Abstract

The fimbria-associated MrkD1P protein mediates adherence of type 3 fimbriate strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae to collagen type V. Currently, three different MrkD adhesins have been described in Klebsiella species, and each possesses a distinctive binding pattern. Therefore, the binding abilities of mutants possessing defined mutations within the mrkD1P gene were examined in order to determine whether specific regions of the adhesin molecule were responsible for collagen binding. Both site-directed and chemically induced mutations were constructed within mrkD1P, and the ability of the gene products to be incorporated into fimbrial appendages or bind to collagen was determined. Binding to type V collagen was not associated solely with one particular region of the MrkD1P protein, and two classes of nonadhesive mutants were isolated. In one class of mutants, the MrkD adhesin was not assembled into the fimbrial shaft, whereas in the second class of mutants, the adhesin was associated with fimbriae but did not bind to collagen. Both hemagglutinating and collagen-binding activities were associated with the MrkD1P molecule, since P pili and type 3 fimbriae carrying adhesive MrkD proteins exhibited identical binding properties.

The MrkD1P polypeptide is the type 3 fimbrial adhesin produced by most isolates of Klebsiella oxytoca and a minority of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (21). When assembled into the fimbrial appendage, this molecule mediates adherence to type V collagen, in contrast to the MrkD1C adhesin, which binds to both type IV and type V collagen (22). It has been demonstrated that bacteria expressing the MrkD1P fimbrial adhesin can bind to the basement membrane region of human lung tissue as well as to basolateral margins of renal tubular cells (8, 10, 24, 25). Therefore, it has been suggested that type 3 fimbriae may facilitate colonization of denuded and damaged epithelial surfaces, resulting in the colonization of debilitated patients in the hospital environment (3, 25).

As is true for many other fimbrial appendages expressed by enteric bacteria, type 3 fimbriae are encoded by a cluster of genes, the mrk gene cluster, that encode polypeptides necessary for the correct assembly of the fimbrial structures on the surfaces of the bacteria (1, 3). In addition, mrk genes responsible for regulating fimbrial expression are also located within the gene cluster (3). The MrkD adhesin is assembled into the fimbrial shaft, composed of the major and predominant subunit of MrkA. A functional adhesin can also be assembled into heterologous fimbriae, such as the P pili of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, when recombinant plasmids carrying the mrkD gene are present with the pap gene cluster (10). Therefore, the assembly apparatus for type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella species may be related to that of P pili. In fact the C-terminal regions of both MrkD1C and MrkD1P possess amino acid sequence motifs that are conserved among several fimbrial adhesins (7). These domains are believed to play a role in the folding and assembly of the adhesins.

A comparison of the amino acid sequences of cloned MrkD adhesins indicated that the N-terminal regions of these molecules exhibit the greatest degree of variability (22). Consequently, observed differences in the receptor-binding specificities of type 3 fimbriae may be a function of specific domains within the MrkD adhesin. For the type 1 fimbriae of both E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium, as well as the E. coli P pili, investigations have demonstrated that binding to target cells is influenced by amino acids which make up the N-terminal regions of the respective adherence molecules (12, 23). Therefore, we investigated the abilities of defined mutations within the mrkD1P gene to influence binding to the type V collagen receptor. Two classes of nonbinding mutants were isolated: one class was defined by the presence of adhesin in the fimbrial shaft, whereas the second class did not assemble MrkD molecules into the fimbrial appendage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The Klebsiella strains and recombinant plasmids used in these studies are listed in Table 1 and have been previously described (22). E. coli transformants carrying the cloned pap gene cluster on pDC1 and the papG-negative derivative, pDC17, have been characterized in detail elsewhere (2, 8). Transformations were performed by electroporation with an ECM600 pulse generator (BTX Inc., San Diego, Calif.), and transformants were selected on L agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Expression of type 3 fimbriae by Klebsiella transformants was achieved following growth at 37°C on glycerol-Casamino Acids agar as previously described (4).

TABLE 1.

