Abstract

The majority of type III group B streptococcus (GBS) human neonatal infections are caused by a genetically related subgroup called III-3. We have proposed that a bacterial enzyme, C5a-ase, contributes to the pathogenesis of neonatal infections with GBS by rapidly inactivating C5a, a potent pro-inflammatory molecule, but many III-3 strains do not express C5a-ase. The amount of C5a produced in serum following incubation with representative type III strains was quantitated in order to better understand the relationship between C5a production and C5a-ase expression. C5a production following incubation of bacteria with serum depleted of antibody to the bacterial surface was inversely proportional to the sialic acid content of the bacterial capsule, with the more heavily sialylated III-3 strains generating less C5a than the less-virulent, less-sialylated III-2 strains. The amount of C5a produced correlated significantly with C3 deposition on each bacterial strain. Repletion with type-specific antibody caused increased C3b deposition and C5a production through alternative pathway activation, but C5a was functionally inactivated by strains that expressed C5a-ase. The increased virulence of III-3 strains compared to that of III-2 strains results at least partially from the higher sialic acid content of III-3 strains, which inhibits both opsonophagocytic killing and C5a production in the absence of type-specific antibody. We propose that C5a-ase is not necessary for III-3 strains to cause invasive disease because the high sialic acid content of III-3 strains inhibits C5a production.

Group B streptococci (GBS) are an important cause of serious bacterial disease in neonates, pregnant women, and adults with underlying illnesses (2). GBS are subclassified into serotypes according to the immunologic reactivity of the polysaccharide capsule. Of the nine serotypes, types I, II, III, and more recently, types V and VIII GBS cause the majority of neonatal human GBS disease (2, 4, 12). Serotype III GBS are particularly important because type III GBS cause a significant percentage of early-onset disease (within the first week of life) and the majority of late-onset disease (after the first week of life) in human neonates and also cause the vast majority of neonatal GBS meningitis cases (2).

We previously showed that serotype III GBS can be subclassified by computer-assisted numerical analysis of restriction digest patterns (RDPs) of chromosomal DNA (14). In a more recent study, we showed that serotype III GBS isolated from Tokyo, Japan, and Salt Lake City, Utah, can be classified into three major RDP types, III-1, III-2, and III-3, according to the similarity of the HindIII RDPs (16). The III-2 and III-3 strains can be further subdivided into III-2a and III-2b and III-3a and III-3b, respectively, based on the similarity of the Sse83871 RDPs. The overwhelming majority (91%) of invasive isolates obtained from neonates in that study were III-3 (III-3a or III-3b), whereas only 33% of vaginal isolates were III-3, thereby implying that III-3 strains are more invasive than the other RDP types (16).

The reason for the increased pathogenicity of the III-3 strains is not understood. Resistance to opsonization by complement is the major bacterial virulence factor that has been identified to contribute to invasive GBS disease in human neonates. Resistance of serotype III GBS to opsonophagocytosis is proportional to the sialic acid content of the capsular polysaccharide, since removal of sialic acid by treatment with neuraminidase, or by transposon-insertional mutagenesis, increases deposition of opsonic C3 fragments (C3b and C3bi) by allowing activation of the alternative pathway of complement (8, 13). The mean capsular sialic content of III-3 strains is significantly higher than that of either III-2 or III-1 strains, suggesting that increased virulence of III-3 strains is at least partly due to the high sialic acid content of their capsules (16).

We previously proposed that the bacterial enzyme C5a-ase contributes to the pathogenicity of GBS by the ability of C5a-ase to rapidly inactivate the potent complement-derived polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) agonist C5a (5, 11), thereby reducing PMN recruitment to sites of inflammation (6) and C5a-mediated stimulation of PMN phagocytosis (17). We therefore expected that invasive type III GBS would uniformly express C5a-ase. Indeed, 96% of III-3a strains express C5a-ase, but none of the III-3b strains express C5a-ase, despite the fact that III-3b strains cause a significant proportion of type III GBS invasive disease. These results suggest that C5a-ase is not critical for all III-3 strains to be invasive.

