Abstract

Objective

Two thirds of adults experience at least one lifetime traumatic incident. Specifically, childhood traumas (physical neglect, emotional neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse) are associated with increased alcohol use. According to the self-medication hypothesis, alcohol is used to alleviate upsetting thoughts and memories. This may lead to greater impaired control over alcohol use (i.e., a breakdown of an intention to limit drinking). Utilizing mindfulness reduces maladaptive responses to trauma. Trauma and difficulties maintaining control (generally) have been examined with mindfulness as a mediator; however, control over alcohol use specifically, has not.

Methods

We analyzed data from a cross-sectional, student survey (N = 847, 49% female) utilizing path modeling. We examined mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use as potential mediators between trauma and alcohol outcomes (i.e., drinks per drinking day [DPDD] and alcohol-related problems).

Results

Emotional neglect (EN) was the strongest predictor among five facets of trauma. Higher EN related to lower mindfulness (β = − 0.22; SE = 0.05; p ≤ 0.001) and greater impaired control over alcohol (β = 0.11; SE = 0.06; p = 0.05). Finally, EN was related to higher DPDD, mediated by mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use (standardized indirect effect = 0.006; 95% CI, 0.002, 0.012).

Conclusion

These findings suggest potential mediating pathways from childhood trauma to alcohol-related outcomes via mindfulness and greater impaired control over alcohol use. Current research informs efforts to promote mindfulness interventions to reduce alcohol use and related problems among college students, especially those who have experienced childhood traumas and may experience elevated impaired control over alcohol use.

Keywords: Drinking consequences, Impaired control over drinking, Risk factors, Alcohol use, Heavy drinking, Childhood trauma

Approximately two out of three adults have experienced at least one traumatic life event, many in their childhood (Karam et al. 2014; Norris and Sloan 2014; Stein et al. 2014). Specifically, a childhood trauma refers to multiple distressing childhood experiences, such as interpersonal violence, abuse, and neglect (D’Andrea et al. 2012). Prior research has found that although college students have similar rates as the general population for lifetime experience of emotional, physical, and sexual childhood abuse (Duncan 2000; Kenny and McEachern 2000), previously traumatized students are at a higher risk of experiencing another traumatic event while on campus (Fisher et al. 2000). Traumatic childhood events are associated with negative consequences in adulthood, including poorer relationship quality, intimacy dysfunction, and social adjustment difficulties (Davis et al. 2001; Ducharme et al. 1997; Schore 2009). Further, students with childhood traumas experience greater mental health difficulties later in their adult lives (Carr et al. 2013) and may have difficulties progressing in their studies (Duncan 2000). Relatedly, maintaining control over thoughts and behaviors can be difficult for those who experience childhood traumas, resulting in impulsivity, depression, and/or anger (Schwandt et al. 2013).

According to the self-medication hypothesis, alcohol can be used as a negative reinforcer to reduce uncomfortable feelings such as effects of childhood traumas (Conger 1956; Hersh and Hussong 2009). Alcohol is often used to withdraw psychologically from an environment following trauma (Allem et al. 2015; Dalenberg et al. 2012) making alcohol and other substance use disorders (AUD/SUD) more likely to occur (Brady and Back 2012; Carvajal and Lerma-Cabrera 2015). Heavy drinking is already a concern among college students, because 40% aged 18–22 report at least one heavy drinking day (4+ for women; 5+ for men) in the past month (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) 2015a; US Department of Health and Human Services 2016). This rate may be exacerbated by previous traumas (Arnekrans et al. 2018). Moreover, the severity of alcohol-related problems is directly related to the severity of childhood traumas in treatment-seeking adults (Schwandt et al. 2013). Therefore, college-aged young adults with histories of childhood trauma may be more inclined to misuse alcohol (Arnekrans et al. 2018; Carr et al. 2013; Schore 2009). While links between alcohol use and trauma have been explored frequently in the adult population and among college students specifically, relationships between trauma and the construct of impaired control over alcohol use have barely been addressed.

Impaired control over alcohol use is “a breakdown of an intention to limit consumption in a particular situation” (Heather et al. 1993, p. 701). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013) marks impaired control as one of four central indicators for an AUD and is particularly relevant to young drinkers because it is one of the earliest-developing signs of AUD (Leeman et al. 2012; Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez 2006). Greater impaired control over alcohol use is directly linked to self-reported alcohol problems up to 3 years later in undergraduates (Leeman et al. 2009). Examining impaired control over alcohol use among people who have experienced childhood traumas may be important because a common response to trauma is to dissociate and withdraw or otherwise suppress awareness (i.e. numb, distract, deny; Follette 2014). Dissociation occurs when connections among affect, cognition, and perception of voluntary control over behavior are modified or disrupted (Sanders 1986; Van IJzendoorn and Schuengel 1996). Impaired control over alcohol use may fit into this suppressed awareness by definition (i.e., suboptimal ability to limit drinking; Heather et al. 1993). These maladaptive coping mechanisms occur to shut out negative affective responses to events or people associated with trauma (Schore 2014) but may also suppress awareness of beneficial practices, such as noting how much alcohol one is consuming. This is why monitoring impaired control over alcohol use may be important among young adults.