Bacteria and recombinant plasmids used in this study

| Bacterium or plasmid | Relevant genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae IApc35 | Strain lacking a functional mrkD gene; type 3 fimbriate and nonadhesive | 22 |

| E. coli HB101(pDC17) | Strain transformed with a plasmid carrying pap gene cluster lacking papG; P piliated and nonadhesive | 8 |

| Recombinant plasmids | ||

| pFK52 | Plasmid carrying functional mrkD1P gene | 8 |

| pTS52 | BamHI/HindIII DNA fragment carrying the mrkD1P gene cloned into pBluescript KS | This study |

| pTS68, pTS71, pTS72, pTS76 | Derivatives of pFK52 carrying site-directed mutations in mrkD1Pa | This study |

| pTS73, pTS74, pTS78, pTS79 | Derivatives of pFK52 carrying hydroxylamine-induced mutations in mrkD1Pa | This study |

Sites of the mutations are indicated in Fig. 1.

DNA manipulations.

Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from commercial sources and used according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. The oligonucleotides used to generate site-directed mutations were synthesized by Life Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, Md.), and are listed in Table 2. The method of Gibbs and Zoller (6) was modified to change charged amino acids (Asp, Glu, Arg, Lys, and His) to alanine. Single-stranded DNA template was isolated from E. coli CJ236 (15) transformed with pTS52 following infection with the helper phage M13K07 (2 × 107 PFU/ml). The phagemids were grown for 2 h at 37°C with shaking and amplified in the presence of kanamycin for a further 18 h at 37°C.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used to construct site-specific mutations

| Nucleotide sequencea | Site(s) (change in amino acid sequence) | Plasmid carrying mutation |

|---|---|---|

| ATTGGTTTAGCATTCTCAGCAGCAGGGGCGATCAGTATG | 101, 104–105 (R, R-K)b | pTS68 |

| CTCCATGCGCGCTTCGCAGCAGCAGCGCCGACTACCAGT | 299–301 (Y-Q-Y) | pTS71 |

| GATATAGGCACGATTGCAGCAGCTGCATTAAAAGGGGTGGGG | 194–195, 197 (K-R, D) | pTS72 |

| ATTTATGTTACATGTGCAGCAGCAACTACTCTGAAATCA | 68–70 (D-R-N) | pTS76 |

Sites of mutations are underlined.

Amino acids changed to alanine.

The oligonucleotides used for the site-directed mutagenesis contained at least 15 homologous bases flanking each side of the mutations to be introduced into mrkD1P. Fifty picomoles of the phosphorylated oligonucleotide was mixed with 0.25 pmol of single-stranded uracil-containing template DNA and 1 μl of annealing buffer (200 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.4], 20 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl) and brought to a final volume of 10 μl. After the mixture was heated at 70°C for 10 min with subsequent cooling at ambient temperature for 30 min, 1 μl of 10× synthesis buffer (5 mM dATP, 5 mM dCTP, 5 mM dGTP, 5 mM dTTP, 10 mM ATP, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dithiothreitol), T4 DNA ligase (5 U), and Sequenase (United States Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) were added. Following a further incubation at ambient temperature for 15 min, the extension of the primer was performed at 37°C for 120 min. Tris-EDTA was then added to a final volume of 50 μl, and the DNA was precipitated, dried, and resuspended in sterile distilled water prior to electroporation into E. coli DH12S (16).

Plasmid DNA was purified from transformants and cloned into the BamHI/HindIII sites of pACYC184. Thus, plasmids containing mutations within mrkD1P are identical to pFK52 (8) containing the parental gene with the exception of the sites of the mutations. All of the mutations were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis to verify that only the desired mutations were present.

Hydroxylamine mutagenesis.

