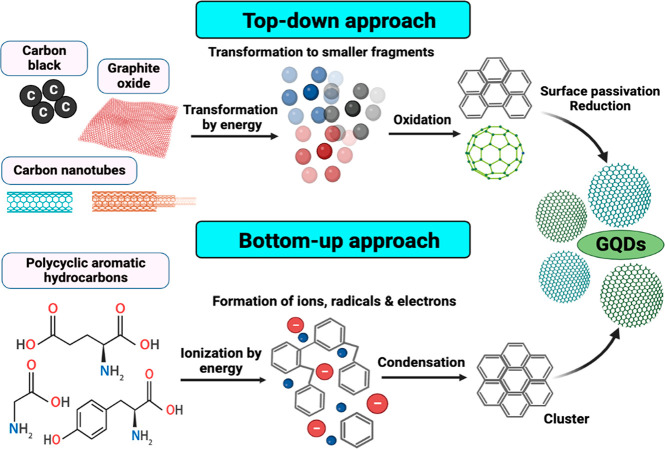

The graphene-based materials used to create GQDs cannot show luminescence properties, as graphene is a zero-band gap material. Therefore, manipulating the graphene band gap by various means has sparked considerable interest, including cutting graphene into GQDs to induce photoluminescence (PL) and alteration by various synthetic procedures.27 Additionally, it has been observed that the synthesis process and precursor material employed affect the characteristics of GQDs.28 Several synthetic techniques have obtained GQDs with ideal chemical, optical, and electrical properties. Thus, recent advances in GQD synthetic techniques have been fueled by the ease of synthesis and availability of reactants.29 The top-down and bottom-up approaches are two broad categories used to categorize the synthetic routes toward creating GQDs based on the reaction mechanism involved (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Two major synthetic approaches for the fabrication of GQDs: Top-down method simply converts graphite to graphene and the bottom-up method produces graphene from small carbon precursors.

3.1. Top-Down Strategies

The top-down strategy is well-established and based on widely available bulk precursors such as graphitized materials like graphite and graphene oxide. This strategy aids in tuning various properties such as size and luminescence and obtains the desired GQDs; the bulk carbon materials are typically exfoliated chemically or physically.30 Therefore, cutting the sp2 or sp3 carbon allotropes of graphene, graphene oxide, carbon fibers, and carbon black using acidic oxidation, microfluidization, exfoliation, and electrochemical oxidation is referred to as top-down techniques (Figure 4).31 Such methods have several advantages, including an ample supply of raw materials, a simple process with fewer steps, and the large-scale development of bulk reagents and precursors. In addition, the GQDs prepared using this method primarily have the functional group oxygen on their surface and exhibit high water solubility and surface passivation due to the “edge-functionalized GQDs”.32−34 As a result, utilizing this type of strategy for controlling morphology appears to be crucial. Some of them are not feasible to implement on a large scale due to their high cost; scalability on a large scale is also tricky; and other issues include the use of acids, high temperatures, and the environment.35,36

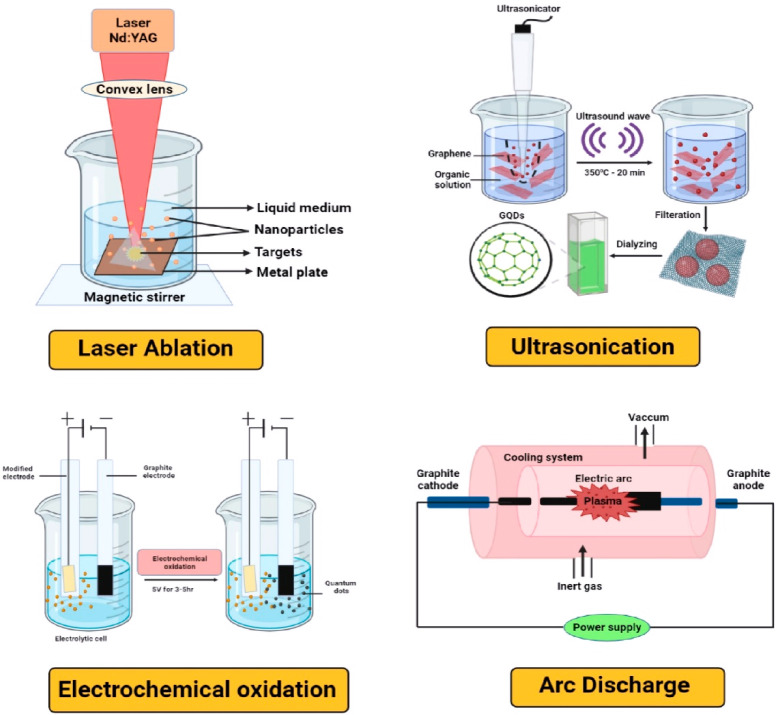

Figure 4.

Different top-down approaches for the synthesis of GQDs.

3.1.1. Laser Ablation

This technique primarily employs a higher-energy laser pulse to irradiate the surface target to reach them in a thermodynamic state, resulting in temperature and pressure elevation, as well as heat generation and evaporation, which converts them to a plasma state. Finally, the vapor is collected and crystallized into nanoparticles.37 The process can also be defined as removing materials from solid or liquid surfaces using laser beams. This method is widely used to modulate the size of GQDs, but it requires multiple steps and purification in a separate step.38 These GQDs have excellent fluorescent properties to detect different biomarkers.39

The fluorescence emission spectra of laser ablation-GQDs exhibit blue-shifted emission based on CO-GQDs, which are defined by the size of particles and surface characteristics. GQDs coupled with laser ablation (LA) have an average size of about 1.8 nm and a depth of one layer of graphene.40 One of the most potent methods for synthesizing unique nanostructures is pulsed laser ablation in liquids (PLAL).41,42 It is simple to make GQDs and GOQDs featuring tunable oxygen functional groups by only altering the laser wavelength for PLAL.43 By laser beam ablation in a fluid, applying pulsed graphene and adding ammonia–water to the graphene solution, nitrogen-doped GQDs were created.44 In a study, amino-based GQDs were made using polypyrrole (PPy) as an amine source and graphite as a carbon substrate using a one-step pulsed laser ablation (PLA) technique for the sensitive recognition of Fe3.45

3.1.2. Arc Discharge

The action of creating a current between two electrodes (usually graphite rods) that causes them to vaporize is known as arc discharge. As a result, soot is produced, which may contain different graphene-based nanomaterials.46 Hoffman and Krastchmer used the arc-discharge method to create buckminsterfullerene for the first time in 1990. The arc-discharge technique produces pure, B-doped graphene in the form of soot collected in the electric oven during the arc-discharge process. This is an electrical breakdown of a gas that has developed an in-progress plasma discharge. It is the most suitable procedure for producing thermal plasma characterized by high-energy substances and the local thermal equilibrium state.47−49 Although this approach for synthesizing GQDs looks to be a simple conventional method, it is challenging to achieve a high yield and requires careful control of experimental conditions. In a study, a water arc discharge technique with a controlled degree of oxidation is used to manufacture blue-emitting GQDs with tunable PL emission.50

3.1.3. Electrochemical Oxidation

Another possible method widely used to synthesize single-layer GQDs with a uniform size and high production yield is the electrochemical cleavage of carbon-based precursors. This technology has been thoroughly studied due to its low cost, high production and reproducibility, and simple operating principles. To convert functional GQDs with an average size of 3–5 nm from graphene film, Qu et al. established an electrochemical method.51 The synthesized GQDs showed green fluorescence and could last several months in an aqueous solution without losing stability. Electrochemical synthesis offers a route for the more accurate synthesis of GQDs by selectively oxidizing the precursor material by the applied electric potential. It can be further functionalized by altering the electrolyte solution. Due to the relative simplicity of the setup and the absence of powerful oxidizing agents,52 in the form of precipitation, graphene nanosheets are produced via the electrochemical exfoliation of graphite rods with oxidizing chemicals like KNO3.53

3.1.4. Ultrasonication

Acoustic cavitation is a quick and efficient process for producing nanosized particles in which bubbles play a crucial role after a series of steps, such as production, nucleation, and rapid collapse of bubbles. In liquid, ultrasound can generate alternating low- and high-pressure waves, creating and bursting tiny vacuum bubbles. This cavitation generates high-speed impinging liquid jets and significant hydrodynamic shear forces. Therefore, ultrasonication can turn graphene sheets into GQDs by combining these properties.54

