Abstract

As a fish unique to Yunnan Province in China, Sinocyclocheilus grahami hosts abundant potential probiotic resources in its intestinal tract. However, the genomic characteristics of the probiotic potential bacteria in its intestine and their effects on S. grahami have not yet been established. In this study, we investigated the functional genomics and host response of a strain, Lactobacillus salivarius S01, isolated from the intestine of S. grahami (bred in captivity). The results revealed that the total length of the genome was 1,737,623 bp (GC content, 33.09%), comprised of 1895 genes, including 22 rRNA operons and 78 transfer RNA genes. Three clusters of antibacterial substances related genes were identified using antiSMASH and BAGEL4 database predictions. In addition, manual examination confirmed the presence of functional genes related to stress resistance, adhesion, immunity, and other genes responsible for probiotic potential in the genome of L. salivarius S01. Subsequently, the probiotic effect of L. salivarius S01 was investigated in vivo by feeding S. grahami a diet with bacterial supplementation. The results showed that potential probiotic supplementation increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, and POD) in the hepar and reduced oxidative damage (MDA). Furthermore, the gut microbial community and diversity of S. grahami from different treatment groups were compared using high-throughput sequencing. The diversity index of the gut microbial community in the group supplemented with potential probiotics was higher than that in the control group, indicating that supplementation with potential probiotics increased gut microbial diversity. At the phylum level, the abundance of Proteobacteria decreased with potential probiotic supplementation, while the abundance of Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota increased. At the genus level, there was a decrease in the abundance of the pathogenic bacterium Aeromonas and an increase in the abundance of the potential probiotic bacterium Bifidobacterium. The results of this study suggest that L. salivarius S01 is a promising potential probiotic candidate that provides multiple benefits for the microbiome of S. grahami.

Keywords: Sinocyclocheilus grahami, lactobacillus salivarius, genomic characterization, antioxidant enzymes, gut microbiome

Introduction

Sinocyclocheilus grahami, belonging to the family Cyprinidae, subfamily Barbinae, and genus Sinocyclocheilus, is unique to Dianchi Lake in Yunnan. Known as one of the “four famous fish,” S. grahami is fished, consumed, and considered an important economic fish (Yin et al., 2021). However, because of the destruction of its habitat and invasion by exotic species, S. grahami was listed as a Grade II protected animal in 1989, and further as an endangered animal in 1998. In 2007, to save the species from extinction, the artificial reproduction of S. grahami was achieved for the first time. After four generations of manual selection and breeding, a high-quality new national variety (“S. grahami, Bayou No. 1”) was certified in 2018 (Yin et al., 2021). Nevertheless, during the process of artificial breeding, antibiotics were commonly used to treat diseases in specimens, including gill and skin inflammation (Yang et al., 2007).

In aquaculture, antibiotics are often used as additives to treat and prevent diseases, because they can inhibit the reproduction of bacteria (Vaseeharan and Thaya, 2014). However, antibiotic overuse has led to the emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens, damaging the environment, and posing a risk to public safety and health. Previous studies have shown that superbugs resistant to multiple antibiotics can be transmitted among animals and humans through contaminated food and water (Davies and Davies 2010). For instance, contamination with Vibrio parahaemolyticus was observed in 95 (38.0%) of 250 aquatic product samples from Guangdong, China, among which 90.53% of the strains showed streptomycin resistance (Xie et al., 2017). In January 2020, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China issued a comprehensive ban on the addition of antibiotics to animal feed to address issues related to drug residues and antibiotic resistance (Zhou et al., 2021). Therefore, the excavation of a safe and effective alternative to antibiotics, including probiotics, is urgently needed.

Many mechanisms have been proposed to explain the positive effects of probiotics, including stimulating the immune system, helping the host to resist the invasion of external harmful substances and disease-curing organisms, and aiding with digestion (Macfarlane and Macfarlane, 1997; Dong et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2021). For instance, Bacillus cereus NY5 can antagonize Streptococcus lactis by modulating specific and non-specific immunity in tilapia (Ke et al., 2022). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG normalizes gut dysmotility induced by environmental pollutants (oxytetracycline, arsenic, polychlorinated biphenyls and chlorpyrifos) via affecting serotonin level in zebrafish larvae (Wang et al., 2022). Bifidobacteria are proved to be capable of relieving colitis symptoms in both in vivo and in vitro experiments through following potential mechanisms (e.g., enhancing the hosts’ antioxidant activity, decreasing myeloperoxidase activity, and reactive oxygen species, et. al; Yao et al., 2021). Moreover, in contrast with traditional antibiotics, probiotics fight bacterial diseases and treat inflammation without increasing resistance, through their antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory action (Vanderhoof and Young, 1998; Abd El-Ghany et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). Also, probiotics used as a water supplement can improve water quality by affecting the microbial communities of the environment and reducing metabolic waste in the water system (Talpur et al., 2013). These characteristics have led to the widespread use of probiotics in animal farming, particularly in aquaculture. In aquaculture, probiotics can regulate and rebuild the microecological balance of the gut, enhance immunity against diverse pathogens, and improve the conversion rate of feed energy and growth performance (Merrifield et al., 2010; Akhter et al., 2015; Hoseinifar et al., 2018; Chauhan and Singh, 2019; Ringø, 2020). For instance, Lactobacillus salivarius can inhibit the growth of Vibrio spp. within pike-perch larvae, as well as improve ossification and survival rates (Ljubobratovic et al., 2020). However, while different sources of probiotics have shown consistent and favorable results in higher vertebrates, the effects on the gut of fish are variable. Meanwhile, the use of host-associated probiotics as feed additives has a positive effect on fish farming, as reported by Tarkhani et al. (2020). Therefore, probiotic bacteria isolated from the host gut show greater potential to replace antibiotics than non-specific probiotics.

In recent years, increasing evidence has shown that the gut microbiota plays a key role in maintaining health and controlling disease, regulating many important physiological functions of the host (Tran et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2021). Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and their metabolic derivatives can improve the gut microbiota and enhance the host’s immunity against external harmful substances and pathogenic bacteria (Wang et al., 2021). For instance, feeding crucian carp Lactococcus lactis was effective as a treatment for intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function damage caused by Aeromonas hydrophila (Dong et al., 2018). Lactobacillus rhamnosus recovered the growth of zebrafish larvae under perfluorobutanesulfonate exposure via its antioxidant properties, reshaping the gut microbiota, and enhancing the production of bile acids (Sun et al., 2021). Previous studies reported that the gut microorganisms and antioxidant system have synergistic effects against harmful external substances in animals (Uchiyama et al., 2022). Interestingly, LAB was reported to be involved in the activation of antioxidizing systems in animals, promoting their adaptation to external changes (Han et al., 2022). However, the effect of LAB on S. grahami is not reported. This study is the first to investigate the intestinal microbial changes in S. grahami after feeding with host-associated LAB.

Lactobacillus salivarius, is a host-associated bacterium previously isolated from the gut of S. grahami (Xin et al., 2022). We have isolated and obtained five potential probiotics with high antibacterial activity (i.e., two Bacillus subtilis, two Lactobacillus sake and one L. salivarius) from the gut of S. graham. Particularly, the bacteriocin LSP01 produced by L. salivarius 01 exhibited the best antibacterial activity against A. hydrophila. L. salivarius inhibits the growth of pathogens by disrupting cellular activity and inducing pore size formation in A. hydrophila cells. Therefore, in this study, L. salivarius 01 was used to explore the probiotic potential. The whole genome was sequenced to evaluate the safety and potential properties of the strain at the genetic level. In addition, the effect of L. salivarius on the antioxidant capacity of the hepar and intestinal microbial populations of S. grahami was assessed using feeding experiments. As a result, L. salivarius was confirmed as a safe and effective potential probiotic that can increase the antioxidant capacity and improve the gut microbiota of S. grahami.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Lactobacillus salivarius S01 is a host-associated potential probiotic isolated from the gut of S. grahami (bred in captivity) and preserved in Engineering Research Center for Replacement Technology of Feed Antibiotics of Yunnan College (Xin et al., 2022). For routine use, the strains were grown and subcultured in MRS broth at 37°C for 24 h.

