Summary

In this report, we describe an approach to generate a zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation that can be used as an in vivo system to study hyperlipidemic conditions such as atherosclerosis. Furthermore, we detail steps on staining techniques, lipid estimation assays, RNA isolation, and utilization of ImageJ to evaluate larval dimensions and to explore the model in the context of hyperlipidemia. Researchers should be aware of context specificity of the proposed protocols and interpret results accordingly.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Balamurugan et al., (2022).

Subject areas: Metabolism, Model organisms

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protocol to develop a zebrafish model of lipid accumulation to study atherosclerosis

-

•

Visualize lipid deposition in zebrafish larvae

-

•

Estimate lipid levels in zebrafish larvae using kits and HPLC

-

•

Step-by-step guide to measure body length and width of zebrafish larvae

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

In this report, we describe an approach to generate a zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation that can be used as an in vivo system to study hyperlipidemic conditions such as atherosclerosis. Furthermore, we detail steps on staining techniques, lipid estimation assays, RNA isolation, and utilization of ImageJ to evaluate larval dimensions and to explore the model in the context of hyperlipidemia. Researchers should be aware of context specificity of the proposed protocols and interpret results accordingly.

Before you begin

By virtue of its transparency, amenability to genetic intervention and rapid developmental growth rate, zebrafish larvae are being utilized as in vivo models for various diseases including inflammatory disorders (Novoa and Figueras, 2012), cancer (Hason and Bartůněk, 2019), Non-Alcoholic SteatoHepatitis (NASH) (Yan et al., 2017), Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Ma et al., 2019) (Chen et al., 2018), and Cardio Vascular Diseases (CVD) (Stoletov et al., 2009) (Bandaru et al., 2015). Remarkable similarity of lipid profiles and lipogenic regulation between humans and zebrafish is the main rationale behind its usage in hyperlipidemic studies (Santoriello and Zon, 2012). Usage of fluorescence and colorimetric techniques such as labeling of lipid molecules, staining of blood vessels and macrophages in zebrafish larvae enable us to visualize and assess lipid trafficking in live larvae (Fang et al., 2014) (Anderson et al., 2016) (Quinlivan and Farber, 2017). Consistently, estimation of neutral lipids such as cholesteryl esters and free fatty acid levels in larvae using biochemical assays and HPLC can reveal minute differences in lipid accumulation in zebrafish.

Although it is difficult to observe weight differences in zebrafish at their larval stages even with high throughput techniques upon administration of a high-fat diet (HFD), measurement of body length and width of larvae would aid in understanding the change in phenotype of obese larval models. Similarly, gene expression assessment by q-PCR and western blotting would aid us to derive conclusions regarding lipid regulation and metabolism in an HFD model of zebrafish larvae. Overall, for lipogenic analysis in the model, we present detailed and systematic protocols below.

The following are the basic essentials that should be available prior to commencement of the experiments.

-

1.Confirm the availability of healthy male and female zebrafish with a proper housing facility accommodating the following basic requirements.

-

a.Spacious and ventilated housing system capable of maintaining light/dark cycles.

-

b.Availability of temperature-controller, quality water (preferably with automatic filtration and recirculation), UV disinfection and quality feed.

-

c.Incubator that can maintain 37°C for larval maintenance.

-

d.Availability of breeding tanks.

-

a.

-

2.

Ensure all the required chemicals such as Oil Red O, Nile red etc. (Refer KRT table) are available and are not past the expiry date.

-

3.

Make sure that stereo microscope and fluorescent microscope are available for embryo and larval visualization.

Institutional permissions

Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Dr. Reddy’s Institute of Life Sciences, Hyderabad, India (DRILS-IAEC-KP-2019-1), approved all animal experiments reported here. The described methods are also in-line with the proposed national and international guidelines. The housing facility has national-level apex committee CPCSEA registration and approval. The facility also has assurance from current NIH-OLAW for foreign institutions.

Prepare 1× E3 media

Timing: 20–30 min

-

4.

Dilute 16.5 mL of 60× stock E3 media in 1-liter double distilled water.

Note: Both 60× and 1× concentrations of E3 media can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C) for two months.

CRITICAL: Autoclave the media prior to further usage.

Prepare Nile red stock

Timing: 10–15 min

-

5.

Dissolve 0.25 mg of Nile red (Mol. Wt.: 318.369 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich, 72485) in 1 mL of 0.4% acetone. This will result to 0.79 mM Nile red working solution.

Note: The solution can be stored at 4°C for not more than 2 months and its re-use is not recommended.

CRITICAL: Nile red must be weighed in the dark.

Prepare Oil Red O stain

Timing: 12–16 h

-

6.

Dissolve 0.3 g of Oil Red O (Mol. Wt.: 408.5 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich, O0625) in 100 mL of 100% isopropanol. This will yield 7.3 mM Oil Red O working solution.

-

7.

Heat the mixture at 60°C for overnight (12–16 h).

Note: Carry out the boiling in water bath to facilitate uniform heat distribution.

Note: This stock solution can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C) for up to 2 months.

-

8.

On the day of staining, pre-heat the stock solution at 56°C for 10 min in a water bath.

CRITICAL: Filter the working solution using 0.2-micron filter prior to usage to eliminate any Oil Red O powder clumps.

CRITICAL: Weigh and prepare the Oil Red O solution preferably in the dark.

Prepare HPLC standards

Timing: 20–30 min

-

9.

Preparation of blank solution: Use diluent [Acetonitrile (ACN): Tetrahydrofuran (THF) (70:30) v/v] for blank run.

-

10.Preparation of solutions for calibration curve:

-

a.Preparation of 0.5 M standard stock solution:

-

i.Transfer accurately about 9.6 mg of Cholesterol standard into a 50 mL volumetric flask. Add diluent and sonicate in an ultrasonic bath until the cholesterol is dissolved completely.

-

ii.Dilute up to the mark with diluent and mix well.

-

i.

-

a.

-

11.

Preparation of the 2.5 μg/mL (6.25 μM) solution: Pipette out 0.25 mL of Standard Stock Solution into 20 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to mark with diluent and mix.

-

12.

Preparation of the 5 μg/mL (12.5 μM) solution: Pipette out 0.5 mL of Standard Stock Solution into 20 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to mark with diluent and mix.

-

13.

Preparation of the 10 μg/mL (25 μM) solution: Pipette out 1.0 mL of Standard Stock Solution into 20 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to mark with diluent and mix.

-

14.

Preparation of the 15 μg/mL (37.5 μM) solution: Pipette out 1.5 mL of Standard Stock Solution into 20 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to mark with diluent and mix.

-

15.

Preparation of the 20 μg/mL (50 μM) solution: Pipette out 2 mL of Standard Stock Solution into 20 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to mark with diluent and mix.

