Abstract

Vibrio cholerae secretes cholera toxin (CT) and the closely related heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) of Escherichia coli, the latter when expressed in V. cholerae. Both toxins are also potent immunoadjuvants. Mutant LT molecules that retain immunoadjuvant properties while possessing markedly diminished enterotoxic activities when expressed by E. coli have been developed. One such mutant LT molecule has the substitution of a glycine residue for arginine-192 [LT(R192G)]. Live attenuated strains of V. cholerae that have been used both as V. cholerae vaccines and as vectors for inducing mucosal and systemic immune responses directed against expressed heterologous antigens have been developed. In order to ascertain whether LT(R192G) can act as an immunoadjuvant when expressed in vivo by V. cholerae, we introduced a plasmid (pCS95) expressing this molecule into three vaccine strains of V. cholerae, Peru2, ETR3, and JRB14; the latter two strains contain genes encoding different heterologous antigens in the chromosome of the vaccine vectors. We found that LT(R192G) was expressed from pCS95 in vitro by both E. coli and V. cholerae strains but that LT(R192G) was detectable in the supernatant fraction of V. cholerae cultures only. In order to assess potential immunoadjuvanticity, groups of germfree mice were inoculated with the three V. cholerae vaccine strains alone and compared to groups inoculated with the V. cholerae vaccine strains supplemented with purified CT as an oral immunoadjuvant or V. cholerae vaccine strains expressing LT(R192G) from pCS95. We found that mice continued to pass stool containing V. cholerae strains with pCS95 for at least 4 days after oral inoculation, the last day evaluated. We found that inoculation with V. cholerae vaccine strains containing pCS95 resulted in anti-LT(R192G) immune responses, confirming in vivo expression. We were unable to detect immune responses directed against the heterologous antigens expressed at low levels in any group of animals, including animals that received purified CT as an immunoadjuvant. We were, however, able to measure increased vibriocidal immune responses against vaccine strains in animals that received V. cholerae vaccine strains expressing LT(R192G) from pCS95 compared to the responses in animals that received V. cholerae vaccine strains alone. These results demonstrate that mutant LT molecules can be expressed in vivo by attenuated vaccine strains of V. cholerae and that such expression can result in an immunoadjuvant effect.

Vibrio cholerae is able to secrete to the cell supernatant cholera toxin (CT) and the closely related heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) of Escherichia coli, the latter when expressed in V. cholerae (17, 25). CT and LT are approximately 80% homologous and are thought to have descended from a common ancestral toxin (24). CT and LT each comprise an enzymatically active A subunit and receptor binding B subunits. Proteolytic cleavage of the A subunit results in a fully active A1 fragment and an enzymatically inactive A2 stalk-like structure covalently joined to A1 via a disulfide bond. A pentamer of B subunits associates with the A subunit through the A2 stalk. The B subunits mediate binding of the holotoxin to carbohydrate molecules on intestinal epithelial cells. After internalization of the toxin and reduction of the A subunit, the A1 fragment mediates ADP ribosylation of the Gsα subunit of adenylate cyclase, leading to an increase in intracellular cyclic AMP levels and secretory diarrhea (2, 12, 15). Full enzymatic activity of LT and CT requires proteolytic cleavage of the A subunit to produce the A1 fragment (10). In E. coli, CT and LT remain within the periplasmic space, and neither is proteolytically cleaved (10, 25). In V. cholerae, proteolytic cleavage is associated with extracellular secretion of CT. It is unclear, however, whether proteolytic cleavage is associated with extracellular secretion of LT in V. cholerae (17). In vivo, proteolytic cleavage of LT may be due to the action of proteases external to E. coli and V. cholerae.

In addition to being enterotoxins, CT and LT are both potent immunoadjuvants (11, 22). The immunoadjuvant properties of CT and LT differ in several aspects, including the induction of different cytokine profiles and the more frequent induction of anaphylaxis-associated immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies with CT than with LT (13, 35). Recently, a number of mutant LT molecules that retain immunoadjuvant properties while possessing markedly diminished enterotoxic activity have been developed (13, 14, 29, 30). Dickinson and Clements have constructed one such mutant LT by using site-directed mutagenesis to create a single amino acid substitution within the disulfide-subtended region of the A subunit separating A1 from A2 (13). This molecule, LT(R192G), has a glycine residue substituted for arginine-192 (13). This single amino acid change has altered the proteolytically sensitive site within this region, rendering the mutant insensitive to trypsin activation. The physical characteristics of this mutant have been examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, its biological activity has been examined with mouse Y-1 adrenal tumor cells and Caco-2 cells, its enzymatic properties have been determined with an in vitro NAD:agmatine ADP ribosyltransferase assay, and its immunogenicity and immunomodulating capabilities have been determined by testing for the retention of immunogenicity and adjuvanticity. Subsequent reports have confirmed the efficacy of LT(R192G) as an effective mucosal adjuvant (8, 18, 26), and LT(R192G) has recently been evaluated in two phase I safety studies (27, 39).

