Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of physiotherapeutic intervention to improve the deviated balance of pregnant women.

Method:

A total of 174 subjects were included in the study out of which 62 had postural deviation. They were divided into three groups, two intervention groups and one control group. The target population consisted of women in the antenatal stage, randomly selected from Obstetrics and Gynecology OPD, PGIMER, Chandigarh. The study was conducted over a period of 3 years (2014–2017). They were advised exercises, postural correction, regular walking, and hot water fomentation. Six follow-ups were taken into consideration throughout the pregnancy and postnatal stage.

Result:

The impact of the intervention package on both ante-natal and postnatal women with balance problems showed significant improvement.

Conclusion:

Postural deviations, pain, heaviness in the lower limb, incontinence, breathlessness, etc., are common complaints during and after pregnancy. The problem starts early in pregnancy and increased over time and may persist throughout life if treatment does not start early in the pregnancy. This intervention can be practiced in primary care setting after giving proper training to the health care workers by experienced physiotherapists.

Keywords: Balance problems, physio-therapeutic interventions, post-natal fitness, postural deviation, pregnancy

Introduction

Becoming a mother is a beautiful experience for any woman. Pregnancy, which spans 40 weeks from conception to delivery, brings lots of changes[1] in a mother’s body like increased body weight, rise in abdominal pressure, hyperlordosis which leads to postural deviation, heaviness in the lower limbs, incontinence, low and upper back pain, obesity, depression[2], etc., Although a woman’s body is not fully restored to prepregnant physiology until about 6 months postdelivery, the full restoration of fitness is not always possible, women usually loose the shape of their bodies permanently.[3] Treatments (generally conservative, exercise-based interventions, and alternate modalities) are considered effective to reduce pain and improve fitness.[4] In our country, we do not have the culture to do exercise during pregnancy. Because of this reason, the woman suffers lots of complications in later life which indirectly increases the patients’ count in the hospital. In the modern era, almost every woman wishes to bring back and maintain her shape as it was in the prepregnant state.[5] Some muscle groups that weaken as a result of pregnancy are the pelvic floor, upper back muscles, external rotators of the shoulder, buttocks, front of the neck, and abdominal wall. It leads to adverse health consequences for women in pre and postpartum stages like back pain,[6] coccyx pain,[7] sacroiliac joint pain,[8] leg cramps,[9] postural deviation,[10] incontinence,[11] respiratory disturbance, etc.

After a vaginal delivery, taking good care of the mother is an essential part of postpartum care and maintaining overall fitness.[3] Given the “culture of silence” regarding women’s health that typifies developing countries and the constraints from living conditions; particularly for women, the use of health services by them is naturally less than desirable and is usually delayed.[12] Those who belong to the affluent family will receive good nutrition but maximum women in India are devoid of basic nutrition.[10] Even the women from well to do families do not receive any fitness advice because in India we do not have the basic infrastructure or habit to deliver fitness programs/packages.

Doctors in Obstetrics and Gynecology department are busy delivering basic medical services to save the life of mother and child, they can only advise verbally to do the exercise and precautions, which is hardly followed by the mother.[13] But the participation of women in the work force has increased manifold.[14] So, women also need to go out for her own profession. For this, she needs to keep herself fit. There are many fitness clinics for pre- and postnatal mothers in developed countries like “Be Fit Mom,” “Pre-natal clinic for Mother,” “Post Natal Clinic for New Mother” and many more. But in India, no such special clinics are available, except in very few hospitals. Even there, these are conducted by some highly motivated physicians or physiotherapists.

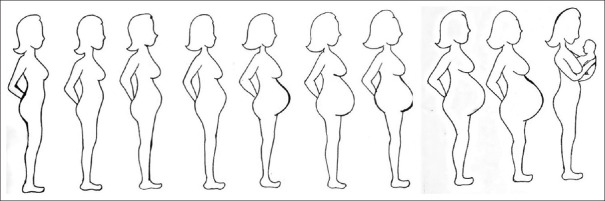

Postural changes are very common problems of women during pregnancy which ultimately causes low back pain [Figure 1].[15] As we know posture is the position in which a person holds the body comfortably while standing, sitting, or lying down. Good posture during pregnancy involves training the body to stand, walk, sit, and lie in positions where the least strain is placed on the back. The growing fetus[16] places added stress on postural muscles as the center of gravity shifts forward and upward, and the spine shifts to compensate and maintain stability,[17] causing enormous strain on the lower back and shifting the center of gravity [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The curvature changes as shown above from 12 weeks (3 months) onward till full-term pregnancy which ultimately causes postural deviation

