Abstract

Host genetics play an important role in determining resistance or susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis. While specific immunity appears to regulate disease resolution, innate immunity appears to regulate disease severity. Intradermal infection with Borrelia burgdorferi yields severe arthritis in C3H/He (C3H) mice but only minimal arthritis in BALB/c mice. Intradermal infection of immunodeficient C3H SCID mice also results in severe arthritis, but arthritis of only moderate severity in BALB/c SCID mice. In the present study, we examined immunodeficient recombinase-activating gene-knockout (RAG-1−/−) (RAG−) mice from resistant C57BL/6 (B6) and DBA/2 (DBA) mouse strains. B. burgdorferi-infected B6 RAG− and DBA RAG− mice had little or no ankle swelling, a low occurrence of inflammatory infiltrates in tibiotarsal joints, and low arthritis severity scores in comparison to RAG+ and RAG− BALB/c or C3H mice. Few differences in spirochete DNA levels in ankles of resistant and susceptible RAG− mice were seen. These data suggest that resistance to arthritis development following B. burgdorferi infection is not necessarily dependent on an acquired immune response and can occur despite the presence of high spirochete burden. Thus, genes expressed outside the specific immune response can be central regulators of experimental arthritis.

Experimental Lyme borreliosis in mice partially recapitulates the disease spectrum seen in humans after infection with Borrelia burgdorferi (4). After inoculation of mice with B. burgdorferi, spirochetes disseminate and can be recovered from many tissues, including the urinary bladder, skin, and heart (5). The arthritis which develops acutely is characterized by inflammatory infiltrates (predominantly neutrophils and monocytes), tendonitis, synovitis, and synovial hypertrophy (7). Both spirochete and host factors control the degree of pathology which develops in infected animals. C3H/He (C3H) mice develop a transient arthritis which peaks within 21 days and then resolves (4). Arthritis development in BALB/c mice is variable and correlates with the numbers of spirochetes present within the joint (28). BALB/c mice are resistant to arthritis development when infected with 200 B. burgdorferi but develop arthritis of greater severity as the infectious dose is increased (18). In contrast, C57BL/6 (B6) mice remain resistant to arthritis development even in the presence of high infectious doses (18). Thus, host genetics are critical in determining the extent of the pathology which develops during experimental Lyme borreliosis.

Resistance to the development of experimental Lyme arthritis or its resolution appears to involve components of the adaptive immune response. Passive transfer of immune sera or the transfer of B and T cells (but not T cells alone) causes regression of arthritis in SCID mice, suggesting the importance of antibodies in disease resolution (9, 10). Similarly, the transfer of presensitized spleen cells but not T cells alone can protect SCID mice from challenge; the transfer of B cells confers only partial protection (24). T cells may also influence the response to Borrelia through the production of inflammatory cytokines. Th1 responses promote an inflammatory response that may exacerbate arthritis development because the administration of anti-interleukin 12 (IL-12) or anti-gamma interferon antibodies reduces arthritis severity in susceptible animals (2, 16, 19). Th2 responses may protect against arthritis development since treatment of resistant mice with anti-IL-4 increases arthritis severity (16, 19) and treatment of susceptible mice with rIL-4 or passive transfer of a CD4+ Th2 clone reduces development of arthritis (17, 20). In contrast, an adaptive immune response is not required for susceptibility to development of experimental Lyme arthritis (6, 22, 23). SCID mice from a genetically resistant BALB/c background are unable to control infection and develop a progressive, unremitting arthritis. Innate immunity in immunodeficient animals, however, does appear to provide some control over disease severity. Arthritis severity in C3H SCID mice was more severe than that which developed in BALB/c SCID mice (6). Antibody depletion of IL-12 causes an increase in arthritis severity in C3H SCID mice but a reduction of arthritis severity in normal C3H mice (2, 3). The extent of protection against arthritis development provided by the innate immune response in various mouse strains, however, is unknown.

In the present study, we infected immunocompetent (RAG+) and immunodeficient recombinase-activating gene-knockout RAG-1−/− (RAG−) mice on C3H, BALB/c, B6, or DBA/2 (DBA) backgrounds and monitored arthritis development for 21 days. Infection of RAG+ and RAG− C3H or BALB/c mice resulted in the development of severe arthritis. In contrast, infection of RAG+ and RAG− B6 or DBA mice did not result in arthritis development. These data demonstrate that an adaptive immune response is not required for arthritis resistance. Thus, in the absence of specific immunity, other genetic polymorphisms are capable of controlling resistance or susceptibility to B. burgdorferi-induced arthritis in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and infections.