The one-phase approach used to make the GQDs required expensive equipment, and the environment was also unusual. Zhuo et al. proposed the new method, stating that ultrasonic equipment was used to explain graphene oxidation in concentrated nitric acid and sulfuric acid solutions at room temperature (RT) for 12 hours. The next step involved calcining the received mixture at 350 °C for 20 min to remove concentrated solutions (nitric acid and sulfuric acid). The next step involves filtration with a microporous membrane (0.22 m), resulting in a black suspension from a brown filtered solution. Finally, GQDs are obtained by dialyzing the obtained solution.55 Graphene oxide (GO) is oxidized ultrasonically to transform into nanometer-sized species, which are further chemically reduced and doped with nitrogen to form a novel catalyst, N-GQDs for electrochemical detection of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT).56 An innovative and effective process was used to create high-quality GO and reduced graphene oxide (RGO) with a high level of durability, utilizing, an alternative probe that was quick, cheap, and environmentally friendly, which also used ultrasonic bath radiation. RGO1 and RGO2 were made in neutral and acidic media, respectively.57

3.2. Bottom-Up Strategies

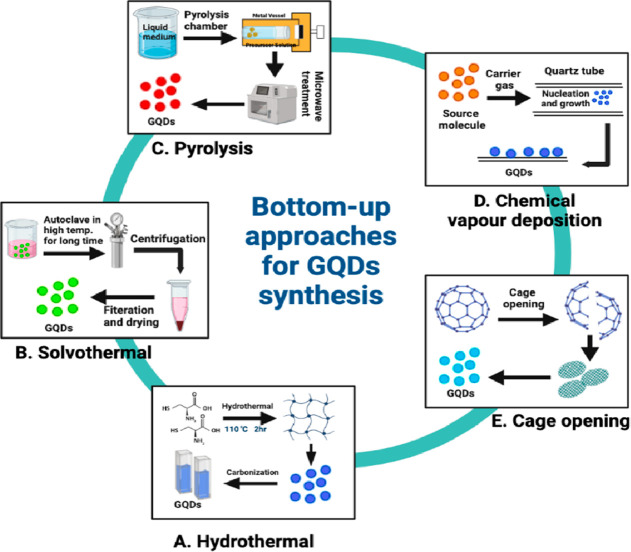

The bottom-up method employs small molecules as starting materials, which are then condensed to form a larger entity with a defined size, shape, and required properties for producing GQDs. These techniques include the controllable synthesis of Sp2 carbon from organic polymers and pyrolysis/carbonization processes that begin with organic molecules. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules (glutamic acid, glucose, and citric acid) are typically the most reliable precursors for forming high-quality GQDs. This method is suitable for modulating the size of GQDs, but it requires multiple steps and a separate purification step. The various synthesis methods reported reflect the diversity of carbon precursors used in the bottom-up synthesis (Figure 5).58,59

Figure 5.

Different bottom-up approaches for the synthesis of GQDs.

3.2.1. Hydrothermal

Hydrothermal synthesis is one of the most used methods for producing GQDs. Carbon precursors, most commonly graphene sheets, are converted into GQDs via oxidation, followed by high-temperature treatment. Compared to other synthetic processes, hydrothermal exfoliation is a more simplistic method for producing GQDs. Hydrothermal processes require water and oxidizing agents such as strong acids or alkali, which are crucial to cutting carbon sources into GQDs.60

For the first time, Pan et al. reported a novel and simple hydrothermal technique and fabricated aqueous dispersible blue luminescent GQDs by the hydrothermal exfoliation of GO sheets. The synthesis steps involved the oxidation of graphite to GO before thermal treatment, which generated epoxy functional groups. These epoxy groups acted as cleavage points and were completely broken during the hydrothermal reaction, resulting in stable carbonyl groups responsible for GQD’s water solubility.61 According to Li et al., the hydrothermal method is simple, quick, and suitable for scaling up to develop GQDs in a short time (3 min) using the microwave irradiation (MA-GQDs) method. So, this method exhibited excellent fluorescence quantum with an efficiency of up to 35. Furthermore, the MA-GQDs application for ultrabright fluorescence and stable MA-GQDs is for fluorescence probe and phosphor to prepare white light-emitting diodes in the cell imaging area. Recently published studies using this route discovered the synthesis of high-quality, RGO from GO and KOH, as well as Ag–GO nanocomposites from GO, KOH, and AgNO3 in single fast steps, both of which have antibacterial properties.62 In a study, humidity sensors have been created using nanocomposites of GQDs and silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), which were produced using a hydrothermal process.63 In another work, the rapid and precise sensing of the S2-ion accomplished by creating a biosensor using a nanocomposite of fluorescent ionic liquid and GQDs (IL-GQDs) in a single process. The surface modification of GQDs by IL is done under hydrothermal conditions.64 One-step hydrothermal preparation of blue, fluorescent nitrogen-doped GQDs for the detection of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7 cells) using citric acid and diethylamine as precursors.65

3.2.2. Solvothermal

The solvothermal procedure, which employs organic solvents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dimethylformamide (DMF), and benzene is another synthetic method that can produce GQDs. The solvent’s physicochemical nature directly impacts the final size and morphology of the product in this process. In a closed chamber, a chemical reaction occurs in solvents at temperatures greater than the solvent’s boiling temperature. This approach allows for exact control of particle size and shape distributions by altering the reaction conditions.66 Iron porphyrin (Fe-N-GQDs) is a new paramagnetic and fluorescent label synthesized that resembles GQDs in nature. The mixing of Fe, N, and C sources was used to make the Fe-N-GQD, which was then exposed to high-temperature pyrolysis before undergoing solvothermal preparation, which is basically used for structural changes in the Fe–N atoms in the graphene lattice.67 The technique was also used to create a TiO2/Sb2S3/GQDs nanocomposite to explore its antibacterial property.68

3.2.3. Carbonization/Pyrolysis

The direct heating pyrolysis of small molecules has proven to be a simple bottom-up procedure and has given the highest yield without needing any special equipment. Specifically, the small organic-based precursor molecules are heated above their melting point, causing nucleation, condensation, and the subsequent fabrication of GQDs.69,70 This is a straightforward bottom-up process for preparing GQDs with sizes ranging from 15 nm to 0.5–2.0 nm in width and thickness. On the other hand, carbonization is an environmentally friendly and simple method for producing GQDs with a uniform size distribution. However, the structure and morphology of the GQDs are uncontrollable, and the yield is lower. Zhao et al. created a simple synthetic method for GQDs by carbonizing l-glutamic acid with a heating mantle device.71 In a recent work, a fluorescent probe, d-penicillamine (DPA) functionalized GQDs were used, which were made by pyrolyzing citric acid in the presence of DPA for ractopamine quantification in aqueous and plasma samples.72 The pyrolysis method is also used with hydrothermal for the preparation of N, S-GQDs@Au-polyaniline amperometric immunosensor to detect carcinoembryonic antigen.73

3.2.4. Stepwise Organic Synthesis and Cage Opening

Stepwise organic synthesis mediated GQDs fabrication is an efficient solution chemistry method that yields uniform and well-defined GQDs. Furthermore, the low throughput and aggregation of GQDs in solution due to interactions necessitated careful consideration for industrial production. Generally, the interaction of aliphatic side chains with aromatic molecules brings graphene sheets closer, triggering GQDs aggregation.74

Remarkably, the possibility of graphene wrapping into quasi 0-D fullerene GQDs provided a novel concept for producing well-ordered GQDs from fullerene via cage opening. In their study, Kaciulis et al. state that fullerene is added to a mixture of sodium nitrate, KMnO4, and concentrated H2SO4 to fabricate GQDs as fluorescent sensors. Lu et al. used the ruthenium-catalyzed cage opening technique of C60 to generate very small GQDs. The ruthenium surface develops strong contacts with the C60 molecules, resulting in a surface vacancy on the ruthenium and aiding the C60 molecules in becoming buried in the surface. Embedded molecules are fractured as the temperature rises, producing more carbon clusters that aggregate and diffuse to create GQDs. The shape or form of the GQDs can then be fixed by adjusting the annealing temperature.75,76

3.2.5. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

CVD is widely used for creating nanoparticles with monolayer architectures and graphene sheets. This is a technique for laying down gaseous reactants on a substrate. Fan et al. created the CVD-grown GQDs first, using copper foil as a substrate and methane as a carbon source. According to the DLS analysis, the resulting GQDs had a broad size distribution (5–15 nm), whereas the height profiles (1–3 nm) suggested the formation of GQDs with a few layers. The sole difference between CVD and PVD (Physical Vapor Deposition) is that solid reactants are used instead of gaseous ones in CVD. Here, the carrier gases are combined in a reaction chamber that is kept at a specific temperature and pressure.77 Furthermore, the reaction occurs on the substrate, where the finished product, such as graphene, is deposited, and the byproducts are pumped away. The substrate is usually made of a transition metal (Ni/Cu) or ceramic-like glass. Finally, the substrate is chosen based on the graphene’s ability to be transferred to the required substance. Chemical vapor deposition is used to generate the 3D graphene, a new electrochemical process for producing high-quality GQDs from monolithic 3D graphene.78