A number of oral, attenuated V. cholerae vaccines that are currently undergoing evaluation for safety and efficacy have been developed (20, 21, 40). The ability to boost the immunological responses induced by such vaccine constructs may be beneficial. In addition, V. cholerae has a number of attributes that make it an attractive candidate for use as a vaccine vector for inducing mucosal immunity against heterologous antigens. V. cholerae is noninvasive but induces long-lasting mucosal and systemic immune responses (19, 31). V. cholerae has been well studied, and attenuated strains of V. cholerae that have been shown to be both safe and immunogenic in humans have already been developed (4, 20, 23, 28, 37, 40). V. cholerae strains that are capable of secreting large heterologous antigens have been developed (32), and such attenuated strains have already been shown to act successfully as vaccine vectors for inducing mucosal immunity and systemic immunity that are protective against the action of heterologous antigens (3, 7, 32, 33). The ability to boost the immune responses induced by V. cholerae vector strains expressing heterologous antigens might increase their effectiveness.

In order to ascertain whether mutant LT expressed in vivo can act as an immunoadjuvant, we expressed LT(R192G) in a number of vaccine strains of V. cholerae. We administered such strains orally to mice and assayed the subsequent systemic and mucosal humoral immune responses induced against V. cholerae antigens as well as against three heterologous antigens, including a fusion protein of the B subunit of CT (CTB) and an immunogenic dodecapeptide-repeating subunit of the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein (SREHP-12) (33), the B subunit of E. coli Shiga toxin 1 (StxB1) (5), and a large fragment of the EaeA protein from enterohemorrhagic E. coli EDL933 (5). The heterologous antigen-expressing vaccine vectors of V. cholerae chosen for this study have been shown previously to produce low levels of the heterologous antigens and to induce poor immunological responses directed against these antigens (1, 5, 33).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains were maintained at −70°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium (34) containing 15% glycerol. Streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and ampicillin (100 μg/ml) were added as appropriate. Cultures were grown at 37°C with aeration. Quantitative culturing was done on LB agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics and confirmed on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose plates.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmid used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| V. cholerae | ||

| C6709 | El Tor, Inaba, wild type; Smr | 3, 38 |

| Peru2 | C6709 ΔattRS1; Smr | 3, 38 |

| ETR3 | Peru2 ΔlacZ lacZ::lppP lacPO→ompA2::SREHP-12::ctxB; Smr | 33 |

| JRB14 | Peru2 ΔirgA irgA::irgP htpGP→stxB ΔlacZ lacZ::htpGP→stxB eaeA; Smr | 5 |

| E. coli JM83 | ara Δlac-proAB rpsL φ80 lacZΔM15; K-12 derivative | 13 |

| Plasmid pCS95 | pUC18-based plasmid containing in-frame LTA and LTB genes with replacement of the AGA sequence encoding arginine-192 of LTA with the glycine-encoding sequence GGA under the control of the lac promoter; identi-cal to previously described pBD95, except for containing the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of human ltxA; Apr | 13; this study |

Smr, streptomycin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance.

Genetic methods.

Isolation of plasmid DNA, restriction enzyme digestion, and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed by standard molecular biological techniques (34).

Construction of pCS95.

Plasmid pCS95 is a pUC-based plasmid carrying the genes for LT from human enterotoxigenic E. coli H10407 with a single point mutation resulting in the substitution of glycine for arginine at amino acid position 192 within the A subunit. Plasmid pCS95 is identical to the previously described plasmid pBD95 (13); however, pCS95 includes the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of ltxA. Plasmids were electroporated into V. cholerae with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) as instructed by the manufacturer and modified for electroporation into V. cholerae as described previously (16). Electroporation conditions were 2,500 V at 25 mF capacitance, producing time contants of 4.8 to 4.9 ms.

In vitro expression of LT(R192G).

In vitro expression of LT(R192G) was analyzed with E. coli JM83 and V. cholerae Peru2, both containing pCS95. Overnight cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min, supernatant fractions were recovered, and pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of lysozyme in sterile water (1 mg/ml). Resuspended pellets were subjected to repeated freezing-thawing at 37 and −70°C and centrifuged, and lysates were recovered. Lysate samples were concentrated approximately 10-fold compared with unprocessed supernatant samples. Supernatant and lysate samples were analyzed in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for LT. Serial dilutions of samples in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) (undiluted to 1:64 diluted) were applied to 96-well microtiter plates previously coated with 1.5 μg of type III ganglioside (Sigma) in 50 mM carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) per well. Samples were analyzed with goat polyclonal anti-LT subunit B (LTB) and anti-LT subunit A (LTA) antibodies, followed by rabbit anti-goat IgG–alkaline phosphatase conjugates. Reactions were developed with 2 mg of p-nitrophenyl phosphate per ml diluted in diethanolamine buffer (pH 9.8). Reactions were stopped with 3 N NaOH, and optical density was read at 405 nm.

Inoculation and colonization of germfree mice.

Immediately upon removal of mice from their germfree shipping carton, nine groups of 6 to 12 germfree female Swiss mice, 3 to 4 weeks old (Taconic Farms, Inc., Germantown, N.Y.), were orally inoculated via gastric intubation with 250-μl inocula containing approximately 109 organisms of V. cholerae strains resuspended in 0.5 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.0). Groups of 6 to 12 mice each received inoculations of Peru2, JRB14, or ETR3; Peru2, JRB14, or ETR3 supplemented with 5 μg of purified CT (List Biological Laboratories, Inc., Campbell, Calif.) as an immunoadjuvant; or Peru2(pCS95), JRB14(pCS95), or ETR3(pCS95). Two mice were treated identically but remained unvaccinated as controls. Mice were subsequently housed in non-germfree conditions (6). All mice received a second oral inoculation at day 14. To ascertain the presence of pCS95, fresh stool samples were collected immediately upon passage from mice until day 4 after oral inoculation, resuspended in 500 μl of LB broth medium, vortexed, and allowed to settle. One hundred-microliter aliquots were plated on LB agar medium containing ampicillin and streptomycin, and colonies were subsequently confirmed as V. cholerae on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose medium. Plasmid preparations from randomly selected, ampicillin-resistant colonies from stool samples collected 72 h after oral inoculation were examined to confirm the presence of pCS95.