Mindfulness can decrease the need to dissociate in this way. Mindfulness is defined as awareness that arises through paying attention to the present moment in a purposeful and non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn 2003). Mindfulness can assist those who have survived a traumatic event by decreasing hyperarousal symptoms, reconnecting with their bodies (i.e., lower dissociative symptoms), and differentiating past traumatic memories from the present moment (Boughner et al. 2016; Goodman and Calderon 2012). Mindfulness can also increase acceptance of traumatic experiences and reduce related negative affect (Baslet and Hill 2011; Neziroglu and Donnelly 2013; Schoorl et al. 2015). Individuals who report greater mindfulness show greater improvement of attentional functions, cognitive flexibility (Moore and Malinowski 2009), and enhanced adaptive emotional regulation to cope with stress (Britton et al. 2012; Moore and Malinowski 2009). Previous research also shows that among college students, higher trait mindfulness relates to decreased drinking motives (Roos et al. 2015), alcohol consumption (Bramm et al. 2013), and drinking consequences (Fernandez et al. 2010; Murphy and MacKillop 2012; Pearson et al. 2015). Based on these findings, mindfulness has the potential to reduce several negative consequences associated with trauma. Specifically, mindfulness may reduce high-risk drinking by lowering impaired control over alcohol use.

Previous research has found that heightened awareness through mindfulness may increase the ability to adhere to limits on drinking (Mermelstein and Garske 2015). Therefore, the current study examined potential mediational pathways through mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use in relation to college students’ childhood trauma (physical neglect, emotional neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse) and alcohol-related outcomes (i.e., higher drinks per drinking day and alcohol-related problems). We hypothesized a sequential mediational pathway. Specifically, we predicted that greater childhood trauma (all five facets) would be associated with lower trait mindfulness scores, greater impaired control over alcohol use, and consequently, higher drinks per drinking day and alcohol-related problems.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 18 and older (mean age = 19.88; SD = 2.79; range = 18–54). All consented to participate and were told they could withdraw consent at any time (Morean et al. 2018). There was an even gender split (49% female). Half (54%) were Caucasian, followed by Asian (22%), Hispanic (15%), African-American (5%), and Native American (1%); 3% identified as “other race.” Our analysis sample consisted of 847 respondents. We removed 94 subjects who either did not complete more than 50% of the questionnaire or had missing data on the exogenous variables (i.e., covariates and the trauma scale items). Most respondents were light-to-moderate drinkers with the majority reporting drinking a few times per month, and three to four drinks per drinking day. About 20% of the sample reported heavy drinking within the past year (five or more standard drinks on a single occasion), and 16% reported never drinking in their lifetime. A majority (57%) reported other substance use in the past year, and from this subset, 56% used marijuana, 14% used cocaine, and 8% reported non-prescription pain medication or heroin. Over half of the sample reported six or more alcohol-related problems (YAAPST score out of 27). The overall total childhood trauma score was a mean of 40, considered a “low to moderate” total trauma score (range = 25–125; SD= 15). Emotional neglect was the highest endorsed facet of trauma, followed by emotional abuse (see Table 1).

Table. 1.

Demographics, bivariate correlations, means and standard deviations on study variables N=841

| 1. Mindfulness |

2. Impaired Control |

3. Drinks per Drinking Day |

4. Lifetime YAAPST† |

5. Physical neglect |

6. Emotional Neglect |

7. Physical Abuse |

8. Emotional Abuse |

9. Sexual Abuse |

10. Gender |

11. Age |

12. Ethnicity |

13. Other Drug Use |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 2. | −.13** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 3. | .06 | .22** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 4. | −.02 | .42** | .37** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 5. | −.13** | .29** | −.05 | .14** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 6. | −.21** | .27** | −.06 | .11** | .67** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 7. | −.01 | .16** | −.02 | .13** | .51** | .41** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 8. | −.12** | .13** | −.04 | .13** | .44** | .55** | .58** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 9. | −.07 | .15** | −.10** | .07* | .49** | .33** | .51** | .46** | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 10. | −.01 | .09** | .28** | .15** | .11** | .12** | .13** | −.04 | .03 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 11. | .11** | .06 | −.08* | .06 | .13** | .12** | .15** | .09** | .05 | .04 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12. | −.12** | .14** | −.20** | −.09** | .25** | .23** | .18** | .10** | .18** | .02 | .01 | -- | -- |

