Abstract

A protective effect of interleukin-10 (IL-10) against the development of lethal shock has been demonstrated in various animal models. In contrast, the immunosuppressant properties of this mediator have been minimally evaluated in low-mortality models of infections. The clinical, microbiological, and inflammatory effects of murine recombinant IL-10 (mrIL-10) therapy were evaluated in two models of peritonitis in rats, which differed in the degree of severity of peritoneal inflammation 3 days after inoculation of Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis with or without Enterococcus faecalis. The severity of the disease remained unchanged compared to that in control animals. A dose-related decrease in the peritoneal phagocyte count was observed in the treated groups compared to the counts in control animals. The subsequent experiments were performed exclusively in the mixed gram-positive–gram negative model, which exhibits an intense and prolonged inflammatory response with similar criteria. The early effects of mrIL-10 (evaluated 6 h after inoculation), repeated injections of mrIL-10 (four doses injected from 0 to 9 h after bacterial challenge), and pretreatment (two doses injected 6 and 3 h before inoculation) were evaluated. The clinical and microbiological parameters remained unchanged in the treated animals. Decreases in the peritoneal phagocyte count and the peritoneal concentration of tumor necrosis factor were observed following repeated injections of mrIL-10. In summary, our data suggest that mrIL-10 does not worsen the manifestations of sepsis. However, these results need to be confirmed in clinical practice.

Proinflammatory cytokines play a key role in amplification of the inflammatory response and in activation of phagocytes in the course of sepsis. These agents play a beneficial role by amplifying the inflammatory cascade, but detrimental overproduction of these mediators has also been demonstrated in septic shock and acute lung injury (28). The concept underlying the anticytokine approach to sepsis is that this overdeveloped inflammatory response occurs as a result of failure of the normal inflammation control mechanisms. However, it can be difficult to determine whether an inflammatory mediator is harmful or beneficial. The same treatment, designed to block a given mediator, could be beneficial or harmful, depending on the type of infection and the time of administration. For example, in experimental models of septic shock, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antibodies provide protection in intravenous bolus models but are not beneficial in an experimental peritonitis model (2, 41) and, in some studies, are actually harmful (11).

An emerging concept suggests that the clinical manifestations of septic shock can be considered to be due to an imbalance in the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (28). The increased production of anti-inflammatory mediators, especially interleukin-10 (IL-10), observed in inflammation and sepsis occurs in parallel with massive production of proinflammatory cytokines (14, 21). IL-10, a pleiotropic cytokine which can exert an immunosuppressant effect on macrophage functions, has been shown to attenuate the production of various proinflammatory mediators (9, 13, 30, 36). A protective effect of IL-10 against the development of lethal endotoxic shock has also been demonstrated in several animal studies (13, 16, 34, 37).

On the other hand, IL-10 decreases the oxidative burst of macrophages and their phagocytic properties (25). In mice infected by Candida albicans, killing of fungus and nitric oxide secretion are inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by IL-10 (5). Since an adequate inflammatory response is instrumental for bacterial clearance in the course of sepsis, the administration of IL-10 might be hazardous, as reported in experimental models of pneumonia (15, 38). However, the immunosuppressant properties of this mediator on bacterial clearance have been only minimally evaluated, especially in low-mortality models of sepsis and in mixed infection. This is an important point, as recent advances have demonstrated a beneficial effect of IL-10 in the treatment of Crohn’s disease (39), a clinical setting in which gastrointestinal tract perforation is not uncommon during exacerbations of the disease.

In order to clarify the potentially harmful consequences of this anti-inflammatory cytokine, we evaluated the clinical, microbiological, and inflammatory effects of murine recombinant IL-10 (mrIL-10) therapy in two models of polymicrobial peritonitis in rats, which differed in the inoculum and the inflammatory response and which featured conditions similar to those observed in human peritoneal infection (10, 22, 23).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

Three previously described strains of bacteria (22, 23) were used for this study: an encapsulated strain of Bacteroides fragilis, AIP5-86; a strain of Escherichia coli, CB1496 (6), and a strain of Enterococcus faecalis, UA174 (17).

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley pathogen-free rats (Charles River France, St-Aubin-les-Elbeuf, France) weighing 200 to 250 g and housed five per cage were used for all experiments. All animals had access to chow and water ad libitum throughout the experiment. The procedures followed were in agreement with the guidelines of the European regulation for the conduct of animal experimentation.

Preparation of inoculum.

B. fragilis was grown and diluted anaerobically in prereduced thioglycolate broth, while E. coli and E. faecalis were grown in brain heart infusion broth. The final mixtures of strains were prepared at the log phase of growth. The bacterial cultures were diluted to obtain the required numbers of microorganisms for challenge.

