Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (Mpro) is the critical cysteine protease in coronavirus viral replication. Tea polyphenols are effective Mpro inhibitors. Therefore, we aim to isolate and synthesize more novel tea polyphenols from Zhenghedabai (ZHDB) white tea methanol-water (MW) extracts that might inhibit COVID-19. Through molecular networking, 33 compounds were identified and divided into 5 clusters. Further, natural products molecular network (MN) analysis showed that MN1 has new phenylpropanoid-substituted ester-catechin (PSEC), and MN5 has the important basic compound type hydroxycinnamoylcatechins (HCCs). Thus, a new PSEC (1, PSEC636) was isolated, which can be further detected in 14 green tea samples. A series of HCCs were synthesized (2–6), including three new acetylated HCCs (3–5). Then we used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to analyze the equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for the interaction of 12 catechins and Mpro. The KD values of PSEC636 (1), EGC-C (2), and EC-CDA (3) were 2.25, 2.81, and 2.44 μM, respectively. Moreover, compounds 1, 2, and 3 showed the potential Mpro inhibition with IC50 5.95 ± 0.17, 9.09 ± 0.22, and 23.10 ± 0.69 μM, respectively. Further, we used induced fit docking (IFD), binding pose metadynamics (BPMD), and molecular dynamics (MD) to explore the stable binding pose of Mpro-1, showing that 1 could tightly bond with the amino acid residues THR26, HIS41, CYS44, TYR54, GLU166, and ASP187. The computer modeling studies reveal that the ester, acetyl, and pyrogallol groups could improve inhibitory activity. Our research suggests that these catechins are effective Mpro inhibitors, and might be developed as therapeutics against COVID-19.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, Surface plasmon resonance, Green tea, Induced fit docking, Molecular dynamics, Binding pose metadynamics

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

COVID-19 is a devastating pandemic disease due to its rapid transmission and the initiation of progressive respiratory failure [1]. Therefore, finding specific drugs and new therapeutic strategies is urgent and crucial. Previous studies show that SARS-CoV-2-Mpro (Mpro) is a promising target owing to its catalysis of virus replication and infection [2]. Mpro is a nucleophilic cysteine protease with the active catalytic dyad pocket by amino acid residues CYS145 and HIS41. HIS41 can accelerate the hydrolysis of the –SH group in CYS145, thus carrying out the nucleophilic attack on the substrate [3]. Based on this critical target, six active compounds were achieved through screening 10,000 molecules using the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay, among which ebselen significantly inhibits the Mpro (IC50 = 0.67 ± 0.05 μM) by combining with the –SH group of amino acid residue CYS145 [4]. Peptidomimetics inhibitors have been discovered and developed, such as peptidyl aldehydes [5], peptidyl fluoroethyl ketones [6], and acyloxymethyl ketones [7]. These inhibitors can directly interact with a biological target. Besides, non-peptidic inhibitors inactivate the Mpro by forming covalent, hydrogen, and hydrophobic bonds. For example, phloroglucinol-terpenoids have vital interactions with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic bonds, and the spatial occupation of the B ring [8]; the pyrogallol moiety of myricetin covalently binds with the –SH group and modifies the catalytic cysteine as an electrophile warhead [9]; proanthocyanidins and pentagalloylglucose as natural polyphenols have potential antiviral activity [10].

Computer-aided drug design (CADD) are prevalent in drug development, including virtual screening, inhibitor screening, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation [[11], [12], [13]]. Compared with rigid receptor docking, the induced fit docking (IFD) method can explain more plausible spatial conformation of the receptor in the presence of ligands and further evaluate a more reliable complex. Binding pose metadynamics (BPMD) is a sampling enhanced, automated, and metadynamics-based method combined with IFD protocol to strengthen the accuracy of IFD results [14]. BPMD protocol can discriminate the well-fined and not supported electron density binding pose, which can screen out more reasonable binding postures [15]. IFD, BPMD, and MD simulations have been used to investigate binding modes of receptor-molecular complexes based on bioactive experiments [16].

Phenylpropanoid-substituted ester-catechins (PSECs) and hydroxycinnamoylcatechins (HCCs) have stronger pharmacological effects than simple catechins in some assays. Zijuanins C & D can protect SH-SY5Y cells from excessive damage induced by H2O2 [17]. Zijuanin E & F could extend the lifespan of C. elegans to 67.2% and 56.0% [18]. (−)-Epicatechin 3-O-caffeoate (EC-C) has significant inhibitory effects against acetylcholinesterase and Mpro [19,20]. Based on the above information, we synthesized five HCCs. One new PSEC with a molecular weight of 636 (abbreviated as PSEC636, 1) was isolated from Zhenghedabai (ZHDB) white tea, which can be detected in 14 green tea products, especially in Zijuan green tea. This article described the isolation and structural identification of the new catechin derivatives and studied their Mpro binding affinity and inhibitory effects by SPR and FRET experiments. Additionally, the stability and final conformation of the Mpro -1 complex were determined by IFD, BPMD, and MD simulations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical reagents and instruments

All the analytical reagents (petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, methanol, dichloromethane, n-hexane, chloroform) were purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). Pure distilled water was purchased from Watson's Food & Beverage Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Chromatographic grades of methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid were purchased from Duksan Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd. (Ulsan, Korea). Mass spectrometric grade acetonitrile and formic acid were obtained from Fisher Chemical (Fair Lawn, NJ, U.S.A.). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on GF254 (Yantai Jiang You Silicon Development Co., Ltd., Shandong, China), and the chromatogram was visualized by spraying the plates with 5% FeCl3. Column chromatography (CC) was performed using MCI-Gel CHP20P (Mitsubishi Ltd., Japan), Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare Biosciences AB, Sweden), Toyopearl HW-40F (Tosoh Bioscience Shanghai Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and silica gel (Yantai Jiang You Silicon Development Co., Ltd., Shandong, China). CM7 sensor chip, 10 × PBS-P buffer (containing 0.2 M phosphate buffer, 27 mM and 1.37 M NaCl, 0.5% Surfactant P20, 2% DMSO, pH adjusted to 7.4), sodium acetate, and amino coupling kit were purchased from Cytiva (Uppsala, Sweden). 2019-nCoV Mpro and Mpro inhibitor screening kit were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

Waters e2695 HPLC system with a Waters 2998 PDA detector (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, U.S.A.) combined with Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 column [5 μm, 9.4 (internal diameter) × 250 (length) mm] (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used in the semi-preparation. With the electrospray ionization (ESI) source in negative mode, the Agilent 1290 ultra-high performance liquid phase (UPLC) combined with 6545 times-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer system (Agilent, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) was used to collect mass spectra. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 with Brucker Avance Neo 500 MHz NMR (Karlsruhe, Germany) and Agilent DD2 600 MHz NMR (Agilent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.) in DMSO-d6 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA, U.S.A.). Infrared spectral analyses were recorded using a Thermo Nicolet 8700 FTIR spectrophotometer (Thermo Co., Waltham, MA). Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were tested with a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter (Tokyo, Japan). Optical rotations were measured with a Digipol-P630 automatic polarimeter (Shanghai JiaHang Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.2. DPPH radical scavenging activity

The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity was determined as the previous method with slight modification [21]. The five extracted parts of ZHDB tea, including petroleum ether (PE), ethyl acetate (EA), methanol (ME), dichloromethane (DM), and methanol-water (MW), were dissolved into different concentrations (Table S1) for antioxidant experiments. Then we prepared the mixture system in the 96-well microplates, including 100 μL tested samples and 100 μL DPPH-ethanol solution (200 μM). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then we used a microplate reader (DU-730, Beckman Coulter, U.S.A.) to measure the absorbance at 517 nm. The above experiments were carried out three times, and the following formula was used to calculate the free radical scavenging capacity:

| DPPH radical scavenging (%) = (1 – [(Asample – Ablank)/Acontrol]) × 100 |

where Acontrol is the absorbance of water mixed with DPPH solution; Asample indicates the absorbance of sample mixed with DPPH solution; Ablank is the absorbance of sample mixed with ethanol.

2.3. Acquisition of catechin derivatives

2.3.1. GNPS guided analysis of composition separation profile of ZHDB tea

To observe the chemical profile of ZHDB tea extract, we established a structure-based molecular network. Through the built-in software qualitative analysis of Agilent liquid phase mass spectrometry equipment, the original LC-MS/MS data of 127 important components were extracted. Then we used MScover (protowizard, http://proteowizard.sourceforge.net/) software to transform the data into Mzml format and FTP software to transfer files to Molecular Networking workflow of Global natural products social molecular networking (GNPS) (http://gnps.ucsd.edu) platform as the medium-sized data input. After analyzing mass spectrometry data with their similarity to GNPS platform, the correlation parameters are as follows: (1) basic options: precursor ion mass tolerance, 0.02 Da; fragment ion mass tolerance, 0.02 Da; (2) advanced network options: min pairs cosine, 0.5; network topK, 30; maximum connected component size, 200; minimum matched fragment ions, 4; minimum cluster size, 5; (3) advanced library search options: min matched peaks, 4; score threshold, 0.7; and (4) advanced filtering options: filter below stddev, 3; minimum peak intensity, 50. Other parameters remained at default values. Last, we used Cytoscape 3.7.1 software (https://cytoscape.org) to analyze the molecular network results visually.

2.3.2. Separation and purification of 1

Six kg tea samples were ground into powder (60–80 mesh) and sequentially extracted by petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, and methanol with the aid of vacuum concentrators and ultrasonic. Removing the excessive caffeine from tea by dichloromethane extraction, we got the methanol-water extract (800 g). The extract was separated by MCI, Toyopearl, and Sephadex-LH20 CC, respectively, eluted with methanol/water (0:1 to 1:0, v/v). The main elution procedure is from high to low polarity with water to methanol. The compounds were traced with ethyl acetate-methanol-water (100:17:13) as a developing agent and 5% FeCl3 as a chromogenic agent in silica gel GF254 plate. Meanwhile, Waters HPLC e2695-2998 was used to identify fractions and semi-preparative separation precisely. The analytical procedure was carried out using ACE Excel 5C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm). The column temperature, injection volume, flow rate, and detection wavelengths were set at 30 °C, 10 μL, 1.0 mL/min, and 190–400 nm, respectively. The elution gradient conditions using the mobile phase A (water) and phase B (acetonitrile) were as follows: 0–4 min: 6/94 (B/A, mL/mL); 4–16 min: from 6/94 to 14/86; 16–22 min: from 14/86 to 15/85; 22–32 min: from 15/85 to 18/82, 32–37 min: from 18/82 to 29/71; 37–45 min: from 29/71 to 45/55; 45–49 min: from 45/55 to 95/5; 49–54 min: 95/5; 54–56 min: from 95/5 to 6/94; 56–60 min: 6/94. The semipreparative HPLC separation was performed using the ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18 column (9.4 × 250 mm, 5 μm) at the column temperature of 30 °C, the injection volume at 30 μL, the flow rate at 2.0 mL/min, and the detection wavelengths at 210 and 270 nm. The elution gradient conditions using the mobile phase A (water) and phase B (acetonitrile) were as follows: 0–10 min: from 20/80 to 25/75; 10–16 min: from 25/75 to 29/71; 16–17 min: from 29/71 to 95/5; 17–18 min: 95/5,18–19.5 min: from 95/5 to 20/80; 19.5–22 min: 20/80.

