Abstract

Context:

Dengue is one of the most extensively spread mosquito borne disease. Puducherry has experienced outbreaks during the post monsoon season almost every year since 2003. Understanding the dynamics of disease transmission and the conducive factors favourable for its spread is necessary to plan early control measures to prevent outbreaks.

Objective:

To describe the sociodemographic details of the dengue recovered cases, their clinical features, management, probable sociobehavioural and environmental risk factors for acquiring infection that could favour disease spread.

Methodology:

An exploratory descriptive study was conducted among 23 individuals recovered from dengue during the outbreak in Puducherry in 2018. An interview guide was used to elicit details regarding the course of illness from its onset until recovery as well as the probable sociobehavioural and environmental risk factors from each participant. Descriptive statistics were reported as frequency, percentage, and mean scores.

Results:

All 23 were primary cases of dengue with fever and myalgia being the commonest presentation. Two of them developed dengue haemorrhagic fever, of which one completely recovered. Five were found to have dengue–chikungunya coinfection. Lack of awareness about dengue, noncompliance regarding proper solid waste management and environmental sanitation among the public was clearly evident.

Conclusion:

Local transmission was evident as most cases did not have any relevant travel history outside the State and from the prevailing mosquitogenic environmental conditions. Dengue being a preventable disease can be controlled only with the active participation of all stakeholders including primary care physicians and the community.

Keywords: Dengue, environmental risk factors, prevention, sociobehavioural

Introduction

Dengue is one of the most extensively spread arboviral disease transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Globally, about 390 million infections occur annually of which 96 million manifest clinically.[1,2] In India, 35 states/UTs except Lakshadweep have reported dengue cases in the last two decades, and the epidemics are more frequently observed lately.[3,4] All four dengue serotypes (DENV 1–4) have been reported; however, secondary infections with DENV-2, -3, and -4 were likely to result in severe forms like dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome.[5] A recent study found the sero-prevalence of DENV infection in India at 48·7% with the southern and western regions recording as high as 76.9 and 62.3% respectively. DENV-1 and DENV-2 were the predominant serotypes in northern and eastern regions, while it was DENV-3, DENV-2, and DENV-1 in western and southern regions.[6,7]

The transmission of dengue viral disease depends on interaction between several macro and micro elements that includes biological, ecological and sociobehavioural factors.[8] The disease which was once restricted to urban areas has now extensively spread to semiurban and rural areas. This is mainly due to the rapid proliferation of vector breeding sites in these areas owing to unplanned urbanization, poor environmental sanitation, inadequate water and solid waste management favouring dengue virus transmission.[3,4,9] With an increase in frequency of transportation and ease of travel, the rapid spread of dengue to other regions is imminent.[10]

Puducherry, a small coastal town in south India, experiences a hot and humid climate almost throughout the year with an average temperature varying between 26 and 38°C.[11] Although transmission is perennial, the peak number of dengue cases is usually reported from the month of September to December coinciding with the rainy season in this region. Literature reveals that the first dengue outbreak was reported in Puducherry in the year 2003.[12] Since then, outbreaks are occurring regularly in Puducherry with the number of cases increasing every year. In 2017, 4568 dengue cases were reported of which seven proved fatal.[13] Considering about 80% of the dengue cases are usually asymptomatic, the actual burden of dengue could be several folds higher than reported.[14] Understanding the dynamics of disease transmission and conducive factors favouring its spread is necessary to plan and implement early control measures to prevent any impending outbreaks. An exploratory descriptive follow-up of dengue recovered cases (interviewed retrospectively) was conducted in Puducherry during the month of October–November 2018 in an attempt to describe the sociodemographic details of the cases, their clinical features, management, probable socio-behavioural and environmental risk factors for acquiring infection that could favour further spread of disease in the community.