After delivery, when the abdominal muscles are still weak, women must engage in the repetitive lifting of the baby, often in the forward bend and twisting position.[18] These motions are recognized risk factors for various fitness-related health problems. Postural imbalances are important causative factors of various fitness-related problems during and after pregnancy.[19] Correct standing position, sitting position, and correct positions for stooping, squatting, and kneeling should be demonstrated to the mother in a scientific way.

Forward head posture during standing is also seen in a majority of the patients. This can be related to the habitual posture adopted after delivery as mothers have to breastfeed her baby. During picking up objects from the floor, the mother flexes her head and spine with the hips and knee extended causing excessive stress force on the back.[9] This leads to the shortening of upper cervical extensors and lower cervical flexors muscles. This can be corrected by some simple exercises such as stretching and strengthening of neck muscles.[10]

So, the exercises and postural education in pregnant women is necessary both in the prevention of fitness-related problems as well as management of pain due to postural imbalance in the prenatal and postnatal period. It is known that exercising and taking various precautions about posture would seem to be important in addressing fitness-related health issues of pregnancy and postpartum period to reduce the long-term morbidity of women.[20]

Methodology

The study was conducted in the Department of Physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) (Physiotherapy) in collaboration with the gynecology department of PGIMER, Chandigarh. Pregnant and postnatal women were asked about various types of fitness-related issues. They were also asked about care and precautions taken by them pertaining to fitness during pregnancy and lactation. A proforma was designed for ascertaining these issues.

Scoring was done for existing practices of the respondents regarding their posture (sitting/standing/lying) and daily activities (mopping/brooming/doing utensils/washing clothes/picking up things from the floor). Customized corrections were advised as per the study intervention protocol.

Study design

Three group RCT (Randomized Controlled Trial).

Sample size

A total of 64 subjects were included in the study and divided into three groups.

Study site

PRM (Physiotherapy) department, PGIMER, Chandigarh.

Study population

The target population consisted of women in the ante and postnatal stage, randomly selected from Obstetrics and Gynecology OPD, PGIMER, Chandigarh.

Study period

The study was conducted in PGIMER over a period of 4 years (2014–2018).

Inclusion criteria

Women in prenatal (from 2nd trimester onward) and postnatal stage (till 6 months).

Exclusion criteria

Severe cardiopulmonary disorder,

Any psychological abnormalities,

Active vaginal bleeding,

Any type of infection,

STD, HIV + women,

Vaginal fistula,

Spinal cord injury,

Threatened abortion or recurrent miscarriage,

Previous premature births or history of early labor.

Intervention package components

Visit schedule of subjects

Visit schedule of the subjects was as per Table 1.

Table 1.

Visit schedule

| Gestation period | Visit no. | Activities related to RCT |

|---|---|---|

| 12-20 weeks | 1 | Registration, Group allocation, intervention, Demonstration of exercises as per intervention packages |

| 24-28 weeks | 2 | Follow up, retraining, correction of posture, etc. |

| 28-32 weeks | 3 | Follow up, retraining, postural adjustments and correction, different types of precautions, etc. |

| 36 weeks till delivery | 4 | Follow up, precautions, concentrate on breathing exercise |

| Postnatal 1-30 days | 5 | Follow up, look after the complications, training according to complications, breathing exercise, pelvic floor muscles exercise |

| 6-12 weeks | 6 | Training including exercise therapy delivered according to tolerance and improvement of the subject, breathing exercise, generalized stretching, and Kegel’s exercise. Walking as tolerated and massage. Electrotherapy modalities were applied as per requirements. |

| 12-20 weeks& onward | 7 | Previous exercise with increased timing + low-level aerobics and strengthening exercise+Electrotherapy modalities |

General education

This session included all the changes that occur during pregnancy, their effects on physiological and mechanical changes in the body, and how to correct them during pregnancy.[21] The patients were given guidelines before engaging in an exercise program. The package had instructions on the methods to do prenatal and postnatal exercises. Information on postural care was also explained.