Chemical mutagenesis of mrkD1P, carried on pFK52, was performed as described in detail elsewhere (17). Briefly, plasmid DNA was suspended in a solution containing 100 μl of 0.5 M KPO4–5 mM EDTA (pH 6.0), 200 μl of 1 M NH2OH, and 200 μl of distilled water. Following incubation at 37°C for 12 to 18 h, the solution was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 4 h at 4°C. Following precipitation of the DNA, the plasmid was resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer in a volume sufficient to concentrate the DNA approximately 50-fold. This plasmid preparation was subsequently used to transform E. coli(pDC17) or K. pneumoniae IApc35.

Transformants prepared with the hydroxylamine-treated plasmid DNA were plated on solid media, and nonhemagglutinating colonies were detected as follows. Plates containing approximately 100 to 150 colonies after incubation at 37°C were flooded with 5 ml of a 1% solution of tanned erythrocytes (20). After the plates were gently rocked for 2 to 5 min, hemagglutinating bacteria were detected by the presence of a margin of erythrocytes surrounding the bacterial colony, whereas no erythrocytes could be observed adhering to nonhemagglutinating mutants. Colonies exhibiting the latter phenotype were immediately plated to fresh medium, and the lack of type 3-mediated mannose-resistant Klebsiella-like hemagglutination (MR/K HA) activity was confirmed by standard techniques (9, 19, 20). The pFK52 derivatives were isolated from these mutants, and the sites of mutations were identified by DNA sequence analysis of the mrkD1P genes carried by these plasmids.

Detection and purification of type 3 fimbriae.

Type 3 fimbriate and MR/K HA-positive bacteria were detected with tannic acid-treated erythrocytes as described in detail elsewhere (9, 20). The presence of fimbrial appendages on the surfaces of bacteria was detected with monospecific fimbrial antiserum as previously described (8). Purified fimbriae were prepared according to procedures previously described by our group (5).

The presence of the MrkD1P adhesin in purified fimbrial preparations was determined by using anti-MrkD1P serum and Western immunoblotting analysis. The antiserum was prepared against a synthetic polypeptide representing the first 10 amino acids of the mature MrkD1P molecule. The procedure has been described in detail elsewhere, and it will detect the adhesin molecule in purified fimbrial appendages (22).

Collagen-binding activity of fimbriae.

The ability of fimbriate bacteria or cell-free fimbrial suspensions to bind to type V collagen was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described (22).

RESULTS

Characterization of mrkD1P mutants.

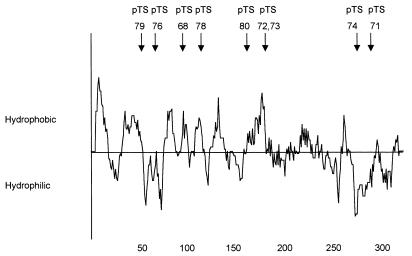

The nucleotide sequences encoding three hydrophilic regions and one hydrophobic region of the MrkD1P adhesin were selected as targets for site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 1). The entire nucleotide sequences of the four mrkD1P genes possessing the site-directed mutations, carried on plasmids pTS68, pTS71, pTS72, or pTS76, were determined. In all cases, the only differences between the sequences of these genes and those of the parental allele were at the sites of the introduced mutations. The mutations carried on plasmids pTS68, pTS71, pTS72, and pTS76 confer the following substitutions, respectively, on these plasmids: R,R-K(101, 104–105)AAA; Y-Q-Y(299–301)AAA; K-R,D(194–194, 197)AAA; and D-R-N(68–70)AAA.

FIG. 1.

Hydropathicity profile of MrkD1P. The numbers at the bottom of the plot indicate the length, in amino acids, of the polypeptide. The arrows above the plot indicate the sites of the mutations characterized in this study.

Following chemical mutagenesis of pFK52, a plasmid carrying only the mrkD gene of the gene cluster, and subsequent introduction of this plasmid into E. coli(pDC17), approximately 0.3% of the colonies examined were observed not to be surrounded by a margin of erythrocytes. Five transformants possessing base pair transitions at five different sites were further examined (Fig. 1). As for the site-directed mutations, the entire nucleotide sequences of the mrkD1P genes were determined and only single-site mutations were detected. The base pair transitions carried on pTS73, pTS74, pTS78, pTS79, and pTS80 result in the following amino acid substitutions: R195Q, H277Y, G121D, T521, and T1641.

