Abstract

Mycoplasma penetrans is a recently identified mycoplasma, isolated from urine samples collected from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Its presence is significantly associated with HIV infection. The major antigen recognized during natural and experimental infections is an abundant P35 lipoprotein which, upon extraction, segregates in the Triton X-114 detergent phase and is the basis of M. penetrans-specific serological assays. We report here that the P35 antigen undergoes spontaneous and reversible phase variation at high frequency, leading to heterogeneous populations of mycoplasmas, even when derived from a clonal lineage. This variation was found to be determined at the transcription level, and although this property is not unique among the members of the class Mollicutes, the mechanism by which it occurs in M. penetrans differs from those previously described for other Mycoplasma species. Indeed, the P35 phase variation was due neither to a p35 gene rearrangement nor to point mutations within the gene itself or its promoter. The P35 phase variation in the different variants obtained was concomitant with modifications in the pattern of other expressed lipoproteins, probably due to regulated expression of selected members of a gene family which was found to potentially encode similar lipoproteins. M. penetrans variants could be selected on the basis of their lack of colony immunoreactivity with a polyclonal antiserum against a Triton X-114 extract, strongly suggesting that the mechanisms involved in altering surface antigen expression might allow evasion of the humoral immune response of the infected host.

The complete sequences of the genomes of Mycoplasma genitalium (15) and M. pneumoniae (19) are now available and confirm that mollicutes (trivial name, mycoplasmas) are the self-replicating organisms with the smallest genomes (≥580 kbp [5]). They lack the genes for numerous common biosynthetic pathways (38–40), reflecting the parasitic lifestyle of these microorganisms. This parasitism and the limited biosynthetic capacity of the mycoplasmas demand efficient membrane transporters for the acquisition of precursors for metabolism. Since mycoplasmas have no outer membrane or cell wall, such transporters are necessarily located in their single plasma membrane, and due to the many growth requirements of these microorganisms, they must be able to transport many different precursors. In addition to having this critical role in cell physiology, the mycoplasma membrane components are also directly exposed to the host immune system. Mycoplasma infections are chronic, and the microorganisms must therefore have strategies for withstanding the damage caused by this immune vigilance. A number of studies have shown that several species of mycoplasmas are able to modify their surface antigens at a high frequency. This plasticity may contribute to evasion from the host humoral immune response (for reviews, see references 10 and 55). Most of these variable surface antigens are lipoproteins, and lipoproteins are known to be immune activators, mainly through their acylated N-terminal structures (7, 34, 41). A prominent feature of many, if not all, mycoplasmas is the large number of lipoproteins in their membrane (54), which is consistent with the numerous putative lipoprotein genes identified in the genome sequences (20). Other than the few lipoproteins which have been suggested to be part of ABC transporters (11, 15, 19, 48), the physiological role of these lipoproteins remains unknown. The mycoplasmas thus must cope with the problem of having most of their cell surface covered with lipoproteins which, being highly immunogenic, are prone to antibody recognition. Being preferential targets for immune systems, mycoplasma lipoproteins are considered to be potentially important for the development of serological assays and vaccine preparations.

Mycoplasma penetrans is a newly identified species, isolated from humans, with a unique morphology characterized by an elongated flask shape. This isolate penetrates eucaryotic cells (hence its name), possesses cytopathic effects in vitro (16, 27), and kills a large proportion of chicken embryos experimentally infected via the yolk sac (18). M. penetrans was initially isolated from the urine of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected persons (28, 29), and seroepidemiological studies demonstrate that M. penetrans is associated with HIV infection, at least among the male homosexual population in France and the United States (17, 52, 53). These results, combined with the ability of some mycoplasmas to act in synergy with HIV to kill cells in vitro (24, 30), led us to propose M. penetrans as a possible HIV cofactor in viral transmission and/or disease progression (3, 4, 6). Until recently, M. penetrans had been isolated only from HIV-infected patients, and association with any pathology has not been demonstrated. However, the isolation of this mycoplasma from an HIV-seronegative person suffering from a primary antiphospholipid syndrome suggests that M. penetrans may be pathogenic, at least under certain circumstances (55a). Since isolation of M. penetrans from clinical samples is extremely painstaking (28, 29), the detection of infection by this mycoplasma relies almost exclusively on serological assays. These assays are based on an antigenic preparation consisting of a Triton X-114 (TX-114) extract of the mycoplasma (52). This extract contains two major polypeptides with apparent molecular masses of 38 kDa (P38) and 35 kDa (P35). We previously showed that P35 is the most abundant protein in the M. penetrans membrane and that both P35 and P38 are acylated (13). The gene encoding P35 was isolated and found to map upstream from a second open reading frame encoding a putative lipoprotein of 30.9 kDa showing significant similarity with P35 (13). The P35 polypeptide is the earliest and the major antigen recognized in infected patients and in experimentally infected animals (17, 35, 52).

Here we report the ability of M. penetrans to modulate its major surface antigen, P35, by phase variation. Although this property is not unique among the members of the class Mollicutes, the mechanism by which this variation occurs in M. penetrans seems to differ from those previously described in other Mycoplasma species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma strain and culture conditions.

M. penetrans GTU-54-6A1, initially isolated by S.-C. Lo (Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Bethesda, Md.), was kindly provided by J. Tully (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Frederick, Md.) and was cultured in liquid broth or on 1% Noble agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) in SP-4 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (50).

Antibodies.

Murine P35-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 7 (immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1] isotype) was established by T. Sasaki. The specificity of MAb 7 for P35 was established in another study (35). A rabbit hyperimmune serum (polyclonal antibody [PAb] 2) was raised against a whole M. penetrans TX-114 extract and reacts predominantly with the P30, P35, and P38 polypeptides (35). For use in colony immunoblotting, the serum was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA); for use in Western immunoblotting, it was diluted in the same buffer containing 0.1% Tween 20.

Transmission electron microscopy.

To locate the P35 polypeptide at the mycoplasma cell surface, we used an immunogold labeling technique whereby whole cells were labeled with anti-P35 MAb 7 at 0.03 mg/ml, essentially as described by Le Gall et al. (22). Briefly, the M. penetrans cells were washed once in PBS and resuspended in PBS. Nickel grids previously coated with a Formvar carbon film were laid on the mycoplasma suspension for 3 min. The cells were fixed for 20 min at room temperature with PBS–2% paraformaldehyde–0.1% glutaraldehyde. The grids were laid onto PBS–10 mM NH4Cl for 10 min, then on PBS–1% BSA for 10 min, and then on a PBS–0.5% BSA–0.1% gelatin solution containing 10 μg of MAb 7 per ml for 1 h at room temperature. After five washes in PBS–0.5% BSA–0.1% gelatin, the grids were incubated on a 1:25 dilution of the gold-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse IgG and IgM antibodies conjugated to 10-nm-diameter gold particles from Amersham International plc., Amersham, United Kingdom) in PBS–0.5% BSA–0.1% gelatin. The grids were washed, negatively stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid, and examined with a JEOL EX 1200 electron microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

Mycoplasma protein analysis.

