Abstract

Background

Despite significant improvements in Romania’s transplantation system, actual donor numbers have paradoxically fallen, contrary to the European trend. With a donation rate of 3.44 donors per million inhabitants, Romania ranks near the bottom of European countries. This study aimed to identify several predictors of a positive attitude toward organ donation in the Romanian population that could aid in reshaping public policies to improve donation and transplantation rates.

Material/Methods

The study included a representative Iasi population. Data were collected by means of a questionnaire focused on revealing attitudes toward organ donation, importance of consent, willingness to donate a family member’s organs, and role of medical staff in the donation decision. A perception score was calculated as a methodological approach to validate attitudes toward organ donation.

Results

Of all respondents, 55% agreed to donate their organs if declared brain-dead, while 20% opposed this idea; 72.7% considered consent necessary; 70% believed that consent must belong to the family when it comes to brain-dead organ donors; and 44.5% supported the idea of financial compensation. Higher monthly income was correlated with a positive attitude toward organ donation.

Conclusions

Even though the study population had a positive attitude toward organ donation, the willingness to donate was lower than in other European countries and did not translate into actual donations. The necessity of informed consent, lack of knowledge on the topic, bureaucratic aspects, and openness to financial compensation could explain the current situation of the Romanian transplantation system.

Keywords: Attitude, Health Policy, Perception

Background

The field of transplantation has gained popularity and interest in the scientific community due to the refinement of surgical techniques and long-term postoperative management [1,2]. Although organ transplantation is recommended in end-stage organ failure as a last resort to improve the survival rate, the population perception toward donating or receiving an organ is not as positive as expected [3].

With 157 301 solid organ transplants performed worldwide in 2019, transplantation activity increased steadily before being severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [4,5]. Between 2011 and 2019, the overall number of organ donors increased by 58.5% (from 25 776 to 40 858), with 78% brain-dead donors and 22% cardiac-activity donors [4].

With a donation rate of 3.44 donors per million inhabitants, Romania is ranked 42nd out of 82 states providing Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation data on donation and transplantation activity in 2020 [6]. Despite significant improvements in Romania’s healthcare system since joining the European Union (EU), including some in the transplantation system, the actual donor number has paradoxically fallen since 2014, contrary to the European trend [4,7,8].

Some factors were linked to the modest performance of the Romanian transplantation system, such as the underfunding of the national transplantation programs, lack of specialized medical staff, mandatory family consent, and poor communication between the different structures of the system. Nevertheless, population hesitation toward organ donation remains the most sensitive issue [9–11].

The Eastern European public perception of organ donation and transplantation is often based on social-demographic and cultural factors. In an analysis of social concepts and the dilemmas surrounding organ donation, Maloney and Walker (2002) found that although there is “a unanimous agreement on the noble idea of organ donation,” when people tried to elaborate on their beliefs, “a series of worries regarding cerebral death, mutilating the body of the deceased, human organ trafficking, and the role of the medical profession in the process of donating and transplanting organs” arose in their minds [10].

In a meta-analysis, which included a population from Middle Eastern countries, the authors reported several factors that interfere with donation acceptance, including educational status, being informed about the organ donation procedure, and family, spiritual, and religious factors [12]. However, data regarding the prevalence of these factors in Romania are scarce and warrant further research.

Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional survey study involving the general population of the municipality of Iasi to clarify the underlying reasons behind Romania’s low organ donation and transplantation rates. Iasi is a town near the Europe Union’s eastern border, with a population of 319 000. It provides healthcare services to a region with a population of 8 million people. We also intended to identify factors that could aid in reshaping public policies to improve donation and transplantation rates. In this study, we also attempted to mold the potential Romanian organ donor profile so that public health campaigns and media promotion, known to boost donation rates, could be better targeted.

Material and Methods

We performed a cross-sectional survey study involving the general population from the municipality of Iasi. The study protocol and reporting were compliant with the Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS) criteria. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Grigore T. Popa” of Iasi (no.114/15.10.2021).

Aims of Study

We aimed to identify several predictors of a positive attitude toward organ donation in an Eastern Romania population. In this regard, informed consent, knowledge level of organ transplantation, and psychological factors, such as altruism and motivation to save lives, were the main variables investigated in the present study.

