Abstract

Simple Summary

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors diagnosed with cancer between ages 18–39 years often experience negative body changes, such as scars, amputation, hair loss, disfigurement, body weight changes, skin buns, and physical movement limitations. A negative body image could have negative implications for the self-esteem, self-identity, and social relationships of AYAs. Despite the possible long-term effects of cancer on body image, within the AYA literature, limited studies focus on AYA cancer survivors in a quantitative way. Therefore, the aim of our population-based cross-sectional study was to examine the prevalence, and association of a negative body image with sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors, among AYA survivors 5–20 years after diagnosis. Raising awareness and integrating supportive care for those who experience a negative body image into standard AYA survivorship care is warranted. Future longitudinal research could help to identify when and how this support for AYA survivors can be best utilized.

Abstract

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivors (18–39 years at diagnosis) often experience negative body changes such as scars, amputation, and disfigurement. Understanding which factors influence body image among AYA survivors can improve age-specific care in the future. Therefore, we aim to examine the prevalence, and association of a negative body image with sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors, among AYA cancer survivors (5–20 years after diagnosis). A population-based cross-sectional cohort study was conducted among AYA survivors (5–20 years after diagnosis) registered within the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) (SURVAYA-study). Body image was examined via the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-SURV100. Multivariable logistic regression models were used. Among 3735 AYA survivors who responded, 14.5% (range: 2.6–44.2%), experienced a negative body image. Specifically, AYAs who are female, have a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) or tumor stage, diagnosed with breast cancer, cancer of the female genitalia, or germ cell tumors, treated with chemotherapy, using more maladaptive coping strategies, feeling sexually unattractive, and having lower scores of health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL), were more likely to experience a negative body image. Raising awareness and integrating supportive care for those who experience a negative body image into standard AYA survivorship care is warranted. Future research could help to identify when and how this support for AYA survivors can be best utilized.

Keywords: body image, adolescents and young adults, cancer survivorship, population-based research

1. Introduction

Although cancer is a disease primarily affecting older adults, each year around 3900 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 18–39 years in the Netherlands are diagnosed with cancer for the first time [1]. AYAs are recognized as a distinct population within oncology, since they face unique challenges given the complex phase of life, including many physical, emotional, and social transitions [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Important and complex age-related developmental milestones need to be achieved, including forming their own identity and a positive body image; establishing autonomy, responsibility, and independence; finishing education and starting a career; beginning a relationship and having children [9,10]. The cancer diagnosis and treatment(s) can disrupt these physical, cognitive, and psychosocial developmental milestones for AYAs, which can lead to a reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4,6,10,11]. Since the overall five-year survival rate for AYAs has improved to 80%, many AYAs have a long life ahead after their cancer diagnosis [12]. Therefore, achieving and maintaining optimal HRQoL is an important aspect of AYAs [4,13,14].

A major concern for AYAs potentially affecting their HRQoL, are problems with body image [3,4,7,10,13,15]. For cancer patients, body image is an important multidimensional and complex concept connected to multiple aspects of cancer and its treatments [13,16,17]. Body image involves positive and negative perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors about the entire body and its functioning [13,16,17]. Cancer and related treatments can cause temporary or permanent body changes, which may negatively affect body image [13,16,18,19]. AYAs describe that their body is greatly affected by cancer and the treatment(s), with negative changes in body image such as scars, amputation, hair loss, disfigurement, changes in body weight, skin burns, and limitations in physical movements [7,18,19]. Some AYAs describe that they no longer feel in control of their body after cancer, and see their body as a threat to their health and functioning, or as a source of discomfort [18]. Adding to this, a negative body image could have negative implications for the self-esteem, self-identity, and social relationships of AYAs [7,11,19,20].

Different studies have supported the need of understanding the complexity of body image within the AYA population [4,11,13,21]. A recent scoping review by Vani et al. [13] showed that existing quantitative studies are mainly addressing body image from the perspective of tumor histology, focusing on specific cancer groups, rather than from an AYA-specific perspective [13,14]. The available studies with an age-specific focus have a qualitative design, indicating that currently little is known about the prevalence and what factors are associated with a negative body image [21,22,23,24]. Moreover, despite the possible long-term effects of cancer on body image, within the AYA literature limited attention has been given to long-term AYA cancer survivors (>five years after diagnosis) [4,13].

To raise understanding, the aim of this population-based study is to assess the prevalence of a negative body image among AYA survivors 5–20 years after diagnosis. Furthermore, we aim to examine the association between sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors and a negative body image among AYA survivors 5–20 years after diagnosis. Understanding who is at risk for a negative body image and why will help to improve age-specific care regarding body image issues for AYA survivors in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Population

This population-based cross-sectional cohort study was performed among AYA cancer survivors (18–39 years old at the time of diagnosis) registered within the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR): the SURVAYA study. The SURVAYA study (Health-related quality of life and late effects among SURVivors of cancer in Adolescence and Young Adulthood) was conducted in the Netherlands Cancer Institute and all University Medical Centers in the Netherlands. The SURVAYA study was approved by the Netherlands Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board (IRB-IRBd18122) and was registered within clinical trial registration (NCT05379387). The Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) was used to select the AYA survivors for the SURVAYA study and the AYA survivors from the SURVAYA study who at least answered half of the ten items on body image were included in this secondary analysis on body image.

2.2. Data Collection

Data for the SURVAYA study were collected between May 2019 and June 2021 within PROFILES (Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship) [14], which is a registry for the study of the physical and psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatments and is directly linked to clinical data from the NCR [14]. The NCR routinely collects data on tumor characteristics and patients’ background characteristics at the primary diagnosis. Details on data collection for the SURVAYA study have previously been described [25].

2.3. Study Measures

Factors potentially associated with a negative body image, based on the literature [13,26,27,28] and used in this study, were: age (at questionnaire), gender, relationship status, level of education, tumor type, tumor stage, treatment, time since diagnosis, physical activity level, Body Mass Index (BMI), Coping style, HRQoL, and sexual attractiveness.

Sociodemographic data, like age at questionnaire, gender (male/female), relationship status (partner yes/no), and level of education (no or primary school (low), secondary school (intermediate), college or university (high)) were collected by self-report in the questionnaire. Clinical data including tumor type, tumor stage (I–IV), treatment (surgery (local or organ), chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, or stem cell transplantation), and date of diagnosis were available from the NCR.

The level of physical activity was assessed with items derived from the validated European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC) Physical Activity Questionnaire [29]. A total level of physical activity was calculated by summing up all hours/week of all activities (walking, bicycling, gardening, housekeeping, and sports) [29]. To include an estimate of intensity, metabolic equivalent intensity values (MET) were assigned to each activity according to the compendium of physical activity, and a total physical activity in MET hours/week was calculated [30]. BMI was calculated with the self-reported body height and weight and categorized into underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (18.5 < BMI < 25), overweight (25 < BMI < 30), and obesity (BMI > 30) [31].

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) was part of the questionnaire and used to identify which cognitive coping strategies AYA survivors use when experiencing negative events or situations [32,33,34]. The identified coping styles were dichotomized into two general categories: adaptive (acceptance, positive refocusing, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, putting into perspective) and maladaptive (self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, and blaming others) [32,34]. A higher score (0–50 for adaptive and 0–40 for maladaptive) indicates an AYA survivor is using the coping style more frequently in response to a negative event [32].

HRQoL was measured by the functional scales and global health status from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), in which higher scores represent a higher level of functioning compared to a lower score [35]. Furthermore, a one-scale item “Have you been feeling less sexually attractive as a result of your disease or treatment?” was used to describe sexual attractiveness.

Body image was assessed with ten items from the EORTC QLQ-C30 [35] and an extended version of the EORTC HRQoL cancer survivorship core questionnaire (QLQ-SURV100) [36]. All ten items were scored on a four-point Likert scale. To describe each item separately, a score of three points or higher was considered and dichotomized as having a negative body image. Furthermore, to assess the prevalence of a negative body image, a total score of body image was calculated according to the EORTC scoring guidelines for each AYA survivor, scoring from 0–100 [37]. Higher scores indicate more symptoms of a negative body image. A total body image score of at least one standard deviation above the mean of all body image scores (cut-off: ≥38.15) was considered and dichotomized as having a negative body image [37].

2.4. Data Analysis

The study population was described with means (including standard deviations) and frequencies (with percentages), stratified by body image (“negative body image” vs. “not a negative body image”). Chi-square and independent t-tests were used to assess differences between the group who answered at least half of the items on body image and those who did not.

To examine the prevalence, a proportion of how many AYA survivors experienced a negative body image was calculated, for a total of 10 items and for each item separately. To assess the association between potential factors and a negative body image, univariable logistic regression models were fitted. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted by including all independent significant associations from the univariable model (p-value < 0.1). Multicollinearity in the multivariable model was explored by using the tolerance statistic (p-value < 0.1 indicate multicollinearity), variance inflation factor (VIF > 10 indicates multicollinearity), and variance proportions (proportions on the same eigenvalue ≥ 0.7 indicate multicollinearity). A sensitivity analysis was conducted to explore the effect of the item on scars (this item was not applicable to everyone) on the total prevalence of a negative body image and the logistic regression model.