One hypothesis to explain the lack of C5a-ase expression by III-3b strains is that the higher sialic acid content of III-3 strains sufficiently limits C5a production by the alternative pathway so that C5a-ase is superfluous. While the effects of sialic acid on C3 deposition and opsonophagocytic killing in the presence of serum complement have been extensively characterized in type III GBS, the effect of sialic acid on the production of C5a following activation of complement by type III GBS has not been investigated. In these studies, we therefore examined the production of C5a in serum incubated with type III GBS, in the absence or presence of type-specific antibody, and compared C5a production to C3b deposition and opsonophagocytic killing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

GBS isolates used in this study have been previously characterized (16) and are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were cultured overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; BBL, Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) and then inoculated at a 1:20 dilution into fresh THB and incubated at 37°C for 90 min. Bacteria were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and resuspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) containing 0.4% human serum albumin (HSA; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and 10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethnesulfonic acid (HEPES, Gibco) to an optical density of 0.6 at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600 = 0.6). In some experiments, the harvested bacteria were treated with 5% formalin in PBS at 37°C for 30 min with shaking and then washed five times with PBS. One milliliter of an OD600 = 0.6 suspension contains 169 μg of cells (dry weight) and between 0.4 × 108 and 1.8 × 108 CFU (17).

TABLE 1.

Serotype III strains used in these studies

| RDP type | Straina | C5a-ase activity | Sialic acid contentb |

|---|---|---|---|

| III-3b | 37 | − | 5.1 |

| 32 | − | 4.4 | |

| 34 | − | 8.2 | |

| III-3a | 23 | + | 5.6 |

| 3 | + | 7.7 | |

| 21 | + | 6.5 | |

| III-2 | 51 | + | 2.6 |

| 45 | + | 2.7 | |

| 52 | + | 3.9 |

Strain number used previously (16).

Expressed as micrograms per milligram of cells (dry weight).

Type III-specific MAb.

Murine monoclonal antibody (MAb) SIIIS8 directed against the fully sialated type III capsular polysaccharide (10) was purified from ascites by octanoic acid precipitation (15).

Preparation of absorbed serum.

Serum (5 ml) was collected from a healthy donor and absorbed for 30 min on ice with a bacterial pellet harvested from 50 ml of an OD600 = 0.6 suspension of the isolate to be studied in order to remove antibodies directed against surface antigens. The absorption was performed three successive times, and the bacteria were removed by centrifugation following each absorption. In some experiments, absorbed sera were dialyzed five times against PBS to remove Mg++ and Ca++ for experiments designed to determine which complement pathway contributes to C5a production. The absorbed sera were filter sterilized and stored at −80°C. Antibody to type III capsule after absorption of the sera was undetectable (<0.2 μg/ml), as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The total hemolytic complement activities (CH50) of the absorbed sera and the dialyzed sera (following repletion with Mg++ and Ca++) were equal to that of untreated serum.

Preparation of PMNs.

PMNs were purified from heparinized blood of healthy adult donors by density gradient centrifugation with Polymorphprep (Nycomed Pahrm As, Torshov, Norway) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PMNs were kept in suspension at room temperature for at least 60 min on a rolling mixer (RM-810; Sysmex, Tokyo, Japan) to downregulate the number and function of PMN CR3, an adhesive receptor critical for ingestion of GBS (9). This procedure was essential for reproducible results, particularly in the PMN adherence assay described below. PMN viability was greater than 95% as assessed by dye exclusion.

Activation of serum complement and opsonization of GBS.

Activation of serum complement and opsonization of the bacteria were performed by mixing 500 μl of a bacterial suspension (OD600 = 0.6) with 100 μl of absorbed serum with various concentrations (0, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128 μg/ml) of anti-type III MAb in HBSS-HSA-HEPES (total volume, 1 ml) at 37°C for 30 min. At the end of the incubation, the bacteria were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatants were filter sterilized and stored at −80°C. The bacterial pellets were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in HBSS-HSA-HEPES, and used in assays to determine the amount of C3 deposition. Opsonization was performed in the same manner except that 4 mM Mg++–16 mM EGTA was added to the reaction mixture to determine the role of the alternative pathway in C3 deposition. Dialyzed serum repleted with 1 mM Mg++ or with 1 mM Mg++ and 1 mM Ca++ was used to determine whether the classical or alternative pathway is involved in C5a production. Zymosan-activated serum (ZAS) was prepared by mixing 1 ml of serum with 1 mg of washed zymosan (Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min.

