Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to investigate the real-life performance of the rapid antigen test in the context of a primary healthcare setting, including symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals that sought diagnosis during an Omicron infection wave.

Methods

We prospectively accessed the performance of the DPP SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test in the context of an Omicron-dominant real-life setting. We evaluated 347 unselected individuals (all-comers) from a public testing centre in Brazil, performing the rapid antigen test diagnosis at point-of-care with fresh samples. The combinatory result from two distinct real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) methods was employed as a reference and 13 samples with discordant PCR results were excluded.

Results

The assessment of the rapid test in 67 PCR-positive and 265 negative samples revealed an overall sensitivity of 80.5% (CI 95% = 69.1%–89.2%), specificity of 99.2% (CI 95% = 97.3%–99.1%) and positive/negative predictive values higher than 95%. However, we observed that the sensitivity was dependent on the viral load (sensitivity in Ct < 31 = 93.7%, CI = 82.8%–98.7%; Ct > 31 = 47.4%, CI = 24.4%–71.1%). The positive samples evaluated in the study were Omicron (BA.1/BA.1.1) by whole-genome sequencing (n = 40) and multiplex RT-qPCR (n = 17).

Conclusions

Altogether, the data obtained from a real-life prospective cohort supports that the rapid antigen test sensitivity for Omicron remains high and underscores the reliability of the test for COVID-19 diagnosis in settings with high disease prevalence and limited PCR testing capability.

Keywords: COVID-19 diagnosis, Evidence-based, Omicron, Rapid antigen test, Viral control

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Rapid antigen tests (RAT) are a powerful tool for the mitigation of the COVID-19 pandemic since it does not require complex laboratory infrastructure, provides the timely result and increase the testing capacity of the healthcare system [1]. The currently available RATs are based on the nucleocapsid amino acid sequences from the early 2020 SARS-CoV-2 lineages [2], which have been fully displaced by multiple waves of variants of concern.

It is not clear whether the nucleocapsid mutations accumulated by the Omicron variant (P13L, del31/33, R203K and G204R) affect the binding affinity of antibodies employed in RATs [3]. To address this question, we prospectively accessed the performance of a RAT widely used in Brazilian public healthcare assistance, in the context of an Omicron-dominant wave real-life setting.

Methods

Samples

The study consisted of a prospective collection of 347 unselected individuals (all-comers) from the public COVID-19 Municipal Testing Center (Caruaru, Brazil). Sample collection was performed between 15 February 2022 and 29 March 2022. The patients enrolled included symptomatic individuals, contacts and asymptomatic individuals that needed testing for travelling. All patients were collected with two nasopharyngeal swabs: one for the PCR test and the other for immediate application of a RAT.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (CEP-CCS/UFPE, CAAE31093420.4.0000.5208) and all the participants signed the written consent.

Rapid antigen test and molecular diagnosis of COVID-19

The DPP® SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test (Chembio) is registered in Brazil with the name TR-DPP® COVID-19 AG Bio-Manguinhos. The RATs were performed in loco, immediately after sample collection, following the manufacturer's instructions.

All enrolled patients were simultaneously tested with two RT-qPCR diagnosis-validated assays: Duplex SARS-CoV-2 E/RP Molecular Kit (Bio-Manguinhos) and the in-house 2019-nCoV_N1/N2/RP protocol (CDC). The details are available in the supplementary material.

Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 variants

The assessment of SARS-CoV-2 lineages from the positive samples was performed with whole-genome sequencing or inference multiplex qPCR. For further details please see the supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

The combinatory result of the two PCR methods was used as the reference standard to calculate the DPP COVID-19 AG performance rates. Mann–Whitney test was used to compare Ct values between groups. The Kappa test determined the agreement rate between the two PCR methods. Statistical tests were applied with a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Clinical-epidemiological characterization of the setting

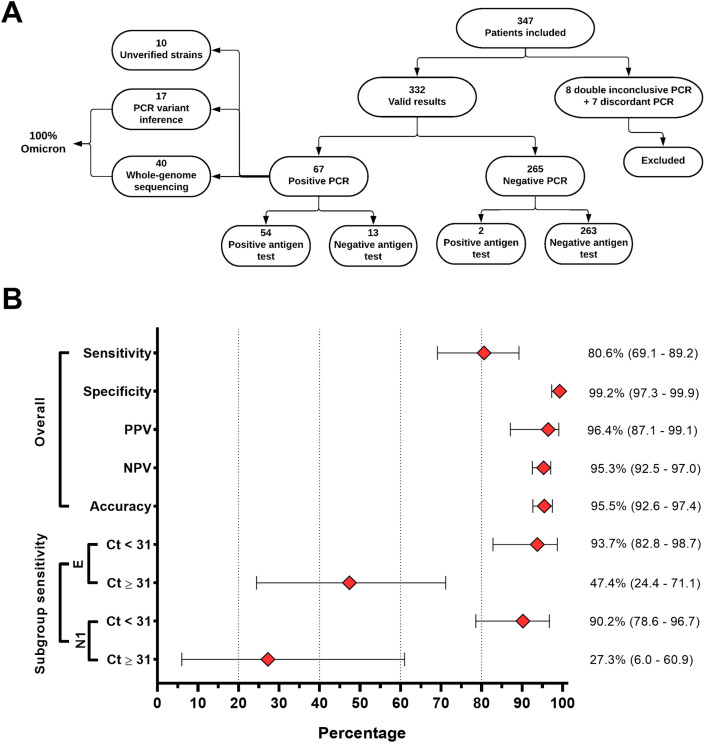

Three hundred thirty-two (95.6%) out of 347 patients enrolled had valid PCR results and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1 A). Of those, 67 were positive for SARS-CoV-2 (based on PCR results) and the disease prevalence in the setting was 20.2%. The epidemiological, clinical, demographic and vaccination features of the study can be found in Figure S1.

Fig. 1.

Study design and DPP SARS-CoV-2 Antigen performance rates. (A) The organogram displays the number of nasopharyngeal samples evaluated and their distribution according to inclusion criteria, diagnostic test results and sequencing. Fifteen percent of the positive samples (n = 10) could not be assessed for the SARS-CoV-2 variant due to the low viral load (B) Performance rates observed in the study. The bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Validation of the PCR-combined reference method

Taking into consideration three possible outcomes (positive, inconclusive and negative), the weighted Kappa index comparing the results from the two PCR methods was 0.885 (CI95% = 0.786–0.910), which is classified as “almost perfect agreement” (Fig. S2). There was a Pearson correlation rate of 0.872 between the Ct values of the two PCR methods (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the PCR and the rapid antigen test results. (A) Correlation between the Ct values from the two PCR methods that were used combined as the reference method. The colourless datapoint represents the outlier sample (B) Distribution of Ct values and the proportion of positive samples in the rapid test. The N1 target (CDC protocol) is more skewed towards lower Ct values whereas the E target (EP/RP kit) is more skewed towards higher Ct Values. The dashed line represents the average values of the Ct values from positive samples. (C) Ct values grouped according to the rapid test result: Ag-positive samples had lower Ct values (higher viral load) than the Ag-negative samples. (D) Probability of positive Ag test according to the Ct values (N1 target) in groups of 3 (e.g. 16–18, 19–21). The curve was calculated by the non-linear asymmetric sigmoidal curve fit.

Evaluation of the TR-DPP COVID-19 Ag test performance

From the 67 PCR-positive patients, 54 also tested positive in the RAT test (overall sensitivity = 80.6%; CI 95% = 69.11%–89.24%) and two out of the 265 PCR-negative patients were false-positive in the RAT (specificity: 99.2%; CI 95% = 97.3%–99.1%). All RATs performed presented a valid result. Moreover, we observed high positive and negative predictive values (96.4% and 95.3%, respectively (Fig. 1B and Table S1).