CRITICAL: All solutions should be prepared fresh and used immediately. However, the powder form of samples can be stored in 4°C for 2–3 days.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| RNAiso Plus (TRIzol) | Takara Bio | 9109 |

| Oil Red O (C26H24N4O) | Sigma-Aldrich | O0625 |

| Nile red (C20H18N2O2) | Sigma-Aldrich | 72485 |

| Ammonium acetate (NH₄CH₃CO₂) | LiChropur | 5.33004 |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) (HPLC grade) | Rankem | 109-99-9 |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) (CH ₃CN) (Gradient grade) | Finar | 75-5-8 |

| Isopropanol (CH3)2CHOH) (HPLC grade) | Merck | 109634 |

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) | SRL | 33205 |

| Potassium chloride (KCl) | SRL | 84984 |

| Calcium dichloride dihydrate (CaCl2.2H2O) | Merck | 10035-04-8 |

| Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2.6H2O) | Merck | 7791-18-6 |

| Sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4) | Merck | 7558-79-4 |

| Potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4) | Merck | 7778-77-0 |

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) | Merck | 10812846001 |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | SRL | 43272 (054448) |

| Chloroform extrapure (CHCl3) AR, 99.5% | SRL | 84155 |

| Ethanol (C2H5OH) | Merck | 100983 |

| 30% Acrylamide / Bis-acrylamide Mix Solution (Ratio 29:1) | SRL | 67394 |

| Cholesterol, ≥99% | Sigma-Aldrich | C8667 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Total cholesterol estimation kit | Erba | BLT00034; CHOL 5 × 50 |

| Free fatty acid estimation kit | Sigma-Aldrich | MAK044 |

| Prime Script IV 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Mix | Takara Bio | RR037A |

| TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNase H Plus) | Takara Bio | RR820A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji/ImageJ | NIH | RRID: SCR_002285 |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | RRID: SCR_016137 |

| Biorender | Web tool for graphical illustrations | RRID: SCR_018361 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Zebrafish | Wild Caught and Bred In-House | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Agilent 1200 HPLC | Agilent Technologies | NA |

| Mini Centrifuge | GENAXY | 6KS |

| Microcentrifuges | Eppendorf | 5424R |

| BioSpectrometer | Eppendorf | 6135000009 |

| Gel Imaging System | Azure Biosystems | Azure 600 |

| ZebTEC rack with Active Blue technology | Tecniplast | ZB52550SAABXS2 |

| 1.7 L SLOPE BREEDING TANK | Tecniplast | ZB17BTISLOP |

| Barnstead lab line L-c Incubator | Barnstead International | 403-1 |

| Frippak PL+150 Ultra Feed | INVE Aquaculture | N/A |

| Frippak PL+300 Ultra Feed | INVE Aquaculture | N/A |

| Artemia Cysts | INVE Aquaculture | N/A |

| Analytical Balance | Sartorius | CPA225D |

| SPINIX Vortex Shaker | Tarsons | 3020 |

| Ultrasonic bath sonicator | Cole-Parmer | N/A |

| QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System | Applied Biosystems | N/A |

Materials and equipment

E3 media (60× stock)

| Reagent (molecular weight) | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) (58.44 g/mol) | 0.29 mM | 17.4 g |

| Potassium chloride (KCl) (74.55 g/mol) | 0.01 mM | 0.8 g |

| Calcium dichloride dihydrate (CaCl2.2H2O) (147.01 g/mol) | 0.019 mM | 2.9 g |

| Magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl2.6H2O) (203.3027 g/mol) | 0.024 mM | 4.89 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | Make up to 1,000 mL |

| Total | N/A | 1,000 mL |

Can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C) and should be used within 2 months.

CRITICAL: A stock of 60× E3 media is prepared in double distilled water and pH is adjusted to 7.2 with NaOH.

1× PBS

| Reagent (molecular weight) | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium chloride (NaCl) (58.44 g/mol) | 0.137 mM | 8 g |

| Potassium chloride (KCl) (74.55 g/mol) | 0.0027 mM | 0.2 g |

| Sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4) (141.96 g/mol) | 0.01 mM | 1.44 g |

| Potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4) (136.09 g/mol) | 0.0018 mM | 0.245 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | Make up to 1,000 mL |

| Total | N/A | 1,000 mL |

Can be stored at room temperature (20°C–25°C). However, for long term usage of more than 1 month, storage at 4°C is advised. The solution can be stored at 4°C for a maximum of 6 months.

CRITICAL: The pH is adjusted to 7.2–7.4 and is autoclaved before use.

Lipid lysis buffer

| Reagent (molecular weight) | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) (121.14 g/mol) | 1 mM | 121.14 g |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (292.2438 g/mol) | 20 mM | 5.84 g |

| ddH2O | N/A | Make up to 1,000 mL |

| Total | N/A | 1,000 mL |

Store at 4°C.

CRITICAL: Do not autoclave lipid lysis buffer (but preferably prepare fresh before experiment) and prepare in double distilled water as indicated.

Step-by-step method details

Zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation

Timing: 13–20 days

Timing: Breeding: 1–2 h (for step 1)

Timing: Embryo collection: 15–20 min (for step 2)

Timing: Transfer of larvae from plate to tank: 5–10 min (for step 3)

Timing: Feeding: 5–10 min; Tank cleaning: 10–15 min (for step 6)

Toward understanding the lipid deposition in intersegmental vessels of larvae upon administering cholesterol rich diet, a primer of pre-atherosclerotic event that occurs in humans due to high lipid intake, zebrafish model of lipid accumulation can be generated as stated below:

-

1.Obtain embryos via in-house breeding of wild-caught zebrafish.

-

a.The wildtype zebrafish should be fed with artemia (INVE aquaculture; Feed type: FRiPPAK PL+150) diet twice a day and should be maintained in tanks that recirculates reverse osmosed, 0.2% sea-salt added water at 28 ± 1°C, and also maintains a 12 h dark/light cycle.Note: In our case, we used Tecniplast active blue stand-alone rack to maintain live fish.

-

b.Live shrimp in brine should be given every alternate day along with control artemia feed.

-

c.A week prior to mating, the fish should be gender segregated and maintained in separate tanks.

-

d.Carry out in-house breeding of male and female fish of minimum 2 months old, in the ratio of 3:2 in a breeding chamber that imitates shallow waters.Note: For our experiments, we used a chamber that contains a pitted partition where the embryos can be collected without being damaged.

-

e.Preceding day of mating, the fish should be well fed with artemia and shrimp and are kept gender parted (via removable divider) in the breeding chamber.

-

f.The following day, artificial light (in addition to day-light) should be switched on and the divider should be taken off.

-

a.

-

2.

Maintain embryos in bacterial petri plates with E3 media at 28°C for 5 days.

