Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most frequent microbe causing middle ear infection. The pathophysiology of pneumococcal otitis media has been characterized by measurement of local inflammatory mediators such as inflammatory cells, lysozyme, oxidative metabolic products, and inflammatory cytokines. The role of cytokines in bacterial infection has been elucidated with animal models, and interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are recognized as being important local mediators in acute inflammation. We characterized middle ear inflammatory responses in the chinchilla otitis media model after injecting a very small number of viable pneumococci into the middle ear, similar to the natural course of infection. Middle ear fluid (MEF) concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were measured by using anti-human cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reagents. IL-1β showed the earliest peak, at 6 h after inoculation, whereas IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α concentrations were increasing 72 h after pneumococcal inoculation. IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α but not IL-1β concentrations correlated significantly with total inflammatory cell numbers in MEF, and all four cytokines correlated significantly with MEF neutrophil concentration. Several intercytokine correlations were significant. Cytokines, therefore, participate in the early middle ear inflammatory response to S. pneumoniae.

The natural history of local inflammatory responses in middle ear infection has been investigated with animal otitis media models infected with clinically important bacterial species. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most prevalent middle ear bacterial pathogen, cultured from approximately 40% of middle ear fluid (MEF) samples from children with acute otitis media (AOM) (2, 9) and 7% of MEF samples from children with chronic otitis media with effusion (OME) (2). We have studied the pathophysiology of pneumococcal AOM using the chinchilla otitis media model (18, 19, 23, 28, 29) and in the guinea pig model otitis media model induced by Haemophilus influenzae (17, 24, 25) and Moraxella catarrhalis (27). Inflammatory cells, lysozyme, and oxidative metabolic products have been recognized as being important contributors to acute middle ear inflammation.

The presence of cytokines in MEF samples obtained from children with OME has been reported (5, 11, 16, 21, 22, 30, 32–34), and similar observations have been reported for otitis media animal models (1, 7, 14, 15). We recently observed that interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were present in MEF during type 3 S. pneumoniae-induced experimental otitis media in the chinchilla model; commercially available human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reagents were used (28). We, therefore, sought to investigate the natural course of cytokines and their interaction with inflammatory cells during the early stage of middle ear inflammation in the chinchilla pneumococcal otitis media model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 28 healthy adult chinchillas weighing 400 to 600 g with normal middle ears, ascertained by otoscopy and tympanometry, were used. Eustachian tube obstruction was performed 24 h before inoculation to prevent the inoculum from flowing out of the Eustachian tube (3). All procedures were performed on ketamine hydrochloride-anesthetized animals. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the Animal Welfare Act (Public Law 89-144 as amended). The animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota. A type 3 S. pneumoniae strain (kindly provided by James C. Paton, Department of Microbiology, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, North Adelaide, Australia) was used. The pneumococcal strain was prepared for inoculation as previously described (28). One milliliter of the prepared 4-h log-phase pneumococcal inoculum containing approximately 40 CFU was placed directly into both middle ear hypotympanic bullae of the chinchillas (23).

MEF (200 μl) was sampled 1 (6 ears), 2 (16 ears), 4 (16 ears), 6 (16 ears), 12 (36 ears), 24 (36 ears), 48 (36 ears), and 72 h (32 ears) after pneumococcal inoculation. The same ear was tapped on two to four successive occasions. Quantitative MEF cultures were performed on sheep blood agar for the MEF sampled between 12 and 72 h; the quantitation threshold was 50 CFU/ml. Inflammatory cells in MEF samples were enumerated with a hemocytometer, and differential cell enumeration was performed with Wright’s staining (Diff Quick; American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, Ill.).

All the MEF samples were centrifuged at 500 × g and frozen at −70°C for batched cytokine assays. Concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in MEF were measured with high-sensitivity human IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α ELISA kits (Quantikine; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). MEF with undetectable cytokine was assigned a value of one-half of the detection threshold of the respective ELISA kits.