| 13. | .01 | .07* | .32** | .42** | −.05 | −.01 | .02 | .02 | −.06 | .17** | −.09** | −.22** | -- |

| Mean (SD) | 122.22 (14.49) | 18.71 (7.12) | 2.92 (1.21) | 7.40 (3.33) | 6.03 (5.03) | 10.09 (4.65) | 7.44 (3.57) | 8.66 (4.02) | 6.75 (3.83) | -- | 19.88 (2.79) | -- | -- |

| Range | 39-195 | 10-50 | 1-5 | 0-27 | 5-25 | 5-25 | 5-25 | 5-25 | 5-25 | 18-54 |

p-value significant at 0.01 level

p-value significant at 0.05 level

YAAPST= Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test

Procedures

The current study was derived from a larger, IRB-approved cross-sectional study (Morean et al. 2018) that sought to examine risk and protective factors associated with college students’ alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. This new study was designed to examine relationships among childhood trauma, mindfulness, and impaired control over alcohol use. The survey was administered anonymously, and only random subject codes were utilized. All participants were debriefed when they returned their completed, paper surveys to a sealed box with a slit in the top.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to report on their age, gender, and ethnicity along with other demographic questions (see main outcome paper: Morean et al. 2018). For this study, age was kept as a continuous variable. Gender was a dichotomous variable (0 = female, 1 = male), as was ethnicity (white = 0, non-white = 1).

Other Drug Use

Participants were asked about illicit use of the following within the past year: marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and prescription medication. The original questionnaire had answers ranging from “never used” to “use daily” for each substance. For this analysis, items were combined into one dichotomous variable of those who had used substances within the past year and those who had not (i.e., never used = 0, used = 1).

Alcohol Descriptives

Participants also answered how often they consumed alcohol in the past year (ranging from “less than once a month” to “daily or nearly daily”), and how many times in the past year they drank five or more beverages on a single occasion (ranging “never” to “daily or nearly daily’). These are reported above in the ‘Participants’ section.

Impaired Control Over Alcohol Use

Heather et al. (1993) developed the Impaired Control Scale (ICS) to measure impaired control over alcohol use as a continuous variable reflecting the frequency of difficulties limiting drinking. As in many previous studies (e.g., Naidu et al. 2019; Vaughan et al. 2019; Wardell et al. 2016), the sum score of part 3 (predicted control) was used. This subscale assesses how successful the drinker believes future attempts to limit their drinking will be. The ten-item subscale includes items like “Even if I intended having only one or two drinks, I would end up having many more.” Responses ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Internal consistency was good with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

Drinks per Drinking Day (DPDD; Outcome)

Participants were asked “What is (or was) your usual quantity of alcoholic beverages consumed at any one drinking occasion?” Response options ranged from 1 (1 bottle or can of beer, 1 glass of wine, or 1 drink of distilled spirits), 2 (2 bottles, glasses, or drinks), 3 (3 or 4 bottles, glasses, or drinks), 4 (5 or 6 bottles, glasses, or drinks), 5 (7 or more bottles, glasses, or drinks). This item was used for the main outcome of drinks per drinking day. In order to address the full spectrum of alcohol involvement, non-drinkers were retained in the sample for analysis. In particular, we wanted the opportunity to observe that mindfulness and trauma may relate to a lack of alcohol consumption. Our ability to do so would be limited if non-drinkers were excluded.

Young Adult Alcohol-Reported Problems (Outcome)

The Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut and Sher 1992) is a 27-item questionnaire that assesses alcohol-related problems among college students. The YAAPST assesses both traditional consequences (hangovers, blackouts, driving while intoxicated) and additional consequences that are presumed to occur at higher rates in a college student population (e.g., missing class, damaging property/setting off alarms, getting involved in regrettable sexual situations). The YAAPST uses multi-point response scales (0 = “No, never” 1 = “Yes, but not in the past year” 2 = “‘Yes, in the past year”), but for this analysis, we collapsed the responses into two categories (0 = never, 1 = yes) to indicate presence vs. absence, consistent with some prior studies (e.g., Kahler et al. 2004; Rothman et al. 2008) and summed all items to yield a “lifetime YAAPST score.” A close review of the YAAPST items indicates that none of the items in the measure pertain directly to impaired control over alcohol use, thus there was no need to remove any items from the YAAPST for the purposes of the current study. The YAAPST had a high internal consistency in this study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

