Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare the benefit of self-adjusted personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) to audiologist-fitted hearing aids based on speech recognition, listening effort, and sound quality in ecologically relevant test conditions to estimate real-world effectiveness.

Method

Twenty-five older adults with bilateral mild-to-moderate hearing loss completed the single-blinded, crossover study. Participants underwent aided testing using 3 PSAPs and a traditional hearing aid, as well as unaided testing. PSAPs were adjusted based on participant preference, whereas the hearing aid was configured using best-practice verification protocols. Audibility provided by the devices was quantified using the Speech Intelligibility Index (American National Standards Institute, 2012). Outcome measures assessing speech recognition, listening effort, and sound quality were administered in ecologically relevant laboratory conditions designed to represent real-world speech listening situations.

Results

All devices significantly improved Speech Intelligibility Index compared to unaided listening, with the hearing aid providing more audibility than all PSAPs. Results further revealed that, in general, the hearing aid improved speech recognition performance and reduced listening effort significantly more than all PSAPs. Few differences in sound quality were observed between devices. All PSAPs improved speech recognition and listening effort compared to unaided testing.

Conclusions

Hearing aids fitted using best-practice verification protocols were capable of providing more aided audibility, better speech recognition performance, and lower listening effort compared to the PSAPs tested in the current study. Differences in sound quality between the devices were minimal. However, because all PSAPs tested in the study significantly improved participants' speech recognition performance and reduced listening effort compared to unaided listening, PSAPs could serve as a budget-friendly option for those who cannot afford traditional amplification.

Hearing loss affects more than 37 million adults in America (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2016). According to a survey of American adults, only about 30% of those with hearing difficulties own hearing aids (Abrams & Kihm, 2015), though treatments such as amplification have been shown to reduce negative consequences of living with untreated hearing loss (Hougaard, Ruf, Egger, & Abrams, 2016; Mulrow et al., 1990). One primary reason for the low uptake of hearing aids is their high cost (Abrams & Kihm, 2015; Kochkin, 2007). The average pair of hearing aids costs approximately $4,700 (President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2015), which can impose a financial burden on many individuals who might benefit from amplification and is the reason many adults live with untreated hearing loss. The increasing cost of traditional hearing health care services has created a market opportunity for many nonregulated, yet more affordable, devices, commonly called personal sound amplification products (PSAPs).

At the time this project was developed, a PSAP was defined as a device “intended to amplify environmental sound for non–hearing-impaired consumers” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2013). This specific category of amplification is separate from traditional hearing aids, as PSAPs are not meant to be used to compensate for hearing loss and are therefore not regulated as a medical device by the Food and Drug Administration. Because PSAPs are intended to be sold directly to consumers, they can be considered a type of over-the-counter (OTC) amplification device. Because of their significantly lower cost, PSAPs find their place among consumers who report some difficulty in hearing but are not yet willing to spend thousands of dollars on audiologist-fitted hearing aids. PSAPs typically look like traditional hearing aids, both behind-the-ear and in-the-ear styles, whereas some resemble ear-level Bluetooth devices. PSAPs cost between $25 and $500 (President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2015).

Although PSAPs are not meant for those with hearing loss, it was found that 1.5 million people with hearing impairments use either a PSAP or OTC device to compensate for their communication difficulties (Kochkin, 2010). Among a group of surveyed Americans who reported hearing difficulties, 9.4% reported owning a PSAP (Abrams & Kihm, 2015). Kochkin (2010) found that approximately 72% of those who reportedly used PSAPs had hearing loss configurations similar to those of patients who used audiologist-fitted hearing aids. Overall, the demography of those who purchased PSAPs was similar to those who purchased audiologist-fitted hearing aids in terms of age, employment, and education (Kochkin, 2010). A few significant differences between the groups were observed by Kochkin (2010). Specifically, PSAP users earned, on average, $10,000 less per year than those using audiologist-fitted hearing aids and were less likely to pursue bilateral amplification. In addition, PSAP users, on average, wore their devices for only 3 hr a day compared to the average 10 hr of use per day reported by hearing aid owners. Lastly, male individuals were reportedly more likely to purchase PSAPs compared to female individuals, whereas in the audiologist-fitted hearing aid market, the gender breakdown was more equal.

Earlier studies have reported that many OTC devices provided unsuitable levels of low-frequency gain with insufficient high-frequency gain (Callaway & Punch, 2008; Chan & McPherson, 2015; Cheng & McPherson, 2000; Reed, Betz, Lin, & Mamo, 2017; Smith, Wilber, & Cavitt, 2016). For example, Chan and McPherson (2015) reported that the majority of the evaluated OTC devices in their study demonstrated linear input–output characteristics, peak clipping, high levels of equivalent input noise, and little usable high-frequency gain. Research further indicated that many PSAPs or OTC devices had gain frequency responses that were most appropriate for rising hearing losses due to a greater low-frequency emphasis (Chan & McPherson, 2015; Cheng & McPherson, 2000). However, recent research suggested that modern PSAPs could be an appropriate solution for those with mild-to-moderate hearing loss. For example, Smith et al. (2016) examined the ability of PSAPs to match prescriptive targets for 10 hypothetical audiograms of varying severity and found that certain higher-end PSAPs could be appropriately fit to an individual with up to a moderate degree of hearing loss. Reed, Betz, Lin, et al. (2017) found that several high-end PSAPs tested had electroacoustic characteristics within the tolerances used to assess hearing aid function for frequency range, equivalent input noise, maximum output, and total harmonic distortion measures.

Previous research has also investigated the effect of PSAPs on patient outcomes in the laboratory. For example, Xu, Johnson, Cox, and Breitbart (2015) compared the perceived sound quality of PSAPs relative to hearing aids. Results showed a significant preference for hearing aids over PSAPs only when listening to quiet conversation. No differences in sound quality were observed between any devices for everyday noises or music listening. More recently, Reed, Betz, Kendig, Korczak, and Lin (2017) compared five PSAPs with a traditional hearing aid. Results in speech recognition performance in noise indicated that three of the five PSAPs performed within 5 percentage points of the hearing aid.