Exercises

An introductory session was held by the researcher on the first visit of subjects (pre- and postnatal both). It lasted for about 5 to 10 min. All the females (ANC/PNC) were divided into three groups according to the package prepared. The exercise session lasted for 20–30 minaccording to the requirements and tolerance of the subjects. There were 5 min warm-up, 10–20 min’ exercise session including breathing exercises. It ended with 5 min cool-down session.

The warm-up session included a full range of motion (ROM) exercise of both upper limbs and lower limbs, neck ROM, low and medium speed walking with a breathing exercise.

Exercises included in the training package were as follows:

Active foot and ankle exercise,

Stretching exercises of adductor (tailor press) and other tight structures,

Lightweight training for sportswomen,

Strengthening exercise,

Isometric back, neck, and abdominal muscle exercise,

Pelvic bridging exercise,

Cat and camel exercise,

4-point kneeling - arm lift and leg extension,

Side leg raisers/leg lifts/hip abduction,

Balance and coordination training

Postural care and ergonomic advice,

Breathing exercise.

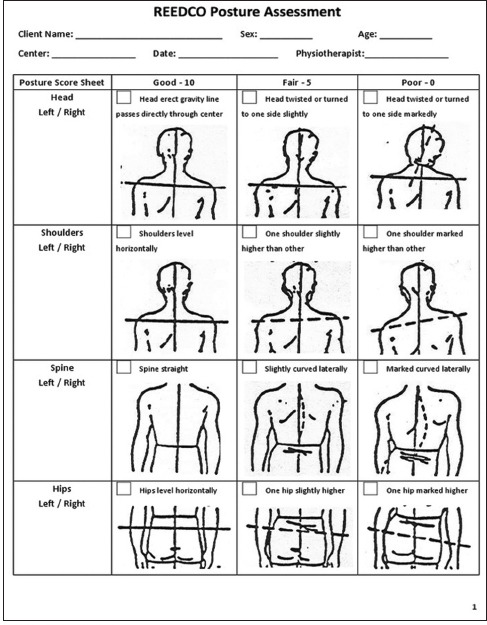

Postural assessment and management

Postural changes were evaluated on the basis of REEDCO scale [Annexure 1], and changes were documented. Based on the changes, training was imparted to the participants.

Study component/grouping of the subjects

The participants were encouraged to comply with the instructions pertaining to various components of the intervention package. In the therapeutic intervention package, i.e. Group A was provided with the brochure containing exercise demonstration, postural advice, dietary advice, mobile-based feedback, and practical demonstration of the exercise. Group B was provided exercise demonstration on the first t visit only and a brochure to practice at home (home management program). In the case of group C, the subjects were received only routine conventional management.

Follow-up of all the groups was done as per the enclosed schedule. A reminder was given to patients who did not turn up on a scheduled follow-up visit. During the hospital-based sessions, the participants of all the groups were instructed to continue the set of interventions at home also. The participants were asked to maintain a logbook (a basic exercise chart has been included in the backside of the booklet) to keep a record of the compliance with all the intervention packages. Feedback was taken from these logbooks at each follow-up visit. During the follow-up visit, the patients were asked about the degree of relief of their symptoms.

Adverse events, whenever found, resulting from any component of the intervention package were duly recorded. These were also reported to the institute’s ethics committee. The packages were discussed with the consulting OBG expert from time to time or as per requirements.

Postural correction and exercise[9,10]

Special management procedure was taken into consideration to resolve the balance problems as follows: -

Correct way to stand [Picture 1]

Picture 1.

Correct standing posture

Hold your head up straight with your chin in. Do not tilt your head forward, backward, or sideways.

Make sure your ear lobes are in line with the middle of your shoulders.

Keep your shoulder blades back and your chest forward.

Keep your knees straight, but not locked.

Tighten your abdomen, pulling it in and up when you are able. Do not tilt your pelvis forward or backward. Keep your buttocks tucked in when you are able.

Point your feet in the same direction, with your weight balanced evenly on both feet. May use arch-supported low heeled shoes.

Avoid standing in the same position for a long time.

Adjust the height of the work table to a comfortable level. Try to elevate one foot by resting it on a stool or box. After several minutes, switch your foot position.

While working in the kitchen change feet every 5 to 15 min, may use a low height stool.

Correct way to sit [Picture 2]

Picture 2.

