Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly around the world since December 8, 2019. However, the key factors affecting the duration of recovery from COVID-19 remain unclear.

Objective

To investigate the associations of long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients with ambient air pollution, temperature, and diurnal temperature range (DTR) exposure.

Methods

A total of 427 confirmed cases in Changsha during the first wave of the epidemic in January 2020 were selected. We used inverse distance weighting (IDW) method to estimate personal exposure to seven ambient air pollutants (PM2.5, PM2.5-10, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3) at each subject's home address. Meteorological conditions included temperature and DTR. Multiple logistic regression model was used to investigate the relationship of air pollution exposure during short-term (past week and past month) and long-term (past three months) with recovery duration among COVID-19 patients.

Results

We found that long recovery duration among COVID-19 patients was positively associated with short-term exposure to CO during past week with OR (95% CI) = 1.42 (1.01–2.00) and PM2.5, NO2, and CO during past month with ORs (95% CI) = 2.00 (1.30–3.07) and 1.95 (1.30–2.93), and was negatively related with short-term exposure to O3 during past week and past month with ORs (95% CI) = 0.68 (0.46–0.99) and 0.41 (0.27–0.62), respectively. No association was observed for long-term exposure to air pollution during past three months. Furthermore, increased temperature during past three months elevated risk of long recovery duration in VOCID-19 patients, while DTR exposure during past week and past month decreased the risk. Male and younger patients were more susceptible to the effect of air pollution on long recovery duration, while female and older patients were more affected by exposure to temperature and DTR.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that both TRAP exposure and temperature indicators play important roles in prolonged recovery among COVID-19 patients, especially for the sensitive populations, which provide potential strategies for effective reduction and early prevention of long recovery duration of COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Recovery duration, Ambient air pollution, Temperature, Diurnal temperature range, Inverse distance weighted

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is sweeping the world and is becoming a regular developing pandemic (Li et al., 2021). Despite aggressive national responses in many countries, a large number of patients still face a difficult prognosis (Sachs et al., 2022). Some studies in developed countries reported a rate of COVID-19 mortality during hospitalization with 17% in the United States (Kim et al., 2021) and 22.3% in Germany (Karagiannidis et al., 2020). Moreover, as the recovery period becomes longer, the COVID-19 patients are at an increasing risk of decreased immunity and organ failure, which can severely affect the patients’ living quality and well-being in the later life. It can also lead to more serious complications and consequences, such as late-onset hematological complications (Korompoki et al., 2022), cardiac complications (Srinivasan et al., 2022), and smell and taste dysfunction (Vaira et al., 2022). Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore the main factors affecting the length of recovery period of COVID-19 patients in order to cope with possible pandemic normalization.

Air pollution, as one of the most important environmental factors, has been suggested to be linked with respiratory outcomes such as pneumonia (Lu et al., 2022a), but its role in the recovery duration of COVID-19 patients remains unclear. Several studies have demonstrated that more than 4600 deaths could be avoided in China alone if air pollution were controlled within certain limits (Chen et al., 2020). Particulate matters, represented by PM10 and PM2.5, can cause chronic death due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Doiron et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2011). This partially overlaps with the causes of death from COVID-19 in that COPD has been proved to be the important risk factor leading to COVID-19 patients’ death (Fiorito et al., 2022). In addition, NO2 poses serious health risks to humans, mainly respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (Bevelander et al., 2007; Gan et al., 2012). COVID-19 imposes a heavy economic and disease burden on chronically ill patients (Flor et al., 2022). Monitoring of pollutant concentrations during the primary lockdown in 44 cities in northern China found that PM2.5 and NO2 concentrations decreased by 31.8% and 45.1%, respectively (Li et al., 2020). This is associated with people traveling less and self-isolating at home. However, the pollutant concentrations are now gradually increasing again under full openness, so this study has some warning implications for the next step of outbreak prevention and control. Thereby, it is of significance to identify key air pollutant(s) associated with the duration of recovery among COVID-19 patients.

Temperature, as the most important meteorological parameter, is another alternatively key factor showing effect on the COVID-19 patients. Several studies have shown that H1N1 pandemic (H1N1pdm) virus, poliovirus, echovirus, and coxsackievirus are more easily killed at high temperatures and remain longer at low temperatures (Dublineau et al., 2011; Pinon and Vialette, 2018). Some studies have found that diurnal perpetuate range (DTR) has a detrimental effect on measles epidemics (Park et al., 2020) and cardiovascular disease (Kim et al., 2016). Previous studies have found an impact of warmer temperatures on the reduction of new cases of COVID-19 (Demongeot et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a, Wu et al., 2020b). In addition, several studies have shown a negative correlation between COVID-19 incidence and temperature (Bashir et al., 2020a), with temperatures not exceeding 8 °C for most of the winter during the full-scale blockade in China. In a Korean study, temperature was found to be a risk factor for morbidity when the temperature was below 3 °C with a threshold of 8 °C (Hoang and Tran, 2021). Therefore, the conclusion of the temperature effect on COVID-19 remains controversial, which warrants further investigations. However, only few studies have shown a relationship between the recovery period and DTR in COVID-19 patients.

We hypothesized that exposure to outdoor environmental factors including air pollution, temperature, and DTR is associated with the length of recovery in COVID-19 patients, and the short-term and long-term exposure may have different effects. To verify this hypothesis, we conducted a clinical survey of COVID-19 patients with a retrospective cohort design at XiangYa Hospital in Changsha, China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