Although the hydrothermal and ultrasound-aided methods are both quick and environmentally friendly, it is challenging to synthesize them on a large scale in industry. Before a hydrothermal reaction can take place, the raw materials must be treated with a potent oxidant. The reaction also requires high temperatures and high pressure, which might result in combustion or an explosion.33 Although H2SO4, HNO3, or other oxidants are required for the chemical oxidation process, which is now the most commonly used method, they may also result in corrosion or explosions. Even though the electrochemical oxidation process produces GQDs of uniform size, the pretreatment of raw materials and the output yield are both poor, making it challenging to carry out large-scale manufacturing.34 The microwave process involves filtering and purification, which makes it challenging to employ for large-scale manufacturing despite its quick reaction time. Although the pyrolysis process is an environmentally friendly way to produce GQDs, it is unable to regulate the size and structure of GQDs. Whereas electron beam irradiation, which is a quick and high-yield approach, it is not frequently employed since it necessitates pricey specialized equipment and poses a radiation danger to the user.79

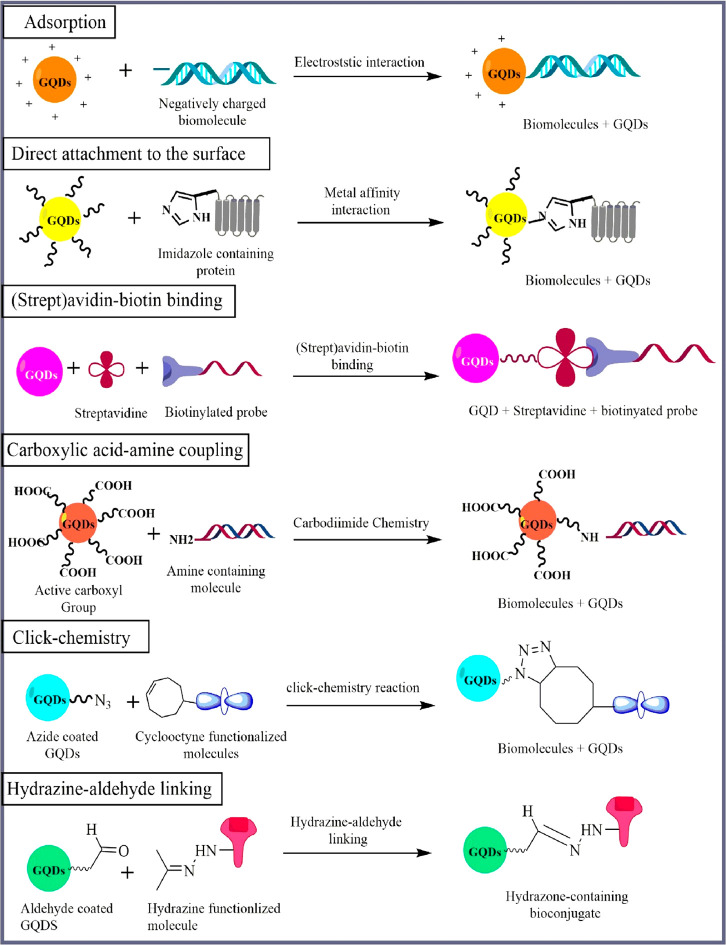

4. Surface Conjugation Chemistry

GQDs have demonstrated superior qualities in terms of chemical inertness, bioactivity, and viability, but there are still some challenges that prevent their use in bioimaging, such as relatively low luminescence quantum yields (the quantum yields of most GQDs are less than 10%), shifting fluorescence emissions, and an ambiguous luminescence process. As a result, a lot of work was done to use surface chemistry to boost the quantum yields (QY) and surface activity of GQDs (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Conjugation chemistry for attachment of GQDs with different biological moieties.

4.1. Adsorption

The water-soluble GQDs surface can absorb some biomolecules. This mechanism is nonspecific and is influenced by various factors, including the molecule’s surface charge. Passive adsorption is a systematic and accessible approach for GQDs bioconjugation. Electrostatic adsorption occurs when species with opposing charges attract each other, producing a nonspecific interaction involving the NP and the biomolecule. Negatively charged GQDs typically interact with positively charged biomolecules to form noncovalent conjugates.80 GQDs were joined to several biomolecules using this bioconjugation technique, including proteins, porphyrins, lectins, polysaccharides, and nucleic acids.81 Hydrophilic NPs can also develop electrostatic interactions alongside polar molecules through their surface coatings. In general, proteins possess a hydrophilic surface and a hydrophobic core; therefore, they must shift configuration to associate with nonpolar particles. Since these structural changes might result in protein denaturation and a reduction of biological activity, electrostatic adsorption is usually the preferred strategy. Negatively charged semiconductor materials with positively charged biomolecules are a widely adopted approach for noncovalent GQD conjugation.82 In a report, GQD@MnO2 nanocomposites were created by the adsorption of MnO2 nanosheets to the edge of GQDs in order to detect internal glutathione-related tumors (GSH).83

4.2. (Strept)avidin–Biotin Binding

Several biomolecules and particles have been conjugated using the (strept)avidin–biotin combination. This tactic relies on avidin or streptavidin’s naturally high-affinity interactions with biotin, comparable to those between receptors and ligands or enzymes and substrates. The intensity of the (strept)avidin–biotin combination benefits bioconjugation chemistry. It is robust to pH, buffer salts, temperature variations, and process adjustments such as multiple washing steps.84 One biotin-binding site is present on each of the four identical subunits that make up the glycoprotein known as avidin. A tiny molecule called biotin, also referred to as vitamin H or vitamin B7, can be added to biomolecules or particles without changing their function or nature. As biotin has a carboxylic acid, it can be covalently conjugated to many species. Biomolecules can be chemically prepared with an amine, thiol, or carboxyl-reactive biotin reagent to biotinylate them, or they can be genetically altered to have a biotin acceptor.85 Therefore, the (strept)avidin–biotin binding is one of the most substantial noncovalent interactions, approaching the strength of a covalent bond. As a result, the procedure is frequently referred to as the “covalent conjugation method”. This conjugation process is frequently adopted. Using this method, an electrochemical biosensor was developed for direct detection of miRNA-21.86 However, it has a major drawback due to the vast size of its derived component structure, which is a protein. As a result of this constraint, this approach is rarely employed rather than the carbodiimide coupling technique.87

4.3. Carboxylic Acid–Amine Coupling

As a result of the fact that no part of its chemical structure is incorporated into the final bond between conjugated molecules, this chemistry is referred to as zero-length (carboxyl to amine) cross-linking agents. EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-(Dimethylamino)propyl) Carbodiimide) combines with carboxylic acid to produce an intermediate, which then reacts with the amine to produce a conjugate containing an amide bond. EDC is frequently used in conjugation with an adjuvant, such as N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) or sulfo-NHS (an NHS water-soluble molecule), among the water-soluble carbodiimides. When the oxygen in the carboxylic acid combines with the carbodiimide, a very reactive intermediate is formed that can combine with amines to form an amide bond.88,89 When NHS is added, a secondary, more soluble, and more robust intermediate form then interacts with the amine to form the final product. Water-soluble carbodiimides are preferred for GQD conjugation because they enable the reaction to proceed in aqueous buffer solutions.90 Hou et al. used EDC-NHS for surface incubating GQDs to design an ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence biosensor for specific detection of miRNA.91 Guitao et al. in 2019 developed a novel graphene QDs ECL biosensor using EDC-NHS to detect circulating DNA by a cycle amplification method.92 Kong et al. use graphene films on gold substrates, as working electrodes for electrochemical detection of nucleic acid (microRNA) miR-155 as a biomarker for the diagnosis of various diseases. They used EDC and NHS as coupling agents for the self-assembly monolayer (SAM)-modified gold substrate.93 The conjugation is also used to create cytometric-based nanobiosensing systems that directly quantify cell-free circulating (ccf) epigenomic signatures like methylated ccf-DNA, trimethylated histone H3 at lysine, and protein-bound argonaute 2 ccf-miRNAs.94

4.4. Click-Chemistry

The cycloaddition of azides and alkynes is a bio-orthogonal technique often utilized for GQD bioconjugation. The Huisgen cycloaddition, also known as the azide-terminal alkyne reaction, begins with a five-membered ring of triazole, a heterocyclic molecule containing three nitrogen atoms. Initially, this reaction was performed at maximum temperatures to enhance its yield. Some years later, it was established that this cycloaddition could be catalyzed by CuI and generate high yields of the heterocycle ring even at RT. For this reason, the CuI-catalyzed cycloaddition of azides and terminal alkynes was termed a “click-chemistry reaction”. Proteins, viruses, antibodies, and miRNAs have been coupled to QDs coated with azides or alkynes and suitably functionalized.95 Thiol–ene click reactions in a single step when compared to the conventional synthesis of GQDs. A unique technique for making GQDs from GO was applied, and it proved to be both inexpensive and effective with exceptional qualities, including their homogeneous nano size, robust green fluorescence, consistent stabilities, and great bioactivity.96

