Abstract

Fusicoccadiene synthase from the fungus Phomopsis amygdali (PaFS) is an assembly-line terpene synthase that catalyzes the first two steps in the biosynthesis of Fusiccocin A, a diterpene glycoside. The C-terminal prenyltransferase domain of PaFS catalyzes the condensation of one molecule of C5 dimethylallyl diphosphate and three molecules of C5 isopentenyl diphosphate to form C20 geranylgeranyl diphosphate, which then transits to the cyclase domain for cyclization to form fusicoccadiene. Previous structural studies of PaFS using electron microscopy (EM) revealed a central octameric prenyltransferase core with eight cyclase domains tethered in random distal positions through flexible 70-residue linkers. However, proximal prenyltransferase-cyclase configurations could be captured by covalent crosslinking and observed by cryo-EM and mass spectrometry. Here, we use cryo-EM to show that proximally configured prenyltransferase-cyclase complexes are observable even in the absence of covalent crosslinking; moreover, such complexes can involve multiple cyclase domains. A conserved basic patch on the prenyltransferase domain comprises the primary touchpoint with the cyclase domain. These results support a model for transient prenyltransferase-cyclase association in which the cyclase domains of PaFS are in facile equilibrium between proximal associated and random distal positions relative to the central prenyltransferase octamer. The results of biophysical measurements using small-angle X-ray scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation, dynamic light scattering, and size-exclusion chromatography in-line with multi-angle light scattering are consistent with this model. This model accordingly provides a framework for understanding substrate transit between the prenyltransferase and the cyclase domains as well as the cooperativity observed for geranylgeranyl diphosphate cyclization.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The chemodiversity of terpenoid natural products largely derives from catalysis by terpene synthases that catalyze isoprenoid chain elongation and cyclization reactions. Prenyltransferases catalyze chain elongation reactions in which the condensation of C5 dimethylallyl diphosphate and C5 isopentenyl diphosphate building blocks yields increasingly longer isoprenoids, such as the C10 monoterpene geranyl diphosphate (GPP), the C15 sesquiterpene farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and the C20 diterpene geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP).1,2 In turn, these linear, achiral isoprenoids are substrates for terpene cyclases that catalyze the formation of unsaturated hydrocarbon products typically containing one or more rings and stereocenters.3–7 Terpene cyclization reactions serve as critical branch points in secondary metabolism and exemplify the most complex carbon-carbon bond-forming chemistry found in nature.

X-ray crystallography has traditionally informed structure-function relationships for terpene cyclases, starting with the first reported crystal structures of class I and class II terpene cyclases.8–10 These structures revealed that distinct α-helical folds correspond to the chemical strategy required to initiate the cyclization reaction. Class I terpene cyclases initiate catalysis by the metal-triggered departure of the diphosphate leaving group to generate an allylic cation and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi). This chemistry takes place in the α domain of a protein with α, αβ, or αβγ domain architecture;8,9,11–13 the same chemistry is required for the chain elongation reaction catalyzed by prenyltransferases, which adopt single-α domain structures.14,15 Class II terpene cyclases initiate catalysis by the protonation of a carbon-carbon double bond or an epoxide moiety in the isoprenoid substrate to generate a tertiary carbocation.16 This chemistry takes place in the β domain of a protein with β, βγ, or αβγ domain architecture.10,17,18 For each cyclase class, one of the remaining π bonds of the substrate then reacts with the initially formed carbocation in the first ring-closure reaction of a multi-step cyclization cascade.

Several chimeric terpene synthases – bifunctional prenyltransferase-cyclase enzymes with α–α or α–βγ domain architecture – have been discovered in fungi, including fusicoccadiene synthase from Phomopsis amygdali (PaFS). PaFS generates the linear C20 isoprenoid GGPP in the C-terminal α domain, which then undergoes cyclization in the N-terminal α domain to yield fusicoccadiene (Figure 1), a biosynthetic precursor of the phytotoxin Fusicoccin A.19 Most of the GGPP generated by the prenyltransferase domain remains on the enzyme for cyclization to form fusicoccadiene, suggesting that substrate channeling is operative in the full-length enzyme.20 While full-length PaFS is refractory to crystallization, crystal structures have been reported for individual prenyltransferase and cyclase domains.21 These structures inform our mechanistic understanding of catalysis, but they do not reveal how GGPP transits from one active site to another, nor do they reveal how one domain communicates with another in the full-length enzyme.

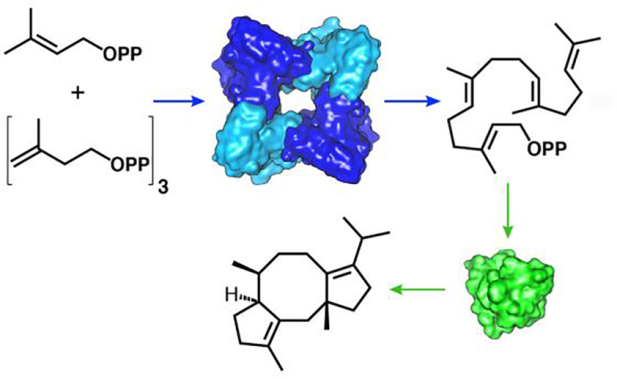

Figure 1.

The 5-carbon substrates dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) are coupled in the octameric prenyltransferase core of PaFS (blue) to yield the 20-carbon product geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), which then transits to the cyclase domain (green) for the generation of fusicoccadiene. The 70-residue inter-domain linker (red coil) between the prenyltransferase and cyclase domains is flexible and disordered. Accordingly, cyclase domains are thought to be in equilibrium between proximal docked (left) and random distal (right) positions. Adapted from: Faylo, J. L., van Eeuwen, T., Kim, H. J. Gorbea Colón, J. J., Garcia, B. A., Murakami, K., Christianson, D. W. (2021) Structural insights on assembly-line terpene biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 3487. Copyright 2021 The Authors.

The use of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) single particle analysis has recently enabled greater insight on structure-function relationships in intact PaFS.22 A 3.99 Å-resolution reconstruction of PaFS reveals only the prenyltransferase domains assembled with well-ordered octameric quaternary structure. Averaging effects hinder visualization of cyclase domain positioning in reconstructions of the prenyltransferase octamer. Raw micrographs show that cyclase domains are randomly splayed out in distal configurations around the prenyltransferase octamer in individual particles, as represented schematically in Figure 1. Even so, single particle analysis of PaFS stabilized by nonspecific crosslinking affords low-resolution cryo-EM snapshots of proximally docked cyclase domains.22 Substrate channeling in PaFS may therefore be explained by diffusion of GGPP from the central prenyltransferase core to a proximally docked cyclase domain, diffusion of GGPP out of the central core to a splayed-out cyclase domain, or a combination of both possibilities. Dynamic cluster channeling23,24 may be operative, such that the agglomeration effect of higher-order oligomerization induces proximity of multiple active sites that catalyze consecutive reactions, even as active sites that catalyze the second reaction are highly mobile while tethered to the central prenyltransferase octamer.

It could be argued that the proximally docked cyclase-prenyltransferase interactions observed in crosslinked PaFS could be artifacts of covalent linkages. To address this concern, we now report cryo-EM studies of PaFS in the absence of crosslinking reagents and in the presence of cofactor Mg2+ and pamidronate (a bisphosphonate inhibitor). Importantly, reconstructions reveal that one or more cyclase domains can associate closely with the prenyltransferase octamer under these conditions. These observations support our proposal22 that multiple cyclase domains can transiently interact with the central prenyltransferase octamer. Accordingly, these observations yield a model for bifunctional enzyme catalysis that can serve as a framework for studying – and perhaps engineering – substrate transit in assembly-line terpene synthases.

Methods

Protein preparation.

Full-length PaFS was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Novagen) grown at 37°C with aeration following inoculation of 6 × 1L 2xYT medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and 30 μg/mL chloramphenicol with 5 mL of starting culture.22 When optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.8, cells were induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C followed by 18 h expression. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in buffer A [50 mM K2HPO4 (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP)]. After lysis by sonication, cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation and loaded on a Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare). Protein was eluted with 0–400 mM imidazole gradient in buffer A. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, combined, and loaded onto a size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer B [50 mM Tris (pH 7.7), 200 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1.5 mM TCEP]. Protein was approximately 99% pure as judged by SDS-PAGE. Prior to the preparation of grids for electron microscopy (EM) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), PaFS was dialyzed into buffer C [50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP].

Cryo-EM data collection.

Aliquots (3 μL) of protein solution [0.4 mg/mL PaFS in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM pamidronate, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP] were used to prepare grids in batches by manual blotting for 3 s using Whatman Grade 41 filter paper (Sigma-Aldrich) with a Leica EM CPC manual plunger (Leica Microsystems). Representative grids were first screened on a FEI Talos Arctica microscope operating at 200 kV equipped with a K2 direct electron detector (Pacific Northwest Cryo-EM Center). Grids were then imaged on a Titan Krios electron microscope (Thermo Fischer Scientific) operating at 300 keV at the Pacific Northwest Cryo-EM Center. Images were recorded using a K3 direct electron detector at 105,000x magnification in super-resolution mode (0.415 Å per pixel, nominally 0.83 Å per physical pixel) and defocus from 1.0–2.5 μm, using SerialEM data collection software.25 Specifically, 100-frame exposures were taken at 0.02 s/frame, using a dose rate of 18 e–/pixel/s (0.52 e–/Å−2/frame). A total of 15,783 movies were recorded from three grids. Data collection statistics are recorded in Tables S1–S5.

Cryo-EM data processing and analysis.

Motion correction (MotionCor2)26 and contrast transfer function (CTF) estimation (CTFFind 4.1)27 were performed using Relion (version 3.0.7)28 during which micrographs were binned by 2, resulting in a pixel size of 0.83 Å/pixel. Particle picking and initial classification was performed with cryoSPARC (version 2.15):29 six million particles were automatically picked with a template-based picker, of which 1.3 million inspected particles were extracted binned by 2, with a resulting box of 192 pixels (318.7 Å) in length. Particles subjected to 2D classification showed an octamer with clear secondary structure consistent with previous results (Figure S1).22 After removal of junk particles, the resulting 201,709 particles were imported to Relion using Pyem.30 Rounds of 3D refinement were iterated with CTF refinements, generally following reported methods to reduce B factors and increase resolution.31 Briefly, CTF refinements estimating beamtilt, 4th order aberrations, as well as per particle defocus and astigmatism were iterated with Bayesian polishing in Relion.28 Prior to the final refinement, the particle set was rebalanced to remove overrepresented Euler angles using a custom script written by Prof. Michael Cianfrocco (https://github.com/leschzinerlab/Relion) resulting in a final set of 151,710 particles. The final particle set was subjected to non-uniform refinement32 in cryoSPARC (version 3.3.1) to yield the final 3.73-Å resolution reconstruction. The complete workflow is summarized in Figure S1. Following our previously reported cryo-EM reconstruction of full-length PaFS, C2 symmetry was imposed in refinements.22 Local resolution analysis showed that the prenyltransferase core could be resolved at resolutions ranging from 3.6–5 Å. DeepEMhancer was used as a final post-processing step.33

Model building and refinement.

Structure refinement was performed using Phenix (version dev-3736).34 Using UCSF Chimera,35 atomic coordinates from each chain A–H from our previously reported 3.99-Å resolution cryo-EM structure of the prenyltransferase octamer (PDB 7JTH) were individually docked into the 3D reconstruction of the present study. This was used as the starting model for iterative rounds of refinement with Phenix Real Space Refine34 followed by model building of the asymmetric unit (chains A–D) in Coot.36 For real-space refinement, the resolution was set to 3.73 Å. Phenix Map Symmetry was used to calculate C2 symmetry operators, and Phenix Apply NCS was used to apply calculated symmetry operators to generate the final model of the octamer. Phenix comprehensive validation was used to evaluate model quality as summarized in Table S1. UCSF Chimera35 was used to generate figures of the model and map.

