Abstract

Background

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a significant complication of sleeve gastrectomy (SG). Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) is considered the primary treatment for bariatric surgery candidates with GERD. Post-operative options for GERD management are limited. This study compares the effect of transoral fundoplication (TF) prior to SG vs LRYGB in patients with GERD .

Methods

Of 30 consecutive bariatric surgery patients with GERD between 3/22/2018 and 6/23/2020, 15 patients underwent TF prior to SG (TF/SG) and 15 patients underwent LRYGB. Subjective and objective criteria, including the GERD Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL) and Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) survey, were used to assess symptoms. Surveys were collected pre-operatively, post-TF/pre-SG, 4–6 and 12–15 months post bariatric procedure.

Results

Preoperative mean scores were as follows: HRQL 32.53, RSI 21.7, 93% proton pump inhibitor (PPI) usage, 6.5% satisfaction rate. Mean BMI: 45.99 (TF/SG), 42.27 (LRYGB). At 12–15 months postoperatively: mean HRQL scores were 5.53 (TF/SG) and 6.67 (LRYGB). Both groups had a statistically significant improvement in HRQL-RSI postoperatively. PPI usage was 13% (TF/SG) and 34% (LRYGB). BMI decrease was 24% (TF/SG) and 31% (LRYGB).

Conclusions

TF/SG is at least equivalent to LRYGB in resolution or reduction of reflux symptoms at 12–15 months.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Fundoplication, Reflux, Sleeve, Bypass

Bariatric surgery is recognized as an effective weight loss tool which results in improved health and longevity for patients related to reductions in comorbid conditions. Both the Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG) and the Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) deliver significant weight loss results; however, the SG’s association with worsening or de novo gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) permeates recent literature. Conversely, the LRYGB has anecdotally become known as the solution to GERD.

Transoral fundoplication (TF) has proven to achieve long-lasting relief of GERD symptoms, and eliminate, or reduce use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) in 75–80% of cases[1]. Although TF is currently not an attractive option post bariatric surgery due to technical issues, it can be performed safely prior to SG. With these procedures working in tandem, patients attain the benefits of both, as they are synergistic in nature: TF provides an improved anti-reflux barrier and SG enables patients to lose weight, ultimately decreasing reflux symptoms.

We hypothesized that performing TF at least 6 weeks prior to SG (TF/SG) would result in decreased GERD symptoms similar to that of LRYGB. This study was designed to examine the effects of TF prior to SG compared to LRYGB on reflux symptoms in patients with GERD undergoing bariatric surgery.

Methods

Participants and Measures

This was a prospective cohort study. A total of 279 patients presented as bariatric patients beginning 3/22/2018 and completed bariatric surgery by 6/23/2020. Subjective and objective criteria were used to identify and evaluate reflux symptoms. All subjects underwent a complete preoperative history and physical examination. Patients seen for bariatric surgery consultation who reported a history of, or who presented with current symptoms of GERD, completed the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Health Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (GERD-HRQL). A score ≥ 13 on the GERD-HRQL warranted further diagnostic workup which included esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), esophageal ambulatory pH study, and esophageal manometry. Bariatric patients with GERD-HRQL scores ≥ 13 at initial consultation and who were confirmed to have GERD by preoperative testing were considered potential subjects for the study. Each patient was presented at a multi-disciplinary GERD conference in which the patient’s diagnostic results were reviewed with consideration of their personal history and comorbidities. Treatment plans were then formulated and discussed with patients.

The presence of GERD was defined as esophagitis demonstrated on EGD, elevated DeMeester scores (≥ 14.7) on pH testing, history of PPI use or a GERD-HRQL score ≥ 13. Of 279 patients, 183 demonstrated no significant evidence of GERD; therefore, no additional testing was required. Eleven patients had undergone previous SG and underwent conversion to LRYGB for reflux. Of the 85 remaining patients, 37 had a negative work up and proceeded with SG. Thirty patients chose to proceed with LRYGB. Eighteen patients chose to undergo TF/SG. Study enrollment continued until 15 consecutive TF/SG patients and 15 LRYGB patients with a complete data set were obtained.