4.5. Hydrazine-Aldehyde Chemistry

The bioconjugation method involving the interaction of hydrazine derivatives with aldehydes or ketones is appealing from a biorthogonal perspective. Hydrazine derivatives respond quickly, particularly with aldehyde or ketone functional groups, making a hydrazone bond that is a sort of Schiff base.97 However, this reaction is faster with aldehydes than with ketones; the hydrazone bonds formed with ketones are steadier than those formed with aldehydes. Aldehyde-reactive chemical groups like hydrazides and alkoxyamines are frequently utilized in biomolecular probes to label and cross-link carbonyls (oxidized carbohydrates) on glycoproteins and other polysaccharides. At pH 5 to 7, hydrazides and aldehydes produced by periodate-oxidation of sugars in biological samples interact to form hydrazone bonds.98 The majority of protein-labeling applications can be completed using the hydrazone bond. The main advantage of this strategy is that biological systems mainly do not have the aldehyde and hydrazine groups. However, the biological system may consist of amines that react with aldehydes. The hydrazine–aldehyde coupling has been used to conjugate QDs to antibodies, synthetic peptides, and viruses. This approach can also be applied to oxime derivatives instead of hydrazines.99

4.6. π–π Interaction

The planar graphitic domain’s extensive sp2 hybridization creates the possibility for functionalization in the absence of oxygen functionality or hydrogen bonds using π–π stacking or van der Waals forces. Unsaturated (poly)cyclic molecules establish a specific type of dispersion force from van der Waals forces known as the π–π interaction. Since graphene contains a hexaatomic ring of carbon atoms, it can spontaneously stack on aromatic biomolecules. Along with the hydrogen bonds between pairs of complementary nucleotides, these interactions significantly contribute to stabilizing DNA’s double helical structure.100 In addition to having less of an adverse effect on the structure of graphene materials, noncovalent functionalization based on the hydrophobic attraction, interaction, or van der Waals force between graphene materials and stabilizers also makes it possible to tailor their solubility and electronic properties. As an illustration, Green and colleagues investigated several functionalized pyrene derivatives and showed that these species could maintain single- and few-layered solvent-exfoliated graphene flakes in aqueous dispersions.101 Recent research has shown that small peptides assemble toward the planar surfaces or edges of GO through π–π interactions. Immobilized peptide-based GO materials have much promise for creating susceptible and versatile detection platforms. A non-single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecule was used as a biorecognition molecule in the first GO-based sensing mechanism study.102 According to a study, graphene-based nanostructures can interact with ssDNA molecules through π–π stacking interactions because they contain π-rich conjugation domains.103 Rafiei et al. created a GQDs-DNA nano assembly as a biosensor by using stacking to interact with ssDNA.104 Yew et al. also used GQDs for DNA detection, using a FAM-L probe that adsorbs onto the GQDs upon incubation via π–π stacking interactions.105

5. Circulating Cell-Free Nucleic Acids (ccf-NAs) Detection Using GQDs

Circulating nucleic acid (CNAs) includes various forms of nucleic acid like DNA, RNA, micro RNA, lncRNA, and mitochondrial DNA in plasma and serum. CNAs are released as nucleosomes when cells undergo apoptosis or necrosis. Apart from that, CNAs could be produced by the active metabolic release of DNA from cells.106 CNAs can be found in healthy and diseased bodies, with diseased ones having higher levels. Increased levels of circulating nucleic acids in the blood can signal some malignant and benign disorders. Although protein biomarkers have been identified, CNAs may be a better biomarker since they are more relevant, precise, and accurate than protein biomarkers.107 Their dysregulation is generally observed in tumors, which can be used as a diagnostic for malignancy. As a result, circulating nucleic acids are developing into a valuable resource for studying several chronic diseases, including cancer, and acting as biomarkers.108

The various CNAs types being examined include ccf-DNAs, ccf-RNAs, ccf-mtDNAs, ccf-miRNAs,109 ccf-lncRNAs, etc.110 The use of ccf-DNAs in clinical practice for a few diseases has already been made possible by developing newer technologies to isolate minute quantities of ccf-NAs and detect the unique signatures on these. It is crucial to determine the function of these ccf-NAs as epigenetic biomarkers in clinical settings because they are linked to various epigenetic modifications that exhibit disease-related variations.111 The field of noninvasive molecular diagnosis has undergone a revolution, with conventional screening and treatment techniques being replaced by epigenetic markers. The epigenetic markers for these ccf-NAs reflect the pattern unique to the tissue that produced them. Therefore, epigenetic biomarkers can aid in diagnosing a variety of diseases even before the appearance of actual symptoms, which will aid in better disease management.112 Numerous studies are being conducted to determine whether certain clinical condition-specific epigenetic marks exist on ccf-NAs. Despite the advancement of techniques for examining epigenetic changes, the application of epigenetic biomarkers discovered on ccf-NAs is limited due to their lower blood circulation levels. The detection and quantification of ccf-NAs, viz., RNA, fetal DNA, fetal RNA, mtDNA, mitochondrial RNA, and miRNA levels, in body fluids are of clinical importance. These ccf-NAs may serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of several diseases. Because of this, ccf-NAs are important in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of many diseases. Though the clinical utility of ccf-NAs is being widely recognized, in-depth characterization is warranted to ensure usage in point-of-care settings.113,114

ccf-NAs are well-known biomarkers used in prenatal diagnosis to screen for genetic abnormalities in fetuses. ccf-NAs (ccf-DNAs and cell-free noncoding RNAs) may be promising biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer, cardiovascular and neurological illnesses, and diabetes, according to growing data. Cell-free circulating tumor DNA, circulating tumor RNA, circulating tumor cells, and exosomes are all significant tumor carriers of genetic data in the blood. Because of its stability and ease of access, ccf-DNAs are an appealing alternative as a diagnostic, predictive, and prognostic biomarker for analyzing tumor genetic information utilizing GQDs (Table 1).115 Plasma ccf-DNAs levels have been linked to tumor size, invasion, cancer stage, survival, and treatment-related disease progression. Above all, microRNAs (also known as miRNAs or miRs) have drawn more attention because of their extensive involvement in regulating cellular processes. These quick 20–22-mer RNA sequences play a key role in the post-transcriptional precise control of several physiological cell functions, such as cell division, proliferation, and signaling.116

Table 1. Recent Advances in GQDs along with Method of Preparation and Conjugation Chemistry for the Detection of Circulating Cell-Free Nucleic Acids Using Different Analytical Methodsa.

| Sample No. | GQDs used | Source and synthesis | Conjugation chemistry | Biomolecule (analyte) | Study | Inference | Analytical method | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Ag/GQDs | - | - | Methylated DNA | Plasma | Ag/GQDs nano ink with strong electrical conductivity was employed to make a novel DNA nanosensor that precisely detects methylated DNA. | DNA genosensor | (135) |

| 2. | GQD/GO/AuNPs | - | - | miRNA-21, miRNA-155, miRNA-210 | Serum | GQD/GO/AuNPs biosensor designed for detection of miRNA-21, miRNA-155, and miRNA-210 with LODs of 0.04, 0.33, and 0.28 fM, respectively. | Electrochemical biosensor | (136) |

| 3. | GQDs | Solvothermal method | Carbodiimide coupling | miRNA-21 | MCF-7 cell line and serum | GQDs were synthesized using a solvothermal technique and coupled with carbodiimide chemistry to detect miRNA-21 at a LOD of 0.5 pM in breast cancer patients. | Ratiometric Fluorescent biosensor (FRET assay) | (137) |

| 4. | Ag/Au core–shell nanoparticles electrodeposited GQDs | Citric acid by Bottom-up approach (Pyrolysis) | - | miRNA-21 | Plasma | Ag/Au core–shell GQDs are fabricated using the pyrolysis method and are used for the early detection of cancer by detecting miRNA-21. | Electrochemical biosensor | (138) |

| 5. | GQDs | Graphene sheet | π–π stacking | miRNA-29a | - | The adsorption mechanism of miRNA on GQDs in solution is revealed using molecular dynamics simulations. The GQD model shows the speedy adsorption of miR-29a onto its surface for detection. | Molecular Dynamics Simulation | (139) |

| 6. | r-GQD@HTAB | - | - | Cell free Fetal DNA | Blood | Fluorescence GQDs are designed to detect the target DNA selectively with a detection limit of 0.082 nM. | Fluorescence biosensor | (140) |