Methodology

A list of 67 laboratory confirmed dengue positive cases reported from 1 September 2018 to 3 October 2018 with contact details was obtained from NVBDCP, Puducherry. Of these, 35 cases located in different areas in Puducherry were visited by a two-member team for 2 days in a week between 15 October and 26 November 2018. However, actual contact could be established with only 23 cases as many addresses were either incomplete or incorrect, or door was found locked or at times locating the house was difficult. An experienced sociologist explained the purpose of the visit to participants or their parent in case of children and obtained their oral consent. Using an interview guide, the interviewer elicited details regarding the course of illness, expenses incurred during treatment, probable sociobehavioural and environmental risk factors from each participant. Screening for the presence of mosquito breeding sources in and around the houses and immediate neighbourhood was done to find out potential environmental risk factors. The environmental sanitation within and outside the houses of cases was graded as ‘poor’ or ‘fair’ based on the solid waste disposal practices observed. Health education on dengue fever, its prevention and control was given to the family following the interview. Also, the families were informed about the risk of reinfection with a different serotype that may at times be fatal and stressed on the need for following all precautionary measures against mosquito bites and to timely report any fever to health authorities. A medical doctor ascertained the dengue positivity status of each of the cases by verifying with the clinical history for symptoms as per WHO guidelines,[2] laboratory reports (serological tests for dengue NS1Ag, dengue specific IgM and IgG antibodies) or discharge summary if available with the cases. We defined a primary case of dengue as one who is positive for NS1Ag and dengue-specific IgM while negative for IgG with no past history of dengue fever. The study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC-1021/N/A). The results were expressed as simple proportions and no other rigorous statistical analysis was carried out in view of the small number of cases.

Results

A total of 23 dengue recovered individuals comprising of 12 males (52.2%) and 11 females (47.8%), were interviewed retrospectively. In total, 10 (43.5%) individuals were from rural areas and 13 (56.5%) were from urban areas of Puducherry. The sociodemographic details of the individuals are described in Table 1. The monthly family income of the households ranged between Rs. 3000 and Rs. 95,000. Almost 21 (91.3%) houses had concrete roofing except 2 (8.7%) which were tiled. None of the households had the habit of storing water in open buckets and containers as they had frequent supply of water.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details of cases (n=23)

| Age composition (range: 13-80 years, mean: 36.7±21.7 years) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| n (%) | |

| Age group (years) | |

| 13-20 | 9 (39.1) |

| 21-30 | 2 (8.7) |

| 31-40 | 4 (17.4) |

| 41-50 | 4 (17.4) |

| Above 50 | 4 (17.4) |

| Educational status | |

| Primary | 2 (8.7) |

| Middle school | 5 (21.7) |

| High school | 5 (21.7) |

| Intermediate | 7 (30.4) |

| Graduate | 4 (17.4) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 3 (13) |

| Employed | 7 (30.4) |

| Student | 8 (34.8) |

| Homemaker | 4 (17.4) |

| Retired | 1 (4.3) |

| Socioeconomic status by BG Prasad scale[15] | |

| Class 1 Upper | 4 (17.4) |

| Class 2 Upper middle | 4 (17.4) |

| Class 3 Lower middle | 6 (26.1) |

| Class 4 Upper lower | 6 (26.1) |

| Class 5 Lower | 3 (13) |

Clinical profile of cases

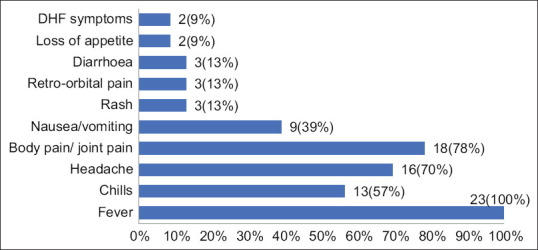

All 23 were primary cases of dengue spread across urban and rural areas in Puducherry. Fever was the commonest presentation with duration range between 2 and 7 days. Body pain, joint pain and headache were the other chiefly reported symptoms. Rash and retro-orbital pain were reported by only three cases [Figure 1]. Eighteen cases had the onset of fever between 28 August 2018 and 1 October 2018. The remaining five cases (Cases 19–23) hailed from a single street and had onset of fever between 4 November 2018 and 22 November 2018. All the cases had either consulted a local medical practitioner or visited nearby primary health centre who later referred them to Government hospital for further management. Majority cases, 20 (87%), were treated as inpatients requiring a minimum stay of 5 days in the hospital, while 3 were treated as outpatients. The cases were treated symptomatically with antipyretic drugs. Almost all the cases, 19 (82.6%), received intravenous fluids. Three cases (Cases 2, 11, 21) including the two DHF cases received platelet transfusion due to low platelet counts. Whole blood transfusion was also given for the two DHF cases of which one later died. Duration of illness, that is, onset of illness till complete recovery ranged between 5 and 30 days (mean 12.5 ± 6 days). Work days or school/college days lost ranged between 3 and 30 days. Expenses towards consultation fee to local medical practitioners, laboratory investigations, medicines, travel, etc., ranged between Rs. 900 and Rs. 7000.