2.3.3. Synthesis of hydroxycinnamoylcatechins (HCCs)

HCCs were synthesized using the reported methods [22]. Briefly, the silyl groups were removed using a modified method (Fig. S1). The resulting mixture was stirred for 3 h at 20 °C. The solvent was diluted with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by CC using silica gel (petroleum ether/ethyl acetate = 1:1). Then, we can get 2 [(−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-caffeoate (EGC-C)], 3 [3″,4″-diacetyl-O-(−)-epicatechin 3-O-caffeoate (EC-CDA)], 4 [4″-acetyl-O-(−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate (EGC-pCA)], 5 [4″-acetyl-O-(−)-epicatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate (EC-pCA)], 6 [(−)-epicatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate (EC-pC)]. The synthesized compounds were comprehensively identified using HR-MS, NMR, IR, CD, and ORD. In addition, the full NMR spectra of the new compounds (1, 3–5) were identified for the first time.

2.3.4. Mass spectrometer data acquisition and detection

Agilent 1290 and a 6545 Q-TOF mass spectrometer with ESI were used to acquire MS data (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Q-TOF parameters were the same as before [23]. ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) was used to detect the chromatographic peak with the binary pump modular: the eluent composed with mobile phase A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid), the flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, sample manager temperature of 10 °C, column temperature of 30 °C, and 3 μL injection volume. Since different use in the MS data acquisition, we listed the different methods as follows. MS data acquisition for 1: 0–0.5 min: 5/95 (B/A); 0.5–1.5 min: from 5/95 to 10/90; 1.5–4.0 min: from 10/90 to 25/75; 4.0–6.0 min: from 25/75 to 35/65; 6.0–7.5 min: from 35/65 to 65/35; 7.5–8.5 min: from 65/35 to 85/15; 8.5–9.0 min: from 85/15 to 95/5; 9.0–10.0 min: 95/5, 10.0–11.0 min: from 95/5 to 5/95; 11.0–12.0 min: 5/95. MS data acquisition for 1–6: 0–2 min: 10/90 (B/A) to 95/5; 2–4 min: 95/5 to 10/90; 4–5 min: 10/90.

Eighteen green tea samples (Table S2) were selected for qualitative analysis of 1 by targeted MS/MS mode. The dry leaves of 18 tea samples were powdered and weighed 100 mg in three parallels. Then 3 mL petroleum ether was added for ultrasound-assisted extraction (2 h). After that, we used a high-speed centrifuge at 13,000 rpm to discard the supernatant. Then 4 mL 70% methanol-water was added for further extraction (3 h). Finally, we got the 54 supernatants from the methanol-water extracts, and MS data acquisition elution ratio was as follow: 0–1.0 min: 10/90 (B/A); 1.0–2.5 min: from 10/90 to 20/80; 2.5–6.0 min: from 20/80 to 24/76; 6.0–10.0 min: from 24/76 to 26/74; 10.0–11.0 min: from 26/74 to 28/72; 11.0–11.5 min: from 28/72 to 30/70; 11.5–13.5 min: 30/70–95/5; 13.5–15.0 min: 95/5; 15.0–16.0 min: from 95/5 to 10/90; 16.0–17.0 min: 10/90. Targeted MS/MS precursor ions included the following parameters: [M − H]−, 635.1406 (rt: 7.47 min; CE: 25 eV).

2.4. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) technique

2.4.1. Coupling of 2019-nCoV main protease on the CM7 chip

Our running buffer was 1 × PBS (using deionized water to dilute 10 × PBS ten times), at least 200 mL daily. The first step is activating the channel of the CM7 sensor chip; 0.4 M EDC/0.1 M NHS (1:1, v/v) were mixed in a 1.5 mL tube as the coupling reagent, injecting this solvent with the flow rate of 10 μL/min for 300 s. The optimized sodium acetate (pH 5.0) was used to dilute 1 mg/mL Mpro (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) into 10 μg/mL, and a 10 μL/min flow rate was kept for 600 s. The final coupling signal with a maximum immobilization level of 30,000 RU was set. Finally, we injected 1 M ammonium ethoxide at the flow rate of 10 μL/min for 300 s to block the channel.

2.4.2. Direct capture and detection of catechins

Two-fold serial dilutions of 12 catechins (0.39, 0.78, 1.56, 3.13, 6.25, 12.50, 25.00, 50.00, 100.00 μM) using 1 × PBS-P buffer dilution for the interaction experiments. The flow rate was set and maintained at 30 μL/min. Then catechins were injected onto the Mpro immobilized CM7 chip for 180 s, and 1 × PBS-P buffer was injected for 150 s to regenerate the chip surface at the end of each experiment. KD values mainly evaluate the Mpro-catechins binding affinity by the steady-state affinity fitting analysis of the Biacore data using Biacore T200 Evaluation software (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

2.5. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) inhibition assays

SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition was performed via a 2019-nCoV Mpro/3CLpro inhibitor screening kit P0312 (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), which mainly used FRET methods [4] and Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKM-E(Edans)-NH2 substrate [24]. The ebselen and six compounds (1–6) were dissolved in 0.5% DMSO/H2O with different concentrations (Table S3). The reaction mixture contained 92 μL of assay buffer, 5 μL of test compound solution, 1 μL of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, and 2 μL of the substrate in a black 96-well plate. After 10 min of incubation, the relative fluorescence unit (RFU) was read on a microplate reader (DU-730; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) at the excitation of 340 nm and the emission of 490 nm. The calculation formula for inhibition rate is consistent with the previous report [25].

2.6. Molecular docking studies

2.6.1. Preparation of protein and ligands

The three-dimensional structure of Mpro at 2.24 Å was downloaded from the protein data bank (PDB code 6LU7 http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/) [4]. Protein preparation wizard was performed in Mpro preparation using Maestro software (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2015), including missing side chains supplement, generating protonation states using Epik (pH: 7.0 ± 2.0), optimizing the structures using PROPKA (pH: 7.0), removing water beyond hets 3.0 Å, and restrained minimization by converging heavy atoms to RMSD 0.30 Å using OPLS (optimized potentials for liquid simulations) - 2005 atomic force field. The pre-treatments for energy minimization of ligands using MM2 force field of Chem3D 17.0. Subsequently, the ligprep modular of Maestro was used to prepare the ligands using the OPLS force field and Epik protonation (pH: 7.0 ± 2.0). All the compounds should generate absolute configuration.

2.6.2. Initial docking studies for 12 compounds

For initially docking, we used Autodock 4.2 software to evaluate the potential inhibition ability of the 12 compounds [1–6, EC-C, (−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate (EGC-pC), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin gallate (ECG), and (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)]. Autodock could evaluate their binding energy and inhibition constant based on the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA). The specific parameters had slight modification based on our previous method [20]. The pocket center of grid box was placed at (−11.2, 13.1, 70.2), and the axis was set at 50 × 55 × 50 Å with a grid point spacing of 0.375 Å. LGA runs were set at 100, combining with a population size of 150, an energy evaluation 25,000,000, and a maximum number of generations 27,000.

2.6.3. Induced fit docking (IFD)

IFD includes the Glide docking modular and Prime protein structure conformational optimization. Therefore, we further used IFD to study the highly dynamic interaction between 1 and Mpro. The Glide XP docking of catechins was performed to confirm the IFD box center, whose binding site was confirmed by SiteMap prediction (Fig. S2) and the N3 inhibitors attached in the PDB 6LU7 [4]. The ligands were flexible, twistable, and endowed with an energy of 2.5 kcal/mol. In the Glide docking part, we chose protein preparation constrained refinement, ligand, and receptor Van der Waals scaling were 0.50 Å. In the Prime refinement part, protein side chains were optimized by refining residues within 5.0 Å of ligand poses. Furthermore, we chose additional residues to refine for different compounds, presented in detail in the appendix (Table S4). In Glide redocking, structures were re-docked within 30.0 kcal/mol of the best using XP precision.

2.7. Molecular dynamics (MD) research

2.7.1. Binding pose metadynamics (BPMD)

After IFD studies, an automated, enhanced sampling, and metadynamics-based protocol method (BPMD) was further used to evaluate the stability of the complex [14]. Noteworthy, BPMD used the grand canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) to overcome the water sampling problem [26]. The collective variable (CV) is the measured value of RMSD of ligand heavy atoms concerning their starting position during ten independent metadynamics simulations of 10 ns [14]. The hill height and width were 0.05 kcal/mol and 0.02 Å, respectively. The RMSD calculation was performed by selecting 3 Å between protein residues and ligands. Before the metadynamics simulation, the system preparation in the SPC water box with minimized and constraining and slowly reached 300 K with the release. Then the last 0.5 ns of the unbiased MD simulation was used as the reference for metadynamics protocol. PoseScore, PersistenceScore (PersScore), and CompositeScore (CompScore) were used to judge the stability of the ligand during the simulations. PoseScore is the average RMSD from the starting pose. Comparing its initial hydrogen bond, PersScore is the average hydrogen bond persistent during the last 2 ns of 10 ns simulations. CompScore is the linear combination of PoseScore and PersScore, as follows: CompScore = PoseScore – 5 × PersScore [14]. Lower values of these three scores are symbolized the more stable complexes.

2.7.2. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

After BPMD simulations, we can get the more stable combing complex with lower CompScore, including protein and the optimized molecules. To further study the dynamic trajectory of the 1-Mpro, MD simulation was performed using the Desmond software package. OPLS-2005 potential energy forced field, and TIP4P solvent model were jointly used to establish the fluid environment. Meanwhile, salt (0.15 mol/L NaCl) and counter ions were added to make the solvent system isotonic and electrically neutral.

NVT (constant numbers of particles, volume, and temperature) and NPT (constant numbers of particles, pressure, and temperature) ensembles were used in MD simulation to heat and equilibrate the system. The first stage was heating: 1) NVT ensemble (Brownian dynamics) was executed, performing 100 ps MD simulation with the temperature at 10 K and energy in 50 kcal/mol to restrain the heavy atoms of solvent. NVT ensemble (Langevin) was executed, performing a 200 ps MD simulation with the same conditions. 2) NPT ensemble (Langevin) was performed, executing a 200 ps MD simulation with the temperature at 310 K, energy in 50 kcal/mol, and pressure at 1.01325 bar to heat the whole system under a restricted environment. The second stage was equilibration: under the conditions of constant temperature (310K) and pressure (1.01325 bar), two of 1 ns MD simulations were performed using an NPT ensemble, and the restrained energy was changed from 10 kcal/mol (first 1 ns) to 1.2 kcal/mol (second 1 ns). Then we conducted a 300 ns MD simulation with a 10 ps trajectory and continuous temperature (310 K), pressure (1.01325 bar), and energy (1.2 kcal/mol). All the MD simulations were run on RTX 3060 GPUs. The simulation interaction diagram tool could be used to generate the results of MD simulations.

