Abstract

Masitinib is an orally acceptable tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is currently investigated under clinical trials against cancer, asthma, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A recent study confirmed the anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) activity of masitinib through inhibition of the main protease (Mpro) enzyme, an important pharmacological drug target to block the replication of the coronavirus. However, due to the adverse effects and lower potency of the drug, there are opportunities to design better analogues of masitinib. Herein, we substituted the N-methylpiperazine group of Masitinib with different chemical moieties and evaluated their drug-likeness and toxicities. The filtered analogues were subjected to molecular docking studies which revealed that the analogues with substituents methylamine in M10 (CID10409602), morpholine in M23 (CID59789397) and 4-methylmorpholine in M32 (CID143003625) have a stronger affinity to the drug receptor compared to masitinib. The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analysis reveals that the identified analogues alter the mobility, structural compactness, accessibility to solvent molecules, and the number of hydrogen bonds in the native target enzyme. These structural alterations can help explain the inhibitory mechanisms of these analogues against the target enzyme. Thus, our studies provide avenues for the design of new masitinib analogues as the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors.

Keywords: Masitinib, Masitinib analogues, N-methylpiperazine, SARS-CoV-2, Main protease inhibitors, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Molecular dynamics simulations

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted global attempts to identify vaccines and specialized antiviral therapies as early as possible (Li and De Clercq, 2020, Zhang et al., 2020a). The main protease (Mpro, 3CLpro, nsp5) attracted a lot of interest among the coronaviral targets that have been investigated in the past, especially during the initial severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak in early 2003 (Anand et al., 2003, Yang et al., 2003). Spike protein (S), RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp, nsp12), NTPase/helicase (nsp13), and papain-like protease are other potential coronaviral targets (Hilgenfeld and Peiris, 2013, Wu et al., 2020a). The pp1a and pp1ab polyproteins encoded by the viral replicase gene are made up of distinct viral proteins that are required for replication (Wu et al., 2020b, Zhou et al., 2020). The processing of each polyprotein into distinct functional proteins is mediated by a chymotrypsin-like protease, 3CL Mpro or main protease (Mandal et al., 2021). The Mpro is necessary for viral replication, and its suppression prevents the production of mature virions (Ullrich and Nitsche, 2020). Therefore, the enzyme is an important target for the development of anti-SARS–CoV-2 therapeutic drugs (Jin et al., 2020, Mengist et al., 2021, Riva et al., 2020). SARS–CoV-2 Mpro is a cysteine protease that functions as a homodimer (Tong, 2002). It has a 96 percent amino acid sequence identity to the earlier SARS–CoV Mpro, and both enzymes have similar catalytic efficiency (Jin et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020b). The enzyme possesses three catalytic domains I, II and III (Zhang et al., 2020b) with the Cys145–His41 dyad in the catalytic site being aided by a water molecule hydrogen-bonded to the catalytic histidine (Anand et al., 2003, Kneller et al., 2020). The enzyme recognizes the sequence Leu-Gln↓Ser-Ala-Gly, where ↓ is the cleavage site but is promiscuous in its substrate sequence recognition. The active-site cavity can bind substrate residues at positions P1′-P5 in the substrate-binding subsites S1′–S5 (Kneller et al., 2020).

Masitinib is an orally accessible c-kit inhibitor (Dubreuil et al., 2009) that has been licensed for the treatment of mast cell malignancies in dogs (Hahn et al., 2008) and is being tested in humans for cancer (Ottaiano et al., 2017), asthma (Humbert et al., 2009), Alzheimer's disease (Folch et al., 2015), multiple sclerosis (Vermersch et al., 2012), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Mora et al., 2020). Through disruption of the stem cell factor, mast cell c-Kit pathway, masitinib has direct antiproliferative effects on mast cells. Masitinib is a phenyl aminothiazole derivative that inhibits c-Kit as well as platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFR) α and β (Dubreuil et al., 2009, Le Cesne et al., 2010). Masitinib is also an inhibitor of the ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 10 (ABCC10) and ATP-binding cassette transporter G2 (ABCG2) transporters which substantially enhances paclitaxel intracellular accumulation in vitro (Kathawala et al., 2014a, Kathawala et al., 2014b) and furthermore, systemic administration of masitinib in combination with paclitaxel to mice inhibits the growth of xenografted tumors overexpressing the ABCC10 transporter (Kathawala et al., 2014b). Masitinib has also been shown to revert multi-drug resistance (MDR) in drug-resistant cancer cells to a normal condition. This process decreased doxorubicin drug resistance in canine cancer cells in vitro, but clinical trials have yet to validate it (Papich, 2016).

