Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressively neurodegenerative disease without effective treatment. Here, we reported that the levels of expression and enzymatic activity of phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A (PPM1A) were both repressed in brains of AD patient postmortems and 3 × Tg-AD mice, and treatment of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-ePHP-overexpression (OE)-PPM1A for brain-specific PPM1A overexpression or the new discovered PPM1A activator Miltefosine (MF, FDA approved oral anti-leishmanial drug) for PPM1A enzymatic activation improved the AD-like pathology in 3 × Tg-AD mice. The mechanism was intensively investigated by assay against the 3 × Tg-AD mice with brain-specific PPM1A knockdown (KD) through AAV-ePHP-KD-PPM1A injection. MF alleviated neuronal tauopathy involving microglia/neurons crosstalk by both promoting microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers via PPM1A/Nuclear factor-κb (NF-κB)/C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 1 (CX3CR1) signaling and inhibiting neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation via PPM1A/NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3)/tau axis. MF suppressed microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation by both inhibiting NLRP3 transcription via PPM1A/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in priming step and promoting PPM1A binding to NLRP3 to interfere NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in assembly step. Our results have highly addressed that PPM1A activation shows promise as a therapeutic strategy for AD and highlighted the potential of MF in treating this disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, PPM1A, Miltefosine, Tauopathy, NLRP3, CX3CR1

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; Aβ, Amyloid-β; NFTs, Neurofibrillary tangles; CNS, Central nervous system; PPM1A, Phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A; NLRP3, Nod-like receptor protein 3; AAV, Adeno-associated virus; NF-kB, Nuclear factor-κb; CX3CR1, C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 1; GSK3β, Glycogen synthase kinase 3β; CDK5, Cyclin-dependent protein kinase-5; CaMKII, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; PP2, Protein phosphatase 2; MST, Microscale thermophoresis; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; ALP, Alkaline phosphatase; NOR, New object recognition; MWM, Morris water maze; fEPSPs, Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials; PSD95, Postsynaptic density protein 95; SYN, Synaptophysin; Akt, V-akt routine thymoma viral oncogene homolog; DYRK1A, Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase-1A; LTP, Long-term potentiation

Highlights

-

•

Anti-leishmanial drug Miltefosine (MF) as a PPM1A activator effectively improved cognitive impairments in 3 × Tg-AD mice.

-

•

MF promoted microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers through PPM1A/NF-κB/CX3CR1 signaling.

-

•

MF inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation through PPM1A/NLRP3/tau axis.

-

•

Our findings have provided new evidence that PPM1A activation may function potently in the amelioration of AD pathology.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease with clinical hallmarks of progressive cognitive impairment and memory loss, and most of the AD patients are accompanied by personality changes and mental disorders (Mintun et al., 2021). AD kills more people every year than breast cancer, prostate cancer, and essential hypertension combined. Currently, the mortality rate for AD patients has even increased by 16% during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the pathogenesis of AD is too complicated, and there is still a lack of drugs that can cure AD (Chakraborty et al., 2019). Thus, it is of great significance to clarify the pathology of AD for guiding the development of the promising therapeutical strategies and effective drugs against AD.

Hyperphosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau plays a central role in AD progression due to the tight linkage of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) to microtubule disassembly, transport impairment, synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal degeneration (Congdon and Sigurdsson, 2018). Thus, tauopathy is accepted as a promising target for AD treatment, and varied kinds of reagents have been determined to ameliorate cognitive impairment in AD mice by suppressing tau pathology. For example, vaccine-generated phosphorylated tau (p-tau) antibody accelerated p-tau efflux from brain by combining with p-tau in peripheral circulation system (Sun et al., 2021); inhibitors of kinases (glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), cyclin-dependent protein kinase-5 (CDK5), Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), etc.) and activators of phosphatases (protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A), PP2B, PP-1, etc.) suppressed tau hyperphosphorylation, as exemplified by the findings that diaminothiazole improved behavior impairment in AD mice by inhibiting GSK-3β/CDK5 (Zhang et al., 2013), and metformin decreased tau hyperphosphorylation in a PP2A-dependent manner (Kickstein et al., 2010). Moreover, tau hyperphosphorylation and aggregation can be also driven by NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation, which has highly addressed the association of tauopathy with inflammation (Ising et al., 2019).

Microglia belong to the type of brain-resident macrophage cells functioning as the first and main immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS) (Gabande-Rodriguez et al., 2019). As an important component of innate immunity, NLRP3 inflammasome is a key to immune response (Wang et al., 2020) and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation in microglia is tightly implicated in AD pathogenesis (Shi et al., 2020). NLRP3 inflammasome is composed of sensor protein NLRP3, adaptor protein ASC and pro-Caspase-1, while activates with secretion of IL-1β and other inflammatory factors upon sensing different pathogenic microorganisms or danger signals (Davis et al., 2011). IL-1β is a prominent cytokine that is consistently upregulated in AD patients (Shaftel et al., 2008). Notably, intracellular tau can be also released extracellularly forming tau oligomers that are toxic to neighboring cells (Perea et al., 2018), and microglial phagocytosis functions potently in tau oligomers clearance (Perea et al., 2018).

Protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1A (PPM1A; PP2Cα) is a member of PP2C family belonging to Ser/Thr protein phosphatase and expresses widely throughout the CNS (Fagerberg et al., 2014). PPM1A dephosphorylates proteins at post-translational modification stage and participates in multiple biological processes including cell growth (Ofek et al., 2003), immune response (Sun et al., 2009) and metabolism process (Khim et al., 2020), which are all closely related to AD pathology (Calsolaro and Edison, 2016).

Thus, the objective of the current work was to inspect the beneficial effect of PPM1A activation on AD-like pathology (e.g., cognitive impairment, synaptic integrity and plasticity damages, tau pathology and neuroinflammation) in mice with the new discovered PPM1A activator Miltefosine (MF, FDA approved oral anti-leishmanial drug. Fig. 2A) as a probe. The underlying mechanisms were investigated by assay against the 3 × Tg-AD mice with brain-specific PPM1A knockdown by brain-specific injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-ePHP-KD-PPM1A. We reported that either brain-specific overexpression of PPM1A induced by injection of brain-specific AAV-ePHP-overexpression (OE)-PPM1A or treatment with MF ameliorated AD-like pathology in 3 × Tg-AD mice. MF repressed tauopathy by both promoting microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers and inhibiting tau hyperphosphorylation by targeting PPM1A. Our findings have addressed that PPM1A activation shows promise as a new therapeutic strategy for AD and highlighted the potential of MF in treatment of this disease.

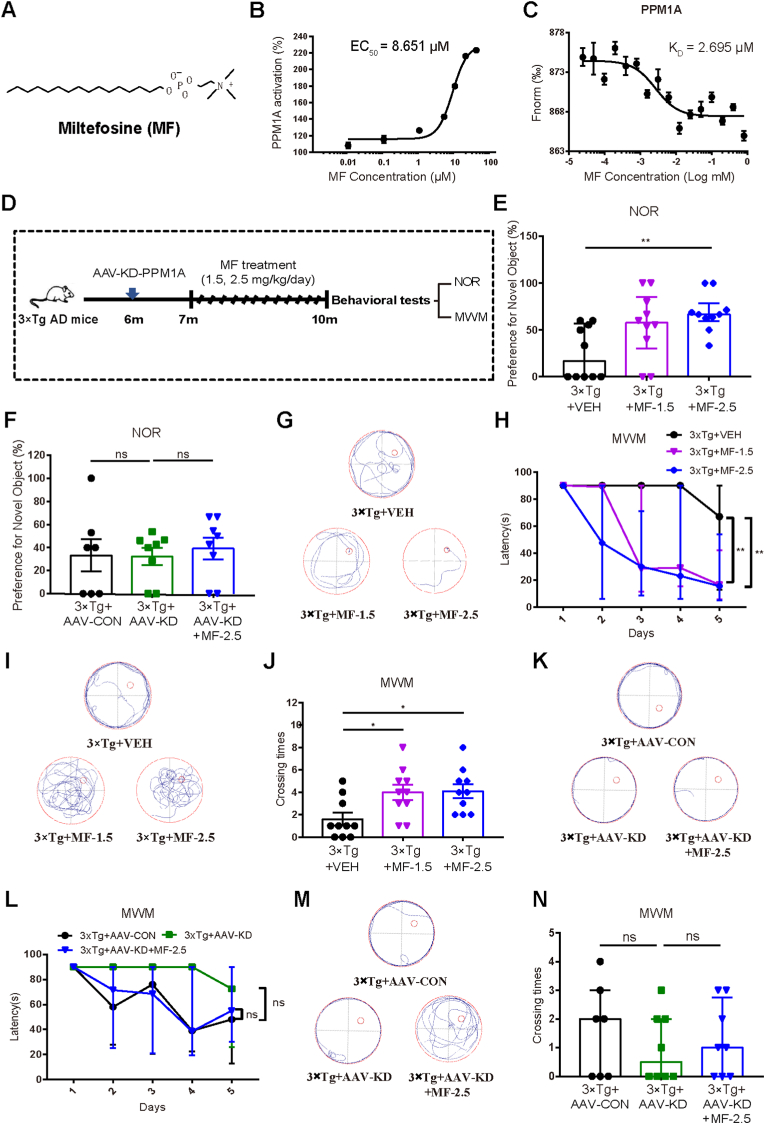

Fig. 2.