Research investigating the real-world benefit of PSAPs and OTC devices is limited. Humes et al. (2017) compared a direct-to-consumer service delivery model, which could be used to dispense OTC devices to an audiologist-based hearing aid service delivery model. The direct-to-consumer delivery model was shown to be efficacious, yielding outcomes similar to the traditional audiologist-based model. However, high-end hearing aids, rather than PSAPs or OTC devices, were used by Humes et al. Recently, Acosta, Hines, and Johnson (2018) conducted a double-blinded randomized control field trial to evaluate the effect of self-fitted OTC devices relative to audiologist-fitted hearing aids. Outcomes in speech communication and sound aversiveness were measured 1 week posttrial using the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (Cox & Alexander, 1995). Results indicated that, although the mean benefit score in speech communication of OTC devices was higher (better) than that of hearing aids (Cohen's d = 0.54), hearing aids had a higher (better) benefit score in aversiveness than OTC devices (Cohen's d = 0.78). However, likely due to the small sample size of the trial (total n = 17), none of the effects were statistically significant.

Not only is the effect of PSAPs and OTC devices in the real world unclear (for the reasons mentioned above), there are also gaps in the literature regarding the benefit of these devices relative to traditional hearing aids in well-controlled laboratory environments. For example, in the study by Xu et al. (2015) that compared the sound quality of PSAPs and hearing aids, stimuli were prerecorded by placing the devices on a manikin's ear. Furthermore, the hearing aids used to record stimuli were not configured to compensate for each participant's hearing loss. Therefore, it is unclear if the results of Xu et al. (2015) could generalize to PSAPs and hearing aids used in the real world. In the study by Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017), speech recognition testing was conducted with research participants wearing the PSAPs adjusted using best-practice verification protocols by an audiologist, rather than by the participants themselves. The unrealistic PSAP fitting scheme used by Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017) could limit the generalizability of the study. Specifically, two PSAPs used by Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017) had smartphone application software (app) that allowed users to fine-tune the gain frequency response of the device. Previous research has shown that audiologist-driven hearing aid fine-tuning yielded better outcomes than patient-driven fine-tuning (Boymans & Dreschler, 2012). Thus, it is unclear if the PSAPs would still yield similar outcomes compared to audiologist-fitted hearing aids if the PSAPs were configured by the users. Furthermore, Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017) did not specify if the device's volume control was available to participants during testing. Hence, it is also unclear how users would select the volume levels for PSAPs and how this would affect differences in outcomes between PSAPs and traditional hearing aids.

To fill gaps in the literature, the purpose of the current study was to examine the effect of PSAPs on speech recognition, listening effort, and sound quality compared to audiologist-fitted hearing aids using relatively realistic settings in the laboratory. Specifically, participants were responsible for selecting their preferred settings in an effort to simulate the real-world self-fitting process of many PSAPs on the market. In addition, outcome measures in the current study were administered using test conditions that represent real-world listening situations (i.e., ecologically relevant). It is well established that the effect of certain hearing aid features, such as directional microphones, highly depends on the characteristics of listening situations (e.g., the locations of speech and noise) (Ricketts, 2000). Because directional microphones are available in many modern PSAPs, outcomes measured in ecologically relevant conditions could be more generalizable to the real world.

Method

Participants

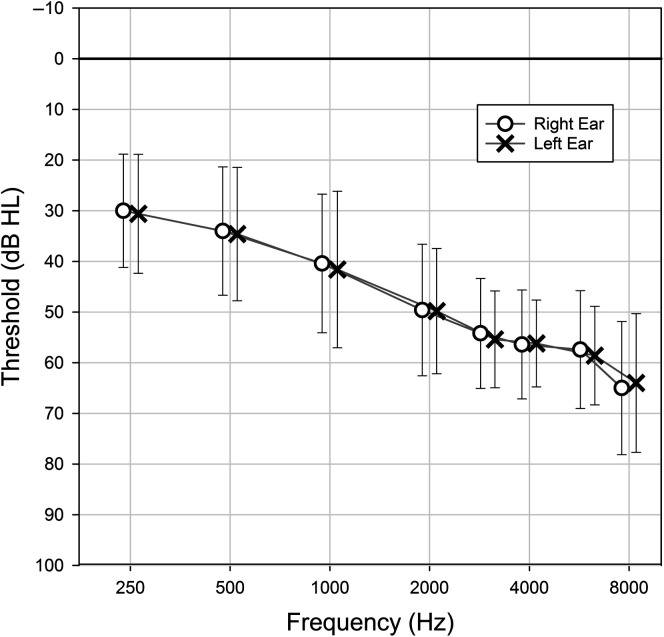

Twenty-five adults (12 men and 13 women) were recruited from the community and completed the study. Participants were eligible for inclusion in the study based on the following criteria: (a) bilateral mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss, (b) a maximum threshold of 75 dB HL up to 4000 Hz, (c) hearing threshold symmetry within 15 dB up to 4000 Hz, and (d) the ability to understand the directions of the experiment and perform experiment-related tasks. The mean pure-tone thresholds are shown in Figure 1. Participants ranged in age from 56 to 81 years, with a mean of 69.6 years (SD = 8.2). All but one participant were experienced hearing aid users, with the mean years of use being 8.4 years (SD = 9.7).

Figure 1.

Mean hearing thresholds for the participants. Right and left ears are offset from one another. Error bars indicate 1 SD.

Amplification Devices and Fitting

A traditional hearing aid and three PSAPs were used in the current study. The traditional hearing aid was a ReSound LiNX2 5, denoted as the HA. The HA was a midlevel, behind-the-ear, receiver-in-the-canal device equipped with wide dynamic range compression (nine channels), adaptive directional microphones, digital noise reduction algorithms, and a smartphone app for volume adjustment. The three PSAPs used were a Sound World Solutions CS50+, a FocusEar RS2, and a Tweak Focus, denoted as PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3, respectively. The PSAPs were all behind-the-ear slim-tube style. The prices of PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3 were $349, $399, and $299 (per device), respectively. The PSAPs were chosen to represent midlevel to high-end PSAPs. All PSAPs had directional microphones and noise reduction features. PSAP1 had a corresponding smartphone app that allows users to adjust the device's volume and frequency response. Users could also use the three-channel equalizer feature (bass, mid, and treble) of the app to adjust the shape of the frequency response of PSAP1.