Immunological sampling.

Mice were sacrificed on day 28, at which time blood was collected via intracardiac puncture. Blood was allowed to clot, and serum was separated by centrifugation. Bile (3 to 6 μl) was collected via hepatic dissection and subsequent aspiration of the gallbladder (33). Fresh stool pellets were collected for immunological evaluation and stored at −20°C until processed. Each pellet was then placed in 1 ml of a 3:1 mixture of PBS–0.1 M EDTA containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (type II-S; Sigma) at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml and vortexed until it was broken (33). The mixture was centrifuged twice. Twenty microliters of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) was added to each 1 ml of final recovered supernatant (41). Stool, bile, and serum samples were divided into aliquots and stored at −70°C for subsequent analysis.

Measurement of systemic and mucosal anti-CTB, anti–SREHP-12, anti-StxB, and anti-EaeA antibody responses.

To detect anti-CTB antibody responses, microtiter plates were coated with 100 ng of type III gangliosides (Sigma) in 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) per well. Following overnight incubation at room temperature and three washes in PBS-T, 100 ng of CTB (List) in carbonate buffer was applied to each well, and the plates were again incubated overnight at room temperature. After being washed in PBS-T, the plates were blocked with PBS–1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma). To detect anti–SREHP-12 antibodies, plates were coated with E. histolytica HM1:IMSS trophozoites in PBS (104 per well) overnight at 4°C and then blocked with PBS-BSA as previously described (41, 42). To detect anti-StxB antibodies, plates were coated with 10 μg of ceramide trihexoside (Matreya, Inc., Pleasant Gap, Pa.) per ml in methanol. After evaporation of the methanol at 37°C for 2 h, 100 ng of StxB in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) per well was added (5). Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature and then blocked with PBS-BSA. To detect anti-EaeA antibodies, plates were coated with 100 ng of a purified histidine-tagged intimin protein (RIHisEae) containing 900 of the 935 carboxy-terminal amino acids of EaeA from E. coli O157:H7 (strain 86-24) (5) in carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) per well. After overnight incubation at room temperature, the plates were blocked with PBS-BSA.

To detect specific anti-CTB, anti–SREHP-12, anti-StxB, and anti-EaeA IgG and IgA antibodies in sera, 100-μl duplicate samples of 1:1,000 (IgG) and 1:100 (IgA) dilutions of sera in PBS-T were placed in wells of microtiter plates previously coated with ganglioside-CTB, E. histolytica trophozoites, ceramide trihexoside-StxB, and RIHisEae, respectively, as described above. Plates were incubated at room temperature overnight and washed in PBS-T. A 1:2,000 dilution in PBS-T of goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to biotin or goat anti-mouse IgA conjugated to biotin (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was applied to each well, and the plates were again incubated overnight at room temperature. After the plates were washed in PBS-T, a 1:4,000 dilution of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Zymed Laboratories, Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After being washed in PBS-T, the plates were developed with a solution containing 1 mg of 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (Sigma)/ml and 0.1% H2O2 (Sigma), and the optical density at 405 nm was determined kinetically with a Vmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.). Plates were read for 5 min at 19-s intervals, and the maximum slope for an optical density change of 0.2 U was reported as milli-optical density units per minute (32).

To detect specific IgA antibody responses in stool and bile, measurements of total stool and bile IgA were first taken. Duplicate serial twofold dilutions of stool (1:50 to 1:6,400) and bile (1:800 to 1:3,200) samples in PBS-T were added to wells previously coated with 100 ng of rat monoclonal anti-mouse IgA antibody R5-140 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and previously blocked with PBS-BSA. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and then washed with PBS-T. A 1:2,000 goat anti-mouse IgA–horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) in PBS-T was added to each well. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed with PBS-T and developed for horseradish peroxidase activity as described above. Comparisons were made to a mouse IgA standard (Kappa TEPC 15; Sigma).

To detect specific anti-CTB, anti–SREHP-12, anti-StxB, and anti-EaeA IgA antibodies in stool and bile, single (bile) or duplicate (stool) samples of 100 μl of PBS-T containing 750 ng of total IgA (stool) or 125 ng of total IgA (bile) were added to wells previously coated with ganglioside-CTB, E. histolytica trophozoites, ceramide trihexoside-StxB, and RIHisEae, respectively. Plates were incubated at room temperature overnight. After the plates were washed with PBS-T, a 1:2,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse IgA–biotin conjugate (Kirkegaard & Perry) in PBS-T was added. After overnight incubation at room temperature, the plates were developed for horseradish peroxidase activity, and the optical density at 405 nm was determined kinetically.

Detection of vibriocidal antibodies.