Study Population

The study was conducted on a layered, multistage, representative sample of 440 respondents for the studied population (319 000 citizens of Iasi). With a population of 3 712 396, Iasi is the largest and most developed city and the only college city in Romania’s northeast region. A 3-stage probability sampling technique was used to choose a representative sample of city residents.

Questionnaire Methodology

The method of applying the questionnaire was straightforward. We used a systematic analysis to determine the sample size of the survey. The statements were edited as per the 14 informal criteria for the development of questionnaire statements of Likert [13] and Edwards [14]. The collection of statements relevant to the perception scale was the initial phase in the questionnaire’s design and was done longitudinally, with voluntary respondent participation. The positive and negative items were carefully chosen to minimize the effects of social desirability and positive response bias. The items were chosen in such a manner that respondents replied consistently to the statements [15,16]. The respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with each statement on a 6-point scale ranging from 6=always agree; 5=mostly agree; 4=somewhat agree; 3=somewhat disagree; 2=mostly disagree; and 1=strongly disagree.

Statistical Analysis

The data were uploaded and processed using SPSS version 18.0. The ANOVA test was used to analyze the dependent variable dispersion. The coefficient of variation was used to highlight the percentage deviation between 2 averages, providing results on the homogeneity of the series of values. To determine the significant differences between 2 or more groups, depending on the distribution of values, a threshold of 95% was considered significant. We applied the t test to compare the average values of quantitative variables recorded in 2 groups with normal distributions, and the F test (ANOVA) was used when comparing 3 or more groups with normal distributions. The chi-square test compared 2 or more frequency distributions from the same population. When a frequency in the calculation formula was low, the Yates correction was applied to correct the formula to get a higher estimate of the difference. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine the correlation of 2 variables in the same group (direct/indirect correlation). The receiver operating characteristic curve was used to trace the specificity and sensitivity balance as a prognostic factor.

Questionnaire Validation

The intercorrelation matrix provided an image of the degree of association between the items. The values show that there were no problems in constructing the respective items, and there was not a high degree of similarity. The value of Cronbach’s alpha (0.868) was acceptable, considering the threshold required (0.700) to validate the application of this questionnaire.

Variables Analyzed

The willingness to donate (WTD) a family member’s organs was the dependent variable, and respondents had to choose between 3 options: “most likely consent”, “unsure”, and “most likely refuse”. The following were the independent variables: (1) demographic (sex, age, education, marital status, and religion); (2) transplant-related knowledge; (3) concerns regarding the organizational and bureaucratic components of organ donation system, as well as the role of the medical team in the process; and (4) views or concerns that could have a substantial impact on people’s attitudes and intentions to donate their or their relatives’ organs.

Perception Score

Perception, according to Gibson, is the mechanism through which an individual maintains contact with the environment [17]. In constructing the scale, the summarized rating approach proposed by Likert was used [13].

The principle of the perception score is that the same questionnaire is applied to all cases and that for each item, the answer is associated with a numeric value: 1=always disagree; 2=mostly disagree; 3=sometimes agree; 4=frequently agree; 5=mostly agree; and 6=always agree. A score is calculated for each participant, ranging in this case from 25 to 150. As for the attitude toward organ donation, a higher score was interpreted as a “higher willingness to donate” and a lower score was interpreted as the opposite.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Grigore T. Popa” of Iasi (no.114/15.10.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Results

Demographics

The age of the participants (questionnaire respondents) ranged between 18 and 83 years with a mean of 43.55 years, close to the median of 44 years. The sex ratio was 1: 1. can be applied. We can rephrase it as follows: The skewness test result (P=0.072) suggested a normal distribution of the range of values, and thus a test of statistical significance could be applied. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Age as a statistical indicator.

| N | 440 | |

| Mean | 43.55 | |

| Median | 44 | |

| Standard deviation | 15.96 | |

| Variance | 36.53 | |

| Skewness test | 0.072 | |

| Std. err. of skewness | 0.117 | |

| Minimum | 18 | |

| Maximum | 83 | |

| Percentiles | 25 | 30 |

| 50 | 44 | |

| 75 | 57 | |

Most responses were obtained from respondents aged 50 to 59 years (21.1%), and the fewest responses were obtained from respondents under 20 years (5%) and over 80 years (4.8%).

