ABSTRACT

Ernest Hemingway is widely regarded as one of the greatest fiction writers of all time. During his life, he demonstrated several signs of psychological suffering with gradual worsening and presentation of cognitive issues over his late years. Some of his symptoms and the course of his disease suggest that he might have suffered from an organic neurodegenerative condition that contributed to his decline, which culminated in his suicide in 1961. In this historical note, we discuss diagnostic hypotheses compatible with Hemingway’s illness, in light of biographical reports.

Keywords: History of Medicine, Neurology, Art, Dementia, Neurodegenerative Diseases

RESUMO

Ernest Hemingway é considerado um dos escritores mais lidos de todos os tempos. Durante sua vida, ele demonstrou diversos sinais de sofrimento psicológico com piora gradual durante seus últimos anos, associado à apresentação de distúrbios cognitivos. Alguns de seus sintomas, assim como o curso da doença, sugerem que ele talvez tenha padecido de uma condição neurodegenerativa orgânica que contribuiu para o seu declínio, culminando em seu suicídio em 1961. Nesta nota histórica, discutimos hipóteses diagnósticas compatíveis com a doença de Hemingway, à luz de relatos biográficos.

Palavras-chave: História da Medicina, Neurologia, Arte, Demência, Doenças Neurodegenerativas

INTRODUCTION

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) (Figure 1) is one of the world's most praised literary writers. His objective prose created masterpieces such as For whom the bell tolls and The old man and the sea1-4.

Figure 1. Ernest Hemingway in the cabin of his boat,Pilar (circa 1950s).

Source: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Licensed under a Public Domain Mark.

Born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Hemingway began writing in journalism and war correspondence. He married four times and had three children.

Hemingway was given the ultimate accolades in literature: the Pulitzer in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in 19545,6. Despite an achieved life, Hemingway presented signs of psychiatric suffering7-12, which culminated in his suicide in 1961 in Ketchum, Idaho. Recent evidence suggests that in his late years he presented neurological signs attributable to dementia3.

At the 60th anniversary of Hemingway’s death, we discuss his neurological condition, emphasizing organic hypotheses based on his biographic reports.

COGNITIVE AND BEHAVIORAL DECLINE

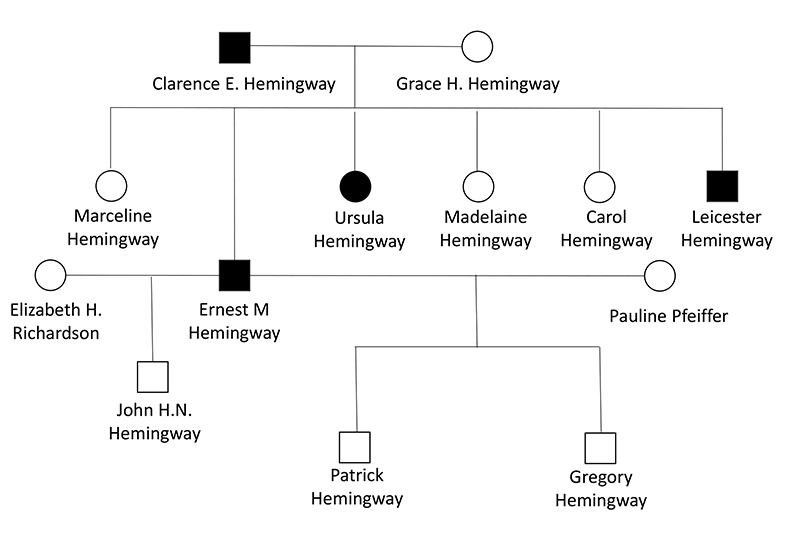

Hemingway presented early signs of a psychiatric condition, possibly bipolar disorder, with documented maniac and depressive episodes, in addition to a significant family history of suicide (Figure 2), although only his father had committed suicide before him1-3,7. Many patients with this condition share outstanding creativity7,8. Patients with bipolar disorder have an increased dementia risk with an incidence of 25.2% in a recent cohort9. Previous papers detailed his psychological ailment10-13.

Figure 2. Pedigree chart for the Hemingway family, showing first-degree relatives to Ernest3,7. Icons in black represent family members who committed suicide. Marriages with Martha Gellhorn and Mary Welsh were omitted, as they did not have children.

The following evidence supports the presence of dementia:

(1) Hemingway’s decline was inexorable, despite electroconvulsive therapy carried in the Mayo Clinic.