Serum vibriocidal antibody titers were measured by a microassay as follows. The endogenous complement activity of test sera was inactivated by heating the sera to 56°C for 1 h. Fifty-microliter aliquots of serial twofold dilutions of test sera in PBS (1:25 to 1:25,600) were placed in wells of 96-well tissue culture plates; 50 μl of 108 CFU of V. cholerae Peru2 per ml in PBS with 22% guinea pig complement (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added to the serum dilutions. The mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. One hundred-fifty microliters of brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for approximately 2 h at 37°C. The optical density at 600 nm was then measured; the vibriocidal titer was calculated as the dilution of serum causing a 50% reduction in optical density compared with that in wells containing no serum (3, 33).

Statistics and graphs.

Statistical analysis for the comparison of geometric means was performed for normally distributed data with the independent-sample Student t test or with the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data by use of SPSS for Windows 7.0. Data were plotted with Microsoft Excel 7.0a and CA-Cricket Graph Software (Computer Associates, Garden City, N.Y.).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In vitro expression of LT(R192G) from pCS95.

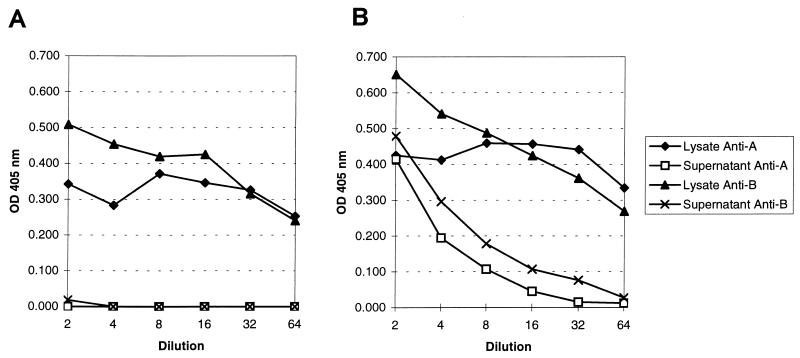

Whole-cell lysates and supernatant fractions of JM83(pCS95) and Peru2(pCS95) were assayed for LT(R192G) by a ganglioside binding ELISA with antibodies specific for LTA and LTB, respectively. LT(R192G) was found in both whole-cell lysates and supernatant fractions of the V. cholerae strain but was found only in the lysates and not in the supernatant fractions of the E. coli strain (Fig. 1). Previous work has shown that native LT is secreted extracellularly by V. cholerae but remains cell associated in E. coli (10, 17, 25). Our results suggest, therefore, that LT(R192G) is expressed in E. coli and V. cholerae strains in fashions similar to those of native LT.

FIG. 1.

Anti-LTA (Anti-A) and anti-LTB (Anti-B) ELISA results for whole-cell lysates and supernatant fractions of E. coli JM83(pCS95) (A) and V. cholerae Peru2(pCS95) (B) evaluated for in vitro production of LT(R192G). OD 405 nm, optical density at 405 nm. Results are reported for 1:2 to 1:64 dilutions. Lysates are concentrated 10-fold compared with supernatant fractions.

Intestinal colonization and retention of plasmid pCS95 in mice following oral inoculation of vaccine constructs.

Prior to oral inoculations of mice, overnight cultures of attenuated strains of V. cholerae containing pCS95 were grown in medium containing antibiotics selective for the plasmid. Selective pressure was not maintained in vivo. Quantitative cultures of the vaccine inocula of Peru2(pCS95), ETR3(pCS95), and JRB14(pCS95) disclosed that approximately 109 V. cholerae organisms/inoculum contained pCS95 at the time of oral administration.

Previous studies have shown that germfree mice orally inoculated on days 0 and 14 with Peru2-based attenuated strains of V. cholerae pass these organisms in the stool for 7 to 14 days after the first inoculation and for approximately 2 days after the second inoculation (33) and that plasmids contained in these strains are retained in vivo for 3 to 5 days after the first inoculation and for 1 day after the second inoculation, even when no specific selection pressure for the plasmid exists in vivo. In the current study, 92% of mice inoculated with the V. cholerae vaccine strains Peru2(pCS95), ETR3(pCS95), and JRB14(pCS95) continued to pass V. cholerae organisms containing pCS95 in the stool 2 days after the first inoculation, and 50% continued to pass V. cholerae organisms containing pCS95 in the stool 4 days after the first inoculation. These numbers match the previously described results (33). Plasmid preparations of ampicillin-resistant colonies isolated from stool freshly passed 72 h after oral inoculation confirmed the ongoing intestinal presence of V. cholerae organisms containing pCS95.

In vivo expression of LT(R192G) and measurement of antibodies directed against LT(R192G) or CTB.