The educational status revealed that 41.8% of respondents had a high school diploma, and 32.7% had higher education; 15.9% of the respondents had completed a vocational program, while in 6.6% of cases, the respondents’ educational level was elementary school. According to the socio-occupational status, 44.1% of respondents were employed, 20.5% were retired, 16.8% were students, 15.9% were freelancers, 7.3% were housekeepers, and 4.8% were unemployed. Of those who were employed, 18.2% were employed in the public sector and 23.6% in the private sector; 0.7% were administrators of public institutions and 1.6% were private company managers.

The monthly income was low: two-thirds of respondents earned below €400 per month; 34.1% had monthly income of less than €200; and 32.5% had a monthly income between €200 and €400. The monthly income was between €500 and €700 for 19.1% of respondents; between €700 and €900 for 13.3% of respondents; and more than €900 per month for 7.7% of respondents.

A total of 97.7% of the respondents were Christians; however, 43% of respondents had a moderate approach to religion: they did not consider themselves to be religious, but were also not unconcerned with religion.

Attitudes Toward Organ Donation and Transplantation

Of the total respondents, 48.4% always agreed, and 20.5% mostly agreed that organ transplantation is a cutting-edge medical procedure that saves lives, while 6.9% mostly disagreed, and 1.8% did not agree with this statement. Sixty-two percent agreed that people willing to donate organs for transplant are altruistic people who love their fellow human beings.

Fifty-five percent of the respondents would agree to donate their organs if declared brain-dead, while 20% opposed this idea. The exact proportions were valid regarding donating a family member’s organs. If a relative needed a transplant, 72.3% of those asked said they would donate one of their organs.

Consent in the Context of Organ Donation

Of the total, 72.7% of respondents mostly or always agreed that consent is necessary during a lifetime when it comes to organ donation, while 9% opposed this idea. The share of positive responses was in the range of 46% to 65% in male respondents, which was a statistically significantly different percentage compared to that of women (P=0.028).

Eighty percent of respondents agreed that no person could be compelled in any way to donate organs, and 76.6% of respondents affirmed that the donor should have the right to refuse donation until harvest, while 7.2% opposed this idea. The distribution by age groups showed significant differences (P=0.04): positive answers were more frequent in respondents under 45 years old, while negative answers were more frequent in the age group over 45 years old.

Of the total, 47.5% of respondents rejected the idea of procurement of organs in the absence of expressed consent during a lifetime. Only 23% would embrace such concepts as presumed consent.

Regarding brain-dead organ donors, nearly 70% of respondents agreed that the responsibility for consent should be given to the family of the deceased, with only 11% disagreeing. The age of the respondents made a big difference for this item as well. Younger respondents (those under 45 years) were firmer in agreeing with this assertion than older respondents (P=0.015).

Medical Team Involvement

The doctor’s role in deciding whether a brain-dead person should be a donor or not was denied. More than 55% of respondents did not believe that doctors should be involved in decision-making. Regarding the medical team’s role in the informational process on this matter, 82.5% of respondents agreed that the team should carry the responsibility of informing the donor in advance about the physical, mental, family, and professional risks. The need for the donor’s psychological evaluation before consenting to donation was expressed by 72.3% of respondents.

Organizational and Bureaucratic Aspects of Organ Donation System

Concerning having a single national donor register, 63% of respondents agreed with the register, while 47.3% would agree to have a donor card. Of the total, 56.5% of respondents expressed that individuals wishing to donate organs for transplantation must give their written consent to a notary or family doctor during their lifetime. Regarding formalizing their disagreement with organ donation with a notary or the family doctor while they are still alive, opinions of respondents were split in half. In the context of organ donation, 44.5% of respondents supported financial compensation, while 38.9% rejected it.

Knowledge of Organ Donation

Twenty-two percent of respondents believed that the Romanian population was well informed about organ donation and transplantation and what it means to be a donor or a recipient, while 52.1% believed the opposite to be true. According to 66% of respondents, more information regarding organ donation and transplantation would result in a considerable increase in the number of lives saved.

From all respondents, 44.6% mostly agreed that the church should be involved in informing the public about organ donation, while almost 80% would assign this role to the physician. Only 4% of respondents opposed physician involvement in the education of organ donation.