Esophageal manometry was a consideration in determining surgical options. In the absence of significant dysmotility, as determined by the Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, TF/SG was the preferred recommendation. Significant dysmotility generally resulted in a recommendation to proceed with LRYGB. In the presence of esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction or ineffective esophageal motility, a minimum of 70% intact swallows was required prior to proceeding with TF.

Treatment options were then presented to the patient. In general, patients were allowed to choose the surgical option that met their treatment goals if they were able to demonstrate a clear understanding of the risks, benefits, and indications for each choice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart in choosing surgical options

Post-operative assessments of reflux symptoms, medication use, and body mass index (BMI) measurements were conducted at office visits in the following increments: at least 4 weeks post TF and prior to SG, 4 to 6 months post TF/SG or LRYGB and 12 to 15 months post TF/SG or LRYGB.

Exclusion criteria included patients undergoing conversion from SG to LRYGB, with incomplete records missing any component of the demographic data to be analyzed, or who were considered lost to follow-up. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Surgical Technique

All patients underwent preoperative endoscopy by the surgeon. Size of hiatal hernia (HH) and grade of esophagitis if present were documented. If the patient was considering SG, a Bravo probe was placed at the time of endoscopy and those patients underwent a high-resolution manometry.

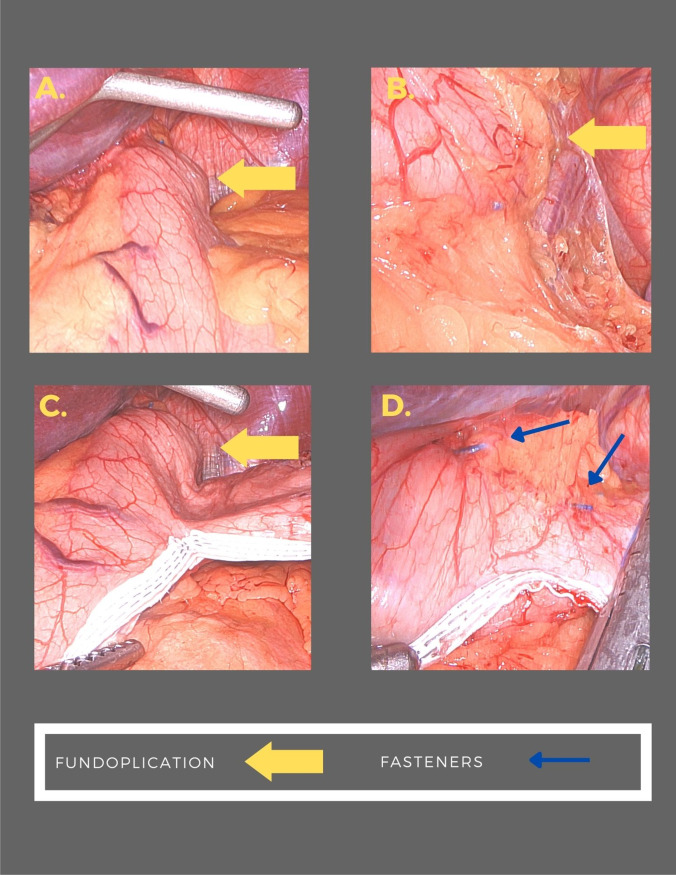

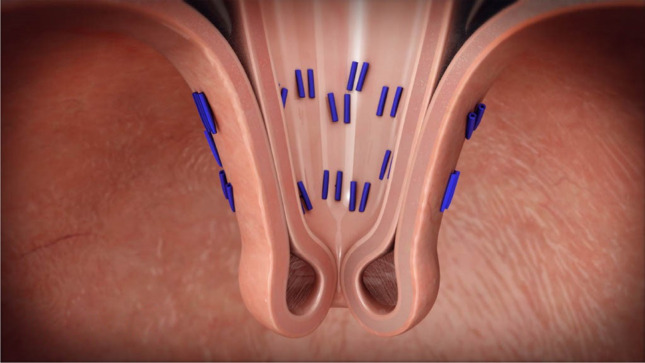

The technique for laparoscopic HH repair and concomitant endoscopic fundoplication has been described elsewhere. Patients with a HH underwent laparoscopy using four 5-mm trocars and a Nathanson liver retractor. The gastrohepatic omentum was divided. The peritoneum overlying the base of the right crus of the diaphragm was incised and the incision was carried along the right crus across the anterior hiatus and onto the left crus. The hernia sac was excised from the mediastinum. Circumferential dissection of the esophagus was performed with care not to injure the anterior or posterior vagus nerves. Dissection proceeded until approximately 3 to 4 cm of the esophagus was resting within the abdominal cavity without retraction. The crural defect was closed using posterior 0 Ethibond pledgeted U stitches. Stitches were placed until there was no significant space surrounding the esophagus. Once this was accomplished, the liver retractor and trocars were removed. The patient then underwent a repeat endoscopy to confirm appropriate repair of the HH and determine the morphology of the GE junction. The EsophyX device was then introduced, and the valve was reconstructed using the TIF 2.0 technique. Full thickness esophagogastric plications were performed in 270° using an average of 20 fasteners (Fig. 2). Following reconstruction, the EsophyX device was removed, and a completion endoscopy was performed.

Fig. 2.

Esophagogastric plications

