Abstract

Aims

Negative urgency, which refers to the tendency to act rashly when experiencing intense negative emotions, consistently serves as a robust predictor of problem drinking and other maladaptive behaviors. However, very little is known about the factors that influence the development of negative urgency itself. Although urgency theory suggests that environment and temperament interact to increase risk for the development of urgency, few studies, to date, have examined environmental risk for urgency.

Method

In a cross-sectional sample of 518 adults recruited from Amazon Mturk, the current study began the investigation of the role of childhood maladaptive emotion socialization (MES) in risk for negative urgency and the possibility that negative urgency mediates the relationship between MES and problem drinking via self-report measures completed online. Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling.

Results

Individual differences in childhood MES, reported retrospectively, did predict increased present-day negative urgency. In addition, results were consistent with the possibility that negative urgency mediates the relationship between MES and problem drinking when considered concurrently with trait negative affect.

Conclusions

Successful identification of early environmental predictors of negative urgency may provide useful targets for intervention efforts aimed at reducing or preventing the development of negative urgency and, subsequently, problem drinking. Further longitudinal investigations are needed to better examine these processes as they develop.

INTRODUCTION

Heavy alcohol consumption is associated with numerous short- and long-term negative consequences such as injury, violence perpetration, sexual assault victimization, heart disease, memory problems and early death (World Health Organization, 2014). In the United States, ∼16% of adults report engaging in binge drinking (5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women in a 2-h period) and 7% report engaging in heavy drinking (15 or more drinks for men and 8 or more drinks for women in 1 week) in past 30 days (CDC, 2018). Given the significant individual and public health impact of heavy drinking, it is critical to examine the development of factors that lead to heavy problematic drinking to best inform the creation of effective intervention and prevention programs.

Several theories implicate the consistent experience of strong negative emotionality as a critical risk factor for the development of problem drinking. Specifically, these theories posit that individuals drink alcohol to experience its distress-reducing effects (Sher and Levenson, 1982; Hussong et al., 2017). Successful reductions in distress as a result of drinking reinforce drinking behavior, thus increasing the likelihood that individuals will turn to drinking as a means of coping in the future (Baker et al., 2004). Indeed, prospective studies of emotion-based risk support these theories and, additionally, support the study of specific emotion-based risk factors over negative emotionality broadly (Atkinson et al., 2019).

Urgency (the tendency to act rashly when highly emotional) is one such well-studied specific emotion-based risk factor for problem drinking. Urgency has two variants, positive and negative, which refer to the tendency to act rashly when experiencing intense positive and intense negative emotions, respectively. Urgency theory holds that individuals high in negative urgency are more disposed than others to act in rash, ill-advised ways, including engaging in heavy or problematic drinking, to alleviate unwanted negative emotional states (Cyders and Smith, 2008; Smith and Cyders, 2016). The predictive relationship between negative urgency and problem drinking is robust and has been demonstrated and replicated in numerous longitudinal studies as well as meta-analytic studies of a concurrent predictive relationship (Coskunpinar et al., 2013; Stautz and Cooper, 2013; Berg et al., 2015; Smith and Cyders, 2016). The primary focus of the above literature has been on prospective prediction from urgency to drinking behavior (Smith and Cyders, 2016). Importantly, the relationship between problem drinking and urgency appears reciprocal such that each increases risk for the other (Riley et al., 2016). This is a critical point, given that urgency increases risk for additional forms of dysfunction such as smoking, binge eating, depression, and risky sexual behavior (Smith and Cyders, 2016; Riley and Smith, 2017).

As important as the above findings have been for expanding our current understanding of urgency-based risk for problem drinking, a crucial next step is to determine how to use this knowledge to advance the public health. We considered two possibilities. One would be to intervene to try to reduce levels of the trait of negative urgency, perhaps thus reducing risk for problem drinking and other negative outcomes. Levels of negative urgency can change over time and increases in the trait are predictable from prior drinking behavior (Riley et al., 2016). However, changes in the trait tend to be quite small; overall, negative urgency is a relatively stable trait (Riley et al., 2016). Those who develop high levels of urgency tend to maintain those levels over time, so attempts to modify it to reduce drinking risk may have limited efficacy.

