Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

There is a gap in family knowledge of their adolescents’ end-of-life (EOL) treatment preferences. We tested the efficacy of Family Centered Advance Care Planning for Teens with Cancer (FACE-TC) pediatric advance care planning (to increase congruence in EOL treatment preferences.

METHODS

Adolescents with cancer/family dyads were randomized into a clinical trial from July 2016 to April 2019 at a 2:1 ratio: intervention (n = 83); control (n = 43) to either 3 weekly sessions of FACE-TC (Lyon Advance Care Planning Survey; Next Steps: Respecting Choices Interview; Five Wishes, advance directive) or treatment as usual (TAU). Statement of Treatment Preferences measured congruence.

RESULTS

Adolescents’ (n = 126) mean age was 16.9 years; 57% were female and 79% were White. FACE-TC dyads had greater overall agreement than TAU: high 34% vs 2%, moderate 52% vs 45%, low 14% vs 52%, and P < .0001. Significantly greater odds of congruence were found for FACE-TC dyads than TAU for 3 of 4 disease-specific scenarios: for example, “a long hospitalization with low chance of survival,” 78% (57 of 73) vs 45% (19 of 42); odds ratio, 4.31 (95% confidence interval, 1.89–9.82). FACE-TC families were more likely to agree to stop some treatments. Intervention adolescents, 67% (48 of 73), wanted their families to do what is best at the time, whereas fewer TAU adolescents, 43% (18 of 42), gave families this leeway (P = .01).

CONCLUSIONS

High-quality pediatric advance care planning enabled families to know their adolescents’ EOL treatment preferences.

What’s Known on the Subject:

Gaps exist in a family’s knowledge of the end-of-life (EOL) treatment preferences of their adolescent with cancer. Evidence from a single-site pilot study supports the efficacy of the Family-Centered Advance Care Planning for Teens with Cancer (FACE-TC) intervention in increasing congruence in EOL treatment preferences.

What This Study Adds:

A 4-site, randomized clinical trial of FACE-TC closed the gap in families' knowledge. After FACE-TC pediatric advance care planning, and depending on the cancer-specific situation, families had 3 to 6 times the odds of accurately reporting their adolescents’ EOL treatment preferences than did controls.

There is a lack of discussion and documentation regarding end-of-life (EOL) care and treatment preferences for adolescents with serious illnesses.1 Pediatric advance care planning (pACP) is an ongoing process of communication which aims to:

give adolescents a voice in medical treatment decisions if they are unable to speak for themselves;

prepare families so they know what their adolescent would want, if their child should experience serious illness complications;

communicate adolescents’ goals of care and EOL treatment preferences to clinicians; and

document these goals and preferences in the electronic health record.2–4

Early pACP discussions can help seriously ill adolescents and families make future health decisions together about future medical treatments, if the adolescent could not communicate.2–4 However, our team has documented that most families do not know what their adolescent with cancer or HIV would want, if the disease progressed.5–8 In clinical practice, these adolescents rarely have documented advance care plans and the default is to provide intensive treatments that potentially increase suffering.9,10 Despite cancer being the leading cause of disease-related death in adolescents,11,12 conversations about goals of care and documentation of EOL care and treatment preferences for adolescents with cancer are not a routine and standard part of care.13

We developed and pilot tested a structured Family-Centered Advance Care Planning for Teens with Cancer (FACE-TC) in response to this gap in knowledge and documentation.14–16 This developmentally and culturally appropriate intervention is informed by transactional stress and coping theory,17 Leventhal’s theory of self-regulation,18 and the representational approach to patient education.19 Surrogate decision-makers are hereafter referred to as “family.” A single-site pilot trial of FACE-TC demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, safety, and initial efficacy to increase congruence between adolescents and their families regarding EOL treatment preferences, documentation of pACP goals of care, and patients’ and families’ quality of life.14–16 Our goal was to determine if FACE-TC could close the gap in knowledge of EOL treatment preferences between adolescents with cancer and their families in a large, multisite trial. We hypothesized that FACE-TC dyads would achieve better congruence in EOL treatment preferences than controls.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Full details of the trial have been published.20 The study design was a dyadic, (adolescent/family) 2-armed, parallel groups, single-blinded (assessor), intent-to-treat, controlled, randomized clinical trial (RCT). Eligibility criteria for adolescents were diagnosis of cancer, aged 14 to <21 years at enrollment, able to cognitively engage as determined by their oncologist, English-speaking, knows own diagnosis, and not in foster care. Family eligibility criteria were legal guardian of adolescent if adolescent was younger than 18 years, or chosen surrogate if adolescent was ≥18 years at enrollment, English-speaking, and knows patient’s diagnosis. After enrollment, participants underwent secondary screening for exclusion criteria, which included severe depression,21 homicidality,22 suicidality,21 and/or psychosis.22 Excluded participants were linked with psychological services. Dyads were recruited between July 16, 2016, and April 30, 2019, from 4 quaternary pediatric hospitals: Akron Children’s Hospital, Children’s National Hospital, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital.