Laparoscopic SG was performed no sooner than 6 weeks following HH repair with endoscopic fundoplication. Four trocars were placed at the same sites as previous as well as a Nathanson liver retractor. A 34 French bougie was positioned adjacent to the lesser curve of the stomach. Mobilization of the greater curvature of the stomach was performed beginning 6 cm from the pylorus. The short gastric vessels were divided toward the angle of His. Care was taken to avoid disruption of the fundoplication. The stomach was then divided using serial fires of the Ethicon Echelon 60-mm powered stapler. A single green load was used followed by gold loads and finally a blue load to complete the resection. Peri-Strips dry with Veritas staple line reinforcements were used. The resection line was diverted lateral to the fundoplication without leaving excess fundus. (Fig. 3) A well-vascularized portion of the omentum was selected, and omental pedicle flap was created. The flap was used to cover the most proximal portion of the gastric staple line.

Fig. 3.

Fundoplication at LSG

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was performed using five trocars and a Nathanson liver retractor. A separate incision was made in the left flank for a 21-mm Covidien EEA circular stapler. An orogastric tube with a 30-cc balloon was placed into the stomach under direct visualization. Hiatal hernia, if present, was repaired using the technique described above. The balloon was inflated and pulled back to the GE junction. A perigastric window was created in the mesentery of the lesser curve just distal to the left gastric pedicle. A gastric pouch was created using serial firings of the Ethicon Echelon 60-mm powered stapler with blue loads and Peri-Strips dry with Veritas staple line reinforcements around the 30-cc balloon. An anterior gastrotomy was made in the pouch and the anvil from the 21-mm stapler was inserted. The anvil was secured using a 2–0 Vicryl pursestring stitch. Next, the omentum was divided sagittally and the transverse mesocolon was elevated. Ligament of Treitz was identified and a 40 cm Roux limb was measured and marked with a stitch. The jejunum was divided at this point. A Roux limb was created of it with a minimum of 100 cm. A side-to-side jejunojejunostomy was created using a 60-mm white loaded stapler. The enterotomy was closed using a running 2–0 silk stitch. The mesentery of the end of the Roux limb was divided to relieve any tension if present. The end of the Roux limb was opened, and the circular stapler was inserted. A gastrojejunostomy was completed with the Roux limb in an antecolic antegastric position. The devitalized portion of the Roux limb was removed. Seromuscular stitches were placed on either side of the anastomosis between the Roux limb and the pouch to relieve any tension. A well-vascularized portion of the omentum was selected, and an omental pedicle flap was created and placed across the anterior aspect of the anastomosis. It was secured in place using the tails of the previously placed sutures. A non-crushing bowel clamp was used to occlude the Roux limb. Methylene blue was instilled through the orogastric tube into the pouch to check for leaks. The methylene blue was aspirated and the orogastric tube was withdrawn. Upper endoscopy was then performed to assess for bleeding at the staple lines.