MF as a new PPM1A enzymatic activator improved cognitive impairment in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A (A) Chemical structure of MF. (B) Evaluation of MF activation on PPM1A enzyme (EC50 = 8.651 μM). (C) Binding affinity of MF to PPM1A was detected by MST (KD = 2.695 μM). (D) Schedule of mice behavioral tests with MF. (E, F) Analyses of NOR preferences for the 3 × Tg mice treated with (E) VEH, MF-1.5 and MF-2.5 (n = 10 per group) and (F) AAV-CON, AAV-KD and AAV-KD + MF-2.5 (n ≥ 7 per group). E: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. F: One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (G–J) MWM test and quantitative analyses with (G) representative tracing graphs in training trails, (H) escape latency during platform trials (Day 5: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test), (I) representative tracing graphs in probe trails and (J) crossing times of platform in probe trails for the 3 × Tg mice treated with VEH, MF-1.5 and MF-2.5 (One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test) (n = 10 per group). (K-N) MWM test and quantitative analyses with (K) representative tracing graphs in training trails, (L) escape latency during platform trials in MWM test (Day 5: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test), (M) representative tracing graphs in probe trails and (N) crossing times of platform in probe trails for the 3 × Tg mice treated with AAV-CON, AAV-KD and AAV-KD + MF-2.5 (One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test) (n ≥ 7 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. VEH, vehicle; MF-1.5, 1.5 mg/kg/day MF; MF-2.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day of MF. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

All cell culture reagents were purchased from Gibco. Miltefosine (MF, HY-13685), Sanguinarine chloride (HY-N0052A) and pyrrolidine-dithiocarbamate ammonium (HY-18738) were from MCE; Lipopolysaccharides (L8274) and ATP (A2383) were from Sigma-Aldrich; IL-1β ELISA Kit (H002) from NJJC; DAB (ZLI-9018) was from DAKO; Hoechst 33342 (C0030) was from Solarbio; LRR domain of NLRP3 (CSB-EP822275HU2) was from CUSABIO; Adult Brain Dissociation Kit (130-107-677), CD11b (Microglia) MicroBeads (130-093-634) and LS Columns (130-042-401) were from Miltenyi. Purity of all compounds used in the experiments was higher than or equal to 98%. pET24a-PPM1A was available in our own lab. AAV-ePHP-OE-PPM1A (AAV-OE), AAV-ePHP-KD-PPM1A (AAV-KD) and AAV encoding a control ‘scramble’ RNA (AAV-CON) were established by GENE.

2.2. PPM1A enzyme preparation and activity assay

2.2.1. PPM1A enzyme preparation

The assay was performed by the published approach from our lab (Wang et al., 2010). Briefly, hPPM1A was expressed in E. coli with C-terminal 6-His tag and purified using Ni-NTA resin according to the manufacturer's instructions. PPM1A was purified by ÄKTA™ pure system (GE Healthcare) with Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL (GE Healthcare) and verified by immunoblotting assay.

2.2.2. PPM1A enzymatic activity assay

The assay was performed by our published approach (Wang et al., 2010). Briefly, the assay was performed in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 10 mM MnCl2 (Wang et al., 2010). The tested compound was dissolved and diluted by a series of concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM) in the reaction buffer with 5 μg/mL PPM1A and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. Finally, 4 mM pNPP as a phosphatase substrate was added to the reaction system, the enhancement of the compound on PPM1A dephosphorylation was determined by the absorbance change at 410 nm after 30 min using SpectraMax i3X (Molecular devices).

2.3. Microscale thermophoresis (MST) technology-based assay

MST technology-based assay was performed on a Monolith NT.115 instrument (Nano Temper) with Monolith protein labeling kit RED-NHS 2nd generation (MO-L011, Nano Temper) by the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, protein was incubated with 5-fold molar excess of the dye for 30 min and purified by B-column. After labelling, the excess dye was removed. Tween-20 (0.1%) was added to the protein buffer for microscale thermophoresis measurements before experiment. Datasets were collected at 25 °C. In the assay of the dye-labelled PPM1A interaction with LRR domain of NLRP3 (LRR-NLRP3), a concentration series of LRR-NLRP3 were prepared using a 1:1 serial dilution of PPM1A in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. In the assay of the dye-labelled PPM1A interaction with MF, a concentration series of MF were prepared using a 1:1 serial dilution of PPM1A in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. In the assay of the dye-labelled LRR-NLRP3 interaction with MF, a concentration series of MF was prepared using a 1:1 serial dilution of LRR-NLRP3 in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. MST assay was performed at room temperature by the manufacturer's protocol. Data analysis was performed with Nano Temper Analysis software.

2.4. Animals

It was reported that the mice homozygous for all three mutant alleles (3 × Tg-AD; homozygous for the Psen1 mutation and homozygous for the co-injected APPSwe and tauP301L transgenes (Tg(APPSwe, tauP301L)1Lfa)) have a series of typical similarities to human AD patients (e.g., amyloid-β (Aβ) plaque deposition and NFTs, synaptic density decreases before neurodegeneration, and memory declines before Aβ plaque deposition and NFTs) and their spatial working memory begins to impair at the age of 6–7 month (Oddo et al., 2003; Swaab et al., 2021). Thus, 3 × Tg-AD mice were chosen as the AD model mice for the current study.

2.5. Preparation of the 3 × Tg mice with brain-specific PPM1A overexpression

According to the published report (Cocco et al., 2020), 3-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice exhibited no impairments on synaptic plasticity and memory, while 7-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice have deficits in synaptic plasticity and cognitive capability in the brain. Accordingly, 3-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice were used as “control group” (Control) and 7-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice (abbreviated as 3 × Tg mice, if not specified hereafter) were used as AD mice in the related assays.

The 3 × Tg mice with brain-specific PPM1A overexpression were obtained by injecting brain-specific AAV-ePHP-OE-PPM1A (AAV-OE) through tail vein. The experimental animals were totally set to three groups: Control mice (n = 13) injected with negative control vector served as the first group (Control + AAV-CON); 3 × Tg mice (n = 13) injected with negative control vector served as the second group (3 × Tg + AAV-CON). 3 × Tg mice (n = 13) injected with AAV-OE served as the third group (3 × Tg + AAV-OE). After a month and a half, New object recognition (NOR) and Morris water maze (MWM) tests were performed to evaluate the cognitive abilities of mice.

2.6. MF administration

According to the published reports, the median lethal dose (LD50) of MF by intragastric administration in rat is 246 mg/kg (Witschel et al., 2012), equal to 17720 mg/kg in mice by body surface area approach (Bussi and Morisetti, 2005). Besides, in the preliminary experiments, MF efficiently improved memory impairment at 2.5 mg/kg/day (data not shown), much less than the toxic dose. Thus, we selected MF at 1.5 and 2.5 mg/kg/day for the animal related assays in our current work.

The 3 × Tg-AD mice with brain-specific PPM1A knockdown (KD) in the brain was obtained by injecting brain-specific AAV-ePHP-KD-PPM1A (5′ to 3’(RNA)-GCA GAT AGA AGC GGG TCAA) (AAV-KD) through tail vein at the age of six months. MF was dissolved in 0.5% DMSO, 0.5% tween-80 and 99% saline solution, and the mice were treated with MF by intraperitoneal injection. The experimental mice were totally set to six groups (n = 15 per group). The 3 × Tg mice in the first group were treated with vehicle (3 × Tg + VEH), in the second were treated with MF (1.5 mg/kg/day) (3 × Tg + MF-1.5), in the third were treated with MF (2.5 mg/kg/day) (3 × Tg + MF-2.5), in the fourth were injected with both AAV negative control vector and vehicle (3 × Tg + AAV-CON), in the fifth were treated with both AAV-KD and vehicle (3 × Tg + AAV-KD), and in the sixth were treated with both AAV-KD and MF (2.5 mg/kg/day) (3 × Tg + AAV-KD + MF-2.5). After 90-day administration, NOR and MWM tests were performed.

In addition, we measured the serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of the 3 × Tg mice after chronic treatment with MF for 90 days. As shown in Fig. S1A and B, MF treatment had no effects on AST, ALT and ALP levels in 3 × Tg mice. These results thereby suggested that MF (1.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day) rendered no apparent effects on liver functions of 3 × Tg mice.

2.7. Behavioral tests

2.7.1. NOR test

The test was performed according to the published approach (Lueptow, 2017) in an open-field apparatus (32 × 32 × 20 cm3). The task consisted of 4 sequential daily trials. During the habituation trial (day 1 and 2), mice were allowed to explore the open field for 15 min. During the acquisition trial (day 3), mice were exposed to two identical objects positioned near the two corners and allowed to freely explore space for 5 min. Finally, the memory test was performed 16 h later (day 4): a novel object was introduced, and mice were allowed to explore for 5 min during the test phase. The apparatus and objects were cleaned with ethanol (70%) before use and between each animal test. NOR (%) was calculated for each mouse.

2.7.2. MWM test

The assay was performed as previously described (Lv et al., 2020). Briefly, after over 5 consecutive days with three trials per day, mice were trained to use a variety of visual cues located on the pool wall to find a hidden submerged white platform in a circular pool (120 cm in diameter, 50 cm deep) filled with milk-tinted water. In each trial, each mouse was given 90 s to find the hidden platform. If the mouse found the platform within that time, the animal was allowed to rest on the platform for 15 s. If the mouse failed to find the platform within 90 s, the animal was manually placed on the platform and allowed to remain there for 15s. On day 6, after training trials, a probe trial was performed by removing the platform, and mice were allowed to swim for 90s in search of it. All data were collected for mouse performance analysis. For data analysis, the pool was divided into four equal quadrants formed by imaging lines, which intersected in the center of the pool at right angles called north, south, east, and west.