C3 deposition on GBS.

Total C3 deposition (C3b, C3bi, and C3d) on bacteria was measured by comparing the binding of a 125I-labelled anti-C3d MAb that binds to C3b, C3bi, and C3d (Quidel, La Jolla, Calif.) to each bacterial strain with that of its binding to a standard strain (strain 51) prepared daily. Bacteria were opsonized as described above, and unopsonized control bacteria were prepared by incorporating 4 mM EDTA (final concentration) into the reaction mixture. Serial dilutions of the opsonized cell suspensions were prepared by diluting the bacteria in unopsonized cells of the same strain in a volume of 200 μl, and the bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation and washed twice with HBSS. To facilitate recovery of the bacteria, 800 μl of a carrier bacteria cell suspension with an OD600 = 2.4 (a heat-killed, asialo strain of GBS) was added to 200 μl each of opsonized and unopsonized bacterial suspensions. After being washed with HBSS, the bacteria were resuspended in 500 μl of HBSS containing 0.4% HSA to which 500 μl of 125I-labelled anti-C3d MAb at a concentration of 125 ng/ml was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min with shaking, the bacteria were washed twice with HBSS, and the radioactivity in the pellet was counted in a gamma counter. The specific binding of radioactive 125I-labelled anti-C3d was calculated by the following formula: specific binding = counts per minute of the opsonized cells diluted with unopsonized cells − counts per minute of the pellet from the unopsonized bacteria. The counts per minute of the unopsonized bacteria were always less than 10% of the total counts per minute recovered from the opsonized strains. A plot of the specifically bound 125I-labelled anti-C3d versus the volume of opsonized cells was prepared for the standard strain. C3 deposition on each strain was derived from the standard curve and expressed as a percentage of the C3 deposited on the standard strain. Preliminary experiments on 5 separate days to determine the reproducibility of the assay yielded a coefficient of variation of <10 for specific binding of the 125I-labelled anti-C3d to the standard strains.

C5a production.

Functional C5a activity in the serum activated by bacteria was determined by using a modification of a previously described quantitative PMN adherence assay (5). The activated serum was serially diluted in HBSS-HSA-HEPES, and 25 μl of the diluted serum was added to 175 μl of purified PMNs at a concentration of 5.7 × 106 cells/ml in HBSS-HSA-HEPES. PMNs were also incubated in separate wells with 25 μl of 4% ZAS as a 100% control or 25 μl of HBSS-HSA-HEPES as an unstimulated control. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 8 min in gelatin-coated 16-mm-diameter tissue culture wells, and then nonadherent PMNs were removed with a pipette and residual nonadherent PMNs in the wells were removed by rinsing with 200 μl of HBSS-HSA-HEPES. The total nonadherent PMNs were pooled and counted in an automated cell counter (F-500; Sysmex). A PMN adherence ratio for each well was calculated as follows: (number of nonadherent PMS of unstimulated control − number of nonadherent PMNs stimulated by the activated serum)/(number of nonadherent PMNs of the unstimulated control − number of nonadherent PMNs of the 100% control). A z value was calculated as follows: z = adherence ratio/(1-adherence ratio). An equation for the regression line between the log of the concentrations of the activated serum and the log of z for each concentration was derived. The concentration of activated serum was determined from the equation for the regression line where 50% of the PMNs were adherent, that is, where the log of z = 0. The functional C5a activity in the activated serum was expressed as PA50 units per milliliter: 1 PA50 unit stimulates adherence of 50% of the PMNs added to a gelatin-coated well at 37°C after 8 min. Preliminary experiments to determine the reproducibility of the assay yielded a coefficient of variation of <10 for the PA50 of ZAS. No C5a activity (less than 200 U/ml) was measured in dialyzed serum that was activated with zymosan, while the PA50 of dialyzed serum that was repleted with Mg++ and then activated with zymosan was found to be the same as that of untreated serum.

