Abstract

In an effort to enhance the trustworthiness of its clinical practice guidelines, the Endocrine Society has recently adopted new policies and more rigorous methodologies for its guideline program. In this Clinical Practice Guideline Communication, we describe these recent enhancements—many of which reflect greater adherence to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to guideline development—in addition to the rationale for such changes. Improvements to the Society’s guideline development practices include, but are not limited to, enhanced inclusion of nonendocrinologist experts, including patient representatives, on guideline development panels; implementation of a more rigorous conflict/duality of interest policy; a requirement that all formal recommendations must be demonstrably underpinned by systematic evidence review; the explicit use of GRADE Evidence-to-Decision frameworks; greater use and explanation of standardized guideline language; and a more intentional approach to guideline updating. Lastly, we describe some of the experiential differences our guideline readers are most likely to notice.

Keywords: clinical practice guidelines, practice guidelines, GRADE approach, systematic reviews, trust, trustworthiness

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM; previously the Institute of Medicine) has defined clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options” (1). In recent years, the Endocrine Society has adopted new policies and more rigorous methodologies for its CPGs. The first of 3 new guidelines developed according to these policies and methodologies—Management of Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients in Non-Critical Care Settings—is published in this issue of the Journal (2). Herein we describe recent enhancements in the Society’s guideline development practices, the rationale for such changes, and the guideline differences readers are most likely to notice.

Enhancing Guideline Trustworthiness: Historical Context

While the medical literature has long included various publications intended to guide clinical practice, formal methods of reaching consensus on practice guidelines started to emerge in the 1970s. For example, in the 1977 National Institute of Health Consensus Development Program, recommendations were developed in a closed session that followed a plenary and open discussion (3). However, aside from formal voting, there was no clear framework for evidence synthesis or decision-making (3). An increasing number of published studies accompanying the evidence-based medicine movement in the late 1980s and early 1990s emphasized the importance of formal evidence appraisal and integration in decision-making (4).

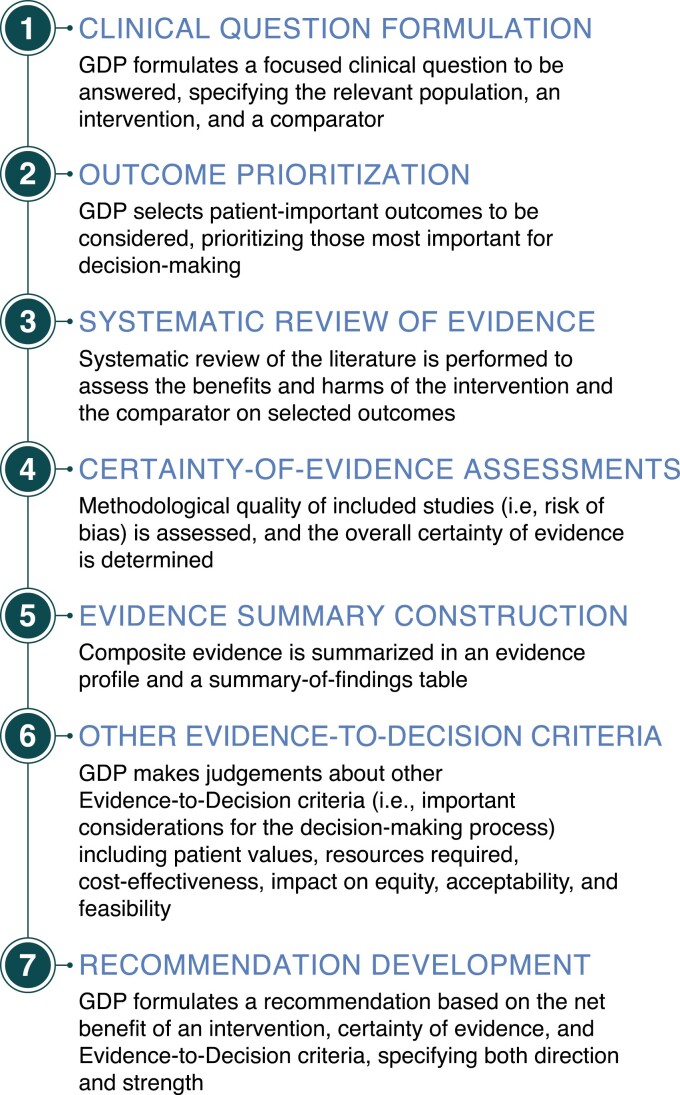

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group has developed concepts and guidance on assessing certainty of evidence and making clinical recommendations since 2000 (5-7). The Endocrine Society became an early adopter of GRADE (8), starting with its guidelines published in 2006 (9-11). Subsequently, GRADE became the most accepted standard for guideline development. Other prominent organizations using GRADE include the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the World Health Organization (7). Key steps of the GRADE approach are shown in Fig. 1 (12-15).

Figure 1.

Key steps of the GRADE approach. Abbreviations: GDP, guideline development panel.

Enhancing Guideline Trustworthiness: Pathway Identification

In 2011, the NAM asserted: “To be trustworthy, guidelines should be based on a systematic review of the existing evidence; be developed by a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups; consider important patient subgroups and patient preferences, as appropriate; be based on an explicit and transparent process that minimizes distortions, biases, and conflicts of interest; provide a clear explanation of the logical relationships between alternative care options and health outcomes, and provide ratings of both the quality of evidence and the strength of the recommendations; and be reconsidered and revised as appropriate when important new evidence warrants modifications of recommendations” (1). Importantly, faithful adherence to GRADE will ensure that guidelines fulfill a majority of these NAM standards of trustworthiness (16).