2.8. Long-term potentiation (LTP)

Briefly, after the mice were anesthetized with 10% chloral hydrate, the whole brains were immediately isolated and soaked in ice-cold ACSF supplemented in 95% O2/5% CO2. Brain slices (350 μm) were then prepared using a vibratome (frequency, 80 Hz; speed, 0.45 mm/s) and incubated in oxygenated ACSF for 0.5 h at 32 °C. Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in dentate gyrus (DG) of hippocampus. The baseline in resting state was recorded for 10 min, and LTP was induced by three trains of high-frequency stimulation. The field potential response after stimulating was recorded for 60 min. The magnitude of LTP was calculated and quantified by the average slope of the fEPSP over 60 min after LTP induction.

2.9. Golgi-Cox staining

The morphology of dendritic spines in brain of the mice was analyzed using a FD Rapid Golgi Stain Kit (FD Neuro technologies, Elliot City, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after being anesthetized, mouse brains were quickly removed and washed with ddH2O. Subsequently, the brains were submerged in the mixture of solution A and B for 2 weeks at room temperature in the dark. The impregnation solution was replaced on the next day. Samples were removed to solution C and incubated for 4 days at room temperature in the dark, and then sectioned into 100 μm sections by a cryostat microtome and placed onto microscope slides. Sections were washed three times and placed in a mixture composed of solution D, solution E and ddH2O, followed by two rinses in ddH2O for 4 min. The slides were dehydrated in 70%, 80%, 90% and 100% alcohol. Finally, xylene solution was dropped to the sections and incubated for 10 min, and the sections were cleared and slipcovered. Images for neurons were obtained with an automated upright microscope (Leica).

2.10. Cell culture

2.10.1. Primary microglia

Primary microglia were cultured from wild-type C57BL/6 mice on postnatal day 1. Briefly, the brain tissues were minced into small pieces, digested with 0.25% trypsin (Gibco) and 200 U/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature, while digestion was stopped by adding 4 mL DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were plated in T75 cell culture flasks (Corning) pre-coated with polyD-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). After 7 days, the microglia were dissociated by shaking the flasks several times, harvested by centrifugation (300g × 10 min), followed by dilution at a density of 50,000 cells/mL on polyD-lysine coated cell culture plates. Cultures were kept in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.10.2. Primary neuronal cells

Primary neuronal cells were separated from embryonic mouse brains (embryonic d 16 to 18). Briefly, the brain tissues were minced into small pieces, digested with D-Hank's buffer containing 0.125% trypsin (Gibco) and 200 U/mL DNase (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, while digestion was stopped by adding 4 mL DMEM (Gibco) MEM with 10% FBS. Cell fluid was diluted at a density of 600,000 cells/mL on polyD-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated cell culture plates. After 6 h, the medium was replaced by a Neurobasal medium (Gibco) supplemented with 2% B27, 0.5 mM L-glutamine and 50 U/μL penicillin-streptomycin. Cultures were kept in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.11. LPS/ATP assay

As NLRP3 inflammasome activation-induced neuroinflammation is tightly implicated in AD pathology (Heneka et al., 2013), we focused on NLRP3 inflammasome related study in primary microglia. It was noted that NLRP3 inflammasome is achieved by two sequential steps, termed as priming and assembly, respectively (He et al., 2016a). Specifically, activation of Toll-like receptor 4 by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) provides the priming signal (Munoz-Planillo et al., 2013) and further stimulation by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) triggers the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome (Hornung et al., 2008). Thus, we used LPS plus ATP (LPS/ATP) as stimuli to activate NLRP3 inflammasome in the current study according to the published reports (He et al., 2016a).

In LPS/ATP assay, the primary microglia were primed with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h, then stimulated with ATP (3 mM) for 30 min. After stimulation, cells were lysed and analyzed by RT-PCR and western blot assays, and medium supernatants were analyzed by ELISA.

2.12. Immunohistochemistry

Brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, rinsed in PBS and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose before freezing in a 2:1 mixture of 30% sucrose and optimal cutting temperature compound.

2.12.1. AT8 staining

For AT8 immunostaining, antigen retrieval was performed by microwave heating of the sections in sodium citrate buffer (10 mM trisodium citrate, 0.5% Tween-20 in H2O, pH 6.0) for 10 min, followed by incubation with 3% H2O2 for 5 min to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were blocked with 2% goat serum in 1 × TBS with 0.25% Triton-X100 (TBS-X) for 30 min, followed by incubation with a biotinylated primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then labelled with a Dako HRP-linked goat anti-mouse IgG antibody for 1h at room temperature and developed with a Dako DAB chromogen kit. The staining images were captured using Leica DM4B microscope system.

2.12.2. Immunofluorescence staining

For detecting the protein levels of Ibal, NLRP3, NF-κB, tau, phosphorylated tau, VAMP2, PPM1A and ASC, the slides/cells were incubated in PBST (5% Triton X-100, Beyotime) for 15 min and in 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Then, the slides/cells were washed with PBS by three times and incubated with fluorescent secondary detection antibodies for 1h, followed by incubation with Hoechst 33342 for 10 min. The slides/cells were observed by using a Leica TCS SP8 microscope system and the images were analyzed by the Image J software.

All antibodies were listed with specific catalog numbers and vendors (Table S2).

2.13. Adult mouse microglia isolation

Adult mice were anesthetized and perfused with ice-cold saline solution. The isolated forebrains were cut into small pieces and dissociated enzymatically and mechanically using a papain-based neural dissociation kit with a gentle MACS dissociator system (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Segal and Giger, 2016). CD11b+ MicroBeads (130-093-634; Miltenyi Biotec) were used to identify and select microglia cells according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.14. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from primary microglia or brain tissues using TRIZOL Reagent (Invitrogen) by the protocols of commercial kits. Complementary DNA synthesis was performed with oligo-dT primers based on the instruction of reverse-PCR kit (TAKARA Bio). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green PCR core reagent kit (TAKARA Bio) for mRNA quantity detection. Primer sequences used in the experiments were listed in Table S3.

2.15. Western blot

For cell samples, primary microglia were lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime) containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Thermo Scientific) on ice for 20 min.

For tissue samples, brain tissues were homogenized with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails and the homogenates were kept on ice for 30 min. After centrifuging at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime). Proteins were mixed with 2 × SDS-PAGE sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and boiled for 15 min at 99 °C.

Cell or tissue extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filter membrane (GE Healthcare). After incubation with corresponding antibodies overnight, the blots were visualized using Dura detection system (Bio-Red). All antibodies have been listed with specific catalog number and vendor (Table S2).

2.16. ELISA assay for IL-1β

The supernatants were collected from primary microglia and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. IL-1β level was detected using mouse IL-1β ELISA kit (Novus Biologicals) according to the manufacturer's instructions by SpectraMax i3X (Molecular devices).

2.17. Co-immunoprecipitation

Primary microglia were collected and lysed in NP-40 buffer on ice for 30 min. Proteins in the supernatants were immunoprecipitated with specific primary antibodies (NLRP3, dilution 1:200) overnight, followed by incubation with Protein G agarose for 4h at 4 °C. The obtained protein complexes were prepared for western blot assay.

2.18. Statistical analysis

All cell experiments were performed in triplicate to obtain three independently experimental date. Each study was completed with listed number of samples in figure legends. Normal distribution was analyzed via GraphPad Prism 7 software, D'Agootino-Pearson, Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogoov-Smirnov were used to test whether the data conform to the normal distribution. If p > 0.05, statistical analysis between two groups was carried out using the t-test, among multiple groups was carried out using the one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test, or using the two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The details are as follows: Fig. 1 C, 6 O, S2 B, S3 B and S5 C were analyzed by t-test; Fig. 1 (E, I, M and O), 2 (F and J), 3 (B, D, F, H, J and L), 4 (B, F, H, J, L and N), 5 (B, I, K and M), 6 (B, E, G and H), S1 C, S4 B, S6 A, S8 C, E and G, S9 (B and D) and S10 B were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test; Fig. 5 (E and F), 6 (I, K, L and M), S6 C and S7 B were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, data are represented as mean (standard error of mean (SEM)). If p < 0.05, Non-parametric tests were applied for statistical analysis, in that Mann Whitney test was used between two groups and Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn's multiple comparisons tests were applied among multiple groups. The details are as follows: Fig. 1 A, S3 C and S5 B were analyzed by Non-parametric Mann Whitney test; Fig. 1 (G and K), 2 (E, H, L and N), 4 (C, E and L (ASC/GAPDH)), 5 C, 6 (A and C), S1 (A and B), S3 C, S8 C and S10 (A, D, F, H and J) were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test, data are represented as median (interquartile range (IQR)).

Fig. 1.