Variables Associated with the WTD a Family Member’s Organs

We observed no demographic characteristics that correlated with the WTD a family member’s organs when comparing demographics in respondents who indicated approval to donate a family member’s organs with those who stated they would refuse. Participants who considered that organ donation should be performed with the family’s approval were more likely to consent than those who believed that organ donation should be done with the donor’s or doctor’s consent (P<0.001). There was also a significant relationship between the WTD (the dependent variable) and 1 of the belief-related items: participants who believed that the body’s integrity should be preserved after death were less willing to give an organ from a family member (P<0.001). The association between the WTD one’s own organs after death and the WTD a family member’s organs was statistically significant (P<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Variables associated with the willingness to donate a family member’s organs.

| Variables | Most likely consent (n=304) | Most likely refuse (n=136) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.148 | ||

| Male (n=220) | 145 (47.7%) | 75 (55.1%) | |

| Female (n=220) | 159 (52.3%) | 61 (44.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Age | 0.764 | ||

| Under 45 y (n=215) | 150 (49.3%) | 65 (47.8%) | |

| Over 45 y (n=225) | 154 (50.7%) | 71 (52.2%) | |

|

| |||

| Education | 0.105 | ||

| Primary (n=29) | 20 (6.6%) | 9 (6.6%) | |

| Secondary (n=254) | 180 (59.2%) | 74 (54.4%) | |

| University (n=144) | 99 (32.6%) | 45 (33.1%) | |

| NA (n=13) | 5 (1.6%) | 8 (5.9%) | |

|

| |||

| Religion | 0.549 | ||

| Orthodox (n=391) | 269 (91.2%) | 122 (91.0%) | |

| Catholic (n=30) | 20 (6.8%) | 10 (7.5%) | |

| Protestant (n=8) | 6 (2.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

| Others (n=11) | 9 (3.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

|

| |||

| There is specific legislation in Romania | 0.620 | ||

| Yes (n=281) | 198 (65.1%) | 83 (61.1%) | |

| No (n=151) | 100 (32.9%) | 51 (37.5%) | |

| NA (n=8) | 6 (2.0%) | 2 (1.5%) | |

|

| |||

| Believe that organ transplantation saves lives | 0.090 | ||

| Yes (n=378) | 265 (87.2%) | 113 (83.1%) | |

| No (n=53) | 31 (10.2%) | 22 (16.2%) | |

| NA (n=9) | 8 (2.6%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Believe that agreement for organ harvesting is influenced by its type | 0.454 | ||

| Yes (n=99) | 72 (23.8%) | 27 (20.1%) | |

| No (n=292) | 202 (66.9%) | 90 (67.2%) | |

| NA (n=45) | 28 (9.3%) | 17 (12.7%) | |

|

| |||

| Considers that organ donation is done in consent with | 0.001 | ||

| Family (n=323) | 243 (79.9%) | 80 (58.8%) | |

| Donor (n=16) | 11 (3.6%) | 5 (3.7%) | |

| Doctor (n=14) | 11 (3.6%) | 3 (2.2%) | |

| NA (n=87) | 39 (12.8%) | 48 (35.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Believe that body integrity should be preserved after death | 0.001 | ||

| Consent (n=152) | 75 (24.7%) | 77 (56.6%) | |

| Unsure (n=64) | 37 (12.2%) | 27 (19.9%) | |

| Refuse (n=224) | 192 (63.2%) | 32 (23.5%) | |

|

| |||

| WTD one’s organs after death | 0.001 | ||

| Consent (n=198) | 160 (52.6%) | 38 (27.9%) | |

| Unsure (n=71) | 55 (18.1%) | 16 (11.8%) | |

| Refuse (n=171) | 89 (29.3%) | 82 (60.3%) | |

|

| |||

| Agreeing to donate the organs of a brain-dead family member | 0.001 | ||

| Consent (n=376) | 294 (96.7%) | 82 (60.3%) | |

| Unsure (n=29) | 7 (2.3%) | 22 (16.2%) | |

| Refuse (n=35) | 3 (1.0%) | 32 (23.5%) | |

WTD – willingness to donate; NA – no answer.