2.8. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 software was used for the statistical analysis. All analytical experiments were repeated thrice, with values expressed as mean ± SD. The [Inhibitor] vs. normalized response – Variable slope method was used to analyze the extracellular data nonlinearly and produce the concentration-response curves.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Antioxidant activity

Excessive production of DPPH free radicals will accelerate the oxidation of lipids in food, so the ability to scavenge DPPH free radicals can become a standard for judging antioxidant activity [27]. Fig. S3 shows the DPPH free radical scavenging rate of VC and five ZHDB tea extracts (PE, EA, ME, DM, MW). The IC50 of VC, PE, EA, ME, DM, and MW were 1.14, 1.22, 1.39, 0.72, 4.68, and 0.71 μg/mL. In general, the extraction parts of ZHDB white tea were excellent. Interestingly, ME and MW extracts are superior to VC, and their chemical components could be further explored.

3.2. Identification of catechin derivatives

3.2.1. GNPS assisted identification of chemical constituents in the MW extracts of ZHDB tea

The molecular network (MN) of ZHDB tea was generated by GNPS platform, comprising 127 important separated components of MW extracts according to their MS2 spectral data similarity. The total MN contained 1746 mass spectral nodes. Combining the precise relative molecular weight, MS2 fragment ions, and TMDB database, we identified 33 compounds in the separated samples of ZHDB tea in the negative ion mode (Table 1 ). The primary clusters were common catechins and A-ring substituted catechin derivates (MN1), acylated flavonoid glycosides (MN2), proanthocyanidins (MN3), flavonoids (MN4), and catechin D-ring derivatives (MN5) (Fig. S4). The green and gray colors represent predicted and unknown compounds, respectively.

Table 1.

MS data of 36 identified compounds in ZHDB tea separated components.

| NO. | Group | [M − H]- (m/z) |

[M − H]- (m/z) |

Error |

Formula | MS2 Ions | Predicted compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured value | Theoretical value | (ppm) | |||||

| 1 | MN1 | 587.1200 | 587.1190 | 2.21 | C31H24O12 | 169.0142、193.0142、289.0719、341.0673、435.1092、534.1292 | Zijuan C; Zijuanin D |

| 2 | MN1 | 633.1250 | 633.1244 | 2.05 | C32H26O14 | 169.0147、193.0142、271.0601、303.0507、407.0792、447.0723、587.1161 | Zijuan A; Zijuanin B |

| 3 | MN1 | 457.0780 | 457.0771 | 1.97 | C22H18O11 | 125.0241、169.0146、193.0139、221.0469、269.0455、305.0666、331.0457 | EGCG |

| 4 | MN1 | 441.0821 | 441.0822 | 0.23 | C22H18O10 | 125.0246、169.0150、205.0501、271.0615、289.0724、311.0538、381.8415 | ECG |

| 5 | MN1 | 552.1511 | 552.1506 | 0.91 | C28H27NO11 | 125.0233、169.0139、236.0926、356.1493、400.1390、427.0644、508.1592 | Etc-pyrrolidinone E-J |

| 6 | MN1 | 568.1461 | 568.1455 | 1.06 | C20H27NO12 | 146.9660、169.0140、236.0926、289.0729、329.0574、416.1360、512.0597 | Ethylpyrrolidinonyl theasinensin A; Etc-pyrrolidinone A, B, D |

| 7 | MN1 | 515.0837 | 515.0826 | 2.14 | C14H20O13 | 125.0238、151.0045、169.0153、193.0140、245.0461、313.0370、331.0480、367.0452、408.9334、483.0572 | EGCGD |

| 8 | MN1 | 619.1474 | 619.1457 | 2.75 | C32H28O13 | 125.0252、169.0161、193.0157、271.0635、289.0744、341.0693、373.0953、435.1124、587.1225 | PSEC620 |

| 9 | MN1 | 635.1427 | 635.1406 | 3.31 | C32H28O4 | 125.0244、169.0142、245.0819、271.0612、305.0667、357.0616、389.0878、451.1035、483.1297、541.0988 | PSEC636 |

| 10 | MN2 | 1033.2791 | 1033.2825 | 3.29 | C47H54O26 | 145.0291、229.0488、285.0402、367.1236、451.1443、601.1976、747.2317、887.2434 | Camellikaempferoside C |

| 11 | MN2 | 1063.2902 | 1063.2931 | 2.73 | C48H56O27 | 145.0290、229.0504、285.1398、367.1224、451.1432、597.1775、747.2317、887.2412、1033.2799 | chakaflavonoside A |

| 12 | MN2 | 887.2270 | 887.2246 | 2.71 | C41H44O22 | 145.0290、229.0504、285.1398、433.1136、557.1276、615.1910、755.2021 | Quercetin 3-O-[α-l-arabinopyranosyl(1–3)][2-O''-(E)-p-coumaroyl][ α-l-rhamnopyranosyl(1–6)]- β-D-glucoside |

| 13 | MN2 | 1049.2801 | 1049.2774 | 2.57 | C47H54O27 | 145.0290、229.0509、301.0366、385.8111、451.1463、585.2141、639.6268、735.1794、903.2420 | Quercetin 3-O-(2G-p-coumaroyl-3G-O-β-l-arabinosyl-3α-O-β-d-glucosylrutinoside |

| 14 | MN2 | 447.0909 | 447.0927 | 4.03 | C21H20O11 | 151.0037、213.0549、241.0506、257.0458、285.0404、327.0477、369.2175 | Astragalin |

| 15 | MN2 | 917.2342 | 917.2352 | 1.09 | C42H46O23 | 145.0297、229.0258、301.0352、433.1130、493.0941、615.1925、737.1941 | Quercetin 3-O-[2-O''-(E)-p-coumaroyl][ β-d-glucopyranosyl(1–3)-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl(1–6)]-β-D-glucoside; quamoreokchaside I |

| 16 | MN2 | 901.2386 | 901.2402 | 1.78 | C42H46O22 | 145.0300、229.0499、285.0410、433.1144、615.1923、701.1641、755.2041 | Kaempferol-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-(p-coumaroyl) glucoside |

| 17 | MN2 | 871.2292 | 871.2297 | 0.57 | C41H44O21 | 145.0296、229.0509、285.0418、351.0532、453.1147、585.1825、741.1878 | Camellikaempferoside A |

| 18 | MN2 | 609.1443 | 609.1456 | 2.13 | C27H30O16 | 146.9662、208.9363、245.0821、285.0404、315.0870、404.0870、455.1188 | Camelliaside C |

| 19 | MN2 | 463.0877 | 463.0877 | 0 | C21H20O12 | 125.0231、177.0186、271.0236、300.0260、301.0318、327.0447、357.0598、407.0740 | Isoquercitrin, Hirsutrin |

| 20 | MN2 | 1079.2878 | 1079.288 | 0.19 | C48H56O28 | 145.0265、301.0354、447.0957、513.0209、597.1832、775.1679、885.2296、1049.2270 | Quercetin 3-O-[2G-(E)-coumaroyl-3G-O-β-d-glucosyl-3R-O-β-d-glucosylrutinoside] |

| 21 | MN3 | 897.1523 | 897.1514 | 1 | C44H34O21 | 169.0143、289.0713、423.0712、557.1089、727.1306、802.2307、849.1636 | ECG-(4β → 6)-EGCG; EGCG-(4β → 6)-ECG |

| 22 | MN3 | 865.1619 | 865.1616 | 0.35 | C44H34O19 | 169.0141、271.0609、423.0733、525.1199、543.1299、695.1428、713.1514 | 3,3′-Bis(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyl)Epiafzelechin(4–6)epicatechin; 3,3′-Bis(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoyl)Epiafzelechin(4–8)epicatechin |

| 23 | MN3 | 881.1555 | 881.1565 | 1.13 | C44H34O20 | 169.0140、271.0605、379。0800、445.0547、559.1278、729.1465、767.1117 | Procyanidin B5 3,3′-di-O-gallate. 3,3′-Di-O-galloylprocyanidin B5, ECG-(4β → 6)-ECG; EAG-(4β → 6)-EGCG |

| 24 | MN3 | 287.0556 | 287.0556 | 0 | C15H12O6 | 109.0293、123.0085、151.0397、175.0386、221.0812、245.0812 | Dihydrokaempferol |

| 25 | MN3 | 269.0460 | 269.0450 | 3.71 | C15H10O5 | 109.0302、151.0415、179.0364、221.0827、245.0836 | Apigenin |

| 26 | MN4 | 289.0722 | 289.0712 | 3.46 | C15H14O6 | 109.0302、125.0255、151.0422、179.0367、203.0731、221.0828、245.0835、271.0604 | (−)-Epicatechin (EC) |

| 27 | MN4 | 271.0610 | 271.0606 | 1.48 | C15H12O5 | 109.0297、125.0246、164.0118、179.0353、245.0822、271.0588 | Naringenin |

| 28 | MN4 | 409.0921 | 409.0923 | 0.49 | C22H18O8 | 109.0298、125.0229、221.0821、245.0807、256.0372、289.0691、311.0539、379.9664 | 3-(4-Hydroxybenzoyl)epicatechin |

| 29 | MN4 | 305.0671 | 305.0661 | 2.74 | C15H14O7 | 112.9855、137.0246、165.0194、191.9470、219.0669、241.0465、275.9850 | Epigallocatechin (EGC) |

| 30 | MN5 | 455.0999 | 455.0978 | 4.61 | C23H20O10 | 169.0145、183.0312、245.0829、271.0631、289.0729、305.0697、357.0631、402.8034 | 3′-O-methyl-(−)-epicatechin gallate, ECG3′Me; 3-O-(3-O-Methylgalloyl)epicatechin |

| 31 | MN5 | 471.0925 | 471.0927 | 0.42 | C23H20O11 | 169.0143、215.0719、289.0718、301.0717、323.0524、411.1590、451.3311 | 3′-O-methyl-(−)-epigallocatechin gallate, EGCG3′Me; 3-O-(3-O-Methylgalloyl)epigallocatechin; |

| 32 | MN5 | 467.0999 | 467.0978 | 4.49 | C24H20O10 | 169.0149、225.0555、287.0575、301.0345、333.0615、407.0789、435.0731、463.0690 | Epigallocatechin 3-O-caffeate |

| 33 | MN5 | 451.1043 | 451.1029 | 3.1 | C24H20O9 | 125.0244、137.0243、179.0352、225.0519、245.0820、289.0714、341.0613、377.0557 | 3-O-(E)-p-Coumaroylepigallocatechin; Epicatechin 3-O-caffeate |

Figs. S5–6 show the important cluster MN1, including common catechins (EGCG, ECG), flavoalkaloids (Etc-pyrrolidinone E-J, Etc-pyrrolidinone A, B, D), and PSECs (Zijuan A-D, PSEC620). Interestingly, the compound with m/z 635.1427 [M − H]−, whose node was closely linked to EGCG, ECG, and PSEC620, was further separated and clarified as a new PSEC (see the next section for details). In the previous study, researchers find and further purify the new neolignan glycosides by analyzing the molecular networking of separated components of Huangjinya green tea extract [28]. We also analyzed and listed the clusters and compounds of the molecular network MN2-5 in detail (Figs. S7–14). With the help of the reference compounds in TMDB database, m/z 467.0999 and 451.1043 in MN5 cluster were predicted as EGC-C and EC-C, respectively. Moreover, they are also HCCs and are the basis for our subsequent semi-synthesis (the details were presented in the next section).

