Abstract

Objectives:

CMV viremia is associated with increased mortality in persons with HIV. We previously demonstrated that CMV viremia was a risk factor for 10-week mortality in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve persons with cryptococcal meningitis. We investigated whether similar observations existed over a broader cohort of patients with HIV-associated meningitis at 18 weeks.

Methods:

We prospectively enrolled Ugandans with cryptococcal or TB meningitis into clinical trials in 2015–2019. We quantified CMV DNA concentrations from stored baseline plasma or serum samples from 340 participants. We compared 18-week survival between those with and without CMV viremia.

Results:

We included 308 persons with cryptococcal meningitis and 32 with TB meningitis, of whom 121 (36%) had detectable CMV DNA. Baseline CD4+ T-cell counts (14 vs. 24 cells/μl; P = 0.07) and antiretroviral exposure (47% vs. 45%; P = 0.68) did not differ between persons with and without CMV viremia. The 18-week mortality was 50% (61/121) in those with CMV viremia versus 34% (74/219) in those without (P = 0.003). Detectable CMV viremia (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.60; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.13–2.25; P = 0.008) and greater viral load (aHR 1.22 per log10 IU/ml increase; 95% CI 1.09–1.35; P <0.001) were positively associated with all-cause mortality through 18 weeks.

Conclusion:

CMV viremia at baseline was associated with a higher risk of death at 18 weeks among persons with HIV-associated cryptococcal or TB meningitis, and the risk increased as the CMV viral load increased. Further investigation is warranted to determine whether CMV is a modifiable risk contributing to deaths in HIV-associated meningitis or is a biomarker of immune dysfunction.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, HIV, CMV, Cryptococcal meningitis, Tuberculous meningitis

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are common causes of HIV-associated meningitis and result in high mortality in persons with advanced HIV disease, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ellis et al., 2019; Rajasingham et al., 2017; Tenforde et al., 2020). Interest exists in identifying modifiable risk factors contributing to the high mortality observed with advanced HIV. One underexplored area is the impact that frequently undiagnosed concomitant opportunistic infections may have on persons with HIV-associated meningitis.

CMV is a human herpesvirus that commonly causes lifelong latent infection but may reactivate in persons who are immuno-compromised (Gianella and Letendre, 2016; Springer and Weinberg, 2004). CMV immunoglobulin (IgG) seropositivity is typically >90% in adult South Americans (de Matos et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2010; Tuon et al., 2019), Asian (Choi et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017), and African (Compston et al., 2009; Grønborg et al., 2017) populations; it reaches essentially 100% in Africans with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis (Skipper et al., 2020). The presence of detectable CMV viremia increases with decreasing CD4+ T-cell count, with a reported prevalence ranging from 23–55% in persons who are HIV-positive and have CD4+ T-cell counts ≤100 cells/μl (Brantsæter et al., 2012; Durier et al., 2013; Fielding et al., 2011; Jabbari et al., 2021; Micol et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2019). In our 2010–2013 Uganda and South Africa study, we reported that 52% of antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve adults with first-episode cryptococcal meningitis (median CD4+ T-cell count = 19 cells/μl) had detectable CMV DNA (median viral load = 498 IU/ml [interquartile range {IQR} 259–2390]) in plasma (Skipper et al., 2020). We demonstrated that CMV viremia is associated with a ∼two-fold greater mortality rate (hazard ratio [HR] 2.19; 95% CI 1.07–4.49) in ART-naïve persons with first-episode cryptococcal meningitis compared with those without detectable CMV viremia (Skipper et al., 2020). Detectable CMV viremia has been repeatedly demonstrated as a risk factor for mortality in persons with HIV across multiple continents and eras of ART use (Deayton et al., 2004; Durier et al., 2013; Fielding et al., 2011; Spector et al., 1998). However, it is unknown whether CMV is driving this risk or rather serves as a marker of a dysfunctional immune response to the primary opportunistic infection.

We designed this study to validate our previous findings in a larger population and expand our cohort to include: (1) ART-experienced patients with cryptococcal meningitis and (2) ART-naïve and ART-experienced patients with TB meningitis. Similar to cryptococcal meningitis, TB meningitis predominantly affects persons with low CD4+ T-cell counts. However, it can occur with any CD4+ T-cell count and in individuals without HIV. High levels of CMV IgG antibody are associated with a 3.4-fold increased risk of developing tuberculosis (Stockdale et al., 2020). Additionally, data from South Africa demonstrated a trend toward increased mortality in persons (particularly those age >35) with non-central nervous system tuberculosis and HIV and who also had CMV viremia (Ward et al., 2016). Future clinical trials of CMV antivirals may provide insight into whether CMV viremia is a modifiable risk factor in these patient populations.

Methods

Study population and setting

We retrospectively quantified CMV DNA concentrations from participants with HIV-associated cryptococcal or TB meningitis previously enrolled in our prospective longitudinal cohort, which spanned the time of two clinical trials. The Adjunctive Sertraline for the Treatment of HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis (ASTRO-CM) trial (NCT01802385) was a randomized clinical trial testing whether sertraline added to standard-of-care cryptococcal meningitis treatment improved survival (Rhein et al., 2019). The ASTRO-CM trial enrolled participants with cryptococcal meningitis from Mulago and Mbarara Hospitals in Uganda from March 2015 to May 2017. The diagnosis was by cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay (IMMY, Norman, OK, USA) (Boulware et al., 2014b). Induction therapy consisted of amphotericin B deoxycholate (0.7–1.0 mg/kg/day) plus fluconazole (800 mg/day) for up to 2 weeks and was followed by fluconazole consolidation and maintenance therapy. Participants were randomized to additionally receive sertraline (400 mg/day) for 2 weeks, followed by sertraline (200 mg/day) or a matching placebo for an additional 12 weeks. All participants received supportive care (electrolyte monitoring/replacement) and therapeutic lumbar punctures to control elevated intracranial pressure as needed. Survival at 18 weeks was the primary endpoint of the ASTRO-CM trial. The study demonstrated no survival difference between the adjunctive sertraline and placebo groups (Rhein et al., 2019).