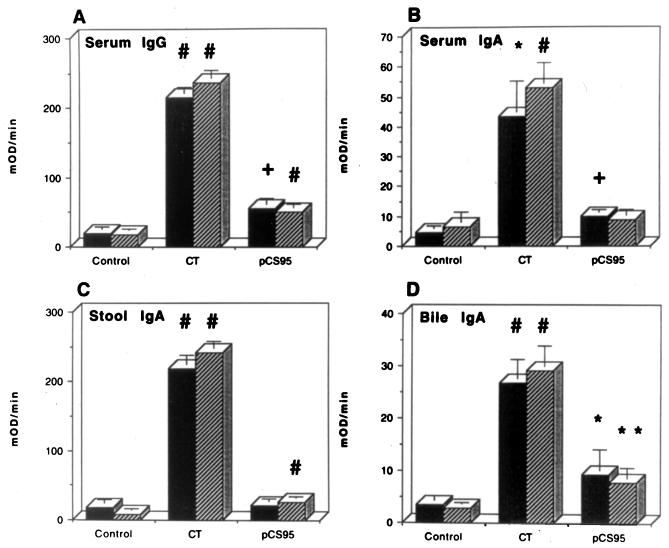

Immunological responses to CT and LT are predominantly directed against the B subunit of each holotoxin, and immunological responses to LTB and CTB are cross-reactive in immunological assays (9, 36). In order to ascertain whether LT(R192G) is expressed in vivo by V. cholerae strains containing pCS95, the immunological responses to CTB (and, by inference, LTB) in serum, stool, and bile samples of mice inoculated with Peru2(pCS95) were compared to those of mice receiving Peru2 alone. Anti-CTB and -LTB responses were also measured in mice that received Peru2 supplemented with CT as an immunoadjuvant and in mice that were vaccinated with V. cholerae vaccine strains producing the heterologous antigen CTB–SREHP-12. As shown in Fig. 2, animals that were exposed to LT(R192G) from vaccine strain Peru2(pCS95) had significant increases in serum anti-CTB (LTB) IgG (P, <0.01) and IgA (P, <0.01) levels and significant increases in anti-CTB (LTB) IgA levels in bile (P, <0.05), confirming the in vivo expression of LT(R192G).

FIG. 2.

Anti-CTB (LTB) ELISA results on day 28 for mice inoculated with Peru2 or ETR3 (Control), Peru2 or ETR3 supplemented with 5 μg of CT (CT), or Peru2(pCS95) or ETR3(pCS95) (pCS95). Solid columns represent the response in animals that received Peru2-based vaccines; hatched columns represent the response in animals that received ETR3-based vaccines. The geometric mean plus the standard error of the mean is reported for each group. mOD/min, millioptical density units per minute. P values for test animals versus control animals were <0.001 (#), <0.01 (+), <0.05 (∗), and <0.02 (∗∗).

The most prominent anti-CTB response in serum was observed in mice that received vaccine strain ETR3 producing CTB–SREHP-12 and supplemented with CT as an immunoadjuvant. Serum anti-CTB IgG (P, <0.001) and IgA (P, <0.001) responses were both significantly elevated. Animals that received Peru2 supplemented with CT also had prominent serum anti-CTB IgG (P, <0.001) and IgA (P, <0.05) responses, and animals that received ETR3(pCS95) had increased serum anti-CTB (LTB) IgG (P, <0.001) and IgA responses. The most prominent anti-CTB responses in stool and bile were detected in animals that received ETR3 supplemented with CT. Anti-CTB IgA responses in stool (P, <0.001) and bile (P, <0.001) were both significantly elevated. Mice that received Peru2 supplemented with CT also had elevated anti-CTB IgA levels in stool (P, <0.001) and bile (P, <0.001), and mice that received ETR3(pCS95) had increased anti-CTB (LTB) responses in both stool (P, <0.001) and bile (P, <0.02).

These results demonstrate that LT(R192G) is expressed sufficiently in vivo from pCS95 to induce both systemic and mucosal anti-LTB immune responses, even in animals that receive Peru2(pCS95) expressing LT(R192G) but not CT or CTB molecules. These results also demonstrate that study mice that receive CT as an immunoadjuvant are able to mount mucosal and systemic immune responses that react with CTB and that these responses are most prominent in groups of animals that receive not only CT but also V. cholerae vaccine strains producing CTB–SREHP-12.

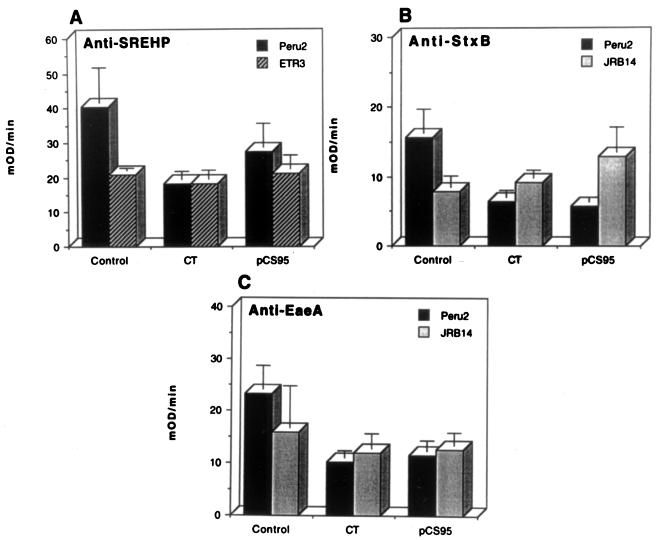

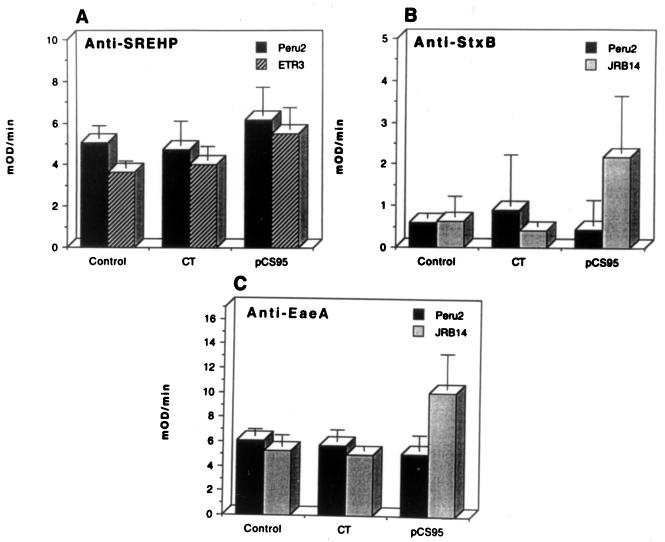

Measurement of immune responses to SREHP-12, StxB, and EaeA expressed by the vaccine vectors.