Whole genome sequencing

The total genomic DNA of L. salivarius S01 was extracted using the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) method combined with a purification column. Total genomic DNA was sequenced using an ONT PromethION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). For filtering, low-quality and short-length reads were discarded from the raw reads. The reads were assembled using Unicycler V0.4.9 software (Wick et al., 2017). The annotation of the assembled genome of L. salivarius S01 was performed using Prokka V1.12 software (Seemann, 2014). RepeatMasker V4.1.0 software was used to predict repeat sequences in the genome of L. salivarius S01. The prediction of pseudogenes of L. salivarius S01 was performed using Pseudofinder software. MinCED V0.4.2 software was used to predict the sequence of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats (CRISPRs) on the chromosome of L. salivarius S01. Genomic islands in the genome of L. salivarius S01 were predicted by IslandViewer 4 (http://www.pathogenomics.sfu.ca/islandviewer/). The prophage in the genome of L. salivarius S01 was predicted using PhiSpy (https://github.com/linsalrob/PhiSpy).

The predicted gene sequences were compared using several functional databases, including Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG; Tatusov et al., 2000), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; Kanehisa et al., 2004), Swiss-Prot, and RefSeq, using BLAST+ (2.5.0+). The gene function annotation results were obtained, followed by gene function annotation analysis, such as COG and KEGG metabolic pathway enrichment analysis and gene ontology (GO) function enrichment analysis. Finally, the secondary metabolism gene cluster was analyzed using antiSMASH (v5.2.0), while the bacteriocin synthesis gene cluster of the strain was analyzed using BAGEL4 (Blin et al., 2019).

The presence of antimicrobial resistance genes was compared using the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) (McArthur et al., 2013). The CARD database is constructed as the Antibiotic Resistance Ontology (ARO) taxonomic unit to correlate information on antibiotic modules and their targets, gene variants, etc.

Antibiotic sensitivity

Standard disc diffusion was performed for antibiotic susceptibility testing according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; Keter et al., 2022). L. salivarius S01 were cultured on MRS broth for 24 h to determine the antibiotic sensitivity of selected strains to antibiotic (i.e., tetracycline, erythromycin, penicillin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol). The experiment was repeated three times independently.

Tolerance To gastrointestinal conditions

An in vitro artificially simulated gastrointestinal juices model was applied, following the previously reported methods, with minor modifications (Li et al., 2020). The simulated gastric juice was prepared by adding 10 g/l pepsin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) to 16.4 ml of sterile 0.1 mol/l HCL, filtered through a membrane with 0.22 μm pore, and adjusted to pH 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 using sterile 1 mol/l NaOH. The simulated intestinal juice was prepared by adding 10.0 g/l trypsin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and 6.8 g of KH2PO4 to 500 ml of sterile ddH2O. The pH was adjusted to pH 6.8 using 1 mol/l NaOH and filtered through a membrane with 0.22 μm pore. One milliliter of L. salivarius S01 (approximately 107–108) suspension was inoculated into 5 ml of simulated gastric juice at pH 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0, and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. One milliliter of L. salivarius S01 (approximately 107–108) suspension was also inoculated into 5 ml of simulated intestinal juice for 4 h. Then, the bacterial solutions were cultured on MRS agar for 24 h to determine the tolerance of selected strains to simulated gastrointestinal juice: Survival rate (%) = lg N1 / lg N2 × 100%, where N2 is the total viable counts of the selected strains at 0 h and N1 is the total viable counts after exposure to the simulated gastrointestinal juice for different time periods.

Fish husbandry and experimental methods

The S. grahami specimens used for the experiments were donated by Yiliang jianzhiyuan Food Co., Ltd. (Kunming, Yunnan). After one week of quarantine, a total of 60 healthy, non-injured, and undeformed S. grahami fingerlings (8.0 ± 1.5-mm long) were randomly assigned to six continuously aerated 300-L aquariums, equipped with temperature and oxygen supply control devices.

The experiment was comprised of two groups: the control group (n = 3, 10/cylinder), named as LSC, which was fed basal feed (Satura, Kunming, China), and the treatment group (n = 3, 10/cylinder), named as LSM, which was fed the basal diet supplemented with L. salivarius (approximately 1 × 107 CFU/g). All samples (60) were treated. L. salivarius S01 was inoculated in MRS broth with 1% pitch rate and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Afterwards, bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min, supernatant was discarded, and cell pellet was resuspended in PBS solution. L. salivarius S01 was mixed with the diet and homogenized, and pelleted using oscillating granulator (Daxiang, Guangzhou, China) with 125 μm mesh. At last, mixed diet was dried at room temperature in a ventilated room. Dried pellets for plate-coating inspection. L. salivarius S01 (approximately 1 × 107 CFU/g) was measured by viable bacteria. The specimens were fed a quantity of 3% of their body weight twice a day for 28 consecutive days. The light–dark cycle ratio was 14 h: 10 h, and all water quality standards, including temperature (18 ± 0.5°C), pH (8.0 ± 0.5), and DO (8.5 ± 0.12 ppm), were monitored daily. Half of the water in the tank was replaced each day to ensure the best growth conditions for the fish. The experimental animals were processed in accordance with the recommendations from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Research of Kunming University of Science and Technology.

Sampling for analysis

At the end of the feeding experiment and after fasting for 24 h, three fish were randomly selected from the control and experimental groups, respectively, and the tissue samples were collected. The hepar of S. grahami were collected by dissection, then triturated in pre-cooled homogenization medium (0.01 M Tris–HCl, 0.001 M EDTA-Na2, and 0.01 M sucrose, pH 7.4). S. grahami hepar were collected by autopsy and ground in pre-chilled homogenizing medium (0.01 M Tris–HCl, 0.001 M EDTA-Na2, and 0.01 M sucrose, pH 7.4), and centrifuged (4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C). The resulting supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of hepatic antioxidant enzyme activity. Gut samples from the same fish were collected, placed in Eppendorf tubes, and stored at −80°C.

Hepatic antioxidant enzyme activity assay

The supernatant was incubated with the enzyme-substrate and read at the indicated wavelength using a UV-8000ST spectrophotometer (Shanghai Yuanxi Instruments Co., Ltd.). The enzyme activity assay was performed in triplicate. The catalase (CAT; E.C.1.11.1.6), superoxide dismutase (SOD; E.C.1.15.1.1), and peroxidase (POD; E.C.1.11.1.7) activities and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined. Commercial assay kits were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineering (Nanjing, China), and all enzyme activity assays were measured, according to the kit instructions. CAT activity was measured using the CAT Activity Assay Kit (cat. no. A007-1-1). CAT can catalyze the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, and ammonium molybdate can quickly prevent the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. The remaining hydrogen peroxide can quickly combine with ammonium molybdate to form a pale-yellow complex that can be measured at 405 nm. SOD activity was measured using a total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) detection kit at 550 nm (hydroxylamine method; cat. no. A001-1-2). The change in POD activity was measured using a peroxidase assay kit at 420 nm (cat. no. A084-1-1). The MDA levels were measured using the Malondialdehyde Assay Kit at 532 nm (TBA method) (cat. no. A003-1-1).

Gut microbiota analysis

The fish gut samples were sent to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. for sequencing. The sequencing primers were primer 338F (ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG) and primer 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) for amplifying the V3-V4 region of 16S rRNA gene. Sequence analysis was performed using QIIME 1.7 and FLASH 1.2. QIIME 1.7 was used to remove low-quality fragments from the original reads, and FLASH 1.2 was used to complete read merging. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered using Uparse based on the threshold of the similarity being above 97%. The RDP classifier algorithm was used to compare the 97% similar OTU representative sequences with the SILVA database for taxonomic analysis.