Childhood Trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al. 2003) is a 28-item retrospective, self-report questionnaire designed to assess five types of childhood trauma: emotional abuse (EA; e.g., “I felt that someone in my family hated me”), emotional neglect (EN; e.g., “There was someone in my family who helped me feel that I was important or special”—reverse-scored), physical abuse (PA; e.g., “People in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks”), physical neglect (PN; e.g., “My parents were too drunk or high to take care of the family”), and sexual abuse (SA; e.g., “Someone molested me”). Respondents rated on a 5-point scale how true the statement was based on their childhood experiences, ranging from 1 “Never true” to 5 “Very Often True.” We calculated sum scores for each subscale, which were treated as exogenous variables in our model. In the present study, we found good internal consistency for EA, EN, PA, PN, and SA with Cronbach’s alphas of 0.81, 0.83, 0.82, 0.74, and 0.92, respectively.

Mindfulness

The Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS; Baer et al. 2004) consists of 39 Likert-scale items, 18 of which are reverse scored. This questionnaire asks participants to rate items with respect to one’s general experience, rather than a specific time point or period. Possible response options are “Never or very rarely true,” “Rarely true,” “Sometimes true,” “Often true,” and “Very often or always true.” High scores (1–5 for individual items) indicate high levels of mindfulness. In the current study, we used a total mindfulness score summing the item scores across four subscales: observing (12 items), describing (8 items), acting with awareness (10 items), and accepting without judgment (9 items). The global KIMS had positive correlations with openness, emotional intelligence, and self-compassion, and negative correlations with psychological symptoms, neuroticism, alexithymia, dissociation, and absent-mindedness (Baer et al. 2006). The measure showed high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82, similar to the original findings (Baer et al. 2004).

Data Analysis

All variables and sample characteristics were examined using SPSS version 23, and the hypothesized path model was estimated using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2017). Standard descriptives and normality were examined on all variables. We used maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation with bootstrapping and missing data adjustment (Efron and Tibshirani 1993; Manly 1997; Muthén and Muthén 2007) in Mplus to avoid potential biases resulting from non-normality for parameter estimates in the model and the estimates of potential mediated effects obtained by the product of path coefficients (see Fritz and MacKinnon 2007, p. 5). Overall, model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices (e.g., RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR). Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations of the main study variables and demographics were reported in Table 1.

Childhood trauma was specified with five subscales (i.e., physical/emotional neglect, physical/emotional abuse, and sexual abuse). Based on mediation analysis involving sequential multiple mediators (Taylor et al. 2008), trauma facets (X1–5) were modeled to predict drinks per drinking day (Y1) and alcohol-related problems (Y2) through mindfulness (M1) and impaired control over alcohol use (M2). In addition, direct relations between trauma facets and the alcohol outcome variables were estimated. Demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity) and other drug use were included as covariates in estimating relationships among the main study variables. All exogenous variables (i.e., trauma subscales and covariates) were allowed to correlate with each other. Potential mediated effects were tested using the bootstrap method with 20,000 resamples, along with MODEL IND implemented in Mplus. Potential mediated effects of interest are shown and include all possible pathways. Standardized 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the estimates were examined, with CIs that do not include zero indicating significant indirect effects (MacKinnon et al. 2004; Taylor et al. 2008; Tofighi and MacKinnon 2011).

Results

Model Fit and Direct Relationships

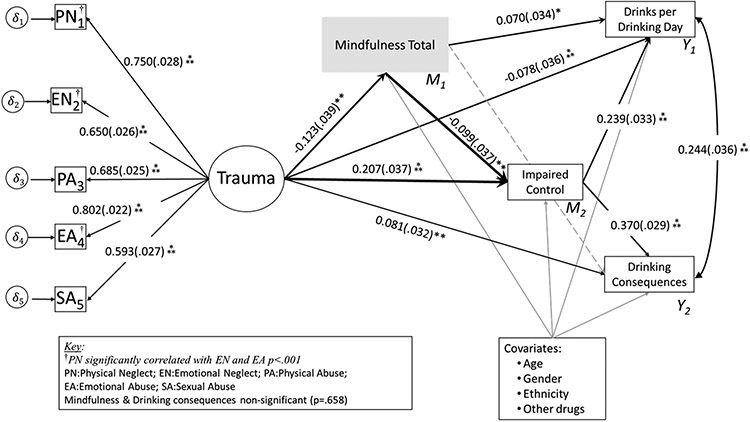

The hypothesized model (Fig. 1) fit the data well (X2[3] = 1.46; p = 0.69; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.031; RMSEA = 0.00; 90% CI, 0.000, 0.044; probability of RMSEA ≤ 0.05 = 0.972; SRMR = 0.005). Variance of the endogenous variables explained by their predictors can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Model for childhood trauma on drinks per drinking day and alcohol-related problems. Note: Standardized point estimates were reported. Only significant direct paths are reported; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. All covariates were significantly related to drinks per drinking day (male, younger, white, other drug use = higher DPDD; p ≤ 0.034) and alcohol problems (male, older, white, and other drug use = more problems; p ≤ .017). Other drug use was significantly related to greater impaired control over alcohol use (p = 0.004), and older age was significantly related to higher mindfulness (p = 0.001)