Based on our experience of this model of intra-abdominal infection, we used different models of peritoneal injury differing in the degree of severity of peritoneal inflammation (10, 23). In the first model (model I), the animals received sterile broth. In the second model (model II), the animals received a capsule containing a gram-negative bacterial inoculum consisting of B. fragilis (5 × 107 CFU per ml) and E. coli (108 CFU/ml). In the third model (model III), the animals received a capsule containing a mixed inoculum consisting of E. faecalis (108 CFU/ml), B. fragilis (5 × 107 CFU/ml), and E. coli (108 CFU/ml). Assessment of the purity and validation of the counts of each strain were performed immediately before they were mixed.

Semisolid agar medium was prepared by adding 2% (wt/vol) agar to the diluted broth cultures combined with barium sulfate (10% [wt/vol]). Aliquots (0.5 ml) of the final mixture were placed in double gelatin capsules for intraperitoneal implantation.

Implantation of inoculum.

The rats were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (30 mg/kg of body weight), and the gelatin capsule was inserted into the pelvic cavity through a midline abdominal incision (40). The wound was closed with a musculoperitoneal layer and a skin layer with interrupted nylon sutures.

Evaluation of treatment.

After implantation of the inoculum, the animals were returned to separate cages. No death was observed within 6 h of capsule implantation. The primary endpoint was survival of the animals. The other endpoints of the study were the course of clinical parameters (daily measurements of body weight and temperature), microbiological parameters (positivity of blood cultures and peritoneal pathogen counts), and inflammatory response (peritoneal phagocyte counts and determination of the peritoneal concentration of proinflammatory cytokines [TNF and IL-6]), corresponding to the secondary endpoints.

mrIL-10.

Recombinant murine IL-10 (mrIL-10), a 160-amino-acid nonglycosylated protein produced in E. coli by expression of the gene sequence corresponding to the mature murine protein (24), was provided by the Schering Plough Research Institute (Kenilworth, N.J.).

Pharmacokinetic study.

Plasma mrIL-10 levels were evaluated in three groups of animals receiving a single intramuscular dose of 125, 250, or 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg. Blood samples (1 ml) were drawn via an arterial catheter immediately before injection and 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300 min after intramuscular injection. Five animals of each group were used for each point. The plasma and peritoneal mrIL-10 concentrations were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Genzyme, Tebu S.A., St-Quentin-en-Yvelines, France). The limit of detection in serum and peritoneal fluid was 0.03 ng/ml.

Evaluation of mrIL-10 activity.

In the first part of the study, three models (sterile inflammatory model [model I], infection with gram-negative organisms [model II], and mixed gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial inoculum [model III]), were used to assess the efficacy of mrIL-10. In each model, three groups of 10 animals were randomly assigned to receive, at the time of bacterial challenge, either placebo or a single intramuscular injection of 125 or 250 μg of mrIL-10/kg. The choice of these doses was based on the results of a pharmacokinetic study and was designed to achieve the concentrations of mediator in plasma observed in human studies (39).

The initial period of infection, characterized by signs of acute infection (e.g., 10 to 15% weight loss, bacteremia, and high concentrations of microorganisms and inflammatory mediators in peritoneal fluid and blood), was deliberately disregarded (10, 23). We focused our evaluation on day 3 after bacterial challenge. This period was chosen as a good compromise to evaluate the late expression of inflammatory response and persistent microbiological response (10, 23).

Experiments with the mixed gram-positive–gram-negative model (model III).

The subsequent experiments were performed exclusively in model III (mixed gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial inoculum), which exhibits an intense and prolonged inflammatory response (10, 23).

The early effects of mrIL-10 therapy were evaluated in five groups of five animals each randomly assigned to receive, at the time of inoculation, either placebo, a single intramuscular injection of mrIL-10 (125, 250, or 500 μg/kg), or a dose of 125 μg of mrIL-10/kg repeated at the third hour after bacterial challenge. Plasma and peritoneal concentrations of TNF, IL-6, and IL-10 were determined 6 h after bacterial challenge.

The effect of repeated injections of mrIL-10 (four doses injected at 0, 3, 6, and 9 h after bacterial challenge) was evaluated in three groups of five animals each receiving either placebo or 250 or 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg for each injection. In this part of the study, we evaluated the clinical, microbiological, and inflammatory effects of mrIL-10 therapy 3 days after inoculation.

The effect of mrIL-10 administered before bacterial challenge was evaluated in a group of five animals pretreated with 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg given 6 and 3 h before inoculation. The clinical, microbiological, and inflammatory parameters were evaluated on day 3 after challenge.