All devices were fitted bilaterally. The HA was fitted by an audiologist using real-ear measurements matched to National Acoustics Laboratory (NAL-NL2; Keidser, Dillon, Flax, Ching, & Brewer, 2011) nonlinear prescriptive targets for an average-level speech input (65 dB SPL) using a clinically appropriate dome. Two user programs were configured: the first program (denoted as P1) was for quiet situations (omnidirectional microphone with noise reduction turned off), and the second program (P2) was for noisy situations (adaptive directional microphone with digital noise reduction enabled). The frequency responses of the two programs were equalized. The features in P2 were set to the default as suggested by the manufacturer. The device's frequency response was not further fine-tuned based on user's feedback.

The PSAPs were fitted using the default earpiece recommended by the manufacturers (PSAP1 and PSAP2: closed dome; PSAP3: power dome). PSAP1 had three predetermined frequency responses (described as presets), so participants were given the opportunity to select and fine-tune the preset (see below for the procedure). PSAP2 and PSAP3 had only one predetermined frequency response that could not be altered by the end user. All PSAPs had multiple user programs preconfigured by the manufacturers, which could not be disabled. For all PSAPs, the default program (P1) was for listening in quiet environments and the second program (P2) was for noisy listening situations. In P2, directional microphones and noise reduction features were enabled. PSAP1 and PSAP2 had additional programs for “entertainment” and telephone use. These additional programs were not tested in the current study; only P1 and P2 were used in the experiment.

To better simulate user adjustments of hearing aids and PSAPs, participants individually selected their preferred volume levels in each program for each device. Because PSAP1 had three presets and its smartphone app had a three-channel equalizer feature, participants were allowed to select their preferred preset for each program and use the equalizer to fine-tune the frequency response in addition to adjusting the volume. To determine the volume level for all devices (and adjust the frequency response of PSAP1), participants were positioned in a sound field created using an eight-loudspeaker array in a sound-treated booth. Eight Tannoy Di5t loudspeakers (Tannoy) were located at 0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, and 315° azimuth relative to the participant. The distance between the loudspeaker and the participant was 1 m. Continuous sentences from the Connected Speech Test (CST; Cox, Alexander, & Gilmore, 1987) were presented from 0° azimuth, and the CST babble noise was presented from all eight loudspeakers. Speech and babble noise were presented at 60 and 40 dBA, respectively, for adjustments made in P1 and at 68 and 61 dBA, respectively, for adjustments in P2. These levels were selected to represent real-world listening situations (Wu et al., 2018). A Larson Davis 2560 0.5-in. random incidence microphone and a Larson Davis System 824 sound-level meter were used to calibrate the sound field (as well as the sound fields used in the outcome measures described below). The microphone was placed at the position of the listener's head. To calibrate the noise, the CST babble presented from each loudspeaker was first measured. The level and spectrum of each babble noise were adjusted to be equal across the eight loudspeakers. The overall level of the babble noise (all loudspeakers presented at once) was then set to 40 dBA (for P1 adjustment) or 61 dBA (for P2).

Participants were instructed to adjust each device using the following instructions, “Imagine you are having a conversation and adjust the device so that you can best understand the speech while maintaining comfort.” Participants adjusted left and right devices individually and could take as much time as they needed. Adjustments were made by pushing buttons on the devices (PSAP2 and PSAP3) or using a smartphone app (HA and PSAP1). For PSAP1, preset selection and fine-tuning were conducted before adjusting volume levels. A researcher was available to assist participants (e.g., changing the preset of PSAP1) during device adjustments. Pairing the smartphone (a Samsung Galaxy S6) to the devices (HA and PSAP1) was completed by the researcher before the adjustment process. For all devices, individual participant-selected settings in each program were recorded and were used for all testing in the study.

To illustrate the electroacoustic characteristics of the devices, a series of Verifit 2 (Audioscan) test box measures were conducted. The HA was configured to fit the average hearing loss of the participants. All devices were set using the most commonly selected user settings (e.g., volume level and preset) across all participants in both programs. Figure 2 shows the input–output functions at 2000 Hz of P1 (A) and P2 (B) of each device. The figure indicates that the HA and PSAP1 utilized compression at various input levels whereas PSAP2 and PSAP3 demonstrated less compression. To quantify the device's directivity, a Verifit directivity measure (70 dB SPL with a +3 dB SNR) was conducted with the devices set in P2. The directivity averaged from 500 to 5000 Hz (American National Standards Institute, 2010) for the HA, PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3 was 8.4, 14.8, 9.7, and 9.5 dB, respectively. Finally, the Verifit test box noise reduction measure (multitalker babble noise stimulus at 70 dB SPL) showed that the average noise reduction from 500 to 5000 Hz for the HA, PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3 in P2 was 2.8, 2.9, 3.5, and 0.4 dB, respectively.

Figure 2.

Input–output functions at 2000 Hz measured for each device in P1 (A) and P2 (B). Devices were set to the most common selected settings, averaged across all 25 participants. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

Outcome Measures

Speech Intelligibility Index

The Speech Intelligibility Index (SII; American National Standards Institute, 2012) was used to quantify speech audibility. Following device fittings and adjustments, an SII was measured on-ear with a 65-dB SPL speech input using a probe microphone and the Verifit hearing aid analyzer in both P1 and P2 for all devices using the participant-selected settings. An unaided SII was also recorded for comparison purposes. In addition, a real-ear aided response (REAR) with an input of 65 dB SPL was recorded for each device in each program using the subject-selected settings.

Hearing in Noise Test

The Hearing in Noise Test (HINT; Nilsson, Soli, & Sullivan, 1994) was used to measure participants' speech recognition thresholds (SRTs) both in quiet and in noise. The HINT was administered in the same sound field used for device adjustment. To measure the SRT in quiet, the HINT sentences were presented from 0° azimuth without noise and the devices were set to P1. To measure the SRT in noise, additional uncorrelated HINT noise was presented using the eight-loudspeaker array. The overall level of the noise (all loudspeakers presented at once) was fixed at 65 dBA, and the devices were set to P2. Concatenated HINT sentences and the HINT speech-shaped noise were used to calibrate the sound field. In both test conditions (in quiet and in noise), the listener was asked to repeat a block of 20 HINT sentences (i.e., two lists). The speech level was adjusted adaptively, depending on the participant's responses, using the one-up-one-down procedure (4-dB steps for the first four sentences and 2-dB steps for the remaining sentences). The correct response regarding each sentence was based on the repetition of all the words in the sentence, with minor exceptions such as “a” and “the.” The presentation level (quiet condition) or signal-to-noise ratio (SNR; noise condition) of the final 17 presentations was averaged to derive the SRT. Both test conditions of the HINT were administered for each device as well as in an unaided condition.

