Abstract

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are often associated with elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and highly dysregulated gut microbiota. In this study, we synthesized a polymer of hyaluronic acid–poly(propylene sulfide) (HA-PPS) and developed ROS-scavenging nanoparticles (HPN) that could effectively scavenge ROS. To achieve colon tissue targeting effects, the HPN nanoparticles were conjugated to the surface of modified probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN). To enhance the bacteriotherapy of EcN, we encapsulated EcN cells with a poly-norepinephrine (NE) layer that can protect EcN against environmental assaults to improve the viability of EcN in oral delivery and prolong the retention time of EcN in the intestine due to its strong mucoadhesive capability. In the dextran sulfate sodium–induced mouse colitis models, HPN-NE-EcN showed substantially enhanced prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota were increased after treatment with HPN-NE-EcN, contributing to the alleviation of IBDs.

The ROS scavenging and gut microbiota regulation with mucoadhesive probiotic backpacks enhance the bacteriotherapy for IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are by-products of aerobic metabolism, are crucial molecules in physiological processes (1, 2). However, their overproduction will cause oxidative stress, which will amplify inflammatory responses and exacerbate inflammatory disorders, especially in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in intestinal mucosal layer damage and pathogen invasion, subsequentially stimulating immune responses, and ultimately leading to the development of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) (3–5). Excessive ROS-induced oxidative stress in the intestine is thought to be a major factor in the pathogenesis and progression of IBDs. Oxidative stress is caused by the imbalance in the generation of reactive species and the host’s antioxidant defense capability (6, 7). Excessive ROS can cause intestinal endothelial cell damage through inducing lipid peroxidation and DNA mutation, impairing protein functions, altering epithelial permeability, and disrupting intestinal epithelial barriers, eventually leading to the initiation or deterioration of IBDs (8, 9). Furthermore, excessive ROS can also cause dysregulated proinflammatory reactive species–sensitive pathways in immune cells (10, 11) and induce dysbiosis of the gut microbiota (12, 13). Antioxidants are known to scavenge ROS in the intestines and are helpful for the treatment of IBDs (14–16). However, because of their rapid clearance, nonspecific drug biodistribution after systemic administration, and relatively inefficient ROS-scavenging ability, antioxidants demonstrate inconsistent efficacy for treating inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, undesirable drug distribution profiles of antioxidants in normal tissues can cause a variety of adverse effects (17–19).

In addition to excessive ROS in the intestine, IBD is associated with dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in the colonic microenvironment (20–22). In a healthy individual, microbiota provides the host with short-chain fatty acids and essential vitamins while also protecting them from pathogen colonization and invasion. In contrast, a disordered microbiota induces a chronic inflammatory state, increases toxic production, and disrupts the host’s metabolism (23–25). In our previous studies, we found that orally administered probiotics can colonize colon tissues and aid in the restoration of the normal gut microbiome to treat GI tract–related diseases (26, 27). Unfortunately, these probiotics are highly sensitive to the harsh environments in the GI tract, which limits their viability and retention time in the intestine, leading to decreased therapeutic efficacy (28, 29).

In this study, we established a platform that can selectively and sustainably scavenge ROS in inflamed colon tissues while also improving probiotic delivery for gut microbiota homeostasis modulation. This platform could help to restore a normal gut microenvironment and address the fundamental issues for effective IBD therapy. We initially selected poly(propylene sulfide) (PPS), a hydrophobic polymer, to scavenge ROS (30). The sulfur atoms of PPS are easily oxidized by ROS to form a sulfoxide that will be further oxidized to produce a sulfone (31). This inherent PPS reactivity with ROS provides PPS antioxidant properties that can serve as a highly efficient tool for scavenging ROS (32). Moreover, the PPS polymer contains multiple ROS-reacting sites capable of scavenging multiple ROS molecules compared to small antioxidant molecules. However, the clinical application of PPS is limited because it is highly hydrophobic, which makes it difficult for in vivo applications (33). In this study, we synthesized a hyaluronic acid (HA)–PPS conjugate and self-assembled the HA-PPS nanoparticle (HPN) based on the amphiphilic properties that exist when HA and PPS are combined (Fig. 1A). HA was used to modify PPS and construct HPN because it can improve IBD treatment by modulating immune responses, such as regulation of macrophages, and serving as a potent anti-inflammatory agent (34). In addition, HA, which is often present in synovial fluids and the extracellular matrix, is biocompatible and biodegradable. HA has been widely used in biomedical applications with a great in vivo biosafety profile. The newly generated HPN exhibited improved hydrophilicity and demonstrated cytoprotective effects while maintaining the robust ROS-scavenging activity of PPS. Moreover, it was shown that once the ROS were consumed and the sulfur atoms were oxidized to sulfone, the HPN would self-degrade because of the transformation of PPS from a hydrophobic to a hydrophilic state (fig. S1) (35). This transformation enhances the safety of HPN and opens the door for potential clinical applications.

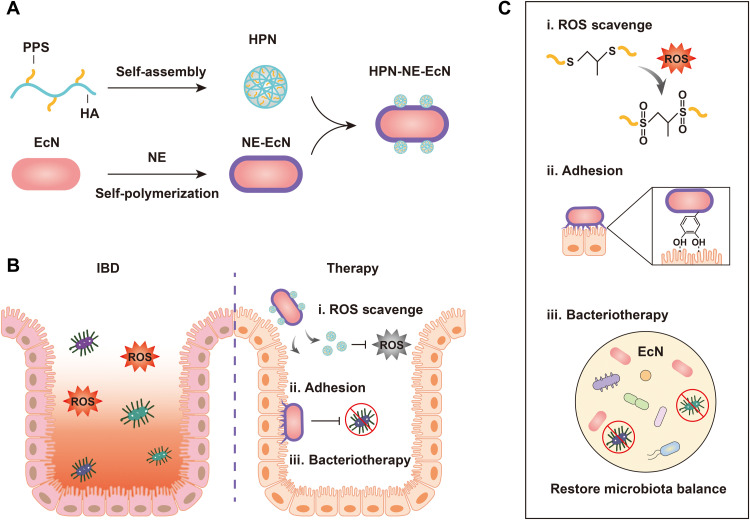

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the preparation of HPN-NE-EcN and its mechanism for IBD treatment.

(A) Preparation of HPN by self-assembly of HA-PPS molecule, encapsulation of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) with the norepinephrine (NE) layer, and conjugation of HPN to the surface of EcN. (B and C) The prepared HPN-NE-EcN exerts ROS-scavenging activity by oxidizing sulfur atoms in PPS to form sulfoxides and then further oxidizing to form sulfones (i). Furthermore, the NE layer, which mimics mussel adhesive foot proteins, endows EcN with a strong mucoadhesive ability and extends the retention time of EcN in the intestine (ii), allowing for enhanced bacteriotherapy through restoring the gut microbiome homeostasis (iii).

To improve the oral probiotic delivery to the colon for enhanced bacteriotherapy, we encapsulated probiotics with norepinephrine (NE), which could be auto-oxidized to form a poly-NE film on the probiotic surface to protect it from external environmental assaults (36, 37). Furthermore, the catecholamine group of NE, which was found rich in mussel adhesive foot proteins and responsible for the strong adhesive properties in mussels (38, 39), endowed probiotics with robust mucosa adhesive property and extended retention time of probiotics in the intestine without influencing probiotics’ growth and proliferation for enhanced therapeutic efficacy (Fig. 1B). On the basis of the colon tissue colonization property of probiotics, we further conjugated HPN to the surface of probiotics to effectively deliver the HPN to inflammatory colon tissues for normalizing ROS levels and minimizing off-target side effects. This platform not only has the ability to prolong the retention time of probiotics in the intestine for enhanced bacteriotherapy, but it can also specifically deliver and slow-release HPN in the intestine for improved ROS-scavenging capabilities (Fig. 1C). Last, this platform exhibited the enhanced prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy against dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)–induced mouse colitis.

