Abstract

Pyolysin (PLO), the hemolytic exotoxin expressed by Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes, is a member of the thiol-activated cytolysin family of bacterial toxins. Insertional inactivation of the plo gene results in loss of expression of PLO with a concomitant loss in hemolytic activity. The plo mutant, PLO-1, has an approximately 1.8-log10 reduction in the 50% infectious dose compared to that for wild-type A. pyogenes in a mouse intraperitoneal infection model. Studies involving cochallenge of wild-type and PLO-1 bacteria resulted in recovery of similar numbers of both strains, suggesting that PLO production is required for survival in vivo. Recombinant, His-tagged PLO (His-PLO) is cytotoxic for mouse peritoneal macrophages and J774 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Protection against challenge with A. pyogenes could be afforded by vaccination with formalin-inactivated His-PLO, suggesting that PLO is a host-protective antigen, as well as a virulence determinant.

Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes (40) is considered a common inhabitant of the upper respiratory and genital tracts of domestic animals, and recent evidence suggests that A. pyogenes is also found associated with the ruminal wall of cattle (35). Following a precipitating injury or infection, A. pyogenes manifests as one of the most common opportunistic pathogens in domestic ruminants and pigs. In this guise, A. pyogenes is associated with a wide variety of suppurative infections (10, 46), and economically important diseases include summer mastitis (28) and liver abscesses in feedlot cattle (29, 33). However, this organism can infect a wide spectrum of hosts, including avian species (4) and humans (15, 16, 24, 25).

Little is known about either the pathogenesis of, or the antigens important in immunity to, this organism. A. pyogenes elaborates several extracellular toxins, including a hemolysin (14), several proteases (43, 45), a DNase (27), and a neuraminidase (42). While some aspects of these extracellular products have been studied, to date there exists no compelling evidence to support a role for any of these putative virulence factors in the pathogenesis of A. pyogenes infections.

The most well characterized of these toxins is the hemolytic exotoxin pyolysin (PLO) (14). Sequence analysis of the plo gene from A. pyogenes indicates that PLO is a member of the thiol-activated cytolysin (TACY) family of pore-forming toxins (7), found in many gram-positive pathogens (32). These toxins have been implicated in the pathogenesis of infections by Clostridium perfringens (3), Listeria monocytogenes (12), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (5), among others.

In this study, we report that insertional inactivation of the A. pyogenes plo gene results in decreased virulence of the plo mutant and that PLO, like other TACYs, is cytotoxic for phagocytic cells. In addition, we provide evidence that recombinant His-tagged PLO (His-PLO) is efficacious as a vaccine in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, growth conditions, and preparation of culture supernatant fluid (CSF).

A. pyogenes BBR1 was isolated from a bovine abscess (Marana, Ariz.). A. pyogenes strains were grown on brain heart infusion (BHI; Difco) agar plates, supplemented with 5% bovine blood at 37°C and 5% CO2, or in BHI broth supplemented with 5% bovine calf serum at 37°C. Escherichia coli DH5α and DH5α F′ lacIq strains (Bethesda Research Labs) were grown either on Luria-Bertani (Difco) agar or in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C. Antibiotics (Sigma) were added as appropriate; for A. pyogenes strains, erythromycin (ERM) (15 μg/ml) and kanamycin (KAN) (30 μg/ml) were used; for E. coli strains, ampicillin (100 μg/ml), ERM (200 μg/ml), and KAN (50 μg/ml) were used. CSF containing PLO was prepared from liquid cultures of A. pyogenes grown overnight to an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 3.0 to 4.0. Cells were removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g, and the CSF was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter and dialyzed against 400 volumes of 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2 (PBS), for 18 h at 4°C.

DNA techniques.

Preparation of plasmid DNA and electroporation-mediated transformation of A. pyogenes strains were performed as previously described (22). E. coli plasmid DNA extraction, transformation, DNA restriction, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and Southern transfer of DNA to nitrocellulose membranes were performed essentially as described elsewhere (2). Preparation of DNA probes, DNA hybridization, and probe detection were performed with the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

Preparation of His-PLO and His-PLO toxoid.

His-PLO, purified from DH5α F′ lacIq(pJGS59) with TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech), was eluted with 50 mM imidazole–20 mM Tris-HCl–100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0 (7). His-PLO was detoxified by addition of 4.0% (vol/vol) PBS–10% formalin, pH 7.2, for 72 h at 37°C. The formalin was removed by dialysis against 400 volumes of PBS for 18 h at 4°C. Total protein concentration was determined with Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad).

Macrophage cytotoxicity assay.

