Abstract

Involvement of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (SZ) is suggested by studies of peripheral tissue. Nonetheless, it is unclear how such biological changes are linked to relevant, pathological neurochemistry, and brain function. We designed a multi-faceted study by combining biochemistry, neuroimaging, and neuropsychology to test how peripheral changes in a key marker for oxidative stress, glutathione (GSH), may associate with central neurochemicals or neuropsychological performance in health and in SZ. GSH in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) was acquired as a secondary 3T 1H-MRS outcome using a MEGA-PRESS sequence. Fifty healthy controls and 46 patients with SZ were studied cross-sectionally, and analyses were adjusted for effects of confounding variables. We observed lower peripheral total GSH in SZ compared to controls in extracellular (plasma) and intracellular (lymphoblast) pools. Total GSH levels in plasma positively correlated with composite neuropsychological performance across the total population and within patients. Total plasma GSH levels were also positively correlated with the levels of Glx in the dACC across the total population, as well as within each individual group (controls, patients). Furthermore, the levels of dACC Glx and dACC GSH positively correlated with composite neuropsychological performance in the patient group. Exploring the relationship between systemic oxidative stress (in particular GSH), central glutamate, and cognition in SZ will benefit further from assessment of patients with more varied neuropsychological performance.

Introduction

Oxidative stress, resulting from imbalance of reduction-oxidation (redox) homeostasis, has historically been suggested to be involved in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (SZ) [1-4]. Glutathione (GSH) is a key intracellular antioxidant and altered levels of GSH may play a role in aberrant redox balance in SZ [5, 6]. Many of these early studies are limited, however, by small sample sizes and the confounding effects of medication and duration of illness that were not considered in prior analyses.

Recent comprehensive reviews and meta-analysis have attempted to address these concerns [5, 7-9], and provide evidence that key mediators of oxidative stress may be changed in peripheral tissues of patients with SZ. Alterations in such mediators are seen in recent-onset cases even with minimal to no exposure to medication, suggesting that these changes may reflect disease-associated intrinsic traits rather than secondary effects of confounding factors [7]. For example, GSH is lower relative to controls in plasma [10-14], serum [15-18], and erythrocytes [19, 20] isolated from patients with SZ. Studies using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) to quantify GSH indirectly in the brains of patients have resulted in more conflicting results [21-33], although the methodology of the measurement has been refined [27, 30]. Although GSH may not directly pass the blood-brain barrier, levels of brain and peripheral GSH have been correlated in both wild-type and mutant mouse models with impaired biosynthesis of GSH [e.g., excitatory amino acid transporters 1 (eaac1) knockout mice] [34]. Thus, peripheral GSH may prove a useful, indirect indicator of redox status or oxidative stress in the brain.

Recent studies using rodent models with SZ-relevant behaviors demonstrate excess oxidative stress in the forebrain [35, 36] that raise questions about the molecular links between redox imbalance and SZ [24, 33, 37-40]. An outstanding question is whether and how redox imbalance in the brain and body may be related to glutamatergic neurotransmission and cognitive deficits, which are critical neurobiological and psychological hallmarks of SZ. GSH, a tripeptide that includes glutamate, has been proposed as a reservoir of glutamate [41, 42], and the GSH cycle shapes synaptic glutamate activity at least in cell and animal models [43]. If this molecular association is validated further, redox imbalance and excess oxidative stress may directly underlie aberrant glutamatergic neurotransmission in SZ pathophysiology.

In the present study, we examined levels of GSH in peripheral tissues of SZ patients and healthy controls, with focus on biochemical measurement of total GSH levels in both extracellular and intracellular pools (plasma and lymphoblasts respectively). We then examined the relationship between plasma total GSH levels and 1) neuropsychological performance as well as 2) the level of Glx (the sum of glutamate and glutamine) in the dorsal ACC (dACC) that was assessed using 1H-MRS at 3-Tesla (3T). The ACC was chosen as our region of interest since it serves a critical role in neurocognitive function [44] and aberrant glutamatergic measures in the overlapping regions of medial prefrontal cortex and ACC have been found in SZ [45, 46]. Our design adjusted for treatment and other potential confounding factors that may account for variability in prior results from evaluating Glx in this region in SZ. For example, some have reported higher Glx measures in unmedicated patients with SZ relative to controls, whereas chronic, medicated patients may have lower Glx [45-48]. We focused on peripheral GSH and central Glx because systemic oxidative stress and aberrant glutamatergic neurotransmission likely play a key role in the pathophysiology of SZ [1-3, 41, 42, 45, 46]. As a secondary measure, GSH in the dACC using edited 1H-MRS spectra at 3T and its relationship to the primary measures (plasma total GSH, neuropsychological performance, and dACC Glx) was assessed in health and in SZ.