TX-114 phase partitioning of cellular antigens from M. penetrans variants was performed as previously described (13). Cell lysates or TX-114-extracted proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as described by Laemmli (21). The separated proteins were stained with Coomassie blue or electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. Western blotting was done as previously described (13), using MAb 7 (diluted 1:1,000) or PAb 2 (diluted 1:500) as the primary antibody and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Colony immunoblotting and designation of M. penetrans clonal lineages.

P35 was detected in M. penetrans clonal lineages by colony immunoblotting as described by Rosengarten et al. (42) with the various sera described above. Briefly, nitrocellulose filters were placed, under sterile conditions, on top of colonies for 5 min, gently removed, and incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody (MAb or PAb) diluted in PBS–3% BSA. After being washed with PBS, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1/3,000 dilution in PBS–1% BSA). The membranes were again washed in PBS, and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate was used with nitroblue tetrazolium for the colorimetric detection of alkaline phosphatase activity.

The P35− variants, selected on the basis of results of colony immunoblotting with MAb 7 or the PAb, were designated M (monoclonal) or P (polyclonal); the number following this letter indicates a particular clone. The revertants (P35+) obtained from P35− clonal lineages were designated R (revertant). For example, the first revertant obtained from the lineage M6 was designated RM61.

Genomic DNA isolation, Southern blotting, PCR, and DNA sequencing.

M. penetrans genomic DNA was purified by conventional procedures (33) and digested with restriction enzymes as recommended by the suppliers (Boehringer Mannheim France SA, Meylan, France; New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Following agarose gel electrophoresis, Southern blot hybridization was performed on Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham International). Membranes were prehybridized in a buffer containing 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 15 mM sodium citrate), 5× Denhardt’s solution, 0.1% SDS, and 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per ml. The DNA probes were labeled by nick translation and were added to the hybridization solution. The membrane was incubated at 65°C for 16 h with the probes and then washed twice for 20 min at room temperature with 6× SSC–0.1% SDS and once for 30 min at 65°C with 0.2× SSC–0.1% SDS. Blots were exposed to BioMax films (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

To evaluate the sequence diversity of the p35 gene and its promoter in the different variants, the corresponding regions were first PCR amplified from isolated genomic DNA. Two sets of primers were used for PCR amplification: P35/1 (5′-CAAAGAATTATTTCTAAAAAATAGAAACTAAATGCAAAT-3′, beginning at nucleotide [nt] 3 in IMP11) plus P35/17 (5′-CCGGAGCTTTTGGAATTG-3′, beginning at nt 1679 in IMP11), and P38/4 (5′-AAATTGCTGCTGC-3′, beginning at nt 905 in IMP14) plus P35/18 (5′-GGTAACAAGAATTAACTC-3′, beginning at nt 140 in IMP11). Plasmid pMP11 was previously obtained by ligating a 2.9-kbp HpaI DNA fragment from the M. penetrans genome into the single SmaI site of pUC18 (13). The insert in pMP11 encompassing the p35 gene was designated IMP11 and was entirely sequenced (GenBank accession no.: L38250 [13]). To minimize misincorporation of nucleotides, Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used for PCR. The thermal cycling included DNA denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 10 min, with a final extension of the products at 72°C for 10 min. After purification by ultrafiltration using Microcon 100 microconcentrators (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.), the amplicons were sequenced, without subcloning, by fluorescent dideoxynucleotide-based chemistry (Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and electrophoresis with an automated DNA sequencer (model 373A; Applied Biosystems). Individual sequence segments were assembled by using AssemblyLine software (Eastman Kodak). The entire sequences of both strands of DNA were determined at least once.

To evaluate the size of the p35 gene and its promoter in the different variants, two sets of PCR primers were used: P35/6 (5′-TCTACTTATTAATTTTCGTAGC-3′, beginning at nt 160 in IMP11) plus P35/7 (5′ GCAACTTTAGCTAAAAAGTTG 3′, beginning at nt 1318 in IMP11), and P35/1 (5′-CAAAGAATTATTTCTAAAAAATAGAAACTAAATGCAAAT-3′, beginning at nt 3 in IMP11) plus P35/2 (5′-GGCACAGACAGAGAAACAACT-3′, beginning at nt 484 in IMP11). The PCR conditions were as described above.

PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing of p35-like genes from the M. penetrans genome.

p35-like genes were amplified from the M. penetrans genome by using as the forward primer P38/1 (5′-AATTATTGAAAGCTCTTGC-3′, beginning at nt 266 in IMP11), which corresponds to the region of the identical sequences in p35 and p30 genes and which encodes part of the P30 and P35 signal sequences (13). The reverse primer was P38/2 (5′-CGAAAATTAATAAGTAGAGGTAACAAGAATTAACTCTA-3′, beginning at nt 140 in IMP11), and the PCR conditions were as described above. The amplicons obtained were ligated into pCRII by T/A overhang (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). The nucleotide sequences of the resulting constructs were determined as described above. Nucleotide and polypeptide sequences were aligned by using Clustal W software (49). Databases were searched for polypeptides similar to mpl (M. penetrans lipoprotein)-encoded polypeptides by using Fasta software (version 3.06) included in the Wisconsin Package (version 9.1; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.).

RNA isolation, primer extension assay, and RNA slot blot analysis.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from mid-logarithmic-phase cultures of M. penetrans by the procedure of Chomczynski and Sacchi (8), using the Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL, Frederick, Md.). The total RNAs were resuspended in distilled water containing 0.05 U of RNase inhibitor (RNAguard; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) per μg of RNA. The concentration of each preparation was determined at 260 nm.

Standard procedures were used for the primer extension assays (45) with 3 μg of purified total RNA and the primer P35/4 (5′-GGGAATGGTGGAACAGATGG-3′, beginning at nt 376 in IMP11). A dideoxy sequencing reaction with pMP11 was initiated with the primer P35/4 and modified T7 DNA polymerase (Sequenase; U.S. Biochemical Corp., Cleveland, Ohio), and the reaction product was loaded on the same sequencing gel as the primer extension reaction.