Multivariate Analysis

The results of the multivariate analysis indicated that the following remained as significant factors of one’s WTD a family member’s organs after death: not believing that organ donation should be done with the consent of the family; not believing that body integrity should be preserved after death; and willingness to donate the organs of a brain-dead family member (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variables influencing the willingness to donate a family member’s organs. Multivariate logistical regression analysis.

| Variable | B | SE | OR (CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Considers that organ donation is done in consent with family | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| No | 1.36 | 0.34 | 3.91 (2.01–7.63) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Believe that body integrity should be preserved after death | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| No | 0,19 | 0.55 | 1.20 (0.41–3.53) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| WTD one’s organs after death | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 0.31 | 0.45 | 1.37 (0.57–3.29) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Agreeing to donate the organs of brain-dead family member | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 3.07 | 0.77 | 0.05 (0.01–0.21) | 0.001 |

B – regression coefficient; SE – standard error of coefficient; OR – odd ratio; CI – confidence interval.

Perception Score

The set of values of the organ donation perception assessment score was homogeneous, suggesting that tests of statistical significance could be applied (Table 4, Figure 1): variations in scores in the range of 32 to 150; group average score of 108.80±20.35; median score of 112; and skewness of test result P=−0.641.

Table 4.

Statistical indicators of the perception score.

| N | 440 | |

| Mean | 108.80 | |

| Median | 112 | |

| Standard deviation | 20.35 | |

| Variance | 18.70 | |

| Skewness test | −0.641 | |

| Std. err. of skewness | 0.116 | |

| Minimum | 32 | |

| Maximum | 150 | |

| Percentiles | 25 | 95 |

| 50 | 112 | |

| 75 | 123 | |

Figure 1.

Perception score histogram. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

Perception score did not correlate with age (r=0.029; P=0.551) (Figure 2). The average score was slightly lower in men, but no statistically significant difference was observed (108.41±20.66 vs 109.20±20.07; P=0.677; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Correlation between age and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

Figure 3.

Correlation between sex and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

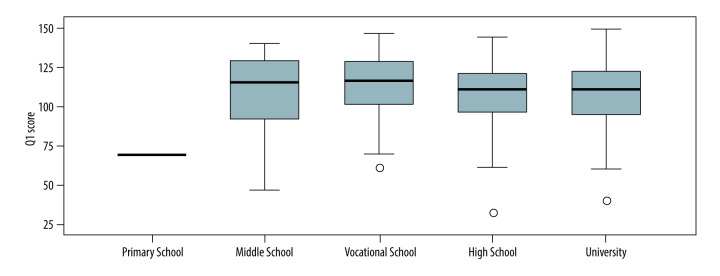

The perception score was lowest in respondents with primary education (69±0.3) and highest in respondents with vocational school (113.16±19.42), but there was also no statistically significant difference between groups (P=0.125; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between educational status and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

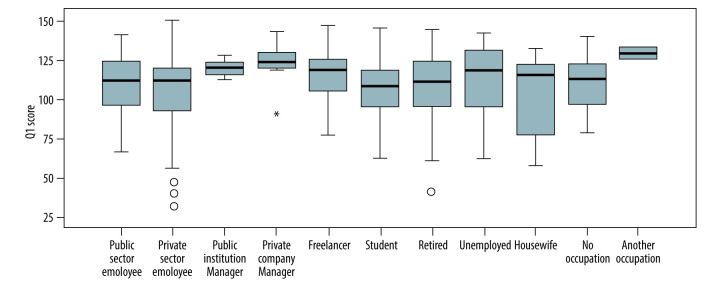

The lowest average perception score was obtained in respondents employed in the private sector (105.64±22.85) and the highest in respondents with other occupations (129.0±5.66), but the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.244; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Correlation between socio-occupational status and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

The correlation between average perception score and monthly income was significant. The lowest average score was in respondents with an average income between €300 and €400, and the highest in respondents with an average income over €900 (P=0.027; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Correlation between monthly income and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