Methods

Participants and clinical/neuropsychological characterization

This study was approved by a Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Adult patients with SZ and healthy control individuals were recruited from the greater Baltimore-Washington, D.C. area. All participants completed a two-hour battery of neuropsychological tests to assess cognitive function in five dimensions, namely processing speed, verbal memory, visuospatial memory, ideational fluency, and executive function, as previously described [49, 50]. Investigators were blinded to the grouping of participants during data collection. Further details regarding the recruitment, inclusion/exclusion criteria, clinical characterization, and neuropsychological assessment of the study participants are in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1).

Measurement of GSH in peripheral tissues

Peripheral whole blood samples were collected from each participant. Total GSH (the sum of GSH and glutathione disulfide, GSSG) was measured in both plasma and lymphoblasts using modifications of the Tietze method [41, 51]. Methods related to plasma and lymphoblast isolation/transformation and further description of the Tietze method are in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Methods). The concentration of total GSH in lymphoblasts was normalized to total protein concentration. Total GSH in plasma was measured relative to plasma volume (nmol /ml). In the present manuscript, we herein describe total GSH as GSH.

MR acquisition and analysis

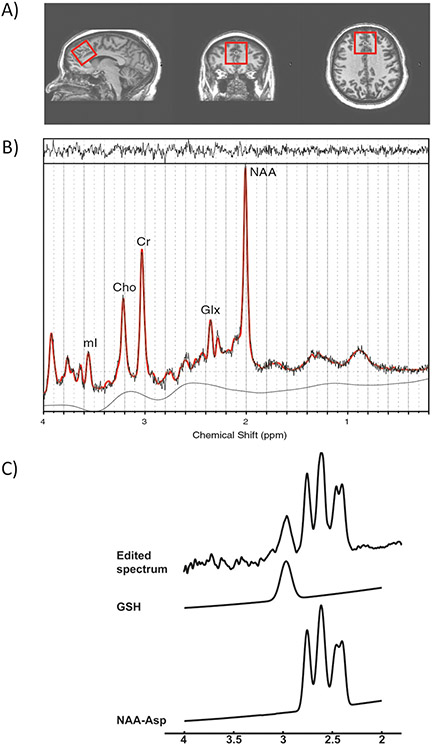

All investigations were performed on a 3T MR scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) with a whole-body transmit coil in combination with an 8-channel receive coil. A T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (1 mm isotropic voxels, TR = 8 ms, TE = 3.8 ms, flip angle = 8°, 256 × 256 acquisition matrix, FOV 256 × 180 × 150 mm3, SENSE factor 2) was obtained for anatomical reference. Spectroscopic voxels were positioned in the dACC (35 × 35 × 35 mm3) (Fig. 1a). For glutamate measurement, conventional 1H-MR spectra were acquired using a point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS; TR = 5000 ms, TE = 35 ms, 16 averages with water suppression and one average without water suppression). Water suppression was achieved using variable pulse powers and optimized relaxation delays (VAPOR) presaturation pulses.

Fig. 1. Voxel placement and sample spectra from dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex (dACC).

a From left to right: sagittal view, coronal view, and axial view of the voxel. b A typical fitted spectrum (in red). Indicated are myo-inositol (mI), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), Glx and total NAA. Above the spectrum the residual signal after fitting is displayed. The baseline is displayed below the spectrum. c A typical MEGA-PRESS spectrum demonstrating typical fit of peaks for GSH and total NAA and aspartate.

Conventional spectra were analyzed using LCModel version 6.3 for creatine (Cr) and Glx [52] (Fig. 1b). An in vitro basis set was used to analyze the metabolites in LCModel along with the default LCModel macromolecule spectra with spline baseline to fit the baseline. Although Cr has been a focus of other psychosis research [53, 54] there was no difference between Cr levels (quantified relative to unsuppressed water signal) in the controls (mean ± standard deviation = 5.14 ± 0.46) compared to the patients (4.87 ± 0.80; P = 0.226) in this study population. The results for Glx presented are Glx ratios with respect to Cr (Glx/Cr).

GSH in dACC was acquired as a secondary 3T 1H-MRS outcome and the GSH edited 1H-MR spectra were acquired using a MEGA-PRESS sequence with interleaving 30 ms Gaussian editing pulses at 4.56 ppm (“on”) and 5.50 ppm (“off”) (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 130 ms, 16 averages) (Fig. 1c) [25]. Further details of data processing and quantification of GSH in the dACC can be found in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Methods; Supplementary Table 2). The levels of GSH were normalized by the levels of Cr (GSH/Cr) measured from the “off” acquisition. The presence of CSF in the dACC voxel equally affects the metabolite (Glx, GSH, Cr) estimates within the same dACC voxel and therefore the measured fraction of CSF within the voxel was not used to generate the metabolite ratios (Glx/Cr, GSH/Cr). In the present manuscript, we describe GSH/Cr and Glx/Cr simply as GSH and Glx, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons of demographic and clinical data were calculated using independent t-test for continuous variables, and Chi-squared test for categorical data. Group differences in targeted markers (peripheral GSH, dACC Glx, dACC GSH) were tested using ANCOVA with adjustment for age, gender, race, and smoking status. Correlation analysis was performed to study the relationships between peripheral GSH and 1H-MRS metabolites, as well as those between metabolites and neuropsychological test scores.