If items on the EORTC-scales for body image and HRQoL were missing, and at least half of the items from that scale were answered, the scale scores were calculated by mean case analysis [37]. If less than half of the items from the scales were answered, the scale score was set to missing [37]. For all other variables, missing items were set to missing. For categorical variables with more than 30 missing values, an extra category was created with the label missing values. For continuous variables, missing data were handled by pairwise deletion.

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and all tests were two-sided with a p-value < 0.05 for statistical difference.

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics

In total, in the SURVAYA study n = 4010 AYA survivors completed the questionnaire, resulting in an overall response rate of 36%. In this secondary analysis on body image n = 3735 eligible, AYA survivors were included. The differences in population characteristics of AYA survivors who answered at least half of the ten items on body image (eligible) and who did not (not eligible), are displayed in Table 1. Differences between these groups were seen in tumor type and chemotherapy received (yes/no).

Table 1.

Differences in characteristics of the included and excluded AYA survivors.

| Population Characteristics | Included AYA Survivors 1 | Excluded AYA Survivors 2 | p-Value 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3735 | n = 275 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age at questionnaire—Mean (SD) | 44.5 (7.5) | 44.0 (7.2) | 0.242 | |||

| Gender | Male | 1456 | 39.0 | 93 | 33.8 | 0.090 |

| Female | 2279 | 61.0 | 182 | 66.2 | ||

| Type of Cancer | Melanoma | 258 | 6.9 | 32 | 11.6 | 0.034 |

| Head and neck | 115 | 3.1 | 9 | 3.3 | ||

| Colon and rectal | 76 | 2.0 | 6 | 2.2 | ||

| Digestive tract other 4 | 30 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Breast | 885 | 23.7 | 59 | 21.5 | ||

| Female genitalia | 407 | 10.9 | 38 | 13.8 | ||

| Thyroid gland | 228 | 6.1 | 20 | 7.3 | ||

| Central nervous system | 142 | 3.8 | 8 | 2.9 | ||

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 165 | 4.4 | 7 | 2.5 | ||

| Germ cell tumor | 653 | 17.5 | 39 | 14.2 | ||

| Lymphoid hematological malignancies | 555 | 14.9 | 36 | 13.1 | ||

| Myeloid hematological malignancies | 140 | 3.7 | 8 | 2.9 | ||

| Other 5 | 81 | 2.2 | 12 | 4.4 | ||

| Treatments 6 | Surgery organ (yes) 7 | 2483 | 66.6 | 172 | 62.5 | 0.175 |

| Surgery local (yes) 8 | 537 | 14.4 | 49 | 17.8 | 0.121 | |

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 2104 | 56.4 | 135 | 49.1 | 0.019 | |

| Radiotherapy (yes) 9 | 1779 | 47.7 | 128 | 46.5 | 0.716 | |

| Hormone therapy (yes) | 455 | 12.2 | 29 | 10.5 | 0.418 | |

| Targeted therapy (yes) | 289 | 7.7 | 18 | 6.5 | 0.470 | |

| Stem cell transplantation (yes) | 135 | 3.6 | 7 | 2.5 | 0.353 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 1595 | 42.7 | 131 | 47.6 | 0.358 |

| II | 991 | 26.5 | 72 | 26.2 | ||

| III | 535 | 14.3 | 38 | 13.8 | ||

| IV | 171 | 4.6 | 8 | 2.9 | ||

| Unknown | 443 | 11.9 | 26 | 9.5 | ||

| Age at diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 31.6 (5.9) | 31.6 (5.5) | 0.993 | |||

| Time since diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 12.4 (4.5) | 11.9 (4.6) | 0.057 | |||

| <10 years | 1274 | 34.1 | 111 | 40.4 | 0.109 | |

| 10–15 years | 1307 | 35.0 | 87 | 31.6 | ||

| >15 years | 1154 | 30.9 | 77 | 28.0 | ||

1 AYA survivors who completed at least half of the items on body image and were included in the statistical analysis. 2 AYA survivors who completed less than half of the items on body image were excluded from the statistical analysis. 3 The bold p-values show a statistically significant difference (p-value < 0.05) between the two groups. 4 Digestive tract and other includes the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. 5 Other includes respiratory, male genitalia (penis, prostate), urinary tract, tumor with other localizations, endocrine glands, eye, neuroblastoma, paraganglioma. 6 The treatments were received at primary diagnosis (missing n = 4 for included AYA survivors because the NCR did not provide therapy registration for them). 7 Organ surgery is defined as the complete resection of the affected organ. 8 Local surgery is defined as resection of the tumor/metastasis only. 9 Radiotherapy includes radiotherapy for primary tumors and metastases at primary diagnosis. n = number of AYA survivors, Mean (SD) = mean and standard deviation.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the included AYA survivors. The mean age of these AYA survivors at the time of the questionnaire was 44.5 (SD 7.5) years with a mean time since diagnosis of 12.4 (SD 4.5) years. The most common diagnoses were breast cancer (23.7%), germ-cell tumors (17.5%), cancer of the female genitalia (10.9%), melanomas (6.9%), and thyroid cancer (6.1%). Most AYA survivors were female (61.0%), had a partner when completing the questionnaire (83.1%), and were diagnosed at stage I (42.7%).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of the included AYA survivors.

| Population Characteristics | Total Included AYA Survivors 1 | AYA Survivors with a Negative Body Image |

AYA Survivors without a Negative Body Image |

Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3735 | n = 541 | n = 3194 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age at questionnaire—Mean (SD) | 44.5 (7.5) | 44.2 (7.3) | 44.6 (7.5) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 1456 | 39.0 | 94 | 6.5 | 1362 | 93.5 | |

| Female | 2279 | 61.0 | 447 | 19.6 | 1832 | 80.4 | ||

| Partner (yes) | 3107 | 83.4 | 395 | 12.7 | 2710 | 87.3 | 13 | |

| Level of education | Low | 24 | 0.6 | 6 | 25.0 | 18 | 75.0 | 8 |

| Intermediate | 1601 | 42.9 | 277 | 17.3 | 1322 | 82.7 | ||

| High | 2106 | 56.4 | 257 | 12.2 | 1847 | 87.8 | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Type of Cancer | Melanoma | 258 | 6.9 | 18 | 7.0 | 240 | 93.0 | |

| Head and neck | 115 | 3.1 | 12 | 10.4 | 103 | 89.6 | ||

| Colon and rectal | 76 | 2.0 | 8 | 10.5 | 68 | 89.5 | ||

| Digestive tract other 2 | 30 | 0.8 | 6 | 20.0 | 24 | 80.0 | ||

| Breast | 885 | 23.7 | 191 | 21.6 | 694 | 78.4 | ||

| Female genitalia | 407 | 10.9 | 92 | 22.6 | 315 | 77.4 | ||

| Thyroid gland | 228 | 6.1 | 26 | 11.4 | 202 | 88.6 | ||

| Central nervous system | 142 | 3.8 | 22 | 15.5 | 120 | 84.5 | ||

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 165 | 4.4 | 20 | 12.1 | 145 | 87.9 | ||

| Germ cell tumor | 653 | 17.5 | 38 | 5.8 | 615 | 94.2 | ||

| Lymphoid hematological malignancies | 555 | 14.9 | 76 | 13.7 | 479 | 86.3 | ||

| Myeloid hematological malignancies | 140 | 3.7 | 21 | 15.0 | 119 | 85.0 | ||

| Other 3 | 81 | 2.2 | 11 | 13.6 | 70 | 86.4 | ||

| Treatments 4 | Surgery organ (yes) | 2483 | 66.6 | 368 | 14.8 | 2115 | 85.2 | 4 |

| Surgery local (yes) | 537 | 14.4 | 69 | 12.8 | 468 | 87.2 | 4 | |

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 2104 | 56.4 | 342 | 16.3 | 1762 | 83.7 | 4 | |

| Radiotherapy (yes) 5 | 1779 | 47.7 | 299 | 16.8 | 1480 | 83.2 | 4 | |

| Hormone therapy (yes) | 455 | 12.2 | 113 | 24.8 | 342 | 75.2 | 4 | |

| Targeted therapy (yes) | 289 | 7.7 | 53 | 18.3 | 236 | 81.7 | 4 | |

| Stem cell transplantation (yes) | 135 | 3.6 | 15 | 11.1 | 120 | 88.9 | 4 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 1595 | 42.7 | 190 | 11.9 | 1405 | 88.1 | |

| II | 991 | 26.5 | 174 | 17.6 | 817 | 82.4 | ||

| III | 535 | 14.3 | 87 | 16.3 | 448 | 83.7 | ||

| IV | 171 | 4.6 | 28 | 16.4 | 143 | 83.6 | ||

| Unknown | 443 | 11.9 | 62 | 14.0 | 381 | 86.0 | ||

| Age at diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 31.6 (5.9) | 31.9 (5.8) | 31.5 (5.9) | |||||