Statistical analysis

Gut microbial data validated by multiple comparisons (Knight et al., 2018). Student’s t-test (two-tailed test) was used to identify significant differences between two groups in phylum and genus level. Multiple testing adjustment of the data by Benjamini-Hochberg (BH).

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Independent samples t-test (two-tailed test) was used to evaluate between-group variance. One-way ANOVA plus least significant difference (LSD) method was employed to analyze multi-group significance. p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Draft genome sequencing, assembly, and mapping

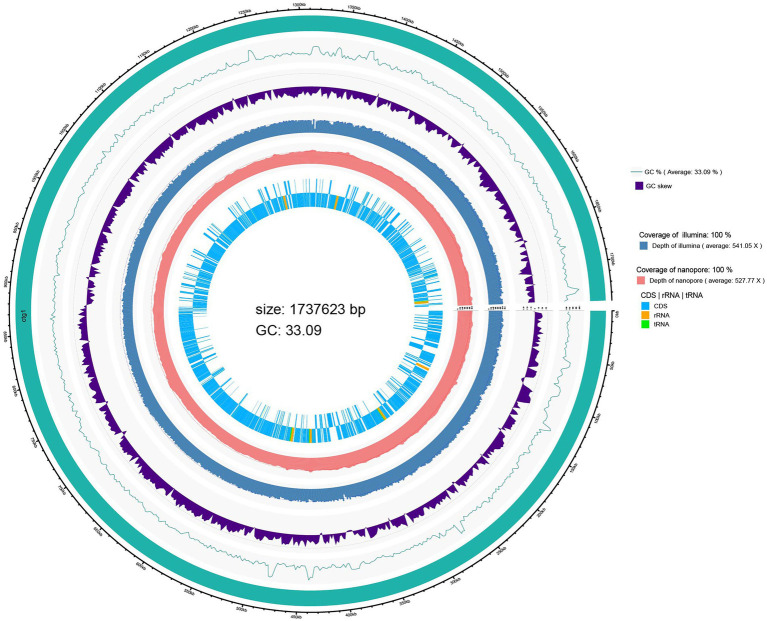

A genome circle map drawn by integrating the predicted genome information annotation is shown in Figure 1. The innermost circle shows the coding regions (CDS) and non-coding RNA regions (rRNA and tRNA) of the genome. The whole genome sequencing results showed that the genome size of L. salivarius S01 was 1,737,623 bp with a GC content of 33.09%. A total of 1753 coding DNA sequences (CDSs), 22 rRNA operons (including 7 23S rRNA, 7 16S rRNA, 8 5S rRNA), and 78 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were found in the genome of L. salivarius S01. In addition, one CRISPR sequence and four gene islands were predicted.

Figure 1.

Circular genome map of L. salivarius S01.

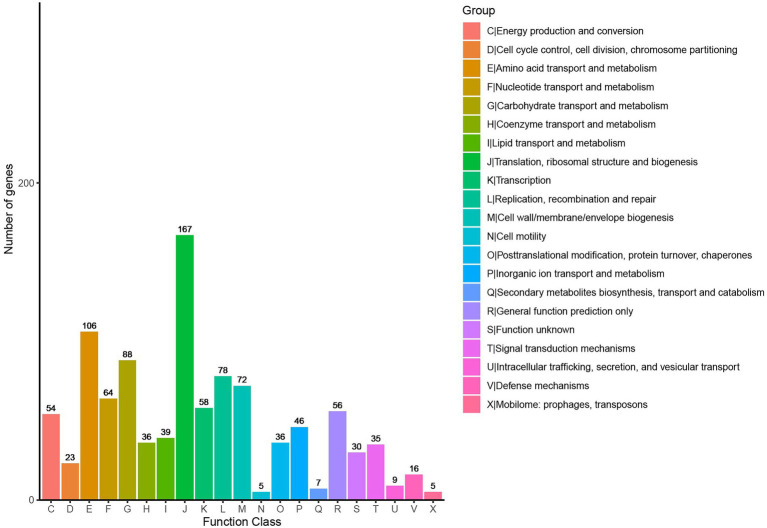

The CDSs on the chromosome of L. salivarius S01 were annotated using the COG database, and the results are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. One thousand and five genes were annotated into 21 functional categories through the COG database. The major COGs were translation/ribosomal structure and biogenesis (167), amino acid transport and metabolism (106), carbohydrate transport and metabolism (88), replication/recombination/repair (78), and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (72). Furthermore, GO analysis revealed that 470 genes were classified into biological processes, 991 genes were classified into cellular components, and 1,037 genes were associated with molecular functions (Figure S1). One thousand and hundred ninety genes involved in KEGG metabolic pathway analysis were classified into five major categories: Metabolism class (866), followed by Genetic Information Processing (183), Environmental Information Processing (112), Organismal Systems (15), and Cellular Processes (14; Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of genes across COG functional categories in the genome of L. salivarius S01.

Genomic characterization of probiotic traits

Genes for the following probiotic features were examined: tolerance to stress conditions, aid in adhesion and colonization, antioxidative stress immunity, and protective repair of DNA and proteins. The genomic analysis detected 21 genes encoding proteins that may be related to the tolerance of digestive enzymes, bile salts, and acidic environments. Furthermore, genes related to immune response against oxidative stress, and protein and DNA molecular repair protection were also present in the genome (Table 1).

Table 1.

Probiotic-related genes present in L. salivarius S01.

| Gene | Putative function | Locus tag |

|---|---|---|

| Stress resistance genes | ||

| dnaJ | Temperature tolerance | M9Y03_02835 |

| htpX | Temperature tolerance | M9Y03_01245 |

| dnaK | Temperature tolerance | M9Y03_02830 |

| nhaC_1 | Acid resistantce | M9Y03_04420 |

| nhaC_2 | M9Y03_04070 | |

| DNA and protein protection and repair | ||

| clpb | Persistence capacity in vivo | M9Y03_04110 |

| clpp | M9Y03_05525 | |

| msrB | Persistence capacity in vivo | M9Y03_00160 |

| Adhesion ability | ||

| dnaK | Mucin binding | M9Y03_02830 |

| gndA | Promotes adherence to epithelial cells | M9Y03_03165 |

| eno | Collagen binding | M9Y03_05500 |

| Immunomodulation | ||

| dnaK | Protection against osmotic shock | M9Y03_02830 |

| trxA | NADPH-depended oxidoreductase activity | M9Y03_06945 |

| trxB | NADPH-depended oxidoreductase activity | M9Y03_08055 |

Genomic characterization of antibacterial substances production

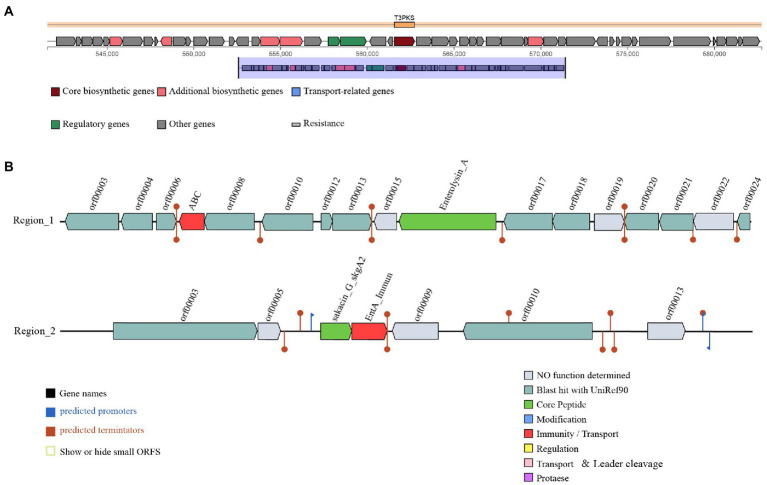

Three gene clusters related to antibacterial substances synthesis were predicted in the L. salivarius S01 genome (Figure 3). The antiSMASH database predicted the existence of a polyketide synthase (T3PKS) synthesis gene cluster in the genome. Based on BAGEL4 platform, the results showed that the genome contained two bacteriocin synthesis gene clusters, as predicted: Enterolysin A as the core gene, including one immune gene and multiple transporter genes, and sakacin_G_skgA1 (class II bacteriocin) as the core gene, including a bacteriocin immune protein gene and a replication initiation protein gene.

