Abstract

Background

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is affected in 14% to 22% in individuals presenting with chronic low back or buttock pain. This percentage is even higher in patients who underwent lumbar fusion surgery: 32% to 42%. Currently, there is no standard treatment or surgical indication for SIJ dysfunction. When patients do not respond well to nonsurgical treatment, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (MISJF) seems to be a reasonable option. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the current literature on the effectiveness of MISJF compared to conservative management in patients with SIJ dysfunction.

Methods

A systematic search of health-care databases was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies that compared MISJF with conservative management. Primary outcome measures were pain, disability, and patient satisfaction measured by patient-reported outcome measures. Secondary outcomes were adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, financial benefits, and costs.

Results

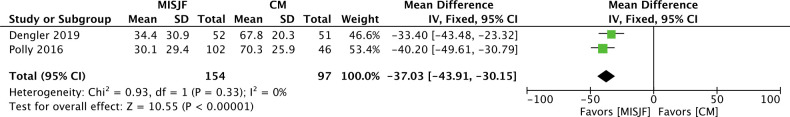

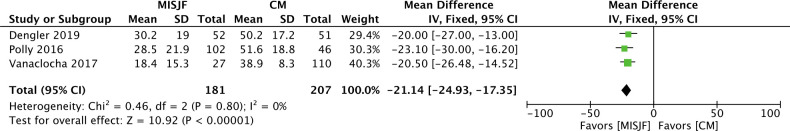

Two RCTs and one retrospective cohort study were included comparing MISJF and conservative management with regard to pain and disability outcome, encompassing 388 patients (207 conservative and 181 surgical). In a pooled mean difference analysis, MISJF demonstrated greater reduction in visual analog scale-pain score compared to conservative management: –37.03 points (95%CI [–43.91, –30.15], P < 0.001). Moreover, MISJF was associated with a greater reduction in Oswestry Disability Index outcome: –21.14 points (95% CI [–24.93, –17.35], P < 0.001). AEs were low among the study groups and comparable across the included studies. One cost-effectiveness analysis was also included and reported that MISJF is more cost-effective than conservative management.

001). AEs were low among the study groups and comparable across the included studies. One cost-effectiveness analysis was also included and reported that MISJF is more cost-effective than conservative management.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that MISJF, using cannulated triangular, titanium implants, is more effective and cost-effective than conservative management in reducing pain and disability in patients with SIJ dysfunction. Further well-powered, independent research is needed to improve the overall evidence.

Level of Evidence

1.

Keywords: sacroiliac joint, sacroiliac joint dysfunction, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, conservative management, systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

Low back or buttock pain is a common complaint in the general population. The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is increasingly being recognized as a potential cause of chronic low back and buttock pain. The SIJ is affected in 14% to 22% in individuals presenting with this pain.1,2 The frequency of SIJ dysfunction contributing to ongoing back or buttock pain is even more common following lumbar fusion surgery: 32% to 42%.3 Wide variability exists in the clinical presentation of SIJ dysfunction from localized pain around the SIJ to radiating pain into the groin or even the entire lower extremity.4 This, sometimes, makes it challenging to accurately diagnose SIJ dysfunction during physical examination. To determine the level and area of tenderness, the SIJ is palpated. There are also several provocative tests described, but their reliability is limited.5,6 This is most likely because of the limited range of motion of the joint and loading the SIJ will additionally stress surrounding structures.4 Currently, a positive diagnostic SIJ intra-articular injection is the benchmark for diagnosing SIJ dysfunction.7,8

Nonsurgical therapies for SIJ dysfunction, such as oral analgesic use, physical therapy, radiofrequency denervation, and intra-articular steroid injections, are widely propagated. They have shown limited effectiveness when it comes to durability.9–13 Return of pain 6 to 12 months following intra-articular steroid injections or radiofrequency denervation is common.13 When patients do not respond well to conservative treatment, surgical intervention is an alternative option. Currently, there is no standard surgical indication for SIJ dysfunction. Open SIJ fusion surgery has been reported in the literature since 1908.14 Open SIJ fusion is an invasive procedure, in which inevitably the surrounding anatomic structures are prone to damage. Therefore, open SIJ fusion is only moderately effective for pain relief, and no longer routinely performed for chronic SIJ dysfunction.15,16 New techniques for SIJ fusion appeared in 1980 using a posterior midline fascial splitting approach in conjunction with screws and plates to facilitate the joint to fuse.17 Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion (MISJF) systems are now available and potentially have better outcomes in relation to pain, disability, and quality of life than the open techniques.18,19 Multiple techniques and systems for MISJF are available and described in the current literature.

Systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses on MISJF compared to conservative management for SIJ dysfunction in relation to outcome are lacking. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to evaluate the current literature and to determine the effectiveness of MISJF compared to conservative management in patients with SIJ dysfunction.

Methods

This systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42020183360) and conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.20,21 The research question was formulated as follows:

Is MISJF in adults with low back and/or buttock pain as a result of SIJ dysfunction more effective than conservative management with regard to reduction of pain and disability?

Eligibility Criteria

The review was limited to studies that were published in the English language, and all selected studies had to be published as full-text articles. The last search was run in March 2021.

Inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or comparative cohort studies that compared MISJF with conservative management for patients aged 18 years or older. The included studies needed to provide sufficient data relating to all or part of the following outcome criteria: pain, functional outcome, and patient satisfaction measured by patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).22–24 Secondary outcomes of adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), and readmission rates were collected if provided. In the MISJF group, the readmission rate was calculated as the number of hospital readmissions after the index surgery divided by the number of index surgeries. Because AEs, SAEs, and readmission rates are interrelated in clinical practice, they were interpreted separately as well as together. Other secondary outcomes were financial benefits and costs.

Search

A systematic search of databases PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Clinical Trials, World Health Organization, Trial Registry Portal, and PROSPERO was conducted. A detailed search description is included in the appendix; supplementary item 1. Relevant clinical studies were selected and reviewed. Full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria, based on their title and abstract, were reviewed for further analysis. Articles identified through the reference list were considered for data collection based on their title. First 2 independent reviewers (S.H. and R.D.) analyzed the articles by title and abstract. Second, the full-text papers were analyzed independently considering the inclusion criteria. Inter-reviewer disagreements were solved by consensus and with assistance of a third reviewer (I.C.).

IJSS-16-03-8241supp001.docx (19.4KB, docx)

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment of the included studies was performed by 2 reviewers (S.H. and R.D) independently.

In case of RCTs, the bias assessment tool of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was consulted.25 Based on six different domains (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients, clinician and outcome assessor, incomplete outcomes data, and selective outcomes data), the included RCTs were evaluated and scored a “low,” “high,” or “unclear” risk of bias (ROB).

The Cochrane Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to appraise the quality of selected nonrandomized studies.26 Central features of ROBINS-I include the use of signaling questions to guide ROB judgments within 7 bias domains. These domains were evaluated and scored with “low,” “moderate,” or “serious” ROB.

Methodological quality of economic evaluations was analyzed using The Consensus Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list.27 Levels of evidence were determined using the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence tool (2011).28

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of the study data were performed using Review Manager (RevMan v5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).29 Calculations were performed using random effects, fixed effects, mean difference, and a 95% CI. P values ≤0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The I 2-test for heterogeneity was conducted to assess variability between studies. Heterogeneity was regarded as low with an I 2 ≤ 50%, moderate with an 50% < I 2 < 75% and high with an I 2 ≥ 75%.

Results

Study Selection

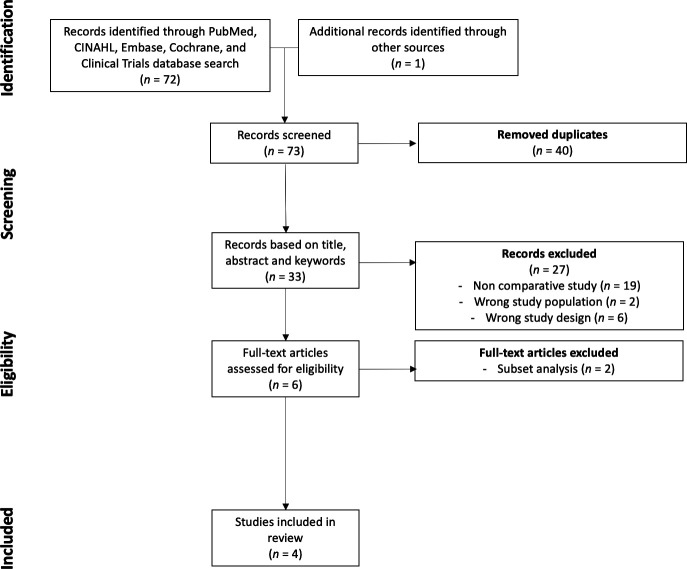

The systematic search (March 2021) in the databases yielded 73 articles, 33 of which remained after removal of duplicates. A total of 6 studies were selected for full-text reading. Two studies were rejected for final analysis because they were subset analyses of other included studies.30,31 Thus, 4 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis of which 3 studies were included in the quantitative synthesis.32–34 A PRISMA flowchart detailing the search is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Study Characteristics