The second possibility we considered was to identify possible antecedents to the development of negative urgency that are themselves modifiable. If such antecedents can be identified, perhaps they can be altered to reduce negative urgency-related risk. Some recent studies have begun this task. Existing models of antecedents of urgency suggest that temperament and environmental factors jointly predict the development of negative urgency (Cyders and Smith, 2008). With respect to temperament, childhood anger reactivity predicted subsequent negative urgency (Waddell et al., 2021). With respect to environmental antecedents of negative urgency, one longitudinal study found that family history of alcohol use disorder (AUD), a strong predictor of drinking behavior, did not appear to directly influence the development of negative urgency (Waddell et al., 2021); another found that child-perceived positive parenting was associated with less negative and positive urgency in adolescents (Bui, 2022); and lastly, drinking experience predicts subsequent increases in negative urgency among adolescents (Riley et al., 2016). In addition, some environmental predictors of urgency may be sex dependent. One study found that parental educational attainment appeared to be negatively related to negative urgency in female children (Assari, 2021) and another found that, in men, parental instrumental support (i.e. monetary support, guidance on how to take care of adult responsibilities, etc.) may be associated with lower levels of negative and positive urgency in emerging adulthood (Szkody et al., 2020).

The current study aimed to contribute to, and expand on, this existing knowledge by examining maladaptive emotion socialization (MES) as a possible environmental risk factor for increased negative urgency and subsequent problem drinking. Emotion socialization, generally, refers to how children learn to view and interpret their emotions through social contexts (Kitzmann, 2012). MES occurs when children learn to view their emotions as inappropriate or aversive through parental/caretaker responses to emotional expressions. Specifically, MES occurs when a child’s expressions of emotions are consistently met with punishment, are minimized, or invoke a reaction of distress from their parents/caretakers.

We propose that MES increases risk for the development of negative urgency in the following way: individuals who are socialized by their parents or caretakers to view their emotions as negative or inappropriate, learn to experience them as aversive. Given this, they may attempt to avoid experiencing their emotions by engaging in urgency-based, negatively reinforcing behaviors, such as heavy or problematic drinking, as they get older. Successful reductions in unwanted emotions as a result of drinking then reinforce drinking behavior, making it more likely that an individual will drink in response to future aversive emotional experiences.

As mentioned, no studies have examined the role of MES in the risk process for the development of negative urgency. However, a small number of studies implicate MES in the risk process for problem drinking and delinquent behavior in adolescents (Hersh and Hussong, 2009; Godleski et al., 2020). Emotion socialization, broadly, is associated with other forms of psychopathology, including externalizing disorders, such that supportive emotion socialization is protective and associated with less future psychopathology in children (Lemerise, 2016; Jin et al., 2017). Conversely, unsupportive emotion socialization, possibly resulting from parental psychopathology, may be associated with greater risk for internalizing psychopathology and impaired development of emotion regulation skills in children (Seddon et al., 2020). Furthermore, childhood maternal emotion socialization and trait negative urgency have both been shown to predict differences in ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC: an area of the brain associated with emotion-guided decision making) activity in response to emotionally salient stimuli (Cyders et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2020). Specifically, more positive maternal emotion socialization was related to more optimal amygdala-vmPFC circuitry functioning in children (Chen et al., 2020) and increased negative urgency was associated with increased vmPFC activity in response to alcohol-related cues in adults (Cyders et al., 2014).

To this end we aimed to investigate the relationship between MES, negative urgency and problem drinking in adults. We hypothesized that (a) negative emotion socialization would be associated with increased negative urgency and (b) the pattern of relationships would support the possibility that negative urgency mediates the relationship between negative emotion socialization and problem drinking. Because negative urgency is related to general negative affect (Settles et al., 2012), we considered it important to test whether negative urgency predicted problem drinking above and beyond prediction from negative affect. We thus tested the two above hypotheses controlling for negative affect. We did so using a cross-sectional design: a successful cross-sectional test of this model would provide the basis for future longitudinal investigations of these relationships to better capture the development of these processes.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 518 (249 female, 266 male, 6 nonbinary) adults recruited from Amazon Mturk. Mean age of participants was 36.9 years (range = 25–55, SD = 8.1). Participants identified as White (77.4%), Black (7.9%), Asian (6.9%), Hispanic (6.8%) and Other (1%).

Measures

Demographics

Demographics were assessed via self-report measures that included items relating to the participants age, gender and race.