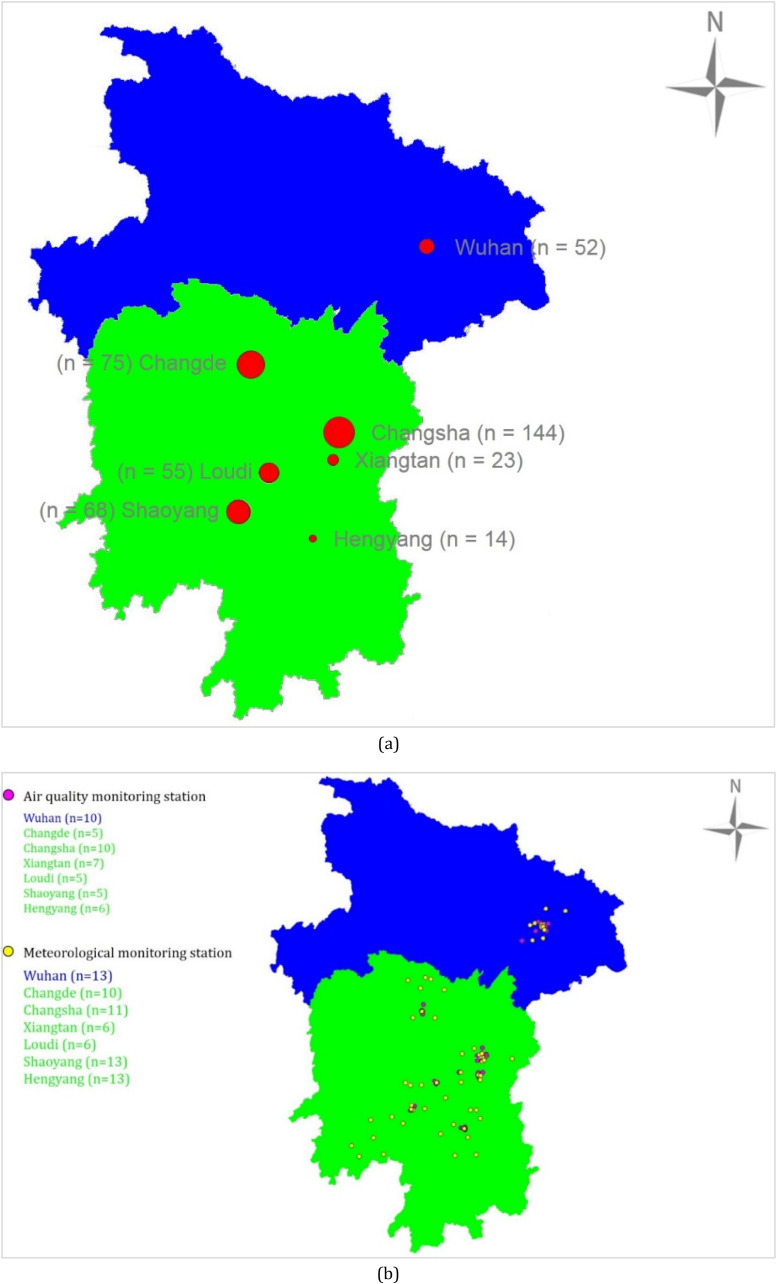

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 427 patients with COVID-19 who attended XiangYa Hospital in Changsha from September 2020 to January 2012. The home addresses of these COVID-19 patients were located at seven different cities in China (Fig. 1 -a): Wuhan (n = 52), Changde (n = 75), Changsha (n = 144), Xiangtan (n = 23), Loudi (n = 55), Shaoyang (n = 68), and Hengyang (n = 14). All these patients were hospitalized at XiangYa Hospital in Changsha from January 3 to February 28, 2020. These seven cities are medium-sized provincial capital cities in Hunan Province, south-central China. They have a subtropical monsoon climate with abundant rainfall in all seasons. The clinical data were collected from the electrical electronic case of COCID-19 patients who were received and cured by XiangYa Hospital during the studying period.

Fig. 1.

Number of surveyed COVID-19 patients from seven studying cities (n = 427) (a), and distribution of ambient air quality monitoring stations (n = 48) and meteorological stations (n = 72) at seven studying cities in China (b).

2.2. Health outcome

As the typical recovery period for young people is 1–2 weeks (Naseef et al., 2022), we defined the health outcome (long recovery duration of COVID-19) as the recovery duration of COVID-19 patients equal or longer than 3 weeks (21 days).

2.3. Personal exposure assessment

During 2019–2020, data on 24-hourly concentrations of PM2.5, PM2.5-10, PM10, SO2, NO2, and CO and meteorological parameters including daily mean, maximum and minimum temperatures were respectively obtained from different ambient air quality monitoring stations (Wuhan: n = 10, Changde: n = 5, Changsha: n = 10, Xiangtan: n = 7, Loudi: n = 5, Shaoyang: n = 5, and Hengyang: n = 6) and meteorological monitoring stations (Wuhan: n = 13, Changde: n = 10, Changsha: n = 11, Xiangtan: n = 6, Loudi: n = 6, Shaoyang: n = 13, and Hengyang: n = 13) in each city (Fig. 1-b). Individual exposures were assessed based on latitude and longitude by the inverse distance weighting method (Deng et al., 2015, Lu et al., 2022b). Due to the lag of pollutant and temperature effects, we defined exposure during past week and past month since the date of onset as short-term exposures and exposure during past three months before onset date as long-term exposure.

2.4. Covariates

The covariates were gender (male vs female), age (<50 years vs ≥ 50 years), isolation body temperature (<37.3 °C vs ≥ 37.3 °C), double lung shadow (yes vs no), and symptom score. We summarized the respiratory symptom scores to derive the presence of respiratory, gastrointestinal, muscle/joint, head, and remaining symptom scores, with respiratory symptoms including cough, sore throat, coughing, and dyspnea, and gastrointestinal symptoms including anorexia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and nausea. Head symptoms included headache, dizziness. Muscle/joint symptoms included discomfort, fatigue, myalgia, and/or arthralgia. Other symptoms mainly referred to chilliness.

2.5. Statistical analysis

In this study, a multiple logistic regression model was used to investigate the length of the recovery period in COVID-19 patients in relation to ambient air pollution, temperature, and DTR. Associations by the regression analysis were estimated as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% confidence intervals), and a two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance. All statistical analyses in this study were done by SPSS software (version 22.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA).

3. Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics among our surveyed COVID-19 patients and the prevalence of long recovery duration stratified by covariates. Of the 427 COVID-19 patients, 220 (51.5%) reported a long recovery duration (≥21 days). The patient's age, double lung shadow, and symptoms score were significantly associated with long recovery duration (p < 0.05). The prevalence of long recovery duration was significantly higher among patients with older age (≥50 years), double lung shadow, and higher symptoms score (>1) than those with younger age, (<50 years), without double lung shadow, and with lower symptoms score (≤1). However, sex and isolation body temperature were not associated with long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Covariates and demographic information among COVID-19 patients and those with long recovery duration (n = 427).

| Total |

Long recovery duration (≥21 days) |

P-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (n) | (%) | Case (n) | (%) | ||

| Total | 427 | (100) | 220 | (51.5) | |

| Sex | 0.660 | ||||

| Male | 213 | (50) | 112 | (52.6) | |

| Female | 214 | (50) | 108 | (50.5) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| <50 | 249 | (58) | 111 | (44.6) | |

| ≥50 | 178 | (42) | 109 | (61.2) | |

| Isolation body temperature (°C) | 0.704 | ||||

| <37.3 | 306 | (72) | 155 | (50.7) | |

| ≥37.3 | 121 | (28) | 65 | (53.7) | |

| Double lung shadow | 0.007 | ||||

| No | 132 | (31) | 56 | (42.4) | |

| Yes | 275 | (64) | 159 | (57.8) | |

| Symptoms score | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 58 | (14) | 15 | (25.9) | |

| 1 | 69 | (16) | 33 | (47.8) | |

| 2 | 88 | (21) | 52 | (59.1) | |

| 3 | 80 | (19) | 40 | (50.0) | |

| 4 | 62 | (15) | 34 | (54.8) | |

| 5 | 70 | (16) | 46 | (65.7) | |

Sum of the number is not 427 due to missing data. The values p < 0.05 in bold were indicated as statistically significance difference in the prevalence of long recovery duration stratified by each covariate.

Table 2 summaries personal exposure to ambient air pollution and temperature indicators during past week, past month, and past 3 months. COVID-19 patients with long recovery duration had significantly higher exposure levels of NO2 and CO while lower exposure level of O3 during past week and past month than those with normal recovery duration (p < 0.05). In addition, a significantly higher exposure level of PM2.5 during past week was also observed in COVID-19 patients with long recovery duration than normal recovery duration. On the other hand, COVID-19 patients with long recovery duration experienced significantly lower short-term exposure to DTV during past week and past month while higher long-term to temperature during past 3 months (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Statistics of exposure to outdoor air pollution, temperature, and diurnal temperature variation (DTV) among COVID-19 patients with long and normal recovery duration (n = 427).

| Total |

Long recovery Duration |

Normal recovery Duration |

P value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 25% | 50% | 75% | IQR | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Past week | |||||||||||

| PM2.5 | 51.54 | 12.63 | 43.06 | 52.25 | 60.37 | 17.31 | 52.01 | 12.30 | 51.14 | 12.99 | 0.535 |

| PM2.5-10 | 8.96 | 4.93 | 5.24 | 7.90 | 11.65 | 6.41 | 9.37 | 5.04 | 8.53 | 4.82 | 0.122 |

| PM10 | 53.70 | 14.71 | 42.76 | 51.91 | 62.46 | 19.70 | 53.65 | 14.54 | 53.92 | 15.04 | 0.868 |

| SO2 | 5.06 | 2.05 | 3.92 | 4.61 | 6.03 | 2.11 | 5.00 | 2.35 | 5.14 | 1.65 | 0.538 |

| NO2 | 21.55 | 9.58 | 13.52 | 18.59 | 27.06 | 13.54 | 22.52 | 9.60 | 20.43 | 9.45 | 0.046 |

| CO | 0.97 | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 1.09 | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.16 | 0.006 |