| Time since diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 12.4 (4.5) | 11.8 (4.5) | 12.6 (4.5) | |||||

| <10 years | 1274 | 34.1 | 223 | 17.5 | 1051 | 82.5 | ||

| 10–15 years | 1307 | 35.0 | 171 | 13.1 | 1136 | 86.9 | ||

| >15 years | 1154 | 30.9 | 147 | 12.7 | 1007 | 87.3 | ||

| Physical activity | Time in hours/week—Mean (SD) | 27.9 (25.2) | 30.1 (26.3) | 27.5 (24.8) | 20 | |||

| In MET hours/week—Mean (SD) | 108.6 (92.3) | 114.1 (96.5) | 107.6 (91.4) | |||||

| BMI—Mean (SD) | 25.2 (4.4) | 26.9 (5.9) | 24.9 (4.0) | 24 | ||||

| Underweight | 58 | 1.6 | 11 | 19.0 | 47 | 81.0 | ||

| Normal weight | 2004 | 53.9 | 224 | 11.2 | 1777 | 88.8 | ||

| Overweight | 1218 | 32.8 | 167 | 13.7 | 1050 | 86.3 | ||

| Obesity | 435 | 11.7 | 136 | 31.3 | 299 | 68.7 | ||

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||||||||

| Coping style | Adaptive—Mean (SD) | 29.3 (7.4) | 30.0 (7.1) | 29.1 (7.5) | 45 | |||

| Maladaptive—Mean (SD) | 13.7 (3.8) | 15.7 (4.6) | 12.8 (3.5) | 31 | ||||

| HRQoL | Physical functioning—Mean (SD) | 91.5 (14.0) | 80.5 (18.8) | 93.3 (12.1) | 2 | |||

| Role functioning—Mean (SD) | 83.2 (25.4) | 59.7 (32.1) | 87.2 (21.7) | 6 | ||||

| Emotional functioning—Mean (SD) | 79.5 (20.6) | 57.9 (24.1) | 83.1 (17.5) | 2 | ||||

| Cognitive functioning—Mean (SD) | 77.9 (24.4) | 57.7 (28.5) | 81.3 (21.9) | 5 | ||||

| Social functioning—Mean (SD) | 87.9 (22.0) | 66.3 (31.1) | 91.6 (17.7) | 13 | ||||

| Global health status—Mean (SD) | 75.2 (17.5) | 59.2 (19.8) | 77.9 (15.6) | 14 | ||||

| Sexual attractiveness (yes) | 2704 | 72.7 | 497 | 18.4 | 2203 | 81.6 | 18 | |

1 Included AYA survivors completed at least half of the ten items on body image. 2 Digestive tract and other includes the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. 3 Other includes respiratory, male genitalia (penis, prostate), urinary tract, tumor with other localizations, endocrine glands, eye, neuroblastoma, paraganglioma. 4 The treatments were received at primary diagnosis. 5 Radiotherapy includes radiotherapy for primary tumor and metastases at primary diagnosis. n = number of AYA survivors, Mean (SD) = mean and standard deviation.

3.2. Body Image

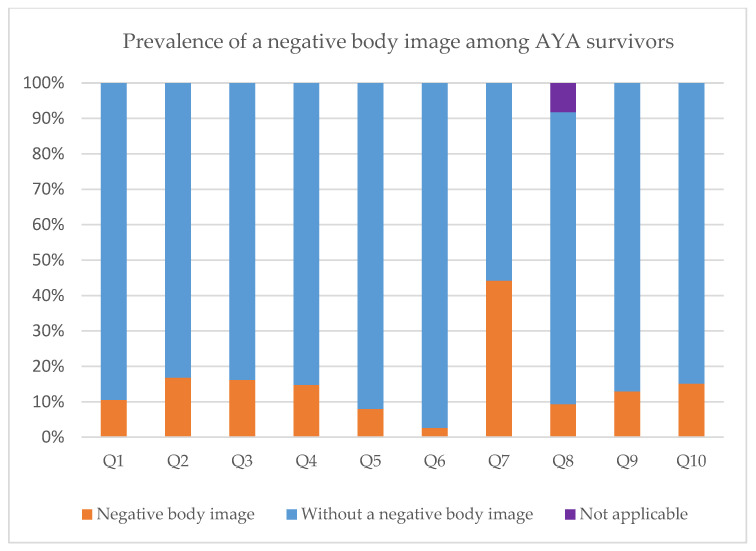

Overall, 541 (14.5%) AYA survivors experienced a negative body image (Table 3 and Figure 1). Almost half (44.2%) reported that their body did not feel complete. One out of six AYA survivors reported that they felt older than their age (16.8%), were dissatisfied with their physical appearance (16.2%), and felt less masculine/feminine due to cancer or its treatment (15.1%). A small percentage of AYA survivors avoided people because of how they felt about their physical appearance (2.6%) or felt embarrassed about their physical appearance (8.0%).

Table 3.

Prevalence of a negative body image among AYA survivors.

| Prevalence of a Negative Body Image | AYA Survivors with a Negative Body Image | AYA Survivors without a Negative Body Image | Item Answered as ‘Not Applicable’ | Missing 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | |||

| Total prevalence | |||||||

| Prevalence of a negative body image (with Q8) | 541 | 14.5 | 3194 | 85.5 | |||

| Prevalence of a negative body image (without Q8) | 548 | 14.7 | 3187 | 85.3 | |||

| Ten items on body image | |||||||

| Q1. Have you felt unattractive? | 391 | 10.5 | 3343 | 89.5 | 1 | ||

| Q2. Have you felt older than your age? | 628 | 16.8 | 3105 | 83.2 | 2 | ||

| Q3. Have you been dissatisfied with your physical appearance? | 603 | 16.2 | 3130 | 83.8 | 2 | ||

| Q4. Have you felt that you could not trust your body? | 554 | 14.8 | 3180 | 85.2 | 1 | ||

| Q5. Have you felt embarrassed about your body? | 297 | 8.0 | 3438 | 92.0 | 0 | ||

| Q6. Did you avoid people because of the way you felt about your appearance? | 96 | 2.6 | 3636 | 97.4 | 3 | ||

| Q7. Did your body feel complete? | 1650 | 44.2 | 2083 | 55.8 | 2 | ||

| Q8. Have you been dissatisfied with the appearance of the scars? 2 | 348 | 9.3 | 3076 | 82.5 | 306 | 8.2 | 5 |

| Q9. Did you judge your physical appearance more negatively since the diagnosis and treatment of cancer? | 482 | 12.9 | 3247 | 87.1 | 6 | ||

| Q10. Have you felt less masculine/feminine as a result of your illness or treatment since the diagnosis and treatment of cancer? | 564 | 15.1 | 3166 | 84.9 | 5 | ||

1 The missing values were not part of the calculated percentages for the ten items on body image. 2 For item Q8 participants could also answer ‘not applicable’.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of a negative body image among AYA survivors: Q1. Have you felt unattractive? Q2. Have you felt older than your age? Q3. Have you been dissatisfied with your physical appearance? Q4. Have you felt that you could not trust your body? Q5. Have you felt embarrassed about your body? Q6. Did you avoid people because of the way you felt about your appearance? Q7. Did your body feel complete? Q8. Have you been dissatisfied with the appearance of the scars? (Participants could also answer ‘not applicable’) Q9. Did you judge your physical appearance more negatively since the diagnosis and treatment of cancer? Q10. Have you felt less masculine/feminine as a result of your illness or treatment since the diagnosis and treatment of cancer?

3.3. Logistic Regression

Univariable logistic regression models showed that females, AYA survivors without a partner, those with a lower level of education, and higher tumor stage were significantly more likely to experience a negative body image (Table 4). Furthermore, tumor type, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, BMI, maladaptive coping style, sexual attractiveness, the functional scales of HRQoL, and global health status were all independently associated with a negative body image.