Figure 3.

Prediction of antimicrobial-associated protein structures in the genome of L. salivarius S01. (A) Synthetic gene cluster of polyketide synthase (T3PKS; based on antiSMASH database prediction). (B) Two bacteriocin (region_1: Enterolysin_A and region_2: Sakacin_G) synthesis gene clusters (predicted based on the BAGEL4 database).

Resistance genotypes and phenotypes

The predicted results of antibiotic resistance genes are shown in Table 2. The identities of tet (L) and ErmC were 98.03 and 93.85%, respectively; The identities of Escherichia coli EF-Tu mutants conferring resistance to kirromycin and Staphylococcus aureus rpoB mutants conferring resistance to rifampicin were 73.03 and 72.14%, respectively; The identities of other antibiotic resistance genes was less than 70%.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance genes present in L. salivarius S01.

| Best_Hit_ARO | Best_Identities | Drug Class |

|---|---|---|

| tet(L) | 98.03% | tetracycline antibiotic |

| ErmC | 93.85% | macrolide antibiotic; lincosamide antibiotic; streptogramin antibiotic |

| Escherichia coli EF-Tu mutants conferring resistance to kirromycin | 73.03% | elfamycin antibiotic |

| Staphylococcus aureus rpoB mutants conferring resistance to rifampicin | 72.14% | rifamycin antibiotic |

Antibiotic sensitivity tests showed that Lactobacillus salivarius S01 had good antibiotic sensitivity (Table 3). L. salivarius S01 were sensitive to some antibiotics (penicillin, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol); L. salivarius S01 were intermediate sensitive to tetracycline. L. salivarius S01 were resistant to erythromycin.

Table 3.

Antibiotic sensitivity of L. salivarius S01 strains to resistance phenotypes.

| Disk content (μg) | Antibiotic sensitivity | |

|---|---|---|

| Tetracycline | 30 | I |

| Erythromycin | 15 | R |

| Penicillin | 10 | S |

| Ampicillin | 30 | S |

| chloramphenicol | 30 | S |

“S”: Susceptible; “I”: Intermediate; “R”: Resistant.

Survival under simulated gastrointestinal conditions

The simulated intestinal and gastric juices tolerance of L. salivarius S01 at pH 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 are shown in Table 4. The results showed that, under simulated gastric juice treatment, the survival rate of the selected strains gradually decreased at lower pH, but maintained a high survival rate (> 79.84%) at all pH conditions. Under the simulated intestinal juice treatment, the survival rate of the strain was 94.04%, indicating that the strain adapted well to intestinal conditions.

Table 4.

Survival of L. salivarius S01 in simulated gastric and intestinal juices environments.

| Classification | Mean of viable count (lg CFU/ mL) ± SD |

Survival (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of exposure (h) |

||||

| 0 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Simulated gastric juice (pH = 2.0) | 7.54 ± 0.04 | 6.02 ± 0.29 | —— | 79.84 |

| Simulated gastric juice (pH = 3.0) | 6.24 ± 0.29 | —— | 82.76 | |

| Simulated gastric juice (pH = 4.0) | 6.56 ± 0.21 | —— | 87.00 | |

| Simulated intestinal juice | 8.24 ± 0.12 | —— | 7.75 ± 0.05 | 94.05 |

Hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities altered By L. salivarius supplementation

As shown in Table 5, the levels of hepatic SOD, CAT, and POD in the experimental group fed with L. salivarius S01 were significantly higher than those in the control group (p < 0.05). Compared with the control, the SOD, CAT, and POD enzyme activity of LSM increased significantly to 25.87 ± 2.21 U/g (1.5-fold), 124.15 ± 3.91 U/g (1.8-fold), and 577.67 ± 40.22 U/g (2.0-fold), respectively (p < 0.05). The MDA levels were significantly decreased by 43.04% in LSM groups compared with control groups (p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Effect of L. salivarius S01 on the activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, and POD) and the MDA levels in the S. grahami hepar.

| LSC | LSM | |

|---|---|---|

| SOD (U/g) | 17.68 ± 1.70a | 25.87 ± 2.21b |

| CAT (U/g) | 68.21 ± 4.52a | 124.15 ± 3.91b |

| POD (U/g) | 289.83 ± 31.79a | 577.67 ± 40.22b |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 61.90 ± 2.92a | 35.26 ± 11.71b |

Values marked with superscripts with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Effects of L. salivarius S01 On fish gut microbiota

After eliminating low-quality reads from the raw sequences of six intestinal bacterial samples of S. grahami, a total of 563,372 high-quality reads were obtained. These were then clustered into 572 OTUs based on the 97% 16S rRNA sequence similarity.

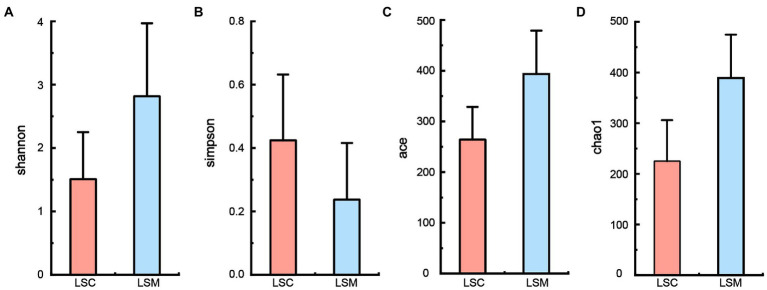

Alpha diversity indices were used to evaluate the richness and diversity of the gut microbiota in the experimental and control groups, as shown in Figure 4. Some difference was observed among the indices reflecting community richness (including Chao1 and Ace) and the indices reflecting community diversity (including Shannon and Simpson) between the two groups.

Figure 4.

Alpha diversity of gut microbiota. (A) Shannon index. (B) Simpson index. (C) Ace index. (D) Chao1 index. *p < 0.05.

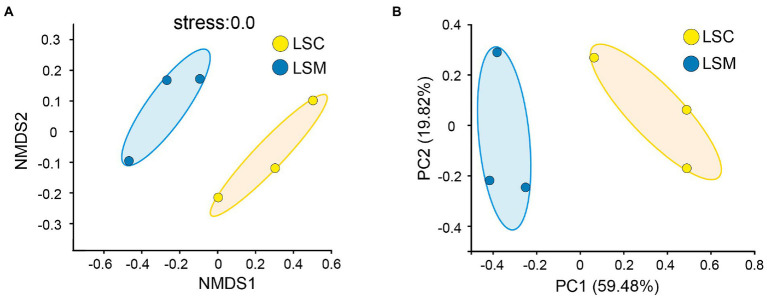

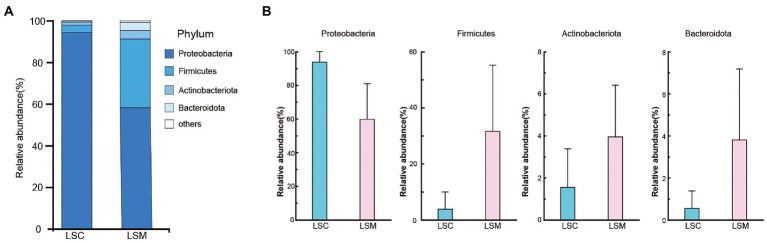

The beta diversity of the samples was analyzed using principal component analysis (PCoA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis (NMDS). The PCoA and NMDS results showed that the six samples were clearly divided into two clusters, consistent with the grouping (Figure 5). The reliability of the model was reflected by the stress value, equal to 0.0 in NMDS. These results demonstrated that while the bacterial supplementation did not change the richness of the gut microbiota, the community data was significantly altered compared with the control group. At the phylum level, the two groups of gut microbes were mainly composed of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota, among others (Figure 6). Multiple testing adjustment of the gut microbial data by Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method. The corrected p-values for all the phylum level are 0.4206. In the control group, Proteobacteria was the most dominant bacterial phylum, accounting for 93.86% of all OTUs, followed by Firmicutes, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota, accounting for 3.91, 1.55, and 0.56%, respectively. Compared with the control, the order of the proportion of dominant bacteria in the experimental group did not change. However, in the experimental group, the proportion of Proteobacteria decreased to 63.78% of the control group, accounting for 59.86%, and the proportion of Firmicutes increased to 8.1-fold that of the control group, accounting for 31.64%. Compared with the control group, the proportions of the Actinobacteriota and Bacteroidota phyla increased to varying degrees, accounting for 3.95 and 3.82% of the bacterial microbiota, respectively.