| O3 | 62.88 | 13.76 | 54.10 | 59.84 | 73.03 | 18.93 | 60.68 | 13.50 | 65.57 | 13.41 | 0.001 |

| T | 6.91 | 2.96 | 4.93 | 6.21 | 7.50 | 2.57 | 6.82 | 3.10 | 7.00 | 2.78 | 0.575 |

| DTV | 3.20 | 1.84 | 1.79 | 2.71 | 4.00 | 2.21 | 2.98 | 1.80 | 3.50 | 1.85 | 0.008 |

| Past month | |||||||||||

| PM2.5 | 55.89 | 7.58 | 49.92 | 55.61 | 61.98 | 12.06 | 57.15 | 7.70 | 54.43 | 6.83 | 0.001 |

| PM2.5-10 | 11.61 | 4.50 | 8.60 | 11.13 | 14.52 | 5.92 | 11.83 | 4.38 | 11.33 | 4.52 | 0.313 |

| PM10 | 58.39 | 10.32 | 51.54 | 57.77 | 64.23 | 12.69 | 58.82 | 10.36 | 57.91 | 10.29 | 0.424 |

| SO2 | 5.97 | 2.56 | 4.43 | 5.39 | 7.15 | 2.72 | 6.08 | 3.09 | 5.83 | 1.78 | 0.373 |

| NO2 | 29.63 | 8.46 | 22.76 | 27.57 | 35.92 | 13.16 | 30.98 | 8.40 | 28.17 | 8.06 | 0.002 |

| CO | 1.07 | 0.15 | 0.94 | 1.09 | 1.18 | 0.24 | 1.09 | 0.15 | 1.05 | 0.16 | 0.028 |

| O3 | 47.57 | 10.04 | 38.88 | 48.58 | 53.66 | 14.78 | 44.97 | 9.08 | 50.37 | 10.21 | <0.001 |

| T | 5.81 | 0.82 | 5.32 | 5.77 | 6.15 | 0.83 | 5.76 | 0.69 | 5.83 | 0.90 | 0.479 |

| DTV | 2.78 | 0.99 | 2.08 | 2.44 | 3.02 | 0.94 | 2.67 | 0.98 | 2.91 | 1.00 | 0.024 |

| Past 3 months | |||||||||||

| PM2.5 | 59.84 | 5.82 | 55.73 | 59.92 | 65.08 | 9.35 | 60.44 | 5.90 | 59.19 | 5.66 | 0.050 |

| PM2.5-10 | 23.34 | 5.50 | 19.18 | 22.35 | 27.05 | 7.87 | 23.63 | 5.08 | 23.08 | 5.94 | 0.366 |

| PM10 | 74.41 | 8.16 | 69.11 | 74.34 | 81.47 | 12.36 | 74.58 | 7.77 | 74.29 | 8.67 | 0.741 |

| SO2 | 9.75 | 3.68 | 7.34 | 8.87 | 10.78 | 3.44 | 9.80 | 4.11 | 9.69 | 3.13 | 0.785 |

| NO2 | 38.58 | 9.81 | 28.05 | 39.53 | 46.15 | 18.10 | 39.34 | 9.86 | 37.79 | 9.65 | 0.150 |

| CO | 1.02 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 1.10 | 0.15 | 1.02 | 0.11 | 1.02 | 0.11 | 0.662 |

| O3 | 62.78 | 8.17 | 56.81 | 61.21 | 71.60 | 14.79 | 63.23 | 8.08 | 62.24 | 8.23 | 0.270 |

| T | 9.98 | 1.00 | 9.24 | 9.98 | 10.64 | 1.40 | 10.18 | 0.95 | 9.72 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| DTV | 4.49 | 1.52 | 3.61 | 3.76 | 4.52 | 0.91 | 4.46 | 1.49 | 4.54 | 1.56 | 0.641 |

PM2.5 (μg/m3) = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm, PM2.5-10 (μg/m3) = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter between 2.5 μm and 10 μm, PM10 (μg/m3) = particulate matter with aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm, SO2 (μg/m3) = sulphur dioxide, NO2 (μg/m3) = nitrogen dioxide, CO (mg/m3) = carbon monoxide, O3 (μg/m3) = ozone; T (°C) = temperature, DTV (°C) = diurnal temperature variation; SD = standard deviation, IQR = inter quartile range.

Table 3 provides the associations between short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and long recovery duration among COVID-19 patients. Similar trends in the association between air pollution and long recovery duration were detected in the two different models. We found that long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients was significantly associated with short-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution including CO during past week and past month with ORs (95% CI) of 1.42 (1.01–2.00) and 1.53 (1.06–2.23) respectively and NO2 during past month [OR (95% CI) = 1.95 (1.30–2.93)] for an IQR increase in each pollutant exposure during each time window after adjusting for all the covariates and outdoor DTV exposure. Furthermore, we observed significantly negative association between long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients and short-term exposure to O3 during past week and past month, with ORs (95% CI) = 0.68 (0.46–0.99) and 0.41 (0.27–0.62) respectively. However, we did not detect any association for long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution.

Table 3.

Associations between short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients, with OR (95% CI) (n = 427).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) a | Adjusted OR (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|

| Past week | ||

| PM2.5 | 1.01 (0.72, 1.42) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.60) |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.31 (0.96, 1.80) | 1.35 (0.99, 1.85) |

| PM10 | 0.94 (0.65, 1.36) | 1.09 (0.75, 1.57) |

| SO2 | 0.75 (0.56, 1.00)c | 0.85 (0.62, 1.16) |

| NO2 | 1.31 (0.91, 1.89) | 1.26 (0.90, 1.78) |

| CO | 1.53 (1.09, 2.14)c | 1.42 (1.01, 2.00)c |

| O3 | 0.58 (0.41, 0.83)d | 0.68 (0.46, 0.99)c |

| Past month | ||

| PM2.5 | 2.11 (0.95, 4.68) | 2.00 (1.30, 3.07)d |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.11 (0.78, 1.56) | 1.19 (0.85, 1.66) |

| PM10 | 1.48 (0.74, 2.97) | 1.48 (0.83, 2.63) |

| SO2 | 0.93 (0.64, 1.36) | 1.02 (0.67, 1.53) |

| NO2 | 1.94 (0.96, 3.89) | 1.95 (1.30, 2.93)e |

| CO | 1.53 (1.06, 2.21)c | 1.53 (1.06, 2.23)c |

| O3 | 0.43 (0.28, 0.67)e | 0.41 (0.27, 0.62)e |

| Past 3 months | ||

| PM2.5 | 1.51 (0.99, 2.30) | 1.45 (0.95, 2.22) |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.13 (0.77, 1.66) | 1.22 (0.84, 1.76) |

| PM10 | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) | 1.01 (0.69, 1.48) |

| SO2 | 0.88 (0.70, 1.11) | 0.87 (0.69, 1.11) |

| NO2 | 1.27 (0.81, 1.98) | 1.37 (0.87, 2.17) |

| CO | 1.18 (0.85, 1.62) | 1.20 (0.87, 1.67) |

| O3 | 1.56 (0.71, 3.41) | 1.41 (0.65, 3.08) |

Table 4 presents the relationships of short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor temperature and DTV with long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients. The ORs were similar in the two different models. We found that long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients was significantly associated with short-term exposure to an increase in DTV during past week and past month, with ORs (95% CI) = 0.72 (0.55–0.95) and 0.79 (0.64, 0.99) respectively for an IQR increase in DTV exposure during each time window. Moreover, long-term exposure to an increase in temperature during past 3 months was significantly associated with an elevated risk of long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients, with OR (95% CI) = 2.12 (1.44–3.14). However, no association was observed for short-term exposure to temperature during past week or past month or long-term exposure to DTV during past 3 months.

Table 4.