As expected, higher childhood trauma was significantly associated with lower mindfulness scores, specifically for emotional neglect (EN: β = − 0.22; SE = 0.05; p < 0.001). Surprisingly, higher physical abuse was significantly associated with higher levels of mindfulness (PA: β = 0.12; SE = 0.05; p = 0.021). Higher reports of emotional neglect (EN: β = 0.11; SE = 0.06; p = 0.054) as well as greater physical neglect (PN: β = 0.22; SE = 0.06; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with greater impaired control over alcohol use. Among the mediators, higher mindfulness was significantly related to lesser degrees of impaired control over alcohol use (β = − 0.11; SE = 0.04; p = 0.003). Regarding direct paths from trauma facets to outcome variables (Y1 and Y2): higher emotional abuse was significantly related to more alcohol-related problems (EA: β = 0.09; SE = 0.04; p = 0.047), whereas higher reports of sexual abuse and emotional neglect were directly related to fewer drinks per drinking day (SA: β = − 0.10; SE = 0.04; p = 0.009; EN: β = − 0.12; SE = 0.05; p = 0.015). Mindfulness was not directly related to drinks per drinking day or alcohol related problems. Conversely, greater impaired control over alcohol use was positively associated with drinks per drinking day (β = 0.24; SE = 0.03; p < 0.001) and alcohol-related problems (β = 0.40; SE = 0.03; p < 0.001).

Tests of Potential Mediated Effects

As hypothesized, we found that the relation between trauma and impaired control over alcohol use was mediated by mindfulness (X2 → M1 → M2) specifically for emotional neglect (EN: standardized indirect effect = 0.025; 95% CI, 0.007, 0.049). Further, the relationship between higher emotional neglect and more drinks per drinking day (X2 → M1 → M2 → Y1) was partially mediated by both lower mindfulness and higher impaired control over alcohol use (EN: standardized indirect effect = 0.006; 95% CI, 0.002, 0.012). In addition, higher levels of mindfulness were indirectly linked to more drinks per drinking day through the mediator of impaired control over alcohol use (M1 → M2 → Y1: indirect effect = − 0.028; 95% CI, − 0.048, − 0.009). Further, higher levels of physical neglect were indirectly linked to drinks per drinking day through the mediator of impaired control over alcohol use (X1 → M2 → Y1; PN1: indirect effect = 0.053; 95% CI, 0.023, 0.090). Higher levels of physical neglect were indirectly linked to more alcohol-related problems through the mediator of impaired control over alcohol use (X1 → M2 → Y2; PN: standardized indirect effect = 0.089; 95% CI, 0.040, 0.144). Interestingly, higher levels of mindfulness were indirectly linked to lower levels of alcohol-related problems through the mediator of lower impaired control over alcohol (M1 → M2 → Y2: standardized indirect effect = − 0.046; 95% CI, − 0.077, − 0.016).

Discussion

This study shows the importance of examining mindfulness and impaired control over drinking. We found that mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use partially mediated the relationship between traumatic childhood events and alcohol-related outcomes among college students, specifically for emotional neglect. These findings illuminate the relationship among facets of childhood trauma, lower mindfulness and greater impaired control over alcohol use. Previous research points towards strong associations of mindfulness reducing both effects of trauma and drinks per drinking day, separately (Baslet and Hill 2011; Boughner et al. 2016; Goodman and Calderon 2012; Neziroglu and Donnelly 2013; Schoorl et al. 2015); however, the present findings link trauma, alcohol use/problems, and mindfulness together through impaired control over alcohol use, which should be examined further in future research.

Greater impaired control over alcohol use was significantly related to more alcohol-related problems, which is consistent with previous literature (Leeman et al. 2009, 2012; Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez 2006). Interestingly, impaired control over alcohol use was a strong mediator between total mindfulness scores and the two alcohol-related outcomes. Higher mindfulness scores were related to both fewer drinks per drinking day and alcohol problems with lower levels of impaired control over alcohol use as a mediator. This suggests that although higher levels of mindfulness can help reduce drinking (Brett et al. 2018), these drinking outcomes are influenced to a great extent by rates of impaired control over alcohol, thus making it an important target for interventions.