RESULTS

Preparation and characterization of HPN as the ROS scavenger

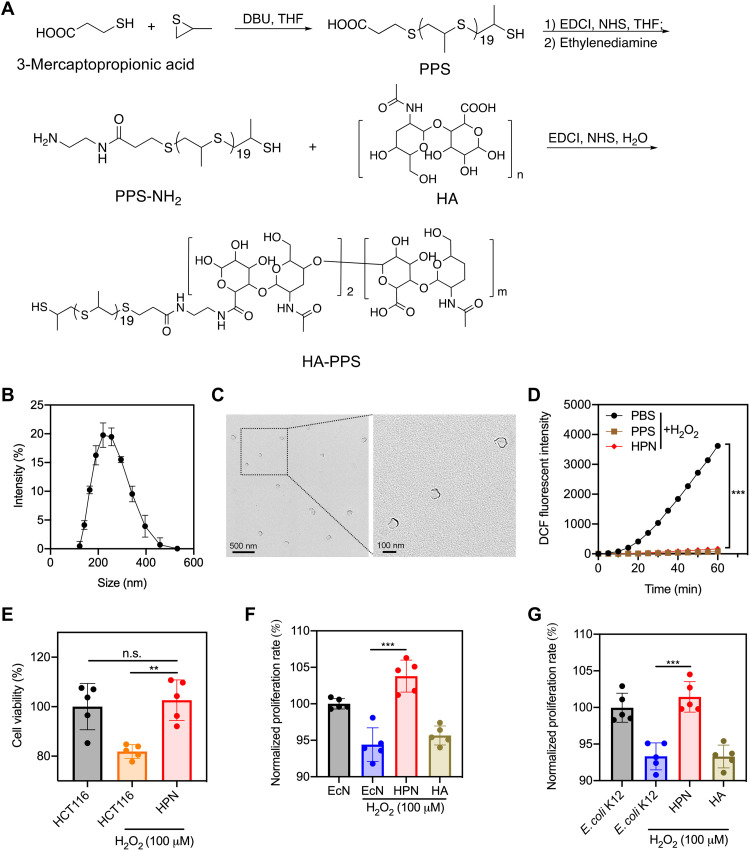

First, we synthesized the PPS polymer with 3-mercaptopropionic acid and propylene sulfide as the starting materials in the presence of a strong base, 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene. The synthesized PPS had 20 units of propane-2-thiol, which was confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (figs. S2 and S3). To conjugate HA to PPS, we used ethylenediamine as the linker. The carboxyl group of PPS was activated by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) under 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDCI) conditions and reacted with ethylenediamine to generate PPS-NH2, which was then amidated with the acid form of HA to prepare the HA-PPS conjugate (Fig. 2A). The structure of HA-PPS was confirmed by NMR. An average density of two molecules of PPS (~40 units of propane-2-thiol) was conjugated on each 100-kDa HA molecule (fig. S4), suggesting a high loading efficacy. PPS could be oxidized in the presence of H2O2, indicating its ROS-scavenging activity (fig. S5). The HA-PPS conjugate in an aqueous buffer self-assembled to form HPN, which was first characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The size of HPN was about 245.2 nm (Fig. 2B and fig. S6A), and the zeta potential was about −26.1 mV (fig. S6B). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to visualize the morphology of HPN shown in Fig. 2C. HPN exhibited significant ROS-scavenging activity measured by dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) fluorescence (Fig. 2D). DCFH-DA is oxidized in the presence of ROS, and this oxidation forms DCF, which can be used as a fluorescent indicator. As a result, the fluorescent intensity is diminished in the presence of HPN. Because of the robust ROS-scavenging activity, HPN was able to protect human colonic epithelial cells (HCT116) against ROS-mediated cytotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 2E, the HPN-treated HCT116 cells displayed significantly higher viability than HCT116 cells after incubation with H2O2 and showed no significant difference compared to HCT116 cells without H2O2 treatment. In addition, HPN conferred protection against ROS-mediated cytotoxicity for two common gut microorganisms, Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) (Fig. 2F) and E. coli K12 (Fig. 2G). This result emphasizes the cytoprotective effect of HPN against ROS-induced cell damage. HPN was more resistant to hyaluronidase-mediated degradation compared to free HA (fig. S7), likely because of the steric hindrance of the HPN nanostructure. The resistance to degradation might enhance its efficacy profile by preventing the quick clearance of the nanoparticle.

Fig. 2. Preparation and characterization of HPN.

(A) General procedures for the synthesis of HA-PPS conjugate. DBU, 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene; THF, tetrahydrofuran. (B) Size distribution of HPN measured by DLS (n = 3). (C) TEM images of HPN. (D) DCF fluorescence intensity after incubation of DCFH-DA (50 μM) with H2O2 (1 mM) in the presence of HPN (1 mg/ml), PPS (80 μg/ml), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (n = 3). (E) Viability of HCT116 cells after 72 hours of incubation in H2O2 conditions (100 μM) with or without HPN treatment (0.5 mg/ml). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). (F and G) The normalized proliferation rate of EcN (F) and E. coli K12 (G) after culturing in the LB medium containing H2O2 (100 μM) with or without HPN treatment (0.5 mg/ml). Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s., not significant.

Preparation and characterization of NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN against environmental assaults

To specifically deliver HPN to regions of inflammation in the colon tissues, we conjugated the HPN onto the bacterial surface of EcN. Following oral administration, the EcN was able to deliver the ROS scavenger to the infected areas due to the probiotic’s colonic colonization effect. Moreover, this bacterial colonization effect is relevant because GI tract–related diseases are usually accompanied by dysregulated microbiota. Previous research has shown that the addition of supplementary commensal bacteria is beneficial for regulating microbiota homeostasis in the GI tract for IBDs. Therefore, conjugating the ROS scavenger HPN onto the surface of probiotics has the potential to exhibit synergy for enhanced therapeutic efficacy in the setting of IBDs.

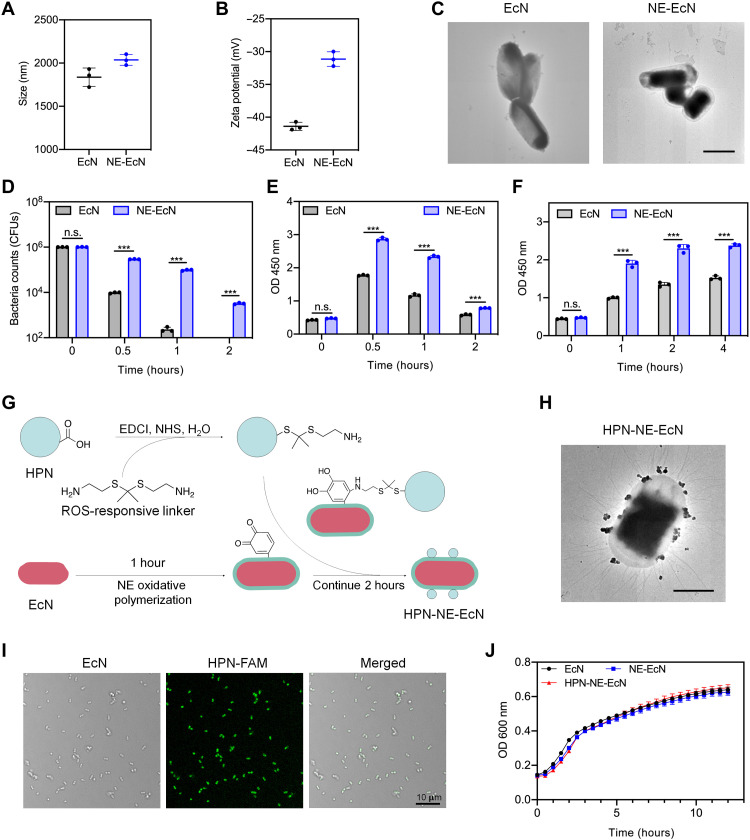

EcN, a well-known probiotic commercially used to modulate intestinal flora, was chosen as the model bacterium in this study. First, EcN was encapsulated with an NE layer to protect the bacteria from the harsh environmental conditions presenting in the GI tract and to extend the retention time of EcN in the intestine. After coating the bacteria with the NE layer, the size of EcN increased from 1837 to 2037 nm (Fig. 3A), and the zeta potential increased from −41.1 to −31.1 mV (Fig. 3B), indicating the existence of the NE layer on the surface of EcN. TEM images showed a transparent outer shell on the EcN (Fig. 3C), further demonstrating that the NE layer was formed and coated on the EcN surface. Next, we investigated whether the NE layer could protect EcN against environmental assaults. When EcN and NE-EcN were subjected to simulated gastric fluid (SGF) supplemented with pepsin that mimics the acidic gastric environment, the viability of NE-EcN was significantly higher than EcN after incubation for 0.5, 1, and 2 hours (Fig. 3D). Notably, there were more than 3 × 103 live bacteria in the NE-EcN group after 2 hours of incubation, whereas almost all uncoated EcN died. It was also found that NE-EcN exhibited enhanced survival rates in bile salts (Fig. 3E) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) containing trypsin (Fig. 3F) compared to uncoated EcN, demonstrating the protective effect of the NE layer on EcN against the external environment assaults. To verify the universality of the NE layer–coating strategy for other live cells, we further coated the NE layer on another bacterial strain, E. coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers (E. coli CC). As shown in the TEM images in fig. S8A, the NE layer was successfully coated on the surface of E. coli CC. Moreover, the NE layer offered protection for E. coli CC strain against external environmental assaults, including SGF (fig. S8B), bile salt (fig. S8C), and SIF (fig. S8D). This finding supports the broad application of the NE layer coating strategy for bacterial protection in the GI environment.

Fig. 3. Preparation and characterization of NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN against environmental assaults.

(A) Sizes and (B) zeta potentials of EcN and NE-EcN measured by DLS. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). (C) TEM images of EcN and NE-EcN. Scale bar, 1 μm. (D to F) Survivals of EcN and NE-EcN after exposure to the following conditions: (D) SGF (pH 1.5) supplemented with pepsin (0.32%), (E) bile salt (0.4%), and (F) SIF (pH 6.8) supplemented with trypsin (10 mg/ml). CFU, colony-forming units. (G) Schematic illustration of HPN-NE-EcN preparation. (H) Representative TEM image of HPN-NE-EcN. Scale bar, 1 μm. (I) LSCM images of HPN-NE-EcN. The green color represented the HPN labeled with FAM. Scale bar, 10 μm. (J) The growth curves of EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN in the LB medium at 37°C were monitored by OD600 values in 30-min intervals via a microplate reader. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test. ***P < 0.001.

To conjugate HPN onto the surface of NE-EcN, a ROS-responsive linker with a terminal amine group was synthesized (40). As shown in fig. S9, the synthesis was started from cysteamine. The amine group of cysteamine was first protected with a trifluoroacetate group to generate intermediate 2, which was further reacted with 2-methoxypropene in the presence of p-toluenesulfonic acid to yield intermediate 3. Hydrolysis of compound 3 under sodium hydroxide gave the ROS-responsive linker. The structures of the intermediates and the ROS-responsive linker were confirmed by NMR (figs. S10 to S12). After incubation of the linker with H2O2 for 4 hours, approximately 40% of the linker was degraded (fig. S13), demonstrating that the linker was ROS responsive. The ROS-responsive linker will facilitate the release of HPN from EcN in the inflamed colon tissues with elevated ROS levels. Next, the carboxyl groups of HPN were activated by NHS and then condensed with one of the amine groups from the linker. The other amine group exposed on HPN served as a reactant group for the autoxidation of NE to form the poly-NE film on the bacterial surface (Fig. 3G). The TEM image shown in Fig. 3H confirmed that HPN was successfully conjugated on the surface of the bacteria. The presence of HPN on the bacterial surface was further characterized by laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM), as evidenced by the fluorescein amidites (FAM)-labeled HPN observed on the surface of EcN (Fig. 3I). The loading efficacy of HPN on the NE-EcN was 92.3% (fig. S14). To examine whether the NE coating and HPN conjugation affected the growth and proliferation of EcN cells, we incubated EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN each in a lysogeny broth (LB) medium, respectively. The growth curves were monitored for 12 hours via optical density at 600 nm (OD600) values. As shown in Fig. 3J, a similar growth rate was found among the three groups, demonstrating that the NE coating and conjugated HPN had a negligible impact on the growth and proliferation of EcN in vitro.