Connected Speech Test

Estimated real-world speech recognition performance was assessed using the CST. The test is composed of 48 passages of conversational connected speech broken up into specific topics. Each passage contains nine to 10 sentences, and 25 target words are used for scoring. The CST was selected because passages could be presented with or without a visual component and using connected speech offered more ecological validity compared to single words or unrelated sentences. The CST was conducted in conditions designed to represent real-world listening situations. Specifically, Wu et al. (2018) examined the real-world listening environments of older adults with hearing loss and developed 12 “prototype listening situations” (PLSs). These PLSs describe the speech level, noise level, availability of visual cues, and locations of speech and noise sources of typical speech listening situations experienced by older adults with hearing loss. The PLSs could enable more ecologically valid assessment protocols in the laboratory to evaluate real-world outcomes (Walden, 1997; Wu et al., 2018).

In the current study, the six most frequent PLSs described in Wu et al. (2018) were created for the CST testing using the eight-loudspeaker sound field described above. Wu et al. (2018) indicated that these six test environments would represent 71% of daily speech listening situations. The six PLSs (denoted as PLS1 to PLS6) were broken down into two subgroups: quiet and noise. For the three quiet PLSs, speech and noise were presented at 60 and 40 dBA, respectively (20 dB SNR). For the noisy PLSs, speech and noise were presented at 68 and 61 dBA, respectively (7 dB SNR). Note that noise was used in the quiet PLSs because, in the real world, listening environments that are completely quiet are rare (Wu et al., 2018). Within each subgroup, there were three configurations: speech presented from 0° azimuth with visual cues present, speech presented from 90° azimuth with visual cues absent, and speech presented from 0° azimuth with visual cues absent. See Figure 3 for the characteristics of the PLSs. Visual cues (i.e., the talker's face) were presented on a 17-in. computer monitor, which was placed right below the loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. For all PLSs, uncorrelated CST babble was presented from each of the eight loudspeakers surrounding the listener, and the overall level (all loudspeakers presented at once) was set to 40 or 61 dBA, depending on the PLS. For each test condition, two CST passages (50 target words) were presented and scored. Performance was scored based on the percentage of target words repeated correctly in each condition. All devices were set to P1 for testing in quiet environments (PLS1, PLS2, PLS3) and P2 for testing in noisy environments (PLS4, PLS5, PLS6). The CST was also administered in an unaided condition.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the six prototype listening situations (PLS). Circles indicate the eight-loudspeaker array surrounding the participant (center). Black circles indicate location of the speech. Eye graphic indicates presence of visual cues. For PLS1 to PLS3, speech and noise were presented at 60 and 40 dBA, respectively. For PLS4 to PLS6, speech and noise were presented at 68 and 61 dBA, respectively.

Listening Effort Measure

Measures of speech recognition (e.g., the CST) are a useful way to quantify communication. However, research suggests that even when speech understanding scores under two conditions are similar, the level of listening effort might be different (Sarampalis, Kalluri, Edwards, & Hafter, 2009). To measure listening effort, the participants were asked to rate their perceived listening effort after listening and repeating CST sentences in each of the six PLSs. The participants answered the question “How hard were you working to achieve your level of speech understanding?” using a 21-point scale ranging from 0, representing not at all, to 100, representing very, very hard. This subjective listening effort measure, rather than objective measures such as dual-task paradigms, was selected because subjective measures of listening effort can be more sensitive than objective measures (Johnson, Xu, Cox, & Pendergraft, 2015; Seeman & Sims, 2015).

Sound Quality Rating

Subjective sound quality judgments were recorded as a separate metric to differentiate between devices. Reports of poor sound quality may be associated with hearing aid nonuse and dissatisfaction (Solheim, Gay, & Hickson, 2017). Perceived sound quality was measured in a manner similar to listening effort. Specifically, after listening and repeating CST sentences in a given condition, the participants answered the question “How would you judge the overall sound quality?” using a 21-point scale ranging from 0, representing very poor, to 100, representing excellent. Sound quality ratings were obtained in only the aided conditions.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Iowa. After consenting to the study protocol, participants' hearing thresholds were measured using pure-tone audiometry. If the participant met all required inclusion criteria, the devices were fitted and adjusted. Next, outcome measures were administered. For all testing, a practice condition was administered to confirm participants' understanding of the task. The order of device condition, PLS, HINT lists, and CST passage pairs were randomized across participants. The devices were inserted into the participant's ears by a researcher so that participants were blinded to the device. However, researchers were not blinded to the devices when scoring test materials (single-blinded design). Testing was completed in a series of two 2-hr sessions. Monetary compensation was provided to the participants upon completion of the study.

Results

REAR

Figure 4 shows the mean REAR (averaged across all 50 ears), measured using a 65-dB SPL speech input, of each device in P1 (A) and P2 (B) with the participant-selected settings. Mean REAR targets prescribed by NAL-NL2 averaged across participants are also shown in the figure. The REARs of the HA and PSAP1 are closest to the prescribed targets. In contrast, PSAP2 and PSAP3 underamplified speech sounds at frequencies above 2000 Hz. Root-mean-square deviations between the NAL-NL2 targets and each device at 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz were calculated and averaged across all 50 ears. Root-mean-square deviations for the HA, PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3 were 3.4, 4.9, 7.2, and 7.6 dB, respectively, in P1 and 3.6, 6.4, 6.9, and 10.0 dB, respectively, in P2.

Figure 4.

Mean real-ear aided response (REAR) as a function of frequency for the first (P1) (A) and second (P2) (B) user program of each device with participant-selected settings using a 65-dB SPL speech input. Mean National Acoustics Laboratories Nonlinear prescription procedures, 2nd generation (NAL-NL2) targets averaged across participants are plotted as single points. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

SII

Figure 5 shows the box plots of better ear SII of each device in P1 and P2 for all participants. To examine the effect of device on SII, a linear mixed model was used. The model included a random intercept for subject to account for the repeated observations per participant, with fixed effects being device condition (five levels: HA, three PSAPs, and unaided). The dependent variable was better ear SII. Separate analyses were conducted for P1 and P2 data. The results revealed that, for P1, device had a significant effect on SII, F(4, 96) = 66.1, p < .0001. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were further conducted, and a Tukey–Kramer p-value adjustment test was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. The results are shown in Table 1. For P1, except for the comparison between the HA and PSAP1 and between PSAP2 and PSAP3, all pairwise comparisons were significant. Similar analyses were conducted for the P2 data. The results indicated that the effect of device on SII was significant, F(4, 96) = 63.84, p < .0001. Post hoc analyses further indicated that all pairwise comparisons were significant in P2 (see Table 1). In short, the analyses indicated that the HA generally yielded higher SII than the PSAPs and that aided SIIs were higher than unaided SIIs.