The High-dose Oral and Intravenous Rifampicin for Improved Survival of Adult Tuberculous Meningitis (RifT) trial (IS-RCTN42218549) evaluated whether high-dose rifampicin resulted in higher CSF drug concentrations compared with standard-of-care dosing in persons with TB meningitis (Cresswell et al., 2021). The trial enrolled participants with suspected or confirmed TB meningitis from Mulago and Mbarara Hospitals in Uganda from January 2019 to December 2019. All participants received daily oral isoniazid (5 mg/kg/day), pyrazinamide (25 mg/kg/day), ethambutol (20 mg/kg/day), and dexamethasone (0.4 mg/kg/day, followed by an 8-week taper). Participants were randomized in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive standard-dose oral rifampicin (10 mg/kg/day), high-dose oral rifampicin (35 mg/kg/day), or high-dose intravenous rifampicin (20 mg/kg/day). Survival at 24 weeks was a secondary outcome for the RifT trial. Survival rates did not statistically differ, though this pharmacokinetic trial was not powered to determine survival differences among the three groups (Cresswell et al., 2021).

Participants enrolled in the ASTRO-CM trial had stored baseline plasma available for CMV DNA quantification, whereas those enrolled in the RifT trial had stored baseline serum available. We shipped all available frozen, stored samples from Uganda to Minneapolis in February 2020.

DNA extraction and PCR

We performed DNA extraction from 200 μl of plasma or serum using the QIAcube HT (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and QIAamp 96 Virus DNA QIAcube kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Multiplex quantitative PCR was performed using the Light-Cycler 480 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and UL83-targeted primers (Dollard et al., 2021). Detailed PCR methods can be found in the Supplementary Methods. Laboratory staff processed deidentified samples and were blinded to participant data and outcome. CMV DNA quantification values in copies/ml were converted to IU/ml using the 1st WHO International Standard for Human Cytomegalovirus for Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques (NIBSC code 09/162) as controls for CMV viral load WHO, 2014).

Statistical analysis

We defined CMV viremia as CMV DNA in plasma or serum at any quantity above the detection threshold in the PCR assay, which was 88.5 IU/ml (Levi et al., 2022). For this study, we considered any sample within 14 days of meningitis diagnosis to be a baseline sample. Baseline characteristics were compared by CMV viremia status, CMV viral load group, and meningitis subgroup using chi-square or Kruskal-Wallis testing. The primary outcome in our analysis was 18-week all-cause mortality in those with HIV-associated cryptococcal or TB meningitis, which we will hereafter refer to also as HIV-associated meningitis. Survival was calculated in days from the date of meningitis diagnosis until either death, loss to follow-up, or 18 weeks. We chose 18 weeks of follow-up because 95% of the 5-year mortality occurs within the first 18 weeks after cryptococcal meningitis diagnosis (Butler et al., 2012). We analyzed the impact of CMV viremia both as a binary variable (present versus absent) and as a continuous variable using log10-transformed CMV viral load in our survival models. We additionally considered categorical variables of (1) no CMV viremia; (2) CMV DNA concentrations <1000 IU/ml (low-grade viremia); (3) CMV DNA 1000–5000 IU/ml (moderate-grade viremia); and (4) CMV DNA >5000 IU/ml (high-grade viremia) to further assess how the magnitude of viremia impacted mortality at clinically useful cutoffs. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models evaluated risk factors for 18-week mortality. We reported HRs, 95% CIs, and P-values for each analysis. Seven participants were lost to follow-up and were right-censored before 18 weeks in the time-to-event model. For eight participants missing CD4+ T-cell counts, we imputed the median CD4+ T-cell count for the type of meningitis. We then performed multivariate adjustment in two different proportional hazards models. The goal of the first model set (Table 2) was to maintain all 340 participants and adjust for what we considered the two most important potential confounders: CD4+ T-cell count and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of <15. CD4+ T-cell count is important because it is traditionally correlated with the risk of reactivation of CMV. GCS score <15 has traditionally been a significant risk factor for mortality in persons with HIV-associated meningitis (Hakyemez et al., 2018; Lofgren et al., 2017; Tugume et al., 2019). The goal of the second model set (Supplementary Table 3b) was to adjust for all potential confounders at the expense of sample size loss secondary to missing data. Supplementary Table 3a includes the list of all variables included in the full covariate model and their univariate HRs. We subsequently performed a sensitivity analysis comparing CMV-related mortality by subgroup (cryptococcal meningitis or TB meningitis). All statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 2.

Mortality at 18 weeks by meningitis subgroup in Cox regression model

| Overall |

Cryptococcal meningitis |

TB meningitis |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio(95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio(95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio(95% CI) | P-value | |

| Participants | 340 | 308 | 32 | |||

| Univariate analyses | ||||||

| CMV viremia present | 1.66 (1.18–2.33) | 0.003 | 1.48 (1.04–2.09) | 0.03 | 17.1 (2.04–142.6) | 0.009 |

| log10 CMV DNA IU/ml per log increase | 1.24 (1.11–1.38) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.07–1.33) | 0.002 | 2.59 (1.45–4.62) | 0.001 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.87–1.31) | 0.54 | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.61 | 1.05 (0.46–2.42) | 0.90 |

| Female | 0.95 (0.67–1.35) | 0.77 | 1.00 (0.70–1.44) | 0.98 | 0.69 (0.15–3.08) | 0.63 |

| CD4+ T-cell count per 10 cell/μl | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 0.15 | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | 0.43 | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.64 |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score <15 | 1.58 (1.12–2.21) | 0.008 | 1.88 (1.33–2.67) | <0.001 | ∞ | |

| Multivariable model #1 | ||||||

| CMV viremia present | 1.60 (1.13–2.25) | 0.008 | 1.43 (1.00–2.04) | 0.05 | 29.2 (2.89–294.6) | 0.004 |

| Multivariable model #2 | ||||||

| log10 CMV DNA IU/mL, per log increase | 1.22 (1.09–1.35) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.05–1.31) | 0.004 | 4.87 (1.75–11.5) | 0.002 |

The median CMV DNA concentration was 2.66 (IQR 2.15–3.39; maximum 7.00) log10 IU/ml. All persons with TB meningitis and GCS <15 died, leading to a hazard ratio that approaches infinity; P-values are not valid in such situations. The median CD4+ T-cell count was 16 cells/μl (IQR 7–49) in the cryptococcal meningitis group was and 107 cells/μl (IQR 45–273) in TB meningitis group.

Multivariable Models #1 and #2 adjust for age, sex, CD4+ T-cell count per 10 cells/μl, and Glasgow Coma Scale score <15. CMV log10 increase (as a continuous variable) had a similar but marginally better relative model fit by AIC test compared with CMV viremia present (as a categorical variable) (AIC 1491 vs. 1496, respectively).