Childhood MES

Childhood MES was assessed via the Socialization of Emotion Scale (SES: Sauer and Baer, 2010). Six Likert-type items assess parents’ or caretaker’s typical responses to displays of negative emotions in common situations that may have occurred during participants’ childhoods (example item: ‘If I was panicky and couldn’t go to sleep after watching a scary TV show, my caretaker would: (a) encourage me to talk about what scared me (b) get upset with me for being silly (c) tell me I was over-reacting (d) help me think of something to do so that I could get to sleep (e) tell me to go to bed or I wouldn’t be allowed to watch any more TV (f) do something fun with me to help me forget about what scared me’). Participants were asked to respond retrospectively with the degree to which each parent/caretaker reaction was likely when participants were aged 12 years or younger. MES was calculated by summing the scores from the punitive, minimizing and distress subscales of the SES. Previous studies investigating the role of emotion socialization in the risk process for psychopathology have successfully used this method to categorize adaptive versus maladaptive parental emotion socialization (Mirabile et al., 2016; Premo and Kiel, 2016). Reliability coefficient alphas for the punitive, minimizing and distress subscales were 0.75, 0.71 and 0.78, respectively, and the coefficient for the combined scale was 0.86. Furthermore, the punitive, minimizing and distress subscales correlated 0.57, 0.58 and 0.69 with each other, suggesting a significant overlap between each of the three constructs.

Urgency

Negative urgency was assessed via the UPPS-P, Impulsive Behavior Scale (Lynam et al., 2006). The 59 Likert-type items assess five facets of impulsivity: negative and positive urgency, premeditation, perseverance and sensation seeking. Validity evidence for the negative urgency scale includes convergent and discriminant validity across assessment methods, consistent, replicated longitudinal prediction of numerous rash, impulsive behaviors in accordance with urgency theory and multiple meta-analyses documenting concurrent prediction consistent with urgency theory (review by Smith and Cyders, 2016). For the current sample, alpha was 0.93.

Trait negative affect

Trait negative affect was assessed via the negative affect scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS: Watson et al.,1988). Ten Likert-scale items assess the degree to which one experiences various forms of negative affect in general, that is, on average, including feeling distressed, upset, guilty, scared, hostile, irritable, ashamed, nervous, jittery and afraid. The trait version of the PANAS negative affect scale has been shown to have good test–retest reliability (r = 0.71) over the course of 8 weeks (Watson et al., 1988). The reliability coefficient, alpha, was 0.93.

Problem drinking

Problem drinking was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Task (AUDIT; Babor and Grant, 1989). This 10-item measure assesses drinking frequency, quantity and problems associated with alcohol consumption over the past year. The sum total of AUDIT score was used to represent problem drinking in participants. Alpha for the current sample was 0.87.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via Amazon Mturk. Participants agreed to an electronic informed consent document before study participation. Participants were required to be 18 years of age or older, English speaking and drink alcohol at least once per month. In addition, individuals had to have already successfully completed 100 or more Human Intelligence Tasks on Mturk and have a HIT acceptance rate of 99% or better, a standard use based on recommendations from the literature (Peer et al., 2014). CloudResearch (formerly TurkPrime) was also utilized to employ additional security measures such as blocking duplicate IP addresses, to ensure the highest possible quality of data. Participants completed the self-report measures via Qualtrics: a secure online survey platform. Participants were allowed 90 min to complete the questionnaires, but the average completion time was ∼27 min. Participants were compensated $4 for completing the study. Throughout the survey, participants were required to successfully respond to two attention checks. All study procedures were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Analytic approach

Structural equation modeling was used to test the cross-sectional relationships between variables using Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017). We used the MLR estimation procedure (maximum likelihood, robust to violations of normality). The models assessed for (i) prediction of negative urgency from MES and (ii) prediction of problem drinking from MES via negative urgency and negative affect. In addition, we examined whether intercorrelations between key study variables differed as a function of age, race and gender. We found no significant differences for age, race or gender and thus did not include demographic variables as model covariates.

We expected the results of this model to be consistent with the possibility that negative urgency mediates the predictive influence of MES on problem drinking. We took two additional steps in testing this hypothesized process. The first was we included negative affect as a second mediator of the influence of MES on problem drinking (a dual mediation model), thus permitting a test of whether the indirect effect from MES through negative urgency to problem drinking was above and beyond the predictive and mediating role of general negative affect. The second was to also test a reversed mediation model, designating negative urgency as the predictor, MES as the mediator and problem drinking as the outcome variable. We did not expect to find support for this indirect effect, given that theory holds that negative urgency develops in part due to MES. As is standard in Mplus when using the MLR estimation method, indirect effects were calculated using the delta method.

These models were just identified. We allowed such models because our goal was not to test the fit of an overall model, but rather to test a series of concurrent predictive and indirect effects.