For the RNA slot blot analysis, total cellular RNAs from M. penetrans variants were treated with RNase-free DNase (10 U/100 μg of RNA) for 1 h at 37°C. Equal amounts of RNA (1 μg) were diluted in a RNase-free solution containing formamide (50%), formaldehyde (17%), and MOPS (3-N-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) buffer, heated at 60°C for 15 min, and collected in duplicate on a GeneScreen Plus membrane (NEN, Boston, Mass.) by vacuum (Minifold II; Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Oligonucleotides probes were labeled with [γ-32P]dATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The probes for the detection of p35, p30, and IMP12-1 expression were OP35 (5′-CCCTTAATTGCAGCAGAATCACC-3′), OP30 (5′-CACCTCCAGTAAACCCTAA-3′), and OMP12-1 (5′-GCACTTCAACTCTTATTTGGATC-3′). The probe ATP/10 (5′-GTTCTTTCACCAACWCCAGCA-3′) was designed from a phylogenetically conserved region of the atpD gene and used as a control. The atpD gene encodes the ATP synthase F1 β subunit, and the ATP/10 primer was determined by alignment of the atpD genes from M. pneumoniae, M. genitalium, and M. capricolum from a phylogenetically conserved region of the gene encoding the β subunit of the ATP synthase F1. The specificities of the oligonucleotide probes OP35, OP30, OMP12-1 and ATP/10 were verified by Southern blot experiments (data not shown). The patterns obtained were consistent with the known restriction maps (OP35, OP30, and OMP12-1) or with the presence of a single gene in the genome (ATP/10).

Blots were hybridized at 37°C for 16 h in a buffer obtained by dissolving a hybridization buffer tablet (Amersham International) in 10 ml of distilled water as recommended by the manufacturer. After incubation, the membrane was washed at room temperature for 10 min with 2× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.15 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4H2O, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]), 10 min with 2× SSPE–2% SDS, and 10 min with 0.1× SSPE. Blots were exposed to BioMax films (Eastman Kodak).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank/EMBL accession numbers for DNA sequences of IMP12, IMP13, and IMP14 are AJ006697, AJ006698, and AJ006699, respectively.

RESULTS

The M. penetrans P35 antigen undergoes high-frequency phase variations.

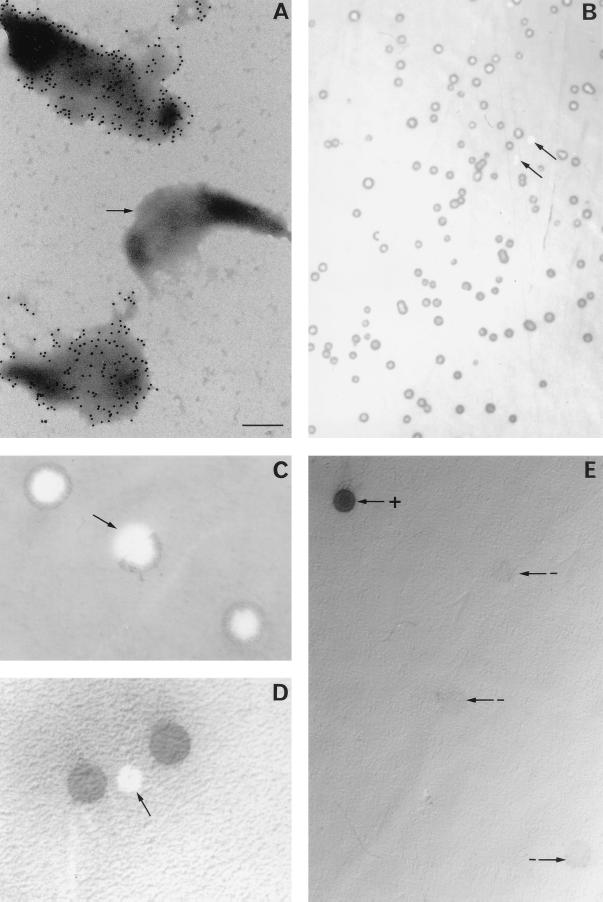

By immunoelectron microscopy, P35 is exclusively detected on the mycoplasma cell surface, including on the tip structure (Fig. 1A), which is believed to mediate cytoadherence (16, 27). However, analysis of several electron microscope fields indicated that a small proportion (about 1.5%) of the cells were not labeled with MAb 7 (Fig. 1A). Thus, in a given lineage, not all of the mycoplasma cells appear to express P35-specific immunoreactivity on the surface. This phenomenon was further evaluated by colony immunoblotting (Fig. 1B to D); using reactivity to MAb 7 as a marker for P35 expression, a small percentage of the colonies were found to be P35− (Fig. 1B). A clonal lineage, selected for its P35+ phenotype, was found to switch to the P35− phenotype with a calculated frequency of about 2 × 10−3 per cell per generation. Numerous M. penetrans colonies exhibited a mixed phenotype, with only some sectors recognized by MAb 7 (Fig. 1C), consistent with a similarly high switching frequency of expression during colony growth. The heterogeneity of colonies for surface antigen expression was also evaluated by using antibodies exhibiting a broader specificity. M. penetrans colonies were immunolabeled with a rabbit antiserum raised against the whole M. penetrans TX-114 antigen extract (PAb 2). Some of the colonies were still found not to immunoreact (Fig. 1D). The frequencies of P35− colonies and of colonies showing a mixed phenotype were about 4 × 10−3 and 1.5 × 10−2 per cell per generation, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Immunodetection of P35 expression at the M. penetrans cell surface or on mycoplasma colonies. (A) Individual M. penetrans cells were examined by immunoelectron microscopy for P35 expression with MAb 7 and after negative staining. The bar represents 200 nm, and the arrow indicates a cell which did not react with MAb 7. (B to E) Replica blots of M. penetrans colonies tested for P35 expression by specific immunolabeling with MAb 7 (B, C, and E) or with PAb 2 (D). The arrows indicate whole colonies (B and D) or colony sectors (C) which were not immunostained. The arrows labeled + and − indicate colonies exhibiting P35+ and P35− phenotypes, respectively.

M. penetrans variants nonreactive with MAb 7 (P35− phenotype) were isolated and subcultured. Most of the colonies from these variants were P35−, but a few bound MAb 7 (Fig. 1E), indicating a reversion to the original P35+ phenotype and demonstrating the reversibility of the P35+↔P35− phenotype switching.

Various clonal variants were chosen for further analysis: P35− variants selected with either MAb 7 (M4 and M6) or PAb 2 (P1, P2, and P4) and the corresponding P35+ revertants (RM41 derived from M4; RM61 and RM62 derived from M6). The phenotypic stability of each clonal lineage (P35+ or P35−) was tested. After three in vitro passages, the relative proportions of the P35− and P35+ colonies were unchanged, indicating that under these in vitro conditions, the phenotype was stable (data not shown).

Analysis of the protein content of the different M. penetrans clonal variants.