The institutional review board at each site approved the protocol. Participants provided written informed consent or assent and received compensation of $25 per study visit. An external safety monitoring committee monitored the trial. This RCT follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines.

Procedures

Researchers completed 3 days of training on the protocol and annual booster sessions to ensure fidelity to the study protocol. Facilitators were nurses who received certification in the Respecting Choices training program.23,24 The last author (M.L.) reviewed all videotapes of the Respecting Choices interview, using the Respecting Choices competency criteria checklist,23,24 and provided supervision to facilitators during monthly conference calls.

After consulting with a patient’s primary oncologist, research assistants approached potentially eligible participants face-to-face during hospital outpatient visits and stays. The first visit included enrollment, secondary screening, and, if eligible, completion of baseline questionnaires. Randomization of dyads was at a 2:1 ratio, FACE-TC to treatment as usual (TAU), for ethical considerations, because the pilot14,15 and earlier trials using the FACE model showed benefit.25–28 We used a computer-generated randomization with 2 factors (ie, site and intervention arms), triggered by completion of baseline assessment. Facilitators notified the participants of random assignment to protect the blindness. Blinded assessors, who were not the interventionists/facilitators, read the questionnaires aloud to participants to control for issues of literacy or uncorrected vision, to monitor emotional reactions, to engage participants, and to ensure data completion. Questionnaires were administered to participants separately and in private.

FACE-TC pACP Intervention

Three sessions of ∼45 to 60 minutes were conducted weekly.

Session 1

The Lyon ACP Survey - Adolescent & Surrogate version is a 31-question survey which assessed the adolescents’ goals, values, experiences with death and dying, and EOL treatment preferences.6 The family version asked, for example, “What do you think (child’s name) thinks is the best timing for end-of-life discussions?” The adolescent and family member were administered the survey separately.

Session 2

The Next Steps: Respecting Choices23,24 structured interview was adapted for adolescents with cancer.15 The adolescent and family engaged in a video-taped facilitated conversation, not completion of a form. The adolescent’s understanding of their cancer, complications that could occur, fears, hopes, and experiences with hospitalization and death were explored. Then, 4 cancer-specific situations were used to encourage discussion about the adolescent’s goals and values in “bad outcome” situations. They were asked to explain why they made their choices. The family was asked if they could honor the adolescent’s treatment preferences. The adolescent was then asked if they wanted their family to strictly follow their wishes or to do what they think is best in the moment. The facilitator noted adolescents’ questions on a post card, encouraging the adolescent to discuss their questions with their clinician at the next visit.

Session 3

The adolescent and family together completed the advance directive, Five Wishes.29 The facilitator read each section of the form aloud. The facilitator gave a copy to the family, the primary provider by e-mail, and placed a copy in the electronic health record. For adolescents aged <18 years, their legal guardian’s signature was required on the Five Wishes advance directive. See Supplemental Table 5 for sessions’ foundations, goals, and processes.