After consensus reconstruction, particles were subjected to further 3D classification to explore the possibility of cyclase domains associated with the prenyltransferase octamer. To resolve putative cyclase domains, the best class was chosen with 79,488 particles containing evidence for cyclase domain density. Symmetry expansion utilizing C4 symmetry was performed to yield 317,952 particles, after which partial signal subtraction34 was employed with the mask surrounding the octameric core. A mask calculated from the crystal structure of the cyclase domain crystallographic dimer (PDB 5ER8)21 modeled on the side of the octamer was then used in alignment-free masked 3D classification. Entire particles from two selected classes were refined to yield symmetry-expanded (SE) reconstructions A and B of the octamer with a single cyclase domain at two slightly different positions. A reconstruction was also calculated using combined particles from both SE classes to yield the PaFS octameric core with the consensus density of a single cyclase domain at 6.0 Å resolution. The complete workflow is summarized in Figure S2.

Partial signal subtraction and masked 3D classification37,38 were simultaneously performed without symmetry expansion, using the equivalent prenyltransferase octamer and cyclase dimer masks for subtraction and 3D classification, respectively. The cyclase dimer mask was positioned by 90, 180, and 270° rotation about the central octamer pore for targeted analysis of the “north”, “south”, “east”, and “west” sides of the octamer in alignment-free 3D classification. With each iteration, classes showing clear cyclase density were individually selected comprising 5,000–10,000 particles; entire particles were refined to yield asymmetric reconstructions of the PaFS octameric core with single cyclase domains at a total of fifteen different positions. A workflow is shown in Figure S3 that details particle number and the resolution of each reconstruction.

To resolve density for neighboring cyclase domains at each cardinal direction, the subtracted particles from selected classes were combined and subjected to three separate further rounds of masked 3D classification: cyclase dimer masks rotated about the central octamer pore were used in iterative classifications searching for density corresponding to neighboring cyclase domains. In each round, 3–4 classes containing 3,000–5,000 particles exhibited density corresponding to neighboring cyclase domains; entire particles combined from classes containing converging cyclase density yielded initial reconstructions at 9–10 Å-resolution with two associated cyclase domains visible. A final round of masked 3D classification of entire particles, with image alignment, allowed removal of junk particles and final refinement of the PaFS prenyltransferase octamer reconstruction with multiple associated cyclase domains. A workflow detailing the refinement strategy is shown in Figure S4. Reconstruction statistics for all models with associated cyclase domains are recorded in Tables S2–S5.

Size-exclusion chromatography in-line with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS).

Experiments were conducted at the Johnson Foundation Structural Biology and Biophysics Core at the Perelman School of Medicine (Philadelphia, PA). PaFS was concentrated to 6.2 mg/mL and dialyzed into SEC-MALS buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP]. The SEC experiments were performed using 100 μL injections with a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) at 0.5 mL/min at room temperature. Absolute molecular weights were determined by MALS. The scattered light intensity of the column eluent was recorded at 18 different angles using a DAWN-HELEOS MALS detector (Wyatt Technology Corp.) operating at 658 nm after calibration with the monomer fraction of Type V bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma). The protein concentration of the eluent was determined using an in-line Optilab T-rex interferometric refractometer (Wyatt Technology Corporation). The weight-averaged molecular weight of species within defined chromatographic peaks was calculated using the software ASTRA, version 8.0 (Wyatt Technology Corporation), by construction of Debye plots [(KC/Rθ versus sin2(θ/2)] at 1/S data intervals. The weight-averaged molecular weight was then calculated at each point of the chromatographic trace from the Debye plot intercept, and an overall average molecular weight was calculated by averaging across the peak. The column was calibrated using the following proteins (Bio-Rad): thyroglobulin (670 kDa, Rs = 85 Å), gamma-globulin (158 kDa, Rs = 52.2 Å), ovalbumin (44 kDa, Rs = 30.5 Å), myoglobin (17 kDa, Rs = 20.8 Å), and Vitamin B12 (1,350 Daltons). Blue-Dextran (Sigma) was used to define the void volume of the column.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS).

Experiments were conducted using a Zetasizer Nano ZS DLS instrument (Malvern Panalytical). The DLS sample [1 mg/mL PaFS, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP] was analyzed in a 900 μL sample volume. A 630 nm light source was used, and scattered light was detected at a 173° angle. Data were recorded and evaluated using Zeta software provided with the instrument. Autocorrelation curves were fit using the Stokes-Einstein equation with a sphere model; data were rendered using Prism GraphPad.

Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC).

Sedimentation velocity-analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) experiments were performed at 25°C with an XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA) and a TiAn60 rotor with two-channel charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces and quartz windows. Experiments were performed in SEC-MALS buffer using PaFS concentrations of 5 and 10 μM (OD280 of 0.5 and 1.0, respectively). Data were collected at 25°C with detection at 280 nm. Complete sedimentation velocity profiles were recorded every 30 s at 40,000 rpm. Data were fit using the c(s) distribution model of the Lamm equation as implemented in the program SEDFIT.39

Sedimentation equilibrium-analytical ultracentrifugation (SE-AUC) experiments were performed at 4°C with an XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, C.A., U.S.A.) and a TiAn60 rotor with six-channel charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces and quartz windows. Sedimentation equilibrium data were collected at 4°C with detection at 280 nm for three sample concentrations. Analyses were carried out using global fits to data acquired at multiple speeds for each concentration with strict mass conservation using the program SEDPHAT.40 Error estimates for equilibrium constants were determined from a 1,000-iteration Monte Carlo simulation.

Prior to analysis, PaFS was dialyzed into SEC-MALS buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP]. For the analysis of a PaFS-inhibitor complex, MgCl2 and pamidronate were added to final concentrations of 1.0 mM. For all AUC analyses, the partial specific volume (ῡ), solvent density (ρ), and viscosity (η) were derived from chemical composition by SEDNTERP.41 Theoretical hydrodynamic parameters were calculated using WinHYDROPRO.42 Figures were prepared with the program GUSSI.43

Small-angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS).

SAXS data were collected at beamline 16-ID (LiX) of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (Upton, NY).44 Data were collected at a wavelength of 1.0 Å in a three-camera conformation, yielding accessible scattering angle with 0.005 < q < 3.0 Å−1, where q is the momentum transfer, defined as q = 4π sin(θ)/ λ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength and 2θ is the scattering angle. The data to q < 0.5 Å−1 were used in subsequent analyses. Samples were loaded into a 1-mm capillary for ten 1-s X-ray exposures. All measurements were performed in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM TCEP.

SAXS data were analyzed using the program RAW.45 When fitting manually, the maximum diameter of the particle (Dmax) was incrementally adjusted in GNOM46 to maximize the goodness-of-fit parameter, to minimize the discrepancy between the fit and the experimental data, and to optimize the visual qualities of the distribution profile. To facilitate comparison of atomic models to small-angle scattering data, atomistic models representing the complete composition of the protein were constructed, and the resulting model was gradually relaxed by energy minimization with NAMD,47 using CHARMM42 force fields.

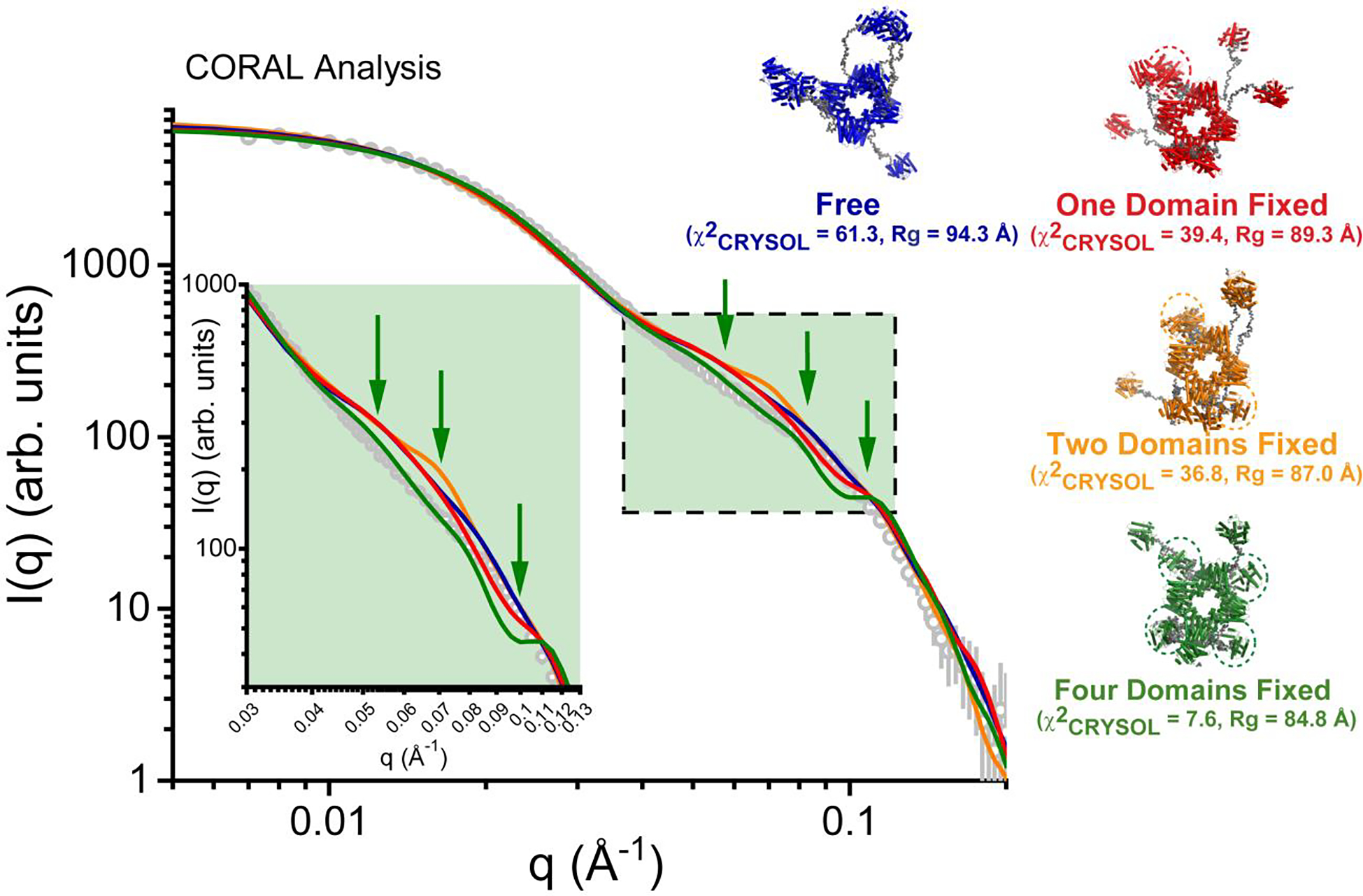

Hybrid bead-atomistic modeling of PaFS was performed using the program CORAL,48 where the known structure was fixed in composition and residues not resolved by X-ray crystallography were modeled as coarse grain beads. Ten independent calculations for each protein were performed and yielded comparable results. Final models were assessed using the program CRYSOL.49 Models were rendered using the program PYMOL.50

Calculation of hydrodynamic properties.

A distal model of the octamer, with eight cyclase domains arbitrarily positioned in extended configurations, was created using NAMD,47 and models properties were calculated using the program HULLRAD.51 For the proximal model, a density map representing eight proximal docked cyclase domains was created by merging; the hydrodynamic properties of this model were calculated using the program HYDROMIC.52 Figures showing the distal and proximal models were created using ChimeraX.53

Results

The cyclase associates with a basic patch on the prenyltransferase.