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

| Population Characteristics | Univariable Logistic Regression 1 | Multivariable Logistic Regression 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 = 1106.36 (p-Value < 0.001) Nagelkerke R2 = 0.47 |

|||||

| OR [95%CI] | p-Value | OR [95%CI] | p-Value | ||

| Age at questionnaire | 0.99 [0.98–1.01] | 0.318 | |||

| Gender | Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 3.54 [2.80–4.46] | <0.001 | 3.79 [2.49–5.77] | <0.001 | |

| Partner | Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 2.05 [1.65–2.54] | <0.001 | 1.17 [0.88–1.57] | 0.284 | |

| Level of education | Low | 2.40 [0.94–6.09] | 0.067 | 1.91 [0.43–8.49] | 0.398 |

| Medium | 1.51 [1.25–1.81] | <0.001 | 1.13 [0.88–1.44] | 0.336 | |

| High | Reference | Reference | |||

| Type of cancer | Melanoma | Reference | Reference | ||

| Head and neck | 1.55 [0.72–3.34] | 0.260 | 1.68 [0.64–4.30] | 0.283 | |

| Colon and rectal | 1.57 [0.65–3.76] | 0.313 | 0.97 [0.31–2.90] | 0.922 | |

| Digestive tract other 3 | 3.33 [1.21–9.20] | 0.020 | 3.92 [0.98–15.60] | 0.053 | |

| Breast | 3.67 [2.21–6.08] | <0.001 | 2.51 [1.19–5.28] | 0.015 | |

| Female genitalia | 3.89 [2.29–6.63] | <0.001 | 3.15 [1.59–6.24] | <0.001 | |

| Thyroid gland | 1.72 [0.92–3.22] | 0.093 | 0.81 [0.36–1.83] | 0.609 | |

| Central nervous system | 2.44 [1.26–4.73] | 0.008 | 1.00 [0.33–3.03] | 0.996 | |

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 1.84 [0.94–3.59] | 0.074 | 1.82 [0.77–4.29] | 0.170 | |

| Germ cell tumor | 0.82 [0.46–1.47] | 0.513 | 2.51 [1.11–5.65] | 0.027 | |

| Lymphoid hematological malignancies | 2.12 [1.24–3.62] | 0.006 | 2.10 [0.98–4.49] | 0.055 | |

| Myeloid hematological malignancies | 2.35 [1.21–4.58] | 0.012 | 1.78 [0.60–5.32] | 0.303 | |

| Other 4 | 2.10 [0.95–4.64] | 0.069 | 1.20 [0.43–3.33] | 0.732 | |

| Tumor stage | I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.58 [1.26–1.97] | <0.001 | 1.49 [1.07–2.10] | 0.020 | |

| III | 1.44 [1.09–1.89] | 0.010 | 1.72 [1.13–2.61] | 0.012 | |

| IV | 1.45 [0.94–2.23] | 0.093 | 1.73 [0.92–3.25] | 0.087 | |

| Missing | 1.20 [0.88–1.64] | 0.239 | 1.35 [0.68–2.70] | 0.390 | |

| Chemotherapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.40 [1.16–1.69] | <0.001 | 0.68 [0.47–0.99] | 0.041 | |

| Radiotherapy 5,6 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.43 [1.19–1.72] | <0.001 | 1.12 [0.85–1.47] | 0.430 | |

| Hormone therapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.21 [1.74–2.79] | <0.001 | 1.22 [0.81–1.83] | 0.348 | |

| Targeted therapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.36 [1.00–1.86] | 0.053 | 0.97 [0.63–1.50] | 0.905 | |

| Surgery organ 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.09 [0.90–1.32] | 0.398 | |||

| Surgery local 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.85 [0.65–1.12] | 0.248 | |||

| Stem cell transplantation 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.37 [0.79–2.36] | 0.260 | |||

| Time since diagnosis | <10 years | 1.45 [1.16–1.82] | 0.001 | 1.26 [0.94–1.69] | 0.129 |

| 10–15 years | 1.03 [0.81–1.31] | 0.799 | 0.92 [0.68–1.24] | 0.570 | |

| >15 years | Reference | Reference | |||

| Physical activity | MET hours/week | 1.00 [1.00–1.00] | 0.131 | ||

| BMI | Underweight | 1.86 [0.95–3.63] | 0.071 | 0.75 [0.31–1.81] | 0.516 |

| Normal weight | Reference | Reference | |||

| Overweight | 1.26 [1.02–1.56] | 0.034 | 1.70 [1.29–2.24] | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 3.61 [2.82–4.61] | <0.001 | 3.69 [2.66–5.13] | <0.001 | |

| Maladaptive coping style | 1.19 [1.16–1.22] | <0.001 | 1.10 [1.06–1.13] | <0.001 | |

| HRQoL | Physical functioning | 0.95 [0.95–0.96] | <0.001 | 1.00 [0.99–1.00] | 0.306 |

| Role functioning | 0.97 [0.96–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.99–1.00] | 0.009 | |

| Emotional functioning | 0.95 [0.94–0.95] | <0.001 | 0.97 [0.97–0.98] | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.97 [0.96–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.99–1.00] | 0.006 | |

| Social functioning | 0.96 [0.96–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.98–1.00] | 0.001 | |

| Global Health status | 0.95 [0.94–0.95] | <0.001 | 0.98 [0.97–0.99] | <0.001 | |

| Sexual attractiveness | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 5.66 [4.05–7.91] | <0.001 | 3.73 [2.50–5.57] | <0.001 | |

1 Univariable: p-value < 0.1 is included in multivariable analyses. 2 Multivariable: p-value < 0.05 is significant (bold p-values show a statistically significant OR). Method = enter. The multivariable model showed no multicollinearity. 3 Digestive tract and other includes the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. 4 Other includes respiratory, male genitalia (penis, prostate), urinary tract, tumor with other localizations, endocrine glands, eye, neuroblastoma, paraganglioma. 5 The treatments were received at primary diagnosis. 6 Radiotherapy includes radiotherapy for primary tumor and metastases at primary diagnosis. OR [95%CI] = odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

The multivariable analysis showed that gender, tumor type, tumor stage, chemotherapy, BMI, maladaptive coping style, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, global health status (HRQoL), and sexual attractiveness were associated with a negative body image (Table 4). Females were more likely to experience a negative body image compared to men (Odds ratio (OR) = 3.79 [95%Confidence interval (CI): 2.49–5.77]). AYA survivors with breast cancer (OR = 2.51 [95%CI: 1.19–5.28]), cancer of the female genitalia (OR = 3.15 [95%CI: 1.59–6.24]), and germ cell tumors (OR = 2.50 [95%CI: 1.11–5.65]) experienced a negative body image more often compared to AYA survivors with a melanoma. Stage II (OR = 1.49 [95%CI: 1.07–2.10]) and III (OR = 1.72 [95%CI: 1.13–2.61]) disease were associated with greater odds of having a negative body image compared to stage I. AYA survivors who received chemotherapy had lower odds (OR = 0.68 [95%CI: 0.47–0.99]) for having a negative body image compared to those who received no chemotherapy. Furthermore, AYA survivors with overweight (OR = 1.70 [95%CI: 1.29–2.24]) or obesity (OR = 3.69 [95%CI: 2.66–5.13]) more likely experienced a negative body image compared to those with a normal weight. AYA survivors who more often used a maladaptive coping style (higher scores) were more likely to experience a negative body image (OR = 1.10 [95%CI: 1.06–1.13]) compared to those who used less maladaptive coping styles. AYA survivors with higher levels of role functioning (OR = 0.99 [95%CI: 0.99–1.00]), emotional functioning (OR = 0.97 [95%CI: 0.97–0.98]), cognitive functioning (OR = 0.99 [95%CI: 0.99–1.00]), social functioning (OR = 0.99 [95%CI: 0.98–1.00]), and global health status (OR = 0.98 [95%CI: 0.97–0.99]) were less likely to experience a negative body image. AYA survivors who felt sexually unattractive, had greater odds (OR = 3.73 [95%CI: 2.50–5.57]) for a negative body image.

When leaving out the item on scars, the multivariable model showed no differences in associated factors with a negative body image (Appendix A).

4. Discussion

This large population-based cross-sectional cohort study showed that a negative body image remains a problem up to 20 years after cancer diagnosis for almost 15% (range: 2.6–44.2%) of the AYA survivors. Multiple factors were associated with a long-term negative body image, including sociodemographic (gender), clinical (tumor type, chemotherapy, stage, and BMI), and psychosocial factors (maladaptive coping style, sexual attractiveness, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, and global health status).

Among (long-term) breast cancer survivors (not AYA specific) the prevalence of a negative body image is reported between 15–33% [38,39], which is in line with our results. When comparing our results to AYA-specific literature, Vani et al. [13] reported a prevalence of 17–63% among AYA patients. However, the patients participating in the study of Vani et al. [13] were diagnosed more recently and literature shows that AYAs experience more body image concerns when they were on treatment compared to the (first) years after treatment [18,19,40,41]. Furthermore, most improvements in HRQoL and body image occur in the first two years after diagnosis and remain relatively stable thereafter [42,43]. This might explain the lack of an association between time since diagnosis and body image in this study, as we only focused on long-term survivors (5–20 years later).

Most literature shows that female (AYA) patients and survivors are more likely to have a negative body image compared to males [13,17,19,44]. This is in line with our results, which show that females are more likely to experience a negative body image. According to Zucchetti et al. [19], female survivors report more fears of gaining weight and worries related to their physical appearance than males. Also, according to DeFrank et al. [43] female patients place more emphasis on appearance and sexual-related side effects than male patients.

In addition, in line with Vani et al. [13] who reported body changes reduced AYAs sexual attractiveness, our study shows a negative body image was associated with feeling sexually unattractive. This is supported by the study of Graugaard et al. [44], which showed that the risk of body image problems and attractiveness issues increased when sexual problems were present.