Treatment as Usual Control

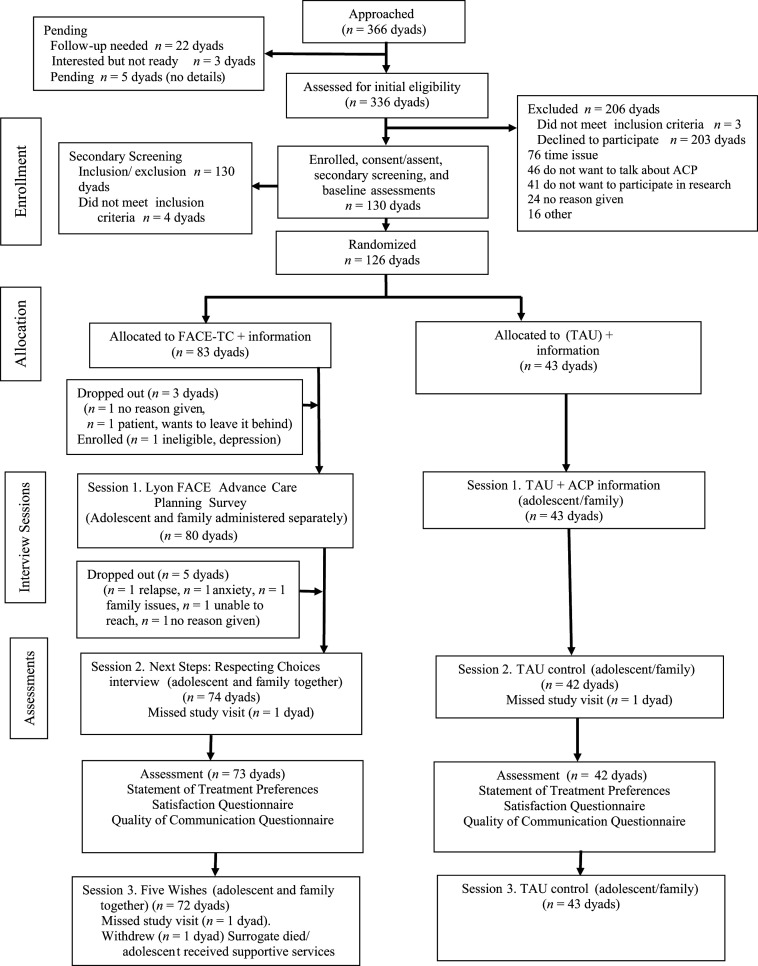

All participants were given a pACP booklet at the baseline assessment, but control dyads did not receive the 3-session–facilitated conversation. Assessments were administered at the same 2 time points as the intervention dyads (baseline and 3 weeks postbaseline) (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Guidelines Checklist diagram of the FACE-TC trial using an intent-to-treat design.

Outcome Measure

The Statement of Treatment Preferences23,24 documented the adolescents’ treatment preferences and obtained the family’s knowledge of the patient’s goals. Four cancer-specific situations and the benefits and burdens of treatment options were discussed:

long hospitalization with low chance of survival;

treatment would extend my life by no more than 3 months and side effects are serious;

physical impairment (cannot walk or talk and need 24-hour nursing care); and

cognitive impairment (do not know who you are, where you are, or who you are with and need 24-hour nursing care).

Choices were “to continue all treatments …,” “to stop all efforts to keep me alive…,” or “do not know.”

A follow-up question clarified the degree of leeway in decision-making authority the adolescent wished to grant the family member, that is, “I would want the person I have chosen to [either] “strictly follow my wishes” or “do what they think is best at the time, considering my wishes.” It was administered either after session 2 for intervention or at 3-weeks postbaseline for TAU.

A demographic data form was used to gather participant-reported age, sex, and race or ethnicity; also, family-reported education, employment status, household income, and household size. Chart abstraction data included diagnosis, date of diagnosis, history of relapse, history of bone marrow transplantation, and on or off active treatment.

Statistical Analysis

We first assessed the difference in the level of overall congruence in EOL treatment preferences in all 4 cancer-related situations between adolescents with cancer and their families. Dyadic responses were matched and a dichotomous variable (Yes: agreement; No: no agreement) was generated for each situation. Then, a 3-level categorical overall congruence measure was created: low (agree 0–1 situation), moderate (agree 2–3 situations), and high (agree all 4 situations). Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the association between the intervention and overall congruence. The strength of the association (effect size) was measured by Cramér’s V.30

Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to determine differences in dyadic congruence between the intervention and control groups in each of the cancer-related situations. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for the multiple testing. Odds ratios (OR) measured the effect size. See the Supplemental Information for Power Analysis.

Data were entered into Research Electronic Data software (version 8.10.18 ©2020). Statistical significance was set to α = 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 130 enrolled dyads, 4 did not meet inclusion criteria; thus, 126 dyads were fully enrolled for randomization (Fig 1). Of those who declined, 23% (46 of 203 dyads) had at least 1 member of the dyad who reported not wanting to talk about pACP, and 37% (76 of 203) had time issues. Compared with female adolescents, male adolescents were significantly more likely to decline participation (difference of 14%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 4–25, P = .02). Age, race, ethnicity, diagnosis, and active treatment status did not significantly differ between those who enrolled and those who declined.