(2) In his last years, his cognition sharply declined, impairing his writing.

(3) He presented risk factors for dementia, namely alcoholism, sexual risk behavior, and repeated head trauma3.

The precise onset of Hemingway’s decline is unclear, but it possibly initiated during his fifth decade of life1-3. The disease was marked by a primacy of behavioral symptoms with late cognitive issues, raising several hypotheses (Table 1)1-3.

Table 1. Diagnostic possibilities compatible with Ernest Hemingway’s condition and epidemiology.

| Condition | Arguments in favor | Arguments against |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral variant Frontotemporal Dementia (bvFTD) | Disinhibition. Early onset. Late cognitive disability. | Absence of other features (lack of empathy, obsessive behavior, problems in executive function). |

| Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) | Psychosis. Delusions. Fluctuations. | Absence of Parkinsonism. Lack of well systematized hallucinations. |

| Vascular dementia | Multiple risk factors. Family history of vascular. complications. | No history of strokes. |

| Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) | Multiple concussions. He was a notorious brawler. Predominantly behavioral presentation. | None. |

| Alcohol toxicity/Vitamin deficiency | Heavy alcohol consumption. Other documented complications of alcohol intake (hepatopathy, withdrawal syndrome). | Lack of early amnestic symptomatology. |

| Neurosyphilis | Risk sexual behavior. | Lack of other neurosyphilis hallmarks (motor symptoms, cranial nerve palsy). Lack of a well-documented primary treponemal infection. |

| Huntington’s disease (HD) | Phenotypes with pure behavioral/cognitive symptomatology. | Rare presentation. No members of the Hemingway family presented motor phenomenology compatible with HD. |

Hemingway experienced progressive disinhibition. He would often say inappropriate things during social gatherings and engage in more sexually liberated experiences. This disinhibition can be perceived in the sexual themes present in his last works, A moveable feast and Garden of Eden1-3. The former cruelly depicts his first two wives and his friendship with Scott Fitzgerald, possibly motivated by disinhibition.

His paranoia and delusions increased, with a belief that he was under FBI surveillance. Other sources of paranoia were his hypochondria, fear of impoverishment, and the possibility of arrest for illegal hunting and for “taking liberties with a minor”1-3.

Hemingway would present frequent and unpredictable bursts of aggressiveness, particularly towards his last wife, Mary, who endured significant abuse1-3.

After his first admittance to the Mayo Clinic (1960), Hemingway presented amnestic symptomatology. This would be a burden to his writing, and he would consider finishing A moveable feast impossible. He needed help with the manuscript revision from his wife and editor and his last works would be published only posthumouslly1-3.

DISCUSSING THE POSSIBILITIES

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD)

Hemingway´s clinical features are compatible with the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). FTD presents an earlier onset than other neurodegenerative etiologies, as seen in the writer’s case. Genetics plays a significant role in FTD, and up to 40% of patients present a family history of dementia. However, other bvFTD features, such as lack of empathy, obsessive behavior, and a dysexecutive syndrome were not present14.

Lewy body dementia (LBD)

Hallucinations and psychosis with marked fluctuations are the hallmarks of LBD15. This diagnosis was recently proposed as etiology for Hemingway’s decline3. However, parkinsonism was never described in his case. Moreover, Hemingway’s psychosis presented more delusions than well-substantiated hallucinations, making LBD an unlikely diagnosis1-5.

Vascular dementia

In the Mayo Clinic, Hemingway was diagnosed with severe hypertension, prediabetes, and dyslipidemia. He was under suspicion of hemochromatosis, but a liver biopsy was contraindicated considering his precarious health1-5. Hemingway had a family history of vasculopathy, particularly related to diabetes1-5.

Although Hemingway’s biography reports no strokes, these comorbidities are risk factors for small vessel disease and subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. As clinical presentation is variable and overlapping with other dementia etiologies is common, this is a consistent hypothesis16.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)

Hemingway endured nine major head traumas during his war service, including a mortar blast. In 1954, he survived two plane crashes. He practiced football and boxing from an early age, acted as an amateur bullfighter, and was a reckless driver1-5. CTE is a plausible hypothesis, as this condition often presents with behavioral symptomatology, particularly aggressiveness and mood changes, while cognition is of late affection17.