Associations between short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air temperature (T) and diurnal temperature variation (DTV) and long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients, with OR (95% CI) (n = 427).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) a | Adjusted OR (95% CI) b | |

|---|---|---|

| Past week | ||

| T | 0.91 (0.72, 1.16) | 0.92 (0.75, 1.14) |

| DTV | 0.69 (0.52, 0.90)d | 0.72 (0.55, 0.95)c |

| Past month | ||

| T | 1.02 (0.80, 1.30) | 1.03 (0.81, 1.32) |

| DTV | 0.78 (0.62, 0.96)c | 0.79 (0.64, 0.99)c |

| Past 3 months | ||

| T | 2.10 (1.43, 3.07)e | 2.12 (1.44, 3.14)e |

| DTV | 0.94 (0.83, 1.08) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.09) |

We further conducted the associations of short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution (Table 5 ) and temperature indicators (Table 6 ) with long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients stratified by personal factors including sex and age. We found that males and younger patients (<50 years) were more susceptible to both adverse effect of PM2.5, PM2.5-10, NO2, and/or CO exposure and protective effect of O3 exposure on long recovery duration (Table 5). Furthermore, we observed that females and older patients (≥50 years) were more sensitive to both protective effect of DTV exposure and adverse effect of temperature exposure on long recovery duration (Table 6).

Table 5.

Associations between short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution and long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients stratified by sex and age, with OR (95% CI) (n = 427).

| Sex |

Age (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 213) | Female (n = 214) | <50 (n = 249) | ≥50 (n = 178) | |

| Past week | ||||

| PM2.5 | 0.94 (0.56, 1.58) | 1.23 (0.72, 2.08) | 1.24 (0.82, 1.90) | 0.90 (0.48, 1.70) |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.29 (0.83, 2.00) | 1.36 (0.88, 2.11) | 1.49 (1.00, 2.23)a | 1.14 (0.69, 1.88) |

| PM10 | 0.74 (0.45, 1.22) | 1.48 (0.90, 2.43) | 1.19 (0.78, 1.83) | 0.87 (0.48, 1.56) |

| SO2 | 0.70 (0.46, 1.07) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.70) | 0.91 (0.60, 1.40) | 0.81 (0.50, 1.31) |

| NO2 | 1.14 (0.68, 1.89) | 1.28 (0.76, 2.14) | 1.44 (0.94, 2.20) | 1.00 (0.54, 1.83) |

| CO | 1.44 (0.87, 2.37) | 1.43 (0.89, 2.31) | 1.41 (0.94, 2.10) | 1.59 (0.80, 3.14) |

| O3 | 0.69 (0.39, 1.23) | 0.70 (0.43, 1.16) | 0.60 (0.36, 1.00)a | 0.75 (0.41, 1.36) |

| Past month | ||||

| PM2.5 | 2.32 (1.28, 4.22)b | 1.66 (0.89, 3.09) | 2.41 (1.40, 4.13)c | 1.42 (0.70, 2.87) |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.22 (0.70, 2.10) | 1.14 (0.73, 1.80) | 1.46 (0.93, 2.30) | 0.88 (0.52, 1.48) |

| PM10 | 1.03 (0.55, 1.94) | 1.41 (0.91, 2.17) | 1.90 (0.95, 3.81) | 0.95 (0.55, 1.65) |

| SO2 | 0.77 (0.44, 1.36) | 1.39 (0.74, 2.59) | 1.83 (0.55, 6.05) | 0.98 (0.49, 1.99) |

| NO2 | 2.27 (1.25, 4.13)b | 1.64 (0.93, 2.89) | 2.57 (1.52, 4.36)c | 1.16 (0.60, 2.25) |

| CO | 1.68 (1.01, 2.82)a | 1.44 (0.82, 2.53) | 1.72 (1.08, 2.73)a | 1.26 (0.64, 2.46) |

| O3 | 0.37 (0.21, 0.68)c | 0.47 (0.26, 0.83)b | 0.28 (0.15, 0.50)c | 0.64 (0.35, 1.17) |

| Past 3 months | ||||

| PM2.5 | 1.91 (1.06, 3.42)a | 1.05 (0.55, 2.02) | 1.49 (0.89, 2.50) | 1.34 (0.62, 2.89) |

| PM2.5-10 | 1.54 (0.83, 2.86) | 1.03 (0.61, 1.73) | 1.65 (1.02, 2.66)a | 0.75 (0.41, 1.38) |

| PM10 | 0.98 (0.47, 2.01) | 1.14 (0.67, 1.94) | 1.44 (0.66, 3.14) | 0.72 (0.37, 1.40) |

| SO2 | 0.77 (0.55, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.70, 1.45) | 0.89 (0.66, 1.20) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.35) |

| NO2 | 1.92 (1.00, 3.69)a | 0.95 (0.49, 1.83) | 1.81 (1.03, 3.21)a | 0.70 (0.31, 1.57) |

| CO | 1.39 (0.89, 2.17) | 1.05 (0.64, 1.72) | 1.38 (0.93, 2.04) | 0.88 (0.47, 1.63) |

| O3 | 1.13 (0.37, 3.44) | 1.81 (0.90, 3.65) | 1.08 (0.25, 4.54)a | 2.04 (0.87, 4.77) |

OR (95%CI) was estimated for per IQR increase in each air pollutant during different time window.

Models were adjusted for all the covariates in Table 1 and outdoor DTV exposure during each time window.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

Table 6.

Associations between short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air temperature (T) and diurnal temperature variation (DTV) and long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients stratified by sex and age, with OR (95% CI) (n = 427).

| Sex |

Age (years) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 213) | Female (n = 214) | <50 (n = 249) | ≥50 (n = 178) | |

| Past week | ||||

| T | 0.94 (0.63, 1.40) | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | 0.90 (0.68, 1.19) | 0.93 (0.65, 1.33) |

| DTV | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) | 0.65 (0.44, 0.96)a | 0.72 (0.50, 1.03) | 0.70 (0.46, 1.08) |

| Past month | ||||

| T | 0.90 (0.58, 1.40) | 1.10 (0.81, 1.50) | 0.89 (0.66, 1.21) | 1.70 (1.00, 2.90)a |

| DTV | 0.83 (0.59, 1.17) | 0.76 (0.57, 1.03) | 0.84 (0.64, 1.10) | 0.70 (0.49, 1.01)a |

| Past 3 months | ||||

| T | 1.81 (1.04, 3.15)a | 2.55 (1.43, 4.57)b | 2.54 (1.48, 4.34)c | 2.23 (1.18, 4.23)a |

| DTV | 0.99 (0.81, 1.21) | 0.93 (0.77, 1.12) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.18) | 0.88 (0.70, 1.11) |

OR (95%CI) was estimated for per IQR increase in each air pollutant during different time window.