PPM1A overexpression improved cognitive and synaptic impairments in 3 × Tg mice (A) qRT-PCR assay and (B, C) western blot assay with quantitation results of PPM1A mRNA level, and PPM1A and p-Smad3 levels in brains of 3 × Tg and wild type (WT) mice (n = 8/4 per group for qRT-PCR or western blot assay). A: Mann Whitney test. B: t-test. (D) Schedule of animal treatments and behavior tests. (E) Analysis of Novel object recognition (NOR) preference for mice (n = 10 per group). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (F-I) Morris Water Maze (MWM) test and quantitative data analyses for mice (n = 10 per group). (F) Representative tracing graphs in training trails for mice. (G) Escape latency during platform trials in MWM test for mice. Day 5: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. (H, I) Representative tracing graphs and crossing times of platform in probe trails for mice. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (J, K) LTP in hippocampal DG region was induced by high-frequency stimulation with (J) averaged slopes of baseline normalized fEPSP and (K) quantification of mean fEPSP slopes during the last 10 min of the recording after LTP induction for mice. n = 9 slices from three mice per group. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. (L) Western blot assay with (M) its quantification results for PSD95 and synaptophysin (SYN) levels in cortex of mice (n = 4 per group). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (N) Spines of hippocampal neurons in mice were measured by Golgi-Cox staining assay (n = 6 per group). Scalebar: 500 μm, 100 μm, 4 μm respectively. (O) Quantification results for (N). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. For assays from (E) to (O): The mice included Control + AAV-CON, 3 × Tg + AAV-CON and 3 × Tg + AAV-OE mice as indicated in the corresponding figures. GAPDH was used as loading control in western blot and qRT-PCR assays. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4.

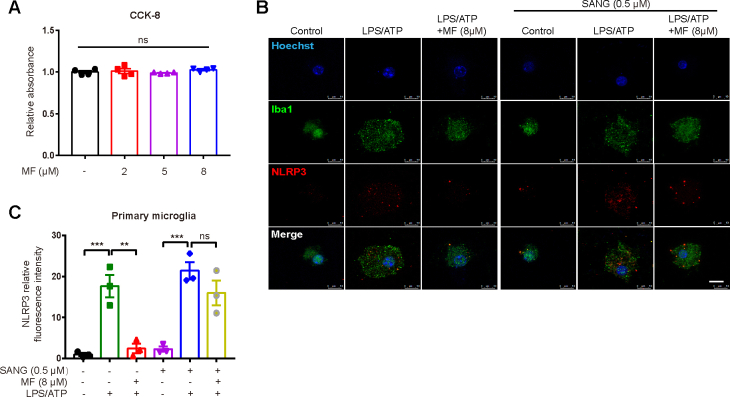

Fig. 5.

MF inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation through PPM1A/NLRP3/tau axis. (A–C) Primary microglia were pretreated with varied concentrations of MF (2, 5, 8 μM) for 1 h and incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h, and then stimulated with ATP (3 mM) for 30 min. (A) NLRP3, ASC, Casp1 p20 and Caspase-1 proteins from cell extracts were analyzed by western blot assay. (B) Quantification for (A). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (C) IL-1β from medium supernatants was analyzed by ELISA. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. (D–F) Primary microglia were treated with SANG (0.5 μM) for 3 h, followed by treatment of MF (8 μM) 1 h, and then primed by LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6h and stimulated with ATP (3 mM) for 30 min. (D, E) NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and Caspase-1 proteins from cell extracts were analyzed by western blot assay. (E) Quantification for (D). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. (F) IL-1β from medium supernatants was analyzed by ELISA. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. (G) Schematic illustration showing the microglial conditioned medium (MCM) based assay. (H) Immunofluorescence assay with (I) its quantification results of AT8 (green) in primary neurons (red) incubated with MCM from primary microglia. Scale bars: 250 μm; 100 μm. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (J) Western blot assay with (K) its quantification results of p199-tau, p231-tau, p396-tau, tau, p216-GSK3β, GSK3β, p-CAMKII and CAMKII protein levels in primary neurons incubated with MCM from primary microglia. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (L) Western blot assay with (M) its quantification results of p199-tau, p231-tau, p396-tau, tau, p216-GSK3β, GSK3β, p-CAMKII and CAMKII protein levels in primary neurons. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. (N) Primary microglia were pretreated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h and then stimulated with ATP (3 mM). Primary neurons were pretreated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h, and then stimulated with ATP (3 mM). NLRP3 level was analyzed by western blot assay. GAPDH was used as loading control in western blot assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4. . (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3. Results

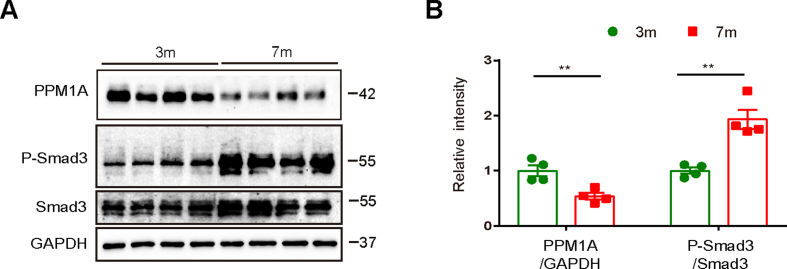

3.1. PPM1A level was repressed in brains of AD patient postmortems and 3 × Tg mice

GSE36980, GSE28146 and GSE48350 from pubic Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database were used to examine PPM1A gene levels in brains of AD and non-AD individuals, and the results indicated that PPM1A gene level was repressed in AD individuals (Table S1). qRT-PCR and western blot assay results demonstrated that PPM1A mRNA and protein levels in brains of 7-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice (3 × Tg mice) were both repressed compared with those of wild type (WT) mice (Fig. 1A–C).

Smad family member 3 (Smad3) is the specific substrate of PPM1A (Lin et al., 2006) and western blot results (Fig. 1B and C) indicated that phosphorylated Smad3 (p-Smad3) level was increased in brains of 3 × Tg mice compared with that in WT mice, indicative of the repressed PPM1A enzymatic activity in 3 × Tg mice.

Here, we also found that 7-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice showed decreased PPM1A and increased p-Smad3 protein levels compared with 3-month-old 3 × Tg-AD mice (Figs. S2A and B).

These results suggested the possibility that PPM1A was involved in AD progression.

3.2. PPM1A overexpression improved cognitive impairment in 3 × Tg mice

To evaluate the beneficial effect of PPM1A overexpression on memory-related behaviors of 3 × Tg mice, the mice with brain-specific PPM1A overexpression were applied through injection of brain-specific AAV-OE-PPM1A (AAV-OE) (Fig.1AD). Western blot results indicated that the 3 × Tg mice injected with AAV-OE (3 × Tg + AAV-OE) exhibited increased PPM1A and decreased p-Smad3 levels compared with the 3 × Tg mice injected with AAV-CON (3 × Tg + AAV-CON) (Figs. S3A and B).

3.2.1. NOR test

This test was to evaluate the short-term working memory of mice. As indicated in Fig. 1E, the 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice spent less time around new objects compared with Control + AAV-CON mice, and 3 × Tg + AAV-OE mice spent more time on new objects compared with 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice.

3.2.2. MWM test

This test was to assess spatial learning and long-term memory of mice. The results indicated that in 5-day training trails (Fig. 1F and G), the path lengths and escape latencies to find the platform were prolonged for 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice compared with those for Control + AAV-CON mice and shortened for 3 × Tg + AAV-OE mice compared with those for 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice. In probe trial assay (Fig. 1H and I), the frequency to cross the hidden location of the platform was lower and the time spent in platform quadrant was less for 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice compared with those for Control + AAV-CON mice. In contrast, 3 × Tg + AAV-OE mice exhibited higher “frequency” and more “time spent” in probe trial assays compared with 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice.

3.3. PPM1A overexpression ameliorated synaptic impairment in 3 × Tg mice

Given the tight association of synaptic functions with cognition, regulation of PPM1A overexpression against hippocampal synaptic plasticity and integrity was inspected in 3 × Tg mice.

3.3.1. PPM1A overexpression ameliorated LTP in 3 × Tg mice

LTP of synaptic transmission is commonly applied to detect synaptic plasticity (He et al., 2016b). As indicated in Fig. 1J and K, LTP was impaired as indicated by the suppressed fEPSP slope in 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice compared with that in Control + AAV-CON mice, and AAV-OE injection ameliorated LTP impairment in 3 × Tg mice.

3.3.2. PPM1A overexpression upregulated synapse-associated proteins in 3 × Tg mice

Synapse-associated proteins postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) and synaptophysin (SYN) are crucial for neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity (Valtorta et al., 2004). Western blot results indicated that both proteins were reduced in 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice compared with those in Control + AAV-CON, and AAV-OE injection increased the levels of these two proteins in 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 1L and M).

3.3.3. PPM1A overexpression ameliorated synaptic integrity impairment in 3 × Tg mice

Golgi-Cox staining assay was performed to evaluate synapse integrity of hippocampal tissues of mice (Du, 2019). As shown in Fig. 1N and O, the spine density of basal dendrites was reduced in 3 × Tg + AAV-CON mice compared with that in Control + AAV-CON mice, and AAV-OE injection improved the spine density deficiency in 3 × Tg mice.

3.4. MF was a direct PPM1A enzymatic activator

Since we have determined that brain-specific PPM1A overexpression improved cognitive impairment and synaptic deficiency in 3 × Tg mice, we next tried to find PPM1A enzymatic activator and investigate whether it could also ameliorate AD-like pathology in mice.