Female C3H, DBA, BALB/c, B6, B6 SCID and B6×129 RAG-1−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). The wild-type mouse strains were made immunodeficient (RAG−) by crossing them to B6×129 RAG-1−/− mice and then backcrossing to the designated background. During the backcross breedings, heterozygous mice were screened by PCR for the presence of the neomycin resistance gene contained in the RAG− cassette. Heterozygous littermates were then intercrossed following the designated number of backcrosses to obtain RAG− animals. C3H RAG− mice were in the fifth backcross to C3H; DBA RAG− mice were in the fifth backcross to DBA; BALB/c RAG− mice were in the eighth backcross to BALB/c; and B6 RAG− mice were in the third backcross to B6 when used in experiments. Genotypes were confirmed by flow cytometry of peripheral blood mononuclear cells using monoclonal antibodies against T cells (anti-CD3) and B cells (anti-B220). All mice were between 4 and 6 weeks of age at the time of infection. B. burgdorferi N40 was kindly provided by Steven Barthold (Yale University, New Haven, Conn.). Spirochetes were reisolated from SCID mice, passaged twice in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly II (BSK) medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and frozen in aliquots at −80°C. For infections, an aliquot was thawed, placed in 7 ml of medium and grown for 5 days at 32°C. Mice were inoculated in both hind footpads with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi in 50 μl of medium. Tibiotarsal joints were measured weekly with a metric caliper (Ralmike’s Tool-A-Rama, South Plainfield, N.J.) through the thickest anteroposterior diameter of the ankle. Blood, heart, spleen, urinary bladder, skin, and ankles were aseptically collected and cultured at 32°C for 14 days in BSK medium. Cultures were scored by placing 10 μl of supernatant on a microscope slide under a cover slip (22 by 22 mm) and examining 20 high-power fields by dark-field microscopy.

Histology.

Mice were sacrificed 21 days following infection; the ankles were washed with 70% ethanol, and the skin was removed. The sample was excised and placed in 10% buffered formalin. The sample was embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Arthritis severity scores were determined in a blinded manner and graded on a scale of 0 to 3 (6). Grade 0 represents no inflammation, grades 1 and 2 represent mild to moderate inflammation, and grade 3 represents severe inflammation. Arthritis was characterized by the infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into the joints, tendons, and ligament sheaths; hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the synovium; and fibrin exudates. Arthritis severity scores were based upon the extent of the observed inflammatory changes.

Competitive PCR.

Ankles were excised by first removing the skin and then cutting just above and below the ankle joint. Ear samples were taken with a 2-mm ear punch. To extract DNA from ankle tissue, samples were digested in 0.5 ml of 1% collagenase for 4 h at 37°C. Following incubation, 0.25 ml of 3× lysis buffer (0.3-mg/ml proteinase K in 600 mM NaCl–60 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]–150 mM EDTA–0.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 16 h at 55°C. The debris was pelleted, and the supernatants were transferred to new tubes. Sample DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The sample DNA was then pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 0.2 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer. Ear punch DNA was extracted by the same procedure but without the collagenase treatment. Competitive PCR was performed using a constant amount (0.25 pg) of the BC3 polycompetitor as previously described (13) and approximately 150 ng of sample DNA. The BC3 polycompetitor consists of a linear DNA molecule containing modified portions of the fla and ospA genes of Borrelia and a modified portion of the mammalian IL4 gene (13). The following sets of primers were used for PCR amplification of both wild-type and BC3 gene segments: ospA 5′ primer TCTTGAAGGAAGTTTAACTGCTG, ospA 3′ primer CAAGTTTTGTAATTTCAACTGCTGA; IL4pr 5′ primer GATCAGCTGGGCTAGGATGCGAGA, IL4pr 3′ primer GGGCCAATCAGCACCTCTCTTCCA. Sample reactions contained 2.5 mM MgCl2. For IL4pr reactions, samples were initially denatured for 60 s, and the cycling parameters thereafter were denaturation at 94°C for 50 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 50 s, for 35 cycles. For ospA amplification, an initial 60-s denaturation step was followed by cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 60 s, annealing at 60°C for 60 s, and extension at 72°C for 90 s, for 45 cycles.