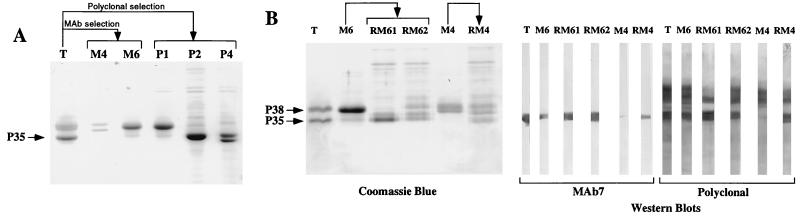

To evaluate if the variable P35 expression at the mycoplasma cell surface was due to a true P35 phase variation (on↔off), or to switching between masked and unmasked P35, TX-114 extracts from selected clonal variants (M4, M6, P1, P2, and P4) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). We confirmed our previous finding (13) that P35 is the main antigen in the M. penetrans TX-114 extract (Fig. 2). The protein profiles from the selected clonal variants differed from that of the type strain. No P35 was detected in the M4 extract. The M6 and P1 extract profiles, although differing from that of M4, were similar to each other: the major band was an antigen with an apparent molecular mass of 38 kDa, and there was only a faint band at the P35 position. Finally, two other profiles were obtained with the two other clonal variants (P2 and P4). Although P2 and P4 were obtained from colonies which did not react with PAb 2, examination of the protein profile (Fig. 2A) and Western blot analysis (data not shown) indicated that P35 was still produced in these variants.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the protein content of M. penetrans clonal variants. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of TX-114 phase-fractionated proteins from the M. penetrans type strain (T) and derived variants (M4, M6, P1, P2, and P4). These variants were selected from the type strain on the basis of colony immunoblotting with MAb 7 or with PAb 2, as indicated. After electrophoresis, the proteins were stained with Coomassie blue. The position of P35 is indicated by an arrow. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of TX-114 phase-fractionated proteins from the M. penetrans type strain (T), two variants (M4 and M6), and their corresponding revertants (RM4, RM61, and RM62). The revertants were obtained from the variants on the basis of their P35 phenotype established by colony immunoblotting with MAb 7. Similar amounts of protein were loaded in all lanes of the gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were stained with Coomassie blue or by immunoblotting with MAb 7 or the polyclonal antiserum, as indicated. The positions of P35 and P38 are indicated.

The protein profiles of the M4 and M6 TX-114 extracts were found to differ from those of their corresponding revertants (RM4, RM61, and RM62) (Fig. 2B). This observation was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). Whereas MAb 7 revealed only a faint band in the M4 protein profile, most probably resulting from the low percentage of P35− revertants in this clonal lineage (Fig. 2B), the corresponding RM4 revertant exhibited an intense P35 band. A similar result was obtained with a whole-cell lysate used in place of the TX-114 extract for this variant (data not shown). For the other variant (M6), there was a MAb-reacting polypeptide, although the intensity of the signal was lower than those obtained with either the type strain or its revertants RM61 and RM62. The higher immunoreactivity of P35 in M6 extracts than in M4 extracts (Fig. 2B) may be correlated with the difference in the frequency of reversion in a culture. Indeed, immunoelectron microscopy observation of the MAb 7 reactivity of cells from M4 and M6 cultures indicated proportions of revertants of 1 and 12%, respectively (data not shown). Western blotting with PAb 2 confirmed the lack of P35 in M4 and indicated that other antigens in the TX-114 extract were nevertheless recognized by antibodies in this antiserum (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that P35 expression undergoes phase variation.

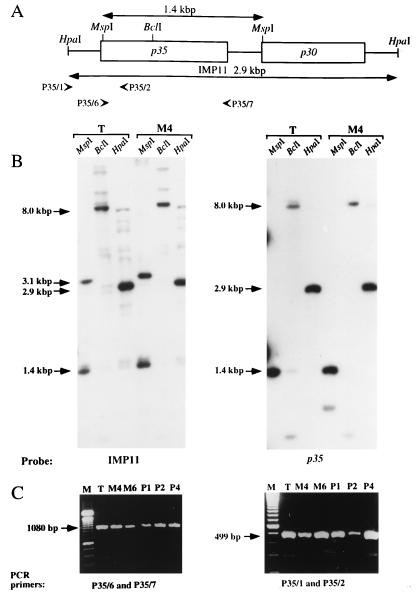

P35 phase variation is not associated with chromosomal rearrangement.

To determine whether large-scale DNA rearrangements were associated with P35 phase variation, restriction digests of the genomic DNA preparations from P35+ and P35− clonal populations were compared (Fig. 3). Three endonucleases were chosen for their different restriction sites in the HpaI 2.9-kbp fragment, encompassing the p35 gene: BclI has a single site within the p35 gene, MspI releases a DNA fragment overlapping most of this gene, and HpaI was used to clone the fragment. Genomic Southern blotting was performed either with the entire pMP11 or with the isolated p35 gene without its 5′-signal sequence-encoding fragment as the probe (Fig. 3B). There were no detectable differences in the restriction patterns obtained with the genomic DNAs from the type strain and the variant M4. Thus, large-scale DNA rearrangements (transposition, inversion, or duplication) of the p35 gene do not appear to be associated with P35 phase variation. In addition, the obtained profiles strongly suggested that there is only a single copy of the p35 gene in the M. penetrans genome.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of genomic DNA from the M. penetrans type strain and derived variants. (A) Restriction map of pMP11, including the P35-encoding region. The positions of restriction sites of the three enzymes used in the Southern blot analysis are indicated. Positions of the PCR primers used for the analysis of two regions are shown below the map by arrowheads. (B) Southern blot analysis of DNA from the type strain (T) and the P35− variant (M4). As indicated, two probes were used: pMP11 (left) and the isolated p35 gene without its sequence signal encoding fragment (right). The positions and sizes of the major hybridizing DNA fragments are indicated. (C) Comparison of the sizes of fragments amplified by PCR from two genomic DNA of the type strain (T) and from five P35− variants (M4, M6, P1, P2, and P4). A DNA fragment encompassing the p35 gene (size of the amplicon, 1,080 bp) was PCR amplified with the PCR primers P35/6 and P35/7, and another upstream from this gene (size of the amplicon, 499 bp) was amplified with PCR primers P35/1 and P35/2. In both ethidium bromide stained-agarose gels, the DNA marker (M) was a 100-bp DNA ladder.