RESULTS

Attrition and treatment of missing data

Of the 535 participants who completed the survey, 17 individuals were eliminated from the final sample due to failure to attend to either of the attention checks presented in the survey. Furthermore, 2.1% of data were missing for a total of 506 complete cases. Key variables NU and AUDIT had no missing data points, whereas NA and SES were missing 1.7% and 0.4%, respectively. Cases with missing data did not differ from those with no missing data on any demographic variable (i.e. age, gender, race) or variables included in the model. We therefore assumed data were missing at random and used the expectation maximization procedure to impute values for the missing data points. This procedure has been shown to produce relatively unbiased population parameter estimates and to be superior to traditional methods (Little and Rubin, 1989). As a result, we were able to make full use of the entire sample of n = 518.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the average scores for negative urgency, MES, negative affect and problem drinking and a correlation matrix of the same variables. The proportion of participants scoring above 8 on the AUDIT, indicating risky or potentially problematic drinking was, 26%. Those above the AUDIT cutoff for risky drinking were significantly higher in trait negative affect (P < 0.01), and negative urgency (P < 0.05), with effect sizes of d = 0.8 and d = 1.1, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for key study variables

| 1. AUDIT | 2. MES | 3. NU | 4.NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 0.12** | 0.47** | 0.39** |

| 2 | - | - | 0.19** | 0.24** |

| 3 | - | - | - | 0.56** |

| Mean | 6.5 | 1.8 | 26.0 | 16.7 |

| SD | 5.4 | 2.1 | 8.4 | 7.5 |

| Range | 0–30 | 0–9 | 12–48 | 10–46 |

* * P < 0.001

Model tests

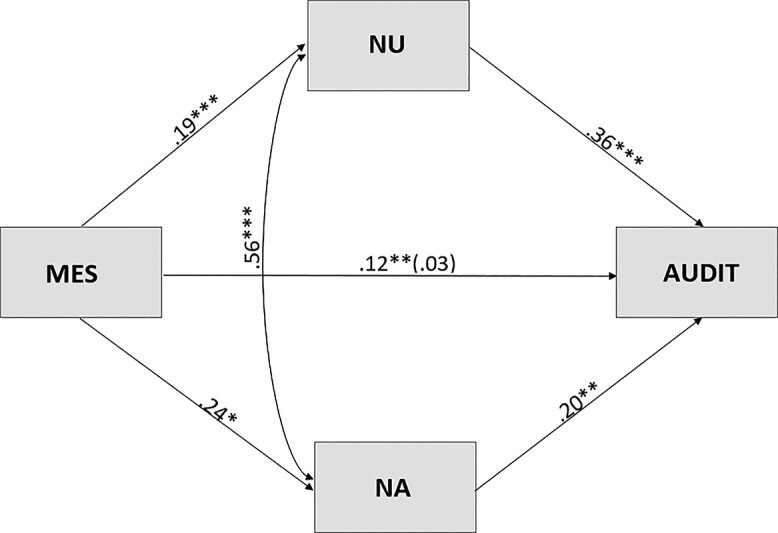

Results of the primary model test are presented in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1, childhood MES, measured retrospectively, significantly concurrently predicted increased present-day negative urgency. Negative urgency, in turn, correlated with AUDIT scores. Indirect effects testing produced result consistent with the possibility that negative urgency mediates the predictive influence of MES on AUDIT scores (b = 0.07, z = 3.23, P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.03, 0.11]). These effects were present while controlling for general negative affect. In fact, results were also consistent with the possibility that negative affect also mediates the predictive effect of MES on AUDIT scores (b = 0.04, z = 3.02, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.02, 0.08]).

Fig. 1.

Full model examining the role of negative urgency (NU) and negative affect (NA) in the predictive relationship between MES and problem drinking (AUDIT).

Last, we tested the reverse mediation model, that MES might mediate the predictive influence of negative urgency on AUDIT scores. We felt that this effect, not based on any a priori hypothesis, would not produce results consistent with a mediation process. As shown in Fig. 2., we found no evidence of an indirect effect from negative urgency through MES to AUDIT scores, nor did we find evidence of such an effect from general negative affect through MES to AUDIT scores. We did one additional test: the reverse mediation from negative urgency through MES to AUDIT scores, not controlling for general negative affect. We again found no indirect effect.

Fig. 2.