AIC, Akaike information criterion; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range

Ethical approval

The parent trials received institutional review board approval from the appropriate US, UK, and Ugandan institutions, including the Uganda National Drug Authority and Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. All trial participants provided written informed consent for the storage and future testing of samples for research purposes.

Results

We included 308 persons with cryptococcal meningitis and 32 persons with TB meningitis in this CMV substudy for a total analysis cohort of 340 participants. The study cohort comprised 61% men; the median age of participants was 35 years (interquartile range [IQR] 30–40). The median CD4+ T-cell count was 14 cells/μl (IQR 6–53) for persons with CMV viremia versus 24 cells/μl (IQR 8–61) in persons without viremia (P = 0.07). In all, 121 (36%) had detectable CMV viremia at baseline, with a median CMV viral load of 452 IU/ml (IQR 142–2450; range 119–10 million). We compared baseline characteristics by CMV viremia status (Table 1). Persons with CMV viremia were noted to have lower hemoglobin values and were less likely to mount a white blood cell response in the CSF. Most baseline samples tested for CMV DNA were collected within 3 days of meningitis diagnosis (91% [309/340]), and 279 (82%) were collected on the same day as diagnosis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by CMV viremia status

| CMV viremia present | CMV viremia absent | P-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N per group | 121 | 219 | |

| Women | 52 (43%) | 81 (37%) | 0.28 |

| Age, years | 35 [29–40] | 35 [30–40] | 0.63 |

| CD4+ T-cell count per μl | 14 [6–53] | 24 [8–61] | 0.07 |

| CD4:CD8 ratio | 0.1 [0.0–0.1] | 0.1 [0.0–0.1] | 0.73 |

| Receiving ART | 57 (47%) | 98 (45%) | 0.68 |

| Months on ART | 2.5 [0.5–20] | 3.8 [1.1–32] | 0.22 |

| CMV DNA, IU/ml | 452 [142–2450] | 0 [0–0] | |

| Glasgow Coma Scale score <15 | 49 (41%) | 88 (40%) | 0.95 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 11.0 [9.5–12.6] | 11.6 [10.3–13.0] | 0.01 |

| CSF white cells ≤5 cells/μl | 85 (73%) | 126 (60%) | 0.03 |

| CSF opening pressure, mmH2 0 | 260 [180–370] | 270 [170–410] | 0.52 |

| Randomized to Intervention | 76 (63%) | 151 (69%) | 0.07 |

| Meningitis | 0.59 | ||

| Cryptococcal meningitis (N = 308) | 111 (36%) | 197 (64%) | |

| TB meningitis (N = 32) | 10 (31%) | 22 (69%) |

Data are N (%) or median [interquartile range].

P-values are from chi-square or Kruskal-Wallis testing.ART, antiretroviral therapy; mmH2 0, millimeters of water.