Two RCTs, 1 retrospective cohort study and 1 cost-effectiveness analysis were included in this review. The total sample size of the RCTs and cohort study consisted of 388 patients of whom 207 were treated conservatively and 181 were treated with MISJF. In all studies, SIJ dysfunction was confirmed with the occurrence of at least 50% pain relief following image-guided intra-articular injection of local anesthetic. In the conservative management group, 63% of patients were women, with a mean age of 49.9 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 29.0 kg/m2. In the MISJF group, 72% were women, with a mean age of 49.2 years and a mean BMI of 28.8 kg/m2. Publication years ranged from 2016 to 2019. Three studies were conducted in the United States and one in Spain.

The studies from Polly et al32 and Dengler et al33 were RCTs comparing outcomes after MISIJF vs conservative management for chronic SIJ dysfunction. Polly et al allowed crossover from conservative management to MISJF after 6 months. Vanaclocha et al34 performed a retrospective comparative cohort study to determine responses to conservative management, including SIJ denervation and MISJF. For PROMS, the visual analog scale (VAS)-pain and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) were implemented in the conservative and surgical-treated groups in all 3 studies. Patient satisfaction documented through Short Form (SF)-36 questionnaire was determined in the study by Polly et al. All 3 studies used cannulated triangular, titanium implants with a porous surface for lateral transiliac SIJ fusion (iFuse Implant System, SI-BONE, Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).

The cost-effectiveness analysis performed by Cher et al35 used quality of life and health-care utilization findings from different ongoing RCTs on MISJF vs conservative management.30,31 These data provided estimates of variation in health-care utilization in both MISJF and conservative management. The study implemented a model to determine expected costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) associated with each treatment based on total time spent in different health states (eg, postsurgical mild SIJ pain or postsurgical severe SIJ pain). A relative cost-effectiveness and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) were also determined with these data. The studies included in the analysis by Cher et al used data from the same subsets that were used in the RCTs that were included in this systematic review.32,33 Patient and study characteristics of the included literature are outline in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Study Design | Minimally Invasive Sacroiliac Joint Fusion Group | Conservative Management Group | Follow-Up (mo) | Quality Assessment | |||

| Participants, n (% Women) | Age, y, mean (Range) | Participants, n (% Women) | Age, y, mean (Range) | Level of Evidence | Overall risk of bias | |||

| Polly et al, 2016 | Randomized controlled trial | 102 (73.5%) | 50.2 (25.6 to 71.7) | 46 (60.9%) | 53.8 (29.5 to 71.1) | 24 | 1 | Low |

| Dengler et al, 2019 | Randomized controlled trial | 52 (73.1%) | 49.4 (27 to 70) | 51 (72.5%) | 46.7 (23 to 69) | 24 | 1 | Low |

| Vanaclocha et al, 2017 | Retrospective comparative cohort | 27 (70.4%) | 48.0 (25 to 69) | 110 (55.2%) | 49.7 (24 to 70) | 72 | 4 | Moderate |

| Cher et al, 2016 | Cost-effectiveness analysis | 274 | – | 46 | – | 12 | – | – |

Quality Assessment

The ROB was evaluated for the included studies. The RCTs from Dengler et al33 and Polly et al32 scored an overall low ROB. Only risk of performance bias was high in both studies because patients or investigators were blinded. Vanaclochaet al.34 scored an overall moderate ROB, which was expected because of its retrospective nature. Noteworthy, the studies by Dengler et al, Polly et al, and Cher et al were funded by SI-BONE, the manufacturer of the iFuse implant system. Industry funding is not implemented in the bias assessment tool of Cochrane.

Quality of the included cost-effectiveness analysis by Cher et al35 was high according to the CHEC-list. With a score of 17 out of 19, only “generalization” and “ethical issues” were domains insufficiently discussed in the paper. A full elaboration of the methodological quality assessment is included as supplementary item 2 in the appendix.