MR/K HA activity of mutants.

Because pFK52 carrying the parental mrkD1P allele can be used to complement a recombinant E. coli strain expressing the heterologous P pilus shaft (8), the ability of mrkD1P mutations to facilitate hemagglutinating activity in this strain was observed (Table 3). With the exception of the gene carried on plasmid pTS76, all mutations within the mrkD1P gene resulted in the elimination of the characteristic MR/K HA phenotype. Even at very high concentrations of bacteria (>1.5 × 1010/ml) no HA was observed. Plasmid pTS76 carries three alanine substitutions within the N-terminal region of the MrkD adhesin (DRN76AAA) and retains the ability to agglutinate tanned erythrocytes. However, the minimum number of bacteria required to mediate a visible HA reaction was approximately 16-fold greater than that required by the strain producing the wild-type MrkD1P molecule (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Fimbriation and MR/K HA activity of transformants

| Transformant | MR/K HA | MR/K HA titera | Presence of MrkD on fimbriaeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli(pDC17) | |||

| pFK52 | +c | 5.8 × 107 | ND |

| pTS68 | − | −d | ND |

| pTS71 | − | − | ND |

| pTS72 | − | − | ND |

| pTS73 | − | − | ND |

| pTS74 | − | − | ND |

| pTS76 | + | 9.4 × 108 | ND |

| pTS78 | − | − | ND |

| pTS79 | − | − | ND |

| pTS80 | − | − | ND |

| K. pneumoniae IApc35 | |||

| pFK52 | + | 2.1 × 107 | + |

| pTS68 | − | ND | − |

| pTS71 | − | ND | − |

| pTS72 | − | ND | − |

| pTS73 | − | ND | + |

| pTS74 | − | ND | + |

| pTS76 | + | 6.3 × 108 | + |

| pTS78 | − | ND | + |

| pTS79 | − | ND | + |

| pTS80 | − | ND | + |

Titer expressed as the lowest concentration (in CFU per milliliter) of bacteria causing visible HA.

Presence of adhesin as determined by Western blot analysis of purified fimbrial preparations (see Materials and Methods). ND, not determined.

+, present; −, absent.

Bacterial concentrations of >1.5 × 1010 CFU ml−1 did not cause HA.

K. pneumoniae IApc35 is a fimbriate and nonadhesive derivative of K. pneumoniae IA565, and the lack of HA activity is due to the loss of the mrkD1P gene (22). Following transformation with pFK52, MR/K HA activity is restored in K. pneumoniae IApc35 by complementation of the chromosomal mrk gene cluster carrying a defective mrkD allele (8, 22). The ability of pFK52 derivatives to restore MR/K HA is shown in Table 3. As for E. coli(pDC17) transformants, only Klebsiella strains carrying plasmid pTS76 demonstrated MR/K HA binding. However, since K. pneumoniae IApc35 is strongly fimbriate, all the K. pneumoniae transformants react with type 3 fimbria-specific antiserum.

Collagen binding by MrkD1P derivatives.

Transformants possessing the mrkD1P derivatives were assayed for their ability to bind type V collagen. Only K. pneumoniae IApc35 transformants carrying pFK52 or pTS76 were observed to adhere to collagen molecules (Table 4). We have previously shown that K. pneumoniae IApc35 is fimbriate, and all transformants retained the ability to react with fimbria-specific antiserum (8). Fimbriae purified from pFK52 and pTS76 transformants also adhered to collagen molecules, whereas those isolated from the remaining strains did not (Table 4). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of purified fimbrial preparations indicated that the collagen-binding and non-collagen-binding appendages had identical molecular weights. Also, electron microscopy indicated no observable morphological differences between fimbrial preparations. No binding to collagen types II or IV, laminin, or fibronectin was detected with any of the bacterial strains.

TABLE 4.