3.2.2. Identification and detection of 1 from green tea

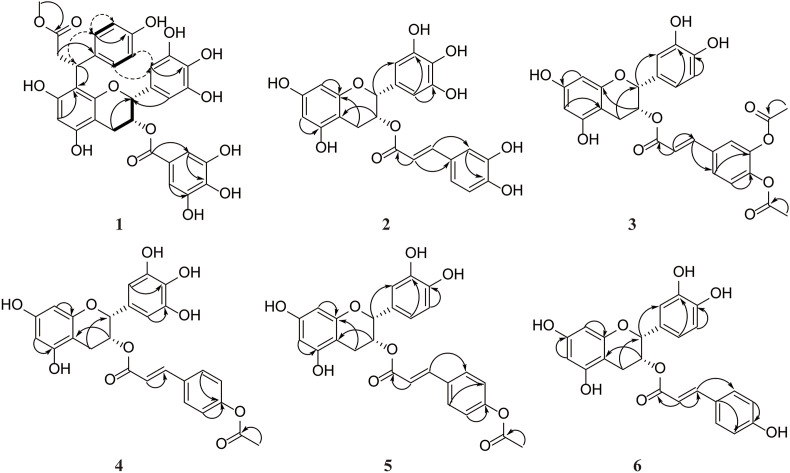

The methanol-aqueous extract of ZHDB was subjected to repeated column chromatography (CC) and semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to obtain 1 (Fig. 1 ). Compound 1 was white amorphous powder, = −170 (c 0.01, acetonitrile). The molecular formula is C32H28O14 (unsaturation degrees: 19), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 635.1427 (calcd for C32H27O14 −: 635.1406) and nuclear magnetic spectrum (NMR). Fig. S15 shows that 1 has more than 95% purity with the characteristic phenolic UV spectrum (207 & 275 nm). The Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum shows the primary functional group information, including hydroxyl groups (3424 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1731 cm−1), and benzene ring (1513, and 1617 cm−1) (Fig. S16). Meanwhile, 1 has the apparent MS/MS fragments of EGCG moiety (Fig. S17) m/z: 125.0251 [M − H]− (A ring), 169.0154 [M − H]− (gallic acid ester of D ring), and 305.0688 [M − H]− (epigallocatechin, EGC).

Fig. 1.

The structures of 1−6, (−)-epicatechin 3-O-caffeoate (EC-C), (−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate (EGC-pC), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin 3-O-gallate (ECG), and (−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-gallate (EGCG).

Table 2 shows the 1H [500 MHz, dimethyl-d6 sulfoxide (DMSO-d 6)] and 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d 6) data for 1 and PSEC620 (which has a molecular weight of 620, thus got the abbreviated name PSEC620) [23]. Fig. 2 shows the 1H–1H COSY, HMBC, and ROESY correlations of 1. Above spectra are placed in Figs. S18–25. Accordingly, we deduced that 1 is a PSEC [23]. The representative signals of the C-ring can be easily found in the NMR spectrum of 1 (Fig. S18) at C-2 (δ H 4.94, δ C 76.9), C-3 (δ H 5.32, δ C 68.2), C-4 (δ H 2.67/2.94, δ C 26.2), whose connection relationship can be further defined as –CH–CH–CH2– via 1H–1H COSY (Fig. S19). Two pairs of characteristic proton signals δ H 6.45 (H-2′ & H-6′) and δ H 6.85 (H-3′′ & H-7″) corresponded with the typical pyrogallol B and D-rings of EGCG, respectively. According to the HMQC (Fig. S23), we can determine the corresponding carbon signals of the hydrogens on the B and D ring of the EGCG moiety at C-2′/C-6′ (δ C 105.6) and C-2′′/C-6′′ (δ C 108.9).

Table 2.

NMR data of 1 and PSEC620 (δ in ppm).

| No. | 1 |

PSEC620 [23] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J, Hz) | δC type | HMBC (1H to13C) | δH (J, Hz) | δC type | |

| 2 | 4.94 s | 76.9 | C-3, 4, 9, 1′, 2′ | 4.99 s | 77.0 |

| 3 | 5.32 s | 68.2 | C-4 | 5.30 br s | 68.6 |

| 4α | 2.67 m | 26.2 | C-2, 3, 5, 8 | 2.67 d (16.8) | 26.4 |

| 4β | 2.94 dd (16.5, 5.0) | C-9 | 2.93 dd (16.8, 4.7) | ||

| 5 | 154.1 | 154.5 | |||

| 6 | 5.98 s | 95.7 | C-5, 8, 10 | 5.97 s | 96.2 |

| 7 | 154.1 | 154.5 | |||

| 8 | 97.8 | 108.8 | |||

| 9 | 155.0 | 155.4 | |||

| 10 | 108.4 | 97.9 | |||

| 1′ | 129.0 | 130.1 | |||

| 2′ | 6.45 s | 105.6 | C-2, 3′, 4′, 6′ | 6.85 d (1.8) | 114.5 |

| 3′ | 145.8 | 145.1 | |||

| 4′ | 132.4 | 145 | |||

| 5′ | 145.8 | 6.62 d (8.2) | 115.5 | ||

| 6′ | 6.45 s | 105.6 | C-2, 2′, 4′, 5′ | 6.69 dd (8.2, 1.8) | 117.8 |

| 1″ | 119.4 | 119.2 | |||

| 2″ | 6.85 s | 108.9 | C-1″, 3″, 4″, 6″, 7″ | 6.80 s | 109.2 |

| 3″ | 145.5 | 145.9 | |||

| 4″ | 139.0 | 139.2 | |||

| 5″ | 145.5 | 145.9 | |||

| 6″ | 6.85 s | 108.9 | C-1″, 2″, 4″, 5″, 7″ | 6.80 s | 109.2 |

| 7″ | 165.5 | 165.7 | |||

| 1‴ | 135.2 | 135.6 | |||

| 2‴ | 7.14 d (7.5) | 128.5 | C-3‴, 4‴ | 7.09 d (7.3) | 128.8 |

| 3‴ | 6.63 d (8.5) | 115.4 | C-5‴ | 6.62 d (7.3) | 115.1 |

| 4‴ | 155.0 | 155.4 | |||

| 5‴ | 6.63 d (8.5) | 114.7 | C-3‴, | 6.62 d (7.3) | 115.1 |

| 6‴ | 7.14 d (7.5) | 128.5 | C-4‴, 5‴ | 7.09 d (7.3) | 128.8 |

| 7‴ | 4.90 s | 32.8 | C-8, 1‴, 9‴ | 4.88 d (7.5) | 35.8 |

| 8‴ | 3.08 dd (15.5, 8.0) | 37.0 | C-1‴, 7‴, 9‴ | 3.00 dd (14.4, 7.5) | 33.5 |

| 2.84 d (15.5) | C-7‴ | 2.82 d (14.4) | |||

| 9‴ | 172.9 | 173.3 | |||

| OMe | 3.49 s | 50.8 | C-9''' | 3.46 s | 51.4 |

1H NMR was recorded at 500 MHz in DMSO-d6, and 13C NMR was recorded at 125 MHz in DMSO-d6. (s, single peak; d, double peak; t, triple peak; m, multiple peaks).

Fig. 2.

Key 2D NMR correlations of 1−6. [1H–1H COSY (heavy solid line), ROESY (dashed double ar line), and HMBC (solid single ar line)].

Interestingly, only one proton signal existed in the A-ring (δ H 5.98), indicating that 1 has a substituent at C-6 or C-8. Meanwhile, the apparent methoxy signal (δ H 3.49) was found through the 1H NMR (Fig. S18), whose carbon signal was determined at 50.8 ppm through the HMQC (Fig. S23). Furthermore, the aromatic methyl ester signal could be defined through the HMBC correlations, including methoxy signal (δ H 3.49) to C-9‴ (δ C 172.9), H-8‴ (δ H 3.08) to C-1‴ (δ C 135.2), H-2‴ and H-6‴ (δ H 7.14) to C-4‴ (δ C 155.0). The ROESY spectrum (Fig. S20) shows the correlation between δ H 6.45 (H-2′) & δ H 6.63 (H-5‴), δ H 4.90 (H-7‴) & δ H 7.14 (H-2‴ & H-6‴), and δ H 7.14 (H-6‴) & δ H 6.45 (H-2′). Hence, this aromatic methyl ester was substituted in position 8 with 7‴R. Besides, the CD of 1 (Fig. S26) is consistent with that of PSEC620 (2R, 3R, 7‴R) [23]. Therefore, the absolute configuration of 1 was finally determined as 2R, 3R, 7‴R. Compound 1 was named PSEC636.

Table S5 shows the qualitative results of 1 in 18 green tea samples. Compound 1 was detected in 14 of the 18 green tea products, especially in Zijuan and Zimudan with the strongest response. We previously reported four PSECs, Zijuanins A-D, from Zijuan green tea [17].

3.2.3. Identification of catechin derivatives 2–6

With the help of repeated CC, we purified the synthetic product (residues) and got 2 (EGC-C), 3 (EC-CDA), 4 (EGC-pCA), 5 (EC-pCA), and 6 (EC-pC) (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 shows the HMBC correlations of 2–6. Table 3 shows the 1H (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6) and 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6) data of 2–6. Fig. S27 shows the CD spectra of 2–6.

Table 3.