Adolescents had a mean (SD) age of 16.9 (1.8) years, 57% (69 of 126) were female, and 79% (100 of 126) were White (Table 1). Most common diagnoses were leukemia (42 of 126, 33%), solid tumor (34 of 126, 27%), brain tumor (25 of 126, 20%), and lymphoma (19 of 126, 15%). Among families, more than half were at <200% of the 2016 federal poverty level, and 58% had less than a college education. Family members ranged in age from 19 to 67 years; 83% were female; 82% were White; 75% mothers; 15% fathers; and 8% (10 of 126) were nonbiological, patient-chosen surrogate decision-makers. Three adolescent patients had an advance directive in the medical record at baseline. Of the FACE-TC dyads who began Session 1, 90% (72 of 80) completed all 3 sessions (Fig 1). Ninety-one percent (115 of 126) completed all study visits.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Adolescents with Cancer and Their Families (N = 252 Participants)

| Baseline Characteristics | Adolescentsa | Familiesa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACE-TC (n = 83) | TAU (n = 43) | FACE-TC (n = 83) | TAU (n = 43) | |

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.9 (1.8) | 17.0 (2.0) | 45.6 (8.2) | 46.5 (8.4) |

| Range | 14–20 | 14–20 | 19–67 | 20–63 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 45 (54) | 27 (62.8) | 67 (80.7) | 37 (86.0) |

| Male | 38 (46) | 16 (37.2) | 16 (19.3) | 6 (14.0) |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) |

| Asian American | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0) |

| Black or African American | 12 (14) | 5 (12) | 10 (12) | 4 (9) |

| White | 63 (76) | 37 (86) | 68 (82) | 35 (81) |

| More than 1 race | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (7) |

| Declined | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 76 (92) | 40 (93) | 79 (95) | 42 (98) |

| Declined | 2 (2) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Education | ||||

| No high school diploma or GED equivalency | 45 (54) | 26 (60) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| High school or GED equivalency | 28 (34) | 8 (19) | 16 (19) | 7 (16) |

| Some college but no bachelor’s degree | 9 (11) | 9 (21) | 31 (37) | 17 (40) |

| Bachelor's degree, master's degree, doctorate, or professional degree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 34 (41) | 19 (44) |

| Declined | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Income | ||||

| Equal to or below the FPL | N/A | N/A | 21 (25) | 12 (28) |

| 101%–200% of FPL | N/A | N/A | 23 (28) | 14 (33) |

| 201%–300% of FPL | N/A | N/A | 14 (17) | 5 (12) |

| >300% of FPL | N/A | N/A | 23 (28) | 10 (23) |

| Declined | N/A | N/A | 2 (2) | 2 (5) |

FPL, federal poverty line; GED, general equivalency diploma; N/A, not applicable.

Data shown indicate n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

Congruence in EOL Treatment Preferences

The relationship of the family member to the patient was not significantly associated with congruence. Biological fathers (15 of 16, 94%) more accurately reported their adolescent’s treatment preferences, followed by biological mothers (61 of 87,70%), and then nonbiological family (7 of 12, 58%), as shown in Supplemental Tables 6 and 7. Congruence frequencies for each situation are shown in Supplemental Table 8.

Overall treatment preference congruence among adolescent/family dyads in 4 cancer-related situations was significantly greater in the FACE-TC group than that in the TAU group (P < .0001) (Table 2). Thirty-four percent (25 of 73) of intervention dyads had high agreement versus 2% (1 of 42) of controls; 52% (38 of 73) of intervention dyads had moderate agreement versus 45% (19 of 42) controls; and 14% (10 of 73) of intervention dyads had low agreement versus 52% (22 of 42) of controls. Cramér’s V was 0.48, indicating a moderate-effect size.

TABLE 2.

Statement of Treatment Preferences Agreement Group by Intervention (N = 115 Dyads)

| Levels of Agreementa | FACE-TC pACP, Plus pACP Information Frequency (%) | TAU Control, Plus pACP Information Frequency (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agree 0–1 situation/ low agreementb | 10 (14) | 22 (52) | 32 |

| Agree 2–3 situations/ moderate agreement | 38 (52) | 19 (45) | 57 |

| Agree 4 situations/ high agreement | 25 (34) | 1 (2) | 26 |

| Total | 73 | 42 | 115 |

Two-sided Fisher’s exact test, P < .0001. Cramér's V = 0.48. The strength of the association (effect size) was measured by Cramér's V, which has values ranging from 0 to 1: low association (V = 0.1–0.3), moderate association (V = 0.3–0.5), and high association (V > 0.5).22 Cohen's W is equivalent to Cramér's V in our study with 3 × 2 contingency table. The sample size was 115 dyads; 1 dyad had missing data.

Rationale for recoding the data at 3 levels of agreement to generate a new variable is illustrated by the small number of cells for each situation.

Dyadic “do not know” responses were treated as no agreement/no agreement, that is, low agreement.