Figure 1.

Reported symptoms of dengue

Comorbid conditions such as hypertension, type II diabetes mellitus, asthma, hypercholesterolemia and depression were reported by 8 (34.8%) cases. All cases recovered except an 80-year-old male [Case 11 in Table 2], a known asthmatic, developed sudden onset of fever with altered sensorium and loss of consciousness, for which he was admitted and treated in an intensive care unit of government hospital; subsequently, he was diagnosed to have developed DHF. He later died due to respiratory failure following hospitalization for 20 days. The other case of DHF who later recovered was a 46-year-old male (Case 2) who reported high-grade fever for 3 days for which he received treatment in a private clinic and later was referred and admitted in a government hospital as he developed dizziness, vomiting, abdominal pain and passing of black stools. He recovered completely with hospital care for 10 days which included administration of intravenous fluids, platelets and blood transfusion besides antipyretic drugs.

Table 2.

Most probable risk factors identified among the cases

| Case no. | Age | Sex | Area in Puducherry | Type of area | Occupation | Date of onset of fever | Time between onset of symptom and reporting to health facility (days) | Travel to endemic area within 10 days prior to onset of fever (local areas and outside Puducherry) | Presence of dengue cases in family/locality | Self-reported probable exposure to mosquito bites at | Environmental sanitation | Preventive practices followed to prevent dengue (multiple responses) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Work place | School/college/play ground | Within house | Outside house | |||||||||||

| Case 1 | 39 | F | Kirumambakkam | Rural | Homemaker | 28/9/18 | 3 | - | yes | - | - | fair | poor | Used fan to prevent mosquito bites |

| Case 2* | 46 | M | Seliamedu | Rural | Milk vendor | 18/9/18 | 1 | Stayed in Chennai | - | yes | - | fair | poor | Used fan and screening of doors/windows |

| Case 3# | 18 | M | Pillayarkuppam | Rural | Unemployed | 28/9/18 | 2 | - | yes | - | yes | poor | poor | Used fan |

| Case 4# | 50 | F | Pillayarkuppam | Rural | Homemaker | 17/9/18 | 3 | - | yes | - | - | poor | poor | Used fan |

| Case 5# | 17 | F | Pillayarkuppam | Rural | Student | 30/9/18 | 1 | - | yes | - | - | fair | poor | Repellents |

| Case 6 | 48 | M | Vadamangalam | Rural | Electrician | 30/9/18 | 1 | - | yes | yes | - | fair | fair | Repellents, neem smoke, avoided water collections |

| Case 7# | 45 | M | Thirukkanur | Rural | Shop owner | 27/9/18 | 3 | - | - | yes | - | fair | poor | Repellents, screening of doors/windows, avoided water collections |

| Case 8# | 40 | F | Pillayarkuppam | Rural | Homemaker | 16/9/18 | 2 | - | yes | - | - | poor | poor | Repellents |

| Case 9 | 14 | F | Kottaimedu | Urban | Student | 1/10/18 | 2 | - | - | - | yes | fair | fair | Repellents, avoided water collections |

| Case 10 | 21 | F | Arumanthapuram | Urban | Homemaker | 10/9/18 | 3 | Pillayarkuppam | yes | - | - | poor | poor | Repellents |

| Case 11* | 80 | M | Morrison thottam | Urban | Retired | 31/8/18 | 1 | Spent time in church | - | - | - | fair | fair | Repellents |

| Case 12 | 80 | F | Mudaliyarpet | Urban | Shop owner | 09/9/18 | 2 | Spent time in temple and shop | - | yes | - | fair | fair | Repellents, screening of doors/windows |

| Case 13 | 73 | M | Karamanikuppam | Urban | Retired | 01/9/18 | 3 | - | - | - | - | fair | poor | Used fan |