Specifically, two-sided partial Pearson’s correlation analysis with adjustment of age, gender, race, smoking status, and diagnosis (controls or patients) was performed to study correlations in the total population. We also studied correlations within individual groups (patients, controls). For the patient group, two-sided partial Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed with adjustment for age, gender, race, smoking status, duration of illness, and medication (chlorpromazine equivalent doses). For the control group, two-sided partial Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed with adjustment of age, gender, race, and smoking status. Permutation testing was performed to assess the significance of results from correlation analyses performed with adjustment for confounding variables.

Results

Study population and neuropsychological assessment

Fifty healthy controls and 46 patients with SZ were enrolled in this study and completed provision of peripheral blood samples and/or imaging. One patient refused the SAPS and SANS assessment though all patients completed SCID interview for diagnostic assessment. Some participants (both patients and controls) failed to participate in all aspects of the study since (i) Lymphoblast collection predated collection of plasma and 1H-MRS; (ii) Some individuals participated only in conventional 1H-MRS imaging without edited 1H-MR spectra for GSH; and (iii) In a limited number of cases the transformation of lymphocytes to lymphoblasts was unsuccessful (see Supplementary Table 3 for itemized multimodal data available from each cohort).

Patients with SZ and healthy controls were well matched in age, gender, ethnicity, years of education, and premorbid intelligence (Table 1), although more patients reported current smoking habit (χ2 = 9.558, P = 0.002). Other found characteristics of the study population (medication usage, neuropsychological performance) are in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Results). The patient and control groups did not differ in composition of gray matter, white matter, or CSF within the voxel (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics for patients with schizophrenia (SZ) and healthy control participants (CON).

| Characteristics | SZ (N = 46) | CON (N = 50) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years, Average ± SD) | 34.17 ± 11.80 | 32.06 ± 11.28 | 0.372b |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 34/12 | 34/16 | 0.524c |

| Race (African American/Caucasian/Asian/Mixed) | 27/17/2/0 | 37/12/0/1 | 0.101d |

| Years of Education (Years, Average ± SD) | 12.42 ± 2.57 | 13.28 ± 1.98 | 0.070b |

| Smoking (Yes/No) | 23/23 | 10/40 | 0.002c |

| Neurocognitive Functione (Average ± SD) | |||

| Composite (SZ/CON: 42/48) | 84.49 ± 10.50 | 94.77 ± 9.81 | <0.001b |

| Processing Speed (SZ/CON: 42/49) | 80.31 ± 16.22 | 95.92 ± 15.24 | <0.001b |

| Verbal Memory (SZ/CON: 46/49) | 81.48 ± 16.39 | 93.65 ± 17.02 | 0.001b |

| Visuospatial Memory (SZ/CON: 46/49) | 82.26 ± 19.31 | 89.92 ± 17.49 | 0.046b |

| Ideational Fluency (SZ/CON: 45/50) | 88.33 ± 14.68 | 97.82 ± 14.78 | 0.002b |

| Executive Function | 91.85 ± 17.99 | 95.02 ± 16.69 | 0.374b |

| Premorbid IQ | 98.61 ± 10.61 | 101.88 ± 12.75 | 0.177 |

| SAPS (Mean ± SD) (SZ: 45) | 14.91 ± 17.43 | NA | |

| SANS (Mean ± SD) (SZ: 45) | 30.73 ± 20.11 | NA | |

| CPZ equivalents (Mean ± SD) | 381.33 ± 330.25 | NA | |

| Duration of illness (Years, Mean ± SD) | 12.36 ± 11.45 | NA |

The threshold for significance is P < 0.05 except for testing in five neurocognitive domains in which significance is set at P < 0.01.

t-test.

χ2 test.

Fisher’s exact test was employed due to small numbers within some ethnic groups.

Domain scores are presented for those patients (SZ) and healthy control participants (CON) who completed neurocognitive testing. If data is not available for all members of the total study population (46 patients with SZ, 50 CON) then the numbers of subjects with available data are listed in parentheses.