Table 3 shows congruence by each cancer-specific situation. Results demonstrated statistically significant greater congruence for the intervention than controls for the following:

“a long hospitalization with low chance of survival,” 78% (57 of 73) vs 45% (19 of 42), OR, 4.31 (95% CI, 1.89–9.82);

“having only 3 more months to live and side effects of treatment are serious,” 77% (56 of 73) vs 36% (15 of 42), OR, 5.93 (95% CI, 2.58–13.63);

“cannot walk or talk and need 24-hour nursing care,” 63% (46 of 73) vs 33% (14 of 42), OR, 3.41 (95% CI 1.53–7.57); and

“do not know who you are or who you are with and need 24-hour nursing care,” 66% (48 of 73) vs 43% (18 of 42), OR, 2.56 (95% CI 1.17, 5.58). However, after making the Bonferroni correction, the group difference in situation 4 (cognitive disability) became statistically insignificant.

TABLE 3.

Overall Congruence of Statement of Treatment Preferences Postsession 2 or 3 Weeks Postbaseline Assessment by Study Arm (N = 115 Dyads)

| Situations | Congruencea | FACE-TC pACP (n = 73) | TAU with pACP Information (n = 42) | P | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Long hospitalization with low chance of survival | No | 16 (22) | 23 (55) | .0003 | 4.31 (1.89–9.82) |

| Yes, agree | 57 (78) | 19 (45) | |||

| 2. Having only 3 more months to live and treatments | No | 17 (23) | 27 (64) | <.0001 | 5.93 (2.58–13.63) |

| have serious side effects | Yes, agree | 56 (77) | 15 (36) | ||

| 3. Physical disability: cannot walk or talk and need 24-h nursing care | No | 27 (37) | 28 (67) | .002 | 3.41 (1.53–7.57) |

| Yes, agree | 46 (63.0) | 14 (33.3) | |||

| 4. Cognitive disability: do not know who you are, where you are, or who you are with and need 24-h nursing care | No | 25 (34) | 24 (57) | .0168b | 2.56 (1.17–5.58) |

| Yes, agree | 48 (66) | 18 (43) |

The sample size was 115 dyads; 1 dyad had missing data.

Do not know responses were counted as no agreement/congruence.

After making the Bonferroni correction, the difference among groups in situation 4 was insignificant (corrected P = .0125). This is because our sample size (n = 115) achieved only 78% power to detect an OR of 2.56 in this situation.

Compared with TAU dyads, FACE-TC dyads were significantly more likely to agree to stop treatments in 2 situations (Table 4): “having only 3 more months to live and side effects of treatment are serious,” 56% (41 of 73) vs 21% (9 of 42), OR, 4.70 (95% CI, 1.97–11.21) and “do not know who you are or who you are with and need 24-hour nursing care,” 52% (38 of 73) vs 26% (11 of 42), OR, 3.06 (95% CI, 1.34–7.00). After making the Bonferroni correction, the group difference in “having only 3 months to live” became insignificant.

TABLE 4.

Congruence on Stopping Treatments, as Determined at Postsession 2 for Intervention or 3 Weeks Postbaseline for TAU by Study Arm (N = 115 Dyads)

| Situation | Congruencea | FACE-TC pACP With Information (n = 73) | TAU With pACP Information (n = 42) | P b | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Long hospitalization with low chance of survival | No | 55 (75) | 39 (93) | .0235 | 4.25 (1.17–15.45) |

| Yes, agree to stop | 18 (25) | 3 (7) | |||

| 2. Having only 3 more months to live and treatments have serious side effects | No | 32 (44) | 33 (79) | .0003 | 4.70 (1.97–11.21) |

| Yes, agree to stop | 41 (56) | 9 (21) | |||

| 3. Physical disability: cannot walk or talk and need 24-h nursing care | No | 60 (82) | 37 (88) | .4015 | 1.60 (0.53–4,86) |

| Yes, agree to stop | 13 (18) | 5 (12) | |||

| 4. Cognitive disability: do not know who you are, where you are, or who you are with and need 24-h nursing care | No | 35 (48) | 31 (74) | .007 | 3.06 (1.34–7.00) |

| Yes, agree to stop | 38 (52) | 11 (26) |

The sample size was 115 dyads; 1 dyad had missing data.

Do not know responses were counted as no agreement/congruence.

After making the Bonferroni correction, the difference among groups in situation 1 was insignificant (corrected P = .0125).

Leeway

Adolescents were asked how strictly they wanted their families to follow their wishes. Adolescents in the FACE-TC group were more likely than those in the TAU group, 67% (48 of 73) vs 43% (18 of 42) (P = .01), to endorse “Do what he or she thinks is best at the time, considering my wishes.”