Models were adjusted for all the covariates in Table 1 and outdoor CO exposure during each time window.

p ≤ 0.05.

p ≤ 0.01.

p ≤ 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the associations of short-term and long-term exposure to outdoor air pollution, temperature, and DTR with long recovery duration among COVID-19 patients from seven cities in China. We strikingly found that long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients was positively associated with short-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) including PM2.5, CO, and NO2 while was negatively associated with new air pollution (O3) during past week and past month. We further interestingly observed a protective effect of short-term exposure to DTV during past week and past month while an adverse effect of long-term exposure to temperature during past 3 months on long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients. Our findings indicate potentially different mechanisms underlying the role of different types of air pollution and temperature indicators exposure in critical time window on symptom severity and recovery duration among COVID-19 patients.

There are some strong advantages in this work. Firstly, we conducted a retrospective cohort study with a relatively large sample size for COVID-19 patients from seven cities during early stage of pandemic, which makes sure our results representative and reliable. Secondly, we are the first to comprehensively assessed the role of personal exposure to outdoor air pollution, temperature, and diurnal temperature range (DTR) during different time windows on long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients. Our striking findings may provide some strategies to effectively reduce and early prevent severe symptoms and long recovery duration for COVID-19 patients. Thirdly, we estimated personal exposure of outdoor air pollution at each patient's home address based on 48 ambient air quality monitoring stations at 7 seven cities with a high accuracy by setting both longitude and latitude to six decimal places, which can obtain extremely exact assessment of individual exposure. We calculated personal exposure to daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures reported from 72 meteorological monitoring stations from seven cities, which has a very high accuracy and good representativeness. Fourthly, we are the first to deeply assess and compare the susceptibility in the role of short-term and long-term exposure to air pollution and temperature indicators on long recovery duration between COVID-19 patients with different sex and age. Our novel findings can further identify a critically narrow timing window existing specific pollution source and heat stress which is the most harmful to the symptom's severity and recovery duration of COVID-19 patients.

We strikingly found that short-term exposure to TRAP (i.e., PM2.5, NO2, and CO) played a key role in long recovery duration among COVID-19 patients. Our finding is consistent with some previous studies. A recent review study showed that COVID-19 incidence and severity were significantly associated with TRAP including particulate matter (PM), NO2, and CO (Marquès and Domingo, 2022) A recent meta-analysis of 72 Chinese cities reported a stronger association between PM2.5 exposure and COVID-19 incidence within 14 days, indicating a lagged and short-term effect of fine particulate matter (Wang et al., 2020). Our study suggests that short-term exposure to PM2.5 particularly during past month significantly increased the risk of prolonged recovery in COVID-19 patients. A study in US found that exposure to PM2.5 during past was significantly associated with an increased COVID-19 mortality (Wu et al., 2020a, Wu et al., 2020b). The possible reason may be due to that PM2.5 is more likely to enter the body through the respiratory tract and accumulate in the body, with long-lasting effects. PM2.5 was a risk factor for the development of COVID-19 in an analysis of a large sample of 100,000 people from 355 cities in the Netherlands (Andrée, 2020). A previous study indicated that there are independent effects of traffic-related noise and air pollution on coronary heart disease mortality (Gan et al., 2012). They suggest that the concentration of pollutants may have a decisive influence on the development of the epidemic. There are several speculations on the mechanism in the association between particulate matter and COVID-19, one being the transmission of the virus through it (Moelling and Broecker, 2020). Some studies have provided evidence that COVID-19 virus particles are found in bergamot (Setti et al., 2020). Traffic and fuel emissions can produce NO2 and have chronic effects on human cardiovascular and respiratory systems (Adhikari and Yin, 2020). A German study used correlation analysis and wavelet transform coherence (WTC) methods to evaluate associations between NO2 for four health and mortality-related indicators of COVID-19 and found a significant correlation between NO2 and COVID-19 (Bashir et al., 2020b). A recent study examining the disruptive role of nitrogen dioxide in angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) proved the effects on viral cell receptors which was associated with the action of NO2 (Alifano et al., 2020). This provides a potential mechanism for COVID-19 patients who were affected by NO2. It has been shown that the incidence of COVID-19 was positively associated with NO2 in Wuhan (R2 = 0.329, p < 0.001) and Xiaogan (R2 = 0.158, p < 0.05), and that each 10 μg/m3 increase in NO2 (lag 0–14) was associated with a 6.94% increase in the daily number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases (Pansini, and Fornacca, 2020). A recent study found that the regional distribution of COVID-19 overlapped significantly with areas of high pollutant concentrations (Ogen, 2020). However, a study with univariate and multivariate analysis of 6529 cases from 28 regions in Japan showed that NO2 was not associated with an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases (Azuma et al., 2020). Due to the inconsistent findings, more studies on the association between TRAP and COVID-19 risk were further needed.

We interestingly observed that short-term exposure to some new pattern of air pollution (O3) significantly decreased the risk of long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients. A review indicated that ozone therapy can control inflammation and improve the activity of antiviral drugs during the treatment of covid-19 patients, and our study further supports this conclusion (Cattel et al., 2021). However, a recent review study concluded that there was a significant association between chronic exposure to O3 and the incidence/risk of COVID-19 cases, which is inconsistent with our study (Marquès and Domingo, 2022). The concentration of O3 in China increased dramatically over recent years (Li et al., 2020). The epidemic policy in China is different from most countries, which may have a heterogeneity. However, the potential mechanisms underlying the association between O3 exposure and COVID-19 risk are still unknown, which warrants further studies.