The mucoadhesive capability of HPN-NE-EcN

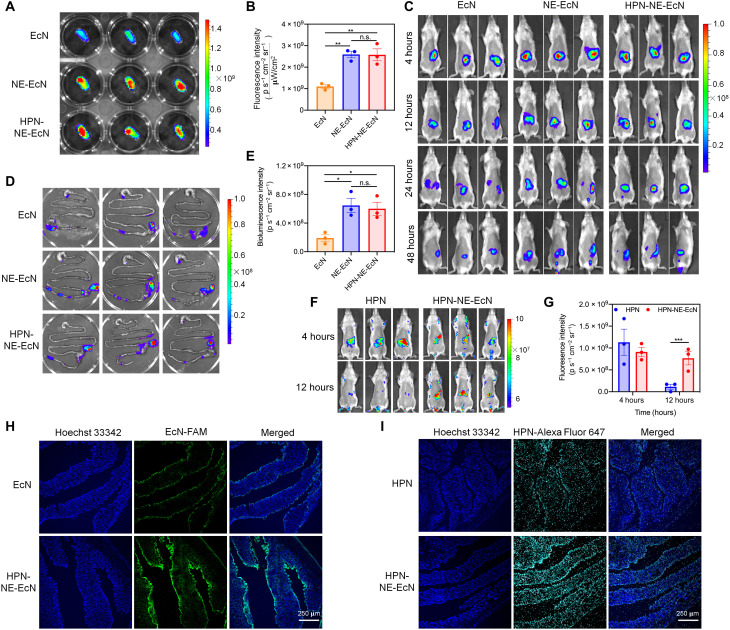

To investigate the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer, we incubated rhodamine B–labeled EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN with freshly collected mouse intestines in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour and then imaged via IVIS after being washed with PBS three times. As shown in Fig. 4 (A and B), the fluorescence intensity of the NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN groups were much higher than that of EcN, demonstrating that the NE layer could improve the adhesive capability of bacteria toward the intestinal mucosa. Moreover, there was no significant difference in fluorescence intensity between NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN groups, suggesting that conjugation of HPN on the surface of NE-EcN would not affect the adhesive capability of the NE layer.

Fig. 4. Mucoadhesive capability of HPN-NE-EcN.

(A) Fluorescence images of ex vivo intestines after incubation with rhodamine B–labeled EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN. (B) Region-of-interest analysis of fluorescence intensities of the intestines. (C) Bioluminescence images of mice administered with various luciferase-expressed bacteria formulations at different time points. (D) Bioluminescence images of mice GI tracts at 48 hours after administration of various luciferase-expressed bacterial formulations. (E) Region-of-interest analysis of bioluminescence intensities of the mice GI tracts at 48 hours. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). (F) Fluorescence images of mice after administration of HPN or HPN-NE-EcN for 4 and 12 hours. (G) Region-of-interest analysis of fluorescence intensities of the mice being given HPN or HPN-NE-EcN. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3). (H) LSCM images of mice colon tissues after 48 hours administration of FAM-labeled EcN or HPN-NE-EcN. The blue color represents Hoechst 33342–stained colon tissues, and the green color represents FAM-labeled EcN cells. (I) Fluorescence images of mice colon tissues at 12 hours after administration of Alexa Fluor 647–labeled HPN or HPN-NE-EcN. The blue color represents colonic cells stained with Hoechst 33342, and the cyan color represents the Alexa Fluor 647–labeled HPN. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Because of the robust mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer observed ex vivo, the intestinal retention time of NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN were further investigated in vivo. The EcN strains were electrotransformed with a fluorescent reporter plasmid, PAKgfpLux2, for in vivo bioluminescence-based imaging. As shown in Fig. 4C and fig. S15, the mice treated with NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN exhibited prolonged retention time compared to the EcN group. The bioluminescence intensity of the NE-EcN and the HPN-NE-EcN groups were significantly higher than that of the EcN group at all measured time points, as evidenced by a slower rate of bioluminescent signal decay in the NE-EcN and the HPN-NE-EcN groups compared to the EcN group. After 48 hours, the mice were euthanized, and the intestines were collected for ex vivo IVIS imaging. As shown in Fig. 4 (D and E), the bioluminescence intensity of NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN groups were 3.4-fold and 3.2-fold higher than that of the EcN group, respectively. This demonstrates the enhanced mucoadhesive capability of bacteria endowed by the NE layer coating. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the bioluminescence intensity between the NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN groups, indicating that conjugation of HPN on bacterial surfaces does not negatively affect the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer. In addition, we also assessed the mucoadhesive capability of NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN in the DSS-induced colitis model. As shown in fig. S16, HPN-NE-EcN and NE-EcN exhibited prolonged retention time in the intestines than nonencapsulated EcN in DSS-induced colitis-bearing mice, which further demonstrated the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer. Next, we investigated whether the conjugation of HPN on the surface of NE-EcN and the prolonged retention time of EcN after NE layer coating would reduce the clearance rate of HPN and also extend the retention time of HPN in the intestines for persistent ROS scavenging. The HPN was first labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 for IVIS imaging. As shown in Fig. 4 (F and G), there was no significant difference in fluorescence between the HPN and HPN-NE-EcN groups at 4 hours. However, after 12 hours, the fluorescence intensity in the HPN group was markedly reduced compared to the HPN-NE-EcN group. The fluorescence intensity of the HPN-NE-EcN group was 7.0-fold higher than that of the HPN group at 12 hours, demonstrating that the conjugation of HPN on NE-EcN prolongs the retention time of HPN in the intestines. In addition, the HPN was not distributed to any other major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, indicating the specificity of the HPN to the intestines (fig. S17).

Next, we evaluated the mucoadhesive capability of HPN-NE-EcN by LSCM. The EcN strains were first labeled with FAM, and HPN was stained with Alexa Fluor 647. After 48 hours of oral administration of EcN and HPN-NE-EcN, the mice were euthanized, and colon tissues were collected for frozen slide preparation. As shown in Fig. 4H and fig. S18A, the green fluorescence in the HPN-NE-EcN group was significantly higher than that in the EcN group, further confirming that the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer prolonged the retention time of EcN. Moreover, after 12 hours, the fluorescence of HPN (cyan color) in the HPN-NE-EcN group was remarkably stronger than that of the HPN group (Fig. 4I and fig. S18B), demonstrating the longer retention time of HPN in the HPN-NE-EcN group compared to the HPN group.

Prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis

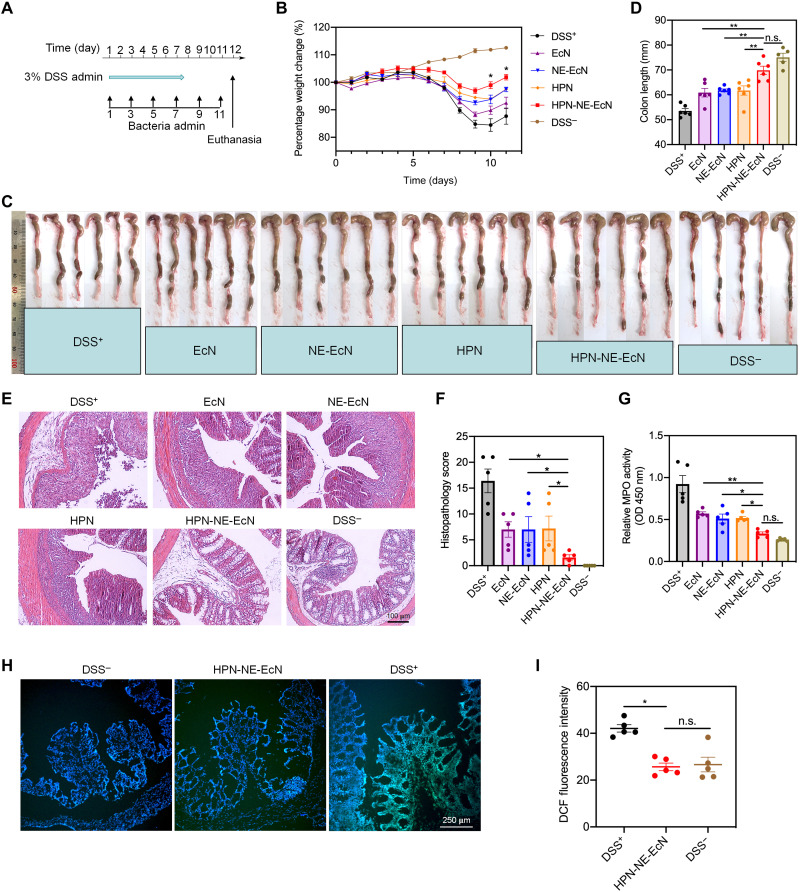

Next, the prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis in vivo was evaluated. First, to investigate whether HPN-NE-EcN treatment could exhibit prophylactic efficacy to protect mice from colitis development, the mice were orally administered various HPN and EcN-based formulations once every 2 days until they were euthanized on day 12 [bacteria dose, 1 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU); HPN, 30 mg/kg]. The mice were simultaneously given DSS for the first 7 days to induce colitis (Fig. 5A). The mice treated with PBS served as the positive control, and the mice without DSS treatment were set as the negative control. The changes in body weight were monitored to intuitively reflect the severity of colitis. As shown in Fig. 5B, all the DSS treatment groups displayed reduced body weight after 5 days of treatment. On day 8, all the HPN and EcN treatment groups displayed attenuated weight loss compared to the DSS+ group, indicating the beneficial efficacy of both HPN and EcN. Notably, the mice treated with HPN-NE-EcN showed substantially less weight loss on day 6 and had the least amount of weight loss compared to the other treatment groups. The initial body weight in the HPN-NE-EcN group was almost fully recovered after 3 days upon discontinuation of DSS therapy, demonstrating the potent prophylactic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis.

Fig. 5. Preventative efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against DSS-induced mouse colitis model.