To confirm the Southern blotting results, the lengths of two regions were determined by PCR: the p35 gene by using primers P35/6 and P35/7, and the region located immediately upstream from this gene by using primers P35/1 and P35/2 (Fig. 3A). These primers sets allowed the amplification of a 1,080-bp DNA fragment (with primers P35/6 and P35/7) and of a 499-bp DNA fragment (with primers P35/1 and P35/2) (Fig. 3C). The sizes of the fragments amplified from the type strain were the same as the sizes of those amplified from the selected variants (M4, M6, P1, P2, and P4).

P35 phase variation is not associated with mutations within the p35 promoter or within the p35 gene itself.

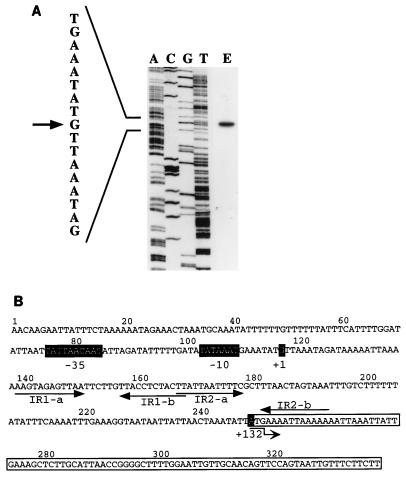

Although the p35 gene was previously identified (13), the transcription initiation site remained to be determined. It was identified by a primer extension assay (Fig. 4A), 132 bp upstream from the proposed translation initiation site. Potential −10 and −35 boxes were deduced (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, two direct repeat sequences were found within this promoter region.

FIG. 4.

Identification of the transcription start site of the p35 gene and analysis of the deduced promoter region. (A) Autoradiogram of a polyacrylamide gel used to analyze the size of the DNA obtained by reverse transcription. Because the radioactive signals obtained with the sequencing ladder and the primer extension did not have similar intensities, the figure is a composite of two exposure times. The position of transcription start site of the p35 gene is shown by an arrow. E designates the results from primer extension. (B) Deduced promoter region for the p35 gene. Numbers above the sequence correspond to the nucleotide numbering in IMP11. The transcription start site and the −35 and −10 boxes are in black boxes. The P35-encoding region is boxed, and the first nucleotide is in a black box with a number indicating its position with reference to the transcription start site. Two inverted repeated sequences are underlined with arrows.

To identify any point mutations either within this promoter region or within the p35 gene, the sequence from nt 1 to 1840 in IMP11 was PCR amplified from the type strain and from the variant M4 and determined in its entirety. There was perfect identity between the determined sequences, which clearly indicated that there was no point mutation associated with P35 phase variation in M4. The absence of point mutations was also confirmed for other variants (P1, P2, P4, and M6) by sequencing the region from nt 20 to 500 in IMP11.

The p35 gene belongs to a family of related lipoprotein genes.

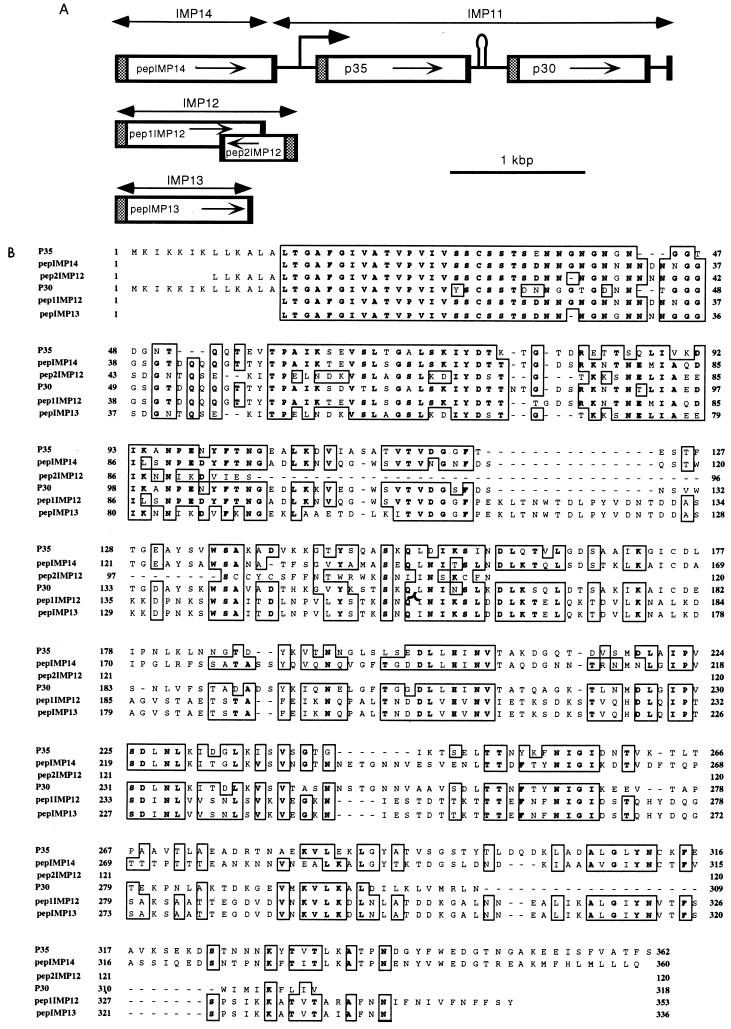

The organization of the p30 and p35 genes within IMP11 suggested that they might belong to a family of related genes encoding lipoproteins (13). In particular, there was a striking identity of the 5′ ends of these two genes, which we used to develop a strategy to amplify a putative lipoprotein gene located upstream from IMP11 on the M. penetrans genome. A forward primer (P38/1) was derived from the conserved region of the p30 and p35 genes, and the reverse primer (P38/2) corresponded to a sequence located upstream from the p35 gene promoter. Using this strategy, we obtained several amplicons, and three were sequenced. All carried potential lipoprotein genes. The sequence from one of the selected plasmids (pMP14), as hypothesized, overlapped the 5′ end of IMP11 and was found to encompass part of the gene encoding a putative lipoprotein with a deduced molecular mass of 36 kDa for its mature product (pepIMP14 [Fig. 5]). Putative lipoprotein genes were also found on two other plasmids obtained (pMP12 and pMP13). The genomic positions of the regions inserted in pMP12 and pMP13 are not known. Sequence analysis indicated that they were both PCR amplified from the single P38/1 primer. In agreement with this finding, two divergent and partially overlapping open reading frames, encoding putative lipoproteins, were found to reside on the pMP12 insert (Fig. 5). These related (some being putative) genes, designated mpl genes, share perfect identity in the region corresponding to a lipoprotein signal sequence. The different polypeptides deduced from the mpl genes share a certain degree of similarity. Multiple alignments clearly indicate almost perfect identity of their N termini, including their signal sequences (Fig. 5). With the notable exception of pep1IMP12 and pepIMP13, which share a high degree of identity, more diversity in the primary structures of these polypeptides was found in regions closer to their C termini. The sizes of the deduced mature polypeptides are between 10.6 kDa (pep2IMP12) and 36.8 kDa (pepIMP14); it should also be noted that the size of pepIMP13 is not known because its gene on IMP13 is truncated. We also cannot exclude the possibility that other genes in the M. penetrans genome encode related Mpls. Finally, the search for similarity with the mpl-encoded polypeptides in databases did not reveal any high score of identity.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of members of the mpl gene family. (A) Genetic organization of mpl genes. The isolation and sequencing of IMP11 have previously been reported (13). In this study, the sequence upstream from IMP11 was determined (IMP14). Two other independent M. penetrans DNA regions (IMP12 and IMP13) whose genomic location relative to IMP11 is unknown were PCR amplified, isolated, and sequenced. The shaded boxes indicate identical regions encoding putative signal sequences. (B) Multiple alignment of P35-related polypeptides, obtained by using Clustal W software. The boxed amino acids are common to at least four of the six sequences. Boxes indicate identical residues (bold letters) or conservative changes.