Figure 5.

Beta diversity of gut microbiota. (A) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA). (B) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS).

Figure 6.

Composition of the phylum of the gut microbiota in S. grahami. (A) Relative abundance of the first five phyla. (B) Comparative differences at the phylum level of the gut microbiota. *p < 0.05.

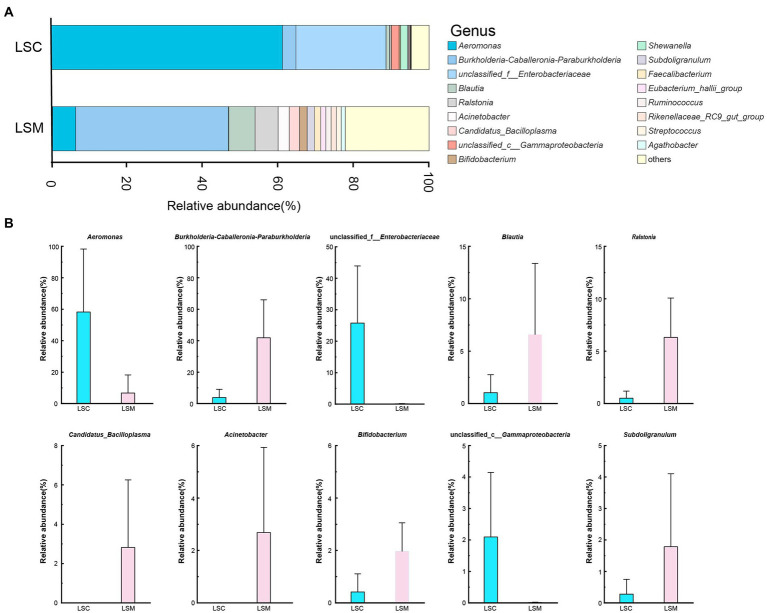

At the genus level, we mapped the top 10 dominant bacterial genera (Figure 7). Multiple testing adjustment of the gut microbial data by Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method. The corrected p-values for the top 10 dominant bacterial genera are 0.4269. Among them, the proportion of Aeromonas varied between the control and experimental group. The proportion varied from 58.23 to 6.72%. The differences of the other nine genera between the control and experimental groups were not significant. Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia, Blautia, Ralstonia, Bifidobacterium, and Subdoligranulum increased by 10.75-, 6.30-, 12.32-, 4.72-, and 6.45-fold, respectively, while Candidatus_Bacilloplasma and Acinetobacter increased from a negligible amount to 2.82 and 2.68%, respectively. Among them, the microbiota proportion of unclassified Enterobacteriaceae and Gammaproteobacteria decreased from 25.74 and 2.10% to a negligible amount. These results indicate that after treatment with L. salivarius S01, the proportion of dominant bacteria in the gut microbiota was decreased, while the overall microbiota diversity increased.

Figure 7.

Composition of the genus of the gut microbiota in S. grahami. (A) Relative abundance of the first 17 genera. (B) Comparative differences at the genus level of the gut microbiota. *p < 0.05.

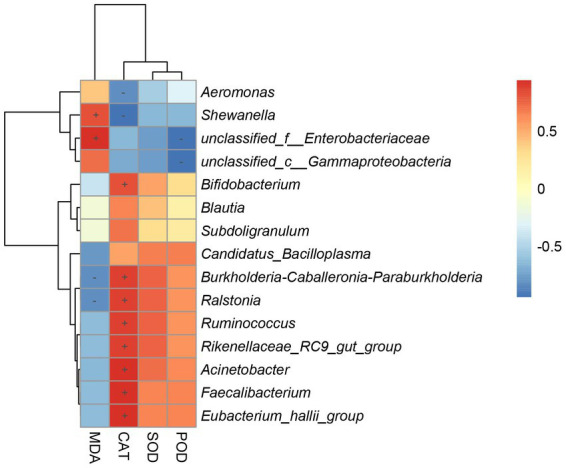

Association of gut bacteria genus with hepatic antioxidant enzyme

To determine the gut bacteria genus involved in the antioxidant capacity observed in the host, we performed correlation analysis between gut bacterial genus and hepatic antioxidant enzyme activity (Figure 8). Shewanella and unclassified_f__Enterobacteriaceae were positively associated with the MDA contents of the hepar. Bifidobacterium, Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia, Ralstonia, Ruminococcus, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, Acinetobacter, Faecalibacterium, and Eubacterium_hallii_group were positively associated with the CAT contents of the hepar. Burkholderia-Caballeronia-Paraburkholderia and Ralstonia were negatively associated with the MDA contents of the hepar. Aeromonas and Shewanella were negatively associated with the CAT contents of the hepar. Unclassified_f__Enterobacteriaceae and unclassified_c__Gammaproteobacteria were negatively associated with the POD contents of the hepar.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of correlation coefficient between gut microbiota and antioxidant enzymes activity. “+” indicates a positive correlation (p < 0.05) and “-” indicates a negative correlation (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Microecological preparations can improve the immunity of the host, and other beneficial characteristics, such as a lack of drug resistance, and no toxic side effects (Mingmongkolchai and Panbangred, 2018). At present, probiotic microecological preparations are widely used in aquaculture (Gopi et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022). However, there is no standard for the selection of probiotics for use in microecological preparations. Host-associated probiotics isolated from the hosts may be have reportedly the most beneficial effects (Giri et al., 2014; Hao et al., 2017; Sharifuzzaman et al., 2018; Zuo et al., 2019). In this study, L. salivarius S01, originally isolated from the gut of S. grahami, was used as a feed additive in S. grahami. According to our previous study, a bacteriocin produced by L. salivarius S01 exhibited excellent inhibition effects against 12 common pathogens (both fish- and food-derived; Xin et al., 2022). This phenomenon was also confirmed by the prediction results of the antiSMASH secondary metabolite gene cluster and the BAGEL4 bacteriocin synthesis gene cluster prediction. The synthetic gene cluster of T3PKS was identified in the antiSMASH database. T3PKS expressed by the gene cluster can assist in the production of polyketides. Polyketides are a class of substances with broad antibacterial, anticancer, antioxidant, antiparasitic and anti-inflammatory activities (Bandgar et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2016; Vogel et al., 2008). Two bacteriocin gene clusters, Enterolysin_A and sakacin_G_skgA1, were detected in the BAGEL4 database. Enterolysin_A gene cluster encodes a cell wall degrading bacteriocin, a class III bacteriocin (Dos Santos et al., 2021; Nilsen et al., 2003). The sakacin G bacteriocin encoded by the sakacin_G_skgA1 gene cluster can lyse sensitive cells, leading to the leakage of enzymes and DNA, thereby inducing apoptosis in bacteria (Todorov et al., 2011). In addition, biochemical experiments and genomic analysis showed that Lactobacillus salivarius S01 had good antibiotic sensitivity. Therefore, L. salivarius S01 show great potential for use in the control of pathogens in aquaculture.