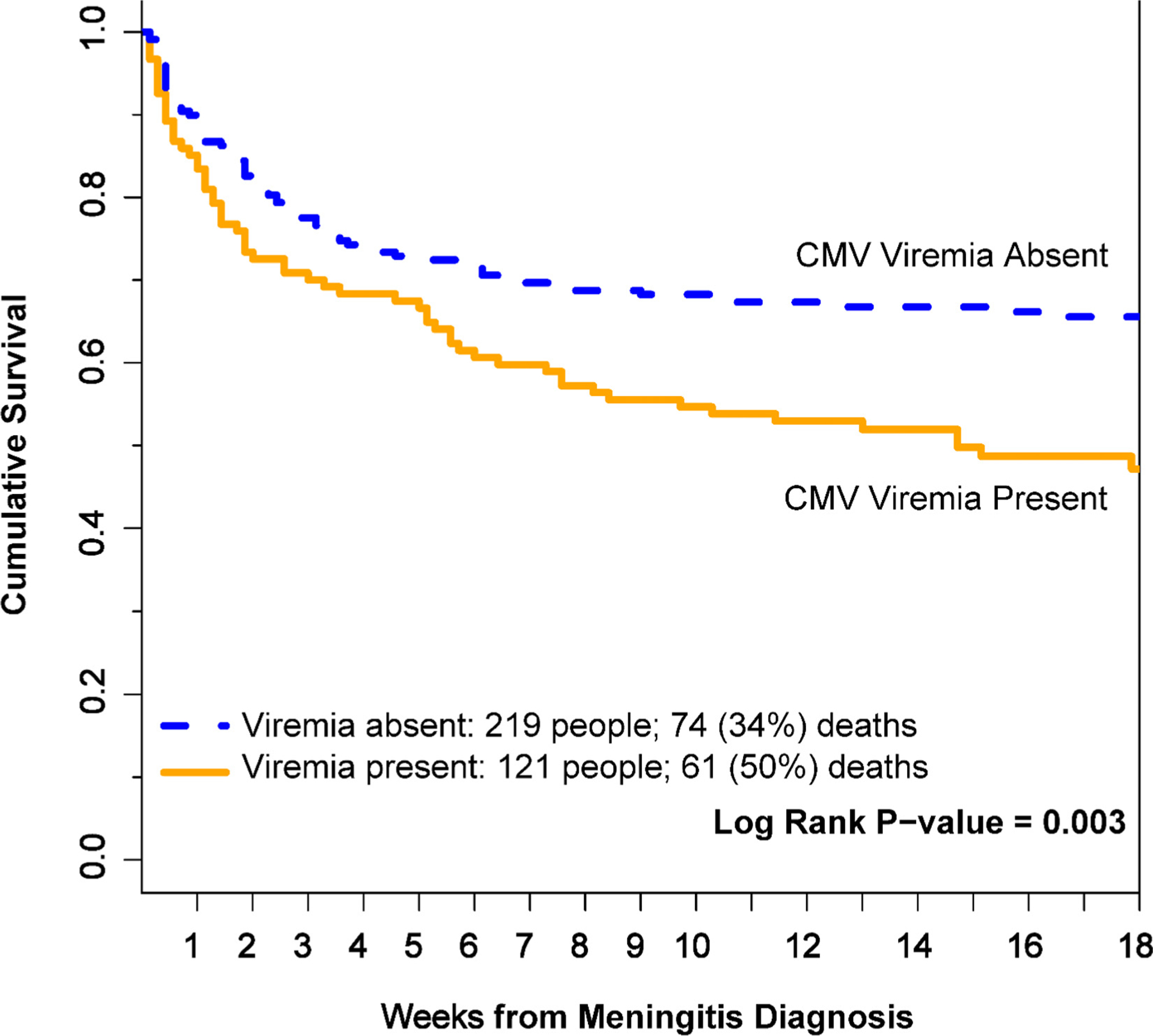

Overall, mortality at 18 weeks was 50% (61/121) in those with CMV viremia versus 34% (74/219) in those without CMV viremia (P = 0.003) (Figure 1). In a univariate proportional hazards model, the presence of CMV viremia was associated with a two-thirds greater risk (HR 1.66; 95% CI 1.18–2.33; P = 0.003) for death through 18 weeks (Table 2). When assessing the impact of greater CMV viral load, we found an HR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.11–1.38; P<0.001) per one log10 IU/mL increase in CMV DNA concentration. Thus, both the presence of any detectable CMV DNA and increasing levels of CMV DNA at baseline were associated with higher 18-week mortality before the adjustment in HIV-associated meningitis.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier 18-week survival curves by CMV viremia status. Persons with CMV viremia were more likely to die at 18 weeks than persons without CMV viremia. Seven participants were right-censored before 18 weeks for transfer of care. Figure does not include any multivariate adjustments. P-value calculated by log-rank testing.

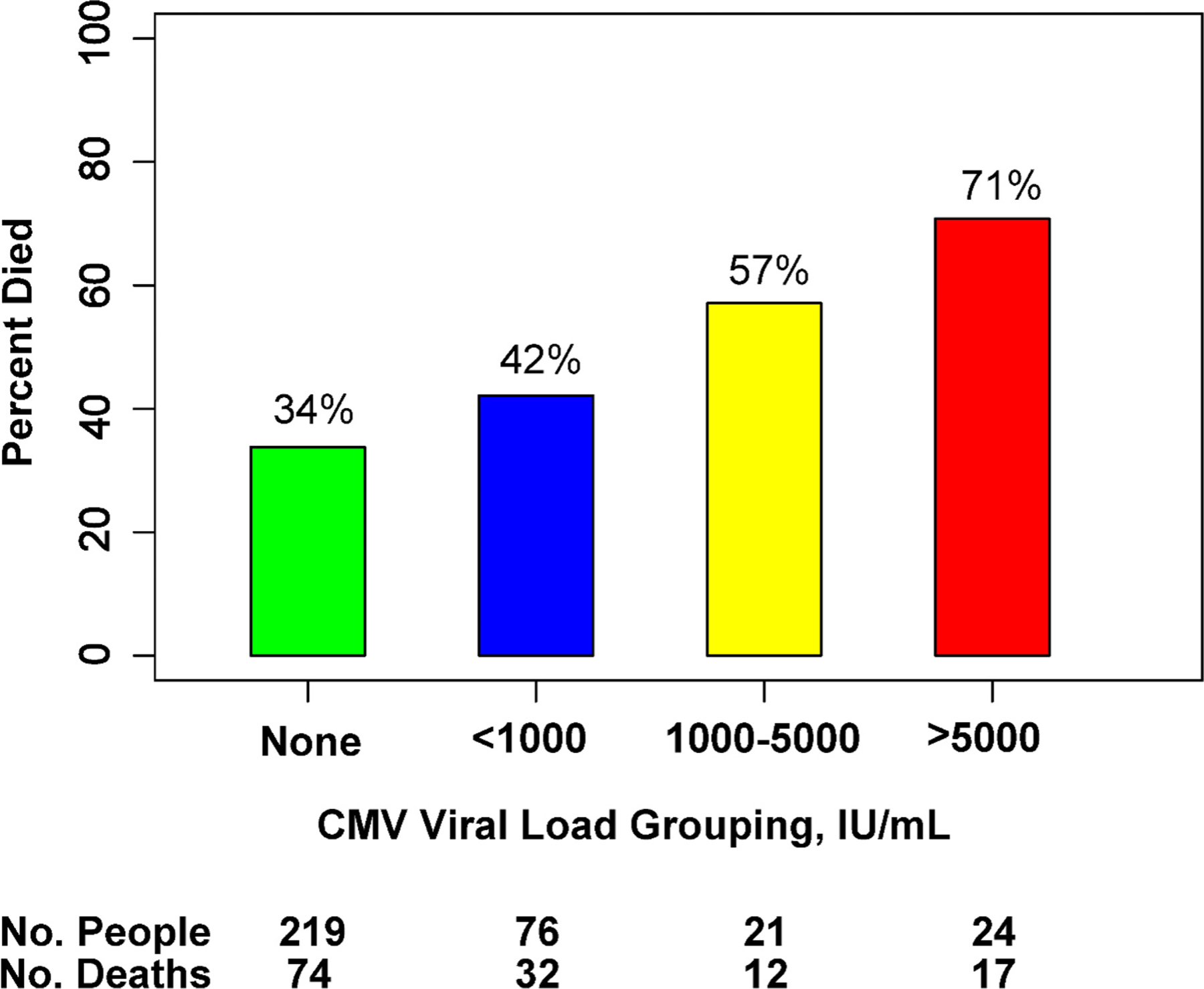

We further stratified CMV viral load into low-grade viremia (<1000 IU/ml), moderate-grade viremia (1000–5000 IU/ml), and high-grade viremia (>5000 IU/ml) groups to observe how mortality associated with the magnitude of CMV viremia at clinically useful thresholds. Of the 121 participants with CMV viremia, 76 (63%) had low CMV viral loads (median 188 IU/ml [IQR 129–354]), 21 (17%) had moderate CMV viral loads (median 1750 IU/ml [IQR 1200–2740]), and 24 (20%) had high CMV viral loads (median 9970 IU/ml [IQR 6750–62,100]). Baseline characteristics were similar among the viral load groups, although a trend of declining CD4+ T-cell count was noted as CMV viral load increased (Supplementary Table 1). Mortality was highest in the high CMV viral load group (71% [17/24]) and decreased along with viral load in the corresponding groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Death within 18 weeks by CMV viral load group. Figure demonstrating the proportion of participants who died by 18 weeks grouped by level of CMV viral load, in IU/ml. Chi-square P-value = 0.001 when comparing across all groups.