Microbiological study.

At the time of sacrifice, the animals were killed with chloroform. Blood samples were obtained by aseptic percutaneous transthoracic cardiac puncture.

A midline laparotomy was performed, and 10 ml of sterile saline was injected into the peritoneal cavity. Peritoneal fluid samples were collected from all regions of the peritoneal cavity. A dilution factor, taking into account the fluid present in the peritoneal cavity prior to injection of the peritoneal lavage, was applied to all calculations. We used urea as an endogenous marker of peritoneal dilution. Since urea readily diffuses throughout the body, the plasma and peritoneal fluid urea concentrations are the same (19). Consequently, when the urea concentrations in plasma and a peritoneal lavage sample are known, the dilution of the initial volume of peritoneal fluid obtained can be calculated as previously described (10, 23): dilution factor = (plasma urea concentration)/(peritoneal fluid urea concentration). Once the dilution factor has been determined, the concentration of any component in the peritoneal fluid (e.g., bacteria, cells, or cytokines) can be assessed. The urea contents of peritoneal fluid and plasma were determined by using a commercially available kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France).

A 0.5-ml aliquot of the peritoneal fluid sample was serially diluted, and 0.1 ml of each dilution was spread onto agar plates for bacterial counts. The limit of detection for each microbiological test was <1 × log10 CFU/ml. In every case, the plates were incubated in the appropriate environments (i.e., jars or air) for 2 to 5 days. The selective medium used for detection of B. fragilis was Columbia agar base (BioMérieux, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) with 5% sheep blood containing 75 μg of kanamycin, 7.5 μg of vancomycin, and 4 μg of pefloxacin per ml. The selective media used for culture of aerobes were Drigalski agar (Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) for E. coli and bile-esculin-azide agar (Diagnostics Pasteur) for E. faecalis.

Quantitation of host peritoneal leukocyte populations.

Total cell counts were performed on an aliquot of the original peritoneal fluid with a Malassez counting chamber. Aliquots of original fluid, adjusted to 5 × 104 cells, were cytocentrifuged with a Cytospin 2 (Shandon Southern Products, Cheshire, England), and individual preparations were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa or Gram stains. Differential cell counts were performed by examining at least 300 cells. The mean total intraperitoneal leukocyte count and the total macrophage and polymorphonuclear neutrophil populations were calculated and expressed as percentages of the total cell count.

Cytokine assays.

Blood samples were drawn by cardiac puncture and placed in sterile glass tubes. After coagulation, the sera were divided into aliquots and kept at −70°C until being assayed. Four 1-ml samples of the original peritoneal fluid collected from all regions of the peritoneal cavity were centrifuged (300 g for 15 min) and then divided into aliquots and stored at −70°C until being assayed. The serum and peritoneal samples were assayed in triplicate, and the standard deviation (SD) was <10% of the mean.

TNF activity was determined by a previously described cytotoxicity assay (23). Human recombinant TNF-α (Genzyme, Tebu S.A.) was used to establish the limits of detection of these assays. The limit of detection in serum and peritoneal fluid was 0.12 ng/ml. The specificity of the response for TNF was assessed with an anti-murine TNF antibody immunoglobulin fraction (Immugenex, Los Angeles, Calif.).

IL-6 activity was measured by a previously described bioassay with the murine hybridoma cell line B9 (23). Human recombinant IL-6 (Immugenex) was used to establish the limit of detection of these assays. The limit of detection in serum and peritoneal fluid was 0.1 ng/ml. The specificity of the response for IL-6 was assessed with polyclonal rabbit anti-murine IL-6 antibodies (Genzyme, Tebu S.A.).

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SDs. All continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance, followed, in the case of significance, by limited comparison of means by Fisher’s least-significant difference procedure (33) between untreated control animals and treated animals, according to an a priori decision. Comparisons of proportions were analyzed by a chi-square test, Yates’ correction, and Fisher exact tests, depending on the sample size. Statistical significance was inferred for comparisons for which P was <0.05.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetic study.

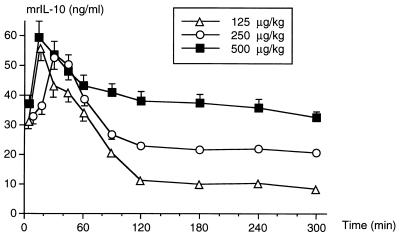

The plasma mrIL-10 peak was observed between 15 and 30 min after intramuscular injection of the mediator. Progressively decreasing values were then recorded for the following 4 h (Fig. 1). At the fifth hour after injection, the mrIL-10 concentration remained well above the limit of detection.