Initial 2D classes revealed the characteristic PaFS prenyltransferase octamer; as expected, cyclase domains were not readily observed, likely due to the majority being randomly splayed out from the prenyltransferase core. Through the workflow summarized in Figure S1, these data yielded a 3.73 Å resolution density map of the prenyltransferase octamer refined with C2 symmetry (Figure 2a), representing a slight improvement over the recently reported 3.99 Å-resolution map of the octamer.22 In the present study, the local resolution ranges from 3.1–6.0 Å (Figure 2b), improving upon our previous reconstruction which ranged from 3.7–9.0 Å resolution.22 In the present study, as in the previous, the lowest resolution region is confined to solvent-exposed loop regions (Figure 2b).

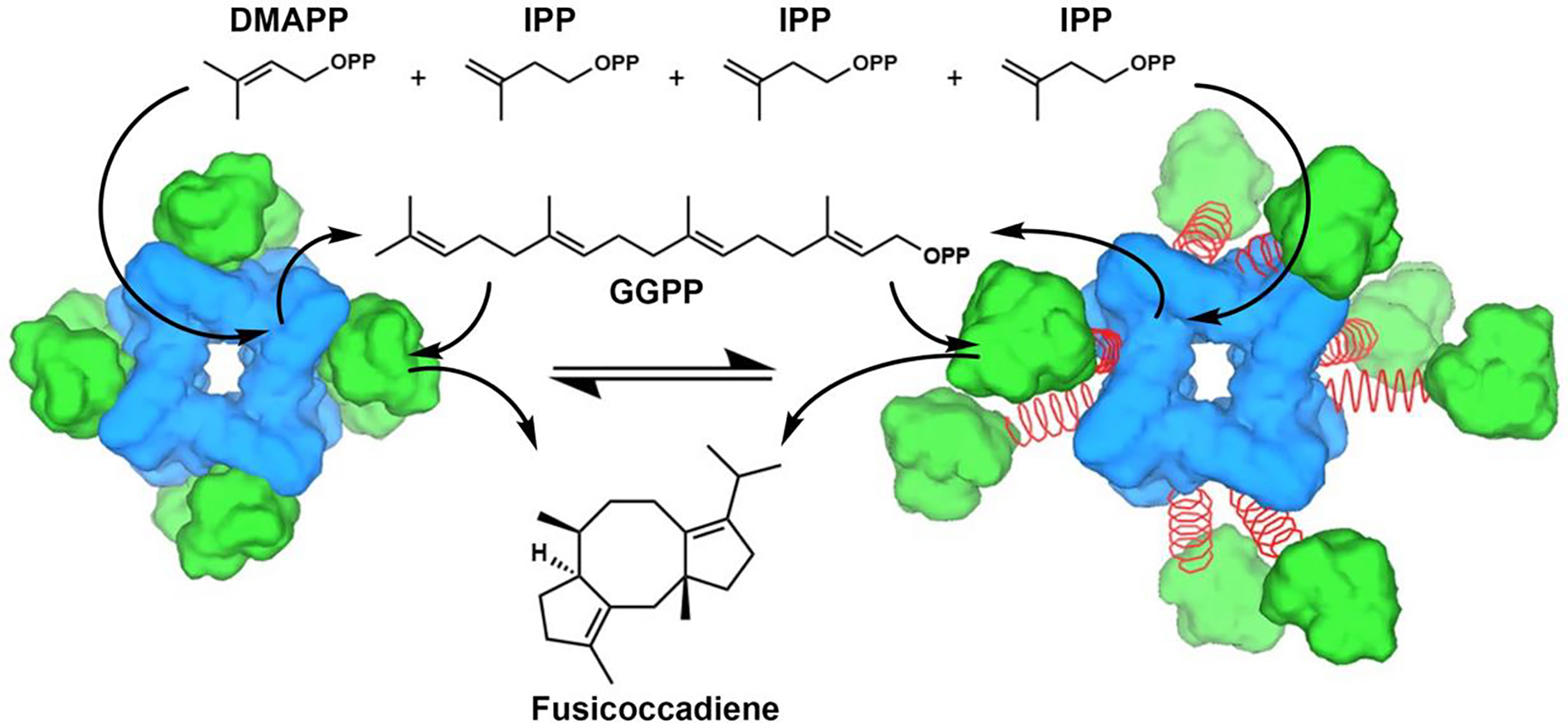

Figure 2.

(a) Cryo-EM reconstruction of the octameric PaFS prenyltransferase domain at 3.73-Å resolution. The selected helix depicted in the blue box is highlighted with atomic model fit to show representative side chain resolution. The complete workflow for structure determination is shown in Figure S1. (b) Local resolution map of the PaFS prenyltransferase octamer reconstruction with C2 symmetry, depicted according to the scale shown in Å at Fourier shell correlation (FSC) 0.5. (c) Cryo-EM reconstruction fit with the refined atomic model. Monomers A/A’ and B/B’ are blue and cyan, respectively (d) Superpositions of the 3.73 Å-resolution structure of the octamer with the previously reported 3.99 Å-resolution structure (PDB 7JTH). (Left) Superposition of chain A of PDB 7JTH (gray) with chain A in the present study (blue) shows that no major conformational differences are apparent at slightly higher resolution (1.3 Å rmsd for 294 Cɑ atoms). (Middle) Superposition of dimers from PDB 7JTH (gray) and the present study (chain A, blue; chain B, cyan) shows slight structural differences (1.8 Å rmsd for 575 Cɑ atoms). (Right) Superposition of asymmetric units from PDB 7JTH (gray) and the present study (chains A and C, blue; chains B and D, cyan) reveals additional modest structural differences between interacting dimer units (2.6 Å rmsd for 1141 Cɑ atoms).

The 3.73 Å-resolution structure of the octamer (Figure 2c) is generally similar to that determined at 3.99 Å resolution22 (PDB 7JTH), with a root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of 1.3 Å for 294 Cɑ atoms between monomer A in each structure (Figure 2d). Consistent with prior results,22 helices Hɑ-2 and Hɑ-3 cap the active site and also mediate dimer-dimer interactions in the octamer; these flexible helices are observed at lower local resolution relative to neighboring regions (Figure 2b). Accordingly, a 1.8 Å rmsd (575 Cɑ atoms) between the A-B dimer of PDB 7JTH and that of the present study appears mostly due to movement of capping helices Hɑ-2 and Hɑ-3; more broadly, as solvent exposure increases and local resolution decreases, greater deviation is seen with the previously reported structure (Figures 2c,d). Alignment of the asymmetric unit (chains A, B, C, and D) with that of PDB 7JTH shows an rmsd of 2.6 Å for 1141 Cɑ atoms. This alignment reveals that while the structure of each individual chain remains well-conserved, the quaternary structure of the PaFS prenyltransferase octamer of PaFS is subject to flexibility. Specifically, chains A and C appear to undergo a modest ~2 Å shift outward, impacting dimer-dimer interactions mediated by the FG loop (Figure 2d). Although protein samples were prepared with Mg2+ and pamidronate (a bisphosphonate inhibitor of prenyltransferases), no density is observed for bound inhibitor or metal ions, perhaps due to the modest 3.73 Å resolution of the structure determination.

Reconstructions viewed at lower density contour levels in maps refined with C1 symmetry revealed weak but persistent density corresponding to a cyclase domain on each of the four sides of the prenyltransferase octamer (Figure S2). By employing symmetry expansion, partial signal subtraction, and masked 3D classification, these “side densities” became more prominent. We found that 34,614 particles out of 317,952 particles (11%) exhibited such side densities. This is a lower percentage than the 45% of particles with side densities in glutaraldehyde-crosslinked PaFS.22 Even so, we show here for the first time that prenyltransferase-cyclase association can be observed even in the absence of covalent crosslinking and in the presence of pamidronate and Mg2+.

With this method, two symmetry expanded (SE) reconstructions for side densities at slightly different positions were generated at 6.4 and 6.8 Å resolution. A consensus refinement combining particles from both classes yielded a 6.0 Å-resolution map, with modestly improved resolution of the prenyltransferase core showing clear density for prenyltransferase helices (Figure S2). Local resolution calculations indicate that the resolution of the prenyltransferase core ranges from 5–9 Å; the local resolution of the single cyclase domain ranges from 12–19 Å. This represents an improvement over the 22–26 Å local resolution of single cyclase domain density observed in the cryo-EM structure of crosslinked PaFS.22

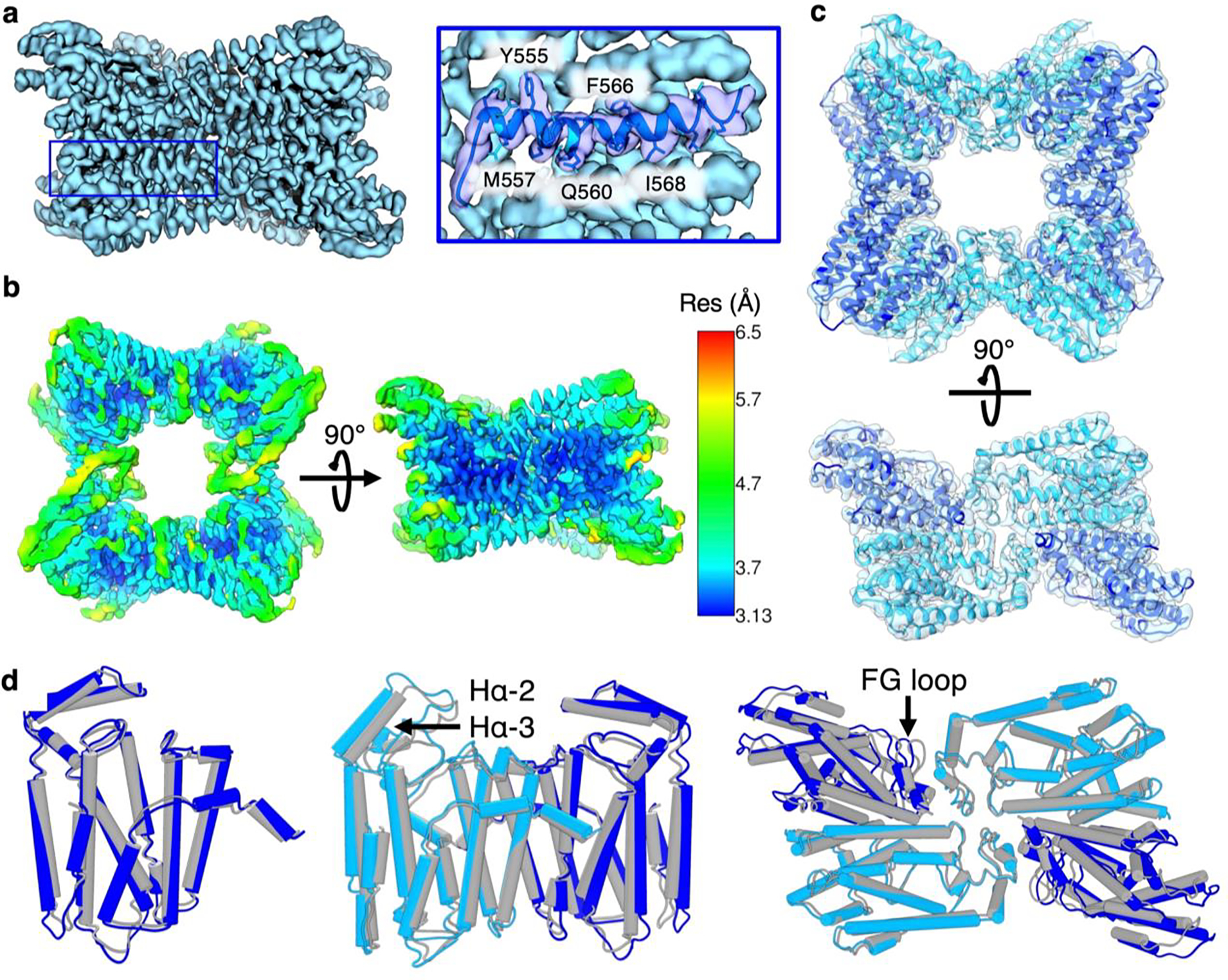

Superposition of the 6.4 Å-resolution and 6.8 Å-resolution symmetry-expanded maps (SE class A and SE class B, respectively) reveals that the side densities do not precisely overlap. However, rotation of one map relative to the other by 180° yielded good overall superposition of the prenyltransferase with consistent positioning of the associated cyclase domain (Figure 3a,b). A basic patch defined by R583, K585, R592, and R698 comprises a generally conserved touchpoint between the prenyltransferase and cyclase domains (Figure 3c). In a related assembly-line terpene synthase, hexameric copalyl diphosphate synthase, a segment of the interdomain linker is observed to associate with the corresponding region of its prenyltransferase.54 Thus, this basic patch is implicated more generally in mediating interactions with the prenyltransferase in assembly-line terpene synthases.