| 7. | GCQDs | Carbon fibers + H2SO4 + HNO3 by Ultrasonication | π–π stacking | miRNA-21 | Plasma | Ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescence GCQD synthesized by ultrasonication technique and π–π interaction coupling for specific detection of miRNA-21. | Electrochemiluminescence biosensor | (91) |

| 8. | GQDs | By oxidized Graphene sheets + conc. Sulfuric acid + Nitric acid | π–π stacking | Methylated DNA | - | In this study, it was found that the interaction of GQDs could bind to DNA fragments and lead to different fluorescence patterns. Due to their differing interaction mechanisms, a comparison of these two effects may enable us to discriminate between DNA that has been methylated and unmethylated. | Fluorescence biosensor | (104) |

| 9. | GOQDs | Graphene oxide | - | miRNA-21 | Serum | CL detection technology using GOQDs constructed to achieve highly sensitive and selective detection of microRNA-21. It shows the detection limit is 1.7 fM. | Chemiluminescence biosensor | (141) |

| 10. | GQDs | Citric acid By Pyrolysis | EDC-NHS | DNA | Serum | ECLGQDs are prepared by the pyrolysis method, designed for target DNA detection by a cycling amplification strategy with a detection limit of 0.1 pM. | Electrochemiluminescence biosensor | (92) |

| 11. | GQDs | - | - | miRNA-141 | - | A universal donor/acceptor-induced ratiometric PEC paper analytical device with HDHC is suggested for the biosensing of miRNA-141 using an integrated photoanode (GQD) and photocathode. | Photoelectrochemical (PEC) technique | (142) |

| 12. | GQDs | Citric acid By One-step Hydrothermal method | EDC-NHS | miRNA-541 | Plasma | Using the hydrothermal method GQDs were prepared. This label-free DNA assay was developed to detect microRNA-541. The results were analyzed using differential pulse voltammetry. | Electrochemical genosensor | (143) |

| 13. | GQDs | Citric acid By Pyrolysis | EDC-NHS | Mutant DNA | Serum | For the detection of mutant DNA, ultrasensitive enzyme-free signal amplification is used with a detection limit of 0.8 pM. | Resonance light scattering method | (144) |

| 14. | PEHA and Histidine functionalized GQDs | Citric acid by pyrolysis | Carbodiimide coupling | miRNA-141 | Serum | The PEHA-GQD-His was used for the fabrication of fluorescence. Its fluorescence linearly reduces with increasing microRNA-141 concentration, with the detection limit of 4.3 × 10–19 M. | Fluorescence biosensor | (145) |

| 15. | AuNF-GQDs | l-Glutamic acid by Bottom-up method | EDC-NHS | miRNA-34a | H9C2 cell line | The designed AuNF-GQDs biosensor detects miRNA-34a in vitro and in vivo. FRET occurred due to spectral overlap between the emission band of GQDs-ssDNA and the absorption band of AuNF-ssDNA | FRET | (146) |

| 16. | Amino-functionalized GQDs | Direct pyrolysis of Citric acid | - | miRNA-25 | Plasma | The electrochemical genosensor is fabricated for microRNA-25 detection based on the electrochemical response of PBP as an electroactive label. | Electrochemical genosensor | (147) |

| 17. | GQDs | Calcined petroleum coke + Concentrated sulfuric acid + Nitric acid | π–π stacking | DNA | - | Coke-derived GQDs were developed for DNA detection. GQDs functioned as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) acceptors for DNA detection down to 0.004 nM. | Fluorescence biosensor | (105) |

| 18. | B-GQDs | Electrolytic exfoliation of Boron-doped graphene rods | EDC-NHS | miRNA-20a | Boron-doped GQDss (B-GQDs) with an atomic percentage of boron of 0.67–2.26% were synthesized by electrolytic exfoliation of B-doped graphene rods to detect target miRNA-20a. The detection limit reached is 0.1 pM. | Electrochemiluminescence | (148) | |

| 19. | GQD-PEG-P | Graphite oxide | Carbodiimide coupling | miRNA-155 | MCF-7 cell line | The proposed GQD-PEG-P was efficient in differentiating cancer cells from other cells by the use of blue fluorescence GQDs for the detection of miRNAs. | Fluorescence biosensor | (149) |

| 20. | GQDs | Graphite by Hydrothermal method | π–π stacking | miRNA | - | A sensor for the detection of specific miRNA sequences was developed, which was based on GQDs and UCNP@SiO2-ssDNA. By relative emission measurements compared to a reference, it was possible to determine the presence of complementary miRNA target sequences. | Fluorescence sensor | (150) |

| 21. | Graphene aerogel/gold nanostar | Graphite | - | Circulating cell-free DNA | Serum | For the detection of circulating DNA, a GQDs electrochemical biosensor was devised from graphite with a detection limit of 3.9 × 10–22 g mL. | Electrochemical biosensor | (151) |

| 22. | Graphene oxide | Graphite Powder | EDC-NHS | miRNA-155 | - | The electrochemical sensor was developed using conformational changes in biomolecular receptors for miR-155 detection with detection limits of 5.2 pM. | Electrochemical biosensor | (93) |

| 23. | Graphene oxide | - | - | miRNA-155 | Plasma | For the detection of circulating miR-155. With a detection limit of 0.6 fM, indicating that the nano biosensor had great selectivity. | Electrochemical nanobiosensor | (152) |

| 24. | GQDs/PTCA-NH2 | By refluxing Graphene Oxide | π–π stacking | miRNA-155 | Cell lines (HeLa and HK-2) | GQDs are produced by refluxing graphene oxide and linked using π–π stacking. With further immobilization of the target miRNA, a noticeable decrease in the ECL signal was observed. | Electrochemiluminescence biosensor | (153) |

| 25. | GQDs | - | EDC-NHS | miRNA-155 | Serum | These GQDs biosensors were modified by HRP and can effectively catalyze the oxidation reaction of 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine mediated by H2O2. Due to GQDs and enzyme catalysis, the biosensor can sensitively detect miRNA-155 between 1 fM to 100 pM. | Electrochemical biosensor | (133) |

| 26. | GQDs | Citric acid by Bottom-up method (pyrolysis) | π–π stacking | miRNA-155 | Pyrene and fluorescent dye dual labeled MBs were employed to make GQDs via π–π interactions, triggering FRET and generating fluorescent intensity changes as signals for target miRNA detection with a LOD of 0.1 nM to 200 nM. | Fluorescence biosensor | (154) | |

| 27. | Nanoscale graphene oxide | Graphene Oxide By Ultrasonication | - | miRNA-10a/b | Cell lines (4T1 and MCF-7) | To detect miRNA, a fluorescence-based device was developed. The fluorescence of the probe strands labeled with a molecular fluorescent dye is completely quenched by the graphene oxide surface but is regained with target molecules by hybridization. Thus, specific detection of miRNA was performed. | Fluorescence | (155) |

| 28. | Nanoscale graphene Oxide | Graphene Oxide | - | miRNA-21 | Serum | A biosensor designed using GO for the detection of miRNAs. In the presence of the target miRNA, surface-adsorbed fluorophore-labeled nucleic acids can be desorbed from the nGO surface, recovering their fluorescence and enabling the precise identification of circulating oncomiR. | Fluorescence biosensor | (156) |

| miRNA-141 | ||||||||

| 29. | GQDs | Graphite powder + H2S4 + HNO3by Oxidation | π–π interactions | DNA | - | Using rGQDs and GO as fluorescent sensing platforms, a sensitive sensing system for quantitative DNA analysis can be constructed. | Fluorescence biosensor (FRET) | (157) |

| 30. | Reduced Graphene oxide | Graphene oxide By Sonication | EDC-NHS | miRNA-141 miRNA-29b-1 | - | Using reduced graphene oxide, an electrochemical immunosensor for miRNA detection was produced. An electrochemical ELISA-like amplification step was performed after the DNA hybrids were introduced. As a result, with a detection limit in the fM range. | Electrochemical immunosensor | (158) |

| 31. | Graphene nanosheet | Graphene | Streptavidin–Biotin | miRNA-21 | - | An electrochemical biosensor for sensitive detection of miRNA-21 was designed, and the synthesized complex DNA–AuNPs–LNA hybridizes with target miRNA. The electrochemical method was used for detection with a detection limit of 0.06 pM. | Electrochemical biosensor | (86) |

| 32. | GQDs | Graphene | EDC-NHS | lncRNA | Plasma | GQDs are used for the detection of target lncRNAs by sequence-specific biotinylated oligonucleotide probes conjugated to streptavidin-labeled GQDs. | Fluorescence | (159) |

Ag/GQD: Silver-graphene quantum dots, AuNPs: Gold Nanoparticles, GCQD: Graphene Carbon Quantum Dot, B-GQDs: Boron doped Graphene Quantum Dots, GOQDs: Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots, GQD-PEG-P: Graphene Quantum Dots - Polyethylene Glycol - Porphyrin, MWCNTs: Multiwalled carbon nanotubes, r-GQD@HTAB: reduced graphene quantum dots modified with hexadecyl trimethylammonium bromide, PBP: p Biphenol, py-MBs: pyrene-functionalized molecular beacon probes.