The murine macrophage-like cell line J774 was cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg of gentamicin per ml (IMDM-10%) in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Mouse peritoneal macrophages were harvested from 8- to 12-week-old, outbred ICR mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley) by peritoneal lavage with 5 ml of ice-cold 0.34 M sucrose. Macrophages or J774 cells in IMDM-10% were seeded into 96-well plates at 4 × 104 cells per well in 50-μl volumes. The cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 h prior to addition of dilutions of His-PLO in IMDM-10%. Cytotoxicity was assessed after 3 h of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 by the CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The percent toxicity was calculated as 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release). The average spontaneous release was 13.3 and 9.6% of the total release for macrophages and J774 cells, respectively.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

CSF was electrophoresed in a 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel essentially as described elsewhere (2). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose, and Western blots were immunostained as previously described (2) with goat anti-His-PLO (7) and rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chains)-peroxidase conjugate as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively.

Hemolytic assays.

Hemolytic assays of CSF preparations were performed as described by Billington et al. (7). The hemolytic titer was the log2 of the reciprocal of the highest dilution which resulted in 50% cell lysis. Antihemolytic titers of antisera were determined as described elsewhere (7). The antihemolytic titer was the log2 of the reciprocal of the antibody dilution which completely neutralized hemolytic activity.

Mouse challenge model and immunization of mice with His-PLO toxoid.

Female, 6- to 8-week-old, outbred ICR mice were challenged intraperitoneally (i.p.) with log-phase A. pyogenes strains as previously described (7). Mice were euthanized on day 7 or when they became moribund. Peritoneal fluid (PF) was obtained by lavage with 3 ml of PBS. Blood and liver were aseptically removed, and the liver was macerated by passage through a 3-ml syringe. Serial dilutions of PF, blood, and liver were incubated on BHI blood agar, and bacterial viable counts were determined. Bacterial cells were heat killed by incubation at 70°C for 30 min. Infection was measured as either mortality or the presence of ≥500 CFU of A. pyogenes per g of liver and per ml of PF, on necropsy. The 50% infectious dose (ID50) was calculated by the Reed-Muench method (47).

Six female, 6-week-old, outbred ICR mice were immunized i.p. with 29 μg of His-PLO toxoid in MPL-TDM emulsion (Ribi Immunochem Research, Inc.) on days 0 and 17. Six similar mice served as unvaccinated controls. Mice were bled from the orbital sinus on days 17 and 33. The mice were challenged i.p. with 4.4 × 108 CFU of log-phase A. pyogenes BBR1 on day 34 as described above.

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of a plo mutant.

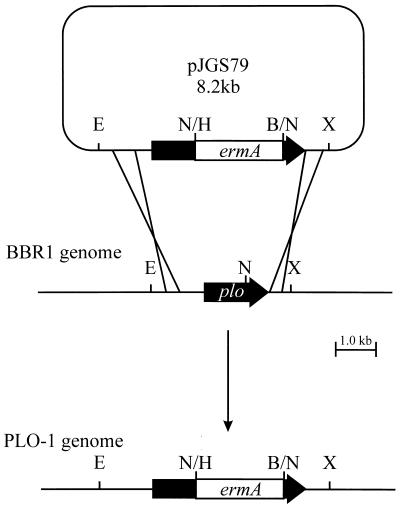

To facilitate the construction of an A. pyogenes plo mutant, a 1.7-kb HindIII-BamHI fragment containing the ermA gene from pNG2 (44) was treated with T4 DNA polymerase (Promega). This fragment was cloned into the similarly treated, unique NheI site in pAp350 to generate the recombinant plasmid pJGS79 (Fig. 1). pAp350 contains the 1,605-bp plo gene on a 3.5-kb EcoRI-XhoI fragment in pBluescript SKII (Stratagene), and the NheI site is located 783 bp into plo (7). Insertion of ermA truncates the plo open reading frame at codon 261. As pJGS79 was based on a ColE1 replicon, it acted as a suicide plasmid in A. pyogenes (22). pJGS79 plasmid DNA was introduced into A. pyogenes BBR1 cells by electroporation, and recombinants were selected on BHI blood agar containing ERM. Fifty-six nonhemolytic, Emr colonies were obtained from this experiment. As cells were incubated for approximately 16 h postelectroporation, this number of recombinants probably arose from two to three recombination events. No hemolytic, Emr colonies were obtained, suggesting that pJGS79 did indeed act as a suicide plasmid and that recombination in all cases was via a double-crossover event.

FIG. 1.