We hypothesized that every facet of trauma would be inversely related to mindfulness (i.e., higher trauma, lower mindfulness), however we were surprised to find that higher levels of physical abuse related to higher levels of mindfulness. Future research should examine how resiliency contributes to this relationship, given that individuals with higher resiliency can show positive psychosocial functioning in adulthood even after childhood physical or sexual abuse (Rutter 2007). Conversely, greater emotional neglect related to lower mindfulness levels. This is consistent with our hypothesis and prior findings that have shown mindfulness may alter, or buffer, responses to trauma (Stratton 2006). These associations may be due to more mindful individuals being able to decrease hyperarousal and differentiate past traumatic memories from present moments (Goodman and Calderon 2012), either of their own volition (Bravo et al. 2016), or through use of mindfulness practices (Mermelstein and Garske 2015).

Finally, as hypothesized, there was a strong association between impaired control over alcohol use and childhood traumatic events, specifically physical and emotional neglect. There was very little evidence in the previous literature to support the present finding linking impaired control over alcohol use to childhood trauma. There is support theoretically through the self-medication hypothesis, that emerging adults who experience traumatic childhood events may engage in risky substance use as a maladaptive coping strategy to avoid negative emotions (Allem et al. 2015; Hersh and Hussong 2009), and that trauma manifests in risky behaviors such as excessive drinking (Schwandt et al. 2013). However, these prior findings do not speak specifically to relationships between impaired control over alcohol use and childhood trauma. This is an important finding because risks resulting from impaired control over alcohol use in addition to risks associated with childhood traumas make the subset of college students who experience both particularly vulnerable to greater alcohol involvement and related problems (Arnekrans et al. 2018; Carr et al. 2013; Schore 2009).

Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be considered. First, these data were cross-sectional, thus we cannot speak directly to any causal factors. We used self-report measures for behaviors and experiences, therefore the accuracy of these reports cannot be known. Further, a majority of the sample was college aged or in their early 20s, thereby differing from the general population. About 20% of the sample reported heavy drinking within the past year, which is below other published rates in this study population (NIAAA 2015b). Therefore, a sample with more heavy drinkers may yield different results and should be examined in future research. Limitations aside, the overall consumption of alcohol and other drug use reported by our sample was, nonetheless, sufficient for us to learn more about the relationships of interest in this study.

Our findings suggest that mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use are important mediators of the indirect relationship between childhood trauma and drinking outcomes. Given the strong, direct, inverse relationship we found between mindfulness and impaired control over alcohol use, we view mindfulness as a helpful skillset to develop as a means to increase adherence to drinking limits even in spite of traumatic childhood events. Mindfulness-based interventions have been developed to increase awareness of the present moment and decrease emotional reactivity to stress, both of which are beneficial to those who are dealing with trauma (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction, Kabat-Zinn 1982; and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, Witkiewitz et al. 2005). Further, mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to reduce alcohol use (Chiesa and Serretti 2014; Witkiewitz et al. 2014; Zgierska et al. 2009), specifically among college students (Bramm et al. 2013; Mermelstein and Garske 2015; Roos et al. 2015). Finally, since we know that mindfulness can also be used for reducing adverse reactions to traumas (Baslet and Hill 2011; Neziroglu and Donnelly 2013; Schoorl et al. 2015), combining stress reduction for trauma with mindfulness interventions may be a valuable combination going forward. As we disentangle the complex relationships among childhood trauma, impaired control over alcohol use, and substance use, these results offer valuable insight for tailoring interventions to limit drinking among individuals who have struggled with traumatic events early in life.

Funding Information

This study was funded by NIH/NIAAA grant K01AA024160-01A1 to Julie A. Patock-Peckham and Burton Family Foundation’s (FP11815) grant to Social Addictions Impulse Lab (SAIL), NIH/NIAAA grant R21AA023368, NIH/NIAAA award UH2 AA026214, and support from the Mary F. Lane endowed professorship and the state of Florida to Robert Leeman.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Arizona State University institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the original study.