Figure 5.

Box plots of better ear Speech Intelligibility Index measures for each device (and unaided) obtained on-ear using a 65-dB SPL speech input in each of the first (P1) and second (P2) user programs of the device. The boundaries of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the thin line within the boxes marks the median. Thick lines represent the means. Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

Table 1.

p values and t statistics of post hoc pairwise comparisons for Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) and speech recognition threshold (SRT) in quiet.

| Comparison | Tukey–Kramer adjusted p value (t statistic) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| SII, P1 | SII, P2 | SRT in quiet | |

| HA vs. PSAP1 | .0904 (2.54) | .0004 (4.31) | .0708 (−2.64) |

| HA vs. PSAP2 | < .0001 (7.76) | < .0001 (7.41) | < .0001 (−5.82) |

| HA vs. PSAP3 | < .0001 (8.1) | < .0001 (11.22) | < .0001 (−5.65) |

| PSAP1 vs. PSAP2 | < .0001 (5.22) | .0209 (3.1) | .0166 (−3.18) |

| PSAP1 vs. PSAP3 | < .0001 (5.56) | < .0001 (6.9) | .0273 (−3.01) |

| PSAP2 vs. PSAP3 | .9972 (0.34) | .0023 (3.8) | .9998 (0.17) |

| HA vs. Unaided | < .0001 (14.88) | < .0001 (14.39) | < .0001 (−11.78) |

| PSAP1 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (12.34) | < .0001 (10.08) | < .0001 (−9.14) |

| PSAP2 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (7.12) | < .0001 (6.98) | < .0001 (−5.96) |

| PSAP3 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (6.78) | .0169 (3.17) | < .0001 (−6.13) |

Note. P1 and P2: the first and second user programs of the device. Bold emphasis indicates statistical significance. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

HINT

Figure 6 shows the SRTs in quiet (A) and in noise (B), measured using the HINT, as a function of device condition. Note that SRTs measured in the quiet and noise conditions are expressed in dBA and dB, respectively. The y-axis of the figure has been reversed so that the top of the figure represents better performance. Similar to the analysis conducted for the SII, a linear mixed model was used to determine the effect of device on SRT in quiet. The model indicated that device had a significant effect on SRT in quiet, F(4, 96) = 38.7, p < .0001. Post hoc analyses (Tukey–Kramer adjustment) were further conducted, and the results are shown in Table 1. Except for the comparisons between the HA and PSAP1 and between PSAP2 and PSAP3, all pairwise comparisons were significant. The results showed that the HA outperformed PSAP2 and PSAP3 and that aided listening had lower (better) SRTs in quiet than unaided listening. A similar linear mixed model was used to determine the effect of device condition on SRT in noise. The model indicated that the effect was not statistically significant, F(4, 96) = 1.9, p = .11.

Figure 6.

Box plots of speech recognition threshold (SRT) in quiet (A) and noise (B) measured using the Hearing in Noise Test as a function of device condition. The y-axis has been reversed so that the top of the figure represents better performance. The boundaries of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the thin line within the boxes marks the median. Thick lines represent the means. Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

CST

Boxplots of mean CST score in percent correct for each device condition in each PLS are shown in Figure 7A. Higher scores represent better performance. Recall that the PLSs were designed to reflect real-world speech listening situations, and the characteristics of each PLS can be found in Figure 3. To determine the effect of device on CST score, a linear mixed model that included a random intercept for subject to account for the repeated observations per participant, with fixed effects being device condition (five levels: HA, three PSAPs, and unaided) and PLS (six PLSs) and the interaction between device and PLS, was used. Before analysis, original percent correct scores of the CST were transformed into rationalized arcsine units (Studebaker, 1985) to homogenize the variance.

Figure 7.

Box plots of the Connected Speech Test score (in percent correct) for each device condition in each prototype listening situation (PLS) (A) and collapsed across all PLSs (excluding PLS4) (B). Higher scores represent better performance. The boundaries of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the thin line within the boxes marks the median. Thick lines represent the means. Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

Results from the model first indicated that the interaction between device and PLS was significant (p < .05). Therefore, the pattern of the CST mean scores across the five device conditions was inspected. It was determined that the CST score pattern of PLS4 was different from other PLSs (see Figure 7A). It was further found that when the PLS4 data were excluded from the linear mixed model, the interaction between device and PLS was no longer significant. Therefore, two separate linear mixed models were fit to the CST data: one for the data without PLS4 and one for PLS4 only. See Figure 7B for the CST score collapsed across all PLSs, excluding PLS4.

For the model that excluded the PLS4 data, the model only contained the main effect of device and PLS; the interaction term was not included because it was not significant. The results indicated that both effects of device, F(4, 587) = 39.63, p < .0001, and PLS, F(4, 587) = 20.05, p < .0001, were significant. Post hoc analyses with a Tukey–Kramer adjustment were further conducted to compare the CST scores (all five PLSs data collapsed) between device conditions. The results are shown in Table 2. Except for the comparisons between the three PSAPs (PSAP1 vs. PSPA2, PSAP1 vs. PSAP3, and PSAP2 vs. PSAP3), all pairwise comparisons were significant, showing that the HA outperformed all three PSAPs and that aided speech recognition performance was better than unaided performance. For the model that only included the PLS4 data, the effect of device was not statistically significant, F(4, 95) = 2.37, p = .058.