Reverse mediation model investigating the possibility that MES might mediate the predictive influence of NU and NA on AUDIT. NU = negative urgency, NA = negative affect, MES = maladaptive emotion socialization, AUDIT = problem drinking. No indirect effects proved significantly different from zero. **P < 0.01 ***P < 0.001

DISCUSSION

A large body of research implicates negative urgency as an important predictor of problem drinking and numerous other maladaptive behaviors. However, significantly less is known about the factors that influence the development of negative urgency itself. The current study aimed to build on existing literature by investigating MES as a possible early antecedent of negative urgency, following Cyders and Smith (2008). Using a cross-sectional design to conduct the first test of this possibility, we examined whether associations were consistent with the hypothesis that MES increased risk for negative urgency and that negative urgency mediates the relationship between MES and problem drinking above and beyond the effect of trait negative affect.

In a sample of adults recruited from Amazon Mturk, retrospectively reported MES in childhood significantly predicted present-day negative urgency. This is consistent with our hypothesis and the existing literature implicating MES in the risk process for self-medicating behavior and other maladaptive behaviors (Hersh and Hussong, 2009; Godleski et al., 2020). The finding that MES concurrently predicts increased negative urgency may prove quite important. This study is the first we know of to test MES as a potential environmental antecedent of negative urgency. Our focus on MES is consistent with urgency theory (Cyders and Smith, 2008). The current cross-sectional test serves as a precursor to future longitudinal investigations of MES in the risk process for the development of negative urgency and its downstream maladaptive consequences.

Results were consistent with the possibility that negative urgency mediates the relationship between MES and problem drinking. Importantly, negative urgency appeared to mediate this relationship even when general negative affect was included in the model and was tested as an additional mediator. The current findings are consistent with prior work examining the predictive role of negative urgency in the risk process for problem drinking (Settles et al., 2010, 2014; Riley et al., 2016) and evidence that negative urgency predicts problem drinking beyond negative affect (Settles et al., 2012).

To provide an additional test of the viability of the mediation hypothesis in this cross-sectional context, we tested a reverse mediation process, that MES might mediate the predictive effects of negative urgency and negative affect on problem drinking. This reverse process is not consistent with existing theory. As expected, we found no evidence consistent with such a process. This negative result only strengthens the argument for moving forward with a longitudinal test of the hypothesized mediational process of MES through negative urgency to problem drinking.

Should future longitudinal tests support negative urgency as mediating the relationship between MES and problem drinking, there may be implications for other urgency-based behaviors. Given that negative urgency increases risk for behaviors such as risky sex, gambling and disordered eating, it is possible that MES may play a significant role in risk for these behaviors as well.

Identifying antecedents to negative urgency is important both for theory development and for clinical application. Concerning the former, understanding the etiology of negative urgency is one part of understanding the etiology of problem drinking and a range of maladaptive, impulsive behaviors. Concerning the latter, the trait of negative urgency is relatively stable across time (Riley et al., 2016). It thus may be that interventions to reduce MES could interrupt the development of negative urgency, thus reducing risk for maladaptive and health-damaging behaviors downstream.

Limitations of the study are as follows. All variables were measured via online questionnaire, so there was no opportunity to discuss the items with participants and answer their questions. Given this, even though there is good evidence for the validity of each measure used, we cannot know with certainty the impact of our assessment method on the results. Further the data were cross-sectional and thus limited the scope of the conclusions that can be drawn from our analyses. Though the results support the possibility that negative urgency mediates the relationship between MES and problem drinking, this is not a test of mediation. In addition, participants in the study were adults aged 25 or older and reflections of parental emotion socialization were retrospective and therefore possibly less accurate. It is possible that the observed processes may operate differently in younger individuals who are able to report on more proximal experiences. The current sample was also not selected for high levels of problem drinking. However, ∼26% of our sample did meet criteria for risky, or problematic, drinking. In addition, given that the sample was comprised of only those who endorsed drinking alcohol, the results may not apply to other behaviors or individuals who do not drink

With these limitations in mind, the current study is the first to provide evidence that (1) MES is associated with negative urgency, a well-established transdiagnostic risk factor and (2) negative urgency may mediate the relationship between MES and problem drinking. The current cross-sectional findings speak to the need to move beyond the cross-sectional and test the mediation hypothesis longitudinally. In addition, investigation of additional environmental risk factors may lead to more comprehensive models of risk for the development of negative urgency and subsequent dysfunction.

Declarations of interest

None.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [T32AA027488] and the Lipman Foundation.

Contributor Information

Emily A Atkinson, University of Kentucky Psychology Department, Lexington KY, USA.

Leo A Miller, University of Kentucky Psychology Department, Lexington KY, USA.