L. salivarius exhibits good resistance to acid and bile salt, adjusting the gut microecological balance by changing the ratio of symbiotic LAB and other bacteria, as well as reducing the gut pH (Chaves et al., 2017; Messaoudi et al., 2013). Meanwhile, L. salivarius has immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-infectious properties (Langa et al., 2012), it also can stimulate Caco-2 cells to inhibit IL-8 production, as well as promote the recovery of gut epithelial cells (Arribas et al., 2012). The tolerance of L. salivarius to acidic conditions plays a key role in its colonization of the intestine, thereby ensuring its probiotic potential. In this study, the results of the in vitro assay in a simulated gastrointestinal juices environment demonstrated that L. salivarius S01 was able to tolerate the extreme conditions of low pH and proteases. Meanwhile, genes associated with probiotic potential, such as environment resistance, adhesion capacity, protective repair of DNA and proteins, and antioxidant immunity, were identified in the genome. Furthermore, previous studies reported that the antioxidant capacity of animals is important because the body tends to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) through normal cellular metabolism and in response to factors such as environmental changes and diet (Sagada et al., 2021). Hepatic antioxidant capacity (e.g., SOD, CAT, and POD) is a way of verifying the health condition and nutritional status of fish, which can regulate the balance between oxidants like ROS and antioxidants to avoid oxidative stress (Birben et al., 2012). Also, MDA is an important product of lipid peroxidation, and the level of MDA is a measure of the degree of oxidative damage (Silambarasan et al., 2019). In this study, diet supplemented with L. salivarius S01 significantly increased the antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, and POD) of S. graham. Meanwhile, the significantly reduced malondialdehyde levels also confirmed the enhanced repair of oxidative damage by the probiotic-induced antioxidant enzyme activity. Thus, L. salivarius S01 was able to enter the intestine and enhance host immunity, which is necessary for probiotics to exert their beneficial effects.

The gut is home to the densest microbial populations of organisms, and plays an important role in many physiological functions, such as host metabolism and nutrition (Devillard et al., 2007). Higher gut microbial diversity provides the host with a higher tolerance to pathogens (Harrison et al., 2019). In this study, the Shannon, Chao1, and Ace indices of the gut microbiome of S. graham were all found to increase after feeding a diet supplemented with L. salivarius, indicating that L. salivarius can promote the gut microbial diversity and richness of the host, consistent with the alterations caused by other LAB as dietary supplements on the host gut microbiota (Ljubobratovic et al., 2017; Lukic et al., 2020). Moreover, previous studies have reported that changes in gut microbiota may be a cause of changes in host immunity (Messaoudi et al., 2013; Chaves et al., 2017; Foysal and Gupta, 2022). In this study, it is important to analyze the changes of specific microbiota in the gut microbiota. At the phylum level, we found that the abundance of the most dominant phylum Proteobacteria decreased after feeding a diet supplemented with L. salivarius. Elevated proportions of proteobacteria in the gut of aquatic animals increase the risk of bacterial infections caused by Eriocheir sinensis and Litopenaeus vannamei (Ding et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019). The relative abundance of Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes increased to different degrees after feeding L. salivarius compared with the control group. Firmicutes can promote the decomposition of fiber and enable the host to obtain nutrition from fibrous feed (Brulc Jennifer et al., 2009). The main role of Bacteroidetes is to degrade carbohydrates (Spence et al., 2006), and the ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes in the animal’s gut reflects the organism’s ability to absorb nutrients. In addition, the main bacteria (including Bacillus, Lactobacillus, and Lactococcus) in the Firmicutes phylum can convert carbohydrates into lactic acid, creating acidic environments, thereby inhibiting pathogens, and protecting the gut (Messaoudi et al., 2013; Chaves et al., 2017; Foysal and Gupta, 2022). Actinobacteria can produce a variety of compounds, including antibiotics, enzymes, enzyme inhibitors, signalling molecules, and immunomodulators (Ul-Hassan and Wellington, 2009). As such, a higher abundance of Actinobacteria in the fish gut can improve food digestion and growth performance in S. grahami. Furthermore, the abundance of potential pathogens Aeromonas in the gut tract of the S. grahami was found to be reduced, while the abundance of the potential beneficial microorganisms Bifidobacterium increased, after feeding with L. salivarius S01 supplements. Aeromonas is a common zoonotic pathogen found in fish that can cause systemic sepsis and local infections (Pereira et al., 2022). On the contrary, Bifidobacterium is an important indicator of good health, with nutritional, anti-tumor, and anti-aging potential, and plays an important role in regulating the balance of gut microbiota and promoting normal gut development (Di Pierro et al., 2020). Unfortunately, corrected p-values show a certain probability of false positive gut microbial results. In addition, correlation analysis showed that Aeromonas was negatively correlated with antioxidant capacity in S. grahami, while Bifidobacterium was positively correlated with antioxidant capacity. Higher levels of hepatic antioxidant enzyme activity and changes in certain gut microorganisms suggested that L. salivarius S01 supplements may reduce the probability of disease by enhancing the immunity of S. grahami against the invasion of external harmful substances. Based on genome-wide data of L. salivarius S01 and the bioinformatic analysis of the gut microbiota of S. grahami, the mechanisms by which L. salivarius S01 promotes host health have been elucidated. These results indicate that L. salivarius can be used as a potential probiotic and an antimicrobial food additive to replace chemical drugs and antibiotics in aquaculture, promoting host health and fostering the development of greener aquaculture practices. However, this study still has some drawbacks, but there are also worthwhile points to be considered.

Conclusion

The results presented in this study demonstrated that the antibacterial activity of L. salivarius S01, previously isolated from the gut tract of S. grahami (Xin et al., 2022), may originate from the antibacterial substances produced by the bacteria, such as T3PKS, Enterolysin_A, and sakacin_G. Biological. Also, L. salivarius S01 showed a better antibiotic sensitivity. Function and genetics analysis related to potential probiotics showed that L. salivarius S01 could cope with the pressure of the natural environment, which may contribute to its colonization in the gut tract. Moreover, diet supplementation with L. salivarius S01 significantly altered the gut microbial diversity and hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities of S. grahami. Using L. salivarius S01 as a diet additive markedly reduced the abundance of potential pathogens and increased the abundance of potential beneficial microorganisms in the gut of S. grahami. Furthermore, supplementation was also found to increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes in the hepar and reduce the incidence of oxidative damage in the host. In summary, this study provides both a theoretical and experimental basis for the application of L. salivarius S01 as potential probiotics in aquaculture.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, CP097639, SRR19351072, SRR19351073, SRR19351074, SRR19351075, SRR19351076, and SRR19351077.

Author contributions

W-GX, X-DL, and Y-CL have carried out the culture and genomic analysis of the bacteria, they conducted the feeding of Sinocyclocheilus grahami and its physiological and biochemical determination, and they also wrote the paper. W-GX, Y-HJ, and M-YX contributed new reagents or analytical tools. Q-LZ, and FW reviewed and revised the manuscript. L-BL has designed the research, provided the reagents and analytical methods and written and revised the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by Yunnan Major Scientific and Technological Projects (grant no. 202202AG050008).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1014970/full#supplementary-material

Histogram of Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis results for the L. salivarius S01 genome.

Histogram of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis results for the L. salivarius S01 genome.