Sialic acid content.

The cell wall sialic acid was extracted from the pellet (harvested from 20 ml of an OD600 = 0.6 suspension) by hydrolysis with 0.1 N HCl at 84°C for 20 min, and the sialic acid content of the extract was determined by the thiobarbituric acid method with N-acetylneuraminic acid as the standard (1).

RESULTS

Detection of functional C5a activity following complement activation by GBS expressing C5a-ase.

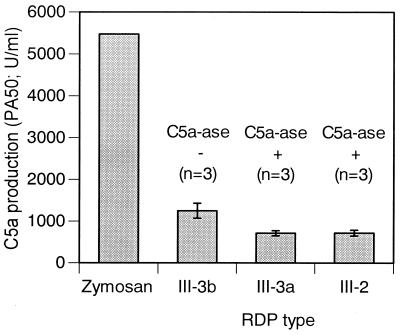

Preliminary experiments were performed to determine if functional C5a activity could be detected following incubation of selected type III strains with absorbed serum. As shown in Fig. 1, the mean functional C5a activity was significantly greater in serum incubated with C5a-ase-negative III-3b strains than in serum incubated with C5a-ase-positive III-3a or III-2 strains, although the amount of C5a activity produced after incubation with the bacteria was significantly less than that observed in serum incubated with zymosan, a potent activator of serum complement. These data indicate that functional C5a produced following activation of complement by the bacteria is, as expected, rapidly inactivated by bacterial C5a-ase, which makes it impossible to assess functional C5a production under these conditions.

FIG. 1.

C5a production of GBS by RDP types and zymosan in serum absorbed with the homologous strain. The data are means ± standard deviations. There were statistically significant differences (P < 0.01) between III-3b and each of III-3a, III-2, and zymosan as calculated by the Student’s t test.

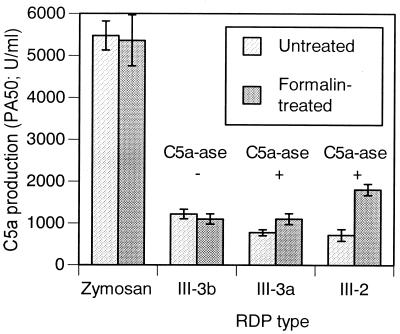

Representative C5a-ase-positive and C5a-ase-negative strains of GBS were treated with formalin in an effort to inactivate GBS C5a-ase activity and then tested for their ability to activate serum complement and produce functional C5a activity. As shown in Fig. 2, formalin treatment resulted in a significantly greater amount of functional C5a activity in the III-2 and III-3a C5a-ase-positive strains. In contrast, formalin treatment did not affect production of functional C5a activity following complement activation by the C5a-ase-negative strain, nor did formalin treatment of zymosan affect functional C5a activity produced following zymosan activation of complement. These data indicate that formalin-treatment inactivated C5a-ase without affecting complement activation by the bacterial surface. Subsequent experiments to correlate C5a production with sialic acid content in type III strains were performed with formalin-treated GBS.

FIG. 2.

C5a production following incubation of formalin-treated and untreated GBS strain 37 (III-3b), 23 (III-3a), and 51 (III-2) and zymosan with serum absorbed with each of the homologous strains. The data are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations. There were statistically significant differences between formalin-treated cells and untreated cells for III-3a (P < 0.05) and for III-2 (P < 0.01) as calculated by the Student’s t test.

Correlation of C5a production and C3b deposition with sialic acid content on type III GBS.