CRITICAL: Examine for any embryonic deaths (opaque white yolk) the following day and remove the infertile embryos as they clump with healthy ones and damages them otherwise.

Note: Change media using 3 mL plastic pipette dropper with caution not to damage the healthy embryos. Add around 15 mL of E3 media to each petri plate and do not maintain more than 50 embryos in one plate. Add an additional 1 mL of fresh E3 media to the plate every consecutive day till fifth day (post fertilization).

-

3.Once larvae emerge from the chorion, transfer 5 dpf (5 days post fertilization) larvae to fresh water tank and feed with finely powdered artemia twice a day.

-

a.Sprinkle powdered artemia (INVE aquaculture; Feed type: FRiPPAK PL+150) of 0.2 g using paint brush twice a day.

CRITICAL: Clean the water surface by sliding a tissue every day to clear the sedimented left-over powder before feeding fresh powder.

CRITICAL: Clean the water surface by sliding a tissue every day to clear the sedimented left-over powder before feeding fresh powder. -

b.Add fresh water to the tank every alternate day till termination of experiments (till 13–20 dpf). Do not harvest more than 100 larvae in a single tank of dimension 10∗19.5∗9 inches.

-

c.Fill the water up to not more than half of the tank’s height (approximately 250 mL).

-

d.In case of observations of abundant larval deaths with powdered artemia feed, shift to lab-cultured live microalgae and rotifer co-culture as control feed to larvae from 5 dpf till completion of experiments (13/20 dpf).Note: The cause of deaths could be due to inability of larvae to ingest the powder because of its size (troubleshooting problem 1).

-

e.Upon usage of microalgae and rotifer co-culture, prepare fresh culture every month and add 1 mL of the culture to the larvae twice a day.

-

a.

-

4.

To generate zebrafish model of lipid accumulation, use a feed load of 0.8 mg/mL (0.08%; 0.2 g of boiled egg yolk in 250 mL of water).

-

5.

The store-bought eggs used to prepare HFD feed should be boiled at medium flame for 6–7 min.

-

6.Provide both control and high fat diet at the same time every day for control and test batches.

-

a.Boil antibiotic free egg, separate the yolk and crush into powder using mortar and pestle and store in −20°C for not more than 3 days.Note: Prepare another batch of fresh yolk post usage for three days as feed.

-

b.Every day, weigh 0.2 g of boiled egg yolk, re-suspend in fresh water and add to the larvae as drops so that the yolk is mixed throughout.

-

c.Blend the powdered yolk with water via pipetting using a 5 mL dropper gently for not more than 7 times.

CRITICAL: Rigorous or fine mixing of egg yolk and water must be avoided as it will generate fungi like mass in water making it hard for the larvae to breath. Also, some larvae may get stuck in the mass and die.

CRITICAL: Rigorous or fine mixing of egg yolk and water must be avoided as it will generate fungi like mass in water making it hard for the larvae to breath. Also, some larvae may get stuck in the mass and die.

-

a.

Hence, remove the yolk remnants that are settled at the bottom of the tank everyday (using disposable 5 mL droppers) and add little bit fresh water to make up the volume to ∼250 mL. Marking the tank would aid in filling of water to the required level. In addition to the removal of the debris (settled yolk and excreta) every day, change the water every alternate day as mentioned for control feed to reduce the microbial load (steps-3b,3c). To monitor the microbial load, the water may be analyzed for microbial growth via performing colony counts on agar plates post washing off the feed.

Note: a) Dried chicken egg yolk powder has been used as a HFD diet by various researchers to establish hyperlipidemia in adult zebrafish as well as in zebrafish larvae (Marza et al., 2005) (Otis and Farber, 2016). Interestingly, Carten et al. utilized thawed frozen chicken egg yolk and zebrafish embryonic membrane emulsion feed to deliver different chain length FA analogs (BODIPY-FL) (Carten et al., 2011). It is also to be noted that feed quality, intake and other characteristics show variation from lab to lab and even within experiments (Watts et al., 2012). b) Earlier reports suggest different frequencies of water change during zebrafish larval maintenance, especially during usage of egg yolk or egg yolk liposomes as feed (Zhou et al., 2015) (Ye et al., 2019) (Den Broeder et al., 2017) (Chen et al., 2015) (Maddison and Chen, 2012). However, the rationale behind the same depends on the larval density and the amount of egg yolk used in a high-fat diet (HFD). In our case, for a feed density of 0.8 mg /mL of boiled egg yolk in water, and a larval density of 100 larvae per 250 mL of water, we change water every alternate day in addition to manual surface cleaning every day before feeding (steps-3a, 3b and 6a–c).

-

7.

For staining experiments, harvest the larvae by 13 days (as 8 days of HFD feeding to visually observe the lipid deposition in head, trunk, tail as well as in intersegmental vessels). However, for lipid estimation studies, continue the feed till 20 days (15 days of feeding) as very less amounts of lipids will be obtained from 13 dpf larvae.

Note: it is to be noted that in studies involving drug administration or genetic modifications where the larval feed uptake may vary as a response, control feeding assays should be performed in the animals for rational validation. Various researches have utilized fluorescently labeled viable paramecia such as 4-10-Di-ASP-labeled paramecia, fish food coated fluorescent microspheres or fluorescent Tetrahymena to evaluate the feed intake, especially in larvae, in view of their transparent body (Shimada et al., 2012) (Boyer et al., 2013) (Hsieh et al., 2021) (Hsieh et al., 2021). For appropriate HFD controls in hyperlipidemic studies, high fat feed serves are fluorescently (NBD- and BODIPY-Cholesterol) or radioactively labeled (14C-labeled lipids) to monitor lipid trafficking in live larvae, which can be used to indirectly measure lipid (feed) uptake (Sæle et al., 2018) (Anderson et al., 2016). Additional experimental designs may be applied with the individual researcher’s decision to account for any potential metabolic effects associated with perturbation of specific genes under study.

-

8.To measure cholesterol and free fatty acid levels using kits from Erba and Sigma respectively, extract lipids using Bligh and Dyer method and concentrate the lipids via solvent evaporation through nitrogen streaming, which are described in the following sections.

-

a.On the day of larval harvesting for lipid estimation assays, starve the larvae from the previous day and collect them in the evening for further experimentations. This allows elimination of intestinal lipids and excessively stored fat depots.

-

a.

Fluorescent and calorimetric larval staining studies

Timing: 5–6 h post 12–16 h fixation (for step 9)

Timing: Harvesting: 20 min; Euthanization:30–40 min (for step 9 a)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 9 e)

Timing: 12–16 h (for step 9 f)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 9 g)

Timing: 30–40 min (for step 9 h)

Timing: 3(1/2)–4 h (for step 9 j)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 9 l)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 9 m)

Timing: 5–6 h post overnight (12–16 h) fixation (for step 10)

Timing: 35–40 min (for step 10 b)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 10 c)

In order to evaluate lipid distribution in zebrafish larvae or histology sections of adult fish, researchers, for many years have been using fixative stains such as Oil Red O and Nile red, and kit-based lipid estimation assays owing to their low costs and simple procedure. With standardization of protocols in accordance with our experiments, these techniques can yield high throughput results.