Results of Studies

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of the included studies with regard to VAS-pain and ODI. Polly et al,32 Dengler et al,33 and Vanaclocha et al34 compared VAS-pain outcome in patients who underwent MISJF compared with patients who were treated conservatively. All 3 found a statistically significant difference in favor of the MISJF groups, respectively, 38.2 and 34.0 points on a 0 to 100 scale and 6.0 points on a 0 to 10 scale. Similarly, statistically significant ODI differences were reported in favor of the MISJF groups, respectively, 23.8, 18.0, and 24.0 points. Only Polly et al reported on changes in SF-36. A statistically significant improvement in SF-36 was noted within the MISJF group at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively, 12.5, 12.8, and 11.2 points. While the mean SF-36 score of the conservative management group at 6 months remained low at 3.9 points. This difference between treatment groups was statistically significant. The crossover rate in Polly et al from conservative management to MISJF at 6 months was 89%.

Table 2.

Study results for mean (SD) VAS-pain score.

| Study | VAS-Pain MISJF Group, mean (SD) | VAS-Pain CM Group, mean (SD) | VAS-Pain Improvement Comparison Between Groupsa | |||

| Preop | Postop(6 mo) | Postop(24 mo) | Preop | Postop(6 mo) | ||

| Polly et al, 2016 | 82.3 (11.9) | 30.1 (29.4) | 26.5 (29.8) | 82.2 (9.9) | 70.3 (25.9) | 38.2 (P < 0.0001) |

| Dengler et al, 2019 | 77.7 (11.3) | 34.4 (23.9) | 31.8 (29.8) | 73.0 (13.8) | 67.8 (20.3) | 34 (P < 0.0001) |

| Vanaclocha et al, 2017 | 7.8 (1.4) | 2.4 (1.1) | 1.6 (0.8) | 7.5 (1.4) | 7.2 (1.8) | 6 (P < 0.001) |

VAS-pain improvement in the MISJF group compared to the CM group (combining timepoints).

CM; conservative management, MISJF, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion; Postop, postoperative; Preop, preoperative; VAS-pain; visual analog scale for pain.

Table 3.

Study results for mean (SD) ODI.

| Study | ODI MISJF Group, mean (SD) | ODI CM Group, mean (SD) | ODI Improvement Comparison Between Groups | |||

| Preop | Postop(6 mo) | Postop(24 mo) | Preop | Postop(6 mo) | ||

| Polly et al, 2016 | 57.2 (12.8) | 29.9 (20.5) | 28.5 (21.9) | 56.0 (14.0) | 51.6 (18.8) | 23.8 (P < 0.0001) |

| Dengler et al, 2019 | 57.5 (14.4) | 32.0 (18.4) | 30.2 (19.0) | 55.6 (13.7) | 50.2 (17.2) | 18 (P < 0.0001) |

| Vanaclocha et al, 2017 | 41.7 (6.8) | 25.2 (5.7) | 18.4 (5.3) | 38.3 (7.9) | 38.9 (8.3) | 24 (P < 0.001) |

ODI improvement in the MISJF group compared to the CM group (combining timepoints).

CM; conservative management, MISJF, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion; ODI; Oswestry Disability Index; Postop, postoperative; Preop, preoperative.

Adverse Events

All studies reported on AEs/SAEs. A total of 81 AEs/SAEs occurred in a total study population of 341 patients. Fifty AEs/SAEs occurred in the MISJF study groups, and 31 AEs occurred in the conservative management groups. Furthermore, 17 failures in treatment were mentioned, 11 in the MISJF groups, and 6 in the conservative management groups. No statistically significant differences were reported regarding the rate of AEs across MISJF groups and conservative management groups. Failure to treatment was regarded as recurrent SIJ pain after surgery or persistent or increased pain after conservative management.

Of the 50 AEs related to MISJF, 10 were regarded as SAEs, including surgical wound problems (n = 5) and implant malposition (n = 5). Implant malposition caused persistent radicular pain because of nerve root impingement in 2 patients and persistent SIJ pain in 1 patient. All 3 required readmission with revision surgery, repositioning the implant. Revision surgery was effective in all 3 cases. Recurrent SIJ pain after surgery occurred in 11 patients and was considered as failure to treatment. Other AEs reported in the studies included trochanteric bursitis, urinary retention, nausea/vomiting and atrial fibrillation.

Of the 31 AEs related to conservative management, 0 were rated as serious. The following AEs were probably related to conservative management: new pain in the pelvic area (n = 5), new low back pain (n = 4), SIJ pain due to physiotherapy (n = 1), back pain due to physiotherapy (n = 1), SIJ pain related to a steroid injection (n = 1), and flushing and shortness of breath related to a SIJ steroid injection (n = 1). Failure to treatment occurred in 6 patients: persistent SIJ pain (n = 1) and worsening of SIJ pain (n = 5). Other AEs reported in the studies included hypertensive crisis, herpes infection, depression, carpal tunnel syndrome, stress incontinence, menometrorrhagia, medication overdose, cervicobrachialgia, worsening ulcerative colitis, and brain metastases.