We observed drastic differences in the test sensitivity across distinct PCR Ct values (Figs. 2B–D). Using a Ct value of 31 as a cut-off, the test sensitivity dropped from 93.7% to 47.4% (N1 target) and from 90.2% to 27.3% (E target) (Fig. 1B). The average N1 Ct values for true positives and false negatives were 24.1 (16–33.5) and 31 (22–37.1), and for the E target were 28.2 (22.2–38.2) and 34.1 (26.9-39.1), respectively (Fig. 2C).

Genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2

We sequenced the SARS-CoV-2 genome of 40 out of 67 positive cases, with an average coverage breadth of 96.4% (87.7%–99.1%) and depth of 245.1 (72.7–948.5). Other 17 samples ineligible for sequencing were characterized with the qPCR inference protocol. All the 57 characterized samples (85% from all positives) were assigned as Omicron (Fig. 1A, Table S2). The phylogenetic analysis revealed that the genomes belong to BA.1 and BA.1-like lineage (Fig. S3).

Discussion

The current study investigated the performance of the DPP SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test in a primary healthcare setting during an Omicron wave. The overall test sensitivity and specificity were within the recommended by the World Health Organization [4] and the European Commission [5]. As previously reported for other RATs [[6], [7], [8], [9]], the sensitivity was reduced in samples with lower viral loads. Of importance, the overall sensitivity observed in the current study was lower than the reported in the product specifications (sensitivity: 90.3 and specificity: 98.8%, www.bio.fiocruz.br) [10]. This divergence is probably due to study design differences, which resulted in distinct Ct values distribution (viral load). The manufacturer evaluated only symptomatic individuals sampled up to nine days from symptoms onset, and 79% of the positive samples had a Ct value lower than 25, while only 48% of the positive cases were within this Ct range in our study. Nevertheless, when analyzing only samples within the Ct < 25 groups, we observed a test sensitivity of 96.6%, which is similar to the reported by the manufacturer (98%) for this subset. By prospectively analyzing patients in a real-life study (all-comers), we were able to avoid bias towards the selection of samples with a higher viral load, allowing a more realistic evaluation of the rapid test.

The current study brings two innovative aspects: (1) all samples were evaluated fresh at point-of-care for the RAT, which is more representative of the routine conditions than frozen retrospective samples, and (2) it evaluates the antigen test in a highly vaccinated population, which might influence the viral load. On the other hand, one important limitation of the study is the low number of positive patients, reducing the statistical resolution in the analysis of positive subgroups.

The RAT presented positive and negative predictive values higher than 95%, which supports its use for COVID-19 diagnosis in high-incidence settings without the need for confirmatory PCR results. However, it is important to stress that: (1) these data should not be extrapolated to other contexts (e.g. testing in hospital admissions) and (2) predictive values are largely influenced by the disease prevalence and the dynamics of the epidemiologic scenario must be taken into consideration for interpreting tests results [4].

Here, we confirmed the Omicron (BA.1/BA.1.1) lineage in all samples eligible for genome sequencing. In line with our findings, recent studies reported no impact of Omicron on the limit of detection [2,11] and the clinical performance [6,12] in other RAT models. Of interest, while BA.2 carries the same mutations in the nucleocapsid as the BA.1, further studies will be required to evaluate the BA.4 and BA.5 lineages, as they acquired the nucleocapsid S413R mutation.

Altogether, the data obtained here supports the maintenance of the rapid antigen test sensitivity for the BA.1 and BA.1.1 Omicron lineage and underscores the reliability of the test for COVID-19 diagnosis in high transmission settings.

Author contributions

This study was conceptualised by MFB, GLW and MHSP; Data curation, investigation and methodology were done by MFB, LCAS, RPS, GLS, GBL and REL. Formal analysis was done by MFB, FZD, and TLC. Resources were collected by MHSP, GLW, MGRP, and MP. The writing was done by MFB, LCAS, and RPS. Reviewing/editing was done by FASS, CD, MP, ABO, TLC, MGRP, GLW, and MHSP.