We analyzed whether known risk factors or possible confounders other than CMV viremia were contributing to 18-week mortality (Table 2). In our univariate analyses, CD4+ T-cell count per 10 cells/μl increase (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.96–1.01; P = 0.15) was not significantly associated with mortality, but GCS score <15 was associated (HR 1.58; 95% CI 1.12–2.21; P = 0.008). After adjusting for age, sex, CD4+ T-cell count, and GCS score <15 in our primary multivariate model (N = 340), we found that both the categorical presence of CMV viremia (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.60; 95% CI 1.13–2.25; P = 0.008) and greater CMV viral load (aHR 1.22 per one log10 IU/ml increase; 95% CI 1.09–1.35; P <0.001) remained significantly associated with 18-week mortality (Table 2). In our secondary adjusted model (N = 279), which considered numerous additional covariates, results were similar (Supplementary Table 3b).

We conducted separate subgroup analyses of mortality risk for persons with cryptococcal meningitis and TB meningitis. Baseline characteristics by meningitis subgroup are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Of the 308 persons with cryptococcal meningitis, 55 died in the group with CMV viremia (50%) vs. 73 in the group without viremia (37%) (P = 0.03). In the 32 persons with TB meningitis, six died in the group with CMV viremia (60%) versus one in the group without viremia (5%) (P = 0.001). The categorical presence of CMV viremia was significantly associated with 18-week mortality for patients with cryptococcal meningitis (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.04–2.09; P = 0.03) and for patients with TB meningitis (HR 17.1; 95% CI 2.04–142.6; P = 0.009) (Table 2). Similarly, using CMV log10 IU/ml as a continuous variable in our survival model, we found significant mortality associations for cryptococcal meningitis (HR 1.19; 95% CI 1.07–1.33; P = 0.002) and for TB meningitis (HR 2.59; 95% CI 1.45–4.63; P = 0.002). The primary adjusted model set (N = 340) remained significant for all CMV variables by subgroup (Table 2). The secondary full covariate model set (N = 279) resulted in an invalid analysis for TB meningitis because of case exclusions; for cryptococcal meningitis, CMV log10 IU/ml remained statistically significant (P = 0.02), but the categorical presence of CMV did not (P = 0.11) (Supplementary Table 2b).

Lastly, we investigated whether baseline ART status affected either probability of having CMV viremia or survival outcome. Detectable CMV viremia occurred in 37% (57/155) of those receiving ART at baseline compared with 35% (64/185) of those not receiving ART at baseline. Among the 154 with known timing of ART initiation, 45 had initiated ART within 30 days, and 47% (21/45) of those had CMV viremia. Of the 109 participants who had been on ART for >30 days, 32% (35/109) had CMV viremia (P = 0.09). The trend for increased mortality with CMV viremia was consistent in participants who were ART-naïve (52% vs. 38%; P = 0.08) and those who were ART-experienced (49% vs. 29%; P = 0.015) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Contingency tables for antiretroviral exposure at baseline by CMV viremia status

| (a) ART-naïve | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Dead by 18 weeks | Alive at 18 weeks | |

|

| ||

| CMV viremia present | 33 | 31 |

| CMV viremia absent | 46 | 75 |

| (b) ART-experienced | ||

|

| ||

| Dead by 18 weeks | Alive at 18 weeks | |

|

| ||

| CMV viremia present | 28 | 29 |

| CMV viremia absent | 28 | 70 |

Mortality by 18 weeks was 52% in ART-naïve participants with CMV viremia and 38% in ART-naïve participants without CMV viremia (P = 0.08).

Mortality by 18 weeks was 49% in ART-experienced participants with CMV viremia and 29% in ART-experienced participants without CMV viremia (P = 0.01).

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Discussion

We demonstrate that CMV viremia is associated with increased all-cause mortality among persons with HIV-associated cryptococcal and TB meningitis. Compared with our previous study (Skipper et al., 2020), we expanded our cohort to include both ART-experienced persons and those with TB meningitis. Any detectable CMV viremia was associated with a ∼60% greater risk of death at 18 weeks compared with the absence of viremia in our expanded cohort of HIV-associated meningitis. We found that the magnitude of viremia was positively associated with mortality when CMV DNA concentration was either log10 transformed as a continuous variable in our survival model or categorically grouped by clinical cutoffs. Further, CMV viremia remained significantly associated with mortality after adjustment for age, sex, CD4+ T-cell count, and baseline GCS score. Taken as a whole, mounting evidence suggests that CMV viremia poses a notable risk for increased mortality in persons with HIV-associated meningitis, and again raises the question of cause versus effect: is CMV a bystander signaling worsened immune function, or is CMV replication itself driving mortality in part? We continue to hypothesize as one plausible mechanism that ongoing viral replication in persistent infection produces type I interferons, which may suppress effective type-1 T helper CD4+ responses necessary to clear intracellular pathogens such as Cryptococcus and M. tuberculosis (Osokine et al., 2014). The second mechanism of interest involves the observed downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II proteins during CMV reactivation, whereby CD4+ T-cell function is impaired (Chevalier et al., 2002; Jenkins et al., 2008). We are currently designing experiments to test these hypotheses.

An important new observation in this study is the association of the magnitude of CMV viremia (i.e., greater baseline viral load) with higher mortality. We found that 18-week mortality exceeded 50% in participants with CMV DNA concentrations >1000 IU/ml and increased to 71% in those with concentrations >5000 IU/ml. Similarly, every log10 increase in CMV DNA IU/ml increased mortality ∼1.2-fold. These data suggests that persons with high viral loads may benefit from anti-CMV treatment, and that reduction of viral load below a critical level may ameliorate mortality risk. Our previous study (Skipper et al., 2020) failed to find a “dose-response” relationship between CMV magnitude and mortality, but this may have been a consequence of the smaller sample size and fewer cases with viral loads >1000 IU/ml. Importantly, the association between the magnitude of CMV viremia and mortality held true across all adjusted models we tested.