References

- Abd El-Ghany W. A., Abdel-Latif M. A., Hosny F., Alatfeehy N. M., Noreldin A. E., Quesnell R. R., et al. (2022). Comparative efficacy of postbiotic, probiotic, and antibiotic against necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. Poultry Sci. 101:101988. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101988, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter N., Wu B., Memon A. M., Mohsin M. (2015). Probiotics and prebiotics associated with aquaculture: a review. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 45, 733–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.05.038, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas B., Garrido-Mesa N., Perán L., Camuesco D., Comalada M., Bailón E., et al. (2012). The immunomodulatory properties of viable lactobacillus salivarius ssp. salivarius CECT5713 are not restricted to the large intestine. Eur. J. Nutr. 51, 365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00394-011-0221-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandgar B. P., Gawande S. S., Bodade R. G., Totre J. V., Khobragade C. N. (2010). Synthesis and biological evaluation of simple methoxylated chalcones as anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 1364–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.066, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birben E., Sahiner U. M., Sackesen C., Erzurum S., Kalayci O. (2012). Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J. 5, 9–19. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin K., Shaw S., Steinke K., Villebro R., Ziemert N., Lee S. Y., et al. (2019). antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W81–W87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz310, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulc Jennifer M., Antonopoulos Dionysios A., Berg Miller Margret E., Wilson Melissa K., Yannarell Anthony C., Dinsdale Elizabeth A., et al. (2009). Gene-centric metagenomics of the fiber-adherent bovine rumen microbiome reveals forage specific glycoside hydrolases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 1948–1953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806191105, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan A., Singh R. (2019). Probiotics in aquaculture: a promising emerging alternative approach. Symbiosis 77, 99–113. doi: 10.1007/s13199-018-0580-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves B., Brashears M., Nightingale K. (2017). Applications and safety considerations of lactobacillus salivarius as a probiotic in animal and human health. J. Appl. Microbiol. 123, 18–28. doi: 10.1111/jam.13438, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J., Davies D. (2010). Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 417–433. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devillard E., McIntosh F. M., Duncan S. H., Wallace R. J. (2007). Metabolism of linoleic acid by human gut bacteria: different routes for biosynthesis of conjugated linoleic acid. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2566–2570. doi: 10.1128/JB.01359-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pierro F., Bertuccioli A., Saponara M., Ivaldi L. (2020). Impact of a two-bacterial-strain formula, containing Bifidobacterium animalis lactis BB-12 and enterococcus faecium L3, administered before and after therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 66, 117–123. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.19.02651-5, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z. F., Cao M. J., Zhu X. S., Xu G. H., Wang R. L. (2017). Changes in the gut microbiome of the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) in response to white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) infection. J. Fish Dis. 40, 1561–1571. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12624, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Yang Y, Liu J., Awan F., Lu C., Liu Y. (2018). Inhibition of Aeromonas hydrophila-induced intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function damage in crucian carp by oral administration of Lactococcus lactis. Fish Shellfish Immun 83, 359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.041, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos C. I., Campos C. D., Nunes-Neto W. R., Do Carmo M. S., Nogueira F. A., Ferreira R. M., et al. (2021). Genomic analysis of Limosilactobacillus fermentum ATCC 23271, a potential probiotic strain with anti-Candida activity. J Fungi (Basel). 7:794. doi: 10.3390/jof7100794, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foysal M. J., Gupta S. K. (2022). A systematic meta-analysis reveals enrichment of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes in the fish gut in response to black soldier fly (Hermetica illucens) meal-based diets. Aquaculture 549:737760. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giri S., Sukumaran V., Sen S., Jena P. (2014). Effects of dietary supplementation of potential probiotic Bacillus subtilis VSG 1 singularly or in combination with lactobacillus plantarum VSG 3 or/and Pseudomonas aeruginosa VSG 2 on the growth, immunity and disease resistance of Labeo rohita. Aquac. Nutr. 20, 163–171. doi: 10.1111/anu.12062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gopi N., Iswarya A., Vijayakumar S., Jayanthi S., Nor S. A. M., Velusamy P., et al. (2022). Protective effects of dietary supplementation of probiotic bacillus licheniformis Dahb1 against ammonia induced immunotoxicity and oxidative stress in Oreochromis mossambicus. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 259:109379. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109379, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M., Gao T., Liu G., Zhu C., Zhang T., Sun M., et al. (2022). The effect of a polystyrene nanoplastic on the intestinal microbes and oxidative stress defense of the freshwater crayfish. Procambarus clarkii. Sci Total Environ. 833:155722. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155722, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao K., Wu Z. Q., Li D. L., Yu X. B., Wang G. X., Ling F. (2017). Effects of dietary Administration of Shewanella xiamenensis A-1, Aeromonas veronii A-7, and Bacillus subtilis, single or combined, on the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) intestinal microbiota. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 9, 386–396. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9269-7, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison X. A., Price S. J., Hopkins K., Leung W. T. M., Sergeant C., Garner T. W. J. (2019). Diversity-stability dynamics of the amphibian skin microbiome and susceptibility to a lethal viral pathogen. Front. Microbiol. 10:2883. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02883, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinifar S. H., Sun Y. Z., Wang A., Zhou Z. (2018). Probiotics as means of diseases control in aquaculture, a review of current knowledge and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 9:2429. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02429, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S., Kawashima S., Okuno Y., Hattori M. (2004). The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 277D–2280D. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke X., Liu Z., Zhang M., Zhu W., Yi M., Cao J., et al. (2022). A Bacillus cereus NY5 strain from tilapia intestine antagonizes pathogenic Streptococcus agalactiae growth and adhesion in vitro and in vivo. Aquacul. 561:738729. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keter M. T., El Halfawy N. M., El-Naggar M. Y. (2022). Incidence of virulence determinants and antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria isolated from food products. Future Microbiol. 17, 325–337. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2021-0053, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R., Vrbanac A., Taylor B. C., Aksenov A., Callewaert C., Debelius J., et al. (2018). Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 410–422. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0029-9, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa S., Maldonado-Barragán A., Delgado S., Martín R., Martín V., Jiménez E., et al. (2012). Characterization of lactobacillus salivarius CECT 5713, a strain isolated from human milk: from genotype to phenotype. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 94, 1279–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4032-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Hu D., Tian Y., Song Y., Hou Y., Sun L., et al. (2020). Protective effects of a novel lactobacillus rhamnosus strain with probiotic characteristics against lipopolysaccharide-induced gut inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 11, 5799–5814. doi: 10.1039/d0fo00308e, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubobratovic U., Kosanovic D., Vukotic G., Molnar Z., Stanisavljevic N., Ristovic T., et al. (2017). Supplementation of lactobacilli improves growth, regulates microbiota composition and suppresses skeletal anomalies in juvenile pike-perch (Sander lucioperca) reared in recirculating aquaculture system (RAS): a pilot study. Res. Vet. Sci. 115, 451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.07.018, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubobratovic U., Kosanovic D., Demény F. Z., Krajcsovics A., Vukotic G., Stanisavljevic N., et al. (2020). The effect of live and inert feed treatment with lactobacilli on weaning success in intensively reared pike-perch larvae. Aquaculture 516:734608. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukic J., Stanisavljevic N., Vukotic G., Kosanovic D., Terzic-Vidojevic A., Begovic J., et al. (2020). Lactobacillus salivarius BGHO1 and lactobacillus reuteri BGGO6-55 modify nutritive profile of Artemia franciscana nauplii in a strain ratio, dose and application timing-dependent manner. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 259:114356. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane G. T., Macfarlane S. (1997). Human colonic microbiota: ecology, physiology and metabolic potential of gut bacteria. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 222, 3–9. doi: 10.1080/00365521.1997.11720708, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z., Zheng X., Qi Y., Zhang M., Huang Y., Wan C., et al. (2016). Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel hybrid compounds between chalcone and piperazine as potential antitumor agents. RSC Adv. 6, 7723–7727. doi: 10.1039/c5ra20197g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield D., Bradley G., Baker R., Davies S. (2010). Probiotic applications for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum) II. Effects on growth performance, feed utilization, gut microbiota and related health criteria postantibiotic treatment. Aquac. Nutr. 16, 496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2009.00688.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messaoudi S., Manai M., Kergourlay G., Prévost H., Connil N., Chobert J.-M., et al. (2013). Lactobacillus salivarius: bacteriocin and probiotic activity. Food Microbiol. 36, 296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.05.010, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur A. G., Waglechner N., Nizam F., Yan A., Azad M. A., Baylay A. J., et al. (2013). The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingmongkolchai S., Panbangred W. (2018). Bacillus probiotics: an alternative to antibiotics for livestock production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 124, 1334–1346. doi: 10.1111/jam.13690, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen T., Nes I. F., Holo H. (2003). Enterolysin a, a cell wall-degrading bacteriocin from enterococcus faecalis LMG 2333. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 2975–2984. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2975-2984.2003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil V., Barragan E., Patil S. A., Patil S. A., Bugarin A. (2016). Direct synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of structurally complex chalcones. Chemistry Select. 1, 3647–3650. doi: 10.1002/slct.201600703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C., Duarte J., Costa P., Braz M., Almeida A. (2022). Bacteriophages in the control of Aeromonas sp. Aquaculture Systems: An Integrative View. Antibiotics. 11:11020163. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11020163, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringø E. (2020). Probiotics in shellfish aquaculture. Aquacult. Fish 5, 1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2019.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sagada G., Gray N., Wang L., Xu B., Zheng L., Zhong Z., et al. (2021). Effect of dietary inactivated lactobacillus plantarum on growth performance, antioxidative capacity, and intestinal integrity of black sea bream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) fingerlings. Aquacult. 535:736370. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifuzzaman S., Rahman H., Austin D. A., Austin B. (2018). Properties of probiotics Kocuria SM1 and Rhodococcus SM2 isolated from fish guts. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 10, 534–542. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9290-x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silambarasan S., Logeswari P., Cornejo P., Abraham J., Valentine A. (2019). Simultaneous mitigation of aluminum, salinity and drought stress in Lactuca sativa growth via formulated plant growth promoting Rhodotorula mucilaginosa CAM4. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 180, 63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.05.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence C., Wells W. G., Smith C. J. (2006). Characterization of the primary starch utilization operon in the obligate anaerobe Bacteroides fragilis: regulation by carbon source and oxygen. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4663–4672. doi: 10.1128/JB.00125-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Liu M., Tang L., Hu C., Huang Z., Zhou X., et al. (2021). Probiotic supplementation mitigates the developmental toxicity of perfluorobutanesulfonate in zebrafish larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 799:149458. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149458, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpur A. D., Memon A. J., Khan M. I., Ikhwanuddin M., Abdullah M. D. D., Bolong A.-M. A. (2013). Gut lactobacillus sp. bacteria as probiotics for Portunus pelagicus (Linnaeus, 1758) larviculture: effects on survival, digestive enzyme activities and water quality. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 57, 173–184. doi: 10.1080/07924259.2012.714406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., Xiong J., Wang J., Cao Z., Liao S., Xiao Y., et al. (2021). Queen bee larva consumption improves sleep disorder and regulates gut microbiota in mice with PCPA-induced insomnia. Food Biosci. 43:101256. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkhani R., Imani A., Hoseinifar S. H., Sarvi Moghanlou K., Manaffar R. (2020). The effects of host-associated enterococcus faecium CGMCC1.2136 on serum immune parameters, digestive enzymes activity and growth performance of the Caspian roach (Rutilus rutilus caspicus) fingerlings. Aquacult. 519:734741. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R. L., Galperin M. Y., Natale D. A., Koonin E. V. (2000). The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov S. D., Rachman C., Fourrier A., Dicks L. M., Van Reenen C. A., Prévost H., et al. (2011). Characterization of a bacteriocin produced by lactobacillus sakei R1333 isolated from smoked salmon. Anaerobe 17, 23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.01.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran N. T., Zhang J., Xiong F., Wang G. T., Li W. X., Wu S. G. (2018). Altered gut microbiota associated with intestinal disease in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34:71. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2447-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama J., Akiyama M., Hase K., Kumagai Y., Kim Y. G. (2022). Gut microbiota reinforce host antioxidant capacity via the generation of reactive sulfur species. Cell Rep. 38:110479. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110479, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ul-Hassan A., Wellington E. M. (2009). “Actinobacteria” in Encyclopedia of microbiology. ed. Schaechter M.. Third ed (Oxford: Academic Press; ), 25–44. doi: 10.1016/B978-012373944-5.00044-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhoof J. A., Young R. J. (1998). Use of probiotics in childhood Gastrogut disorders. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 27, 323–332. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199809000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseeharan B., Thaya R. (2014). Medicinal plant derivatives as immunostimulants: an alternative to chemotherapeutics and antibiotics in aquaculture. Aquacult Int. 22, 1079–1091. doi: 10.1007/s10499-013-9729-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S., Ohmayer S., Brunner G., Heilmann J. (2008). Natural and non-natural prenylated chalcones: synthesis, cytotoxicity and anti-oxidative activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 4286–4293. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.079, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Huang Y., Xu K., Zhang X., Sun H., Fan L., et al. (2019). White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) infection impacts gut microbiota composition and function in Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 84, 130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.076, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yin L., Zheng W. X., Shi S. J., Hao W. Z., Lui C. G., et al. (2022). Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG normalizes gut dysmotility induced by environmental pollutants via affecting serotonin level in zebrafish larvae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38:222. doi: 10.1007/s11274-022-03409-y, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. L., Liu Z. Y., Li Y. H., Yang L. Y., Yin J., He J. H., et al. (2021). Effects of dietary supplementation of lactobacillus delbrueckii on gut microbiome and intestinal morphology in weaned piglets. Front Vet Sci. 8:692389. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.692389, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017). Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T., Wu Q., Zhang J., Xu X., Cheng J. (2017). Comparison of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from aquatic products and clinical by antibiotic susceptibility, virulence, and molecular characterisation. Food Control 71, 315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.06.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin W. G., Jiang Y. H., Chen S. Y., Xu M. Y., Zhou H. B., Zhang Q. L., et al. (2022). Screening and identification of bacteriocin-producing bacteria in the gut tract of the Sinocyclocheilus grahami and the inhibitory effect of bacteriocin LSP01. Microbiol China. 49, 242–255. doi: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.210290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Liu C., Huang Y., Wu Q., Xiong Y., Yang X., et al. (2022). The responses of lactobacillus reuteri LR1 or antibiotic on intestinal barrier function and microbiota in the cecum of pigs. Front. Microbiol. 13:877297. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.877297, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. X., Pan X. F., Li Z.Y. (2007) Preliminary report on the successful breeding of the endangered fish Sinocyclocheilus grahami endemic to Dianchi Lake. Zool. Res. 28, 329–331. [Google Scholar]