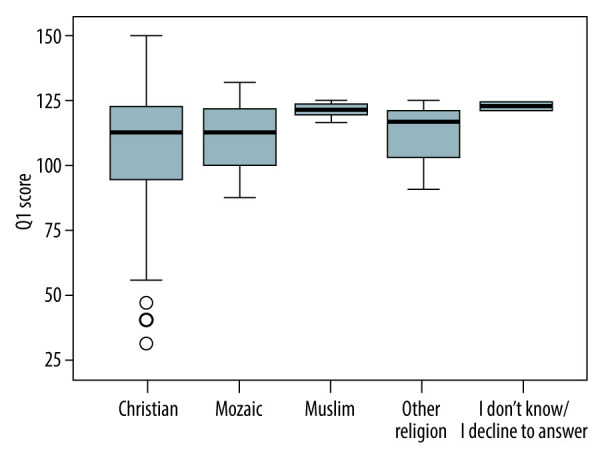

Perception score was not significantly correlated with religious affiliation; the lowest average level was recorded for respondents with Christian affiliation (108.64±20.46) and the highest for those with Muslim affiliation (121.33±4.04, P=0.772; Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Correlation between religion and perception score. Figure created with SPSS 18.0, IBM SPSS Statistics.

Discussion

Our research is the most comprehensive on the general public’s attitude toward organ donation and transplantation in Romania. According to our data, 68.9% of the general public perceive transplantation positively, as cutting-edge medical interventions that have the potential to save lives.

Eighty percent of respondents reported that they would be willing to adhere to organ donation only through informed consent. Our results indicated that the average Romanian individual associates the act of donation with high responsibility and, at the same time, a desire to learn everything there is to know about the physical, emotional, family, and professional implications of organ donation.

This necessity for substantial information also suggests that the respondents were concerned about their fate or the fate of others, with the decision-making process involving a great deal of personal interest. When it comes to such an important issue as organ donation and transplantation, the respondents’ moral and ethical standards were tested. Similarly, respect for the human being and the assertion of his or her freedom through the decision that he or she would be invited to make were central to the issue of consent. Respondents indicated that they preferred to be active respondents in the decision to accept donation and transplantation and to be open and informed partners. It should be noted, however, that while sufficient organ donation knowledge and altruistic motives have been found as factors influencing organ donation attitudes and intentions, these factors may not always transfer into actual registrations [18–20].

It should be highlighted that the lack of consent during one’s lifetime has nothing to do with the donation agreement. Romanian society is unwilling to accept legislation based on presumed consent to organ donation that would allow the organs to be utilized for transplantation if the deceased person did not make a written statement opposing organ donation [11,21]. Although many European Union nations have adopted the “opt-out” method, which is seen as a viable and efficient legislative foundation for a successful dead organ donation program, our research strengthens the importance of explicit consent for Romanians, a fact that can partially explain the lower registration rates compared with countries with presumed consent registration policies [22]. At the same time, it is worth mentioning that although some publications suggest that switching to an opt-out method would be a good idea [23], the impact on actual donations has been mixed and uneven due to confusion about a deceased person’s donation preferences [24].

When it comes to assigning the responsibility of deciding upon organ donor status, the answers in the present study demonstrated that the family is invested with the authority of having the last say, whose perspective is impacted by a multitude of cultural and religious ideas and attitudes. The potential donor’s family must take a compassionate attitude since this has been shown to decrease the refusal rate for organ donation significantly. Improvements in transplant coordinator communication abilities have been shown to have the potential to significantly lower the refusal rate for organ donation [25,26].

Croatia and Slovenia, countries confronted with similar problems with transplantation as Romania, have found an optimal solution to approach a reluctant society toward organ donation. The right to choose between “opt-in” and “opt-out,” or an extension to the opt-out law that specifies that the decision of the family would always be honored (after it is confirmed that the deceased person did not oppose donation), has been able to prevent unfavorable publicity that could lead to a reduction in the donor rate [25,27].

The mandated choice is another attractive public policy alternative based on its potential to increase donation rates. It supports the idea that people should be required by law to state in advance whether or not they are willing to donate their organs after they die, and their decisions would be final [28,29]. According to Spital, a significant majority of individuals would favor the mandated choice over presumed consent because they believe the family should not be allowed to overturn their recently dead loved one’s previously expressed wishes. However, it is worth mentioning that the efficiency of compelled choice policies, like any other policy, is determined by the compliance rate [30].

Some authors have questioned whether the family veto, which allows the family of a registered organ donor to oppose the removal of organs for transplantation, is ethically permissible [31].The scarce research available shows that public support for the family veto is limited [32]. There are no grounds, according to Albertsen, that might justify the family veto and contempt for the deceased’s desires [31]. The Romanian society’s reaction to this notion suggests a promising new study avenue that should be investigated.