(A) Schematic of the experimental schedule. Various HPN and EcN formulations were administered every 2 days by oral gavage, and 3% DSS was given in drinking water from days 0 to 7. (B) Percentage weight changes for the colitis-bearing mice treated with various EcN and HPN formulations. The significant analysis was compared between HPN-NE-EcN and NE-EcN. (C) Colon tissue images and (D) quantified colon lengths in different treatment groups. (E) Representative histological images of colon tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and (F) histopathology scores of colon tissues based on H&E images. (G) Relative colonic MPO activities in colon tissues. (H) LSCM images of DCF fluorescence and (I) quantified DCF fluorescence intensities in colon tissues after incubating with DCFH-DA to reflect ROS levels in different treatment groups through ImageJ software. Scale bar, 250 μm. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The deleterious inflammatory response induced by colitis also causes a reduction in colon length as a result of chronic tissue damage. Therefore, mice colons were isolated and imaged (Fig. 5C), and the colon length was summarized to further evaluate colon damage. As shown in Fig. 5D, the mice treated with PBS (DSS+), EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN displayed an average of 28.6, 18.8, 17.6, and 17.7% reduction in colon length compared to that of DSS− control, respectively, while the HPN-NE-EcN group showed only an average of 6.9% reduction, further demonstrating the most prominent protective effect of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis. Next, colon damage levels were evaluated through histological analysis to assess the treatment efficacy, and representative histological images were presented in Fig. 5E. A complete loss of crypt, goblet cell depletion, and immune cell infiltration were observed in the DSS+ group, whereas substantial improvements were found in all EcN and HPN treatment groups. This improvement was especially substantial for the HPN-NE-EcN group, which showed an almost intact epithelium layer and negligible inflammatory cell infiltration. Moreover, a histological scoring system (table S1) related to inflammation severity, depth of injury, crypt cell damage, and percentage of colon tissue involvement was applied to quantitatively evaluate the colon tissue damage levels (41). As shown in Fig. 5F, the histological score for the HPN-NE-EcN group was significantly lower than all other DSS treatment groups, displaying a 10.2-, 4.4-, 4.4-, and 4.5-fold lower score than DSS+, EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN groups, respectively, indicating the superior efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis.

Next, colonic myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, a marker for neutrophil activity, was measured to assess the degree of neutrophil infiltration in colon tissues. As shown in Fig. 5G, the MPO activity of the HPN-NE-EcN group was significantly lower than all other treatment groups while showing no significant difference compared to the DSS− control, indicating the potent anti-inflammatory effect of HPN-NE-EcN. To evaluate the ROS-scavenging ability of HPN-NE-EcN in vivo, we measured the ROS levels in colon tissues using DCF fluorescence imaging. The representative images were shown in Fig. 5H and figs. S19 and S20. It is apparent that the DCF fluorescence represented as green color in the HPN-NE-EcN group was weaker than that of the DSS+ group. Meanwhile, the quantified DCF fluorescence data also revealed that the DCF intensity of the HPN-NE-EcN group was significantly lower than that of the DSS+ group and showed no significant difference when compared to the DSS− groups (Fig. 5I). The results showed recovered ROS levels in colon tissues and indicated the substantial ROS-scavenging capability of HPN-NE-EcN. Furthermore, histological analysis of major organs (fig. S21), including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, indicated negligible side effects caused by HPN-NE-EcN.

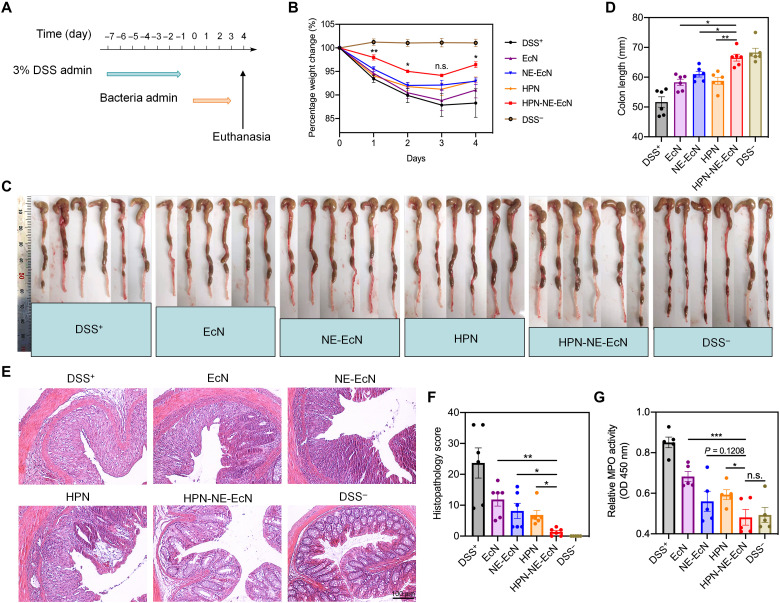

To validate the therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against IBDs, we first developed the mouse colitis model by feeding DSS to mice for 7 days without treatment. Afterward, the DSS was discontinued, and different formulations of EcN and HPN (bacteria dose, 1 × 108 CFU; HPN, 30 mg/kg) were orally administered for four consecutive days (Fig. 6A), and body weights were monitored. As shown in Fig. 6B, the mice of the HPN-NE-EcN group displayed ameliorated weight loss during the duration of a 4-day time-course therapy, and the weight loss was significantly lower than that of all other treatment groups from day 2. Moreover, the colon length in the HPN-NE-EcN group was significantly longer than that in the other DSS treatment groups (Fig. 6, C and D). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed that the lowest colon damage occurred in the HPN-NE-EcN group (Fig. 6E), and the histological score for the HPN-NE-EcN group was also significantly lower compared to all other DSS treatment groups (Fig. 6F). In addition, MPO activity in colon tissues of the HPN-NE-EcN group was substantially lower than that of other DSS treatment groups and had no significant difference when compared to the DSS− control (Fig. 6G).

Fig. 6. Therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against DSS-induced mouse colitis model.

(A) Schematic of the treatment plan. The mice were administered with 3% DSS from days 0 to 7 to induce the colitis. Afterward, different formulations of EcN and HPN were given to the mice for 4 days to assess their therapeutic efficacy. (B) Percent weight changes of colitis-bearing mice in different treatment groups. The significant analysis was compared between HPN-NE-EcN and NE-EcN. (C) Colon images and (D) quantified colon lengths in different treatment groups. (E) Representative H&E-stained colon tissue images and (F) histopathology scores of colon tissues to evaluate colon damage. Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) Relative MPO activities in colon tissues to reflect colonic inflammation levels in different treatment groups. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 6). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To assess the reproducibility of the therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN in vivo, we established the DSS-induced mouse colitis model and treated it with various formulations. Moreover, two additional groups were added, which were an increased dose of HPN (60 mg/kg) and a physical mixture of HPN and NE-EcN (HPN + NE-EcN). Consistent with the previous results, the HPN-NE-EcN treatment displayed superior therapeutic efficacy compared to all other treatment groups, as evidenced by delayed weight loss, longer colon length, and minimized colon damage (fig. S22). Moreover, as shown in fig. S22 (B to D), the weight loss in the HPN-2 group (60 mg/kg) was significantly lower than the mice treated with HPN-1 (30 mg/kg). The colon length in the HPN-2 group was longer than that in the HPN-1 group, indicating the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of increasing the amount of HPN. Therefore, there is the possibility that increasing the dose or more frequent administration of HPN may result in enhanced therapeutic efficacy as HPN-NE-EcN against colitis. Notably, although there is no significant difference in body weight change (P = 0.16) between HPN-NE-EcN and HPN + NE-EcN, both the colon lengths and colon damage scores displayed significant improvement in HPN-NE-EcN groups than those in HPN + NE-EcN groups, demonstrating the significantly enhanced treatment efficacy. Moreover, histological analysis of major organs (fig. S23), including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, along with the complete blood count (table S2), indicated no significant side effects caused by all treatment groups. Together, HPN-NE-EcN exhibited potent prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy for the treatment of colitis.