Type V collagen-binding activity of transformants

| K. pneumoniae IApc35 transformant | Binding to collagena

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Type V | Type IV | |

| pFK52 | + | − |

| pTS68 | − | − |

| pTS71 | − | − |

| pTS72 | − | − |

| pTS73 | − | − |

| pTS74 | − | − |

| pTS76 | + | − |

| pTS78 | − | − |

| pTS79 | − | − |

| pTS80 | − | − |

Adherence to extracellular proteins was determined as previously described (22). +, present; − absent.

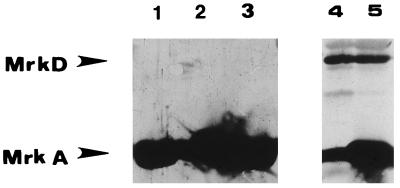

Assembly of MrkD1P into type 3 fimbriae.

MrkD1P-specific antiserum was used to detect the presence of the adhesin in purified fimbrial preparations. Western blots of representative isolates are shown in Fig. 2, and the results are summarized in Table 3. When fimbriae purified from Klebsiella transformants were used, all the fimbrial preparations possessed the MrkA subunit (Fig. 2). Fimbriae purified from K. pneumoniae IApc35 transformed with pFK52, pTS79, pTS76, pTS78, pTS80, pTS73, or pTS74 were found to possess a seroreactive MrkD1P molecule (Table 3). No 34-kDa MrkD1P polypeptide was detected by immunoblotting fimbrial preparations from pTS68, pTS71, or pTS72 transformants even in the presence of large amounts of the MrkA fimbrial subunit (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblots of purified type 3 fimbriae from K. pneumoniae IApc35 transformants. The gels were probed with anti-type 3 fimbria-specific serum to detect the MrkA major subunit, stripped, and subsequently probed with the anti-MrkD1P serum. Lanes 1, 2, and 3 include fimbriae from transformants possessing pTS68, pTS71, and pTS72, respectively, and were overloaded with fimbrial proteins in order to demonstrate the absence of MrkD1P in these samples. Lanes 4 and 5 include fimbriae from pTS76 and pTS78.

A 34-kDa polypeptide was detected in fimbrial preparations from E. coli(pDC17) transformed with pFK52, pTS79, pTS76, pTS78, pTS80, pTS73, or pTS74. No MrkA subunit polypeptide was detected in these strains. No detectable polypeptide that reacted with the anti-MrkD1P serum was associated with transformants possessing pTS68, pTS72, or pTS71 (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that the MrkD1P polypeptide associated with type 3 fimbrial expression in some strains of Klebsiella mediates the mannose-resistant agglutination of tanned erythrocytes and attachment to collagen type V (22, 24). This specific adhesin is produced by most strains of K. oxytoca and less frequently by isolates of K. pneumoniae (21, 22). The MrkD1P adhesin is encoded by a plasmid-borne gene, in contrast to MrkD1C, which is produced by most fimbriate strains of K. pneumoniae, is found on the chromosome, and mediates adherence to both collagen type IV and type V (22). A comparison of the amino acid sequences of the two fimbria-associated proteins indicated significant differences in their amino acid sequences, particularly in the N-terminal regions (22). Therefore, we decided to construct and characterize a number of mutations within mrkD1P in order to determine whether specific regions of the molecule are associated with binding activity.