Scheme for insertional inactivation of the A. pyogenes plo gene. An Emr cassette was cloned into the unique NheI site of plo to construct pJGS79, and this plasmid was introduced into A. pyogenes BBR1 by electroporation. Reciprocal recombination resulted in replacement of the endogenous plo gene in the BBR1 chromosome with the insertionally inactivated copy to construct PLO-1. B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; N, NheI; X, XhoI. Only the insert portion of pJGS79 is to scale.

Southern blotting of A. pyogenes genomic DNA digested with EcoRI and XhoI revealed 3.5- and 5.2-kb bands in BBR1 and a plo mutant (PLO-1), respectively, when probed with a plo-specific probe. The same 5.2-kb band was apparent in PLO-1, but not BBR1 genomic DNA, when an Emr gene-specific probe was used. Neither BBR1 nor PLO-1 genomic DNA hybridized with a pBluescript SKII-specific (vector) probe (data not shown). These data confirm disruption of the plo gene in PLO-1, by the integration of the Emr cassette resulting from a double-crossover event.

Insertional inactivation of plo resulted in loss of expression of PLO with a concomitant loss in hemolytic activity, indicating that PLO is the only hemolysin expressed by A. pyogenes under these conditions. PLO-1 appeared to be unaffected in the expression of other extracellular products such as proteases and DNase (data not shown).

In vitro complementation of PLO-1.

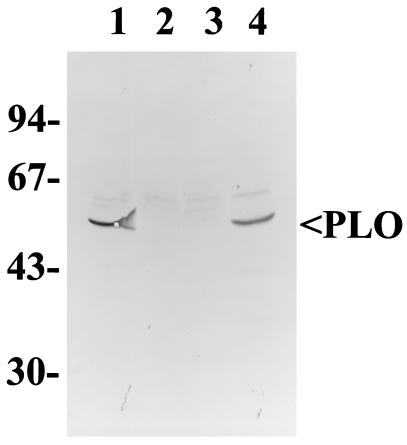

In order to perform complementation assays on PLO-1, the 3.5-kb EcoRI-XhoI fragment containing the wild-type BBR1 plo gene from pAp350 was cloned into pEP2 (39), to form the recombinant plasmid pJGS75. PLO-1 was transformed to Kmr with pEP2 or pJGS75, and the hemolytic activity of CSF was determined by hemolytic assay. Hemolytic titers from cultures of PLO-1 contained no measurable hemolytic activity (<1). In contrast, average titers of PLO-1(pJGS75), but not PLO-1(pEP2), CSF were restored to wild-type levels (7.0, <1, and 7.5, respectively). In addition, Western blotting with antibodies against His-PLO revealed the presence of an approximately 55-kDa band in BBR1 and PLO-1(pJGS75) CSF, but not in PLO-1 or PLO-1(pEP2) CSF (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Western blotting of A. pyogenes CSF. Ten microliters of CSF from BBR1 (lane 1), PLO-1 (lane 2), PLO-1(pEP2) (lane 3), or PLO-1(pJGS75) (lane 4) was separated by SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunostained with a 1/100 dilution of goat anti-His-PLO. The position of the 55-kDa PLO band is indicated. Molecular mass markers in kilodaltons are indicated on the left.

PLO-1 is attenuated for virulence in a mouse model.

The relative virulence of wild-type A. pyogenes and PLO-1 was assessed in a mouse i.p. infection model. Groups of eight mice were challenged with 10-fold serial dilutions of wild-type or PLO-1 A. pyogenes, and the mice were monitored over 7 days. On necropsy, the gross pathology of infected mice revealed the presence of one or more of the following features; pale and/or mottled liver, serofibrinous exudate, pus, and abscess(es) within the abdominal cavity. Abscesses were generally encapsulated and yielded pure cultures of A. pyogenes. Mice which succumbed to lethal infections in less than 24 h did not display this typical pathology; instead, there was severe hemorrhaging of all organs, with no serofibrinous exudate or abscesses present.

The infection rates for wild-type or PLO-1 A. pyogenes are shown in Table 1. Bacterial viable counts were performed on samples of blood, liver, and PF (Table 1). Generally, mice infected with A. pyogenes had large numbers of bacteria in the liver and PF, often present in encapsulated abscesses. Septicemia, as measured by bacterial viable counts in blood, was transient and only variably present and was therefore not a good predictor of infection. The criteria for infection included the presence of ≥500 CFU of A. pyogenes/per g of liver and per ml of PF. Mice which fell short of these criteria were deemed to be in the process of eliminating the bacteria and were not considered to have an active infection.

TABLE 1.