P35 phase variation is conditioned by transcription of the p35 gene.

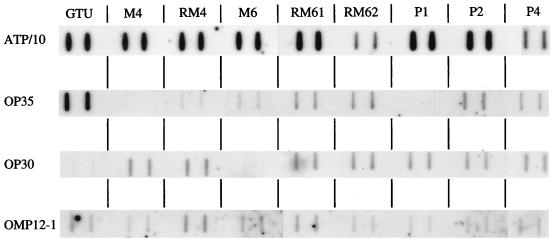

To determine whether the P35 phase variation was associated with corresponding modifications in the production (or stability) of its mRNA, RNA blotting experiments were performed. To compare lipoprotein gene expression, 1 μg of total RNA from each M. penetrans variants was blotted on the membrane. In addition, to control for total mRNA amounts, an mRNA for a gene conserved among mollicutes was also specifically detected. The selected gene, atpD, which encodes the β subunit of the ATP synthase F1, was chosen because its expression was presumed to be the same in the different M. penetrans variants. The intensities of the hybridization signal with the atpD-specific probe were similar for the variants, except for RM61 and P4, for which the amount of detected atpD transcript was lower (Fig. 6). Taking this variation into account, we found that the p35 gene was expressed to a high level in strain GTU and to a lower level in the RM4, RM61, RM62, P2, and P4 variants. p35 gene expression was lowest in the M4, M6, and P1 variants, in accordance with the low amount of P35 detected in these variants by Western blotting. Thus, P35 phase variation is determined by variations of the level of p35 transcription.

FIG. 6.

RNA slot blot analysis of p35, p30, IMP12-1, and atpD gene transcription in different variants of M. penetrans. RNA samples (1 μg) from M. penetrans GTU and variants M4, RM4, M6, RM61, RM62, P1, P2, and P4 were blotted in duplicate. The blots were hybridized with the oligonucleotide probes indicated on the left.

The expression of two other lipoprotein genes (p30 [encoding P30] and IMP12-1 [encoding pep1IMP12]) was also studied in the same experiment. Interestingly, p30 gene expression was found particularly low in GTU and M6. The expression of IMP12-1 was more similar among the different variants (Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that P35, the M. penetrans major surface antigen, undergoes high-frequency phase variation at a rate similar to that described for other mycoplasma variable lipoproteins (for a review, see reference 10). Sequence analysis of the gene encoding P35 and flanking sequences reveals that this gene is located upstream from a second open reading frame (ORF2) encoding a putative lipoprotein of 30.9 kDa (P30) with significant similarity with P35 (13). In addition, we have identified other related genes, designated mpl genes, which potentially encode lipoproteins. A remarkable feature of the deduced lipoproteins is that they all have identical signal sequences. Although the mature moieties of these polypeptides differ, they are nevertheless homologous. At least three of these genes (the gene encoding pepIMP14, p35, and p30) are clustered in the M. penetrans genome. A similar organization of genes encoding variable lipoproteins has been previously described for M. bovis (1, 31), M. hyorhinis (43, 56), M. fermentans (47, 48), M. gallisepticum (32), and M. pulmonis (2, 46). Analysis of the protein patterns obtained with the TX-114 extract from the different M. penetrans variants clearly indicated that the P35 phase variation was associated with modifications of the expression of the other lipoproteins; this was also partially confirmed by the results of RNA slot blotting. However, the amount of p30 mRNA in the different variants could not be correlated with that of p35 transcript, suggesting that the expression of these two genes is not coordinated. The heterogeneity in the protein patterns among the M. penetrans variants was remarkable and highlighted the multiple possible combinations in the repertoire of lipoproteins expressed at a given time.

The role of P35 in M. penetrans physiology is not known. It is striking that such an abundant protein is nonessential: under the electron microscope, the different variants exhibited similar morphologies and the capsule layer identified recently by us was not affected by the absence of P35 expression (data not shown). In addition, the rates of in vitro growth of the variants were similar. Since two-component sensory elements have not been found in the genomes of M. pneumoniae and M. genitalium (20), it is possible that some of the mycoplasma lipoproteins act as sensory elements. A similar hypothesis has been formulated for the lipoprotein OspA from the phylogenetically unrelated Borrelia burgdorferi, whose genome shows some similarities with those of M. pneumoniae and M. genitalium (14). Two of the common features are a large repertoire of lipoprotein genes and only two response-regulator two-component systems. OspA, one of the most abundant B. burgdorferi lipoproteins, is a host-protective antigen in Lyme disease and is subjected to differential expression for which the genetic basis is unknown (for a review, see reference 37). On the basis of structural studies, it was suggested that OspA may be a sensory element in the membrane, the ligand of which is still to be identified (26).

The identification of colonies which did not immunoreact with PAb 2 was striking because it suggested that either the complete set of expressed surface proteins can change or newly expressed surface polypeptide(s) provided a mask for those proteins recognized by PAb 2. Analysis of the TX-114 extracts from the variants P2 and P4 favored the second possibility because P35 continued to be present in these variants. This result is of particular importance, as it may reveal the putative role of these antigenic variations in the escape from the immune response. A heterogeneous reaction pattern of mycoplasma colonies to a polyclonal antiserum was previously described for another species, M. bovis (44), and the masking/unmasking of a lipoprotein epitope was found in assays using a MAb (44). In addition, there is a growing body of evidence that mycoplasma surface antigenic variation may provide a protective mechanism against the damage caused by the immune response. First, it was shown that the repertoire of variable antigens is changed after an experimentally induced infection (25). Second, it has been shown in vitro that, using as a selection pressure MAbs or antibodies from immunized or experimentally infected animals directed against surface antigens, it is possible to drive the antigenic variation in M. bovis (23). Third, M. hyorhinis variants expressing Vlp (variable lipoprotein) extended in length were resistant to complement-independent growth inhibition by host antibodies, whereas variants expressing shorter Vlp are more susceptible (9). Our data confirm the phase variations of immunodominant lipoproteins in mycoplasmas. This phenomenon associated with a large repertoire of possibly expressed antigens may allow them to evade the humoral immune response. It is also likely, although not documented in the literature, that phase variations also allow mycoplasmas to avoid damage from this host’s immune defense.