In the present study, the attitudes regarding the physician’s role in deciding if a brain-dead individual should become a donor or not were mainly adverse, with about 50% of respondents opposing this idea. When it comes to the need for a psychological evaluation of the potential donor before consenting to donation, most respondents considered this favorable. Such changes in attitudes can be explained by a familiarizing process in the population with the role of the psychologist in determining the ability of a person to make critical decisions. In addition, the answers highlight the influence that the specialists have in the decision-making process.

The respondents were rather receptive to the notion of extensive regulatory control, norm establishment, and successful management of the organ donation in Romanian society. As a result, most respondents had favorable opinions toward the necessity for a single national transplant registry, the availability of a donor card, or the participation of a doctor or notary to confirm the consent.

Many societies have implemented successful organ donation and transplantation system models that Romania should take as an example of the legislative framework [25]. The establishment of a national organization for organ procurement and transplantation [27], the implementation of a new financial model with donor hospital reimbursement, and public awareness campaigns were vital factors in the development of this successful model for organ procurement and transplantation in countries like Croatia and Slovenia, which had similar levels of economic development and low donation rates at the turn of the twenty-first century as Romania [27]. Also, the implementation of an Intensive Care to Facilitate Organ Donation program would likely enable a greater number of genuine and high-quality grafts to be available for transplantation, while also requiring less intensive medicine resources [33].

A positive public attitude toward organ donation and increased information availability, mainly when transplantation medical experts provide information, are essential components of a successful transplantation program [25]. Countries that experience similar problems as Romania regarding the transport system have credited their progress to a variety of public awareness events and a steady, well-respected media dialogue aimed at promoting donation cases, saving lives through organ transplantation, successful transplant interventions, and favorable newspaper articles on organ donation and transplantation [27]. Our research showed that people’s perceptions of how well-informed they are about organ donation and transplantation are mixed and typically unfavorable. Because most of the respondents felt that being well educated would favorably affect the number of lives saved, it can be deemed a high priority in the decision-making process.

Our research showed that health professionals and clerical institutions are seen as trustworthy sources of information and should be more involved in organ donation and transplantation awareness efforts. Between the two, there is a stronger preference toward physicians. This finding suggests that, in the respondents’ opinions, transplantation and donation should be approached from a scientific, normative, and ethical standpoint, with moral and religious considerations being secondary.

It is worth mentioning that the vast majority of respondents stated that no one could compel someone to donate organs, as the consent to donate was seen as an expression of respect and love that goes beyond scientific explanation and justification.

Limitations

As a limitation of this study, the sample included only people who were met in highly frequented urban public spaces, resulting in potential selection bias. Also, the city of Iasi is the second largest and one of the most developed areas in Romania, as well as an important university town, and therefore may not be representative of the entire country. Another limitation was the non-response errors that occurred when respondents did not answer one or more questions.

Conclusions

Even though the study population had a positive attitude toward organ donation, the WTD in Romania is lower than in other European countries and does not translate into actual donations. The necessity of informed consent, lack of knowledge on the topic, bureaucratic aspects, and openness to financial compensation could explain the current situation of the Romanian transplantation system. The act of donation was associated with the idea of sacrifice, altruism, and love, but our research highlights a remarkable contradiction. There is a fragile equilibrium between those open to the possibility of having some monetary reward in exchange for organ donation and those who would refuse any kind of monetary reward for donating an organ. In other words, accepting the donation of an organ is an indicator of a person’s altruism, but this does not rule out the idea of receiving a reward for this gesture.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