Similar to other studies [15,43,44], our findings show that a negative body image is associated with tumor type. This association might be explained by the unique treatments and subsequent side effects that come with various types of cancer [43,44]. For some cancers, like breast cancer and melanomas, physical alterations may be more visible and thus more disturbing [43,44]. Our study shows that breast, female genitalia, and germ cell tumor survivors were more at risk for a negative body image than melanoma survivors. When cancer affected the breast or reproductive organs, the AYA survivors might feel less attractive or less feminine/masculine, negatively affecting their body image [45,46]. Furthermore, it could be hypothesized that body image (and sexual attractiveness) are affected by the changed hormone (estrogen or testosterone) levels due to cancer treatment, especially in cancer of the reproductive organs [46,47,48]. Although in line with most studies, our results are in incongruence with the findings of Graugaard et al. [44], showing genital cancer patients were significantly less at risk for a negative body image than melanoma patients. A possible explanation for this difference is that Graugaard et al. [44] pooled gender together for cancer of the genitalia and we included a wider range of cancer types.

The association between higher tumor stages and a negative body image was also found in other studies and might relate to patients with advanced tumors (larger size or higher stage) often undergoing more invasive or multimodal treatments and being more predisposed to visible scarring or disfigurement [43,49,50]. Furthermore, it is not entirely surprising to find a negative body image associated with BMI and maladaptive coping styles, since these associations were also found in the general population [50,51,52,53,54]. Overweight and obese individuals often report a negative body image and have more weight and shape concerns than individuals with a normal weight [55]. Individuals who are using more maladaptive coping styles, such as avoidant coping, are more likely to have a negative body image and believe their personal worth is influenced by their physical appearance [51]. Although these associations are most likely to be not specific to the cancer population, this does suggest that AYA survivors with a higher BMI or maladaptive coping styles are more at risk for having a negative body image. Consistent with previous findings relationship status, level of education, age at questionnaire, and time since diagnosis were not associated with a negative body image [17,26,40,43,44,56]. Although having a partner is not associated with body image, according to Kowalczyk et al. [47] the relationship quality and (partner) support level might be associated with a better body image. Furthermore, in contrast to previous studies, our study showed no association between the level of physical activity and body image [13,26]. This difference may have been caused by the high reported levels of physical activity in our study which are potentially caused by an overestimation of reality [57]. Although the level of physical activity might be overestimated due to a measurement error, it did give the opportunity to rank AYA survivors according to physical activity level [57,58].

In contrast to others reporting no association between treatments and body image [43,56,59], we found an association between a negative body image and chemotherapy. Although chemotherapy is known to cause side effects such as hair loss, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction, our study showed that AYA survivors who received chemotherapy were less likely to experience a negative body image a long time after diagnosis [43]. Chemotherapy side effects are mostly temporary and it could be hypothesized that AYA survivors who received chemotherapy might have received less invasive surgeries [43].

Considering the limited amount of (quantitative) data available on body image among AYA survivors, this study provides an important contribution and insight into the long-term impact of cancer and several related factors with a negative body image. Another strength of this study is the population-based design including a large number of patients. Furthermore, participants could complete the questionnaires when, where, and how (online or on paper) they wanted. Although the item on dissatisfaction with scars was not applicable for some AYA survivors, the sensitivity analysis showed that this item did not change the measured concept of body image, since the same associated factors were identified through both models.

The present study has also some limitations that should be mentioned. Since the clinical data were collected through the NCR, we only have information on the primary diagnosis and treatment up to one year after diagnosis. Therefore, it is unknown whether survivors received other treatments in the 5–20 years after diagnosis which could affect body image outcomes. Over time treatments and surgical techniques have been improved and some became less invasive. However, in this study, we were not able to look at these differences over time since the data of the NCR are not detailed enough. Furthermore, we were only able to provide general information on treatments, instead of looking at details (such as the type of stem cell transplantation or included reconstructive surgeries). The effect of immunotherapy on body image among AYA survivors also remains unknown because we were not able to include this relatively new form of therapy in our analysis. Since immunotherapy is often used in current cancer treatments of AYAs, it is important to include this in future research. In addition, the cross-sectional design limits the determination of causality. Since we used secondary data from the SURVAYA study, body image was measured with items from the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-SURV100 which are cancer-generic instruments. There are several measurement tools, such as the body image scale (BIS), developed and validated more specifically for measuring the concept of body image among cancer patients [18,60,61]. However, the content of the items of the QLQ-SURV100 was comparable to the BIS items. The cancer-generic tools made it impossible to compare our data on the prevalence of body image problems to the general population, leaving it unknown whether part of the body image problems might be caused by the specific life stage of AYAs. More general limitations of the SURVAYA study have previously been described [25].

5. Implications for Clinical Practice and Future Research

Overall, this study highlights the need for healthcare professionals to open the dialogue on body image and address body image as a standard topic in AYA survivorship care [13]. Since many long-term effects can be mitigated through targeted surveillance and early intervention, healthcare professionals who provide (multidisciplinary) age-specific AYA care play a key role in the early identification and intervention of body image problems [13,19,43,62]. The results of this study can help healthcare professionals identify which AYA survivors are more at risk for having a negative body image and can help to start discussing body image with AYA survivors. Furthermore, the AYA Healthcare Network has developed several tools contributing to the provision of age-specific care, including an anamnesis tool based on the self-identified needs to facilitate conversations between healthcare professionals and AYAs [63]. One of the themes in this anamnesis is body image [63]. The AYA anamnesis is currently implemented in all centers providing age-specific care in the Netherlands [63]. When body image problems are identified, healthcare professionals could provide tips and resources for managing body changes, and can help AYA survivors by strengthening their self-image and recommending appropriate interventions to improve their body image [13,19,40,43].

Given the complexity of body image, it is important that those interventions meet the AYA survivors’ individual needs and (age-specific) preferences [13,64]. AYAs should be encouraged to engage with supportive others (such as family, partner, or other cancer survivors) about their body experiences [40,65]. Furthermore, in the literature, different types of pre-post intervention/programs are described that have positive outcomes on the body image of AYA patients: individual/group interventions, in-person/online, and with single/multiple sessions, focusing on body image alone or as part of an intervention for different psychosocial issues (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy or psycho-education) [13,38,64,65].

Future research with longitudinal designs could allow us to assess experienced body image over time to determine the best time to intervene for those AYA survivors with a negative body image. Furthermore, available interventions for AYA patients should be validated among AYA survivors or adapted when needed [11,13].

6. Conclusions

A negative body image can be a long-term issue for AYA cancer survivors, specifically for females, those with a higher BMI or tumor stage, and those diagnosed with breast cancer, cancer of the female genitalia, or germ cell tumors. Also, AYA survivors who did not undergo chemotherapy, who use more maladaptive coping strategies, who feel sexually unattractive, or who have lower HRQoL are more likely to experience long-term body image problems. Healthcare professionals who provide (multidisciplinary) age-specific AYA care play a key role in the early identification and intervention of body image problems. Raising awareness and integrating supportive care for those who experience a negative body image into standard AYA survivorship care is warranted. Additionally, further (longitudinal) research could help to improve age-specific care for AYA survivors focusing on body image.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the patients for their participation in the study and the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

Appendix A

A sensitivity analyses was conducted to explore the effect of the item on scars (this item was not applicable to everyone). Table A1 shows the characteristics of the AYA survivors and Table A2 shows the univariable and multivariable logistic regression when the item on scars is left out.

Table A1.

Characteristics of AYA survivors with and without the item on dissatisfaction with scar.

| Population Characteristics | With Item on Scar 1 | Without Item on Scar 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| with a Negative Body Image |

without a Negative Body Image |

with a Negative Body Image |

without a Negative Body Image |

||||||

| n = 541 | n = 3194 | n = 548 | n = 3187 | ||||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age at questionnaire—Mean (SD) | 44.2 (7.3) | 44.6 (7.5) | 44.4 (7.3) | 44.5 (7.5) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 94 | 6.5 | 1362 | 93.5 | 93 | 6.4 | 1363 | 93.6 |

| Female | 447 | 19.6 | 1832 | 80.4 | 455 | 20.0 | 1824 | 80.0 | |

| Partner (yes) | 395 | 12.7 | 2710 | 87.3 | 400 | 12.9 | 2705 | 87.1 | |

| Level of education | Low | 6 | 25.0 | 18 | 75.0 | 6 | 25.0 | 18 | 75.0 |

| Intermediate | 277 | 17.3 | 1322 | 82.7 | 271 | 16.9 | 1328 | 83.1 | |

| High | 257 | 12.2 | 1847 | 87.8 | 270 | 12.8 | 1834 | 87.2 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Age at diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 31.9 (5.8) | 31.5 (5.9) | 32.1 (5.8) | 31.5 (5.9) | |||||

| Type of Cancer | Melanoma | 18 | 7.0 | 240 | 93.0 | 20 | 7.8 | 238 | 92.2 |

| Head and neck | 12 | 10.4 | 103 | 89.6 | 10 | 8.7 | 105 | 91.3 | |

| Colon and rectal | 8 | 10.5 | 68 | 89.5 | 7 | 9.2 | 69 | 90.8 | |

| Digestive tract other 3 | 6 | 20.0 | 24 | 80.0 | 6 | 20.0 | 24 | 80.0 | |

| Breast | 191 | 21.6 | 694 | 78.4 | 191 | 21.6 | 694 | 78.4 | |

| Female genitalia | 92 | 22.6 | 315 | 77.4 | 94 | 23.1 | 313 | 76.9 | |

| Thyroid gland | 26 | 11.4 | 202 | 88.6 | 28 | 12.3 | 200 | 87.7 | |

| Central nervous system | 22 | 15.5 | 120 | 84.5 | 21 | 14.8 | 121 | 85.2 | |

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 20 | 12.1 | 145 | 87.9 | 19 | 11.5 | 146 | 88.5 | |