Both site-directed and random mutagenesis procedures were used to construct nonadhesive MrkD1P molecules. Two classes of mutants were identified, and the mutations in both resulted in the inability to bind to target molecules. In the first class, the MrkD polypeptide could be assembled into the fimbrial shaft, whereas the second group of mutants could not incorporate the mutated adhesin into a fimbrial appendage. Three of the four mutations produced by alanine-substitution mutagenesis, carried on pTS68, pTS72, and pTS71 (Table 3), resulted in the inability of transformants to assemble the MrkD into type 3 fimbriae. The lack of incorporation into the fimbrial shaft could occur at one of several stages during fimbrial assembly. For example, these mutant adhesins may not be efficiently transported across the bacterial membranes to the site of fimbrial assembly or the mutation could reduce productive interaction with the subunit MrkA protein. This interaction may be directly with the MrkA subunit, or it could involve an as-yet-unidentified additional fimbrial protein. The mutation on plasmid pTS71 is located in a C-terminal hydrophobic region of MrkD1P, and similar regions of fimbrial adhesins have been postulated to be involved in protein-protein interactions during fimbrial biogenesis (11–13). The mutations carried on pTS68 and pTS72 were constructed in hydrophilic domains located in the middle of MrkD1P. The amino acids located at these sites are conserved in all three MrkD molecules characterized to date, even though each exhibits a different binding specificity (22). Consequently, this region of the molecule may function in facilitating MrkD interaction with other fimbrial proteins during assembly rather than influencing the recognition of a specific target molecule.

The mutation carried on plasmid pTS76 results in decreased but detectable binding activity by type 3 fimbriae. A hydropathy plot of the MrkD1P molecule carrying this mutation compared to that produced by the parental strain indicates a significant decrease in hydrophilicity only in the N-terminal region at the site of the mutation. Fimbriae isolated from bacteria carrying this mutation did not appear to be different from those purified from strains carrying the parental allele. By electron microscopy (data not shown), both fimbrial preparations were structurally identical, and by immunoblotting, both contained equivalent amounts of MrkD1P. Therefore, the observed change in binding activity of the MrkD1P encoded by the gene on pTS76 is not due to alterations in fimbrial morphology or major changes in the relative concentrations of adhesin and fimbrial subunit. The decrease in receptor-binding activity associated with the adhesin encoded by the gene on pTS76 appears to be due to the change in hydrophilicity.

All the chemically-derived mutations in mrkD1P were selected based on their inability to encode a functional hemagglutinin. However, the sites of the mutations span the length of the MrkD polypeptide and are not restricted to one specific region. Also, none of the mutations prevented the adhesin from being incorporated into the fimbrial shaft. Consequently, the lack of hemagglutinating activity imparted by the defective MrkD1P polypeptide as a result of base pair transitions is not associated with a significant change in adhesin assembly. Of particular interest is the presence of the MrkD1P molecule in fimbriae prepared from pTS73 transformants, whereas it is absent in pTS72 transformants. Therefore, the substitution of three alanine residues at positions 194, 195, and 197 (pTS72) is sufficient to impair MrkD1P assembly into fimbriae whereas a transition at position 195 (pTS73) is not. It is possible that a change in the folding of the MrkD1P molecule encoded by pTS72 is more likely to occur than that encoded by pTS73. Such a change would be more likely to affect the ability of the pTS72-encoded MrkD1P to be assembled into growing fimbrial appendages. Loss of HA also resulted in loss of collagen binding, and therefore, the MrkD1P adhesin is responsible for binding to receptors on both substrates, as previously reported (10, 22, 24). A molecular characterization of the MrkD1P receptor has yet to be reported, and it is possible that a common motif is associated with the two different receptors found on the erythrocytes and collagen.