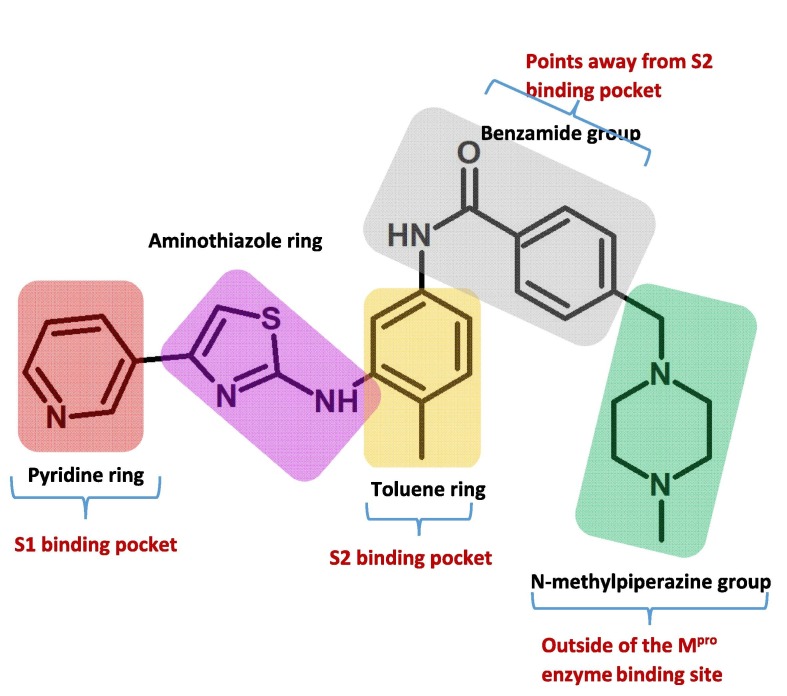

A recent study reported that Masitinib acts as a competitive inhibitor of Mpro as well and administration of masitinib to mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 shows a 200-fold decrease in viral titers in the lungs and nose, as well as reduced lung inflammation. Interestingly, this inhibitor was also effective against all of the identified variations of concern in vitro such as alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), and gamma (P.1) (Drayman et al., 2021). According to the X-ray crystallography study (PDB ID: 7JU7), Masitinib binds noncovalently between domains I and II of Mpro and inhibits the essential catalytic residues at the two active sites in the dimer. Mastinib has five distinct moieties: a pyridine ring, an aminothiazole ring, a toluene ring, a benzamide group, and an N-methylpiperzine group (Fig. 1 ). While the first four groups of Masitinib are involved in van der Waals, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond interactions with the protease's catalytic residues, the role of the N-methylpiperazine group is unclear because it was discovered to be disordered and outside of the protease binding site. Given Masitinib's adverse effects, this study aims to replace the inhibitor's N-methylpiperazine group with other chemical moieties and investigate their toxicity using in silico techniques and their binding to Mpro using a molecular docking and dynamics approach. The key analogues proposed in this work are expected to have enhanced Mpro inhibitory activity with minimal adverse effects.

Fig. 1.

Mastinib's chemical structure reveals five unique moieties: a pyridine ring, an aminothiazole ring, a toluene ring, a benzamide group, and an N-methylpiperzine group, all of which occupy different locations in the SARS-CoV-2 main protease enzyme, as shown by X-ray crystallography (PDB ID:7JU7).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Retrieval of structural analogues of masitinib

The structural analogues of masitinib with the N-methylpiperazine group replaced were retrieved from the PubChem database (Kim et al., 2016). The chemical structures of the analogues were downloaded in SDF format. The structures were optimized using the Merck molecular force field 94 (MMFF94) force field (Halgren, 1996) following steepest descent algorithm.

2.2. Physicochemical characteristics of the analogues

Lipinski's rule of five (ROF) (Lipinski, 2004), Veber's rule (Veber et al., 2002) filters and in silico toxicity tests such as mutagenicity, tumorigenicity, reproductive effects and irritancy were used to screen the analogues for drug-like qualities. The physicochemical features of the analogues were determined using the DataWarrior programme version 4.6.1 (Sander et al., 2015).

2.3. Retrieval of target protein structure

The atomic coordinates of the target enzyme the SARS-CoV-2 main protease were acquired from the protein data bank (PDB) (PDB ID: 7JU7). The X-ray crystal structure of the target enzyme complexed with masitinib has been determined at a resolution of 1.60 Å (Drayman et al., 2021).

2.4. Preparation of the analogues and target enzyme

Using AutoDock Tools-1.5.6, each analogue molecule was prepared for molecular docking by adding Gasteiger charges and hydrogen atoms, as well as appropriately determined torsions. The heteroatoms were removed from the target enzyme, which included ions, co-crystallized ligands, and water molecules. The requisite amount of polar hydrogen atoms and Kolmann charges were added to the target enzyme using the AutoDock Tools-1.5.6 tool.

2.5. Molecular docking studies

The Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used for molecular docking experiments, with docking parameters chosen from our previous publication (Gurung et al., 2020). For molecular docking, the AutoDock4.2 programme was utilised (Morris et al., 2009). A grid box with XYZ coordinates of 9.498, 4.128 and 20.681, a number of grid points of 70 × 70 × 70, and grid spacing of 0.375 was chosen to determine the binding site of the analogues. Using a 2.0 root mean square deviation (RMSD) cut-off value, the docking positions were conformationally grouped. The LigPlot+ v 1.4.5 program was used to analyse the molecular interactions between analogues and the target enzyme (Laskowski and Swindells, 2011).

2.6. Molecular dynamics

The molecular docked protein–ligand complex structures were employed in GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations (GROMACS) 2019.2 software (Hess et al., 2008) with GROMOS96 43a1 force field to run MD simulations. The topologies for Mpro were built using the pdb2gmx utility included in GROMACS, while the ligand parameters were obtained using the PRODRG web server (Schüttelkopf and Van Aalten, 2004). All the systems were centred in a triclinic box with a box-system distance of 1.0 nm and solvated with TIP3P water. 0.15 M NaCl was introduced to the Mpro system to neutralize the charge. The systems were then relaxed using the steepest descent method with 50,000 steps for energy minimization calculations at a tolerance value of 1000 kJ/mol/nm). The systems were then heated to 300 K using a Berendsen thermostat (Berendsen et al., 1984) with a coupling time of 0.1 ps, and the pressure was maintained with a coupling to a reference pressure of 1 bar, followed by equilibration with position restraint on the protein and ligand molecules for 0.1 ns using NVT (Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensembles. A smooth force-switch 1.2 nm cutoff was used in short-range interactions for energy minimization, NVT, and NPT relaxation simulations, and long-range electrostatics were evaluated using the PME (Particle-Mesh-Ewald) (Darden et al., 1993); additionally, hydrogen-bonds were restrained with the LINCS algorithm (Hess et al., 1997). Final MD simulations of 100 ns were run without constraints with a 2-fs integration time-step, and 1 ps trajectory snapshots were taken.