Table 2.

p values and t statistics of post hoc pairwise comparisons for the Connected Speech Test (CST) scores, listening effort ratings, and sound quality ratings.

| Comparison | Tukey–Kramer adjusted p value (t statistic) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CST | Listening effort | Sound quality | |

| HA vs. PSAP1 | .0028 (3.64) | .8063 (1.1) | .9877 (0.33) |

| HA vs. PSAP2 | .0058 (3.43) | .0128 (3.19) | .1632 (2.07) |

| HA vs. PSAP3 | < .0001 (5.89) | < .0001 (5.51) | .0103 (3.12) |

| PSAP1 vs. PSAP2 | .9996 (−0.21) | .2246 (2.09) | .3017 (1.74) |

| PSAP1 vs. PSAP3 | .1639 (2.25) | .0001 (4.41) | .0278 (2.79) |

| PSAP2 vs. PSAP3 | .1029 (2.45) | .1403 (2.32) | .7225 (1.05) |

| HA vs. Unaided | < .0001 (12.04) | < .0001 (10.91) | |

| PSAP1 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (8.44) | < .0001 (9.83) | |

| PSAP2 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (8.65) | < .0001 (7.76) | |

| PSAP3 vs. Unaided | < .0001 (6.22) | < .0001 (5.47) | |

Note. All analyses were conducted with the data from all six prototype listening situations combined, with the exception that the PLS4 data were not included in the CST data analysis. Bold emphasis indicates statistical significance. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product; PLS = prototype listening situation.

Listening Effort

The mean self-reported listening effort rating of each PLS is shown in Figure 8A. Data were linearly transformed by subtracting the raw score from 100 so that higher ratings correspond to less listening effort. This transformation was implemented to create visual coherence between the figures. A linear mixed model was used to analyze the data. The analysis first indicated that the interaction between device condition and PLS was not statistically significant. Therefore, the interaction term was excluded from the model, and the final model only contained the main effect of device and PLS. See Figure 8B for the listening effort rating collapsed across all PLSs. The results from the final model further indicated that the effects of device, F(4, 710) = 37.29, p < .0001, and PLS, F(5, 710) = 28.09, p < .0001, were significant. Post hoc analyses with a Tukey–Kramer adjustment were conducted to compare the listening effort ratings (all six PLSs data collapsed) between device conditions. The results are shown in Table 2. Except for the comparisons between the HA and PSAP1, between PSAP1 and PSAP2, and between PSAP2 and PSAP3, all the pairwise comparisons were statistically significant, showing that the HA generally outperformed the PSAPs and that aided listening was less effortful than unaided listening.

Figure 8.

Box plots of self-reported listening effort rating for each device condition in each prototype listening situation (PLS) (A) and collapsed across all PLSs (B). Higher scores represent better performance. The boundaries of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the thin line within the boxes marks the median. Thick lines represent the means. Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

Sound Quality

Figure 9A shows the results of sound quality ratings across devices and PLSs. Recall that sound quality rating was not administered in the unaided condition. A similar linear mixed model was used to analyze the data. The result first indicated that the interaction between device and PLS was not statistically significant. Therefore, the interaction term was excluded from the final model. See Figure 9B for the sound quality rating collapsed across all PLSs. The results of the final model indicated that the effects of device, F(3, 567) = 4.34, p = .0049, and PLS, F(5, 567) = 17.51, p < .0001, were significant. Post hoc analyses with a Tukey–Kramer adjustment (see Table 2) indicated that PSAP3 had poorer sound quality than the HA and PSAP1. No other pairwise comparisons were statistically significant.

Figure 9.

Box plots of self-reported sound quality rating for each device condition in each prototype listening situation (PLS) (A) and collapsed across all PLSs (B). Higher scores represent better performance. The boundaries of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the thin line within the boxes marks the median. Thick lines represent the means. Error bars indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. HA = hearing aid; PSAP = personal sound amplification product.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the effect of self-adjusted PSAPs compared to audiologist-fitted hearing aids in ecologically relevant test environments. Outcome measures included audibility, speech recognition, listening effort, and sound quality.

REAR and SII

For the three PSAPs evaluated in the current study, PSAP2 and PSAP3 provided much less gain at frequencies above 2000 Hz when compared to the REAR targets specified by NAL-NL2 (see Figure 4). This is consistent with the literature, which has indicated that many PSAPs and OTC devices have gain frequency responses with a low-frequency emphasis (Callaway & Punch, 2008; Chan & McPherson, 2015; Cheng & McPherson, 2000). In contrast, PSAP1 provided a considerable amount of high-frequency gain and had REARs similar to the HA. Because, in the current study, the participants selected the preset and used the equalizer feature in the smartphone app to adjust the gain frequency responses of PSAP1, the similarity in REAR between the HA and PSAP1 seems to suggest that older adults are capable of self-adjusting the frequency responses of amplification devices. However, note that the majority of the participants involved in this study were experienced hearing aid users; they might try to configure PSAP1 to amplify sounds similarly to their hearing aids. It is unknown if newer users or those with less experience would configure the device's frequency responses in the same way. The SII data shown in Figure 5 reflect the REARs shown in Figure 4. The HA provided the most audibility as it most closely matched prescriptive targets, specifically in the high frequencies. Note that, although PSAP2 and PSAP3 provided less audibility than the HA and PSAP1, all devices improved audibility compared to the unaided condition.

HINT

Because the SRT in quiet is mainly determined by the audibility of speech sounds (Soli & Wong, 2008), it is not surprising that the result of the HINT in quiet was in accordance with the SII data. Participants had the best performance (lowest SRT) with the HA and PSAP1 (see Figure 6A), and all aided conditions showed better performance than the unaided condition. In contrast, SRT in noise measured using the HINT did not differ across device condition (see Figure 6B). This is likely because speech recognition performance in noise is mainly affected by SNR rather than hearing thresholds, especially when the noise is presented at a suprathreshold level (Soli & Wong, 2008). Because the SRT in noise was measured with the devices set to P2, in which directional microphones and noise reduction algorithms were enabled, the similarity of SRT across the four aided conditions seems to suggest that these features of the four devices had similar effects. However, the result that the SRTs in noise in the aided conditions were not lower (better) than the unaided condition is unexpected. Previous studies suggest that hearing aids equipped with directional microphones could improve HINT scores by 2–4 dB compared to unaided listening in noise (Bentler, Palmer, & Mueller, 2006; Gnewikow, Ricketts, Bratt, & Mutchler, 2009). It is possible that the benefit provided by the directional microphones in the devices evaluated in the current study was offset by the loss of natural directivity provided by the pinna in the aided conditions.