Financial support: None declared

References

- 1.Matevossian E, Kern H, Hüser N, et al. Surgeon Yurii Voronoy (1895–1961) – a pioneer in the history of clinical transplantation: in Memoriam at the 75th Anniversary of the First Human Kidney Transplantation. Transpl Int. 2009;22(12):1132–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordham KD, Ninokawa S. The history of organ transplantation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2022;35(1):124–28. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2021.1985889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mithra P, Ravindra P, Unnikrishnan B, et al. Perceptions and attitudes towards organ donation among people seeking healthcare in tertiary care centers of coastal South India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19(2):83–87. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.116701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valentini L, Schaper L, Buning C, et al. Malnutrition and impaired muscle strength in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in remission. Nutrition. 2008;24(7–8):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Putzer G, Gasteiger L, Mathis S, van Enckevort A, et al. Solid Organ donation and transplantation activity in the Eurotransplant area during the first year of COVID-19. Transplantation. 2022;106(7):1450–54. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen DL, Parekh N, Bechtold ML, et al. National trends and in-hospital outcomes of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving parenteral nutrition support. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(3):412–16. doi: 10.1177/0148607114528715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vladescu C, Scintee SG, Olsavszky V, et al. Romania: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2016;18(4):1–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arredondo E, López-Fraga M, Chatzixiros E, et al. Council of Europe Black Sea Area Project: International cooperation for the development of activities related to donation and transplantation of organs in the region. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(2):374–81. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman A, Beatrice I. The malfunctions of a national transplantation system: Multi-layered explanations from within. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2016;120(1):62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigoraş I, Blaj M, Florin G, et al. The rate of organ and tissue donation after brain death: Causes of donation failure in a Romanian university city. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(1):141–43. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigoras I, Condac C, Cartes C, et al. Presumed consent for organ donation: Is Romania prepared for it? Transplant Proc. 2010;42(1):144–46. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mekkodathil A, El-Menyar A, Sathian B, et al. Knowledge and willingness for organ donation in the Middle Eastern Region: A meta-analysis. J Relig Health. 2020;59(4):1810–23. doi: 10.1007/s10943-019-00883-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:55–55. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards AL. Techniques of attitude scale construction. Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal S, Kadian K, Jha S, et al. a resilience scale to measure farmers’ suicidal tendencies in national calamity hit region of India. Curr World Environ. 2014;9:1001–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal S, Mohammad A, Ponnusamy K. Divulging magnitude of perceptual levels of participants in National Dairy Mela (Fair) of India: A farmers’ perspective. J Glob Commun. 2015;8:158. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch SE. Psychology: A study of a science. McGraw-Hill; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falomir-Pichastor JM, Berent JA, Pereira A. Social psychological factors of post-mortem organ donation: A theoretical review of determinants and promotion strategies. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7(2):202–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radecki CM, Jaccard J. Psychological aspects of organ donation: A critical review and synthesis of individual and next-of-kin donation decisions. Health Psychol. 1997;16(2):183. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radecki CM, Jaccard J. Signing an organ donation letter: The prediction of behavior from behavioral intentions 1. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(9):1833–53. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunders B. Normative consent and opt-out organ donation. J Med Ethics. 2010;36(2):84–87. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.033423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson EJ, Goldstein D. Medicine Do defaults save lives? Science. 2003;302(5649):1338–39. doi: 10.1126/science.1091721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steffel M, Williams E, Tannenbaum D. Does changing defaults save lives? Effects of presumed consent organ donation policies. Behav Sci Policy. 2019;5:68–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domínguez J, Rojas JL. Presumed consent legislation failed to improve organ donation in Chile. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(4):1316–17. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Živčić-Ćosić S, Bušić M, Župan Ž, et al. Development of the Croatian model of organ donation and transplantation. Croat Med J. 2013;54(1):65–70. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlić P, Andrasević D, Zeidler F, et al. Cadaver kidney harvesting in the region of Rijeka, Yugoslavia. Transplant Proc. 1991;23(5):2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danica Avsec JS. Twenty years of deceased organ donation in Slovenia: Steps towards progress in quality, safety, and effectiveness. Am J Health Res. 2021;9(3):82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chouhan P, Draper H. Modified mandated choice for organ procurement. J Med Ethics. 2003;29(3):157–62. doi: 10.1136/jme.29.3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harish A, George T, Kurian V, Mullasari Ajit S. Arteriovenous malformation after transradial percutaneous coronary intervention. Indian Heart J. 2008;60(1):64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spital A. Mandated choice. The preferred solution to the organ shortage? Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(12):2421–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.12.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albertsen A. Against the family veto in organ procurement: Why the wishes of the dead should prevail when the living and the deceased disagree on organ donation. Bioethics. 2020;34(3):272–80. doi: 10.1111/bioe.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downie J, Shea A, Rajotte C. Family override of valid donor consent to postmortem donation: Issues in law and practice. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(5):1255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-Soba F, Miñambres E, Martínez-Camarero L, et al. Results after implementing a program of intensive care to facilitate organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(2):299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]