Bacterial concentration (CFU/ml), inflammatory cell numbers (cells/mm3), and cytokine concentrations (pg/ml) in MEF were determined. The values were log transformed, and correlations between inflammatory cell numbers and individual cytokine concentrations and between the individual cytokines were analyzed by Pearson’s product moment method.

RESULTS

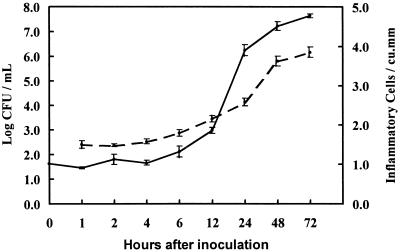

All MEF samples were culture positive for type 3 pneumococci. The MEF concentration of the log-phase inoculum did not change during the first 4 h after middle ear inoculation, but the concentration increased exponentially between 6 and 72 h to a geometric mean (GM) of 7.634 log10 CFU/ml at 72 h (Fig. 1). Blood cultures were not obtained in this study, although prior experience with this serotype in the chinchilla model (28) has shown the virtual absence of bacteremia during the first 72 h after middle ear inoculation.

FIG. 1.

Log10 mean pneumococcal CFU per milliliter (solid line, left axis) and log10 mean number of total inflammatory cells per millimeter3 (broken line, right axis) in MEF after pneumococcal inoculation. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Inflammatory cell concentration in MEF remained constant (GM, 31 to 38 cells/mm3) between 1 and 4 h after inoculation, followed by an increase to 7,099 cells/mm3 at 72 h, paralleling the exponential increase in pneumococci (Fig. 1). Neutrophils predominated (GM, 59 to 75%) among inflammatory cells in MEF, followed by macrophages (22 to 38%) and lymphocytes (2 to 3%) between 12 and 72 h. The percentage of neutrophils increased over the period from 12 (GM, 59%) to 72 h (GM, 75%), while that of macrophages decreased (GM, 38 to 22%, respectively).

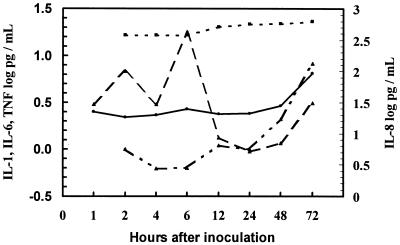

IL-1β was detectable in 50 to 100% of MEF samples between 1 and 6 h and in 16 to 47% of samples between 12 and 72 h (Table 1). The concentration peaked at 6 h (GM, 17.96 pg/ml) and then declined and appeared to have a secondary increase at 72 h (Fig. 2). TNF-α was detected in fewer than 15% of samples between 1 and 48 h and in 40% of samples at 72 h, when the GM concentration was 6.51 pg/ml. IL-6 was detected in 31 to 50% of samples between 2 and 24 h and in 88 to 97% of samples between 48 and 72 h, when the GM concentration reached 8.29 pg/ml. IL-8 was detected in no samples before 12 h and was detected in 25 to 38% of samples between 12 and 72 h, when the GM concentration reached 622.57 pg/ml. The later increases of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were all temporally associated with the increase of inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils.

TABLE 1.

Cytokine concentration (pg/ml) in MEF

| Cytokine and parametersa | Parametric value at indicated hours after inoculation

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |

| IL-1β | ||||||||

| GM | 3.02 | 6.82 | 3.05 | 17.96 | 1.33 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 3.11 |

| Geo max | 28.82 | 35.32 | 50.19 | 42.18 | 19.00 | 24.53 | 74.10 | 334.12 |

| Geo min | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 5.45 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| n | 6 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 35 | 32 | 33 | 30 |

| % Detectable | 50 | 93 | 67 | 100 | 31 | 16 | 24 | 47 |

| 1/2 detection | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| TNF-α | ||||||||

| GM | 2.50 | 2.20 | 2.32 | 2.67 | 2.38 | 2.24 | 2.90 | 6.51 |

| Geo max | 5.23 | 10.17 | 2.50 | 20.43 | 612.28 | |||

| Geo min | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.50 | |||

| n | 6 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 30 |

| % Detectable | 0 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 40 |

| 1/2 detection | 2.50 | 2.20 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 |