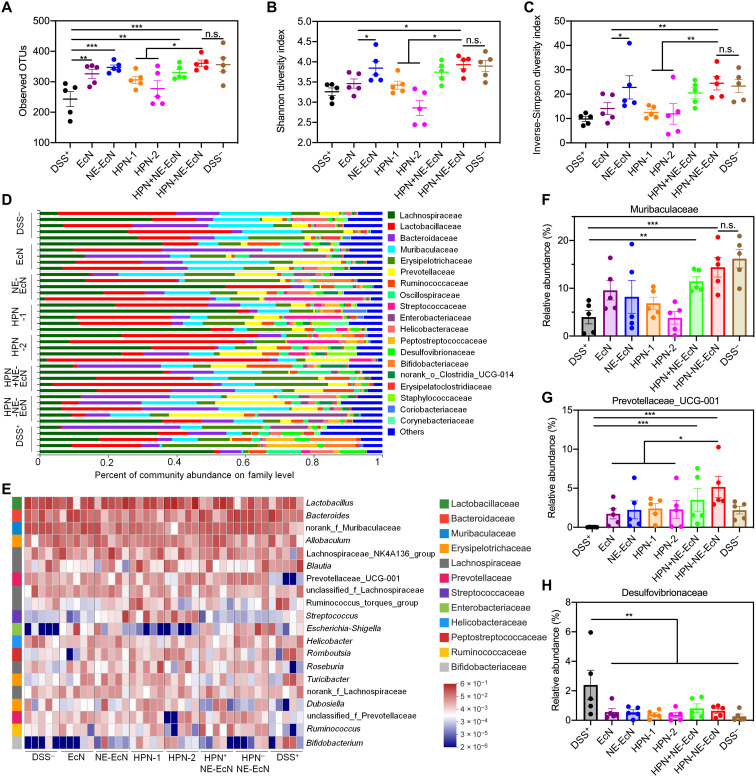

Modulatory effect of HPN-NE-EcN on the gut microbiome

Because of the fact that probiotics can modulate the gut microbiota and exert beneficial effects on the host (3, 42), we examined the gut microbiota composition change after various treatments in DSS-induced colitis-bearing mice. After treatment of various formulations of EcN and HPN for 4 days, the feces were collected and analyzed via the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing assay. As shown in Fig. 7A, the bacterial richness that presented as observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in all EcN treatment groups was significantly higher than that in the DSS+ group, and the bacterial richness in the HPN-NE-EcN group was remarkably higher than that in HPN groups, indicating the beneficial effects of EcN on gut microbiota modulation. In addition, the gut microbiome α-diversity showed as Shannon (Fig. 7B) and inverse-Simpson index (Fig. 7C) in the HPN-NE-EcN group and the NE-EcN group were remarkably higher than that in the EcN group because of the protective and mucoadhesive capacity of the NE layer that increased the richness of EcN in the intestine. Moreover, the β-diversity analysis of the gut microbiome using principal coordinates analysis plot with Bray-Curtis dissimilarity as a metric showed that mice in the HPN-NE-EcN group exhibited distinct gut microbiota profiles compared to mice in the other treatment groups (fig. S24). Further investigation at the family (Fig. 7D) and genus (Fig. 7E) levels revealed that the HPN-NE-EcN treatment significantly increased the relative abundance of the beneficial bacteria Muribaculaceae (known to regulate inflammatory responses) (Fig. 7F) (43) and Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 (known to produce short-chain fatty acids) (Fig. 7G) (44), which were prominently decreased in the DSS+ group. Moreover, after treatment with various EcN and HPN formulations, the relative abundance of Desulfovibrionaceae (known to produce lipopolysaccharides and damage the gut barrier) (Fig. 7H) (45), a virulent pathogen that would worsen colitis, was markedly reduced. Overall, in DSS-induced colitis-bearing mice, the NE-EcN and HPN-NE-EcN could effectively increase the abundance of beneficial bacteria, decrease pathogens, and improve the richness and diversity of the gut microbiome to regulate the composition of the gut microbiota, contributing to the enhanced therapeutic efficacy against colitis.

Fig. 7. HPN-NE-EcN modulates the gut microbiome homeostasis in the DSS-induced mouse colitis model.

(A) Observed operational taxonomic unit (OTU) richness of the gut microbiota in mice after different treatments. (B and C) The gut microbiome α-diversity analysis via Shannon index (B), and inverse-Simpson index (C). (D) Relative abundance of gut microbiome at family levels in mice after different treatments. (E) Heatmap illustration of relative abundance of gut microbes at genus levels in mice after different treatments. The prefix of “norank_f_” refer to OTUs in their family that could not be classified at the genus level. (F to H) Relative abundance of Muribaculaceae (F), Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 (G), and Desulfovibrionaceae (H) in the gut microbiome of mice treated with different groups. Muribaculaceae and Desulfovibrionaceae in (F) and (H) refer to OTUs in their family that could not be classified at the genus level. Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 5). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In summary, given the overproduced ROS levels and disordered microbiota in the intestinal microenvironment of GI tract–related diseases, we prepared a platform of HPN-NE-EcN capable of preventing and mitigating the detrimental effects associated with IBDs. The HPN nanoparticles, self-assembled from the synthesized molecule of HA-PPS, exhibited potent ROS-scavenging capability and could protect colonic epithelial cells, as well as the microbiome, including EcN and E. coli K12 strains from oxidative stress–induced damages. The commensal bacteria of EcN that are beneficial for regulating the balance of intestinal flora were further encapsulated with the NE layer on their surface. The generated NE layer provides EcN resistance against a variety of environmental assaults to improve viability in oral delivery. Moreover, the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer endowed the EcN bacteria with prolonged retention time in the intestine for enhanced therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, the probiotic EcN is an effective colon-targeted carrier due to the natural colon tissue colonization property. Thus, except for the intestinal flora modulation property of EcN, the generated platform of HPN-NE-EcN by conjugating HPN on the surface of EcN via a ROS-responsive linker could also effectively deliver HPN to inflammatory colon tissues for targeted ROS scavenging. Moreover, the prolonged retention time of HPN-NE-EcN due to the mucoadhesive capability of the NE layer decreased the clearance of HPN for persistently scavenging ROS in colon tissues. Notably, the NE layer–coating strategy can be adapted to encapsulate other live cells for cytoprotection, and the NE layer coating, as well as HPN conjugation, would not affect the growth and proliferation of EcN. Meanwhile, the HPN nanoparticles could self-degrade after completely reacting with ROS due to the physicochemical transformation of PPS from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, and this improves the safety profile of this approach. The synergized effectiveness of HPN-NE-EcN for simultaneously scavenging ROS and modulating microbiota homeostasis in colonic microenvironments provided significantly enhanced prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy against DSS-induced colitis. Because of the studies reported that many E. coli strains including EcN have the possibility of pathogenicity to promote colon cancer (46), the safety of the EcN strain developed in this study needs to be further evaluated before clinical applications, and the strategy needs to be tested with other beneficial bacteria as carriers for further translation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All commercially available reagents were used without further purification as described in our previous study (26). Anhydrous solvents were dried through routine protocols. All chemical reactions were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere in dry glassware with magnetic stirring. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using 0.25-mm silica gel plates (GF254), and column chromatography was carried out on 200- to 300-mesh silica gel. The NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 spectrometer. The main chemicals and biological material used in this study are listed below: hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%, Lab Chem), NHS (Alfa Aesar), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Alfa Aesar), trypsin from porcine pancreas (Sigma-Aldrich), pepsin powder (Thermo Fisher Scientific), bile salts (Sigma-Aldrich), ampicillin (Sigma-Aldrich), DSS salt (molecular weight 40,000, Alfa Aesar), LB (Fisher Bioreagents), agar (Fisher Bioreagents), hydrogen peroxide solution (H2O2, Sigma-Aldrich), sodium chloride (NaCl, Fisher Chemical), Hoechst 33342 trihydrochloride (Life Technologies), cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Apexbio), DCFH-DA (Sigma-Aldrich), and isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Chem-Impex). The LB liquid medium was prepared using 25 g of LB powder in 1 liter of deionized (DI) water and was then autoclaved. LB agar plates were prepared on dishes using 20 ml of LB agar solution (25 g of LB and 12 g of agar in 1 liter of DI water). SGF and SIF was prepared as described in the United States Pharmacopoeia. Briefly, SGF was prepared by dissolving 2.0 g of NaCl and 3.2 g of pepsin in 1 liter of DI water, and the pH was adjusted to 1.5 with HCl. The SGF was filtered by a 0.22-μm membrane before usage. SIF was prepared by dissolving 6.8 g of KH2PO4 and 10 g of trypsin in 1 liter of DI water, and the pH was adjusted to 6.8 with NaOH. The SIF was filtered by a 0.22-μm membrane before usage.

Methods

Synthesis of HA-PPS conjugate

PPS

To a stirred solution of 100 μl (1.15 mmol) of 3-mercaptopropionic acid in 30 ml of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran was added 524 μl (3.45 mmol) of 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]-7-undecane in an ice bath under stirring, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min under a nitrogen atmosphere. Then, 1.9 ml (21.15 mmol) of propylene sulfide was added dropwise, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir at 60°C overnight. After that, the reaction was quenched by adding 5 ml of H2O, purified by precipitation in cold methanol, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to produce PPS as yellow oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.03 to 2.83 (m, CH2), 2.72 to 2.56 (m, CH), and 1.47 to 1.30 (d, CH3); mass spectrum (electrospray ionization) mass/charge ratio (m/z) 1587.2 (M-H)− (C63H125O2S21 requires 1587.3).

PPS-NH2

To a stirred solution of 158.6 mg (100 μmol) of PPS in 20 ml of dichloromethane was added 23 mg (200 μmol) of NHS and 48 mg (250 μmol) of EDCI, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 30 min. Then, 133 μl (2 mmol) of ethylenediamine was added dropwise to the mixture, and stirring was continued overnight at room temperature. After that, the reaction mixture was diluted by adding 20 ml of dichloromethane, washed successively with H2O and brine, dried over MgSO4, and filtered. The solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure to give PPS-NH2, which was used directly without further purification.

HA-PPS conjugate

Before synthesizing the HA-PPS conjugate, the acid form of HA was prepared from HA sodium salt. Briefly, HA sodium salt was dialyzed in 0.01 M HCl solution overnight and then lyophilized to produce the acid form of HA. HA (100 mg) was dissolved in 10 ml of H2O, and 7 mg (60 μmol) of NHS and 14.5 mg (75 μmol) of EDCI were added. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. Then, a solution containing 40 mg of PPS-NH2 in 1 ml of tetrahydrofuran was added dropwise, and the stirring was continued for another 24 hours at room temperature under nitrogen protection. After that, the mixture was dialyzed against water/methanol at a ratio of 1:1 three times for 1 day, followed by distilled water three times for 1 day. The solvent was removed by lyophilization to generate the HA-PPS conjugate. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O/acetone-D6 1:1) δ 4.76 to 4.56 (m, 252H), 4.10 to 3.89 (m, 639H), 3.83 to 3.62 (m, 628H), 3.02 to 2.88 (m, 26H, CH2 on PPS), 2.72 to 2.64 (m, 13H, CH on PPS), 2.43 to 2.33 (m, 372H, CH3 on HA), and 1.56 to 1.35 (m, 39H, CH3 on PPS).

Synthesis of the ROS-responsive linker

2,2,2-Trifluoro-N-(2-mercaptoethyl)acetamide (2)

To a stirred solution of 5 g (64.8 mmol) of cysteamine in 100 ml of methanol was added 9.3 ml (77.8 mmol) of ethyl trifluoroacetate and 13.5 ml (97.2 mmol) of triethylamine, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. After that, the solvent of methanol was evaporated under reduced pressure, and 100 ml of dichloromethane was added. The mixture was then washed with water and brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the crude product. The residue was purified by chromatography on a silica gel column to afford compound 2: yield 7.6 g (68%); silica gel TLC Rf 0.5 (5:1 hexane-EtOAc); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.81 (s, 1H), 3.56 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.82 to 2.70 (m, 2H), and 1.42 (t, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H).