On the other hand, we newly detected a protective effect of short-term exposure to DTR while an adverse effect of long-term exposure to temperature on long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients. Few studies have shown the effect of the lag effect of DTR on the recovery duration of COVID-19 patients. Our study found a protective long-term lag effect of increased DTR on the long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients, possibly due to increased temperature differences and the tendency of people who are more likely to stay indoors in winter, which may reduce the outdoor transmission rate of COVID-19 virus and decrease exposure to air pollution. A Russian study also showed a decrease in the intensity of transmission of COVID-19 virus with a rise in DTR of about 6 °C and 90% of temperature seasonality at mean temperatures below 2 °C (Pramanik et al., 2022), which may support our study. Our study suggested that an increase in outdoor temperature increased the risk of long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients, which is inconsistent with a recent study indicating that the cooler temperatures had a positive association with the occurrence of new confirmed COVID-19 cases (Orak, 2022). However, our study period was mainly in January in Changsha with a low mean temperature of 10 °C, and thus an increase in temperature may enhance the activity of COVID-19 virus. Our findings can be supported by a Korean study that found an association between elevated temperatures and increased risk at a very low threshold of 8 °C (Hoang and Tran, 2021). Therefore, we suggest controlling for the temperature to promote disease recovery.

We further identified a sex- and age-specific susceptibility in the role of short-term and long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and temperature indicators on long recovery duration for COVID-19 patients. In our sensitivity analysis, men were more sensitive to contaminants compared to women, possibly because ACE2 is a receptor that binds to human COVID-19, which is at a low level in healthy individuals while is elevated in men during aging (Abobaker and Raba, 2021). Some studies have observed that men with heart failure, which is also an end-stage symptom of COVID-19, have higher plasma levels of ACE2 than women with the same disease (de Loyola et al., 2021; Sama et al., 2020). The susceptibility observed in young people than older people may depend on the following reasons. Firstly, young people are under more financial stress, and they are less likely to go to better hospitals or obtain better ambulance treatment. Secondly, young people have heavier working stress compared to older people, leading to a decrease in physical resistance and immunity. This may be related to the fact that younger people enjoy more outdoor activities, dinners, and human communication than older people, and thus they are exposed to ambient air pollution for a longer time. It is also necessary to investigate whether some chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in older people may modify the association between environmental factors and COVID-19 epidemic.

There are several limitations in this study. Firstly, we did not consider economic factor which is an important factor associated with the recovery duration of COVID-19 patients. Since our sample was mainly collected in the hospitals, and the data on the economic status of each patient and their families was lacking as it is a private question in China. Secondly, we did not consider indoor air pollution or temperature. However, there is a high I/O ratio of air pollution and temperature during transient seasons (spring and autumn) and consistently similar levels of indoor air pollution and temperature between different families during extreme seasons (summer and winter) by frequently closing the windows and opening air conditioning with setting similar temperature in China, and thus the lacking data on indoor air pollution and temperature would not significantly bias the results in this study. Thirdly, we did not consider whether different treatment or drug use may influence our analysis in this study.