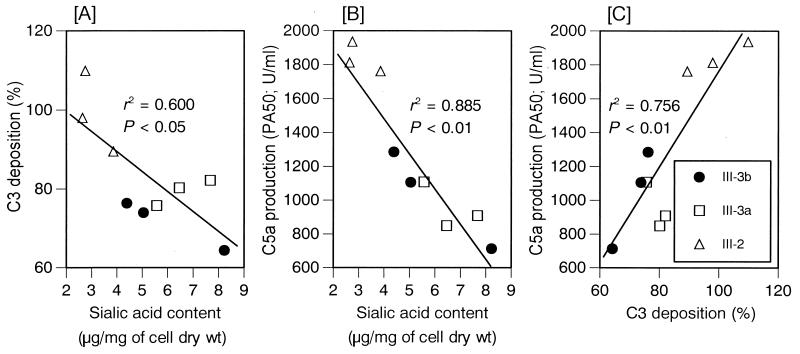

As shown in Fig. 3A and B, both C3b deposition on the bacterial surface and C5a production in serum depleted of antibody to the bacterial surface were significantly correlated with the sialic acid content of the individual strains tested. In addition, there was a significant correlation between C3 deposition and C5a production for each strain tested (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that the more heavily sialylated III-3 strains activate less complement than the less heavily sialylated III-2 strains when anticapsular antibody is absent.

FIG. 3.

Correlations between sialic acid and C3 deposition (A), sialic acid and C5a production (B), and C3 deposition and C5a production (C) of GBS in serum absorbed with each of the homologous strains. C5a production was determined on formalin-treated GBS. The data are means of triplicate determinations. The r2 and P values were calculated by linear regression analysis.

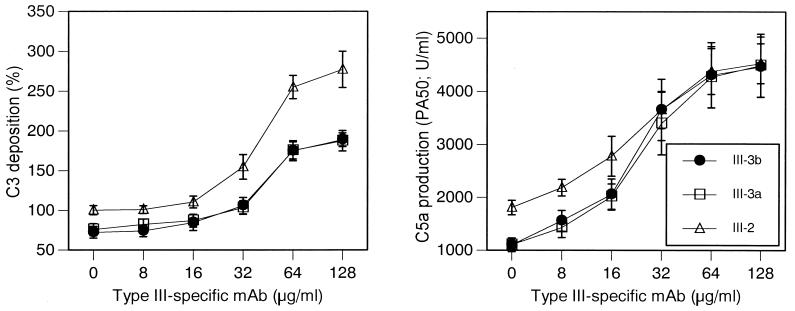

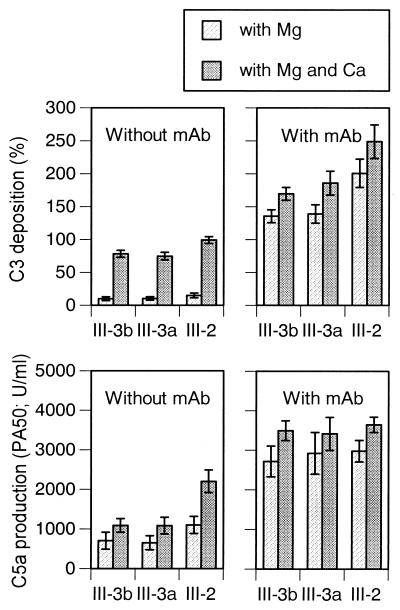

Addition of anti-type III MAb to the absorbed serum resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in C3 deposition and C5a production of representative strains from each of the subtypes (Fig. 4). C3 deposition and C5a production opsonophagocytic killing were significantly lower for the III-3 strains than for the III-2 strain at a MAb concentration of <32 μg/ml, whereas optimal C3 deposition and C5a production occurred at MAb concentrations of >32 μg/ml for all three strains. C5a production in the presence of the highest concentrations of antibody approximated that detected after activation of serum with zymosan. Low, almost undetectable levels (<800 U/ml) of functional C5a were measured when non-formalin-treated C5a-ase-positive GBS were incubated with serum even in the presence of the highest concentrations of MAb (data not shown), demonstrating the ability of C5a-ase to completely destroy functional C5a activity even under conditions optimal for complement activation.

FIG. 4.