NMR data of compounds 2–6.

| No. | 2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J, Hz) | δC type | δH (J, Hz) | δC type | HMBC (1H to13C) | δH (J, Hz) | δC type | HMBC (1H to13C) | δH (J, Hz) | δC type | HMBC (1H to13C) | δH (J, Hz) | δC type | |

| 2 | 4.93 s | 76.3 | 5.02 s | 76.2 | C-3, 4, 1′, 2′, 6′ | 4.95 s | 76.2 | C-3, 1′,2′ | 5.02 s | 76.2 | C-3, 1′, 2′, 6′ | 5.01 s | 76.3 |

| 3 | 5.28 s | 67.9 | 5.36 s | 68.2 | C-10, 9″ | 5.34 s | 68.2 | C-10 | 5.36 s | 68.2 | C-10 | 5.34 s | 67.8 |

| 4α | 2.66 d (17.4) | 25.4 | 2.66 d (17.4) | 25.4 | C-2, 3, 5, 9, 10, | 2.68 d (16.8) | 25.4 | C-2, 3, 9, 10 | 2.70 d (16.8) | 25.5 | C-2, 3, 10 | 2.69 d (17.4) | 25.5 |

| 4β | 2.92 dd (17.4, 4.2) | 2.94 dd (17.4, 4.2) | C-5, 9, 10 | 2.96 dd (17.4, 4.2) | 2.97 dd (17.4, 4.2) | C-10 | 2.95 d (17.4) | ||||||

| 5 | 155.4 | 155.4 | 155.4 | 155.4 | 155.5 | ||||||||

| 6 | 5.79 s | 94.2 | 5.79 s | 94.3 | C-5, 7, 10 | 5.80 s | 94.2 | C-7, 9, 10 | 5.80 s | 94.3 | C-7, 8 | 5.81 s | 94.3 |

| 7 | 156.5 | 156.4 | 156.4 | 156.4 | 156.4 | ||||||||

| 8 | 5.93 s | 95.5 | 5.94 s | 95.5 | C-6, 7, 9, 10 | 5.94 s | 95.5 | C-6, 7, 9, 10 | 5.94 s | 95.5 | C-6, 9, 10 | 5.95 s | 95.5 |

| 9 | 156.5 | 156.5 | 156.5 | 156.5 | 156.6 | ||||||||

| 10 | 97.3 | 97.1 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.3 | ||||||||

| 1' | 128.5 | 129.1 | 129.6 | 129.6 | 129.3 | ||||||||

| 2' | 6.39 s | 105.5 | 6.85 s | 114.1 | C-2, 1′, 3′, 6′ | 6.41 s | 105.5 | C-2, 3′, 4′, 6′ | 6.89 s | 115.0 | C-2, 3′, 4′, 6′ | 6.90 s | 115.1 |

| 3' | 145.4 | 144.7 | 145.6 | 144.7 | 144.7 | ||||||||

| 4' | 132.3 | 144.7 | 132.3 | 144.7 | 144.7 | ||||||||

| 5' | 145.4 | 6.67 d (8.4) | 115.1 | C-1′, 2′, 4′ | 145.6 | 6.67 d (10.2) | 115.6 | C-1′, 2′, 3′, 4′ | 6.68 d (7.8) | 115.7 | |||

| 6' | 6.39 s | 105.5 | 6.71 dd (10.2, 1.8) | 117.5 | C-2, 2′, 4′ | 6.41 s | 105.5 | C-2, 2′, 4′, 5′ | 6.71 m | 117.5 | C-1′, 2′, 3′, 4′ | 6.70 d (5.4) | 117.5 |

| 1'' | 125.4 | 126.9 | 125.0 | 124.9 | 124.9 | ||||||||

| 2'' | 6.98 d (2.4) | 115.0 | 7.62 dd (10.2, 1.8) | 123.1 | C-4′, 6′ | 7.72 s | 130.2 | C-3″, 4″, 5″, 6″, 7″ | 7.72 s | 130.3 | C-6″, 7″ | 7.50 s | 130.3 |

| 3'' | 145.6 | 142.2 | 7.16 s | 122.2 | C-2″,4″, 5″, 6″ | 7.14 s | 122.2 | C-2″, 6″ | 6.75 s | 115.7 | |||

| 4'' | 148.3 | 143.5 | 151.9 | 159.8 | 160.0 | ||||||||

| 5'' | 6.73 d (7.8) | 115.6 | 7.27 d (8.4) | 118.9 | C-3″, 4″ | 7.18 s | 122.2 | C-2″, 3″, 4″, 6″ | 7.15 s | 122.2 | C-2″, 6″ | 6.76 s | 115.7 |

| 6'' | 6.96 dd (10.2, 1.8) | 121.2 | 7.69 d (1.8) | 123.9 | C-1″, 7″ | 7.74 s | 130.2 | C-2″, 3″, 4″, 5″, 7″ | 7.74 s | 130.3 | C-2″, 7″ | 7.51 s | 130.3 |

| 7'' | 7.33 d (15.6) | 145.4 | 7.50 d (16.2) | 143.0 | C-1″, 2″, 9″ | 7.51 d (16.2) | 143.7 | C-8″, 2″, 6″, 9″ | 7.51 d (16.2) | 145.0 | C-2″, 6″, 9″ | 7.43 d (15.6) | 145.0 |

| 8'' | 6.08 d (18.0) | 113.8 | 6.53 d (15.6) | 114.2 | C-7″, 9″ | 6.48 d (16.2) | 118.0 | C-2″, 6″, 9''; 4″-Carbonyl carbon | 6.49 d (16.2) | 117.9 | C-2″, 6″, 9″ | 6.27 d (15.6) | 114.2 |

| 9'' | 165.8 | 165.3 | 165.5 | 165.5 | 166.0 | ||||||||

| 3″-OAC | 167.9 | ||||||||||||

| 2.25 | 20.2 | 3″-Carbonyl carbon | |||||||||||

| 4″-OAC | 168.0 | 168.8 | 168.8 | ||||||||||

| 2.25 | 20.3 | 4″-Carbonyl carbon | 2.27 | 20.7 | 4″-Carbonyl carbon | 2.26 | 20.8 | 4″-Carbonyl carbon | |||||

1H NMR was recorded at 600 MHz in DMSO-d6, and 13C NMR was recorded at 150 MHz in DMSO-d6. (s, single peak; d, double peak; t, triple peak; m, multiple peaks).

Compound 2: EGC-C was white amorphous powder with 60% yield (6 mg), = −310 (c 0.01, acetonitrile). The molecular formula is C24H20O10 (unsaturation degrees: 15), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 467.0964 (calcd for C24H19O10 −: 467.0984) (Fig. S28). The FT-IR spectrum shows the hydroxyl groups (3416 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1731 cm−1), and double bonds (1522 and 1630 cm−1) (Fig. S29). The 1H, 13C, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra of 2 are shown in the attachment (Figs. S30–34). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 2.66 [1H, d, J = 17.4 Hz, H–C (4α)], 2.92 [1H, dd, J = 17.4, 4.2 Hz, H–C (4β)], 4.93 [1H, s, H–C (2)], 5.28 [1H, s, H–C (3)], 5.79 [1H, s, H–C (6)], 5.93 [1H, s, H–C (8)], 6.08 [1H, d, J = 18.0 Hz, H–C (8″)], 6.39 [1H, s, H–C (2′/6′)], 6.73 [1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H–C (5″)], 6.96 [1H, dd, J = 10.2, 1.8 Hz, H–C (6″)], 6.98 [1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H–C (2″)], 7.33 [1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H–C (7″)] (Fig. S30). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 25.4 [C-4], 67.9 [C-3], 76.3 [C-2], 94.2 [C-6], 95.5 [C-8], 97.3 [C-10], 105.5 [C-2′/6′], 113.8 [C-8′′], 115.0 [C-2′′], 115.6 [C-5′′], 121.2 [C-6′′], 125.4 [C-1′′], 128.5 [C-1′], 132.3 [C-4′], 145.4 [C-3′/5′/7′′], 145.6 [C-3′′], 148.3 [C-4′′], 155.4 [C-5], 156.5 [C-7/9], 165.8 [C-9′′] (Fig. S31). The NMR data confirmed the structure of EGC-C compared with the data from the previous report [29].

Compound 3: 3″, 4″-diacetylated EC-C (EC-CDA) was white amorphous powder with 76% yield (10 mg), = −420 (c 0.01, acetonitrile). The molecular formula is C28H24O11 (unsaturation degrees: 17), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 535.1224 (calcd for C28H23O11 −: 535.1246) (Fig. S35). The FT-IR spectrum shows the hydroxyl groups (3397 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1767 cm−1), and double bonds (1518 and 1630 cm−1) (Fig. S36). The 1H, 13C, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra of 3 are shown in the attachment (Figs. S37–42). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 2.25 [6H, m, H–C (3″-Carbonyl carbon/4″-Carbonyl carbon)], 2.66 [1H, d, J = 17.4 Hz, H–C (4α)], 2.94 [1H, dd, J = 17.4, 4.2 Hz, H–C (4β)], 5.02 [1H, s, H–C (2)], 5.36 [1H, s, H–C (3)], 5.79 [1H, s, H–C (6)], 5.94 [1H, s, H–C (8)], 6.53 [1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H–C (8″)], 6.67 [1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H–C (5′)], 6.71 [1H, dd, J = 10.2, 1.8 Hz, H–C (6′)], 6.85 [1H, s, H–C (2′)], 7.27 [1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H–C (5″)], 7.50 [1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H–C (7″)], 7.62 [1H, dd, J = 10.2, 1.8 Hz, H–C (2″)], 7.69 [1H, d, J = 1.8 Hz, H–C (6″)] (Fig. S37). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 20.2 [3″-Carbonyl carbon], 20.3 [4″-Carbonyl carbon], 25.4 [C-4], 68.2 [C-3], 76.2 [C-2], 94.3 [C-6], 95.5 [C-8], 97.1 [C-10], 114.1 [C-2′], 114.2 [C-8′′], 115.1 [C-5′], 117.5 [C-6′], 118.9 [C-5′′], 123.1 [C-2′′], 123.9 [C-1′′], 126.9 [C-1′′], 129.1 [C-1′], 142.2 [C-3′′], 143.0 [C-7′′], 143.5 [C-4′′], 144.7 [C-3′/4′], 155.4 [C-5], 156.4 [C-7], 156.5 [C-9], 165.3 [C-9′′], 167.9 [3″-Carbonyl carbon], 168.0 [4″-Carbonyl carbon] (Fig. S38). The NMR data confirmed the structure of the synthetic new EC-CDA compared with those data of EC-C [19].

Compound 4: EGC-pCA was white amorphous powder with 60% yield (15 mg), = −380 (c 0.01, acetonitrile). The molecular formula was C26H22O10 (unsaturation degrees: 16), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 493.1117 (calcd for C26H21O10 −: 493.1140) (Fig. S43). The FT-IR spectrum shows the hydroxyl groups (3416 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1731 cm−1), and double bonds (1513 and 1630 cm−1) (Fig. S44). The 1H, 13C, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra of 4 are shown in the attachment (Figs. S45–49). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 2.27 [3H, m, H–C (4″-Carbonyl carbon)], 2.68 [1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, H–C (4α)], 2.96 [1H, dd, J = 17.4, 4.2 Hz, H–C (4β)], 4.95 [1H, s, H–C (2)], 5.34 [1H, s, H–C (3)], 5.80 [1H, s, H–C (6)], 5.94 [1H, s, H–C (8)], 6.41 [2H, s, H–C (2'/6′)], 6.48 [1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H–C (8″)], 7.16 [1H, s, H–C (3″)], 7.18 [1H, s, H–C (5″)], 7.51 [1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H–C (7″)], 7.72 [1H, s, H–C (2″)], 7.74 [1H, s, H–C (6″)] (Fig. S45). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 20.7 [4″-Carbonyl carbon], 25.4 [C-4], 68.2 [C-3], 76.2 [C-2], 94.2 [C-6], 95.5 [C-8], 97.2 [C-10], 105.5 [C-2′/6′], 118.0 [C-8′′], 122.2 [C-3′′/5′′], 125.0 [C-1′′], 129.6 [C-1′], 130.2 [C-2′′/6′′], 132.3 [C-4′], 143.7 [C-7′′], 145.6 [C-3′/5′], 151.9 [C-4′′], 155.4 [C-5], 156.4 [C-7], 156.5 [C-9], 165.5 [C-9′′], 168.8 [4″-Carbonyl carbon] (Fig. S46). The NMR data confirmed the structure of the synthetic new 4″-acetylated EGC-pC compared with the data of EGC-pC [19].