In recent years, the Endocrine Society has critically reviewed its guideline development processes to assess the degree to which they meet NAM standards. For example, the Society’s Clinical Guidelines Committee (CGC; formerly Clinical Guidelines Subcommittee) asked the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) to assess its 2016 Hormonal Replacement in Hypopituitarism in Adults guideline (17) via the NGC Extent Adherence to Trustworthy Standards (NEATS) instrument (18). Through this assessment and others, the CGC identified a number of ways it could enhance adherence to NAM standards, including greater inclusion of nonphysician specialists on guideline development panels (GDPs) when relevant; improved conflict/duality of interest (C/DOI) management; more detailed explanations of benefits and harms of interventions; more concise, clear, and precise recommendations; better explanations of strength of recommendation terminology and certainty of evidence ratings; enhanced incorporation of patient perspectives and values (“patient voice”) in the guideline development process; and more explicit descriptions of guideline updating plans.

Another important target for improvement related to how GDPs documented evidential foundations for recommendations. While some of the Society’s guideline recommendations were underpinned by formal systematic evidence reviews—considered to be an essential component of the GRADE approach—a substantial percentage of recommendations were based on nonsystematic literature review performed by GDP members. As an illustration of the foregoing, in 2019 the ECRI Guidelines Trust—which the ECRI Institute launched in response to the defunding of the NGC (19)—asked the Society for permission to include its guidelines in the ECRI Guidelines Trust database. However, of the Society’s guidelines evaluated by ECRI (ie, those published since 2015), only the 2019 Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women guideline (20) was eligible for formal ECRI Transparency and Rigor Using Standards of Trustworthiness (TRUST) scoring, as this was the only guideline for which all recommendations were based on verifiable systematic evidence review with explicit descriptions of search strategy, study selection, and evidence summaries (21,22).

Enhancing Guideline Trustworthiness: Organizational Commitments

In 2017, the Endocrine Society’s Board of Directors (BOD; previously Council) approved its Fourth Strategic Plan, which prioritized strengthening of the Society’s CPG program. Accordingly, and in light of the CGC’s assessments of its guidelines vis-à-vis NAM standards, the BOD approved the creation of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force (CPGTF; see acknowledgements). In 2018, the CPGTF issued a number of recommendations, some of which included full and explicit implementation of GRADE; an exploration of in-house guideline methodologists; standardizing procedures for guideline topic and GDP selection; and standardizing procedures for guideline updating and retirement as indicated.

Also in 2018, the Society’s BOD approved a 2-pronged CGC-initiated Strategic Plan Business Plan and Investment Request (SPI) designed to enhance the trustworthiness of the Society’s CPGs. The SPI funded a new agreement with Mayo Clinic’s Evidence-Based Practice Center (EBPC), expanding the number of systematic reviews per guideline from 2 to 10. In addition, the SPI funded extensive GRADE training for Endocrine Society guideline staff and selected Society members to facilitate more effective implementation of GRADE in guideline development. This training was provided by leaders in the GRADE Centre at McMaster University through the recently developed International Guideline Development Credentialing & Certification Program (inguide.org). As another facet of the Society’s agreement with McMaster University, McMaster GRADE experts provided extensive methodological consulting for 3 Society guidelines.

