Abstract

Cell surface integrins mediate interactions between cells and their extracellular matrix and are frequently exploited by a range of bacterial pathogens to facilitate adherence and/or invasion. In this study we examined the effects of Porphyromonas gingivalis proteases on human gingival fibroblast (HGF) integrins and their fibronectin matrix. Culture supernatant from the virulent strain W50 caused considerably greater loss of the β1 integrin subunit from HGF in vitro than did that of the beige-pigmented strain W50/BE1. Prior treatment of the W50 culture supernatant with the protease inhibitor Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) blocked its effects on cultured cells, indicating that this process is proteolytically mediated. Purified arginine-specific proteases from P. gingivalis W50 were able to mimic the effects of the whole-culture supernatant on loss of β1 integrin expression. However purified RI, an α/β heterodimer in which the catalytic chain is associated with an adhesin chain, was 12 times more active than RIA, the catalytic monomer, in causing loss of the α5β1 integrin (fibronectin receptor) from HGF. No effect was observed on the αVβ3 integrin (vitronectin receptor). The sites of action of RI and RIA were investigated in cells exposed to proteases pretreated with TLCK to inactivate the catalytic component. Use of both monoclonal antibody 1A1, which recognizes only the adhesin chain of RI, and a rabbit antibody against P. gingivalis whole cells indicated localization of RI on the fibroblasts in a clear, linear pattern typical of that seen with fibronectin and α5β1 integrin. Exact colocalization of RI with fibronectin and its α5β1 receptor was confirmed by double labeling and multiple-exposure photomicroscopy. In contrast, RIA bound to fibroblasts in a weak, patchy manner, showing only fine linear or granular staining. It is concluded that the adhesin component of RI targets the P. gingivalis arginine-protease to sites of fibronectin deposition on HGF, contributing to the rapid loss of both fibronectin and its main α5β1 integrin receptor. Given the importance of integrin-ligand interactions in fibroblast function, their targeted disruption by RI may represent a novel mechanism of damage in periodontal disease.

The proteolytic enzymes of Porphyromonas gingivalis are widely recognized as important virulence factors of this organism. In addition to enabling it to access essential nutrients, they may also perturb host defense and tissue homeostasis mechanisms by degrading a range of host proteins including plasma proteinase inhibitors and immunoglobulins, dysregulating coagulation, complement, and kallikrein/kinin cascade pathways (7, 29), interfering with cellular functions (14), and degrading periodontal tissue components directly (2, 27, 30) and indirectly (28). These mechanisms may all contribute to the role of P. gingivalis as a major causative organism in human periodontal disease (26, 33). In animal model systems using subcutaneous inoculation, greater protease activity has also been associated with increased virulence of P. gingivalis (12, 18).

The trypsin-like enzyme activity of this bacterium, which has been the focus of much research, is now known to be due to a mixture of proteases with individual specificity for arginine and lysine residues (21). These proteases are associated with membrane vesicles and may also be released extracellularly. Partially purified bacterial fractions with proteolytic activity have been shown to degrade basement membrane collagen, elastin, and fibronectin (27, 30) and to stimulate the secretion of collagenase and plasminogen activator by cultured gingival fibroblasts, thereby inducing the host cells to degrade their own pericellular matrix (31). Such matrix degradation may lead to the marked loss of connective tissue integrity which is typical of destructive periodontal disease.

Cells bind to extracellular matrix components via interaction with integrin surface receptors which are linked through their intracellular domains to the cytoskeleton. Integrin receptors and their ligands are known to be targets for binding by a number of pathogens which exploit this group of molecules in order to adhere to and/or invade host cells (13, 19). We have previously shown that components of the culture supernatant of P. gingivalis W83 can damage human gingival fibroblast (HGF) integrin-substrate interactions, with the α5 and β1 integrin subunits—the receptor for fibronectin—being considerably more susceptible than αV and β3—the receptor for vitronectin (24). These effects were reduced by heating the supernatant, implicating heat-labile proteins such as bacterial proteases. Here we report similar effects with the supernatant from the virulent P. gingivalis strain W50 but not the nonpigmented avirulent variant (W50/BE1) and, using purified arginine-specific proteases from strain W50, examine their site and mechanism of action on HGF in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial culture and supernatant preparation.

P. gingivalis W50 and W50/BE1 were grown in brain heart infusion broth supplemented with hemin (5 mg liter−1) in an atmosphere of 80% N2, 10% H2, and 10% CO2 at 37°C for 6 days. Culture supernatants obtained by centrifugation (11,000 × g for 20 min at 5°C) were sterilized by passage through 0.2-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate membranes and stored at −70°C.

Arginine-specific protease activity was measured by hydrolysis of l-benzoyl-dl-arginine para-nitroanilide (BApNA) as described by Rangarajan et al. (23). One unit of protease activity is defined as the amount of enzyme causing an increase in A405 of 1.0 min−1.