Statistics.

Results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance followed by the Tukey test for multiple comparisons. For significance tests, a level of α = 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

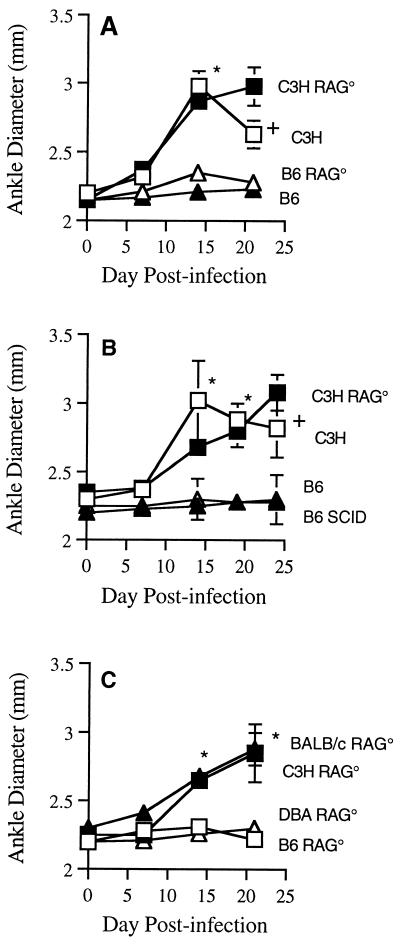

We infected RAG+ and RAG− mice on C3H, B6, BALB/c, or DBA backgrounds and monitored arthritis development for 21 days. Figure 1 shows measurement of ankle diameters for representative mouse strains from three separate experiments. In all experiments, 3 to 5 mice were injected in the hind footpads with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi, and the diameters of tibiotarsal joints were measured weekly. Footpad inoculations were used to deliver the organisms near the joint of interest and to control for possible differences in spirochete dissemination in the different mouse strains. Footpad inoculation of media alone causes no histological changes in the tibiotarsal joints compared with noninjected control mice (12a). We first compared the response of B6 RAG− to that of C3H RAG− mice. RAG+ C3H and B6 were used as susceptible and resistant controls, respectively (Fig. 1A). Ankles from C3H and C3H RAG− mice had significant swelling by day 14 compared to those of B6 or B6 RAG− mice (P < 0.001). Ankle swelling in C3H mice peaked about 14 days after infection and was in remission by day 21. Ankle swelling in C3H RAG− mice continued throughout the course of the experiment and was significantly greater than swelling in C3H mice at day 21 (P < 0.001). This result is consistent with the findings of others that immunodeficient C3H mice develop a severe progressive nonremitting arthritis (6, 22, 23). B6 and B6 RAG− mice did not display any significant increase in ankle diameters throughout the experimental period, suggesting an underlying resistance to the development of arthritis. Similar results were obtained when B6 SCID mice were substituted for B6 RAG− mice (Fig. 1B). We also examined the response of BALB/c RAG− and DBA RAG− mice to footpad inoculation with B. burgdorferi (Fig. 1C). Ankle curves for RAG+ control mice were similar to those for resistant and susceptible strains in Fig. 1A and B (data not shown). The C3H RAG− and BALB/c RAG− mice had significant progressive swelling of their ankle joints which was discernible by day 14 postinfection (P < 0.001). In contrast, DBA RAG− and B6 RAG− mice had no discernible ankle swelling throughout the experimental period. DBA RAG− and B6 RAG− mice that were monitored for 5 weeks did not develop ankle swelling or elevated arthritis severity scores, indicating that resistance was not simply due to delayed development of arthritis (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Effect of immunodeficiency on ankle swelling following infection of mice with B. burgdorferi. Mice (3 to 5 per group) were 4 to 6 weeks old at the time of infection and were inoculated in the hind footpad. Panels represent three separate experiments. Error bars represent ± standard deviations. Asterisks indicate significant differences in ankle swelling between resistant and susceptible mouse strains (P < 0.001). Crosses indicate significant differences in ankle swelling between C3H and C3H RAG− (C3H RAG°) mice (P < 0.05).