N,N′-((Propane-2,2-diylbis(sulfanediyl))bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(2,2,2-trifluoroacetamide) (3)

To a stirred solution of 7.5 g (43.4 mmol) of compound 2 in 100 ml of dry tetrahydrofuran was added 900 mg (5.22 mmol) of p-toluenesulfonic acid at room temperature under nitrogen protection, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 10 min. Then, 50 g of molecular sieves was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 30 min. Next, 1.25 g (17.4 mmol) of 2-methoxypropene was added to the reaction mixture, and the stirring was continued for 24 hours at room temperature. After that, the tetrahydrofuran solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and 100 ml of dichloromethane was added. The mixture was then washed with water and brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by chromatography on a silica gel column to give the compound 3: yield 3.1 g (37%); silica gel TLC Rf 0.5 (3:1 hexane-EtOAc); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.84 (s, 2H), 3.60 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 2.85 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 4H), and 1.63 (s, 6H).

2,2′-(Propane-2,2-diylbis(sulfanediyl))bis(ethan-1-amine) (ROS-responsive linker)

Compound 3 [3.0 g (7.8 mmol)] was dissolved in 20 ml of NaOH (6 M), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 hours. Then, the reaction mixture was extracted by dichloromethane, washed with brine, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the pure ROS-responsive linker quantitatively: yield 1.5 g; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.92 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 2.74 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 4H), 1.62 (s, 6H), and 1.35 (s, 4H).

Preparation and characterization of HPN

HA-PPS conjugate was dissolved in the distilled water, and ultrasonication (at intervals of 2 s on and 2 s off) was performed for 10 min in an ice bath to prepare HPN nanoparticles. The nanoparticle size and zeta potential of HPN were measured by DLS. The morphologies of HPN were visualized by TEM (FEI Tecnai T12). Briefly, a drop of HPN solution was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid. After completely drying, the sample was imaged by TEM.

The ROS-scavenging activity of HPN

The ROS-scavenging activity of HPN was determined by measuring the fluorescent signals of DCF oxidized from DCFH-DA by peroxy radicals in the presence of HPN. PBS and PPS were used as control groups. Briefly, 50 μM of DCFH-DA in PBS was incubated with 1 mM H2O2 in the presence of PBS, PPS (80 μg/ml), and HPN (1 mg/ml) at 37°C. The fluorescent signals were monitored using a microplate reader (Infinite M Plex, Tecan) for 1 hour (excitation, 490 nm and emission, 520 nm).

Resistance of HPN against hyaluronidase-mediated degradation

The degraded product of HA by hyaluronidase, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, was measured by a colorimetric method to assess the hyaluronidase-mediated degradation of HPN. Briefly, HA and HPN (1 mg/ml) were separately incubated with hyaluronidase (150 U/ml) in pH 6.0 PBS buffer at 37°C. At predetermined time points, 100 μl of samples was taken and diluted by 400 μl of PBS. The mixture was kept at 100°C for 5 min to stop the enzymatic reaction. Next, 100 μl of 0.8 M potassium tetraborate (pH 9.0) was added to the mixture. After being kept at 100°C for 3 min, the mixture was cooled in water, and 3 ml of p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (DMAB) reagent (10 g of DMAB dissolved in 100 ml of acetic acid containing 12.5% of 10 M HCl) was added. The OD544 values were measured within 5 min by a microplate reader to evaluate the level of hyaluronan breakdown product.

Strains and culture conditions

The strains EcN, E. coli K12, and E. coli CC were used in this study. The bacterial cells were cultured on an LB agar plate (1.5% agar). Before each experiment, the cells were cultured in liquid LB medium overnight at the shaking speed of 225 rpm at 37°C.

Cytoprotective effect of HPN against ROS-induced damage

The protective effect of HPN against ROS-induced damage was measured in colonic epithelial cells (HCT116) and bacteria (EcN and E. coli K12), respectively, using a CCK-8 assay. Briefly, for the colonic epithelial cells, HCT116 cells (8 × 103 per well) were cultured in a 96-well plate for 24 hours at 37°C. Then, the culture medium was removed, and 100 μl of fresh medium and fresh medium containing 100 μM of H2O2 with or without HPN (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well. After incubation for 72 hours, the cells were washed with culture medium, and then fresh medium (100 μl) was added to each well, followed by the addition of 10 μl of CCK-8 solution. After incubation for 1 hour at 37°C, the OD450 values were measured using a microplate reader. The cell viability was normalized to HCT116 cells without H2O2 and HPN treatments.

For bacterial strains, 100 μl of EcN and E. coli K12 in LB medium or LB medium containing H2O2 (100 μM) with or without HPN (0.5 mg/ml) were separately seeded into a 96-well plate with an initial OD600 value ~0.15 and incubated for 12 hours. Afterward, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for an additional 1 hour. The OD values were recorded at 450 nm by a microplate reader, and the viability was normalized to bacteria without H2O2 and HPN treatments.

Encapsulation of EcN with the NE layer and characterization of NE-EcN

The EcN cells, picked from an LB agar plate, were cultured in an LB medium at 37°C overnight. After the EcN cells were washed with PBS twice, NE solution (0.5 mg/ml) in PBS was added and incubated for 3 hours at a shaking speed of 200 rpm. The formed NE-EcN cells were collected by centrifugation after being washed with PBS three times to remove residual NE molecules. The formed NE layer on the bacterial surface was characterized by TEM. Briefly, a drop of NE-EcN solution in DI water was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid. After completely drying, the sample was imaged by TEM. Moreover, the sizes and zeta potentials of EcN and NE-EcN were determined by DLS.

External environment resistance assay for NE-EcN

The protective effects of the NE layer on EcN against simulated GI conditions, including SGF (pH 1.5) supplemented with pepsin (0.32%), SIF (pH 6.8) supplemented with trypsin (10 mg/ml), and bile salts (0.4%), were measured. Briefly, for the SGF resistance assay, equal amounts of EcN and NE-EcN were separately subjected to SGF and incubated at 37°C with a shaking speed of 225 rpm. At predetermined time points, 50 μl of the sample was taken, washed with PBS, and spread on LB agar plates in sequential 10-fold dilutions. The colonies were counted after 24 hours of incubation at 37°C. For resistance against SIF and bile salt, equal amounts of EcN and NE-EcN were separately subjected to SIF and bile salts in the LB medium. At predetermined time points, the samples were collected and washed with PBS. After that, the samples were resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, followed by adding 10 μl of CCK-8 solution, and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The OD450 values were recorded to evaluate the cell viability.

Preparation and characterization of HPN-NE-EcN

To prepare the ROS-responsive linker bound to HPN, the HA-PPS molecule was first reacted with sulfo-NHS to produce HA-PPS-NHS. Briefly, to a stirred solution of 20 mg of HA-PPS in 10 ml of distilled water was added 10 mg (0.05 mmol) of EDCI and 4 mg (0.02 mmol) of sulfo-NHS, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 4 hours at room temperature to generate HA-PPS-NHS. After dialysis to remove residual EDCI and sulfo-NHS, the solution of HA-PPS-NHS was ultrasonicated to prepare the sulfo-NHS exposed HPN nanoparticle, which was then reacted with the ROS-responsive linker (20 mg, 0.1 mmol) at room temperature overnight to prepare the ROS linker–exposed HPN. The generated HPN was collected by centrifugation and washed with water three times to remove the residual ROS linker. Next, the EcN cells were incubated in the NE solution (0.5 mg/ml) in PBS for 1 hour at a shaking speed of 200 rpm. Then, the ROS linker–exposed HPN was added, and the mixture was incubated for another 2 hours. The generated HPN-NE-EcN was collected by centrifugation at 4000 rpm and washed with water three times to remove the residual HPN nanoparticles.

The formed HPN-NE-EcN was first characterized by TEM images. Briefly, the HPN-NE-EcN solution in distilled water was deposited on the surface of the carbon-coated copper grid. After completely drying, one droplet of UranyLess was dropped on the grid surface and kept for 3 min. Then, the grid was washed with distilled water and dried in the air. Next, the dried grid was placed on a 3% lead citrate droplet for 3 min. After washing in distilled water, the grid was dried in the air, and images were taken by TEM. The HPN-NE-EcN was further characterized by LSCM (Nikon A1RS). To be imaged by LSCM, HA-PPS was first labeled with FAM fluorescence before making HPN-NE-EcN. Briefly, HA-PPS was dissolved in water. NHS and EDCI were added to the mixture, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 min. Then, FAM-NH2 was added, and the stirring was continued for 4 hours. After that, the mixture was dialyzed in water for 2 days to remove the residual FAM fluorescence. Next, the FAM-labeled HA-PPS was used to prepare the HPN-NE-EcN as described above, and the resulting HPN-NE-EcN was imaged by LSCM. Moreover, the loading efficacy of the HPN on the surface of the bacteria was quantified by fluorescence measurement. Briefly, the concentration of HPN correlated with fluorescence was quantified, and a standard curve was created. After preparing the HPN-NE-EcN, the amount of HPN conjugated on the bacterial surface was quantified according to a standard curve.

Measurement of growth curves of EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN

To assess whether the NE layer and HPN nanoparticles on the surface of EcN would affect the growth and proliferation of EcN, the growth curves of EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN were measured. Briefly, after encapsulating EcN with the NE layer and conjugating HPN on the surface of NE-EcN, the bacteria were diluted and seeded into a 96-well plate with an OD600 value of ~0.15 and incubated at 37°C with gentle shaking. The OD600 values were monitored every 0.5 for 12 hours in total by a microplate reader. Uncoated EcN was used as a control.