CRITICAL: Conduct all larval staining experiments and lipid estimation assays in 13–20 dpf larvae and in addition, the experiments will be gender blinded as sex determination is not possible at this developmental stage.

-

9.

Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae.

Intended for staining of neutral lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides, Oil Red O stain has been used to demonstrate lipid accumulates in various systems ranging from cells to histological sections of animals. The dye is a lipid soluble lysochrome with the molecular formula C26H24N4O and has a calorimetric absorption at 518 nm, which therefore gives the lipids an orangish-red color upon observation under light microscope. Their inability to bind to biological membranes contribute to their specificity. Several studies have reported on Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae in the previous years (Chen et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016; Sadler et al., 2005; Schlegel and Stainier, 2006; Schlombs et al., 2003). Based on that we have formulated and followed the below protocol for our experiments.-

a.Post 4 days of control/HFD diet administration, harvest the larvae in the evening in a 1.5 mL microfuge tube and euthanize via incubation in ice (4°C) for 30–40 min.

-

b.Centrifuge the euthanized larvae in the tubes at 500 × g for 90 s and remove the water.

-

c.Add fresh 1× PBS to the tube and wash the larvae by gentle shaking for 3–5 min to remove any unwanted debris attached to the larvae.

-

d.Centrifuge the larvae again centrifuged at the same speed and time followed by PBS removal.

-

e.Repeat the 1× PBS washing thrice to ensure the elimination of contamination.

-

i.Place the tubes with the larvae in ice to a feasible extent and perform the centrifugation processes at 4°C.

-

i.

-

f.Subsequently, fix the larvae in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight (12–16 h) at 4°C.

-

g.Post fixation, wash the larvae three times with 1× PBS as described in steps-c to e, to remove any traces of paraformaldehyde.

-

i.Post fixation, the specimens need not be maintained at 4°C.

-

i.

-

h.Pre-incubate the larvae in 60% isopropyl alcohol for 30 min at room temperature (20°C–25°C) with moderate shaking.

-

i.Following incubation in 60% isopropanol, pellet the larvae via centrifugation at 500 × g for 90 s and remove the isopropanol solution.

-

j.Immediately add the filtered Oil Red O stain to the fish followed by gentle shaking for 3 h at 37°C.

-

i.After staining, centrifuge the larvae at 500 × g for 90 s at room temperature (20°C–25°C) and instantly remove the Oil Red O solution. Else the stain will form clumps which will be hard to remove during PBS wash in upcoming steps (troubleshooting problem 2).

-

i.

-

k.Centrifuge the larvae at 500 × g for 90 s to remove the stain and wash with 60% isopropyl alcohol three times to rinse off non-specific staining.

-

l.Perform the isopropanol wash similar to that of 1× PBS wash as described in steps-c to -e (Use 60% isopropanol in place of 1× PBS).

-

m.Subsequently, wash the larvae with 1× PBS thrice as specified in steps-c to -e and proceed to visualize microscopically at 4× (for head, trunk, and tail region) or 10× (for intersegmental vessel section) in light microscope (Figure 1).

CRITICAL: Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae must be carried out within 8 days post fertilization. In our case, even upon overnight (12–16 h) Oil Red O staining of 13 dpf larvae, bioimaging did not reveal any staining in larvae. Consistently, literature survey suggest that intensity of Oil Red O staining decreases in larvae post 6 dpf of age, especially in the intersegmental vessels despite similar lipid deposition, as revealed by fluorescence of CholEsteryl BODIPY 542/563 C11 (Chen et al., 2015).

CRITICAL: Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae must be carried out within 8 days post fertilization. In our case, even upon overnight (12–16 h) Oil Red O staining of 13 dpf larvae, bioimaging did not reveal any staining in larvae. Consistently, literature survey suggest that intensity of Oil Red O staining decreases in larvae post 6 dpf of age, especially in the intersegmental vessels despite similar lipid deposition, as revealed by fluorescence of CholEsteryl BODIPY 542/563 C11 (Chen et al., 2015).

-

a.

-

10.

Nile red staining of zebrafish larvae.

For fluorescent staining, 9-diethylamino-5H-benzo[alpha]phenoxazine-5-one, commonly known as Nile red can be used to stain the lipid accumulations in larvae. The dye is a near-ideal lysochrome and exhibits strong fluorescence properties in hydrophobic conditions. Its wide excitation/emission range of 450–500 nm/>580 nm (yellow) and 510–560/>590 nm (red) offers better selectivity in fluorescent microscopy experiments. Other than imaging techniques, the dye is also widely utilized in FACS studies. For better visualization and deep staining of internal organs of zebrafish larvae, Nile red staining has been performed in several studies which we standardized a little to suit our experimental requirements (Minchin and Rawls, 2011) (Carten and Farber, 2009) (Chen et al., 2015) (Guru et al., 2022).-

a.For Nile red staining of zebrafish larvae, develop lipid accumulation model as described in section: zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation and perform zebrafish euthanization and fixation as detailed in steps-a to -g of section: 9. Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae.

-

b.Post 1× PBS washing, incubate the larvae in Nile red solution precisely for 30 min at room temperature (20°C–25°C) with gentle shaking in the dark.

-

i.The solution must be thawed to room temperature (20°C–25°C) prior to addition.

CRITICAL: Incubation of larvae for more than 30 min is not advised as non-specific staining may occur (troubleshooting problem 3).

CRITICAL: Incubation of larvae for more than 30 min is not advised as non-specific staining may occur (troubleshooting problem 3).

-

i.

-

c.Re-wash the stained larvae with 1× PBS, 3 times for 3–5 min as indicated in steps -c to -e of section: 9. Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae and proceed with microscopic observations in EVOS fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL).

-

d.Acquire the images under RFP filter with an absorbance peak and emission peak of 531/40EX and 593/40EM, respectively and process the images in ImageJ software.

-

i.The intensity of image to be adjusted based on the microscope used. In EVOS FL, we generally fix the intensity of the image at 1%, as at higher intensities, the Nile red staining appears saturated in the images which in-turn can interfere with specific quantification (Figure 2B).

-

i.

-

e.Paste exactly sized images in ImageJ and convert to RGB stack via Image > Type > RGB stack.

-

f.Set same threshold to all images of each experiment (Image > Adjust > Threshold), in such a way that the processed images reflect only the Nile red stain.