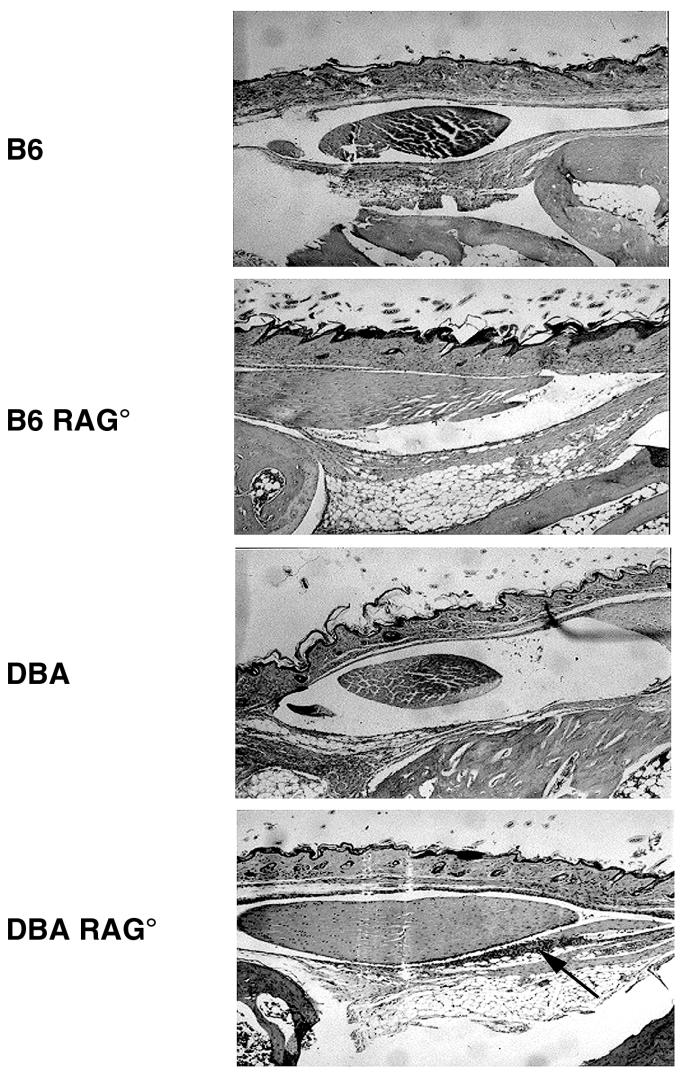

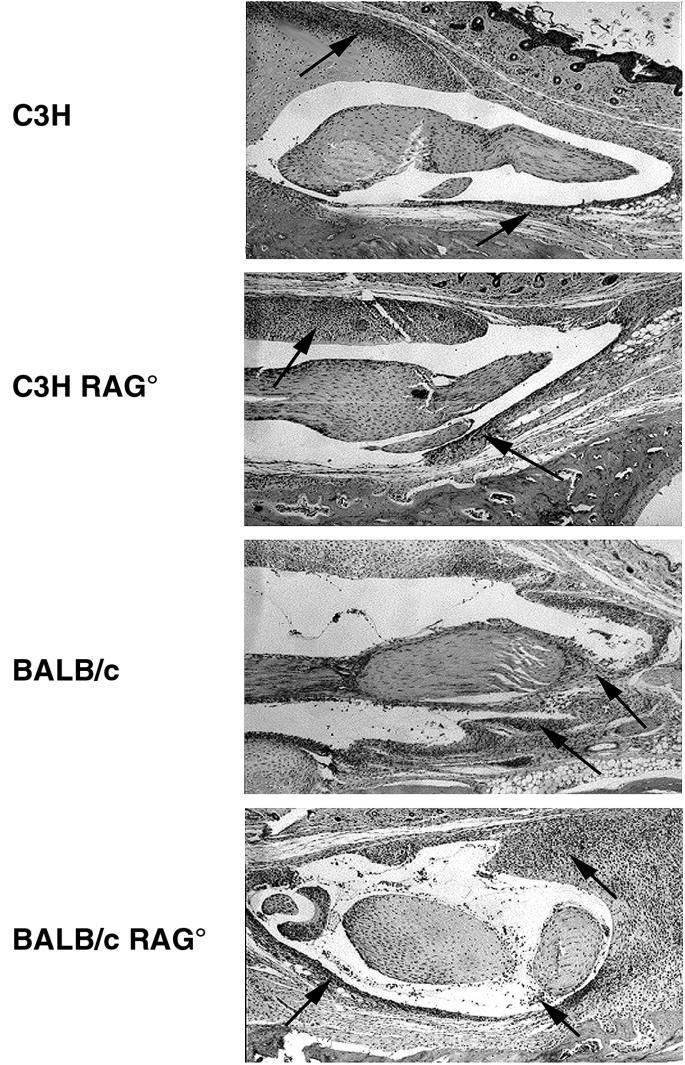

Ankle swelling does not always correlate with underlying arthritis development. Therefore, a histological analysis was performed to more accurately characterize the extent of pathology developing within the ankle. Figure 2 shows hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections of ankles from infected RAG+ and RAG− mouse strains. The slides are focused on the histological changes occurring around a major anterior tendon of the tibiotarsal joint as studied by others (18). Both RAG+ and RAG− C3H and BALB/c mice had severe inflammation characterized by tendonitis and hyperproliferation of the tendon sheath. Large inflammatory infiltrates of neutrophils and monocytes were present along with other histological abnormalities, such as synovial hypertrophy and effusion. These inflammatory changes were absent in slides from RAG+ and RAG− B6 and DBA mice. These data demonstrate that the lack of gross ankle swelling, indeed, correlates with the absence of underlying inflammatory responses in the resistant mouse strains. Occasionally, small foci of inflammatory cells were seen in some resistant animals (e.g., DBA RAG−; Fig. 2), but these were isolated and not comparable to the levels seen in C3H or BALB/c animals. Histological assessment of arthritis severity was determined in a blinded manner, and the results are shown in Table 1. Arthritis severity was scored on a scale from 0 (no inflammation) to 3 (severe arthritis) (6). There was a clear demarcation of arthritis severity scores between resistant and susceptible mouse strains. Susceptible strains had arthritis severity scores significantly greater than those of the resistant strains (P < 0.001). Severity scores of the B6 RAG− and B6 SCID mice were identical (B6 RAG−, 0.8 ± 0.6; B6 SCID, 0.8 ± 0.4).

FIG. 2.