| Case 14 | 37 | M | Murungapakkam | Urban | Teacher | 23/9/18 | 2 | Stayed in Chennai | - | - | - | fair | poor | Repellents |

| Case 15 | 18 | M | Chinnayanpet | Urban | Student | 25/9/18 | 1 | Playground (Lawspet) | - | - | yes | fair | poor | Used fan |

| Case 16 | 40 | F | Kosapalayam | Urban | Nurse | 01/9/18 | 1 | - | - | yes | - | fair | poor | Repellents |

| Case 17 | 68 | M | Bahour | Rural | Garlic vendor | 20/9/18 | 3 | Cuddalore and Villupuram districts | - | yes | - | fair | poor | Repellents |

| Case 18 | 20 | F | Adhingapattu | Rural | Optometrist | 30/8/18 | 2 | Works in Chennai | yes | yes | yes | fair | fair | Repellents, bed net |

| Case 19 | 20 | F | Lawspet | Urban | Student | 04/11/18 | 1 | - | - | - | yes | poor | poor | Repellents |

| Case 20 | 15 | M | Lawspet | Urban | Student | 06/11/18 | 1 | - | yes | - | yes | poor | poor | Repellents |

| Case 21 | 26 | F | Lawspet | Urban | Unemployed | 11/11/18 | 1 | - | yes | - | - | fair | poor | Used bed net |

| Case 22 | 13 | M | Lawspet | Urban | Student | 11/11/18 | 1 | - | yes | - | yes | fair | poor | Repellents |

| Case 23 | 17 | M | Lawspet | Urban | Student | 22/11/18 | 1 | - | yes | - | yes | fair | poor | Repellents |

*Cases 2 and 11 developed DHF#Cases 3, 4, 5, 7, and 8 were diagnosed of DENV-CHIKV dual infection

Dengue-Chikungunya (DENV-CHIKV) coinfection

Examination of laboratory reports revealed that five cases from two rural areas (Pillayarkuppam and Thirukanur) had DENV-CHIKV coinfection as confirmed by the presence of antibodies to CHIKV and DENV. Severe joint pain, joint deformity, skin pigmentation [Figures 2 and 3], peeling of skin and fatigue were some of the commonly reported symptoms among these cases. Most of these cases (4) continued to have limping gait, fatigue and skin pigmentation even after several days following discharge from hospital.

Figure 2.

Skin pigmentation seen in a dengue–chikungunya coinfection case in pillayarkuppam

Figure 3.

Skin pigmentation seen in a dengue–chikungunya coinfection case in pillayarkuppam

Nonspecific case presentation

A 26-year-old female from Lawspet (Case 21) reported only low-grade fever with chills for 3 days. Classical symptoms of dengue like rashes, headache, myalgia, retroorbital pain, nausea/vomiting or bleeding manifestation were not observed. She reported to a nearby government health facility on the second day of fever as three of her neighbours had developed dengue recently. She was found positive for dengue IgM after which she was admitted and treated for over a week. She was given platelet transfusion as her platelet count was below 10,000 per mL. She recovered completely.

Probable risk factors identified

Sociobehavioural risk factors

Lack of awareness

Six cases were not aware that dengue/chikungunya was transmitted by mosquito bites. They felt using fan alone will protect them from mosquito bites. Only three felt that fresh water collections should be avoided to prevent breeding of mosquitoes. Sixteen cases used mosquito repellents, two used bed nets and one used neem leaves smoke to prevent mosquito bites [Table 2].

Travel to endemic areas

Four cases had history of travel and stay at endemic areas (Chennai, Cuddalore, Villupuram districts) in the adjoining state of Tamil Nadu within 7–10 days prior to the onset of fever. The remaining cases had visited local areas within Puducherry like playgrounds, church, temples and shops, where they were likely to have been exposed to infective mosquito bites. Case 10, a 9 months primi-gravida, visited her parental home at Pillayarkuppam (a dengue endemic area) for a week where she developed fever. She was admitted and treated in a government hospital for dengue.

Occupation involving travel/shop owners or being employed in shops, presence of dengue cases either in the family and/or neighbourhood were other probable risk factors identified [Table 2].