-

g.To calculate mean, deselect ‘calculate threshold for each image’ and measure the mean value of stain (Analyze > measure).

- h.

-

a.

Figure 1.

Oil Red O and Nile red staining protocol of HFD-fed zebrafish larvae

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of Oil Red O versus Nile red staining and flowchart of ImageJ quantification of inter-segmental vessels in HFD-fed zebrafish larvae

(A) Oil Red O and Nile red staining of zebrafish larvae fed with control diet (CD) or High Fat Diet (HFD) for 7 or 13 days.

(B) Nile red staining of zebrafish larvae at different light intensities. Left panels: control diet; Right Panels: HFD-fed.

(C) Workflow for ImageJ based quantification of lipid accmulation in the inter-segmental vessels (ISV) of HFD-fed zebrafish larvae.

Lipid estimation assays in zebrafish larvae

Timing: 40–60 min (for step 11)

Timing: 15–20 min (for step 11 b)

Timing: 25–40 min (for step 11 d)

Timing: 20–30 min (for step 11 e)

Timing: 1–2 h (for step 12)

Timing: 5–10 min (for step 12 a)

Timing: 25–30 min (for step 12 b)

Timing: 5–10 min (for step 12 d)

Timing: 15–25 min (for step 12 f)

Timing: 8–10 h (for step 13)

Timing: 90–120 min post lipid isolation (for step 14)

Timing: Master mix preparation:10 min; Experiment: 35–45 min (for step 14 d)

Enriched deposition of neutral lipids such as cholesteryl esters and free fatty acids in the blood vessels, prominently due to intake of high cholesterol diet, is an essential hallmark of hyperlipidemia in humans as well as in other mammalian in vivo models such as mice, rabbit, zebrafish etc (Chan et al., 2015; Getz and Reardon, 2012; Madariaga et al., 2015). Consistently, we aimed towards estimating the accumulation of total cholesterol and free fatty acids (FFA) in our zebrafish model of lipid accumulation. Additionally, we attempted to evaluate minute perturbations in lipid build-up via HPLC method by co-relating area and concentration of standard cholesterol solution. Other studies have used similar HPLC based methods to detect lipid accumulation in zebrafish embryos and larvae (Fang et al., 2010; Martano et al., 2015; Quinlivan et al., 2017).

-

11.

Cholesterol measurement.

Enriched cholesterol levels in zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation may be measured using any commercially available kit. We used Erba kit for our experiments however we have not made any comparison of different commercially available kits.-

a.Collect equal numbers of 20 dpf control and HFD-fed larvae (minimum 50 nos.) in 1.5 mL microfuge tubes.Note: It is recommended to harvest considerable number of larvae for lipid estimation as lipid yield is very low even with 50 nos. larvae (troubleshooting problem 4).

-

b.Wash the larvae with 500 μL of 1× PBS to remove contaminants via centrifugation at 900 × g for 5 min at 4°C, twice.

-

c.Homogenize the larvae with microtube homogenizer by applying gentle rotations in ice in equal volumes of 1× PBS.

-

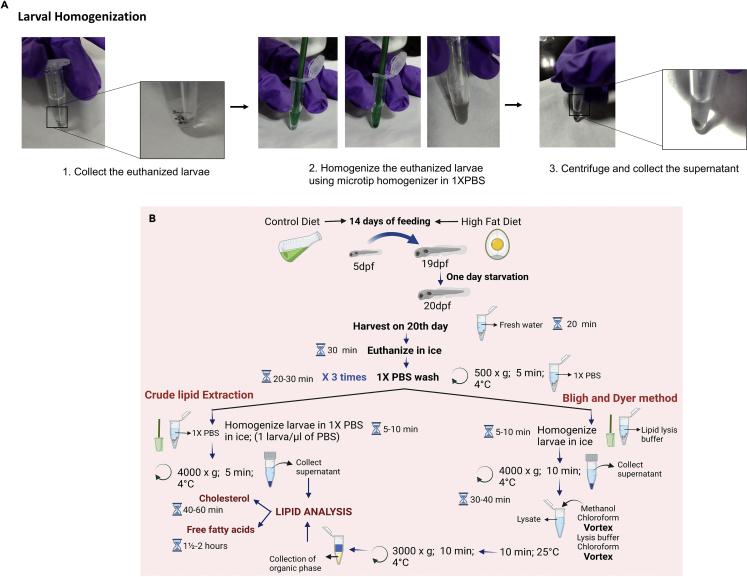

d.Incubate in ice for 10 min. Pellet the suspension via centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C (Figures 3A and 3B).

-

i.Perform homogenization till you obtain an opaque black solution devoid of any solid debris.

-

ii.Add 1× PBS in equivalent volumes to the number of larvae i.e., for 100 larvae, add 100 μL of 1× PBS.

-

i.

-

e.Collect the supernatant and measure cholesterol levels using kit from Erba (Cat. No.: BLT00034; CHOL 5 × 50) as described below.Incubate equal volume of samples (40 μL) in 100 μL of R1 buffer containing cholesterol esterase and cholesterol oxidase in a 96-well plate for 10 min at 37°C followed by absorbance measurement at 500 nm.

-

i.Allow reagent R1 to reach room temperature (20°C–25°C) prior usage.

-

ii.The measuring range of the kit is 0–600 mg/dl and its intra-assay precision is 0.9 mg/dl.

-

i.

-

f.Graph a standard curve using the purified cholesterol provided in the kit.

-

g.Derive the cholesterol levels in the samples from the standard graph (Figure 4).Note: The usage of crude extracts as samples may contain impurities that can likely impede the kit-based cholesterol measurements. Upon observations of any hindrance in assays such as high variability in duplicates, purify total lipids from zebrafish larvae using Bligh and Dyer method as follows.

-

a.

-

12.Bligh and Dyer method of lipid isolation.

-

a.Homogenize 20 dpf larvae (approx. 50 nos.) in 100 μL of lipid lysis buffer using microtube homogenizer in a 1.5 mL tube in ice.

-

b.Incubate the suspension in ice for 15 min and centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

-

c.Collect the supernatant in a fresh tube.

-

d.To the lysate, add 200 μL methanol and 100 μL chloroform and vortex gently for 30 s.

-

e.Add 100 μL of lipid lysis buffer and 100 μL of chloroform along with moderate vortexing for 30 s.

-

f.Incubate the samples at 25°C for 5–10 min.

-

g.Centrifuge at 3,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature (20°C–25°C).

-

h.Collect the organic phase and proceed for further analysis.

-

i.Store the solution in 4°C and use within 2 days for lipid estimation.

-

j.Measure total Cholesterol following manufacturer’s instructions as indicated in previous section 11. Cholesterol measurement (steps-e to -g) (Figure 4).

-

a.

-

13.HPLC mediated cholesterol estimation.