C3 deposition and C5a production and opsonophagocytic killing of GBS strain 37 (III-3b), 23 (III-3a), and 51 (III-2) in absorbed serum to which various concentrations of type III-specific MAb have been added. C5a production was determined on formalin-treated GBS. The data are means ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations. There were statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Student’s t test) between III-2 and either III-3b or III-3a at any concentration of MAb for C3 deposition and at 0, 8, and 16 μg/ml of MAb (C5a production and bacterial survival).

Contributions of classical and alternative pathways.

Activation of complement was carried out in the presence of Ca++ and Mg++ or of Mg++ alone in order to determine the contribution of the classical and alternative pathways to C3 deposition and C5a production in the absence of type-specific antibody or in the presence of optimal concentrations of anti-III MAb. As shown in Fig. 5, C3 deposition and C5a production was largely classical pathway dependent in the absence of specific antibody but were largely alternative pathway dependent in the presence of optimal concentrations of type-specific MAb.

FIG. 5.

The roles of the classical and alternative pathways of complement activation in C3 deposition and C5a production of GBS strain 37 (III-3b), 23 (III-3a), and 51 (III-2) by using absorbed serum with or without anti-type III MAb (128 μg/ml). C5a production was determined on formalin-treated GBS. The data are means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations.

DISCUSSION

The results of these experiments demonstrate that activation of serum complement by type III GBS in the absence of type-specific antibody, as measured by C5a production and deposition of opsonically active fragents of C3, is inversely proportional to the capsular sialic acid content of the bacteria. Although a correlation between C3 deposition and sialic acid content has been demonstrated previously (13), this is the first report demonstrating a correlation between capsular sialic acid content and C5a production when GBS are exposed to serum complement.

The results of these experiments demonstrate that activation of the C5 convertase by type III GBS in antibody-depleted serum proceeds largely through the classical pathway. These results are consistent with previously published results showing that opsonophagocytic killing (which requires complement activation) is largely classical pathway dependent in sera that contain low concentrations of type III-specific antibody (8). The dependence on the classical pathway under these circumstances is probably due to inhibition of the alternative pathway C5 convertase, C3bBb3b, by capsular sialic acid. The mechanism by which the classical pathway is activated by type III GBS in antibody-depleted serum is not known but could result from the presence of tiny amounts of residual antibody or from direct activation of C1 by the bacterial surface, as proposed for type Ia GBS (3).

Repletion of the absorbed serum with type-specific antibody results in a large increase in alternative pathway complement activation. Again, this result is consistent with that reported by Edwards et al., who showed that type-specific antibody causes opsonophagocytic killing of type III GBS by activation of the alternative pathway of complement (8). Type III GBS that have been made sialic acid deficient by neuraminidase treatment or transposon-insertional mutagenesis also activate the alternative pathway (8, 13). Thus, the probable mechanism by which antibody binding to capsular polysaccharide activates the alternative pathway is by reducing the ability of sialic acid to inhibit the alternative pathway convertase, thereby rendering the GBS functionally similar to sialic-acid-deficient GBS. It is not known why type-specific antibody activates the alternative pathway preferentially over the classical pathway, nor is it known whether the classical pathway could compensate if the alternative pathway was not available.