Cost-Effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness analysis performed by Cher et al35 reported that MISJF was associated with an average 5-year total cost per patient of US $22,468 (95% CI $17,215–$27,888). The average 5-year total cost of conservative management in SIJ dysfunction was US $12,615 (95% CI $10,336–$15,065). The incremental cost of MISJF relative to conservative management was $9833 with an incremental QALY gain of 0.74 per year at a corresponding ICER of $13,313 per QALY gained.

Meta-Analysis

Data reported by Polly et al,32 Dengler et al33, and Vanaclocha et al34 were used to perform a meta-analysis. For the meta-analysis of VAS-pain, only data from Polly et al and Dengler et al were analyzed, as Vanaclocha et al reported VAS-pain on a 0 to 10 scale while Polly et al and Dengler et al used a 0 to 100 scale.

Baseline scores for VAS-pain and ODI across MISJF and conservative management groups were similar. An outcome timepoint of 6 months for both study groups was implemented. Study heterogeneity was low for VAS-pain and ODI with an I 2 of 0% for both fixed and random effects analysis. The overall effect for VAS-pain outcome was in favor of the MISJF group with a statistically significant mean difference of –37.03 points (95% CI [–43.91, –30.15], P < 0.001). The overall effect for ODI outcome was also in favor of the MISJF group with a statistically significant mean difference of –21.14 points (95% CI [–24.93, –17.35], P < 0.001). Forest plots are included as Figures 2 and 3 in the figure legend.

Figure 2.

Comparison between MISJF and CM for the outcome of VAS-pain after 6 mo; CI, confidence interval; CM, conservative management; MISJF, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion; VAS, visual analog scale.

Figure 3.

Comparison between MISJF and CM for the outcome of ODI after 6 mo; CI, confidence interval; CM, conservative management; MISJF, minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index.

Discussion

The most important findings of the present systematic review and meta-analysis are that MISJF, using lateral transiliac approach with cannulated triangular, titanium implants, suggests to be more effective in reducing pain and disability in patients with SIJ dysfunction compared to conservative management. Also, MISJF suggests to be cost-effective when compared to the current conservative treatment options. The included studies reported statistically significant differences in clinical outcome in favor of the MISJF groups.32–34 The decrease reported in the included studies of VAS-pain and ODI after MISJF is clinically relevant, as the VAS-pain reduction is 50.9 points and the decrease in ODI is 26.4 points.36,37 There were no statistically significant or clinically relevant improvements of VAS-pain and ODI in conservatively treated patients. Furthermore, the crossover rate of 89% in Polly et al from conservative management to MISJF also indicates high ineffectiveness of conservative management. Quantitative analysis for VAS-pain and ODI outcomes across included studies revealed a homogeneous trend with an I 2 of 0% across analyses (Figures 2 and 3).32–34 This trend is also demonstrated in the qualitative analysis of this paper. Whang et al31 was excluded in the quantitative analysis of VAS-pain, as it reported VAS-pain on a 0 to 10 scale, introducing statistical heterogeneity.

The studies by Polly et al32 and Dengler et al33 had a follow-up of 24 months for the MISJF groups and 6 months for the conservative management groups, with the notion that no further improvement in terms of pain and disability is to be expected after 6 months of conservative management.38 Vanaclocha et al.34 had a follow-up of up to 72 months for both MISJF and conservative treated patients. The MISJF groups across included studies continued to show significant improvements in VAS-pain and ODI scores up to 24 months and even 72 months after surgery. These data suggest that the positive effects from MISJF are still present in the long term.

Meta-analysis was not implemented to summarize AEs/SAEs across included studies, as the methods to collect these events were not detailed. The rate of AEs reported in the surgical and conservative management groups was low and consistent among the included studies with no significant differences between groups. SAEs were uncommon and occurred in 5 surgical patients, all being implant malpositioning. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that correct placement of the implants across the SIJ is a difficult procedure with a long learning curve.39 Nonetheless, the overall positive outcomes of MISJF seem to outweigh the potential SAEs. These findings are supported by 2 previously performed safety analyses.40,41

With an incremental cost of $9833 for MISJF compared to conservative management and an addition of 0.74 QALY, Cher et al35 concluded that MISJF is a cost-effective, and, in the long run, a cost-saving approach for SIJ dysfunction. The cost-effectiveness is comparable to that of total hip and knee arthroplasty. A recent administrative claims analysis reported lower postoperative low back pain-related health-care costs compared to preoperative costs for MISJF.42 The study was not included in this systematic review, as it did not compare MISJF with conservative management. These findings also support the financial benefits of MISJF for patients with chronic SIJ dysfunction.