Correct sitting position

Sit with your back straight and your shoulders back. Your buttocks should touch the back of your chair.

Sit with back support (such as a small, rolled-up towel or a lumbar roll) placed at the hollow of your back. Try to avoid sitting in the same position for more than 30 min.

Correct way to stand up [Picture 1]

Distribute your body weight evenly on both hips.

Use a footrest or stool if necessary. Your legs should not be crossed, and your feet should be flat on the floor.

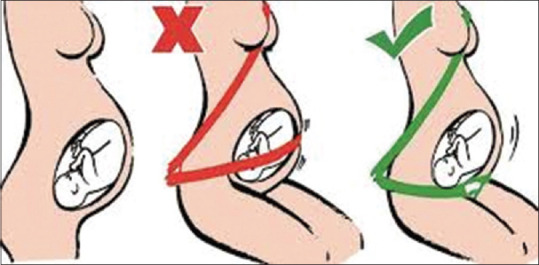

Correct driving position [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Correct sitting posture during driving

Use a back support (lumbar roll) at the curve of your back. Your knees should be at the same level as your hips.

Move the seat close to the steering wheel to support the curve of your back. The seat should be close enough to allow your knees to bend and your feet to reach the pedals.

Always wear both lap and shoulder safety belts. Place the lap belt under the abdomen, as low on hips as possible, and across upper thighs. Never place the belt above the abdomen. Place the shoulder belt between the breasts. Adjust the shoulder and lap belts as snug as possible.

If a vehicle is equipped with an airbag, it is very important to wear shoulder and lap belts. In addition, always sit back at least 10 inches away from the site where the airbag is stored. When driving, pregnant women should adjust the steering wheel so it is tilted toward the chest and away from the head and abdomen.

Result

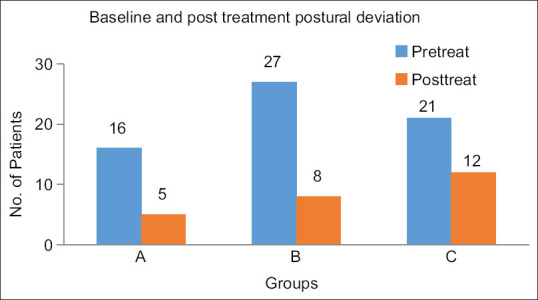

Out of total of 174 subjects, 64 subjects had postural deviation during antenatal stage. Out of these 64 subjects, 16 were in GroupA, 27 in GroupB, and the remaining 21 in GroupC were having postural deviation. The treatment package was delivered to them, and they showed the resulting group-wise as per the Table 2. Group-wise and severity-wise problem breakup of the postural deviation are given in the table at the baseline and till sixth follow-up stages. All the subjects registered in this condition were in the ante-natal stage.

Table 2.

Presence of postural deviation (gradation criteria: - normal=0, mild=1, moderate=2, severe=3, as per REEDCO Scale):- Ante-natal:- Group-A, (no 16)

| VAS score | Baseline | FU1 | FU2 | FU3 | FU4 | FU5 | FU6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 6 | 11 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | - |

| 3 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | - | - |

Fisher Exact test was applied for in-between pair of groups and in-between three groups from the baseline and up to sixth follow up. Following observation has been found after application of the test and comparison done, and the result was found as follows:-

Baseline Gr.A/Gr.B/Gr.C (P value) =0.6222

Visit-wise comparison of follow-ups of each group arein the Tables 3-8, and the result was obtained. Comparison of follow-ups in between groups are also found in the tables.

Table 3.

Presence of postural deviation (gradation criteria: - normal=0, mild=1, moderate=2, severe=3 as per REEDCO Scale) Ante-natal:- Group-B (no. 27)

| VAS score | Baseline | FU1 | FU2 | FU3 | FU4 | FU5 | FU6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 19 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| 2 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 3 |

| 3 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 10 | 2 |

Table 8.

Group-C, comparison of follow ups

| Baseline/FU1 (P) | FU1/FU2 (P) | FU2/FU3 (P) | FU3/FU4 (P) | FU4/FU5 (P) | FU5/FU6 (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.17342 | 0.15174 | 0.07943 | 0.09947 | 0.03936 | 0.00846 |

Table 4.