Figure 3.

Symmetry expansion and masked classification enables the generation of two distinct reconstructions of PaFS cyclase domains. (a) Two 3D classes were found with converging cyclase domain density on the side of the prenyltransferase octamer. Class A (blue) and class B (cyan) entire particles were separately refined to yield 6.4 and 6.8 Å resolution reconstructions, respectively. Reconstructions are shown superimposed with corresponding 3D classification of subtracted particles. These two maps are overlaid (far right), showing that cyclase domain density is mostly non-overlapping between the two classes. The workflow for structure determination is outlined in Figure S2. (b) Rotation of the SE Class A map relative to the SE Class B map shows that cyclase domain position is conserved between opposite chains. (c) Satellite density in the SE Class A reconstruction can fit a cyclase domain monomer (PDB 5ER8, chain A) (green), and exhibits consistent density corresponding to a narrow prenyltransferase-cyclase interface (black box). The electrostatic surface potential of the prenyltransferase domain (PDB 7JTH) highlights a basic patch comprised of R583, K585, R592, and R698 at the prenyltransferase-cyclase interface (center). The electrostatic surface potential of the cyclase domain (right) fit into the 12–19 Å local resolution cryo-EM density map reveals that a complementary acidic patch on the cyclase domain could facilitate prenyltransferase-cyclase association.

Multiple cyclase domains can associate with the prenyltransferase octamer.

As mentioned previously, a 3D reconstruction calculated with no presumption of molecular symmetry (i.e., particles classified with C1 symmetry) revealed a prenyltransferase octamer with weak, extraneous density on all four sides of the prenyltransferase octamer (Figure S2). We hypothesized that focused classification would enable observation of discrete cyclase conformations on all four sides of the octamer. We further suspected that some particles might reveal density for two or more associated cyclase domains.

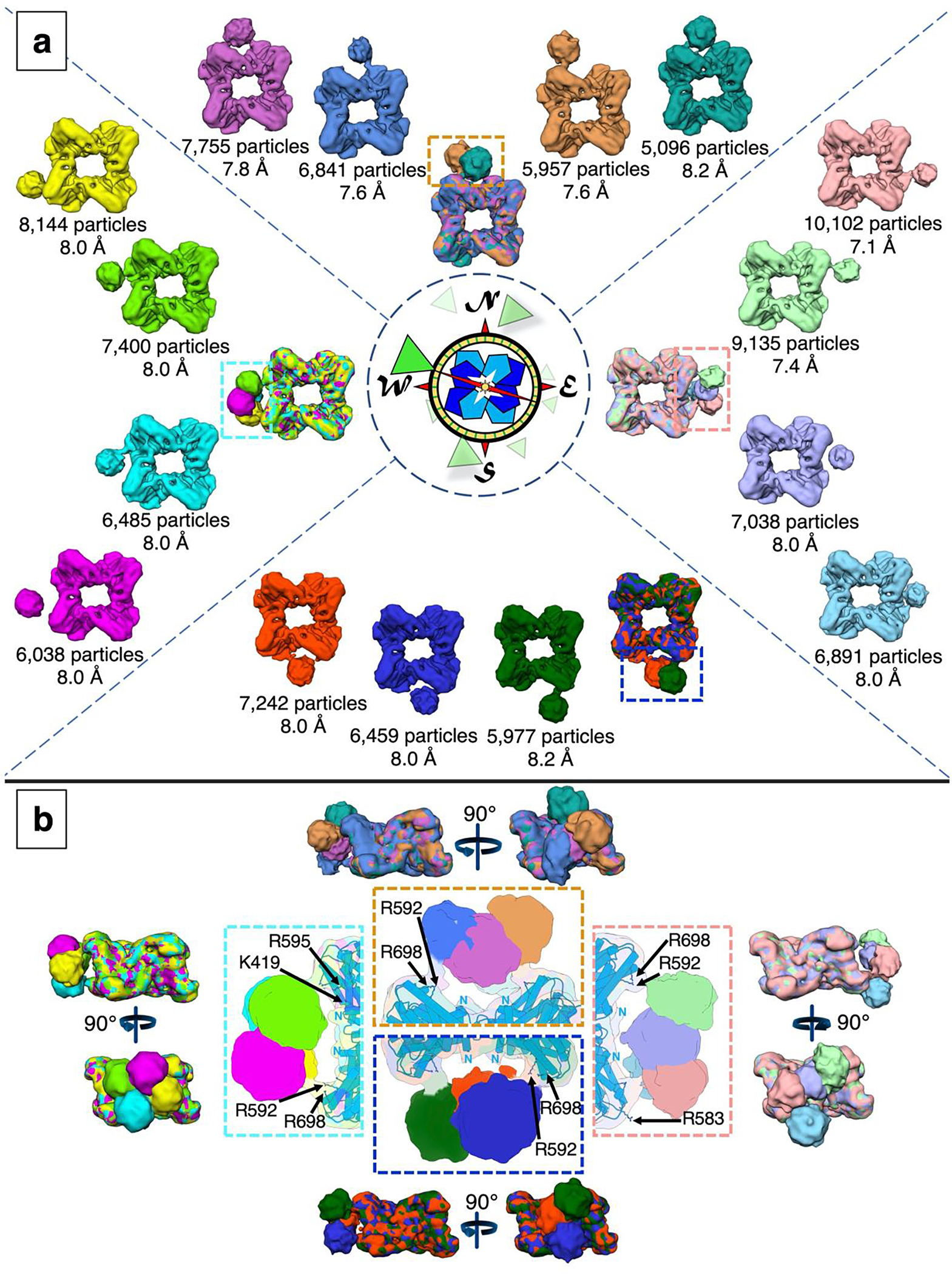

In our approach to focused classification, particles were first assessed for converging density on each side of the prenyltransferase octamer, designated here by the cardinal directions of north (N), south (S), east (E), and west (W). This analysis revealed 3–4 positions for cyclase density on each side, yielding 15 total reconstructions (Figure 4a). Comparisons of cyclase positions at each cardinal direction reveal that while cyclase positioning is moderately variable, the point of contact at the basic patch is generally though not exclusively conserved (Figure 4b). While other basic residues in this region are occasionally involved, R583, R592, and R698 consistently appear at the prenyltransferase-cyclase touchpoint regardless of how “wobbly” the cyclase is as it docks with the prenyltransferase. A workflow summarizing the method of particle subtraction, masked 3D classification, and unmasked refinement is summarized in Figure S3.

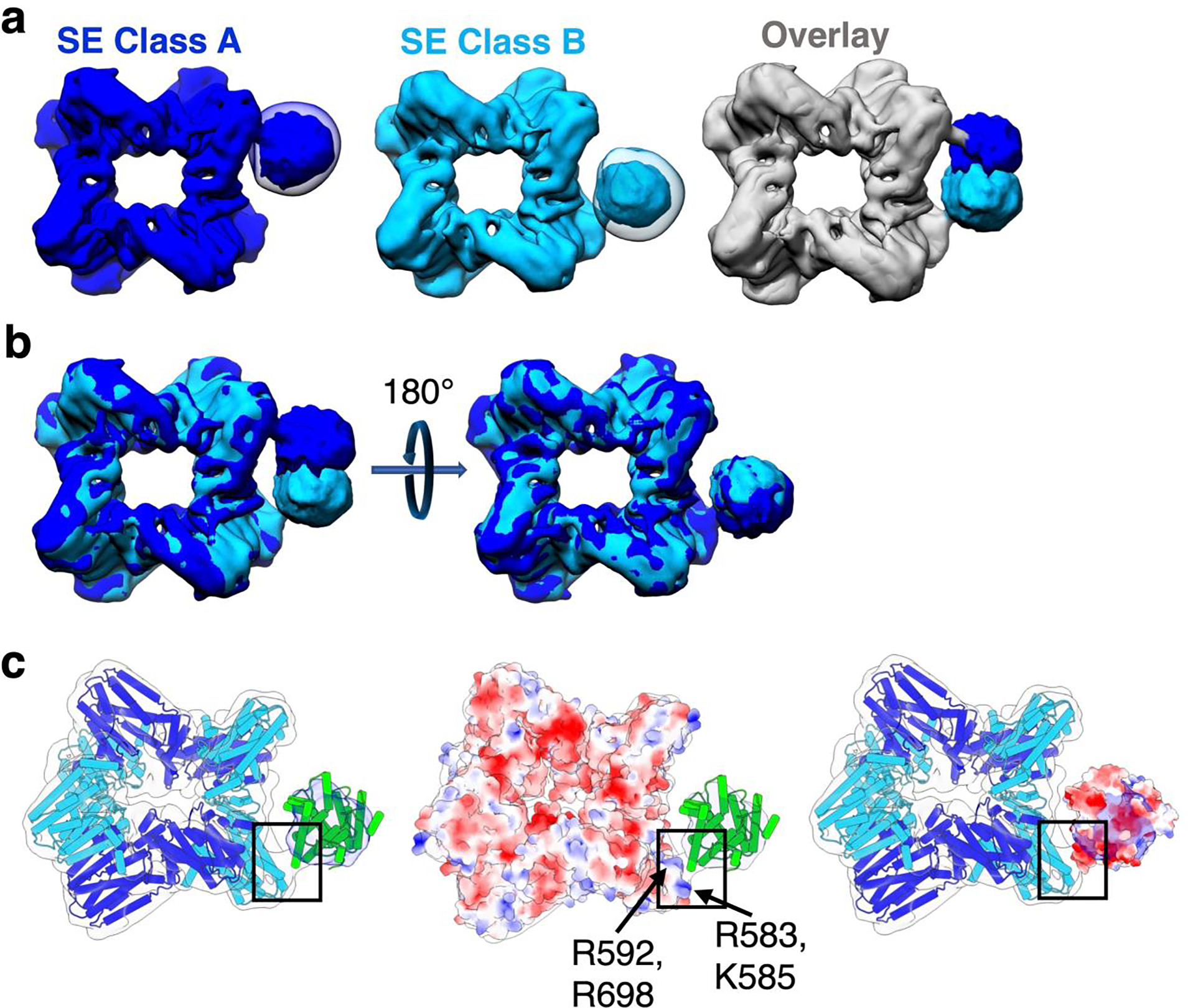

Figure 4.