Histopathology of tibiotarsal joints comparing immunocompetent and immunodeficient mouse strains infected with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi. Joints were obtained on day 21 of infection. Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Panels show development of tendonitis and are indicative of levels of inflammatory infiltrates in the ankles as a whole. Arrows point out foci of inflammatory cell infiltrates. Magnification, ×16.

TABLE 1.

Isolation of B. burgdorferi from selected tissues and arthritis development in ankles of control and immunodeficient micea

| Strain | Arthritis severity (n) | Culture result

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Joint | Blood | Heart | Spleen | Bladder | Ear | ||

| C3H | 2.1 ± 0.7* (29) | 9 | 3/9 | 0/9 | 4/8 | 3/7 | 8/8 | 3/6 |

| C3H RAG− | 2.5 ± 0.7* (20) | 1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| BALB/c | 2.2 ± 0.4* (5) | 9 | 6/6 | 3/9 | 6/8 | 3/9 | 6/7 | 2/7 |

| BALB/c RAG− | 2.8 ± 0.5* (5) | 2 | 2/2 | 1/2 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| DBA | 1.2 ± 0.8 (30) | 9 | 7/8 | 1/9 | 7/9 | 3/7 | 8/9 | 7/9 |

| DBA RAG− | 1.0 ± 0.0 (4) | 4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 2/3 | 1/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 |

| B6 | 0.6 ± 0.3 (2) | 2 | 1/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| B6 RAG− | 0.8 ± 0.6 (21) | 6 | 3/4 | 5/6 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 6/6 | 3/5 |

| B6 SCID | 0.8 ± 0.4 (6) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Mice were infected with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi spirochetes and sacrificed at 21 days. Culture results are presented as numbers of cultures positive for B. burgdorferi/no. cultured. Contaminated cultures were discarded. Tibiotarsal arthritis severity was scored on a scale from 0 to 3 (mean ± standard deviation) as described in the text. Asterisks indicate arthritis severity scores significantly higher than others (P < 0.001). ND, cultures were not done.