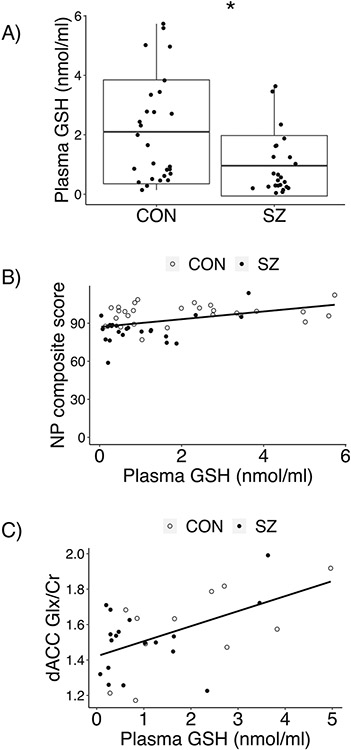

GSH in peripheral tissues

We found lower levels of GSH in plasma of patients with SZ (0.96 ± 1.02 nmol/ml) compared with that of healthy controls (2.10 ± 1.75 nmol/ml; adjusted P = 0.02; Fig. 2a). Lower GSH in lymphoblasts was also observed in patients (9.68 ± 4.26 nmol/mg) compared to controls (13.69 ± 5.57 nmol/mg; adjusted P = 0.001; Supplementary Fig. 1). A correlation between plasma GSH and lymphoblast GSH was not observed in the total population or in either group (patients, controls).

Fig. 2. Comparison of plasma GSH between groups as well as evaluation of its relationship with other measured variables across and within groups.

a GSH levels in plasma were lower in 24 patients with SZ (0.96 ± 1.02 nmol/ml) compared with those of 27 CON (2.10 ± 1.75 nmol/ml; adjusted for confounding variables P = 0.02; unadjusted P = 0.006). Unadjusted data shown. b Adjusting for confounding variables, plasma GSH was found to be positively correlated with neuropsychological (NP) composite score within data from the total population (r = 0.30, P = 0.03) and within patients alone (r = 0.57, P = 0.003), but not within the control group. Permutation testing further confirmed the significance of this finding (total population: P = 0.04; patients only: P = 0.01). Results were unchanged without adjustment (r = 0.44, P = 0.002; patients only: r = 0.48, P = 0.02). Plasma GSH was not correlated with NP composite score within the control group (with or without adjusting for confounding variables). Unadjusted data shown. c Adjusting for confounding variables, GSH in plasma and Glx in dACC were positively correlated in the total population, patient only group, and control only group. Permutation testing confirmed the significance of these results. Without adjustment, the results were unchanged for the total population or control only group, but were not significant for the patient only group. Unadjusted data shown.

Plasma GSH levels and neurocognitive function

Adjusting for confounding variables, plasma GSH was found to be positively correlated with neuropsychological composite score (Fig. 2b; Table 2a) using data from the total population (r = 0.30, P = 0.03), as well within patients alone (r = 0.57, P = 0.003). Permutation testing further confirmed the significance of this finding (total population: P = 0.04; patients only: P = 0.01). Plasma GSH was not correlated with neuropsychological composite score within the control group.

Table 2.

Summarized relationships between measured variables across the total population and within groups after adjusting for confounding variables. (A) Correlation between plasma GSH and neuropsychological (NP) composite score, dACC Glx, and dACC GSH. (B) Correlation between dACC Glx and neuropsychological (NP) composite score and dACC Glx. (C) Correlation between dACC GSH and neuropsychological (NP) composite score.

| A. Association with plasma GSH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP composite score | 1H-MRS Glx (dACC) |

1H-MRS GSH (dACC) |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| Total | 0.30 | 0.0328 | 0.60 | 0.0005 | 0.13 | 0.6373 |

| Patient | 0.57 | 0.0030 | 0.67 | 0.0047 | 0.36 | 0.4360 |

| Control | 0.21 | 0.2819 | 0.78 | 0.0048 | 0.69 | 0.1005 |

| B. dACC Glx correlation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP composite score |

1H-MRS GSH (dACC) |

|||

| r | P | r | P | |

| Total | 0.28 | 0.1165 | 0.45 | 0.0281 |

| Patient | 0.52 | 0.0137 | 0.26 | 0.4515 |

| Control | −0.09 | 0.7768 | 0.86 | 0.0009 |

| C. 1H-MRS GSH (dACC) | ||

|---|---|---|

| NP composite score | ||

| r | P | |

| Total | 0.04 | 0.841 |

| Patient | 0.54 | 0.0319 |

| Control | −0.52 | 0.1073 |

Ps < 0.05 are emphasized in bold.

The relationships between subdomains of neuropsychological performance and plasma GSH were also tested (Supplementary Table 4). Within patients after adjusting for confounding variables, performance in executive functioning positively correlated with plasma GSH (r = 0.45, P = 0.03; permutation: P = 0.04), and visuospatial memory positively correlated with plasma GSH (r = 0.43, P = 0.04, permutation P = 0.04). There were no correlations observed between plasma GSH and neuropsychological performance in any subdomain within the total population or within the control only group.