Cryo-EM determinations of fifteen reconstructions of full-length PaFS with one cyclase domain. (a) Cyclase domains are associated with the east, south, west, or north sides of the prenyltransferase octamer. The octameric prenyltransferase is represented schematically with blue and cyan subunits inside the central compass rose, and randomly positioned cyclase domains are represented by green triangles around the periphery. Individual maps of full-length PaFS with one cyclase domain are listed by cardinal direction, with number of particles included in the reconstruction and map resolution indicated. For each cardinal direction, a superposition of maps is shown; for reference, prenyltransferase-cyclase contacts are highlighted in (b). Overlaid reconstructions of PaFS maps with one cyclase domain for each cardinal direction displayed in side views. Insets show putative prenyltransferase-cyclase contacts, with selected basic residues indicated. The N-termini of prenyltransferase domains are also indicated. A detailed workflow outlining the calculation of these reconstructions is shown in Figure S3.

In a minority of structures, weaker density is observed at the N-terminus of the prenyltransferase domain, which leads to the interdomain linker. Residue K419 near the prenyltransferase domain N-terminus, and also R595, may additionally contribute to prenyltransferase-cyclase contact (Figure 4b).

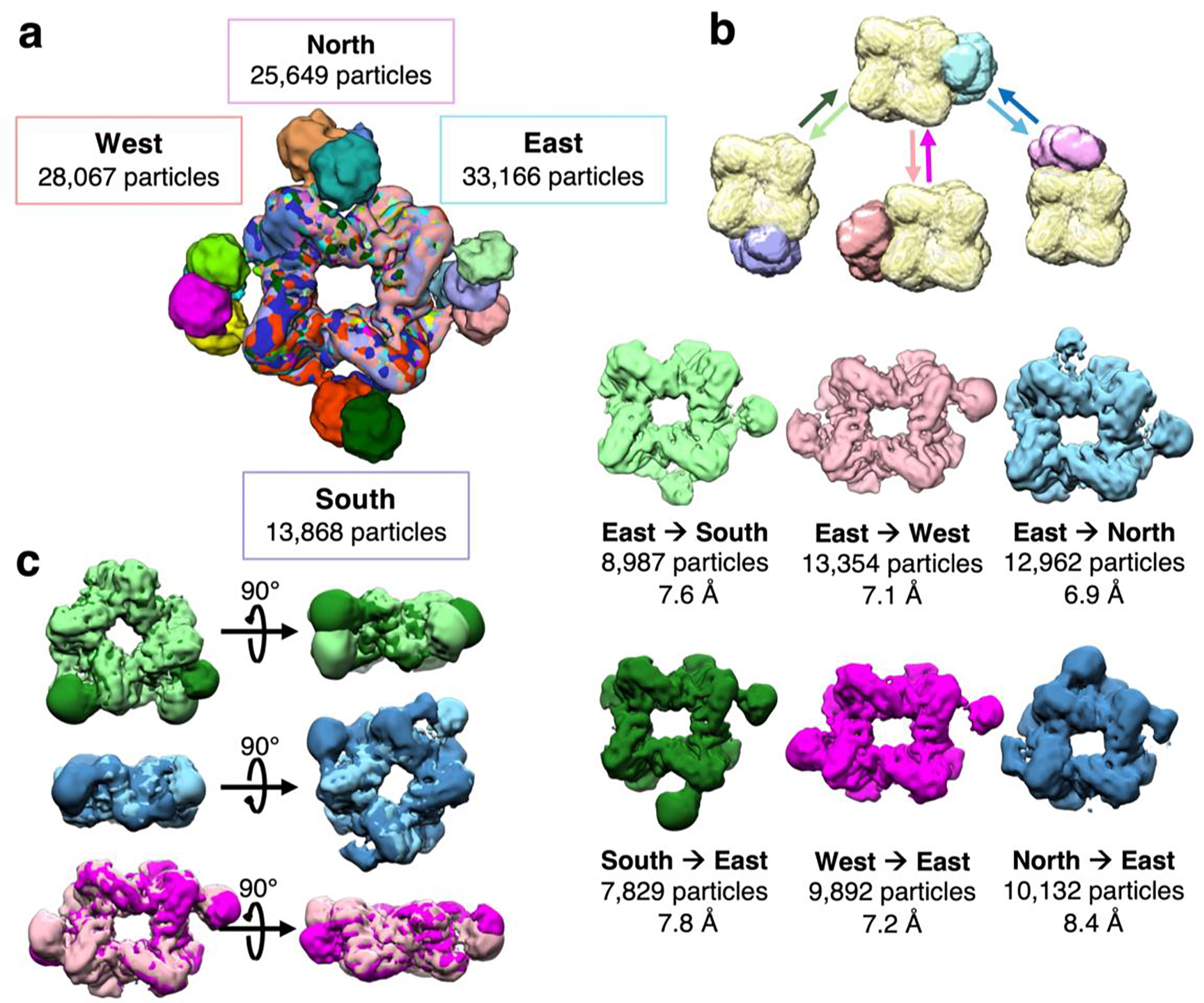

Local resolution estimations indicate that density for the prenyltransferase core generally ranges from 4–7 Å resolution, and density for the cyclase domain generally ranges from 18–22 Å resolution. At each cardinal direction, 25,649 (N), 33,166 (E), 19,678 (S), and 28,067 (W) total particles exhibit density attributable to a single cyclase domain (Figure 5a), or 25–41% of the total particles. As such, 106,560 particles were included in the 15 reconstructions containing a single cyclase domain (Figure 4a, Figure 5a). In comparison, classes of symmetry-expanded particles revealed converging density for cyclase domains in 34,614 particles. Considering that a total of 79,488 particles were used in these analyses, the observation of 106,560 cyclase domains summed here overwhelmingly indicates that two or more cyclase domains simultaneously associate with the prenyltransferase octamer.

Figure 5.

Iterative classification reveals additional proximal cyclase domains. (a) Summary of proximal cyclase domain positions docked with the prenyltransferase octamer. Maps were calculated with a single cyclase domain, and classifications were focused on a single cardinal direction; the total number of particles contributing to cyclase-docked maps at each direction are summed and listed. Subsequent data analysis utilizes the listed total number of particles. (b) Iterative rounds of masked classification and refinement yield maps with two or more cyclase domains proximal to the prenyltransferase. A schematic of this masked classification displays a mask surrounding the prenyltransferase core (yellow), used for particle subtraction, with masks encompassing a cyclase dimer docked on the north (pink), south (purple), east (blue), and west (coral) relative directions. Particles with east-proximal cyclase domains were subjected to masked classification looking for cyclases on the south, west, and north sides. Conversely, and separately, particles with south-, west-, and north-proximal cyclase domains were also subjected to masked classification focusing on cyclases on the east side. For each of these six analyses, the resulting cryo-EM map is shown and labeled, including resolution in Å and number of particles. A detailed workflow of data analysis is shown in Figure S4. (c) Superimposed reconstructions of cryo-EM maps corresponding to conversely docked cyclases. Cyclase domains generally dock at the interface of prenyltransferase dimers in the octameric assembly, although cyclase domains appear somewhat wobbly.

At lower threshold levels, these reconstructions exhibited weak but converging density at neighboring positions, suggesting that additional cyclase domains could be detected by further data analysis. Selected particles harboring a single cyclase on one side were subjected to iterative rounds of masked 3D classification targeting additional cyclase domain density on each of the remaining sides (Figure 5b). Strikingly, density for a second cyclase domain was observed in several classes (Figure 5b, Figure S4). These classes represented small subsets of 2,000–5,000 particles yielding ~22 Å-resolution molecular envelopes; combining particles from these classes yielded maps with improved resolution of the octameric prenyltransferase core with two or more interacting cyclase domains. Six different maps at resolutions ranging from 6.9–8.4 Å show a prenyltransferase octamer with two associated cyclase domains (Figure 5b). Additionally, one such map reveals significant density corresponding to a third cyclase domain (North→East map, Figure 5b). The variable positioning of proximal cyclase domains around the central prenyltransferase octamer is summarized in Figures 5a and 5c.

Solution structure of PaFS.

The variable positioning of one or more cyclase domains associated with the central prenyltransferase octamer of full-length PaFS is consistent with weak, transient interactions, suggesting that cyclase domains are in facile equilibrium between distal and proximal configurations as illustrated schematically in Figure 1. Multiple oligomerization states observed for PaFS and related enzymes contribute to an additional degree of structural variability.22,54,55 To further probe the structural variability of full-length PaFS, we employed light scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation, and small-angle X-ray scattering in studies of the enzyme in solution.

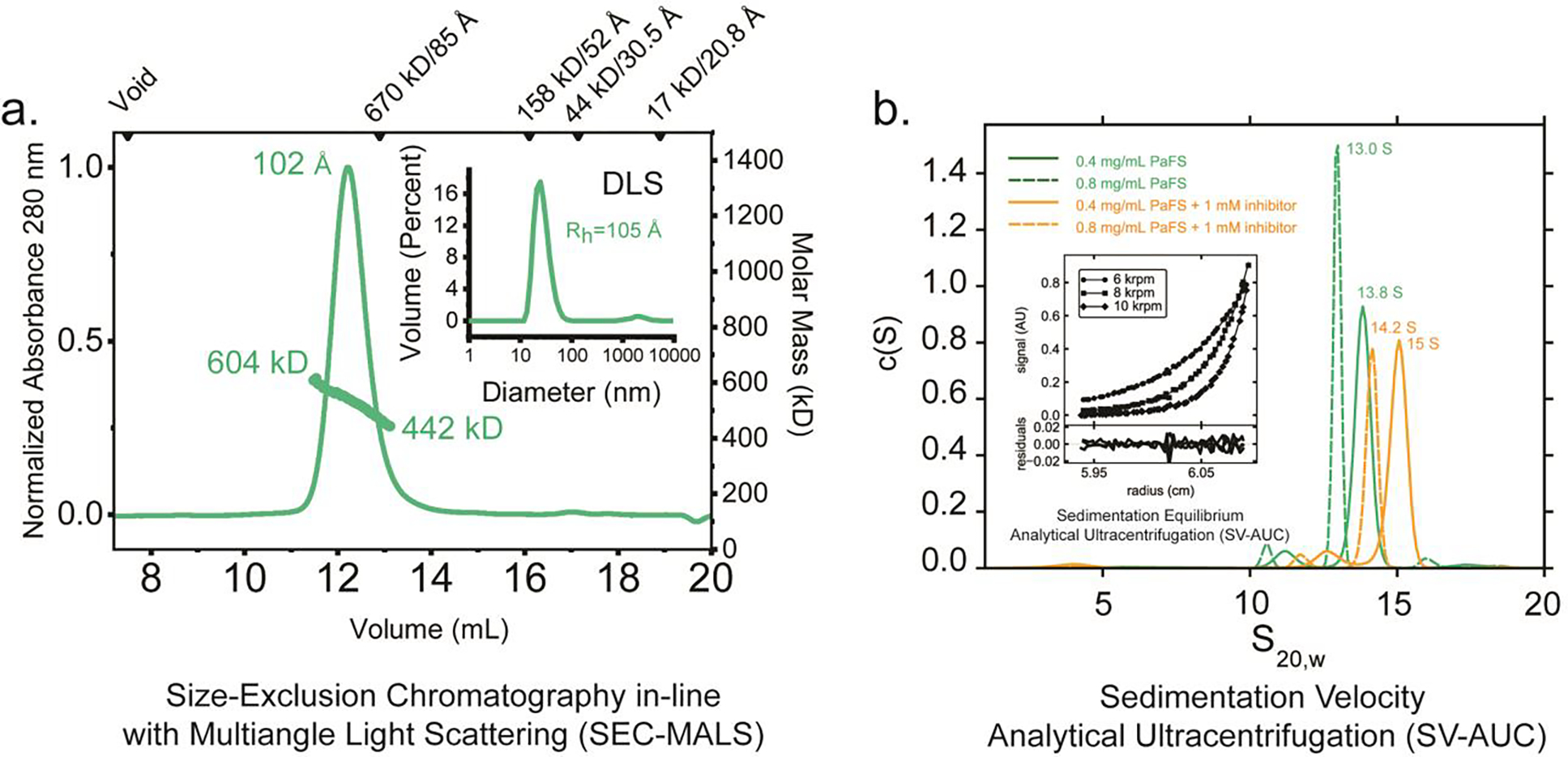

For an accurate reading of molecular weight in solution, size-exclusion chromatography in-line with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) analysis was performed at room temperature (Figure 6a). By retention time alone, PaFS has an apparent molecular weight exceeding >900 kDa relative to known globular standards. However, at a peak eluted concentration of 5.5 μM, multi-angle light scattering (a shape-independent analysis) reveals a sloping mass profile across the eluant peak ranging from ~442–604 kDa consistent with oligomers ranging from tetramers to octamers. The calculated Stokes radius (Rs) based on retention is 102 Å, consistent with the hydrodynamic radius determined by dynamic light scattering at 25 °C (Rh = 105 Å) (Figure 6a, inset). Taken together, these results indicate that at these low micromolar concentrations, PaFS exists as a mixture of oligomers that have a large spatial extent, consistent with unstructured linkers between the globular prenyltransferase and cyclase domains of each protomer.