In current systematic reviews that solely evaluate the effectiveness of MISJF in patients suffering from SIJ dysfunction, different implant systems are described and clustered.43,44 When all data are pooled, a statistically significant reduction in VAS-pain can be observed. However, the effectiveness of different implant systems varies across the current literature. Multiple trials investigated the efficacy of cannulated triangular, titanium implants, with clinically significant differences in pain and disability.45–50 For other systems, such as titanium cages and hollow modular screws, significantly less evidence in the literature is available.51 The evidence supporting the latter systems comes mostly from small prospective or retrospective case series; therefore, these studies are of lesser methodological quality.52–55

As mentioned before, several studies describe significant improvements in clinical outcome following MISJF.45–50 Most of these studies did not meet our inclusion criteria as they did not compare the outcomes to a conservative management group. Statistically significant improvements in VAS-pain and ODI are reported in these studies with a mean follow-up of 20 months. Although the differences in pre- and postoperative VAS-pain and ODI are clinically relevant, it is reported that in some patients not all pain and disability resolved after surgery. Across studies, 77.1% to 93.8% of patients were satisfied after surgery and 88.4% to 91.7% of patients would have the same surgery again.45–49 These results suggest that a small number of patients do not respond adequately to surgery or expected more improvement in pain and disability. It can be postulated that wrong indications or other patient-related factors, such as patient expectations, are of influence on the outcome, which is commonly encountered in other surgical procedures.56

Limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis are bound by several important limitations in the available literature. Exploration of the literature indicated a limited availability of studies that met the strict inclusion criteria. Furthermore, only 1 SIJ fusion technique was implemented in the included studies, a lateral transiliac approach with cannulated triangular, titanium implants. Research on MISJF is performed by only a few research departments across the world, as a result many overlapping cohorts are published in the current literature.30,31 Although the sample sizes are generally small, we were able to perform a meta-analysis with the included data. According to Greco et al,57 performing a meta-analysis with a small number of studies can still provide useful insights. Because of homogeneity in reported results in included studies, we chose to compute the pooled estimates of differences between MISJF and conservative management, resulting in an I 2 of 0% across all analyses. For the meta-analysis of VAS-pain only data from Polly et al32 and Dengler et al33 were analyzed, as Vanaclocha et al34 reported VAS-pain on a different scale. Although most of the outcome measurements are validated tools, they remain PROMs and are thereby at risk for some sort of subjective discrepancies. A validated objective outcome measurement in SIJ dysfunction for diagnostic, as well as evaluative purposes, is currently lacking.

In the study by Vanaclocha et al, all patients were initially treated conservatively. When conservative treatment failed, patients with a positive response to SIJ intra-articular injection were enrolled in prolonged conservative management or MISJF. In the studies by Polly et al and Dengler et al, it remains unclear whether patients already underwent conservative treatment before enrolling in the randomized trial.

Finally, even though the ROB of the included studies was low to moderate, 3 out of the 4 included studies were funded by SI-BONE, the manufacturer of the iFuse implant system, potentially introducing bias into the reporting of results.

As a result of these limitations, the outcomes of this review and meta-analysis should be interpreted with some caution.

Conclusions

This article is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of MISJF, using cannulated triangular, titanium implants, compared with conservative management for SIJ dysfunction. Although the level of evidence is limited, mostly due to small sample sizes, based on the assessment of the included studies, MISJF suggests to be more (cost-)effective in reducing pain and disability in patients with SIJ dysfunction compared to conservative management. More data are required from well-powered, independent, RCTs with validated outcome measurements to make undisputed conclusions about the efficacy and financial benefits of various MISJF implants compared to conservative management. This review could function as a base for these particular trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Vanaclocha from the University of Valencia and Dr. Cher and Dr. Polly from SI-BONE, California, for providing us with essential data to include a meta-analysis in this article, improving the scientific evidence.