When we analyzed 18-week mortality by meningitis subgroup, we found that the presence of CMV viremia was associated with mortality (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.04–2.09) in persons with cryptococcal meningitis, but to a lesser degree than in our previous cohort (HR 2.19; 95% CI 1.07–4.49). After adjustment, the association remained significant in our primary multivariate model set (N = 340; HR 1.43; 95% CI 1.00–2.04) but lost statistical significance in the secondary full covariate model set (N = 279; HR 1.38 95% CI 0.93–2.04). We believe the smaller sample size in the secondary model set reduced the power of this model to detect statistically significant differences, and we are reassured by the similar HRs. However, we acknowledge that the relationship between CMV and mortality in persons with advanced HIV disease is likely complex and may be confounded by complicated interactions or factors not included in our models, obfuscating the precise risk that the presence of CMV viremia alone imparts on mortality. An alternative interpretation of our data could be that higher CMV viral load is associated with increased mortality in persons with cryptococcal meningitis, while lower viral load may not be associated with increased risk.

The large HR (17-fold) seen with detectable CMV viremia in persons with TB meningitis is striking but should be interpreted with caution, given the relatively small sample size and wide 95% CI. Nevertheless, given previously published studies demonstrating CMV as a potential risk factor for non-central nervous system TB, along with the biological plausibility of CMV-mediated impairment of the type 1 helper T cell response critical to controlling TB, it remains an intriguing finding worthy of additional study (Engstrand et al., 2003; Essa et al., 2009).

Another interesting observation is that CMV viremia was associated with lower hemoglobin values and reduced white blood cell response in the CSF. In in vitro models, CMV can infect bone marrow progenitor cells and disrupt hematopoiesis (Sing and Ruscetti, 1990). Anemia and leukopenia are known clinical complications of CMV disease. Less is known about how CMV affects white blood cell response in the CSF. It is possible that CMV is implicated in a multifactorial process affecting both the quality of the host’s immune response and the quantity of critical blood cellular components. Although CMV viremia may be associated with lower hemoglobin and reduced CSF white blood cell response, neither variable alone appears to significantly impact mortality (Supplementary Table 3a). We advocate for the inclusion of these variables in future CMV studies to further disentangle these complex interactions.

One key difference in the present cryptococcal meningitis cohort is that 45% of participants were ART-experienced at baseline (persisting with the advanced disease by either a failing ART regimen or having only recently initiated ART after their HIV diagnosis), whereas our previous cryptococcal meningitis cohort was entirely ART-naïve at baseline, with half of the participants initiating ART within 1–2 weeks after meningitis diagnosis (Boulware et al., 2014a; Skipper et al., 2020). It is unknown how ART exposure affects CMV viremia in persons who remain significantly CD4+ T-cell-deficient. Our analysis demonstrates similar rates of detectable CMV in ART-experienced and ART-naïve participants, and those that had begun ART recently (i.e., effective HIV treatment) appeared to have a similar frequency of viremia (47%) compared with those who had been on ART for a longer period (i.e., likely failing regimen) (32%). Similarly, as one might expect, CD4+ T-cell counts were not notably higher in persons without CMV viremia. Interestingly, we noted mildly worse survival in ART-experienced persons with CMV viremia compared with ART-naïve persons with CMV viremia in our post hoc analysis, invoking a possible detrimental immunologic contribution associated with previous ART exposure. CMV-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) has been described in the literature, particularly relative to ocular involvement, but is rarely identified in our study setting (Levi et al., 2022; Müller et al., 2010). We are currently planning a study to prospectively measure CMV DNA longitudinally over time and perform serial retinal exams—including after ART initiation or switch in failing patients—to provide better insight into the impact of early ART on CMV viremia. However, we do continue to advocate that effective ART remains critical to mitigate morbidity and mortality from CMV disease and advanced HIV.

Ultimately, the most impactful question is whether CMV is a modifiable risk factor in this population. CMV disease is associated with graft loss and increased mortality in solid organ transplant recipients (Hakimi et al., 2017; McBride et al., 2019), and treatment with anti-CMV therapy has been demonstrated to mitigate these poor outcomes (Asberg et al., 2007; Dunn et al., 1991). Transplant recipients also benefit from strategies of prophylaxis or preemptive therapy (initiating treatment based on a CMV DNA threshold) before the development of CMV disease (Owers et al., 2013; Witzke et al., 2018). Observations of the benefits of prophylactic or preemptive anti-CMV therapy in the transplant population raise the question of whether similar benefits could be demonstrated in the advanced HIV population. Essentially all persons with HIV-associated meningitis in Sub-Saharan Africa are CMV-seropositive and thus at risk for CMV reactivation (Skipper et al., 2020). Given the high mortality rate of HIV-associated meningitis (40% [135/340] in this study), addressing any modifiable risk factor may yield a real survival benefit. A randomized clinical trial to test anti-CMV therapy in persons with HIV-associated meningitis will help determine if CMV is indeed a modifiable risk factor in a subpopulation with advanced HIV disease.

Our study is limited as a post hoc analysis of participants enrolled in prospective randomized trials. Importantly, however, randomization to intervention was not different between persons with and without CMV viremia. Additionally, our proportional hazards model did not find a mortality association by intervention arm, similar to the parent trial findings (Cresswell et al., 2021; Rhein et al., 2019). We do not have CMV antibody data on this current cohort. However, our previous study demonstrated that all 111 persons with cryptococcal meningitis were anti-CMV IgG positive (Skipper et al., 2020). CMV seropositivity may be different in other regions of the world, impacting the generalizability of this study. CMV viremia was determined only at baseline, and the dynamics of the viremia over time would be an area for future exploration. Despite the fact that CMV DNA concentrations were measured using the same laboratory and instruments as previously, interassay variability may occur at the lower limit of detection. The clinical relevance of low-level CMV viremia in the setting of HIV-associated meningitis remains unclear. We limited the primary multivariate model to CD4+ T-cell count and GCS score (in addition to age and sex) to balance what we believed to be the most influential potential confounders while maintaining our full sample size. For transparency and to improve data interpretability, we have included a secondary supplemental model that adjusts for a full array of covariates, with the recognition that 61 participants are excluded because of missing data. Unfortunately, we do not have consistent HIV viral load information from our study cohorts; this would be valuable information to include in a future multivariate model. CMV appears as a particularly strong risk in TB meningitis, influencing the overall model. However, the small sample size and wide CIs suggest that the HR could change with a larger study population. We also note that these findings apply only to HIV-associated cryptococcal and TB meningitis, preventing the generalization of the findings to persons with either HIV-associated meningitis of a different etiology or HIV-negative meningitis. Lastly, this study did not systematically investigate for CMV end-organ disease, limiting the ability to determine how primary CMV disease might contribute to all-cause mortality.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that detectable CMV viremia is associated with ∼60% greater risk of death in persons with HIV-associated cryptococcal or TB meningitis. The mechanisms driving the increased risk of death are unclear; however, the positive association between the magnitude of CMV viral load and mortality suggests that a greater CMV burden is detrimental, perhaps through CMV-specific modulation of the immune system. Alternatively, CMV reactivation may simply reflect an immune state less well-equipped to handle the primary opportunistic infection, thus serving as a marker of heightened immune dysfunction. A randomized clinical trial is needed to determine whether preventing or treating CMV viremia in persons with HIV-associated meningitis can reduce mortality and improve survival in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative of the study teams and hospital staff working continuously to provide compassionate care to the participants and patients at Mulago National Referral Hospital.