The results of our studies indicate that amino acids of the MrkD1P adhesin that are necessary for substrate binding specificity are located throughout the length of the molecule. Similar results have been reported for the PapG adhesin of P pili (14), suggesting that a small discrete linear region of either adhesin is not solely responsible for binding activity. Also, the amino acids found to be necessary for HA or collagen binding have variable physical properties. Hydrophilic amino acids are associated with receptor-binding specificity, since these molecules are most likely to be exposed on the surface of the adhesin. In addition, charged molecules are less likely to be buried in the hydrophobic core of the protein. However, some of the amino acids observed to be critical for MrkD1P activity are not hydrophilic. The presence of hydrophobic sites and their role in the stabilization of interacting binding sites has previously been implicated in bacterial adherence mechanisms (18). Consequently, changes in hydrophobic, noncharged amino acids of the MrkD1P adhesin may influence the ability of the fimbria-associated MrkD1P to recognize a receptor molecule.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen B L, Gerlach G F, Clegg S. Nucleotide sequence and functions of mrk determinants necessary for expression of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:916–920. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.916-920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clegg S. Cloning of genes determining the production of mannose-resistant fimbriae in a uropathogenic strain of Escherichia coli belonging to serogroup O6. Infect Immun. 1982;38:739–744. doi: 10.1128/iai.38.2.739-744.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clegg S, Korhonen K T, Hornick B D, Tarkkanen A-M. Type 3 fimbriae of the Enterobacteriaceae. In: Klemm K P, editor. Fimbriae: adhesion, genetics, biogenesis, and vaccines. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlach G F, Allen B L, Clegg S. Molecular characterization of the type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3547–3553. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3547-3553.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerlach G-F, Clegg S. Cloning and characterization of the gene cluster encoding type 3 (MR/K) fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;49:377–383. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbs C S, Zoller M J. Rational scanning mutagenesis of a protein kinase identifies functional regions involved in catalysis and substrate interactions. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8923–8931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardeau J P, Bertin Y. Pilins of fimbrial adhesins of different member species of Enterobacteriaceae are structurally similar to the C-terminal half of adhesin proteins. FEBS Lett. 1995;357:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hornick D B, Allen B L, Horn M A, Clegg S. Adherence to respiratory epithelia by recombinant Escherichia coli expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbrial gene products. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1577–1588. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1577-1588.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hornick D B, Allen B L, Horn M A, Clegg S. Fimbrial types among respiratory isolates belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1795–1800. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.1795-1800.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornick D B, Thommandru J, Smits W, Clegg S. Adherence properties of an mrkD-negative mutant of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.2026-2032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hultgren S J, Lindberg F, Magnusson G, Koglberg J, Tennent J M, Normark S. The PapG adhesin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli contains separate regions for receptor binding and for the incorporation into the pilus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4357–4361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hultgren S J, Normark S. Chaparone-assisted assembly and molecular architecture of adhesive pili. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:383–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.002123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultgren S J, Normark S. Biogenesis of the bacterial pilus. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1991;1:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klann A G, Hull R A, Palzkill T, Hull S I. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis reveals residues involved in binding of pap3-encoded pili. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2312–2317. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2312-2317.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunkel T A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J J, Smith M, Jessee J, Bloom F. DH11S: an Escherichia coli strain for preparation of single-stranded DNA from phagemid vectors. BioTechniques. 1992;12:718–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ofek I, Doyle R J. Bacterial adhesion to cells and tissues. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall, Inc.; 1994. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Old D C, Adegbola R A. Antigenic relationships among type-3 fimbriae of Enterobacteriaceae revealed by immunoelectronmicroscopy. J Med Microbiol. 1985;20:113–121. doi: 10.1099/00222615-20-1-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Old D C, Tavendale A, Senior B W. A comparative study of the type-3 fimbriae of Klebsiella species. J Med Microbiol. 1985;20:203–214. doi: 10.1099/00222615-20-2-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurtz T A, Hornick D B, Korhonen T K, Clegg S. The type 3 fimbrial adhesin gene (mrkD) of Klebsiella species is not conserved among all fimbriate strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4186–4191. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4186-4191.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schurtz Sebghati T A, Korhonen T K, Hornick D B, Clegg S. Characterization of the type 3 fimbrial adhesins of Klebsiella strains. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2887–2894. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2887-2894.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sokurenko E V, Courtney H S, Ohman D E, Klemm P, Hasty D L. FimH family of type 1 fimbrial adhesins: functional heterogeneity due to minor sequence variations among fimH genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:748–755. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.748-755.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarkkanen A M, Allen B L, Westerlund B, Holthofer H, Kuusela P, Risteli L, Clegg S, Korhonen T K. Type V collagen as the target for type-3 fimbriae, enterobacterial adherence organelles. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarkkanen A-M, Virkola R, Clegg S, Korhonen T K. Binding of the type 3 fimbriae of Klebsiella pneumoniae to human endothelial and urinary bladder cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1546–1549. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1546-1549.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]