Treatment of supernatant with protease inhibitor.

Samples of filter-sterilized culture supernatant were monitored for arginine-specific protease activity, and the enzyme activity was then irreversibly inactivated by incubation for 30 min at 4°C with 1 mM Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) in the presence of 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol and CaCl2 (23). Excess inhibitor was removed by dialysis using 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.3). Further samples of supernatant, not treated with inhibitor, were dialyzed as controls, and the protease assay was repeated. The enzyme activity of the inhibitor-treated supernatant was compared with that of the dialyzed control supernatant.

Purification of arginine-specific proteases.

The arginine-specific proteases (RI and RIA) from strain W50 were purified as described previously (23), using a combination of ammonium sulfate precipitation, affinity chromatography on arginine-agarose, and ion-exchange chromatography. Both RI and RIA were stored at 4°C in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer and neutralized with 1 N NaOH immediately before use with cultured fibroblasts. Where indicated, samples were treated with TLCK as described above.

HGF culture and treatment with P. gingivalis preparations.

HGF obtained from clinically healthy gingival tissue were grown at subconfluent concentrations on 13-mm-diameter glass coverslips as previously described (24). The culture medium was Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (Globepharm Ltd., Surrey, England), penicillin (50 IU/ml), streptomycin (50 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml) (Life Technologies). After incubation overnight to allow attachment, cells were exposed for 1 h at 37°C to doubling dilutions of W50 (1/2 to 1/256) and W50/BE1 (1/2 to 1/64) culture supernatant, TLCK-treated W50 culture supernatant (1/2 to 1/16), RI (protease activity 1.6 to 0.006 U/ml) and RIA (protease activity 1.4 to 0.175 U/ml), RI and RIA with or without 5 mM l-cysteine, and RI and RIA with or without TLCK treatment. Cell monolayers exposed to purified proteases were prewashed in serum- and supplement-free DMEM, and doubling dilutions made in this medium as the presence of serum protein interfered with the activity of purified proteases. Each experiment was repeated at least three times using different HGF cell lines.

Following incubation with P. gingivalis preparations, cells were fixed for 5 min at 4°C in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and then reacted to demonstrate integrin subunits, fibronectin, and/or P. gingivalis components.

Immunofluorescence studies.

The mouse monoclonal antibody against the β1 integrin subunit (clone DF7; Affiniti Research Products Ltd., Exeter, England) was used in all experiments. Additional primary antibodies, used where indicated in Results, were mouse monoclonal antibodies against α5 and αV integrin subunits (P1D6 and VNR 147, respectively; Life Technologies), β3 subunit (clone BB10, purified; Chemicon International Ltd., Harrow, England), and fibronectin (clone Fn-3; Cymbus Bioscience Ltd., Southampton, England). Localization of the purified proteases was examined by using rabbit antiserum raised against P. gingivalis W50 whole cells (PgWC) (9) and monoclonal antibody 1A1 (6), which reacts only with the β component of the RI heterodimer (8). All primary antibodies were diluted in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.05% (wt/vol) sodium azide and 5% (vol/vol) human serum and used at 1/100 except PgWC, which was diluted to 1/20,000. Omission of the primary antibodies served as the negative controls. After washing in PBS, cells used for single-labelling studies were incubated for 60 min with a 1/200 concentration of biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (B0529; Sigma Chemical Company Ltd., Poole, England) or swine anti-rabbit antibody (code EO353; Dako Ltd., High Wycombe, England) as appropriate, followed by a 1/100 concentration of streptavidin-Texas red complex (RPN 1233; Amersham International, Little Chalfont, England) for 60 min. Double-labelling studies with mouse primary antibodies against integrins or fibronectin combined with PgWC antibody used fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Fab specific) (F5262; Sigma) at 1/50 dilution in addition to the biotin-conjugated swine anti-rabbit secondary antibody followed by streptavidin-Texas red as described above. All coverslips were mounted on glass slides by using Immumount [Life Sciences International (UK) Ltd., Hampshire, England) containing 1,4-diazabicyclo [2,2,2] acetone (2.5 mg/ml) to reduce fading and viewed with a Nikon Microphot FXA microscope equipped for epifluorescence with excitation filters of 460 to 500 and 510 to 560 nm.

β1 integrin staining patterns were examined in a minimum of 100 cells across each coverslip, and cells were classified into the following five categories: diffuse background staining only (staining grade 0); cells with mainly diffuse background staining plus scattered, small, granular, fluorescent deposits (staining grade 1); cells with granular, fluorescent staining, frequently arranged in a linear pattern, with occasional additional short linear bands of staining (staining grade 2); cells showing bands of strongly staining integrin with some fragmentation (staining grade 3); and cells with long, thick and generally straight bands of strongly staining integrin across most of the cytoplasm (staining grade 4).