Statistical Analyses

Initially, the Wilcoxon Mann Whitney (WMW) test was used to assess significant differences between groups. Instances in which no statistical difference was found between groups in the relevant measures were then evaluated for their equivalency using a non-parametric test).

Results

Participant Characteristics

One hundred percent of participants completed all assessment measures at each time point. Preoperatively, the groups did not differ significantly from each other regarding age (W = 125, p = 0.618), initial BMI (W = 124.9, p = 0.633), HRQL (W = 124.9, p = 0.633), or RSI (W = 122.5, p = 0.693). The median age of the total cohort was 49 years, median BMI was 44.13, and 90% were female (Table 1). Eighty-seven percent of LRYGB patients had a HH repair at the time of bariatric surgery. All TF/SG patients underwent HH repair at the time of TF; there were 2 HH recurrences at the time of SG.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| TF/SG | LRYGB | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean | 48 | 50 |

| Median | 46 | 51 |

| Range | 29–68 | 39–61 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 87% | 93% |

| Male | 33% | 7% |

| Pre-Op BMI | ||

| Mean + / − SD | 46 ± 7.8 | 42.3 ± 5.3 |

| Median | 42.1 | 42.1 |

| Range | 37.4–58 | 35.3–54.8 |

| Post-Op SG or LRYGB BMI | ||

| Mean + / − SD | 37.5 ± 8 | 32 ± 4.6 |

| Median | 32.8 | 29.8 |

| Range | 27–55 | 27–40.8 |

| Pre-Op | ||

| GERD HRQL mean | 32.1 ± 11.9 | 34 ± 13.6 |

| GERD HRQL median | 32 | 37 |

| GERD RSI mean | 21 ± 14 | 23 ± 12 |

| GERD RSI median | 19 | 27 |

| Post-Op SG or LRYGB 12–15 months | ||

| GERD HRQL mean | 5.5 ± 7.9 | 6.6 ± 10.6 |

| GERD HRQL median | 2 | 2 |

| GERD RSI mean | 4 ± 5.6 | 3.1 ± 5 |

| GERD RSI median | 3 | 0 |

| Pre-Op | ||

| PPI use | 93% | 93% |

| Post-Op SG or LRYGB 12–15 months | ||

| PPI use | 13% | 33% |

Legend: TF/SG, transoral fundoplication prior to sleeve gastrectomy; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; GERD HRQL, GERD Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire; GERD RSI, GERD Reflux Symptom Index; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BMI, body mass index

GERD-HRQL Scores

The primary treatment response metric was GERD-HRQL score. Individual item scores ≤ 2 were considered indicative of eliminated symptoms; a ≥ 50% reduction in overall scores was considered significant clinical improvement. A secondary metric was discontinuation of daily PPI use. HRQL scores decreased over the course of either treatment in almost all cases. The mean drops in HRQL score were 26.6 points (median = 28) for the TF/SG group and 26.27 (median = 32) for the LRYGB group.

RSI decreased over the course of either treatment in almost all cases with three participants in the TF/SG group reporting an increase in RSI score 1 year after treatment. The mean drops in RSI score were 16.53 points (median = 16) for the TF/SG group and 19.73 points (median = 23) for the LRYGB group.