| Germ cell tumor | 38 | 5.8 | 615 | 94.2 | 37 | 5.7 | 616 | 94.3 | |

| Lymphoid hematological malignancies | 76 | 13.7 | 479 | 86.3 | 82 | 14.8 | 473 | 85.2 | |

| Myeloid hematological malignancies | 21 | 15.0 | 119 | 85.0 | 23 | 16.4 | 117 | 85.2 | |

| Other 4 | 11 | 13.6 | 70 | 86.4 | 10 | 12.3 | 71 | 87.7 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 190 | 11.9 | 1405 | 88.1 | 194 | 12.2 | 1401 | 87.8 |

| II | 174 | 17.6 | 817 | 82.4 | 182 | 18.4 | 809 | 81.6 | |

| III | 87 | 16.3 | 448 | 83.7 | 81 | 15.1 | 454 | 84.9 | |

| IV | 28 | 16.4 | 143 | 83.6 | 29 | 17.0 | 142 | 83.0 | |

| Unknown | 62 | 14.0 | 381 | 86.0 | 62 | 14.0 | 381 | 86.0 | |

| Treatments 5 | Surgery organ (yes) | 368 | 14.8 | 2115 | 85.2 | 367 | 14.8 | 2116 | 85.2 |

| Surgery local (yes) | 69 | 12.8 | 468 | 87.2 | 71 | 13.2 | 466 | 86.8 | |

| Chemotherapy (yes) | 342 | 16.3 | 1762 | 83.7 | 348 | 16.5 | 1756 | 83.5 | |

| Radiotherapy (yes) 6 | 299 | 16.8 | 1480 | 83.2 | 306 | 17.2 | 1473 | 82.8 | |

| Hormone therapy (yes) | 113 | 24.8 | 342 | 75.2 | 113 | 24.8 | 342 | 75.2 | |

| Targeted therapy (yes) | 53 | 18.3 | 236 | 81.7 | 53 | 18.3 | 236 | 81.7 | |

| Stem cell transplantation (yes) | 15 | 11.1 | 120 | 88.9 | 15 | 11.1 | 120 | 88.9 | |

| Time since diagnosis—Mean (SD) | 11.8 (4.5) | 12.6 (4.5) | 11.7 (4.5) | 12.6 (4.5) | |||||

| <10 years | 223 | 17.5 | 1051 | 82.5 | 223 | 17.5 | 1051 | 82.5 | |

| 10–15 years | 171 | 13.1 | 1136 | 86.9 | 178 | 13.6 | 1129 | 86.4 | |

| >15 years | 147 | 12.7 | 1007 | 87.3 | 147 | 12.7 | 1007 | 87.3 | |

| Physical activity | Time in hours/week—Mean (SD) | 30.1 (26.3) | 27.5 (24.8) | 30.5 (26.6) | 27.5 (24.8) | ||||

| In MET hours/week—Mean (SD) | 114.1 (96.5) | 107.6 (91.4) | 115.4 (97.4) | 107.4 (91.2) | |||||

| BMI—Mean (SD) | 26.9 (5.9) | 24.9 (4.0) | 26.9 (6.0) | 24.9 (4.0) | |||||

| Underweight | 11 | 19.0 | 47 | 81.0 | 11 | 19.0 | 47 | 81.0 | |

| Normal weight | 224 | 11.2 | 1777 | 88.8 | 227 | 11.3 | 1774 | 88.7 | |

| Overweight | 167 | 13.7 | 1050 | 86.3 | 170 | 14.0 | 1047 | 86.0 | |

| Obesity | 136 | 31.3 | 299 | 68.7 | 137 | 31.5 | 298 | 68.5 | |

| Psychosocial characteristics | |||||||||

| Coping style | Adaptive—Mean (SD) | 30.0 (7.1) | 29.1 (7.5) | 30.0 (7.2) | 29.1 (7.5) | ||||

| Maladaptive—Mean (SD) | 15.7 (4.6) | 12.8 (3.5) | 15.7 (4.5) | 12.7 (3.5) | |||||

| HRQoL | Physical functioning—Mean (SD) | 80.5 (18.8) | 93.3 (12.1) | 80.4 (19.1) | 93.4 (12.0) | ||||

| Role functioning—Mean (SD) | 59.7 (32.1) | 87.2 (21.7) | 59.6 (32.6) | 87.3 (21.5) | |||||

| Emotional functioning– Mean (SD) | 57.9 (24.1) | 83.1 (17.5) | 57.2 (24.0) | 83.3 (17.3) | |||||

| Cognitive functioning—Mean (SD) | 57.7 (28.5) | 81.3 (21.9) | 57.2 (28.1) | 81.5 (21.9) | |||||

| Social functioning—Mean (SD) | 66.3 (31.1) | 91.6 (17.7) | 65.8 (31.0) | 91.7 (17.5) | |||||

| Global health status—Mean (SD) | 59.2 (19.8) | 77.9 (15.6) | 59.0 (19.7) | 78.0 (15.5) | |||||

| Sexual attractiveness (yes) | 497 | 18.6 | 2203 | 81.4 | 501 | 18.6 | 2199 | 81.4 | |

1 Descriptive statistics on body image when the item on dissatisfaction with scar is included. 2 Descriptive statistics on body image when the item on dissatisfaction with scar is left out. 3 Digestive tract and other includes the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. 4 Other includes respiratory, male genitalia (penis, prostate), urinary tract, tumor with other localizations, endocrine glands, eye, neuroblastoma, paraganglioma. 5 The treatments are received at primary diagnosis. 6 Radiotherapy includes radiotherapy for primary tumor and metastases at primary diagnosis. n = number of AYA survivors, Mean (SD) = mean and standard deviation.

Table A2.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression without item on dissatisfaction with scar.

| Population Characteristics | Univariable Logistic Regression 1 | Multivariable Logistic Regression 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 = 1167.91 (p-Value < 0.001) Nagelkerke R2 = 0.47 | |||||

| OR [95%CI] | p-Value | OR [95%CI] | p-Value | ||

| Age at questionnaire | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | 0.633 | |||

| Gender | Male | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 3.66 [2.89–4.62] | <0.001 | 4.07 [2.66–6.23] | <0.001 | |

| Partner | Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 2.06 [1.66–2.55] | <0.001 | 1.18 [0.88–1.59] | 0.272 | |

| Level of education | Low | 2.26 [0.89–5.75] | 0.086 | 1.79 [0.39–8.19] | 0.452 |

| Medium | 1.39 [1.16–1.66] | <0.001 | 0.98 [0.77–1.25] | 0.869 | |

| High | Reference | Reference | |||

| Type of cancer | Melanoma | Reference | Reference | ||

| Head and neck | 1.13 [0.51–2.51] | 0.757 | 0.99 [0.37–2.65] | 0.977 | |

| Digestive tract other 3 | 2.98 [1.09–8.12] | 0.033 | 3.07 [0.76–12.39] | 0.115 | |

| Colon and rectal | 1.21 [0.41–2.97] | 0.682 | 0.61 [0.19–1.97] | 0.409 | |

| Breast | 3.28 [2.02–5.31] | <0.001 | 1.88 [0.91–3.90] | 0.091 | |

| Female genitalia | 3.57 [2.14–5.96] | <0.001 | 2.64 [1.36–5.14] | 0.004 | |

| Thyroid gland | 1.67 [0.91–3.05] | 0.098 | 0.66 [0.30–1.48] | 0.311 | |

| Central nervous system | 2.07 [1.08–3.96] | 0.029 | 0.76 [0.24–2.34] | 0.627 | |

| Bone and soft tissue sarcoma | 1.55 [0.80–3.00] | 0.195 | 1.28 [0.54–3.02] | 0.577 | |

| Germ cell tumor | 0.72 [0.41–1.26] | 0.243 | 2.05 [0.92–4.60] | 0.080 | |

| Lymphoid hematological malignancies | 2.06 [1.24–3.45] | 0.006 | 1.92 [0.91– 4.03] | 0.087 | |

| Myeloid hematological malignancies | 2.34 [1.24–4.43] | 0.009 | 2.03 [0.68–6.06] | 0.207 | |

| Other 4 | 1.68 [0.75–3.75] | 0.208 | 0.80 [0.28–2.30] | 0.682 | |

| Tumor stage | I | Reference | Reference | ||

| II | 1.63 [1.30–2.02] | <0.001 | 1.57 [1.12–2.21] | 0.009 | |

| III | 1.29 [0.97–1.08] | 0.076 | 1.52 [0.99–2.34] | 0.059 | |

| IV | 1.48 [0.96–2.26] | 0.074 | 1.83 [0.98–3.43] | 0.059 | |

| Missing | 1.18 [0.86–1.60] | 0.304 | 1.19 [0.58–2.44] | 0.631 | |

| Chemotherapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.42 [1.18–1.72] | <0.001 | 0.68 [0.47–0.98] | 0.040 | |