The majority of untreated HGF grown in DMEM displayed the maximum (grade 4) integrin staining, which remained unchanged if supplements were removed for the final incubation. However, in some cultures a few cells lacked the typical strongly staining linear pattern across most of the cytoplasm and showed sparse linear or occasionally granular staining, indicating the heterogeneity of the population. In each experiment, the grade reflecting the majority of the population, i.e., the median, was used for data analysis.

RESULTS

Comparative effects of culture supernatant from P. gingivalis W50 and W50/BE1 on β1 integrin in HGF.

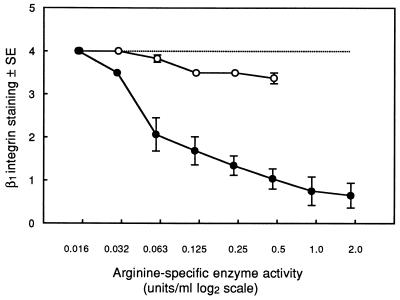

HGF incubated for 1 h with strain W50 culture supernatant displayed a dose-dependent loss of β1 integrin staining, with control levels reached at or below a 1/256 concentration. In contrast, culture supernatant from W50/BE1 produced only minor loss of β1 integrin even at the highest concentration used (1/2), and control levels were seen at a 1/32 concentration (Fig. 1). The arginine-specific protease activities of undiluted W50 and W50/BE1 culture supernatants were 3.75 and 0.95 U/ml, respectively, and W50 supernatant demonstrated greater loss of β1 integrin staining than W50/BE1 at all comparable enzyme activities.

FIG. 1.

β1 staining in HGF incubated for 1 h with culture supernatant from strains W50 (●) and W50/BE1 (○). The maximum concentration of each supernatant used was a 1/2 dilution in DMEM. The arginine-specific enzyme activities of doubling dilutions of the culture supernatants are shown on a log2 scale. Integrin staining was graded as described in Materials and Methods. The results represent the mean integrin grade ± standard error (SE) from five separate experiments for W50 and three for W50/BE1. Integrin staining in control cultures incubated in DMEM is indicated by the dotted line.

To test the effect of TLCK treatment of supernatant on HGF, it was necessary to remove excess inhibitor by dialysis, as it is toxic to cultured cells. Dialyzed W50 culture supernatant retained 64% of the arginine-specific protease activity of the undialyzed supernatant and demonstrated less reduction in HGF β1 integrin staining levels than its undialyzed counterpart, although a similar dose-response pattern was observed (data not shown). After TLCK treatment, arginine-protease activity of the W50 supernatant was inhibited by ≥98% and no loss of β1 staining was seen, even at the maximum supernatant concentration tested. These observations indicated that the loss of integrin staining was proteolytically mediated. We therefore examined the effects of P. gingivalis proteases on integrin staining.

Action of RI and RIA on integrin staining.

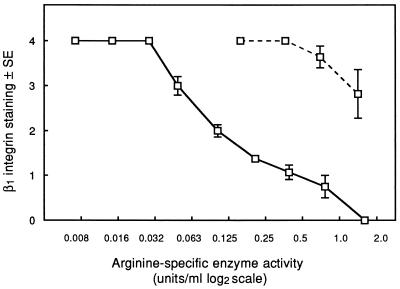

RI is an ∼110-kDa heterodimer containing two subunits: an α component with protease activity and a β component of similar size which possesses adhesin-like properties (8, 23). RIA is a monomer of only the catalytic α chain. Incubation of HGF with each of these purified proteases caused dose-dependent losses of β1 integrin staining (Fig. 2). However, at comparable arginine-specific protease activities, RI was considerably more active that RIA, with control integrin levels reached at activities of ≤0.03 U/ml for RI, compared with 0.36 U/ml for RIA, indicating a 12-fold increase in activity of RI. In certain experiments, a final concentration of 5 mM l-cysteine was included in the HGF culture medium during incubation with the purified proteases. This enhanced the β1 integrin loss between two- to fourfold compared with cultures from which l-cysteine was omitted.

FIG. 2.

β1 integrin staining in HGF incubated for 1 h with RI (solid line) and RIA (dashed line) in DMEM without supplements. β1 integrin staining, as described previously, is plotted against arginine-specific enzyme activity on a log2 scale. The results represent the mean integrin grade ± standard error (SE) from five separate experiments.

Treatment of RI and RIA with 1 mM TLCK inhibited arginine-specific protease activity by 98%. HGF incubated with TLCK-treated RI and RIA, at final concentrations equivalent to 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 Units of arginine-specific enzyme activity per ml prior to TLCK inhibition, showed β1 integrin staining patterns indistinguishable from those of control cells in DMEM, again supporting a proteolytically mediated mechanism for the loss of β1 integrin staining.

These investigations were extended to examine effects of RI treatment of HGF on other integrin subunits. Incubation of cells for 1 h with RI at 0.2 to 0.4 U of arginine-specific enzyme activity per ml, i.e., levels which produced severe disruption of β1 integrin staining, also caused marked disruption of the linear staining pattern of the α5 integrin subunit, whereas the peripheral αV and β3 integrin staining remained unaffected even when the incubation period was extended to 24 h.