Plasma GSH levels correlated with levels of Glx in the dACC

We studied possible correlation between plasma GSH levels and Glx levels in the dACC. We observed significant correlations in the total population, patient only group, and control only group (Table 2a; Fig. 2c). Permutation testing confirmed the significance of these results (Supplementary Table 5). Plasma GSH was not correlated with dACC GSH in any group (Table 2a).

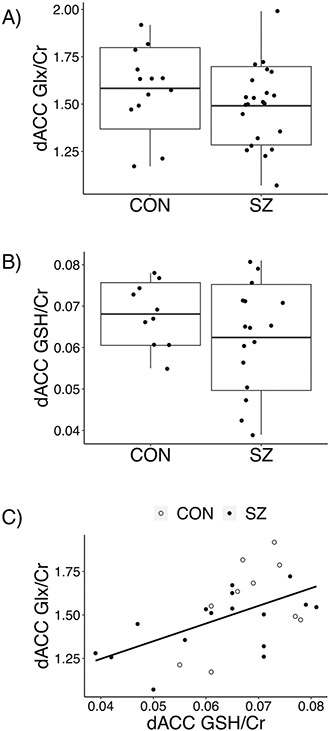

Correlation between dACC Glx and GSH and the relationship of each neurochemical to neurocognitive function

We studied possible correlation between the levels of Glx and GSH in the dACC. Although we did not observe a significant difference in the levels of these neurochemicals between patient and control groups (Fig. 3a, b), significant correlations between dACC Glx and dACC GSH levels were observed in the total population and the control only group, but not within patients (Table 2b; Fig. 3c). Permutation testing confirmed these results (Supplementary Table 5).

Fig. 3. Comparison of dACC Glx and dACC GSH between groups as well as evaluation of their relationship across and within groups.

a Glx in dACC did not differ between patients with SZ (1.49 ± 0.21 nmol/ml) and CON (1.58 ± 0.21) nmol/ml; adjusted for confounding variables P = 0.38; unadjusted P = 0.23). Unadjusted data shown with mean (middle line) and standard deviation (box). b GSH in dACC did not differ between patients with SZ (0.062 ± 0.01 nmol/ml) and CON (0.068 ± 0.01 nmol/ml; adjusted for confounding variables P = 0.20; unadjusted P = 0.17). Unadjusted data shown with mean (middle line) and standard deviation (box). c) Adjusting for confounding variables, positive correlations between dACC Glx and dACC GSH levels were observed in the total population and the control only group. Permutation testing further confirmed the significance of these findings. No relationship was found within patients. These results were unchanged without adjustment for confounding variables. Unadjusted data shown.

We next examined possible correlation between the levels dACC Glx and the neuropsychological composite score. We observed the significant correlation in the patient only group, but not in the total population or control only group (Table 2b). We further studied the subdomains of the neuropsychological test and found that visuospatial memory was significantly correlated with dACC Glx in the total population and the patient only group after adjustment for confounding variables (Supplementary Table 4). Permutation analysis confirmed these results.

Similarly, we tested for correlation between the levels of dACC GSH and neuropsychological test scores. In the patient only group, we observed significant correlation between dACC GSH and composite score (Table 2c), and between dACC GSH and ideational fluency (Supplementary Table 4). Permutation testing supported these correlations. No significant correlations were observed between the levels of dACC GSH and any neuropsychological scores in the total and control only groups.

The relationships between molecular and clinical characteristics

SANS/SAPS scores were not correlated with dACC Glx, dACC GSH, plasma GSH, or lymphoblast GSH.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study include lower GSH levels in extracellular (plasma) and intracellular (lymphoblasts) peripheral blood of patients with SZ compared to controls. Importantly, we now report that plasma GSH levels positively correlated with composite neurocognitive scores in the total study population and the patient only population, and with factor scores in executive function and visuospatial memory within patients. Furthermore, even though there was no significant difference in dACC Glx between patients and controls, plasma GSH levels positively correlated with dACC Glx levels in the total, the patient only, the control only populations. Both dACC Glx and dACC GSH levels showed correlations with composite neurocognitive scores in the patient only group. Lastly, the levels of dACC GSH correlated with factor scores in ideational fluency in the patient only population, whereas the levels dACC Glx correlated with factor scores in visuospatial memory in both total and patient only populations. As described above, confounding factors were considered in all analyses with the positive results confirmed by permutation test.