3. Results

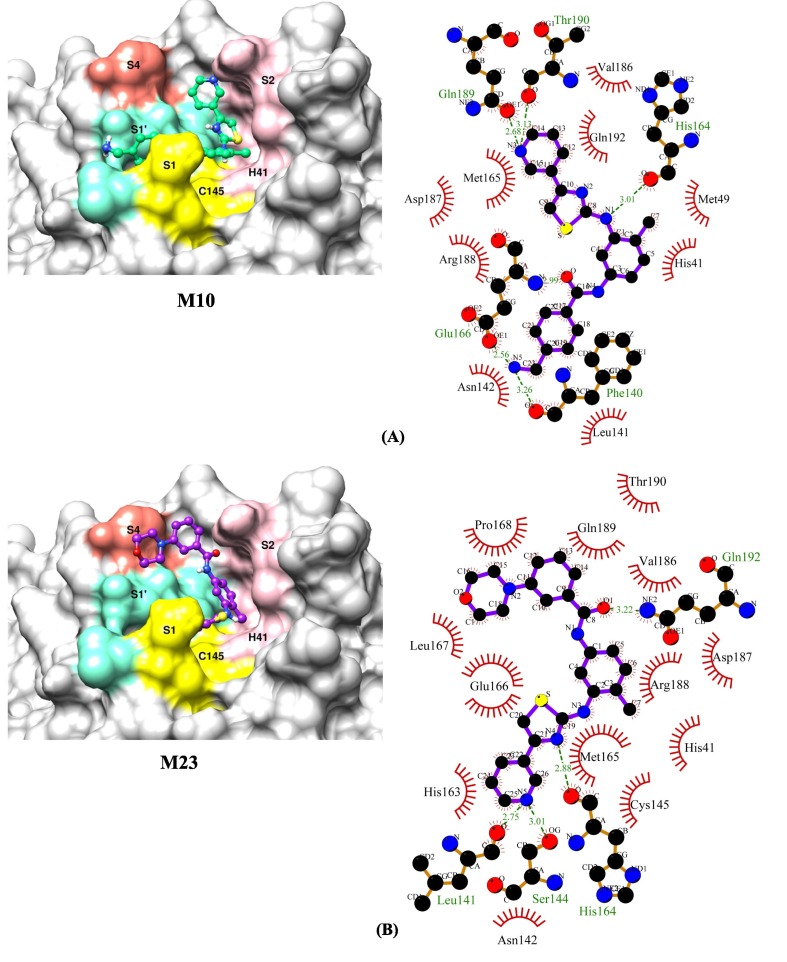

We found thirty-nine structural analogues of masitinib, using a sub-structure search methodology against the PubChem database. Following that, drug-like filters such as ROF, veber's rule, and toxicity filters were applied to these hits. A total of 18 analogues out of 39 were chosen for molecular docking experiments because they have the most favourable drug-like characteristics (Table 1 ). The analogue M10 binds to the SARS-CoV-2 main protease enzyme with a binding energy of −10.50 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 19.98 nM (Table 2 ) and exhibits five hydrogen bonds with Phe140, His164, Glu166, Gln189 and Thr190, and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Leu141, Asn142, Met165, Val186, Asp187, Arg188 and Gln192 (Fig. 2 A). The analogue M23 binds to the target enzyme with a binding energy of −10.10 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 39.26 nM (Table 2) and shows four hydrogen bonds with Leu141, Ser144, His164 and Gln192 and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Asn142, Cys145, His163, Met165, Glu166, Leu167, Pro168, Val186, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 and Thr190 (Fig. 2 B). The analogue M32 binds to the protease enzyme with a binding energy of −9.94 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 51.70 nM (Table 2) and shows three hydrogen bonds with His164, Glu166 and Thr190 and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, Met165, Asp187, Arg188, Gln189 and Gln192 (Fig. 2 C). Masitinib shows binding energy of −9.72 kcal/mol and inhibition constant of 74.64 nM (Table 2). The compound forms two hydrogen bonds with Glu166 and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Phe140, Leu141, Asn142, His164, Met165, Val186, Asp187, Arg188, Thr190 and Gln192 (Fig. 2 D).

Table 1.

Drug-like properties of Masitinib and its analogues. The presence of an asterisk next to a molecule shows that it has passed drug-like filters and in silico toxicity assessments.

| Compounds | PubChem CID | MW | cLogP | HBA | HBD | TPSA | RB | Druglikeness | Mutagenic | Tumorigenic | Reproductive Effective | Irritant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 10,023,927 | 400.505 | 5.3999 | 5 | 2 | 95.15 | 5 | 2.5987 | none | none | none | none |

| M2* | 10,074,640 | 498.653 | 4.7573 | 7 | 2 | 101.63 | 7 | 9.496 | none | none | none | none |

| M3* | 10,096,852 | 484.626 | 4.8344 | 7 | 2 | 101.63 | 6 | 8.6973 | none | none | none | none |

| M4* | 10,254,812 | 485.61 | 4.6479 | 7 | 2 | 107.62 | 7 | 3.8984 | none | none | none | none |

| M5 | 10,319,726 | 416.504 | 4.4587 | 6 | 3 | 115.38 | 6 | 2.5237 | none | low | none | none |

| M6* | 10,319,727 | 416.504 | 4.986 | 6 | 2 | 104.38 | 6 | 2.6285 | none | none | none | none |

| M7 | 10,341,171 | 404.468 | 5.1568 | 5 | 2 | 95.15 | 5 | 1.2587 | none | none | none | none |

| M8 | 10,364,308 | 411.488 | 4.8916 | 6 | 2 | 118.94 | 5 | −1.6813 | none | none | none | none |

| M9 | 10,409,364 | 411.488 | 4.8916 | 6 | 2 | 118.94 | 5 | −1.6813 | none | none | none | none |

| M10* | 10,409,602 | 415.52 | 4.0609 | 6 | 3 | 121.17 | 6 | 2.4492 | none | none | none | none |

| M11 | 10,410,432 | 430.487 | 5.1674 | 7 | 2 | 113.61 | 5 | 2.5304 | none | none | none | none |

| M12 | 10,412,398 | 469.611 | 5.4699 | 6 | 2 | 98.39 | 7 | 4.6983 | none | none | none | none |

| M13* | 10,453,738 | 402.477 | 4.7103 | 6 | 3 | 115.38 | 5 | 2.6065 | none | none | none | none |

| M14* | 10,476,173 | 401.493 | 4.3787 | 6 | 3 | 121.17 | 5 | 2.5785 | none | none | none | none |