3.4.1. MF enhanced PPM1A enzymatic activity

In the assay to find the activator of PPM1A enzyme, the lab constructed platform (Wang et al., 2010) was used to screen the lab in-house FDA approved drug library, and anti-leishmanial drug MF (Fig. 2A) was determined to activate PPM1A activity by EC50 of 8.651 μM (Fig. 2B). Notably, MF had no effects on PPM1A expression but reduced p-Smad3 in 3 × Tg mice (Figs. S4A and B), indicating that MF promoted PPM1A enzymatic activity.

3.4.2. MF bound to PPM1A

Additionally, MST assay results also verified the binding affinity of MF to PPM1A by dissociation constant (KD) of 2.695 μM (Fig. 2C), indicating that MF was a direct PPM1A enzymatic activator.

3.5. MF ameliorated cognitive deficits in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

In the assay, either MF treatment (1.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day; intraperitoneal injection) or PPM1A knockdown in the brain by injecting brain-specific AAV-KD-PPM1A (AAV-KD) through tail vein was performed (Fig. 2D). Western blot results indicated that the 3 × Tg mice treated with AAV-KD showed decreased PPM1A and increased p-Smad3 protein levels compared with those treated with AAV-CON (Figs. S5A and B).

3.5.1. NOR test

MF-treated 3 × Tg mice spent more time on new objects compared with vehicle-treated 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 2E). Notably, MF rendered no influences on the time spent on new objects in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 2F). These results thus demonstrated that MF prolonged the time spent on new objects in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A.

3.5.2. MWM test

The results indicated that in 5-day training trails (Fig. 2G and H), the path lengths and escape latencies to find the platform were shortened in MF-treated 3 × Tg mice compared with those in vehicle-treated 3 × Tg mice. In probe trial assay (Fig. 2I and J), higher frequency to cross the hidden location of the platform and more time spent in platform quadrant were found for MF-treated 3 × Tg mice compared with those for vehicle-treated 3 × Tg mice. Notably, MF had no impacts on the path lengths and escape latencies to find the platform (Fig. 2K and L), or the frequency to cross the hidden location of the platform (Fig. 2M), or the time spent in platform quadrant (Fig. 2N) in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice. These results thus verified that MF improved spatial learning and long-term memory impairments of 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A.

3.6. MF ameliorated synaptic impairment in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

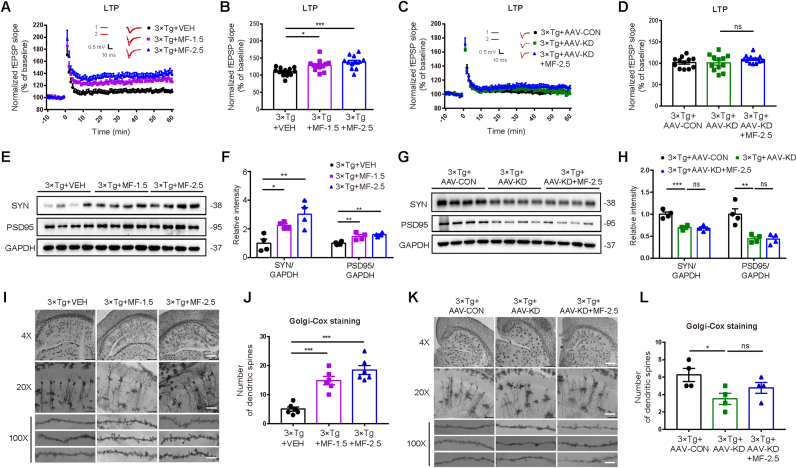

3.6.1. MF ameliorated LTP suppression in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

The results indicated that MF improved LTP suppression at DG synapses in the hippocampus of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 3A and B). Notably, MF had no impacts on LTP in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

MF ameliorated synaptic impairment in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A (A-D) LTP in hippocampal DG region was induced by high-frequency stimulation (n = 12 slices from four mice per group) for 3 × Tg mice treated by (A, B) VEH or MF-1.5/2.5 and (C, D) AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5. (A, C) Averaged slopes of baseline normalized fEPSP and (B, D) quantification of mean fEPSP slopes during the last 10 min of the recording after LTP induction. (E–H) Levels of synapse-associated proteins SYN and PSD95 of the cortex were detected by western blot assay (n = 4 per group) in (E, F) 3 × Tg mice treated by VEH or MF-1.5/2.5 and (G, H) AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5. (F, H) Quantification results for (E, G). (I–L) Spines of hippocampal neurons in mice were measured by Golgi-Cox staining assay. Scalebar: 500 μm, 100 μm, 4 μm respectively. (I, J) for VEH or MF-1.5/2.5-treated 3 × Tg mice (n = 6 per group). (K, L) for AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 injected 3 × Tg mice (n = 4 per group). (J, L) Quantification results for (I, K). GAPDH was used as loading control in western blot assay. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. VEH, vehicle; MF-1.5, 1.5 mg/kg/day MF; MF-2.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day MF. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4.

3.6.2. MF enhanced synapse-associated proteins in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

Western blot results indicated that MF promoted the levels of both synapse-associated proteins PSD95 and SYN of the cerebral cortex in 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 3E and F). Notably, AAV-KD injection downregulated these two proteins in 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on either of these two proteins in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 3G and H).

3.6.3. MF ameliorated the dendrites deficiency in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

Golgi-Cox staining assay was performed against the hippocampal neurons in mice, and the results indicated that MF ameliorated the dendrites and dendritic spines deficiencies in 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 3I and J). Notably, AAV-KD injection downregulated the dendrites and dendritic spines in 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on dendrites and dendritic spines in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 3K and L).

3.7. MF inhibited neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation involving microglia/neurons crosstalk through PPM1A/NLRP3/tau axis in 3 × Tg mice

3.7.1. MF inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A

Tau hyperphosphorylation at sites of Ser202/205, Ser199, Ser396, Thr231 and Thr217 is tightly associated with microtubule assembly impairment (Liu et al., 2007; Mattsson-Carlgren et al., 2020), and GSK-3β and CaMKII are mainly responsible for tau hyperphosphorylation in AD-like pathology (Turab Naqvi et al., 2020).

AT8 staining assay result indicated that MF reduced AT8 positive spots (tau phosphorylation at sites of Ser202 and Thr205) in both cerebral cortex and hippocampus of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 4A–C). Notably, AAV-KD injection increased AT8 positive spots in 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on AT8 positive spots in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 4D–F).

Fig. 4.

MF inhibited tau hyperphosphorylation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by targeting PPM1A. (A–F) Levels of p-tau at sites Ser202 and Thr205 in hippocampus and cortex of mice were detected by AT8 staining assay (n = 6 per group). Scale bars: hippocampus, 200 μm; cortex, 100 μm. (A–C) for VEH or MF-1.5/2.5-treated 3 × Tg mice. (D–F) for AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 injected 3 × Tg mice. (A, D) Representative images; (B-C, E-F) Quantification results for (A, D). B, F: One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test; C, E: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. (G–J) Levels of p199-tau, p217-tau, p231-tau, p396-tau, p216-GSK3β and p-CAMKII in the cortex of mice were detected by western blot (n = 4 per group). (G, H) for VEH or MF-1.5/2.5-treated 3 × Tg mice. (I, J) for AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 injected 3 × Tg mice. (H, J) Quantification results for (G, I). H, J: One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (K-N) Levels of NLRP3, ASC, IL-1β, Casp1 p20 and Casp1 in the cortex of the mice were detected by western blot (n = 4 per group). (K, L) for VEH or MF-1.5/2.5-treated 3 × Tg mice. (M, N) for AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 injected 3 × Tg mice. (L, N) Quantification results for (K, M). Only the ASC/GAPDH figure used Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test, the others were one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. GAPDH was used as loading control in Western blot assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. VEH, vehicle; MF-1.5, 1.5 mg/kg/day of MF; MF-2.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day of MF. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4.

In addition, western blot results also demonstrated that MF suppressed tau hyperphosphorylation at sites of Ser199, Thr231, Ser396 and Thr217, and downregulated p216-GSK3β and p286-CAMKII in the cerebral cortex of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 4G and H). Notably, AAV-KD injection increased tau hyperphosphorylation at the above-mentioned sites or either kinase in 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on tau hyperphosphorylation at any sites or either kinase in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 4I and J).

3.7.2. MF repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in 3 × Tg mice

NLRP3 inflammasome activation-induced neuroinflammation is tightly implicated in AD pathology (Heneka et al., 2013). Western blot results indicated that MF had no effects on ASC expression, but decreased the levels of NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and IL-1β in the cortex of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 4K and L). Notably, western blot results demonstrated that AAV-KD injection upregulated the levels of NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and IL-1β in the cortex of 3 × Tg mice, and MF rendered no influences on any of these proteins in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 4M and N). All results indicated that MF repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in 3 × Tg mice by targeting PPM1A.

3.7.3. MF attenuated neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation involving microglia/neurons crosstalk through NLRP3/tau axis

Given that microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation (Ising et al., 2019), we inspected the potential regulation of MF against NLRP3/tau axis between microglia and neurons by microglial conditioned medium based assay (Ising et al., 2019).

As indicated in Fig. 5A–C, MF had no effects on ASC protein but antagonized the LPS/ATP-increased NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and IL-1β in primary microglia, while CCK-8 assay results demonstrated that MF (2, 5, 8 μM) rendered no influences on microglial viability (Fig. S6A). Next, PPM1A specific antagonist Sanguinarine (SANG) (Nobuhiro ABURAI, 2010) was applied to verify whether MF inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation by targeting PPM1A. Western blot (Fig. 5D and E), ELISA (Fig. 5F) and immunofluorescence (Figs. S6B and C) results demonstrated that SANG deprived MF of its antagonistic activity against the LPS/ATP-induced increases of NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and IL-1β in primary microglia. Thus, all results indicated that MF repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary microglia by targeting PPM1A.