Figure 6.

(a) SEC-MALS and DLS analysis. Shown as a green line is the absorbance profile (left axis) of PaFS at an injected concentration of 6.5 mg/mL (79 μM), as a function of retention volume in a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 column at room temperature. Green circles denote molecular masses determined by in-line light scattering (right axis). The determined molecular weight coincides with a tetramer to octamer transition across the peak area (PaFS has a theoretical mass of 81.5 kDa for the monomer). By refractive index, the concentration of the eluted material at peak was ~5 μM. Shown in inset is DLS analysis of purified PaFS, with a determined hydrodynamic radius of 105 Å. (b) Analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC). c(S) distributions were derived from the fitting of the Lamm equation to the experimental data collected for PaFS in the absence (green) and presence of pamidronate (orange), as implemented in the program SEDFIT.39 This analysis shows evidence of octameric species in solution that change in shape upon the addition of ligand. The minor species observed at 10.5–11 S are interpreted to be tetramers. Lamm equation fits to the primary data are shown in Figure S5. Shown in inset is SE-AUC analysis. Representative data at 3.7 μM monomer is shown. Global fit analysis of sedimentation equilibrium data for PaFS indicates a tetramer-octamer equilibrium in solution 4°C. Data were recorded at 6, 8, and 10 krpm each of three monomer concentrations and globally fit to derive an apparent dissociation constant. Errors for the dissociation constants reported were estimated using 1000 iterations of Monte Carlo analysis as implemented in the program SEDPHAT.40 Residuals shown reflect the discrepancy between model fits and the experimental data, with root-mean-square deviations less than 0.010.

For an independent assessment of the solution properties of PaFS, we next turned to characterization by analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC). In sedimentation equilibrium-analytical ultracentrifugation (SE-AUC) at 4 °C (also a shape-independent method), global fitting of data across three speeds and concentrations ranging from 3.8 to 8.0 μM was performed (Figure 6b, inset). Using a single species fit, a weight-average molecular weight of 560,000 ± 4,000 Da (χ2 = 0.63) was calculated, indicating the presence of species larger than tetramers and hexamers. These data are best described by a tetramer-octamer association model with Kd4–8 = 0.33 ± 0.05 μM (χ2 = 0.23), consistent with the range of molecular weights observed by SEC-MALS.

PaFS was further analyzed using sedimentation velocity-AUC (SV-AUC) at protein concentrations favoring octamerization (5 μM and 10 μM). At 5 μM, a primary 13.8 S species consistent with an octamer is observed, with a minor species apparent at 11.2 S. At 10 μM, these species shift modestly to 13.0 S and 10.5 S, respectively. The minor peaks at 10.5–11.2 S may correspond to tetramers, which have also been observed by native-PAGE.22 Equivalent samples equilibrated with MgCl2 and 1 mM pamidronate (a bisphosphonate inhibitor of both the prenyltransferase and the cyclase) similarly show measurable shifts in the c(S) distributions: at 5 μM, a primary 15 S species is observed, with a minor species apparent at 12.5 S. At 10 μM, these species shift modestly to 14.2 S and 11.7 S, respectively. Assuming constant molecular mass, these results suggest that the inhibitor elicits a modest decrease in anisotropy in PaFS in solution. Primary data and the corresponding fits with the Lamm equation are shown in Figure S5.

To inform our interpretation of the model-independent parameters determined by solution measures (e.g. Rs, S20,w), we constructed molecular models of full-length PaFS and calculated their theoretical properties using WinHYDROPRO40 (Figure S6). In one extreme, an octamer was constructed in a fully extended configuration where all cyclase domains were positioned distally. This model has a calculated S value of 7.7 and an Rs of 198 Å. In a model where all eight cyclase domains are proximally configured, an S value of 23.7 and Rs of 64 Å is calculated. Hence, assuming octamers, and based on light scattering and AUC results, it can be surmised that the solution conformations of PaFS exists in an intermediate form between these two extremes. This is consistent with our understanding of a facile equilibrium of cyclase domains positioned proximally and distally within a flexible, multidomain octamer.

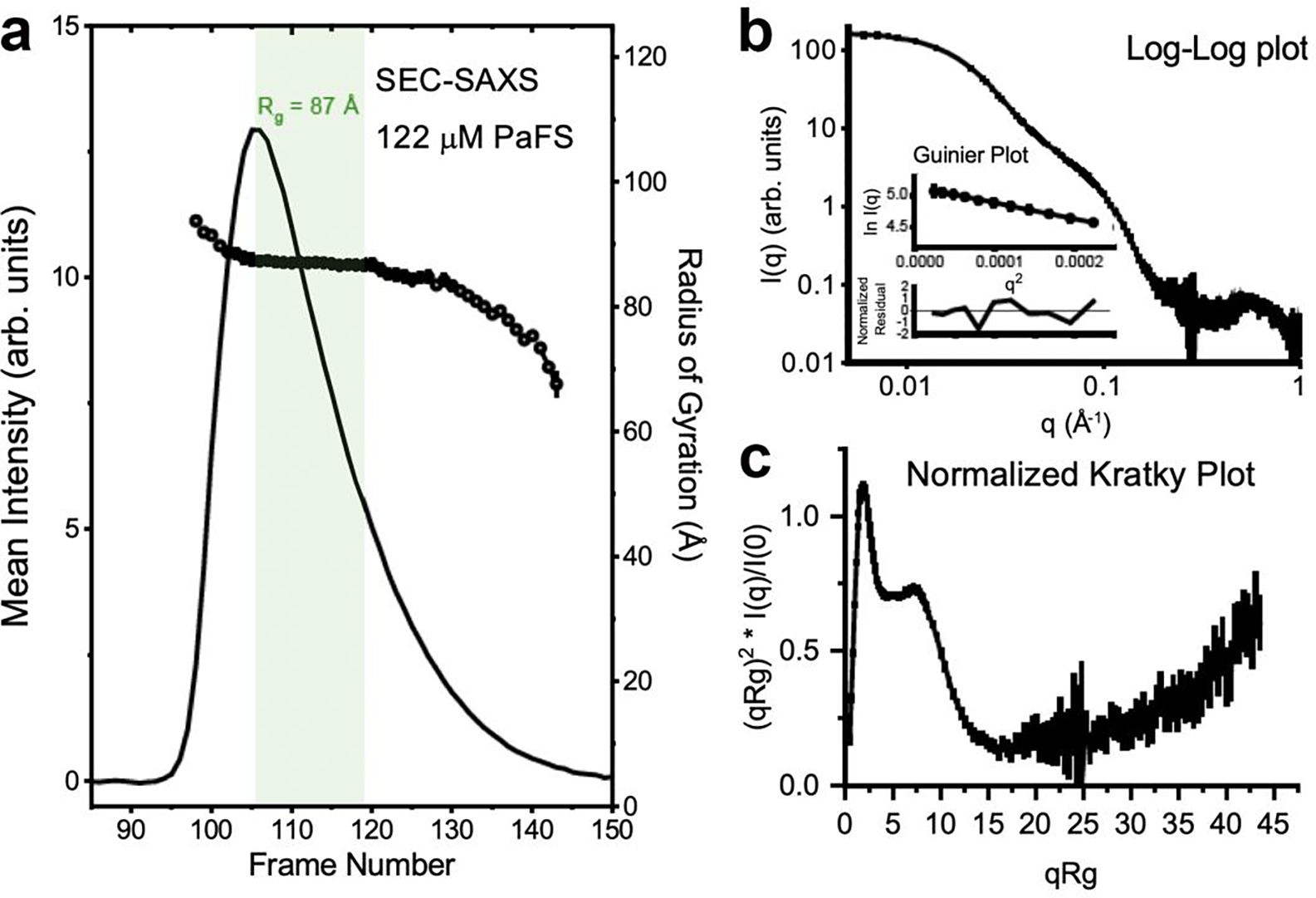

To probe the structural properties of PaFS oligomers more rigorously, we employed size-exclusion chromatography in-line with small-angle X-ray scattering (SEC-SAXS), an approach well suited to test atomistic models against solution data. The relevance of applying SEC in-line is well indicated by the appearance of reversibly-formed oligomers and the concentration-dependent behavior of this enzyme. Synchrotron SAXS data were recorded continuously during the elution of a ~122 μM bolus of PaFS from a sizing column at room temperature, providing a robust dataset of sequential scattering profiles. A single primary peak is observed in the plot of the forward scattering extrapolated to zero-angle (I(0)) versus frame number, with little variation in the radius of gyration (Rg) across the peak from half-height to half-height (Figure 7a). This region of data was analyzed in a model-free fashion using singular value decomposition with evolving factor analysis (SVD-EFA),56 allowing for the decomposition of the dataset into its minimal components with maximal redundancy. Once performed, a single species was primarily identified alongside a buffer artifact and protein aggregate. The deconvoluted profile was near-identical to the profile obtained by averaging the data obtained from half-height to half-height of the peak eluant. Masses calculated from this deconvoluted profile by two different methods (Qr and Porod analysis;48,57 see Table 1) were generally consistent with octamers of PaFS. Both Kratky plot analysis and the Porod exponent (PX) indicate particles with extensive flexibility (Figures 7b,c),58 consistent with the observations made by SEC-MALS analysis.

Figure 7. SEC-SAXS analysis.

(a) Shown as a line is the integrated intensity of recorded small-angle scattering as a function of frames recorded off a Superdex 200 10/300 column for PaFS injected at 10 mg/mL (122 μM). The intensity trace mirrors those obtained by UV and refractive index. Plotted as circles are the derived radii of gyration (Rg) for the background subtracted recorded profiles. Highlighted in green are the data that were analyzed by SVD-EFA analysis. (b) Log-log plot of the primary data decomposed from the dataset, corresponding to the PaFS octamer. Shown in inset is a classical Guinier plots analysis (ln(I) vs. q2) of SAXS data (circles), with residuals from the fit lines shown below the respective fits. Monodispersity is evidenced by linearity in the Guinier region of the scattering data and agreement of the I(0) and Rg values determined with inverse Fourier transform analysis by the programs GNOM.46 Guinier analyses were performed where qRg ≤ 1.3. Parameters derived from these analyses are recorded in Table 1. (c) Normalized Kratky Plot analysis,58 where the intensity of scattering is plotted as Iq2 versus q. I is the scattering intensity in arbitrary units and q is the scattering angle (q = 4π sin(θ)/ λ, where λ is the X-ray wavelength and 2θ is the scattering angle). Seen is a characteristic bell-shaped peak at low-q that fails to immediately return to baseline and increases at higher scattering angles, consistent with a multidomain protein with significant flexibility and disorder.

Table 1.