-

a.Isolate total lipids from pooled larvae (Minimum: 50 nos.) using Bligh and Dyer method.

-

b.Dry the lipid suspension using a steady N2 gas stream.

-

c.Add 2 mL of diluent [Acetonitrile (ACN): Tetrahydrofuran (THF) (70:30) v/v] into the sample vial.

-

d.Sonicate the lipid solution at ambient temperature in a sonication bath, till the lipid dissolves completely.

-

e.Transfer the lipid solution to a 5 mL volumetric flask and dilute up to the mark with diluent and mix well.

-

f.Prepare all the stock solutions and samples as stated in materials and equipment section.

-

g.Load blank solution, 5 known cholesterol solutions and both samples sequentially in the HPLC under below described HPLC conditions.

-

i.HPLC Instrument: High Performance Liquid Chromatograph equipped with Chemstation software.

-

ii.HPLC Column: Symmetry C18 75 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 μm.

-

iii.Mobile phase: The two mobile phases (1,000 mL each) were prepared as per below procedure:

-

i.

-

h.Graph a standard curve using known concentrations versus cholesterol area (troubleshooting problem 5).

-

i.Using the calibration curve, estimate the unknown concentration of cholesterol (Figure 5).

-

i.The following is an example of utilization of HPLC to measure lipid levels in 15 dpf wildtype and HFD larvae.

-

i.

-

a.

| Cholesterol (μg/mL) | Cholesterol area in HPLC |

|---|---|

| 2.5 | 75.636 |

| 5 | 149.168 |

| 10 | 294.275 |

| 15 | 422.041 |

| 20 | 577.923 |

Estimated cholesterol content

| Sample | Cholesterol area | Cholesterol (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Controlled diet fed larvae | 132.269 | 4.454 |

| (b) High fat diet fed larvae | 188.728 | 6.444 |

-

14.

Free fatty acid measurement.

Free fatty acid levels in zebrafish larvae may be measured using kit from Sigma-Aldrich (cat. No.: MAK044) as follows and the kit must be stored in −20°C.-

a.Obtain lipid sample from larvae (use minimum 50 larvae) using Bligh and Dyer method.

-

b.Dilute 40 μL of sample with 10 μL of fatty acid assay buffer (provided in the kit) to a total volume of 50 μL (in a 96-well plate).

-

c.To the sample, add 2 mL of ACS (Acyl-CoA Synthetase) reagent.

-

d.Incubate for 30 min at 37°C followed by addition of 50 mL master mix containing fluorescent fatty acid probe (2 mL), enzyme mix (2 mL) and enhancer (2 mL) with fatty acid assay buffer as the base.

CRITICAL: The fatty acid probe must be maintained in the dark and the enzyme mix must be kept in ice.

CRITICAL: The fatty acid probe must be maintained in the dark and the enzyme mix must be kept in ice. -

e.Allow the mixture to stand in dark for 30 min at 37°C along with gentle horizontal shaking (50–75 rpm).

-

f.Subsequently, measure absorbance of the solution at 570 nm in a multiplate reader.Note: The kit can detect as low as 0.2 nmoles/well.

-

g.Plot standard curve using palmitic acids of known concentrations, from which evaluate the unknown concentrations of (biological) samples (Figure 4).

-

h.To calculate the concentration of fatty acids in unknown sample, divide levels of fatty acids in the unknown sample in n-moles (obtained from standard curve) by sample volume (mL) added to reaction well.

-

a.

Figure 3.

Larval homogenization, schematic representation of lipid extraction and cholesterol/free fatty acid analysis in zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation

(A) Picture guided workflow for the homogenization of zebrafish larvae.

(B) Flowchart depiciting the steps involved in lipid extraction and analysis of cholesterol and free fatty acids in zebrafish larvae.

Figure 4.

Pictorial depiction of cholesterol and free fatty acid estimation in HFD-fed zebrafish larvae

Figure 5.

HPLC chromatograms of cholesterol standards and 15 dpf zebrafish larval samples

Zebrafish larval body length and width measurement

Timing: 45–60 min

The following steps describe a method to measure the length and width of zebrafish at larval stages which would aid us to determine minute yet significant phenotypic changes in different groups.

-

15.

Fix and wash the larvae in 4% paraformaldehyde and 1× PBS respectively as described in Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae (steps-a to -g).

-

16.

Acquire whole body images of zebrafish larvae in their transverse position in a light microscope.

CRITICAL: Do not change the focus once it is established for a single larva.

-

17.

In the same focal point, keep a measuring scale and capture the cm/mm partitions followed by imaging of rest of the larvae.

-

18.

Paste the image in a new window of ImageJ software and using straight line or free hand tool, draw a line spanning the larval mouth tip and tail tip for length measurement and draw a straight vertical line from mid of yolk sac to estimate the width (Figure 6).

-

19.

Measure the length/width of larval image in ImageJ via Analyze > set > measurements > perimeter.

-

20.

To convert the measured ImageJ value into cm/mm, draw a line using straight line tool spanning the known length of a ‘measuring scale’ image.

-

21.Use that length and its corresponding ImageJ value for conversion of the larval dimensions to cm/mm.

-

a.For example, a straight line encompassing a known length of 1.4 cm in a ‘measuring scale’ accounts for an ImageJ value of 289 arbitrary units. Using this as a reference, the ImageJ value of any length of a line can be converted into cm/mm (Figure 6).

-

a.

CRITICAL: The focal point determines the ImageJ value of the length in a scale. It is very important to not alter the focus any time after the focus is set for an experiment.

Figure 6.

Flowchart for ImageJ-based length and width measurement of zebrafish larvae

Zebrafish larval mRNA isolation and qPCR analysis

Timing: for mRNA isolation: 60–90 min; for qPCR set up and run: 3–4 h; qPCR analysis: 20–40 min

Gene quantification in zebrafish larvae using the following method would assist us to understand the metabolic changes that occur in distinct feeding groups.

-

22.

Post euthanization and washing of larvae in 1× PBS, homogenize the larvae (around 50 nos.) in 500 μL of TRIzol reagent using microtube homogenizer or via rigorous pipetting.

Note: The solution gets sticky as the larvae gets dissolved in TRIzol.

-

23.

In a chemical fume hood, add 100 μL of chloroform (0.2 volumes of TRIzol reagent).

-

24.

Securely cap the sample tubes and shake vigorously by hand for 10 s.

-

25.

Incubate the samples at room temperature (20°C–25°C) for 3 min followed by centrifugation at 11,600 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

-

26.

Upon centrifugation, the solution separates into a colorless, upper aqueous phase, an interphase and a lower red phenol-chloroform phase.

-

27.

Collect the aqueous phase where the RNA remains exclusively and add 250 μL of isopropanol (0.5 volumes of TRIzol reagent used for initial homogenization).