References

- Allem JP, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L, & Unger JB (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and substance use among Hispanic emerging adults in Southern California. Addictive Behaviors, 50, 199–204. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5® (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Arnekrans AK, Calmes SA, Laux JM, Roseman CP, Piazza NJ, Reynolds JL, et al. (2018). College students’ experiences of childhood developmental traumatic stress: resilience, first-year academic performance, and substance use. Journal of College Counseling, 21(1), 2–14. 10.1002/jocc.12083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, & Allen KB (2004). Assessment of mindfulness by self-report: the Kentucky inventory of mindfulness skills. Assessment, 11(3), 191–206. 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, & Toney L (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baslet G, & Hill J (2011). Case report: brief mindfulness-based psychotherapeutic intervention during inpatient hospitalization in a patient with conversion and dissociation. Clinical Case Studies, 10(2), 95–109. 10.1177/1534650110396359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughner E, Thornley E, Kharlas D, & Frewen P (2016). Mindfulness-related traits partially mediate the association between lifetime and childhood trauma exposure and PTSD and dissociative symptoms in a community sample assessed online. Mindfulness, 7(3), 672–679. 10.1007/s12671-016-0502-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, & Back SE (2012). Childhood trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 34(4), 408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramm SM, Cohn AM, & Hagman BT (2013). Can preoccupation with alcohol override the protective properties of mindful awareness on problematic drinking? Addictive Disorders and Their Treatment, 12, 19–27. 10.1016/j.surg.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Boothe LG, & Pearson MR (2016). Getting personal with mindfulness: a latent profile analysis of mindfulness and psychological outcomes. Mindfulness, 7(2), 420–432. 10.1007/s12671-015-0459-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brett EI, Espeleta HC, Lopez SV, Leavens EL, & Leffingwell TR (2018). Mindfulness as a mediator of the association between adverse childhood experiences and alcohol use and consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 84, 92–98. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Shahar B, Szepsenwol O, & Jacobs WJ (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy improves emotional reactivity to social stress: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 365–380. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CP, Martins CMS, Stingel AM, Lemgruber VB, & Juruena MF (2013). The role of early life stress in adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic review according to childhood trauma subtypes. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(12), 1007–1020. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal F, & Lerma-Cabrera JM (2015). Alcohol consumption among adolescents—implications for public health. America, 16(8.86), 13–47. 10.5772/58930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, & Serretti A (2014). Are mindfulness-based interventions effective for substance use disorders? A systematic review of the evidence. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(5), 492–512. 10.3109/10826084.2013.770027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ (1956). Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 17, 296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, & van der Kolk BA (2012). Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 187. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Gleaves DH, Dorahy MJ, Loewenstein RJ, Cardena E, et al. (2012). Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(3), 550. 10.1037/a0027447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JL, Petretic-Jackson PA, & Ting L (2001). Intimacy dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: long-term correlates of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14(1), 63–79. 10.1023/A:100783553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme J, Koverola C, & Battle P (1997). Intimacy development: the influence of abuse and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(4), 590–599. 10.1177/088626097012004007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RD (2000). Childhood maltreatment and college drop-out rates. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 987–995. 10.1177/088626000015009005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, & Tibshirani RJ (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AC, Wood MD, Stein LA, & Rossi JS (2010). Measuring mindfulness and examining its relationship with alcohol use and negative consequences. Psychology ofAddictive Behaviors, 24, 608–616. 10.1037/a0021742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, & Turner MG (2000). The sexual victimization of college women. Research report 182369. Washington, DC: U. S. Dept. of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM (2014). Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: integrating contemplative practices. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz M, & MacKinnon D (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R, & Calderon A (2012). The use of mindfulness in trauma counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(3), 254–268. 10.17744/mehc.34.3.930020422n168322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Tebbutt JS, Mattick RP, & Zamir R (1993). Development of a scale for measuring impaired control over drinking consumption: a preliminary report. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54(6), 700–709. 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh MA, & Hussong AM (2009). The association between observed parental emotion socialization and adolescent self-medication. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(4), 493–506. 10.1007/s10802-008-9291-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, & Sher KJ (1992). Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health, 41(2), 49–58. 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP, Palfai TP, & Wood MD (2004). Mapping the continuum of alcohol problems in college students: a Rasch model analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(4), 322. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam EG, Friedman MJ, Hill ED, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, & Koenen KC (2014). Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the world mental health (WMH) surveys. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 130–142. 10.1002/da.22169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC, & McEachern AG (2000). Prevalence and characteristics of childhood sexual abuse in multiethinic female college students. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 9(2), 57–70. 10.1300/J070v09n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Toll BA, Taylor LA, & Volpicelli JR (2009). Alcohol-induced disinhibition expectancies and impaired control as prospective predictors of problem drinking in undergraduates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 553. 10.1037/a0017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Patock-Peckham JA, & Potenza MN (2012). Impaired control over alcohol use: an under-addressed risk factor for problem drinking in young adults? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(2), 92–106. 10.1037/a0026463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly BF (1997). Randomization, bootstrap, and Monte Carlo methods in biology (2nd ed.p. 399). New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein LC, & Garske JP (2015). A brief mindfulness intervention for college student binge drinkers: a pilot study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(2), 259. 10.1037/adb0000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, & Malinowski P (2009). Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(1), 176–186. 10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, DeMartini KS, Foster D, Patock-Peckham J, Garrison KA, Corlett PR, Krystal JH, Krishan-Sarin S, & O’Malley SS (2018). The Self-Report Habit Index: assessing habitual marijuana, alcohol, e-cigarette, and cigarette use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 207–214. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, & MacKillop J (2012). Living in the here and now: interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology, 219, 527–536. 10.1007/s00213-011-2573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2017). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2007). Statistical analysis with latent variables using Mplus. (version 3). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Naidu ES, Patock-Peckham JA, Ruof A, Bauman DC, Banovich P, Frohe T, & Leeman RF (2019). Narcissism and devaluing others: an exploration of impaired control over drinking as a mediating mechanism of alcohol-related problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2015a). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/alcohol-facts-and-statistics. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2015b). College drinking. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/college-drinking. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