| Radiotherapy 5,6 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.48 [1.23–1.77] | <0.001 | 1.22 [0.92–1.61] | 0.162 | |

| Hormone therapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 2.16 [1.71–2.74] | <0.001 | 1.26 [0.83–1.90] | 0.277 | |

| Targeted therapy 5 | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.34 [0.98–1.83] | 0.067 | 0.92 [0.59–1.42] | 0.695 | |

| Surgery organ 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.03 [0.85–1.25] | 0.771 | |||

| Surgery local 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.87 [0.67–1.14] | 0.308 | |||

| Stem cell transplantation 5 | No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.39 [0.81–2.40] | 0.237 | |||

| Time since diagnosis | <10 years | 1.45 [1.16–1.82] | 0.001 | 1.28 [0.95–1.73] | 0.110 |

| 10–15 years | 1.08 [0.85–1.37] | 0.520 | 1.00 [0.73–1.35] | 0.983 | |

| >15 years | Reference | Reference | |||

| Physical activity MET hours/week | 1.00 [1.00–1.00] | 0.063 | 1.00 [1.00–1.00] | 0.099 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 1.83 [0.94–3.58] | 0.078 | 0.71 [0.28–1.75] | 0.453 |

| Normal weight | Reference | Reference | |||

| Overweight | 1.27 [1.03–1.57] | 0.028 | 1.79 [1.36–2.37] | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | 3.59 [2.81–4.59] | <0.001 | 3.82 [2.74–5.33] | <0.001 | |

| Maladaptive coping style | 1.19 [1.17–1.22] | <0.001 | 1.09 [1.06–1.13] | <0.001 | |

| HRQoL | Physical functioning | 0.95 [0.95–0.96] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.98–1.00] | 0.146 |

| Role functioning | 0.97 [0.96–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.99–1.00] | 0.045 | |

| Emotional functioning | 0.95 [0.94–0.95] | <0.001 | 0.97 [0.96–0.98] | <0.001 | |

| Cognitive functioning | 0.97 [0.96–0.97] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.99–1.00] | 0.001 | |

| Social functioning | 0.96 [0.96–0.96] | <0.001 | 0.99 [0.98–0.99] | <0.001 | |

| Global Health status | 0.94 [0.94–0.95] | <0.001 | 0.98 [0.97–0.99] | <0.001 | |

| Sexual attractiveness | No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 5.16 [3.75–7.11] | <0.001 | 3.39 [2.29–5.01] | <0.001 | |

1 Univariable: p-value < 0.1 is included in multivariable analyses. 2 Multivariable: p-value < 0.05 is significant (bold p-values show a statistically significant OR). The multivariable model showed no multicollinearity. 3 Digestive tract and other includes the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine. 4 Other includes respiratory, male genitalia (penis, prostate), urinary tract, tumor with other localizations, endocrine glands, eye, neuroblastoma, paraganglioma. 5 The treatments were received at primary diagnosis. 6 Radiotherapy includes radiotherapy for primary tumor and metastases at primary diagnosis. OR [95%CI] = odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.H.S., C.V., W.T.A.v.d.G. and O.H.; methodology, L.M.H.S., C.V., W.T.A.v.d.G. and O.H.; software, C.V.; validation, L.M.H.S., C.V. and O.H.; formal analysis, L.M.H.S.; investigation, C.V., R.M.B., T.v.d.H., M.C.M.K., S.E.J.K., J.M.T., M.E.M.M.B., R.I.L., J.N. and O.H.; resources, C.V.; data curation, L.M.H.S. and C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.H.S. and O.H.; writing—review and editing, C.V., R.M.B., T.v.d.H., M.C.M.K., S.E.J.K., J.M.T., M.E.M.M.B., R.I.L., J.N., W.T.A.v.d.G. and O.H.; visualization, L.M.H.S. and O.H.; supervision, O.H.; project administration, L.M.H.S., C.V. and O.H.; funding acquisition, W.T.A.v.d.G. and O.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The SURVAYA study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Netherlands Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board (IRBIRBd18122) on 6 February 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the SURVAYA study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding agencies had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the paper; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Funding Statement

C.V. is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (#11788 COMPRAYA study). O.H. is supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research VIDI grant (198.007). Data collection of the SURVAYA study was partly supported by the investment grant (#480-08-009) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Integraal Kankercentrum Nederland (IKNL) Cijfers over Kanker. [(accessed on 19 October 2021)]. Available online: http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl.