FIG. 1.

Plasma mrIL-10 concentrations measured after intramuscular injection of 125, 250, or 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg, assayed in groups of five animals. The results are expressed as means ± SDs.

Effects of mrIL-10 therapy on outcome.

Seven animals died within 24 and 72 h after inoculation. No death was observed in model I (the nonseptic model). A trend towards increased mortality was observed in model II (the E. coli-plus-B. fragilis model): there were one death in the control group and four deaths in the group receiving 250 μg of mrIL-10/kg (90 versus 60% surviving, respectively). This difference was not statistically significant. This trend was not observed in model III (E. coli-plus-B. fragilis-plus-E. faecalis model): there were one death in the control group and one death in the group treated with 125 μg of mrIL-10/kg. All the animals which died before sacrifice were replaced.

The lack of significance in these results can be attributed to an insufficient number of animals. Therefore, we cannot exclude possible harmful effects of IL-10 on outcome, but the results presented here do not indicate any obvious, marked increase in mortality.

Effects of mrIL-10 therapy on clinical parameters.

Following peritoneal implantation of the gelatin capsule, the degree of emaciation observed varied according to the model used, with the most severe weight loss observed in model III. This weight loss was maximal on day 1, followed by progressive recovery. We did not observe any significant change in the weight curve of the treated animals compared to that of the control animals in any of the models studied (data not shown).

After peritoneal implantation of the gelatin capsule, fever was observed in each group, with no difference in intensity among the groups (data not shown). The body temperature of treated animals was also not significantly different from that of control animals (data not shown).

Effects of mrIL-10 therapy on microbiological parameters.

The frequency of positive blood cultures for each pathogen in control and treated animals is shown in Table 1. No significant change in the frequency of positive blood cultures was observed following mrIL-10 therapy in any of the models studied.

TABLE 1.

Results of blood cultures obtained at the time of sacrifice from the two models of infected animals receiving either placebo (control) or mrIL-10 at a dose of 125 or 250 μg/kg

| Regimen | Resultsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II

|

Model III

|

||||

| E. coli | B. fragilis | E. coli | B. fragilis | E. faecalis | |

| Control | 6/10 | 8/10 | 5/10 | 10/10 | 5/10 |

| 125 μg/kg | 5/10 | 8/10 | 3/10 | 9/10 | 1/10 |

| 250 μg/kg | 7/10 | 8/10 | 5/10 | 10/10 | 6/10 |

Data are expressed as number of animals with positive blood cultures/total number of animals. For the significance of experimental groups, see Materials and Methods.

The bacterial concentrations determined in the peritoneal fluid of the animals are shown in Table 2. No significant change in peritoneal fluid bacterial concentration was observed, regardless of the model used or the dose of mrIL-10 injected.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial titers within the peritoneal cavity (log10 CFU/ml) obtained at the time of sacrifice from the two models of infected animals receiving either placebo (control) or mrIL-10 at a dose of 125 or 250 μg/kg

| Regimen | Resultsa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model II

|

Model III

|

||||

| E. coli | B. fragilis | E. coli | B. fragilis | E. faecalis | |

| Control | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 3 ± 0.7 |

| 125 μg/kg | 4 ± 1 | 4.5 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 0.7 |

| 250 μg/kg | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 4.2 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 1.2 |

Results are expressed as means ± SDs (10 animals in each group). For the significance of experimental groups, see Materials and Methods.

Effects of mrIL-10 therapy on inflammatory parameters.

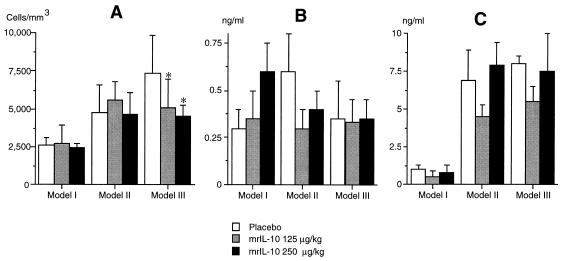

The peritoneal cell counts at the time of sacrifice are shown in Fig. 2. In control animals, a higher concentration of phagocytes in peritoneal fluid was observed in model III than in the Enterococcus-free septic model (model II). In the model exhibiting the most intense inflammatory response (model III), a dose-related decrease in the peritoneal cell count was observed compared to that in untreated animals (Fig. 2). In contrast, we did not observe any significant difference between control and treated animals in the differential count of peritoneal cells (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Phagocyte counts (A) and concentrations of TNF (B) and IL-6 (C) in peritoneal fluid on day 3 in uninfected animals (model I) and infected animals (models II and III) receiving either placebo or mrIL-10 at a dose of 125 or 250 μg/kg injected intramuscularly at the time of bacterial challenge. The results are expressed as means + SDs (10 animals in each group). ∗, P < 0.05 compared to placebo.