In contrast to other variable mycoplasma lipoproteins, we observed phase variation but no size variation of P35. Size variation has been associated with the presence of repetitive elements in the C terminus of the gene encoding the variable protein. The p35 gene has no such repeated elements. Size variation has been described, however, for surface antigens in Ureaplasma urealyticum, M. hyorhinis, M. pulmonis, and M. bovis (for a review, see reference 12).

The genetic mechanisms underlying the mycoplasma lipoprotein phase variations have been elucidated in a few cases: DNA rearrangements such as that described for the M. pulmonis Vsa antigens (2, 46), point mutations either within the promoter region (56) or within the gene itself (48, 57), and masking/unmasking of epitopes (44). In M. hyorhinis, the Vlp antigen phase variations are due to random size modifications of the poly(A) box within the vlp gene promoter (56). We have identified the promoter of the p35 gene and found that it presents some interesting features. The distance between the sites for initiation of transcription and translation is 132 bp, which is similar to that described for the promoter of M. hyorhinis Vlps (56). Although the sequence between the −35 box and the translation start codon has an A+T content of 84%, there is no poly(A) tract as was found between the −35 and −10 boxes of M. hyorhinis Vlp genes (56). The size variation of this repetitive tract was shown to be associated with phase variation of these lipoproteins (56). However, such an AT-rich region upstream from the transcription initiation site suggests DNA bending (51) due to the binding of regulatory proteins (36). This possibility is also supported by the presence of two dyad symmetries in the vicinity of the promoter. Since the P35 phase variation was not associated with DNA rearrangement or with mutation within the p35 gene or its promoter, we suggest that the regulated expression of p35 could be due to an as yet unidentified regulatory protein(s).

The demonstration of P35 phase variation has implications for the development and use of M. penetrans serological assays. Indeed, current enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays are based on a P35-containing TX-114 extract (17, 52). However, it is possible that P35 expression is necessary for the early stages of mycoplasma infection, and in this case we would expect to detect P35-specific antibodies in every M. penetrans-infected host. This possibility is supported by experimental infections. Alternatively, P35 may not be essential, in which case testing for anti P35 antibodies would be unsatisfactory. Our current estimates of the incidence of M. penetrans cases of infection, which is difficult to document because of the fastidious growth of the organism from clinical sites, may therefore be underestimated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

O.N. and I.C. equally contributed to this work.

We thank Emmanuelle Perret and Christine Schmitt for technical assistance with electron microscopy.

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche contre le SIDA and the Institut Pasteur. O.N. and I.C. were recipients of a fellowship from the Pasteur-Weizman Foundation and from the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, respectively.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