Funding

This research was made possible by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR002492 and UL1TR002494); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32AI055433, U01AI089244); Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD079918); National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (R01NS086312); and the Fogarty International Center (K01TW010268, D43TW009345). FVC is supported by a Well-come Ph.D. Fellowship (210772/Z/18/Z).

DBM and DRB contributed equally to this work.

Appendix

ASTRO-CM Study team:

Joshua Rhein, Kathy Huppler Hullsiek, Lillian Tugume, Edwin Nuwagira, Edward Mpoza, Emily E Evans, Reuben Kiggundu, Katelyn A Pastick, Kenneth Ssebambulidde, Andrew Akampurira, Darlisha A Williams, Ananta S Bangdiwala, Mahsa Abassi, Abdu K Musubire, Melanie R Nicol, Conrad Muzoora, David B Meya, David R Boulware, Jane Francis Ndyetukira, Cynthia Ahimbisibwe, Florence Kugonza, Carolyne Namuju, Alisat Sadiq, Alice Namudde, James Mwesigye, Kiiza K Tadeo, Paul Kirumira, Michael Okirwoth, Tonny Luggya, Julian Kaboggoza, Eva Laker, Leo Atwine, Davis Muganzi, Stewart Walukaga, Bilal Jawed, Matthew Merry, Anna Stadelman, Nicole Stephens, Andrew G Flynn, Ayako W Fujita, Richard Kwizera, Liliane Mukaremera, Sarah M Lofgren, Fiona V Cresswell, Bozena M Morawski, Nathan C Bahr, Kirsten Nielsen.

RIFT Study team:

Jane Frances, Florence Kigundu, Cythia Ahimbisibwe, Carol Karuganda, Alice Namudde, Kiiza Tadeo Kandole, Alisat Sadiq, Mable Kabahubya, Edward Mpoza, Gavin Stead, Samuel Jjunju, Edwin Nuwagira, Nathan Bahr, Joshua Rhein, Darlisha Williams, Rhona Muyise, Eva Laker.

Footnotes

Declarations of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2022.07.035.