Arthritis resistance in BALB/c mice is related to their ability to control spirochete numbers and is overcome by high infectious doses (18) or immunodeficiency (6). In contrast, high infectious doses and high levels of spirochetes in the ankles of DBA and B6 mice do not result in the development of arthritis (13, 18). To determine if there were differences in spirochete presence in tissues of control and immunodeficient mice, we harvested blood, hearts, spleens, bladders, ears, and joints from RAG+ and RAG− mice and cultured them in BSK media for 2 weeks. There was widespread dissemination and high numbers of positive cultures in all tissues tested (Table 1). There was little difference between resistant and susceptible mouse strains in the presence of spirochetes in tissues. Thus, resistance to arthritis development in both the RAG+ and RAG− B6 and DBA mice was not dependent upon their ability to limit spirochete presence in tissues. Indeed, the greatest spirochetal burdens may have been in the DBA RAG− and B6 RAG− mice because they had high numbers of positive blood cultures (3 of 4 and 5 of 6 cultures were positive, respectively), while blood cultures from RAG+ C3H (0 of 9), DBA (1 of 9), and B6 (0 of 2) mice were negative or positive only at very low levels.

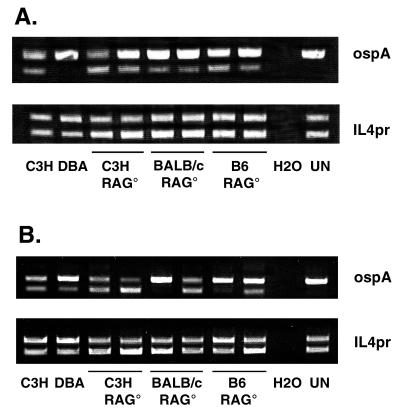

To directly compare spirochete burdens between mouse strains, we performed competitive PCR on DNA isolated from the ankle joints and ear punch circles 21 days after infection. We have previously shown that high levels of spirochete DNA in the ankles of immunocompetent mice are not sufficient to induce arthritis development in resistant animals (13). The BC3 polycompetitor (13) was spiked into samples to enable the relative assessment of borrelial DNA in ankle tissues by using competitive PCR. Each reaction was spiked with a constant amount of the BC3 competitor. The upper bands in each lane are the BC3 amplification products, and the lower bands are wild-type DNA PCR products. The amount of mammalian DNA used in each sample was equalized by using primers for IL4pr. Results of the PCR analysis of ankle tissue (Fig. 3A) demonstrate that resistance to the development of experimental Lyme arthritis in immunodeficient animals is not dependent upon limiting spirochetal loads. Ankle tissue from the control C3H mouse contained the highest level of spirochete DNA while the control DBA contained the lowest. Arthritis-susceptible C3H RAG− and BALB/c RAG− mice and arthritis-resistant B6 RAG− mice all contained similar levels of spirochete DNA in their ankle joints which were intermediate between the control C3H and DBA levels. We also examined spirochete DNA levels in ear punch samples from these same animals (Fig. 3B). Although the ear punch samples had greater animal-to-animal variability, there was no overall correlation between levels of spirochete DNA and arthritis development. Thus, similar to the results described for most immunocompetent animals (13, 18), arthritis development in immunodeficient mice does not correlate with spirochete loads.

FIG. 3.

Competitive PCR amplification of ospA and IL4pr from ankles (A) and ears (B) of control C3H and DBA mice, immunodeficient (C3H RAG− [C3H RAG°], BALB/c RAG− [BALB/c RAG°], and B6 RAG− [B6 RAG°]) mice, a water blank (H2O), and an uninfected mouse (UN). Each lane represents data from an individual mouse. Amplification products in the upper bands are from the BC3 competitor and those in the lower bands are from wild-type DNA. The amount of BC3 competitor spiked into each sample was 0.25 pg.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that resistance to experimental Lyme arthritis development, at least in some strains of mice, can occur in the absence of specific immunity. RAG+ and RAG− B6 and DBA mice were resistant to arthritis development following footpad inoculation of 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi spirochetes. In contrast, RAG+ and RAG− C3H and BALB/c mice developed severe arthritis in their tibiotarsal joints. The development of arthritis in RAG− B6 and DBA mice was not merely delayed, as these mice were still resistant up to 5 weeks after infection. We recently reported that high levels of spirochetes in the ankles of DBA mice do not result in arthritis development (13), and similar results have been reported for B6 mice (18). We now extend those observations and demonstrate that B6 and DBA mice remain resistant to arthritis development in the presence of high numbers of spirochetes in tissues, even in the absence of specific immunity. Thus, resistance and susceptibility may be the summation of a set of inflammatory regulators rather than antimicrobial effector mechanisms.