References

- 1.Bernard TN, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. Recognizing specific characteristics of nonspecific low back pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(217):266–280. 10.1097/00003086-198704000-00029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sembrano JN, Polly DW. How often is low back pain not coming from the back? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(1):E27-32. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818b8882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YC, Lee R, Harman C. The incidence of new onset sacroiliac joint pain following lumbar fusion. J Spine Surg. 2019;5(3):310–314. 10.21037/jss.2019.09.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thawrani DP, Agabegi SS, Asghar F. Diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(3):85–93. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szadek KM, van der Wurff P, van Tulder MW, Zuurmond WW, Perez R. Diagnostic validity of criteria for sacroiliac joint pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2009;10(4):354–368. 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simopoulos TT, Manchikanti L, Singh V, et al. A systematic evaluation of prevalence and diagnostic accuracy of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3):E305-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang CW, Hung SK, Pan PT, Kao MC. Diagnosis and interventional pain management options for sacroiliac joint pain. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;31(4):207–210. 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_54_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simopoulos TT, Manchikanti L, Gupta S, et al. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic effectiveness of sacroiliac joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2015;18(5):E713-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiker WR, Lawrence BD, Raich AL, Skelly AC, Brodke DS. Surgical versus injection treatment for injection-confirmed chronic sacroiliac joint pain. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2012;3(4):41–53. 10.1055/s-0032-1328142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson R, Porter K. The pelvis and sacroiliac joint: physical therapy patient management using current evidence. In: Current Concepts of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy. Publisher unknown; 2016. 10.17832/isc.2016.26.2.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luukkainen RK, Wennerstrand PV, Kautiainen HH, Sanila MT, Asikainen EL. Efficacy of periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint in non-spondylarthropathic patients with chronic low back pain in the region of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20(1):52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel N. Twelve-month follow-up of a randomized trial assessing cooled radiofrequency denervation as a treatment for sacroiliac region pain. Pain Pract. 2016;16(2):154–167. 10.1111/papr.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luukkainen R. Periarticular corticosteroid treatment of the sacroiliac joint. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2007:155–157. 10.2174/157339707780619449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Painter CF. Excision of the os innominatum; arthrodesis of the sacro-iliac synchondrosis. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 1908;159(7):205–208. 10.1056/NEJM190808131590703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kibsgård TJ, Røise O, Stuge B. Pelvic joint fusion in patients with severe pelvic girdle pain - a prospective single-subject research design study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:85. 10.1186/1471-2474-15-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchowski JM, Kebaish KM, Sinkov V, Cohen DB, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP. Functional and radiographic outcome of sacroiliac arthrodesis for the disorders of the sacroiliac joint. Spine J. 2005;5(5):520–528. 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belanger TA, Dall BE. Sacroiliac arthrodesis using a posterior midline fascial splitting approach and pedicle screw instrumentation: a new technique. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14(2):118–124. 10.1097/00002517-200104000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran ZV, Ivashchenko A, Brooks L. Sacroiliac joint fusion methodology - minimally invasive compared to screw-type surgeries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2019;22(1):29–40. 10.36076/ppj/2019.22.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith AG, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. Open versus minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: a multi-center comparison of perioperative measures and clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):14. 10.1186/1750-1164-7-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiavo JH. PROSPERO: an international register of systematic review protocols. Med Ref Serv Q. 2019;38(2):171–180. 10.1080/02763869.2019.1588072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nahler G, Nahler G. visual analogue scale (VAS). Dictionary of Pharmaceutical Medicine. 2009. 10.1007/978-3-211-89836-9_1450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairbank JCT, Pynsent PB. The oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2940–2952. 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36).conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Cochrane Book Series. 2008. 10.1002/9780470712184.ch8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–245. 10.1017/s0266462305050324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durieux N, Pasleau F, Howick J, OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group . The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence. 2011.