Environmental risk factors

Poor environmental sanitation and lack of civic sense

In most of the neighbourhood of cases (78.3%) investigated, vacant plots, uninhabited houses and open grounds were used mostly as dumping ground for garbage. Indiscriminate dumping of solid wastes like broken cups, pots, bottles, containers, tyres, toilet commode, coconut shells, etc., which could be potential breeding sites for mosquitoes, was seen. Environmental sanitation within the household was found to be poor only in six (26.1%) houses [Table 2]. Clustering of cases was observed in two areas (Lawspet and Pillayarkuppam) with poor environmental sanitation. Most participants were expecting the Government should carry out activities for dengue prevention rather owning responsibility for cleanliness of their neighbourhood. They informed that antiadult/antilarval measures were not carried out immediately following occurrence of the first case in the locality (Lawspet and Pillayarkuppam), which might have led to occurrence of other cases in these areas.

Discussion

This was an exploratory descriptive study among 23 dengue recovered individuals in an endemic community that has attempted to describe the probable sociobehavioural and environmental risk factors favouring disease transmission in Puducherry. Available literature revealed ample hospital-based and community-based KAP studies on dengue either during or post outbreak; however, hardly few tried to explore the probable risk factors for the occurrence of disease among the cases.[10,16,17,18]

All 23 were primary cases with no past history of dengue fever suggesting that most of these individuals may be prone for exposure to other DENV serotypes in future. Evidence suggests that infection with any one of the four DENV serotypes confers immunity only for that particular serotype and secondary infection with heterologous types are likely to result in severe forms of dengue viral disease due to antibody-mediated immune enhancement, cross-reactive T-cell response with activation of TH-2 lineage cell and stimulation of soluble factors.[3,19] Distinguishing primary from secondary dengue early in the course of illness will help to predict the prognosis as well as to decide if a patient requires admission and close monitoring or home-based care. This becomes vital especially during outbreaks when hospitals are burdened with patients and early triage becomes obligatory, thereby saving several precious lives.[20] Hence, it is imperative to create awareness among the primary cases of dengue regarding this potential risk of secondary infection with a different serotype. Two cases had developed DHF of which one completely recovered and other succumbed. Though they claimed that they never had dengue fever in the past, it is likely that they were infected earlier and the infection must have gone unnoticed with mild symptoms. Asymptomatic or inapparent infection with dengue is much more frequent than symptomatic.[2,14] A study in Delhi (2016) conducted among close contacts and neighbourhood of index case found that 63% had asymptomatic dengue infection.[2,21] Several other studies have shown that clinically inapparent infections might represent a considerable portion of the infectious source and contribute substantially to pathogen transmission especially in areas, where vector population is high.[14,22] Fever, headache, body pain and joint pain were the commonly reported symptoms among the dengue cases, which was in concordance with several other studies.[23,24,25] We observed DENV-CHIKV coinfection in one of the areas suggesting cocirculation of both viruses. Concurrent infections may present with overlapping signs and symptoms, making diagnosis and treatment rather difficult to physicians.[26] Thus, in clinically suspected cases of dengue or chikungunya fever, it is advisable to test for both viruses as secondary infection with dengue can result in fatal disease.

Studies on flight range of female Aedes aegypti mosquito, the main vector for dengue and chikungunya, suggest that these mosquitoes spend their lifetime in or around the houses where they emerge as adults and disperse within the limited range (400 m) resulting in clustering of cases in the locality where they thrive.[27] Moreover, proliferation of mosquito vectors is favoured by improper waste management, or poor sanitation, which results in the accumulation of potential water-holding discards suitable as larval habitats. This explains the occurrence of local transmission and clustering of cases as observed in two of the areas where the environmental sanitation was more conducive for mosquito breeding. Also, it was evident from the history given by Case 10 that movement of people contributes to the spread of virus within communities and places. People from Puducherry frequently travel to endemic areas in adjoining state of Tamil Nadu (Chennai, Villupuram and Cuddalore districts) either for work or other reasons and are likely to get exposed to infective bites. Similarly, people of these three districts frequently visit Puducherry for tourism and other reasons and may carry infections back to their respective districts. Studies have shown that travel history and occupation are important in the transmission of dengue infection.[10,28]