Enhancing Guideline Trustworthiness: Deliberate Steps

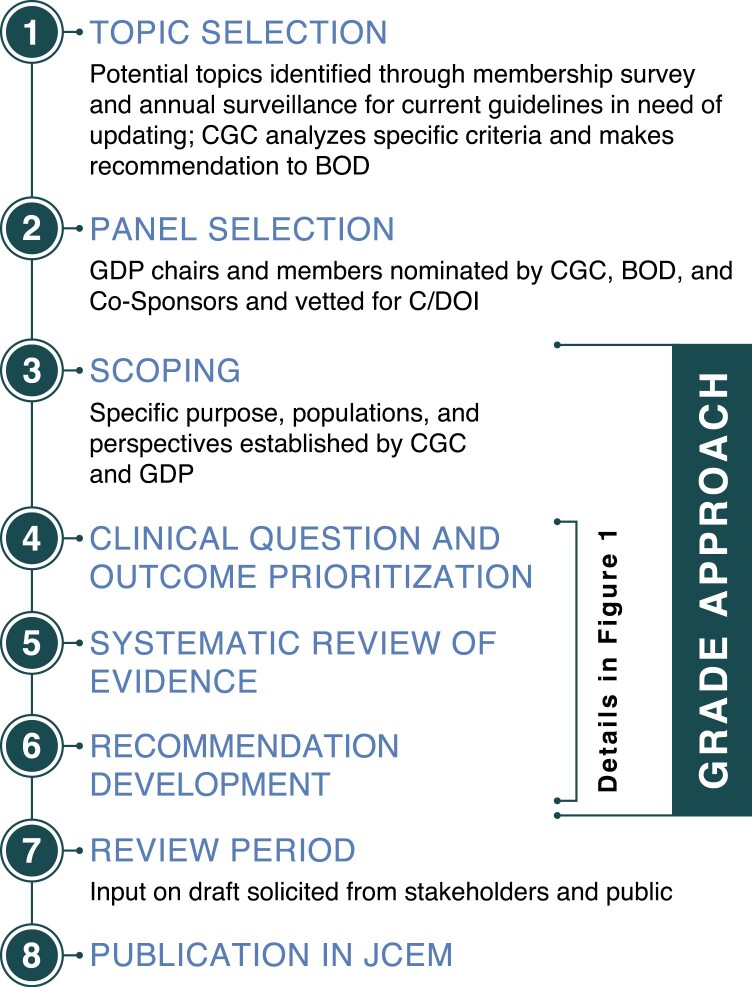

The aforementioned SPI was implemented in parallel with the initiation of the following 3 guidelines in 2019: Management of Hyperglycemia in Hospitalized Patients in Non-Critical Care Settings (hereafter shortened to Inpatient Hyperglycemia), Management of Individuals with Diabetes at High Risk for Hypoglycemia (Hypoglycemia in Diabetes), and Treatment of Hypercalcemia of Malignancy in Adults (Hypercalcemia of Malignancy). Concomitantly, the CGC introduced a number of changes in its guideline development processes to better meet NAM standards for trustworthy guidelines (1,23). A broad overview of the Society’s guideline development process is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Society’s guideline development process. Abbreviations: BOD, Board of Directors; C/DOI, conflict/duality of interest; CGC, Clinical Guidelines Committee; CPG, clinical practice guideline; GDP, guideline development panel; JCEM, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Guideline Development Group Composition

The CGC has sought to enhance the multidisciplinary nature of its GDPs by including clinicians from various specialties. The Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP includes a Diabetes Clinical Nurse Specialist, a clinical pharmacist, a general internist, a methodologist who is also a general internist, and a methodologist who is also a Registered Dietitian. The Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP includes a medical oncologist, a methodologist who is also a general internist, and a methodologist who is also a family practitioner and preventive medicine specialist. At its outset, the GDP for Hypoglycemia in Diabetes, which focused on both adults and children, included 2 pediatric endocrinologists, a clinical pharmacist, a diabetes-focused nurse practitioner who is also a Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist, a general internist, and a methodologist who is also a general internist.

Patient representatives were recruited for each of these 3 GDPs as well (see Acknowledgments). To facilitate effective participation, the McMaster GRADE Centre provided these patient representatives GRADE training specifically designed for GDP members. (All panel members received such training.) Based on its experience thus far, the CGC considers the inclusion of patient representatives on GDPs to be exceptionally valuable: in addition to providing first-hand patient perspectives, patient representative participation serves as a constant reminder for all panel members to prioritize patient perspectives and values as much as possible.

In addition to an experienced guideline methodologist who has partnered with the Endocrine Society since 2006, methodologists from McMaster GRADE Centre served on each of the 3 GDPs. These second methodologists primarily guided panel members in the implementation of GRADE and the Evidence-to-Decision process. Starting with the Society’s 3 most recently initiated CPGs (related to vitamin D, diabetes in pregnancy, and primary hyperaldosteronism), Endocrine Society Guideline Methodologists—endocrinologist Society members trained in GRADE by experts at McMaster GRADE Centre—are serving as GRADE-focused methodologists along with the methodologist overseeing systematic reviews.

Engagement of co-sponsoring organizations is another important component of the CGC’s GDP selection process. In particular, CGC leaders and GDP chairs identify potential co-sponsoring organizations based on the clinical topic, desired expertise, and intended audience; and these organizations are invited to appoint official representatives to the GDP. Such cooperation helps reduce the risk of inappropriately restricting GDP membership to those with a particular point of view (ie, GDP “stacking”), and it may also increase overall guideline buy-in. For the Inpatient Hyperglycemia guideline, the following co-sponsoring organizations appointed representatives to the GDP: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American Diabetes Association, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, Diabetes Technology Society, and European Society of Endocrinology. Although the American College of Physicians is not a co-sponsor of the Inpatient Hyperglycemia CPG, it assisted the Society in the identification of a general internist to serve on the GDP.

Looking toward the future, the CGC developed a standardized process for GDP assembly in 2020-2021. Aiming to assemble GDPs in a robust, fair, and transparent manner, the primary goals of this new process are (1) to ensure a multidisciplinary GDP, including members with expertise relevant to the topic (eg, primary care clinicians, pediatricians, other medical subspecialists, nurses, pharmacists, patient representatives, etc.); (2) to encourage panel diversity with regard to factors such as internationality, gender, race/ethnicity, and career stage; (3) to avoid GDP “stacking”; and (4) to ensure adherence to the CGC’s conflict/duality of interest policy. With these specific goals in mind, the CGC will take a larger role in future GDP member selection.

Establishing Transparency

The Society aspires to full methodological transparency. A description of the Society’s guideline development methodology is posted on its webpages (endocrine.org/clinical-practice-guidelines/methodology). In brief, the CGC aspires to faithful adherence to GRADE. For example, starting with the Inpatient Hyperglycemia CPG, all guideline recommendations will be underpinned by formal systematic evidence reviews (see below). Full details of these systematic reviews—including explicit descriptions of search strategy, study selection, and evidence summaries—will be made available to readers in supplemental materials or in separate publications. In addition, GDPs will carefully document their use of GRADE Evidence-to-Decision frameworks (24-26). These frameworks prompt panels to explicitly consider the following in their deliberations: desirable and undesirable effects of an intervention vis-à-vis its comparator, the certainty of evidence regarding desirable/undesirable effects, patient values, resources required, cost-effectiveness, impact on equity, acceptability, and feasibility. Panels will explicitly justify all recommendations in light of these Evidence-to-Decision factors, and detailed Evidence-to-Decision tables will be provided in supplemental materials.