The TNF and IL-6 concentrations in peritoneal fluid of control animals and treated animals were similar, regardless of the mrIL-10 concentration injected in the three models (Fig. 2).

Early effects of mrIL-10 therapy on model III.

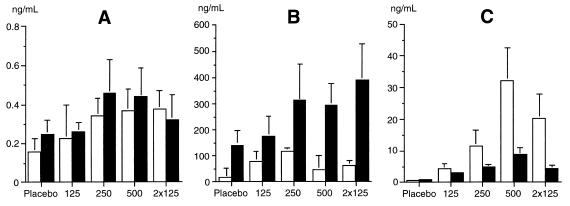

The plasma and peritoneal fluid concentrations of TNF, IL-6, and IL-10 are shown in Fig. 3. We did not observe any significant difference in peritoneal or plasma TNF or IL-6 concentrations following mrIL-10 injection.

FIG. 3.

TNF (A), IL-6 (B), and IL-10 (C) concentrations in plasma (open bars) and peritoneal fluid (solid bars) collected 6 h after bacterial challenge in five groups of five infected animals receiving, at the time of bacterial challenge, an intramuscular injection of placebo; a dose of 125, 250, or 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg; or a dose of 125 μg/kg repeated 3 h after inoculation (2× 125). The results are expressed as means + SDs.

The peritoneal fluid mrIL-10 concentrations were 5 to 10 times higher than the endogenous IL-10 concentration measured in untreated control animals (Fig. 3).

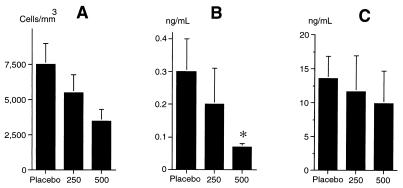

Effects of repeated injections of mrIL-10 on model III.

No difference in clinical or microbiological parameters was observed between treated and untreated control animals following repeated injections of mrIL-10 (data not shown). In contrast, significant decreases in the peritoneal phagocyte count and TNF concentration (Fig. 4) were observed.

FIG. 4.

Phagocyte counts (A) and concentrations of TNF (B) and IL-6 (C) in peritoneal fluid collected on day 3 in three groups of five infected animals receiving four doses of either placebo or 250 or 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg injected intramuscularly between the time of bacterial challenge and the ninth hour of the study. The results are expressed as means + SDs. ∗, P < 0.05 compared to placebo.

Effects of pretreatment by mrIL-10 on model III.

No difference in clinical or microbiological parameters was observed between the group of animals receiving two doses of 500 μg of mrIL-10/kg before bacterial challenge and the untreated control animals (data not shown). In addition, no significant difference in peritoneal cell count was observed between these animals and untreated control animals. The peritoneal fluid concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines were similar in control and treated animals (0.35 ± 0.1 versus 0.57 ± 0.2 ng/ml for TNF and 11.1 ± 3.2 versus 9.8 ± 4.6 ng/ml for IL-6 in control and treated animals, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In our model of moderately severe polymicrobial peritonitis, we did not observe any harmful effects following administration of mrIL-10. Moreover, despite decreased phagocyte counts and TNF concentrations in peritoneal fluid, we did not observe any significant alteration of clinical or microbiological parameters.

Protective effects of mrIL-10 have been reported in the literature in various fatal models with bacteria (18, 37) or bacterial toxins (3, 12, 13, 16). This protection is canceled by the administration of specific anti-IL-10 antibodies (15) or by pretreatment with anti-IL-10 antibodies (37). Abundant data support the hypothesis of a balance between TNF-α and endogenous IL-10. This issue was recently confirmed in a study by Berg et al. performed on a group of mice with deficient IL-10 production (4). In these animals, the lethal dose of lipopolysaccharide was 20-fold lower than for control mice. The high mortality rate of these IL-10-deficient animals challenged with modest doses of lipopolysaccharide was correlated with TNF production, as treatment with anti-TNF antibodies resulted in 70% survival. These results confirm the hypothesis of an autoregulatory feedback loop between these two mediators (35).