- Yao S., Zhao Z., Wang W., Liu X. (2021). Bifidobacterium Longum: protection against inflammatory bowel disease. J Immunol Res 2021, 8030297–8030211. doi: 10.1155/2021/8030297, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. H., Zhang X. H., Wang X. A., Li R. H., Zhang Y. W., Shan X. X., et al. (2021). Construction of a chromosome-level genome assembly for genome-wide identification of growth-related quantitative trait loci in Sinocyclocheilus grahami (Cypriniformes, Cyprinidae). Zool. Res. 42, 262–266. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.321, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Yu S., Hong B., Li J., Han H., Qie G. (2021). Antibiotics control in aquaculture requires more than antibiotic-free feeds: a tilapia farming case. Environ. Pollut. 268:115854. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115854, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. K., Yang B. T., Hao Z. P., Li H. Z., Cong W., Kang Y. H. (2022). Dietary supplementation with Weissella cibaria C-10 and bacillus amyloliquefaciens T-5 enhance immunity against Aeromonas veronii infection in crucian carp (Carassiu auratus). Microb. Pathog. 167:105559. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105559, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Z. H., Shang B. J., Shao Y. C., Li W. Y., Sun J. S. (2019). Screening of gut probiotics and the effects of feeding probiotics on the growth, immune, digestive enzyme activity and gut flora of Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 86, 160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.11.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Histogram of Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis results for the L. salivarius S01 genome.

Histogram of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis results for the L. salivarius S01 genome.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, CP097639, SRR19351072, SRR19351073, SRR19351074, SRR19351075, SRR19351076, and SRR19351077.