CRITICAL: This is the most critical step in the whole process. Place the pipette tip (20–200 μL on the brim of aqueous phase and very gently apply suction through the pipette to ensure the you do not disturb the mid-protein layer or organic layer. Any cross contamination will severely affect the purity.

-

28.

Mix by gentle inversion with hands for 10 s.

Note: Do not vortex.

-

29.

Incubate the samples for 10 min at room temperature (20°C–25°C) or at −20°C for 1 h and then centrifuge at 11,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

-

30.

Translucent gel-like pellet (RNA) appears on the bottom of the tube.

-

31.

Decant the supernatant and wash the RNA pellet with 500 μL of 75% ethanol (ice-cold) once, via centrifuging at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C.

-

32.

Give a quick spin for 10 s and try removing the remaining ethanol as much as possible using a micropipette.

-

33.

Keep the sample lid open and air dry the remaining traces of ethanol.

-

34.

Remove ethanol and re-suspend RNA in 30 μL of RNase free water by gentle pipetting followed by incubation at 60°C for 10 min.

-

35.

Gently flick the tube followed by a quick spin and store the RNA suspension in −20°C for not more than a month.

Note: Do not vortex.

-

36.

Determine the RNA concentration and quality by measuring absorption at 260 nm.

-

37.

With 1–2 μg total RNA as template, prepare cDNA using random hexamers and oligo dTs in a 20 μL reaction volume using the Superscript II First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

-

38.

Perform qPCR reactions using TB Green mix on QuantStudio5 (Applied Biosystems).

-

39.

Use gene-specific primers at a 200 nM concentration in a 20 μL reaction.

-

40.

Normalize raw Ct values of samples with Ct value of β-actin using the ΔΔCt method.

Note: Dilute the cDNAs depending on their approximate levels in cells under normal physiological conditions. For example, to assess mRNA levels of genes such as PHLPP, CD36, Fasn, ChREBP, LDLR, etc., dilute the cDNAs to 1:5 and in case of housekeeping genes such as β-Actin, GAPDH, dilute the cDNAs to 1:50 to 1:100.

-

41.

Plot relative gene expression using the control sample set as 1 and calculate the statistical significance on non-normalized and non-transformed ΔCt values.

Expected outcomes

The assays and techniques stated here are reproducible in 13–20 dpf larvae when performed as described. Subtle modifications in experimental larval age, incubation time periods etc. may have considerable effects on the outcome.

Limitations

As we perform the above-described assays in zebrafish at their larval stages, their rapid developmental process during the initial days may reflect on the reproducibility of the results, especially in qPCR analysis. Major limitations are the effect of different environmental factors on the fish growth and maintenance. Observations of severe changes in results even with small modifications in experimental conditions signify that the interpretation of data must be context specific, or it can affect the validity of the data.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Observations of larval deaths upon control diet (powdered artemia) feeding.

Refer section: Zebrafish larval model of lipid accumulation.

Potential solution

Over-feeding of powdered artemia can contaminate the water as the larvae can’t engulf much feed. Ample feeding followed by cleaning the tank everyday will reduce larval deaths. It is also advised to maintain the larvae in bigger tanks according to the larvae numbers and age (For 100 nos. of 5–15 dpf larvae, maintain in not less than 10∗19.5∗9 inches tank).

Problem 2

Observations of non-specific (dark red) Oil Red O clumps during microscopic visualization.

Refer section: Oil Red O staining of zebrafish larvae.

Potential solution

Pre-heating the Oil Red O stock solution at 56°C preferably in water bath and filtering using 0.2-micron filter prior to usage can aid in reduced non-specific staining.

Problem 3

Observations of saturated staining upon Nile red imaging.

Refer section: Nile red staining of zebrafish larvae.

Potential solution

Standardization of incubation time with the stain can avoid the intense staining. In our case, precisely 30 min of staining followed by visualization in EVOS-FL digital microscope at 1% intensity, eliminated the non-specific staining.

Problem 4

Low yield of total lipids from zebrafish larvae.

Refer section: Lipid estimation assays in zebrafish larvae.

Potential solution

To overcome this, large number of larvae (around 75 larvae) may be harvested for total lipid isolation using Bligh and Dyer method.

Problem 5

Observations of interference with the desired cholesterol peak by the blank solution during cholesterol estimation.

Refer section: HPLC mediated cholesterol estimation.

Potential solution

To avoid interference of the desired cholesterol peak by the blank solution, especially at low cholesterol concentrations, thorough washing of the HPLC column with Acetonitrile: water (80:20) for a minimum of 2 h at 1 mL/min flow rate and column equilibration by injecting the blank solution 1–2 times should be performed before sample analysis. Dilutions should be accurately prepared from one standard stock solution to avoid errors in the calibration curve.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Kishore Parsa (kishorep@drils.org).

Materials availability

The study did not generate any new materials.

Acknowledgments

K.V.L.P. and K.C. appreciate the financial support from Department of Biotechnology, India (BT/PR27445/MED/30/1962/2018). K.V.L.P. and K.C. acknowledge the insightful comments from their lab members. Graphical abstract and Figures 1, 3B, and 4 were created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

K.B., R.M.: zebrafish experiments; K.C.: zebrafish experimentation supervision and troubleshooting; P.R.: writing (HPLC portion); P.R., R.V.K.: HPLC experimentation; K.V.L.P.: overall supervision, writing, and editing.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Kiranam Chatti, Email: kiranamc@drils.org.

Kishore V.L. Parsa, Email: kishorep@drils.org.

Data and code availability

This study did not generate/analyze [datasets/code].