Localization of P. gingivalis components in HGF cultures treated with TLCK-inactivated proteases.

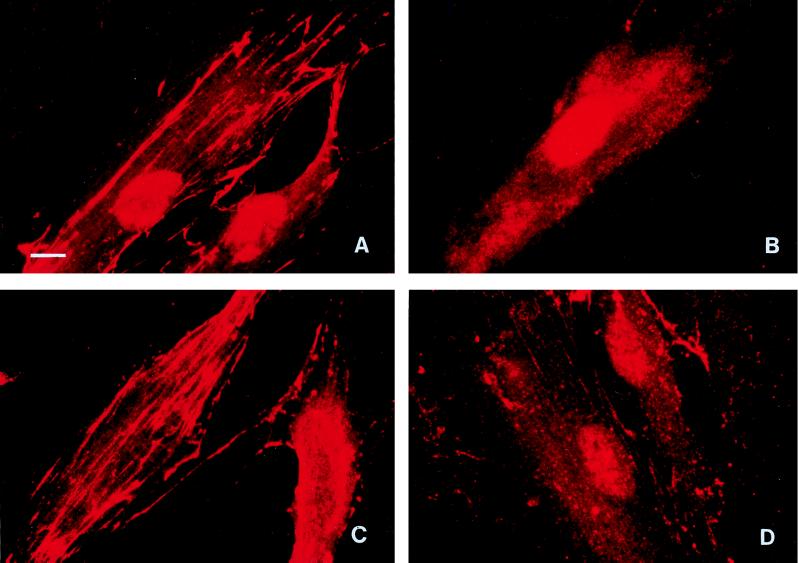

As RI differs from RIA only in the possession of a β chain in addition to the catalytic α chain, this indicated that the β component contributed to the greater loss of integrin expression that we observed with RI. The sites of binding of these proteases to HGF were then examined by incubating cells with TLCK-treated RI and RIA, in which all proteolytic activity had been inhibited, followed by immunofluorescent labelling with antibodies 1A1 and PgWC. With monoclonal antibody 1A1, which binds to the β chain of RI (8), RI-treated cells showed a linear staining pattern along the long cytoplasmic axis (Fig. 3A) typical of that seen with β1 and α5 integrins. In addition, a network of strong intercellular staining, which was particularly prominent at low magnification, was visible across the cell monolayer. In contrast, RIA-treated cells displayed only diffuse, nonspecific staining (Fig. 3B) comparable with that which occurred with control cells cultured in DMEM alone, confirming that no β chain was associated with these cells. With the PgWC antibody raised against whole P. gingivalis W50 cells, RI-treated HGF showed a staining pattern (Fig. 3C) similar to that observed with antibody 1A1, indicating that it was detecting mainly the adhesin domain of RI, whereas RIA treatment resulted in patchy staining consisting mainly of granular deposits with short linear bands (Fig. 3D) which were much less intense than those seen with RI.

FIG. 3.

HGF incubated for 1 h with TLCK-treated RI (A and C) or TLCK-treated RIA (B and D) and stained with antibody 1A1 (A and B), which recognizes only the adhesin component of RI, or PgWC antibody against whole-cell components (C and D). The nuclear staining seen in panels A and B was the result of nonspecific staining which occurred with certain batches of biotin-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Magnification, ×750; bar = 10 μm.