Many of the animal models used to evaluate the effects of anti-inflammatory therapies are obtained by an intravenous bolus of bacteria or bacterial toxins in an otherwise healthy animal. These experimental designs may not resemble the development of infection in patients, which commonly occurs progressively over several days. The bolus model may be better suited to illustrate potentially pathologic events in sepsis than to demonstrate the therapeutic benefit of a particular therapy, while the peritonitis model may produce results which can be more readily extrapolated to infectious diseases in humans (8, 28). Moreover, the nature of the organisms inoculated in these models, essentially gram-negative bacilli, does not take into account the increasing role of gram-positive cocci in sepsis (32) and the mixed isolates frequently observed in clinical practice.

Since a large part of our study focused on the microbiological effects of the mediator, we deliberately chose to evaluate the host response at day 3, a time when the intergroup differences might have been more pronounced than at an earlier time in the course of the disease (10, 22, 23). We hypothesized that any alteration in the phagocytic properties of the peritoneal fluid would lead to persistently increased concentrations of microorganisms, a feature more easily detected at this period than during the first 24 h of the disease. Moreover, analysis confined to the first 24 h of the disease could have missed late deaths due to persistent infection.

In the present study, a nonsignificantly increased mortality was observed in group II animals treated with high doses (250 μg/kg) of mrIL-10. Due to an insufficient number of animals, it is impossible to draw any definitive conclusions about the absence of harmful effects of the mediator. The statistical power of this study could have been improved by increasing the number of animals included in each group. However, the high number of subjects theoretically required to reach significance would induce major technical and ethical concerns. Consequently, we are unable to draw conclusions about a harmful effect of mrIL-10 in this setting. On the other hand, we cannot exclude a possible effect of this mediator in a small number of animals. This trend needs to be confirmed in clinical practice. However, to the best of our knowledge, most studies evaluating the effect of mrIL-10 in the bloodstream (3, 4, 12, 13, 16, 34, 36) or in peritoneal infections (18, 37) have demonstrated beneficial effects of the mediator. An increased susceptibility to sepsis was observed only in two models of bacterial pneumonia (15, 38) and a model of hemorrhagic shock associated with increased plasma concentrations of anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10 (1).

The pharmacokinetic study and the serum and peritoneal mrIL-10 concentrations, assayed at hour 6 after injection, demonstrated adequate concentrations of the mediator and excluded the possibility of inadequate pharmacokinetics of mrIL-10. It must be emphasized that the concentrations of the mediator obtained in this study are similar to those achieved in human investigations (39). The species specificity of mrIL-10 might also explain the lack of activity in rats. However, rat IL-10 nucleotide sequences are 90% homologous to those of mouse IL-10 (26). In addition, the effects of IL-10 seem to be minimally influenced by the species barrier. Recombinant human IL-10 has been reported to be active in rabbits (31) and rats (20), while a substantial protective activity of mrIL-10 has been reported in two models of lung inflammation in rats (7, 27). Finally, the decreased peritoneal phagocyte counts and TNF concentrations observed in the present study reflect the activity of the mediator.

The absence of any major clinical impact of IL-10 could be related to inadequate concentrations of the mediator at the site of infection, as compartmentalization of sepsis might be involved in this poor response. Recently, Paris et al. demonstrated that very high doses of IL-10 (1 mg/kg given intravenously) were required to significantly reduce the inflammatory response in an experimental model of meningitis in rabbits, while 10 μg of the mediator injected intracisternally achieved similar results (31). The high mrIL-10 concentrations measured in peritoneal fluid in our study suggest that the hypothesis of an inadequate concentration of the mediator can be excluded.

Although IL-10 mediates protection by controlling the early effectors of endotoxic shock, such as TNF-α, this mediator is unable to directly antagonize the production and/or actions of late-appearing effector molecules, such as nitric oxide (4). The appropriate timing of IL-10 administration in therapeutic challenges must therefore be determined. In studies evaluating the protective effects of IL-10 in peritonitis, the time effect of IL-10 appeared to be somewhat controversial. Van der Poll et al. demonstrated that endogenous IL-10 was detected in plasma within 2 h after challenge (37). In a therapeutic challenge with mrIL-10 in mice, Kato et al. reported a protective effect only when the mediator was administered 6 h after induction of sepsis, while treatment with the same dose of IL-10 administered simultaneously with the induction of peritonitis had no effect on survival (18). In the present study, we did not identify any specific relationship between the timing of administration of the mediator and the effects reported.