Management of Conflicts of Interest

In 2019, the CGC established, and the BOD approved, a more rigorous conflict/duality of interest (C/DOI) policy for its GDPs (Table 1) (27). During its deliberations, the CGC wrestled with a tension related to GDP members with relevant industry relationships. On the one hand, the CGC acknowledged that limiting GDP members with pertinent C/DOI would minimize the possibility of real or perceived bias, thus enhancing guideline trustworthiness. On the other hand, many CGC members believed that having well-recognized experts on a GDP is important for guideline development and can lend credibility to the guideline, even though many well-recognized experts have relevant industry relationships. In the end, the CGC elected to adopt NAM standards related to GDP C/DOI, even if doing so means that fewer well-recognized experts will be on its GDPs. The CGC trusts that its guidelines will achieve full credibility via methodological rigor and transparency.

Table 1.

Summary of the Clinical Guideline Committee’s conflict/duality of interest policy

| Policy definition of a relevant C/DOI |

|---|

| Any relationship that could plausibly influence (or could have the appearance of influencing) the direction or strength of 1 or more CPG recommendations |

| C/DOI assessment prior to GDP member selection |

| Potential participants submit details of all relationships—including those with commercial, non-commercial, governmental, and patient/advocacy organizations—for the prior 12-month period |

| When available, publicly available information (eg, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Open Payments database) is collected |

| Limitations on GDP participants with C/DOI |

| Optimally, all GDPs members would be free of relevant C/DOI |

| The GDP Chair and Co-Chair must be free of relevant C/DOI |

| A majority (>50%) of non-Chair GDP members must be free of relevant C/DOI |

| Individuals asked to review CPG drafts as Expert Reviewer or Publisher’s Reviewer must be free of relevant C/DOI |

| GDP members must refrain from adding new relevant industry relationships throughout the CPG-development process |

| C/DOI management |

| Disclosure |

| All C/DOI of each GDP member is disclosed to all GDP members prior to the start of CPG development |

| If any GDP members are aware of potentially undisclosed C/DOI on the part of any GDP member, they are obliged to bring this to the GDP Chair’s attention |

| C/DOI disclosures are updated no less frequently than once a year |

| Divestment |

| GDP members (and their immediate family members) must divest themselves of direct financial investments (eg, direct ownership in stock or other form of equity) with entities having a potential financial interest in the contents of the CPG |

| WC members must refrain from participating in the marketing activities or advisory boards of entities with a potential financial interest in the contents of the CPG |

| Recusals |

| GDP members are required to recuse themselves from all formal decision-making processes for recommendations directly related to their C/DOI |

| GDP members are prohibited from voting on matters directly related to their C/DOI |

| GDP members are prohibited from determining the direction and strength of a recommendation directly related to their C/DOI |

| GDP Chairs may use their discretion to either allow or prohibit GDP members with relevant C/DOI to participate in discussions directly related to their C/DOI |

| GDP members are prohibited from drafting CPG sections directly related to their C/DOI |

| Public transparency |

| Published CPGs will include a table of all relevant C/DOI for GDP members |

| Detailed C/DOI documentation—including all disclosed relationships, CGC determinations regarding relevance, and a description of C/DOI management (as needed)—will be included as supplemental materials |

A link to the full policy may be found at https://www.endocrine.org/clinical-practice-guidelines/methodology

Abbreviations: C/DOI, conflict/duality of interest; CGC, Clinical Guidelines Committee; CPG, clinical practice guideline; GDP, guideline development panel.

The CGC’s C/DOI policy holds that GDP chairs and a majority (greater than 50%) of nonchair GDP members must be free of relevant C/DOI. The CGC aspires to minimize the percentage of GDP members with relevant C/DOI as much as possible, and it will aim for an upper limit of 30%, for 2 primary reasons. Firstly, while the 2011 NAM standards indicate that GDP members with C/DOI “should represent not more than a minority” of the GDPs (1), the 2009 NAM publication regarding C/DOI in medicine explicitly stated that GDP members with C/DOI should represent no more than a “distinct minority (eg, to 25 to 30 percent of the membership)” (28). In addition, the CGC recognizes that there may be times when incomplete disclosure and/or the initiation of new relationships could require the CGC to reclassify a GDP member previously considered to be C/DOI-free: if nearly half of a panel’s members were judged to have relevant C/DOI at the time of GDP assembly, such panel member reclassification could render a majority with relevant C/DOI, in violation of CGC policy. At the time of GDP selection, 31% of Inpatient Hyperglycemia panel members and 31% of Hypoglycemia in Diabetes panel members were judged to have relevant (or potentially relevant) C/DOI, while all Hypercalcemia of Malignancy panel members were judged to be C/DOI free.

Implementation of the new C/DOI policy has been a learning experience for the CGC. For example, 1 panel member from each of the 3 new guidelines initiated industry advisory board participation while on the GDP, in violation of CGC policy. These new activities were not disclosed until after the fact. In 2 cases, the panel members were asked to step down from their GDP, and any GDP judgments that had occurred while such members were on advisory boards were carefully revisited. (No recommendations required revision.) In 1 case, advisory board participation took place after recommendations had been finalized and after the manuscript had been drafted; in this case, the CGC permitted the individual to remain on the GDP and as an author of the guideline, although that panel member was recused from further manuscript editing. With these experiences, CGC leadership acknowledges that it could have reminded GDP members more explicitly and more regularly regarding its C/DOI policy prohibiting specific relationships. The CGC has since implemented a standard practice of briefly summarizing C/DOI rules at the start of every GDP meeting, in addition to regularly reminding panel members to disclose all planned activities prior to initiation, even if felt to be irrelevant by the panel member.