We previously hypothesized that GBS C5a-ase contributes to the pathogenesis of GBS infections. We have shown that GBS C5a-ase rapidly inactivates C5a in vitro (5, 11) and have published evidence that GBS C5a-ase can reduce PMN recruitment to experimental type III GBS infection in vivo (6). We have also presented evidence that C5a-ase can contribute to the pathogenesis of GBS infections by reducing the stimulatory effect of C5a on the opsonophagocytic killing of type III GBS (17). Our finding that virulent III-3b organisms do not express C5a-ase seemed to refute the hypothesis that C5a-ase is an important GBS virulence factor, but data presented here suggest that C5a-ase is not necessary for infection with type III-3b strains because the sialic acid content of the III-3b strains sufficiently limits C5a production in serum when type-specific antibody is absent. C5a-ase may nonetheless contribute to the pathogenesis of some infections caused by some type III GBS, for instance, when less heavily sialylated GBS directly activate complement or when complement activation occurs because of low levels of type-specific antibody (Fig. 4). C5a-ase may also contribute to the pathogenesis of GBS infections caused by other serotypes. In a recent study, all type I and type II strains causing invasive disease were found to express C5a-ase (7), suggesting the hypothesis that C5a-ase expression is more important for infections with these serotypes, perhaps because type I and type II GBS activate the classical and/or alternative complement pathways more efficiently than do type III organisms. This hypothesis is currently under investigation in our laboratories.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-40918 and AI-13150 from the National Institutes of Health and by a grant from the Primary Children’s Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aminoff D. Methods for the quantitative estimation of N-acetylneuraminic acid and their application to hydrolysates of sialomucoids. Biochem J. 1961;81:384–392. doi: 10.1042/bj0810384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker C J, Edwards M S. Group B streptococcal infections. In: Remington J S, Klein J O, editors. Infectious disease of the fetus and newborn infant. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1995. pp. 980–1054. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker C J, Edwards M S, Webb B J, Kasper D J. Antibody-dependent classical pathway-mediated opsonophagocytosis of type Ia, group B Streptococcus. J Clin Investig. 1982;69:394–404. doi: 10.1172/JCI110463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg H M, Stephens D S, Modansky M, Erwin M, Elliot J, Facklam R R, Schuchat A, Baughman W, Farley M M. Invasive group B streptococcal disease: the emergence of serotype V. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:365–373. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohnsack J F, Mollison K W, Buko A M, Ashworth J W, Hill H R. Group B streptococci inactivate complement component C5a by enzymic cleavage at the C-terminus. Biochem J. 1991;273:635–640. doi: 10.1042/bj2730635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohnsack J F, Widjaja K, Ghazizadeh S, Rubens C E, Hillyard D, Parker C J, Albertine K H, Hill H R. A role for C5 in the acute neutrophil response to group B streptococcal infections. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:847–855. doi: 10.1086/513981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briesacher M R, Daly J A, Carroll K C, Hill H R, Bohnsack J F. Frequency of expression of C5a-ase in human isolates of group B streptococcus. Pediatr Res. 1995;37:288A. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards M S, Kasper D L, Jennings H J, Baker C J, Nicholson-Weller A. Capsular sialic acid prevents activation of the alternative pathway by type III, group B streptococci. J Immunol. 1982;128:1278–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards M S, Wessels M R, Baker C J. Capsular polysaccharide regulates neutrophil complement receptor interactions with type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2866–2871. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2866-2871.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan M L, Pritchard D G, Dillon H C, Jr, Gray B M. Protection of mice from experimental infection with type III group B streptococcus using monoclonal antibodies. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1006–1011. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.3.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill H R, Bohnsack J F, Morris E Z, Augustine N H, Parker C J, Cleary P P, Wu J T. Group B streptococci inhibit the chemotactic activity of the fifth component of complement. J Immunol. 1988;141:3551–3556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogan G, Uhrin D, Brisson J-R, Paoletti L C, Blodgett A E, Kasper D L, Jennings H J. Structural and immunochemical characterization of the type VIII group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8786–8790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marques M B, Kasper D L, Pangburn M K, Wessels M R. Prevention of C3 deposition by capsular polysaccharide is a virulence mechanism of type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3986–3993. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.3986-3993.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagano Y, Nagano N, Takahashi S, Murono K, Fujita K, Taguchi F, Okuwaki Y. Restriction endonuclease digest patterns of chromosomal DNA from group B β-haemolytic streptococci. J Med Microbiol. 1991;35:297–303. doi: 10.1099/00222615-35-5-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinbuch M, Audran R. The isolation of IgG from mammalian sera with the aid of caprylic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;134:279–284. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi S, Adderson E E, Nagano Y, Nagano N, Briesacher M R, Bohnsack J F. Identification of a highly encapsulated genetically related group of invasive type III GBS. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1116–1119. doi: 10.1086/517408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi S, Nagano Y, Nagano N, Hayashi O, Taguchi F, Okuwaki Y. Role of C5a-ase in group B streptococcal resistance to opsonophagocytic killing. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4764–4769. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4764-4769.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]