- 2.Meeneghan M.R., Wood W.A. Challenges for Cancer Care Delivery to Adolescents and Young Adults: Present and Future. Acta Heamatol. 2014;132:414–422. doi: 10.1159/000360241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sodergren S.C., Husson O., Robinson J., Rohde G.E., Tomaszewska I.M., Vivat B., Dyar R., Darlington A.S. Systematic Review of the Health-Related Quality of Life Issues Facing Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2017;26:1659–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinn G., Goncalves V., Sehovic I., Bowman M., Reed D. Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2015;6:19. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S51658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis D.R., Seibel N.L., Smith A.W., Stedman M.R. Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monographs. 2014;49:228–235. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan V., Krull K., Gurney J., Leisenring W., Robison L., Ness K. Predictors of Future Health-Related Quality of Life in Survivors of Adolescent Cancer. Pediatr. Blood. Cancer. 2014;61:1891–1894. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barakat L.P., Galtieri L.R., Szalda D., Schwartz L.A. Assessing the Psychosocial Needs and Program Preferences of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Support. Care Cancer. 2016;24:823–832. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2849-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Agostino N.M., Penney A., Zebrack B. Providing Developmentally Appropriate Psychosocial Care to Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:2329–2334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husson O., Prins J.B., Kaal S.E.J., Oerlemans S., Stevens W.B., Zebrack B., van der Graaf W.T.A., van de Poll-Franse L.V. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Lymphoma Survivors Report Lower Health-Related Quality of Life Compared to a Normative Population: Results from the PROFILES Registry. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:288–294. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1267404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zebrack B.J. Psychological, Social, and Behavioral Issues for Young Adults with Cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:2289–2294. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellizzi K.M., Smith A., Schmidt S., Keegan T.H.M., Zebrack B., Lynch C.F., Deapen D., Shnorhavorian M., Tompkins B.J., Simon M. Positive and Negative Psychosocial Impact of Being Diagnosed with Cancer as an Adolescent or Young Adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–5162. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Meer D., Karim-Kos H.E., van der Mark M., Aben K.K.H., Bijlsma R.M., Rijneveld A.W., van der Graaf W.T.A., Husson O. Incidence, Survival, and Mortality Trends of Cancers Diagnosed in Adolescents and Young Adults (15-39 Years): A Population-Based Study in The Netherlands 1990–2016. Cancers. 2020;12:3421. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vani M.F., Lucibello K.M., Trinh L., Santa Mina D., Sabiston C.M. Body Image among Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed with Cancer: A Scoping Review. Psycho-Oncology. 2021;30:1278–1293. doi: 10.1002/pon.5698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van De Poll-Franse L., Horevoorts N., Van Eenbergen M., Denollet J., Roukema J.A., Aaronson N.K., Vingerhoets A., Coebergh J.W., De Vries J., Essink-Bot M.L., et al. The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial Treatment and Long Term Evaluation of Survivorship Registry: Scope, Rationale and Design of an Infrastructure for the Study of Physical and Psychosocial Outcomes in Cancer Survivorship Cohorts. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47:2188–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Leeuwen M., Husson O., Alberti P., Arraras J.I., Chinot O.L., Costantini A., Darlington A.S., Dirven L., Eichler M., Hammerlid E.B., et al. Understanding the Quality of Life (QOL) Issues in Survivors of Cancer: Towards the Development of an EORTC QOL Cancer Survivorship Questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2018;16:114. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0920-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopwood P., Hopwood N. New Challenges in Psycho-Oncology: An Embodied Approach to Body Image. Psycho-Oncology. 2019;28:211–218. doi: 10.1002/pon.4936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan S.Y., Eiser C. Body Image of Children and Adolescents with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Body Image. 2009;6:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehmann V., Hagedoorn M., Tuinman M.A. Body Image in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review of Case-Control Studies. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0414-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zucchetti G., Bellini S., Bertolotti M., Bona F., Biasin E., Bertorello N., Tirtei E., Fagioli F. Body Image Discomfort of Adolescent and Young Adult Hematologic Cancer Survivors. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6:377–380. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sodergren S.C., Husson O., Rohde G.E., Tomasewska I.M., Vivat B., Yarom N., Griffiths H., Darlington A.S. A Life Put on Pause: An Exploration of the Health-Related Quality of Life Issues Relevant to Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7:453–464. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore J.B., Canzona M.R., Puccinelli-Ortega N., Little-Greene D., Duckworth K.E., Fingeret M.C., Ip E.H., Sanford S.D., Salsman J.M. A Qualitative Assessment of Body Image in Adolescents and Young Adults (AYAs) with Cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2021;30:614–622. doi: 10.1002/pon.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brierley M.E.E., Sansom-Daly U.M., Baenziger J., McGill B., Wakefield C.E. Impact of Physical Appearance Changes Reported by Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Analysis. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2019;28:e13052. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larouche S.S., Chin-Peuckert L. Changes in Body Image Experienced by Adolescents with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2006;23:200–209. doi: 10.1177/1043454206289756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattson E., Ringnér A., Ljungman G., von Essen L. Positive and Negative Consequences with Regard to Cancer during Adolescence. Experiences Two Years after Diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:1003–1009. doi: 10.1002/pon.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vlooswijk C., Van De Poll-franse L.V., Janssen S.H.M., Derksen E., Reuvers M.J.P., Bijlsma R., Kaal S.E.J., Kerst J.M., Tromp J.M., Bos M.E.M.M., et al. Recruiting Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors for Patient-Reported Outcome Research: Experiences and Sample Characteristics of the SURVAYA Study. Curr. Oncol. 2022;29:5407–5425. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29080428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson M., Enskär K., Steineck G., Wilderäng U., Jarfelt M. Self-Perceived Physical Attractiveness in Relation to Scars among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Population-Based Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018;7:358–366. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2017.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson I.B., Cleary P.D. Linking Clinical Variables With Health-Related Quality of Life. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrans C.E., Zerwic J.J., Wilbur J.E., Larson J.L. Conceptual Model of Health-Related Quality of Life. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2005;37:336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pols M.A., Peeters P.H.M., Ocké M.C., Slimani N., Bueno-De-Mesquita H.B., Collette H.J.A. Estimation of Reproducibility and Relative Validity of the Questions Included in the EPIC Physical Activity Questionnaire. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997;26:S181–S189. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.S181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ainsworth B.E., Haskell W.L., Whitt M.C., Irwin M.L., Swartz A.M., Strath S.J., O’Brien W.L., Bassett J., Schmitz K.H., Emplaincourt P.O., et al. Compendium of Physical Activities: An Update of Activity Codes and MET Intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weir C., Jan A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garnefski N., Kraaij V. The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Psychometric Features and Prospective Relationships with Depression and Anxiety in Adults. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2007;23:141–149. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.23.3.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garnefski N., Kraaij V. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire—Development of a Short 18-Item Version (CERQ-Short) Pers. Individ. Differ. 2006;41:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betegón E., Rodríguez-Medina J., Del-Valle M., Irurtia M.J. Emotion Regulation in Adolescents: Evidence of the Validity and Factor Structure of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) Int. J. Environ. Res. 2022;19:362. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aaronson N.K., Ahmedzai S., Bergman B., Bullinger M., Cull A., Duez N.J., Filiberti A., Flechtner H., Fleishman S.B., de Haes J.C.J.M., et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A Quality-of-Life Instrument for Use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. JNCI. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Leeuwen M., Kieffer J.M., Young T.E., Annunziata M.A., Arndt V., Arraras J.I., Autran D., Hani H.B., Chakrabarti M., Chinot O., et al. Phase III Study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Cancer Survivorship Core Questionnaire. J. Cancer Surviv. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fayers P., Aaronson N., Bjordal K., Groenvold M., Curran D., Bottomley A. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; Brussels, Belgium: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fingeret M.C., Teo I., Epner D.E. Managing Body Image Difficulties of Adult Cancer Patients: Lessons from Available Research. Cancer. 2014;120:633–641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thakur M., Sharma R., Mishra A., Gupta B. Body Image Disturbances among Breast Cancer Survivors: A Narrative Review of Prevalence and Correlates. Cancer Res. Stat. Trea. 2022;5:90–96. doi: 10.4103/crst.crst_170_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vani M.F., Sabiston C.M., Petrella A., Adams S.C., Eaton G., Chalifour K., Garland S.N. Body Image Concerns of Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Brief Report. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2021;39:673–679. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2020.1815926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker P.A., Youssef A., Walker S., Basen-Engquist K., Cohen L., Gritz E.R., Wei Q.X., Robb G.L. Short-Term and Long-Term Psychosocial Adjustment and Quality of Life in Women Undergoing Different Surgical Procedures for Breast Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2007;14:3078–3089. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Husson O., Zebrack B.J., Block R., Embry L., Aguilar C., Hayes-Lattin B., Cole S. Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:652–659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.7946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeFrank J.T., Mehta C.C.B., Stein K.D., Baker F. Body Image Dissatisfaction in Cancer Survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2007;34:625. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.E36-E41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graugaard C., Sperling C.D., Hølge-Hazelton B., Boisen K.A., Petersen G.S. Sexual and Romantic Challenges among Young Danes Diagnosed with Cancer: Results from a Cross-Sectional Nationwide Questionnaire Study. Psycho-Oncology. 2018;27:1608–1614. doi: 10.1002/pon.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brederecke J., Heise A., Zimmermann T. Body Image in Patients with Different Types of Cancer. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0260602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carpentier M.Y., Fortenberry J.D. Romantic and Sexual Relationships, Body Image, and Fertility in Adolescent and Young Adult Testicular Cancer Survivors: A Review of the Literature. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;47:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kowalczyk R., Nowosielski K., Cedrych I., Krzystanek M., Glogowska I., Streb J., Kucharz J., Lew-Starowicz Z. Factors Affecting Sexual Function and Body Image of Early-Stage Breast Cancer Survivors in Poland: A Short-Term Observation. Clin. Breast Cancer. 2019;19:e30–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whicker M., Black J., Altwerger G., Menderes G., Feinberg J., Ratner E. Management of Sexuality, Intimacy, and Menopause Symptoms in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;217:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Härtl K., Janni W., Kästner R., Sommer H., Strobl B., Rack B., Stauber M. Impact of Medical and Demographic Factors on Long-Term Quality of Life Image of Breast Cancer Patients. Ann. Oncol. 2003;14:1064–1071. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manier K.K., Rowe L.S., Welsh J., Armstrong T.S. The Impact and Incidence of Altered Body Image in Patients with Head and Neck Tumors: A Systematic Review. Neurooncol. Pract. 2018;5:204–213. doi: 10.1093/nop/npy018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cash T.F., Santos M.T., Williams E.F. Coping with Body-Image Threats and Challenges: Validation of the Body Image Coping Strategies Inventory. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005;58:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen J. Eating Disorders and Obesity. The Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2002. Obesity and Body Image; pp. 399–402. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melnyk S.E., Cash T.F., Janda L.H. Body Image Ups and Downs: Prediction of Intra-Individual Level and Variability of Women’s Daily Body Image Experiences. Body Image. 2004;1:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrari E.P., Petroski E.L., Silva D.A.S. Prevalence of Body Image Dissatisfaction and Associated Factors among Physical Education Students. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013;35:119–127. doi: 10.1590/S2237-60892013000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahadzadeh A.S., Rafik-Galea S., Alavi M., Amini M. Relationship between Body Mass Index, Body Image, and Fear of Negative Evaluation: Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Health Psychol. Open. 2018;5 doi: 10.1177/2055102918774251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bahrami M., Mohamadirizi M., Mohamadirizi S., Hosseini S. Evaluation of Body Image in Cancer Patients and Its Association with Clinical Variables. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017;6:81. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_4_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steene-johannessen J., Anderssen S.A., Ploeg H.P. Van Der Are Self-Report Measures Able to Define Individuals as Physically Active or Inactive? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016;48:235–244. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cust A.E., Smith B.J., Chau J., van der Ploeg H.P., Friedenreich C.M., Armstrong B.K., Bauman A. Validity and Repeatability of the EPIC Physical Activity Questionnaire: A Validation Study Using Accelerometers as an Objective Measure. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rossen P., Pedersen A.F., Zachariae R., Von Der Maase H. Sexuality and Body Image in Long-Term Survivors of Testicular Cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paterson C.L., Lengacher C.A., Donovan K.A., Kip K.E., Tofthagen C.S. Body Image in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:E39–E58. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hopwood P., Fletcher I., Lee A., Al Ghazal S. A Body Image Scale for Use with Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Cancer. 2001;37:189–197. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett M., McDonnell G., DeRosa A., Schuler T., Philip E., Peterson L., Touza K., Jhanwar S., Atkinson T.M., Ford J.S. Psychosocial Outcomes and Interventions among Cancer Survivors Diagnosed during Adolescence and Young Adulthood (AYA): A Systematic Review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:814–831. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0527-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.AYA Zorgnetwerk Nationaal AYA “Jong En Kanker” Zorgnetwerk. [(accessed on 13 October 2022)]. Available online: https://ayazorgnetwerk.nl/

- 64.Sebri V., Durosini I., Triberti S., Pravettoni G. The Efficacy of Psychological Intervention on Body Image in Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Systematic-Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021;12:611954. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.611954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Penn A., Kuperberg A. Psychosocial Support in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Cancer J. 2018;24:321–327. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.