The final assessment measure was gathered between 12 and 15 months post bariatric surgery. No statistically significant differences in these measures were detected between treatment groups. Twelve patients (80%) in the TF/SG group experienced resolution of symptoms and two patients (14%) had at least clinically significant improvement of symptoms. Ultimately, 13 out of 15 patients in the TF/SG cohort had discontinued reflux medication by 15 months postoperatively, compared to 10 out of 15 patients in the LRYGB cohort. The LRYGB group demonstrated the following: ten patients (67%) had resolution of symptoms, zero patients (0%) had at least clinically significant improvement of symptoms, and five patients (34%) had no improvement of symptoms.

The ensuing test of equivalence could not reject the null hypothesis that there was a statistical difference of greater than 20% between the two groups in terms of their change in RSI and HRQL score. The Fisher Exact Test was utilized on GERD HRQL-RSI measurements, treating the outcomes as either successes (full resolution) or failure (HRQL did not reduce by ≥ 50%). In all cases, the p-values were greater than 0.05, once again demonstrating that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that there is no difference in the outcomes between the two groups.

Pre- to Post Surgery Weight Change

Mean initial BMI of the cohort was 44. Preoperative mean BMI was higher in the TF/SG arm by 9%. Percent of total BMI decrease for the cohort was 27% (TF/SG 24%, LRYGB 31%). Percent total body weight loss for the cohort was 26.1% (TF/SG 21.8%, LRYGB 30.9%).

Time Interval

Time interval between TF and SG ranged between 7 and 24 weeks, with a median of 14 weeks. This time, the interval was influenced by patient preference, and the pausing of elective surgery due to COVID-19 in early 2020. We recommend at least 6 weeks between completion of TF and undergoing SG.

Adverse Events

There was one early major complication in the TF/SG arm: postoperative bleeding after SG which required blood transfusion. In the LRYGB arm, there was one early major complication in which hemoclips were placed endoscopically due to bleeding at the gastro-jejunal anastomotic site. Additionally, there was one early minor complication involving dehydration due to nausea and vomiting with subsequent intravenous fluid administration.

Discussion

A review of the literature demonstrates a large majority of studies compare the rate of GERD in SG to the rate of GERD in LRYGB. Although relevant, these studies have created a skewed scale by which to measure successful treatment of GERD. The prevalence of GERD symptoms has been found to increase significantly from 12.1 to 47% after SG [2]. Other studies have found that among patients with no preoperative GERD, 30–51% developed symptoms postoperatively [3]. SG is associated with a substantially increased possibility that acid reduction medication will be needed for GERD symptoms within 12 months postoperatively when compared to LRYGB [4]. Long-term studies have demonstrated an increase in esophagitis in 87% of patients following SG, with a 13% increase in risk of esophagitis every year postoperatively and a prevalence of BE as 11.5% [5].

Short-term follow-up after LRYGB reveals endoscopic and histologic regression to normal mucosa in only 42.9% of patients who had presented with preoperative esophagitis [6]. Additionally, 92.8% of patients continued PPI therapy in the first postoperative year. DuPree et al. (2014) found that preoperative bariatric patients with GERD symptoms who underwent LRYGB resulted in 62.8% of patients with complete resolution of symptoms, while 17.6% had persistent symptoms and 2.2% had worsening symptoms (3).

The conundrum for bariatric surgeons is offering patients with known reflux an option which is safe, effective for weight loss, and treats GERD as treatment options are limited for patients who develop GERD after bariatric surgery.

To our knowledge, there are no other studies investigating the effect of TF prior to SG compared to LRYGB on reflux symptoms. Postoperatively, both groups demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in HRQL-RSI scores (p value < 0.001). Despite higher BMI in the TF/SG arm post bariatric surgery, GERD scores were comparable to those in the LRYGB arm. These preliminary findings suggest that TF/SG provides protective measures against the progression of GERD and its sequelae, while still providing significant weight loss without the higher morbidity risks of LRYGB.

The manipulation of several natural anti-reflux mechanisms contributes to the development of de novo or worsening GERD with the creation of the gastric sleeve: disruption of the Angle of His, resection of the sling fibers, decreased gastric compliance, and increased gastric pressure [7]. Together, these factors create increased intragastric pressure against a weakened lower esophageal sphincter (LES), culminating in reflux of gastric contents.