Virulence of wild-type and PLO-1 strains of A. pyogenes

| Challenge strain and CFU | No. infected/total no. | Avg bacterial viable count (CFU) from infected mouse specimen:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blooda | Liver | PF | ||

| BBR1 | ||||

| 3.7 × 107 | 0/8 | —b | — | — |

| 3.7 × 108 | 7/8 | 3.9 × 103 | 1.9 × 108 | 8.7 × 107 |

| 3.7 × 109 | 8/8 | NDc | ND | ND |

| PLO-1 | ||||

| 4.1 × 108 | 0/8 | — | — | — |

| 4.1 × 109 | 3/8 | 1.0 × 103 | 9.0 × 105 | 3.4 × 106 |

| 4.1 × 1010 | 8/8 | 4.0 × 105 | 5.7 × 108 | 6.6 × 109 |

| PLO-1(pEP2) | ||||

| 2.4 × 108 | 0/3 | — | — | — |

| PLO-1(pJGS75) | ||||

| 2.8 × 108 | 3/3 | 3.5 × 102 | 1.5 × 107 | 1.1 × 107 |

Minima detected are 100 CFU/ml of blood, 500 CFU/g of liver, and 10 CFU/ml of PF.

—, below the limits of detection.

ND, not determined.

In this model, infection with 3.7 × 109 wild-type bacteria was uniformly lethal to mice within less than 16 h (Table 1). Challenge with 3.7 × 108 wild-type bacteria resulted in infection within 48 to 72 h in seven of eight mice, while 10-fold less wild-type bacteria were unable to establish an infection. In contrast, 4.1 × 108 PLO-1 bacteria were unable to infect mice, while three of eight mice receiving 4.1 × 109 PLO-1 bacteria became infected within 72 to 96 h. Challenge with 4.1 × 1010 PLO-1 bacteria was uniformly lethal in less than 16 h. While some mice challenged with 4.1 × 109 CFU of PLO-1 developed infections, as determined by pathological and microbiological findings following necropsy, infections in these mice, as measured by signs of disease such as hypoactivity, ruffled appearance, and anorexia, were either not evident or much less severe than in mice challenged with even 10-fold less wild-type bacteria. This finding suggests that mice are able to tolerate large numbers of PLO-1 bacteria without showing discernible signs of disease. The ID50 for wild-type A. pyogenes BBR1 in this model system is 9.9 × 107 CFU. In contrast, the ID50 for PLO-1 was 6.5 × 109 CFU, an approximately 1.8-log10 reduction in virulence.

In this model, >108 and >109 CFU of wild-type and PLO-1 bacteria, respectively, were required for infection. In order to ascertain whether the pathology observed was due to bacterial infection or intoxication from large amounts of toxic cell wall material, mice were challenged with heat-killed bacteria. Challenge with 4.0 × 1010 CFU of heat-killed A. pyogenes BBR1 cells resulted in no signs of illness or toxicity, and mice were normal on necropsy (data not shown).

In vivo complementation of PLO-1 with pJGS75.

The virulence of PLO-1 could be restored by supplying plo on the complementing plasmid, pJGS75 (Table 1), demonstrating that attenuation was due exclusively to the absence of plo, and not other polar effects. Three of three mice challenged with PLO-1(pJGS75) displayed signs typical of wild-type infection, while mice challenged with similar numbers of PLO-1(pEP2) were unaffected (Table 1). To determine the in vivo maintenance of pJGS75, 250 colonies of PLO-1(pJGS75) recovered from infected mice on nonselective medium were patched onto BHI–5% blood agar containing KAN. All these colonies were hemolytic and Kmr, suggesting that pJGS75 is stable in vivo.

PLO-1 can be rescued in vivo by wild-type A. pyogenes.

As PLO is an extracellular toxin, it is possible that the presence of wild-type A. pyogenes secreting PLO would allow persistence of PLO-1 bacteria. Six of six mice coinfected with 1.4 × 108 CFU of A. pyogenes BBR1 and 1.3 × 108 CFU of PLO-1 developed lethal infections within 72 h. An average of 4.5 × 107 CFU and 6.0 × 107 CFU of wild-type BBR1 per g and per ml were recovered from liver and PF, respectively. Approximately 50% less PLO-1 was recovered from each site; averages were 2.0 × 107 CFU/g and 2.8 × 107 CFU/ml from liver and PF, respectively. Both wild-type and mutant bacteria were also recovered from abscesses. This finding suggests that provision of PLO in trans from wild-type cells allowed persistence of PLO-1 in vivo.

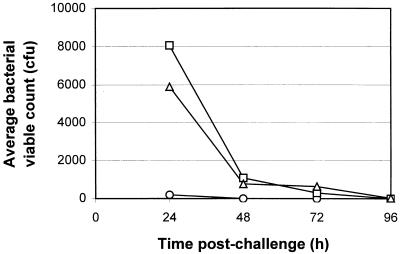

Persistence of PLO-1 in vivo.