Next, the conditioned medium was collected from primary microglia and subsequently added to primary neuronal cultures (Fig. 5G). Immunofluorescence (Fig. 5H and I) and western blot (Fig. 5J and K) results demonstrated that the LPS/ATP-treated conditioned medium resulted in increased levels of p202/205/199/231/396-tau, p216-GSK3β and p286-CaMKIIα, while MF treatment in the LPS/ATP-treated conditioned medium caused antagonistic effects on all those proteins in primary neurons. Notably, MF had no effects on the levels of p-tau or GSK3β/CaMKIIα in primary neurons (Fig. 5L and M).

Moreover, to exclude the possibility that LPS/ATP in the conditioned medium might stimulate neurons to produce NLRP3, we detected NLRP3 level in both primary microglia and primary neurons. Western blot result indicated that NLRP3 level in primary neurons was much lower than that in primary microglia with treatment of LPS/ATP (Fig. 5N).

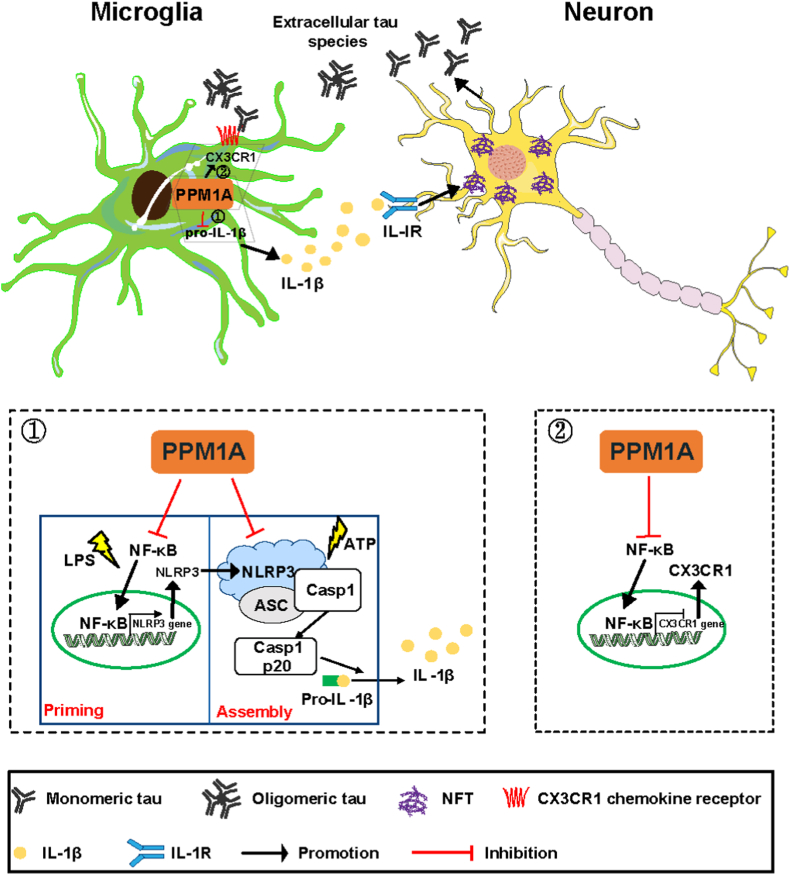

3.8. MF suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in both priming and assembly processes in microglia by targeting PPM1A

3.8.1. MF reduced NLRP3 transcription in priming process through PPM1A/NF-κB signaling

qRT-PCR results demonstrated that MF decreased NLRP3 mRNA level in either cerebral cortex (Fig. 6A) or microglia (Fig. 6B) isolated from brains of 3 × Tg mice. Notably, AAV-KD injection upregulated the mRNA level of NLRP3 in the cortex of 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on NLRP3 mRNA level of cerebral cortex in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 6C). These results demonstrated that MF suppressed NLRP3 transcription by targeting PPM1A.

Fig. 6.

MF suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in both the priming and assembly steps in primary microglia by targeting PPM1A. (A–C) mRNA level of NLRP3 was detected by qRT-PCR assay in (A) brains and (B) microglia from 3 × Tg mice treated by VEH or MF-1.5/2.5, and in (C) brains from 3 × Tg mice treated by AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 (n = 6 per group). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. A: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test; B: One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test; C: Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test. (D–G) Nuclear translocation of NF-κB in microglia from mice was detected by immunofluorescence assay (n = 6 per group). Scale bars: 10 μm. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. (D, E) for VEH or MF-1.5/2.5-treated 3 × Tg mice. (F, G) for AAV-CON, AAV-KD or AAV-KD + MF-2.5 injected 3 × Tg mice. (D, F) Representative images; (E, G) quantification results for (A, F). (H) Primary microglia were pretreated with varied concentrations of MF (2, 5, 8 μM) for 1 h and incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h, and then stimulated with ATP (3 mM) for 30 min. NLRP3 mRNA level was detected by qRT-PCR assay. One-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc test. (I–M) Primary microglia were treated with NF-κB specific antagonist Ammonium Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC) for 1 h, followed by treatment of MF (8 μM) 1 h, and then primed by LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6h and stimulated with ATP (3 mM) for 30 min. (I) qRT-PCR analysis for NLRP3 mRNA level in primary microglia. (J–L) Western blot assay was performed to detect the protein levels of NLRP3, Casp1 p20 and Casp1 in cell extracts, and (M) ELISA assay was performed to analyze IL-1β maturation in supernatants. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. (N, O) Immunofluorescent histochemical staining for Hoechst, NLRP3, ASC and PPM1A in primary microglia. Scale bar: 10 μm. Two-sample t-test. (P) Cell lysates (input) were immunoprecipitated with anti-NLRP3 antibody and western blot results indicated the interaction of NLRP3 with PPM1A. (Q–S) MST based binding affinity assay of (Q) PPM1A to LRR-NLRP3 (KD = 0.882 μM) (R) MF to PPM1A/LRR-NLRP3 (0.383 μM) and (S) MF to LRR-NLRP3 (Unbound). GAPDH was used as loading control in western blot assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. VEH, vehicle; MF-1.5, 1.5 mg/kg/day MF; MF-2.5, 2.5 mg/kg/day MF. Detailed statistical results were included in Supplemental Table 4.

NF-κB is a critical transcription factor for NLRP3 regulation (Afonina et al., 2017) and PPM1A is a direct regulator of NF-κB (Sun et al., 2009), and immunofluorescence assay results indicated that MF reduced NF-κB localization in nucleus of the microglia isolated from brains of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. 6D and E). Notably, AAV-KD injection upregulated NF-κB localization in nucleus of the microglia from brains of 3 × Tg mice, and MF had no impacts on NF-κB localization in nucleus of the microglia from the brains of 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. 6F and G). qRT-PCR result also indicated that MF antagonized the LPS/ATP-increased NLRP3 mRNA level in primary microglia (Fig. 6H). Next, NF-κB specific antagonist ammonium pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC) (Nemeth et al., 2003) was applied in the assay against primary microglia, and the results indicated that PDTC reduced p-NF-κB level (Figs. S7A and B) and deprived MF of its capability in antagonizing LPS/ATP-increased NLRP3 mRNA (Fig. 6I) and protein levels (Fig. 6J and K). All results implied that NF-κB signaling was required for MF regulation against NLRP3 transcription.

3.8.2. MF repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in assembly process by promoting PPM1A binding to LRR domain of NLRP3

Notably, PDTC failed to completely deprive MF of its antagonistic effects on LPS/ATP-induced upregulation of Casp1 p20 and IL-1β in primary microglia (Fig. 6L and M). This result implied that there may exist also other pathway(s) responsible for MF-mediated suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation apart from NF-κB signaling.

Given that assembly process is another vital process for NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Song et al., 2017), and NLRP3 protein has been reported to bind several proteins (Sharif et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2018), we inspected whether PPM1A protein could bind to NLRP3. As expected, immunofluorescence result indicated that PPM1A colocalized with NLRP3 in LPS/ATP-treated primary microglia (Fig. 6N and O), and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay result demonstrated that NLRP3 could pull-down PPM1A in PDTC-treated microglia (PDTC was for elimination of the effect of MF on NLRP3 translocation) (Fig. 6P). Thus, all results indicated PPM1A binding to NLRP3.

Next, considering that NLRP3 has three domains (Leucine-rich repeat (LRR), Pyrin (PYD), NACHT) (Sharif et al., 2019) and active LRR domain is commercially available (CSB-EP822275HU2, CUSABIO), the binding of purified PPM1A to LRR domain of NLRP3 (LRR-NLRP3) was examined by MST assay. The result indicated that PPM1A had a binding affinity to LRR-NLRP3 by KD at 0.882 μM (Fig. 6Q) and MF enhanced PPM1A/LRR-NLRP3 binding (KD = 0.383 μM) (Fig. 6R). Meanwhile, MF itself had no binding affinity to LRR-NLRP3 (Fig. 6S). Thus, all results verified that MF promoted PPM1A binding affinity to LRR-NLRP3.

3.9. MF promoted microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers through PPM1A/NF-κB/CX3CR1 pathway in 3 × Tg mice

Given the high contribution of tau hyperphosphorylation-induced extracellular tau oligomers to AD progression (Bolos et al., 2017), the potential regulation of MF in microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers was also investigated.