Presence of postural deviation (gradation criteria: normal=0, mild=1, moderate=2, severe=3 as per REEDCO Scale), Ante-natal stage:- Group-C (no. 21)

| VAS score | Baseline | FU1 | FU2 | FU3 | FU4 | FU5 | FU6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 |

| 3 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 4 |

Table 5.

Comparison of follow ups in-between groups

| Ante-natal stage | Baseline (P) | FU1 (P) | FU2 (P) | FU3 (P) | FU4 (P) | FU5 (P) | FU6 (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gr.A/Gr.B | 0.07478 | 0.05394 | 0.06628 | 0.03837 | 0.00251 | 0.0195 | 0.0019 |

| Gr.A/Gr.C | 0.0688 | 0.00968 | 0.00861 | 0.01998 | 0.00127 | 0.00284 | 0.00026 |

| Gr.B/Gr.C | 0.09247 | 0.02991 | 0.0.02669 | 0.07198 | 0.07417 | 0.04445 | 0.00000 |

Table 6.

Group-A, comparison of follow ups

| Baseline/FU1 (P) | FU1/FU2 (P) | FU2/FU3 (P) | FU3/FU4 (P) | FU4/FU5 (P) | FU5/FU6 (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.06406 | 0.11023 | 0.09892 | 0.0777 | 0.02611 | 0.00618 |

Table 7.

Group-B, comparison of follow ups

| Baseline/FU1 P) | FU1/FU2 (P) | FU2/FU3 (P) | FU3/FU4 (P) | FU4/FU5 (P) | FU5/FU6 (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.08111 | 0.07904 | 0.07268 | 0.07269 | 0.00265 | 0.0000 |

Tables show the breakup of postural deviation cases for each group at the antenatal and post-natal stages. For comparing the group-wise improvement, we must look at each group at every follow-up stage. We found that at each follow-up stage, the subjects have been cured of the problem. The rate at which the problem has been cured is faster in Group A than in Group B. The rate has been faster in Group A than Group C also. It can also be seen that cases of GroupB have been cured at a better rate than the cases of Group C.

The situation described in the above paragraphs about the benefit of the intervention cannot be said with confidence as the probability value shows the improvement as per the table value. Sometimes the frequencies are so small that obtaining the result as per the P value is concerned is not possible. But the rate of improvement, which is showing gradually in the frequency tables, is very much clear that the impact of the intervention package was very much positive as per our objective. In maximum time, the improvement started showing from the third and fourth visit onward which continued till the sixth follow up. So, it can be concluded that the intervention package which was prepared for group-A was the better one in comparison to the other ones.

Discussion

Pregnancy is the most crucial part of one’s life. In the first trimester, women may face problems like morning sickness, which restricts them from any kind of activity in the earlier stage. In the second and third trimester, with the increased weight and growth of the fetus various fitness-related health issues emerge. The severity of fitness-related issues increases as the pregnancy advances. After delivering a child, a lot of changes occur in a women’s body.[22] The pelvic organs take 6 months to come back to the prepregnant stage. Various postural changes also occur. In this stage also, the woman must take dual care of herself as well as her child. Earlier in the system of joint family, women did not face much problem as other women in the family would do all household work, and pregnant women were able to take care of themselves and their children.

Treatment package was delivered to them, and the result is shown group-wise as per the table and Figure 3. Group-wise and severity-wise problem breakup of the postural deviation are shown at the baseline and till sixth follow-up stages. All the subjects registered in this condition were in the antenatal stage. It was found after the intervention that the improvement was much better in Group-A in comparison to the other two groups.

Figure 3.

Status of postural deviation

Nowadays most women are working during pregnancy time. Various health issues related to pregnancy pose threat to their fitness and as a result, they must face problems in their professional life also. Some women are forced to leave or change their profession just because of lack of fitness or problems related to pregnancy.[23]

This situation compromises the quality of care and leaves them dissatisfied with the services which may complicate the health situation very badly in the long run. This problem can be rectified by creating a collaborative management system between doctors and physiotherapists. Many of fitness-related health problems can be resolved by nonmedicinal interventions and self-care with the help of physiotherapy.[24] The major hindrance in this regard is that consulting a physiotherapist has not become an “in thing” for women in India. Even there is not much dialogue between OBG experts and physiotherapists till date. For routine antenatal and postnatal checkups, women consult OBG experts only. They do not get to see physiotherapists as a routine system. In some parts of India, the OBG-Physiotherapy collaboration has been started for pre and postnatal women. But it is available in a few cities only and not for the common people, and in a rural area, it is a matter of dream only.