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first fully powered RCT to focus on adolescents with cancer and their engagement with their families in pACP conversations.1,31–34 Findings confirmed our hypothesis that FACE-TC adolescent/family dyads achieved higher overall congruence than TAU control dyads in all 4 cancer-specific situations. Almost half of controls and slightly more than half of intervention dyads had moderate congruence, but only 1 control dyad and 25 FACE-TC dyads had high congruence in all 4 situations. In the control group, half (52%) of adolescents/families had low congruence, compared with only 14% of adolescents/families in the intervention group. Thus, FACE-TC adolescent/family dyads moved toward closing earlier identified congruence gaps.7

Compared with TAU dyads, FACE-TC dyads were also more likely to stop treatments in some scenarios, confirming our pilot study findings15 and HIV adolescent trials.26,27 Thus, high-quality pACP communication fostered understanding in ways that allowed the adolescent and family choice in care trajectories. Allowing choice and giving permission to focus on quality of life may potentially mitigate the regret and distress of bereaved families who wished they had pursued more treatment of their child.35 Control dyads agreed to stop treatments at higher frequencies in the current trial, compared with our single-site pilot, where no dyad in the control group agreed to stop treatments in situations involving a long hospital stay or only 3 more months to live. Perhaps the past 10 years represents a cultural shift in willingness to consider stopping treatments, with increasing national attention on the burdens of intensive treatments at the EOL.36,37 With increased access to palliative care services38 and research,7,38,39 families and patients may better understand that stopping intensive medical interventions when the patient is dying is not giving up, but rather choosing how best to spend the final days of one’s life.

Adolescents in the FACE-TC group gave their families permission to do what they thought was best knowing their wishes, rather than strictly follow their wishes, replicating previous findings using the FACE model.15,27,28,40 Granting leeway has important implications for bereavement care because regret and guilt have an impact on the intensity and complexity of grief and bereavement.41 In a multisite survey study, 73% of bereaved parents endorsed regret, often around treatment decisions.35 Mack and colleagues found regret was less likely when bereaved parents felt satisfied with their role in treatment decision-making.42 Families knowing that their adolescent gave them leeway to do what is best in the moment may be quite important for bereavement care, especially in situations where the adolescent is no longer able to voice preferences. This is not well documented in the current literature.43 Engagement of families in pACP did increase positive appraisals of their caregiving.44 Future research should examine if pACP helps bereaved families cope with their grief, as has been found in an adult study of advance care planning (ACP).45

Of those who declined, 23% (46 of 203) reported not wanting to talk about pACP. In some cases, the adolescent was ready, but the family was not.46 In the FACE model assessment of readiness, to engage in pACP rests with the patient/family dyad, not the clinician,47 thereby preventing gatekeeper bias (eg, mistakenly thinking the patient or family is not ready to discuss these topics) and honoring equipoise (ie, all adolescents with a serious illness have equal access to participation in this process).48 To prevent family-level gatekeeper bias, other evidence-based models of ACP49,50 could be offered for young adults aged 18 years or older whose family is not ready.

This study has limitations. Some analyses had low cell sizes. However, these were a direct reflection of the problem; for example, only 1 dyad in the control group had high congruence, likely not correctable with a larger sample. Thus, CIs were wide. There are no psychometric data on the Statement of Treatment Preference, although it is widely used, enabling replication of research findings.51 The participation rate of 39% affected generalizability, but is comparable to dyadic longitudinal trials of palliative care.52,53 Talking about death and dying is taboo.54 Some families believe it is their role alone to make EOL health care decisions or believe pACP is against their religion.55 Study participants may represent early adopters or pioneers for pACP, potentially increasing its acceptance in the future. Generalizability may not extend beyond pediatric hospitals. Including those who had advance directives is consistent with recommendations for ongoing pACP conversations.13,55,56 Social desirability bias could have occurred with face-to-face assessments. Although using hypothetical situations may not mirror real-life decision-making when the time comes, this likely is the first time such direct conversation has been held with adolescents. Like disaster preparedness,57 this approach is valid, reducing people’s risk and increasing their ability to cope.14,15,25,44,45,58

Conclusions

FACE-TC effectively increased communication between adolescents with cancer and their families about the patients’ EOL treatment preferences, meeting the first challenge of ACP, that is, knowledge of patient preferences.59 This low-tech intervention commits to more deeply respecting adolescents and integrating them into health care decision-making.56 Busy clinicians may benefit from this standardized and structured approach, which increased the odds that families knew what their child wanted and ensured the first conversation about goals of care and EOL treatment preferences did not occur during a medical crisis or in the ICU.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating adolescents and their families. We also thank the following staff who assisted with data collection: Jessica Thompkins, Elaine Churney, Kristine Allmendinger-Goertz, Karuna Ramcharran, Jessica Livingston, Susan M. Flesch, Robin Wilcox, Jami S. Gattuso, Jennifer Zabrowski, Melanie Gattas, Ashley Morris, Daniel H. Grossoehme, Valerie Shaner, Rachel Jenkins, and Alaina A. Martinez.