Transparency declaration

The authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Funding

The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development funded the productivity research fellowship level 2 for Wallau GL (303,902/2019-1). The molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 and characterizations of SARS-CoV-2 variants by real-time PCR at NUPIT-SG was carried out through the resources provided by the Caruaru City Administration (CONVÊNIO nº 13/21 FADE/UFPE/PREFEITURA DE CARUARU and CONVÊNIO FADE/UFPE/PREFEITURA DE CARUARU PROCESSO: 23076.067808/2021-26), the Brazilian Public Labour Prosecution Office (Ministério Público do Trabalho - MPT), the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovações – MCTI, process 01.20.0026.01) and the Brazilian Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação – MEC, process 23076.018503/2020-36).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the healthcare professionals from the Centro Municipal de Testagem de Caruaru for working along with our team to make this work possible. We also appreciate the support of the Fiocruz COVID-19 Genomic Surveillance Network (http://www.genomahcov.fiocruz.br/).

Editor: J. M. Hübschen

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2022.11.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Figure S1.

Figure S2.

Figure S3.

References

- 1.Koo J.R., Cook A.R., Lim J.T., Tan K.W., Dickens B.L. Modelling the impact of mass testing to transition from pandemic mitigation to endemic COVID-19. Viruses. 2022;14:967. doi: 10.3390/v14050967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raïch-Regué D., Muñoz-Basagoiti J., Perez-Zsolt D., Noguera-Julian M., Pradenas E., Munoz E.R., et al. Performance of SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests for omicron and other variants of concern. Front Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.810576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L., Cheng G. Sequence analysis of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant Omicron in South Africa. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1728–1733. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . 2021. Antigen-detection in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection: interim guidance.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345948 Accessed March 20, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Commission Directorate-General For Health And Food Safety . 2022. EU Common list of COVID-19 rapid antigen tests and a list of mutually recognised COVID-19 laboratory based antigenic assays.https://health.ec.europa.eu/health-security-and-infectious-diseases/crisis-management/covid-19-diagnostic-tests_en Updated June 10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michelena P., Torres I., Ramos-García Á, Gozalbes V., Ruiz N., Sanmartin A., et al. Real-life performance of a COVID-19 rapid antigen detection test targeting the SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein for diagnosis of COVID-19 due to the Omicron variant. J Infect. 2022;84:e64–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albert E., Torres I., Bueno F., Huntley D., Molla E., Fernández-Fuentes M.A., et al. Field evaluation of a rapid antigen test (Panbio™ COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device) for COVID-19 diagnosis in primary healthcare centres. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:472.e7–472.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alemany A., Baró B., Ouchi D., Rodó P., Ubals M., Corbacho-Monné M., et al. Analytical and clinical performance of the panbio COVID-19 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test. J Infect. 2021;82:186–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korenkov M., Poopalasingam N., Madler M., Madler M., Vanshylla K., Eggeling R., et al. Evaluation of a rapid antigen test to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection and identify potentially infectious individuals. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00896-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bio.fiocruz.br. DPP® COVID-19 AG. Accessed on July 07, 2022. Available at: https://www.bio.fiocruz.br/index.php/br/produtos/reativos/testes-rapidos/dpp-covid19-ag.

- 11.Stanley S., Hamel D.J., Wolf I.D., Riedel S., Dutta S., Contreras E., et al. Limit of detection for rapid antigen testing of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron and delta variants of concern using live-virus culture. J Clin Microbiol. 2022;60 doi: 10.1128/jcm.00140-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galliez R.M., Bomfim L., Mariani D., de Carvalho Leitão I., Castiñeiras A.C.P., Gonçalves C.C.A., et al. Evaluation of the Panbio COVID-19 antigen rapid diagnostic test in subjects infected with omicron using different specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01250-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]