In order to determine the persistence of PLO-1 in vivo, eight mice were challenged with 3.9 × 108 CFU of PLO-1, two mice were necropsied at 24-h intervals, and bacterial viable counts were performed. The bacteria were rapidly cleared from the peritoneum with approximately 105-fold fewer bacteria being present 24 h postchallenge (Fig. 3). The bacteria were reduced to undetectable numbers by 96 h. Similar clearance rates were also observed in the liver. Bacteria could be detected in the blood only at 24 h and only in low numbers, indicating the absence of a generalized septicemia following challenge with PLO-1. As noted, challenge with wild-type A. pyogenes was rapidly lethal within 48 to 72 h, with large numbers of bacteria present in both the liver and PF (Table 1).

FIG. 3.

Average bacterial viable counts from mice challenged with 3.9 × 108 CFU of PLO-1. Two mice were necropsied at 24-h intervals postchallenge, and viable bacteria were enumerated in blood (circles), liver (squares), and PF (triangles).

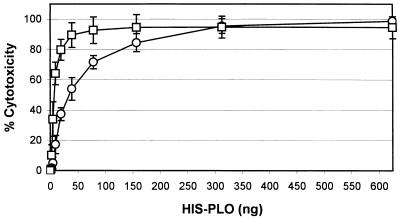

His-PLO is cytotoxic for macrophages.

One possible role for PLO in A. pyogenes pathogenesis is that of a bacterial defense mechanism against host cells, a characteristic common to toxins of the TACY family. The cytotoxicity of His-PLO for macrophages and J774 cells was measured by the release of lactate dehydrogenase into cell culture supernatants, which is a reflection of the loss of plasma membrane integrity. His-PLO was cytotoxic for murine macrophages and J774 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Fifty percent cytotoxicity was achieved with 7.5 and 34.4 ng of His-PLO for macrophages and J774 cells, respectively. J774 cells were approximately 4.6-fold more resistant to the effects of His-PLO but displayed very similar dose-dependent kinetics, and so this cell line will be used in place of peritoneal macrophages to further study the effects of His-PLO cytotoxicity. Interestingly, His-PLO preparations frozen at −20°C prior to assessment of cytotoxicity completely lacked cytotoxic activity, even at 100 times the 100% cytotoxic dose. This result is in contrast to the hemolytic activity, which remained constant following freezing.

FIG. 4.

Percent cytotoxicity following addition of His-PLO to murine macrophages (squares) or J774 cells (circles) as measured by lactate dehydrogenase release with the CytoTox 96 nonradioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega). Error bars represent the standard deviations of averages of four independent experiments.

PLO is a host-protective antigen.

Administration i.p. of 10 μg of untreated His-PLO was lethal in mice. Therefore, His-PLO was inactivated with formalin prior to its use as an immunogen. His-PLO had a specific activity of 128 hemolytic units/μg (7), while the specific activity of His-PLO toxoid was <1 hemolytic unit/μg. The average antihemolytic titer of sera from immunized mice on day 0 was <1, on day 17 was 8.6 (range, 8 to 9), and on day 33 was >11 (range, 9–>12).

Five of six challenged and unvaccinated mice displayed signs of illness by 48 to 72 h, with large numbers of bacteria recovered from the liver and PF (Table 2). In contrast, all the mice vaccinated with His-PLO displayed no signs of illness at any time and had no bacteria or low bacterial viable counts from the liver and PF (Table 2), which were below the criteria for an active infection.

TABLE 2.

Average bacterial viable counts from His-PLO toxoid-immunized and control mice

| Mouse group | Avg bacterial viable count (CFU) for specimen:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blooda | Liver | PF | |

| His-PLO toxoid immunized | —b | 433 | 27 |

| Unimmunized | 320 | 3.5 × 107 | 3.1 × 107 |

Minima detected are 100 CFU/ml of blood, 500 CFU/g of liver, and 10 CFU/ml of PF.

—, below the limits of detection.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of the construction of a mutant strain of A. pyogenes, by insertional inactivation of the plo gene with an Emr cassette. Determination of the ID50s for wild-type A. pyogenes and PLO-1 provides evidence that PLO, a pore-forming cytolysin of the TACY family of toxins, is important for the virulence of this organism in a mouse model.

The TACYs are cholesterol-binding, pore-forming toxins found in gram-positive bacteria (32). When in crude form, these toxins require treatment with reducing agents for full activity, a property which is not observed in the purified toxins (32). PLO shares many properties with the TACYs, with the exception that it does not undergo thiol activation due to a lack of cysteine residues in the protein (7).