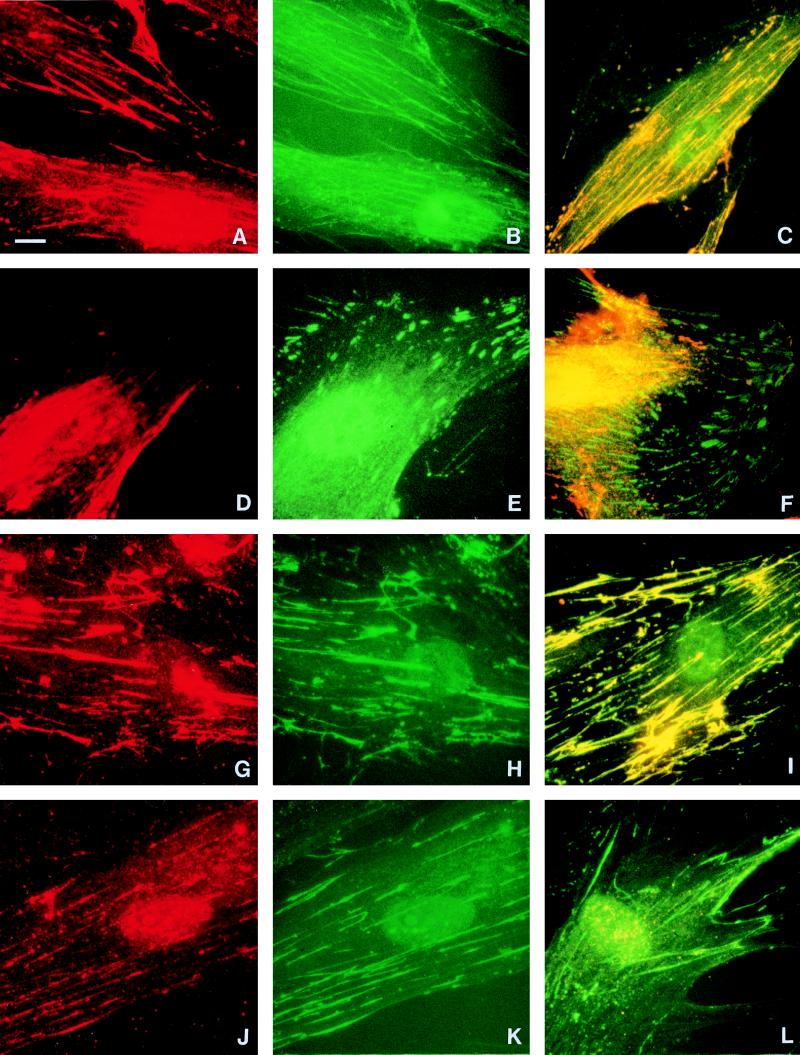

As the β component of RI is known to have sequence similarity to other microbial adhesins which bind to extracellular matrix (1), we next used double labelling to compare the localization of RI with integrin subunits α5, β1, αV, and β3 and with fibronectin, the main ligand for the α5β1 integrin receptor. HGF incubated with TLCK-treated RI and stained both with PgWC antibody to demonstrate P. gingivalis components (Fig. 4A) and with antibody against β1 integrin (Fig. 4B) demonstrated very similar linear staining patterns, and colocalization of these antibodies was confirmed by multiple exposure of the same cell stained with the two fluorescent labels (Fig. 4C). When exposed to an antibody to the αV integrin subunit, cells showed short streak-like staining generally around their periphery (Fig. 4E), which contrasted with the more central, linear distribution of P. gingivalis components (Fig. 4D). The lack of any colocalization of αV integrin and P. gingivalis components was shown by multiple exposure of the same cell (Fig. 4F). Results (not shown) similar to those illustrated in Fig. 4B and C for β1 integrin were obtained for cells stained with an antibody to α5 integrin, and results similar to those in Fig. 4E and F were obtained with a β3 integrin antibody. Double labelling with antibodies against P. gingivalis and fibronectin again indicated strikingly similar patterns (compare Fig. 4G and H), which were confirmed by multiple exposure of the same cell (Fig. 4I). In contrast, the PgWC antibody showed far less RIA bound to fibroblasts and only fine linear/granular staining (Fig. 4J). Multiple exposure of the same cell with antibodies against both P. gingivalis and fibronectin showed that the fibronectin staining predominated (Fig. 4L).

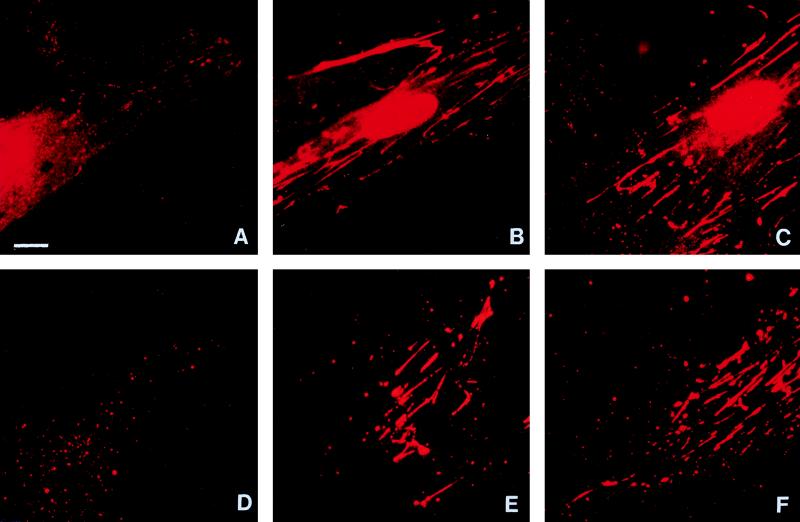

FIG. 4.