Clinical Practice Guideline–Systematic Review Intersection

The CGC now requires that all guideline recommendations must be underpinned by formal and rigorous systematic evidence reviews. As described above, the Society’s SPI involved an enhanced partnership with the Mayo Clinic’s EBPC and funding to support systematic reviews for 10 clinical questions per guideline. Panels are also permitted to utilize high-quality, up-to-date systematic reviews available in the literature, as long as they meet all standards set by the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research (29). Otherwise, GDPs are restricted to 10 clinical questions for which to make recommendations (30).

In partnership with the Mayo Clinic’s EBPC, the CGC also developed a protocol by which GDP members—experts in their fields of interest—more actively partnered with the EBPC at critical stages of the evidence review process. In essence, 2 panel members were assigned as responsible GDP representatives for each systematic review. These GDP members partnered with the Mayo EBPC to optimize evidence review, and at the following checkpoints, both GDP and EBPC approval was required before proceeding to the next step: (1) articulation of clinical questions; (2) determination of what kinds of study designs will be included in the systematic review; (3) development of search protocols; and (4) establishment of study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, when the Mayo EBPC presented the proposed list of included studies, the assigned GDP representatives at a minimum, but typically the GDP as a whole, carefully reviewed the list prior to finalization. At this stage, the GDP could propose studies that should be included in or excluded from the final list of studies; adjudication of such requests was based on the study eligibility criteria determined a priori.

Establishing Evidence Foundations for and Rating Strength of Recommendations

As per historical practice, and in keeping with GRADE, GDPs will continue to indicate the direction and strength of all recommendations. Each recommendation will also be accompanied by an explanation of the GDP’s justification when determining direction and strength. Panels will provide a concise description of the expected benefits and possible harms of the intervention vis-à-vis its comparator, primarily by summarizing the aggregated scientific evidence and the quality of said evidence. When discussing the results of systematic reviews, panels are asked to adopt standardized, informative language related to the estimated effect size of an intervention as well as the panel’s confidence in that estimate (31). All formal systematic reviews will be provided as supplemental materials or in separate publications.

In addition to the above, panels will now routinely describe the other Evidence-to-Decision criteria important for their judgments: these may include patient values, resource requirements, cost-effectiveness, impact on equity, acceptability, and feasibility of the recommended intervention vis-à-vis its alternative. Whenever possible, panels sought systematic reviews and/or performed their own literature (or other) reviews to establish factual bases for these Evidence-to-Decision criteria. For example, the Chair of the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP organized a systematic review to identify studies reporting on Evidence-to-Decision criteria for the various treatment options being considered by the GDP (32). All GRADE Evidence-to-Decision tables will be provided as supplemental materials, employing standardized language to enhance clarity and reader accessibility (33).

The CGC created a guideline document template for panels to use, primarily to standardize the content of the Society’s CPGs, to help document adherence to GRADE processes, and to help meet NAM standards for trustworthiness. As part of this template, panels are encouraged to explicitly describe the impact of patient values on their judgments. Additional template items that may be addressed in the guideline document could include, among others, substantive dissenting views, whether held by GDP members or by other experts in the field; alternative approaches; potential options for those in resource-constrained settings; applicability (or lack of applicability) of the recommendation to specific patient subgroups and/or different clinical situations; and future research needs.

In general, the CGC now discourages panels from issuing ungraded good practice statements (GPSs), although they are not prohibited. According to the GRADE Working Group, GPSs are most appropriate when GDPs have high confidence—based on a clear and explicit rationale—that indirect evidence would clearly support a large net benefit of an intervention; that issuing the statement explicitly is critical for health care practice; and that it would be a poor use of the panel’s limited resources to engage the processes required for formal grading (34-36). In the case of the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy guideline, the GDP elected to include a number of GPSs, most of which relate to the safe use of antiresorptive medications including bisphosphonates. Compared with formally graded recommendations, GPSs are underpinned by a less rigorous and less transparent process, and thus may be more prone to bias. For this reason, the CGC generally encourages panels to issue GPSs sparingly (34).

Articulation of Recommendations

The CGC’s aspiration is that all of the Society’s guideline recommendations will be clear, concise, and actionable (24). A clear explanation of standardized guideline language is also critical for accurate reader interpretation and for implementation of recommendations as intended by the GDP. Accordingly, the Society’s guidelines will now include tables that more clearly define GRADE terminology related to certainty of evidence (Table 2) (24) and strength of recommendations (Table 3) (37,38).

Table 2.

GRADE certainty of evidence classifications

| Certainty of evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|

|

High

⊕⊕⊕⊕ |

We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect |

|

Moderate

⊕⊕⊕O |

We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

|

Low

⊕⊕OO |

Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

|

Very Low

⊕OOO |

We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Reprinted from Eds. Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, and Oxman A. GRADE Handbook: Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Updated October 2013. (24).

Table 3.

Summary of GRADE strength of recommendation classifications

| Strength of recommendation | Criteria | Interpretation by patients | Interpretation by healthcare providers | Interpretation by policy makers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Strong recommendation for or against | Desirable consequences CLEARLY OUTWEIGH the undesirable consequences in most settings (or vice versa). | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not. | Most individuals should follow the recommended course of action. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individual patients make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. |

The recommendation can be adopted as policy in most situations. Adherence to this recommendation according to the guideline could be used as a quality criterion or performance indicator. |

| 2—Conditional recommendation for or against | Desirable consequences PROBABLY OUTWEIGH undesirable consequences in most settings (or vice versa). | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. | Clinicians should recognize that different choices will be appropriate for each individual and that clinicians must help each individual arrive at a management decision consistent with the individual’s values and preferences. Decision aids may be useful in helping patients make decisions consistent with their individual risks, values and preferences. |

Policy-making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Performance measures should assess whether decision making is appropriate. |

Adapted from Schünemann HJ et al. Blood Adv, 2018; 2(22) © by The American Society of Hematology. (38).