References

- Anderson J.L., Carten J.D., Farber S.A. In: Methods in Cell Biology. Detrich H.W. III, Westerfield M., Zon L., editors. Vol. 133. Elsevier; 2016. Using fluorescent lipids in live zebrafish larvae: from imaging whole animal physiology to subcellular lipid trafficking; pp. 165–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamurugan K., Medishetti R., Kotha J., Behera P., Chandra K., Mavuduru V.A., Joshi M.B., Samineni R., Katika M.R., Bal W.B. PHLPP1 promotes neutral lipid accumulation through AMPK/ChREBP dependent lipid uptake and fatty acid synthesis pathways. iScience. 2022;25:103766. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandaru M.K., Ranefall P., Emmanouilidou A., Tao L., Larsson A., Ledin J., Wählby C., Ingelsson E., den Hoed M. Zebrafish larvae as a model system for high-throughput screens of early-stage atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2015;132:A19716. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer B., Ernest S., Rosa F. Egr-1 induction provides a genetic response to food aversion in zebrafish. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2013;7:51. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carten J.D., Farber S.A. A new model system swims into focus: using the zebrafish to visualize intestinal lipid metabolism in vivo. Clin. Lipidol. 2009;4:501–515. doi: 10.2217/clp.09.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carten J.D., Bradford M.K., Farber S.A. Visualizing digestive organ morphology and function using differential fatty acid metabolism in live zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2011;360:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J., Karere G.M., Cox L.A., VandeBerg J.L. Animal Models of Diet-Induced Hypercholesterolemia. Sekar Ashok Kumar; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Zheng Y.-M., Zhang J.-P. Comparative study of different diets-induced NAFLD models of zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2018;9:366. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wang C.-Q., Fan Y.-Q., Xie Y.-S., Yin Z.-F., Xu Z.-J., Zhang H.-L., Cao J.-T., Han Z.-H., Wang Y., Song D.Q. Optimizing methods for the study of intravascular lipid metabolism in zebrafish. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;11:1871–1876. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Broeder M.J., Moester M.J.B., Kamstra J.H., Cenijn P.H., Davidoiu V., Kamminga L.M., Ariese F., De Boer J.F., Legler J. Altered adipogenesis in zebrafish larvae following high fat diet and chemical exposure is visualised by stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:894. doi: 10.3390/ijms18040894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L., Harkewicz R., Hartvigsen K., Wiesner P., Choi S.-H., Almazan F., Pattison J., Deer E., Sayaphupha T., Dennis E.A., et al. Oxidized cholesteryl esters and phospholipids in zebrafish larvae fed a high cholesterol diet: macrophage binding and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:32343–32351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.137257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L., Liu C., Miller Y.I. Zebrafish models of dyslipidemia: relevance to atherosclerosis and angiogenesis. Transl. Res. 2014;163:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz G.S., Reardon C.A. Animal models of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:1104–1115. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guru A., Velayutham M., Arockiaraj J. Lipid-lowering and antioxidant activity of RF13 peptide from vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 26B (VPS26B) by modulating lipid metabolism and oxidative stress in HFD induced obesity in zebrafish larvae. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2022;28:74. [Google Scholar]

- Hason M., Bartůněk P. Zebrafish models of cancer—new insights on modeling human cancer in a non-mammalian vertebrate. Genes. 2019;10:935. doi: 10.3390/genes10110935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y.-W., Tsai Y.-W., Lai H.-H., Lai C.-Y., Lin C.-Y., Her G.M. Depletion of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone induces insatiable appetite and gains in energy reserves and body weight in zebrafish. Biomedicines. 2021;9:941. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Bonneton F., Tohme M., Bernard L., Chen X.Y., Laudet V. In vivo screening using transgenic zebrafish embryos reveals new effects of HDAC inhibitors trichostatin A and valproic acid on organogenesis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Yin H., Li M., Deng Y., Ahmad O., Qin G., He Q., Li J., Gao K., Zhu J., et al. A comprehensive study of high cholesterol diet-induced larval zebrafish model: a short-time in vivo screening method for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease drugs. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019;15:973–983. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.30013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madariaga Y.G., Cárdenas M.B., Irsula M.T., Alfonso O.C., Cáceres B.A., Morgado E.B. Assessment of four experimental models of hyperlipidemia. Lab Anim. 2015;44:135–140. doi: 10.1038/laban.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison L.A., Chen W. Nutrient excess stimulates β-cell neogenesis in zebrafish. Diabetes. 2012;61:2517–2524. doi: 10.2337/db11-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martano C., Mugoni V., Dal Bello F., Santoro M.M., Medana C. Rapid high performance liquid chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry methodology for multiple prenol lipids analysis in zebrafish embryos. J. Chromatogr. A. 2015;1412:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.07.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marza E., Barthe C., André M., Villeneuve L., Hélou C., Babin P.J. Developmental expression and nutritional regulation of a zebrafish gene homologous to mammalian microsomal triglyceride transfer protein large subunit. Dev. Dyn. 2005;232:506–518. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin J.E.N., Rawls J.F. Methods in Cell Biology. Elsevier; 2011. In vivo analysis of white adipose tissue in zebrafish; pp. 63–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoa B., Figueras A. Zebrafish: model for the study of inflammation and the innate immune response to infectious diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;946:253–275. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis J.P., Farber S.A. High-fat feeding paradigm for larval zebrafish: feeding, live imaging, and quantification of food intake. J. Vis. Exp. 2016:e54735. doi: 10.3791/54735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan V.H., Farber S.A. Lipid uptake, metabolism, and transport in the larval zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2017;8:319. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlivan V.H., Wilson M.H., Ruzicka J., Farber S.A. An HPLC-CAD/fluorescence lipidomics platform using fluorescent fatty acids as metabolic tracers [S] J. Lipid Res. 2017;58:1008–1020. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D072918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler K.C., Amsterdam A., Soroka C., Boyer J., Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies the mutants vps18, nf2 and foie gras as models of liver disease. Development. 2005;132:3561–3572. doi: 10.1242/dev.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sæle Ø., Rød K.E.L., Quinlivan V.H., Li S., Farber S.A. A novel system to quantify intestinal lipid digestion and transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2018;1863:948–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoriello C., Zon L.I. Hooked! Modeling human disease in zebrafish. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2337–2343. doi: 10.1172/JCI60434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel A., Stainier D.Y.R. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein is required for yolk lipid utilization and absorption of dietary lipids in zebrafish larvae. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15179–15187. doi: 10.1021/bi0619268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlombs K., Wagner T., Scheel J. Site-1 protease is required for cartilage development in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14024–14029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2331794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada Y., Hirano M., Nishimura Y., Tanaka T. A high-throughput fluorescence-based assay system for appetite-regulating gene and drug screening. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoletov K., Fang L., Choi S.-H., Hartvigsen K., Hansen L.F., Hall C., Pattison J., Juliano J., Miller E.R., Almazan F., et al. Vascular lipid accumulation, lipoprotein oxidation, and macrophage lipid uptake in hypercholesterolemic zebrafish. Circ. Res. 2009;104:952–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts S.A., Powell M., D’Abramo L.R. Fundamental approaches to the study of zebrafi sh nutrition. ILAR J. 2012;53:144–160. doi: 10.1093/ilar.53.2.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C., Yang Q., Shen H.-M., Spitsbergen J.M., Gong Z. Chronically high level of tgfb1a induction causes both hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma via a dominant Erk pathway in zebrafish. Oncotarget. 2017;8:77096–77109. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ye L., Mueller O., Bagwell J., Bagnat M., Liddle R.A., Rawls J.F. High fat diet induces microbiota-dependent silencing of enteroendocrine cells. Elife. 2019;8:e48479. doi: 10.7554/eLife.48479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Xu Y.-Q., Guo S.-Y., Li C.-Q. Rapid analysis of hypolipidemic drugs in a live zebrafish assay. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2015;72:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze [datasets/code].