Gregory T Smith, University of Kentucky Psychology Department, Lexington KY, USA.

References

- Assari S. (2021) Association between parental educational attainment and children’s negative urgency: sex differences. Int J Epidemiol Res 8:14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson EA, Ortiz AM, Smith GT. (2019) Affective risk for problem drinking: reciprocal influences among negative urgency, affective lability, and rumination. Curr Drug Res Rev 12:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Grant M. (1989) From clinical research to secondary prevention: international collaboration in the development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). Alcohol Health Res W 13:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE et al. (2004) Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev 111:33–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JM, Latzman RD, Bliwise NG et al. (2015) Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: a meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychol Assessment 27:1129–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui L. (2022) Examining parents’ personality within a five factor model predictive negative and positive urgency in their adolescent children. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing 28651838:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC . (2018) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, McCormick EM, Ravindran N et al. (2020) Maternal emotion socialization in early childhood predicts adolescents' amygdala-vmPFC functional connectivity to emotion faces. Dev Psychol 56:503–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. (2013) Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta-analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:1441–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. (2008) Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychol Bull 134:807–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Dzemidzic M, Eiler WJ et al. (2014) Negative urgency and ventromedial prefrontal cortex responses to alcohol cues: FMRI evidence of emotion-based impulsivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godleski S, Eiden R, Shisler S et al. (2020) Parent socialization of emotion in a high risk sample. Dev Psychol 56:489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh MA, Hussong AM. (2009) The associated between observed parental emotion socialization and adolescent self-medication. J Abnorm Child Psych 37:493–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Ennett W, Cox M et al. (2017) A systematic review of the unique prospective association of negative affect symptoms and substance use controlling for externalizing symptoms. Psychol Addict Behav 31:137–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Zhang X, Han ZR. (2017) Parental emotion socialization and child psychological adjustment among Chinese urban families: mediation through child emotion regulation and moderation through dyadic collaboration. Front Psychol 8:02198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM. (2012) Learning about emotion: cultural and family contexts of emotion socialization. Glob Stud Child 2:82–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise EA. (2016) Social development quartet: emotion socialization in the context of psychopathology and risk. Rev Soc Dev 25:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Whiteside SP, Smith GT et al. (2006) The UPPS-P: Assessing Five Personality Pathways to Impulsive Behavior. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabile SP, Oertwig D, Halberstadt AG. (2016) Parent emotion socialization and children’s socioemotional adjustment: when is supportiveness no longer supportive? Soc Dev 27:466–81. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. (1998–2017) Mplus User’s Guide, 8th edn. Los Angeles: CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Peer E, Vosgerau J, Acquisti A. (2014) Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods 46:1023–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premo JE, Kiel EJ. (2016) Maternal depressive symptoms, toddler emotion regulation, and subsequent emotion socialization. J Fam Psychol 30:276–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EN, Smith GT. (2017) Childhood drinking and depressive symptom level predict harmful personality change. Clin Psychol Sci 5:85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EN, Rukavina M, Smith GT. (2016) The reciprocal predictive relationship between high risk personality and drinking: an 8-wave longitudinal study in early adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 125:798–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer SE, Baer RA. (2010) Validation of measures of biosocial precursors to borderline personality disorder: childhood emotional vulnerability and environmental invalidation. Assessment 17:454–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JA, Abdel-Baki R, Feige S et al. (2020) The cascade effect of parent dysfunction: an emotion socialization transmission framework. Front Psychol 15:579519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders M, Smith GT. (2010) Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychol Addict Behav 24:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Fischer S, Cyders MA et al. (2012) Negative urgency: a personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. J Abnorm Psychol 121:160–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RE, Zapolski TC, Smith GT. (2014) Longitudinal test of a developmental model of the transition to early drinking. J Abnorm Psychol 123:141–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Levenson RW. (1982) Risk for alcoholism and individual differences in the stress response-dampening effect of alcohol. J Abnorm Psychol 91:350–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Cyders MA. (2016) Integrating affect and impulsivity: the role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug Alcohol Depen 163:S3–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. (2013) Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 33:574–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkody E, Rogers MM, McKinney C. (2020) The role of emotional and instrumental support from parents on facets of emerging adult impulsivity. Pers Individ Differ 167:110261. [Google Scholar]

- Waddell JT, Sternberg A, Bui L et al. (2021) Relations between child temperament and adolescent negative urgency in a high-risk sample. J Res Pers 90:104056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. (1988) Development of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2014) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]