Compound 5: EC-pCA was white amorphous powder with 85% (5 mg), = −300 (c 0.01, acetonitrile). The molecular formula is C26H22O9 (unsaturation degrees: 16), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 477.1171 (calcd for C26H21O9 −: 477.1191) (Fig. S50). The FTIR spectrum shows the hydroxyl groups (3412 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1766 cm−1), and double bonds (1515, 1605, and 1632 cm−1) (Fig. S51). The 1H, 13C, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra of 5 are shown in the attachment (Figs. S52–56). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 2.26 [3H, m, H–C (4″-Carbonyl carbon)], 2.70 [1H, d, J = 16.8 Hz, H–C (4α)], 2.97 [1H, dd, J = 17.4, 4.2 Hz, H–C (4β)], 5.02 [1H, s, H–C (2)], 5.36 [1H, s, H–C (3)], 5.80 [1H, s, H–C (6)], 5.94 [1H, s, H–C (8)], 6.49 [1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H–C (8″)], 6.67 [1H, d, J = 10.2 Hz, H–C (5′)], 6.71 [1H, m, H–C (6′)], 6.89 [1H, s, H–C (2′)], 7.14 [1H, s, H–C (3″)], 7.15 [1H, s, H–C (5″)], 7.51 [1H, d, J = 16.2 Hz, H–C (7″)], 7.72 [1H, s, H–C (2″)], 7.74 [1H, s, H–C (6″)] (Fig. S52). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 20.8 [4″-Carbonyl carbon], 25.5 [C-4], 68.2 [C-3], 76.2 [C-2], 94.3 [C-6], 95.5 [C-8], 97.2 [C-10], 115.0 [C-2′], 115.6 [C-5′], 117.5 [C-6′], 117.9 [C-8′′], 122.2 [C-3′′/5′′], 124.9 [C-1′′], 129.6 [C-1′], 130.3 [C-2′′/6′′], 144.7 [C-3′/4′], 145.0 [C-7′′], 155.4 [C-5], 156.4 [C-7], 156.5 [C-9], 159.8 [C-4′′], 165.5 [C-9′′], 168.8 [4″-Carbonyl carbon] (Fig. S53). The NMR data confirmed the structure of the synthetic new 4″-acetylated EC-pC compared with the data of EC-pC [30].

Compound 6: EC-pC was white amorphous powder with 88% yield (16 mg), = −3530 (c 0.01, acetonitrile), The molecular formula is C24H20O8 (unsaturation degrees: 15), deduced from the negative ESI-HR-MS m/z 435.1060 (calcd for C24H19O8 −: 435.1085) (Fig. S57). The FTIR spectrum shows the hydroxyl groups (3424 cm−1), carbonyl groups (1685 cm−1), and double bonds (1515, 1605, and 1630 cm−1) (Fig. S58). The 1H, 13C, HSQC, and HMBC NMR spectra of 6 are shown in the attachment (Figs. S59–63). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 2.69 [1H, d, J = 17.4 Hz, H–C (4α)], 2.95 [1H, d, J = 17.4 Hz, H–C (4β)], 5.01 [1H, s, H–C (2)], 5.34 [1H, s, H–C (3)], 5.81 [1H, s, H–C (6)], 5.95 [1H, s, H–C (8)], 6.27 [1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H–C (8″)], 6.68 [1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H–C (5′)], 6.70 [1H, d, J = 5.4 Hz, H–C (6′)], 6.75 [1H, s, H–C (3″)], 6.76 [1H, s, H–C (5″)], 6.90 [1H, s, H–C (2′)], 7.43 [1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H–C (7″)], 7.50 [1H, s, H–C (2″)], 7.51 [1H, s, H–C (6″)] (Fig. S59). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ 25.5 [C-4], 67.8 [C-3], 76.3 [C-2], 94.3 [C-6], 95.5 [C-8], 97.3 [C-10], 114.2 [C-8′′], 115.1 [C-2′], 115.7 [C-5′/3′′/5′′], 117.5 [C-6′], 124.9 [C-1′′], 129.3 [C-1′], 130.3 [C-2′′/6′′], 144.7 [C-3′/4′], 145.0 [C-7′′], 155.5 [C-5], 156.4 [C-7], 156.6 [C-9], 160.0 [C-4′′], 166.0 [C-9′′] (Fig. S60). The NMR data confirmed the structure of synthetic EC-pC compared with the previous report [30].

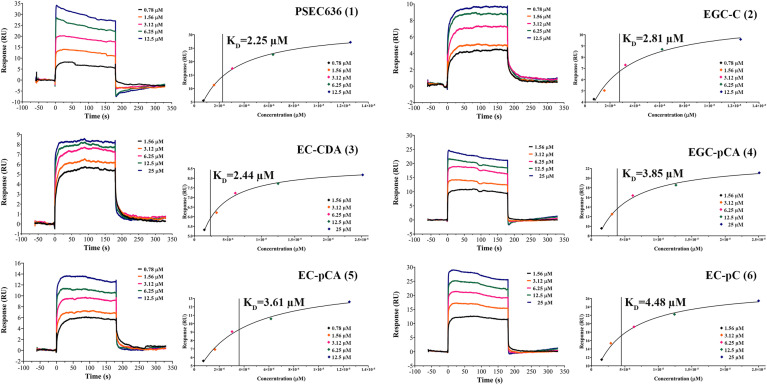

3.3. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

SPR is an efficient approach for drug discovery. Hou et al. used SPR to evaluate the antiviral activity of novel phloroglucinol-terpenoid against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [8]. We assessed the direct binding affinities between the 12 catechin derivatives and Mpro by analyzing their equilibrium dissociation constants (KD). The Langmuir binding isotherm model was used to fit the SPR sensorgrams to provide the steady-state SPR signal nonlinearly. Plot five concentration gradients for each analyte using the response values at equilibrium. Rmax and offset are the maximum and minimum response values, respectively. The fitting efficiency is calculated by the Chi2 value [20]. Fig. 3 shows that 1–6 have low KD values (all below 5 μM), suggesting that they all have a strong binding affinity with Mpro. The KD values were 2.25 μM for 1, 2.81 μM for EGC-C (2), 2.44 μM for EC-CDA (3), 3,85 μM for EGC-pCA (4), 3.61 μM for EC-pCA (5), and 4.48 μM for EC-pC (6). The lower calculated Chi2 value indicates an excellent fitting accuracy (Table S6).

Fig. 3.

SPR Sensorgrams for 1 (0.78–12.5 μM), 2 (0.78–12.5 μM), 3 (1.56–25 μM), 4 (1.56–25 μM), 5 (0.78–12.5 μM), 6 (1.56–25 μM) characterizing their direct binding capacity with the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro protein.

EGCG could block virus infection by binding with receptor-binding domain (RBD) and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [31]. The binding affinities of epicatechin (EC) (KD = 23.91 μM) and EGC (KD = 11.22 μM) is weaker than those of epicatechin gallate (ECG) (KD = 16.02 μM) and EGCG (KD = 6.16 μM) (Fig. S64), indicating that the galloyl substitution is essential for inhibition [32]. The binding affinity of 1 (KD = 2.25 μM) is better than that of EGCG, suggesting that the phenylpropanoid substitution at the A ring enhances the activity. The binding affinity of EC is significantly weaker than EGC, and EC-C (KD = 3.60 μM) is stronger than EC-pC, suggesting that an additional hydroxyl group on the B ring enhances the binding capacity as the previous report [33]. The below binding ability sequences: EGC-C and EGC-pC > EGCG, EC-C and EC-pC > ECG decide that different hydroxycinnamoyl group substitutions further enhance the binding, which is stronger than galloyl substitution at 3-OH. The binding affinity of 2 is better than EGC-pC (KD = 4.28 μM), and EC-C is stronger than 6, showing that one more hydroxyl group at the cinnamoyl aromatic ring also enhances the binding ability [20]. We analyzed the results and found that the hydroxyl group played an important role. In previous studies, many hydroxyl-related inhibitors have been found, including 10-hydroxyaloin A and iso-quercetin [34]. However, comparing the binding abilities of 3, 4, and 5 (all acetylated ones) with those of EC-C, EGC-pC, and 6, we can see that acetyl group substitution at the cinnamoyl benzene ring can also enhance the binding.

3.4. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition by catechin derivatives

As previously reported, a FRET protease assay was applied to measure the proteolytic activity of the recombinant Mpro on a fluorescently labeled substrate, Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans [24]. In this study, we used this FRET-based protease assay to measure the inhibitory activities of six catechin derivatives against Mpro. The IC50 of ebselen was 1.17 ± 0.04 μM (Fig. S65) in the present study, corresponding with the normal concentration range of the P0312 kit (0.5–2 μM). The IC50 values for 1, EGC-C (2), EC-CDA (3), EGC-pCA (4), EC-pCA (5), and EC-pC (6) were 5.95 ± 0.17, 9.09 ± 0.22, 23.10 ± 0.69, 31.97 ± 0.15, 77.47 ± 1.19, and 210.80 ± 2.39 μM, respectively (Fig. 4 ). From the above results, 1–4 were promising compounds with strong inhibition (all below 50 μM). It is worth noting that the inhibitory activity of 1 was the best with the lowest IC50 value, improving the bioactive significance of PSECs compared with the previous study [23]. Moreover, the inhibitory activity of 5 was significantly better than 6, indicating that the acetyl group on the substituted cinnamyl aromatic ring may play an essential role in active modification. Previous studies also suggest that acetyl modification on phenolic compounds could increase antithrombotic activity [35].

Fig. 4.

Inhibitory activity profiles of 1–6 against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Liang et al. have discovered the aspulvinone analogs as the potential inhibitors using a beyotime enhanced inhibition kit. The IC50 values of aspulvinones D, M, and R are 10.3 ± 0.6, 9.4 ± 0.6, and 7.7 ± 0.6 μM, respectively [25]. In the previous reports, the IC50 of ebselen was different from different reports such as 0.67 ± 0.09 μM [4] and 0.04 ± 0.004 μM [20]. Therefore, based on the different kit conditions used by the researchers, we used ebselen as a positive control to observe the fold difference between different compounds and ebselen. Herein, the inhibitory activity of compounds 1 (IC50 = 5.1 × ebselen), 2 (IC50 = 7.8 × ebselen), 3 (IC50 = 19.7 × ebselen), and 4 (IC50 = 27.3 × ebselen) are significantly better than EC-C (IC50 = 39.5 × ebselen) [20]. We speculate that this might be due to the acetyl and polyhydroxy group substitutions.

3.5. Molecular binding pose research

3.5.1. Molecular docking analysis

Through the initial docking studies, we obtained the information of binding energy (BE) and binding constant (Ki) of 12 catechins, and the lower values represent that the compound could interact with Mpro more tightly (Table S7). Generally, compounds 1–6, ECC, and EGC-pC has the lower binding energy under −9 kcal/mol, and the binding constants are all in the nanomolar range.