References

- Asberg A, Humar A, Rollag H, Jardine AG, Mouas H, Pescovitz MD, et al. Oral valganciclovir is noninferior to intravenous ganciclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2007;7:2106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware DR, Meya DB, Muzoora C, Rolfes MA, Huppler Hullsiek K, Musubire A, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med 2014a;370:2487–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware DR, Rolfes MA, Rajasingham R, von Hohenberg M, Qin Z, Taseera K, et al. Multisite validation of cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay and quantification by laser thermal contrast. Emerg Infect Dis 2014b;20:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantsæter AB, Johannessen A, Holberg-Petersen M, Sandvik L, Naman E, Kivuyo SL, et al. Cytomegalovirus viremia in dried blood spots is associated with an increased risk of death in HIV-infected patients: a cohort study from rural Tanzania. Int J Infect Dis 2012;16:e879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler EK, Boulware DR, Bohjanen PR, Meya DB. Long term 5-year survival of persons with cryptococcal meningitis or asymptomatic subclinical antigenemia in Uganda. PLoS One 2012;7:e51291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier MS, Daniels GM, Johnson DC. Binding of human cytomegalovirus US2 to major histocompatibility complex class I and II proteins is not sufficient for their degradation. J Virol 2002;76:8265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi R, Lee S, Lee SG, Lee EH. Seroprevalence of CMV IgG and IgM in Korean women of childbearing age. J Clin Lab Anal 2021;35:e23716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston LI, Li C, Sarkodie F, Owusu-Ofori S, Opare-Sem O, Allain JP. Prevalence of persistent and latent viruses in untreated patients infected with HIV-1 from Ghana, West Africa. J Med Virol 2009;81:1860–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell FV, Meya DB, Kagimu E, Grint D, Te Brake L, Kasibante J, et al. High– dose oral and intravenous rifampicin for the treatment of tuberculous meningitis in predominantly human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive Ugandan adults: a Phase II open-label randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:876–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Matos SB, Meyer R, de Mendonça Lima FW. Seroprevalence and serum profile of cytomegalovirus infection among patients with hematologic disorders in Bahia State, Brazil. J Med Virol 2011;83:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deayton JR, Prof Sabin CA, Johnson MA, Emery VC, Wilson P, Griffiths PD. Importance of cytomegalovirus viraemia in risk of disease progression and death in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet 2004;363:2116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollard SC, Dreon M, Hernandez-Alvarado N, Amin MM, Wong P, Lanzieri TM, Osterholm EA, Sidebottom A, Rosendahl S, McCann MT, Schleiss MR. Sensitivity of dried blood spot testing for detection of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175 e205441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DL, Mayoral JL, Gillingham KJ, Loeffler CM, Brayman KL, Kramer MA, et al. Treatment of invasive cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant patients with ganciclovir. Transplantation 1991;51:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durier N, Ananworanich J, Apornpong T, Ubolyam S, Kerr SJ, Mahanontharit A, et al. Cytomegalovirus viremia in Thai HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy: prevalence and associated mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J, Bangdiwala AS, Cresswell FV, Rhein J, Nuwagira E, Kenneth Ssebambulidde K, et al. The changing epidemiology of HIV-associated adult meningitis, Uganda 2015–2017. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrand M, Lidehall AK, Totterman TH, Herrman B, Eriksson BM, Korsgren O. Cellular responses to cytomegalovirus in immunosuppressed patients: circulating CD8+ T cells recognizing CMVpp65 are present but display functional impairment. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;132:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essa S, Pacsa A, Raghupathy R, Said T, Nampoory MRN, Johny KV, et al. Low levels of Th1-type cytokines and increased levels of Th2-type cytokines in kidney transplant recipients with active cytomegalovirus infection. Transplant Proc 2009;41:1643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding K, Koba A, Grant AD, Charalambous S, Day J, Spak C, et al. Cytomegalovirus viremia as a risk factor for mortality prior to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected gold miners in South Africa. PLoS One 2011;6:e25571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianella S, Letendre S. Cytomegalovirus and HIV: a Dangerous pas de deux. J Infect Dis 2016;214:S67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønborg HL, Jespersen S, Hønge BL, Jensen-Fangel S, Wejse C. Review of cytomegalovirus coinfection in HIV-infected individuals in Africa. Rev Med Virol 2017;27:e1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi Z, Aballéa S, Ferchichi S, Scharn M, Odeyemi IA, Toumi M, et al. Burden of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients: a national matched cohort study in an inpatient setting. Transpl Infect Dis 2017;19:e12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakyemez IN, Erdem H, Beraud G, Lurdes M, Silva-Pinto A, Alexandru C, et al. Prediction of unfavorable outcomes in cryptococcal meningitis: results of the multicenter Infectious Diseases International Research Initiative (ID-IRI) cryptococcal meningitis study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37:1231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbari MR, Soleimanjahi H, Shatizadeh Malekshahi S, Gholami M, Sadeghi L, Mohraz M. Frequency of cytomegalovirus viral load in Iranian human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients with CD4+ counts <100 cells/mm3. Intervirology 2021;64:135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Garcia W, Godwin MJ, Spencer JV, Stern JL, Abendroth A, et al. Immunomodulatory properties of a viral homolog of human interleukin-10 expressed by human cytomegalovirus during the latent phase of infection. J Virol 2008;82:3736–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi LI, Sharma S, Schleiss MR, Furrer H, Nixon DE, Blackstad M, et al. Cytomegalovirus viremia and risk of disease progression and death in HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2022;36:1265–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim RB, Tan MT, Young B, Lee CC, Leo YS, Chua A, et al. Risk factors and time-trends of cytomegalovirus (CMV), syphilis, toxoplasmosis and viral hepatitis infection and seroprevalence in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients. Ann Acad Med Singap 2013;42:667–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren S, Hullsiek KH, Morawski BM, Nabeta HW, Kiggundu R, Taseera K, et al. Differences in immunologic factors among patients presenting with altered mental status during cryptococcal meningitis. J Infect Dis 2017;215:693–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride JM, Sheinson D, Jiang J, Lewin-Koh N, Werner BG, Chow JKL, et al. Correlation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease severity and mortality with CMV viral burden in CMV-seropositive donor and CMV-seronegative solid organ transplant recipients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micol R, Buchy P, Guerrier G, Duong V, Ferradini L, Dousset JP, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on outcome of cytomegalovirus replication in serum of Cambodian HIV-infected patients (2004–2007). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;51:486–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CC, Jacob ST, Banura P, Zhang J, Stroup S, Boulware DR, et al. Etiology of sepsis in Uganda using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction-based TaqMan array card. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68:266–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M, Southern IeDEA, Africa Central. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osokine I, Snell LM, Cunningham CR, Yamada DH, Wilson EB, Elsaesser HJ, de la Torre JC, Brooks D. Type I interferon suppresses de novo virus-specific CD4 Th1 immunity during an established persistent viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:7409–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owers DS, Webster AC, Strippoli GFM, Kable K, Hodson EM. Pre-emptive treatment for cytomegalovirus viraemia to prevent cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2013 CD005133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, Chiller TM, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:873–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhein J, Huppler Hullsiek K, Tugume L, Nuwagira E, Mpoza E, Evans EE, et al. Adjunctive sertraline for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:843–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sing GK, Ruscetti FW. Preferential suppression of myelopoiesis in normal human bone marrow cells after in vitro challenge with human cytomegalovirus. Blood 1990;75:1965–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper C, Schleiss MR, Bangdiwala AS, Hernandez-Alvarado N, Taseera K, Nabeta HW, et al. Cytomegalovirus viremia associated with increased mortality in cryptococcal meningitis in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:525–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza MA, Passos AM, Treitinger A, Spada C. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus antibodies in blood donors in southern. Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2010;43:359–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector SA, Wong R, Hsia K, Pilcher M, Stempien MJ. Plasma cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA load predicts CMV disease and survival in AIDS patients. J Clin Invest 1998;101:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer KL, Weinberg A. Cytomegalovirus infection in the era of HAART: fewer reactivations and more immunity. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004;54:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale L, Nash S, Farmer R, Raynes J, Mallikaarjun S, Newton R, et al. Cytomegalovirus antibody responses associated with increased risk of tuberculosis disease in Ugandan adults. J Infect Dis 2020;221:1127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde MW, Gertz AM, Lawrence DS, Wills NK, Guthrie BL, Farquhar C, Jarvis JN. Mortality from HIV-associated meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23:e25416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugume L, Rhein J, Hullsiek KH, Mpoza E, Kiggundu R, Ssebambulidde K, et al. HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis occurring at relatively higher CD4 counts. J Infect Dis 2019;219:877–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuon FF, Wollmann LC, Pegoraro D, Gouveia AM, Andrejow AP, Schultz AT, et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii, Cytomegalovirus and Epstein Barr virus in 578 tissue donors in Brazil. J Infect Public Health 2019;12:289–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang T, Zhang W, Liu X, Wang X, Wang H, et al. Cohort study on maternal cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and prevalence and clinical manifestations of congenital infection in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Barr B, Schutz C, Burton R, Boulle A, Maartens G, et al. Cytomegalovirus viraemia and 12-week mortality among hospitalized adults with HIV-associated tuberculosis in Khayelitsha Hospital, South Africa: a prospective cohort study. Oral abstracts of the 21st International AIDS Conference 18–22 July 2016, Durban, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc 2016;19:21264.27460772 [Google Scholar]

- Witzke O, Nitschke M, Bartels M, Wolters H, Wolf G, Reinke P, et al. Valganciclovir prophylaxis versus preemptive therapy in cytomegalovirus-positive renal allograft recipients: long-term results after 7 years of a randomized clinical trial. Transplantation 2018;102:876–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls. 1st WHO International Standard for Human Cytomegalovirus for Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques NIBSC code: 09/162 2014;Version 6.0 Accessed on 4/30/22.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.