CST

Significant differences between devices were observed for the CST score across all PLSs, excluding PLS4 (see Figure 7). The lack of variance seen in PLS4, in which visual cues were available, is likely due to the ceiling performance. This is consistent with previous research, which demonstrated that the ceiling performance caused by visual cues could diminish the effect of hearing aid features, such as directional microphones, on speech recognition (Wu & Bentler, 2010). Statistical analyses further indicated that, for all PLSs, excluding PLS4, speech recognition performance with the HA was significantly better than all PSAPs (see Table 2). This finding seems to contradict the results of Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017), which indicated that the hearing aid and three of their best PSAPs yielded comparable speech recognition performance. However, in the current study, the difference in CST score between the HA (96.7%) and the three PSAPs (94.1%, 94.5%, and 92.3% for PSAP1, PSAP2, and PSAP3, respectively), albeit statistically significant, was small, ranging from 2.2 to 4.4 percentage points (see Figure 7B). This is in line with the small difference in speech recognition performance (ranging from 1 to 4 percentage points) between the hearing aid (88.4%) and three of their best PSAPs (87.4%, 86.7%, and 84.1%) reported by Reed et al. Therefore, both the current study and Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017) indicated that, although audiologist-fitted hearing aids outperformed mid- to high-end PSAPs, the difference was small. In the current study, devices were fitted using a relatively realistic fitting scheme, and speech recognition performance was measured in ecologically relevant conditions. The current study, therefore, expanded the findings of Reed, Betz, Kendig, et al. (2017), suggesting that the effect of hearing aids and PSAPs on speech understanding in the real world could be similar. Finally, both studies supported the benefit of midlevel and high-end PSAPs in improving speech recognition performance relative to an unaided condition.

Listening Effort

Compared to the CST, results of self-reported listening effort showed less of a ceiling effect (see Figure 8). This is consistent with the literature showing that listening effort measures are still sensitive to change even when speech recognition performance is at the ceiling level (e.g., Sarampalis et al., 2009; Winn, Edwards, & Litovsky, 2015). Regardless, results of listening effort were in line with the CST, as the HA outperformed most PSAPs and there were few differences between the PSAPs. In addition, all aided conditions significantly reduced participants' listening effort compared to unaided listening (see Table 2).

Sound Quality

Minimal significant differences in sound quality were observed across devices (see Table 2). This result is somewhat similar to the findings of Xu et al. (2015), which showed a significant preference for the sound quality of hearing aids over PSAPs only when listening to quiet conversation and no differences in sound quality between the devices for listening to everyday noises or music. Results of the current study and Xu et al. (2015) suggest that modern midlevel and high-end PSAPs could provide sound quality comparable to traditional hearing aids. Note that, in the current study, although the gain frequency responses of the HA and PSAPs varied considerably (see Figure 4), few sound quality differences were observed between devices. This is consistent with Jenstad et al. (2007), which found listeners rated sound quality similarly for a wide range of gain frequency response settings.

Limitations

A limitation of the current study is its generalizability to the PSAP market. Only three PSAPs were used in the study, whereas PSAPs consist of a wide range of devices that vary considerably in style, size, quality, and technology level. Further research using a wider range of PSAPs is needed in order to better generalize their abilities relative to hearing aids. In addition, the focus of this study was device performance in ecologically relevant situations rather than service delivery model. Participants were only responsible for reporting their preferences when adjusting the devices, not for learning how they are used or setting up the devices and smartphone apps. Eliminating these factors likely overestimated the benefits of PSAP usage in the real world as individual learning abilities were not assessed. Previous studies have reported that only 55% of adults were able to perform the hearing aid self-fitting procedure—either independently or with the assistance of a layperson—without error (Convery, Keidser, Seeto, & McLelland, 2017). A field trial is needed to assess the devices and determine real-world comparisons outside of the laboratory.

Another limitation of the current study is the characteristics of participants, specifically with regard to hearing aid experience. As discussed above, those who do not have experience with amplification may configure the device's frequency response (for PSAP1) differently compared to experienced users. Furthermore, the preferred volume level might be different for experienced and inexperienced users (Marriage, Moore, & Alcántara, 2004). Because the majority of the participants involved in this study were experienced hearing aid users, it is unknown if the results can be generalized to individuals who have no hearing aid experience.

Clinical Implications

Although the current study indicated that a hearing aid fitted using best-practice verification protocols provided the best outcomes compared to a range of readily available PSAPs, the small differences in such outcomes seem to suggest that PSAPs could serve as a practical, budget-friendly option for those who cannot afford traditional amplification. Advances in technology and smartphone capabilities make the idea of successful PSAPs or OTC devices more feasible given features such as equalizers and in situ audiometry where customers can better self-fit their device. Applications such as this could be beneficial so long as consumers understand how to properly use them.

Conclusions

Hearing aids fitted using best-practice verification protocols were capable of providing significantly more aided audibility, better speech recognition performance, and lower listening effort compared to the mid- to high-level PSAPs tested in the current study. Differences in sound quality between the devices were minimal. However, because all PSAPs tested in the current study significantly improved participants' speech recognition performance and reduced their listening effort compared to unaided listening, PSAPs could serve as a feasible, budget-friendly option for those who cannot afford traditional amplification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant awarded to Yu-Hsiang Wu from the Retirement Research Foundation.

Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the American Auditory Society, March, 2017, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, and the annual meeting of the Iowa Speech and Hearing Association, October, 2017, Des Moines, Iowa, USA.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by a grant awarded to Yu-Hsiang Wu from the Retirement Research Foundation. Portions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the American Auditory Society, March, 2017, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, and the annual meeting of the Iowa Speech and Hearing Association, October, 2017, Des Moines, Iowa, USA.