HGF incubated for 1 h with TLCK-treated RI (A to I) or TLCK-treated RIA (J to L). The first column shows cells stained with the PgWC antibody, and the second column shows the same cells double labelled with mouse antibodies against β1 integrin (B), αV integrin (E), and fibronectin (H and K). The final column shows cells multiply exposed to both labels. RI-treated cells showed a comparable linear distribution of both P. gingivalis components and β1 integrin along the cytoplasm (C), whereas the peripheral distribution of αV integrin mainly around the tips of the cell differed from the more central staining with PgWC (F). Exact colocalization of fibronectin and P. gingivalis components in RI-treated cells is indicated by the yellow, generally linear, cytoplasmic staining (I), whereas the weaker staining of P. gingivalis components in RIA-treated cells resulted in a predominantly green staining due to the fibronectin (L). Identical exposure periods were used for panels I and L. The patterns of staining with α5 and β3 integrin subunits (not shown) resembled those illustrated for β1 and αV respectively. Magnification, ×750; bar = 10 μm.

Comparative effects of RI and RIA on degradation of fibronectin in HGF cultures.

Having demonstrated the precise colocalization of TLCK-inactivated RI with fibronectin in contrast with the less intense, patchy association seen with RIA, we then compared the action of the active enzymes on degradation of the cell-associated fibronectin network. HGF cultures were incubated for 1 h with doubling dilutions of RI and RIA as already described. We observed a dose-dependent loss of fibronectin which closely followed the pattern of loss of β1 integrin staining seen in Fig. 2, with RI showing considerably greater activity than RIA at all corresponding protease activities. At 0.2 to 0.4 U of arginine-specific enzyme activity per ml, loss of fibronectin staining occurred with RI (Fig. 5A), whereas staining was clearly visible in cells treated with RIA at the same enzyme activity (Fig. 5B) and remained visible at ≥1 U/ml, although less prominent than in untreated control cultures (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

HGF stained to demonstrate fibronectin after incubation for 1 h with RI (A) or RIA (B), both at 0.2 U of arginine-specific enzyme activity per ml, compared with control cells in DMEM (C). RI-treated cells show only remnants of fine granular cytoplasmic staining and often an indistinct nucleus, in contrast with the clear fibronectin network associated with RIA-treated and control cells. Following removal of cells, the fibronectin matrix was totally disrupted after exposure to RI at 0.2 U/ml (D), whereas a clear fibronectin network was retained in the presence of a similar concentration of RIA (E) and in the DMEM control (F). Magnification, ×750; bar = 10 μm.

Degradation of cell-associated fibronectin by RI and RIA may represent a direct effect of the P. gingivalis protease on the matrix or be mediated indirectly, via action on the HGF. To investigate these possibilities, adherent cells were removed by short incubation with 0.02% EDTA before treatment of the residual fibronectin with doubling dilutions of RI and RIA for 1 h. RI caused extensive disruption of the fibronectin matrix at concentrations as low as 0.025 U/ml, with total disruption at ≥0.2 U/ml (Fig. 5D), whereas clear fibronectin trails remained in the presence of RIA at these enzyme activities (Fig. 5E) and in untreated cultures (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

This study has investigated a mechanism by which P. gingivalis might target the damaging effects of its arginine-specific enzymes within periodontal tissues. We have shown that major disruption of fibronectin-integrin interactions in HGF is due to the adhesin-mediated, targeted delivery of the catalytic domain of RI to specific sites on the cells.

Microorganisms and their products need to adhere to host cell surfaces and/or invade cells to establish an infection. Many have evolved strategies involving binding of microbial adhesins to cell receptors or extracellular matrix molecules to facilitate their interaction with the host (19). Binding to fibronectin has been extensively demonstrated by many microbial pathogens, including staphylococci, streptococci, Candida albicans, and Treponema pallidum. Other microorganisms exploit interactions with β-chain integrins leading to internalization (13). Invasin, an outer membrane protein which binds to several different β1 integrin receptors promoting uptake, has been widely studied in enteropathogenic Yersinia species. In addition, adherence of some bacteria to host tissue is mediated by fimbriae. Interestingly, the binding of P. gingivalis fimbriae to human fibroblasts and extracellular matrix components has recently been shown to be enhanced by arginine-specific protease treatment, resulting in the exposure of hidden binding sites on host tissues (15, 16).

The enhanced activity displayed by the RI heterodimer compared with the monomeric RIA with similar protease activity, which we report, indicates that the adhesin chain of RI is important in the loss of both α5 and β1 integrin subunits of HGF. The exact colocalization of RI with fibronectin and its major α5β1 receptor demonstrated in HGF cultures would provide the bacterium with a method of targeting its protease component to specific susceptible regions within the host tissue. A similar targeting mechanism may operate in P. gingivalis-mediated hemagglutination (8). However, as RIA, which contains only the protease domain, retains some ability to localize to fibronectin, the possibility that an additional recognition site exists on the catalytic α chain should be considered.

The use of TLCK-treated purified proteases has allowed their sites of action on HGF to be demonstrated in the absence of the normal proteolytic degradation. In the presence of active protease, RI caused loss of the cell-associated fibronectin network under conditions in which α5β1 integrin receptor loss was also observed. In contrast, comparable concentrations of RIA caused considerably less destruction of fibronectin and loss of the α5β1 integrin receptor. Internalization of certain integrins, including α5β1, can occur rapidly in the absence of the corresponding ligands (4) and is enhanced if the integrins are cross-linked (11). As ligand binding is known to anchor receptors at the cell surface, it is likely that the protease-mediated destruction of fibronectin that we report is the primary event which leads to the loss or lack of detection of its α5β1 receptor.