3.5.2. IFD and BPMD results

The ligand-complex stability results were acquired by IFD combing with the BPMD protocol. Based on the above results, we further predicted the binding mode and stability of 1 with Mpro. The interaction fingerprints protocol was used to classify protein-ligand binding poses from IFD results. The similarity was calculated using the Tanimoto method, and the clusters were calculated using the average linkage method. We selected one with the best IFD score in every cluster. Then the five clusters of 1 were uploaded to the BPMD protocol, exploring ligand stability in protein crystal structures [15]. CV was used to measure the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Besides, the PoseScore, PersScore, and CompScore were used to judge the ligand stability during the metadynamics simulations [15]. Table 4 shows the results of BPMD simulations.

Table 4.

Binding pose research of 1.

| compound 1 | Induced fit docking |

Binding pose Metadynamics |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XP Gscore | IFD score | Residue contact | PoseScore | PersScore | CompScore | CV_last RMSD | |

| Cluster 1 | −13.82 | −696.62 | THR26, HIS41, ASN142, CYS145, HIS163, GLN189 | 2.178 | 0.152 | 1.418 | 2.246 |

| Cluster 2 | −13.17 | −696.42 | THR26, SER46, HIS163, HIS164, GLU166 | 2.021 | 0.121 | 1416 | 2.047 |

| Cluster 3 | −10.94 | −693.06 | THR25, THR26, GLY143 | 2.130 | 0.112 | 1.570 | 2.267 |

| Cluster 4 | −10.54 | −692.91 | THR26, HIS41, PHE140, GLU166 | 2.127 | 0.393 | 0.162 | 2.175 |

| Cluster 5 | −13.97 | −696. 09 | HIS41, TYR54, HIS164, GLU166, LEU167, ARG188 | 2.603 | 0.285 | 1.178 | 2.775 |

Fig. 5B shows that cluster 4 of the 1-Mpro complex is more stable binding poses with lower CompScore (0.162), equivalent to PoseScore minus the five times PersScore. Interestingly, cluster 4 of the 1-Mpro complex has higher hydrogen bonds PerScore (39.3%) than cluster 3 of the 1-Mpro complex (11.2%). Fig. 5C shows the best (upper corner) and the worst binding pose (lower corner) of 1. In the upper corner, the 2‴-H in the substituted p-coumaric acid ring (substituted ring) of 1 formed the aromatic H-bond (2.67 Å) with amino acid residue CYS44. Besides, the 7-OH (A ring) formed the hydrogen bond (2.26 Å) with amino acid residue HIS41. Meanwhile, the aromatic ring of HIS41 had staking interaction with two rings of 1 (A ring and the substituted ring), whose intermolecular distances were 4.71 and 4.04 Å, respectively. The 5-OH and 6-H positions in the A ring of 1 formed the hydrogen bond with amino acid residue THR26, with distances of 1.93 and 2.70 Å, respectively. In addition, the galloyl group is the contributed part of 1, whose 3″-OH and 4″-OH position formed hydrogen bonds with PHE140 (1.90 Å) and GLU166 (1.59 Å), respectively. Through fragment molecular orbital analysis of peptide inhibitor N3, researchers have confirmed that HIS163, GLU166, and HIS41 are the most crucial amino acid residues [36].

Fig. 5.

The IFD-BPMD simulation of 1. (A) Structure of ligand (B) Average RMSD of six clusters of Mpro (6LU7)-1 complex during the 10 × 10 ns metadynamics runs. (C) Binding site of Mpro in complex with 1. The upper corner is cluster 4 of 1 (best pose); the lower corner is cluster 3 of 1 (worse posture) (yellow represents hydrogen bonds, purple stands for aromatic H-bond, green is the centroid distance, cyan represents the measured distance).

In the lower corner, the intermolecular interaction is mainly on the A and B rings of 1. The 6-H (A ring) formed the aromatic H-bond (2.39 Å) with amino acid residue CYS44. Meanwhile, the 7-OH (A ring) had the hydrogen interaction (1.58 Å) with amino acid residue THR25. Moreover, the hydroxyl group on the B ring plays a vital role in the binding pose of cluster 3. For example, the 3′-OH and 4′-OH formed the hydrogen bond with amino acid residue THR26, with distances of 1.71 and 2.30 Å, respectively. The 5′-OH formed the hydrogen bond (1.81 Å) with amino acid residue GLY143. The 6′-H formed the hydrogen bond (2.44 Å) with amino acid residue ASN142. Significantly, this combination mode is relatively unstable with a higher CompScore (1.57).

Besides, Fig. S66 shows the binding pose of 2–6 from the IFD results (IFDScore >610). Compounds 2–4 had the same intermolecular interaction with Mpro: A and B rings had pi-pi staking interaction with the aromatic ring of HIS41. 5-OH formed an H-bond with amino acid residue HIS164. 7-OH formed an H-bond with amino acid residue TYR54. We found that substituted cinnamic acid groups played an important role. For example, the 3″-OH on the substituted caffeic acid aromatic ring of 2 and the 8″-carbonyl oxygen of 4 formed hydrogen bonds with GLU166. The 3″-carbonyl oxygen on the acetyl group of 3 formed hydrogen bonds with GLN189. The substituted aromatic rings of 5 and 6 were stacked with the aromatic rings of HIS41. The 8″-carbonyl oxygen of 5 and 6 formed hydrogen bonds with HIS41 and ASN142.

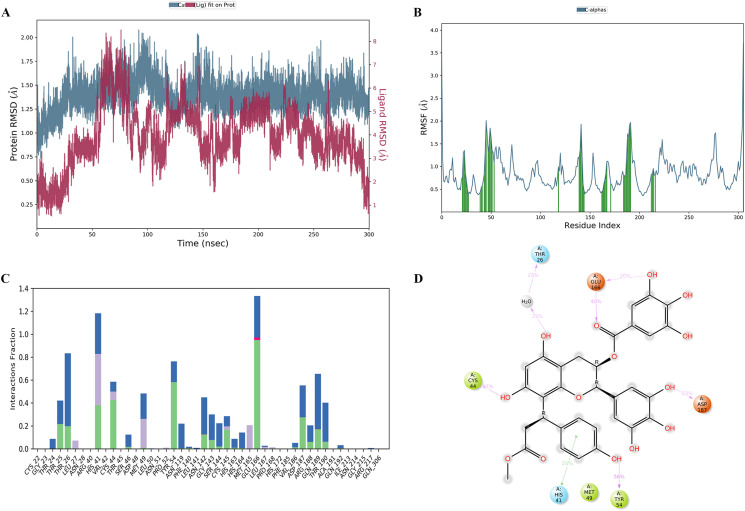

3.5.3. Molecular dynamics (MD) results

Over the 300 ns MD simulations in the Desmond software package [37], we can observe that 1 in cluster 4 conformation had stable binding with the protein. The ‘Simulation Interactions Diagram’ modular was used in statistical analysis [38]. In the last trajectory, we can observe that the RMSD of Mpro (6LU7) and 1 were stable at 1.25–1.50 Å and 1.0–2.0 Å (Fig. 6 A). Besides, Fig. 6A reveals that after 150 ns of MD simulation. The ligand-bound protein showed significant stability. Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) was assessed to analyze the flexible residues of protein when binding with ligands [34]. Fig. 6B shows that the primary flexible residues numbers are 20–30, 40–55, 140–145, 160–170, and 185–192, all in the active catalytic pocket [2]. Fig. 6C shows the interaction between the amino residues of Mpro and 1, including hydrogen, hydrophobic, water bridges, and hydrophobic bonds. Fig. 6D shows the interactions of more than 20% of the 300 ns MD simulations. The 5-OH position (A ring) built the hydrogen bond and water bridge with amino acid THR26 (25%), and the 7-OH (A ring) formed the hydrophobic bond and hydrogen bond with amino acid CYS44 (37%). Compared with the initial configuration, only the substituted ring had the aromatic staking interaction with the aromatic ring of HIS41 (41%). The 4‴-OH (substituted ring) had relatively persistent hydrogen bonds with TYR54 (56%). Interestingly, the amino acid ASP187 had hydrogen and water bridge interactions (23%) with 5′-OH (B ring), one of the specific hydroxyls as EGCG types of PSECs. Besides, the pyrogallol group has an electrophile effect on binding with cysteine proteinase covalently [9]. Thus, it is possible to state that the hydroxyl group at position 5′ of the B ring has an advantage as a covalent bonding site for the compounds of this class. In addition, the amino acid residue GLU166 not only had hydrogen interactions with 5″-OH of the gallate group (20%) but also with 7″-O (carbonyl group) of the gallate group (40%).

Fig. 6.

The 300 ns MD simulation of 1. (A) The RMSD plot of Mpro (6LU7)-1 complex during the 300 ns simulations. (B) The RMSF diagram of Mpro-1 complex at the end of the 300 ns simulations (protein residues that interact with the ligand are marked with green-colored vertical bars.). (C) The bar diagrams of Mpro-1 complex contacts during 300 ns simulations (green represents hydrogen bonds, blue represents water bridges, purple represents hydrophobic contacts, and rose-red represents ionic interactions). (D) The 2D diagram of Mpro-1 complex at the end of the 300 ns simulations.

Fig. S67 shows the interaction timeline between Mpro and 1. We can observe that the amino acid residues THR26, HIS41, GLU166, TYR54, ASP187, CYS44, and GLN189 have stable interactions, while ASN142, MET165, and THR190 have fluctuating binding stability, and SER44, GLY143, and CYS145 have weakly contact. Guo et al. suggest that HIS41, CYS145, and GLU166 are the critical amino acids for inhibitor binding by molecular docking studies [39]. Luo et al. used MD simulation to research the ritonavir-Mpro complex, pointing out that the critical residues are MET165 and GLN189 [40]. In addition, during the MD simulation, the ligand RMSD, radius of gyration (rGyr), intramolecular hydrogen bonds (intraHB), molecular surface area (MolSA), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), and polar surface area (PSA) of ligands were also studied (Fig. S68). The ligand RMSD in the last trajectory was lower than 1 Å, which was stable compared with the initial conformation. The rGyr represents the extensibility of the ligand, which fluctuated steadily between 4.50 and 5.00 Å. The intraHB of 1 was persistent and stable. The MoLSA, SASA, and PSA stabilized at 500, 300, and 480 Å2.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we used the methanol-water fraction of ZHDB tea, and its antioxidant activity is superior among the five extracts (IC50 = 0.72 μM). Then, 127 components isolated from ZHDB tea were analyzed using the GNPS platform, of which 33 compounds were identified by TMDB database and divided into 5 clusters. Then, we found a new m/z value in MN1 closely linked to EGCG and PSEC620, and found D-ring substituted catechin derivatives in MN5. Based on the above experiment, we isolated the new PSEC (1), which widely exists in 14 green tea samples. Besides, a series of HCCs (2–6) were synthesized, including three new acetylated HCCs. A variety of chromatographs and spectroscopies were used to identify these compounds. The SPR binding affinity and FRET inhibition assays showed that PSEC636 (1) (KD = 2.25 μM, IC50 = 5.95 μM), EGC-C (2) (KD = 2.81 μM, IC50 = 9.09 μM), and EC-CDA (3) (KD = 2.44 μM, IC50 = 23.10 μM) were the most effective Mpro inhibitors. The acetylated EGC-pCA (4) (KD = 3.85 μM) has a stronger binding affinity than EGC-pC (KD = 4.28 μM). Besides, the acetylated EC-pCA (5) (KD = 3.61 μM, IC50 = 77.47 μM) has significantly stronger binding affinity and inhibitory activity than EC-pC (6) (KD = 4.48 μM, IC50 = 210.80 μM). Therefore, acetyl modification may improve the inhibition activity. BPMD gave the best combination mode of Mpro -1 with IFD score at −692.91, PoseScore at 2.127, PersScore at 0.393, and CompScore at 0.163. Further, the results of 300 ns MD simulations suggest that the best binding mode of 1 stably interacts with the catalytic center of Mpro. The substituted p-coumaric acid aromatic ring, the hydroxyl of substituted p-coumaric acid, the carbonyl and hydroxyl of gallic acid, the benzobisphenol of A ring, and the pyrogallol of the B ring formed a pi-pi stacking with HIS41, H–H bonds with TYR54, H-bonds with GLU166, H-bonds with THR26 and CYS44, and H-bonds with ASP187, respectively.