- Neziroglu F, & Donnelly K (2013). Dissociation from an acceptance-oriented standpoint. In Kennedy F, Kennerley H, & Pearson D (Eds.), Cognitive behavioural approaches to the understanding and treatment of dissociation (pp. 236–250). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, & Sloan LB (2014). Epidemiology or trauma and PTSD. In Friedman MJ, Keane TM, & Resick PA (Eds.), Handbook of PTSD: science and practice (2nd ed., pp. 100–120). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, & Morgan-Lopez AA (2006). College drinking behaviors: mediational links between parenting styles, impulse control, and alcohol-related outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(2), 117. 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Brown DB, Bravo AJ, & Witkiewitz K (2015). Staying in the moment and finding purpose: the associations of trait mindfulness, decentering, and purpose in life with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and alcohol-related problems. Mindfulness, 6, 645–653. 10.1007/s12671-014-0300-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Pearson MR, & Brown DB (2015). Drinking motives mediate the negative associations between mindfulness facets and alcohol outcomes among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 176–183. 10.1037/a0038529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman EF, Dejong W, Palfai T, & Saitz R (2008). Relationship of age of first drink to alcohol-related consequences among college students with unhealthy alcohol use. Substance Abuse, 29(1), 33–41. 10.1300/J465v29n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (2007). Resilience, competence, and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(3), 205–209. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders S (1986). The perceptual alteration scale: a scale measuring dissociation. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 29(2), 95–102. 10.1080/00029157.1986.10402691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoorl M, Van Mil-Klinkenberg L, & Van Der Does W (2015). Mindfulness skills, anxiety sensitivity, and cognitive reactivity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Mindfulness, 6(5), 1004–1011. 10.1007/s12671-014-0364-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN (2009). Relational trauma and the developing right brain: the neurobiology of broken attachment bonds. In Baradon T (Ed.), Relational trauma in infancy (pp. 39–67). London: Routledge. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04474.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schore AN (2014). The right brain is dominant in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 388. 10.1037/a0037083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt ML, Heilig M, Hommer DW, George DT, & Ramchandani VA (2013). Childhood trauma exposure and alcohol dependence severity in adulthood: mediation by emotional abuse severity and neuroticism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(6), 984–992. 10.1111/acer.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Atwoli L, Friedman MJ, Hill ED, & Kessler RC (2014). DSM-5 and ICD-11 definitions of posttraumatic stress disorder: investigating “narrow” and “broad” definitions. Depression and Anxiety, 31, 494–505. 10.1002/da.22279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton KJ (2006). Mindfulness-based approaches to impulsive behaviors. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 4(2), 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, & Tein J (2008). Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 241–269. 10.1177/1094428107300344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & MacKinnon DP (2011). RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43(3), 692–700. 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Dietary guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH, & Schuengel C (1996). The measurement of dissociation in normal and clinical populations: meta-analytic validation of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES). Clinical Psychology Review, 16(5), 365–382. 10.1016/0272-7358(96)00006-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CL, Stangl BL, Schwandt ML, Corey KM, Hendershot CS, & Ramchandani VA (2019). The relationship between impaired control, impulsivity, and alcohol self-administration in nondependent drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10.1037/pha0000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell JD, Quilty LC, & Hendershot CS (2016). Impulsivity, working memory, and impaired control over alcohol: a latent variable analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), 544. 10.1037/adb0000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, & Walker D (2005). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19(3), 211–228. 10.1891/jcop.2005.19.3.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S, Harrop EN, Douglas H, Enkema M, & Sedgwick C (2014). Mindfulness-based treatment to prevent addictive behavior relapse: theoretical models and hypothesized mechanisms of change. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(5), 513–524. 10.3109/10826084.2014.891845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, Kushner K, Koehler R, & Marlatt A (2009). Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Substance Abuse, 30(4), 266–294. 10.1080/08897070903250019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]