| IL-6 | ||||||||

| GM | 0.99 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 2.10 | 8.29 | |

| Geo max | 6.40 | 0.68 | 18.79 | 4.62 | 10.40 | 113.27 | ||

| Geo min | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.62 | ||

| n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 30 | |

| % Detectable | 50 | 0 | 13 | 35 | 31 | 88 | 97 | |

| 1/2 detection | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | |

| IL-8 | ||||||||

| GM | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 510.12 | 561.88 | 574.66 | 622.57 | |

| Geo max | 993.32 | 1,812.65 | 1,721.48 | 1,630.33 | ||||

| Geo min | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | ||||

| n | 8 | 8 | 8 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 29 | |

| % Detectable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 25 | 32 | 38 | |

| 1/2 detection | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | 375.00 | |

Max, maximum concentration; min, minimum concentration, 1/2 detection, value (pg/ml) of one-half of the detection threshold.

FIG. 2.

GM concentration of cytokines in MEF after pneumococcal inoculation. IL-1β, broken line; IL-6, broken-dotted line; IL-8, dotted line; TNF-α, solid line.

Total inflammatory cell concentration in MEF correlated significantly with IL-6 (r = 0.580, P < 0.001), IL-8 (r = 0.256, P = 0.009), and TNF-α (r = 0.486, P < 0.001) but not with IL-1β (r = 0.022, P = 0.807) concentrations. Neutrophil concentration correlated significantly with IL-1β (r = 0.327, P = 0.001), IL-6 (r = 0.587, P < 0.001), IL-8 (r = 0.259, P = 0.008), and TNF-α (r = 0.565, P < 0.001) concentrations. Macrophage concentration correlated significantly with IL-1β (r = 0.284, P = 0.003), IL-6 (r = 0.545, P < 0.001), IL-8 (r = 0.256, P = 0.009), and TNF-α (r = 0.518, P < 0.001) concentrations. Lymphocytes correlated significantly with IL-1β (r = 0.297, P = 0.002), IL-6 (r = 0.329, P = 0.001), TNF-α (r = 0.486, P < 0.001) but not with IL-8 (r = 0.163, P = 0.098).

Correlations between cytokines were significant for the following pairs: IL-1β and TNF-α (r = 0.254, P < 0.001), IL-6 and IL-8 (r = 0.307, P < 0.001), IL-6 and TNF-α (r = 0.522, P < 0.001), and IL-8 and TNF-α (r = 0.272, P < 0.001). Correlations between the following cytokines were not significant: IL-1β and IL-6 (r = 0.122, P = 0.116) and IL-1β and IL-8 (r = 0.076, P = 0.321).

The effect of serial ear paracentesis on cell and cytokine concentrations was examined. At 12 h, inflammatory cell concentrations were lower in 11 ears aspirated twice than in 26 ears aspirated once (P < 0.001). At 24 h, cell concentrations were lower in 8 ears tapped thrice than in 26 ears tapped twice (P = 0.045). However, cytokine concentrations had the opposite trend. At 12 h, IL-1β concentrations were higher in 9 ears tapped twice than in 26 ears tapped once (P = 0.001). At 24 h, IL-1β concentrations were not significantly different in 6 ears tapped thrice than in 26 ears tapped twice (P = 0.406).

Serum samples were not obtained concurrently with MEF samples for use in this study for cytokine analysis. However, none of the four cytokines were detected in serum from uninfected, healthy chinchillas.

MEF from uninfected control chinchillas with Eustachian tube obstruction showed only scant numbers of inflammatory cells and no detectable IL-1β or IL-8; hence, middle ear inflammation was most likely a direct response to the pneumococcal middle ear inoculum.