In the present study, the most consistent effect of mrIL-10 was a decreased peritoneal leukocyte count. This effect on the phagocyte count has been previously reported in lung injury and could be attributed to decreased cellular recruitment and increased neutrophil apoptosis (7). In the present study, the decrease of peritoneal phagocytes was more pronounced in model III than in model II, suggesting that the effects of IL-10 might be more pronounced in severe inflammation. This issue was previously addressed by Opal et al. in the phase III trial of IL-1 receptor antagonist performed in septic patients. These authors observed that nonendotoxemic patients did not appear to benefit from IL-1 receptor antagonist (29). Clinical situations with exaggerated inflammatory response to sepsis might therefore be more likely to respond to anticytokine therapy.

In summary, our data suggest that, in the two models of mixed infection studied, mrIL-10 does not worsen the clinical and microbiological manifestations of sepsis, even when the inoculum includes gram-positive cocci. These results might be of interest in clinical practice, as exogenous IL-10 could be an effective new therapeutic approach to human inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease (39). However, these conclusions need to be confirmed in clinical practice in order to establish the apparent good tolerance of the mediator. Finally, our data emphasize the limited understanding, illustrated by previous studies (10), of the mechanisms involved in the inflammatory response, which depend on the animal species, the type of infection, and the nature of the organisms inoculated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anthony Saul for his contribution to the preparation of the manuscript.