| M15 | 11,743,384 | 429.547 | 4.9524 | 6 | 2 | 98.39 | 6 | 3.4511 | none | high | none | none |

| M16 | 42,613,483 | 471.54 | 4.3559 | 8 | 4 | 144.48 | 7 | 1.3641 | none | none | none | none |

| M17* | 42,625,974 | 444.514 | 4.969 | 7 | 2 | 121.45 | 7 | 0.27312 | none | none | none | none |

| M18* | 42,625,975 | 430.487 | 4.3707 | 7 | 3 | 132.45 | 6 | 2.5024 | none | none | none | none |

| M19 | 42,626,345 | 445.502 | 4.0267 | 8 | 4 | 144.48 | 6 | 2.5065 | high | none | none | none |

| M20 | 59,325,802 | 386.478 | 5.056 | 5 | 2 | 95.15 | 5 | 2.5987 | none | none | none | none |

| M21* | 59,651,299 | 429.547 | 4.4124 | 6 | 3 | 107.18 | 7 | 3.5815 | none | none | none | none |

| M22* | 59,789,379 | 429.547 | 4.9524 | 6 | 2 | 98.39 | 6 | 3.4511 | none | none | none | none |

| M23* | 59,789,397 | 471.583 | 4.725 | 7 | 2 | 107.62 | 6 | 3.6783 | none | none | none | none |

| M24 | 59,789,404 | 444.558 | 5.1733 | 6 | 2 | 104.38 | 7 | 2.933 | none | none | none | none |

| M25 | 74,821,251 | 471.54 | 4.3559 | 8 | 4 | 144.48 | 7 | 1.3641 | none | none | none | none |

| M26 | 87,619,315 | 445.502 | 3.7976 | 8 | 4 | 158.47 | 6 | 3.0505 | none | none | none | none |

| M27 | 91,443,299 | 400.505 | 5.3999 | 5 | 2 | 95.15 | 5 | 2.5987 | none | none | none | none |

| M28 | 130,324,311 | 484.626 | 4.5044 | 7 | 3 | 110.42 | 7 | 5.0512 | none | none | none | low |

| M29 | 140,528,385 | 459.529 | 4.074 | 8 | 4 | 144.48 | 7 | 3.2401 | low | low | low | high |

| M30* | 142,960,381 | 402.501 | 2.4009 | 6 | 4 | 122.42 | 5 | 2.4276 | none | none | none | none |

| M31 | 142,964,721 | 415.52 | 4.703 | 6 | 3 | 107.18 | 6 | 3.0571 | none | high | none | none |

| M32* | 143,003,625 | 486.618 | 4.2939 | 7 | 2 | 112.2 | 7 | 3.6141 | none | none | none | none |

| M33 | 144,600,411 | 400.505 | 5.3999 | 5 | 2 | 95.15 | 5 | 2.5987 | none | none | none | none |

| M34 | 147,174,347 | 427.531 | 5.1157 | 6 | 2 | 107.51 | 6 | 3.2238 | none | none | none | none |

| M35* | 147,675,008 | 441.558 | 4.5218 | 6 | 3 | 107.18 | 5 | 2.9845 | none | none | none | none |

| M36 | 149,779,171 | 485.531 | 5.2177 | 11 | 4 | 162.24 | 6 | 2.6318 | none | none | none | none |

| M37* | 151,845,207 | 415.52 | 4.0609 | 6 | 3 | 121.17 | 6 | 2.4492 | none | none | none | none |

| M38* | 152,130,115 | 483.595 | 4.9037 | 7 | 2 | 115.46 | 7 | 4.8315 | none | none | none | none |

| M39* | 154,499,650 | 429.503 | 4.1433 | 7 | 3 | 138.24 | 6 | 3.0372 | none | none | none | none |

| Masitinib* | 10,074,640 | 498.653 | 4.7573 | 7 | 2 | 101.63 | 7 | 9.496 | none | none | none | none |

Table 2.

Binding energy and inhibition constant of masitinib and its analogues when docked against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) enzyme with an asterisk indicating the top three analogues.

| Compounds | IUPAC Name | PubChem CID | Structure | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Inhibition constant (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3 | 4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,096,852 |  |

−8.93 | 285.58 |

| M4 | N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]-4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)benzamide | 10,254,812 |  |

−9.50 | 108.40 |

| M6 | 3-methoxy-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,319,727 |  |

−9.61 | 90.87 |

| M10* | 4-(aminomethyl)-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,409,602 |  |

−10.50 | 19.98 |

| M13 | 4-hydroxy-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,453,738 |  |

−9.03 | 241.50 |

| M14 | 4-amino-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,476,173 |  |

−8.80 | 351.81 |

| M17 | methyl 4-[[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]carbamoyl]benzoate | 42,625,974 |  |

−9.39 | 130.88 |

| M18 | 4-[[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]carbamoyl]benzoic acid | 42,625,975 |  |

−9.16 | 192.99 |

| M21 | 4-(methylaminomethyl)-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 59,651,299 |  |

−9.75 | 71.32 |

| M22 | 3-(dimethylamino)-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 59,789,379 |  |

−9.53 | 102.81 |

| M23* | N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]-3-morpholin-4-ylbenzamide | 59,789,397 |  |

−10.10 | 39.26 |

| M30 | 4-amino-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-1-ium-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 142,960,381 |  |

−8.55 | 539.20 |

| M32* | [2-methyl-5-[[4-(morpholin-4-ylmethyl)benzoyl]amino]phenyl]-(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)azanium | 143,003,625 |  |

−9.94 | 51.70 |

| M35 | N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-7-carboxamide | 147,675,008 |  |

−9.78 | 68.23 |

| M37 | 2-(aminomethyl)-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 151,845,207 |  |

−9.55 | 99.37 |

| M38 | N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]-4-[(2-oxopyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl]benzamide | 152,130,115 |  |

−9.13 | 203.85 |

| M39 | 4-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzene-1,4-dicarboxamide | 154,499,650 |  |

−9.81 | 64.85 |

| Masitinib | 4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-yl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide | 10,074,640 |  |

−9.72 | 74.64 |

Fig. 2.