DISCUSSION

Cytokines participate in middle ear inflammation as they do in many other infectious diseases. This study illustrates the close interrelationships among proinflammatory cytokines and between cytokines and acute inflammatory cells in MEF during the early phase of acute pneumococcal otitis media in the chinchilla model. This model is similar to human otitis media because the bacterial inoculum is very small. In the model, type 3 pneumococci grow in the middle ear much as they do in vitro with lag, log, and stationary phases (Fig. 1). Most pneumococcal serotypes are slowly eliminated by the chinchillas with low mortality even without antibiotic treatment (10).

IL-1β was detected in 50% of MEF samples at 1 h and peaked 6 h after pneumococcal inoculation, before appreciable inflammatory cell accumulation, suggesting that IL-1β was produced by cells in the middle ear mucosa. However, IL-1β and MEF neutrophil concentrations were significantly correlated, suggesting that neutrophils also produced IL-1β, perhaps contributing to the secondary IL-1β increase after 24 h (Fig. 2).

IL-6 was detected in 50% of 2-h samples, then decreased between 4 and 24 h, and increased at 48 and 72 h, when the bacterial and inflammatory cell concentrations were stable, suggesting that IL-6 was produced by accumulated inflammatory cells. The early increase at 2 h could be attributed to production by cells in the middle ear mucosa.

IL-8 and TNF-α concentrations continued to increase at 72 h, when the inflammatory cell concentration had stabilized, suggesting they were partially derived from inflammatory cells. The relative insensitivity of the IL-8 ELISA kit most likely contributed to detection of IL-8 in only about one-third of MEF samples. IL-8 alone did not have significant correlation with lymphocytes, supporting the theory that IL-8 is primarily a neutrophil chemoattractant. TNF-α may also have been derived from middle ear mucosa, as was recently demonstrated in endotoxin-induced otitis media in the chinchilla model (7).

Serial fluid aspiration from a closed compartment may potentially alter cellular and chemical composition of the compartment. However, the middle ear space is dynamic, with cell and fluid distribution into and out of the space across the middle ear membrane; thus, a small volume of aspirate is likely to be reconstituted rather promptly. We had sufficient data to examine the effect of initial versus subsequent aspiration on samples obtained at 12 and 24 h. Cellular concentration in MEF was lower in the subsequent aspirate but cytokine (IL-1β) was higher in the subsequent aspirate, suggesting that cytokines are replenished more rapidly than inflammatory cells can migrate into the space. Human cytokine ELISA kits have been used by others to study cytokine responses in experimental otitis media. In one study, the presence of IL-1β in MEF after pneumococcal inoculation was related to MEF presence before inoculation (14). We previously reported that IL-1β and IL-6 concentrations in chinchilla MEF increased with inflammatory cell influx accelerated by penicillin treatment following pneumococcal inoculation (28). However, the single MEF sampling time 24 h after inoculation in the previous study might have missed the actual peaks of IL-1β and IL-6. Moreover, the relatively low detection rate of cytokines in our previous (28) and present experiment might be due to low cross-reactivity between human anticytokine antibodies and chinchilla cytokines. In a rat otitis media model, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced serum transudation into the middle ear was attenuated by TNF binding protein, but not by IL-1 receptor antagonist, suggesting that TNF, not IL-1, is a mediator of LPS-induced otitis media (1). Although serum was not analyzed for cytokines in this study, it seems unlikely that systemic cytokine production occurred in the absence of bacteremia, a characteristic of this serotype in chinchillas (28).

The contribution of cytokines to middle ear inflammation has been studied in MEF obtained from children with chronic OME (5, 11, 16, 21, 22, 30, 32–34). IL-1β (33), TNF-α (33), and IL-6 (34) MEF concentrations were inversely correlated with age, and IL-1β concentrations were higher in purulent MEF than in serous or mucoid MEF (11, 16). IL-8 transcripts were detected in 75% of MEF from both pediatric and adult chronic OME patients (30). Children with recurrent AOM had significantly lower nasopharyngeal IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α production than healthy children (20). Higher levels of IL-8 and polymorphonuclear leukocyte products such as leukotriene B4 in MEF were related to delayed recovery or AOM recurrence (5). Higher TNF-α in MEF was associated with a history of multiple tympanostomy tube placements, which indicates chronicity of the middle ear disease (32). As in our experimental study, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in MEF from children with OME were also highly correlated each other (32). IL-8 concentration in MEF obtained from children with OME was positively correlated with total inflammatory cell numbers and percentage of neutrophils (22). Both IL-1β and TNF-α in MEF were correlated with the concentration of IL-8 (21).