Properties Derived by SEC-SAXS

| Sample | Guinier | GNOM | Porod exponent,2 PX | Molecular Mass (MM), kD | Oligomer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qRg | Rg (Å) | Rg (Å) | Dmax (Å) | By Qr3 | By Vp1 | |||

| PaFS | 0.52 – 1.30 | 87.1 ± 0.4 | 89.2 ± 0.2 | 305 | 2.9 | 714 | 644 | Octamer |

Molecular Mass (MM) can be estimated using the Porod Volume, Vp, such that MM ∼ Vp/1.6. For an octamer of 81.5 kD subunits, MM = 652 kD.

Porod exponent, PX; values near ∼4 indicate compactness, whereas lower values between <2–3 indicate significant lack of compactness and increased volumes58 (These values were determined using the program ScÅtter (https://bl1231.als.lbl.gov/scatter/))).

To test atomic inventory against these SAXS data, we employed the CORAL48 program which uses coarse-grain beads for missing amino acids and regions of flexibility (residues 345–413 and terminal residues not resolved by X-ray crystallography21) in a hybrid bead-atomistic modeling approach. We performed analyses with a stochastic octamer of prenyltransferase domains, where we systematically tested models with one, two, or four cyclase domains fixed in positions suggested herein by cryo-EM density, or where all cyclase domains were allowed to move freely. In these modeling exercises, no single conformation could precisely capture all the features of the solution scattering data, entirely consistent with a model in which the protein exists in a dynamic ensemble of conformations rather than in one static conformation. Generally, models in which some of the cyclase domains were proximally fixed showed a preference over models where all eight cyclase domains were unconstrained in position (Figure 8, Figure S7). Length scales consistent with the interatomic vectors between globular domains (~65–125 Å, where 2π/q ~ length scale, in the middle q regime) are most discrepant in this analysis. While docking of increasing numbers of cyclase domains in a proximal position improves correlations near q ~ 0.06 Å−1, correlations concomitantly worsen at q ~ 0.09–0.1 Å−1. Overall, this analysis supports a model in which the PaFS octamer exists in a continuum of conformations in solution, where the cyclase domains are variably positioned in both distal and proximal configurations.

Figure 8. CORAL Analysis.

CORAL analysis48 of PaFS, which employs a rigid body approach to optimize structural models against experimental SAXS data. In this approach, missing and flexible atomic inventory (i.e., interdomain linkers) are represented as beads in coarse-grain fashion. Shown on the left is the experimental SAXS data derived from SVD-EFA analysis as grey circles in a log-log plot, where intensity (I) is plotted as a function of q. Shown as solid lines on the plot are representative fits from the derived atomistic models, including a model with no cyclase domain restraints (blue, χ2FoxS = 63.8–110.6 for ten independent calculations, Rg ranging from 88.9 to 94.3 Å), one fixed cyclase domain (red, χ2FoxS = 39.4–118.0 for ten independent calculations, Rg ranging from 85.2–92.9 Å), two fixed domains (orange, χ2CRYSOL = 36.8–96.6 for ten independent calculations, Rg ranging from 87.4–91.3 Å), and four fixed domains (green, χ2CRYSOL = 7.58–24.2 for ten independent calculations, Rg ranging from 82.8–87.0 Å). Highlighted in green and shown in inset (green box) is the middle region of the scattering profile where the greatest discrepancies between CORAL calculations and the experimental data occur, with specific length scales denoted by green arrows. While increasing the number of fixed cyclase domains improves correlations with the data where q ~ 0.06 Å−1, it also decreases correlation with the data where q ~ 0.09–0.1 Å−1. Shown on the right are the corresponding atomistic models derived from CORAL analysis with flexible atomic inventory rendered as grey spheres. Cyclase domains that were fixed in the calculation are circled.

Discussion

Assembly-line biosynthesis typically occurs in megasynthases that function in part through the formation of transient protein-protein complexes. For example, the covalently tethered acyl carrier protein of fatty acid synthases shuttles biosynthetic intermediates from one enzyme module to another through transient interactions in the multienzyme complex.59 Polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases function in a similar manner, where the acyl or peptidyl carrier protein shuttles intermediates through a precisely defined sequence of enzyme-catalyzed reactions in the megasynthase.60,61 A common feature that these assembly-line synthases share with PaFS is the formation of transient, “wobbly” protein-protein complexes. This feature makes these systems particularly well-suited for structural study using cryo-EM, which allows for the simultaneous visualization of multiple conformational states.38

Like these other assembly-line synthases, full-length PaFS consists of a combination of ordered and disordered components. At its core, PaFS is an ordered assembly of prenyltransferase domains with predominantly octameric quaternary structure. Cryo-EM grids prepared with PaFS in the absence of inhibitor reveal an octamer:hexamer ratio of approximately 10:1.22 However, the isolated prenyltransferase domain crystallizes exclusively as a hexamer.21 The results of biophysical studies are generally consistent with higher-order oligomerization (Figure 6, Figure 7, Table 1), including octamerization. Similarly, human GGPP synthase crystallizes exclusively as a hexamer,15 but hexamers and octamers are observed in solution.55 Thus, it is not unreasonable to observe oligomeric heterogeneity for PaFS insofar that its GGPP synthase domains (i.e., the prenyltransferase domains) drive oligomerization.

The structure of the prenyltransferase octamer provides a framework for understanding the association of pendant cyclase domains. That one or more cyclase domains associate with the prenyltransferase core even in the absence of covalent crosslinking confirms that our previous observation of prenyltransferase-cyclase complexation by cryo-EM and mass spectrometry was not an artifact of chemical crosslinking.22 Moreover, while we previously reported structures with only single cyclase domains associated at various positions on the prenyltransferase octamer, we now show that two and even three cyclase domains can associate simultaneously with the prenyltransferase octamer. Cyclase association most often involves a basic patch on the prenyltransferase defined by R583, R592, and R698; other basic residues in this region are also occasionally observed at the prenyltransferase-cyclase interface.

The cryo-EM studies reported herein reveal that 11% of particles revealed proximal cyclase-prenyltransferase conformations by analysis using symmetry expansion; without symmetry, 41% (E), 25% (S), 35% (W), and 32% (N) of particles were identified on each side of the prenyltransferase octamer. In addition, given the observation and classification of particles for each cardinal direction, 33–47% of particles also exhibit density for one or two additional cyclase domains. Not only does this work represent a substantial resolution improvement for associated cyclase domains in comparison with our previously reported reconstructions of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked PaFS,22 this work indicates that cyclase domains associate with the prenyltransferase octamer in the presence of Mg2+ and the bisphosphonate inhibitor pamidronate even in the absence of glutaraldehyde crosslinker. It is possible that the binding of Mg2+ and substrate GGPP similarly facilitates transient cyclase-prenyltransferase association during catalysis.

The recently reported cryo-EM structure of the bifunctional assembly-line triterpene synthase macrophomene synthase62 reveals a central hexameric prenyltransferase structure essentially identical to that of the crystal structures of human GGPP synthase15 and the PaFS prenyltransferase.21 Crosslinking with glutaraldehyde enabled the observation of density corresponding to multiple associated cyclase domains, although the density for only one cyclase domain could be reasonably fit with a molecular model due to disorder. Here, too, prenyltransferase-cyclase association appears to be slightly “wobbly”, consistent with a weak and transient interaction.

The dynamic and transient nature of prenyltransferase-cyclase association has implications for substrate channeling, here referred to as directed substrate transit, in view of the demonstration that most of the GGPP generated by PaFS remains on the enzyme for cyclization.20 The eight active sites of the prenyltransferase are accessible through the central pore of the octamer. Product GGPP diffuses out of this pore and transits to one of eight surrounding cyclase domains. The cyclase domains are themselves well-ordered but in constant motion, much like the tentacles of an octopus, due to the flexibility of the 70-residue inter-domain linker. In view of the variable positioning of cyclase domains, dynamic cluster channeling23,24 appears to be operative. That is to say, the probability that GGPP exiting from the central pore of the prenyltransferase will encounter a cyclase in motion is higher than the probability that GGPP will escape to bulk solution beyond the field of splayed-out cyclases.

Despite the randomly splayed-out positions of cyclase domains,22 it is intriguing that many enzyme particles are observed with at least one cyclase domain associated with the prenyltransferase octamer (Figure 4, Figure 5). If substrate transit occurs when the prenyltransferase and cyclase are associated, this could enable simple proximity channeling. If substrate transit occurs when the cyclase domain caps the central pore of the prenyltransferase octamer,22 the central pore itself could restrict and direct the diffusion of GGPP from the prenyltransferase to the cyclase. If substrate transit occurs when the cyclase and prenyltransferase domains transiently interact at the basic patch, the preponderance of positive charge may provide electrostatic guidance to facilitate GGPP transfer to the cyclase active site.

Finally, the first observation of multiple cyclase domains simultaneously associated with the PaFS prenyltransferase octamer provides a framework for understanding the cooperativity of GGPP cyclization as catalyzed by the full-length enzyme.21,22 The sigmoidal dependence of cyclization kinetics as a function of GGPP concentration suggests that molecular communication occurs between cyclase active sites in the full-length enzyme. Since the GGPP cyclization reaction reverts to classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics for a monomeric construct of the cyclase domain,21 the oligomeric structure of PaFS, and hence subunit-subunit communication, is presumably responsible for the observed cooperativity. This effectively rules out the special case in which a monomeric enzyme, i.e., an individual splayed-out cyclase domain, might exhibit sigmoidal reaction kinetics.63,64

Three possibilities can be envisaged for molecular communication between PaFS cyclase domains. One possibility is that splayed-out cyclase domains transiently associate in pairwise fashion. Consistent with this possibility, the cyclase domain crystallizes as a dimer even though it is a monomer in solution.21 However, we have not seen evidence for dimerization of splayed-out cyclase domains in our EM or cryo-EM studies.

A second possibility is that molecular communication between cyclase domains occurs through the flexible 70-residue linker connecting the cyclase and the prenyltransferase domains. The interdomain linker is an intrinsically disordered peptide believed to adopt a condensed, dynamic globule-like structure.65 If molecular communication between cyclase domains occurs through such a disordered linker, our notions of allostery would be challenged. Ordinarily, structural changes in multi-subunit allosteric enzymes are propagated by well-defined conformational changes of ordered helices and loop segments as one subunit communicates with another. It is difficult, though not impossible, to imagine how a molten globule-like domain could enable the propagation of such conformational changes.

A third possibility is that molecular communication occurs between two or more cyclase domains while they are transiently docked to the central prenyltransferase octamer. The cryo-EM results presented herein provide the first demonstration that multiple cyclase domains can indeed associate simultaneously with the prenyltransferase octamer. Future studies will allow us to probe these possibilities more deeply to establish the molecular basis of allostery in this unusual system.

Supplementary Material

Tables S1–S5, cryo-EM data collection and reconstruction statistics.

Figure S1, workflow for cryo-EM structure determination of the prenyltransferase core.

Figure S2, workflow for cryo-EM structure determination of the prenyltransferase core with one associated cyclase domain.

Figure S3, workflow for cryo-EM structure determinations of the prenyltransferase core with one associated cyclase domain without symmetry expansion.

Figure S4, workflow for cryo-EM structure determinations of the prenyltransferase core with multiple associated cyclase domains.

Figure S5, primary data for SV-AUC.

Figure S6, calculated hydrodynamic properties of molecular models.

Figure S7, gallery of CORAL models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are especially grateful to Theo Humphreys and Dr. Craig Yoshioka at the PNCC for their assistance and helpful scientific discussions. We thank the Biological Chemistry Resource Center in the Department of Chemistry for access to instrumentation and resources, and we thank Ryan Kubanoff for support and training. Finally, we thank Drs. Trey Ronnebaum and Hee Jong Kim for helpful scientific discussions.