Electrotransformation of EcN with PAKgfpLux2

The EcN cells were electrotransformed with a fluorescent reporter plasmid, PAKgfpLux2, for IVIS imaging to monitor the distribution of bacteria in vivo. Briefly, EcN cells (1 × 109 CFU) were collected and washed with distilled water three times to remove ions from PBS. Then, the EcN cells were resuspended in 40 μl of distilled water and mixed with 1 μl of the PAKgfpLux2 plasmid at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. The mixture was kept on ice for 1 min before being transferred to a prechilled electroporation cuvette (0.1 cm), and the bacterial suspension was tapped to the bottom of the cuvette to eliminate bubbles. Next, the cuvette was placed into a chamber. After being pulsed once (1.8 kV, 4 ms, MicroPulser, Bio-Rad), the cuvette was removed from the chamber, and 1 ml of LB medium was added immediately. The cell suspension was then transferred to a cell culture tube and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Afterward, the bacteria were collected by centrifugation and spread on an LB agar plate containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) for selection and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Evaluation of the adhesive effect of HPN-NE-EcN in vivo

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. To investigate the adhesive effect of HPN-NE-EcN in the intestine, the EcN cells were initially electrotransformed with the PAKgfpLux2 plasmid, as described above. Then, the EcN cells were encapsulated with the NE layer and further conjugated with HPN on the bacterial surface. The generated HPN-NE-EcN was orally administered to mice, and the distribution of EcN was monitored through bioluminescence signals via an IVIS. Briefly, mice (female, 6 to 8 weeks old) were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 3 in each group). Before administration of the EcN formulations, the mice were fasted for 18 hours but were given drinking water containing IPTG (5 g/liter) and ampicillin (1 g/liter). Moreover, the bioluminescence of EcN cells was induced by IPTG (1 mM) for 4 hours before administration. Then, 100 μl of EcN, NE-EcN, and HPN-NE-EcN (bacteria dose, 1 × 108 CFU) in PBS was orally administered, respectively. Afterward, the mice were given normal chow with IPTG and ampicillin in the drinking water. At 4, 12, 24, and 48 hours, bioluminescence in the mice was detected by an IVIS. Furthermore, the mice were euthanized after 48 hours of receiving the different EcN formulations, and the GI tracts were isolated and imaged.

To visualize HPN nanoparticles in mice, the HPN was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 before preparing HPN-NE-EcN. Briefly, 15 mg of the prepared HA-PPS-NHS was dissolved in 10 ml of distilled water, and 0.3 mg of Alexa Fluor 647-NH2 was added to the solution. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight to generate the Alexa Fluor 647–labeled HA-PPS molecule, which was dialyzed in distilled water for 2 days to remove the residual free fluorophore. The fluorescence-labeled HA-PPS was used to prepare the HPN and HPN-NE-EcN for visualizing the HPN in vivo. After receiving the HPN and HPN-NE-EcN (7.5 mg/kg) for 4 and 12 hours, the mice were imaged via IVIS to visualize the HPN.

The fluorescent signals of EcN cells and HPN nanoparticles in the intestine were also imaged by LSCM. Briefly, EcN cells were labeled with FAM, and the HPN nanoparticles were marked by Alexa Fluor 647. Then, the HPN-NE-EcN was prepared using FAM-labeled EcN and Alexa Fluor 647–labeled HPN. After 48 hours of receiving EcN and HPN-NE-EcN (bacteria dose, 1 × 108 CFU), the mice were euthanized, and the colon tissues were isolated for frozen-slide preparation. The frozen slides were then fixed, dehydrated, and imaged by LSCM to visualize the fluorescence of EcN. For visualizing the HPN nanoparticles, the mice were given HPN and HPN-NE-EcN (7.5 mg/kg), respectively. After 12 hours, the mice were euthanized, colon tissues were isolated, and the frozen slides of colon tissues were prepared. Then, the slides were imaged by LSCM.

Prophylactic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against DSS-induced colitis

The prophylactic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against GI tract–related diseases was evaluated in a DSS-induced mouse colitis model. Briefly, mice (female, aged 6 to 8 weeks) were randomly divided into six groups: PBS-DSS−, PBS-DSS+, EcN, NE-EcN, HPN, and HPN-NE-EcN (n = 6). The mice were given various EcN and HPN formulations (bacteria dose, 1 × 108 CFU; HPN, 30 mg/kg) on the basis of their group assignment via oral gavage every 2 days throughout the experimental period. DSS (3%) was added to the drinking water for the first 7 days to induce colitis except for the PBS-DSS− group. After 7 days, DSS was removed, and all mice were given normal drinking water. On day 11, the mice were euthanized, and the colon length was measured. A few major organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. Moreover, colon tissues were collected and separated into several sections for further analysis. In addition, mouse body weight was recorded daily.

Therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against DSS-induced colitis

First, colitis was induced in the mice, and the mice were given different formulations of HPN and EcN to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against colitis. Briefly, the mice were randomly assigned to six groups (PBS-DSS−, PBS-DSS+, EcN, NE-EcN, HPN, and HPN-NE-EcN; n = 6). The mice were given drinking water containing 3% DSS for 7 days to induce colitis. Afterward, the mice were given normal drinking water, and various HPN and EcN formulations (bacteria dose, 1 × 108 CFU; HPN, 30 mg/kg) were administered for 4 days. After that, the mice were euthanized, and the colon length was measured. Colon tissues were harvested and separated into several sections for further analysis. Moreover, the body weights of all the mice were recorded daily.

Moreover, the repeated experiment to further substantiate the therapeutic efficacy of HPN-NE-EcN against DSS-induced mouse colitis was performed according to the protocol above, with n = 8 per group. Notably, two additional groups of HPN-2 (an increased dose of HPN to 60 mg/kg) and HPN + NE-EcN (a physical mixture of HPN and NE-EcN) were added in this experiment.

Histopathology studies

The histopathology analysis for evaluating colon damage was performed according to standard procedures for paraffin embedding and H&E staining. Following procedures previously described in our study (26). Briefly, the colonic tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution, embedded in paraffin, sectioned (4 μm), and stained with H&E. The resulting slides were scanned using a Nikon Intensilight fluorescence microscope. Each section was scored blindly by a trained pathologist for histological evidence of colon damage by DSS with a scoring system described in table S1. The scoring system presented in the supporting information included the severity of inflammation, depth of injury, the extent of crypt damage, and percentage of colon tissue involvement.

MPO assay

Colonic MPO, a marker for neutrophil infiltration, was measured to evaluate the level of inflammation in colon tissues. Briefly, the colon tissues were isolated from mice in prophylactic and therapeutic experiments and were weighed and washed thoroughly with PBS to clean the fecal matter. Next, the samples were homogenized in 0.5% of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (fivefold volume/weight) in PBS (pH 6.0), freeze-thawed three times, and sonicated for 10 s to give a homogeneous tissue suspension. Afterward, the clear supernatant was collected by centrifugation at a speed of 20,000g at 4°C for 20 min. Subsequently, 50 μl of supernatant was added to a 96-well plate, and 200 μl of dianisidine dihydrochloride (1 mg/ml) containing 0.005% (v/v) H2O2 in PBS (pH 6.0) was added. The plate was incubated for 20 min at room temperature. OD450 values were measured to represent the MPO expression levels.

Evaluation of ROS levels in colon tissues

The ROS-scavenging capability of HPN-NE-EcN was further evaluated in vivo. Briefly, colon tissues were immersed in 50 μM DCFH-DA solution in PBS immediately after being isolated from the mice in the prophylactic experiment and were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Afterward, the colon tissues were washed with PBS three times to remove free DCFH-DA, and frozen slides for the colon tissues were prepared. Next, the frozen slides were fixed in precooled (−20°C) acetone for 10 min. The slides were dried in the air for 20 min and rinsed with PBS twice for 5 min each time. Afterward, the slides were incubated in Hoechst 33342 solution with PBS for 10 min and then rinsed with water four times to remove the residual Hoechst 33342. Next, the slides were dehydrated through four changes of ethanol (95, 95, 100, and 100%) for 5 min each. After evaporation of ethanol, the slides were covered with a coverslip using Permount solution and imaged by LSCM.

Microbiome analysis

After different treatments in DSS-induced colitis-bearing mice, the feces were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately, and prepared for gut microbiome analysis by 16S sequencing assay. Briefly, microbial community genomic DNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A. soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.), and the extracts were measured on 1% agarose gel. The concentration and purity of the extracts were determined by NanoDrop 2000 ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, USA). The hypervariable region V3-V4 of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with primer pairs 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) by an ABI GeneAmp 9700 polymerase chain reaction thermocycler (ABI, CA, USA). The product was extracted by agarose gel. Then, the extracts were purified and quantified by the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen Biosciences, Union City, CA, USA) and Quantus Fluorometer (Promega, USA), respectively. On an Illumina MiSeq PE300 platform/NovaSeq PE250 platform, purified amplicons were pooled in an equimolar fashion and sequenced paired-end (Illumina, San Diego, USA). The raw 16S rRNA gene sequencing reads were demultiplexed, quality-filtered by fastp version 0.20.0, and merged by FLASH version 1.2.7. Using UPARSE version 7.1, OTUs with a 97% similarity criterion were grouped, and chimeric sequences were detected and eliminated. The taxonomy of each OTU representative sequence was analyzed by RDP Classifier version 2.2 against the 16S rRNA database.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was evaluated using GraphPad Prism 8. The statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis followed by Tukey’s or Fisher’s least significant difference multiple comparisons. The differences between experimental and control groups were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. (n.s.) P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n.s., not significant).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge G. Kwon’s laboratory for help with nanoparticle characterization. We also want to thank the optical imaging core, small animal facilities, and histological core at UWCCC for help with this study.

Funding: This work was supported by the P30CA014520-UW Carbone Cancer Center support grant (CCSG), UWCCC Immunology/Immunotherapy Pilot award, and the start-up package from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Author contributions: J.L. and Q.H. conceived and designed the study. J.L., Y.W., W.J.H., Y.C., and Z.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. All the authors contributed to manuscript writing and editing.