Immunofluorescence assay result against the hippocampus of mice indicated that MF promoted colocalization of microglia (red) with tau oligomers (green) in neurons of 3 × Tg mice (Fig. S8A) but had no impacts on such colocalization in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Fig. S8B). These results thus implied that MF promoted microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers by targeting PPM1A.

As chemokine receptor CX3CR1 is key to microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers, and NF-κB activation negatively regulates CX3CR1 expression (Duan et al., 2014), we next detected whether MF could regulate CX3CR1 via PPM1A/NF-κB signaling in 3 × Tg mice. qRT-PCR and western blot results demonstrated that MF upregulated CX3CR1 mRNA level in microglia (Fig. S8C) and protein level in cortex (Figs. S8D and E) from 3 × Tg mice. Notably, MF had no impacts on CX3CR1 expression in 3 × Tg + AAV-KD mice (Figs. S8F and G).

4. Discussion

AD is a progressively neurodegenerative disease without curable medication. Although PPM1A regulation was reported to be implicated in the pathology of peripheral immunity diseases (Dvashi et al., 2014), the role of PPM1A in the CNS is yet largely unknown. Here, we firstly determined that PPM1A regulation is associated with AD-like pathology and PPM1A activation ameliorated cognitive impairment in AD model mice. Our findings may help deepen our understanding of neuroinflammatory response and address the potential of PPM1A as a target against AD.

Miltefosine (MF) was approved by FDA (March 19, 2014) for treatment of three main types of leishmaniasis (Visceral leishmaniasis, Cutaneous leishmaniasis and Mucosal leishmaniasis) (Garcia Bustos et al., 2014) and is also clinically used for palliative care of several cancers (breast cancer (Terwogt et al., 1999), etc.) that are difficult to be treated by conventional treatment. Here, we determined that MF as a new PPM1A activator improved cognitive impairment of AD model mice and the underlying mechanisms were intensively expounded. Our results highlighted the potential of MF in treating AD. Notably, v-akt routine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) was ever reported as a target of MF (Dorlo et al., 2012), and our result (Fig. S9) that MF had no impacts on AKT phosphorylation in vitro or in vivo has verified that the anti-AD efficiency of MF is independent on AKT targeting. It is expected that the obtained preclinical and clinical data of MF may provide valuable references for subsequent development of anti-AD drug based on this “old drug”.

NLRP3 inflammasome is a protein complex whose activation promotes secretion and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 functioning potently in inflammatory responses (Davis et al., 2011). It was noted that MF inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in macrophages (Iacano et al., 2019) and inflammasome gene expression (IL-1β, Caspase-1, NLRP3, etc.) in human monocytes (Andre et al., 2020), but whether and how MF inhibits inflammasome activation in microglia are largely unknown. Here, we determined that MF suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation in both priming and assembly processes in microglia by targeting PPM1A. In the priming step, MF reduced NLRP3 transcription by inhibiting the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. In the assembly step, MF inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome assembly by binding directly to LRR-NLRP3 domain. Notably, several mutations within LRR-NLRP3 are linked to inflammatory disease (Caseley et al., 2021) and targeting LRR domain has been represented as a potential in treating NLRP3-mediated inflammatory diseases. Our findings have supplied new evidence on the role of MF in microglia regulation. To our knowledge, our work might be the first to report the regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome in such a “two-step” interruption model, which may better our design of effective strategy in fighting against AD and neuroinflammation-related diseases.

Some phosphoprotein phosphatases including PP1, PP2A, PP1B and PP5 were reported to dephosphorylate tau (Martin et al., 2013). For example, PPM1B as a PPM member could inhibit Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase-1A (DYRK1A) kinase activity and reduce tau hyperphosphorylation (Lee et al., 2021). Additionally, we also determined that MF as a PPM1A activator inhibited neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation involving microglia/neurons crosstalk through PPM1A/NLRP3/tau axis in AD mice without influencing basal tau phosphorylation in primary neurons, which is consistent with the previous report that PPM1A had no effects on tau phosphorylation in vitro (Gong et al., 1994). In addition, CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis plays a central role in communications between microglia and neurons (Chen et al., 2016). Our results have revealed a reduction of CX3CR1 level in 3 × Tg-AD mice cerebral cortex in agreement with its reported lower expression in cortex and hippocampus of AD patients (Cho et al., 2011). We also determined that PPM1A activation promoted microglial tau phagocytosis involving PPM1A/NF-κB/CX3CR1 signaling. Collectively, our results have firstly revealed the potency of PPM1A in mediating the crosstalk between microglia and neurons by targeting NLRP3.

According to the published reports, nearly 2/3 AD patients are female, and the risk of developing AD is higher in postmenopausal women (Alzheimer's, 2015). Moreover, female AD patients show a broader spectrum of dementia-related behavioral symptoms than male (Irvine et al., 2012). Thus, we also examined the behavioral improvement of MF in female 3 × Tg-AD mice, and the results indicated that MF ameliorated cognitive deficits in female 3 × Tg-AD mice by targeting PPM1A (Fig. S10).

In summary, we reported that PPM1A activation improved cognitive impairments in 3 × Tg mice, and the underlying mechanisms have been intensively investigated (Fig. 7). PPM1A activation repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation by both reducing NLRP3 transcription in the priming process and promoting PPM1A binding to LRR domain of NLRP3 to interfere the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome in the assembly process, leading to the suppression of neuroinflammation and tau hyperphosphorylation. Meanwhile, PPM1A activation also promoted microglial phagocytosis of tau oligomers involving PPM1A/NF-κB/CX3CR1 signaling. Our work has revealed a key role for the host phosphatase PPM1A as a positive regulator in regulation of AD pathology and highlighted the potential of MF in the treatment of AD or other neuroinflammation-related neurodegenerative disorders.

Fig. 7.

A proposed model illustrating the mechanism underlying the amelioration of PPM1A activation on AD-like pathology in 3 × Tg mice. PPM1A activation repressed NLRP3 inflammasome by both reducing NLRP3 transcription in priming step and promoting PPM1A binding to LRR-NLRP3 to interfere the associations of ASC and procaspase-1 in assembly step, thus leading to suppression of neuroinflammation and tau hyperphosphorylation. Meanwhile, PPM1A activation promoted microglial tau phagocytosis involving PPM1A/NF-κB/CX3CR1 axis.

Author contributions

JLL, XYS (Xingyi SHEN), JYW and XS designed the study; JLL, XYS (Xingyi SHEN), XYS (Xinya SHEN), XQL, ZYJ, XNOY, JL and DYZ performed the research; JLL, XYS (Xinyi SHEN) and JYW analyzed the data; JLL, XYS (Xingyi SHEN), JYW and XS wrote the paper. JLL, XYS (Xingyi SHEN), JYW and XS are the guarantors of this work and, as such, have full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273930), China; Innovative Research Team of Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province (TD-SWYY-013), China; The Open Project of Chinese Materia Medica First-Class Discipline of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (No. 2020YLXK018) and “Qing Lan” project, China. The funders had no roles in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, writing of the report. We thank Qin Zhu, Leilei Gong and Yi Zhai (Experiment center for science and technology, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine) for technical supports in instrument operation and images quantification.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100546.

Contributor Information

Jiaying Wang, Email: wangjy@njucm.edu.cn.

Xu Shen, Email: xshen@njucm.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

figs1.

figs2.

figs3.

figs4.

figs5.

figs6.

figs7.

figs8.

figs9.