Despite various public awareness programmes conducted by the government, our study revealed the necessity to reinforce awareness on dengue control and prevention among the community. Six (26.1%) individuals were not aware that dengue is transmitted by bite of mosquitoes, while only three (13%) knew that artificial water collections are ideal vector breeding sites. Though 18 cases used either mosquito repellents or bed nets, the risk of exposure to infective bites during the day cannot be avoided due to lack of awareness among a few in the community. Also, people who religiously practise all preventive measures tend to get demoralized when their neighbours fail to follow such measures. Community awareness and their active participation can be invigorated by regular sensitization of the general public by conducting awareness campaigns, cleanliness and sanitation drive involving school/college students, local volunteers and prominent leaders in the area. The Chapter IX of Puducherry Public Health Act, 1973 prohibits dumping of waste in streets and vacant spaces.[29] However, it was observed that people were not concerned regarding sanitation of their surroundings, which was witnessed in the form of rampant dumping of solid wastes in their streets, vacant plots or houses in their neighbourhood. Though it is a challenging issue, appropriate strategies should be evolved to ensure that the owners of these vacant plots or houses maintain their property free from dumping of wastes, mosquito breeding, while the general public should refrain from dumping solid wastes haphazardly. An effective solid waste management system in all neighbourhoods and cleaning of the public drains at regular intervals will greatly minimize choking of drains with artificial disposable containers and thereby vector breeding. Most of the cases studied reported to a health facility early during the course of illness (1–3 days, Table 2) and thereby recovered with proper management. Hence, people should be encouraged to immediately report any fever to nearby health centre for early diagnosis and treatment. Vector control measures such as source reduction and anti-larvicidal activities done on a campaign mode prior to the peak season, that is, from July to August can prevent impending outbreaks. Alternative methods of dengue control such as the Wolbachia biocontrol strategy currently tested in 12 countries worldwide and development of innovative approaches for community involvement in environmental sanitation may play a significant role in dengue control in future.[30]

Conclusion

This was an exploratory descriptive study conducted among a small sample of individuals, while studies with larger sample size are warranted to substantiate the results statistically. Local transmission was evident as most cases (19 cases) did not have any relevant travel history outside the State and from the prevailing mosquitogenic environmental conditions. Epidemiological studies with larger sample size will lead to better understanding of the dengue problem in the area. Lack of awareness about dengue, noncompliance regarding proper solid waste management and environmental sanitation among the public was clearly evident from this study. Dengue being a preventable disease can be controlled only with active participation of all stakeholders and the community. Primary care providers and family physicians being the first point of contact can play an active role in prevention and control of dengue by creating awareness to the public and notifying the higher health authorities for early initiation of antidengue measures.

Key messages

Dengue being a preventable disease can be controlled only with active participation of all stakeholders and the community. Vector control measures such as source reduction and antilarvicidal activities done on a campaign mode prior to the peak season along with regular sensitization of the community can prevent impending outbreaks. Primary care providers and family physicians being the first point of contact can play an active role in prevention and control of dengue by creating awareness to the public and notifying the higher health authorities for early initiation of antidengue measures.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the Directorate of National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP), Puducherry for providing the data. We extend our sincere thanks to all participants who volunteered to be a part of this study.

References

- 1.WHO. Dengue and severe dengue: Key facts. 2022. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue .

- 2.World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Country office for India. National guidelines for clinical management of dengue fever. 2015. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 10]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/208893 .