Our finding of significant relationship between plasma GSH levels and neurocognitive function supports the need for further study of oxidative stress in the neurobiology of cognitive deficits related to SZ, and perhaps more broadly across syndromes with cognitive impairment. Cognitive deficits are not primary diagnostic features of SZ, though it is widely accepted that cognitive impairment is frequently found in the patients, and a critical predictor of clinical and functional prognosis [55-57]. In our study, patients with SZ showed significant deficits in domains of processing speed, verbal learning and memory, and ideational fluency compared to the controls. Recent meta-analysis has confirmed deficits in the domain of processing speed in patients with SZ [58], and these deficits in processing speed may account for impaired cognitive performance in other domains [49]. Thus, peripheral GSH may have potential to serve as a predictive marker of brain function and clinical outcome, even if the relationship is mechanistically indirect. This promising relationship between peripheral GSH and cognition also has clinical relevance since the indirect antioxidant sulforaphane (SFN), is now commercially available in concentrated dietary supplements [59], and there are multiple reports of its beneficial, therapeutic effect on cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders [60, 61]. We recently reported that sub-chronic administration of the broccoli-derived phytochemical, SFN, raises blood GSH levels in humans [34]. The related, provocative hypothesis that circulating GSH may have a protective effect on brain glutamate and cognition in health and SZ may be tested with a back-translational approach.

Although further studies with larger samples are expected, these results suggest a novel link between central glutamatergic deficits that are often found in SZ patients and peripheral redox imbalance (or disturbance of GSH signaling). It is of note that 3T 1H-MRS has limited ability to separate signals of glutamate and glutamine, instead providing the measured level of both neurochemicals as Glx. Higher magnet strength will allow better differentiation of glutamate and glutamine peaks on conventional spectral analysis, allowing improved ability to study this link further. Indeed, a recent study that used a 7T scanner reported correlation between the levels of glutamate and GSH in the dACC [28], which is in line with our observation at 3T that dACC GSH and Glx is correlated at least in the total population and control only group. Furthermore, the work by Kumar et al. [28] also suggests that the relationship between peripheral GSH and dACC Glx in the present study may reflect the relationship between peripheral GSH and glutamate (without glutamine) in the brain. We also observed correlation between the levels of dACC Glx and neurocognitive composite score. In summary, these three correlations observed within patients in the present study [(1) correlation between peripheral GSH and neurocognitive composite score; (2) correlation between peripheral GSH and dACC Glx; and (3) correlation between dACC Glx and neurocognitive composite score] are consistent with the hypothesized link between central glutamatergic deficits, peripheral redox imbalance, and cognitive impairment in SZ.