Guideline Updating

The Society periodically updates its guidelines, as it is currently doing with 2 of the new guidelines: Inpatient Hyperglycemia updates a 2012 guideline (39), and Hypoglycemia in Diabetes will update a 2009 guideline (40). The CGC has historically been reluctant to retire one of its guidelines until a formal update has been published. In 2020, however, the CGC adopted a newly standardized process by which all active guidelines are formally assessed by the CGC and a GDP representative—often the GDP’s chair—on an annual basis. This annual review focuses on the potential emergence of new evidence that could materially alter the net benefit of recommended interventions vis-à-vis all available alternatives. (Importantly, the CGC determined that elapsed time alone should not be a firm criterion for retiring and/or updating a guideline.) In light of such assessments, the CGC will make annual decisions regarding whether to affirm or retire each of its guidelines. In 2021, the Society’s BOD approved a CGC recommendation to retire 4 guidelines without immediate replacement because, in the CGC’s judgment, the guidelines were outdated and/or supplanted by other guidelines (41-44).

At the time of this writing, the Society has 32 active guidelines. Endocrine Society resources currently permit the development of 6 guidelines at any given time, whether they be new guidelines or guideline updates. Since the CGC determined that all future guideline development should faithfully adhere to GRADE, updates to previously published guidelines will require de novo development, which typically requires 2 to 3 years.

The CGC continues to actively consider the best approaches to timely guideline updating. The CGC is currently exploring the possibility of providing focused updates when needed: for example, when a guideline has been created in accordance with the CGC’s revised policies, targeted updates could be implemented by adding or updating systematic reviews and Evidence-to-Decision frameworks for selected clinical questions. As an exploratory step in this direction, a targeted update was recently issued for the Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women guideline (45).

Enhancing Guideline Trustworthiness: Practical Implications

The CGC recognizes that, compared with previous guidelines, recently implemented policy and methodological changes will manifest as noticeable changes to the Society’s guideline documents. Here we describe the changes that readers are most likely to notice.

Many of the Society’s prior guidelines provided comprehensive guidance for a given topic. Because the CGC now mandates that each formal recommendation must be underpinned by systematic evidence review, and because the Society and EBPC provide systematic review support for 10 clinical questions per guideline, GDPs must carefully prioritize the top clinical questions for which guidance is most needed. Accordingly, the CGC anticipates that the Society’s new guidelines will contain fewer recommendations than its prior guidelines. In essence, the CGC and the Society have prioritized methodological rigor over comprehensiveness.

The CGC’s new policy requiring that each formal recommendation must be supported by formal systematic review has additional important consequences. For example, the Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP and the CGC wrestled with how to address the prior guideline’s clinical questions and recommendations (39) that were not formally addressed in the updated guideline. The GDP judged that many of the previous guideline’s recommendations remained accurate and important. However, the CGC did not permit the Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP to formally endorse prior recommendations, maintaining that formal endorsement would require either new or updated systematic reviews. As another example, the Society’s 2009 Evaluation and Management of Adult Hypoglycemic Disorders guideline included guidance related to hypoglycemia in patients without diabetes (40). The current Hypoglycemia in Diabetes GDP necessarily focused its work more narrowly given its limit on clinical questions (systematic reviews). Therefore, this soon to be published CPG update will not address nondiabetes-related hypoglycemia. The CGC recognizes that these examples highlight important tradeoffs attending its new policy.

The CGC anticipates that GDPs will tend to prioritize clinical questions relating to issues for which the existing data are not completely clear, but where guidance is needed. For this reason, the CGC anticipates that fewer of its guideline recommendations will be strong recommendations. For example, the vast majority (93%) of recommendations in the Inpatient Hyperglycemia CPG are conditional recommendations (2). This is in contrast to past guidelines, at least those published from 2005 to 2011, for which 58% of recommendations were strong (46). In the case of Inpatient Hyperglycemia, the paucity of strong recommendations in part reflected the availability of only low- or very-low–quality evidence: it is very difficult for a GDP to conclude that the desirable consequences of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable consequences if the GDP simultaneously has limited confidence in the outcome effect estimates for that intervention. Nonetheless, in a limited number of scenarios, strong recommendations can be justified even in the setting of low- or very-low–quality evidence (15).

For each clinical question, GDPs will limit the number of outcomes to be assessed to no more than 5 or 7. The rationale for this limit is 2-fold. Most importantly, it is difficult to weigh more than 5 to 7 outcomes simultaneously. Secondly, as a practical limitation, every assessed outcome effectively necessitates its own systematic review, straining feasibility. This limit will require GDPs to prioritize the outcomes that will be assessed in systematic reviews, focusing on those outcomes judged to be critical for panel decision-making (12,30). As a result, it is possible that some outcomes of interest to readers will not be formally incorporated into GDP deliberations.

The Society’s guidelines will no longer provide long-form descriptions of clinical research studies in the main guideline document. Instead, the primary guideline document will include high-level summaries of the evidence, including estimated effect sizes of interventions and descriptions of panel certainty in those estimates. The CGC has requested that panels generally avoid providing detailed descriptions of individual studies. Highly detailed systematic reviews will be provided in supplemental materials and/or as separate publications, in addition to evidence profiles and summary-of-findings tables.

Guideline manuscripts will now include descriptions of other Evidence-to-Decision criteria that informed GDP judgements. In addition, as described above, all Evidence-to-Decision tables—a new requirement for the Society’s guidelines—will be made available in supplemental materials.