- 29.Manager (RevMan) . Cochrane Community. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polly DW, Cher DJ, Wine KD, et al. Randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants vs nonsurgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction: 12-month outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(5):674–690; . 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whang P, Cher D, Polly D, et al. Sacroiliac joint fusion using triangular titanium implants vs. non-surgical management: six-month outcomes from a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Spine Surg. 2015;9:6. 10.14444/2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polly DW, Swofford J, Whang PG, et al. Two-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion vs. non-surgical management for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:28. 10.14444/3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dengler J, Kools D, Pflugmacher R, et al. Randomized trial of sacroiliac joint arthrodesis compared with conservative management for chronic low back pain attributed to the sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(5):400–411. 10.2106/JBJS.18.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanaclocha V, Herrera JM, Sáiz-Sapena N, Rivera-Paz M, Verdú-López F. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion, radiofrequency denervation, and conservative management for sacroiliac joint pain: 6-year comparative case series. Neurosurgery. 2018;82(1):48–55. 10.1093/neuros/nyx185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cher DJ, Frasco MA, Arnold RJG, Polly DW. Cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:1–14. 10.2147/CEOR.S94266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):424–429. 10.1093/bja/aew466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Copay AG, Glassman SD, Subach BR, Berven S, Schuler TC, Carreon LY. Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the oswestry disability index, medical outcomes study questionnaire short form 36, and pain scales. Spine J. 2008;8(6):968–974. 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abd-Elsayed A. Pain. Cham: Springer; 2019. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-99124-5. 10.1007/978-3-319-99124-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herseth J, Ledonio C, Polly DW. A CT-based analysis of implant position of sacroiliac joint fusion: is there a learning curve for safe placement? Global Spine Journal. 2017;6(1_suppl):s-0036. 10.1055/s-0036-1583109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller LE, Reckling WC, Block JE. Analysis of postmarket complaints database for the iFuse SI joint fusion system®: a minimally invasive treatment for degenerative sacroiliitis and sacroiliac joint disruption. Med Devices (Auckl). 2013;6:77–84. 10.2147/MDER.S44690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cher DJ, Reckling WC, Capobianco RA. Implant survivorship analysis after minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using the iFuse implant system(®). Med Devices (Auckl). 2015;8:485–492. 10.2147/MDER.S94885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buysman EK, Halpern R, Polly DW. Sacroiliac joint fusion health care cost comparison prior to and following surgery: an administrative claims analysis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:643–651. 10.2147/CEOR.S177094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heiney J, Capobianco R, Cher D. A systematic review of minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion utilizing a lateral transarticular technique. Int J Spine Surg. 2015;9:40. 10.14444/2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin CT, Haase L, Lender PA, Polly DW. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: the current evidence. Int J Spine Surg. 2020;14(Suppl 1):20–29. 10.14444/6072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duhon BS, Bitan F, Lockstadt H, et al. Triangular titanium implants for minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: 2-year follow-up from a prospective multicenter trial. Int J Spine Surg. 2016;10:13. 10.14444/3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cummings J, Capobianco RA. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: one-year outcomes in 18 patients. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):12. 10.1186/1750-1164-7-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sachs D, Capobianco R, Cher D, et al. One-year outcomes after minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion with A series of triangular implants: a multicenter, patient-level analysis. Med Devices (Auckl). 2014;7:299–304. 10.2147/MDER.S56491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kancherla VK, McGowan SM, Audley BN, Sokunbi G, Puccio ST. Patient reported outcomes from sacroiliac joint fusion. Asian Spine J. 2017;11(1):120–126. 10.4184/asj.2017.11.1.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolf L. Sacroiliac joint arthrodesis-MIS technique with titanium implants: report of the first 50 patients and outcomes. Open Orthop J. 2012;6:495–502. 10.2174/1874325001206010495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schroeder JE, Cunningham ME, Ross T, Boachie-Adjei O. Early results of sacro-iliac joint fixation following long fusion to the sacrum in adult spine deformity. HSS J. 2014;10(1):30–35. 10.1007/s11420-013-9374-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whelan R, Duhon B. The evidence for sacroiliac joint surgery. Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2019;34(2):87–95. 10.1097/BTO.0000000000000367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cross WW, Delbridge A, Hales D, Fielding LC. Minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion: 2-year radiographic and clinical outcomes with a principles-based SIJ fusion system. Open Orthop J. 2018;12:7–16. 10.2174/1874325001812010007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kube RA, Muir JM. Sacroiliac joint fusion: one year clinical and radiographic results following minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion surgery. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:679–689. 10.2174/1874325001610010679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Khayer A, Hegarty J, Hahn D, Grevitt MP. Percutaneous sacroiliac joint arthrodesis: a novel technique. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(5):359–363. 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318145ab96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khurana A, Guha AR, Mohanty K, Ahuja S. Percutaneous fusion of the sacroiliac joint with hollow modular anchorage screws: clinical and radiological outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(5):627–631. 10.1302/0301-620X.91B5.21519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunaratnam C, Bernstein M. Factors affecting surgical decision-making-a qualitative study. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2018;9(1). 10.5041/RMMJ.10324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greco T, Zangrillo A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Landoni G. Meta-analysis: pitfalls and hints. Hear lung Vessel. 2013;5:219–225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

IJSS-16-03-8241supp001.docx (19.4KB, docx)