We acknowledge the power due to modest sample size as a potential limitation of this study, which might result in the failure of detecting significant differences in the levels of Glx (glutamate) and GSH between patients and controls. However, interesting observations using regional 1H-MRS data have been reported in spite of the absence of two-group (patients, controls) difference in metabolite levels [48, 62, 63], and we now report novel correlations involving GSH and glutamate signaling between peripheral and brain tissues. We also note as a limitation that Cr was used as an internal reference as opposed to referencing each metabolite to the unsuppressed water signal. Through the present clinical study, we generate the novel question of why peripheral GSH may be mechanistically linked to dACC glutamate levels and cognition in SZ that may be investigated initially using animal and cell models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH-094268 Silvio O. Conte center, MH-092443, MH-105660, MH-107730) (AS), as well as grants from Stanley (AS), S-R (AS), RUSK (AS), NARSAD (JC and AS), and support of the Alexander Wilson Schweizer Fellowship (JC). This project also applies tools developed under P41 EB015909 (RE and PB) and R01 EB016089 (RE). The design, writing, and the decision of publication are only of the authors, who have no conflict of interest to declare. A fund from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation was partly used for recruitment of 11 healthy controls. The authors thank Drs. Kim Do and Michel Cuenod for kindly contributing to scientific discussions and feedback related to this work. They thank Dr. Laurent Younes and Dr. Brian Caffo for discussions regarding medical statistics and data analysis, and also sincerely thank Yukiko Lema for assistance in graphical design of the figures.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00901-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Landek-Salgado MA, Faust TE, Sawa A. Molecular substrates of schizophrenia: homeostatic signaling to connectivity. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:10–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emiliani FE, Sedlak TW, Sawa A. Oxidative stress and schizophrenia: recent breakthroughs from an old story. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27:185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulak A, Steullet P, Cabungcal JH, Werge T, Ingason A, Cuenod M, et al. Redox dysregulation in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: insights from animal models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1428–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388:86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koga M, Serritella AV, Sawa A, Sedlak TW. Implications for reactive oxygen species in schizophrenia pathogenesis. Schizophr Res. 2016;176:52–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Catts VS, Shannon Weickert C. Lower antioxidant capacity in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52:690–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraguas D, Díaz-Caneja CM, Ayora M, Hernández-Álvarez F, Rodríguez-Quiroga A, Recio S, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen TT, Eyler LT, Jeste DV. Systemic biomarkers of accelerated aging in schizophrenia: a critical review and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietrich-Muszalska A, Olas B, Głowacki R, Bald E. Oxidative/nitrative modifications of plasma proteins and thiols from patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raffa M, Mechri A, Othman LB, Fendri C, Gaha L, Kerkeni A. Decreased glutathione levels and antioxidant enzyme activities in untreated and treated schizophrenic patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raffa M, Barhoumi S, Atig F, Fendri C, Kerkeni A, Mechri A. Reduced antioxidant defense systems in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39:371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruiz-Litago F, Seco J, Echevarría E, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, Gil J, Irazusta J, et al. Adaptive response in the antioxidant defence system in the course and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia patients: a 12-months follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200:218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nucifora LG, Tanaka T, Hayes LN, Kim M, Lee BJ, Matsuda T, et al. Reduction of plasma glutathione in psychosis associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in translational psychiatry. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidović B, Milovanović S, Dorđević B, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Stefanović A, Ivanišević J, et al. Effect of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on oxidative stress markers and antioxidative defense in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26:205–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidović B, Stefanović A, Milovanović S, Ðorđević B, Kotur-Stevuljević J, Ivanišević J, et al. Associations of oxidative stress status parameters with traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in patients with schizophrenia. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2014;74:184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukushima T, Iizuka H, Yokota A, Suzuki T, Ohno C, Kono Y, et al. Quantitative analyses of schizophrenia-associated metabolites in serum: serum D-lactate levels are negatively correlated with gamma-glutamylcysteine in medicated schizophrenia patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai MC, Liou CW, Lin TK, Lin IM, Huang TL. Changes in oxidative stress markers in patients with schizophrenia: the effect of antipsychotic drugs. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffa M, Atig F, Mhalla A, Kerkeni A, Mechri A. Decreased glutathione levels and impaired antioxidant enzyme activities in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenic patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altuntas I, Aksoy H, Coskun I, Cayköylü A, Akçay F. Erythrocyte superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activities, and malondialdehyde and reduced glutathione levels in schizophrenic patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2000;38:1277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Do KQ, Trabesinger AH, Kirsten-Krüger M, Lauer CJ, Dydak U, Hell D, et al. Schizophrenia: glutathione deficit in cerebrospinal fluid and prefrontal cortex in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuzawa D, Hashimoto K. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the antioxidant defense system in schizophrenia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2057–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuzawa D, Obata T, Shirayama Y, Nonaka H, Kanazawa Y, Yoshitome E, et al. Negative correlation between brain gluathione level and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a 3T 1H-MRS study. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monin A, Baumann PS, Griffa A, Xin L, Mekle R, Fournier M, et al. Glutathione deficit impairs myelin maturation: relevance for white matter integrity in schizophrenia patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:827–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terpstra M, Vaughan TJ, Ugurbil K, Lim KO, Schulz SC, Gruetter R. Validation of glutathione quantitation from STEAM spectra against edited 1H NMR spectroscopy at 4T: application to schizophrenia. MAGMA. 2005;18:276–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood SJ, Berger GE, Wellard RM, Proffitt TM, McConchie M, Berk M, et al. Medial temporal lobe glutathione concentration in first episode psychosis: a 1H-MRS investigation. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:354–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dwyer GE, Hugdahl K, Specht K, Grüner R. Current Practice and New Developments in the Use of In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy for the Assessment of Key Metabolites Implicated in the Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia. Curr Top Med Chem. 2018;18:1908–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar J, Liddle EB, Fernandes CC, Palaniyappan L, Hall EL, Robson SE, et al. Glutathione and glutamate in schizophrenia: a 7T MRS study. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:873–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesh TA, Maddock RJ, Howell A, Wang H, Tanase C, Daniel Ragland J, et al. Extracellular free water and glutathione in first-episode psychosis-a multimodal investigation of an inflammatory model for psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. 10.1038/s41380-019-0428-y. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girgis RR, Baker S, Mao X, Gil R, Javitt DC, Kantrowitz JT, et al. Effects of acute N-acetylcysteine challenge on cortical glutathione and glutamate in schizophrenia: A pilot in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Psychiatry Res. 2019;275:78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hafizi S, Da Silva T, Meyer JH, Kiang M, Houle S, Remington G, et al. Interaction between TSPO-a neuroimmune marker-and redox status in clinical high risk for psychosis: a PET-MRS study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1700–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das TK, Javadzadeh A, Dey A, Sabesan P, Théberge J, Radua J, et al. Antioxidant defense in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis of MRS studies of anterior cingulate glutathione. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;91:94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xin L, Mekle R, Fournier M, Baumann PS, Ferrari C, Alameda L, et al. Genetic polymorphism associated prefrontal glutathione and its coupling with brain glutamate and peripheral redox status in early psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1185–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sedlak TW, Nucifora LG, Koga M, Shaffer LS, Higgs C, Tanaka T, et al. Sulforaphane augments glutathione and influences brain metabolites in human subjects: a clinical pilot study. Mol Neuropsychiatry. 2018;3:214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabungcal JH, Counotte DS, Lewis E, Tejeda HA, Piantadosi P, Pollock C, et al. Juvenile antioxidant treatment prevents adult deficits in a developmental model of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2014;83:1073–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson AW, Jaaro-Peled H, Shahani N, Sedlak TW, Zoubovsky S, Burruss D, et al. Cognitive and motivational deficits together with prefrontal oxidative stress in a mouse model for neuropsychiatric illness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12462–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumann PS, Griffa A, Fournier M, Golay P, Ferrari C, Alameda L, et al. Impaired fornix-hippocampus integrity is linked to peripheral glutathione peroxidase in early psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geiser E, Retsa C, Knebel JF, Ferrari C, Jenni R, Fournier M, et al. The coupling of low-level auditory dysfunction and oxidative stress in psychosis patients. Schizophr Res. 2017;190:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavoie S, Berger M, Schlögelhofer M, Schäfer MR, Rice S, Kim SW, et al. Erythrocyte glutathione levels as long-term predictor of transition to psychosis. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shirai Y, Fujita Y, Hashimoto R, Ohi K, Yamamori H, Yasuda Y, et al. Dietary intake of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extracts during juvenile and adolescence can prevent phencyclidine-induced cognitive deficits at adulthood. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koga M, Serritella AV, Messmer MM, Hayashi-Takagi A, Hester LD, Snyder SH, et al. Glutathione is a physiologic reservoir of neuronal glutamate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409:596–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steullet P, Cabungcal JH, Monin A, Dwir D, O’Donnell P, Cuenod M, et al. Redox dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and NMDA receptor hypofunction: A “central hub” in schizophrenia pathophysiology? Schizophr Res. 2016;176:41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sedlak TW, Paul BD, Parker GM, Hester LD, Snowman AM, Taniguchi Y, et al. The glutathione cycle shapes synaptic glutamate activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:2701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gasquoine PG. Localization of function in anterior cingulate cortex: from psychosurgery to functional neuroimaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marsman A, van den Heuvel MP, Klomp DW, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Glutamate in schizophrenia: a focused review and meta-analysis of 1H-MRS studies. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:120–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poels EM, Kegeles LS, Kantrowitz JT, Slifstein M, Javitt DC, Lieberman JA, et al. Imaging glutamate in schizophrenia: review of findings and implications for drug discovery. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijtenburg SA, Wright SN, Korenic SA, Gaston FE, Ndubuizu N, Chiappelli J, et al. Altered glutamate and regional cerebral blood flow levels in schizophrenia: A (1)H-MRS and pCASL study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Egerton A, Broberg BV, Van Haren N, Merritt K, Barker GJ, Lythgoe DJ, et al. Response to initial antipsychotic treatment in first episode psychosis is related to anterior cingulate glutamate levels: a multicentre (1)H-MRS study (OPTiMiSE). Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:2145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ojeda N, Peña J, Schretlen DJ, Sánchez P, Aretouli E, Elizagárate E, et al. Hierarchical structure of the cognitive processes in schizophrenia: the fundamental role of processing speed. Schizophr Res. 2012;135:72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schretlen DJ, Vannorsdall T. Calibrated ideational fluency assessment professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tietze F. Enzymic method for quantitative determination of nanogram amounts of total and oxidized glutathione: applications to mammalian blood and other tissues. Anal Biochem. 1969;27:502–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30:672–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ongür D, Prescot AP, Jensen JE, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Creatine abnormalities in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172:44–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tibbo PG, Bernier D, Hanstock CC, Seres P, Lakusta B, Purdon SE. 3-T proton magnetic spectroscopy in unmedicated first episode psychosis: a focus on creatine. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W, Gur R, Heckers S, Malaspina D, et al. Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Weaver C, Anderson H, et al. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sánchez P, Ojeda N, Peña J, Elizagárate E, Yoller AB, Gutiérrez M, et al. Predictors of longitudinal changes in schizophrenia: the role of processing speed. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:888–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res. 2013;150:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Houghton CA. Sulforaphane: its “coming of age” as a clinically relevant nutraceutical in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:2716870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiina A, Kanahara N, Sasaki T, Oda Y, Hashimoto T, Hasegawa T, et al. An open study of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extract in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13:62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh K, Connors SL, Macklin EA, Smith KD, Fahey JW, Talalay P, et al. Sulforaphane treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:15550–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reid MA, White DM, Kraguljac NV, Lahti AC. A combined diffusion tensor imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;170:341–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaminski J, Gleich T, Fukuda Y, Katthagen T, Gallinat J, Heinz A, et al. Association of cortical glutamate and working memory activation in patients with schizophrenia: a multimodal proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.