The binding orientations and molecular interactions between SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme and compounds (A) M10 (B) M23 (C) M32 and (D) Masitinib. Compounds in the active site pocket of the enzyme with catalytic dyad (His41 and Cys145) and substrate binding subsites-S1, S1′, S2 and S4 are shown in the binding models on the left side panel. The right-hand panel displays the LigPlot + program's molecular interaction data, with hydrophobic interactions depicted as semi-arcs with red eyelashes and hydrogen bonds depicted as green dashed lines.

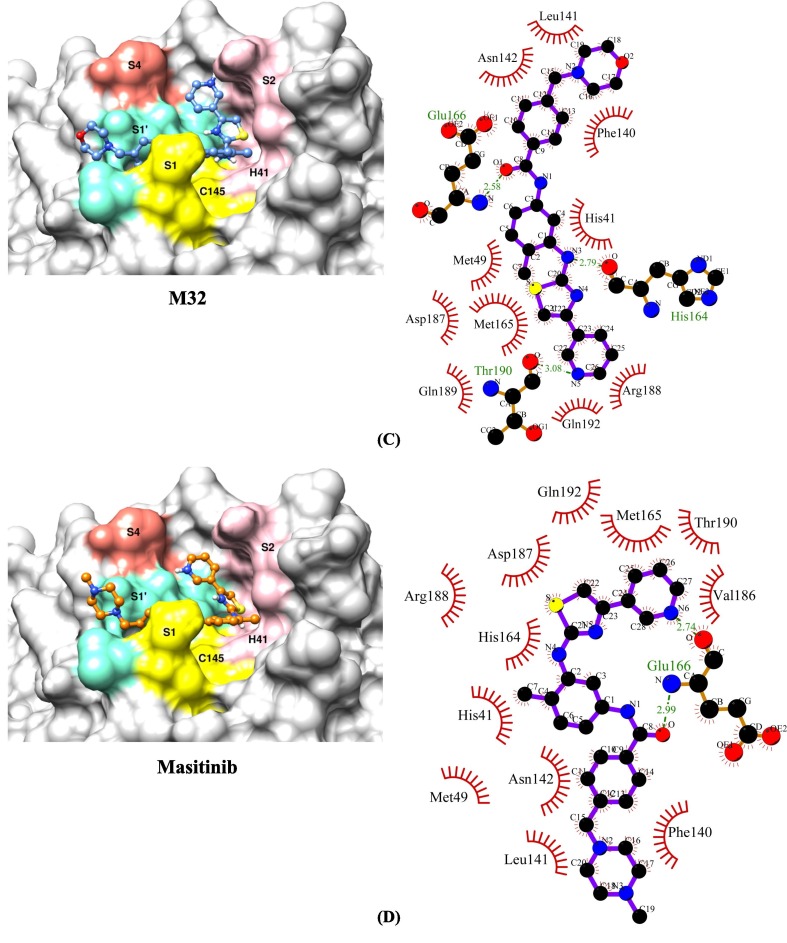

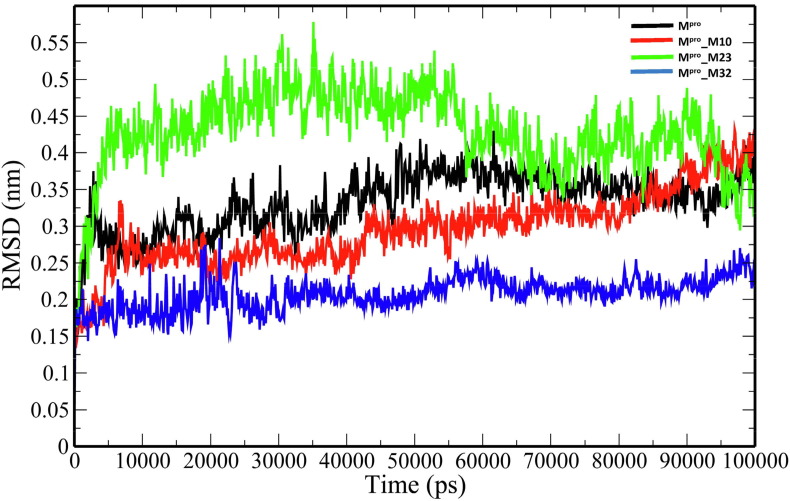

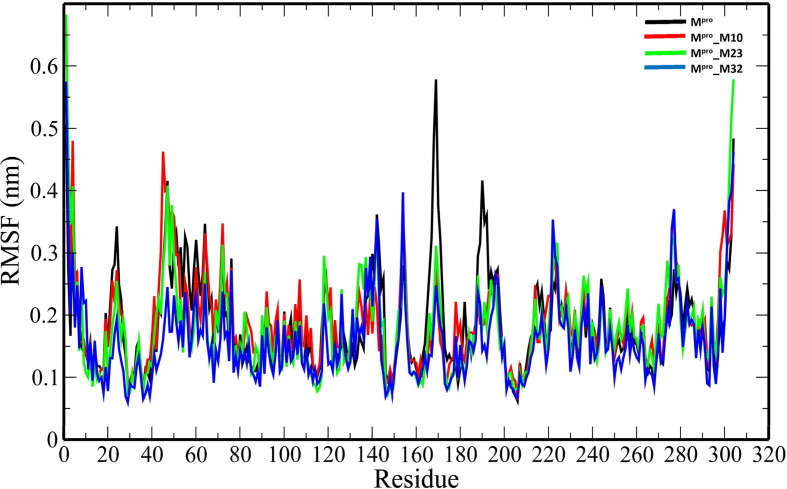

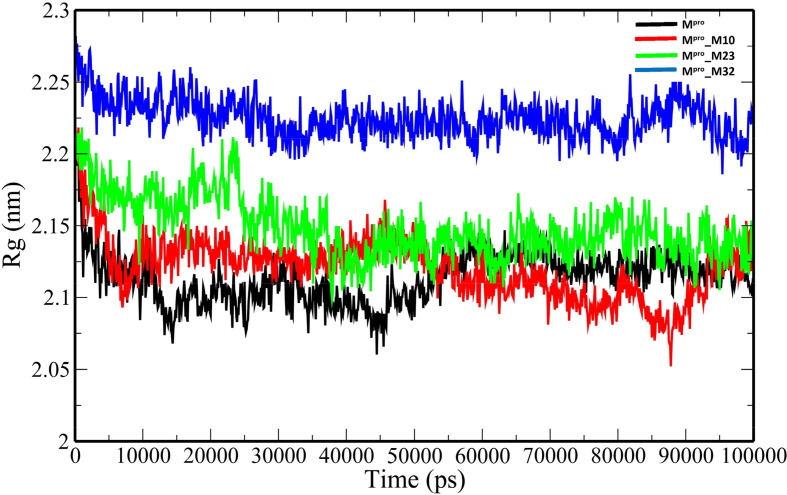

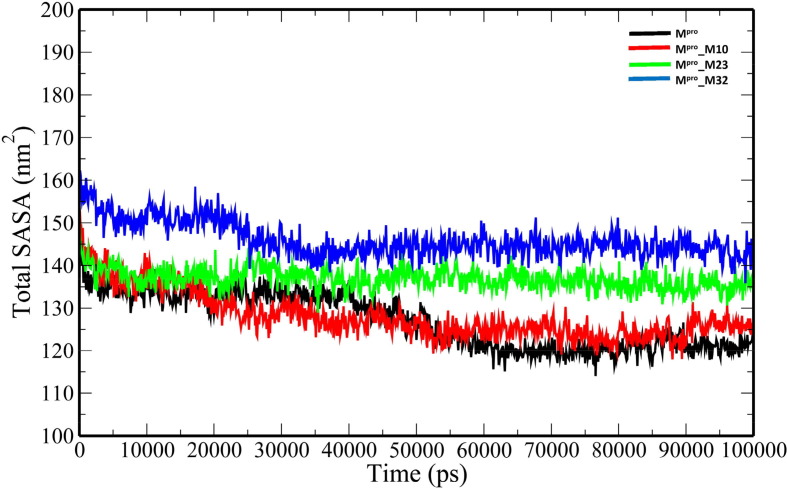

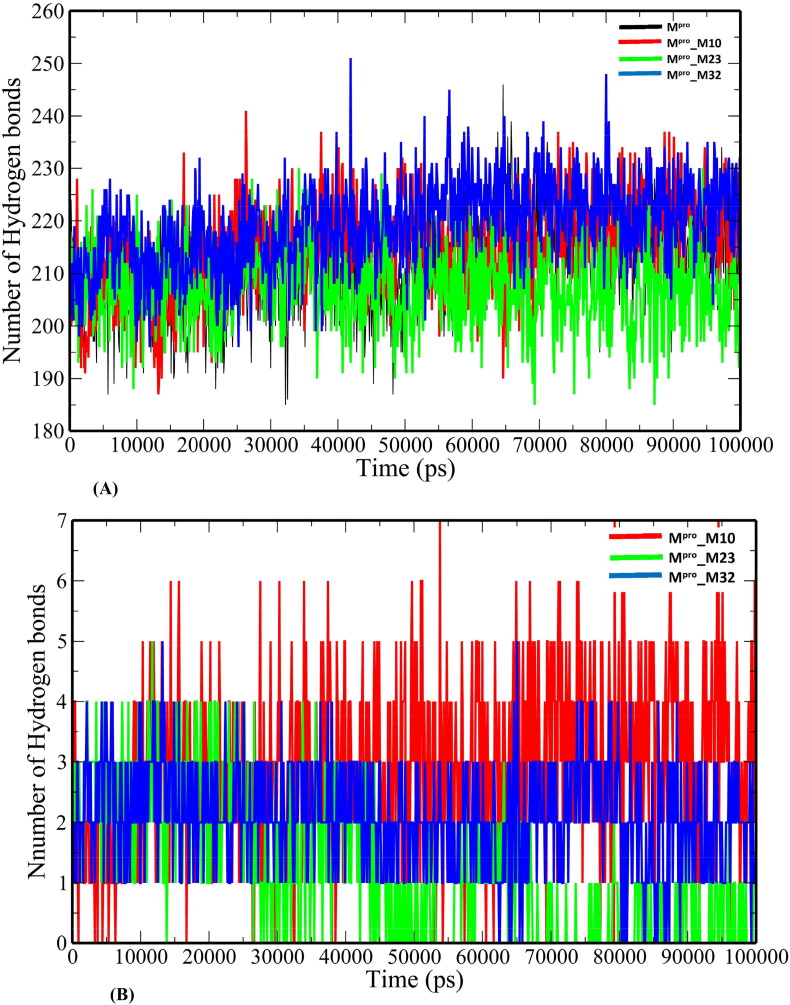

The unbound Mpro and complexes of the top 3 ranked analogues- M10, M23 and M32 were taken further for 100-ns MD simulations to understand the changes in structural properties (Table 3 ) of the target enzyme. Mpro, Mpro_M10, Mpro_M23 and Mpro_32 complexes have an average root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.332583731 ± 0.041627085 nm, 0.295749208 ± 0.051314569 nm, 0.429039348 ± 0.05700657 nm and 0.207552255 ± 0.022640365 nm respectively (Table 3). The binding of the analogues decreases the flexibility of the target enzyme except for M23 (Fig. 3 ). The average RMSD values of M10, M23 and M32 were 0.314784896 ± 0.058489328 nm, 0.710852126 ± 0.203861157 nm and 0.27076158 ± 0.065500399 nm. The root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) plot was generated to evaluate the residue-wise fluctuations in the target enzyme before and after the binding of the analogues. (Fig. 4 ). The radius of gyration (Rg) of unbound Mpro and Mpro- analogue complexes was plotted to explore their structural compactness (Fig. 5 ). The Rg values for Mpro, Mpro_M10 Mpro_M23 and Mpro_32 complexes were 2.127997 ± 0.017467845 nm, 2.120922877 ± 0.021329819 nm, 2.148384565 ± 0.021399429 nm and 2.225106244 ± 0.013538302 nm respectively. The Rg plot suggests that the analogues induce conformational changes in Mpro leading to decreased structural compactness except for M10. The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) analysis for unbound Mpro and Mpro docked complexes was performed (Fig. 6 ). The