Only a percentage of tumor-derived DNA with diagnostically important mutations is present in ccf-DNAs, which is fragmented to an average length of 140 to 170 bp and expressed in low quantities per milliliter of peripheral blood. Several strategies have been introduced to detect low-level tumor-associated mutations in cancer patients’ ccf-DNAs.117 Finally, the small size of GQDs and properties like quantum confinement and edge effect are vital benefits for the further development of this diagnostic technique, given that one of the most desirable fields of application is their use as fluorescent tags and success in sensor research. Their great sensitivities and effectiveness, particularly when paired with additional methods like electrical and optical methods, make GQDs an effective tool in bioanalysis and the detection of biological targets.118

6. Biosensing Techniques for the Detection of ccfNAs

Due to their remarkable physical and chemical characteristics, GQDs, the next generation of the graphene family, have been demonstrated to be the best sensing components for detecting circulating nucleic acids. These GQDs with various biomolecules can use optical, electrochemical, and chemiluminescent biosensors to selectively recognize and transform into a signal-specific ccf-NAs biomarker.119 Numerous studies have been conducted to ascertain how to alter electrode surfaces with nanosized materials with sizes between 1 and 100 nm, derived from organic or inorganic sources, to provide biosensors with increased reproducibility, selectivity, and sensitivity. Given their large surface-to-volume percentage and large specific surface area, nanomaterials have high adsorption of target analytes. Utilizing neodymium-doped BiOBr nanosheets (Nd-BiOBr) as a photoactive substrate, a photoelectrochemical bioassay for dopamine-loaded liposome-encoded magnetic beads is being developed to measure the amount of DNA associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV).120 Another recent study used CRISPR-Cas12a trans-cleaving the G-quadruplex for biorecognition/amplification and a hollow In2O3–In2S3-modified screen-printed electrode (In2O3–In2S3/SPE) as the photoactive material to identify the human papillomavirus-16 (HPV-16) on a foldable electrochemical detector.121 GQDs, the new class of fluorescent materials from the carbon nanomaterials family, possess ideal chemical and physical properties to be used and integrated into sensors for biological and medical applications.

The optical characteristics of GQDs can be used in biosensing; this application uses the PL of GQDs and generally requires photon detection.122 GQDs, serve the purpose of detecting and indicating the presence of nucleic acid biomarkers in biosensing systems.123 GQD-based biosensors utilize the affinity between specific functional groups within GQDs and the analyte biomolecule. When a functional group conjugated onto the GQDs binds to the analyte, the association between the pair can provide different electronic states. A change in PL intensity can be used to measure the detection of an analyte by changing the electronic structure of the GQDs.124

6.1. Absorbance

The π–π* shift of the CC bonds in GQDs makes them a popular choice for photon capturing in the shorter wavelength range. They exhibit more excellent optical absorption in the UV range of 260 to 320 nm, with a tip that continues into the visible spectrum. As a result, they become more effective at absorbing long wavelengths. Apart from that, these GQDs have a broad peak around 270 and 390 nm, indicating that they are involved in the n−π* transition of the CO bonds.125

6.2. Optical

Since these characteristics are linked to the band gap of GQDs, the optical characteristics of GQDs are conceptually dependent on inherent variables like size, layer, shape, or edge orientation. Due to the −* transition of CC bonds, GQDs exhibit high optical absorption in the UV region at 230 nm. Additionally, a shoulder peak across the range of 270–390 nm caused by the n–* transition of C–O bonds was seen.126 The strong optical features of GQDs with distinct identification or dual emissions are susceptible to being embellished with additional distinct molecules. GQDs are superior PL sensors for detecting interesting analytes as compared to conventional organic dyes and semiconductor QDs probes because they offer great sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and security for biosensing systems.127

6.2.1. Photoluminescence

The GQDs exhibit more QY than the bare CDs. This is because of the structure’s layering and the suitable crystalline property. The optical character of GQDs with a luminescence mechanism is also a challenge. The potent fluorescent GQDs, along with their layered structure, are used for confocal imaging of cancer cells with the help of different solvents. They showed well-designed PL emission of the GQDs in distinct liquid solutions, i.e., solvents, stating the strong PL emission of the GQDs due to various edge locations and functional groups linked to the GQDs.128 GQDs have a single-layer carbon core with chemical groups on the surface or edge. It has oxygen-based functional groups on the basal plane or at the edges. The states of the sp2 sites determine the fluorescent property. The fluorescence can be triggered by recombining electron–hole pairs in such sp2 clusters.129 The bandgaps of different sizes of sp2 cover a wide range in GO due to the vast size distribution of sp2 domains, resulting in a broad PL emission spectrum from visible to near-infrared. GQDs possess more defects, oxygen groups, and functional groups on the surface. The excitons in graphene have an infinite Bohr diameter. As a result, quantum confinement effects will be observed in graphene fragments of any size. As a result, GQDs have a nonzero bandgap and PL on excitation.130

6.3. Electrochemical

The working, counter, and standard electrodes are all included in an electrochemical biosensor. On the edge of the operating electrode, a chemical reaction occurs between the immobilized biomolecules and the relevant analyte, producing or consuming ions or electrons.131 These ions or electrons produce a voltage at the reference electrode and provide a signal that may be measured. The real-time, quick, sensitive, specific, and accurate detection and quantification of biomarkers at extremely low cutoff values for early diagnosis have been significantly improved by the combination of nanoparticles with electrochemical biosensing.132 In their research, they created an easy and sensitive electrochemical biosensor built on enzyme action using GQDs as a novel platform for immobilization for the efficient detection of miRNA-155.133

7. Drawbacks of GQDs

Even with numerous advantages, there are some limitations to GQD uses, such as low yield and higher dispensability. Other drawbacks related to the method of preparation, like in the top-down approach, include the need for expensive equipment, setups, and materials. The situations are also critical and take longer than usual to rectify. The pathway for their preparation brings numerous drawbacks by using graphene, their oxide, and carbon fibers in the minor pieces as they are sometimes toxic. The other scheme has drawbacks like potent safety risks, environmental pollution, premium costs, and brutal methods for fabrication and after-processing methods. So, finding a method that favors the environment and should be eco-friendly while also originating from original greener precursors is challenging in this area. The main obstacle to using GQDs for the creation of sensing devices is the large-scale synthesis of high-quality and stable nanoparticles due to their specific size, shape, and charges, as these characteristics have a significant impact on the physicochemical properties of these nanomaterials and, consequently, on the performance of GQD-based sensors.134

8. Conclusion

Of late, significant and rapid advancements in nanophotonics for prognosis and early diagnosis of various noncommunicable diseases and age-associated degenerative illnesses are of current interest. Semiconductor nanocrystals have provided an innovative milieu for qualitative and quantitative analyses of multiple analytes in the peripheral circulation. In this respect, QDs demonstrate significant potential in biomedical, bioimaging, photoluminescent, and fluorescent-based applications. GQDs have received considerable attention due to their unique properties, such as excellent solubility, robust chemical inertness, large specific surface area, superabundant surface conjugation sites, superior photostability, resistance to photobleaching, and nonblinking. In addition, their optical characteristics can be adjusted via size tunability, chemical doping, and surface functionalization for featured and specific applications. In this review, we have sought to showcase a comprehensive picture of the most recent advances in research, focusing on their biosensing applications. Following an in-depth discussion on the potential in vitro and in vivo bioimaging applications of GQDs, current progress in fabrication methodologies, including top-down and bottom-up, has been critically examined. In addition to these features, the review goes through the various surface conjugation approaches. In recent times, numerous reports have demonstrated that GQDs are developing into critical functional nanomaterials with applications in the medical, optoelectronic, and energy-related fields. However, the principle in several GQDs systems is currently unexplained, necessitating further research. The zero-dimensional GQDs showed great promise among the various nanosized substrates for detecting CNA biomarkers because of their exceptional electronic and optical properties, large surface area, and various active sites for chemical functionalization. GQDs can offer sophisticated sensing substrates for quick and accurate diagnosis at the point of care and the monitoring of therapeutic progress thanks to their capacity to create covalent connections with proteins that can identify numerous nucleic acid biomarkers for several chronic ailments, including cancer. Detection of ccf-NAs, DNAs, mtDNAs, mRNAs, miRNAs, or lncRNAs can help identify multiple cancers at the early stage. Often, these liquid biopsy methods utilize a state-of-the-art technology platform that facilitates the identification of ccf-NAs in peripheral circulation and localizes the tissue of origin. In this regard, GQDs facilitate real-time quantification of these molecules by conjugating the reporter to target entities, followed by detection by fluorescence excitation and acquisition of emission. Due to the inherent ability, GQDs-based conjugation strategies have helped enhance excitation and efficiently captured the photoemission in the presence of various noise signals. By engineering the spectral overlap, multiplexing strategies can be rationally designed to identify different target sequences of cell-free circulating nucleic acids in any test sample. With the prominent rise of liquid biopsy-based approaches, GQDs-based methods of detection might be a step toward early diagnosis, prognosis, treatment monitoring, and outcome prediction of various noncommunicable diseases, including cancers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the India Cancer Research Consortium (ICRC Task Force Project ID:5/13/1/PKM/ICRC/2020/NCD-III), Department of Health Research (DHR), Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India, New Delhi for project funding support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ccfDNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Deoxyribonucleic Acids

- ccfLncRNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Long Noncoding Ribonucleic Acids

- ccfmiRNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Micro Ribonucleic Acids

- ccfmtDNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic Acids

- ccfNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Nucleic Acids

- ccfRNAs

Circulating Cell-Free Ribonucleic Acids

- CdS

Cadmium Sulfide

- CdSe

Cadmium Selenide

- CdTe

Cadmium Telluride

- CuI

Copper Iodide

- CVD

Chemical Vapor Deposition

- ECL

Electrochemical Luminescence

- EDC

1-Ethyl-3-(3-(Dimethylamino)propyl) Carbodiimide

- FRET

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer

- GO

Graphene Oxide

- GQDs

Graphene Quantum Dots

- NHS

N-Hydroxysuccinimide

- PEHA

Pentaethylenehexamine

- PL

Photoluminescence

- QDs

Quantum Dots

- QY

Quantum Yield

- ssDNAs

Single-Stranded Deoxyribonucleic Acids

- UCNPs

Upconverting Nanoparticles

Author Contributions

# P.R., B.J., and R.K. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Shu J.; Tang D. Current advances in quantum-dots-based photoelectrochemical immunoassays. Chem.: Asian J. 2017, 12, 2780–9. 10.1002/asia.201701229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z.; Shu J.; Tang D. Bioresponsive release system for visual fluorescence detection of carcinoembryonic antigen from mesoporous silica nanocontainers mediated optical color on quantum dot-enzyme-impregnated paper. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 5152–60. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Lv S.; Lin Z.; Tang D. CdS: Mn quantum dot-functionalized g-C3N4 nanohybrids as signal-generation tags for photoelectrochemical immunoassay of prostate specific antigen coupling DNAzyme concatamer with enzymatic biocatalytic precipitation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 95, 34–40. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Zhou Q.; Tang D.; Niessner R.; Yang H.; Knopp D. Silver nanolabels-assisted ion-exchange reaction with CdTe quantum dots mediated exciton trapping for signal-on photoelectrochemical immunoassay of mycotoxins. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 7858–66. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b02124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z.; Shu J.; He Y.; Lin Z.; Zhang K.; Lv S.; Tang D. CdTe/CdSe quantum dot-based fluorescent aptasensor with hemin/G-quadruplex DNzyme for sensitive detection of lysozyme using rolling circle amplification and strand hybridization. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 18–24. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z.; Lv S.; Zhang K.; Tang D. Optical transformation of a CdTe quantum dot-based paper sensor for a visual fluorescence immunoassay induced by dissolved silver ions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 826–33. 10.1039/C6TB03042D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai G.; Yu Z.; Tong P.; Tang D. Ti 3 C 2 MXene quantum dot-encapsulated liposomes for photothermal immunoassays using a portable near-infrared imaging camera on a smartphone. Nanoscale. 2019, 11, 15659–67. 10.1039/C9NR05797H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zare H.; Ghalkhani M.; Akhavan O.; Taghavinia N.; Marandi M. Highly sensitive selective sensing of nickel ions using repeatable fluorescence quenching-emerging of the CdTe quantum dots. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 95, 532–8. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2017.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Huang L.; Chen J.; Tang Y.; Xia B.; Tang D. Full-spectrum responsive photoelectrochemical immunoassay based on β-In2S3@ carbon dot nanoflowers. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 332, 135473. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.135473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Zhou Q.; Tang D.; Niessner R.; Knopp D. Signal-on photoelectrochemical immunoassay for aflatoxin B1 based on enzymatic product-etching MnO2 nanosheets for dissociation of carbon dots. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 5637–45. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D.; Lin Y.; Zhou Q. Carbon dots prepared from Litchi chinensis and modified with manganese dioxide nanosheets for use in a competitive fluorometric immunoassay for aflatoxin B1. Microchim. Acta. 2018, 185, 1–9. 10.1007/s00604-018-3012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv S.; Li Y.; Zhang K.; Lin Z.; Tang D. Carbon dots/g-C3N4 nanoheterostructures-based signal-generation tags for photoelectrochemical immunoassay of cancer biomarkers coupling with copper nanoclusters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 38336–43. 10.1021/acsami.7b13272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wang W.; Gong H.; Xu J.; Yu Z.; Wei Q.; Tang D. Graphene-coated copper-doped ZnO quantum dots for sensitive photoelectrochemical bioanalysis of thrombin triggered by DNA nanoflowers. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 6818–24. 10.1039/D1TB01465J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadnia M. S.; Naghian E.; Ghalkhani M.; Nosratzehi F.; Adib K.; Zahedi M. M.; Nasrabadi M. R.; Ahmadi F. Fabrication of a new electrochemical sensor based on screen-printed carbon electrode/amine-functionalized graphene oxide-Cu nanoparticles for Rohypnol direct determination in drink sample. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 880, 114764. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.114764. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buledi J. J.; Solangi A. R.; Hyder A.; Batool M.; Mahar N.; Mallah A.; Karimi-Maleh H.; Karaman O.; Karaman C.; Ghalkhani M. Fabrication of sensor based on polyvinyl alcohol functionalized tungsten oxide/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for electrochemical monitoring of 4-aminophenol. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113372. 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goryacheva O.; Vostrikova A.; Kokorina A.; Mordovina E.; Tsyupka D.; Bakal A.; Markin A.; Shandilya R.; Mishra P.; Beloglazova N. Luminescent carbon nanostructures for microRNA detection. Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 119, 115613. 10.1016/j.trac.2019.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A. N. Graphene and its derivatives as biomedical materials: Future prospects and challenges. Interface focus. 2018, 8, 20170056. 10.1098/rsfs.2017.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derakhshi M.; Daemi S.; Shahini P.; Habibzadeh A.; Mostafavi E.; Ashkarran A. A. Two-dimensional nanomaterials beyond graphene for biomedical applications. J.f Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 27. 10.3390/jfb13010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano S.; Yáñez-Sedeño P.; Pingarrón J. M. Carbon dots and graphene quantum dots in electrochemical biosensing. Nanomaterials. 2019, 9, 634. 10.3390/nano9040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K.; Zhao X.; Wei G.; Su Z. Recent advances in the cancer bioimaging with graphene quantum dots. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 2876–2893. 10.2174/0929867324666170223154145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffarkhah A.; Hosseini E.; Kamkar M.; Sehat A. A.; Dordanihaghighi S.; Allahbakhsh A.; van der Kuur C.; Arjmand M. Synthesis, applications, and prospects of graphene quantum dots: a comprehensive review. Small 2022, 18, 2102683. 10.1002/smll.202102683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.; Gong J.; Chen J.; Zeng Z.; Huang W.; Pu K.; Liu J.; Chen P. Recent advances on graphene quantum dots: from chemistry and physics to applications. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1808283. 10.1002/adma.201808283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian P.; Tang L.; Teng K.; Lau S. Graphene quantum dots from chemistry to applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2018, 10, 221–258. 10.1016/j.mtchem.2018.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra P. K.; Shandilya R. Nanophotonic biosensors as point-of-care tools for preventive health interventions. Nanomedicine. 2020, 15, 1541–1544. 10.2217/nnm-2020-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Chen T.; Gooding J. J.; Liu J. Review of carbon and graphene quantum dots for sensing. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 1732–48. 10.1021/acssensors.9b00514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzino C. A.; Sgobbi L. F.; Marciano F. R.; Lobo A. O. Graphene-based sensors: applications in electrochemical (Bio) sensing. Handb. Graphene. 2019, 6, 349–369. 10.1002/9781119468455.ch97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haque E.; Kim J.; Malgras V.; Reddy K. R.; Ward A. C.; You J.; Bando Y.; Hossain M. S. A.; Yamauchi Y. Recent advances in graphene quantum dots: synthesis, properties, and applications. Small Methods 2018, 2, 1800050. 10.1002/smtd.201800050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S.; Revia R. A.; Zhang M. Graphene quantum dots and their applications in bioimaging, biosensing, and therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 1904362. 10.1002/adma.201904362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannazzo D.; Espro C.; Celesti C.; Ferlazzo A.; Neri G. Smart biosensors for cancer diagnosis based on graphene quantum dots. Cancers. 2021, 13, 3194. 10.3390/cancers13133194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. Y.; Shen W.; Gao Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 362–381. 10.1039/C4CS00269E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Ren X.; Sun M.; Liu H.; Xia L. Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Nanomaterials. 2021, 11, 3419. 