As has now been demonstrated for PLO, TACYs play an important role in the pathogenesis of the bacteria which express them. Pneumolysin (PLY), expressed by S. pneumoniae, activates complement (38), stimulates host cytokine production (19), and inhibits the respiratory burst and bacteriocidal activity of neutrophils (37) and monocytes (34). Not surprisingly, insertional activation of the gene encoding PLY results in a significant decrease in virulence in a mouse model (5). Similarly, a mutant of C. perfringens deficient in perfringolysin O expression has reduced lesion severity in a mouse myonecrosis model (3). In addition, perfringolysin O has been demonstrated to promote dysregulated neutrophil-epithelial cell interactions (9). Listeriolysin O (LLO) contributes significantly to the pathogenicity of L. monocytogenes, as the toxin is essential for bacterial escape from the phagolysosome, and mutants in LLO production are avirulent (12). LLO is also cytotoxic for murine macrophages (48) and induces the expression of a variety of host cytokines (26, 36).

Similarly, PLO-1, a plo mutant of A. pyogenes, has an approximate 1.8-log10 reduction in virulence compared to the wild type in a mouse model. Virulence could be fully restored by complementation with the plo-encoding plasmid, pJGS75, indicating that attenuation was due to the absence of PLO and not to other polar effects. Analysis of the pJGS75 insert indicates that the only gene downstream of plo in this plasmid is an incomplete ftsY homologue. Our preliminary data suggest that mutations in ftsY have pleiotropic effects not seen in PLO-1 (17). If insertional inactivation of plo had polar effects on FtsY expression, these could not be complemented by the incomplete ftsY.

Large numbers of A. pyogenes bacteria are required to establish an infection in the mouse model, suggesting that this system may not accurately reflect a natural infection. The limitations of this model may make it difficult to assess the true reduction in virulence of PLO-1. Refinement of this infection model and development of a model which more closely mimics natural infections are currently under investigation.

PLO-1 does not persist in vivo, suggesting that PLO is required for bacterial survival in the host as PLO-1 can be rescued by PLO provided in trans from wild-type A. pyogenes. We have also demonstrated that PLO is cytotoxic for macrophages and J774 cells, in addition to ovine neutrophils (23). However, at this time we are uncertain as to the mechanism of cytotoxicity. Nonspecific pore formation may lead to cell death via ionic disequilibrium, or PLO may specifically trigger macrophage apoptosis, which is commonly associated with the pathogenic processes of some infectious diseases (11, 41, 49). Mouse dendritic cells undergo apoptosis when treated with purified LLO (18).

One possible role of PLO in pathogenesis may be to deplete host macrophages (and neutrophils), protecting bacteria from phagocytosis. LLO can directly inhibit macrophage phagocytosis of opsonized erythrocytes (48), and PLY inhibits the bacteriocidal activity of neutrophils (37) and monocytes (34). Although TACYs such as LLO and PLY upregulate expression of various cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha by macrophages and monocytes (19, 26, 36), depletion of phagocytic cells may lead to decreased cytokine signaling, further impairing host responses against infection. Furthermore, pore formation in macrophage cell membranes may result in the release of biologically active macromolecules such as lysosomal enzymes, which can potentially cleave cytokine receptors, leading to further inappropriate cell signaling events (6).

Studies with LLO suggest that the pore-forming and cytokine-inducing domains may be distinct on the LLO molecule (36, 48). Specific cytotoxicity of PLO, apart from pore formation, is supported by the observation that His-PLO loses its cytotoxic, but not its hemolytic, activity following storage at −20°C. It is possible that aggregation or oligomerization of the protein following freezing and thawing results in occlusion of a critical cytotoxic domain apart from the undecapeptide region shown to be important in hemolytic activity (32). Construction of nonhemolytic mutants of PLO, currently in progress in our laboratory, will allow this question to be answered.

There have been several attempts to vaccinate mice (13), cattle (8, 31), and sheep (20) with formalin-inactivated crude A. pyogenes supernatant. Results of these experiments were equivocal, probably due to varying amounts of hemolysin in the immunizing preparation. In the first study using a defined, purified recombinant PLO immunogen, we demonstrated that active vaccination with His-PLO resulted in neutralizing antibodies, which protected mice against challenge with A. pyogenes, suggesting that PLO is important as a host-protective antigen. Previously, we demonstrated that passive vaccination with antiserum against His-PLO can protect against A. pyogenes challenge (7), suggesting that protection is mainly humorally mediated. Other TACYs have been successfully used as experimental vaccines. Vaccination with PLY afforded significant protection in a mouse model (1, 30), while suilysin has been successfully used to vaccinate pigs against Streptococcus suis challenge (21).