The attenuated strains of V. cholerae used in this study express their heterologous antigens at very low levels from stable chromosomal modifications (5, 33). Serum IgG and IgA responses directed against the heterologous antigens were not prominent and were not boosted by LT(R192G) expressed from pCS95 or by supplemental CT in this study (data not shown). Specifically, the levels of antiamebic serum IgG and IgA antibodies were not increased in animals that received ETR3 compared with animals inoculated with Peru2, nor were antiamebic serum IgG and IgA immune responses boosted in animals that received ETR3(pCS95) or ETR3 supplemented with CT compared with animals that received ETR3 alone. In comparison to antibody levels in animals that received Peru2 alone, animals that received JRB14 did have increased serum IgG antibody responses directed against StxB and EaeA, but these differences did not reach statistical significance, nor were serum IgG and IgA responses against these antigens boosted in animals that received JRB14(pCS95) or JRB14 supplemented with CT. Analysis of stool IgA antibody responses to the heterologous antigens also did not disclose any significant differences among the various groups of animals (Fig. 3). Analysis of bile IgA antibody responses did, however, disclose that the most prominent anti-StxB and anti-EaeA responses were detected in animals that received JRB14(pCS95); these differences, however, did not achieve statistical significance (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Anti-heterologous antigen ELISA responses in day-28 stool samples from mice that received V. cholerae strains alone (Control), V. cholerae strains supplemented with 5 μg of CT (CT), or V. cholerae strains containing pCS95 (pCS95). The geometric mean plus standard error of the mean is reported for each group. mOD/min, millioptical density units per minute. None of the immune responses to the heterologous antigens was significantly different from that of controls.

FIG. 4.

Anti-heterologous antigen ELISA responses in day-28 bile samples from mice that received V. cholerae strains alone (Control), V. cholerae strains supplemented with 5 μg of CT (CT), or V. cholerae strains containing pCS95 (pCS95). The geometric mean plus standard error of the mean is reported for each group. mOD/min, millioptical density units per minute. None of the immune responses to the heterologous antigens was significantly different from that of controls.

The heterologous antigen-producing vaccine strains V. cholerae ETR3 and JRB14 were chosen for this study for a number of reasons. These strains have already been shown to have low-level, but stable, expression of the heterologous antigens from chromosomal modifications, and these antigens have already been shown to localize to various cellular compartments: StxB localizes to the periplasmic space and EaeA localizes to the outer membrane in JRB14, while CTB–SREHP-12 is secreted into the supernatant in ETR3 (5, 33). ETR3 and JRB14 have been shown to induce poor immune responses to the expressed heterologous antigens in study animals, most likely due to the low levels of expression of the heterologous antigens from genes inserted in the chromosome (5, 33). Studies with V. cholerae strains expressing CTB–SREHP-12 had demonstrated previously that although low-level antiamebic immune responses could be induced after two oral inoculations of mice with ETR3, the most prominent antiamebic immune responses were induced when CTB–SREHP-12 was expressed from a multiple-copy-number plasmid in a vector strain of V. cholerae. In the current study, we were unable to demonstrate the previously shown low-level antiamebic immune responses induced by ETR3, perhaps because of interanimal variability. The inability of the well-characterized oral immunoadjuvant CT to boost the anti–SREHP-12, anti-StxB, and anti-EaeA immune responses in this study may also have been due primarily to the low levels of in vivo expression of the heterologous antigens. Interestingly, the in vivo coexpression of heterologous antigens and LT(R192G) was associated with the most prominent immune responses in bile, even more so than the administration of vector strains of V. cholerae with CT, suggesting that continual in vivo expression may be more successful at boosting mucosal immune responses directed against coexpressed heterologous antigens than oral administration of purified immunoadjuvants, such as CT.

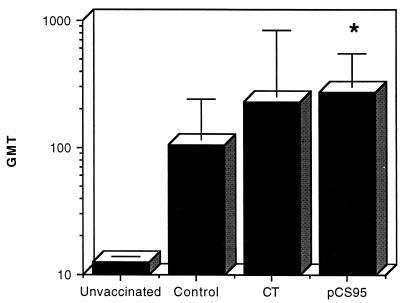

Measurement of serum vibriocidal antibodies.

Vibriocidal antibodies were measured in day-28 serum samples (Fig. 5). Compared with the responses in unvaccinated germfree mice that had otherwise been treated in the same manner as study animals, all groups of animals inoculated with V. cholerae vaccine strains developed vibriocidal antibody responses. In comparison to the vibriocidal antibody responses in animals that received attenuated V. cholerae strains not supplemented with an immunoadjuvant, the highest mean vibriocidal antibody response was seen in animals that received attenuated V. cholerae strains expressing LT(R192G) from pCS95 (P, <0.05). This response was even higher than that measured in animals that received V. cholerae strains supplemented with the known immunoadjuvant CT.

FIG. 5.