average SASA values for Mpro, Mpro_M10 Mpro_M23 and Mpro_M32 complexes were determined to be 127.0979391 ± 6.538834755 nm2, 128.082026 ± 5.499573972 nm2, 136.912978 ± 2.469146035 nm2 and 146.066041 ± 4.0438426 nm2 respectively. The formation of hydrogen bonds during the simulation were computed for unbound Mpro and Mpro docked complexes (Fig. 7 A). Mpro, Mpro_M10 Mpro_M23 and Mpro_M32 complexes exhibit an average number of intramolecular hydrogen bonds of 211.5834166 ± 9.206371963, 214.5474525 ± 8.729604573, 207.3446553 ± 7.46713425 and 219.1978022 ± 8.291009297 respectively. The number of hydrogen bonds formed between the target enzyme and analogues was 2.934065934 ± 1.31516096, 1.23976024 ± 1.145625394 and 2.094905095 ± 0.839037553 for M10, M23 and M32 respectively (Fig. 7 B).

Table 3.

Average structural properties of unbound SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and Mpro-analogue docked complexes.

| Systems | RMSD (nm) | Rg (nm) | SASA (nm2) | Hydrogen bonds | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Ligand | Protein | Ligand | |||

| Mpro | 0.332583731± 0.041627085 |

2.127997± 0.017467845 |

127.0979391± 6.538834755 |

211.5834166± 9.206371963 |

||

| Mpro_M10 | 0.295749208± 0.051314569 |

0.314784896 ± 0.058489328 | 2.120922877 ± 0.021329819 | 128.082026 ± 5.499573972 | 214.5474525 ± 8.729604573 | 2.934065934 ± 1.31516096 |

| Mpro_M23 | 0.429039348 ± 0.05700657 | 0.710852126 ± 0.203861157 | 2.148384565 ± 0.021399429 | 136.912978 ± 2.469146035 | 207.3446553 ± 7.46713425 | 1.23976024 ± 1.145625394 |

| Mpro_M32 | 0.207552255 ± 0.022640365 | 0.27076158 ± 0.065500399 | 2.225106244 ± 0.013538302 | 146.066041 ± 4.0438426 | 219.1978022 ± 8.291009297 | 2.094905095 ± 0.839037553 |

Fig. 3.

The RMSD plot of backbone atoms of the unbound Mpro and Mpro-analogue complexes.

Fig. 4.

The RMSF plot of backbone atoms of the unbound Mpro and Mpro-analogue complexes.

Fig. 5.

The plot of Rg of the unbound Mpro and Mpro-analogue complexes.

Fig. 6.

The total SASA plot of the unbound Mpro and Mpro-analogue complexes.

Fig. 7.

The plot of number of hydrogen bonds versus time (A) intramolecular hydrogen bonds (B) intermolecular hydrogen bonds between Mpro and masitinib analogues.

4. Discussion