PLO is an important factor for in vivo survival of A. pyogenes, possibly protecting bacteria from host immune defenses during the early stages of infection. Therefore, it is not surprising that it is also a host-protective antigen and may be useful as a vaccine candidate against A. pyogenes infections. Further vaccination experiments with a more appropriate animal model, such as liver abscess development in feedlot cattle, will be an important step in determining the efficacy of PLO-based vaccines for A. pyogenes disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by an NRI Competitive Grants Program/USDA award (97-02507).

We thank Stefani T. Gilbert for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander J E, Lock R A, Peeters C C A M, Poolman J T, Andrew P W, Mitchell T J, Hansman D, Paton J C. Immunization of mice with pneumolysin toxoid confers a significant degree of protection against at least nine serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5683–5688. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5683-5688.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awad M M, Bryant A E, Stevens D L, Rood J I. Virulence studies on the chromosomal α-toxin and θ-toxin mutants constructed by allelic exchange provide genetic evidence for the essential role of α-toxin in Clostridium perfringens-mediated gas gangrene. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:191–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour E K, Brinton M K, Caputa A, Johnson J B, Poss P E. Characteristics of Actinomyces pyogenes involved in lameness of male turkeys in north-central United States. Avian Dis. 1991;35:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry A M, Yother J, Biles D E, Hansman D, Paton J C. Reduced virulence of a defined pneumolysin-negative mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2037–2042. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2037-2042.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhakdi S, Walev I, Jonas D, Palmer M, Weller U, Suttorp N, Grimminger F, Seeger W. Pathogenesis of sepsis syndrome: possible relevance of pore-forming bacterial toxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;216:101–118. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80186-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billington S J, Jost B H, Cuevas W A, Bright K R, Songer J G. The Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes hemolysin, pyolysin, is a novel member of the thiol-activated cytolysin family. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6100–6106. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6100-6106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J A, Stuart J D. The treatment of summer mastitis using Corynebacterium pyogenes toxoid. Vet Rec. 1943;55:315–316. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant A E, Bergstrom R, Zimmerman G A, Salyer J L, Hill H R, Tweten R K, Sato H, Stevens D L. Clostridium perfringens invasiveness is enhanced by effects of theta toxin upon PMNL structure and function: the roles of leukocytotoxicity and expression of CD11/CD18 adherence glycoprotein. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:321–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter G R, Chengappa M M. Essentials of veterinary bacteriology and mycology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea and Febiger; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Zychlinsky A. Apoptosis induced by bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:203–212. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cossart P, Vicente M F, Mengaud J, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz J C, Berche P. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3629-3636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derbyshire J B, Matthews P R J. Immunological studies with Corynebacterium pyogenes in mice. Res Vet Sci. 1963;4:537–542. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding H, Lämmler C. Purification and further characterization of a haemolysin of Actinomyces pyogenes. J Vet Med B. 1996;43:179–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1996.tb00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drancourt M, Oulès O, Bouche V, Peloux Y. Two cases of Actinomyces pyogenes infection in humans. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:55–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01997060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gahrn-Hansen B, Frederiksen W. Human infections with Actinomyces pyogenes (Corynebacterium pyogenes) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;15:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(92)90022-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert, S. T., B. H. Jost, J. G. Songer, and S. J. Billington. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 18.Guzmán C A, Domann E, Rohde M, Bruder D, Darji A, Weiss S, Wehland J, Chakraborty T, Timmis K N. Apoptosis of mouse dendritic cells is triggered by listeriolysin, the major virulence determinant of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houldsworth S, Andrew P W, Mitchell T J. Pneumolysin stimulates production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β by human mononuclear phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1501–1503. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1501-1503.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter P, van der Lugt J J, Gouws J J. Failure of an Actinomyces pyogenes vaccine to protect sheep against an intravenous challenge. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1990;57:239–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs A A, van den Berg A J G, Loeffen P L W. Protection of experimentally infected pigs by suilysin, the thiol-activated haemolysin of Streptococcus suis. Vet Rec. 1996;139:225–228. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.10.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jost B H, Billington S J, Songer J G. Electroporation-mediated transformation of Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes. Plasmid. 1997;38:135–140. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jost, B. H., J. G. Songer, and S. J. Billington. 1999. Unpublished data.