figs10.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Afonina I.S., Zhong Z., Karin M., Beyaert R. Limiting inflammation-the negative regulation of NF-kappaB and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2017;18(8):861–869. doi: 10.1038/ni.3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's A. 2015 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3):332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre S., Rodrigues V., Pemberton S., Laforge M., Fortier Y., Cordeiro-da-Silva A., MacDougall J., Estaquier J. Antileishmanial drugs modulate IL-12 expression and inflammasome activation in primary human cells. J. Immunol. 2020;204(7):1869–1880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1900590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolos M., Llorens-Martin M., Perea J.R., Jurado-Arjona J., Rabano A., Hernandez F., Avila J. Absence of CX3CR1 impairs the internalization of Tau by microglia. Mol. Neurodegener. 2017;12(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi S., Morisetti A. Margins of safety of intravascular contrast media: body weight, surface area or toxicokinetic approach? Arh. Hig. Rada. Toksikol. 2005;56:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsolaro V., Edison P. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: current evidence and future directions. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(6):719–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caseley E.A., Lara-Reyna S., Poulter J.A., Topping J., Carter C., Nadat F., Spickett G.P., Savic S., McDermott M.F. An atypical autoinflammatory disease due to an LRR domain NLRP3 mutation enhancing binding to NEK7. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021;42(1):158–170. doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-01161-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Lennon J.C., Malkaram S.A., Zeng Y., Fisher D.W., Dong H. Serotonergic system, cognition, and BPSD in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2019;704:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Zhao W., Guo Y., Xu J., Yin M. CX3CL1/CX3CR1 in alzheimer's disease: a target for neuroprotection. BioMed Res. Int. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8090918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.H., Sun B., Zhou Y., Kauppinen T.M., Halabisky B., Wes P., Ransohoff R.M., Gan L. CX3CR1 protein signaling modulates microglial activation and protects against plaque-independent cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:32713–32722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.254268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco S., Rinaudo M., Fusco S., Longo V., Gironi K., Renna P., Aceto G., Mastrodonato A., Li Puma D.D., Podda M.V., Grassi C. Plasma BDNF levels following transcranial direct current stimulation allow prediction of synaptic plasticity and memory deficits in 3xTg-AD mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:541. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congdon E.E., Sigurdsson E.M. Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018;14(7):399–415. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B.K., Wen H., Ting J.P. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorlo T.P., Balasegaram M., Beijnen J.H., de Vries P.J. Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2576–2597. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F. Golgi-cox staining of neuronal dendrites and dendritic spines with FD Rapid GolgiStain kit. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2019;88(1):e69. doi: 10.1002/cpns.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan M., Yao H., Cai Y., Liao K., Seth P., Buch S. HIV-1 Tat disrupts CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis in microglia via the NF-kappaBYY1 pathway. Curr. HIV Res. 2014;12(3):189–200. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140526123119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvashi Z., Sar Shalom H., Shohat M., Ben-Meir D., Ferber S., Satchi-Fainaro R., Ashery-Padan R., Rosner M., Solomon A.S., Lavi S. Protein phosphatase magnesium dependent 1A governs the wound healing-inflammation-angiogenesis cross talk on injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2014;184(11):2936–2950. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerberg L., Hallström B.M., Oksvold P., Kampf C., Djureinovic D., Odeberg J., Habuka M., Tahmasebpoor S., Danielsson A., Edlund K., Asplund A., Sjöstedt E., Lundberg E., Szigyarto C.A.-K., Skogs M., Takanen J.O., Berling H., Tegel H., Mulder J., Nilsson P., Schwenk J.M., Lindskog C., Danielsson F., Mardinoglu A., Sivertsson Å., von Feilitzen K., Forsberg M., Zwahlen M., Olsson I., Navani S., Huss M., Nielsen J., Ponten F., Uhlén M. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2014;13(2):397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabande-Rodriguez E., Keane L., Capasso M. Microglial phagocytosis in aging and Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019;98(2):284–298. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Bustos M.F., Barrio A., Prieto G.G., de Raspi E.M., Cimino R.O., Cardozo R.M., Parada L.A., Yeo M., Soto J., Uncos D.A., Parodi C., Basombrio M.A. In vivo antileishmanial efficacy of miltefosine against Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis. J. Parasitol. 2014;100(6):840–847. doi: 10.1645/13-376.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C.X., Grundke-Iqbal I., Damuni Z., Iqbal K. Dephosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by protein phosphatase-1 and -2C and its implication in Alzheimer disease. FEBS Lett. 1994;341(1):94–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80247-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Hara H., Nunez G. Mechanism and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016;41(12):1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Kulasiri D., Samarasinghe S. Modelling bidirectional modulations in synaptic plasticity: a biochemical pathway model to understand the emergence of long term potentiation (LTP) and long term depression (LTD) J. Theor. Biol. 2016;403:159–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M.T., Kummer M.P., Stutz A., Delekate A., Schwartz S., Vieira-Saecker A., Griep A., Axt D., Remus A., Tzeng T.C., Gelpi E., Halle A., Korte M., Latz E., Golenbock D.T. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer's disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature. 2013;493(7434):674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V., Bauernfeind F., Halle A., Samstad E.O., Kono H., Rock K.L., Fitzgerald K.A., Latz E. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9(8):847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacano A.J., Lewis H., Hazen J.E., Andro H., Smith J.D., Gulshan K. Miltefosine increases macrophage cholesterol release and inhibits NLRP3-inflammasome assembly and IL-1beta release. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47610-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine K., Laws K.R., Gale T.M., Kondel T.K. Greater cognitive deterioration in women than men with Alzheimer's disease: a meta analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2012;34(9):989–998. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.712676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ising C., Venegas C., Zhang S., Scheiblich H., Schmidt S.V., Vieira-Saecker A., Schwartz S., Albasset S., McManus R.M., Tejera D., Griep A., Santarelli F., Brosseron F., Opitz S., Stunden J., Merten M., Kayed R., Golenbock D.T., Blum D., Latz E., Buee L., Heneka M.T. NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives tau pathology. Nature. 2019;575(7784):669–673. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1769-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khim K.W., Choi S.S., Jang H.J., Lee Y.H., Lee E., Hyun J.M., Eom H.J., Yoon S., Choi J.W., Park T.E., Nam D., Choi J.H. PPM1A controls diabetic gene programming through directly dephosphorylating PPARgamma at Ser273. Cells. 2020;9(2):343. doi: 10.3390/cells9020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickstein E., Krauss S., Thornhill P., Rutschow D., Zeller R., Sharkey J., Williamson R., Fuchs M., Kohler A., Glossmann H., Schneider R., Sutherland C., Schweiger S. Biguanide metformin acts on tau phosphorylation via mTOR/protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107(50):21830–21835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912793107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.H., Im E., Hyun M., Park J., Chung K.C. Protein phosphatase PPM1B inhibits DYRK1A kinase through dephosphorylation of pS258 and reduces toxic tau aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.015574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Duan X., Liang Y.Y., Su Y., Wrighton K.H., Long J., Hu M., Davis C.M., Wang J., Brunicardi F.C., Shi Y., Chen Y.G., Meng A., Feng X.H. PPM1A functions as a Smad phosphatase to terminate TGFbeta signaling. Cell. 2006;125(5):915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Li B., Tung E.J., Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Gong C.X. Site-specific effects of tau phosphorylation on its microtubule assembly activity and self-aggregation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26(12):3429–3436. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueptow L.M. Novel object recognition test for the investigation of learning and memory in mice. JoVE. 2017;30(126) doi: 10.3791/55718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Wang W., Zhu X., Xu X., Yan Q., Lu J., Shi X., Wang Z., Zhou J., Huang X., Wang J., Duan W., Shen X. DW14006 as a direct AMPKalpha1 activator improves pathology of AD model mice by regulating microglial phagocytosis and neuroinflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;90:55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L., Latypova X., Wilson C.M., Magnaudeix A., Perrin M.L., Yardin C., Terro F. Tau protein kinases: involvement in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013;12(1):289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson-Carlgren N., Janelidze S., Palmqvist S., Cullen N., Svenningsson A.L., Strandberg O., Mengel D., Walsh D.M., Stomrud E., Dage J.L., Hansson O. Longitudinal plasma p-tau217 is increased in early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2020;143(11):3234–3241. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun M.A., Lo A.C., Duggan Evans C., Wessels A.M., Ardayfio P.A., Andersen S.W., Shcherbinin S., Sparks J., Sims J.R., Brys M., Apostolova L.G., Salloway S.P., Skovronsky D.M. Donanemab in early alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384(18):1691–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Planillo R., Kuffa P., Martinez-Colon G., Smith B.L., Rajendiran T.M., Nunez G. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth Z.H., Deitch E.A., Szabo C., Hasko G. Pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate inhibits NF-kappa B activation and IL-8 production in intestinal epithelial cells. Faseb. J. 2003;17(5):A1367. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(02)00208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuhiro Aburai, M Y., Motoko Ohnishi, Ken-ichi Kimura. Sanguinarine as a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2C in vitro and induces apoptosis via phosphorylation of p38 in HL60 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010;74(3):548–552. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J.D., Murphy M.P., Golde T.E., Kayed R., Metherate R., Mattson M.P., Akbari Y., LaFerla F.M. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39(3):409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek P., Ben-Meir D., Kariv-Inbal Z., Oren M., Lavi S. Cell cycle regulation and p53 activation by protein phosphatase 2C alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(16):14299–14305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea J.R., Llorens-Martin M., Avila J., Bolos M. The role of microglia in the spread of tau: relevance for tauopathies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018;12:172. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal B.M., Giger R.J. Stable biomarker for plastic microglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113(12):3130–3132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601669113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaftel S.S., Griffin W.S.T., O'Banion M.K. The role of interleukin-1 in neuroinflammation and Alzheimer disease: an evolving perspective. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif H., Wang L., Wang W.L., Magupalli V.G., Andreeva L., Qiao Q., Hauenstein A.V., Wu Z., Nunez G., Mao Y., Wu H. Structural mechanism for NEK7-licensed activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2019;570(7761):338–343. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J.Q., Wang B.R., Jiang T., Gao L., Zhang Y.D., Xu J. NLRP3 inflammasome: a potential therapeutic target in fine particulate matter-induced neuroinflammation in alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020;77(3):923–934. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N., Liu Z.S., Xue W., Bai Z.F., Wang Q.Y., Dai J., Liu X., Huang Y.J., Cai H., Zhan X.Y., Han Q.Y., Wang H., Chen Y., Li H.Y., Li A.L., Zhang X.M., Zhou T., Li T. NLRP3 phosphorylation is an essential priming event for inflammasome activation. Mol. Cell. 2017;68(1):185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.017. e186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Yu Y., Dotti G., Shen T., Tan X., Savoldo B., Pass A.K., Chu M., Zhang D., Lu X., Fu S., Lin X., Yang J. PPM1A and PPM1B act as IKKbeta phosphatases to terminate TNFalpha-induced IKKbeta-NF-kappaB activation. Cell. Signal. 2009;21:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Guo Y., Feng X., Fu L., Zheng Y., Dong Y., Zhang Y., Yu X., Kong W., Wu H. Norovirus P particle-based tau vaccine-generated phosphorylated tau antibodies markedly ameliorate tau pathology and improve behavioral deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2021;6(1):61. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]