Conclusions

Herein we have described some of the Society’s recent, good-faith efforts to enhance the trustworthiness of its CPGs. The Society recognizes the need to continually strive for improvement, in keeping with an approach described by the NAM: “Some guideline developers will readily adapt their development process to embrace these eight standards; however, . . . a process of evolutionary adoption over time may be more practical” (1). For example, the CGC is currently exploring ways to enhance patient input (patient voice) into the guideline development process; ways to better incorporate diversity, equity, and inclusion considerations into guideline development; and best practices for updating its CPGs in a timely fashion. The Society commits to producing guidelines that are as trustworthy as possible, and it invites its membership to provide input into the best ways to do so.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the work of the 2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force: Tobias Else (Co-Chair), Clifford Rosen (Co-Chair), Ulla Feldt-Rasmussen, Rita Kalyani, Kathryn Martin, Christopher McCartney, Cacia Soares-Welch, and Helena Teede, supported by Endocrine Society Staff members Andrea Hickman, Robert Lash, and Melanie Stephens-Lyman. We also express our appreciation for those serving on the CGC who have engaged these guideline improvement projects with great earnestness. Since 2016, these members have been as follows: Jessica Castle, Ellen Connor, Angela Cheung, Tobias Else, Elizabeth Fasy, Maria Fleseriu (Chair 2015-2018), Sabrina Gill, Kristen Hairston, Frances Hayes, Rita Kalyani, Christian Koch, Rosemarie Lajara, Sandra Licht, Ana Luzia Maia, Christopher McCartney (Chair 2018-2021), Marie McDonnell (Chair 2021-2024), Deborah Merke, John Newell-Price (member and BOD Liaison), Avin Pothuloori, Yumie Rhee, Clifford Rosen (BOD Liaison), Dennis Styne, and Tamara Wexler. We will be forever grateful to the Endocrine Society staff who support the guideline program: Maureen Corrigan, Director of Clinical Practice Guidelines (2019 to present); Cassandre Destin, Education Specialist (2017-2020); Andrea Hickman, Manager of Clinical Practice Guidelines (2017 to present); Robert Lash, Chief Medical Officer (2018 to present); and Melanie Stephens-Lyman, Director of Clinical Practice Guidelines (2016-2019). All have worked tirelessly to enhance the trustworthiness of the Society’s guidelines. We offer our enduring gratitude to the patient representative members of our guideline development panels: Claire Pegg (USA) was recruited via the Diabetes Patient Advocacy Coalition (diabetespac.org) to participate in the Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP; and Robin Fein Wright (USA) was recruited via DiabetesSisters (diabetessisters.org) to participate in the Hypoglycemia in Diabetes GDP. Mr. Freddy Smith (USA) was recruited by a GDP member to participate in the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP; unfortunately, Mr. Smith died prior to the first consensus meeting. Finally, we thank Daniele Matellini (Italy), Lina Sioufi (Lebanon), Freddy Smith (USA), and Alberto Zendri (Italy)—patients who completed surveys that helped the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP prioritize patient-important outcomes.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BOD

Board of Directors

- C/DOI

conflict/duality of interest

- CGC

Clinical Guidelines Committee

- CPG

clinical practice guideline

- CPGTF

Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force

- EBPC

Evidence-Based Practice Center

- GDP

guideline development panel

- GPS

good practice statement;

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- NAM

National Academy of Medicine

- NEATS

National Guideline Clearinghouse Extent Adherence to Trustworthy Standards

- NGC

National Guideline Clearinghouse

- SPI

Strategic Plan Business Plan and Investment Request

- TRUST

Transparency and Rigor Using Standards of Trustworthiness

Contributor Information

Christopher R McCartney, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA.

Maureen D Corrigan, Endocrine Society, Washington, DC 20036, USA.

Matthew T Drake, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, Metabolism and Nutrition, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55902, USA.

Ghada El-Hajj Fuleihan, Division of Endocrinology, Calcium Metabolism and Osteoporosis Program, World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Metabolic Bone Disorders, Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, 1107 2020, Lebanon.

Mary T Korytkowski, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA.

Robert W Lash, Endocrine Society, Washington, DC 20036, USA.

David C Lieb, Division of Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, Department of Internal Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA 23501-1980, USA.

Anthony L McCall, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Medicine, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA.

Ranganath Muniyappa, Clinical Endocrinology Section, Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Obesity Branch, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Thomas Piggott, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8, Canada; Michael G. DeGroote Cochrane Canada and McMaster GRADE Centres, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada.

Nancy Santesso, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8, Canada; Michael G. DeGroote Cochrane Canada and McMaster GRADE Centres, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada.

Holger J Schünemann, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8, Canada; Michael G. DeGroote Cochrane Canada and McMaster GRADE Centres, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada; Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada.

Wojtek Wiercioch, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4L8, Canada; Michael G. DeGroote Cochrane Canada and McMaster GRADE Centres, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4L8, Canada.

Marie E McDonnell, Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA.

M Hassan Murad, Evidence-Based Practice Center, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55902, USA.

Financial Support

The development of Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines and systematic reviews are supported exclusively by the Endocrine Society.