The failure of P. gingivalis to localize at sites of αV and β3 integrins (the vitronectin receptor) and the resistance of these integrins to destruction by arginine-specific proteases, even after 24 h incubation, is in contrast with the colocalization with and susceptibility of the α5β1 fibronectin receptor. As the vitronectin receptor is susceptible to destruction by P. gingivalis culture supernatant after prolonged incubation (24), this would appear to be mediated by a factor(s) other than arginine-specific proteases.

The failure to demonstrate any very significant enhancement of activity of RI or RIA on HGF integrin loss in the presence of cysteine was unexpected and contrasts with the rapid and marked increase in hydrolysis of synthetic substrates by both proteases on addition of cysteine (23). It is possible that sufficient reducing conditions exist locally to activate the protease. However, the fibronectin trails attached to the glass surface after removal of the cells with 0.02% EDTA remained susceptible to destruction by RI in the absence of cysteine. Hence, localized reducing conditions, if they exist, are clearly not cell dependent. The precise mechanisms of action of RI and RIA therefore require further investigation.

Our initial experiments which compared the β1 integrin loss with W50 and W50/BE1 culture supernatants indicated that the former is considerably more active, even when used at a comparable arginine-specific protease activity. This apparent discrepancy could be due to the existence of five biochemically distinct forms of arginine-specific proteases (RI, RIA, RIB, RIIA, and RIIB) (22). All contain the catalytic α chain and therefore contribute to the BApNA activity, but the distribution of the isoforms differs between W50 and W50/BE1 (5) and the relative effects of the different enzymes on integrins are not known. Furthermore, W50/BE1 is a pleiotropic mutant with multiple differences from the parent strain (17, 25), which could contribute to the different effects seen with the two culture supernatants.