Funding

We thank the NIH for grants GM56838 to D.W.C. and GM123233 to K.M. in support of this research. J.L.F. and T.v.E. were supported by the Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics NIH Training Grant T32-GM008275. A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant U24GM129547 and performed at the Pacific Northwest Center for Cryo-EM at Oregon Health & Science University and accessed through EMSL (grid.436923.9), a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Analytical ultracentrifugation analyses were performed at the Johnson Foundation Structural Biology and Biophysics Core at the Perelman School of Medicine (Philadelphia, PA) with the support of an NIH High-End Instrumentation Grant (S10-OD018483). The SEC-SAXS data were obtained at beamline 16-ID (LIX) at the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. KG acknowledges the support of the Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Accession Codes

Atomic coordinates of the 3.73 Å-resolution structure of the PaFS prenyltransferase octamer have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with accession code 8EAX; the cryo-EM map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb) with accession code EMD-27989. Additional cryo-EM maps showing cyclase domains associated with the prenyltransferase octamer have been deposited in the EMDB with accession codes as follows: SE-Class A, EMD-28076; SE-Class B, EMD-28079; SE-consensus, EMD-28046; North (A), EMD-28131; North (B), EMD-28193; North (C), EMD-28191; North (D), EMD-28132; South (A), EMD-28213; South (B), EMD-28215; South (C), EMD-28216; East (A), EMD-28202; East (B), EMD-28201; East (C), EMD-28203; East (D), EMD-28194; West (A), EMD-28219; West (B), EMD-28220; West (C), EMD-28221; West (D), EMD-28222; North & East, EMD-28240; East & North, EMD-28245; South & East, EMD-28236; East & South, EMD-28235; East & West, EMD-28237; West & East, EMD-28239.

References

- 1.Poulter CD, Rilling HC (1978) The prenyl transfer reaction. Enzymatic and mechanistic studies of the 1’-4 coupling reaction in the terpene biosynthetic pathway. Acc. Chem. Res. 11, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kellogg BA, Poulter CD (1997) Chain elongation in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christianson DW (2006) Structural biology and chemistry of the terpenoid cyclases. Chem. Rev. 106, 3412–3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y, Honzatko RB, Peters RJ (2012) Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far yet incomplete view of complex catalysis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 1153–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quin MB, Flynn CM, Schmidt-Dannert C (2014) Traversing the fungal terpenome. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1449–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christianson DW (2017) Structural and chemical biology of terpenoid cyclases. Chem. Rev. 117, 11570–11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helfrich EJN, Lin G-M, Voigt CA, Clardy J (2019) Bacterial terpene biosynthesis: challenges and opportunities for pathway engineering. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 15, 2889–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesburg CA, Zhai G, Cane DE, Christianson DW (1997) Crystal structure of pentalenene synthase: mechanistic insights on terpenoid cyclization reactions in biology. Science 277, 1820–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP (1997) Structural basis for cyclic terpene biosynthesis by tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase. Science 277, 1815–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendt KU, Poralla K, Schulz GE (1997) Structure and function of a squalene cyclase. Science 277, 1811–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Köksal M, Jin Y, Coates RM, Croteau R, Christianson DW (2011) Taxadiene synthase structure and evolution of modular architecture in terpene biosynthesis. Nature 469, 116–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldfield E, Lin F-Y (2012) Terpene biosynthesis: modularity rules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1124–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen M, Harris GG, Pemberton TA, Christianson DW (2016) Multi-domain terpenoid cyclase architecture and prospects for proximity in bifunctional catalysis. Curr. Op. Struct. Biol. 41, 27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarshis LC, Yan M, Poulter CD, Sacchettini JC (1994) Crystal structure of recombinant farnesyl diphosphate synthase at 2.6-Å resolution. Biochemistry 33, 10871–10877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanagh KL, Dunford JE, Bunkoczi G, Russell RGG, Oppermann U (2006) The crystal structure of human geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase reveals a novel hexameric arrangement and inhibitory product binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22004–22012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wendt KU, Schulz GE, Corey EJ, Liu DR (2000) Enzyme mechanisms for polycyclic triterpene formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 2812–2833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Köksal M, Hu H, Coates RM, Peters RJ, Christianson DW (2011) Structure and mechanism of the diterpene cyclase ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 431–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moosmann P, Ecker F, Leopold-Messer S, Cahn JKB, Dieterich CL, Groll M, Piel J (2020) A monodomain class II terpene cyclase assembles complex isoprenoid scaffolds. Nat. Chem. 12, 968–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toyomasu T, Tsukahara M, Kaneko A, Niida R, Mitsuhashi W, Dairi T, Kato N, Sassa T (2007) Fusicoccins are biosynthesized by an unusual chimera diterpene synthase in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3084–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pemberton TA, Chen M, Harris GG, Chou WKW, Duan L, Köksal M, Genshaft AS, Cane DE, Christianson DW (2017) Exploring the influence of domain architecture on the catalytic function of diterpene synthases. Biochemistry 56, 2010–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen M, Chou WKW, Toyomasu T, Cane DE, Christianson DW (2016) ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faylo JL, van Eeuwen T, Kim HJ Gorbea Colón JJ, Garcia BA, Murakami K, Christianson DW (2021) Structural insights on assembly-line terpene biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castellana M, Wilson MZ, Xu Y, Joshi P, Cristea IM, Rabinowitz JD, Gitai Z, Wingreen NS (2014) Enzyme clustering accelerates processing of intermediates through metabolic channeling. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1011–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweetlove LJ, Fernie AR (2018) The role of dynamic enzyme assemblies and substrate channelling in metabolic regulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schorb M, Haberbosch I, Hagen WJH, Schwab Y & Nastronarde DN (2019) Software tools for automated transmission electron microscopy. Nat. Methods, 16, 471–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng SQ, Palovcak E, Armache J, Cheng Y & Agard DA (2016) MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved single-particle electron cryo-microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohou A, Grigorieff N (2015) CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zivanov J, Nakane T, Forsberg BO, Kimanius D, Haven WJH, Lindahl E, Scheres SHW (2018) New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. eLife 7, e42166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA (2017) cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asarnow D, Palovcak E, Cheng Y (2019) UCSF pyem v0.5. Zenodo; 10.5281/zenodo.3576630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cash JN, Kearns S, Li Y, Cianfrocco MA (2020) High-resolution cryo-EM using beam-image shift at 200 keV. IUCrJ 7, 1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Punjani A, Zhang H, Fleet DJ (2020) Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanchez-Garcia R, Gomez-Blanco J, Cuervo A, Carazo J, Sorzano COS, Vargas J (2020) DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Comms. Biol. 4, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afonine PV (2018) Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Cryst. D74, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pettersen EF Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, & Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai XC, Rajendra E, Yang G, Shi Y, Scheres SH (2015) Sampling the conformational space of the catalytic subunit of human γ-secretase. eLife 4, e11182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faylo JL, Christianson DW (2021) Visualizing transiently associated catalytic domains in assembly-line biosynthesis using cryo-electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 213, 107802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuck P (2000) Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys. J. 78, 1606–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vistica J, Dam J, Balbo A, Yikilmaz E, Mariuzza RA, Rouault TA, and Schuck P (2004) Sedimentation equilibrium analysis of protein interactions with global implicit mass conservation constraints and systematic noise decomposition, Anal. Biochem. 326, 234–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL (1992) Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In: Harding S, Rowe A, Horton J, Eds. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortega A, Amoros D, de la Torre J (2011) Prediction of hydrodynamic and other solution properties of rigid proteins from atomic- and residue-level models. Biophys. J. 101, 892–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brautigam CA (2015) Calculations and publication-quality illustrations for analytical ultracentrifugation data. Methods Enzymol. 562, 109–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DiFabio J, Chodankar S, Pjerov S, Jakoncic J, Lucas M, Krywka C, Graziano V, and Yang L (2016) The Life Science X-ray Scattering Beamline at NSLS-II, Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Synchrotron Radiation Instrumentation (Sri2015), 1741. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hopkins JB, Gillilan RE, and Skou S (2017) BioXTAS RAW: improvements to a free open-source program for small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and analysis, J. Appl. Cryst. 50, 1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semenyuk AV, and Svergun DI (1991) Gnom - a Program Package for Small-Angle Scattering Data-Processing, J. Appl. Cryst. 24, 537–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, and Schulten K (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD, J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petoukhov MV, Franke D, Shkumatov AV, Tria G, Kikhney AG, Gajda M, Gorba C, Mertens HD, Konarev PV, and Svergun DI (2012) New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis, J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Svergun D, Barberato C, and Koch MHJ (1995) CRYSOL - A program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates, J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 768–773. [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLano WL (2004) Use of PYMOL as a communications tool for molecular science. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society 228, U313–U314. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleming PJ, and Fleming KG (2018) HullRad: Fast Calculations of Folded and Disordered Protein and Nucleic Acid Hydrodynamic Properties, Biophys. J. 114, 856–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garcia de la Torre J, Llorca O, Carrascosa JL, and Valpuesta JM. (2001) HYDROMIC: prediction of hydrodynamic properties of rigid macromolecular structures obtained from electron microscopy images, Eur. Biophys. J. 30, 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Couch GS, Croll TI, Morris JH, and Ferrin TE (2021) UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers, Protein Sci. 30, 70–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ronnebaum TA, Gupta K, Christianson DW (2020) Higher-order oligomerization of a chimeric αβɣ bifunctional diterpene synthase with prenyltransferase and class II cyclase activities is concentration-dependent. J. Struct. Biol. 210, 107463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuzuguchi T, Morita Y, Sagami I, Sagami H, Ogura K (1999) Human geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5888–5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meisburger SP, Taylor AB, Khan CA, Zhang S, Fitzpatrick PF, and Ando N (2016) Domain Movements upon Activation of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Characterized by Crystallography and Chromatography-Coupled Small-Angle X-ray Scattering, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6506–6516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rambo RP, and Tainer JA (2013) Accurate assessment of mass, models and resolution by small-angle scattering, Nature 496, 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rambo RP, and Tainer JA (2011) Characterizing flexible and intrinsically unstructured biological macromolecules by SAS using the Porod-Debye law, Biopolymers 95, 559–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grininger M (2014) Perspectives on the evolution assembly and conformational dynamics of fatty acid synthase type I (FAS I) systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 25, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robbins T, Liu Y-C, Cane DE, and Khosla C (2016) Structure and mechanism of assembly line polyketide synthases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 41, 10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reimer JM, Haque AS, Tarry MJ, and Schmeing TM (2018) Piecing together nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 49, 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tao H, Lauterbach L, Bian G, Chen R, Hou A, Mori T, Cheng S, Hu B, Lu L, Mu X, Li M, Adachi N, Kawasaki M, Moriya T, Senda T, Wang X, Deng Z, Abe I, Dickschat JS, Liu T (2022) Discovery of non-squalene triterpenes. Nature 606, 414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ainslie GR Jr., Shill JP, Neet KN (1972) Transients and cooperativity. J. Biol. Chem. 247, 7088–7096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Porter CM, Miller BG (2012) Cooperativity in monomeric enzymes with single ligand-binding sites. Bioorg. Chem. 43, 44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Faylo JL, Ronnebaum TA, Christianson DW (2021) Assembly-line catalysis in bifunctional terpene synthases. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 3780–3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5, cryo-EM data collection and reconstruction statistics.

Figure S1, workflow for cryo-EM structure determination of the prenyltransferase core.

Figure S2, workflow for cryo-EM structure determination of the prenyltransferase core with one associated cyclase domain.

Figure S3, workflow for cryo-EM structure determinations of the prenyltransferase core with one associated cyclase domain without symmetry expansion.

Figure S4, workflow for cryo-EM structure determinations of the prenyltransferase core with multiple associated cyclase domains.

Figure S5, primary data for SV-AUC.

Figure S6, calculated hydrodynamic properties of molecular models.

Figure S7, gallery of CORAL models.