References

- Abrams, H. B. , & Kihm, J. (2015). An introduction to MarkeTrak IX: A new baseline for the hearing aid market. Hearing Review, 22(6), 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, G. , Hines, A. , & Johnson, J. (2018). Does cognition affect potential benefits of audiologic intervention with OTCs? Paper presented at the American Auditory Society Annual Meeting, Scottsdale, Arizona. Retrieved from http://www.harlmemphis.org/files/1115/2001/8824/OTC_AAS_Poster_Final2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute. (2010). Method of measurement of performance characteristics of hearing aids under simulated in-situ working conditions (ANSI S3.35-2010) . New York, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American National Standards Institute. (2012). Methods for calculation of the Speech Intelligibility Index (ANSI S3.5-1997) (R2012) . New York, NY: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, R. , Palmer, C. , & Mueller, G. H. (2006). Evaluation of a second-order directional microphone hearing aid: I. Speech perception outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 17(3), 179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boymans, M. , & Dreschler, W. A. (2012). Audiologist-driven versus patient-driven fine tuning of hearing instruments. Trends in Amplification, 16(1), 49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway, S. L. , & Punch, J. L. (2008). An electroacoustic analysis of over-the-counter hearing aids. American Journal of Audiology, 17(1), 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Z. Y. T. , & McPherson, B. (2015). Over-the-counter hearing aids: A lost decade for change. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C. M. , & McPherson, B. (2000). Over-the-counter hearing aids: Electroacoustic characteristics and possible target client groups. International Journal of Audiology, 39(2), 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convery, E. , Keidser, G. , Seeto, M. , & McLelland, M. (2017). Evaluation of the self-fitting process with a commercially available hearing aid. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 28(2), 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, R. M. , & Alexander, G. C. (1995). The abbreviated profile of hearing aid benefit. Ear and Hearing, 16(2), 176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, R. M. , Alexander, G. C. , & Gilmore, C. (1987). Development of the Connected Speech Test (CST). Ear and Hearing, 8(5), 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnewikow, D. , Ricketts, T. , Bratt, G. W. , & Mutchler, L. C. (2009). Real-world benefit from directional microphone hearing aids. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 46(5), 603–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard, S. , Ruf, S. , Egger, C. , & Abrams, H. (2016). Hearing aids improve hearing–and a lot more. The Hearing Review, 23(6), 14. [Google Scholar]

- Humes, L. E. , Rogers, S. E. , Quigley, T. M. , Main, A. K. , Kinney, D. L. , & Herring, C. (2017). The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Audiology, 26(1), 53–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenstad, L. M. , Bagatto, M. P. , Seewald, R. C. , Scollie, S. D. , Cornelisse, L. E. , & Scicluna, R. (2007). Evaluation of the desired sensation level [input/output] algorithm for adults with hearing loss: The acceptable range for amplified conversational speech. Ear and Hearing, 28(6), 793–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. , Xu, J. , Cox, R. , & Pendergraft, P. (2015). A comparison of two methods for measuring listening effort as part of an audiologic test battery. American Journal of Audiology, 24, 419–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidser, G. , Dillon, H. , Flax, M. , Ching, T. , & Brewer, S. (2011). The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Research, 1(1), 88–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochkin, S. (2007). MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non‐user adoption of hearing aids. The Hearing Journal, 60(4), 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kochkin, S. (2010). MarkeTrak VIII: Utilization of PSAPs and direct-mail hearing aids by people with hearing impairment. Hearing Review, 17(6), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marriage, J. , Moore, B. C. , & Alcántara, J. I. (2004). Comparison of three procedures for initial fitting of compression hearing aids. III. Inexperienced versus experienced users. International Journal of Audiology, 43(4), 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow, C. D. , Aguilar, C. , Endicott, J. E. , Tuley, M. R. , Velez, R. , Charlip, W. S. , … DeNino, L. A. (1990). Quality-of-life changes and hearing impairment: A randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 113(3), 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. (2016). Quick statistics about hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

- Nilsson, M. , Soli, S. D. , & Sullivan, J. A. (1994). Development of the Hearing in Noise Test for the measurement of speech reception thresholds in quiet and in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95(2), 1085–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, Executive Office of the President. (2015). Aging America & hearing loss: Imperative of improved hearing technologies. Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_hearing_tech_letterreport_final.pdf

- Reed, N. S. , Betz, J. , Kendig, N. , Korczak, M. , & Lin, F. R. (2017). Personal sound amplification products vs a conventional hearing aid for speech understanding in noise. Journal of The American Medical Association, 318(1), 89–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, N. S. , Betz, J. , Lin, F. R. , & Mamo, S. K. (2017). Pilot electroacoustic analyses of a sample of direct-to-consumer amplification products. Otology & Neurotology, 38(6), 804–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts, T. (2000). Impact of noise source configuration on directional hearing aid benefit and performance. Ear and Hearing, 21(3), 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarampalis, A. , Kalluri, S. , Edwards, B. , & Hafter, E. (2009). Objective measures of listening effort: Effects of background noise and noise reduction. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52(5), 1230–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, S. , & Sims, R. (2015). Comparison of psychophysiological and dual-task measures of listening effort. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58, 1781–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. , Wilber, L. A. , & Cavitt, K. (2016). PSAPs vs hearing aids: An electroacoustic analysis of performance and fitting capabilities. Hearing Review, 23(7), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Solheim, J. , Gay, C. , & Hickson, L. (2017). Older adults' experiences and issues with hearing aids in the first six months after hearing aid fitting. International Journal of Audiology, 57(1), 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soli, S. D. , & Wong, L. L. (2008). Assessment of speech intelligibility in noise with the Hearing in Noise Test. International Journal of Audiology, 47(6), 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studebaker, G. A. (1985). A rationalized arcsine transform. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 28, 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2013. November 7). Regulatory requirements for hearing aid devices and personal sound amplification products—Draft guidance for industry and food and drug administration staff. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ucm373461.htm

- Walden, B. E. (1997). Toward a model clinical-trials protocol for substantiating hearing aid use benefit claims. American Journal of Audiology, 6, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, M. B. , Edwards, J. R. , & Litovsky, R. Y. (2015). The impact of auditory spectral resolution on listening effort revealed by pupil dilation. Ear and Hearing, 36(4), 153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. H. , & Bentler, R. A. (2010). Impact of visual cues on directional benefit and preference: Part I—Laboratory tests. Ear and Hearing, 31(1), 22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. H. , Stangl, E. , Chipara, O. , Hasan, S. S. , Welhaven, A. , & Oleson, J. (2018). Characteristics of real-world signal to noise ratios and speech listening situations of older adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear and Hearing, 39(2), 293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. , Johnson, J. , Cox, R. , & Breitbart, D. (2015). Laboratory comparison of PSAPs and hearing aids. Paper presented at the American Auditory Society Annual Meeting, Scottsdale, Arizona. Retrieved from http://www.harlmemphis.org/files/9814/2593/1864/XuAAS2015_PSAPs.pdf [Google Scholar]