Fibroblasts are anchorage-dependent cells, and cell attachment is required for normal growth and proliferation. Specific extracellular ligand-integrin interactions initiate intracellular signalling events which regulate the cell phenotype. Thus, any disruption of this interaction is likely to have major consequences for the cell. As well as degrading extracellular matrix components directly, P. gingivalis factors can also stimulate host cells to break down their own matrix. A proteinase from P. gingivalis culture medium has been reported to stimulate collagen degradation by cultured epithelial cells (3) via a mechanism involving activation and processing of latent host matrix metalloproteinases MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-9 (10). Degradation products of fibronectin also signalled changes in metalloproteinase gene expression in rabbit synovial fibroblasts (32). Similar mechanisms may have contributed to the degradation of cell surface and matrix glycoproteins in cultured gingival fibroblasts described by Uitto et al. (31). The specific binding of P. gingivalis adhesins to extracellular matrix proteins such as fibronectin, described here, may represent one mechanism by which this organism can target its protease and is thus likely to have a significant impact on the functioning of host cells resident in connective tissue. As the adhesin domain of P. gingivalis proteases binds to laminin and fibrinogen in addition to fibronectin (20), it is likely that the catalytic effects of the proteases are also targeted at other specific cells and tissues. These possibilities are under further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by the Medical Research Council (grant no. PG9318173).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aduse-Opoku J, Muir J, Slaney J M, Rangarajan M, Curtis M A. Characterization, genetic analysis, and expression of a protease antigen (PrpRI) of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4744–4754. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4744-4754.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkedal-Hansen H, Taylor R E, Zambon J J, Barwa P K, Neiders M E. Characterization of collagenolytic activity from strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 1988;23:258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkedal-Hansen H, Wells B R, Lin H Y, Caulfield P W, Taylor R E. Activation of keratinocyte-mediated collagen (type I) breakdown by suspected human periodontopathogen. Evidence of a novel mechanism of connective tissue breakdown. J Periodontal Res. 1984;19:645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1984.tb01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bretscher M S. Endocytosis and recycling of the fibronectin receptor in CHO cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:1341–1348. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collinson L M, Rangarajan M, Curtis M A. Altered expression and modification of proteases from an avirulent mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 (W50/BE1) Microbiology. 1998;144:2487–2496. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cridland J C, Booth V, Ashley F P, Curtis M A, Wilson R F, Shepherd P. Preliminary characterisation of antigens recognised by monoclonal antibodies raised to Porphyromonas gingivalis and by sera from patients with periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1994;19:645–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis M A. Analysis of the protease and adhesin domains of the PrpR1 of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis M A, Aduse-Opoku J, Slaney J M, Rangarajan M, Booth V, Cridland J, Shepherd P. Characterization of an adherence and antigenic determinant of the ArgI protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis which is present on multiple gene products. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2532–2539. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.7.2532-2539.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis M A, Ramakrishnan M, Slaney J M. Characterization of the trypsin-like enzymes of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 using a radiolabelled active-site-directed inhibitor. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:949–955. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-5-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeCarlo A A, Windsor L J, Bodden M K, Harber G J, Birkedal-Hansen B, Birkedal-Hansen H. Activation and novel processing of matrix metalloproteinases by a thiol-proteinase from the oral anaerobe Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1260–1270. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760060501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeStrooper B, Van Leuven F, Carmeliet G, Van den Berghe H, Cassiman J J. Cultured human fibroblasts contain a large pool of precursor β1-integrin but lack an intracellular pool of mature subunit. Eur J Biochem. 1991;199:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher H M, Schenkein H A, Morgan R M, Bailey K A, Berry C R, Macrina F L. Virulence of a Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 mutant defective in the prtH gene. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1521–1528. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1521-1528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isberg R R, Tran Van Nhieu G. Binding and internalization of microorganisms by integrin receptors. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:10–14. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodawaki T, Yoneda M, Okamoto K, Maeda K, Yamamoto K. Purification and characterization of a novel arginine-specific cysteine proteinase (argingipain) involved in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease from the culture supernatant of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21371–21378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kontani M, Kimura S, Nakagawa I, Hamada S. Adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to matrix proteins via a fimbrial cryptic receptor exposed by its own arginine-specific protease. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1179–1187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4321788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kontani M, Ono H, Shibata H, Okamura Y, Tanaka T, Fujiwara T, Kimura S, Kamada S. Cysteine protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis 381 enhances binding of fimbriae to cultured human fibroblasts and matrix proteins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:756–762. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.756-762.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh P D, McKee A S, McDermid A S, Dowsett A B. Ultrastructure and enzyme activities of a virulent and an avirulent variant of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;59:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKee A S, McDermid A S, Wait R, Baskerville A, Marsh P D. Isolation of colonial variants of Bacteroides gingivalis W50 with a reduced virulence. J Med Microbiol. 1988;27:59–64. doi: 10.1099/00222615-27-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patti J M, Allen B L, McGavin M J, Höök M. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissues. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:585–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pike R N, Potempa J, McGraw W, Coetzer T H T, Travis J. Characterization of the binding activities of proteinase-adhesin complexes from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2876–2882. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2876-2882.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potempa J, Pike R, Travis J. The multiple forms of trypsin-like activity present in various strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis are due to the presence of either Arg-gingipain or Lys-gingipain. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1176–1182. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1176-1182.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rangarajan M, Aduse-Opoku J, Slaney J M, Young K A, Curtis M A. The prpR1 and prR2 arginine-specific protease genes of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 produce five biochemically distinct enzymes. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:955–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2831647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rangarajan M, Smith S J M, U S, Curtis M A. Biochemical characterization of the arginine-specific proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 suggests a common precursor. Biochem J. 1997;323:701–709. doi: 10.1042/bj3230701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scragg M A, Cannon S J, Williams D M. The secreted products of Porphyromonas gingivalis alter human gingival fibroblast morphology by selective damage to integrin-substrate interactions. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1996;9:167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah H N, Seddon S V, Gharbia S E. Studies on the virulence properties and metabolism of pleiotropic mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis (Bacteroides gingivalis) W50. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slots J, Listgarten M A. Bacteroides gingivalis, Bacteroides intermedius and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smalley J W, Birss A J, Shuttleworth C A. The degradation of type I collagen and human plasma fibronectin by the trypsin-like enzyme and extracellular membrane vesicles of Bacteroides gingivalis W50. Arch Oral Biol. 1988;33:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(88)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorsa T, Ingman T, Suomalainen K, Haapasalo M, Konttinen Y T, Lindy O, Saari H, Uitto V-J. Identification of proteases from periodontopathogenic bacteria as activators of latent human neutrophil and fibroblast-type interstitial collagenases. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4491–4495. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4491-4495.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travis J, Pike R, Imamura T, Potempa J. Porphyromonas gingivalis proteinases as virulence factors in the development of periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uitto V-J, Haapasalo M, Laasko T, Salo T. Degradation of basement membrane collagen by proteases from some anaerobic oral micro-organisms. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1988;3:97–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1988.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uitto V-J, Larjava H, Heino J, Sorsa T. A protease of Bacteroides gingivalis degrades cell surface and matrix glycoproteins of cultured gingival fibroblasts and induces secretion of collagenase and plasminogen activator. Infect Immun. 1989;57:213–218. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.213-218.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werb Z, Tremble P M, Behrendtsen O, Crowley E, Damsky C H. Signal transduction through the fibronectin receptor induces collagenase and stromelysin gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:877–889. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Winkelhoff A J, Van Steenbergen T J M, de Graaff J. The role of black-pigmented Bacteroides in human oral infections. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15:145–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]