During the time that the present paper was being reviewed, an outstanding review on different aspects of mycoplasma biology, including antigen variations, was published (S. Razin, D. Yogev, and Y. Naot, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1094–1156, 1998). In addition, in another recently published paper (G. Pyrowolakis, D. Hofmann, and R., Herrmann, J. Biol. Chem. 273:24792–24796, 1998), a mycoplasma lipoprotein was found to have a key role in the cell metabolism as the subunit b of the F0F1-type ATPase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Behrens A, Heller M, Kirchhoff H, Yogev D, Rosengarten R. A family of phase- and size-variant membrane surface lipoprotein antigens (Vsps) of Mycoplasma bovis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5075–5084. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5075-5084.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhugra B, Voelker L L, Zou N, Yu H, Dybvig K. Mechanism of antigenic variation in Mycoplasma pulmonis: interwoven, site-specific DNA inversions. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:703–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanchard A, Montagnier L. AIDS-associated mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:687–712. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard A, Montagnier L, Gougeon M L. Influence of microbial infections on the progression of HIV disease. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:326–331. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bove J M. Molecular features of mollicutes. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:S10–S31. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_1.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner C, Neyrolles O, Blanchard A. Mycoplasmas and HIV infection: from epidemiology to their interaction with immune cells. Front Biosci. 1996;1:42–54. doi: 10.2741/a142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenner C, Wroblewski H, Le Henaff M, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Spiralin, a mycoplasmal membrane lipoprotein, induces T-cell-independent B-cell blastogenesis and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4322–4329. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4322-4329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Citti C, Kim M F, Wise K S. Elongated versions of Vlp surface lipoproteins protect Mycoplasma hyorhinis escape variants from growth-inhibiting host antibodies. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1773–1785. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1773-1785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Citti C, Rosengarten R. Mycoplasma genetic variation and its implication for pathogenesis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:562–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudler R, Schmidhauser C, Parish R W, Wettenhall R E, Schmidt T. A mycoplasma high-affinity transport system and the in vitro invasiveness of mouse sarcoma cells. EMBO J. 1988;7:3963–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dybvig K, Voelker L L. Molecular biology of mycoplasmas. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:25–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferris S, Watson H L, Neyrolles O, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Characterization of a major Mycoplasma penetrans lipoprotein and of its gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;130:313–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, Vanvugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Weidman J, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giron J A, Lange M, Baseman J B. Adherence, fibronectin binding, and induction of cytoskeleton reorganization in cultured human cells by Mycoplasma penetrans. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3419–3424. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.197-208.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grau O, Slizewicz B, Tuppin P, Launay V, Bourgeois E, Sagot N, Moynier M, Lafeuillade A, Bachelez H, Clauvel J P, et al. Association of Mycoplasma penetrans with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:672–681. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes M M, Li B J, Wear D J, Lo S C. Pathogenicity of Mycoplasma fermentans and Mycoplasma penetrans in experimentally infected chicken embryos. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3419–3424. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3419-3424.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li B C, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Himmelreich R, Plagens H, Hilbert H, Reiner B, Herrmann R. Comparative analysis of the genomes of the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Mycoplasma genitalium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:701–712. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Gall S, Prevost M C, Heard J M, Schwartz O. Human immunodeficiency virus type I Nef independently affects virion incorporation of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules and virus infectivity. Virology. 1997;229:295–301. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Grand D, Solsona M, Rosengarten R, Poumarat F. Adaptive surface antigen variation in Mycoplasma bovis to the host immune response. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemaitre M, Henin Y, Destouesse F, Ferrieux C, Montagnier L, Blanchard A. Role of mycoplasma infection in the cytopathic effect induced by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in infected cell lines. Infect Immun. 1992;60:742–748. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.742-748.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levisohn S, Rosengarten R, Yogev D. In vivo variation of Mycoplasma gallisepticum antigen expression in experimentally infected chickens. Vet Microbiol. 1995;45:219–231. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00039-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Dunn J J, Luft B J, Lawson C L. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein A complexed with an Fab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo S C, Hayes M M, Kotani H, Pierce P F, Wear D J, Newton P B, Tully J G, Shih J W. Adhesion onto and invasion into mammalian cells by Mycoplasma penetrans: a newly isolated mycoplasma from patients with AIDS. Mod Pathol. 1993;6:276–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo S C, Hayes M M, Tully J G, Wang R Y, Kotani H, Pierce P F, Rose D L, Shih J W. Mycoplasma penetrans sp. nov., from the urogenital tract of patients with AIDS. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:357–364. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lo S C, Hayes M M, Wang R Y, Pierce P F, Kotani H, Shih J W. Newly discovered mycoplasma isolated from patients infected with HIV. Lancet. 1991;338:1415–1418. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92721-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo S C, Tsai S, Benish J R, Shih J W, Wear D J, Wong D M. Enhancement of HIV-1 cytocidal effects in CD4+ lymphocytes by the AIDS-associated mycoplasma. Science. 1991;251:1074–1076. doi: 10.1126/science.1705362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lysnyansky I, Rosengarten R, Yogev D. Phenotypic switching of variable surface lipoproteins in Mycoplasma bovis involves high-frequency chromosomal rearrangements. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5395–5401. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5395-5401.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markham P F, Glew M D, Sykes J E, Bowden T R, Pollocks T D, Browning G F, Whithear K G, Walker I D. The organisation of the multigene family which encodes the major cell surface protein, pMGA, of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00991-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muhlradt P F, Kiess M, Meyer H, Sussmuth R, Jung G. Isolation, structure elucidation, and synthesis of a macrophage stimulatory lipopeptide from Mycoplasma fermentans acting at picomolar concentration. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1951–1958. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neyrolles O, Eliane J-P, Ferris S, Ayr Florio da Cunha R, Prevost M-C, Bahraoui E, Blanchard A. Antigenic characterization and cytolocalization of P35, the major Mycoplasma penetrans antigen. Microbiology. 1999;145:343–355. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Martin J, de Lorenzo V. Clues and consequences of DNA bending in transcription. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:593–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Philipp M T. Studies on OspA: a source of new paradigms in Lyme disease research. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:44–47. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollack J D. Mycoplasma genes: a case for reflective annotation. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)01113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollack J D, Williams M V, Banzon J, Jones M A, Harvey L, Tully J G. Comparative metabolism of Mesoplasma, Entomoplasma, Mycoplasma, and Acholeplasma. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:885–890. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollack J D, Williams M V, McElhaney R N. The comparative metabolism of the mollicutes (Mycoplasmas): the utility for taxonomic classification and the relationship of putative gene annotation and phylogeny to enzymatic function in the smallest free-living cells. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1997;23:269–354. doi: 10.3109/10408419709115140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawadi G, Roman-Roman S. Mycoplasma membrane lipoproteins induced proinflammatory cytokines by a mechanism distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1996;64:637–643. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.637-643.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosengarten R, Behrens A, Stetefeld A, Heller M, Ahrens M, Sachse K, Yogev D, Kirchhoff H. Antigen heterogeneity among isolates of Mycoplasma bovis is generated by high-frequency variation of diverse membrane surface proteins. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5066–5074. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5066-5074.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosengarten R, Theiss P M, Yogev D, Wise K S. Antigenic variation in Mycoplasma hyorhinis: increased repertoire of variable lipoproteins expanding surface diversity and structural complexity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2224–2228. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2224-2228.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosengarten R, Yogev D. Variant colony surface antigenic phenotypes within mycoplasma strain populations: implications for species identification and strain standardization. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:149–158. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.149-158.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simmons W L, Zuhua C, Glass J I, Simecka J W, Cassell G H, Watson H L. Sequence analysis of the chromosomal region around and within the V-1-encoding gene of Mycoplasma pulmonis: evidence for DNA inversion as a mechanism for V-1 variation. Infect Immun. 1996;64:472–479. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.472-479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theiss P, Karpas A, Wise K S. Antigenic topology of the P29 surface lipoprotein of Mycoplasma fermentans: differential display of epitopes results in high-frequency phase variation. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1800–1809. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1800-1809.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Theiss P, Wise K S. Localized frameshift mutation generates selective, high-frequency phase variation of a surface lipoprotein encoded by a mycoplasma ABC transporter operon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4013–4022. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4013-4022.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W—improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tully J G, Whitcomb R F, Clark H F, Williamson D L. Pathogenic mycoplasmas: cultivation and vertebrate pathogenicity of a new spiroplasma. Science. 1977;195:892–894. doi: 10.1126/science.841314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.VanWye J D, Bronson E C, Anderson J N. Species-specific patterns of DNA bending and sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5253–5261. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.19.5253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang R Y, Shih J W, Grandinetti T, Pierce P F, Hayes M M, Wear D J, Alter H J, Lo S C. High frequency of antibodies to Mycoplasma penetrans in HIV-infected patients. Lancet. 1992;340:1312–1316. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92493-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang R Y, Shih J W, Weiss S H, Grandinetti T, Pierce P F, Lange M, Alter H J, Wear D J, Davies C L, Mayur R K, et al. Mycoplasma penetrans infection in male homosexuals with AIDS: high seroprevalence and association with Kaposi’s sarcoma. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:724–729. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wieslander A, Boyer M J, Wróblewski H. Membrane protein structure. In: Maniloff J, McElhaney R N, Finch L R, Baseman J B, editors. Mycoplasmas: molecular biology and pathogenesis. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wise K S. Adaptive surface variation in mycoplasmas. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(93)90034-O. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55a.Yanez, A., L. Cedillo, J. Rojas M.-C. Prévost, O. Neyrolles, E. Alonso, H. L. Watson, A. Blanchard, and G. H. Cassell. Mycoplasma penetrans bacteremia associated with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Yogev D, Rosengarten R, Watson-McKown R, Wise K S. Molecular basis of Mycoplasma surface antigenic variation: a novel set of divergent genes undergo spontaneous mutation of periodic coding regions and 5′ regulatory sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:4069–4079. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Q, Wise K S. Localized reversible frameshift mutation in an adhesin gene confers a phase-variable adherence phenotype in mycoplasma. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:859–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]