Here, we used an X-ray crystal structure of the main protease enzyme complexed with masitinib (PDB ID: 7JU7) for the structure-based identification of inhibitor analogues. Masitinib is an orally available c-kit inhibitor that has been approved in dogs for the treatment of mast cell malignancies (Dubreuil et al., 2009; Hahn et al., 2008) and is currently being evaluated in humans for Alzheimer's disease, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Hahn et al., 2008, Mora et al., 2020, Ottaiano et al., 2017, Vermersch et al., 2012). Masitinib works as a competitive inhibitor of Mpro, according to a recent study, and treatment of masitinib in mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 results in a 200-fold reduction in viral titers in the lungs and nose, as well as a reduction in lung inflammation. This inhibitor was likewise efficient in vitro against all of the reported variants of concern (B.1.1.7, B.1.351, and P.1) (Drayman et al., 2021). Given Masitinib's side effects, this research aims to substitute different chemical moieties for the inhibitor's N-methylpiperazine group and explore their toxicity using in silico approaches, as well as their binding to Mpro using a molecular docking and dynamics approach. A total of 18 analogues out of 39 have promising drug-like characteristics. The ability of the filtered drug-like analogues to bind and interact with the Mpro enzyme was investigated. The analogues M10 with methylamine moiety, M23 with morpholine substituent and M32 with 4-methylmorpholine group which were bound to the active-site pocket by hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, were selected as the best three analogues interacting with the target enzyme. Using MD simulations, the dynamic behaviour of the free Mpro enzyme and its complexes with analogues M10, M23, and M32 was investigated, and their stabilities were validated in terms of RMSD, Rg, SASA, and hydrogen bond number. Thus, the three analogues- M10, M23, and M32 not only have optimum drug-like qualities but also binds well to the target enzyme, indicating that they could be developed into SARS-CoV-2 drug candidates. It would also be fascinating to explore if these analogues can be developed into broad-spectrum inhibitors against the emerging coronavirus variants. While the preliminary findings are encouraging, the wet-lab experiments are required to establish the anti-SARS-CoV-2 effectiveness of the analogues.