10.3390/nano11123419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Shu H.; Niu X.; Wang J. Electronic and Optical Properties of Edge-Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots and the Underlying Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 24950–24957. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b05935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shabbir H.; Tokarski T.; Ungor D.; Wojnicki M. Eco Friendly Synthesis of Carbon Dot by Hydrothermal Method for Metal Ions Salt Identification. Materials 2021, 14, 7604. 10.3390/ma14247604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri A.; Debnath D.; Dharmadhikari B.; Patra P. Graphene quantum dots: Synthesis and applications. Methods in Enzymology 2018, 609, 335–354. 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayyebi A.; Akhavan O.; Lee B.-K.; Outokesh M. Supercritical water in top-down formation of tunable-sized graphene quantum dots applicable in effective photothermal treatments of tissues. Carbon. 2018, 130, 267–272. 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.12.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karakoti A. S.; Shukla R.; Shanker R.; Singh S. Surface functionalization of quantum dots for biological applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 215, 28–45. 10.1016/j.cis.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z.; Bischof J. C. Thermophysical and biological responses of gold nanoparticle laser heating. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1191–1217. 10.1039/C1CS15184C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Ren X.; Wang J.; Sun M. Synthesis of homogeneous carbon quantum dots by ultrafast dual-beam pulsed laser ablation for bioimaging. Mater. Today Nano. 2020, 12, 100091. 10.1016/j.mtnano.2020.100091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bressi V.; Ferlazzo A.; Iannazzo D.; Espro C. Graphene quantum dots by eco-friendly green synthesis for electrochemical sensing: Recent advances and future perspectives. Nanomaterials. 2021, 11, 1120. 10.3390/nano11051120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakilas V.; Tiwari J. N.; Kemp K. C.; Perman J. A.; Bourlinos A. B.; Kim K. S.; Zboril R. Noncovalent functionalization of graphene and graphene oxide for energy materials, biosensing, catalytic, and biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5464–5519. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo P.; Liang R.; Jabari E.; Marzbanrad E.; Toyserkani E.; Zhou Y. N. Single-step synthesis of graphene quantum dots by femtosecond laser ablation of graphene oxide dispersions. Nanoscale. 2016, 8, 8863–8877. 10.1039/C6NR01148A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I.; Arora R.; Dhiman H.; Pahwa R. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Turkish J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 15, 219. 10.4274/tjps.63497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Ryu J. H.; Lee B.; Jung K. H.; Shim K. B.; Han H.; Kim K. M. Laser wavelength modulated pulsed laser ablation for selective and efficient production of graphene quantum dots. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 13658–13663. 10.1039/C9RA02087J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L.; Zhou S.; Huang F.; Zhou H.; Zhang H.; Wang S.; Zhou S. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots synthesized by femtosecond laser ablation in liquid from laser induced graphene. Nanotechnology 2021, 33, 115602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Han H.; Lee K.; Kim K. M. Ultrasensitive Detection of Fe3+ Ions Using Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots Fabricated by a One-Step Pulsed Laser Ablation Process. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 2074–2081. 10.1021/acsomega.1c05542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane A.; Hinkov I.; Brinza O.; Hosni M.; Barry A. H.; Cherif S. M.; Farhat S. One-step synthesis of graphene, copper and zinc oxide graphene hybrids via arc discharge: experiments and modeling. Coatings. 2020, 10, 308. 10.3390/coatings10040308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N.; Salehiyan R.; Chauke V.; Botlhoko O. J.; Setshedi K.; Scriba M.; Masukume M.; Ray S. S. Top-down synthesis of graphene: A comprehensive review. FlatChem. 2021, 27, 100224. 10.1016/j.flatc.2021.100224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R.; Dixit C. Synthesis, characterization and prospective applications of nitrogen-doped graphene: A short review. J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Dev. 2017, 2, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guo A.; Bao K.; Sang S.; Zhang X.; Shao B.; Zhang C.; Wang Y.; Cui F.; Yang X. Soft-chemistry synthesis, solubility and interlayer spacing of carbon nano-onions. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6850–6858. 10.1039/D0RA09410B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Seo J. K.; Park J. H.; Song Y.; Meng Y. S.; Heller M. J. White-light emission of blue-luminescent graphene quantum dots by europium (III) complex incorporation. Carbon. 2017, 124, 479–85. 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor S.; Jha A.; Ahmad H.; Islam S. S. Avenue to Large-Scale Production of Graphene Quantum Dots from High-Purity Graphene Sheets Using Laboratory-Grade Graphite Electrodes. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 18831–18841. 10.1021/acsomega.0c01993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Lv G.; Hu W.; Li D.; Chen S.; Dai Z. Synthesis and applications of graphene quantum dots: a review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 157–185. 10.1515/ntrev-2017-0199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalkhani M.; Shahrokhian S. Adsorptive stripping differential pulse voltammetric determination of mebendazole at a graphene nanosheets and carbon nanospheres/chitosan modified glassy carbon electrode. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 185, 669–74. 10.1016/j.snb.2013.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das P.; Ganguly S.; Banerjee S.; Das N. C. Graphene based emergent nanolights: a short review on the synthesis, properties and application. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 3823–3853. 10.1007/s11164-019-03823-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo S.; Shao M.; Lee S.-T. Upconversion and downconversion fluorescent graphene quantum dots: ultrasonic preparation and photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1059–1064. 10.1021/nn2040395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z.; Li F.; Wu P.; Ji L.; Zhang H.; Cai C.; Gervasio D. F. Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Quantum Dots at Low Temperature for Electrochemical Sensing Trinitrotoluene. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 11803–11. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbaghan M.; Charkhan H.; Ghalkhani M.; Beheshtian J. Ultrasonic route synthesis, characterization and electrochemical study of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2019, 45, 487–505. 10.1007/s11164-018-3613-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Chen Z. G.; Cole I.; Li Q. Structural evolution of graphene quantum dots during thermal decomposition of citric acid and the corresponding photoluminescence. Carbon. 2015, 82, 304–13. 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.10.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehnia F.; Faridbod F.; Dezfuli A. S.; Ganjali M. R.; Norouzi P. Cerium (III) ion sensing based on graphene quantum dots fluorescent turn-off. J. Fluoresc. 2017, 27, 331–338. 10.1007/s10895-016-1962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Song X.; Liu Y.; Fu Y.; Ye L.; Wang N.; Wang F.; Li L.; Mohammadniaei M.; Zhang M. Synthesis of graphene quantum dots and their applications in drug delivery. J. Nanobiotechnoogy 2020, 18, 1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; Song Y.; Zhao X.; Shao J.; Zhang J.; Yang B. The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): current state and future perspective. Nano research. 2015, 8, 355–81. 10.1007/s12274-014-0644-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kellici S.; Acord J.; Power N. P.; Morgan D. J.; Coppo P.; Heil T.; Saha B. Rapid synthesis of graphene quantum dots using a continuous hydrothermal flow synthesis approach. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14716–14720. 10.1039/C7RA00127D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaloeipote G.; Samarnwong J.; Traiwatcharanon P.; Kerdcharoen T.; Wongchoosuk C. High-performance resistive humidity sensor based on Ag nanoparticles decorated with graphene quantum dots. R Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 210407. 10.1098/rsos.210407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu G.; Han Y.; Zhu X.; Gong J.; Luo T.; Zhao C.; Liu J.; Liu J.; Li X. Sensitive Detection of Sulfide Ion Based on Fluorescent Ionic Liquid-Graphene Quantum Dots Nanocomposite. Front Chem. 2021, 9, 658045. 10.3389/fchem.2021.658045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S.; Pan J.; Li C.; Zheng Y. Folic acid-conjugated nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots as a fluorescent diagnostic material for MCF-7 cells. Nanotechnology. 2020, 31, 135701. 10.1088/1361-6528/ab5f7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younis M. R.; He G.; Lin J.; Huang P. Recent advances on graphene quantum dots for bioimaging applications. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 424. 10.3389/fchem.2020.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal Z.; Zarei G. M.; Mohseni S. M.; Ghourchian H. High-performance porphyrin-like graphene quantum dots for immuno-sensing of Salmonella typhi. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021, 188, 113334. 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]