5. Conclusions

We evaluated the effects of short-term and long-term exposure to ambient air pollution, temperature, and DTR on the long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients. We found that long recovery duration of COVID-19 patients was positively associated with short-term exposure to TRAP (PM2.5, NO2, and CO) while was negatively associated with short-term exposure to new pattern of air pollution (O3). We further observed that long-term exposure to an increase in temperature significantly increased the risk of long recovery duration in COVID-19 patients, while that short-term exposure to DTV decreased the risk. Moreover, we identified that male and younger COVID-19 patients were more susceptible to both adverse effect of TRAP and protective effect of O3 exposure on long recovery duration, while female and older patients were more sensitive to adverse effect of temperature and protective effect of DTV exposure on long recovery duration. Our study may provide some suggestions for the improvement of public health policy, which has a great implication for effective reduction and early prevention of long recovery duration among COVID-19 patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the academic ethics committee of XiangYa Hospital, Central South University, and all participants. A written consent was obtained from all the surveyed children, and their parents or guardians for all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Zijing Liu collected and analysed the data and drafted the initial manuscript. Qi Liang collected the data and reviewed the manuscript. Hongsen Liao collected and analysed the data. Wenhui Yang collected and analysed the data. Chan Lu conducted the study, conceptualized, designed, and performed the study, collected the data, supervised the data analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42007391 and 42277432) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2021JJ30813). We also appreciate the help from the collaborated teachers and students at Central South University in the data arrangement and Database establishment.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abobaker A., Raba A.A. Does COVID-19 affect male fertility? World J. Urol. 2021;39:975–976. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03208-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A., Yin J. Short-term effects of ambient ozone, PM2.5, and meteorological factors on COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths in Queens, New York. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:4047. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alifano M., Alifano P., Forgez P., Iannelli A. Renin-angiotensin system at the heart of COVID-19 pandemic. Biochimie. 2020;174:30–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrée B.P.J. Incidence of COVID-19 and connections with air pollution exposure: evidence from The Netherlands. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.27.20081562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K., Kagi N., Kim H., Hayashi M. Impact of climate and ambient air pollution on the epidemic growth during COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Environ. Res. 2020;190 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B., Komal B., Bashir M.A., Tan D., Bashir M. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Benghoul M., Numan U., Shakoor A., Komal B., Bashir M.A., et al. Environmental pollution and COVID-19 outbreak: insights from Germany. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2020;13:1385–1394. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00893-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevelander M., Mayette J., Whittaker L.A., Paveglio S.A., Jones C.C., Robbins J., et al. Nitrogen dioxide promotes allergic sensitization to inhaled antigen. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3680–3688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattel F., Giordano S., Bertiond C., Lupia T., Corcione S., Scaldaferri, et al. Ozone therapy in COVID-19: a narrative review. Virus Res. 2021;291 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wang M., Huang C., Kinney P.L., Anastas P.T. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Lancet Planet. Health. 2020;4:e210–e212. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Loyola M.B., Dos Reis T.T.A., de Oliveira G.X.L.M., da Fonseca Palmeira J., Argañaraz G.A., Argañaraz E.R. Alpha‐1‐antitrypsin: a possible host protective factor against COVID‐19. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021;31 doi: 10.1002/rmv.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demongeot J., Flet-Berliac Y., Seligmann H. Temperature decreases spread parameters of the new Covid-19 case dynamics. Biology. 2020;9:94–103. doi: 10.3390/biology9050094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Lu C., Ou C., Liu W. Effects of early life exposure to outdoor air pollution and indoor renovation on childhood asthma in China. Build. Environ. 2015;93:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Doiron D., de Hoogh K., Probst-Hensch N., Fortier I., Cai Y., De Matteis S., Hansell A.L. Air pollution, lung function and COPD: results from the population-based UK Biobank study. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;54 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02140-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dublineau A., Batéjat C., Pinon A., Burguière A.M., Leclercq I., Manuguerra J.C. Persistence of the 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus in water and on non-porous surface. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorito S., Soligo M., Gao Y., Ogulur I., Akdis C.A., Bonini S. Is the epithelial barrier hypothesis the key to understanding the higher incidence and excess mortality during COVID‐19 pandemic? The case of Northern Italy. Allergy. 2022;77:1408–1417. doi: 10.1111/all.15239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor L.S., Friedman J., Spencer C.N., Cagney J., Arrieta A., Herbert M.E., et al. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: a comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021. TheLancet. 2022;399:2381–2397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan W.Q., Davies H.W., Koehoorn M., Brauer M. Association of long-term exposure to community noise and traffic-related air pollution with coronary heart disease mortality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012;175:898–906. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T., Tran T.T.A. Ambient air pollution, meteorology, and COVID‐19 infection in Korea. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:878–885. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannidis C., Mostert C., Hentschker C., Voshaar T., Malzahn J., Schillinger G., et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: an observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:853–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Shin J., Lim Y.H., Honda Y., Hashizume M., Guo Y.L., et al. Comprehensive approach to understand the association between diurnal temperature range and mortality in East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;539:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.08.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L., Garg S., O'Halloran A., Whitaker M., Pham H., Anderson E.J., et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the US coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization surveillance network (COVID-NET) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;72:e206–e214. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korompoki E., Gavriatopoulou M., Fotiou D., Ntanasis‐Stathopoulos I., Dimopoulos M.A., Terpos E. Late‐onset hematological complications post COVID‐19: an emerging medical problem for the hematologist. Am. J. Hematol. 2022;97:119–128. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao C.M., Hsieh N.H., Chio C.P. Fluctuation analysis-based risk assessment for respiratory virus activity and air pollution associated asthma incidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;409:3325–3333. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Li Q., Huang L., Wang Q., Zhu A., Xu J., et al. Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River Delta Region: an insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;732 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li T., Wang H. Treatment and prognosis of COVID-19: current scenario and prospects. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021;21:3–12. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Yang W., Liu Z., Liao H., Li Q., Liu Q. Effect of preconceptional, prenatal and postnatal exposure to home environmental factors on childhood pneumonia: a key role in early life exposure. Environ. Res. 2022;214 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.114098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Liu Z., Liao H., Yang W., Li Q., Liu Q. Effects of early life exposure to home environmental factors on childhood allergic rhinitis: modifications by outdoor air pollution and temperature. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022;244 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquès M., Domingo J.L. Positive association between outdoor air pollution and the incidence and severity of COVID-19. A review of the recent scientific evidences. Environ. Res. 2022;203 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moelling K., Broecker F. Air microbiome and pollution: composition and potential effects on human health, including SARS coronavirus infection. J Environ Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/1646943. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naseef H., Damin Abukhalil A., Orabi T., Joza M., Mashaala C., Elsheik M., et al. Evaluation of the health situation among recovered cases of COVID-19 in west bank, Palestine, and their onset/recovery time. J Environ Public Health. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/3431014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogen Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orak N.H. Effect of ambient air pollution and meteorological factors on the potential transmission of COVID-19 in Turkey. Environ. Res. 2022;212 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansini R., Fornacca D. Initial evidence of higher morbidity and mortality due to SARS-CoV-2 in regions with lower air quality. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.04.20053595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.E., Son W.S., Ryu Y., Choi S.B., Kwon O., Ahn I. Effects of temperature, humidity, and diurnal temperature range on influenza incidence in a temperate region. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14:11–18. doi: 10.1111/irv.12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinon A., Vialette M. Survival of viruses in water. Intervirology. 2018;61:214–222. doi: 10.1159/000484899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik M., Udmale P., Bisht P., Chowdhury K., Szabo S., Pal I. Climatic factors influence the spread of COVID-19 in Russia. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022;32(4):723–737. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2020.1793921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J.D., Karim S.S.A., Aknin L., Allen J., Brosbøl K., Colombo F., et al. The Lancet Commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2022;400:1224–1280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01585-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sama I.E., Ravera A., Santema B.T., Van Goor H., Ter Maaten J.M., Cleland J.G., et al. Circulating plasma concentrations of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in men and women with heart failure and effects of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone inhibitors. Eur. Heart J. 2020;41:1810–1817. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setti L., Passarini F., De Gennaro G., Barbieri P., Perrone M.G., Borelli M., et al. SARS-Cov-2RNA found on particulate matter of Bergamo in Northern Italy: first evidence. Environ. Res. 2020;188 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan A., Wong F., Couch L.S., Wang B.X. Cardiac complications of COVID-19 in low-risk patients. Viruses. 2022;14:1322. doi: 10.3390/v14061322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaira L.A., De Vito A., Lechien J.R., Chiesa‐Estomba C.M., Mayo‐Yàñez M., Calvo‐Henrìquez C., et al. New onset of smell and taste loss are common findings also in patients with symptomatic COVID‐19 after complete vaccination. Laryngoscope. 2022;132:419–421. doi: 10.1002/lary.29964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Liu J., Fu S., Xu X., Li L., Ma Y., et al. An effect assessment of airborne particulate matter pollution on COVID-19: a multi-city study in China. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.20060137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Jing W., Liu J., Ma Q., Yuan J., Wang Y., et al. Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Nethery R.C., Sabath M.B., Braun D., Dominici F. Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.