Geometric mean titers (GMT) of vibriocidal antibody responses on day 28 following day-0 and day-14 oral inoculations of mice with V. cholerae vaccine strains (data combined for Peru2, ETR3, and JRB14). Animals either remained uninoculated (unvaccinated) or received V. cholerae vaccine strains alone (Control), V. cholerae vaccine strains supplemented with 5 μg of CT (CT), or V. cholerae vaccine strains expressing LT(R192G) from pCS95 (pCS95). Error bars depict standard errors of the mean for each group. The asterisk indicates a P value of <0.05 for test animals versus control animals that received V. cholerae strains alone.

In summary, this study demonstrated that LT(R192G) can be expressed in vitro and in vivo by attenuated vaccine strains of V. cholerae containing plasmid pCS95 and that such in vivo expression is sufficient to yield immune responses to LTB. In vivo expression of this mutant LT molecule increased serum antibody responses to V. cholerae vaccine and vector strains and might have boosted mucosal immune responses against two coexpressed heterologous antigens in bile. LT(R192G) that is expressed in vivo by attenuated strains of V. cholerae can therefore act as an immunoadjuvant, and such immunoadjuvanticity could result in more effective immunization strategies. Further experiments to analyze more fully both the expression and the immunoadjuvanticity of mutant LT molecules in V. cholerae vaccine and vector strains are currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants K08AI01332 (to E.T.R.), K08AI01386 (to J.R.B.), AI28835 (to J.D.C.), and AI40725 (to S.B.C.), all from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We are extremely grateful to Marian R. Wachtel, Marian L. McKee, and Alison O’Brien for RIHisEae; David W. Acheson for StxB; Samuel L. Stanley, Jr., Tonghai Zhang, and Lynne Foster for E. histolytica HM1:IMSS trophozoite-coated plates and CTB–SREHP-12; and John Mekalanos for V. cholerae Peru2.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acheson D W, Levine M M, Kaper J B, Keusch G T. Protective immunity to Shiga-like toxin I following oral immunization with Shiga-like toxin I B-subunit-producing Vibrio cholerae CVD 103-HgR. Infect Immun. 1996;64:355–357. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.355-357.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angstrom J, Teneberg S, Karlsson K A. Delineation and comparison of ganglioside-binding epitopes for the toxins of Vibrio cholerae, Escherichia coli, and Clostridium tetani: evidence for overlapping epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11859–11863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butterton J R, Beattie D T, Gardel C L, Carroll P A, Hyman T, Killeen K P, Mekalanos J J, Calderwood S B. Heterologous antigen expression in Vibrio cholerae vector strains. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2689–2696. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2689-2696.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butterton J R, Boyko S A, Calderwood S B. Use of the Vibrio cholerae irgA gene as a locus for insertion and expression of heterologous antigens in cholera vaccine strains. Vaccine. 1993;11:1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butterton J R, Ryan E T, Acheson D W, Calderwood S B. Coexpression of the B subunit of Shiga toxin 1 and EaeA from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in Vibrio cholerae vaccine strains. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2127–2135. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2127-2135.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butterton J R, Ryan E T, Shahin R A, Calderwood S B. Development of a germfree mouse model of Vibrio cholerae infection. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4373–4377. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4373-4377.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen I, Finn T M, Yanqing L, Guoming Q, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. A recombinant live attenuated strain of Vibrio cholerae induces immunity against tetanus toxin and Bordetella pertussis tracheal colonization factor. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1648–1653. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1648-1653.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong C, Friberg M, Clements J D. LT(R192G), a non-toxic mutant of the heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli, elicits enhanced humoral and cellular immune responses associated with protection against lethal oral challenge with Salmonella spp. Vaccine. 1998;16:732–740. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clements J D, Finkelstein R A. Immunological cross-reactivity between a heat-labile enterotoxin(s) of Escherichia coli and subunits of Vibrio cholerae enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1978;21:1036–1039. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.3.1036-1039.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements J D, Finkelstein R A. Isolation and characterization of homogeneous heat-labile enterotoxins with high specific activity from Escherichia coli cultures. Infect Immun. 1979;24:760–769. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.3.760-769.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clements J D, Hartzog N M, Lyon F L. Adjuvant activity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and effect on the induction of oral tolerance in mice to unrelated protein antigens. Vaccine. 1988;6:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(88)90223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clements J D, Yancey R J, Finkelstein R A. Properties of homogeneous heat-labile enterotoxin from Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1980;29:91–97. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.1.91-97.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickinson B L, Clements J D. Dissociation of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin adjuvanticity from ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1617–1623. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1617-1623.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiTommaso A, Saletti G, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Dougan G, Abrignani S, Douce G, De M M. Induction of antigen-specific antibodies in vaginal secretions by using a nontoxic mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin as a mucosal adjuvant. Infect Immun. 1996;64:974–979. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.974-979.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill D M, King C A. The mechanism of action of cholera toxin in pigeon erythrocyte lysates. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:6424–6432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg M B, Boyko S A, Calderwood S B. Positive transcriptional regulation of an iron-regulated virulence gene in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1125–1129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirst T R, Sanchez J, Kaper J B, Hardy S J, Holmgren J. Mechanism of toxin secretion by Vibrio cholerae investigated in strains harboring plasmids that encode heat-labile enterotoxins of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7752–7756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz J M, Lu X, Galphin J C, Clements J D. Heat labile enterotoxin from Escherichia coli as an adjuvant for oral influenza vaccination. In: Brown L E, Hampson A W, Webster R G, editors. Options for the control of influenza III. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.; 1996. pp. 292–297. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine M M, Black R E, Clements M L, Cisneros L, Nalin D R, Young C R. Duration of infection-derived immunity to cholera. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:818–820. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine M M, Kaper J B, Herrington D, Ketley J, Losonsky G, Tacket C O, Tall B, Cryz S. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of recombinant live oral cholera vaccines, CVD 103 and CVD 103-HgR. Lancet. 1988;ii:467–470. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y Q, Qi G M, Wang S X, Yu Y M, Duan G C, Zhang L J, Gao S Y. A natural vaccine candidate strain against cholera. Biomed Environ Sci. 1995;8:350–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lycke N, Holmgren J. Strong adjuvant properties of cholera toxin on gut mucosal immune responses to orally presented antigens. Immunology. 1986;59:301–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mekalanos J J, Swartz D J, Pearson G D, Harford N, Groyne F, de Wilde M. Cholera toxin genes: nucleotide sequence, deletion analysis and vaccine development. Nature. 1983;306:551–557. doi: 10.1038/306551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moseley S L, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence homology between the heat-labile enterotoxin gene of Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae deoxyribonucleic acid. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:444–446. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.444-446.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neill R J, Ivins B E, Holmes R K. Synthesis and secretion of the plasmid-coded heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli in Vibrio cholerae. Science. 1983;221:289–291. doi: 10.1126/science.6857285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neal C M, Clements J D, Estes M K, Conner M E. Rotavirus 2/6 viruslike particles administered intranasally with cholera toxin, Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin (LT), and LT-R192G induce protection from rotavirus challenge. J Virol. 1998;72:3390–3393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3390-3393.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oplinger M L, Baqar S, Trofa A F, Clements J D, Gibbs P, Pazzaglia G, Bourgeois A L, Scott D A. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1997. Safety and immunogenicity in volunteers of a new candidate oral mucosal adjuvant, LT(R192G), abstr. G-10; p. 193. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson G D, Woods A, Chiang S L, Mekalanos J J. CTX genetic element encodes a site-specific recombination system and an intestinal colonization factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3750–3754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pizza M, Domenighini M, Hol W, Giannelli V, Fontana M R, Giuliani M M, Magagnoli C, Peppoloni S, Manetti R, Rappuoli R. Probing the structure-activity relationship of Escherichia coli LT-A by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pizza M, Fontana M R, Giuliani M M, Domenighini M, Magagnoli C, Giannelli V, Nucci D, Hol W, Manetti R, Rappuoli R. A genetically detoxified derivative of heat-labile Escherichia coli enterotoxin induces neutralizing antibodies against the A subunit. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2147–2153. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quiding M, Nordstrom I, Kilander A, Andersson G, Hanson L A, Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Intestinal immune responses in humans. Oral cholera vaccination induces strong intestinal antibody responses and interferon-gamma production and evokes local immunological memory. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:143–148. doi: 10.1172/JCI115270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan E T, Butterton J R, Smith R N, Carroll P A, Crean T I, Calderwood S B. Protective immunity against Clostridium difficile toxin A induced by oral immunization with a live, attenuated Vibrio cholerae vector strain. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2941–2949. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2941-2949.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan E T, Butterton J R, Zhang T, Baker M A, Stanley S L J, Calderwood S B. Oral immunization with attenuated vaccine strains of Vibrio cholerae expressing a dodecapeptide repeat of the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein fused to the cholera toxin B subunit induces systemic and mucosal antiamebic and anti-V. cholerae antibody responses in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3118–3125. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3118-3125.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snider D P, Marshall J S, Perdue M H, Liang H. Production of IgE antibody and allergic sensitization of intestinal and peripheral tissues after oral immunization with protein Ag and cholera toxin. J Immunol. 1994;153:647–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svennerholm A M, Holmgren J, Black R, Levine M, Merson M. Serologic differentiation between antitoxin responses to infection with Vibrio cholerae and enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:514–522. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tacket C O, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Comstock L, Michalski J, Edelman R, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Initial clinical studies of CVD112 Vibrio cholerae O139 live oral vaccine: safety and efficacy against experimental challenge. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:883–886. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor D N, Killeen K P, Hack D C, Kenner J R, Coster T S, Beattie D T, Ezzell J, Hyman T, Trofa A, Sjogren M H. Development of a live, oral, attenuated vaccine against El Tor cholera. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1518–1523. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tribble D R, Baqar S, Oplinger M L, Bourgeois A L, Clements J D, Pazzaglia G, Pace J, Walker R I, Gibbs P, Scott D A. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1997. Safety and enhanced immunogenicity in volunteers of an oral, inactivated whole-cell Campylobacter vaccine coadministered with a modified Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin adjuvant, LT(R192G), abstr. LB-29; p. 14. Program Addendum. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. Emergence of a new cholera pandemic: molecular analysis of virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae O139 and development of a live vaccine prototype. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:278–283. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang T, Li E, Stanley S L., Jr Oral immunization with the dodecapeptide repeat of the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein (SREHP) fused to the cholera toxin B subunit induces a mucosal and systemic anti-SREHP antibody response. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1349–1355. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1349-1355.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang T, Stanley S L., Jr Oral immunization with an attenuated vaccine strain of Salmonella typhimurium expressing the serine-rich Entamoeba histolytica protein induces an antiamebic immune response and protects gerbils from amebic liver abscess. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1526–1531. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1526-1531.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]