It has been documented those conservative measures like physiotherapy[25] can easily prevent and even cure many fitness-related problems of antenatal and postnatal women which are found in the present study also. It was found that prenatal and postnatal women’s capacity for standing, walking, and sitting diminished. Their daily activities were affected as the majority of women found difficulty in moving due to fitness-related health issues. A total of 78% prenatal and 61% postnatal women reported difficulty in moving themselves. A study on activities of daily living[26] acknowledged that fitness problems of prenatal and postnatal women led to disabling pain and interfered with activities of daily living (ADL).

During pregnancy, there is an enormous strain on the lower back because of increasing lumbar lordosis[27] loss of abdominal muscle support, and a rise in the body’s center of gravity. After delivery, when the abdominal muscles are still weak, women have to engage in the repetitive lifting of the baby, often in the forward bend and twisting position for taking care and for breastfeed. These motions are recognized risk factors for various fitness-related health problems. Postural imbalances are an important causative factor of various fitness-related problems during and after pregnancy. Correct standing position, sitting position, and correct positions for stooping, squatting, and kneeling were demonstrated to the participants. Lumbar or pelvic support belts are frequently recommended for the prevention and treatment of low back pain during pregnancy. Maternity support belts belong to one of the types of maternity support garments, which are widely used during pregnancy. The potential stabilization effect of maternity support belt was demonstrated in some studies. No such adverse effects were reported in this study other than minimum skin irritation.

Analysis of sitting and standing posture revealed that kyphosis was seen in all patients. This can be related to the habitual and important posture adopted after delivery as mothers have to breastfeed the baby. The thoracic spine is built for stability, which plays an important role in holding the body upright during standing and sitting.[8] Forward head posture during standing was seen in the majority of the mother during pregnancy. During picking up of objects from the floor, all the patients flexed their head and spine with the hips and knee extended causing excessive stress force on the upper and lower back.

The main cause of forwarding head posture in the human being is slouched posture. This can be corrected by some simple exercises and awareness. These include stretching of the muscles of the neck. This leads to the shortening of upper cervical extensors and lower cervical flexors muscles and muscles around the shoulder joint. In this study, it has also found that out of 156 ante-natal subjects, 64 had postural deviation as per the REEDCO scale [Annexure 1]. After the implementation of the intervention package on both the groups, their complications were relieved a lot. But the rate of improvement was better in Group A in comparison to Group B. The improvement was very slow in the case of Group C.

Postural imbalances are an important causative factor of various fitness-related problems during and after pregnancy. In the postural assessment, in this present study, 64 subjects had a postural problem. While sitting, the position of the head was not correct in most respondents. The position of the spine was not correct in most prenatal women. The increased body weight is directly related to postural changes in the thoracic and abdominal regions. With the increase in weight during pregnancy, the abdominal muscles are stretched, there is a protuberance of the uterus anteriorly, and the line of gravity is shifted forward. To maintain her balance, the woman stands further back on her heels and increases the width of her base. This accentuates the lordosis in the lumbar spine, causing the pelvis to tilt at a more acute angle to the vertebral column which results in various physical problems.

Analysis of sitting and standing posture revealed that kyphosis was seen in many subjects. This can be related to the habitual posture adopted after delivery as mothers have to breastfeed. The thoracic spine is built for stability, which plays an important role in holding the body upright during standing and sitting. Forward head posture during standing was seen in the majority of them. During picking up objects from the floor, all the patients flexed their head and spine with the hips and knee extended causing excessive stress force on the back.

So, in conclusion, it is to say that exercises and postural education in pregnant women are necessary both in the prevention of fitness-related problems as well as management of pain due to postural imbalance in the prenatal and postnatal period. It is known that exercising and taking various precautions about posture would seem to be important in addressing fitness-related health issues of pregnancy and postpartum period to reduce the long-term morbidity of maternal health. This has a definite implication in improving the quality of prenatal and postnatal women care in a hospital setting through the collaboration of physiotherapists with obstetrics and gsynecology experts. This intervention can be practiced in primary care setting after giving proper training to the health care workers by experienced physiotherapists.