Glossary

- ACP

advance care planning

- CI

confidence interval

- EOL

end of life

- FACE-TC

Family-Centered Advance Care Planning for Teens With Cancer

- OR

odds ratio

- pACP

pediatric advance care planning

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- TAU

treatment as usual

Footnotes

Dr Lyon conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Baker, Friebert, and Needle collected data from their sites and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Wang and Ms Jiang had full access to all the data in this study, analyzed and interpreted the data, take responsibility for the integrity of the data, conducted the data analysis, and contributed to interpretation of the findings; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research, the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences-Children’s National, or the National Institutes of Health.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifider NCT02693665). Deidentified individual participant data (including data dictionaries) will be made available, in addition to study protocols, the statistical analysis plan, and the informed consent form. The data will be made available on publication to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal for use in achieving the goals of the approved proposal. Proposals should be submitted to mlyon@childrensnational.org.

FUNDING: Supported by the US National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health, Award 5 R01 NR015458-06. This research has been facilitated by the services and resources provided by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences-Children’s National UL1TR0000075 and UL1RR031988. The funders and sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Carr K, Hasson F, McIlfatrick S, Downing J. Factors associated with health professionals decision to initiate paediatric advance care planning: a systematic integrative review. Palliat Med. 2021;35(3):503–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Führer M. Pediatric advance care planning: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e873–e880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mack JW, Fisher L, Kushi L, et al. Patient, family, and clinician perspectives on end-of-life care quality domains and candidate indicators for adolescents and young adults with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2121888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hein K, Knochel K, Zaimovic V, et al. Identifying key elements for paediatric advance care planning with parents, healthcare providers and stakeholders: A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):300–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lyon ME, Dallas RH, Garvie PA, et al. Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . A paediatric advance care planning survey: congruence and discordance between adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(1):e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garvie PA, He J, Wang J, D’Angelo LJ, Lyon ME. An exploratory survey of end-of-life attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(3):373–85.e29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friebert S, Grossoehme DH, Baker JN, et al. Congruence gaps between adolescents with cancer and their families regarding values, goals, and beliefs about end-of-life care. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacobs S, Perez J, Cheng YI, Sill A, Wang J, Lyon ME. Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(4):710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller KD, Fidler-Benaoudia M, Keegan TH, Hipp HS, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for adolescents and young adults, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(6):443–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suh E, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, et al. Late mortality and chronic health conditions in long-term survivors of early-adolescent and young adult cancers: a retrospective cohort analysis from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):421–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sansom-Daly UM, Wakefield CE, %Patterson P, et al. End-of-life communication needs for adolescents and young adults with cancer: recommendations for research and practice. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2020;9(2):157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):710–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. Family-centered advance care planning for teens with cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watson A, Weaver M, Jacobs S, Lyon ME. Interdisciplinary communication: documentation of advance care planning and end-of-life care in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019;21(3):215–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(8):1207–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39(6):935–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donovan HS, Ward SE, Song MK, %Heidrich SM, Gunnarsdottir S, Phillips CM. An update on the representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(3):259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Curtin KB, Watson AE, Wang J, Okonkwo OC, Lyon ME. Pediatric advance care planning (pACP) for teens with cancer and their families: Design of a dyadic, longitudinal RCCT. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;62:121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan MK, et al. The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3): description, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance in the MECA study. Methods for the epidemiology of child and adolescent mental disorders study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):865–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hammes BJ, Briggs L, Schellinger S. Next Steps: ACP Facilitator Certification. La Crosse, WI: Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation, Inc.; 2008, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hammes BJ, Briggs L. Respecting Choices: Palliative Care Facilitator Manual. LaCrosse, WI: Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lyon ME, Garvie PA, D’Angelo LJ, et al. Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . Advance care planning and HIV symptoms in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20173869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lyon ME, Caceres S, Scott RK, et al. Palliative Care Consortium . Advance care planning – complex & working longitudinal trajectory of congruence in end-of-life treatment preferences: an RCT. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(6):634–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lyon ME, D’Angelo LJ, Dallas RH, et al. A randomized clinical trial of adolescents with HIV/AIDS: pediatric advance care planning. AIDS Care. 2017;29(10):1287–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyon ME, Squires L, Scott RK, et al. Effect of family-centered (FACE) advance care planning on longitudinal congruence in end-of-life treatment preferences: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(12):3359–3375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Towey E. Aging with Dignity. Five Wishes. Available at: https://agingwithdignity.org/ Accessed April 18, 2021