An important virulence factor in pneumococcal otitis media may be pneumolysin since human monocytes exposed to pneumolysin in vitro produced more IL-1β and TNF-α than unexposed control monocytes (12). However, our study with a pneumolysin-deficient strain did not support a role for pneumolysin in otitis media pathogenesis (28).

Cytokines often act together. IL-1 from monocytes stimulated the release of IL-6 and IL-8 (6). Conditions for IL-6 and IL-8 production are strikingly parallel (26, 31). TNF-α potentiated IL-8 secretion by histamine-stimulated endothelial cells (13). IL-1β-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells induced IL-1β and TNF-α synthesis (8).

Recent studies have also shown that inflammatory cytokines can directly induce middle ear inflammation. Human recombinant IL-2 and TNF injected into the middle ear of guinea pigs caused an inflammatory middle ear effusion (4). Inoculation of human IL-8 into murine middle ears induced histological changes peaking 4 to 8 h after injection, and the changes were similar to those after injection of nonviable S. pneumoniae (15). Therefore, treatment strategies that reduce or neutralize inflammatory cytokines, such as administrating cytokine antibodies or cytokine receptors, may be effective adjuvants in otitis media management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grant no. PO1-DC00133 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball S S, Prazma J, Dais C G D, Triana R J, Pillsbury H C. Role of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 in endotoxin-induced middle ear effusions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;106:633–639. doi: 10.1177/000348949710600803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bluestone C D, Stephenson J S, Martin L M. Ten-year review of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:S7–S11. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199208001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canafax D M, Nonomura N, Erdman G R, Le C T, Juhn S K, Giebink G S. Experimental animal models for studying antimicrobial pharmacokinetics in otitis media. Pharm Res. 1989;6:279–285. doi: 10.1023/a:1015938205892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catanzaro A, Ryan A, Batcher S, Wasserman S I. The response to human rIL-1, rIL-2, and rTNF in the middle ear of guinea pigs. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:271–275. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chonmaitree T, Patel J A, Garofalo R, Uchida T, Sim T, Owen M J, Howie V M. Role of leukotriene B4 and interleukin-8 in acute bacterial and viral otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:968–974. doi: 10.1177/000348949610501207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colotta F, Re F, Muzio M, Bertini R, Polentarutti N, Sironi M, Giri J G, Dower S K, Sims J E, Mantovani A. Interleukin-1 type II receptor: a decoy target for IL-1 that is regulated by IL-4. Science. 1993;261:472–475. doi: 10.1126/science.8332913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMaria T F, Murwin D M. Tumor necrosis factor during experimental lipopolysaccharide-induced otitis media. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:369–372. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199703000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endres S, Ehitaker R E D, Ghorbani R, Meydani S N, Dinarello C A. Oral aspirin and ibuprofen increase cytokine-induced synthesis of IL-β and of tumor necrosis factor-α ex vivo. Immunology. 1996;87:264–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.472535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giebink G S. The microbiology of otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:S18–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giebink G S, Berzins I K, Quie P G. Animal models for studying pneumococcal otitis media and pneumococcal vaccine efficacy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;68(Suppl.):339–343. doi: 10.1177/00034894800890s380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Himi T, Suzuki T, Kodama H, Takezawa H, Kataura A. Immunologic characteristics of cytokines in otitis media with effusion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992;101:21–25. doi: 10.1177/0003489492101s1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houldsworth S, Andrew P W, Mitchell T J. Pneumolysin stimulates production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1β by human mononuclear phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1501–1503. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1501-1503.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeannin P, Delneste Y, Gosset P, Molet S, Lassalle P, Hamid Q, Tsicopoulos A, Tonnel A B. Histamine induces interleukin-8 secretion by endothelial cells. Blood. 1994;84:2229–2233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson M D, Fitzgerald J E, Leonard G, Burleson J A, Kreutzer D L. Cytokines in experimental otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:191–196. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson M, Leonard G, Kreutzer D L. Murine model of interleukin-8-induced otitis media. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1405–1408. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhn S K, Garvis W J, Lees C J, Le C T, Kim C S. Determining otitis media severity from middle ear fluid analysis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:43–45. doi: 10.1177/00034894941030s512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawana M. Early inflammatory changes of the Haemophilus influenzae-induced experimental otitis media. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1995;22:80–85. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawana M, Kawana C, Giebink G S. Penicillin treatment accelerates middle ear inflammation in experimental pneumococcal otitis media. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1908–1912. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.1908-1912.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawana M, Kawana C, Yokoo T, Quie P G, Giebink G S. Oxidative metabolic products released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes in middle ear during experimental otitis media. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4084–4088. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4084-4088.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindberg K, Rynnel-Dagoo B, Sundqvist K-G. Cytokines in nasopharyngeal secretions; evidence for defective IL-1β production in children with recurrent episodes of acute otitis media. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;97:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell K S, Fitzgerald J E, Burleson J A, Leonard G, Carpenter R, Kreutzer D L. Interleukin-8 expression in otitis media. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:989–995. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199408000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nassif P S, Simpson S Q, Izzo A A, Nicklais P J. Interleukin-8 concentration predicts the neutrophil count in middle ear effusion. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1223–1227. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199709000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nonomura N, Giebink G S, Juhn S K, Harada T, Aeppli D. Pathophysiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae otitis media: kinetics of the middle ear biochemical and cytological host responses. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:236–243. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nonomura N, Nakano Y, Fujioka O, Niijima H, Kawana M, Fujita M. Experimentally induced otitis media with effusion following inoculation with the outer cell wall of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 1987;244:253–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00455316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nonomura N, Nakano Y, Satoh Y, Fujioka O, Niijima H, Fujita M. Otitis media with effusion following inoculation of Haemophilus influenzae type b endotoxin. Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 1986;243:31–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00457904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rampart M, Herman A G, Grillet B, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J. Development and application of a radioimmunoassay for interleukin-8: detection of interleukin-8 in synovial fluids from patients with inflammatory joint disease. Lab Investig. 1992;66:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato K. Experimental otitis media induced by nonviable Moraxella catarrhalis in the guinea pig model. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1997;24:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0385-8146(96)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato K, Quartey M K, Liebeler C L, Le C T, Giebink G S. Roles of autolysin and pneumolysin in middle ear inflammation caused by a type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae in the chinchilla otitis media model. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1140–1145. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1140-1145.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato K, Quartey M K, Liebeler C L, Giebink G S. Timing of penicillin treatment influences the course of Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced middle ear inflammation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1896–1898. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeuchi K, Maesato K, Yuta A, Sakakura Y. Interleukin-8 gene expression in middle ear effusions. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:404–407. doi: 10.1177/000348949410300511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Snick J, Cayphas S, Vink A, Uyttenhove C, Coulie P G, Rubira M R, Simpson J. Purification and NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of a T-cell-derived lymphokine with growth factor activity for B-cell hybridomas. Proc Natl Acad USA. 1986;83:9679–9683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yellon R F. Cytokines, immunoglobulins, and bacterial pathogens in middle ear effusions. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:865–869. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890080033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yellon R F, Leonard G, Marucha P T, Craven R, Carpenter R J, Lehmann W B, Burleson J A, Kreutzer D L. Characterization of cytokines present in middle ear effusions. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:165–169. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yellon R F, Leonard G, Marucha P, Sidman J, Carpenter R, Burleson J, Carlson J, Kreutzer D. Demonstration of interleukin 6 in middle ear effusions. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:745–748. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880070075014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]