Grant support was received from Schering Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayala A, Lehman D L, Herdon C D, Chaudry I H. Mechanism of enhanced susceptibility to sepsis following hemorrhage. Interleukin-10 suppression of T-cell response is mediated by eicosanoid-induced interleukin-4 release. Arch Surg. 1994;129:1172–1178. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420350070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagby G J, Plessala K J, Wilson L A, Thompson J J, Nelson S. Divergent efficacy of antibody to tumor necrosis factor-α in intravascular and peritonitis models of sepsis. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:83–88. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bean A G, Freiberg R A, Andrade S, Menon S, Zlotnik A. Interleukin 10 protects mice against staphylococcal enterotoxin B-induced lethal shock. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4937–4939. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4937-4939.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg D J, Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller W, Menon S, Davidson N, Grünig G, Rennick D. Interleukin-10 is a central regulator of the response to LPS in murine models of endotoxic shock and the Schwartzman reaction but not endotoxin tolerance. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:2339–2347. doi: 10.1172/JCI118290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cenci E, Romani L, Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Schiaffela E, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-10 inhibit nitric oxide-dependent macrophage killing of Candida albicans. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1034–1038. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Contrepois A, Vallois J M, Garaud J J, Pangon B, Mohler J, Meulemans A, Carbon C. Kinetics and bactericidal effect of gentamicin and latamoxef (moxalactam) in experimental Escherichia coli endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986;17:227–237. doi: 10.1093/jac/17.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox G. IL-10 enhances resolution of pulmonary inflammation in vivo by promoting apoptosis of neutrophils. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L566–L571. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross A S, Opal S M, Sadoff J C, Gemski P. Choice of bacteria in animal models of sepsis. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2741–2747. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2741-2747.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor C G, de Vries J. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupont H, Montravers P, Mohler J, Carbon C. Disparate findings on the role of virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis in mouse and rat models of peritonitis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2570–2575. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2570-2575.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Echtenacher B, Falk W, Mannel D N, Krammer P H. Requirement of endogenous tumor necrosis factor/cachectin for recovery from experimental peritonitis. J Immunol. 1990;145:3762–3766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florquin S, Amraoui Z, Abramowicz D, Goldman M. Systemic release and protective role of IL-10 in staphylococcal enterotoxin B-induced shock in mice. J Immunol. 1994;153:2618–2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gérard C, Bryuns C, Marchant A. IL-10 reduces the release of tumor necrosis factor and prevents lethality in experimental endotoxemia. J Exp Med. 1993;177:547–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez-Jimenez J, Martin M C, Sauri R, Segura R M, Esteban F, Ruiz J C, Nuvials X, Boveda J L, Peracaula R, Salgado A. Interleukin-10 and the monocyte/macrophage-induced inflammatory response in septic shock. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:472–475. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberger M J, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L, Danforth J M, Goodmen R E, Standiford T J. Neutralization of IL-10 increases survival in a murine model of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Immunol. 1995;155:722–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard M, Muchamuel T, Andrade S, Menon S. Interleukin-10 protects mice from lethal endotoxemia. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1205–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob A E, Hobbs S J. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:360–372. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.360-372.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato T, Murata A, Ishida H, Toda H, Tanaka N, Hayashida H, Monden M, Matsuura N. Interleukin 10 reduces mortality from severe peritonitis in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1336–1340. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelton J G, Ulan R, Stiller C, Holmes E. Comparison of chemical composition of peritoneal fluid and serum: a method for monitoring dialysis patients and a tool for assessing binding to serum proteins in vivo. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:67–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koedel V, Bernatowicz A, Frei K, Fontana A, Pfister H W. Systemically (but not intrathecally) administered IL-10 attenuates pathophysiologic alterations in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:5185–5191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchant A, Deviere J, Byl B, De Groote D, Vincent J L, Goldman M. Interleukin-10 production during septicaemia. Lancet. 1994;343:707–708. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91584-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montravers P, Andremont A, Massias L, Carbon C. Investigation of the potential role of Enterococcus faecalis in the pathophysiology of experimental peritonitis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:821–830. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montravers P, Mohler J, Saint-Julien L, Carbon C. Evidence of the proinflammatory role of Enterococcus faecalis in polymicrobial peritonitis in rats. Infect Immun. 1997;65:144–149. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.144-149.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore K W, Vieira P, Fiorentino D F, Trounstine M L, Khan T A, Mosmann T R. Homology of cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (IL-10) to the Epstein-Barr virus gene BCRFI. Science. 1990;248:1230–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.2161559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosmann T. Properties and functions of interleukin 10. Adv Immunol. 1994;56:1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosmann T R. Interleukin-10. In: Thomson A W, editor. The cytokine handbook. 2nd ed. London, England: Academic Press Ltd.; 1994. pp. 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulligan M S, Jones M L, Vaporciyan A A. Prospective effects of IL-4 and IL-10 against immune complex-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 1993;151:5666–5674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natanson C, Hoffman W D, Suffredini A F, Eichacker P Q, Danner R L. Selected treatment strategies for septic shock based on proposed mechanisms of pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:771–783. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opal S M, Fisher C J, Dhainaut J F, Vincent J L, Brase R, Lowry S F, Sadoff J C, Slotman G J, Levy H, Balk R A, Selly M P, Pribble J P, LaBrecque J F, Lookabaugh J, Donovan H, Dubin H, Baughman R, DeMaria E, Matzel K, Abraham E, Seneff M. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. The Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Sepsis Investigator Group. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1115–1124. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pajkrt D, Camoglio L, Tiel-van Buul M C, de Bruin K, Cutler D L, Affrime M B, Rikken G, van der Poll T, Ten Cate J W, van Deventer S J. Attenuation of proinflammatory response by recombinant human IL-10 in human endotoxemia: effect of timing of recombinant human IL-10 administration. J Immunol. 1997;158:3971–3977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paris M M, Hickey S, Trujillo M, Ahmed A, Olsen K, McCracken G H. The effect of interleukin-10 on meningeal inflammation in experimental bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1239–1246. doi: 10.1086/514118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shoemaker W C, Appel P L, Kram H B, Bishop M H, Abraham E. Sequence of physiologic patterns in surgical septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1876–1889. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steel R G D, Tovrie J H. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biometrical approach. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Poll T, de Waal Malefyt R, Coyle S M, Lowry S F. Antiinflammatory cytokine responses during clinical sepsis and experimental endotoxemia: sequential measurements of plasma soluble interleukin (IL)-1 receptor type II, IL-10, and IL-13. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:118–122. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Poll T, Jansen J, Levi M, Ten Cate H, Ten Cate J, Van Deventer S. Regulation of interleukin 10 release by tumor necrosis factor in humans and chimpanzees. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1985–1988. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van der Poll T, Jansen P M, Montegut W J, Braxton C C, Calvano S E, Stackpole S A, Smith S R, Swanson S W, Hack C E, Lowry S F, Moldawer L. Effects of IL-10 on systemic inflammatory responses during sublethal primate endotoxemia. J Immunol. 1997;158:1971–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Poll T, Marchant A, Buurman W A, Berman L, Keogh C V, Lazarus D D, Nguyen L, Goldman M, Moldawer L L, Lowry S F. Endogenous IL-10 protects mice from death during septic peritonitis. J Immunol. 1995;155:5397–5401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Poll T, Marchant A, Keogh C V, Goldman M, Lowry S F. Interleukin-10 impairs host defense in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Deventer S J, Elson C O, Fedorak R N. Multiple doses of intravenous interleukin 10 in steroid-refractory Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:383–389. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinstein W M, Onderdonk A B, Bartlett J G, Gorbach S L. Experimental intra-abdominal abscesses in rats: development of an experimental model. Infect Immun. 1974;10:1250–1255. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.6.1250-1255.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanetti G, Heumann D, Gerain J, Kohler J, Abbet P, Barras C, Lucas R, Glauser M P, Baumgartner J D. Cytokine production after intravenous or peritoneal Gram-negative bacterial challenge in mice. J Immunol. 1992;148:1890–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]