Alcohol toxicity/Vitamin deficiency

To say Hemingway was a heavy drinker would be an understatement. He spent a significant part of his time in Havana at the bar La Floridita, being served with Papa Dobles (the Hemingway daiquiri) by the bartender2,3. The role of alcohol consumption in dementia is documented, being a risk factor for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. The proposed mechanisms include direct neuronal toxicity and secondary vitamin deficiencies18.

Neurosyphilis

Hemingway had multiple sexual partners, including extramarital relationships. Although he was at risk for syphilis, a more diverse clinical picture would be expected. The absence of motor symptomatology, cranial nerve palsy, and other hallmarks of neurosyphilis, besides the absence of a well-documented primary treponemal infection, make this diagnosis improbable19.

Huntington’s disease (HD)

Certain phenotypes of HD have a predominance or exclusivity of non-motor symptomatology, presenting behavioral and cognitive symptoms, such as the exhibited in Hemingway’s case and family history; motor phenomena may have a late onset or never occur. However, this is a rare presentation and an unlikely hypothesis. Phenotypic variability occurs within the same family, and other members of the Hemingway family would present motor symptomatology20.

In conclusion, Hemingway’s case would remain a challenge in modern days. His personality traits would pose an obstacle for the detection of behavioral symptoms of neurodegeneration.

Although a psychiatric condition is acknowledged, Hemingway’s symptomatology is compatible with organic dementia. In the author’s opinions and in accordance with recent literature3, bvFTD and CTE, possibly associated with a vascular component, might have contributed to his decline.

Remarkably, Hemingway tried to write to his very end despite his cognitive impairment; a display of tenacity worthy of Santiago, the main protagonist of The old man and the sea.

REFERENCES

- Wagner-Martin LW. A historical guide to Ernest Hemingway. 1. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2000. 256 [Google Scholar]

- Hotchner AE. Papa Hemingway: a personal memoir. 1. New York (NY): Random House; 1966. 299 [Google Scholar]

- Farah A. Hemingway’s brain. 1. Columbia (SC): University of South Carolina Press; 2017. 216 [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway E. The old man and the sea: the Hemingway library edition. New York (NY): Scribner; 2020. 155 [Google Scholar]

- The Nobel Prize . Ernest Hemingway -Biographical. NobelPrize.org; [2021 Jul 7]. Internet. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1954/hemingway/facts/ [Google Scholar]

- The Nobel Prize . Ernest Hemingway -Facts. NobelPrize.org; [2021 Jul 7]. Internet. Available from: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1954/hemingway/facts/ [Google Scholar]

- Jamison KR. Touched with fire: manic-depressive illness and the artistic temperament. 1. New York (NY): The Free Press; 1996. 384 [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2. New York (NY): Oxfor University Press; 2007. 1288 [Google Scholar]

- Callahan BL, McLaren-Gradinaru M, Burles F, Laria G. How does dementia begin to manifest in bipolar disorder? A description of prodromal clinical and cognitive changes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(2):737–748. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieguez S. In: Neurological disorders in famous artists -Part 3. Bogousslavsky J, Hennerici MG, Bäzner H, Bassetti C, editors. Karger; 2010. ‘A man can be destroyed but not defeated’: Ernest Hemingway’s near-death experience and declining health; pp. 174–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CD. Ernest Hemingway: a psychological autopsy of a suicide. Psychiatry. 2006;69(4):351–361. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2006.69.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent B. Hemingway: could his suicide have been prevented? CMAJ. 1986;135(8):933–934. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalom ID, Yalom M. Ernest Hemingway. A psychiatric view. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;24(6):485–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750120001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney NT, Spina S, Miller BL. Frontotemporal dementia. Neurol Clin. 2017;35(2):339–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomperts SN. Lewy body dementias: dementia with Lewy Bodies and Parkinson disease dementia. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2016;22(2):435–463. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Duering M, Hachinski V, Joutel A, Pendlebury ST, Schneider JA, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment and dementia: JACC scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(25):3326–3344. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albayram O, Albayram S, Mannix R. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy -a blueprint for the bridge between neurological and psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):424. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01111-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Hasan OSM, Black SE, Shield KD, Schwarzinger M. Alcohol use and dementia: a systematic scoping review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0453-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. N Eng J Med. 2019;381(14):1358–1363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1906228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterloo M, Greef BTA, Bijslma EK, Durr A, Tabrizi SJ, Estevez-Fraga C, et al. Disease onset in Huntington’s disease: when is the conversion? Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2021;8(3):352–360. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]