CrdediT authorship contribution statement

Zi Yang: Investigation, and writing - original draft. Wei Wang: Methodology, and synthesis. Yan Qi: Investigation, review & editing. Yi Yang: review & editing. Chen-Hui Chen: review & editing. Jia-Zheng Liu: Resources. Gang-Xiu Chu: Supervision. Guan-Hu Bao: Conceptualization, data curation, supervision, and writing - review & editing.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Guan-Hu Bao has patent # CN113429372A pending to Anhui Agricultural University.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31972462].

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106288.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- BPMD

binding pose metadynamics

- CC

column chromatography

- CD

circular dichroism

- CE

collision energy

- CompScore

compositeScore

- COSY

correlation spectroscopy

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- DEPT

distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPPH

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- EC

(−)-epicatechin

- EC-C

(−)-epicatechin 3-O-caffeoate

- EC-CDA

3″,4″-diacetyl-O-(−)-epicatechin 3-O-caffeoate

- EC-pC

(−)-epicatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate; EC-pCA, 4″-acetyl-O-(−)-epicatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate

- ECG

(−)-epicatechin gallate

- EGCG

(−)-epigallocatechin gallate

- EGC

(−)-epigallocatechin

- EGC-C

(−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-caffeoate

- EGC-pC

(−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate

- EGC-pCA

4″-acetyl-O-(−)-epigallocatechin 3-O-p-coumaroate

- KD

equilibrium dissociation constants

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- FTIR

fourier-transform infrared

- GNPS

global natural product social molecular network

- IC50

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- MN

molecular network

- HCCs

hydroxycinnamoylcatechins

- HMBC

heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation

- HMQC

heteronuclear multiplequantum coherence

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HR-MS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- HSQC

heteronuclear singular quantum correlation

- IFD

induced-fit docking

- IntraHB

intramolecular hydrogen bonds

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MolSA

molecular surface area

- NPT

constant numbers of particles, pressure, and temperature

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NVT

constant numbers of particles, volume, and temperature

- OPLS

optimized potentials for liquid simulations

- PersScore

PersistenceScore

- PSA

polar surface area

- PSECs

phenylpropanoid-substituted ester-catechins

- RBD

receptor-binding domain

- rGyr

radius of gyration

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- RMSF

root-mean-square fluctuation

- ROESY

rotating frame overhauser effect spectroscopy

- SASA

solvent accessible surface area

- SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 main protease

- SPR

surface plasmon resonance

- TLC

thin-layer chromatography

- TOF

times-of-flight

- UPLC

ultra-high performance liquid phase

- ZHDB

Zhenghedabai

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lamers M.M., Haagmans B.L. SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022;20:270–284. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.L D., Zhang L., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Citarella A., Scala A., Piperno A., Micale N. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro): a potential target for peptidomimetics and small-molecule inhibitors. Biomolecules. 2021;11:607. doi: 10.3390/biom11040607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuong W., Khan M.B., Fischer C., Arutyunova E., Lamer T., Shields J., Saffran H.A., McKay R.T., van Belkum M.J., Joyce M.A., Young H.S., Tyrrell D.L., Vederas J.C., Lemieux M.J. Feline coronavirus drug inhibits the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 and blocks virus replication. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4282. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman R.L., Kania R.S., Brothers M.A., Davies J.F., Ferre R.A., Gajiwala K.S., He M., Hogan R.J., Kozminski K., Li L.Y., Lockner J.W., Lou J., Marra M.T., Mitchell L.J., Jr., Murray B.W., Nieman J.A., Noell S., Planken S.P., Rowe T., Ryan K., Smith G.J., 3rd, Solowiej J.E., Steppan C.M., Taggart B. Discovery of ketone-based covalent inhibitors of coronavirus 3CL proteases for the potential therapeutic treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:12725–12747. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Plassche M.A.T., Barniol-Xicota M., Verhelst S.H.L. Peptidyl acyloxymethyl ketones as activity-based probes for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. Chembiochem. 2020;21:3383–3388. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou B., Zhang Y.M., Liao H.Y., Fu L.F., Li D.D., Zhao X., Qi J.X., Yang W., Xiao G.F., Yang L., Zuo Z.Y., Wang L., Zhang X.L., Bai F., Yang L., Gao G.F., Song H., Hu J.M., Shang W.J., Zhou J. Target-based virtual screening and LC/MS-Guided isolation procedure for identifying phloroglucinol-terpenoid inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85:327–336. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su H., Yao S., Zhao W., Zhang Y., Liu J., Shao Q., Wang Q., Li M., Xie H., Shang W., Ke C., Feng L., Jiang X., Shen J., Xiao G., Jiang H., Zhang L., Ye Y., Xu Y. Identification of pyrogallol as a warhead in design of covalent inhibitors for the SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3623. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23751-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin Y.-H., Lee J., Jeon S., Kim S., Min J.S., Kwon S. Natural polyphenols, 1,2,3,4,6-O-pentagalloyglucose and proanthocyanidins, as broad-spectrum anticoronaviral inhibitors targeting Mpro and RdRp of SARS-CoV-2. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1170. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10051170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Léa El Khoury Z.J., Alberto Cuzzolin, Deplano Alessandro, Loco Daniele, Sattarov Boris, Hédin Florent, Wendeborn Sebastian, Ho Chris, Ahdab Dina El, Inizan Theo Jaffrelot, Sturlese Mattia, Sosic Alice, Volpiana Martina, Lugato Angela, Barone Marco, Gatto Barbara, Macchia Maria Ludovica, Bellanda Massimo, Battistutta Roberto, Salata Cristiano, Kondratov Ivan, Iminov Rustam, Khairulin Andrii, Mykhalonok Yaroslav, Pochepko Anton, Chashka-Ratushnyi Volodymyr, Kos Iaroslava, Moro Stefano, Montes Matthieu, Ren Pengyu, Ponder Jay W., Lagardère Louis, Piquemal Jean-Philip, Sabbadin Davide. Computationally driven discovery of SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors: from design to experimental validation. Chem. Sci. 2022;13:3674–3687. doi: 10.1039/d1sc05892d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adem S., Eyupoglu V., Ibrahim I.M., Sarfraz I., Rasul A., Ali M., Elfiky A.A. Multidimensional in silico strategy for identification of natural polyphenols-based SARS-CoV-2 main protease (M(pro)) inhibitors to unveil a hope against COVID-19. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022;145 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J., Lin X., Xing N., Zhang Z., Zhang H., Wu H., Xue W. Structure-based discovery of novel nonpeptide inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:3917–3926. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark A.J., Tiwary P., Borrelli K., Feng S., Miller E.B., Abel R., Friesner R.A., Berne B.J. Prediction of protein-ligand binding poses via a combination of induced fit docking and metadynamics simulations. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2016;12:2990–2998. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fusani L., Palmer D.S., Somers D.O., Wall I.D. Exploring ligand stability in protein crystal structures using binding pose metadynamics. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020;60:1528–1539. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allegra M., Tutone M., Tesoriere L., Attanzio A., Culletta G., Almerico A.M. Evaluation of the IKKbeta binding of indicaxanthin by induced-fit docking, binding pose metadynamics, and molecular dynamics. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.701568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ke J.P., Dai W.T., Zheng W.J., Wu H.Y., Hua F., Hu F.L., Chu G.X., Bao G.H. Two pairs of isomerically new phenylpropanoidated epicatechin gallates with neuroprotective effects on H2O2-injured SH-SY5Y cells from Zijuan green tea and their changes in fresh tea leaves collected from different months and final product. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:4831–4838. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke J.P., Yu J.Y., Gao B., Hu F.L., Xu F.Q., Yao G., Bao G.H. Two new catechins from Zijuan green tea enhance the fitness and lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans via insulin-like signaling pathways. Food Funct. 2022;13:9299–9310. doi: 10.1039/d2fo01795d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang W., Fu X.W., Dai X.L., Hua F., Chu G.X., Chu M.J., Hu F.L., Ling T.J., Gao L.P., Xie Z.W., Wan X.C., Bao G.H. Novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from Zijuan tea and biosynthetic pathway of caffeoylated catechin in tea plant. Food Chem. 2017;237:1172–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S.Y., Wang W., Ke J.P., Zhang P., Chu G.X., Bao G.H. Discovery of Camellia sinensis catechins as SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors through molecular docking, intra and extra cellular assays. Phytomedicine. 2022;96 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Q.-M., Yang Z., Zhang Y.-Y., Bao G.-H. Efficient development of antibacterial (−) -epigallocatechin gallate-PBCA nanoparticles using ethyl acetate as oil phase through interfacial polymerization. Food Biosci. 2021;44 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W., Zhang P., Liu X.-H., Ke J.-P., Zhuang J.-H., Ho C.-T., Xie Z.-W., Bao G.-H. Identification and quantification of hydroxycinnamoylated catechins in tea by targeted UPLC-MS using synthesized standards and their potential use in discrimination of tea varieties. LWT (Lebensm.-Wiss. & Technol.) 2021;142 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P., Ke J.P., Chen C.H., Yang Z., Zhou X., Liu X.H., Hu F.L., Bao G.H. Discovery and targeted isolation of phenylpropanoid-substituted ester-catechins using UPLC-Q/TOF-HRMS/MS-Based molecular networks: implication of the reaction mechanism among polyphenols during green tea processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69:4827–4839. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c00964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Micco S., Musella S., Scala M.C., Sala M., Campiglia P., Bifulco G., Fasano A. In silico analysis revealed potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 main protease activity by the Zonulin inhibitor larazotide acetate. Front. Chem. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.628609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X.X., Zhang X.J., Zhao Y.X., Feng J., Zeng J.C., Shi Q.Q., Kaunda J.S., Li X.L., Wang W.G., Xiao W.L., Aspulvins A.-H. Aspulvinone analogues with SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitory and anti-inflammatory activities from an endophytic cladosporium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85:878–887. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R E., Ross G.A., Deng Y., Lu C., Harder E.D., Abel R., Wang L. Enhancing water sampling in free energy calculations with grand canonical Monte Carlo. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2020;16:6061–6076. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.0c00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]