- 4.Kakarla SG, Bhimala KR, Kadiri MR, Kumaraswamy S, Mutheneni SR. Dengue situation in India:Suitability and transmission potential model for present and projected climate change scenarios. Sci Total Environ. 2020;739:140336. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soo KM, Khalid B, Ching SM, Chee HY. Meta-analysis of dengue severity during infection by different dengue virus serotypes in primary and secondary infections. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murhekar MV, Kamaraj P, Kumar MS, Khan SA, Allam RR, Barde P, et al. Burden of dengue infection in India, 2017:A cross-sectional population based serosurvey. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1065–73. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30250-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganeshkumar P, Murhekar MV, Poornima V, Saravanakumar V, Sukumaran K, Anandaselvasankar A, et al. Dengue infection in India:A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arunachalam N, Tana S, Espino F, Kittayapong P, Abeyewickreme W, Wai KT, et al. Eco-bio-social determinants of dengue vector breeding:A multicountry study in urban and periurban Asia. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:173–84. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.067892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutheneni SR, Morse AP, Caminade C, Upadhyayula SM. Dengue burden in India:Recent trends and importance of climatic parameters. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6:e70. doi: 10.1038/emi.2017.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swain S, Bhatt M, Biswal D, Pati S, Soares Magalhaes RJ. Risk factors for dengue outbreaks in Odisha, India:A case-control study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:625–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boratne AV, Jayanthi V, Datta SS, Singh Z, Senthilvel V, Joice YS. Predictors of knowledge of selected mosquito-borne diseases among adults of selected peri- urban areas of Puducherry. J Vector Borne Dis. 2010;47:249–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoti SL, Soundaravally R, Rajendran G, Das LK, Ravi R, Das PK. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever outbreak in Pondicherry, South India, during 2003-2004:Emergence of DENV-3. Den Bull. 2006;30:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 10]. Available from: http://nvbdcp.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=431&lid=3715 .

- 14.Ten Bosch QA, Clapham HE, Lambrechts L, Duong V, Buchy P, Althouse BM, et al. Contributions from the silent majority dominate dengue virus transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006965. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma R. Revision of Prasad's social classification and provision of an online tool for real-time updating. South Asian J Cancer. 2013;2:157. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.114142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeelani S, Sabesan S, Subramanian S. Community knowledge, awareness and preventive practices regarding dengue fever in Puducherry-South India. Public Health. 2015;129:790–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinnakali P, Gurnani N, Upadhyay RP, Parmar K, Suri TM, Yadav K. High level of awareness but poor practices regarding dengue fever control:A cross-sectional study from North India. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:278–82. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.97210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma R, Bhalla K, Dhankar M, Kumar R, Dhaka R, Agrawal G. Practices and knowledge regarding dengue infection among the rural community of Haryana. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:1752–4. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_6_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martina BE, Koraka P, Osterhaus A. Dengue virus pathogenesis, an integrated view. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:564–81. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00035-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Changal KH, Raina AH, Raina A, Raina M, Bashir R, Latief M, et al. Differentiating secondary from primary dengue using IgG to IgM ratio in early dengue:An observational hospital based clinico-serological study from North India. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:715. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vikram K, Nagpal BN, Pande V, Srivastava A, Saxena R, Anvikar A, et al. An epidemiological study of dengue in Delhi, India. Acta Trop. 2016;153:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grange L, Simon-Loriere E, Sakuntabhai A, Gresh L, Paul R, Harris E. Epidemiological risk factors associated with high global frequency of inapparent dengue virus infections. Front Immunol. 2014;5:280. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar A, Rao CR, Pandit V, Shetty S, Bammigatti C, Samarasinghe CM. Clinical manifestations and trend of dengue cases admitted in a tertiary care hospital, udupi district, karnataka. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:386–90. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.69253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debnath F, Ponnaiah M, Acharya P. Dengue fever in a municipality of West Bengal, India, 2015:An outbreak investigation. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61:239–42. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_309_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baitha U, Halkur Shankar S, Kodan P, Singla P, Ahuja J, Agarwal S, et al. Leucocytosis and early organ involvement as risk factors of mortality in adults with dengue fever. Drug Discov Ther. 2021;14:313–8. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.03089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhat RM, Rai Y, Ramesh A, Nandakishore B, Sukumar D, Martis J, et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of chikungunya fever:A study from an epidemic in coastal Karnataka. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:290–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Dengue:Dengue Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Telle O, Nikolay B, Kumar V, Benkimoun S, Pal R, Nagpal BN, et al. Social and environmental risk factors for dengue in Delhi city:A retrospective study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Puducherry (Public) Health Act. 1973. [Last accessed on 2022 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/8371/1/the_puducherry_%28public%29_health_act%2C_1973.pdf .

- 30.O'Neill SL. The use of Wolbachia by the World mosquito program to interrupt transmission of Aedes aegypti transmitted viruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1062:355–60. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8727-1_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]