Consent

Informed consent was taken from the participants

Ethical clearance

Taken from institute ethical committee

Ethics approval

Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI) Reg. No. REF/2015/06/009144.

PGI ethical committee no. INT/IEC/2015/293

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Annexure 1

REEDCO Scale for postural assessment

References

- 1.Kumar P, Magon N. Hormones in pregnancy. Niger Med J. 2012;53:179–83. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.107549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LJ. Postpartum depression. JAMA. 2002;287:762–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gjerdingen D, Fontaine P, Crow S, McGovern P, Center B, Miner M. Predictors of mothers'postpartum body dissatisfaction. Women Health. 2009;49:491–504. doi: 10.1080/03630240903423998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melzer K, Schutz Y, Boulvain M, Kayser B. Physical activity and pregnancy:cardiovascular adaptations, recommendations and pregnancy outcomes. Sports Med. 2010;40:493–507. doi: 10.2165/11532290-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inanir A, Cakmak B, Hisim Y, Dimirturk F. Evaluation of postural equilibrium and fall risk during pregnancy. Gait Posture. 2014;39:1122–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clap JF. Exercise during pregnancy. A clinical update. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:273–86. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastiaansen JM, DeBaie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Essed GG, Van den Barandt PA. A historical perspective on pregnancy-related low back pain and/or pelvic pain. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schröder G, Kundt G, Otte M, Wendig D, Schober HC. Impact of pregnancy on back pain and body posture in women. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28:1199–207. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin ME, Conner K. An analysis of posture and back pain in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:133–8. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.3.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar PK, Singh P, Singh A, Dhillon MS, Suri V. Pregnancy and Motherhood:Safe exercise for Fitness. ISBN. 978-81-290-019-5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorr HG, Heller A, Versmold HT. Longitudinal study of progestins, mineralocorticoids, and glucocorticoids throughout human pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1989;68:863–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem-68-5-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller RD, Wasserhiet J. The Culture of Silence:Reproductive Tract Infections among Women in the Third World. New York: International Women's Health Coalition; 1991. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard D. Aspects of maternal morbidity:The experience of less developed countries. Adv Intention Matern Child Health. 1985;7:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salihu HM, Myers J, August EM. Pregnancy in the workplace. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62:88–97. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqr198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena AK, Chilkoti GT, Singh A, Yadav G. Pregnancy-induced Low Back Pain in Indian Women:Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Correlation with Serum Calcium Levels. Anesth Essays Res. 2019;13:395–402. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_196_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gileard WL, Crosbie J, Smith R. Static trunk posture in sitting and standing during pregnancy and early postpartum. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1739–44. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitcome KK, Shapiro LJ, Lieberman DE. Fetal load and the evolution of lumbar lordosis in bipedal hominins. Nature. 2007;450:1075–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casey BM, Schaffer JI, Bloom SL, Heartwell SF, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Obstetric antecedents for postpartum pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunning K, LeMasters G, Levin L, Bhattacherya A, Alterman T, Lordo K. Falls in workers during pregnancy:Risk factors, job hazards, and high-risk occupations. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:664–72. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards E, VanKessel G, Virgara R, Harris P. Does antenatal physical therapy for pregnant women with low back pain or pelvic pain improve functional outcomes?A systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:1038–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACOG Committee Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion, No 267, Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:171–3. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snooks SJ, Setchell M, Swash M, Henry MM. Injury to innervation of pelvic floor sphincter musculature in childbirth. Lancet. 1984;2:546–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou K, West HM, Zhang J, Xu L, Li W. Interventions for leg cramps in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:CD010655. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010655.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahishale AV, Maria Vlorica LPA, Patil HS. Effect of postnatal exercise on the quality of immediate postpartum mothers. A clinical trial. J South Asian Fed Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;6:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajasekhar H, Sumanlata P. Physiotherapy exercises during antenatal and postnatal period. Int J Physiother. 2015;2:745–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albert HB, Godskesen M, Westergaard JG. Incidence of four syndromes of pregnancy related pelvic joint pain. Spine. 2002;27:2831–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoo H, Shin D, Song C. Changes in the spinal curvature, degree of pain, balance ability, and gait ability according to pregnancy period in pregnant and non-pregnant women. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:279–84. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]