- 30. Liebetrau AM. Measures of association. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences Series No 32. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edwards D, Carrier J, Gillen E, Hawker C, Sutton J, Kelly D. Factors influencing the provision of end-of-life care for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Reports. 2013;11(7):386–399 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siden HH, Chavoshi N. Shifting focus in pediatric advance care planning from advance directives to family engagement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(3):e1–e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cuviello A, Yip C, Battles H, Wiener L, Boss R. Triggers for palliative care referral in pediatric oncology. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(6):1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Adolescent and young adult cancer patients’ experiences with treatment decision-making. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20182800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lichtenthal WG, Roberts KE, Catarozoli C, et al. Regret and unfinished business in parents bereaved by cancer: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health . About the palliative care: conversations matter campaign. Available at: https://www.ninr.nih.gov/newsandinformation/conversationsmatter/about- conversations-matter Accessed April 19, 2021

- 38. Frederick NN, Mack JW. Adolescent patient involvement in discussions about relapsed or refractory cancer with oncology clinicians. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(4):e26918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lyon ME, Garvie PA, McCarter R, Briggs L, He J, D’Angelo LJ. Who will speak for me? Improving end-of-life decision-making for adolescents with HIV and their families. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e199–e206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schuelke T, Crawford C, Kentor R, et al. Current grief support in pediatric palliative care. Children (Basel). 2021;8(4):278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mack JW, Cronin AM, Kang TI. Decisional regret among parents of children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(33):4023–4029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. DeCourcey DD, Partin L, Revette A, %Bernacki R, Wolfe J. Development of a stakeholder driven serious illness communication program for advance care planning in children, adolescents, and young adults with serious illness. J Pediatr. 2021;229:247–258.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thompkins JD, Needle J, Baker JN, et al. Pediatric advance care planning and families’ positive caregiving appraisals: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, et al. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):813–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee BC, Houston PE, Rana SR, Lyon MEfor the Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . Who will speak for me? Disparities in palliative care research with “unbefriended” adolescents living with HIV. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(10):1135–1138 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wiener L, Bell CJ, Spruit JL, Weaver MS, Thompson AL. The Road to Readiness: Guiding Families of Children and Adolescents With Serious Illness Toward Meaningful Advance Care Planning Discussions. NAM Perspectives. Commentary. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bona K, Wolfe J. Disparities in pediatric palliative care: an opportunity to strive for equity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4): e20171662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wiener L, Pritchard MA, Babilonia MB, et al. Voicing their choices: advance care planning with adolescents and young adults with cancer and other serious conditions. Palliat Support Care. 2021. [published online ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521001462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Snaman JM, Helton G, Holder RL, %Revette A, Baker JN, Wolfe J. Identification of adolescents and young adults’ preferences and priorities for future cancer treatment using a novel decision-making tool. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(1):e28755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. MacKenzie MA, Smith-Howell E, Bomba PA, Meghani S. Respecting choices and related models of advance care planning: a systematic review of published evidence. Am J Hospice Palliat Care. 2018;35(6):897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kirchhoff KT, Kehl KA. Recruiting participants in end-of-life research. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007-2008;24(6): 515–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walter JK, Rosenberg AR, Feudtner C. Tackling taboo topics: how to have effective advanced care planning discussions with adolescents and young adults with cancer. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(5):489–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Institute of Medicine . In: Field MJ, %Behrman RE, eds.. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-Of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, The National Academies Press; 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Marron JM, Meyer EC, Kennedy KO. The complicated legacy of Cassandra Callender: ethics, decision-making, and the role of adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(4):343–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ejeta LT, Ardalan A, Paton D. Application of behavioral theories to disaster and emergency health preparedness: a systematic review. PLoS Curr. 2015;7: ecurrents.dis.31a8995ced321301466 db400f1357829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lin CJ, Cheng YI, Garvie PA, D’Angelo LJ, Wang J, Lyon MEfor the Pediatric Palliative Care Consortium . The effect of family-centered (FACE®) pediatric advanced care planning intervention on family anxiety: a randomized controlled clinical trial for adolescents with HIV and their families. J Fam Nurs. 2020;26(4):315–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Glass DP, Wang SE, Minardi PM, Kanter MH. Concordance of end-of-life care with end-of-life wishes in an integrated health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e213053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.