Author Roles

Christopher R. McCartney, 2018-2021 CGC Chair; Maureen D. Corrigan, Director of Clinical Practice Guidelines; Matthew T. Drake, Co-Chair of the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP; Ghada El-Hajj Fuleihan, Chair of the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP; Mary T. Korytkowski, Chair of the Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP; Robert W. Lash, Endocrine Society Chief Medical Officer; David C. Lieb, Co-Chair of the Hypoglycemia in Diabetes GDP; Anthony L. McCall, Chair of the Hypoglycemia in Diabetes GDP; Ranganath Muniyappa, Co-Chair of the Inpatient Hyperglycemia GDP; Thomas Piggott, McMaster guideline methodologist for the Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDP; Nancy Santesso, McMaster guideline methodologist for the Inpatient Diabetes GDP; Holger J. Schünemann, McMaster lead for the McMaster–Endocrine Society partnership; Wojtek Wiercioch, McMaster guideline methodologist for the Hypoglycemia in Diabetes GDP; Marie E. McDonnell, 2021-2024 CGC Chair; M. Hassan Murad, guideline methodologist and systematic review lead for the Inpatient Hyperglycemia, Hypoglycemia in Diabetes, and Hypercalcemia of Malignancy GDPs.

Disclosures

C.R.M., M.D.C., M.T.D., G.E.F., M.T.K., R.W.L., A.L.M., R.M., and M.E.M. have nothing to declare. D.C.L. is a member of the Clinical Practice Guideline Committee, chairs the Education Oversight Committee, and is an ex-officio member of the Board of Directors for the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology. M.H.M. is a methodology consultant for the Endocrine Society, American Society of Hematology, CHEST, Society for Vascular Surgery, and World Health Organization; he is also a board member of the Evidence Foundation. T.P., N.S., H.J.S., W.W., and M.H.M. are members of the GRADE Working Group. HJS is Co-Chair of the GRADE Working Group. McMaster University received a research contract for its work to support the Endocrine Society’s guideline methodology.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Greenfield S, Steinberg E, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Korytkowski M, Muniyappa R, Antinori-Lent K, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care settings: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Woolf SH. Practice guidelines, a new reality in medicine. II. Methods of developing guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(5):946-952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murad MH. Clinical practice guidelines: a primer on development and dissemination. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):423-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schunemann HJ, Best D, Vist G, Oxman AD, Group GW. Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;169(7):677-680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328(7454):1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. GRADE. Working group is the title of the website. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org

- 8. Swiglo BA, Murad MH, Schunemann HJ, et al. A case for clarity, consistency, and helpfulness: state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines in endocrinology using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):666-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Molitch ME, Clemmons DR, Malozowski S, Merriam GR, Shalet SM, Vance ML; Endocrine Society’s Clinical Guidelines Subcommittee. Evaluation and treatment of adult growth hormone deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91(5):1621-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(6):1995-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wierman ME, Basson R, Davis SR, et al. Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3697-3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):395-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Sultan S, et al. GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(2):151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrews JC, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(7):726-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, et al. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;72:45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fleseriu M, Hashim IA, Karavitaki N, et al. Hormonal replacement in hypopituitarism in adults: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):3888-3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jue JJ, Cunningham S, Lohr K, et al. Developing and testing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse Extent of Adherence to Trustworthy Standards (NEATS) instrument. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(7):480-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ECRI. ECRI Institute Opens Access to Clinical Practice Guidelines. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.ecri.org/press/ecri-institute-opens-access-to-clinical-practice-guidelines

- 20. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1595-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. ECRI. ECRI Guidelines Trust Inclusion Criteria. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://guidelines.ecri.org/inclusion-criteria

- 22. Barrionuevo P, Kapoor E, Asi N, et al. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women: a network meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(5):1623-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I, et al. Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. Can Med Assoc J. 2014;186(3):E123-E142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schünemann HJ, Brożek J, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, eds; Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group. GRADE Handbook:Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. 2013. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html#h.9rdbelsnu4iy

- 25. Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Endocrine Society. Conflict of Interest Policy & Procedures for Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://www.endocrine.org/clinical-practice-guidelines/methodology

- 28. Committee on Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Lo B, Field MJ, eds. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Eden J, Levit L, Berg A, Morton S, eds. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiercioch W, Nieuwlaat R, Zhang Y, et al. New methods facilitated the process of prioritizing questions and health outcomes in guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;143:91-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Santesso N, Glenton C, Dahm P, et al. ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE guidelines 26: informative statements to communicate the findings of systematic reviews of interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;119:126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bassatne A, Rahme M, Piggott T, Murad MH, Hneiny L, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. Values and other decisional factors regarding treatment of hypercalcaemia of malignancy: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11(10):e051141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piggott T, Baldeh T, Dietl B, et al. Standardized wording to improve efficiency and clarity of GRADE EtD frameworks in health guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;146:106-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guyatt GH, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, et al. Guideline panels should seldom make good practice statements: guidance from the GRADE Working Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;80:3-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dewidar O, Lotfi T, Langendam MW, et al. ; eCOVID-19 Recommendations Map Collaborators. Good or best practice statements: proposal for the operationalisation and implementation of GRADE guidance. BMJ Evid Based Med 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dewidar O, Lotfi T, Langendam M, et al. , eCOVID-19 recommendations map collaborators. Which actionable statements qualify as good practice statements in Covid-19 guidelines? A systematic appraisal. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2022;bmjebm-2021-111866. Doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, Schunemann HJ, Grade Working Group. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7652):1049-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Umpierrez GE, Hellman R, Korytkowski MT, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients in non-critical care setting: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):16-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cryer PE, Axelrod L, Grossman AB, et al. Evaluation and management of adult hypoglycemic disorders: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3): 709-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Corrigendum to: “Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6): e2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corrigendum to: “Continuous glucose monitoring: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6):e2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Corrigendum to: “Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6): e2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Corrigendum to: “Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline.” J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(6):e2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Eastell R. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society guideline update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(3):dgaa048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Brito JP, Domecq JP, Murad MH, Guyatt GH, Montori VM. The Endocrine Society guidelines: when the confidence cart goes before the evidence horse. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8): 3246-3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.