Whether resistance of RAG− B6 and DBA mice is due to genetic polymorphisms within the innate immune system is still unknown. Genes expressed within cells of the innate immune system are known to influence resistance and susceptibility to several infectious diseases. The murine Nramp1 gene (Bcg/Lsh/Ity) encodes an integral membrane protein on macrophages and determines the susceptibilities of inbred mouse strains to such pathogens as Mycobacterium leprae, Leishmania donovani, and Salmonella typhimurium (12, 21, 25, 27). Its human homologue, NRAMP1, has recently been shown to control susceptibility to leprosy in humans (1). Bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) are potent activators of macrophages and monocytes and trigger the release of many cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. These cytokines together can lead to toxic shock and death (26). Mice from the C3H/HeJ inbred strain or mice deficient in CD14 are resistant to the lethal effects of lipopolysaccharide (14). Similarly, polymorphisms in the Lgn1 gene on chromosome 13 control the natural resistance of macrophages of inbred mouse strains to infection with Legionella pneumophila (11). The patterns of inbred mouse strains with resistant and susceptible alleles to these genes do not correlate with patterns of resistance and susceptibility to Lyme arthritis development. Thus, other genes are responsible for resistance to Borrelia. Interestingly, in a study of mice with a granulocyte deficiency, B6 beige mice developed arthritis similar in severity to C3H mice (8).

Increasing the infectious dose in B6 or DBA mice does not result in increased arthritis incidence or severity; however, resistance to arthritis development in BALB/c mice appears to require efficient bacterial control and/or clearance (13, 18). The mechanism of resistance in BALB/c mice may therefore differ from the mechanism controlling resistance of B6 and DBA mice. The finding of arthritis exacerbation in C3H SCID mice treated with anti-IL-12 indicates that NK cells, macrophages, or other components of the innate immune system may play an important role in resistance to the development of Lyme arthritis (3). Whether resistance to Lyme arthritis development is mediated through macrophages or other components of the innate immune system is currently under investigation.

Our finding that immunodeficient B6 mice are resistant to arthritis development contrasts with the results of Keane-Myers et al. (17). In that study, B6 SCID mice infected subcutaneously (s.c.) in the base of the tail with B. burgdorferi 910255 developed ankle swelling and had high numbers of spirochetes in joints, hearts, and skin. The level of arthritis severity in these mice, however, was not reported. The reason for the different outcomes between these two studies is not clear. It is possible that B. burgdorferi 910255 or the s.c. route of infection causes ankle swelling without arthritis development in those animals. It is also possible that the two strains of B. burgdorferi used have different levels of pathogenicity. In the present study, both B6 SCID and B6 RAG− mice were highly resistant to arthritis development following footpad injection of B. burgdorferi N40 in at least five separate experiments. The B6 RAG− mice did have high levels of spirochetes in tissues as indicated by culture and PCR, which agrees with the previous study (17), but no swelling or arthritis development was observed.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that resistance to experimental Lyme arthritis can occur in mice in the absence of specific immunity. Thus polymorphisms, possibly in innate immunity, could be responsible for both resistance and susceptibility to arthritis development. Identification of the gene(s) and mechanism(s) involved may be important not only for patients with Lyme disease but for patients with other arthritides as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniel Brown and Erica Smith for their critical review of the manuscript, and Jennifer Bird for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grant AR 44042 and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel L, Sanchez F O, Oberti J, Hoa N V, Lap V D, Skamene E, Lagrange P H, Schurr E. Susceptibility to leprosy is linked to the human NRAMP1 gene. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:133–145. doi: 10.1086/513830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anguita J, Persing D H, Rincon M, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Effect of anti-interleukin 12 treatment on murine Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:1028–1034. doi: 10.1172/JCI118494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anguita J, Samanta S, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Ablation of interleukin-12 exacerbates Lyme arthritis in SCID mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4334–4336. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4334-4336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthold S W, Beck D S, Hansen G M, Terwilliger G A, Moody K O. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:133–138. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthold S W, Persing D H, Armstrong A L, Peeples R A. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:263–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthold S W, Sidman C L, Smith A L. Lyme borreliosis in genetically resistant and susceptible mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:605–613. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barthold S W, de Souza M S, Janotka J L, Smith A L, Persing D H. Chronic Lyme borreliosis in the laboratory mouse. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:959–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthold S W, de Souza M. Exacerbation of Lyme arthritis in beige mice. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:778–784. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barthold S W, de Souza M, Feng S. Serum-mediated resolution of Lyme arthritis in mice. Lab Investig. 1996;74:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barthold S W, Feng S, Bockenstedt L K, Fikrig E, Feen K. Protective and arthritis-resolving activity in serum of mice actively infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:S9–S17. doi: 10.1086/516166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beckers M C, Ernst E, Diaz E, Morissette C, Gervais F, Hunter K, Housman D, Yoshida S, Skamene E, Gros P. High-resolution linkage map of mouse chromosome 13 in the vicinity of the host resistance locus Lgn1. Genomics. 1997;39:254–263. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley D J. Genetic control of Leishmania populations within the host. II. Genetic control of acute susceptibility of mice to L. donovani infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;30:130–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Brown, C. R. Unpublished observations.