Conversely, TF accentuates the Angle of His, strengthens the LES, and increases distal esophageal contractile function. Rerych et al. (2017) demonstrated increased distal contractile integral from improved peristaltic function following fundoplication [8]. Collectively, these factors provide intrinsic fortification against the development of reflux which is otherwise induced by SG.

Within the TF/SG cohort, one patient experienced increasing reflux symptoms throughout the first postoperative year, representing the only outlier in the study. Despite repair during the TF and again at the SG, the patient had a recurrent HH, but an intact fundoplication on EGD 1 year postoperatively. Given the intact fundoplication in the setting of a recurrent hernia, the return of reflux symptoms is attributed to the loss of the Angle of His. Analysis of the data without this outlier presents an overall HRQL reduction that is statistically significant in favor of the TF/SG procedure for elimination and reduction of reflux symptoms when compared to LRYGB.

Limitations

Results were analyzed up to 15 months post bariatric surgery, representing short-term follow up. Longitudinal observation is necessary to evaluate the durability of these findings and is currently underway with a larger cohort. This study compared two cohorts of similarly matched patients but a randomized controlled trial would be a preferred means of comparison.

GERD symptoms were assessed using the subjective GERD-HRQL. This may lead to an overestimation or underestimation of symptoms. With the prevalence of silent GERD data mounting, studies that incorporate objective measures of GERD are needed.

Currently, the authors of this study are conducting further research which may confirm the data analysis in this study with objective measures such as EGD, with long term follow-up, and incorporation of a larger sample size.

Conclusions

No statistical difference between groups in HRQL-RSI score improvement over the course of their treatment was demonstrated. Five (34%) LRYGB patients continued with PPI usage at 1 year postoperatively; in contrast, only two (13%) remained on a PPI following TF/SG. While both cohorts demonstrated an overall decrease in PPI usage, this value suggests the TF/SG provides greater alleviation of symptoms and increased patient satisfaction. Our preliminary findings show that TF/SG is at least comparable to LRYGB in early resolution or reduction of reflux symptoms, independent of BMI reduction. With its safety profile and comparable results related to weight loss and reflux improvement, the TF/SG is a viable option to treat both obesity and GERD, without the complication risk carried by the LRYGB.

Acknowledgements

Steven Barth

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Research Board and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Key Points

• TF does not alter SG technique or complications.

• TF/SG is protective against reflux.

• TF/SG provides an alternative to LRYGB for reflux management and weight loss.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lori Norris and Glen Strickland have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Testoni P, Testoni S, Mazzoleni G, Vailati C, Passaretti S. Long-term efficacy of transoral incisionless fundoplication with Esophyx TIF 20 and factors affecting outcomes in GERD patients followed for up to 6 years: a prospective single-center study. Surgical Endoscopy. 2015;29(9):2770–2780. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-4008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai C, Huang C, Lee Y, Chang C, Lee C, Lin J. Increase in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms and erosive esophagitis 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy among obese adults. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1260–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupree C, Blair K, Steele S, Martin M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with preexisting gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):328–334. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr A, Frelich M, Bosler M, Goldblatt M, Gould J. GERD and acid reduction medication use following gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:410–415. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4989-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qumseya BJ, Qumsiyeh Y, Ponniah SA, et al. Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(2):343. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrew B, Alley JB, Aguilar CE, Fanelli RD. Barrett’s esophagus before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for severe obesity. Surg Endosc. 2018;32(2):930–936. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5768-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moussaoui I, Vyve E, Johanet H, et al. Five-year outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective multicenter study. Am Surg. 2022;88(6):1224–1229. doi: 10.1177/003134821991984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rerych K, Kurek J, Klimacka-Nawrot E, et al. High-resolution manometry in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease before and after fundoplication. J Neurogastroenterol Motility. 2017;23(1):55–63. doi: 10.5056/jnm16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]