5. Conclusion

The paucity of effective therapy, as well as the ongoing rise in fatality rates as new variants of SARS-CoV-2 arise, necessitating the discovery of innovative drug candidates. Using a combined technique of molecular docking and dynamics simulation, we studied the anti-SARS-CoV-2 potential of structural analogues of masitinib, an orally tolerable tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is now being investigated in clinical trials for numerous human disorders. We discovered three structural analogues-M10, M23 and M32 with significant binding affinities to the drug target enzyme SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Our study suggests that the substitution of N-methylpiperazine group of masitinib with methylamine, morpholine and 4-methylmorpholine moieties enhances the affinity toward the target enzyme. Our findings will help in understanding the structure–activity relationship of these analogues and further need to be validated through wet-lab experiments.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project no. (IFKSURG-2-286).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science (80-) 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen H.J.C., van Postma J.P.M., van Gunsteren W.F., DiNola A., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅ log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil P., Letard S., Ciufolini M., Gros L., Humbert M., Castéran N., Borge L., Hajem B., Lermet A., Sippl W., et al. Masitinib (AB1010), a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Petrov D., Ettcheto M., Pedros I., Abad S., Beas-Zarate C., Lazarowski A., Marin M., Olloquequi J., Auladell C., et al. Masitinib for the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015;15:587–596. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1045419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung A.B., Ali M.A., Lee J., Farah M.A., Al-Anazi K.M. Unravelling lead antiviral phytochemicals for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme through in silico approach. Life Sci. 2020;117831 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn K.A., Oglivie G., Rusk T., Devauchelle P., Leblanc A., Legendre A., Powers B., Leventhal P.S., Kinet J.-P., Palmerini F., et al. Masitinib is safe and effective for the treatment of canine mast cell tumors. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008;22:1301–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, form, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490–519. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199604)17:5/6<490::AID-JCC1>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H.J.C., Fraaije J.G.E.M. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Hess B., Kutzner C., Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E. GRGMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenfeld R., Peiris M. From SARS to MERS: 10 years of research on highly pathogenic human coronaviruses. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, M., De Blay, F., Garcia, G., Prud’homme, A., Leroyer, C., Magnan, A., Tunon-de-Lara, J.-M., Pison, C., Aubier, M., Charpin, D., others, 2009. Masitinib, ac-kit/PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, improves disease control in severe corticosteroid-dependent asthmatics. Allergy 64, 1194–1201. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., et al. Structure of M pro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathawala R.J., Chen J.-J., Zhang Y.-K., Wang Y.-J., Patel A., Wang D.-S., Talele T.T., Ashby C.R., Chen Z.-S. Masitinib antagonizes ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2-mediated multidrug resistance. Int. J. Oncol. 2014;44:1634–1642. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathawala R.J., Sodani K., Chen K., Patel A., Abuznait A.H., Anreddy N., Sun Y.-L., Kaddoumi A., Ashby C.R., Chen Z.-S. Masitinib antagonizes ATP-binding cassette subfamily C member 10–mediated Paclitaxel resistance: a preclinical study. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:714–723. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Thiessen P.A., Bolton E.E., Chen J., Fu G., Gindulyte A., Han L., He J., He S., Shoemaker B.A., Wang J., Yu B., Zhang J., Bryant S.H. PubChem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneller D.W., Phillips G., Weiss K.L., Pant S., Zhang Q., O’Neill H.M., Coates L., Kovalevsky A. Unusual zwitterionic catalytic site of SARS–CoV-2 main protease revealed by neutron crystallography. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295:17365–17373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.016154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. LigPlot+: multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cesne A., Blay J.-Y., Bui B.N., Bouché O., Adenis A., Domont J., Cioffi A., Ray-Coquard I., Lassau N., Bonvalot S., et al. Phase II study of oral masitinib mesilate in imatinib-naive patients with locally advanced or metastatic gastro-intestinal stromal tumour (GIST) Eur. J. Cancer. 2010;46:1344–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G., De Clercq E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today. Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal A., Jha A.K., Hazra B. Plant Products as Inhibitors of Coronavirus 3CL Protease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:167. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.583387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengist, H.M., Dilnessa, T., Jin, T., 2021. Structural basis of potential inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Front. Chem. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mora, J.S., Genge, A., Chio, A., Estol, C.J., Chaverri, D., Hernández, M., Mar\’\in, S., Mascias, J., Rodriguez, G.E., Povedano, M., others, 2020. Masitinib as an add-on therapy to riluzole in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized clinical trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 21, 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaiano A., Capozzi M., De Divitiis C., De Stefano A., Botti G., Avallone A., Tafuto S. Gemcitabine mono-therapy versus gemcitabine plus targeted therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized phase III trials. Acta Oncol. (Madr) 2017;56:377–383. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1288922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papich, M.G., 2016. Masitinib Mesylate, in: Papich, M.G. (Ed.), Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs (Fourth Edition). W.B. Saunders, St. Louis, pp. 476–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-24485-5.00355-7.

- Riva L., Yuan S., Yin X., Martin-Sancho L., Matsunaga N., Pache L., Burgstaller-Muehlbacher S., De Jesus P.D., Teriete P., Hull M.V., et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 antiviral drugs through large-scale compound repurposing. Nature. 2020;586:113–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander T., Freyss J., von Korff M., Rufener C. DataWarrior: an open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015;55:460–473. doi: 10.1021/ci500588j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüttelkopf A.W., Van Aalten D.M.F. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein–ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayman, N., DeMarco, J.K., Jones, K.A., Azizi, S.-A., Froggatt, H.M., Tan, K., Maltseva, N.I., Chen, S., Nicolaescu, V., Dvorkin, S., others, 2021. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science (80-.). 373, 931–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tong L. Viral proteases. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4609–4626. doi: 10.1021/cr010184f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich S., Nitsche C. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorganic & Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;127377 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber D.F., Johnson S.R., Cheng H.-Y., Smith B.R., Ward K.W., Kopple K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermersch P., Benrabah R., Schmidt N., Zéphir H., Clavelou P., Vongsouthi C., Dubreuil P., Moussy A., Hermine O. Masitinib treatment in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis: a randomized pilot study. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y., Wang Q., Xu Y., Li M., Li X., Zheng M., Chen L., Li H. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y., et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., et al. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Lin, D., Sun, X., Curth, U., Drosten, C., Sauerhering, L., Becker, S., Rox, K., Hilgenfeld, R., 2020. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science (80-.). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang J., Zeng H., Gu J., Li H., Zheng L., Zou Q. Progress and prospects on vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines. 2020;8:153. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P., Yang, X.-L., Wang, X.-G., Hu, B., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., Si, H.-R., Zhu, Y., Li, B., Huang, C.-L., others, 2020. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]