- 13.Brown C R, Reiner S L. Clearance of Borrelia burgdorferi may not be required for resistance to experimental Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2065–2071. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2065-2071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang I, Barthold S W, Persing D H, Bockenstedt L K. T-helper-cell cytokines in the early evolution of murine Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3107–3111. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3107-3111.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane-Myers A, Nickell S P. Role of IL-4 and IFN-γ in modulation of immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi in mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keane-Myers A, Maliszewski C R, Finkelman F D, Nickell S P. Recombinant IL-4 treatment augments resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi infections in both normal susceptible and antibody-deficient susceptible mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:2488–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y, Seiler K P, Eichwald E J, Weis J H, Teuscher C, Weis J J. Distinct characteristics of resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in C57BL/6N mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:161–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.161-168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matyniak J, Reiner S L. T helper phenotype and genetic susceptibility in experimental Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1251–1254. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rao T D, Frey A B. Protective resistance to experimental Borrelia burgdorferi infection of mice by adoptive transfer of a CD4+ T cell clone. Cell Immunol. 1995;162:225–234. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson H G, Vas S I. Resistance of inbred to Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J Infect Dis. 1972;126:378–386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/126.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaible U E, Kramer M D, Museteanu C, Zimmer G, Mossmann H, Simon M M. The severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mouse: a laboratory model for analysis of Lyme arthritis and carditis. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1427–1432. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaible U E, Gay S, Museteanu C, Kramer M D, Zimmer G, Eichmann K, Museteanu U, Simon M M. Lyme borreliosis in the severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mouse manifests predominantly in the joint, heart, and liver. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:811–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaible U E, Wallich R, Kramer M D, Nerz G, Stehle T, Museteanu C, Simon M M. Protection against Borrelia burgdorferi infection in SCID mice is conferred by presensitized spleen cells and partially by B cells but not by T cells alone. Int Immunol. 1994;6:671–681. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skamene E, Gros P, Forget A, Patel P J, Nesbitt M. Regulation of resistance to leprosy by chromosome 1 locus in the mouse. Immunogenetics. 1984;19:117–120. doi: 10.1007/BF00387854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulevitch R J, Tobias P S. Receptor-dependent mechanisms of cell stimulation by bacterial endotoxin. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:437–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidal S M, Malo D, Vogan K, Skamene E, Gros P. Natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites: isolation of a candidate for Bcg. Cell. 1993;73:469–485. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90135-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Weis J H, Eichwald E, Kolbert C P, Persing D H, Weis J J. Heritable susceptibility to severe Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis is dominant and is associated with persistence of large numbers of spirochetes in tissues. Infect Immun. 1994;62:492–500. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.492-500.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]