- 24.Kotrajaras R, Buddhavudhikrai P, Sukroongreung S, Chanthravimol P. Endemic leg ulcers caused by Corynebacterium pyogenes in Thailand. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:407–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1982.tb03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotrajaras R, Tagami H. Corynebacterium pyogenes. Its pathogenic mechanism in leg ulcers in Thailand. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb04575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhn M, Goebel W. Induction of cytokines in phagocytic mammalian cells infected with virulent and avirulent Listeria strains. Infect Immun. 1994;62:348–356. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.348-356.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lämmler C. Untersuchungen zu möglichen Pathogenitätsfaktoren von Actinomyces pyogenesÜbersichtsreferat. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 1990;103:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lean I J, Edmondson A J, Smith G, Villanueva M. Corynebacterium pyogenes mastitis outbreak in inbred heifers in a California dairy. Cornell Vet. 1987;77:367–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lechtenberg K F, Nagaraja T G, Leipold H W, Chengappa M M. Bacteriologic and histologic studies of hepatic abscesses in cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lock R A, Hansman D, Paton J C. Comparative efficacy of autolysin and pneumolysin as immunogens protecting mice against infection by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:137–143. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovell R, Foggie A, Pearson J K L. Field trials with Corynebacterium pyogenes alum-precipitated toxoid. J Comp Pathol. 1950;60:225–229. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(50)80021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan P J, Andrew P W, Mitchell T J. Thiol-activated cytolysins. Rev Med Microbiol. 1996;7:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagaraja T G, Laudert S B, Parrott J C. Liver abscesses in feedlot cattle. Part I. Causes, pathogenesis, pathology, and diagnosis. Comp Cont Edu Pract Vet. 1996;18:S230–S241. , S256. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nandoskar M, Ferrante A, Bates E J, Hurst N, Paton J C. Inhibition of human monocyte respiratory burst, degranulation, phospholipid methylation and bacteriocidal activity by pneumolysin. Immunology. 1986;59:515–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narayanan S, Nagaraja T G, Wallace N, Staats J, Chengappa M M, Oberst R D. Biochemical and ribotypic comparison of Actinomyces pyogenes and A. pyogenes-like organisms from liver abscesses, ruminal wall, and ruminal contents of cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishibori T, Xiong H, Kawamura I, Arakawa M, Mitsuyama M. Induction of cytokine gene expression by listeriolysin O and roles of macrophages and NK cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3188–3195. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3188-3195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paton J C, Ferrante A. Inhibition of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte respiratory burst, bacteriocidal activity, and migration by pneumolysin. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1212–1216. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1212-1216.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paton J C, Rowan-Kelly B, Ferrante A. Activation of human complement by the pneumococcal toxin pneumolysin. Infect Immun. 1984;43:1085–1087. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.3.1085-1087.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radford A J, Hodgson A L. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium-Escherichia coli shuttle vector. Plasmid. 1991;25:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(91)90029-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramos C P, Foster G, Collins M D. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Actinomyces based on 16S rRNA gene sequences: description of Arcanobacterium phocae sp. nov., Arcanobacterium bernardiae comb. nov., and Arcanobacterium pyogenes comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:46–53. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruckdeschel K, Roggenkamp A, Lafont V, Mangeat P, Heesemann J, Rouot B. Interaction of Yersinia enterocolitica with macrophages leads to macrophage cell death through apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4813–4821. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4813-4821.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaufuss P, Lämmler C. Characterization of the extracellular neuraminidase produced by Actinomyces pyogenes. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1989;271:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(89)80050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaufuss P, Sting R, Lämmler C. Isolation and characterization of an extracellular protease of Actinomyces pyogenes. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1989;271:452–459. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(89)80104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serwold-Davis T M, Groman N B. Mapping and cloning of Corynebacterium diphtheriae plasmid pNG2 and characterization of its relatedness to plasmids from skin coryneforms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:69–72. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeuchi S, Kaidoh T, Azuma R. Assay of proteases from Actinomyces pyogenes isolated from pigs and cows by zymography. J Vet Med Sci. 1995;57:977–979. doi: 10.1292/jvms.57.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Timoney J F, Gillespie J H, Scott F W, Barlough J E. Hagan and Bruner’s microbiology and infectious diseases of domestic animals. 8th ed. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welkos S, O’Brien A. Determination of median lethal and infectious doses in animal model systems. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:29–39. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshikawa H, Kawamura I, Fujita M, Tsukada H, Arakawa M, Mitsuyama M. Membrane damage and interleukin-1 production in murine macrophages exposed to listeriolysin O. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1334–1339. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1334-1339.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zychlinsky A, Prévost M-C, Sansonetti P J. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature. 1992;358:167–169. doi: 10.1038/358167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]