Competing interests: Q.H. and J.L. are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison (no. 63396409, filed 9 August 2022). The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S24

Tables S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Liu Y., Cheng Y., Zhang H., Zhou M., Yu Y., Lin S., Jiang B., Zhao X., Miao L., Wei C.-W., Integrated cascade nanozyme catalyzes in vivo ROS scavenging for anti-inflammatory therapy. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb2695 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertoni S., Liu Z., Correia A., Martins J. P., Rahikkala A., Fontana F., Kemell M., Liu D., Albertini B., Passerini N., Li W., Santos H. A., pH and reactive oxygen species-sequential responsive nano-in-micro composite for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1806175 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee Y., Sugihara K., Gillilland M. G. III, Jon S., Kamada N., Moon J. J., Hyaluronic acid-bilirubin nanomedicine for targeted modulation of dysregulated intestinal barrier, microbiome and immune responses in colitis. Nat. Mater. 19, 118–126 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi C., Dawulieti J., Shi F., Yang C., Qin Q., Shi T., Wang L., Hu H., Sun M., Ren L., Chen F., Zhao Y., Liu F., Li M., Mu L., Liu D., Shao D., Leong K. W., She J., A nanoparticulate dual scavenger for targeted therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj2372 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong D., Zhang D., Chen W., He J., Ren C., Zhang X., Kong N., Tao W., Zhou M., Orally deliverable strategy based on microalgal biomass for intestinal disease treatment. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi9265 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian T., Wang Z., Zhang J., Pathomechanisms of oxidative stress in inflammatory bowel disease and potential antioxidant therapies. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 4535194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourgonje A. R., Feelisch M., Faber K. N., Pasch A., Dijkstra G., van Goor H., Oxidative stress and redox-modulating therapeutics in inflammatory bowel disease. Trends Mol. Med. 26, 1034–1046 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banan A., Choudhary S., Zhang Y., Fields J. Z., Keshavarzian A., Ethanol-induced barrier dysfunction and its prevention by growth factors in human intestinal monolayers: Evidence for oxidative and cytoskeletal mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 291, 1075–1085 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao R., Baker R. D., Baker S. S., Inhibition of oxidant-induced barrier disruption and protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Caco-2 cell monolayers by epidermal growth factor. Biochem. Pharmacol. 57, 685–695 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu T., Zhang L., Joo D., Sun S.-C., NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2, 17023 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knutson C. G., Mangerich A., Zeng Y., Raczynski A. R., Liberman R. G., Kang P., Ye W., Prestwich E. G., Lu K., Wishnok J. S., Korzenik J. R., Wogan G. N., Fox J. G., Dedon P. C., Tannenbaum S. R., Chemical and cytokine features of innate immunity characterize serum and tissue profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2332–E2341 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomasello G., Mazzola M., Leone A., Sinagra E., Zummo G., Farina F., Damiani P., Cappello F., Gerges Geagea A., Jurjus A., Assi T. B., Messina M., Carini F., Nutrition, oxidative stress and intestinal dysbiosis: Influence of diet on gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky Olomouc Czech. Repub. 160, 461–466 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y., Chen D., Zheng P., Yu J., He J., Mao X., Yu B., The bidirectional interactions between resveratrol and gut microbiota: An insight into oxidative stress and inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 5403761 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y., He X., Yin J. J., Ma Y., Zhang P., Li J., Ding Y., Zhang J., Zhao Y., Chai Z., Zhang Z., Acquired superoxide-scavenging ability of ceria nanoparticles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 127, 1852–1855 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jena G., Trivedi P. P., Sandala B., Oxidative stress in ulcerative colitis: An old concept but a new concern. Free Radic. Res. 46, 1339–1345 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen L., You Q., Hu L., Gao J., Meng Q., Liu W., Wu X., Xu Q., The antioxidant procyanidin reduces reactive oxygen species signaling in macrophages and ameliorates experimental colitis in mice. Front. Immunol. 8, 1910 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan W.-L., Tian B., Lin Y.-J., Korupalli C., Lu M.-Y., Cui Q., Wan D., Chang Y., Sung H.-W., Photosynthesis-inspired H2 generation using a chlorophyll-loaded liposomal nanoplatform to detect and scavenge excess ROS. Nat. Commun. 11, 534 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao P., Xia X., Xu X., Leung K. K. C., Rai A., Deng Y., Yang B., Lai H., Peng X., Shi P., Zhang H., Chiu P. W. Y., Bian L., Nanoparticle-assembled bioadhesive coacervate coating with prolonged gastrointestinal retention for inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Nat. Commun. 12, 7162 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao Y., Tang Z., Wang J., Liu C., Kong N., Farokhzad O. C., Tao W., Oral insulin delivery platforms: Strategies to address the biological barriers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 19787–19795 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen K., Zhu Y., Zhang Y., Hamza T., Yu H., Saint Fleur A., Galen J., Yang Z., Feng H., A probiotic yeast-based immunotherapy against Clostridioides difficile infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eaax4905 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y., Li C.-X., Zhang X.-Z., Bacteriophage-mediated modulation of microbiota for diseases treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 176, 113856 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caruso R., Lo B. C., Núñez G., Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 411–426 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z., Wang Y., Ding Y., Repp L., Kwon G. S., Hu Q., Cell-based delivery systems: Emerging carriers for immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100088 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin S., Mukherjee S., Li J., Hou W., Pan C., Liu J., Mucosal immunity–mediated modulation of the gut microbiome by oral delivery of probiotics into Peyer’s patches. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf0677 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan C., Li J., Hou W., Lin S., Wang L., Pang Y., Wang Y., Liu J., Polymerization-mediated multifunctionalization of living cells for enhanced cell-based therapy. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007379 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J., Li W., Wang Y., Ding Y., Lee A., Hu Q., Biomaterials coating for on-demand bacteria delivery: Selective release, adhesion, and detachment. Nano Today 41, 101291 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z., Wang Y., Liu J., Rawding P., Bu J., Hong S., Hu Q., Chemically and biologically engineered bacteria-based delivery systems for emerging diagnosis and advanced therapy. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102580 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anselmo A. C., McHugh K. J., Webster J., Langer R., Jaklenec A., Layer-by-layer encapsulation of probiotics for delivery to the microbiome. Adv. Mater. 28, 9486–9490 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu K., Young I., Woodburn B. M., Huang Y., Anselmo A. C., Polymeric films for the encapsulation, storage, and tunable release of therapeutic microbes. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 1901643 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng H., Yang W., Zhou Z., Tian R., Lin L., Ma Y., Song J., Chen X., Targeted scavenging of extracellular ROS relieves suppressive immunogenic cell death. Nat. Commun. 11, 4951 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta M. K., Martin J. R., Werfel T. A., Shen T., Page J. M., Duvall C. L., Cell protective, ABC triblock polymer-based thermoresponsive hydrogels with ROS-triggered degradation and drug release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14896–14902 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vanderburgh J., Hill J. L., Gupta M. K., Kwakwa K. A., Wang S. K., Moyer K., Bedingfield S. K., Merkel A. R., d’Arcy R., Guelcher S. A., Rhoades J. A., Duvall C. L., Tuning ligand density to optimize pharmacokinetics of targeted nanoparticles for dual protection against tumor-induced bone destruction. ACS Nano 14, 311–327 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z., Hu Y., Fu Q., Liu Y., Wang J., Song J., Yang H., NIR/ROS-responsive black phosphorus QD vesicles as immunoadjuvant carrier for specific cancer photodynamic immunotherapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1905758 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo R., Lin M., Fu C., Zhang J., Chen Q., Zhang C., Shi J., Pu X., Dong L., Xu H., Ye N., Sun J., Lin D., Deng B., McDowell A., Fu S., Gao F., Calcium pectinate and hyaluronic acid modified lactoferrin nanoparticles loaded rhein with dual-targeting for ulcerative colitis treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 263, 117998 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Napoli A., Valentini M., Tirelli N., Müller M., Hubbell J. A., Oxidation-responsive polymeric vesicles. Nat. Mater. 3, 183–189 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong S., Kim J., Na Y. S., Park J., Kim S., Singha K., Im G. I., Han D. K., Kim W. J., Lee H., Poly(norepinephrine): Ultrasmooth material-independent surface chemistry and nanodepot for nitric oxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 9187–9191 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Y., Tang Z., Huang X., Joseph J., Chen W., Liu C., Zhou J., Kong N., Joshi N., Du J., Tao W., Glucose-responsive oral insulin delivery platform for one treatment a day in diabetes. Matter 4, 3269–3285 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J., Wang T., Kirtane A. R., Shi Y., Jones A., Moussa Z., Lopes A., Collins J., Tamang S. M., Hess K., Shakur R., Karandikar P., Lee J. S., Huang H.-W., Hayward A., Traverso G., Gastrointestinal synthetic epithelial linings. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabc0441 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y., Ai K., Lu L., Polydopamine and its derivative materials: Synthesis and promising applications in energy, environmental, and biomedical fields. Chem. Rev. 114, 5057–5115 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng D.-B., Zhang X.-H., Gao Y.-J., Ji L., Hou D., Wang Z., Xu W., Qiao Z.-Y., Wang H., Endogenous reactive oxygen species-triggered morphology transformation for enhanced cooperative interaction with mitochondria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7235–7239 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Praveschotinunt P., Duraj-Thatte A. M., Gelfat I., Bahl F., Chou D. B., Joshi N. S., Engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 for the delivery of matrix-tethered therapeutic domains to the gut. Nat. Commun. 10, 5580 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou J., Li M., Chen Q., Li X., Chen L., Dong Z., Zhu W., Yang Y., Liu Z., Chen Q., Programmable probiotics modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment after effective oral delivery. Nat. Commun. 13, 3432 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rong Z. J., Cai H. H., Wang H., Liu G. H., Zhang Z. W., Chen M., Huang Y. L., Ursolic acid ameliorates spinal cord injury in mice by regulating gut microbiota and metabolic changes. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 872935 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu H.-Z., Liang Y.-D., Ma Q.-Y., Hao W.-Z., Li X.-J., Wu M.-S., Deng L.-J., Li Y.-M., Chen J.-X., Xiaoyaosan improves depressive-like behavior in rats with chronic immobilization stress through modulation of the gut microbiota. Biomed. Pharmacother. 112, 108621 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Q., Yu H., Xiao X., Hu L., Xin F., Yu X., Inulin-type fructan improves diabetic phenotype and gut microbiota profiles in rats. PeerJ 6, e4446 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massip C., Branchu P., Bossuet-Greif N., Chagneau C. V., Gaillard D., Martin P., Boury M., Secher T., Dubois D., Nougayrède J.-P., Oswald E., Deciphering the interplay between the genotoxic and probiotic activities of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. PLOS Pathog. 15, e1008029 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials